Abstract

This article interrogates a tension at the heart of the principle of accountability: accountability as a principle of non-impunity of public officials versus accountability as a form of bureaucratic organisation and control. Although these dimensions are distinguishable in the abstract, their ambiguity has led to an expectations gap among both citizens and elites. The historical legacies of previous policies can exacerbate this expectations gap, leading to a variety of value trade-offs, with the potential to undermine other political values, such as political learning, consensus-building, and citizens' rights. We present examples of the trade-offs resulting from this expectations gap, focusing on moments of crisis in which such trade-offs can be seen most acutely, and highlight its role as a vehicle of global populism.

Introduction

‘There is little doubt,’ claims Matthew Flinders, ‘that the concept of accountability appears to be emerging as the über-concept of the twenty-first century’ (Flinders Citation2014). Similarly, Melvin Dubnick has remarked on ‘our collective obsession’ with accountability, signalling its use as a “cultural keyword” (Dubnick Citation2014). Enthusiasm for this “golden concept” (Bovens et al Citation2008) in various settings has spawned a host of bureaucratic instruments and waves of truth-seeking initiatives. Accountability appears in structural and institutional arrangements (vertical and horizontal), in elite discourse, and in popular demands for public officials to step down or be brought to trial. We also see increasing demands for bureaucratic justification, whether through continuous assessment, auditing, or reporting requirements. More broadly, we are part of an ‘audit society’ (Power Citation1997) and what Onora O’Neill describes as a ‘shift from cultural and social approaches to compliance to widespread reliance on formalised structures of accountability and corresponding duties of accountability’ (O’Neill Citation2014). Although the zeal for accountability does not constitute a paradigm in the Kuhnian sense, it pervades our strategies of governance and institutional design.2

Despite–or because of–its ubiquity, there is a great deal of scholarly and practical disagreement about the content and scope of the principle of accountability (Mulgan Citation2000; Behn Citation2001; Bovens Citation2010). Competing aims, ‘multiple, diverse, and often conflicting expectations’ (Dubnick and Romzek Citation1993), and value trade-offs plague the concrete attempts to instantiate accountability and are especially troubling in moments of crisis. Scholars have identified many of these trade-offs and suggest the need for increased conceptual differentiation and specification. Bovens (Citation2010) maps this scholarship by calling attention to the different approaches taken to accountability as a normative value (virtue) and as a mechanism (an instrument or policy). Our argument takes this conceptual confusion as a starting point and asks a further set of questions. What are the empirical consequences of conceptual ambiguity? What happens when actors with different conceptions of accountability address the same crisis? How are these distinct understandings entangled in their implementation? Should societies punish those responsible for financial or human rights crises (horizontal accountability) or should they focus instead on designing mechanisms and institutions to mitigate future crises (vertical accountability)? In practice, competing conceptions of accountability (as manifest in various tools and policies) collide and interact. We argue that while there is an important analytical distinction to be made between accountability as a virtuous principle of non-impunity and as a set of (fundamentally) bureaucratic systems of instruments, in practice, these discrete elements overlap.

In this exploratory argument, we suggest three potential value trade-offs that result from the collision of multiple, competing aims of accountability tools and strategies and describe some of their unintended consequences. Because tensions are most acute in times of emergency, we offer examples of efforts to pursue accountability following moments of crisis (economic, political and human rights). Although further and more precise empirical work remains to be done, considering how competing concepts interact will enrich the development of analytic frameworks for the resolution of conflicts along the lines set out by, inter alia, Bovens (Citation2010); Vermeule (Citation2007); and Gerson and Stephenson (Citation2014).

In what follows, we map the concept of accountability, focusing on a subset of the literature that outlines its attendant value trade-offs and unintended consequences. Rather than creating a new typology to add to the many (useful) existing ones, we focus on one fundamental tension at the heart of the concept as it is used in comparative governance: the distinction between accountability as the principle of the non-impunity of high office and accountability as a mode of bureaucratic organisation and control. We then discuss how multiple understandings of accountability and past accountability policies give rise to this tension in practice. We take an exploratory look at three moments when the value trade-offs resulting from an overly broad popular discourse of accountability were constrained by the expectations devolving from previous policies and strategies. We look specifically at moments of crisis because in crises and in their direct aftermath, questions of institutional design become the most pressing, and value trade-offs have the most at stake.

Accountability: unpacking an Über-concept

At its most basic, accountability refers to a relationship of account-giving between two or more actors. In comparative governance, the key relationships of accountability are between citizen and government, between the different branches of government, and between the civil service and elected officials. Accountability is maintained through a variety of structural arrangements, such as separation of powers or elections. For instance, different arrangements arise from variations in executive format, determining, for example, whether a president or cabinet is politically accountable to the parliament. But in each case, variation in the structure of the relationship is designed to limit the scope of each actor’s decision-making power according to a constitutionally defined role and to protect citizens’ capacity to remove those incumbents from office whose performance is deemed inadequate. In practice, public accountability is maintained through a vast array of mechanisms beyond elections and structural arrangements, including standards and auditing practices in bureaucratic settings and prosecutions and truth commissions in times of crisis.

There have been numerous scholarly attempts to map the concept of accountability. Typologies proliferate, distinguishing, for instance, between political, legal, professional, social, and administrative accountability (Bovens 2007; see also Dubnick and Romzek Citation1993 for a similar typology). Lindberg, in a review of the literature, counts over 100 subtypes and variants (Lindberg Citation2013, 3). Amongst the many typologies used to disaggregate the concept, we find two recurring metaphors. The first is a spatial metaphor, a distinction between horizontal mechanisms (administrative instruments, such as audits and inspections, and other institutions providing checks on power, such as high courts, opposition parties, or central banks) and vertical mechanisms (electoral or structural arrangements making representatives accountable to citizens) (Diamond Citation2004). The second metaphor is temporal; it distinguishes between punitive (retrospective or “post-factum” mechanisms, such as trials, investigations, and consequent sanctions) and preventative (prospective or “pre-factum” tools, ranging from routine audits and inspections to performance measures and reporting) modes of accountability. In practice, most contemporary public accountability instruments are horizontal and prospective and have evolved alongside the growth of the post-Second World War administrative state. They are used to ensure the appropriate behaviour and performance of bureaucrats and other public officials in liberal democracies, and they complement sanction-based mechanisms, such as investigations following a scandal.

Although both metaphors fall under the rubric of accountability, they reflect two very different logics: accountability as a principle of the non-impunity of high office vs. accountability as a mode of bureaucratic organisation with a particular aim (usually efficiency and improved performance). This distinction becomes clearer when we look at a multiplicity of political settings. In the sphere of Transitional Justice (TJ), referring to post-crisis settings dealing with the aftermath of human rights abuses, the underlying values are peace, justice and reconciliation rather than efficiency. In this case, accountability means “an explicit acknowledgement by the state that grave human rights violations have taken place and that the state was involved or responsible for them” and includes “the recovery and diffusion of truth, criminal prosecution, reparations, and efforts to guarantee non-repetition” (Skaar et al Citation2016, 33). As noted by TJ scholar Ruti Teitel, “Punishment dominates our understandings of transitional justice [as] emblematic of accountability” (Teitel, quoted in Skaar et al 2015, 30). In contrast, in administrative settings, such as public bureaucracies, a form of bureaucratic organisation aims at increased efficiency and maximised performance. Accountability might also seek to minimise misconduct, but the goal of efficiency is still the primary underlying value. Rather than prosecutions, the instruments designed to enhance accountability in administrative settings include audits, standards, and performance benchmarks.

While the two meanings are eminently distinguishable in theory and are treated separately by scholars (Bovens Citation2010), in practice, they can be elided through the solutions designed to prevent future abuse. For instance, following a financial crisis, the gross misdeeds of bankers or public officials might be punished through prosecutions. But the state might also address these breaches of accountability by establishing new regulatory regimes and transparency frameworks–in other words, new modes of bureaucratic control and organisation–to prevent future abuses. These policy responses reflect, at once, a desire for retribution and justice and for learning and reform. In the best situations, these diverse goals dovetail. At other times, however, they conflict.

Numerous scholars have documented the value trade-offs between accountability and competing values. Vermeule (Citation2007), for instance, notes a tension between accountability’s sibling values of transparency and deliberation when accountability is pursued. Similarly, Romzek and Dubnick (Citation1987) call attention to competing types of public accountability, including bureaucratic, legal, professional, and political, and point to the conflicting imperatives of each type for the central actors. Bovens (Citation2010) takes a broader view and maps the fundamental tension between accountability as a principle (virtue) and as a mechanism (set of instruments) and urges scholars to refine this family of concepts and associated frameworks for more precise analysis.

Specific sub-disciplines have studied the trade-offs inherent in particular institutional and historical settings. For instance, the trade-offs associated with accountability following human rights crises have been widely debated, especially through the ‘peace versus justice’ debate (see, inter alia, Snyder and Vinjamuri Citation2004). Likewise, public administration scholars have documented many value conflicts in bureaucratic settings. Much ink has been spilt describing the red tape and inefficiency that accompany administrative accountability mechanisms, leading to a slew of terms, such as ‘bureaupathology’ or ‘multiple accountability disorder (MAD)’ (Koppell Citation2005; Giblin Citation1981), with scholars noting the competing pressures of multiple, overlapping demands (Romzek and Dubnick Citation1987). A number of scholars, including Hood (Citation2010), Hood and Lodge (Citation2006), and Perry and Hondeghem (Citation2008), have explored the potential trade-off between retrospective accountability (aiming at punishment) and prospective accountability (aiming at increasing bureaucratic performance and efficiency) but have done so primarily within the context of public bureaucracies. The ‘new public service bargain’ (Hood and Lodge Citation2006), an accountability strategy using market mechanisms to alter the incentive structure and performance of public sector workers, aims to achieve ‘continuously higher levels of productivity, service orientation and accountability’ (Perry and Hondeghem Citation2008, 1). Whilst the literature on public management informs our understanding of the internal dynamics of public sector bureaucracies in recent decades, it does not address the trade-offs arising from the more fundamental tension between the principle of non-impunity and the practice of bureaucratic (re)-organisation and control.

Kamuf (Citation2007), articulating the perspective of critical accounting studies, introduces the concept of ‘accounterability as a counter-institution of resistance to the irreducible logic of accountability’ (2007, 253). Her critique of accountability targets the tendency of accountability norms to depend on quantification, and quantified modes of verification, for their realisation. This assessment–and the wider critical movement–indeed makes a powerful critique of the instruments of accountability commonly used as mechanisms of bureaucratic organisation and control. Its force is less trenchant when applied to the political forms of accountability demanded after crises, moments when discretion (and narrative) can be co-opted for political ends. Gerson and Stephenson (Citation2014) use the term ‘over-accountability’ to describe the ‘dark side of accountability’ and its distortions, suggesting that ‘far from being anomalies, over-accountability problems may well be quite common’ (2014, 187). Broadly, Gerson and Stephenson dissect the structure of discretion by considering which concerns and motivations might lead an agent to exercise discretion against citizens’ best interests. Their focus on the psychological consequences of institutional structure provides a valuable mapping of the perverse incentives that can emerge from accountability arrangements in routine political time (such as non-crisis, or pre-crisis time). However, their highly useful typology of over-accountability problems centres only on the incentives from immediate political circumstances, and not from historical legacies that might also shape the meaning and desirability of a given action.

What joins these two distinct principles of accountability is the way public expectations can mediate the success of any given tool of accountability. Whether or not accountability arrangements work depends significantly on the expectations of all actors. These expectations–what Romzek calls the “expectations context of accountability” (Romzek Citation1996)–are influenced by the competing, ambiguous conceptions of accountability outlined above and by the legacies of past approaches to accountability. In what follows, we explore the trade-offs and tensions resulting from this expectations gap in three post-crisis situations.

The expectations gap: ambiguity and policy legacies

The conceptual ambiguity outlined above can lead to unrealistic expectations of what a given policy of accountability can achieve. For instance, a highly visible prosecution might address the principle of non-impunity, while a less visible regulatory reform might impose bureaucratic control with the aim of preventing future abuse. These provoke very different effects and respond to very different public desires (e.g. retribution rather than prevention). Moreover, both administrative and punitive (retrospective) tools are used towards multiple ends: improved performance, justice, democratic integrity, and political learning. From the perspective of institutional design, realising all of these goals with a single institution, policy, or strategy of accountability is not always possible. More broadly, organisations committed to promoting accountability measures in public life do so in the belief that they bring legitimacy to and trust in state institutions. Yet these expectations are not always met. The expectations gap thus stems, in part, from the different meanings attached to ‘accountability’ by citizens and public officials.

A crucial omission of the literature is a consideration of how these very different meanings and their instruments interact and overlap. David Mathews’s ‘tentative hypothesis is that institutions think of accountability in informational terms while citizens think in relational terms’ (Mathews Citation2011). Although we see widespread demands from angry citizens for ‘accountability’ in the form of sanctions following crises or scandals, this does not sit well with the institutional or administrative solutions proposed by governments to prevent future crises. Popular expectations also play a role in determining whether a given accountability policy is deemed successful and contributes to a restoration of trust in the government.

The legacies of past accountability arrangements and policies can influence elite expectations of the range of available policies and public expectations of their effects. In his account of democracy-enhancing mechanisms, Vermeule (Citation2007) advocates a focus on ‘institutional design writ small’: rather than redesigning institutions whole scale, such as altering executive format or the structure of federalism to increase accountability, he advocates a small-scale design approach to permit adaptive tinkering to existing rules and institutions based on the particular contingencies of the society. To be feasible and effective, reforms must consider the decisions of previous actors. Though his argument focuses on major institutional decisions, such as a country’s basic constitutional features, his insight can be extended to crisis situations. When choosing a policy of accountability, elites must make choices based on the existing legal and regulatory frameworks. The viability of any reform must be viewed in light of past and existing arrangements’ success or failure because the public’s perceptions and expectations will depend, in part, on the historical record. The literature evaluating the effects of retrospective accountability policies in times of transition suggests prosecutions can easily be politicised, undermining political stability and precluding any real sense of justice; in fact, truth commissions might intensify existing resentments. The historical memory of previously politicised prosecutions, or even ideologically motivated regulatory reforms, can taint the public’s perception of the effectiveness and desirability of a given policy. Consequently, public expectations are not static. They change over time in response to past state actions and the perceived fairness of punishment (see Capoccia and Pop-Eleches Citation2016, for an account of the importance of fairness perception on the efficacy of TJ tools of accountability).

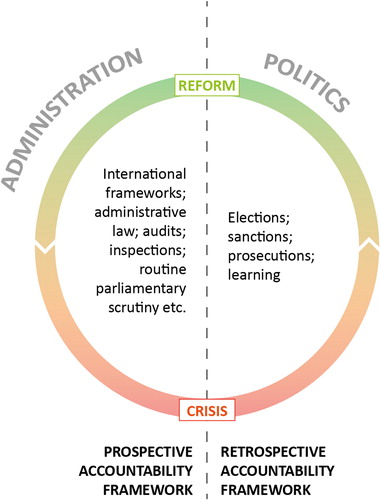

gives a dynamic picture of how the different approaches to accountability (both normative and empirical) interact over time. Crises occur in the context of a framework of laws and bureaucratic structures set up after previous crises. For instance, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932 in the United States resulted in a comprehensive regulatory framework to separate commercial from investment banking following the stock market crash of 1929. Although the framework protected the international financial system for decades, it evolved over time to become all but non-existent. As a hollowed-out framework, it became the regulatory backdrop to the financial crisis of 2008. Crucially, the meaning and efficacy of this accountability framework changed as the United States moved between periods of crisis and ‘normalcy’ and also conditioned the perception of what kind of response to the 2008 crisis would be sufficient and effective.

The left side of the graph in highlights the accountability strategies of non-crisis periods; these are characterised by a prospective accountability framework and dominated by bureaucratic actors. The right side shows how demands for retrospective accountability and effective reform (based on learning from past policy failures) intensify following a crisis or at a critical juncture but unfold in the context of certain moral and social expectations. The dialectical relationship between these phases and types of mechanisms is circular, with crises recurring over time. What is important here is how the two distinct principles of non-impunity and bureaucratic organisation, though eminently distinguishable in theory, merge in practice.

Note that in this article, we do not review the balance sheet of specific institutional mechanisms’ effects on democratic outcomes. Important work in this area has been, and continues to be done, in the field of public administration, especially by members of the Utrecht School (Bovens et al Citation2008) and by scholars in the field of Transitional Justice (e.g., Skaar et al Citation2016). Instead, in what follows, we focus on three value tensions that surface alongside demands for accountability at critical political and economic junctures. More precisely, we highlight the conflict between sanctions and learning, justice and rights, and populism and stability as potential conflicts arising from the pursuit of accountability. The first (sanctions versus learning) demonstrates a case of competing goals. The second (justice versus rights) is emblematic of the underlying value conflicts that can arise. The third (populist calls for accountability versus stability) occurs when the discourse of accountability is used for immediate political gain. Our case study approach allows us to show that the decisions made during transitions and major crises or at critical junctures often have a long-term impact on the quality of democratic institutions (Bermeo Citation1992; Diamond Citation1999; Przeworski Citation1991), respect for the rule of law (O'Donnell Citation2004), and human rights (Sikkink Citation2011; Olsen et al Citation2010).

Accountability through sanctions vs. accountability for learning and reform

In moments of crisis, citizens and elites alike call for punitive sanctions of those deemed responsible. Yet the instruments of accountability to which elites turn are more often tied to processes of reform and learning than to punishment. This tendency has intensified with the neoliberal management reforms associated with New Public Management. It is reflected both in the use of such technologies as performance indicators and regular audits, as well as in the discourse surrounding their development and adoption. For instance, in the ‘Reinventing Government’ rubric of the 1990s, the role of US federal inspectors general (IGs) was redefined. From punitive ‘gotcha’ figures, IGs evolved into ‘in-house management consultants’ (Hilliard Citation2017). This and similar de facto expansions of the meaning and uses of accountability have created a tension between expectations of accountability as a sanction and accountability as a source of learning and reform.

Learning from the past is a critical element in modern democracies, especially in times of crisis or during transition (Bermeo Citation1992). The comparative experience of a number of European countries suggests understanding how institutions failed in the past is seen, at least by some political elites, as necessary to craft effective reforms. Unfortunately, the call for retributive sanctions by political parties playing a ‘blame game’ as a strategy to deflect public scrutiny, or by the general populace looking for a scapegoat, can clash with genuine attempts to learn, deliberate, and reform. In turn, this impedes the capacity of governments to generate a sustainable post-crisis stability (Hood Citation2010). Many elites want to learn from the past to avoid a return to crisis conditions. They want to know how the relevant institutions failed to prevent the disaster and how to avoid a similar one in the future. In addition to learning, however, there can be a concomitant punitive function. The Pecora Commission, set up in the United States to identify the causes of the 1929 Wall Street Crash, not only shed light on the causes and made suggestions for innovative institutional change, but also led to high profile resignations (Pecora Citation1968). Acting on the Commission’s findings, the authors of the Glass-Steagall Act (mentioned above) separated commercial from investment banking, protecting democracies from another global financial crisis for several decades. An emphasis on performance (in this case, both personal and institutional) need not necessarily be in conflict with the quality of democracy, and in the best of times, these aims dovetail.

But not always. Iceland’s post-financial crisis experience shows the tensions that may arise between retrospective accountability policies and a political desire to learn from the past. In October 2008, Iceland’s three major banks collapsed within a week, leading to the third largest corporate bankruptcy on record. Reykjavik experienced an unprecedented wave of popular protest; public pressure on politicians to explain the causes of the crisis was one of the first reactions. Accordingly, a truth commission, the Special Investigative Commission (SIC), was established to document the reasons for the meltdown (Kovras et al Citation2017). To carry out its demanding task, the SIC was given reinforced investigative powers, including but not limited to subpoenaing witnesses, seizing evidence, and searching premises. Obstructing its investigation was punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment (ibid). It is worth noting that the Commission was geared toward uncovering the causes of the crisis and offering recommendations for reform, not scoring political points or prosecuting individuals. Moreover, setting up the SIC was the decision of the incumbent party, largely seen as responsible for the crisis, and was supported by cross-party consensus. Finally, Iceland did not have a history of politicised prosecutions. All of these factors mattered tremendously for the legitimacy of the inquiry and its ability to restore trust.

It was decided that the proceedings would take place behind closed doors, and witnesses were given guarantees that their statements could not be used against them before any court of law. These incentives were to ensure participants felt comfortable enough to share their knowledge and to ‘avoid rehearsed, standardized responses that are designed for media headlines and shifting responsibility on to others’ (Kovras et al Citation2017). When the microphones were turned off, and the official interview was over, witnesses were encouraged to talk ‘off the record’ to help commissioners understand the logic of their decisions. In short, the structure of the investigation separated partisan and punitive motives from the learning process. As Iceland did not have a prior history of politicised prosecutions, the strategy was not tainted by past failures and thus represented a powerful option for elites.

Iceland’s experience suggests an important dichotomy. On the one hand, calls for accountability could evolve into healthy new administrative practices, strong institutions, and even novel technologies enabling prospective gains for the entire society, as well as better governance, with minimum clashes with other priorities and core democratic values. On the other hand, accountability could degenerate into a discourse serving partisan interests, retrospective thinking, and electorally appealing yet populist formulas, as suggested by recent examples in the US and India, and by the Brexit referendum campaign (Adeney Citation2015; Richards and Smith Citation2017). The promise of accountability could be a particularly powerful tool in majoritarian elections and referendums aiming to promote fast change, yet as these examples suggest, the results could very quickly fall short of expectations.

Taking into account the wider discursive setting allows us to consider a further challenge to fostering public accountability: overcoming the tension between individual and collective responsibility. For a growing body of scholarship, financial crises are not necessarily caused by criminal activities punishable by law but can be traced to an entrenched culture of ‘excessive risk taking’ fostered by financial institutions and banks (Laeven and Levine Citation2009). In such contexts, it is difficult to prosecute those responsible, and it can be counter-productive if prosecutions impede attempts to reform regulations. Prosecutions and trials are highly visible, public, and adversarial procedures; documenting the past in order to learn often requires protection for participants.

Crafting reform policies frequently involves offering incentives to those who possess valuable information, including provisions for immunity, anonymity, and a depoliticised environment. Yet this is at odds with certain values and processes that accompany calls for accountability, such as transparency, visibility, the identification of perpetrators, and the initiation of criminal action. For instance, trials can, in theory, shed light on the past, but in criminal proceedings, the scope of criminal accountability is very specific and proves the guilt or innocence only of the individual(s) on trial. As such, trials explore individuals’ actions (or omissions), not broader institutional or regulatory failures. Wider cultures of corruption constituting the moral and social setting for individual misdeeds are elided when these common accountability strategies are used, heightening the tension between individual and collective responsibility. Equally important, this type of post-factum accountability is adversarial and provokes defensive responses. Individuals with valuable knowledge frame their testimonies to minimise the prospect of punishment, side-lining information not directly related to the proceedings but potentially useful for broader learning purposes.

If political elites pursue punitive accountability following crises to accommodate public calls for justice, they will render the prospect of political learning and effective reform less feasible. The ensuing tension will create a challenge for them: how can they balance the competing political goals of justice and reform? In Iceland, bankers and politicians were prosecuted, but only after the publication of SIC’s report on the broader institutional and regulatory failures behind the collapse; thus, their personal misdeeds were contextualised in a wider political narrative. Since 2011, more than 57 individuals have been charged, with roughly half sentenced to serve time in prison. It would have been extremely difficult to convince the same number of individuals to share the same quality of information with the commission had the prosecutions occurred simultaneously. This example suggests an important lesson from the case of Iceland: a broader consensus based on shared lessons has to precede accountability practices rather than the other way around.

Accountability as justice vs. accountability as rights

Since the Second World War, a discourse of accountability has pervaded post-crisis reckoning and transitions to democracy, and it is increasingly codified in international frameworks and standards. The plethora of instruments and processes designed to bring accountability to societies in transition forms the backbone of transitional justice (TJ). The transitional justice literature explores the impact of human rights prosecutions in times of transition on the quality of the emerging democracy, including respect for human rights and the rule of law (Sikkink Citation2011; Olsen et al Citation2010). As a growing number of repressive leaders and warlords end up in jail, a ‘justice cascade’ has gained momentum in the policymaking world, sparking the interest of academics (Sikkink Citation2011). Most major international organisations and think-tanks have added criminal trials to the toolkit of post-conflict democratisation (United Nations Citation2006).

In a nutshell, most proponents of transitional justice see a positive relationship between policies of accountability and the democratisation process. Punishing perpetrators or documenting human rights violations not only addresses victims’ rights but also has the potential to restore trust between state and society. Accountability policies, in theory, should be transparent, depoliticised, and regulated by rules set in law. When politics fails to settle a crisis, the law is brought in as a seemingly impartial arbiter to redress victims’ legal rights.

Still, in transitional settings, victims often have different priorities and conflicting sets of rights (Kovras Citation2017; Hall et al Citation2017). Moreover, the legacy of past policies can shape victims’ preferences. They do not always prefer ‘accountability’ as such, at least not in the punitive sense of the term. For instance, when the relatives of those who disappeared during a period of violence or state repression face the choice of prosecuting those responsible for the abduction or providing amnesties in exchange for learning about their loved ones’ whereabouts, they do not necessarily prefer the former. Hence, the pursuit of justice under the rubric of accountability may directly conflict with citizens’ preferences. In practice, the outcomes of accountability-driven actions are often co-opted for political use; the connection of politics and legalism can be tenuous. Many societies faced with post-2008 financial crises had earlier experienced violent conflict leading to large-scale violations of human rights and attendant attempts at restorative justice.

The post-conflict experience of Cyprus is especially revelatory. During two waves of violence (1963–1974), approximately 2,000 persons went missing from Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot communities. The Committee on Missing Persons (CMP), a UN-led humanitarian committee set up in 1981 to find the missing, remained a dead letter for years while relatives brought a number of cases to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). In 2005, in an unexpected move, the leaders of the two communities decided to resume the activities of the CMP and since then, it has become a tremendously successful bi-communal project, exhuming more than half of the 2,000 missing persons and identifying most of them, allowing thousands of families to start the healing process.Footnote1 Although explaining this policy change is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth highlighting a critical aspect of the CMP for broader accountability studies. Because of the covert nature of the crime of the missing, identifying victims requires eyewitnesses (often perpetrators) to come forward and share information about gravesites. Yet revealing potentially incriminatory evidence deters eyewitnesses from collaborating. To overcome this obstacle, the CMP offered immunity from prosecution and ensures anonymity and confidentiality (Kovras Citation2017). A number of countries around the world, including Northern Ireland and Colombia, have used a similar formula to deal with victims of clandestine political violence (Dempster Citation2016).

This is often perceived as ‘impunity’ by human rights watchdogs and international advocacy networks and, therefore, as conflicting with a more abstract commitment to accountability. In an illustrative example, Amnesty International attacked the ‘Law and Amnesty Law’ adopted in 2005 in Colombia to deal with the disappeared, on the grounds that it ‘fails to comply with international standards on victims’ right to truth, justice and reparation’ (Amnesty International Citation2005). In fact, Human Rights Watch went so far in its pursuit of accountability in Colombia as to oppose the negotiated settlement during the peace referendum of 2016, siding with its extreme right-wing opponents. At the same time, the US State Department refused to issue visas to FARC members, undermining President Santos’ plans to sign the agreement at UN headquarters ahead of the referendum vote.Footnote2

These examples from post-conflict societies suggest the inherent tensions between accountability and the often controversial requirements of peace processes (Loizides Citation2016). The Cypriot case also signals the legacy of previous uses of prosecutions in Cyprus: they have taken place in a politicised context and are often considered to lead to unjust outcomes (Bozkurt and Yakinthou Citation2012). As noted in the Icelandic bank crisis, a broader consensus based on shared lessons has to precede effective accountability practices. The Cypriot case historically lacked this consensus and the institutions that foster it, demonstrating instead a politicised context leading to unjust outcomes that further undermined the objectives of good governance (Bozkurt and Yakinthou Citation2012; Kovras et al Citation2017). Unlike Iceland, the post-conflict and post-2008 financial crises often led to conflicting partisan narratives. Interestingly, the government-appointed fact finding committee did not meet expectations, with two out of three members resigning in the process (Pegasiou Citation2017). Moreover, the auditor-general himself not only exceeded his authorities on governance issues but also used it to engage in discussions of the long-standing Cypriot problem of specifically targeting the funding for pro-reconciliation activities and media.Footnote3 In such situations, contradictory decisions, politicisation and excessive over-accountability practices divide the public and weaken the legitimacy of democratic processes and institutions. When public expectations of prosecutions are low, the political will to pursue them diminishes.

The examples cited above raise important political, ethical, and legal questions. For instance, what happens when a particular set of international accountability norms clashes with another set of citizens’ rights? The experience of the families of the disappeared in the aftermath of state repression is illustrative. On the one hand, according to the international legal framework, states have a duty to carry out an ‘effective investigation’ and to ‘prosecute’ those responsible for the crime (International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearances 2006). On the other hand, the families have the right to ‘know the truth,’ including the right to have access to and obtain information about the death of a loved one (see Kurt v. Turkey Citation1998; Cyprus v. Turkey 2001). Families have an overlapping ‘right to reparation’ which includes the right to identify and bury their loved ones (International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearances 2006). In effect, these rights conflict with international standards of retributive accountability as supported by, for instance, Amnesty International. The two sets of rights are mutually exclusive in this case.

The effectiveness of an exhumation policy rests on the absence of criminal proceedings, and any effort to prosecute individuals is achieved at the expense of forensic truth, as eyewitnesses will be understandably reluctant to continue to share information that would incriminate them in the future. This is common knowledge within the CMP, which avoided the pitfalls of politicisation and selective persecution in its exhumation policies taking place in the absence of an overall political settlement. As a Turkish-Cypriot member of the CMP stressed: ‘This project is working because grassroots people are giving us information and if we start dealing with punishment, these people are not going to give us any more information. It is not time to do [criminal investigations] now’ (Personal Interview 2008).

In other words, accountability norms and what victims want frequently clash, and despite Amnesty’s vocal support for punitive accountability, victims may prioritise other results. Although the families in Cyprus are very familiar with the legal instruments and have brought their cases to domestic and international courts, none, from either side of the divide, has initiated a legal proceeding. The puzzle is even more intriguing when we consider 700 families have now identified the victims and no longer depend on the testimony of perpetrators. They could go to court and seek punitive accountability through the justice system. But they know that even one prosecution will bring the process to a halt, and hundreds of other families will be left trapped in ambiguous loss. In effect, they prioritise the right of those other families to learn the truth about the whereabouts of their loved ones over their own right to seek legal redress and justice.

A recent quantitative survey of victims in Bosnia turns up a similar pattern (Hall et al Citation2017). The evidence suggests exposure to direct violence and loss is associated with support for retributive justice measures, whilst greater present-day interdependence with perpetrators, particularly among displaced persons returning to their homes, is associated with support for restorative justice measures. In Bosnia, a tough resolve approach to former war criminals, particularly in local police units, was instrumental in facilitating voluntary peaceful return. While accountability at some levels facilitated the peace process, Bosnia also benefited from restorative justice initiatives aiming to reconcile the three communities through power-sharing arrangements. In fact, as the cases of Cyprus and Colombia suggest, improving intercommunal relations following ethnic cleansing may rely on restorative justice mechanisms. When faced with competing values, citizens do not automatically prioritise accountability over such things as equal opportunities or material rewards. They may resent the burden imposed on them by an uncritical adoption of a very narrow set of accountability standards in the name of justice and human rights.

Accountability as populist resource vs. accountability as source of stability

Much of the political force of accountability lies in its popular use. The very discourse of accountability can be both a popular (often populist) resource and a source of improved governance. Conventional wisdom assumes countries with weak institutions and legacies of politicisation of justice are likely to misuse accountability processes. For example, when legal tools become partisan tools and committees of inquiry or prosecutions are used to score political points, the instrumental use of justice fails to bring real accountability and discredits the entire judicial institution. Populism trumps stability.

Popular calls for accountability intensify at critical junctures, such as during political transitions marking the end of a period of state repression or in the aftermath of economic, environmental, and other disasters (Boin et al Citation2008). Public demands to diagnose what went wrong and to hold those responsible to account dominate public debates, constraining the range of policy responses available to political elites. In theory, this process is crucial for the restoration of trust between state and society. An over-emphasis on policies of accountability, however, makes negotiations among political parties adversarial, confrontational, and often punitive, limiting the prospect of harmonious decision-making and precluding the consensus needed for effective reform. In times of crisis, demagogues ride the tide of popular discontent and hijack calls for accountability to play the blame game against opponents, further trimming democratic legitimacy. The historical memory of such politicisation exacerbates elites’ unwillingness to pursue such policies and negatively influences the public’s perception of their legitimacy.

Consider the comparative experience of post-recession Europe. In the recent economic crisis, political elites in Greece, Ireland, Cyprus and Spain had to address growing popular pressure to find those responsible and hold them to account. This was visible in the waves of street protests and the emergence of pro-accountability social movements. At the same time, political elites sought a basic consensus to legitimise fundamental policies of institutional and economic reform. A quick economic recovery requires effectiveness and continuity in decision-making, more achievable when supported by a broad spectrum of political elites. Inclusivity in the decision-making process is paramount for democracy to be legitimate and for institutional reforms to succeed.

Greece is illustrative of this tension. Because of its large public debt, with the recession, it experienced a major economic shock and faced external economic supervision. This was followed by a prolonged political crisis, violent street protests, and the electoral rise of the far right (Lamprianou and Ellinas Citation2017). New populist political parties sprang out of grassroots mobilisation; some had electoral success. The push for accountability in a party system dominated by two mainstream parties–both seen as responsible for the crisis–became a central promise in electoral campaigns.Footnote4 The excessive focus on retributive policies to address the past torpedoed any efforts to act in concert across the political spectrum and curtailed the legitimacy of even the most basic decisions. Although polarisation, instability and the fragmentation of the Greek political system should also be attributed to other entrenched institutional problems (including the institutionalised single-party ‘eccentric majoritarianism’), calls for accountability precluded any form of cross-party consensus (Kovras and Loizides Citation2014). In times of economic stress, effective governance often necessitates consensus with the opposition who may have skeletons in its closet. Threats of retrospective retribution (exposing the skeletons) frame political debates in a confrontational way, however, precluding consensus. Moreover, the legacy of the past in countries dealing with the aftermath of financial crisis is telling: grassroots activists and policymakers in Spain, Portugal, and Greece all expressed scepticism that prosecutions and parliamentary committees of inquiry could avoid a high level of politicisation, thus conditioning expectations of what such an accountability strategy might achieve.

These dilemmas are not limited to economic crises. The debate between backward-looking accountability and forward-looking reconciliation was first identified in the transitology literature (inter alia, O'Donnell et al Citation1986; Linz and Stepan Citation1996). It is now commonly understood that negotiated transitions are more likely to consolidate democracy if they are based on the inclusion of as many parties as possible, exemplified in the all-party coalitions of Northern Ireland following the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement (O’Leary and McGarry Citation2016). Bringing contentious issues into negotiations, like accountability for past crimes, increases the risk of alienating powerful actors who have something to hide. To avoid going to jail, they may prefer to become spoilers and derail negotiations. For example, while the UN was brokering a peace agreement in Northern Uganda, based on an amnesty to induce key actors to sit at the negotiating table, the International Criminal Court (ICC) indicted Joseph Kony, a local warlord. The peace talks immediately collapsed, and hostilities continued for years, with a heavy toll on human lives (Vinjamuri Citation2010). As the case suggests, pushing for accountability can remove the political flexibility, inclusivity, and consensus required to support democratisation. This conclusion is supported by the Spanish and Irish cases. In Spain, the transition from Francoism in the mid-1970s was only possible because of a broad political consensus to support democracy and the cautious decision to skip accountability (Linz and Stepan Citation1996). In Northern Ireland, a decision to avoid dealing with the past set the stage for a non-violent transition to inclusive power-sharing and led to an unprecedented period of democracy, peace, stability, respect for human rights and prosperity (McEvoy and Mallinder Citation2012).

We should also note that the confluence of these factors could open the door to populist leaders. The October 2018 elections in Brazil bear this out; here, economic hardship, (alleged) corruption scandals, and lack of government accountability paved the way for an anti-system message (Spektor Citation2018). Branded by the international media as the ‘Brazilian Trump,’ Jair Bolsonaro was quick to fit the bill with a polarising populism fiercely opposing gender equality, migration and environmental protections for the Amazon basin. His opponent and former leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was imprisoned during the presidential campaign on alleged corruption scandals and was prevented from running for president despite his lead in the polls. He was subsequently described by international left activists as the ‘world’s most prominent political prisoner’ although his story received very little international attention until the catastrophic August 2019 Amazon forest fires.Footnote5 Bolsonaro’s instrumentalisation of the principle of non-impunity of high office demonstrates an important mechanism in the rise of populism and constitutes an important warning against legal mechanisms sanctioning public officials from elections. Courts prevented Lula himself from running as a candidate. This example demonstrates the way the discourse and practices of accountability surrounding a corruption scandal can be used instrumentally to weaken genuine accountability.

Conclusion

As Dubnick and Frederickson observe, “We commonly equate democracy with accountable governance,” but the whole-hearted pursuit of accountability may lead to conflicts and value trade-offs (Dubnick and Frederickson Citation2011). The inevitable gap between the promise and the reality of accountability, stemming from its conceptual ambiguity both in the abstract and in practical application, can undermine any beneficial effects accountability may have on democracy. Moreover, the historical legacy of failed policies–whether bureaucratic-regulatory or prosecutorial–further influences the range of possible strategies available to elites, and affects the public’s perception of their efficacy and legitimacy.

Although many of the goals of accountability are indispensable to the health of democracy, their pursuit often leads to conflicts and trade-offs, with attendant moral and pragmatic disadvantages. The potential consequences of these conflicts are many, but can often be addressed through consensus politics and institutional design. The trade-off between sanctions and learning can lead to missed reform opportunities, and choosing one value over the other can set precedents for the efficacy of future attempts to govern after crisis. Similarly, pursuing justice for the perpetrators of wrongdoing can preclude the realisation of victims’ parallel rights (or simply preferences). The choice of which value to pursue will condition citizens’ expectations of the legitimacy and effectiveness of such policies in future crises. Finally, the appropriation of accountability by populists can curtail the legitimacy of a democracy in crisis and hinder the development of both representative and deliberative approaches to democratic decision-making. This can undermine future attempts to restore accountability by delegitimizing the strategies used to pursue it. Although not all cases will present such clear-cut value trade-offs, our stylised examples illustrate the potential perils of decision-making after crisis.

These trade-offs pose an immediate problem of institutional design. Yet the solution to this problem cannot be derived from a set of attributes or principles; even exquisitely designed institutions can be subverted by actors seeking multiple, incompatible goals. Our argument, which highlights the effects of both conceptual ambiguity and policy legacies on expectations of accountability policies, complements existing literature on the ‘golden concept’ of accountability. Any strategy undertaken by policy makers following crisis must take into account the concrete conceptions and expectations of accountability that result from the historical legacy of past approaches to accountability and the conceptions of multiple actors. The primary design challenge, therefore, is to identify the tensions of accountability in each crisis, and to minimise the wide range of unintended consequences that inevitably issue from each experimentation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nadia Hilliard

Dr. Nadia Hilliard is currently Lecturer in US Studies at the Institute of the Americas, University College London. She received her DPhil from the University of Oxford, and later acted as Postdoctoral Research Associate for the Accountability After Economic Crisis Project, City, University of London. Her book, The Accountability State: US Federal Inspectors General and the Pursuit of Democratic Integrity, was published by the University Press of Kansas in 2017. Email: [email protected]

Iosif Kovras

Dr. Iosif Kovras is Reader (Associate Professor) of Comparative Politics at City, University of London and Visiting Associate Professor, University of Cyprus, Department of Social and Political Science. He was awarded his Ph.D from Queens University Belfast in 2011 and is the PI of the ESRC-funded project, Accountability After Economic Crisis. His most recent book, Grassroots Activism and the Evolution of Transitional Justice (Cambridge University Press, 2017) received Honorable Mention in the International Studies Association book award. Email: [email protected]

Neophytos Loizides

Neophytos Loizides is Professor of International Conflict Analysis the University of Kent. He received his PhD at the University of Toronto. Dr. Loizides is the author of The Politics of Majority Nationalism: Framing Peace, Stalemates, and Crises published by Stanford University Press (2015) and Designing Peace: Cyprus and Institutional Innovations in Divided Societies published by the University of Pennsylvania Press (2016). Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Specifically, 1,119 victims were unearthed and 701 identified by November 2016 (CMP 2016; Loizides Citation2016).

2 Human Rights Watch also condemned amnesty attempts in Tunisia, arguing they would constitute a final blow to democratic transition.

3 In July 2019, a Russian-made missile launched by Syria accidentally hit the village of Vouno in the northern part of Cyprus. Cyprus Mail become the target of the auditor general of the Republic of Cyprus for its mistaken use of the changed (illegal) name of Tashkent in its reporting. The Greek Cypriot inhabitants of Vouno were ethnically cleansed in 1974 while their houses were given to Turkish Cypriot survivors of a massacre in Tochni, perpetrated by Greek Cypriot militia and for which no accountability processes have ever been pursued. This was the case for both Greek and Turkish Cypriot victims during the 1963-1974 era, demonstrating the selective use of narratives and accountability practices in the island. (Cyprus Mail Citation2019).

4 Between 2009 and 2016, more than 120 bankers, former politicians, businessmen and civil servants were prosecuted or convicted on charges related to the economic meltdown.

5 McEvoy, John, “Jeremy Corbyn Joins International Outcry to Free Brazilian Political Prisoner Lula da Silva,” The Canary, 29 July 2019.

References

- Adeney, Katharine (2015) ‘A move to majoritarian nationalism? Challenges of representation in South Asia’, Representation, 51:1, 7–21

- Amnesty International (2005) “Colombia: justice and peace law guarantees impunity,” Press release, April 26

- Behn, Robert (2001) Rethinking democratic accountability (Washington, DC: Brookings)

- Bermeo, Nancy (1992) ‘Democracy and the lessons of dictatorship’, Comparative Politics, 24:3, 273–291

- Boin, Arjen, Allen McConnell and Paul ‘T Hart (eds.) (2008) Governing after crisis: the politics of investigation, accountability and learning (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Bovens, Mark (2010) ‘Two concepts of accountability: accountability as a virtue and as a mechanism’, West European Politics, 33:5, 946–967

- Bovens, Mark, Thomas Schillemans and Paul’ T Hart (2008) ‘Does public accountability work? An assessment tool’, Public Administration, 86:1, 225–242

- Bozkurt, Umut and Christalla Yakinthou (2012) ‘Legacies of violence and overcoming conflict in Cyprus: the transitional justice landscape’, PRIO Cypus Centre, Report 2

- Capoccia, Giovanni and Grigore Pop-Eleches (2016) “The consequences of punishment: transitional justice and democratic support in Post-War Germany,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association

- Cyprus Mail (2019) “Our view: auditor-general has abused his position yet again in attack on Cyprus Mail,” July 2, 2019, <https://cyprus-mail.com/2019/07/02/our-view-auditor-general-has-abused-his-position-yet-again-in-attack-on-cyprus-mail/>

- Cyprus v. Turkey (2001) (Application no. 25781/94), judgment of May 10

- Dempster, Lauren (2016) ‘The republican movement, ‘disappearing’, and framing the past in Northern Ireland’, International Journal of Transitional Justice, 10:2, 250–271

- Diamond, Larry (2004) ‘The quality of democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 15:4, 25–26

- Diamond, Larry (1999) Developing democracy: toward consolidation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press)

- Dubnick, Melvin J and H George Frederickson (2011) Public accountability: performance measurement, the extended state, and the search for trust (Dayton: The Kettering Foundation), 18

- Dubnick, Melvin J (2014) ‘Accountability as a cultural keyword’, in Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability, edited by Mark Bovens, Robert E Goodin, and Thomas Schillemans (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 649–654

- Dubnick, Melvin J (2011) ‘Move over Daniel: we need some ‘accountability space’, Administration & Society, 43:6, 704–716

- Dubnick, Melvin J and Barbara S Romzek (1993) ‘Accountability and the centrality of expectations in American public administration’, In Research in public administration, edited by James L. Perry (Greenwich CT: JAI Press), 37–78

- Flinders, Matthew (2014) ‘The future and relevance of accountability studies’, in Mark Bovens, Robert E. Goodin, and Thomas Schillemans (eds) The oxford handbook of public accountability (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 661

- Garcia-Godos, J. (2015) ‘It’s about trust: Transitional justice and accountability in the search for peace’, in Cecilia M. Bailliet and Kjetil M. Larsen (eds) Promoting Peace Through International Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 2014 ISBN 9780198722731. Chapter 16, 321–343

- Gerson, Jacob E and Matthew C Stephenson (2014) ‘Over-accountability’, Journal of Legal Analysis, 6:2, 185–243

- Giblin, Edward J (1981) ‘Bureaupathology: the denigration of competence’, Human Resource Management, 20:4, 22–25

- Hall, Jonathan, Iosif Kovras, Djordje Stefanovic and Neophytos Loizides (2017) ‘Exposure to violence, war-related losses and attitudes towards transitional justice: evidence from post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina’, Political Psychology, Vol. 39, No. 2

- Hilliard, Nadia (2017) The accountability state: U.S. Federal inspectors general and the pursuit of democratic integrity. (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas)

- Hood, Christopher (2010) The blame game: spin, bureaucracy, and self-preservation in government (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

- Hood, Christopher and Martin Lodge (2006) The politics of public service bargains: reward, competency, loyalty – and blame (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- Kamuf, Peggy (2007) ‘Accounterability’, Textual Practice, 21:2, 251–266

- Koppell, Jonathan (2005) ‘Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of ‘multiple accountabilities disorder’, Public Administration Review, 65:1, 94–108

- Kovras, Iosif and Neophytos Loizides (2014) ‘The Greek debt crisis and Southern Europe: majoritarian pitfalls?’, Comparative Politics, 47:1, 1–20

- Kovras, Iosif (2017) Grassroots activism and the evolution of transitional justice: the families of the disappeared. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Kovras, Iosif, Shaun McDaid and Ragnar Hjalmarsson (2017) ‘Truth commissions after economic crises: political learning or blame game?’, Political Studies, forthcoming

- Kurt v. Turkey (1998) (Application no. 2476/94), judgment of May 25

- Lamprianou, I and A A Ellinas (2017) ‘Institutional grievances and right-wing extremism: voting for golden dawn in Greece’, South European Society and Politics, 22:1, 43–60

- Laeven, Luc and Ross Levine (2009) ‘Bank governance, regulation and risk taking’, Journal of Financial Economics, 93:2, 259–75

- Lindberg, Staffan (2013) ‘Mapping accountability: core concept and subtypes’, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 79:2, 202–26

- Linz, Juan J, and Alfred Stepan (1996) Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe, South america, and post-communist Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press)

- Loizides, Neophytos (2016) Designing peace: Cyprus and institutional innovations in divided societies. (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press)

- Mathews, David (2011) Foreword, in Melvin J Dubnick and H George Frederickson (eds) Accountable governance: problems and promises (London: ME Sharpe), ix

- McEvoy, John (2019) “Jeremy Corbyn Joins International Outcry to Free Brazilian Political Prisoner Lula da Silva,” The Canary, 29 July

- McEvoy, Kieran, and Louise Mallinder (2012) ‘Amnesties in transition: punishment, restoration, and the governance of mercy’, Journal of Law and Society, 39:3, 410–440

- Mulgan, Richard (2000) ‘Accountability: an ever expanding concept?’, Public Administration, 78:3, 555–573

- O'Donnell, Guillermo, Philippe C Schmitter and Laurence Whitehead (1986) Transitions from authoritarian rule: Southern Europe Vol. 1 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press)

- O'Donnell, Guillermo A (2004) ‘Why the rule of law matters’, Journal of Democracy, 15:4, 32–46

- Olsen, Tricia D, Leigh A Payne, and Andrew G Reiter (2010) ‘The justice balance: when transitional justice improves human rights and democracy’, Human Rights Quarterly, 32:4, 980–1007

- O’Leary, Brendan and John McGarry (2016) The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland (London: Bloomsbury Academic)

- O'Neill, Onora “(2014) Trust, trustworthiness and accountability,” in Nick Morris and David Vines (eds) Capital failure: restoring trust in financial services (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- Pecora, Ferdinand (1968) Wall street under oath (London, UK: Cresset Press)

- Pegasiou, Adonis (2017) ‘EU coordination in Cyprus: The limits of Europeanisation in times of crisis’, in Managing the Euro Crisis: National EU policy coordination in the debtor countries (Abingdon: Routledge)

- Perry, James L and Annie Hondeghem (2008) ‘Building theory and empirical evidence about public service motivation’, International Public Management Journal, 11:1, 3–12

- Personal Interview (2008) Nicosia, 7/16

- Power, Michael (1997) The audit society (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- Przeworski, Adam (1991) Democracy and the market: political and economic reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Richards, Dave and Martin Smith (2017) ‘‘Things were better in the past’: Brexit and the Westminster fallacy of democratic nostalgia’, British politics and policy at LSE

- Romzek, Barbara S (1996) ‘Enhancing accountability’, in James L. Perry (ed) Handbook of public administration. 2nd ed (San Francisco: Jossey Bass), 97–114

- Romzek, Barbara S and Melvin J Dubnick (1987) ‘Accountability in the public sector: lessons from the challenger tragedy’, Public Administration Review, 47:3, 227–238

- Sikkink, Kathryn (2011) The justice cascade: how human rights prosecutions are changing world politics (New York: W.W. Norton)

- Skaar, Elin, Jemima Garcia-Godos and Cath Collins (2016) Transitional justice in Latin America: the uneven road from impunity towards accountability (London and New York: Routledge)

- Snyder, Jack and Leslie Vinjamuri (2004) ‘Trials and errors: principle and pragmatism in strategies of international justice’, International Security, 28:3, 5–44

- Spektor, Matias (2018) ‘It’s not just the right that’s voting for Bolsonero. It’s everyone’, Foreign Policy, October 26 <https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/10/26/its-not-just-the-right-thats-voting-for-bolsonaro-its-everyone-far-right-brazil-corruption-center-left-anger-pt-black-gay-racism-homophobia/>

- United Nations (2006) ‘Rule of law tools for post-conflict states: truth commissions’, HR/PUB/06/1

- Vermeule, Adrian (2007) Mechanisms of democracy: institutional design writ small (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- Vinjamuri, Leslie (2010) ‘Deterrence, democracy, and the pursuit of international justice’, Ethics & International Affairs, 24:2, 191–211