Abstract

This article approaches the field of global health governance from the vantage point of shared discourses and norms on the good governance of governance amongst multiple international organisations (IOs). Conceptually, we introduce metagovernance norms as constitutive, reflexive beliefs concerned with institutional order and IO interactions in a given governance field. We argue that such norms are entangled with causal beliefs and problem perceptions that form part of contingent, contested repertoires of knowledge. Moreover, we illustrate how IO ‘expert’ groups form an authoritative subject position from which truth claims about governance are advanced. Empirically, we trace metagovernance norms in discourse(s) amongst eight health IOs since the 1970s. We show how metagovernance norms have been constructed around competing beliefs about governance ‘effectiveness’ and problem perceptions concerned with different forms of ‘complexity’. Our research demonstrates that discourses on institutional order in global health are shaped by metagovernance norms drawing on historically-specific knowledge repertoires.

Introduction

Contemporary research on international organisations (IOs) is increasingly moving away from the study of individual IOs’ institutional design and the constellations of power and interests that influence the politics inside IOs. Today, the embeddedness of IOs in larger fields or regime complexes (Alter and Meunier Citation2009), as well as their entanglement in networks of relations with other organisations and multiple systems of rules (Drezner Citation2009) take centre stage. Following this trend but deviating from its rationalist-institutionalist core, in this paper we approach contemporary global governance from the vantage point of shared discourses and norms on the good governance of governance (Jessop Citation2014) across multiple IOs operating in the same policy field – in our case the field of global health. Our paper makes two core contributions. First, we develop the concept of metagovernance norms as a category of constitutive normative beliefs that are concerned with good institutional order and desirable interactions in a given governance field. Drawing on critical IR norms research (Björkdahl Citation2002; Krook and True Citation2012; Wiener and Puetter Citation2009; Wiener Citation2018) and theorising on second-order, reflexive governance (Jessop Citation2014), we conceptualise metagovernance norms as relationally embedded in historically contingent discursive repertoires of knowledge on governance. Furthermore, we propose two analytical directions for disentangling such repertoires empirically: on the one hand, we argue for a focus on how the discursive constitution of governance problems and causal beliefs about governance is drawn upon, lending certainty to norm enactments and underpinning historical shifts in metagovernance norms. On the other hand, we point to IO expert groups as an authoritative subject position from which truth claims about governance can be advanced and hence as a promising lens for empirical inquiries into changing normative imaginaries of good governance of governance. By pointing to the ways in which these norms are intertwined with governance problems and causal beliefs about governance, we link them to the transformation of institutional orders.

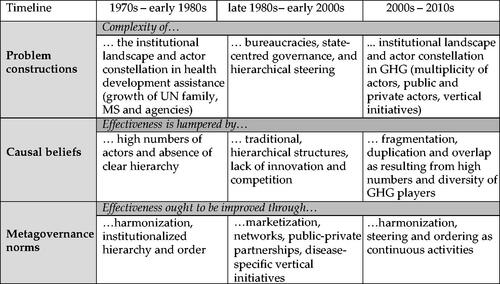

Second, to illustrate the empirical applicability of our analytical proposals, we historically trace metagovernance norms in IO discourses on global health governance (GHG) from 1970 to 2013. The analysis shows how metagovernance norms in global health have been constructed around competing beliefs about governance ‘effectiveness’ and historically changing problem perceptions that revolve around different forms of detrimental complexity. Our material points to a twofold historical transformation in IO discourse on good global health governance: from normative concerns with representation and causal beliefs in a need for hierarchy in the late 1970s and early 1980s, via beliefs in the causal and normative superiority of networks and market-principles in the 1990s and early 2000s, to a renewed discourse on harmony and steering since the mid-2000s. Through an in-depth analysis of selected expert group consultations at three points in time (1975-77, 1998-2001, 2005), we inquire into how repertoires of knowledge and connected expert subject positions were drawn upon to establish productive truth claims about the desirable and necessary (re)organisation of the global health field. Hence, we show how metagovernance norms in global health are intertwined with historically contingent, yet powerful discursive claims about the problems that governance needs to address and the causalities it is assumed to obey.

In this paper, we first situate our argument in recent literature on international organisations and their embeddedness in issue-specific governance fields composed of multiple IOs with often intersecting mandates and with numerous inter-organisational ties. In a second step, we put forward an alternative approach to the study of inter-organisational relations in governance fields, building on and extending critical International Relations (IR) norms research by introducing the notion of metagovernance norms as a specific reflexive and constitutive type of norm. We conclude the conceptual part of the paper by proposing a distinct analytical strategy for analysing the (changing) meaning of metagovernance norms, which builds on the interplay between metagovernance norms, causal beliefs and problem constructions in international politics. In the second part of the paper, we show the usefulness of our conceptual and analytical propositions by discussing insights from our study of contested metagovernance norms and changing repertoires of knowledge in global health governance.

The discursive intertwinement of metagovernance norms, governance problems and contested causal beliefs

The theoretical propositions we put forward in this paper are located at the intersection of two prominent debates in contemporary IR scholarship: first, newer theorising on international organisations that sees them as being part of larger issue-specific institutional complexes or governance architectures and secondly, critical-constructivist theories on norms in international politics. Contemporary thinking on IOs reflects a shift away from the isolated study of international organisations with regard to the agency and autonomy of their bureaucracies vis-à-vis member states (i.e. research on international bureaucracies, principal-agent theory etc.; Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Bauer and Ege Citation2016; Busch and Liese Citation2017; Hawkins et al Citation2006; Reinalda and Verbeek Citation1998; Vaubel Citation2006) or their role and authority in specific fields of global governance (Abbott et al Citation2015). In today’s study of international organisations, their embeddedness in larger organisational fields – in many cases populated by multiple international organisations, public-private institutions and a plethora of private actors and networks – occupies centre stage. A growing body of literature on increasing institutional fragmentation and regime complexity in International Relations scholarship puts forward a portrayal of contemporary global governance in almost any field of international concern as being characterised by an ongoing multiplication of rules, actors, organisations and networks. While IOs, as institutions set up and authorised by states, thus, are still mostly treated as focal institutions for state actors (Abbott et al Citation2015), they are at the same time conceptualised as ‘open-systems’ (Hanrieder Citation2014; Koch Citation2015) and entangled in a dense web of rules and interactions. Understanding and explaining how IOs and their member states navigate these entanglements by managing their inter-organisational relationships is a central part of the research agendas on regime complexity and fragmentation. Existing explanations of IO-IO relations’ drivers focus on IOs’ interests in gaining new or additional material (funding) or immaterial resources (knowledge, legitimacy, network access; Biermann Citation2008; Koops Citation2013). It is, thus, the functional necessities of IOs that explain the dyadic, triadic or network-like cooperative structures of IOs that define field-specific governance architectures.

Deviating from a rationalist-functionalist tendency in the literature, in this paper we approach contemporary global governance from the vantage-point of shared discourses and norms on the good governance of governance (Jessop Citation2014) across multiple IOs operating in the same policy field – in our case the field of global health. We argue that IOs shape institutional complexes inasmuch as they shape specific norms on good global governance and the logic of appropriateness that define how international problems should be governed and by whom. We call these norms metagovernance norms. In studying the norms that underlie inter-organisational relations in global health and shape the institutional set-up of this field, we follow scholars such as Dingwerth and Pattberg who privilege norms in their approach to the emergence of organisational ‘communities’ and fields in transnational politics (Dingwerth and Pattberg Citation2009; Vetterlein and Moschella Citation2014).

Anti-essentialist norms research and imaginaries of ‘good’ ‘governance of governance’

Our proposition to study institutional order in the field of global health by studying metagovernance norms builds on recent trends in IR research on norms and, at the same time, constitutes an extension of these theories. In recent decades, critical currents of IR norms research have sought to move beyond via media constructivist conceptualisations of norms as relatively stable standards of appropriate behaviour (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998; Katzenstein Citation1996) towards anti-essentialist, context-sensitive understandings of norms as contingent, contested and interrelated (Björkdahl Citation2002; Engelkamp, Glaab and Renner Citation2012; Krook and True Citation2012; Renner Citation2013; Wiener and Puetter Citation2009; Zehfuß Citation2002). This development has gone along with a shift in research focus, away from questions of norm diffusion, socialisation and compliance to an emphasis on norm dynamism, enactment, meaning-struggle and translation of norms across social contexts (Acharya Citation2004; Almagro Citation2018; Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Citation2013; Lantis and Wunderlich Citation2018; Wiener Citation2009; Zwingel Citation2012). Building on this interest in the context-specificity and instability of meaning, we understand norms from a relational, discursive perspective as historically contingent beliefs that are (re)produced through enactment in discursive practices and endowed with meaning through their relations with other discursive entities.

Arguably, much of the literature on norm contestation has revolved around struggles over substantive norms, i.e. over social meanings pertaining to specific areas of international cooperation such as humanitarian intervention, the environment, climate governance, human rights etc. In this paper, we suggest extending this line of anti-essentialist thinking on international norms by developing and exploring the concept of metagovernance norms that relate to perceptions of how one can and ought to govern; in that sense, they are reflexive norms. Metagovernance norms are also constitutive norms for institutional order as they define what should be governed and who should be in charge and procedural norms inasmuch as they relate to how international problems should be governed. In our perspective, metagovernance norms are constitutive as they give meaning to and shape the identity and relations of international organisations in specific fields of global governance. At the same time, we understand metagovernance norms as inherently contested and subject to meaning-struggles among IOs. In her seminal contributions to critical-constructivist theorising on international norms, Antje Wiener differentiates between three types of norms: ‘core constitutional […] fundamental norms’, ‘practice-based […] organising principles’, as well as ‘standardised procedures [and] regulations’ in defining the core institutions shaping international politics (Wiener Citation2008, 66, see also 2018, 62). Put in this vocabulary, metagovernance norms correspond most directly with Wiener’s ‘organising principles’ as they ‘evolve from the practice of politics and policy making’ (Wiener Citation2008, 67). However, the concept of metagovernance norms goes beyond Wiener's typology. It is more open and discourse-analytical: we do not, for instance, see metagovernance norms as ontologically distinct from ‘standardised procedures’, a ‘norm type’ which according to Wiener ‘is not contingent and entails directions that are specified as clearly as possible’ (2008, 67, emphasis added). More importantly, it extends on current critical-constructivist theorising by putting an explicit analytical focus on reflexive norms that relate to how governance should be organised. This challenges the notion that to unearth the contingent, contested and normative aspects of international politics one needs to look to substantive norms such as democracy, rule of law or human rights. Rather, we contend that normativity and contestation are inextricably bound up in knowledge production on governance.

To accomplish this analytical extension, we draw on literature theorising on metagovernance. In contemporary scholarship, usages of the term metagovernance and related terms such as coordination (Peters and Pierre Citation2004) or collibration (Dunsire Citation1993) oscillate between two different deployments. On the one hand, the term has been used by scholars interested in self-governing systems, cybernetics and networks as referring to a historically specific (post)modern self-regulating logic for governing society (for example Braun Citation1993; Mayntz et al Citation2005; Mayntz and Scharpf Citation1995; Peters Citation1998). On the other hand, scholars working in the tradition of critical state theory have conceptualised metagovernance as a more open analytical category referring to second-order reflexive practices directed towards ordering governance itself (Jessop Citation2014, 107; Kooiman Citation2003; Kooiman and Jentoft Citation2009, 822-823; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2007). We use metagovernance in the latter sense as referring to a reflexive, self-directed quality of governance. Thus understood, the notion allows us to delineate a specific kind of constitutive norm that is concerned with how the governance of governance (Jessop Citation2014) in a given social context ought to be organised – i.e., beliefs concerned with good institutional order and desirable interactions in a given field.

Analytical strategies: problem constructions, causal beliefs and the ‘expert’ subject position

To grasp how metagovernance norms receive their specific meaning(s) and become perceived as something desirable and necessary, we suggest inquiring into how they are situated in broader repertoires of knowledge on governance. This points us in the direction of anti-essentialist currents of discourse analysis as the latter take an interest in how overarching knowledge formations delineate the borders of what is reasonably speakable and thinkable in a given historical, socio-political context (Foucault Citation1977; [1972] 2010; Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985). We hence adopt an anti-essentialist understanding of the term discourse as referring to a historically specific formation of taken-for-granted knowledge claims and assume that such regularities unfold productive effects as they form an underlying basis for how social beings act in the world. Since such naturalised knowledge claims do not ‘fall from the sky’ but are constantly (re)produced, they are also open to contestation and historical change. In underlining struggle and historical change in the meaning of norms, we furthermore tie in with the literature on feedback loops and contestation in norm evolution. Here, pertinent contributions have questioned the teleological tendency in earlier theoretical accounts of norm evolution, such as the spiral model (Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink Citation1999) or the norm life cycle (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998), by emphasising norm conflicts, the indeterminacy of meaning and how norms are always open to (renewed) meaning struggles (for instance, Van Kersbergen and Verbeek Citation2007; Sandholtz Citation2008; Krook and True Citation2012, for a discussion, see Niemann and Schillinger Citation2017). However, in contrast to said literature, our discourse-analytical approach puts an explicit analytical focus on how the evolution of (metagovernance) norms is informed by contingent, contested repertoires of knowledge.

To analyse norms from this perspective first of all entails locating their meaning in relation to other terms/objects and tracing how such relations transform through contestation and historical shifts (Niemann and Schillinger Citation2017). A promising analytical direction for such inquiries is to focus on how metagovernance norms are underpinned and contested through changing i) causal beliefs about how governance functions and changing ii) discursively constituted problem constructions. Whilst IR norms research has long acknowledged that norm emergence and institutionalisation depend on how new norms relate to existing ones (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998), in recent years scholars have turned increasing attention to how norms are embedded in, draw certainty from, and are reproduced through their discursive surroundings and practical enactments (Almagro Citation2018; Renner Citation2013; Wiener Citation2009; Winston Citation2017). We extend on this line of thinking by arguing that metagovernance norms gain epistemic force, not only through connections to other norms but much more through connections to problem constructions i.e., governance problems and causal beliefs about governance. Causal beliefs are relevant here since propositions about how to govern properly must be articulated according to accepted beliefs about what causal (im)possibilities govern the field of intervention in order to be perceived as authoritative and understandable. Moreover, such claims need to be articulated against the backdrop of a discursively established, accepted problem that poses itself to governance. In this sense, metagovernance norms are located at the border between the desirable, the necessary and the possible as understood in a given socio-historical context.

To trace how metagovernance norms, causal beliefs and problem construction intertwine empirically in discourses amongst IOs, we suggest paying analytical attention to experts and expert groups as a source of powerful truth claims. For a considerable time, the nexus between knowledge and politics has been captured under the rubric of ‘epistemic communities’ understood as ‘networks of knowledge-based experts’ to whom states ‘turn in the face of uncertainty’ (Adler and Haas Citation1992; Sebenius Citation1992). These expert communities were treated as being held together by shared truth claims – some of which were becoming powerful in shaping international policies. While the epistemic community literature continues to define the parameters of engagement with expert knowledge in IR, it has been repeatedly criticised for paying little attention to the construction and contestation of specialised knowledge (Adler and Bernstein Citation2005; Adler and Haas Citation1992). Over time, thus, the idea of homogenous groups of experts advocating for uncontested scientific facts was challenged by a number of seminal studies that brought to light conflicts between different expert communities over facts, problem definitions and policy solutions (Epstein Citation2008; Litfin Citation1994). In a recent contribution, Hannes Hansen-Magnusson, Antje Vetterlein, and Antje Wiener address how knowledge construction shapes norms by arguing that a diversity of practical knowledges held by actors increases the likelihood of norm contestation in policy-making (Hansen-Magnusson, Antje and Wiener et al Citation2018). We concur with their assessment that there is a ‘need to account for the social foundation of norms’ and hence for the intertwinement of meaning struggles and knowledge production (Hansen-Magnusson, Antje and Wiener Citation2018, np). However, whilst these authors put forth the normative-critical argument that ‘sustainable normativity emerges as a result of interactive knowledge production and transfer in the process of policy norm contestation’ hence ‘rais[ing] the legitimacy of governance processes’ (Hansen-Magnusson, Antje and Wiener Citation2018, np), we argue from an anti-essentialist critical standpoint. Accordingly, we develop and apply analytical tools for uncovering the historical specificity and naturalisation of knowledges that underpin changing metagovernance norms (rather than for identifying conditions for increased legitimacy and compliance).

Our analytical approach towards metagovernance norms also contrasts with the epistemic community literature inasmuch as we conceptualise expertise as a subject position in the discourse-analytical sense: a discursive location from which it is possible to reproduce a given discourse in an authoritative manner, or in other words a social identity that allows its speaker to advance truth claims about a given realm of social reality (compare with Foucault [1972] 2010, 52-53). Rather than seeing experts as agents in possession of objective, factual knowledge, we therefore understand expertise as historically specific, productive bodies of truth claims. They cannot be thought of as external to political struggles. Our perspective is therefore close to Bourdieu’s notion of expertise, which is typically thought of as ‘a work performed by individuals seeking to impose the certification of their knowledge or their skills and delineate a field over which they become entitled to make authority claims’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 243, in IR, see inter alia Guilhot Citation2005; Sending Citation2015). Experts hence construct their body of truth claims and make bids for recognition and authority (Sending Citation2015). We align with Bourdieusian approaches in pointing out that what is perceived as relevant and true results from historical processes of imposition and exclusion, positioning specific repertoires of knowledge as natural, given and authoritative. However, rather than inquiring into the processes of field-specific capital accumulation (see for example Sending Citation2015), we take an interest in the discursive conditions that make it possible to reproduce and shape dominant perceptions about how a given realm of governance should be governed. If, as Foucault remarks, ‘in clinical discourse, […] the doctor is the sovereign’ (Foucault [1972] 2010, 53), we ask who is positioned to speak in such a way about the proper governance of governance.

Taken together, our approach extends recent literature on IOs and their embeddedness in issue-specific governance fields by stressing how norms on the good governance of governance shape discourses on institutional order among multiple IOs. Furthermore, our approach advances critical IR norms research by developing the concept of ‘metagovernance norms’ and proposing analytical strategies for studying their intertwinement with historically distinct repertoires of knowledge.

The next section makes use of our theoretical proposals and seeks to illustrate their applicability for the study of governance fields composed of multiple IOs by discussing empirical insights from our research on shared discourses and metagovernance norms in global health governance.

Contested metagovernance norms and changing repertoires of knowledge in global health governance

International cooperation in the field of health is often highlighted as a prime example of a well-researched trend towards increasing proliferation and complexity of rule systems and a somewhat unlimited pluralisation of actors and institutions. Scholarly engagement with this issue area thus often focuses on the risks associated with excessive fragmentation and ‘ungovernable’ complexity, emphasising power struggles fuelled by incompatible rationalities and conflicting interests of diverse actors occupying the field (Inoue and Drori Citation2006; Sidibé et al Citation2010). During the post-Cold War period, the field of global health underwent a phase of intense institutional experimentation, with the creation of a broad array of issue-specific organisations such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis and a host of public private partnerships. Yet in more recent years, there was a marked shift towards integration, reflected in a wide range of new initiatives, mechanisms and institutions geared towards inter-organisational alignment and harmonisation. As we have shown elsewhere, over time, the interactions among organisations display patterned inter-organisational practices and homogenous discourses rather than uncontrolled, institutional proliferation and inter-actional competition (Holzscheiter Citation2015; Holzscheiter et al Citation2016). We build on these observations in order to inquire into the effects of metagovernance (norm) discourses on the emergence and transformation of the institutional architecture constituting global health governance.

Corpus construction and methodological strategies

In the remainder of this article, we shed light on historically changing discourses on the good governance of governance in global health. Our analysis historically reconstructs changing perceptions in IO discourses from the early 1970s until the recent past. The core text corpus consists of all annual reports issued by eight powerful health IOs in the years 1970 to 2013: GAVI the Vaccine Alliance (GAVI), the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the World Bank, and the World Health Organisation (WHO). As annual representations of IOs’ activities, relationships, presumably important events and noteworthy achievements, these reports articulate normative perceptions of 'good' GHG and provide traceability of developments over time. In addition, we extended the corpus by collecting documents that the annual reports themselves referred to, including fact sheets, expert reports, and General Assembly resolutions (intertextuality).

The analysis focused on patterns of equation, juxtaposition, dichotomisation, groupings and sequences of occurrence between terms in text passages where normative vocabulary and articulations about desirable and necessary courses of governance intersect.Footnote1 Thereafter, we interpretatively identified problem constructions, causal stories and references to expert bodies. We analysed a selection of expert groups in more detail: The Group of Experts on the Structure of the United Nations System (1975) and the subsequent Ad Hoc Committee on the Restructuring of the Economic and Social Sectors of the United Nations System (1977), the WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (2000-2001) and its unofficial predecessor, the WHO Director-General's Transition Team (1998-1999) and finally the Global Task Team on Improving Coordination Among Multilateral Institutions and International Donors (2005). These groups were repeatedly referenced in the text corpus as sources of authoritative knowledge on governance. We also focused on moments in time at which the analysis revealed normative disagreement and/or shifts. Moreover, the selection allowed us to compare across time how the expert subject position was constituted and different knowledge repertoires were mobilised. In the following, we will first provide a broad overview of our findings by showing how vocabularies in global health governance change over time and then delve in more deeply through a diachronic tracing of changing and intertwined metagovernance norms, repertoires of knowledge, and problem constructions.

Changing vocabularies in GHG and the ostensible historical constants of ‘effectiveness’ and ‘complexity’

The vocabulary in which IOs described their activities, interactions with other entities and the shape of the field was characterised by a relative dominance of technical language in the 1970s and early 1980s, as compared to other years. There was a frequent use of vocabulary stemming from medicine and epidemiology, but also realms such as engineering and industrial development (see for example WHO Citation1971; Citation1972; Citation1973). Whilst this language did not disappear over time, its relative prominence in the corpus declined as further vocabularies appeared more frequently. Notably, in the 1990s and early 2000s, economised concepts such as competition, pluralisation, (policy) innovation and (public-private) partnerships proliferated (see for example World Bank Citation1994). From the early 2000s onwards, reflexive terms concerned with order and steering, such as ‘harmonisation’, ‘coherence’ or ‘alignment’ appeared with increasing normative force (see for example Global Fund Citation2005; UNAIDS Citation2004c; Citation2005c; UNDP Citation2007).

However, at first glance, the term ‘effectiveness’ seems to constitute something of a meta-value, untouched by time and place. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s effectiveness was consistently positively connoted, figuring in close proximity to other terms that suggest normativity and necessity. Although it occupied a less prominent position in the texts, the same apparent resistance to historical change applies to the term ‘complexity’. Sentences referring to the term often suggested a strong sense of necessity and juxtapose ‘complex’ problems, social situations and governance arrangements with governability. Whilst ‘complexity’ must be reduced, by reordering institutions or producing more knowledge about ‘complex’ phenomena that IOs seek to govern (for an early example, see UNDP Citation1971, 37), effectiveness was typically seen to imply a need for action or - in cases where a given activity or institution is deemed to be ‘effective’ - a continuation of and/or allocation of (further) resources to the latter (see, inter alia UNDP Citation1973, 70; 1979, 77; 1999, 43; WHO Citation1994, 17; 1999, xviii).

Notwithstanding, a more in-depth, relational reading shows that health IOs’ discourses contained conflicting notions of what ‘effectiveness’ consisted of, what ought to be effective and how such a state could be reached. The same applies to the term ‘complexity’. Descriptions of what was deemed ‘complex’ and how this could and ought to be addressed transformed over time (for illustrations, see Global Fund Citation2005, 14; UNDP Citation1979, 58; UNFPA Citation1995, 14; 2001, 28; WHO Citation1972, 12-13, 122; World Bank Citation1994, 14). In the remaining empirical sections of this article, we illustrate how the meanings of ‘effectiveness’ and ‘complexity’ are reconstituted and intertwined with overall transformations in the discursive imaginary of good GHG among IOs. In keeping with the discourse-analytical perspective outlined above, we therefore make the meaning of ‘effectiveness’, ‘complexity’ and other related terms an object of empirical research, tracing how shifts therein were underpinned by historically-specific knowledge repertoires and changing ‘expert’ subject positions. Following our interest in uncovering the historically specific, relational constitution of metagovernance norms, we discuss our results in a diachronic manner, starting with discourses on detrimental complexity, harmonisation and coherence in the context of UN economic and social reform in the 1970s.

Harmonisation, coherence and hierarchy: contested enactments in the 1970s

In the early 1970s, ‘complexity’ was typically used to describe the state of affairs in operational issue areas such as water and sanitation, supply of medicines, or related planning processes (WHO Citation1971, 6-7). Correspondingly, the solutions that were deduced from this problem construction were often technical, either articulated in the specialised language of medicine, engineering and industrial economics, or concerned with the division of labour and coordination of field activities within and amongst IOs (WHO Citation1973, 61-62, 97-98; Citation1974, xi). This called for specialised governance knowledge in response to narrowly delineated health or policy implementation problems. For instance, the effective planning of country programmes was seen to require input from programme management experts, whereas tackling ‘complex’ infectious diseases motivated the activity of disease-specific committees of epidemiological experts (for example WHO Citation1971, 9, 11; WHO Citation1972, 12-13, 122).

This understanding of complexity occurred throughout the text corpus. Yet, towards the mid-1970s, the term also began to figure in a reflexive manner, describing the interactions amongst organisational entities and the institutional architecture of health development assistance as lacking (WHO Citation1980, 24-25). Here, complexity figured next to terms such as ‘fragmentation’, ‘multiplicity’ and ‘duplication’ in narratives about the field’s dysfunctionality following the growth of the UN system and the resulting increase in the number of health actors (inter alia UNDP Citation1971, 44; Citation1976, 38; 1979, 58; WHO Citation1975, 68; Citation1980, 36). Furthermore, such constructions were connected to causal beliefs in ‘harmonisation’, ‘coherence’, and related terms such as ‘integration’ or ‘coordination’ required to alleviate complexity and increase effectiveness. For example, the 1978 UNDP report explains that ‘the system is complex and far-flung, involving more developing countries and territories (151), more Participating and Executing Agencies (26) and more field focal points of co-operation (108)’ and deduced that ‘a fully integrated approach to development is assuming increased importance (UNDP Citation1979, 58, see also 1975a, 16).

The ‘complicated’ shape and perceived limited governability of the field therefore emerged as a governance problem and were discursively connected to a normative imaginary of ‘harmonisation’ and ‘coherence’. These notions were in turn circumscribed through causal beliefs in the necessity for increased control and hierarchy amongst entities (UNDP Citation1975a, 45). For instance, a UNDP report posits that ‘divergent interests’ ought to be ‘harmonised to the greatest possible extent’ to achieve ‘effectiveness’ (UNDP Citation1975b, 68), whilst WHO’s annual report a few years earlier described harmonisation as a response to a ‘fragmentation of control’ (WHO Citation1972, 111). However, there were varying enactments of what these norms on governance meant in practical terms, i.e. how relations among IOs and other institutional actors ought to be (re)constructed. A number of text passages equated harmonisation with strengthening the coordinating function of inter-agency bodies such as the Inter-Agency Consultative Board (IACB). Others took note of calls by state representatives to enhance the coordination competencies of the General Assembly Development Group and recipient state control over the design of assistance programmes (UNDP Citation1975a, 10; Citation1977, 31, 44). Moreover, UNDP and WHO tended to highlight their own aptness for taking on a coordinating or leading role, hence suggesting that hierarchy amongst IOs might constitute a solution (UNDP Citation1976, 74-75; Citation1978, 6, 32, 74-75; WHO Citation1978, 7, 158, 168). Although ‘harmonisation’ and ‘coherence’ constituted positive, shared values, i.e. metagovernance norms, more specific enactments of their practical implications can be read as struggles concerning the appropriate hierarchy amongst IOs, as well as between UN specialised agencies and developing countries which by that time formed a majority in the General Assembly (United Nations General Assembly Citation1974, coordination competencies vested in UN specialised agencies, vs. in the General Assembly Development Group, compare with Golub 2013). The next section examines the role of expert groups in these struggles and the subsequent temporal fixing of practical meanings.

Struggle and discursive closure around harmonisation and coherence: the group of experts, the ad hoc committee and the subject position of the ‘statesman’

In the later years of the decade and the early 1980s, this discursive heterogeneity gave way to a more uniform understanding of what the presumed need for harmonisation and coherence implied. In particular, the 1977 General Assembly resolution on ‘Restructuring of the economic and social sectors of the United Nations System’ (UNGA Citation1977, henceforth: the 'Restructuring Resolution') figured as an authoritative statement on harmonisation and coherence. The Restructuring Resolution emphasised that coordination ‘should be governed by the policy guidelines, directives and priorities established by the General Assembly (and) the Economic and Social Council’ (UNGA Citation1977, 50), thus asserting the authority of said bodies. It refrained from connecting harmonisation to any need for more hierarchy amongst IOs and emphasised that inter-agency coordination should concentrate on preparing ‘concise and action-oriented recommendations’ for intergovernmental bodies (UNGA Citation1977, 52), whilst the interagency ‘machinery should be streamlined and reduced to a minimum’ (UNGA Citation1977, 54). Moreover, the resolution recommended that inter-agency coordination should be carried out through the Administrative Committee on Co-ordination (ACC) and that the latter should be merged with three other interagency bodies: the Environment Co-ordination Board, the Inter-Agency Consultative Board, and the Advisory Committee of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNGA Citation1977, 54). These changes in the institutional architecture came into effect with the successor organisation of the ACC, the UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB). A specific interpretation of harmonisation and coherence as implying a streamlining of inter-agency institutional entities and a renewed assertion of GA authority hence prevailed. By temporally ‘fixing’ the meaning of these metagovernance norms and implicitly drawing on causal beliefs in hierarchy and steering, it reordered the field’s institutional set-up. The Restructuring Resolution can therefore be understood as a point of discursive closure.

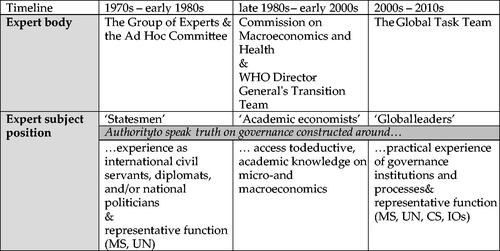

How did this specific interpretation of harmonisation and effectiveness establish itself as desirable and necessary? If one traces the emergence of the Restructuring Resolution, one encounters the work of two subsequent expert bodies. The resolution itself was based on the recommendation by the Ad Hoc Committee on the Restructuring of the Economic and Social Sectors of the United Nations System (henceforth 'Ad Hoc Committee', UNGA Citation1977). Yet, the creation of the Ad Hoc Committee by the GA was preceded by a Group of Experts on the Structure of the United Nations System (henceforth, ‘Group of Experts’, officially 'A New United Nations Structure for Global Economic Cooperation: Report of the Group of Experts on the Structure of the United Nations System', UNGA Citation1975). Their interpretation of ‘harmonisation’ and more effective inter-agency cooperation differed from the Ad Hoc Group’s in that it proposed an introduction of hierarchical institutional elements amongst IOs, strengthening coordination capacity at the multilateral rather than the recipient country level. Endorsements of the recommendations by the GA failed due to resistance by developing countries (Davidson and Renning Citation1982; Müller Citation2001). Instead, the Ad Hoc Group was created and formulated the recommendations that then formed the basis for the Restructuring Resolution (compare with Davidson and Renning Citation1982; UNGA Citation1975). Both the struggle amongst divergent enactments and the emergence of a dominant, productive interpretation in the Restructuring Resolution were hence intimately intertwined with truth claims advanced from the subject position of experts. The perceived need for the GA to create a further expert group - rather than advancing a diverging interpretation of harmonisation and effectiveness at its own accord – illustrates how expert groups are discursively positioned to endow specific enactments of metagovernance norms with a sense of naturalness and legitimacy. Whilst UN staff also participated in its deliberations, the Ad Hoc Committee consisted of member state representatives (Davidson and Renning Citation1982, 76). Similarly, the Group of Experts was composed of ‘high level experts’ from member states and UN agencies (Rochester Citation1993, 163). The authority to speak truth on the effective design of (inter-)agency-state coordination was hence constructed around members’ experience as international civil servants, diplomats and/or national politicians. Expert subject positions were also constructed as representative of ‘their people’, country, country group or organisation. The Ad Hoc Committee was therefore established as a ‘committee of the whole of the General Assembly’ with ‘all United Nations organs […] invited to participate’ (UNGA Citation1975, 2). A succinct term to describe this subject position might be the ‘statesman’: Someone who occupies this discursive position via speaking for his constituency and by virtue of his personal experience in the practical conduct of governance and diplomatic affairs.

Networks, markets and partnerships: the reconstitution of effectiveness in the late 1980s to 1990s

From the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, references to ‘harmonisation’ continued to occur. However, the reflexive implications that had been attached to the notion became increasingly rare. Instead, harmonisation was understood in a more technical sense: it mostly referred to institutionalised exchanges within the ACC framework between IO entities with the purpose of aligning activities in more closely delineable areas of operation (UNDP Citation1984, 3; 1985, 90, 124; UNFPA Citation1998, 31-32; WHO Citation1988, 19-20). Similarly, ‘complexity’ ceased to be applied to the same extent to the overall relations amongst IOs and other actors. Instead, in the late 1980s and early to mid-1990s, the term became increasingly associated with the (in-)effectiveness of the state, hierarchy, and bureaucracy (UNDP Citation1989b, 2, 26-27; UNFPA Citation1989, 17). In this new discursive pattern, ‘centralised’ governance was a central problem construction which was described as ‘traditional’, ‘old’ and ‘ineffective’. Governance arrangements based on the metagovernance norms of decentralisation, market-principles and the involvement of ‘private sector’ actors and/or civil society instead became associated with effectiveness (UNDP Citation1989a, 3; World Bank Citation1990, 48-49). This development came on the heels of the end of the Cold War (see, in particular World Bank Citation1992; Citation1993).

Throughout the course of the 1990s, the same discursive elements gradually appeared across reports and penetrated perceptions about how the health field should be organised. Instead of being connected to reduced fragmentation through harmonisation, effectiveness became associated with policy ‘innovation’ and ‘experimentation’, market-like organisation principles, competition, and inclusion of the private sector and civil society. There was a need to ‘[encourage] partnerships between governments, NGOs, and the private sector so as to maximise both coverage and quality of services and to stimulate innovative ideas’ (UNFPA Citation1995, 14; UNICEF Citation1996, 8, 34; World Bank Citation1994, 14; Citation1996, 61-63). In stark contrast to the discourse of the 1970s and early 1980s, the assumed inefficiencies of hierarchical bureaucracies and ‘state’ governance now emerged as a governance problem. Underpinned by causal beliefs in the superiority of markets and networks, the antidotes to this affliction included decentralisation, the inclusion of ‘private partners’ (e.g. civil society organisations, philanthropies, pharmaceutical industry), as well as the promotion of market- or network-like forms of interaction amongst health actors (WHO Citation1995, 63). With time, these notions had profound consequences for institutional order in global health as they translated into an unprecedented rise in public-private partnerships, disease-specific vertical initiatives, and ‘innovative’ funding mechanisms (well-known examples include Roll Back Malaria, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, Medicines for Malaria or UNITAID, the International Drug Purchase Facility, see Lidén Citation2013).

WHO’s discursive re-alignment: the transition team, the commission on macroeconomics and the subject position of the ‘academic economist’

The discursive reconstitution of effectiveness undoubtedly formed part of broader dislocations in political discourse in the 1990s that revolved around the notion of an ‘end of history’ victory of the liberal market economy over socialist planning and prepared the ground for the ensuing liberal-capitalist hegemony (Derrida Citation1994; Fukuyama Citation1992). Yet, how did these new problems, causal beliefs and associated normative perceptions permeate the discourses of global health and undergo field-specific adaptions? The development of WHO and the discursive patterns in its reporting in the late 1990s present an illuminating case in this regard. The period is often described as a time of ‘crisis’ for the organisation:

‘The WHO is in crisis. […] It is increasingly under fire for its lack of leadership and failure to modernise’. (Brown Citation1997; compare also with Brown et al. Citation2006)

This declining authority is typically attributed to WHO’s unwillingness to adjust to the ascending neoliberal discourse advanced by the World Bank and other IOs at the time. Yet, pertinent literature on the organisation’s history points to a discursive realignment with the rest of the field following Gro Harlem Brundtland’s election as WHO Director-General in 1998 (Brown et al. Citation2006; Lidén Citation2013; Williams and Rushton Citation2011).

A closer look at the changing discursive patterns in WHO reporting affirms this picture, pointing to a shift following Brundtland’s appointment. The 1998 annual report oscillated between the ‘old’ language of classical development assistance and the ‘Health for All Movement’ on the one hand, and the more recent causal beliefs in a need to move towards partnerships, policy innovations, networks and markets on the other. From 1999 on, this ambiguity gave way to causal claims about the virtues of innovation, privatisation and marketisation that characterised the overall coordinates of IO discourse at the time. The 1999 report stated that actors were ‘coming to realise the disadvantages of traditional development projects’ (WHO Citation1999, xvii). It spoke of the need for WHO to ‘be more innovative in creating influential partnerships’ (WHO Citation1999, xi) and to ‘harness the energies and resources of the private sector and civil society’ (WHO Citation1999, x), whilst avoiding ‘public intervention that has governments attempting to provide and finance everything for everybody (as it) fails to recognise the limits of government’ (WHO Citation1999, iv). These kinds of statements, moreover, became grounded in scientific truth claims that were explicitly drawn from macro- and microeconomics (WHO Citation1999, 7-10, 14-15, 18).

Tracing the emergence of this new imaginary back in time once more points us to the work of two expert groups: WHO Director-General's Transition Team (1998-9, henceforth, ‘Transition Team’), and its unofficial successor The WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health (2000-2001, henceforth ‘Commission on Macroeconomics’). The Transition Team was formed shortly after Brundtland took office in 1998. It produced an informal commissioned report entitled ‘Health, Health Policy and Economic Outcomes’ (WHO Citation1998, compare with Lidén Citation2013, 10), to which core passages outlining the macro- and microeconomic grounding of the normative claims presented in the 1999 annual report make explicit reference. Other sections in that annual report were directly authored by members of the Transition Team (WHO Citation1999, 12, 54). To a large degree, the same individuals later became members of the Commission on Macroeconomics that authored the widely noted 2001 report ‘Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development’ (WHO Citation2001). The Transition Team was composed of a handful of World Bank staff and academic consultants from two US-American universities’ economics departments. The Commission on Macroeconomics had a slightly more diverse composition including academic economists from a larger number of universities (including two European institutions) and multilateral institutions (OECD, WTO, Feachem Citation2002). Yet, non-economists were rare, as well as experts from non-Western or non-elite academic institutions. Compared to the Group of Experts and the Ad Hoc Committee, the Transition Team’s and the Commission on Macroeconomics’ ability to advance truth claims about the desirable and necessary (re)organisation of global health governance hence drew on a markedly different subject position. Their subject position as experts on GHG was underpinned by a perception that they had privileged access to and command of macro- and microeconomics, development and trade economics as academic disciplines. Richard Feachem, an influential figure in the global health field and formerly member of the Commission on Macroeconomics, demonstrated the privileging of economic repertoires of knowledge at the time:

‘The Commission consisted of eighteen commissioners, four of whom, including myself, came from the health sector and were relatively unimportant. […] The excitement and the power of the Commission derives instead from the other fourteen Commissioners — individuals who are prominent in economics, finance, development, trade, and political leadership. Their views on the essential links between health investment and economic growth cannot therefore be discarded lightly.’ (Feachem Citation2002, 87)

The re-emergence of reflexive harmonisation: harmful complexity and a new need for steering and ordering in the 2000s

Starting in the early 2000s and intensifying towards the end of the decade, a more reflexive usage of ‘harmonisation’ and related terms such as ‘coordination’ reappeared in our corpus as a desirable and necessary path for re-organisation of the health field. The more technical usage of the term as referring to everyday alignment of narrowly delineable areas of IO activity continued to dominate most of the annual reports during the first years of the decade (UNAIDS Citation2002, 23; UNFPA Citation2001, 28; UNICEF Citation2002, 42; World Bank Citation2001, 8). Yet at the same time, a reflexive understanding of the term as a necessary means for achieving overall effectiveness by increasing coherence and consistency amongst actors started occurring in the context of the AIDS/HIV response, vividly illustrated by the ‘Three Ones’ principles. The principles were developed during a series of international AIDS conferences at the beginning of the decade and became a central notion in AIDS/HIV programming discourse of following years (notably, the International AIDS Conferences in Barcelona 2002 and in Nairobi 2003, UNAIDS Citation2004a; Citation2004b; Citation2005c). The principles stipulated the need for ‘all partners’ to coordinate so as to ensure that the country response to the epidemic was organised around ‘one agreed HIV/AIDS Action Framework’, ‘one national AIDS Coordinating Authority’ and ‘one agreed country level Monitoring and Evaluation System’ (UNAIDS Citation2004c, 5). The multiplicity of partners and approaches and the absence of hierarchical steering bodies were thus reinterpreted as problem constructions contributing to an undesirable complexity detrimental to an effective AIDS response.

Throughout the following years, the harmonisation metagovernance norm also entered discourses on development aid effectiveness in a series of OECD declarations: the Rome Declaration on Harmonisation (OECD Citation2003), the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD Citation2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (OECD Citation2008), and finally the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (OECD Citation2012). Towards the second half of the decade, beliefs in the normative desirability and causal necessity of harmonisation and steering formed the dominant imaginary in health IO discourses (inter alia Global Fund Citation2005, 14; UNAIDS Citation2005c, 1, 9, 32; UNDP Citation2007, 6, 7). In contrast to market and competition devoutness, IO discourses were increasingly marked by causal beliefs that ‘fragmentation, duplication, waste and inefficient use of resources’ made it necessary to ‘ensur(e) better coordination and harmonisation among all players’ (UNAIDS Citation2005b, 2; UNDP Citation2010, 35; WHO Citation2013, 105, compare also with inter alia UNDP Citation2008, 7; UNICEF Citation2009). The preoccupation with the metagovernance norms of ‘innovation’, competition, market or network-like exchange between entities was therefore gradually superseded by a concern with lacking governability and a reinterpretation of effectiveness as requiring intentional steering.

Fixing the practical meaning(s) of harmonisation: the global task team and the subject position of ‘global leaders’

If truth claims about the ‘governance of governance’ were underpinned by a proximity to academic economics in the late 1990s, who was discursively positioned to speak truth about ‘harmonisation’ and its implications for redesigning the health field in the 2000s? In our core text corpus, The Global Task Team on Improving Coordination Among Multilateral Institutions and International Donors (2005, henceforth ‘the Global Task Team’) was referenced as an authoritative source of knowledge on the meaning and practical implications of the re-ascending harmonisation norm for the governance of health. Building on the Three Ones and the Paris Declaration, this group of experts made recommendations for improving the performance of the AIDS/HIV response. In its final report, the group argued for ‘streamlin(ing), simplify(ing) and further harmoniz(ing) procedures and practices to improve the effectiveness of country-led responses’ and hence ‘the institutional architecture of the response’ (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 7, 29). Echoing the Paris Declaration, the group therefore interpreted harmonisation in GHG as requiring alignment at the country level and recipient country ‘ownership’, rather than hierarchy between health IOs. To this end, IOs needed to clarify the division of labour and reduce ‘duplication’ by carrying out joint assessment, reporting and implementation of programmes and by strengthening coordination mechanisms at the global level (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 31). Moreover, in the roll-out of national AIDS/HIV responses, harmonisation required IOs to map ‘the existing players and their relationships’ and identify ‘duplications, gaps, bottlenecks and barriers to harmonisation’ (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 31).

The qualitative language of ‘mapping’, ‘identifying’, and ‘communicating’ and the concern with the inter-actions and ‘flows’ between organisational entities contrasts quite sharply with the aggregate measurements and deductive, academic style of reasoning that characterised the Transition Team and the Commission on Macroeconomics. However, if the Group of Experts and the Ad Hoc Committee advanced different visions of redefined institutional hierarchies, the Global Task Team preoccupied itself with ‘re-routing’ processes of exchange, removing ‘bottlenecks’ and establishing specialised organisational entities dedicated to the alignment of activities and evaluations of progress towards harmonious workflows (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 30-32). Ordering and harmonisation receive a historically specific interpretation as a continuous task of specialised institutions to facilitate a swift, ‘unhindered’ unfolding of governance processes.

A glance at the personnel composition of the Global Task Team shows that its members were understood to be ‘global leaders’ distinguished through their experience, ‘from donor and developing country governments, civil society, UN agencies, and other multi-national and international institutions’ (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 1). In other words, the expert subject position was informed by practical experience in the governance institutions and processes to be addressed. The perceived representative function that figured in narratives about the Group of Experts' composition reappeared in descriptions of the Task Team that emphasised how members were ‘high-level institutional leaders who could speak on behalf of their organisation or constituency’ (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 1, emphasis added). However, the range of actors understood to be worthy of representation now included civil society and groups disproportionately affected by the issues at hand (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 1). In contrast to previous macroeconomic preponderance, the Global Task Team was also seen to require the inclusion of representatives from developing countries in order to function as a legitimate, authoritative source on how harmonisation was to be implemented in practice (UNAIDS Citation2005a, 1).

Whilst expert groups functioned as an authoritative subject position throughout all investigated decades, the more specific discursive location that allowed their speakers to advance authoritative truth claims hence varied remarkably over time. As our discussion has shown, different expert positions drew on divergent bodies of knowledge ranging from practical, regionally specific experiences of statesmanship to abstract, presumably neutral knowledge of macroeconomic causalities that in turn supported shifts in normative imaginaries. summarises the main diachronic evolution of metagovernance norms described above, while provides a comparison of expert subject positions over time.

Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a novel approach to the study of IOs and their embeddedness in larger organisational fields that emphasises shared discourses and norms on the good governance of governance, hence deviating from the rationalist-functionalist tendency in most of the existing literature. Drawing and extending on critical IR norms research, we introduced the concept of metagovernance norms as constitutive norms concerned with good institutional order and desirable interactions in a given field of global governance. Metagovernance norms give meaning to IO-IO relations and order complex fields of global governance. At the same time, they are potentially contested and subject to meaning-struggles among IOs. Seeing the history of norms as inseparable from the discourses that articulate and shape them, we have thus put forward a discourse-analytical, relational approach that examines the interplay between metagovernance norms and contingent, contested repertoires of knowledge.

The field of global health has served to demonstrate the empirical viability of our theoretical propositions on IO interaction in larger organisational fields. Presenting findings from a case study on discourses of good governance in global health over a period of more than 30 years, we have sought to underline the value of our theoretical approach for tracing how metagovernance norms, problem constructions, causal beliefs and changing ‘expert’ subject positions intertwine, change and affect each other. This diachronic tracing, we have argued, makes their simultaneous and successive transformations particularly visible. By looking at the truth claims and vocabularies endorsed by IO expert groups, we have put forward the argument that IOs actively shape the contours of fields of governance through discourse, negotiating standards of good governance. At the same time, we have sought to show how historically specific norms on good global governance have had profound consequences for the institutional order in global health resulting in an unprecedented rise in public-private partnerships, disease-specific vertical initiatives and ‘innovative’ funding mechanisms after 1990 and in the creation of numerous harmonisation initiatives from the early 2000s onwards.

Our analysis exposed the centrality of ‘complexity’ and ‘effectiveness’ to discourses on global health governance, the changing meaning of these two signifiers and the dialectic between them. In the beginning of our period of investigation – in the early 1970s – complexity was a discursive referent used to portray largely operational issue areas in international development such as water, sanitation or medical supplies. Its invocation served to legitimise an increase in specialised governance knowledge particularly on problems of implementation or small-scale, field-specific coordination amongst selected IOs. And yet, already in the mid-1970s, we noticed a shifting understanding of complexity, with the term beginning to appear in the context of describing interactions amongst IOs and the larger institutional architecture of health development assistance. By the 1990s, the notion of complexity was deeply intertwined with collective ineffectiveness inasmuch as governance through the state and hierarchical inter-governmental IOs came to be negatively viewed as centralised and traditional, as unduly complex and thus as juxtaposed with effectiveness. Since the 2000s, the fragmentation of rule systems, the increase in the numbers of actors and actor types and the proliferation of diverse institutional arrangements have been drawn upon to portray the health governance field as complex, and thus in need of ordering. The need to harmonise and order the field hence came to be perceived as normatively necessary and crucial to achieving greater effectiveness. Privatisation and private sector-partnerships, as well as decentralisation, market principles, and networked governance were seen as their antithesis and thus logical paths to effectiveness. While the relationship between complexity and effectiveness has historically changed, it is also characterised by ambivalence today. This is thrown into particularly sharp relief when considering the changing relationship between privatisation and effectiveness. Currently, part of the perceived need to ‘order’ global health governance is justified by recourse to the problems created by privatisation, i.e. the harmful complexity that came with actor proliferation in global health. Paradoxically, discourses that focus on privatisation in global health still tend to portray it as a necessary route to overcoming the complexity of diverse actor landscapes (cf. UNAIDS 2010 PCB Report: 15; WHO 2008, 108).

In its overall aim to present global health governance as a terrain of contested knowledge, our paper has privileged meaning-struggles reflected in discourses on what constitutes ‘good’ global health governance. It thus deviates from the largely policy-analytical and solution-driven nature of much scholarly thinking on global health governance. On the one hand, our account exposed the contestedness of normative and causal beliefs on what constitutes global health and how this policy field should be governed. On the other hand, it illustrated the historically variable authority of specific expert groups and their knowledge repertoires in these discursive struggles. Thereby, we have sought to go beyond technical, apolitical portrayals of global health and to advance thinking on norms and knowledge in the study of inter-organisational relations by showing how the former’s historically specific intertwinements can be studied through diachronic inquiries on ‘expert’ subject positions, metagovernance norms, problem constructions and causal beliefs on governance. The findings of our analysis suggest that the discursive politics of changing institutional orders and the role that specific knowledge repertoires play therein merit further systematic exploration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura Pantzerhielm

Laura Pantzerhielm is a research fellow at the Chair of International Politics at Technische Universität Dresden. She previously worked at WZB Berlin Social Science Center and is a visiting researcher in the ResearchGroup “Governance for Global Health” (Freie Universität Berlin & WZB Berlin Social Science Center). Laura Pantzerhielm was a WZB-Sydney Merit Fellow at the University of Sydney and a Junior Visiting Fellow at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. She holds an M.A. in Political Science from Freie Universität Berlin and a Master’s degree in International Affairsand Human Rights from Sciences Po Paris. Email: [email protected]

Anna Holzscheiter

Anna Holzscheiter holds the Chair of International Politics at Technische Universität Dresden and is the head of the Research Group “Governance for Global Health” (Freie Universität Berlin & WZB Berlin Social Science Center). She previously worked at Freie Universität Berlin where she also obtained her PhD. Anna Holzscheiter has held fellowship positions at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and the Center for European Studies at Harvard University. Email: [email protected]

Thurid Bahr

Thurid Bahr is a research fellow in the Research Group 'Governance for Global Health’ (Freie Universität Berlin & WZB Berlin Social Science Center). She is a visiting researcher at WZB Berlin Social Science Center and was a Junior Visiting Fellow at the Geneva Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in spring 2018. She has previously worked as a research fellow at the Chair for International Organisations and Public Policy, Universität Potsdam (Prof. Dr. Andrea Liese). Thurid Bahr obtained a Master of Arts in International Relations from Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Universität Potsdam. Her research interests include transnational corporations in global governance and identity research on non-state actors. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 In our analysis of the corpus, we conducted automated searches for vocabularies that suggest normativity and/or necessity. This dictionary included verbs such as ‘shall’, ‘ought’ or ‘must’, adjectives such as ‘pivotal’, ‘key’, ‘desirable’ or ‘necessary’ and nouns such as ‘best practice’, ‘need’ or ‘priority’. Thereafter, we turned to a qualitative analysis of passages where normative vocabulary and mentions of governance practices and institutional arrangements intersect, coding these according to patterns of equation, juxtaposition, dichotomisation, groupings and sequences of occurrence between terms.

References

- Abbott, Kenneth W., Philipp Genschel, Duncan Snidal, and Bernhard Zangl, eds. 2015. International Organisations as Orchestrators. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Acharya, Amitav. 2004. “How Ideas Spread: whose Norms Matter? Norm Localisation and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism.” International Organisation 58 (02): 239–275.

- Adler, Emanuel, and Steven Bernstein. 2005. “Knowledge in Power: The Epistemic Construction of Global Governance.” In Power in Global Governance, edited by Michael N. Barnett and Raymond Duvall, 294–318. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Adler, Emanuel, and Haas Peter. 1992. “Conclusion: Epistemic Communities, World Order, and the Creation of a Reflective Research Program.” International Organisation 46 (1): 367–390.

- Almagro, Maria Martin de. 2018. “Lost Boomerangs, the Rebound Effect and Transnational Advocacy Networks: A Discursive Approach to Norm Diffusion.” Review of International Studies 44 (4): 672–693.

- Alter, Karen J., and Meunier Sophie. 2009. “The Politics of International Regime Complexity.” Perspectives on Politics 7 (1): 13–24.

- Barnett, Michael N., and Martha Finnemore. 2004. Rules for the World: International Organisations in Global Politics (Cornell: Cornell University Press)

- Bauer, Michael W., and Jörn Ege. 2016. “Bureaucratic Autonomy of International Organisation’s Secretariats.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 1019–1037.

- Biermann, Rafael. 2008. “Towards a Theory of Inter-Organisational Networking.” The Review of International Organisations 3 (2): 151–177.

- Björkdahl, Annika. 2002. “Norms in International Relations: Some Conceptual and Methodological Reflections.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 15 (1): 9–23.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loic J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Braun, Dietmar. 1993. “Zur Steuerbarkeit funktionaler Teilsysteme: Akteurtheoretische Sichtweisen funktionaler Differenzierung moderner Gesellschaften.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 24: 199–222.

- Brown, Phyllida. 1997. “The WHO Strikes Mid-Life Crisis—Next Year, the World Health Organisation is 50 Years Old. Unfortunately, There Will Be No Shortage of Party Poopers at the Birthday Celebrations.” New Scientist, January 11.

- Brown, Theodore M., Marcos Cueto and Elizabeth Fee. 2006. “The World Health Organisation and the Transition from “International” to “Global” Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health 96 (1): 62–72.

- Busch, Per Olof, and Andrea Liese. 2017. “The Authority of International Public Administrations.” In International Bureaucracy. Challenges and Lessons for Public Administration Research, edited by Michael W. Bauer, Christoph Knill, and Steffen Eckhard, 97–122. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davidson, Nicol, and John Renning. 1982. “The Restructuring of the United Nations Economic and Social System: Background and Analysis.” Third World Quarterly 4 (1): 74–92.

- Deitelhoff, Nicole, and Lisbeth Zimmermann. 2013. “Things We Lost in the Fire: How Different Types of Contestation Affect the Validity of International Norms.” Working Papers 18, Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, Frankfurt.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. London: Routledge.

- Dingwerth, Klaus, and Philipp Pattberg. 2009. “World Politics and Organisational Fields: The Case of Transnational Sustainability Governance.” European Journal of International Relations 15 (4): 707–743.

- Drezner, Daniel W. 2009. “The Power and Peril of International Regime Complexity.” Perspectives on Politics 7 (1): 65–70.

- Dunsire, Andrew. 1993. “Manipulating Social Tensions: Collibration as an Alternative Mode of Government Intervention.” MPIFG Discussion Paper 93/7, Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln.

- Engelkamp, Stephan, Katharina Glaab and Judith Renner. 2012. “In Der Sprechstunde: Wie (Kritische) Normenforschung Ihre Stimme Wiederfinden Kann.” Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen 19 (2): 101–128.

- Epstein, Charlotte. 2008. The Power of Words in International Relations. Birth of an anti-Whaling Discourse. Boston: MIT Press.

- Feachem, Richard G. A. 2002. “Commission on Macroeconomics and Health.” Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 80 (2): 87–87.

- Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organisation 52 (4): 887–917.

- Foucault, Michel. [1972] 2010. The Archeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews & Other Writings—1972-1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

- Global Fund. 2005. “The Global Fund Annual Report 2004.” Geneva. https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/1509/corporate_2004annual_report_en.pdf?u=637044316630000000

- Guilhot, Nicolas. 2005. The Democracy Makers: Human Rights and International Order. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hanrieder, Tine. 2014. “Local Orders in International Organisations: The World Health Organisation’s Global Programme on AIDS.” Journal of International Relations and Development 17 (2): 220–241.

- Hansen-Magnusson, Hannes, Vetterlein Antje, and Antje Wiener. 2018. “The Problem of Non-Compliance: Knowledge Gaps and Moments of Contestation in Global Governance.” Journal of International Relations and Development 17(2): 1–21.

- Hawkins, Darren G., David A. Lake, Daniel L. Nielson, and Michael J. Tierney, eds. 2006. Delegation and Agency in International Organisations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Holzscheiter, Anna. 2015. Restoring Order in Global Health Governance', CES Open Forum Series Center for European Studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Holzscheiter, Anna, et al. 2016. “Emerging Governance Architectures in Global Health—Do Metagovernance Norms Explain Inter-Organisational Convergence?” Politics & Governance, Special Issue: Supranational Institutions and Governance in an Era of Uncertain Norms 4: 3.

- Inoue, Keiko, and Gili S. Drori. 2006. “The Global Institutionalisation of Health as a Social Concern: Organisational and Discursive Trends.” International Sociology 21 (2): 199–219.

- Jessop, Bob. 2014. “Metagovernance.” In The SAGE Handbook of Governance, edited by Mark Bevir, 106–123. London: Sage.

- Katzenstein, Peter J., ed. 1996. “Introduction: Alternative Perspectives on National Security.” In The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics, edited by Peter J. Katzenstein, 1–27. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Koch, Martin. 2015. “World Organisations—(Re-)Conceptualising International Organisations.” World Political Science 11 (1): 97–131.

- Kooiman, Jan. 2003. Governing as Governance. London: Sage.

- Kooiman, Jan, and Svein Jentoft. 2009. “Metagovernance: Values, Norms and Principles, and the Making of Hard Choices.” Public Administration 87 (4): 818–836.

- Koops, Joachim. 2013. “Inter-Organisational Approaches.” In Europe and International Institutions: Performance, Policies and Power, edited by Knud Erik Jørgensen and Katie V. Laatikainen, 71–84. London: Routledge.

- Krook, Mona Lena, and Jacqui True. 2012. “Rethinking the Life Cycles of International Norms: The United Nations and the Global Promotion of Gender Equality.” European Journal of International Relations 18 (1): 103–127.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy—Towards a Radical Democratic Polit. London: Verso.

- Lantis, Jeffrey S., and Carmen Wunderlich. 2018. “Resiliency Dynamics of Norm Clusters: Norm Contestation and International Cooperation.” Review of International Studies 44 (3): 570–593.

- Lidén, J. 2013. The Grand Decade for Global Health: 1998–2008, Centre on Global Health Security Working Group Papers 2. London: Chatham House.

- Litfin, Karen. 1994. Ozone Discourses. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mayntz, Renate and Fritz W. Scharpf. eds. 1995. Gesellschaftliche Selbstregulierung und politische Steuerung. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus Verlag.

- Mayntz, Renate, et al. 2005. Globale Strukturen und deren Steuerung. Auswertung der Ergebnisse eines Förderprogramms der Volkswagenstiftung. Forschungsbericht 1. Köln: Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung.

- Müller, Joachim. 2001. Reforming the United Nations: The Quiet Revolution. 1st ed. The Hague: Springer.

- Niemann, Holger, and Henrik Schillinger. 2017. “Contestation ‘All the Way down‘? the Grammar of Contestation in Norm Research.” Review of International Studies 43 (1): 29–49.

- OECD. 2003. The Rome Declaration on Harmonisation. Rome: OECD.

- OECD. 2005. The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2008. The Accra Agenda for Action. Accra: OECD.

- OECD. 2012. The Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation. Busan: OECD.

- Peters, B. Guy 1998. “Managing Horizontal Government: The Politics of Co-Ordination.” Public Administration 76 (2): 295–311.

- Peters, B. Guy, and Jon Pierre. 2004. “Multi-Level Governance and Democracy: A Faustian Bargain?.” In Multi-Level Governance, edited by Ian Bache and Matthew Flinders, 75–89. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1999. The Power of Human Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Reinalda, Bob and Bertjan Verbeek, eds. 1998. Autonomous Policy Making by International Organisations. London: Routledge.

- Renner, Judith. 2013. Discourse, Normative Change and the Quest for Reconciliation in Global Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Rochester, J. Martin. 1993. Waiting for the Millennium: The United Nations and the Future of World Order, 10. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press.

- Rochester, J. Martin. 1993. Waiting for the Millennium: The United Nations and the Future of World Order, 10. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press.

- Sandholtz, Wayne. 2008. “Dynamics of International Norm Change: Rules against Wartime Plunder.” European Journal of International Relations 14 (1): 101–131.

- Sebenius, James K. 1992. “Challenging Conventional Explanations of International Cooperation: Negotiation Analysis and the Case of Epistemic Communities.” International Organisation 46 (1): 323–365.

- Sending, Ole Jacob. 2015. The Politics of Expertise. Competing for Authority in Global Governance. MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Sidibé, M, et al. 2010. “People, Passion & Politics: looking Back and Moving Forward in the Governance of the AIDS Response.” Global Health 4 (1): 1–17.

- Sørensen, Eva, and Jacob Torfing. 2007. “Theoretical Approaches to Metagovernance.” In Theories of Democratic Network Governance, edited by Eva Sørensen and Jacob Torfing, 169–182. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- UNAIDS. 2002. Report of the Executive Director, 2000–2001. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2004a. Report by the Chairperson of the Committee of Cosponsoring Organisations. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2004b. Report of the Executive Director, 2002–2003. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2004c. “Three Ones” Key Principles: Coordination of National Responses to HIV/AIDS—Guiding Principles for National Authorities and Their Partners. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2005a. The Global Task Team on Improving Coordination among Multilateral Institutions and International Donors. Geneva: UNAIDS.