Abstract

Tourist guidebooks are powerful instruments of public diplomacy: as supposedly ‘impersonal’ descriptions, intended for ‘average’ readers, they can be used to subtly promote careful national narratives, and to draw the attention of foreign publics to a country’s soft power. This article analyses, in this light, the English-language tourist guidebooks of Japan published by the Society called Kihinkai (Welcome Society, 1893–1912), the earliest Japanese organization for the promotion of inbound tourism. It relates them to the popular handbooks of Japan published by the British House of Murray, which were adopted as their model. Murray’s handbooks ‘created’ Japan as an international tourist destination for a majority of English-speaking travellers, responding to common travel tropes and expectations about the country. The Kihinkai’s guidebooks engaged with them in the form of ‘autoethnographic’ texts, adopting their style and language, as a way to partake in their established reputation of authoritativeness. At the same time, they carefully reframed their narrative of Japan, in a way that was coherent with the Kihinkai’s general ‘diplomatic’ strategy – born of the background of its founders and supporters, and of the coming together of private and public sector interests.

Introduction

This article looks at the English-language tourist guidebooks of Japan published by the Society called Kihinkai (喜賓会; in the official translation: Welcome Society; 1893–1914), as a case study in the geopolitics of international tourism. The Kihinkai was the first Japanese organization for the promotion of inbound tourism. Fuelled by both private and public sector interests, it was specifically aimed at welcoming visitors from ‘Western’ countries. The article discusses how its English-language pamphlet maps and guidebooks took inspiration from an authoritative model, the handbooks of Japan published between 1884 and 1913 by the British House of Murray, but adjusted it so as to build a careful narrative of the Japanese nation, as part of an early experiment in public diplomacy. It argues that, in the Meiji period, tourist guidebooks of Japan became part of a complex process of negotiation of national identity, aimed at establishing Japan’s economic position and international reputation.

Public diplomacy is ‘an instrument that governments use to mobilize […] resources to communicate with and attract the publics of other countries […]. Public diplomacy tries to attract by drawing attention to these potential resources through broadcasting, subsidizing cultural exports, arranging exchanges’ (Nye Citation2008, 95). Those ‘resources’ are what constitutes a country’s ‘soft power’, and they encompass the ‘attractive’ elements of its culture, as well as its political values and foreign policies (Nye Citation2008, 96). Guidebooks are a powerful instrument of place and nation-branding (Kim and Yoon Citation2013) and can be used to enhance soft power. While marketed as objective and exhaustive compendia of information for a generic traveller, they are no less partial and subjective than personal travel narratives.

Japanese tourism has been at the centre of a recent surge in publications (Funck Citation2018) that has brought attention, among other topics, to the use of tourism policies in public diplomacy (Leheny Citation2003; Daliot-Bul Citation2009; Utpal Citation2010; Jing Citation2012; Hall and Smith Citation2013; Ruoff Citation2014; Iwabuchi Citation2015; McDonald Citation2017; Elliot and Milne Citation2019). Tourism in the Meiji period (1868–1912), however, has yet to be explored in depth in this light. Research dealing with international travel to Meiji Japan has focused mostly on personal narratives (travel diaries and private and official correspondence) as well as on the periodical publications, and fictional and poetic works born of the cultural encounter between Europe and Japan (Yokoyama Citation1987; Cortazzi Citation1987; Cortazzi Citation2000; Sterry Citation2009; Wisenthal Citation2006; Lee Citation2010; Bird and Kanasaka Citation2018). Guth (Citation2004) has expanded on the experience of one traveller, Charles Longfellow, broadly discussing the position of Japan in nineteenth-century round-the-world travel and tourism. Best (Citation2021, 44–49) has discussed the geopolitical implications of British tourism in Japan in the context of the phenomenon of globe-trotting. However, the way a developing tourist industry in Japan engaged with foreign travellers and their expectations, in the development of growingly centralized and geopolitically coded policies for inbound tourism, has received less attention, above all in English-language literature. Tourist guidebooks, moreover, have only been marginally analyzed, mostly in works focused on later time-periods, and with no specific focus on public diplomacy (Satow Citation1996; Konno, Soshiroda, and Hanyu Citation2002; Satoi et al. Citation2003; Akai Citation2009; Furuya and Nose Citation2009; Kawauchi Citation2020).

This article, which aims at filling this gap in the literature, will be articulated into three main sections. The first one will discuss the development of a market for English-language guidebooks of Japan in the Meiji period. The second will discuss the way Murray’s handbooks ‘created’ Japan as a tourist destination for foreign visitors, by incorporating common tropes and expectations of nineteenth-century European travellers. The third section will look at how the Kihinkai adapted the style and language of Murray’s handbooks in its publications, as a calculated way of presenting ‘Japan’ to the world. It will show how the Kihinkai’s attempt at turning the ‘private’ experience of travel into a ‘public’ matter paved the way to later national involvement in the management of tourism.

The publication of English-language guidebooks of Japan in the Meiji period

In the 1870s, as the political and diplomatic tensions that had accompanied the Meiji Restoration eased, Japan developed into an international tourist destination. European and North-American residents in the tropical areas of Asia and Australia came to favour the country in light of its milder climate (Shirahata Citation1985a, 84). Moreover, at a time when a new culture of mass tourism was in full development and globe-trotting was taking the place of European touring for the wealthy (Buzard Citation1993; Buzard Citation2002), and in light of Japan’s fortunate location on steamship routes (Funck and Cooper Citation2013, 31–32), a growing number of tourists reached Japan from Europe and North America. It is estimated that, by the 1890s, foreign visitors amounted to roughly seven or eight thousand people per year (Shirahata Citation1985a, 87), a figure that rose to 15,650 by 1910 (Leheny Citation2003, 55). The standard visit, facilitated by the new railway network, lasted usually no less than a few weeks, and up to three or four months (Sterry Citation2009, 17).

In this context, a market developed for English-language guidebooks of Japan.Footnote1 Since the 1830s, John Murray, of the House of Murray (London), had become a dominant figure in the market for guidebooks in Europe (Butler Citation2018). His works, named ‘handbooks’ in light of their portability, had an established reputation of reliability and exhaustiveness. In 1881, Kelly & Co published in Yokohama a Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan (Satow and Hawes Albert Citation1881). The authors, Ernest Mason Satow and Albert George Sidney Hawes (respectively an employee of the British Minister in Japan and an advisor for the Japanese government in army training) took direct and explicit inspiration from Murray, stating that they had chosen to follow his model as far as was practicable (Satow and Hawes Albert Citation1881, preface). Murray himself published the second edition in 1884 (Satow and Hawes Albert Citation1884). The third edition was revised and expanded, as A Handbook for Travellers in Japan, by Basil Hall Chamberlain, professor at Tokyo Imperial University, and W.B. Mason, member of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society and collaborator of the Japanese Ministry of Communications (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1891). After it sold 2,750 copies in Yokohama alone (Best Citation2021, 45), six further editions, progressively augmented, were published in response to growing demand.Footnote2 All included maps and tables, and had the same basic structure: an introduction with general practical information and a presentation of Japan – which, in line with the style of many nineteenth-century travelogues (and with the scholarly background of the authors), catalogued and classified the country for the tourist, in terms of language, physical and political geography, landscapes and natural resources (climate, fauna and flora), religions (Shinto and Buddhism) and arts; and a list of itineraries, each providing practical, historical and topographical information – and, sometimes, legendary narrations – about the listed localities.

Murray’s handbooks became an inspiration for other English-language guidebooks published in Japan in the 1880s. In 1888, Kelly & Walsh (that had incorporated Kelly & Co. in 1885) published a guidebook by the explorer and collector Heywood Walter Seton-Karr, which explicitly mentioned the Handbook as a source (Seton-Karr Citation1888, iii). In 1880, Adolfo Farsari published the very successful Keeling’s Tourists' guide to Yokohama (Keeling Citation1880), initially marketed as a local guidebook, focused on localities of easy access from open ports. In the 1884 edition, it explicitly listed the Handbook among its references (Keeling Citation1884, 9), but the mention disappeared in later editions (Citation1887 and Citation1890), where, even if the itineraries’ section was never significantly expanded, the title changed into Keeling's guide to Japan (revealing, perhaps, an ambition to compete with Murray).

A number of Japanese authors also entered the market in the late 1880s and drew heavily both on Murray’s Handbook and Keeling’s Guide. In Citation1887, Tomita Gentarō’s Tourist’s handbook was published in Yokohama by the Japanese photographer Tamamura. It was mostly a verbatim copy of Keeling’s guidebook, with some edited sections. In 1891, the same author published, with the London, Hong Kong and Yokohama based publisher Kelly and Walsh, a Tourist’s Guide and Interpreter, a 187-pages guidebook structured partly as a language guidebook,Footnote3 and partly as a tourist guidebook, following (in compact form) the pattern of Murray’s itineraries. Similar guidebooks, for a total of roughly 25 titles, were produced by five other Japan-based publishers (Maruya, Seibisha, Modern English Association, Naigai Chūkaisha, Ōbun Printing) at around the same time (Satoi et al. Citation2003, 390). The most successful one was Watanabe Genjirō’s Guidebook for tourists in Japan (by Maruya), appearing in four editions between Citation1898 and 1906. The Handbook was so consistently copied and adapted that Chamberlain and Mason started protesting against the publication of guidebooks that were too explicitly modelled after it, which ended up delaying the publication of the first Kihinkai guidebook by four years.Footnote4

In 1902, Maruya also published Hotta’s Up-to-date Guide for the Land of the Rising Sun, which stood apart from others in that it was specifically created in preparation to the Fifth National Industrial Exhibition in Osaka (1903). While structured in a way similar to previous English-language guidebooks, it presented novel and up-to-date information, supplied directly by railway and steamship companies and by Japanese public authorities. The guidebook was also carefully worded to highlight recent Japanese achievements in modernization, particularly the ‘remarkable progress’ made since the 1894–1895 Japan-China War (Hotta Citation1902, 1), and had updated travel itineraries that covered the expanding Japanese empire. While this guidebook, as stated in its preface, was meant to be revised annually, it didn’t appear in any further edition. This was perhaps because, in the meantime, the Kihinkai had begun to release its own publications, and they relied on similar sources and, as we’ll see, similarly highlighted Japan’s modern achievements.

The ‘creation’ of Japan as a destination for foreign tourists in the Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan

How did Murray’s influential Handbook present ‘Japan’? The average readers of the guidebook, with the exception of a limited number of connoisseurs, knew about the country from what could be gathered from popular periodical publications in Europe and from the artistic fad of Japonisme, and found in Japanese culture an ‘amusing and fashionable diversion from European orthodoxy’ (Best Citation2021, 43). The authors of the Handbook took it upon themselves to introduce Japan to these ‘amateurs’, guiding travellers in more than just facilitating their journey. They offered a ‘correct’ interpretation of the country, as a place that was outright ‘other’ to Europe:

In Japan, more than in any Western country, it is necessary to take some trouble in order to master […] preliminary information; for whereas England, France, Italy, Germany, and the rest, all resemble each other in their main features, because all have alike grown up in a culture fundamentally identical, this is not the case with Japan. He, therefore, who should essay to travel without having learnt a word concerning Japan's past, would run the risk of forming opinions ludicrously erroneous. (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 2)Footnote5

The way the above passage presents Europe as a cultural unit was not a given. Most contemporary British guidebooks actually highlighted cultural differences within the European continent, and a ‘residual distrust of foreign parts’ (Ousby Citation1990, 10) permeated, in particular, many publications about France and Italy. In the Handbook, the heterogeneity of Europe was downplayed as a way to highlight Japan’s difference. This was, of course, a common simplification in negotiating the identity of the ‘East’ as opposed to the ‘West’, but, in the context of a travel guidebook, it can also be seen as a way of coding Japan as a specific type of destination: one for people who still had in themselves the adventurous attitude of old-timed ‘travellers’, wishing to go off the more beaten tracks (such as the European Grand Tour) as a way to learn about the variety of human experience, and to challenge common stereotypes of superficiality associated with ‘tourism’.Footnote6

This connects with what is arguably the dominant narrative about Japan in the Handbook: ‘picturesque’ discourse. Japan is introduced in the guidebooks as ‘more especially the happy hunting-ground of the lover of the picturesque’ (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 12). The term ‘picturesque’ recurs 146 times in the seventh edition and is heavily relied on to characterize Japan as a destination. This aesthetic category had been an integral component of the increasing popularity of travel in eighteenth-century England. It referred both to a type of landscape that ‘observers would experience pleasurably, yet which fell outside the definitions of both sublime and beautiful’ (Forsdick, Kinsley, and Walchester Citation2019, 184) and to a travel experience centred on this kind of landscape and on the discovery of beauty (Alù and Hill Citation2018). It was a component of the traveller gaze, rather than of the landscape per se. Postcolonial studies have underlined how picturesque discourse was a common way for British travellers to deal with the foreign, familiarizing and ‘othering’ it at the same time: it displayed landscapes and people as if in a museum – as exotic and curious, but at the same time accessible and ordered (Ray Citation2013; Hill Citation2017; Sinha Citation2020).

Picturesque discourse was certainly not unique to the Handbook: it abounded in contemporary popular periodical publications about Japan (Yokoyama Citation1987) and was a central component in the way the Japanese landscape and life was mediated in European art through Japonisme (Lippit Citation2019). It resonated with Japan’s growing reputation as an ‘exotic’ destination that was comparatively ‘tame’, comfortable and safe to travel in even for female lone travellers. Japan lacked, in fact, the element of challenge of open-for-conquest colonized lands, and also worked as a foil for China, a country that appeared as far more menacing in popular European, and particularly British, representations, as a consequence of the Opium Wars (Sterry Citation2009, 12). This reputation shaped the expectations of prospective travellers, and may have been one reason why Japan seemed to recurrently evoke ambivalent feelings of difference and familiarity in globetrotters.Footnote7

The Handbook’s picturesque discourse played on these ingrained expectations and paradigms of representation. In the book, the category of the picturesque encompassed the natural beauty of the country, which ‘produces the impression of having been planted for artistic effect’ (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 12), but was also recurrently used as a descriptor for Japanese life in general: ‘Here, in April, all Tokyo assembles to admire the wonderful mass of cherry-blossom for which it is famous. No traveller should miss this opportunity of witnessing a scene charming alike for natural beauty and picturesque Eastern life’ (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 128). The Japanese themselves were described as ‘the most esthetic of modern peoples’ for which the picturesque was a ‘fitting abode’ (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 12). Picturesque discourse was, in this sense, the way in which the Handbook fit Japan into a canonical, manageable interpretation, displaying its natural beauty and lifestyle as a metaphorical piece of art to look at. In doing so, it associated Japan with a specific brand of exoticism, coding it as a place where European tourists would be able to have an ordered taste of the curious.

Other elements in the Handbook contributed to this narrative. The guidebook promised an overall familiar and pleasant experience of leisure in Japan:

Travellers’ tastes differ widely. Some come to study a unique civilization, some come in search of health, some to climb volcanoes, others to investigate a special art or industry. Those who desire to examine Buddhist temples will find what they want in fullest perfection at Kyoto, at Nara, at Tokyo, and at Nikko. The chief shrines of Shinto are at Ise, and at Kitsuki in the province of Izumo. The “Three Places” (San-kei) considered by the Japanese the most beautiful in their country, are Matsushima in the North, Miyajima in the Inland Sea, and Ama-no-Hashidate on the Sea of Japan. Persons in search of health and comparative coolness during the summer months to be obtained without much “roughing”, are advised to try Miyanoshita, Nikko, or Ikao in the Tokyo district, Arima in the Kobe district, or (if they come from China, and wish to remain as near home as possible) Unzen in the Nagasaki district. All the above, except Kitsuki, may be safely recommended to ladies. Yezo is specially suited for persons residing in Japan proper, and desiring thorough change of air. At Hakodate they will go sea-bathing, and in the interior a little fishing and a peep at the Aino aborigines. (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 11–12)

At the same time, it reassured its readers that the experience of tourism in Japan would be ‘different’ enough. It focused, for example, on the (mild) nuisances that European travellers were bound to face in the country: fleas in beds and foul smells in inn rooms (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 15), the lack of accessibility to European food (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 9), the bad state of roads (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 11). It also remarked on the not always pleasant unusualness of people:

The ways of the Japanese bourgeoisie with regard to clothing, the management of children, and other matters, are not altogether as our ways. Smoking is general even in the first-class, except in compartments specially labeled to the contrary; but which are not often provided (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 12).

This trope of uneasiness on the road, not uncommon in British travel writing in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (Ousby Citation1990), rather than discouraging tourists, added another fascinating layer of ‘old-timed discomfort’ and curiosity to the experience of tourism in Japan.

Picturesque discourse in the Handbook was also ingrained in a recurring narrative about the aesthetic perils of modernisation. The picturesque didn’t inherently exclude modernity and industrialisation. In late eighteenth century England, artists had actually adapted it to include representations of industrial sites, and even industrial catastrophes (Fyfe Citation2013). In the Handbook, however, picturesque discourse is virtually inseparable from a romantic lamentation about the impending loss of the beauty of the past.

[Hikone] castle was about to perish in the general ruin of such buildings, which accompanied the mania for all things European and the contempt of their national antiquities […]. It so chanced, however, that the Emperor, on a progress through Central Japan, spent a night at Hikone, and finding the local officials busy pulling down the old castle, commanded them to desist. The lover of the picturesque will probably be more grateful to His Majesty for this gracious act of clemency towards a doomed edifice than for many scores of the improvements which the present government has set on foot. (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 361)

Since 1869, a great change has taken place in the outward appearance of [Tokyo]. Most of the yashiki, or Daimyos' mansions, have been pulled down to make room for buildings in European style, better adapted to modern needs. The two-sworded men have disappeared, the palanquin has given place to the jinrikisha, and foreign dress has been very generally adopted by the male half of the population. But Tokyo is picturesque enough, and, as seen from any height, has a tranquil and semi-rural aspect owing to the abundance of trees and foliage. (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 115)

The one exception to this narrative are the new railways, generally presented in a positive light, as vantage points for observing the beauty of Japanese nature: ‘Between Yotsukura and Hirono lies the most picturesque portion of the N.E. Coast Railway. Spurs of the hills run down to the shore; and as the train emerges from the tunnels […], delightful sea-views appear at every opening’ (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 225–226). This was coherent with the railways’ role in facilitating movement, and more generally with dominant ‘modern’ patterns of travel where ‘what is known, or worth knowing about a place, is what can be seen on the route to somewhere else’ (Ousby Citation1990, 18). Still, even the railways don’t seem to hold up to the picturesque nature of old travel by road, above all along historic highways such as the Tōkaidō, which retained ‘some of the bustle and picturesqueness of former days’ (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 358), and where travellers could indulge in the old-timed experience of travel by jinrikisha (pulled rickshaw).

In this sense, in the Handbook, picturesque discourse also builds a narrative of opposition, between what is modern/European and what is traditional/Japanese. The ‘picturesque’ wasn’t only a familiar category that produced a ‘tamed’ reading of Japan, but was also associated to the ‘endangered’ elements that marked Japan’s difference. The social and cultural change that was taking place in Meiji Japan had become hard to ignore in the 1880s, and elicited very different responses in different foreign observers, ranging from ridicule to open praise (Best Citation2021, 47–51). The Handbook seems to take a sort of middle ground: it doesn’t belittle the change, and even recognises its necessity in light of Japan’s need to preserve its independence (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 1), but responds to it with a sense of anxiety, presenting Europeanisation and modernisation as an ongoing threat to what, in Japan, is of true appeal to the tourist:

Japan, great as is the power of imitation and assimilation possessed by her people, has not been able completely to transform her whole material, mental, and social being within the limits of a single lifetime. Fortunately for the curious observer, she continues in a state of transition,—less Japanese and more European day by day, it is true, but still retaining characteristics of her own, especially in the dress, manners, and beliefs of the lower classes. Those who wish to see as much as possible of the old order of things should come quickly. (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 2)

This doesn’t mean that the Handbook provided a structured commentary on (or argument against) modernity, either in general or in reference to Japan. Rather, its nostalgic attitude towards Japan’s past resonated with a number of contemporary popular fads in European literature and art – in particular with ‘picturesque history’, a visual and textual trend that had contributed to the popularization of history in the English-speaking world, since the 1830s (Fleming Citation1995; Mitchell Citation2000). Picturesque history shared with ‘the more general Victorian culture of medievalism a love of the Romantic, […] a fascination with false origins and half-understood science, and a habit of collecting historical details and then pasting them together to form a grand, anachronistic whole’ (Fleming Citation1995, 1061). As Best (Citation2021, 41) discusses, one reason for the popularity of Japanese culture in Europe was indeed the resonance of some of its elements – its folk heritage, and the tradition of chivalric honour among the samurai class – with this culture. This probably accounts for the centrality assigned to religion and history in the choice of contents of the Handbook, explicitly mentioned in the introduction (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 2).

In this sense, in describing Japan’s picturesque, the Handbook associates the country with what I would define as a particular brand of ‘nostalgic exoticism’. It is in respect to this picturesque discourse that the guidebooks published by the Kihinkai more markedly diverge from the Handbook.

The Kihinkai and its publications

The Kihinkai was a non-profit organization for the promotion of inbound tourism. It was born by private initiative, and sustained by donations from private companies (railway companies, international shipping companies, and other businesses that had vested interests in tourism), but its founders and members had strong connections with the government. This has led Nakamura (Citation2006) to describe it as a half-public, half-private organization. Its three key promoters were Shibusawa Eiichi (1840–1931), former member of the Ministry of Finance, lead businessman and president of the Tokyo Chamber of Industry and Commerce; the vice-president of the Tokyo Chamber of Industry and Commerce, Masuda Takashi (1848–1938), a former samurai who had served the Meiji government as interpreter and diplomat before becoming head of Mitsui Trading Company in 1876; and Hachisuka Mochiaki (1846–1918), former diplomat, who was appointed president of the Kihinkai in light of his business connections and of his rank as President of the House of Peers. Among the activities they planned for the Society – which included bringing the hospitality industry in Japan up to ‘Western’ standards, creating a reliable network of guides, producing letters of introduction for tourists, and generally promoting good personal relations between foreign visitors and members of the Japanese upper classes – great importance was assigned to the publication of tourist maps and guidebooks. They were to be provided for free or for a small fee to all foreign tourists who registered at the Kihinkai Main Office upon their arrival, and to be sent to European and American distributers abroad, as ways to attract visitors.Footnote8

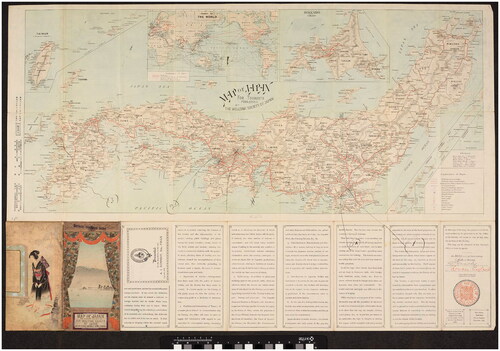

The first publication by the Kihinkai was a foldable pamphlet entitled Map of Japan for Tourists. It was first published in 1897 and revised in ten further editions between 1899 and 1913 ().Footnote9 They featured a large map of mainland Japan (Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū), and ancillary maps of Hokkaidō (Yezo), Taiwan (Formosa Islands), Okinawa (Lochoo Islands) and of the smaller islands in the Okhotsk Sea, such as Chishima (Kurile Islands) and Ogasawarajima (Bonin Islands). With the expansion of the Japanese empire, they came to include Karafuto (Saghalien). The Kihinkai also began to publish a separate Map of Manchuria, Korea, Formosa, and Saghalien (two editions, in 1908 and 1910). The maps, styled according to modern Western cartography, gave prominence, in iconography, to tourist spots (‘notable places’), to physical and political geography (with a related glossary and legend), and, above all, to routes: railways (not only those already open to traffic, but also those under construction or for which a charter had been granted), roads, railway stations, steamer lines, light houses, anchorages. In its first edition, the map also included a small chart of the world, with Japan at its centre, again depicting railway and steamer routes around the world, including regular and occasional steamer lines. This chart was excluded from later editions, perhaps as a sign of a shift of interest from routes to Japan to routes within the country. Conversely, information related to Japan was progressively expanded with the inclusion of city maps for Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo (in 1912, the Kihinkai also published a separate Latest Map of Tokyo, Yokohama, Hakone, Fujiyama, and Nikko), and of data on railway mileage and distances within the country. Ousby (1990, 18) observes that the creation of ‘modern’ guidebooks was coupled in Britain with a change in the conventions of mapping, with growing emphasis put on roads and routes. The Kihinkai’s guidebooks do seem to follow this pattern.

Figure 1 ‘Map of Japan for Tourists, published by the Welcome Society of Japan’, 1897, 865 × 575 mm, lithography, Manchester Digital Collections, Japanese Maps Collection, The University of Manchester Library (https://www.digitalcollections.manchester.ac.uk/view/PR-MGS-FOLDED-D-00020-00105/1.

The pamphlets were soon coupled with longer publications. A 116-page illustrated booklet titled A Short Guide Book for Tourists in Japan was published in 1905. In 1906, this was expanded in a 253-page second edition titled Guide-Book for Tourists in Japan, including a new section on Korea. Three other editions were published in 1907, 1908 and 1910, and came to expand the section on Korea and to also include Manchuria. The guidebooks were complemented with a series of booklets titled Useful Notes and Itineraries for Travelling in Japan, published from 1905 onwards.Footnote10 They were a sort of compact version for travellers planning shorter stays in Japan, distributed for free to tourists who registered at the Society’s office.

The Guide-Book series acknowledged the Handbook’s authoritativeness and influence. It recommended it as a reference, rather than presenting itself as a potential commercial competitor:

The compiler, however, recommends to every earnest tourist to provide himself with "Murray's Hand-book for Japan," an excellent work, compiled by Prof. B. H. Chamberlain and Mr. W. B. Mason; which contains minute and accurate information on travelling and sight-seeing in Japan. (The Welcome Society Citation1906, preface)

This was coherent with the Kihinkai’s nature as a non-profit organization, but it does raise some questions. When an ‘excellent’ guidebook was already available, why was it at all necessary for the Kihinkai to put out its own publications? Publishing was an expensive endeavour, and it ultimately proved to be economically unsustainable for the Society: after the Russo-Japanese war (1904–1905), and the ensuing recession and nationalization of private Railways, it became harder and harder for the Kihinkai to support itself through donations, and while the Japanese Government Railways helped by buying its publications in bulk and distributing them, in the end their cost was one of the reasons why the Kihinkai had to cease its activities (Shirahata Citation1985a, 87–88). I argue, however, that the reason why the Guide-Book was published had to do with a perceived necessity to offer an ‘amended’ narrative of Japan, a necessity that emerges from the Guide-Book’s additions and omissions with respect to its model.

Why the Handbook was adopted as a model in the first place is, in itself, worth discussing. Travel guidebooks had already been part of the editorial culture of Japan in the Edo period (1603–1868): the Kihinkai could have looked for reference, for example, at meisho zue (illustrations of famous places), a staple of the late-Edo complex domestic tourist industry (Nenzi Citation2004; Nenzi Citation2008). Ousby (Citation1990) observes how Murray’s handbooks and other similar ‘impersonal’ guidebooks contributed to the creation of a tourist map of England by formalising, for an average ‘tourist’, patterns of travel that originally reflected the taste and outlook of a specific class. Meisho zue, too, were products of a ‘partial’ cultural perspective, driven by class and geographical belonging (Nishino Citation2011) but made to address a vast, ‘average’ readership (Goree Citation2017). Murray’s handbooks, however, were a more palatable model for the Kihinkai in several respects: their structure (the portable format, the dominant presence of text over images, the creation of itineraries following major railway routes, and the use of maps to highlight those routes) better reflected the new patterns of travel and tourism that were being systematised by the development of ‘modern’ means of transport; foreign readers would find their language and style immediately familiar; they had an established international reputation of authoritativeness; and, contrary to meisho zue, they presented ‘Japan’ as a whole, distinct and unified national entity. It is worth mentioning that meisho zue were also being gradually discontinued in the domestic market, as new Japanese-language guidebooks were produced following European standards – at a time when, more generally, the taste and habits of foreign travellers were influencing domestic travel, promoting new tourist spots and leisure activities (Traganou Citation2004, 123–124). In this sense, foreign handbooks had an impact on the birth of a ‘national’ and ‘modern’ tourist map of Japan that was strongly influenced by an external tourist gaze.

In this context, the Guide-Book may be read a form of ‘autoethnography’, in the definition given by Pratt (Citation1992, 35): a description of the self that engages with representations made by a dominant ‘other’ – in the Guide-Book’s case, representations incorporated and summed up in Murray’s handbooks – and appropriates their language, styles and images, as a way to enter into the dominant group’s linguistic, cultural and social domains. The Guide-Book adopted the Handbook’s style, basic structure, and at least partially, the tourist map it traced for Japan: the Handbook was structured in nine sections, with a main focus on the most popular travel destinations among foreign visitors (located between Sendai and Matsushima in northern Honshū and Itsukushima in the Seto Inland sea), but also on ‘off-the-beaten-track’ beauty spots in Kyūshū, Shikoku and Hokkaidō, and on some of Japan’s colonial possessions; the Guide-Book condensed this into three sections – North-Eastern Japan (including Hokkaidō), Central Japan, and South-Western Japan (including localities in Kyūshū and Shikoku, and Japanese colonies) – presenting roughly the same locations, in re-arranged order and succinct form.

However, the Guide-Book followed a very different order of priorities in describing the locations. An example is the section on Tokyo: in the Handbook, it opened with a long and detailed description of Shiba Park’s temples and shrines (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 115–122), which was reduced to a single paragraph in the Guide-book, leaving more room – even in the overall reduced page-space – to the description of hospitality venues (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 12) that were only mentioned in passing in the Handbook (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1903, 121). This emphasis on hospitality was coherent with the reasons why the Kihinkai was originally created. Masuda came up with the idea of a Society for the promotion of inbound tourism after a journey to France in 1887 convinced him of the business potential of the tourist industry for creating a better balance of trade for Japan (Shirahata Citation1985a, 84). It made sense, in this light, for the Guide-book to focus on pushing visitors towards venues where they could spend their much welcomed foreign currency.

The Guide-Book, however, appears to be more than just a glorified collection of advertisements. It made a series of careful narrative choices. Picturesque discourse, as it had been framed in the Handbook, was pointedly removed from it. This was not obvious or necessary: ‘picturesque’ expectations by foreign visitors were openly embraced in other contexts, as a way of shaping and promoting Japan’s national heritage (Vitale Citation2021). The choice was, however, coherent with the way Guide-Book consistently downplayed nostalgia in representing Japan’s heritage. One example is the way the Guide-Book presented Hikone and Tokyo, as opposed to how they had been described in the Handbook:

Hikone […] was formerly the castle town of the celebrated Daimyo called Ii Kamon-no-Kami who was assassinated at the Sakurada gate of Tokyo in 1860 because of his supposed desire to open the country to foreign intercourse […]. The renowned castle is now partly turned into a public garden from which a fine view of Lake Biwa may be enjoyed. A branch line runs to Kifugawa (26 m.) where it connects with the Kwansai Railway via Takaraiya (2 m.), Yokaichi (12 m.) and Hino (19 m.). (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 89)

Tokyo was formerly called Yedo, and was merely a collection of several poor villages. In the era of Choroku in the 15th century, Ota Dokwan, a retainer of Lord Uesugi, built a small fortress in the hamlets of Chiyoda and Takarada. In 1590, Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Dynasty, came here and thirteen years later he made the castle his military head-quarters. At the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868 when the Shogunate system was abolished, the Imperial court was removed to Yedo, the name of which at the same time was changed to Tokyo or “Eastern Capital”. The river Sumida flows through the eastern portion of the City and is spanned by five iron bridges. The city is divided into fifteen districts […] It has four railway Termini […]. (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 9)

The Guide-Book’s narrative still made reference to the locations’ history. However, rather than dwelling on a sense of loss of what was, and on the urgency to preserve the vestiges of the past, it presented the progression from the past to an ‘europeanised’ present as organic: a ‘natural’, not especially regrettable aspect of Japan’s modernity.

Not only the change was not regrettable, it offered new opportunities to travellers. The Guide-Book actively directed the tourist’s attention towards the modern and the urban. At the very beginning, it listed a number of tourist sites to which visitors were encouraged to get special access through the Kihinkai (The Welcome Society Citation1906, iii–vii). The sites stand apart from those listed in the itineraries, in that they aren’t ‘typical’ tourist spots: aside from a small number of museums, mansions and gardens, they mostly consist of universities, schools, hospitals, prisons, governmental buildings, observatories, experimental stations, marketplaces, as well as factories, manufacturing plants and mines – in other words, in landmarks of Japanese modernity. The Kihinkai and its guidebooks pushed visitors towards them, and towards a reading of Japan that embraced its industrial and modern present, rather than lingering on a disappearing past.

The Guide-Book also attempted to generate tourist interest about Japan’s colonial expansion. It was phrased in ways that would subtly support Japan’s transformation into a colonial power – its aggressive foreign policies and its colonial interests in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese war. The 1906 edition came to include several references to a supposed history of dominance of Japan over Korea: to Empress Jingū’s historically contested invasion in the 3rd century (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 4), for example, and to the (debatably) successful nature of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaign in the sixteenth century (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 168). The Guide-Book also added, in rather triumphal tones, the location of Tsushima battle to the Japanese tourist map, as the place ‘where the greatest naval battle of modern times was fought’ (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 227–228), reflecting developing trends of battlefield tourism (as described by McDonald [Citation2019]). In the description of Korea itself, finally, it focused rather heavily on Japanese military history and occupation:

The ruins of an old castle located near the station was built by Konishi Yukinaga, a general in Toyotomi Taiko’s expedition some 300 years ago”. Seikwan “(220m.) is well-known as a battle field of the Chino-Japanese War. After leaving this station the train crosses a river named Anjo-gawa which is spanned by a bridge […]. On a dark night of the 27th July, 1894, the late Capt. Matsuzaki, a brave champion of the above campaign, crossed the river with a small party of only 27, and fought with great courage against the enemies who shot them from the inside of the farm houses near at hand. […] The water of the harbour is sufficient for the anchorage of large vessels. Its trade is mostly carried on by the Japanese, whose settlement has a population of some 18,000 and its total sum for the last year was ¥ 12,084,074. (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 229)

The way the Guide-Book’s introduction was structured, finally, reinforced the idea that Japan’s modernity could not be set apart from European modernity in any fundamental sense. While including the expected compilation of practical hints (on journey planning, lodging, regulations, conventions, railway routes) and a short guide to the Japanese language, it skipped over any general presentation of Japanese history, art and religion. This choice may have been a simple concession to the reduced page-number, but it doesn’t appear to be completely neutral: it implicitly refutes the Handbook’s presentation of Japan as a place that needs ‘explanation’, as fundamentally ‘other’ than Europe. It’s also worth noting, in this respect, that the Guide-Book’s introduction lacked any concessions to the curious, and downplayed the Handbook’s recurrent narrative about travel discomfort.

Most of the principal cities (Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka), the open ports (Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki) and other famous places (Miyanoshita, Kamakura, Nikko, Ikao, Sendai, Shizuoka, Nagoya, Takarazuka and Shimonoseki, etc.) have hotels conducted in foreign style. […] In less important places frequented by foreign visitors, there are semi-foreign hotels and high class Japanese style inns, well conducted and neatly kept, and in some of these inns foreign dishes may be served (The Welcome Society Citation1906, xxii–xxiii).

This didn’t only highlight the results obtained by the Society in reforming hospitality, but it also deemphasized the narrative of ambivalence between familiarity and exoticism that had been dominant in the Handbook’s representation of Japan.

This marks an interesting contrast in tone with other guidebooks of Japan produced in the wake of Murray’s. Keeling, for example, was pretty eager to report curiosities and oddities – the ‘repulsive custom’ of the blackening of married women’s teeth, for example, or the scandalous promiscuity of mixed-gender public baths (Keeling Citation1890, 36). This happened at a time when the Meiji government was actively trying to eradicate those customs, with the implementation of Ishiki kaii jorei (Petty misdemeanors ordinances) in Tokyo (1872) and in other open ports and cities of Japan (1873–1875). The ordinances, which regulated public order and safety, public hygiene and general morality (including bans on public nudity, public urination, and mixed-gender public baths), were coupled with unofficial pressures for men to adopt Western-styled clothes and hair, and for women not to shave their eyebrows and blacken their teeth after marriage (Hirano Citation2013, 217). Often modelled in response to direct observations made by European and American travellers (Cortazzi 1987, 301–310), they were part of a larger strategy for making Japan ‘presentable’ and facilitate the revision of unequal treaties, in a context were markers of ‘civilization’ in Japan were being re-discussed (Howell Citation2005).

It should not surprise that the Guide-Book would refrain from reporting about customs forbidden in the ordinances, as the Kihinkai had received active support from members of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, including Inoue Kaoru (1836–1915), who had promoted them (and, more generally, had embraced the idea of ‘Westernization’ as a response to the issue of the unequal treaties). Shirahata (Citation1996, 28) even argues that the Society might have been conceived as part of a wider ‘national policy’ aimed at their revision.

By the time the Guide-Book was published, the unequal treaties had already been revised, but Japan was entering a new, delicate phase on the international diplomatic stage. In 1905, the country hadn’t been able to obtain a war indemnity from Russia, like the one it had received after the war with China in 1895. The way Russia was supported on this issue by other foreign powers, and particularly by the United States, was an harsh reminder of the conflicting interests at play in Asia and of the fact that Japan’s road to international recognition was far from complete. The Russo-Japanese war, on the other hand, had been a public event discussed around the globe, giving Japan a completely new visibility, in the form of newspaper articles, prints, postcards, and histories of the war (Jacob Citation2018). It may very well be presumed that members of the Kihinkai felt that they could build on this new flood of works on Japan with their own English-language publications, working towards a two-fold aim: attracting currency after a costly war, through tourism, and fostering Japan’s foreign policy agenda.

This was done by presenting Japan as an equal to ‘Western’ powers. Murray’s Handbook, in its own way, had already put the nation in a ‘presentable’ light, but the Guide-Book seems to have been striving to adjust its narrative to specifically emphasize the cultural closeness between Japan and the ‘West’. This was not the only possible ‘nation-branding’ strategy at hand, but it seems to be the one the members of the Kihinkai specifically chose, in light of their backgrounds and connections. The Guide-Book also openly supported Japan’s colonial endeavour. It’s worth noting, in this last regard, that the Guide-book was published at around the same time when English editions of a developing Japanese colonial ethnography of Korea were being distributed to overseas research libraries, as an attempt to legitimize Japan’s seizure of Korea to the eyes of the world (Atkins Citation2010, 65).

In this sense, it would be reductive to read the Kihinkai’s publications as a simple tool meant to assist foreign tourists in their visit to Japan. Styled to ‘affect others to obtain the outcomes one wants through attraction rather than coercion or payment’ (Nye Citation2008, 94), they can be read as tools meant to employ soft power, with the intended outcome of international recognition.

It's difficult to evaluate how impactful the Guide-Book was on its intended readership. It’s interesting to note that the sense of nostalgia for a lost past was toned down in editions of the Handbook published after the Guide-Book, veering toward a less paternalistic representation of Japan’s achievements and a less alarmed outlook on the effects of Westernisation.

In every sphere of activity, the old order gave way to the new. The most drastic changes took place between 1871 and 1887. The war with China in 1894-1895 again marked an epoch. Not only did its successful issue give an extraordinary impetus to trade and industry, but the prestige then acquired brought Japan into the comity of nations as a power to be counted with. Another point has become clear of late years – Europeanisation, after all, is not to carry everything before it. Along many lines the people retain their own dress. Japan, though transformed, still rests on her ancient foundations. (Chamberlain and Mason Citation1907, 1–2)

However, this probably more generally reflected the evolving nature of the Anglo-Japanese alliance after the Russo-Japanese war, rather than a direct influence of the Guide-Book itself. Nonetheless, the intent and narrative strategy behind the Guide-Book mark it as a tool deployed in the context of an early and complex attempt at public diplomacy.

Conclusions

Shirahata (Citation1996, 30) suggests that the Kihinkai might have been conceived as a sort of Office for Ceremonial Relations, at a time when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs still didn’t have one. Sure enough, at a time when most ‘Western’ visitors were members of the European and North American upper classes, the founders of the Kihinkai were conscious of the diplomatic implications of their activities. The very name ‘Kihinkai’ was, after all, a reference to a poem in the Shijing (Classic of Poetry) collection that related about hospitality as diplomacy in ancient Chinese society (Shirahata Citation1985a, 83), and the Society described itself as an institution that aimed not only at promoting international trade, but at promoting and facilitating ‘between Japan and foreign peoples such intimate intercourse as will tend to dispel racial prejudice and to break down the barriers between East and West’ (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 2).

In this, the Kihinkai was a pioneering institution. In the 1890s, when it was created, regional tourist societies did exist in Europe, but no country had yet started to actively publicize tourism at a national level, with public tourist organizations. The Kihinkai turned tourism, a private, non governmental field of international relations, into a public matter, directing it towards benefiting the nation’s economic growth and international position. It paved the way to the creation in 1912 of the Japan Tourist Bureau (JTB), one of the earliest National Tourist Offices in the world (which, by 1914, would absorb all of its activities), and laid the ground for the growing public employment of leisure and tourism in the pre-war period (as described by Leheny [Citation2003]).

The Kihinkai’s Guide-Books were a central component of these strategies. Their careful narrative encompassed a clear consciousness of the geopolitical and diplomatic implications of tourism and hospitality. As openly stated in their preface, they were meant to guide tourists in ‘accurately observing the features of the country and the characteristics of the people’ (The Welcome Society Citation1906, 2). They anticipated the role played by later officially licensed tourist guidebooks, such as those by the Japan Department of Railways (Citation1913), in both promoting the nation abroad and consolidating a communal, ‘national’ sense of identity (Akai Citation2009). They embraced and re-adapted the cultural canon that informed Murray’s Handbook. They relied on its authoritativeness, its rational presentation of Japan as a unified nation-state, its creation of a tourist map based on ‘modern’ railway-based itineraries and its focus on Japan’s attractiveness as a destination. At the same time, they subtly transformed its contents, so as to ‘advertise’ the nation in a way that would better respond to the diplomatic necessities at hand.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Erica Baffelli for her valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of this article, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sonia Favi

Sonia Favi is a tenure track researcher at the Department of Humanities of the University of Turin. Her current research focuses on travel related sources and travel encounters within Japan and between Japan and Europe. She recently completed a Marie Skłodowska-Curie project on these themes at the University of Manchester. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 The Kihinkai did translate some of its guidebooks in French, but English was dominant, also in light of the fact that, as Leheny (Citation2003, 55) reports, a good percentage of ‘Western’ visitors to Japan at the time travelled from Britain and the US. British settlers had also been pioneers in the study of Japan (Koyama Citation2011): both Satow and Chamberlain, authors of different editions of Murray’s handbook, were affiliated with the Asiatic Society of Japan (founded in Yokohama in 1872), a leading authority in Japanese Studies.

2 They appeared in 1894, 1899, 1901, 1903, 1907 and 1913.

3 Later published independently by Maruya: Tomita 1893.

4 The protests were both on creative and economic grounds. See Akai (Citation2009, 158).

5 I will focus in the article mainly on this seventh edition of the Handbook, as it was the one directly referenced by the Kihinkai in its longer guidebooks, published since 1905.

6 See Buzard (Citation1993, 1–2) on the common opposition between ‘tourist’ and ‘traveller’.

7 Globetrotters’ travel reports and the way they convey this ambivalence are discussed in depth in Best (Citation2021, 45–46).

8 For an in-depth analysis of the background and activities of the members of the Society, see: Shirahata (Citation1985a, Citation1985b, Citation1996); Shiga (Citation2000); Nakamura (Citation2006); Furuya, Nose, and Ōta (Citation2009); and Satō (Citation2019).

9 First as Welcome Folio Containing Map of Japan, in 1899 and 1901, and then as The Latest Map of Japan, for Travellers, in 1901, 1905, 1906, 1908, 1909, 1911, 1912, and 1913. All the pamphlets were in English, except for the fourth and eight editions, which were bilingual (French and English). A French version, titled Nouvelle carte du Japon à l'usage des voyageurs. 5.éd., was also published in 1905.

10 With one edition in 1906, two different editions in 1907, and then again one in 1909 and 1910. A French edition was also published in 1907 as Notes utiles et itinéraires pour voyager au Japon.

References

- Akai, Shōji. 2009. “Ryokō gaidobukku no naka no ‘miru ni atai suru Mono. Kōnin Tōa annai’ Nihon hen to ‘Terry no Nihon Teikoku Annai’ no 1914 nen.” Ritsumeikan sangyō shakairon shū 45 (1): 151–170. http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/file.jsp?id=245217.

- Alù, Giorgia, and Sarah Patricia Hill. 2018. “The Travelling Eye: Reading the Visual in Travel Narratives.” Studies in Travel Writing 22 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/13645145.2018.1470073.

- Atkins, E. Taylor. 2010. Primitive Selves. Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Best, Anthony. 2021. British Engagement with Japan, 1854-1922: The Origins and Course of an Unlikely Alliance. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bird, Isabella, and Kiyonori Kanasaka, eds. 2018. Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: Revisiting Isabella Bird. Folkestone: Renaissance Books Ltd.

- Butler, Rebecca. 2018. “Can Any One Fancy Travellers without Murray's Universal Red Books’? Mariana Starke, John Murray and 1830s' Guidebook Culture.” The Yearbook of English Studies 48 (1): 148–170. doi: https://doi.org/10.5699/yearenglstud.48.2018.0148. doi:10.1353/yes.2018.0007.

- Buzard, James. 1993. The Beaten Track. European Tourism, Literature, and the Ways to Culture, 1800-1918. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buzard, James. 2002. “The Grand Tour and after (1660-1840).” In The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing, edited by Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs, 37–52. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall, and W. B. Mason. 1891. A Handbook for Travellers in Japan. London: John Murray.

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall, and W. B. Mason. 1903. A Handbook for Travellers in Japan. London: John Murray.

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall, and W. B. Mason. 1907. A Handbook for Travellers in Japan. London: John Murray.

- Cortazzi, Hugh. 1987. Victorians in Japan. In and around the Treaty Ports. London: The Athlone Press.

- Cortazzi, Hugh. 2000. Collected Writings of Sir Hugh Cortazzi. Surrey: The Japan Library.

- Daliot-Bul, Michal. 2009. “Japan Brand Strategy: The Taming of ‘Cool Japan' and the Challenges of Cultural Planning in a Postmodern Age.” Social Science Japan Journal 12 (2): 247–266. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyp037.

- Elliot, Andrew and Daniel Milne, eds. 2019. “War, Tourism, and Modern Japan,” Special Issue of Japan Review 33. Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- Fleming, Robin. 1995. “Picturesque History and the Medieval in Nineteenth-Century America.” The American Historical Review 100 (4): 1061–1094. doi:10.2307/2168201.

- Forsdick, Charles, Zoë Kinsley, and Kathryn Walchester. 2019. Keywords for Travel Writing Studies. A Critical Glossary. London: Anthem Press.

- Funck, Carolin, and Malcolm Cooper. 2013. Japanese Tourism: Spaces, Places and Structures. New York, Oxford: Berghahn.

- Funck, Carolin. 2018. “‘Cool Japan’ – A Hot Research Topic: Tourism Geography in Japan.” Tourism Geographies 20 (1): 187–189. doi:10.1080/14616688.2017.1402947.

- Furuya, Hideki, and Motoko Nose. 2009. “Gaikokujin no tame no kankō dokyumento. Kankō gaidobukku ni chakumoku shite.” IPSJ SIG Technical Report 71 (2): 1–8.

- Furuya, Hideki, Motoko Nose, and Katsutoshi Ōta. 2009. “Senzen ni okeru Nihon no kokusai kankō seisaku ni kansuru kisoteki bunseki.” Dai yonjūdai doboku keikaku kenkyū happyō kai (CD-ROM). http://library.jsce.or.jp/jsce/open/00039/200911_no40/pdf/5.pdf

- Fyfe, Paul. 2013. “Illustrating the Accident: Railways and the Catastrophic Picturesque in "the Illustrated London News.” Victorian Periodicals Review 46 (1): 61–91. doi:10.1353/vpr.2013.0005.

- Goree, Robert. 2017. “Meisho zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review 6 (2): 404–439. doi:10.1353/ach.2017.0023.

- Guth, Christine. 2004. Longfellow's Tattoos: Tourism, Collecting, and Japan. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Hall, Ian, and Frank Smith. 2013. “The Struggle for Soft Power in Asia: Public Diplomacy and Regional Competition.” Asian Security 9 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/14799855.2013.760926.

- Hill, Kate. 2017. Britain and the Narration of Travel in the Nineteenth Century. Texts, Images, Objects. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hirano, Katsuya. 2013. The Politics of Dialogic Imagination: Power and Popular Culture in Early Modern Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Howell, David L. 2005. “Civilization and Enlightenment: Markers of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan.” In The Teleology of the Modern Nation-State. Japan and China, edited by Joshua A. Fogel, 117–137. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hotta, Hajime. 1902. Up-to-date Guide for the Land of the Rising Sun. Tokyo: Maruya.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. 2015. “Pop-Culture Diplomacy in Japan: soft Power, Nation Branding and the Question of ‘International Cultural Exchange.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 21 (4): 419–432. doi:10.1080/10286632.2015.1042469.

- Jacob, Frank. 2018. The Russo-Japanese War and Its Shaping of the Twentieth Century. London and New York: Routledge.

- Japan Department of Railways. 1913. An Official Guide to Eastern Asia: Trans-Continental Connections between Europe and Asia. Tokyo: The Imperial Japanese Governmnent Railways.

- Jing, Sun. 2012. Japan and China as Charm Rivals. Soft Power in Regional Diplomacy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kawauchi, Yūko. 2020. “Hatsu no eibun Kyōto gaidobukku to Kyōto kokusaiteki kankō kōchika ni okeru Mimizuka.” Ritsumeikan Daigaku jinbunkagaku kenyūjo kiyō 122: 295–318. doi:10.34382/00012912.

- Keeling, W. E. L. 1880. Tourists' Guide to Yokohama, Tokio, Hakone, Fujiyama, Kamakura, Yokoska, Kanozan, Narita, Nikko, Kioto, Osaka, Etc., Etc.: Together with Useful Hints, Glossary, Money, Distances, Roads, Festivals, Etc., Etc. Yokohama: A. Farsari.

- Keeling, W. E. L. 1884. Tourists' Guide to Yokohama, Tokio, Hakone, Fujiyama, Kamakura, Yokoska, Kanozan, Narita, Nikko, Kioto, Osaka, Etc., Etc.: Together with Useful Hints, Glossary, Money, Distances, Roads, Festivals, Etc., Etc. Yokohama: A. Farsari.

- Keeling, W. E. L. 1887. Keeling’s Guide to Japan. Yokohama, Tokio, Hakone, Fujiyama, Kamakura, Yokoska, Kanozan, Narita, Nikko, Kioto, Osaka, Kobe, &c., &c. With Ten Maps. Yokohama: A. Farsari.

- Keeling, W. E. L. 1890. Keeling’s Guide to Japan. Yokohama, Tokio, Hakone, Fujiyama, Kamakura, Yokoska, Kanozan, Narita, Nikko, Kioto, Osaka, Kobe, &c., &c. With Ten Maps. Yokohama: A. Farsari.

- Kim, Hee Youn, and Ji-Hwan Yoon. 2013. “Examining National Tourism Brand Image: Content Analysis of Lonely Planet Korea.” Tourism Review of AIEST - International Association of Scientific Experts in Tourism 68 (2): 56–57. doi:10.1108/TR-10-2012-0016.

- Konno, Masafumi, Akira Soshiroda, and Fuyuka Hanyu. 2002. “Kankō Gaidobukku ni Miru Kankōchi No Apīru Pointo No Hensen.” The Tourism Quarterly - Journal of Japan Institute of Tourism Research 14 (1): 9–16. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jitr/14/1/14_KJ00009504686/_pdf.

- Koyama, Noboru. 2011. “Eikoku ni okeru Meiji jidai no Nihon kenkyū to shomotsu kōryū: Nihon bungaku no honkakutekina shōkai (hon’yaku) no sendankai to shite.” Kokusai Nihon bungaku kenkyū shūkai kaigiroku 34: 1–28. https://kokubunken.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_uri&item_id=2899&file_id=22&file_no=1

- Lee, Josephine. 2010. The Japan of Pure Invention: Gilbert and Sullivan’s the Mikado. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

- Leheny, David. 2003. The Rules of Play. National Identity and the Shaping of Japanese Leisure. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Lippit, Miya Elise Mizuta. 2019. Aesthetic Life. Beauty and Art in Modern Japan. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- McDonald, Kate. 2017. Placing Empire. Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- McDonald, Kate. 2019. “War, Firsthand, at a Distance: Battlefield Tourism and Conflicts of Memory in the Multiethnic Japanese Empire.” In "War, Tourism, and Modern Japan," Special Issue of Japan Review 33, edited by Andrew Elliot and Daniel Milne, 57–85. Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26652976

- Mitchell, Rosemary. 2000. Picturing the Past: English History in Text and Image, 1830-1870. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nakamura, Hiroshi. 2006. “Senzen ni okeru kokusai kankō (gaikyaku yūchi) seisaku – Kihinkai, Japan Tourist Bureau, Kokusai Kankōkyoku secchi.” Kōbe Gakuin Hōgaku 36 (2): 107–133. http://library.jsce.or.jp/jsce/open/00039/200911_no40/pdf/5.pdf.

- Nenzi, Laura. 2004. “Cultured Travellers and Consumer Tourists in Edo-Period Sagami.” Monumenta Nipponica 59 (3): 285–319. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25066305.

- Nenzi, Laura. 2008. Excursions in Identity: Travel and the Intersection of Place, Gender, and Status in Edo Japan. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

- Nishino, Yuki. 2011. “Miyako Kara Fuji ga mieta jidai. “Tōkaidō meisho zue” no mokuromi.” Nihon Bungaku 60 (2): 21–33. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/nihonbungaku/60/2/60_KJ00010169684/_pdf/-char/ja.

- Nye, Joseph S. 2008. “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (1): 94–109. 616 (Public Diplomacy in a Changing World): doi:10.1177/0002716207311699.

- Ousby, Ian. 1990. The Englishman's England. Taste, Travel and the Rise of Tourism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ray, Romita. 2013. Under the Banyan Tree: Relocating the Picturesque in British India. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ruoff, Kenneth J. 2014. Imperial Japan at Its Zenith. The Wartime Celebration of the Empire's 2,600th Anniversary. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Satō, Masaya. 2019. “Kihinkai setsuritsu ni okeru Hachisuka Mochiaki no sonzai to ryōko annai ni egakareta Shikoku.” In Heisei 30 nendo sōgō kagakubu sōsei kenkyū purojekuto keihi/chiiki sōsei sōgō kagaku suishin keihi hōkokusho ibunka ni terashidasareta Shikoku: gaikokujin narabini kokusaiteki ni katsuyaku shita Shikoku shusshinsha no nokoshita bunken no chōsa/kenkyū Kara, 57–69. Tokushima: Tokushima University Publications.

- Satoi, Shinichi, Fuyuka Hanyu, Akira Soshiroda, and Takashi Tsutsumi. 2003. “Meiji chūki ni kankō sareta gaikokujin muke eibun kankō gaidobukku no kijutsu naiyō no tokuchō.” Randosukēpu kenkyū 66 (5): 389–392. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jila/66/5/66_5_389/_pdf/-char/ja.

- Satow, Ernest Mason. 1996. Meiji Nihon Ryoko Annai. Translated and edited by Motoo Shoda. Tokyo: Heibonsha.

- Satow, Ernest Mason, and G. S. Hawes Albert. 1881. A Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan, Being a Guide to Tōkiō, Kiōto, Ōzaka, and Other Cities; the Most Interesting Parts of the Main Island between Kōbe and Awomori, with Ascents of the Principal Mountains and Descriptions of Temples, Historical Notes and Legends. Yokohama: Kelly & Co.

- Satow, Ernest Mason, and G. S. Hawes Albert. 1884. A Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan, Beign a Guide to Tōkiō, Kiōto, Ōzaka, Hakodate, Nagasaki, and Other Cities; the Most Interesting Parts of the Main Island; Ascents of the Principal Mountains; Descriptions of Temples; and Historical Notes and Legends. London: John Murray.

- Seton-Karr, Heywood Walter. 1888. Handy Guide Book to the Japanese Islands: With Maps and Plans. Yokohama: Kelly & Walsh.

- Shiga, Zen'ichirō. 2000. “Kihinkai no setsuritsu menbā ni kan suru ichi kōsatsu.” Magis 5: 123–134.

- Shirahata, Yōzaburō. 1985a. “Ryokō no sangyōka. Kihinkai Kara Japan Tourist Bureau e.” Gijutsu to bunmei 2 (1): 79–96. http://www.jshit.org/kaishi_bn1/02_1sharahata.pdf.

- Shirahata, Yōzaburō. 1985b. “Ijin to gaikyaku. Gaikyaku yūchi dantai ‘Kihinkai’ no katsudō ni tsuite.” In Jūkyū seiki no Nihon no jōhō to shakai hendō, edited by Yoshida Mitsukuni, 113–137. Kyoto: Kyotō Daigaku jinbun kagaku kenkyūsho.

- Shirahata, Yōzaburō. 1996. Ryokō no susume. Shōwa ga unda shomin no "shinbunka". Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha.

- Sinha, Amita. 2020. Cultural Landscapes of India: Imagined, Enacted, and Reclaimed. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Sterry, Lorraine. 2009. Victorian Women Travellers in Meiji Japan. Discovering a ‘New’ Land. Folkestone: Global Oriental.

- The Welcome Society. 1906. A Guide-Book for Tourists in Japan. Tokyo: The Society.

- Tomita, Gentarō. 1887. Tourist’s Handbook: containing a Guide to Yokohama, Tokyo, Daibutsu, Kamakura, Enoshima, Etc. Together with a List of Useful Japanese Words and Phrases. Yokohama: Tamamura.

- Traganou, Jilly. 2004. The Tōkaidō Road. Traveling and Representation in Edo and Meiji Japan. London: Routledge.

- Utpal, Vyas. 2010. Soft Power in Japan-China Relations. State, Sub-State and Non-State Relations. London and New York: Routledge.

- Vitale, Judith. 2021. “The Destruction and Rediscovery of Edo Castle: ‘Picturesque Ruins’, ‘War Ruins.” Japan Forum 33 (1): 103–130. doi:10.1080/09555803.2019.1646786.

- Watanabe, Genjirō. 1898. Guide Book for Tourists in Japan. Yokohama: Watanabe Genjirō.

- Wisenthal, Jonathan. 2006. A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, and Contexts of Madame Butterfly. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Yokoyama, Toshio. 1987. Japan in the Victorian Mind. A Study of Stereotyped Images of a Nation (1850-80). Houndmills: The MacMillan Press LTD.