Abstract

This article analyzes the science fiction (SF) manga 7 Billion Needles in order to show how an overt visual and narrative emphasis on character emotions and psychology can contribute to science fiction's political potential by emphasizing the similarities between dialogue as a form of emotional therapy and the act of exploring alternative environments. This article also demonstrates how science fiction manga provides a template by which character emotion can become so integrated into the SF narratives and worlds that emotion itself becomes ‘science fictional’.

Introduction

As seen with Saitō Tamaki's (2011) psychoanalytic study of otaku and Azuma Hiroki's (Citation2009) idea of postmodern ‘animalization’ of narrative consumption, research on the political potential of Japanese popular media has focused heavily on active engagements that emerge out of emotional and affective responses from consumers of Japanese popular culture. In contrast, there has been a relative lack of attention towards depictions of emotion and affect as seen within Japanese visual media such as manga, despite the fact that manga carries a long history of emphasizing these qualities. Character psychology, particularly a narrative focus on characters' thoughts and expressions integral to the development of a story, is not only incredibly common in manga but also has been developed robustly through the pages of manga over the course of decades. While not every manga focuses heavily on the emotional content of its characters as driving forces, the manner in which emotions are drawn to the forefront, as well as the general centrality of their importance in visual expression within manga, offers a vast resource for understanding how the depiction of fictional feelings can convey the political desire for change or transformation.

This article analyzes the science fiction (SF) manga 7 Billion Needles (Tadano 2010-2011, hereafter 7BN) to show how common visual traits and techniques found in SF manga lend themselves to emphasizing character emotion, psychology, and affect such that these qualities can contribute to what Darko Suvin (Citation1979, pp. 4–7) calls ‘cognitive estrangement’, or how science fiction can potentially inspire the political desire for change by displaying the stark difference of its alternative world. The reason that this article focuses on SF is because of its reputation as a genre or mode that emphasizes political potential as the desire for greater change. SF is ‘an escape from constrictive old norms into a different and alternative timestream, a device for historical estrangement, and an at least initial readiness for new norms of reality…’ (Suvin Citation1979, p. 84) that at the same time tends to minimize the importance of character emotions by positioning them as a concession towards those unfamiliar with SF. As will become evident, 7BN demonstrates how the visual and narrative depictions of emotion and affect in manga are more than a mere gateway to greater ideas or a compromise for the sake of accessibility.

This article concentrates less on what character emotions are being exhibited and more on how they function within narratives, and makes use of both ‘affect’ and ‘emotions’ as different but frequently connected concepts. While manga generally does not make a strict distinction between the two, and expressions can be interpreted as one or the other given the frequent use of abstract visual manifestations of a character's inner world that accompany outward display, emotion as ‘projected/displayed feeling’ and affect as ‘non-conscious experience of intensity’ (Shouse Citation2005) often both play prominent roles in manga as they accompany each other. In particular, where affect plays an especially significant role is in the idea of it being ‘a different kind of intelligence about the world … and previous attempts to relegate affect to the irrational or raise it up to the sublime are both equally mistaken’ (Thrift Citation2008, 175). Affect relates to but is not beholden to cognition. Emotion, in turn, acts as the conduit that brings characters' affective expressions back into that cognitive space of science fiction. Together, emotion and affect act as a means to clarify the character in terms of identity and development that then also becomes the primary tool for showcasing both the very science fictionality of the worlds portrayed and the significance of those emotions in contributing to the process of cognitive estrangement.

In terms of visual analysis, this article concentrates on the concept of nagare, or the river-like ‘flow’ of panels and other visual elements in manga (Chavez Citation2011),Footnote1 as well as the blurring of the ‘internal’ psychological worlds and ‘external’ environmental worlds of its characters through the use of abstract and expressive backgrounds. It also focuses on manga's emphasis on panel layouts that treat double-page spreads and panel sequences, rather than the individual panel, as the pertinent units of information in manga as a form of comics (Natsume Citation2006, p. 34, Groensteen Citation2007, p. 116). Along these lines, while this article uses ideas found in cinema such as ‘close-ups’ to describe individual panels, it does not assume that manga, or comics in general, are about replicating cinematic experiences through shots (Motoo cited Natsume Citation2006, p. 34), nor are they primarily about the fusion of image and text (Carrier Citation2000, p. 38). By looking at 7BN according to the above visual elements and how they play out in its narrative, this article demonstrates how the particular methods of emphasizing emotion and affect in SF manga can allow these traits to act as an integral and interwoven component of the science fictional environment, and by extension the political potential of SF narratives.

The unique circumstances of Japanese SF manga

In order to understand the contention that is potentially born out of SF manga (and how SF manga defies this conflict), it is first necessary to see how the general values emphasized in manga and SF respectively at first appear to go against each other. Manga has a long history of integrating displays of emotions into a vast array of subjects and genres. Since at least Tezuka, who is famous for working in many genres while also pushing the experimental boundaries of Japanese comics (Kure Citation1997, p. 219), this variety has become a hallmark of manga (Kinsella Citation2000, p. 3, Schodt Citation1997, p. 15).Footnote2 The most well-known example is the anti-war, anti-nuclear weapon manga Barefoot Gen (Nakazawa 2004), which assumes the visual and narrative conventions of shōnen manga to be a legitimate form of political expression (Lamarre Citation2010, p. 254), and ‘focuses more on Gen's emotions than on his acts’ as a way to express the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima (Kajiya 2010, p. 251). More than simply acknowledging emotion, however, it is important to see how central its use is to manga as a narrative and visual art form.

While the techniques for expressing emotion and affect used in manga are not wholly unique to it, manga utilizes visual relationships of the comics page that exist more prominently compared with other forms of comics because of the general emphasis on nagare. When characters' emotions and affective responses are expressed in manga, a single instance is frequently displayed across multiple panels. Not only does this generally imply the passage of time across panels, but the fact that those panels exist next to each other on the two-dimensional page means that, unlike film (or indeed anime), the combined weight of those expressions are measured not only ‘temporally’, but also ‘spatially’. While the representation of a single figure in transition has itself a long history in the arts, notably Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (Citation1912), manga's function as mass-produced, accessible narrative media means that the shifting of figures across space is generally meant to be easily understood. The double-page spread in manga commonly discourages readers from lingering on any one panel for too long, although exceptions exist. In other words, emotions in manga are expressed across time and space, and the aesthetics of manga encourage this tendency to the point of being ubiquitous, such that they are prolific and widely accepted in all narrative genres, including science fiction.

Emotions and affect impact manga narratives with a great deal of immediacy: information in manga, whether it is concrete or abstract, is portrayed primarily through images (or at least a combination of image and text) where characters are typically prominent. Not only is manga known for having ‘highly expressive and emotionally readable manga characters’ that ‘tend to embody aspects of caricature’ (Kinsella Citation2000, p. 7), but intense displays of feeling in manga can even extend beyond the characters into the backgrounds and environment, visually externalizing the inner psychology of characters and connecting those portrayals through the flatness of the comics page. This trait is historically derived from and most commonly seen in shōjo manga, particularly the work of artist Takahashi Macoto. Takahashi's full-body depictions of characters (‘style pictures’) and flurries of flowers and abstract symbols in the 1950s first defied and exploded the traditional panel-based comics format for the sake of emotion (Fujimoto Citation2012, Shamoon Citation2012, pp. 94–100), in contrast to other artists such as Ishinomori Shōtarō and Shishidō Sagyō (artist of 1930's manga Supīdo Tarō) who broke the panel for the sake of action (Takahashi Citation2008, p. 126, Natsume Citation2006, pp. 34–35). This shōjo style has, over the decades, become an increasingly frequent presence in non-shōjo manga to varying degrees, as can be seen in 7BN.

Because backgrounds as perspectival spaces are often considered less important in manga (they will frequently drop out of panels entirely, such as in 7BN), that flatness, combined with the surrounding frames of the comics page, its balloons, and its general organization of elements into a ‘spatio-topical system’ (Groensteen Citation2007, p. 24) further pushes foreground and background together, eroding the line between character and environment. Moreover, the use of characters themselves as two-dimensional ‘images’ also means that, unlike purely prose-based science fiction, their kyara (Itō Citation2005, p. 263), or ‘soulful bodies’ (Lamarre Citation2009, p. 201), exude a sense of liveliness and emotions, which are a consistent presence on the manga page that is difficult to ignore.

In contrast, emotions and affect, or more specifically narratives where such qualities are of great importance to the outcome or resolution, have long been an area of contention in SF. One long-standing view of SF, exemplified by Suvin, connects it to utopian fiction in order to differentiate it from traditional fiction. SF prioritizes not the character but the ‘novum’ – the scientific novelty or innovation that is primarily responsible for the stark difference between the real world and those found in science fiction (Suvin Citation1979, p. 63) – which is then presented through the process of cognitive estrangement. Within this conception of science fiction, character emotion and its development, while not denied a place in science fiction, is nevertheless relegated to an accessory, lest SF narratives become ‘far more interested in the way in which the future shapes the emotional lives of the protagonists than the way in which the future develops’ (Mendlesohn Citation2009, p. 75). Similarly, although they do not go as far in terms of their theorizing of the vital components of SF, both Bould's (Citation2002, p. 83)Footnote3 paranoid mode of fantasy and Angenot's (Citation1979) ‘absent paradigm’ emphasize the seeming need for SF to self-reflexively display the sense of an alternate world without being able to rely on (or indeed intentionally eschewing) strict referents to reality. Here again, the character acts as a vessel to experience SF worlds, prioritizing the environment over its individuals.

Manga presents an environment where character emotion, affect, and psychological development are not only prominent in SF, but also foundational to the growth of SF in Japan. ‘Japanese SF’ includes both Japanese SF across multiple mediums and decades' worth of Western SF imported since the 1960s (Tatsumi Citation2006, p. 87) that altogether have ‘incorporated the various [SF] traditions synchronically rather than diachronically’ (Bolton et al Citation2007, p. xi), and manga contributes significantly to this development. Komatsu, one of the innovators of Japanese science fiction (Yamano Citation1994), places the origin of Japanese science fiction in the development and popularization of the modern ‘story manga’ format in the mid-twentieth century (Schodt Citation1996, Prough Citation2011) by associating SF with manga's most famous creator and his SF narratives that began in the 1940s. ‘The planet SF was found near the Tezuka Osamu system in the manga nebula’ (Komatsu Citation2006, p. 98). In Uchū ni totte ningen to wa nanika: Komatsu Sakyō shingenshū [What are humans in regards to the universe?: a collection of Komatsu Sakyō quotes], one of the contributing essays is by Hagio Moto (Citation2011, pp. 40–43), a manga creator celebrated for her emotionally oriented shōjo SF manga and her influence on manga in general. The first female manga creator to receive a Japanese Medal with Purple Ribbon for decades' worth of contribution to Japan through manga (Comic Natalie Citation2012), works such as 1975's 11-nin iru! [They were 11!] (Hagio Citation1994) and 1981's A, A' (Hagio Citation1997) deal with the challenges of love, passion, and the transformation of those emotions in futuristic settings and unusual social environments.Footnote4 Hagio's 1978 manga Sutā reddo [Star red] (Citation1995) in particular is considered ‘a classic work among shōjo comics that attracted many science fiction fans’ by utilizing ‘poetic language and beautiful artwork’ (Kotani Citation2007, p. 57).

Popularizing the shōjo visual style first seen in the work of Takahashi alongside the rest of the Shōwa 24 group of popular shōjo manga artists, Hagio's visual style fully embraced and further developed the use of all-encompassing emotional flurries of panels and pages that emphasize both temporality and spatiality in SF manga. It is also notable that fellow Shōwa 24 group member Takemiya Keiko brought this aesthetic to shōnen manga when she created To Terra (Citation2007). Originally serialized from 1977 to 1980 in the publication Gekkan manga shōnen, it won the Ninth Seiun award for comics (in science fiction) and the 25th Shogakukan Manga Award in 1980 (Hatano), contributing to the proliferation of shōjo manga's more emotional art style in other genres and demographics. In both Sutā reddo and To Terra, their narratives, explorations of their worlds, and even ultimately their resolutions are all tied to the flow-centric visual display of emotion and affect ubiquitous in manga, and its continued acceptance in contemporary works such as 7BN and Neon Genesis Evangelion (Sadamoto 2012–Citation2013) strongly indicates a near-inextricable presence of emotion from the novum and cognitive estrangement in SF manga.

This is not to claim that SF manga is the only source of SF that prioritizes its characters' emotional development and affective responses to their worlds, and in fact the sense of wonder experienced by character-as-reader-conduit can be considered a kind of affect. Writers such as Le Guin (Citation1979, p. 116) have famously questioned the point of science fiction if the characters within it and their emotions matter less. At the same time, although character psychology and development are given importance, an emphasis on those qualities frequently risks reinforcing (perhaps inadvertently) a sense of dichotomy between the two areas, where emotional characters either act as concessions that allow larger audiences to enjoy science fiction, simplify ideas so as to make them more accessible, or assume that character development and emotion are indeed the fundamental tenets of narrative fiction and therefore should be upheld over the novum and the SF environment.

Thus, while a similar relationship between emotion and the novum can and often does exist in other media, SF manga presents an alternative to a contentious environment where the two sides are perceived as being at odds with each other. This is because SF manga frequently denies the opportunity to concentrate on either the novum or character emotions at the expense of the other. Instead of becoming grounds for dispute where prominent character psychology must necessarily struggle against the importance of the novum, either within the narratives themselves or in the discourse surrounding them, SF manga carries greater potential to show how the two are capable of a more thorough cooperation and integration, and how this can benefit the study of both manga and SF.

Emotional exploration as SF navigation in manga

Central to the original Suvinian idea of cognitive estrangement is the notion that SF is a kind of cultural product that is more likely to exceed the limitations of what Adorno (Citation2004) calls ‘mass culture’ or ‘the culture industry’. In contrast to the tendency for mass culture to manipulate emotions to maintain a sense of status quo (Adorno Citation2004, pp. 58–62), SF engenders desire for change, or at least carries greater potential to accomplish this. Suvin argues that both cognition and estrangement are vital to science fiction. In terms of cognition, ‘SF first posits [phenomena] as problems and then explores where they lead; it sees the mythical static identity as an illusion, usually as fraud’ (Suvin Citation1979, p. 7), which allows it to explore the seemingly impossible and therefore open up other political possibilities (Suvin Citation1979, p. 8).

However, in order for an emphasis on character emotion to possibly be of direct use to science fiction, its presence cannot automatically invalidate its political potential. Thus, this article is founded in the idea that the genre of SF requires a reconsideration of the meaning of cognitive estrangement that does not outright deny its significance and is at the same time flexible enough to work beyond its original conception. Instead of character emotion overcoming or overwhelming cognitive estrangement either in part or in whole (Footnote5), the expansion of SF as a category can be thought of as widening the range of what can be referred to as cognitive estrangement in the first place (see ), and it is through SF manga that this will be shown. This is because manga's visual properties, as well as its aesthetic, narrative, and industry-wide emphasis on emotion makes them difficult if not impossible to ignore when approaching a work of SF manga.

Figure 1 A visualization of the idea that cognitive estrangement has lost significance in science fiction

Figure 2 A visualization of the growth of cognitive estrangement in accordance with the widening of the definition of science fiction itself

On a certain level, this idea bears some similarities to Azuma's (Citation2009, pp. 27–35) argument that, in a postmodern environment, people (notably otaku) do not take in stories as a whole but rather extract relevant information for their own use through a ‘database narrative’ approach. Here, deciding on ‘relevant information’ involves finding the attractive qualities of characters and other elements to piece together new and individualized narratives. While people can indeed interpret more fully formed ideas out of bits of information, this article is not about how audiences defy, subvert, or transform narratives for their own use, as stated in the introduction. What can instead be derived from Azuma is the idea that this postmodern approach to media and fictional worlds can apply to many things. SF manga is a space for this ‘animalization’ as well; depictions of emotion can act as the database units themselves or the glue that binds them together. However, the history of both Japanese SF and manga consist of narratives that have operated under assumptions of a world influenced by both ‘grand narratives’ and ‘database narratives’, and it becomes important not to consider these two categories as wholly incongruous.

On a general level, the potential for science fiction to utilize emotion as a cognitive component for estrangement has been made likelier due to the fact that ‘science’ itself has also grown to include not only the material sciences but also the affective and social sciences (see for example Ekman and Davison Citation1994, Hoggett and Thompson Citation2012). The tendency when discussing science fiction and traditional character psychology-oriented fiction may be to emphasize their differences, but here their similarities are just as significant. In particular, when looking at the concept of ‘character identification’, where the depiction of a character's inner state encourages empathy, it resembles in many ways the idea of cognitive estrangement in SF because it often involves a similar interpretive process whereby one bridges the fictional narrative with the reality of one's experiences:

‘Character identification often invites empathy, even when the fictional character and reader differ from one another in all sorts of practical and obvious ways, but empathy for fictional characters appears to require only minimal elements of identity, situation, and feeling, not necessarily complex or realistic characterization’.

(Keen Citation2006: p. 14)

In a similar vein, Matravers asks how people are able to feel that the emotions of fictional characters are ‘real’ even when they are aware that these emotions do not exist in reality (Matravers 2006, p. 54 cited in Palencik Citation2008, p. 259). Carroll (Citation1998, p. 265) writes that, ‘Rather than character identification, it is our own-pre-existing emotional constitution, with its standing dispositions, that the text activates. This, in large measure, is what accounts for our emotional involvement with narrative fictions in general and mass fictions in particular’. Although these statements are not in full agreement, what is common among all of them is the idea that the ability to think of characters as emotionally ‘real’ from minimal qualities requires imagination and a connection to the historical present. While character identification cannot be considered perfectly identical to the interpretive process involved with science fiction, the commonality between it and the process of exploring the novum provides a means through which a focus on character emotions and psychology can be investigated within an SF environment that does not necessarily reduce the importance of that environment. In other words, interpreting character emotion and affect, like extrapolating the novum, involves its own process of thoughtful elaboration.

Berlant (2011, p. 41) states, ‘Affect's saturation of form can communicate the conditions under which a historical moment appears as a visceral moment … the aesthetic or formal rendition of affective experience provides evidence of historical processes’. While Berlant is not writing solely about SF (though she references both it and utopian fiction), the fact that it is presented as something capable of being attuned to history allows the depiction and expression of affect a place and role in SF. Moreover, the positioning of emotion as a critical tool blurs the lines between modern and postmodern SF narratives due to the interactive process of the reader and the depicted (emotional) interactions of the characters within the SF world. To take it one step further, it is not merely affect as response or window into the alternative world that fuels its role in SF, but also that it can play an active role in shaping that very same world. In manga, where emotion flows into affect and vice versa, it becomes possible that this very transformation between the two types of ‘feeling’ is akin to exploring the logical processes that dictate the SF environment as a part of the characters living within it. In fact, the depiction of emotion and affect as not only creating similar feelings in readers but also encouraging them to consider different ways of viewing their world and society can be seen as a kind of cognitive estrangement. The investigation of the effects of the novum, its potential for inspiring change through cognitive estrangement, and the exploration of character emotion and affect can, in a certain sense, be treated as almost one and the same, or at least as interconnected aspects of a world, an ambiguity that becomes a strength of SF manga as science fiction.

7 Billion Needles

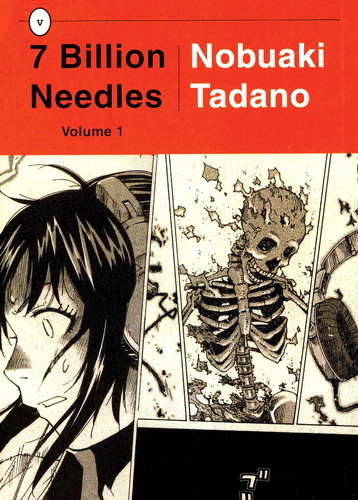

Through its visual and narrative presentation, 7BN shows itself to be a work that addresses its novum and its characters' emotions together, fusing the two concepts together along the way. A loose adaptation of the classic 1950s SF novel Needle by Hal Clement, 7BN () shares a similar premise with its source material, wherein a symbiotic alien biologically fuses with a human and confers extraordinary abilities in order to enlist help in stopping an extraterrestrial criminal. Indeed, its origin as an adaptation of a popular classic SF narrative is one reason why it is the focus of this article. The second reason is that 7BN exhibits many of the properties of SF manga described above, namely the heavy interweaving of emotion into the core of its story and its emphasis on visual presentation of those emotions, transforming the exact nature of its identity as ‘speculative fiction’. Thus, 7BN acts as a clear intersection between the traditional values of SF and manga, allowing for a detailed analysis of their combined usage.

Figure 3 A cover of 7 Billion Needles. From: Tadano, N., Citation2011. 7 Billion Needles, vol. 1. New York: Vertical, Inc, cover. © Tadano Nobuaki. Reproduced with permission from the author

The differences between Needle and 7BN are evident when comparing the personalities of each story's respective protagonists. In Needle, Robert Kincaid is a naturally inquisitive and friendly boy whose peaceful life is transformed by his encounter with the alien. In 7BN, Takabe Hikaru is characterized by her highly emotional reactions as a result of the traumatic experience of not only losing her parents but also being harassed due to the mistakes of her father. Thus, while Robert is portrayed as something of a neutral slate, drawing from the tradition of the narrative utopia by acting as a ‘formal “registering apparatus”’ whose movements during the course of the narrative action produce a traveler's itinerary of both the “local intensities” and “horizons” of the space that the narrative itself calls into being' (Wegner Citation2002, p. 13), Hikaru has specific emotional problems that provide a point of empathy for her and a story of her own to resolve even before she encounters anything out of the ordinary.

While this could potentially indicate that her psychology is a separate issue from the novum, the manga also shows through its visual presentation how Hikaru's feelings deeply affect her engagement with the symbiotic alien. Deliberately distancing herself from others due to her past trauma, Hikaru's emotions and affective responses are, from the very beginning, a constant factor in her communication with the alien Horizon. For example, Hikaru is shown to normally wear headphones, which symbolize her desire to keep everyone at a distance. When the symbiotic alien first introduces itself to her by speaking past those headphones (Tadano Citation2010, vol. 1, pp. 26–29), the panels focus first and foremost on her reactions to not so much the bizarre reality of having an alien inside her or that Horizon has reconstructed her biology, but how it affects her ability to willingly isolate herself. While in Needle the first question out of Robert's mouth is, ‘Wh-who are you? And where are you? And how-?’ (Clement Citation1999, p. 56), Hikaru's response in 7BN is ‘Get out of my ears! Leave me alone!’ (Tadano Citation2010, vol. 1, p. 29). Hikaru's physical body, as well as her increasingly intense and frustrated facial expressions embody both elements of affect and emotion, and dictate the flow of visual elements such that they dominate these pages. At the same time, the frequent use of flat, non-perspectival backgrounds and increasingly irregular, non-rectangular panels throughout the pages draw attention to those expressions (). In this scene, the isolated mental world she has set up herself has been violated, further highlighting how Hikaru's emotional turmoil is central to her view of the world, and that it heavily influences her perception of and interaction with Horizon. As a result, when looking at 7BN and its ideas, it becomes necessary to take Hikaru's feelings into account.

Figure 4 Hikaru emotionally reacts to the alien presence within her primarily by referencing her own history. From: Tadano, N., Citation2011. 7 Billion Needles, vol. 1. New York: Vertical, Inc. 28–29. © Tadano Nobuaki. Reproduced with permission from the author

Due to its grounding in reality, 7BN (and indeed Needle as well) obviously does not fully conform to Angenot's absent paradigm. It is set in contemporary Japan where, outside of the presence of aliens, both visual and cultural aspects of Japanese society are clearly present. However, this connection to contemporary reality does not hold 7BN back from exploring its science fictional process, and it is through the empathic qualities of emotional and affective expression that the story engages on a science fictional level. After all, if the absent paradigm is truly without referents to reality, then such a world would not ‘estrange us’ but ‘simply alienate us’ (Goto-Jones 2010, p. 23), greatly reducing the potential for cognitive estrangement, emotional or otherwise.

As the narrative progresses, Hikaru develops a close bond with Horizon that allows her to overcome her self-imposed isolation, to make friends, and to appreciate her relatives who have adopted her. In this respect, 7BN might initially appear to be not so much an SF manga as it is a Japanese comic with the trappings of SF that focuses more on the theme of overcoming a ‘personal problem’, a ‘term that designated neurotic paralysis and the hangups that prevent people from functioning’ (Jameson Citation2005, p. 297). However, even the means by which Horizon helps Hikaru to become more social comes about because of the influence of the novum (in this case the process and consequences of symbiosis with an alien), and her emotional development continues to exert an effect on the ongoing science fictional processes of the narrative. By being constantly present through their visual depiction, Hikaru's emotions and affective engagement with her world contribute to the manga's potential for bringing about cognitive estrangement. Although science fiction is frequently about the exploration of alternative environment through characters, 7BN sets up the psychology and emotions of Hikaru to play in part the role of ‘SF environment’ due to how the trauma of her past influences her perspective. Hikaru's inner ‘world’ and the actual world in which she lives are bridged through the act of symbiosis.

As a literal part of Hikaru, Horizon forces her into a perpetual state of dialogue that prevents her from retreating into her own mind and avoiding others. Here, the very idea of talking to another in order to resolve personal and emotional issues becomes a demonstration of the processes through which Hikaru changes, encouraging the image of her mind as a kind of science fictional space, even when no overtly science fictional elements are present. After Hikaru tries and fails to talk to two classmates in the process of investigating the whereabouts of the criminal alien (known as Maelstrom), two girls later befriend Hikaru by sitting down next to Hikaru, pulling off her headphones, and proceeding to discuss their favorite members of a particular band (Tadano Citation2010, vol. 1, pp. 122–123). Viewed by itself without prior context, this scene could hardly be called science fictional, but the fact that the girls' actions directly parallel Horizon's own strategy for bypassing Hikaru's emotional barriers takes something as seemingly mundane as chatting to a classmate in order to find out her taste in celebrities, and renders it part of a logical process originating from the novum of alien symbiosis.

The significance of character empathy as seen in 7BN is not so much that it allows an audience to more directly connect to the world of the narrative, but that it provides additional context through which to view the SF environment and to consider emotion and affect as a force of influence on the novum that is, in turn, also influenced by the novum. 7BN shows how a narrative focused on a character resolving emotional and psychological trauma can not only happen within a science fictional environment, but that the emotions of its central character can become a site of science fictional change. The exploration of character psychology, as a tool for character identification, integrates with the exploration of the novum.

This visual and narrative use of emotion and affect in 7BN reflects a philosophy akin to the ‘alternative moral epistemology’ of Walker, (Citation1989, p. 16), a counter-argument against the idea that the best moral and political solutions come out of impersonal and rational objectivity. Instead, solutions are better when arrived through ‘shared processes of discovery, expression, interpretation, and adjustment between persons’, a method that relies on a viewing of ‘particular persons as a, if not the, morally crucial epistemic mode’ (Walker Citation1989, p. 16). In the context of SF, it provides a malleable or customizable form of investigation of the science fictional world, questioning its structure and evoking the idea that ‘Cyborg imagery’ (or in the case of 7BN symbiotic imagery) ‘can suggest a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves’ (Haraway Citation1991).

The visualization of character emotion as alternative perspective

The depiction and exploration of character emotions affects the presentation of the novum in 7BN, allowing the character to provide an ‘alternative perspective’, or a view of the science fictional environment that is a step removed from the notion of character as formal registering apparatus. Hikaru's inner psychology provides a very different view of the idea of alien symbiosis compared with Robert in Needle by acting as the contextualized and affective viewpoint of a character that is in some sense ‘unreliable’ for apprehending her world, as opposed to requiring SF protagonists to be objectively and actively rational in their engagements with their science fictional environments. As seen in Hikaru, this can potentially provide various insights into a given science fictional space, where emotions become a means by which to clarify the novum. By considering its own characters as beings with emotional positions specific to their individual circumstances and backgrounds, 7BN shows how a work of science fiction can actively use the subjective biases of those characters as a way to expand the portrayal of a science fictional world.

The idea of emotion as alternative perspective is not proof that emotional science fiction is fundamentally superior to SF that eschews emphasis on character psychology, nor is it an argument that emotions are inherently resistant to the concept of the ‘ideal’ protagonist. After all, not only do a vast number of stories outside of science fiction presume their main characters and their inner psychologies to be the perfect means to transmit a certain set of values, but even Hikaru in 7BN is conveniently positioned in ways that connects her directly to the novum. However, by being purposely placed in her narrative as a less-than-ideal protagonist, Hikaru points towards a use of emotion that reflects Valentin Volosinov's thoughts on truth as described by Wegner (Citation2002, p. 4): instead of assuming either fact or individual subjectivism as the ultimate truth, a ‘dialectical synthesis’ between these two approaches is preferable. 7BN shows how, by considering its own characters as beings with emotional positions specific to their individual circumstances and backgrounds, works of science fiction can intentionally operate from the subjective biases of those characters as a way to expand the portrayal of a science fictional world and thus contribute to cognitive estrangement.

Character emotion and affect as potential logic

Although Hikaru is the primary focus of 7BN, the manga also features the emotional and psychological development of the symbiotic alien Horizon. As Hikaru resolves her inner turmoil, her emotions increasingly act as a catalyst for change in Horizon, functioning essentially as a highly different environment that initiates a gradual process of change in Horizon. During their initial interactions, Horizon is characterized by a calm and highly logical approach to situations. At one point Hikaru has her arm sliced off by Maelstrom and passes out, forcing Horizon to take control of her body in order to survive. As the manga shows the Horizon-controlled Hikaru calmly assessing the situation and re-attaching Hikaru's arm, the panels feature ‘Hikaru’ and her lack of expression, as well as a use of flow that emphasizes background details and trails of blood from Hikaru's severed arm, implied to be Horizon's point of view (). When Hikaru regains control of her body on the following pages, 7BN changes immediately to a flow that is dictated primarily by Hikaru's shocked and exasperated facial expressions (somewhat similar to the scene when Horizon first communicates with her) and less by her surroundings (). For the most part, the backgrounds used in the panels after Hikaru is conscious once more cease depicting realistic environments and are instead simplified expressive spaces that draw attention to Hikaru herself.

Figure 5 The panel flow for Horizon emphasizes its logical, observational nature. From: Tadano, N., Citation2011. 7 billion needles, vol. 1. New York: Vertical, Inc., 70–71. © Tadano Nobuaki. Reproduced with permission from the author

Figure 6 The panel flow for Hikaru focuses on her emotional reactions. From: Tadano, N., Citation2011. 7 billion needles, vol. 1. New York: Vertical, Inc., 72–73. © Tadano Nobuaki. Reproduced with permission from the author

By juxtaposing Hikaru and Horizon's psychologies the manga sets up Horizon's later development, where it begins to prioritize its own emotions (as well as Hikaru's) in its decision-making. Here, Hikaru's emotions ultimately help Horizon to overcome the limitations surrounding the circumstances of its own existence. When Horizon learns that its struggle with Maelstrom is a recurring cycle dictated by the forces of the universe that oversee life and evolution, and that they lose their memories of their battles whenever one is ‘killed’, it is the decision to bring Maelstrom into a state of coexistence within Hikaru's mind that allows Horizon and Maelstrom to break free from their historical cycles and to effectively gain their own political agency through a process of ‘cognitive estrangement’. Hikaru's affect and emotions function as a kind of ‘nested novum’ within the narrative itself, a new aspect of the symbiotic aliens' environment that engenders in them a stark sense of difference that also leads to their freedom. Signifying this change is what can be seen as an affective response turned emotional outburst from Horizon, who upon discovering the presence of evolutionary subspecies of itself and Maelstrom, exclaims, ‘Lies!!’ in a manner previously unseen, letting loose an unexpected stream of electricity, something the calm and fully controlled Horizon would not have done before (Tadano Citation2011, vol. 3, p. 72). While the ideas of novum and cognitive estrangement are originally meant for readers and not the characters within, 7BN demonstrates how the exploration of character psychology and emotions can lead to a similar result by displaying just such an occurrence in its own narrative.

Thus, in addition to using emotion and character psychology to provide alternative perspectives on their SF environment, 7BN also demonstrates a use of emotion where a sense of ‘potential logic’ is implied within its expressions. Emotion, rather than being perceived as something opposite to logic and reason, or even something separate from it, is utilized as a form of thought derived from a logic that has yet to be clearly defined, connecting to the idea of affect as an alternative type of intelligence. As a result, ‘characters who are never fully on the side of reason or unreason’ (Lamarre Citation2009, p. 177) have a clear purpose in science fiction, a narrative genre that emphasizes on-going processes.

Achieving its own freedom from the system that governed its life, 7BN shows how Horizon comes to bridge the gap between another extraterrestrial that also emphasizes overt logic and reason above all else, and Hikaru, who continues to respond to the world through the lens of her emotions. As briefly mentioned above, towards the end of 7BN, Horizon and Hikaru learn that the prolonged presence of the symbiotic aliens in Hikaru has caused non-sentient evolutionary offshoots of the aliens to appear and fuse with the flora and fauna of Earth. Another alien being, a ‘Moderator’ tasked with overseeing the evolutionary path of the planet, seeks to reset life on Earth and start over anew. Just as when Hikaru had her arm removed, Horizon takes over Hikaru's body in order to communicate with the Moderator, but now ‘Hikaru’ implores the Moderator to empathize with Hikaru and her desire to save her friends and family. Having learned and grown psychologically within Hikaru, Horizon speaks in order to translate Hikaru's emotional outbursts of concern into something the Moderator can understand, showing proof of its emancipation as a result of Hikaru's emotions:

All Hikaru wants is to ‘save Chika and Saya.’ I have never felt such a strong will in Hikaru before. Maelstrom and I did not induce it. Hikaru's ties to the people around her gave rise to the form. I believe it's the same with evolution. May it be that the future of life on this planet doesn't require our interference?

(Tadano Citation2011, vol. 4: pp. 79–80)

Here, Horizon implies that Hikaru's affective responses and emotions possess a potential for logic. While Hikaru may not fully understand the reasoning behind her own words and actions, they nevertheless represent an idea or a feeling that is in the process of becoming logical. This, in turn, reflects the potential for emotion and affect in science fiction to emphasize the very notion of ‘ideas in progress’.

Wegner (Citation2002, p. 19) writes, ‘Of course, this project [utopia] too will only ever be partially successful, for the Archimedean point of any such a critical totalization similarly will be located in the always deferred, the “not-yet-become” unity of the utopian future’. While Wegner is writing about utopian texts from the 19th and 20th centuries concerned with the building of nation-states, the strengths of that genre translate to SF as well. Their worlds can be viewed without having definitive beginnings, middles, and ends and still be considered ‘science fictional’; this idea can be extended to the development of character psychology and emotions within SF. Walker's interpretation of the word ‘narrative’ in her alternative epistemology separates emotional expression from emotional satisfaction and the absolute need for dénouement, casting it as an ongoing process ‘that has already begun, and will continue beyond a given juncture of moral urgency’ (Walker Citation1989, p. 18), which resembles the open-endedness inherent to science fiction:

…[I]n order for narrative to project some sense of totality of experience in space and time, it must surely know some closure (a narrative must have an ending, even if it is ingeniously organized around the structural repression of endings as such)…. The merit of SF is to dramatize this contradiction on the level of plot itself, since the vision of future history cannot know any punctual ending of this kind, at the same time that its novelistic expression demands some such ending.

(Jameson Citation2005, p. 283)

While it cannot be said to be entirely lacking in dénouement, the ending of 7BN expresses both Walker and Jameson's notions of implied continuations to narratives, combining the inner development of its characters with the extrapolation of the science fictional world such that emotion is included and even integral to the ongoing processes of the world. Hikaru (with the help of Horizon and Maelstrom) manages to convince the Moderator to maintain life on Earth, but her alien biology goes out of control. In order to save her, Horizon and Maelstrom extract as much of their genetic material as they can, forcing them to leave forever because, and in spite of, the emotional bonds they have formed with her. Afterwards, Hikaru seemingly returns to her normal school life, but two factors make this less a reversion to the status quo and more a continuation of the SF narrative. First, Hikaru no longer actively isolates herself, as can be seen from the fact that the third-to-last page of 7BN is her singing karaoke with her friends (Tadano Citation2011, vol. 4, p. 148). Much like the scene involving the removal of her headphones by her friends, it appears to be ‘normal’ when taken by itself, but within the context of 7BN it serves to highlight her emotional growth as a result of being connected to Horizon and Maelstrom.

Second, the symbiotic aliens are unable to fully remove the alien DNA within her, which ultimately takes the form of a duck-like creature living inside of Hikaru that she is left to foster. Having appeared earlier in the manga as an evolutionary subspecies of Maelstrom, the manga concludes by showing that, whereas this ‘duck’ was previously a non-sentient being, it begins to communicate with Hikaru, thus implying that her emotions are causing this creature to evolve and gain self-awareness as well. Following the page with Hikaru at karaoke is one where Hikaru is by herself (Tadano Citation2011, vol. 4, p. 149), only the presence of the duck means, just like her time with Horizon, that she is never truly alone. This is connoted by the fact that, while the flow of this page mostly includes panels depicting Hikaru staring up at the sky in reminiscence of the symbiotic aliens, the very last panel is an image of the duck (). Emotion shows itself to be both ‘alternative perspective’ and ‘potential logic’ throughout 7BN, and continues to do so even as the manga concludes.

Figure 7 The symbiotic duck in the last panel implies that, while Hikaru has resolved her own emotional story, her emotions continue to influence her science fictional environment. From: Tadano, N., Citation2011. 7 billion needles, vol. 4. New York: Vertical, Inc., 188–189. © Tadano Nobuaki. Reproduced with permission from the author

Jameson describes the limit of utopias (and by extension science fiction) as the fact that there inevitably comes a point at which some of the vital differences that cause an alternative world to differ from the contemporary are not elaborated (Jameson Citation2005, pp. 85–86), and even science fiction, with the novum at its center and cognitive estrangement as its goal, is restricted by the inability for every logical process to be fully explained. However, while the logic of SF generally relies on being relatively self-contained and either suggesting or stating how the various components of an alternative world connect with each other as per Bould's paranoid mode, that logic is generally not thought of as vanishing simply because some elements are left ambiguous. The ability to reinforce logic by the assumption that a plausible process exists can instead be considered one of the strengths of utopian and science fictions, where the ‘absence’ in an absent paradigm does not undermine the status of a work as SF. 7BN shows how this process can directly include the emotions of characters. More than simply acting as the ‘raw material’ for science fiction narratives, or transforming SF narratives into works with aesthetic values unique from psychological art (Jameson Citation2005, p. 299), 7BN draws from cognitive estrangement, as well as the emotional development of its characters, to convey the ongoing effects of dialogue within science fictional spaces.

The image of the inner world as a science fictional space

The depiction of character psychology and emotions as a way to encourage a view of emotion as both ‘alternative perspective’ and ‘potential logic’ is best seen through the use of visual doppelgangers in the environment of Hikaru's inner mind. This occurs after the non-sentient offshoots of Horizon and Maelstrom begin to appear and Maelstrom has resided within Hikaru long enough for her emotions to also change its perspective.

Horizon and Maelstrom eventually agree to help Hikaru save her friends and family because of a genuine desire to help Hikaru and because of the bond that has developed between them. The conversation between Horizon and Maelstrom employs a number of methods to show the emotional development that has occurred in both symbionts due to Hikaru's influence. Horizon and Maelstrom are portrayed as ‘light’ and ‘dark’ variations of Hikaru respectively, and their repetition throughout the pages during this scene controls its flow, as does the abstract space used to represent Hikaru's mind. This draws attention to not only the two aliens but also Hikaru's influence on them because of how the inner world of Hikaru is in certain respects their external world ().

Figure 8 Horizon and Maelstrom's cooperation show Hikaru's inner self being used as a kind of emotional utopian space. From: Tadano, N., Citation2011. 7 billion needles, vol. 3. New York: Vertical, Inc., 168-169. © Tadano Nobuaki. Reproduced with permission from the author

In this scene, the flow emphasizes the degree of change in the aliens through the aliens' visual similarities and differences. Horizon is depicted as a ‘light Hikaru’ consisting of almost no tones or shades, while Maelstrom is a ‘dark Hikaru’ reflecting the opposite, but the two are united by the fact that they are both represented as variations of Hikaru. This visual connection and contrast between them highlights their shared space inside of Hikaru, emphasizing the degree to which they have moved past their old statuses, reinforced by the fact that multiple panels feature Horizon smiling at Maelstrom, further suggesting Hikaru's influence. Hikaru's specific emotional perspective is shown to have caused this change, an evolution in them that has resulted in a re-evaluation of their own reasoning and values.

To some extent, 7BN can be seen as a work in the sekai-kei genre, often science-fictional narratives where ‘you and me’ relationships are central to the outcome of the world (Azuma Citation2007, p. 96). While this is potentially the type of dynamic, especially when presented as a romance, that threatens to overshadow the novum (Mendlesohn Citation2009, p. 15), the expression of these abstract visual environments and the characters within 7BN display the use of emotion as both alternative perspective and as potential logic. In regards to Horizon and Maelstrom in 7BN, it becomes increasingly clear that their perceptions of the world change as a result of their discovery of their emotions. The distinction between the internal and the external is made tenuous in an almost cyberpunk-like manner, where the distinction between hard and soft SF, and the literal and metaphorical, are broken down (Suvin Citation1991, Tatsumi Citation2006, p. 111) through the use of pages that draw attention to the characters and the use of backgrounds that are ambiguously perspectival yet also abstract.

Conclusion

Prominent depictions of character psychology, emotion, and affect are common in manga. While the creative and even political potential of emotions have already been seen in non-SF works such as Barefoot Gen, the aesthetics of manga can also transform the way in which emotions are viewed relative to science fiction. This article has provided a visual and narrative analysis of the SF manga 7 Billion Needles, which adapts a classic Western SF work into manga, to show how character psychology can act as an integral part of the SF narrative and the exploration of its environment by looking at how characters' emotional and affective responses are emphasized extensively through the use of visual techniques common to manga. These include panel flow, images that blend the internal world of character psychology and the external world of the SF environment, and the prioritization of groups of panels instead of individual ones. 7BN encourages the idea that emotions/affect cannot and should not be considered separate from the logical reality of their environments. The portrayal of subjective views, including the seemingly irrational ones, act as important parts of the world and its developments.

These visual and narrative expressions of emotion and the ways in which they permeate the pages of 7BN also demonstrate how emotions can act as an ‘alternative perspective’ or as a form of ‘potential logic’, such that character emotion can not only contribute to the elaboration of the novum, but is capable of even becoming, in whole or in part, a novum itself. 7BN shows how Japanese SF manga can play with the idea of what it means to be affected by the science fictionality of one's world by utilizing the inner psychologies of its characters as alternative, science fictional locations, which works to challenge and expand the very idea of how SF is meant to engender cognitive estrangement.

The portrayals of the characters in 7BN also show how science fiction and traditional character psychology-oriented fiction both similarly require people to be able to recognize the difference between reality and fictional narratives and then bring themselves to connect with the latter. This commonality, in turn, allows for a dual-level of interpretation that can act as a catalyst for a more direct and critical engagement with science fiction. The fact that there is, within the process of cognitive estrangement, a gap of variable size between the contemporary world and that of the SF narrative in terms of how one transforms into the other, can become an opportunity for readers to involve themselves in a greater level of interpretation, a cognitive investigation of emotion and affect, and by extension an opportunity to view critically the very act of cognitive estrangement itself.

Character emotion and affect as expressed in Japanese manga can thus be used to politically explore both paradoxes of science fiction, the process that can never be fully detailed, and the goal that is ever moving. The study of emotion in SF manga renders SF manga as a form of ‘affective science fiction’ that can potentially bridge seemingly disparate narratives and approaches to narratives in Japanese visual media, creating ambiguity in distinctions such as SF vs. non-SF, or modern vs. postmodern.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Goto-Jones, Dr. Florian Schneider, Dr. Martin Roth, and Mari Nakamura for their guidance, feedback, and criticism on the research presented in this article. I would also like to thank the Leiden University Institute for Area Studies for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carl K. Li

Dr Carl K. Li conducted research for this article as a PhD Candidate at Leiden University in the Netherlands. He specializes in the study of Japanese popular media and science fiction, and He may be contacted at [email protected].

Notes

1. A former manga editor for Kodansha, Chavez stated that flow is not only a common term in the industry but also that understanding flow is considered an important skill for both artists and editors (although this does not mean that a creator has to be a master of flow in order to be published). While the role of the editor in making creative decisions greatly increased starting in the 1990s (Kinsella Citation2000, pp. 162–163), which could in turn bias an editor towards certain methods, the fact that ‘flow’ plays a significant factor even well before the 1990s makes it clear that, even if the idea is simply shorthand to summarize page and panel composition in manga at the expense of full accuracy, the basis of the idea has persisted long enough to exert an influence on the visual art and visual language of manga.

2. This is not to make the mistake of saying that Tezuka is the creator of the story manga or that he did not have contemporaries also working and inspiring others, such as Yokoyama Mitsuteru and Tagawa Suihō. Rather, Tezuka, as the most famous and prolific manga creator, had a large influence on the industry and its creators.

3. It should be noted that, unlike Suvin who differentiates SF from fantasy, Bould considers a SF a type of fantasy where fantasy is not the Tolkien-esque genre commonly seen in media but more an emphasis on the fantastic.

4. Japanese titles that have been translated and published in English utilize their English names, while titles in Japanese use their Japanese names.

5. I must thank Dr. Chris Goto-Jones and Dr. Florian Schneider for helping me to develop the images used in and

References

- Adorno, T.W., 2004. The culture industry: selected essays on mass culture. J.M. Bernstein, ed. London: Routledge.

- Angenot, M., 1979. The absent paradigm: an introduction to the semiotics of science fiction. Science fiction studies, 6 (1). Available at: http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/17/angenot17.htm [Accessed 18 September 2015].

- Azuma, H., 2007. Gēmu-teki riarizumu no tanjō: Dōbutsuka suru posutomodan 2 [The birth of game-like realism: The animalizing postmodern 2]. Tokyo: Kodansha.

- Azuma, H., 2009. Otaku: Japan's database animals. Trans. J. Abel and S. Kono, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bolton, C., Csicsery-Ronay Jr., I. and Tatsumi, T., 2007. Introduction. In: C. Bolton, I. Csicsery-Ronay Jr. and T. Tatsumi, eds. Robot ghosts and wired dreams: Japanese science fiction from origins to anime. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bould, M., 2002. The dreadful credibility of absurd things: a tendency in fantasy theory. Historical materialism, 10 (4): 51–88.

- Carrier, D., 2000. The aesthetics of comics. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Carroll, N., 1998. A philosophy of mass art. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chavez, E., 2011. Interviewed by: Li, C.K. (11 July 2011).

- Clement, H., 1999. Needle. In: The essential Hal Clement, volume 1: trio for slide rule and typewriter. Framingham, MA: The NESFA Press, 21–204.

- Comic Natalie, 2012. Hagio Moto ga Shijuhōshō o jushō, shōjo mangaka dewa hatsu [Hagio Moto wins the Medal with Purple Ribbon, first shōjo manga creator to do so]. Comic Natalie, 28 April. Available at: http://natalie.mu/comic/news/68621 [Accessed 21 December, 2015]

- Duchamp, M., 1912. Nude descending a staircase (no. 2). At: Philadelphia Museum of Art. Accession number 150-134-59. Available at: http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51449.html. [Accessed 21 December, 2015]

- Ekman, P. and Davison, R.J, eds., 1994. The Nature of Emotion. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Fujimoto, Y., 2012. Takahashi Macoto: The origin of shōjo manga style. Mechademia, 7, 25–55.

- Groensteen, T., 2007. The System of Comics. Trans. B. Beaty and N. Nguyen, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

- Hagio, M., 1994. 11-nin iru! [They were 11!]. Shogakukan bunshō ed. Tokyo: Shogakukan.

- Hagio, M., 1995. Sutā reddo [Star red]. Shogakukan Bunshō ed. Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1995. Print.

- Hagio, M., 1997. A, A'. Trans. Matt Thorn. San Francisco: VIZ Communications, Inc.

- Hagio, M., 2011. Ware wa uchū (I the universe) [I am the universe]. In: S. Komatsu, Uchū ni totte ningen to wa nanika: Komatsu Sakyō Shingenshū; [What Are humans in regards to the universe?: a collection of Komatsu Sakyō quotes], 40–43. Tokyo: PHP Shinsho.

- Haraway, D., 1991. A cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In: Simians, cyborgs and women: the reinvention of nature. New York: Routledge. Available at: http://www.egs.edu/faculty/donna-haraway/articles/donna-haraway-a-cyborg-manifesto [Accessed 20 November 2013].

- Hatano, E. Chosha intabyū: Takemiya Keiko [Author interview: Takemiya Keiko]. Rakuten bukkusu. Available at: http://books.rakuten.co.jp/RBOOKS/pickup/interview/takemiya_k/ [Accessed 22 September 2015].

- Hoggett, P. and Thompson, S., 2012. Introduction. In: Thompson S. and Hoggett P., eds. Politics and the emotions: the affective turn in contemporary political studies. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 1–19.

- Itō, G., 2005. Tezuka is dead: postmodernist and modernist approaches to Japanese manga. Tokyo: NTT Shuppan.

- Jameson, F., 2005. Archaeologies of the future: The desire called utopia and other science fictions. London: Verso.

- Kajiya, K., 2010. How emotions work: the politics of vision in Nakazawa Keiji's Barefoot Gen. In: J. Berndt, ed. Comics worlds and the world of comics: towards scholarship on a global scale. Kyoto: International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University, 245–262. Available at: http://imrc.jp/2010/09/26/20100924Comics%20Worlds%20and%20the%20World%20of%20Comics.pdf.

- Keen, S., 2006. A Theory of narrative empathy. Narrative, 14 (3), 207–236. Available at: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/narrative/v014/14.3keen.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2013].

- Kinsella, S., 2000. Adult Manga. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press.

- Komatsu, S., 2006. SF damashī; [SF soul]. Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2006.

- Kotani. M., 2007. Alien spaces and alien bodies in Japanese women's science fiction. In: C. Bolton, I. Csicsery-Ronay Jr. and T. Tatsumi, Robot ghosts and wired dreams: Japanese science fiction from origins to anime.eds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kure, T., 1997. Gendai manga no zentaizō; [Overview of modern manga]. Tokyo: Futaba Bunshō.

- Lamarre, T., 2009. The anime machine: a media theory of animation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lamarre, T., 2010. Manga bomb: between the lines of Barefoot Gen. In: J. Berndt, ed. Comics worlds and the world of comics: towards scholarship on a global scale. Kyoto: International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University, 263–308. Available at: http://imrc.jp/2010/09/26/20100924Comics%20Worlds%20and%20the%20World%20of%20Comics.pdf.

- Le Guin, U.K., 1979. The language of the night: essays on fantasy and science fiction. S. Wood, ed. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Mendlesohn, F., 2009. The inter-galactic playground: a critical study of children's and teens' science fiction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Nakazawa, K., 2004. Barefoot Gen: a cartoon history of Hiroshima, vol.1. San Francisco: Last Gasp.

- Natsume, F., 2006. Where Has Tezuka Gone? In: P. Trophy, ed. Tezuka: The marvel of manga. Melbourne: Council of Trustees of the National Gallery of Victoria, 2006), 31–37.

- Palencik, J.T., 2008. Emotion and the force of fiction. Philosophy and Literature, 32 (2): 258–277. Available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/philosophy_and_literature/v032/32.2.palencik.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2013].

- Prough, J.S., 2011. Straight from the heart: gender, intimacy, and the cultural production of shōjo manga. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Sadamoto, Y., 2012-2013. Neon genesis evangelion, vol. 1–4. 3-in-1 ed. San Francisco: VIZ Media.

- Schodt, F.L., 1996. Dreamland japan: writings on modern manga. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press.

- Schodt, F.L., 1997. Manga! Manga! The world of Japanese comics. New preface ed. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

- Shamoon, D., 2012. Passionate friendship: the aesthetic of girls' culture in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Shouse, E., 2005. Feeling, Emotion, Affect. M/C journal, 8 (6). Available at: http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0512/03-shouse.php [Accessed 22 September 2015].

- Suvin, D., 1979. Metamorphoses of science fiction: on the poetics and history of a literary genre. London: Yale University Press.

- Suvin, D., 1991. An interview with Darko Suvin: science fiction and history, cyberpunk, Russia…. Interview by: Pukallus, H. Science Fiction Studies 18(2). Available at: http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/interviews/suvin54.htm [Accessed 30 May 2011].

- Tadano, N., 2010-2011. 7 billion needles, 4 vols. New York: Vertical, Inc.

- Takahashi, M., 2008. Opening the closed world of shojo manga. In: M. MacWilliams, ed. Japanese visual culture. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 114–136.

- Takemiya, K., 2007. To Terra, 3 vols. New York: Vertical, Inc.

- Tatsumi, T., 2006. Full metal apache: transactions between cyberpunk Japan and avant-oop America. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Thrift, N., 2008. Non-representationalism. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Walker, M.U., 1989. Moral understandings: alternative ‘epistemology’ for a feminist ethics. Hypatia, 4 (2), 15–28. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3809803 [Accessed 1 December 2013].

- Wegner, P.E., 2002. Imaginary communities: utopia, the nation, and the spatial Histories of modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yamano, K., 1994. Japanese SF, Its Originality and Orientation D. Suvin, ed. Science Fiction Studies, 21(62). Available at: http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/62/yamano62art.htm [Accessed 19 May 2011]