Abstract

Covid-19 is the latest blow to the ailing liberal international order, which has faced a series of challenges in the postwar era. This article traces the global spread of the virus scaled to population and case fatality rates of different countries. Using inferential statistics, I find that liberal democracies have higher case fatality rates than other regime types and offer some plausible explanations for why. Systemically, I show how the spread of the virus complicates the implementation of policies consistent with liberal international order, potentially destroying the order in which liberal democracies participate. Given the paucity of the data as well as cross-country reporting differences in a still evolving crisis, these findings provide a first social scientific cut over the first half year of the pandemic rather than a final assessment of its consequences.

Introduction

Covid-19 is the latest blow to the ailing liberal international order, which has faced a series of challenges in the postwar era. The most recent trials range from the Afghan and Iraq wars against terror, to the return of great power politics, to the financial crisis, and to the rise of populism, especially right-wing populism. Even the dominant power supporting the liberal international order—the United States—has succumbed to right-wing populism under the presidency of Donald J. Trump. Covid-19 is the latest addition to the long succession of tribulations.

Beyond the immediate danger Covid-19 poses to human health, its economic, political, and social reverberations are far-reaching. This paper asks whether Covid-19 is especially threatening to interdependent and inter-connected liberal democracies by posing a series of related questions. First, has Covid-19 spread more quickly and proved more fatal in liberal democracies than in countries with other regime types? Second, what special challenges does Covid-19 pose for liberal democracy? Third, what repercussions could Covid-19 have for liberal democracies at the systemic level; in other words, how might the preferred order of most liberal democracies—the liberal international order—be affected by Covid-19? Since the crisis is still unfolding with significant open-ended developments, this paper does not aim to provide any definite assessment of the Covid-19 impact on liberal democracies or liberal international order. Rather, it seeks to add to our existing knowledge about the evolving crisis through a preliminary social scientific cut based on the available data. Using inferential statistics, I find that liberal democracies have higher case fatality rates than other regime types and offer some plausible explanations for why. Systemically, I also show how the spread of the virus complicates the implementation of policies consistent with liberal international order, thereby threatening the order in which liberal democracies participate.

Before probing these questions, I offer a brief summary of what we know about the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the Covid-19 disease and point to data limitations. The paucity of data concerning the number of Covid-19 cases and related deaths should give us pause in drawing hard conclusions based on the available information.

What we know about the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the covid-19 disease: empirics

Background

Covid-19 is a severe acute respiratory illness caused by SARS-CoV-2, a new coronavirus. Scientists believe Covid-19 originates in bats (Zhao et al 2020). Three mechanisms for the emergence of the virus have been debated—zoonotic transfer following natural selection in an animal host; natural selection in humans following zoonotic transfer; selection during laboratory escape (Andersen et al Citation2020).Footnote1 Scientists do not know whether the virus had already mutated before infecting humans, as implied by the first mechanism, or if it mutated after infecting humans, as implied by the second mechanism (Andersen et al Citation2020). However, scientists agree on the implausibility of the virus originating in a lab (Andersen et al Citation2020).

Some infected humans develop fever, dry cough, sore throat, fatigue and body pain while others display mild symptoms such as loss of smell and taste or remain entirely asymptomatic. Surgical facial masks likely prevent Covid-19 transmission from symptomatic individuals (Leung et al Citation2020). The overall case fatality ratio has been estimated to be 2 percent in China and 2.7 percent outside China (Verity et al Citation2020; Wu et al Citation2020). Preliminary research suggests that individuals belonging to blood group A face a higher risk of Covid-19 infection compared to non-A blood groups, and that individuals belonging to blood group O face a lower risk of Covid-19 infection compared to non-O blood groups (Zhao et al 2020; Peter 2020). Symptomatic infections and the case fatality rate is generally understood to increase with age, particularly in persons above 59 years (Wu et al Citation2020). Individuals with underlying conditions such as cancer, type 2 diabetes and obesity have been shown to be at greater risk; individuals with high blood pressure and asthma, and those that smoke, may also be at higher risk (CDC Citation2020).

Furthermore, data availability and reporting styles (discussed below) explain some of the country differences in recorded cases and case fatalities, though government policy also plays a role.

Data limitations

The Covid-19 data presented in this study was sourced from the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDPC) and from Worldometer in June 2020. Making cross-country comparisons is inherently difficult due to the ongoing evolution of the pandemic and the uncertainty of the country distribution of cases and deaths. Consequently, we can only base our empirical investigation on tentative Covid-19 related infection and mortality rates.

The continuously evolving situation implies that future infection and mortality rates might very well differ from current rates. Country differences in data availability, reporting and accuracy could further bias cross-country comparisons. Comparing liberal democracies and other regime types is likely to remain difficult for the foreseeable future due to better statistics in liberal democracies. State capacity and prioritization of statistical precision may very well be structurally lower in many unfree regimes, such as China, Russia or Iran because they are less likely to face ballot costs as a result of deceitful reporting. On the flip side, the potential electoral cost faced in democracies as a result of mis-managing the pandemic, could also create incentives to report inaccurately (or at least to make the data more difficult to access) in democracies with upcoming elections, as in the US.

Inadequate testing manifests across regime types due to limited large-scale tests and the prevalence of targeted tests instead of randomized tests. Non-randomized tests are especially problematic when estimating case fatality rates given the high rate of asymptomatic carriers, thought to amount to 80 percent of known infected cases (Day Citation2020). Authoritarian regimes may have incentives to downplay the number of cases, though stronger incentives exist to downplay the number of Covid-19 related deaths. Stark differences, without any obvious correlation with regime type, also exist in terms of how countries report Covid-19 related deaths. Some countries, like Russia, only count Covid-19 as a cause of death if proven, artificially deflating the case fatality rate as compared to countries where Covid-19 automatically counts as the cause of death if found in a deceased person infected with SARS-CoV-2. Some countries, such as the United States, base numbers of Covid-19 deaths on death certificates. Countries such as Finland and the UK report only those Covid-19 deaths that occur in hospitals whereas Sweden also reports those in private, retirement or nursing homes, which reportedly account for 75 percent of all Covid-19 deaths in Sweden.

While systematic differences likely exist in statistical reporting across regime types, differences also exist amongst liberal democracies. Without universal or random testing, it is impossible to know the extent or deadliness of the pandemic. Eventually, we will be able to assess the excess mortality rate by comparing the mortality rate during the pandemic with the mortality rate in normal years. In the meanwhile, an analysis of the virus’ trajectory in its initial phase remains useful for drawing tentative conclusions about the political geography of COVID-19 and its international ramifications.

Empirical analysis

To examine how Covid-19 manifests across regime types, I use t-tests, to compare the respective means of the case per capita rate and the case fatality rate between liberal democracies and other regime types using different measures of liberal democracy. I also perform this mean comparison for other measures of openness, specifically, the degree of globalization as measured by the extent of countries’ international arrivals.

COVID-19 as a liberal democratic curse?

The crisis has sparked a debate on whether a democratic or authoritarian advantage exists in dealing with the crisis (Alon and Li Citation2020; Brands Citation2020; Norrlöf Citation2020; Trofimov Citation2020) echoing previous debates on the benefits and viability of different regime types (Gat Citation2007; Deudney and Ikenberry Citation2009; Kagan Citation2019). Has COVID-19 spread more quickly and proved more fatal in liberal democracies than in countries with other regime types?

Either case fatality rates or deaths per population can be used to evaluate the Covid-19 death toll. I use case fatality rates because I want to know the number of casualties in any given country given the spread of the virus within its borders. Unless there is a natural rate at which the virus spreads, there is no reason to assume that all countries will turn out to have similar infection rates scaled to population. I again stress, the uncertainty associated with both the death and the case rates.

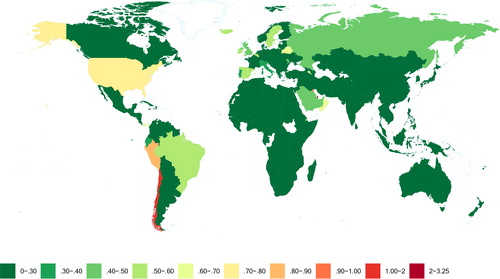

As can be seen in below, which maps the per capita number of cases, as of end June 2020, most countries show infection rates below 0.30% of the population. The 30 some countries with higher infection rates are a motley crew. Roughly half of them were liberal democracies, with the United States conspicuously amongst them. However, on balance liberal democracies do not have higher SARS-CoV-2 infection rates than do other regime types. If Covid-19 had spread more widely in liberal democracies than it had elsewhere, we would expect liberal democracies to have higher fatality rates than other countries. To boot, liberal democracies tend to have more expansive, higher quality health services.

Figure 1. COVID-19 cases per population by country (%), (3.2% = maximum total cases per total population).

Source: Author’s calculations based on CitationECDC (2020a) and CitationWDI (2020). Modified R code based on CitationLuginbuhl (2018).

Notes: White areas represent countries with no data.

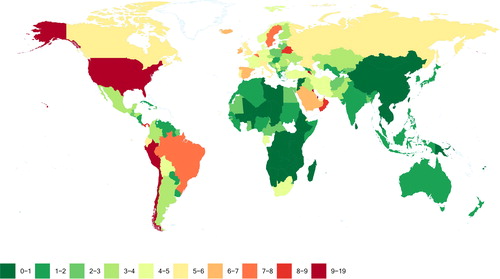

However, in the current phase of the pandemic the case fatality rate does appear to be higher in liberal democracies. maps the distribution of Covid-19 related deaths. It is worth noting that while using case fatality rates instead of deaths per capita under-emphasizes the extent of deaths in countries that perform more tests, the United States who performs a relatively large number of tests still has an exceedingly high case fatality ratio.

Figure 2. COVID-19 deaths per cases by country (%), (19 = maximum total deaths per total cases).

Source: Author’s calculations based on CitationECDC (2020a). Modified R code based on CitationLuginbuhl (2018).

Notes: White areas represent countries with no data.

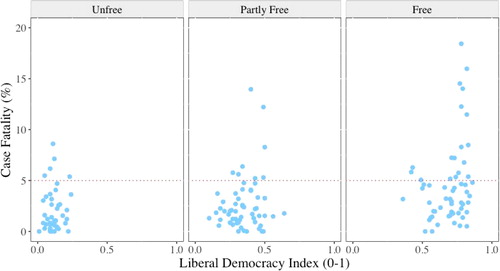

As of late June, the majority of countries with fatality rates above 5 percent are labelled ‘free’ by Freedom House (Citation2020). Based on Freedom House’s taxonomy, associates countries’ case fatality rate with freedom levels. Freedom House’s global freedom score contrasts ‘free’ countries with countries which are either ‘partly free’ or ‘not free’ – labelled unfree in the graph. The global score encompasses both political rights and civil liberties and therefore serves as a composite proxy for liberal democracy. According to this measure, a liberal democracy protects citizens’ political rights, property rights and civil rights. While the global freedom score mostly corresponds with what counts as a liberal democracy, some exceptions exist. For example, Monaco is a constitutional monarchy and not a liberal democracy, yet Monaco is characterized as ‘free’ according to the global freedom score. In order to evaluate the degree of liberal democracy, I also use the continuous measure of the liberal democracy score provided by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute (Coppedge et al Citation2020). The liberal democracy score is measured on the x-axis.

Figure 3. Case fatality rates and freedom level.

Source: Author’s calculations based on CitationECDC (2020a), WDI (CitationWDI 2020) and Freedom House (FreedomHouse 2020), and V-Dem (CitationCoppedge et al 2020).

Notes: A horizontal dotted line is placed at a case fatality rate of 5 percent. The facets are based on Freedom House types and the x-axis is based on the degree of liberal democracy according to the continuous V-Dem variable, v2x_libdem.

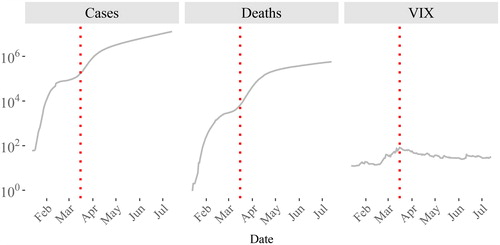

Figure 4. Global Cases, Deaths and the VIX Volatility Index, 13 January 2020 – 13 July 2020 (log scale).

Source: Author’s calculations based on CitationECDC (2020b), CitationGFD (2020).

Notes: The dotted line is placed at the 6-month high of the VIX index on March 16, 2020 as well as in the facet for cases and deaths.

illustrates the liberal curse posed by Covid-19. Adopting the global freedom score used by Freedom House to classify countries (into ‘free’, ‘partly free’ or ‘unfree’), the ‘case fatality rate’ appears to be particularly high in liberal societies. As can be seen, the case fatality rate increases with freedom ratings and as we move towards more ‘free’ regimes on the X-axis.

While the figure is illustrative, it is insufficient for making inferences. A disaggregated view of how the case fatality rate compares to different components of liberal democracy is offered in , while relates the case fatality rate to globalization. The Tables compare the different means across the different measures of liberal democracy using a series of t-tests, while accounting for the fact that the means are drawn from different samples with unequal variances.

Table 1. Sample statistics using t-test for mean comparison of cases per capita Method: Two-sample t-test, independent samples, unequal variance.

Table 2. Sample statistics using t-test for mean comparison of case fatality rate Method: Two-sample t-test, independent samples, unequal variance.

Table 3. Sample statistics using t-test for mean comparison, openness Method: Two-sample t-test, independent samples, unequal variance.

The first measure (‘liberal democracy’) isolates the ‘liberal’ aspect, which it takes to mean, ‘protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority… constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that, together, limit the exercise of executive power.’ Electoral democracy is defined as constituting ‘electoral competition for the electorate’s approval … when suffrage is extensive; political and civil society organizations can operate freely; elections are clean and not marred by fraud or systematic irregularities; and elections affect the composition of the chief executive of the country … freedom of expression and an independent media…’ (Coppedge et al Citation2020, 38). Egalitarian democracy gauges to what extent ‘rights and freedoms of individuals are protected equally across all social groups; … resources are distributed equally across all social groups; … groups and individuals enjoy equal access to power (Coppedge et al Citation2020, 40).’ Freedom of expression is captured by ‘… press and media freedom, the freedom of ordinary people to discuss political matters at home and in the public sphere, as well as the freedom of academic and cultural expression’ (Coppedge et al Citation2020, 41). Footnote2 Freedom of deliberation is understood as the ‘extent to which political elites give public justifications for their positions on matters of public policy, justify their positions in terms of the public good, acknowledge and respect counter-arguments; and how wide the range of consultation is at elite levels’ (Coppedge et al Citation2020, 47). Freedom of mobility is ‘… the extent to which citizens are able to travel freely to and from the country and to emigrate without being subject to restrictions by public authorities’ (Coppedge et al Citation2020, 158). Health equality measures to what degree ‘high quality basic healthcare [is] guaranteed to all, sufficient to enable them to exercise their basic political rights as adult citizens’ (Coppedge et al Citation2020, 186).Footnote3

As can be seen in , liberal democracies do not have higher cases per capita than other regime types according to any of the measures which could be used to characterize liberal democracy. However, shows that liberal democracies have a higher case fatality rate than other regime types.

From , we also see that another measure of openness, the extent of international arrivals in a country, correlates with higher per capita cases (though not with higher case fatality rates).

While and strongly support the liberal curse argument, it is of course possible that the higher death rate simply reflects differences in reporting, with liberal democracies more likely to report Covid-19 deaths than other regime types. I discussed this possibility early on in the paper, while expressing some doubts as to whether the statistics are biased in this way. Yet if we consider the possibility that liberal democracies have been harder hit than other regime types, it behooves us to consider some of the reasons for the liberal curse.

One reason for the higher case fatality rate in liberal democracies may be because liberal democracies are more open than other regime types. People residing in open, internationally integrated societies face a higher risk of exposure to domestic and foreign carriers of the virus, making such societies more susceptible to viral diffusion. As shown in , countries characterized as liberal democracies as a result of higher border openness have higher case fatality rates than countries with low border openness. also indicates that a high degree of incoming air traffic, either as a result of returning residents or visits by foreigners, is associated with higher fatality rates.

One might also make the case that lockdowns are harder to implement, and certainly harder to sustain, in liberal democracies. This would apply, in particular, to countries where individual rights are protected, including ‘rights’ undergirding the market economy, as in the ‘liberal democracy’ measure. Earlier I noted how reporting of cases and particularly deaths may be more accurate in electoral democracies because leaders can be punished for inaccurate reporting in upcoming elections. Countries operating under electoral democracy may also face greater pressure to lift lockdowns due to their detrimental effect on the economy, everyday life and morale, precisely because they may otherwise be punished in elections. It is also harder to lock down countries where independent thought and expression is valued, as one would expect to be the case in countries with high degrees of freedom of expression and deliberation. Why egalitarian societies have higher case fatalities is not entirely clear. Overall one would expect information to flow more freely within liberal democracies. Some of the information circulating during the first phase of the outbreak may however have been counter-productive. Early access to information regarding the different risks of Covid-19 across age groups may for instance have caused younger people to believe they were less likely than adults to develop Covid-19. Beyond isolating themselves from older family members, observing social distancing advice may therefore have seemed less urgent for them.

Another reason for the high case fatality rate in liberal democracies may be because such societies have a higher share of at-risk persons than other regime types. For example, liberal democracies are often said to have a high age structure in contrast with the “youth bulge” in other regime types. Social mores may exacerbate the unfavorable aspects of such demographics if the elderly are placed in nursing homes where the disease can easily spread. Of course, in order for the elderly to be better off as a result of being looked after at home, they must not be exposed to socially promiscuous family members. Liberal democracies may also have a higher share of individuals with other kinds of underlying conditions—such as cancer, diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, asthma, smoking—which place them at high risk. Indeed, one study found high blood pressure to be the most common pre-existing health condition, and obesity to be a high risk factor (Gold et al Citation2020). Some lifestyle choices—such as lack of physical activity and stress are likely higher in liberal democracies, possibly high alcohol consumption as well—and may explain the higher case fatality rate. Of course this is an empirical question worth of further investigation.

The COVID-19 threat to liberal international order

The liberal international order is vulnerable to Covid-19 in the sense that its signal feature is political and economic openness while the pandemic requires a degree of closure. According to John Ikenberry, the liberal international order is an ‘open and loosely rule based’ system, providing ‘a foundation in which states can engage in reciprocity and institutionalised cooperation’ and is compatible with different levels of hierarchical differentiation (Ikenberry Citation2011, 18–22). Threats to the LIO appeared before the pandemic. Scholars working on the LIO have however tended to see pre-pandemic crises as a crisis of authority (Ikenberry Citation2015), liberal order (Duncombe and Dunne Citation2018; Walt Citation2018; Mearsheimer Citation2019), inclusion (Acharya Citation2014; Nye Citation2017) and inequality (Norrlöf Citation2018) rather than the inevitable failure of liberal international order itself. Below, I first discuss the Covid-19 impact on political freedoms before turning to its impact on economic freedoms.

Covid-19 and political freedoms

Attempts to manage the Covid-19 crisis undermine political freedoms. Many liberal democracies have taken unprecedent actions to contain the virus. The imposition of border closures on non-nationals and non-residents cuts against the relatively open borders promoted by the liberal international order.

Most advanced liberal democracies have shared an open-door policy and have had relatively open borders towards political refugees despite the hardening climate in recent years. The strategic linking of the virus with China further shakes the non-discriminatory tenets of the liberal international order. Many Asians have reported racist incidents and attempts to associate them with the virus based on their ethnicity. References to the ‘Chinese virus’, the ‘Wuhan virus’, and the ‘foreign virus’ by President Trump and other parts of his administration have fueled Asian stigmatization in the US, adding to the growing rift between Washington and G7 allies.

Border closures have been implemented in many countries quite regardless of regime type. Backsliding on free movement is, however, particularly detrimental to liberal democracies. Although many continue to restrict immigration, free movement is practiced in the liberal democracies of the more advanced economies. Human mobility is, for example, entirely free within Western Europe’s Schengen area. And liberal democracies qualify for the United States’ visa waiver program, ESTA. Since the pandemic’s onset liberal democracies have however restricted free movement within the Schengen area and towards liberal democracies outside the Schengen area. Mobility has also been circumscribed between the United States and liberal democracies. The pandemic has also been used by the United States, not just a liberal democracy but a pivotal actor in the LIO, to backslide on legal immigration. An immigration proclamation expressing concerns about ‘the impact of foreign workers on the United States labor market’ initially suspended immigration visas for two months, and has now been prolonged until the end of the year (Trump Citation2020a, Citation2020b). What is striking about these measures is that they are not aimed at securing public health for Americans but rather at addressing the effects of the pandemic by reinforcing the 2017 National Security Strategy, which sought to reboot US grand strategy by casting ‘economic prosperity as a pillar of national security’ (Trump Citation2017). Furthermore, on 6 July, Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced that foreign students at universities offering online courses would be deported if they did not enrol in a university programme offering in-person courses. However, following lawsuits filed by Harvard University and MIT, the government rescinded its decision on 14 July. These measures, which double down on the Trump administration’s aversion to the free movement dimension of the LIO, are worrisome. While immigration is certainly not the strongest dimension of the LIO, free movement amongst the liberal democracies of the advanced economies has been one of its cornerstones.

Finally, one might add, as in the fight against terrorism, surveillance techniques are being used to tackle the pandemic, putting the freedom to privacy in the balance. China, for example, relied on biometric surveillance to combat the spread of the virus. Using artificial intelligence-enabled body temperature detection and facial recognition cameras allows them to track and restrict the free movement of people infected with SARS-CoV-2. Monitoring smartphones through digital contact-tracing applications, China along with Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan have also sought to identify the connections of Covid-19 carriers in order to trace and eventually interrupt the transmission of the disease. China’s privacy violations are not new, nor have liberal democracies shied away from using surveillance techniques in the past. However, SARS-CoV-2 track and trace technologies have been implemented in liberal democracies. In this sense, the pandemic risks performatively legitimizing Beijing’s authoritarian model, to the detriment of the LIO.

Covid-19 and economic freedoms

Both coordinated and uncoordinated actions to cope with the Covid-19 outbreak put economic freedoms at risk as a result of declining economic activity and the potential for ‘economic security’ policies consistent with economic nationalism. Economic security refers to international threats to a nation’s economic welfare. The pursuit of economic security involves an attempt to maximize state autonomy and to minimize the dependence and impact of the international economy on the domestic economy, even though such policies may be less economically efficient (Knorr and Trager Citation1977). Already by the 1990s, a consensus had emerged about the opportunities associated with accepting risk and uncertainty under conditions of economic interdependence and the costs associated with self-sufficiency and abstaining from economic integration (Cable Citation1995).

shows the logarithmic growth in the total number of Covid-19 cases, deaths and in the VIX index which measures market volatility. The VIX index is known as the ‘fear’ index since fear drives volatility while confidence generates less volatility. The VIX index hit a 6-month pandemic high in mid-March 2020 (dotted red line) following the precipitous increase in global cases and deaths. Adding to the calamity, equity markets collapsed as the VIX index climbed. Unemployment rates around the world have also spiked and world trade is expected to contract in 2020 (Azevêdo Citation2020). President Trump is further fanning the flames of a trade war or a dollar war with China, contemplating some form of economic retaliation for purported evidence the virus originated in a Chinese lab (Davidson and Borger Citation2020; Mason, Spetalnick, and Pamuk Citation2020). The administration’s allegations, however, contradict the statement made by the director of US national intelligence that the virus was ‘not manmade or genetically modified’ (Hosenball Citation2020). A protracted health crisis could further shake economic confidence by putting downward pressure on household incomes and savings, further reducing demand and generating more layoffs. These circumstances present ripe conditions for a debt-for-equity trap with especially devastating consequences for household financing of property acquisition via short-term rentals, equity returns and dividends. Apart from hoarding, much economic activity came to a standstill as the pandemic began snowballing in the spring of 2020. Panic-purchases, particularly of food and household items, became a real problem. The pandemic has forced a conversation about the merits of reducing supply chain dependencies by decoupling with China. The expert community sees the Trump administration as attempting to do just that by banning TikTok and WeChat in the US. The ban is considered an attempt to make US companies realize the political risks of doing business in China, and to deter Chinese technology firms from investing in the US (Gertz Citation2020; Palmer Citation2020). Pointing to the high costs of decoupling, Shannon K. O’Neil writes, “dismantling international supply chains will make U.S. businesses less competitive and will blunt their global technological edge”.Footnote4

In the future, breaks in global supply chains involving both Asia and hard-hit countries in Europe and North America may lead to calls for greater emphasis on economic security policies. With its emphasis on self-sufficiency and protectionist impulses, a policy of economic security represents a form of economic nationalism which is incompatible with the liberal international order, long-term prosperity and security. These trends were already visible in the Trump administration’s priorities before Covid-19. Threats to economic security were highlighted as an important dimension of President Trump’s ‘America-First’ policy. Emphasizing self-sufficiency and protectionist responses to declining competitiveness and job loss, the attempt to bring back economic security policies breaks with previous grand strategies organized around liberal hegemony.

However, preserving liberal international order by keeping economic nationalism in check does not mean a rejection of ‘embedded liberalism’ (Ruggie Citation1982). Indeed, making liberal economic policies compatible with domestic intervention to promote social goals is compatible with liberal international order. To mitigate the hazardous long-term effects of Covid-19 on liberal international order, governments should renew their commitment to core liberal principles, reducing social and economic inequities including access to quality healthcare. The spectre of broader economic security policies cannot be ruled out if international threats to global supply chains and economic welfare continue to mount, either through a prolonged second wave or long-term effects of the first wave.

At the systemic level, the most coveted order of most liberal democracies—the liberal international order—may be adversely affected by Covid-19 if the crisis deepens and becomes more protracted.

Conclusion

The spread of Covid-19 is the most serious global crisis in the postwar era and threatens to upend all facets of everyday life. Using two-sample t-tests for mean comparisons of the case fatality rate across different measures of liberal democracy and other forms of openness, I demonstrate that liberal democracies have higher case fatality rates than other regime types. I also offer some plausible explanations for why this might be the case, while exercising caution in drawing strong conclusions given the data biases emphasized throughout the paper.

In addition to wreaking havoc within liberal democracies, the spread of the virus also imperils the liberal international order in which liberal democracies participate. The health crisis complicates the implementation of policies consistent with liberal international order. In order to meet the crisis, liberal democracies have curtailed both political and economic freedoms. Border closures, discrimination and restrictions on the right to privacy cut against political freedoms. As international threats to global supply chains, employment and economic welfare gather, economic security policies emphasizing self-sufficiency with protectionist impulses may crowd out policies consistent with the liberal international order, jeopardizing long-term prosperity. If global economic interdependence unwinds, we must also expect gathering security risks as the international economy becomes less sensitive to insecurity and the economic constraints on war recede (Gartzke and Westerwinter Citation2016). Covid-19 re-invites old questions regarding the resilience of the liberal international order in the face of global shocks and prospects for the liberal international order to survive in a rudderless world.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carla Norrlöf

Carla Norrlöf is Visiting Research Professor at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (Helsinki), Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto, Senior Fellow of Massey College and a Research Associate of the Graduate Institute of International Studies (Geneva). She researches International Relations (IR) and International Political Economy (IPE) with a special focus on great powers and liberal international order. Email: [email protected], [email protected]

Notes

1 An infection transmitted from an animal to a human host.

2 This variable gauges freedom of expression and alternative sources of information.

3 Differently from our other Liberal Democracy indicators, freedom of deliberation and freedom of mobility are measured on a -3 to 3 point scale.

4 Shannon K. O’Neil. 1 April 2020. “How to pandemic-proof globalization.” Foreign Affairs: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2020-04-01/how-pandemic-proof-globalization (accessed 17/08/20).

References

- Acharya, Amitav (2014) The end of american world order (Cambridge: Polity)

- Alon, Ilan and Shaomin Li (2020) COVID-19 Response: Democracies v. Authoritarians (Alexandria: The American Spectator)

- Andersen, Kristian G, Andrew Rambaut, Wian Lipkin, Edward C Holmes, and Robert F Garry (2020) ‘The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2’, Nature Medicine, 26:4, 450–2

- Azevêdo, Roberto (2020) Press release: Trade set to plunge as COVID-19 pandemic upends global economy (Geneva: World Trade Organization)

- Brands, Hal (2020) ‘Coronavirus is China's chance to weaken the liberal order’, (New York: Bloomberg)

- Cable, V incent (1995) ‘What is international economic security?’, International Affairs, 71:2, 305–24

- CDC (2020, July 30) People with certain medical conditions (Washington D.C.: Center for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I Lindberg, J an Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard et al. (2020) V-Dem Dataset v10. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project

- Davidson, Maanvi Singh Hele and Julian Borger (2020) ‘Trump claims to have evidence coronavirus started in Chinese lab but offers no details,’ The Guardian

- Day, M ichael (2020) ‘Covid-19: four fifths of cases are asymptomatic, China figures indicate’, BMJ (Clinical Research ed.).), 369, m1375

- Deudney, Daniel, and G. John Ikenberry (2009) ‘The myth of the autocratic revival: why liberal democracy will prevail.’ In Foreign affairs January/February

- Duncombe, Constance, and Tim Dunne (2018) ‘After liberal world order’, International Affairs, 94:1, 25–42

- ECDC (2020a) COVID-19-geographic-disbtribution-worldwide-2020-06-24 (Solna: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control)

- ECDC (2020b) COVID-19-geographic-disbtribution-worldwide-2020-07-14 (Solna: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control)

- Freedom House (2020) Global freedom scores (Washington, D.C.: Freedom House)

- Gartzke, Erik, and Oliver Westerwinter (2016) ‘The complex structure of commercial peace: contrasting trade interdependence, asymmetry, and multipolarity’, Journal of Peace Research, 53:3, 325–43

- Gat, Azar (2007) ‘The return of authoritarian great powers’, Foreign Affairs, 86:4, 59–69

- Gertz, Geoffrey (2020) ‘Why is the Trump administration banning TikTok and WeChat?’ In Up front (Washington DC: Brookings)

- GFD (2020) Global financial data (San Juan Capistrano, CA: Global Financial Data)

- Gold, Jeremy A W, Karen K Wong, Christine M Szablewski, Priti R Patel, J ohn Rossow, J uliana da Silva, P avithra Natarajan et al. (2020) ‘Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 — Georgia, March 2020’, MMWR, 69, 545–50

- Hosenball, Mark (2020) Coronavirus was 'not manmade or genetically modified': U.S. Spy Agency (London Reuters)

- Ikenberry, G. John (2011) Liberal leviathan: the origins, crisis, and transformation of the American world order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press)

- Ikenberry, G John (2015) ‘The Future of Liberal World Order’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 16:3, 450–5

- Kagan, Robert (2019) ‘Authoritarian advantage: The struggle for a liberal world order is occuring not just outside the West but also within it,’ The German Times. Berlin

- Knorr, Klaus Eugen and Frank N Trager (1977) Economic issues and national security (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas)

- Leung, Nancy H L, Daniel K W Chu, Eunice Y C Shiu, K wok-H ung Chan, James J McDevitt, Benien J P Hau, H ui-L ing Yen et al. (2020) ‘Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks’, Nature Medicine 26: 676-680

- Luginbuhl, F elix (2018) "Reproducing The Economist Most Popular Map of 2017." In.

- Mason, Jeff, Matt Spetalnick and Humeyra Pamuk (2020) ‘Trump threatens new tariffs on China in retaliation for coronavirus,’ Reuters, London

- Mearsheimer, John J (2019) ‘Bound to fail: the rise and fall of the liberal international order’, International Security, 43:4, 7–50

- Norrlöf, C arla (2018) ‘Hegemony and inequality’, International Affairs, 94:1, 63–88

- Norrlöf, Carla (2020) ‘Covid-19 and the liberal international order: Exposing instabilities and weaknesses in an open international system’, Helsinki: FIIA 11: 1-2

- Nye, Joseph S (January/February, 2017) ‘Will the liberal order survive? The history of an idea’, Foreign Affairs, 96:1

- Palmer, James (2020) "Why is the United States effectively banning WeChat and TikTok?" In Foreign policy. Washington DC

- Ruggie, John Gerard (1982) ‘International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Postwar Economic Order’, International Organization, 36 :2, 379–415

- Trofimov, Yaroslav (2020) ‘Democracy, dictatorship, disease: the west takes its turn with coronavirus’, Wall Street Journal, New York

- Trump, Donald J (2017) ‘The national security strategy of the United States of America’, 1–31 (Washington D.C.: The White House)

- Trump, Donald J (2020a) ‘President Donald J. trump is honoring his commitment to protect american workers by temporarily pausing immigration’, Washington D.C.: The White House

- Trump, Donald J (2020b) ‘Proclamation suspending entry of aliens who present a risk to the U.S. labor market following the coronavirus outbreak’, Washington D.C.: The White House

- UNWTO (2020). Tourism statistics (Madrid, Spain: World Tourism Organization)

- Verity, Robert, Lucy C Okell, Ilaria Dorigatti, Peter Winskill, Charles Whittaker, Natsuko Imai, Gina Cuomo-Dannenburg, Hayley Thompson, Patrick G T Walker et al. (2020) ‘Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis’, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20:6, 669–77

- Walt, Stephen M (2018) The hell of good intentions: America's foreign policy elite and the decline of U.S. Primacy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

- WDI (2020). World Development Indicators: Population, total (Washington, DC: The World Bank)

- Wu, Joseph T, Kathy Leung, Mary Bushman, Nishant Kishore, R ene Niehus, Pablo M de Salazar, Benjamin J Cowling, M arc Lipsitch, and Gabriel M Leung (2020) ‘Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China’, Nature Medicine, 26:4, 506–10

- Zhao, Jiao, Yan Yang, Hanping Huang, Dong Li, Dongfeng Gu, Xiangfeng Lu, Zheng Zhang et al. (2020) ‘Relationship between the ABO Blood Group and the COVID-19 Susceptibility’, medRxiv, 2020.03.11.20031096