?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We know surprisingly little about the impact of democratic decline in the EU on foreign policy and on democracy promotion efforts in particular. We examine qualitative and quantitative changes in aid allocation for democracy promotion alongside declining levels of democracy in the EU and its members. Focusing on decision-makers’ perspectives, we explain these changes with strategic and constructivist approaches. We analyse multilateral and bilateral aid flows from the EU and its members to Central Asia with data from OECD and IATI from 2000 to 2018. We identify quantitative changes in aid promoting democracy in Central Asia, which can be partially attributed to the donors’ increasing challenges for democracy at home. While the overall aid levels remained stable, we also identify qualitative shifts in allocation patterns favouring government institutions rather than civil society organisations. Our findings address the impact of democratic decline on foreign policy towards non-democratic states outside the European neighbourhood.

1. Introduction

In their 2020 reports, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project and Freedom House agree that ‘Hungary is no longer a democracy, leaving the EU with its first non-democratic Member State’ (Lührmann et al. 2020, 4). While other EU member states have not lost their status as democracies (yet), we observe declining levels of democracy in Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania (Lührmann et al. Citation2020). Intrigued by these developments, we explore the impact of democratic decline in the EU and its member states on their efforts to promote democracy in Central Asia.

Research on the allocation of aid for promoting democracy points to the relevance of the donor’s own model and level of democracy.Footnote1 However, the question remains understudied whether changes in the donor country’s domestic polity lead to differential impacts of aid allocation across specific sectors and recipients. Although we agree that democratic decline in the donor country tends to correlate with a realignment of policy preferences, we expect that this shift is not necessarily characterized by a decrease of aid as such. Rather than leading to an overall decrease of aid, we show that democratic decline leads to a decrease of aid in sectors associated specifically with democracy promotion and civil society organizations (CSO) as recipients.

Adopting the perspective of decision-makers in the aid sending country, we present two approaches explaining the relationship between democratic decline at home and aid allocation for democracy promotion abroad: a strategic perspective of decision-makers (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2009) and a constructivist perspective on democratic identity (Knodt and Jünemann Citation2007; Huber Citation2015). Based on these approaches, we theorise that as democracy declines, leaders are less bound to democracy as a principle of politics, including its promotion abroad. Our study addresses immediate effects of the recent decline in levels of democracy, which so far does not amount to a substantive threat to democracy as a regime type and governance model. We expect that if donors experience such democratic decline, less foreign aid will be allocated to promote democracy relative to other forms of foreign aid. With respect to aid recipients, donors should prioritise government institutions rather than CSOs. Aid allocated to government institutions enables donors to retain more control and enjoy additional benefits, such as support from the aid recipient in international organisations.

We analyse how the EU’s and its members’ declining levels of democracy affected aid allocation to Central Asia. The region represents a particularly fitting case to test our argument. Central Asia exemplifies the discussion over the allocation of aid for democracy promotion as the EU’s rather limited goals regarding good governance and civil society promotion have not been attained (Kluczewska and Dzhuraev Citation2020; Omelicheva Citation2015; Warkotsch Citation2010). The countries range from electoral democracy to closed autocracy in our investigation period (Lührmann et al. Citation2020), representing the entire spectrum of not fully democratic regime types. They represent the broad variety of cases for EU democracy promotion programs, which allows us to examine the impact of shifting patterns of EU aid allocation. After being off Western countries’ radar in the early stages of independence before the 2000s,Footnote2 the Central Asian states opened a space for non-governmental actors and international aid organisations (Hönig Citation2020). The region has since received substantive foreign support for democracy promotion, focusing on promoting good governance practices through state institutions rather than bottom-up democracy (Warkotsch Citation2010; Youngs Citation2010).

We address quantitative changes in the share of aid allocated for democracy promotion and qualitative changes regarding the type of aid recipient. We disaggregate multilateral and bilateral aid flows from the EU and its members to the five Central Asian states (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) between 2000 and 2018 with novel information by augmenting data from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) and the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). We extend existing theories and test them in a large-N study. Our approach complements assessments from expert interviews or policy documents that only address plans, not necessarily actual aid allocation (Wolff and Wurm Citation2011, 90). We provide insight into qualitative shifts in aid and recipient type occurring alongside democratic decline, even as overall aid levels may remain stable.

Our study examines the allocation of individual aid activities rather than aggregated monetary aid flows. Whether the allocation of aid activities allows projects and events to take place at all is more critical for aid recipients’ organisational survival and goal attainment than changes in the allocated budgets. This is also the case for democracy promotion as an overarching societal goal. While recipients can still benefit from the reputation, international visibility, networks and expertise of their donors during budget cuts, they lose access to these critical opportunities when aid is not allocated. Initiating new interactions with donors is uncertain and costly for aid recipients. Therefore, we address the more consequential question of whether aid activities are allocated or not rather than their volume.

Our research contributes to the broader literature on the impact of democratic decline on foreign policy. Central Asia is only one among many regions worldwide that are not direct neighbours of the EU, exhibit low levels of democracy and display a limited success of the EU’s democracy promotion efforts. The five Central Asian states are—as many other non-democratic states worldwide—not dependent on the EU and its member states and do not hold the special status of inclusion in the European Neighbourhood Policy (Jünemann and Knodt Citation2007; Spaiser Citation2018).Footnote3 Our study fosters understanding the EU and its members’ democracy promotion efforts in these countries. We contribute to explaining the role of domestic developments in donor states in international relations and democracy promotion in such non-democratic states (Knodt and Jünemann Citation2007).

The relationships between Central Asia, the EU and EU member states became even more focused on promoting democracy during the negotiations leading to the signing of the first Enhanced Partnership Agreement between the EU and Central Asia in the early 2000s, which led to a strategy for a new partnership in 2007 (EU Citation2019). Key focus areas were political and economic cooperation in spheres such as good governance, rule of law, human rights, democratisation and training, where the EU was willing to share its expertise. Researchers as well as policymakers believed that the EU could provide an alternative to the autocratic influences of Russia and China (Boonstra and Panella Citation2018). While the EU’s commitment has been frequently questioned, it has focused on promoting good governance practices through state institutions rather than CSOs (Warkotsch Citation2010; Youngs Citation2010). The EU’s 2019 Strategy on Central Asia introduced a balancing approach integrating democracy promotion with economic and geo-strategic interests (Cornell and Starr Citation2019). This shows the EU’s ongoing support for democracy promotion despite Central Asia’s lack of substantive progress.

Understanding political developments in the donor states can help us to understand variation in their allocation of aid. Recently, a decline in democracy has been diagnosed in various member states, especially the Visegrad Four countries (Lührmann et al. Citation2020). Through the member states’ involvement in EU institutions, this also affects the EU as a whole. Such a decline stands in stark contrast to the EU’s democratic identity. Analysing the impact of this decline on the allocation of aid for democracy promotion uncovers how challenges to the donor’s governance model may affect the substance of the aid provided beyond the EU’s rhetoric, which is driven by democratic values (Jünemann and Knodt Citation2007).

In the following sections, we define our key concepts and present our theoretical framework based on insights from research on aid allocation and democracy promotion. We apply strategic and constructivist approaches to explain how democratic decline at home may affect the allocation of aid for the promotion of democracy abroad. Identifying and controlling for alternative explanations, we investigate the independent short-term effects of democratic decline in the EU and its member states on democracy promotion activities in Central Asia. We focus on changes in the allocation of aid for democracy promotion as compared to aid for other purposes (including education, health or economic development), and the type of recipient, whether government institutions or CSOs. To explain these changes, we provide disaggregated information on aid allocation in Central Asia. Our analysis takes various characteristics of both the providing and receiving countries into account. We contribute to the ongoing debate on the potential of democracy promotion and its effectiveness by adding new insights, focused on donors’ own (non-)democratic developments.

2. Conceptualising democratic decline, foreign aid and democracy promotion

2.1. Democratic decline

There are different understandings of what democratic decline entails. Democratic declineFootnote4 refers to the gradual worsening of the democratic conditions in a country and the move from democratic to increasingly autocratic values and practices. According to Waldner and Lust (Citation2018, 95), this process ‘makes elections less competitive without entirely undermining the electoral mechanism; it restricts participation without explicitly abolishing norms of universal franchise seen as constitutive of contemporary democracy, and it loosens constraints of accountability by eroding norms of answerability and punishment’. Thus, we refer to democratic decline as a worsening of democracy over time without resulting in complete breakdown.Footnote5 While the terms democratic decline and populism are sometimes used interchangeably, they are not the same (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2012). In this article, we focus on the effects of democratic decline independently from the rise of populism. While populism may at times threaten democracy (Rummens Citation2017; Diamond Citation2017), according to Diamond, ‘there are times in the history of a democracy when a certain dose or impulse of populism can have a tonic effect in promoting needed economic and institutional reforms that break up monopolies, redistribute power and income, attenuate injustices and invite new grassroots forms and sources of political participation that are not inconsistent with liberal democracy and may actually invigorate it’ (Diamond Citation2017, n.p.). Thus, it is imperative to treat the rise of populism and democratic decline separately, both analytically and empirically.

2.2. Democracy promotion through foreign aid

Not all foreign aid is issued for democracy promotion and democracy can be promoted by means other than foreign aid. Foreign aid serves different purposes and has been at the heart of international relations since the end of World War II (Bueno de Mesquita Citation2009). It is defined as ‘the international transfer of capital, goods, or services from a country or international organisation for the benefit of the recipient country or its population’ (Williams Citation2020, n.p.).

In this paper, we focus on official multilateral aid from the EU and bilateral aid from its member states allocated to the five Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. While the EU and its member states are active in a number of issue areas in that region,Footnote6 the promotion of democracy has become an important part of foreign aid and is provided by governmental and non-governmental organisations (Resnick Citation2018; Carothers Citation2009).Footnote7 Examples include election monitoring, strengthening institutions, judiciaries and legislature as well as support for civil society. Unlike development aid, which aims at improving the socio-economic conditions of the country, aid for democracy promotion is often provided to governments and CSOs (Carothers Citation2009). There may be an overlap between aid for democracy promotion and development, as aid in general may contribute to democratisation via three mechanisms: ‘(1) through technical assistance focusing on electoral processes, the strengthening of legislatures and judiciaries as checks on executive power, and the promotion of civil society organisations, including a free press; (2) through conditionality; and (3) by improving education and increasing per capita incomes, which research shows are conducive to democratisation’ (Knack Citation2004, 251). While we acknowledge these potential effects of enhancing democracy through all types of aid, we rely on the donor’s own intention and identification of aid as assistance aimed at promoting democracy, benefitting, for example, government and civil society. The EU has been fostering democratic developments abroad through different institutionalised means, including the accession process and the European Neighbourhood Policy as well as incorporating democratic principles in contracts with third countries and multilateral forums (Fawn Citation2020; Huber Citation2015).

How can we define democracy promotion? Broad definitions of democracy promotion include aid projects as well as ‘diplomatic incentives and conditionality; the dynamics of pro-democratic socialization; and the general pursuit of political dialogue and pressure within cooperative security partnerships’ (Youngs Citation2010, 3). In this paper, we focus on foreign aid allocation for democracy promotion from the EU and its members, including democracy assistance from the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR). The EU’s democracy promotion efforts can be allocated through bilateral and multilateral aid. Multilateral aid is composed by contributions of the EU member states and the European Commission distributes it on the behalf of its members. Schneider and Tobin (Citation2013) stress that the individual preferences of each member play an important role in decision-making on aid allocation. Members may impact the EU’s aid allocation individually or within coalitions based on their foreign policy goals. Therefore, the member states have a significant influence on bilateral and multilateral aid for democracy promotion.

We examine changes in both the quantity and quality of aid provided for democracy promotion. Studying the quantity of aid, we investigate changes in the proportion of projects allocated for democracy promotion. We address the quality of aid as the choice of recipient, government institution or CSO, leads to substantive differences in promoting democracy (Hahn-Fuhr and Worschech Citation2014). CSOs foster grassroots democratic developments and are often associated with a bottom-up development of democratic institutions. If aid is allocated to government institutions, democracy is promoted top-down within the existing institutional framework. This allows us to study the ‘implementation priorities pursued by the external actor’ (Wetzel, Orbie, and Bossuyt Citation2015, 22) if the donor faces democratic decline at home.

3. Understanding aid allocation for democracy promotion

How does democratic decline within donor countries impact the allocation of aid for democracy promotion? And does democratic decline in the donor countries impact the preferences of recipients, allocating more aid to governments or CSOs? The literature addressing the first question is surprisingly scarce. While the impact of democratic decline in the EU and its member states is often discussed with a focus on domestic politics (see for example Waldner and Lust Citation2018; Meyerrose Citation2020; Marsh and Miller Citation2012), only a few publications focus on its impact on the international level (Hyde Citation2020; Rüland Citation2021).Footnote8 Most approaches studying the impact of democratic decline on foreign policy address moments of crisis, such as security problems, conflict and migration (Wallander Citation2018). The EU’s everyday foreign policy, including development aid and democracy promotion, has received limited scholarly attention. This topic has only been addressed from the perspective of a change of government in an EU member state (Jünemann and Knodt Citation2007). While we may expect that a change in political orientation could disrupt the so-called ‘coordination reflex, common definitions of problems and common solutions to the problems’ (Jünemann and Knodt 2007, 356) at the EU level, this effect has not been empirically studied.

Our theory expands on existing approaches to understand democracy promotion in light of international relations theories (Robinson Citation1996; Wolff and Wurm Citation2011; Wolff and Spanger Citation2017). Existing theories focus predominantly on broad conceptualizations of democracy promotion by democratic states. We do not study all efforts to promote democracy but focus on aid provisions and highlight the theoretical implications for democracy promotion under democratic decline in the donor state.

An important segment of the literature on aid allocation discusses the effects and effectiveness of aid (see for example Bourguignon and M. Sundberg 2007; Burnside and Dollar Citation2000; Hansen and Tarp Citation2000) and democracy promotion (see for example Grimm and Leininger Citation2012; van Doorn and von Meijenfeldt 2007) in general and in Central Asia in particular (Bossuyt Citation2018; Sharshenova Citation2018). We focus on the determinants of aid allocation (Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011). The literature on all forms of aid allocation points to the fact that donors take a multitude of factors into account (Alesina and Dollar Citation2000; Lehrer and Korhonen Citation2004). Thus, we present an overview, accounting for the characteristics of donors to understand the allocation of aid. We highlight studies focusing on the allocation of aid for democracy promotion and to specific recipients, including government institutions and CSOs.

From the perspective of the donor, the decision to allocate aid is determined by its own characteristics as well as the perceived characteristics of the recipient country. Regarding the characteristics of the donor, we know from the literature that aid allocation is considered to be a part of foreign policy (Palmer, Wohlander, and Morgan Citation2002). This is why factors that shape foreign policy have also been identified to affect the allocation of aid. Such factors include the composition of the government, its constituency or winning coalition (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007), a government’s ideological base and its position on the left-right scale (Greene and Licht Citation2018). For example, Christian or leftist parties have been identified as allocating more aid than other parties (Thérien and Noël Citation2000).

Other factors influencing aid as part of foreign policy are economic interests (such as resource access), geostrategic and security issues (Bader, Grävingholt, and Kästner Citation2010; Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007; Greene and Licht Citation2018; Petrova Citation2015) as well as external shocks (such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001) (Chin and Quadir Citation2012). Being part of a country’s overall foreign policy, aid is linked to its international power position. Consequently, aid is influenced by other means of foreign policy, which can be substituted or amended. For example, involvement in alliances can be relevant to aid allocation (Del Biondo Citation2015; Palmer, Wohlander, and Morgan Citation2002). Countries that are part of multilateral organisations often coordinate with other donors in multi- or bilateral aid programs (Lehrer and Korhonen 2004, 594). Overall, we observe that priorities that countries set in foreign policy, for example respect for human rights, can shape aid allocation patterns.

In their decision to allocate aid, governments also consider the characteristics of the recipient country, including the overall level of democratic development, the respect for human rights or the level of economic development and policies (Wittkopf Citation1973). Different mechanisms are at play: (1) characteristics of recipient countries can incentivise donors to reward countries with a positive record regarding democracy promotion or respect for human rights (Warkotsch Citation2008) or (2) they can provide incentives to target non-democratic states with leaders who can be incentivised to vote in the UN according to the donor’s preferences (Wittkopf Citation1973; Lai and Morey Citation2006). In addition, pre-existing connections between sender and recipient are crucial for aid allocation. For example, allocation is more likely when the recipient country is a former colony or shares other historical links (Carnegie and Marinov Citation2017; Alesina and Dollar Citation2000).

Domestic characteristics such as the level of corruption or democracy also have to be taken into account as some donors might be interested to address them or consider them a precondition to allocate any form of aid (Alesina and Dollar Citation2000). Factors such as respect for human rights or existing democratic development can also be utilised as conditions in allocating aid (Hoffmann Citation2010) but have not been implemented consistently (Poe Citation1992; Zanger Citation2000). Conditionality can be applied regarding policies the aid sender aims to see implemented in the recipient country or in the form of a deal regarding support for the donor’s policies in exchange for aid (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2009; Warkotsch Citation2008). The explanatory power of altruistic motives is rather limited and less relevant in democracy promotion compared to other forms such as humanitarian or disaster relief aid (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007). Countries that receive aid differ not only in their openness to international interactions but also their willingness to receive aid particularly for democracy promotion (Carothers Citation2006). Powerful states, such as Russia or China in the case of Central Asia, can also impact aid allocation (Babayan Citation2015). For example, China has been identified as capable of blocking democracy promotion by the EU and US (Chen and Kinzelbach Citation2015). In the following section, we discuss in detail how the allocation of aid for democracy promotion can be explained in relation to the democratic decline in the EU and its member states.

4. Theorising democratic decline and democracy promotion

What explains the allocation of aid for democracy promotion? To address this question, we focus on the donor’s perspective and study changes in domestic democracy levels. We expect that, as donors experience democratic decline, they allocate less foreign aid for democracy promotion. Regarding the allocation process of aid, donors experiencing democratic decline are likely to prioritise governments to other types of aid recipients. At the same time, CSOs are expected to receive less aid for democracy promotion compared to other types of recipients. Focusing on the viewpoint of decision-makers in the aid sending countries, we present two explanatory models for aid allocation during democratic decline in the donor countries (Wolff and Wurm Citation2011, 82): a strategic perspective of decision-makers (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007, Citation2009) and a constructivist perspective on democratic identity and roles (Knodt and Jünemann Citation2007; Huber Citation2015). Building on these frameworks, we provide insights into the relationship between democratic decline at home and aid allocation for democracy promotion abroad through bilateral and multilateral aid.

From a strategic perspective, we assume that decision-makers are elected officials who aim to stay in office and that the resources available to them are limited (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007). Resources may be allocated to various policy areas, including social welfare, security or infrastructure. In order to stay in office, decision-makers have to allocate limited resources efficiently to please their electorate and attract votes. The strategic perspective assumes that democracy promotion would not be pursued as it is not necessarily in the interest of leaders of democracies for other states to be democracies (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2009). From a foreign policy perspective, convincing a non-democratic country’s small ruling elite of a foreign policy goal is much easier than engaging with a large electorate in a democratic country. This is why political leaders are expected to favour working with non-democratic states in foreign policy, especially if they are less constrained by democratic principles in their own country.Footnote9 Furthermore, autocratic stability in aid receiving states can provide a favourable foreign policy environment. While democratic recipient countries might experience rapid shifts in winning coalitions, autocracies often provide for a more stable environment as local rulers as well as foreign policy makers cater to largely stable ruling elites (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007).

Still, the EU and its member states have set a normative expectation that democracy promotion is one of their fundamental principles (Holzhacker and Neuman Citation2019; Huber Citation2015). While democracy has been a priority in the EU and its member states in recent history, does the role of democracy promotion in foreign aid allocation change with the recent cases of democratic decline? Foreign policy, including aid allocation, is frequently perceived as an extension of domestic politics (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2009). Therefore, if there is a lower priority on democracy at home, decision-makers will likely assess promoting democracy abroad to be less rewarding and will not prioritise it. In cases where it was never a genuine priority, leaders might be happy to stop pretending that they support democracy abroad. Democratic decline at home allows leaders with limited interest in supporting democracy promotion to focus on other policies and types of foreign aid that they deem more promising. Under democratic decline, state institutions as well as decision-makers experience greater independence from the electorate. When democracy promotion comes with less added value at home, providing aid for democracy promotion is often not in the strategic interest of decision-makers.

Democratisation processes come with a high level of uncertainty and costs for adapting to a volatile and non-predictable process of change in the government structure of the recipients. As this process is usually accompanied by economic and geo-strategic changes, democratisation may not be preferable for decision-makers in the short run. This is even more relevant if decision-makers in the aid sending states do not expect to benefit from promoting democracy as one of the key principles of government. In contrast, other types of aid can create benefits at home. We observe that governments place priority on their country’s proclaimed self-interest compared to other countries’ development interests during periods of democratic decline (Kaufman and Haggard Citation2019). Due to their focus on self-interest, we assume that decision-makers will put a higher priority on aid types that yield immediate benefits.Footnote10 For example, food programmes can allow decision-makers in donor states to buy from their domestic farmers or infrastructure programmes can include equipment bought at home and set up abroad by experts from the aid sending country. Other types of aid can also yield indirect benefits as aid dependency can hold strategic benefits for the donor (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2007). A continuous provision of aid may create dependencies, which increase the aid sender’s influence in the recipient country and the international arena. A prominent example is the effect of aid allocation on UN voting (Dreher, Nunnenkamp, and Thiele Citation2008; Wang Citation1999; Wittkopf Citation1973). Continuous allocation of aid also makes donors’ resource allocation more efficient and may incentivise them to turn away from democracy promotion. We expect from a strategic perspective that, compared to other aid types, democracy promotion decreases when the donor experiences a democratic decline.Footnote11

Constructivist approaches provide an additional explanation for why democratic decline in donor states may lead to changes in aid allocation patterns. Addressing the identity of states, Huber (Citation2015) suggests that, unless an external threat perception is interfering, democratic identity and international norms of democracy lead to democracy promotion.Footnote12 We apply her argument to understand how decision-makers’ democracy promotion efforts may change under democratic decline. We outline how both democratic identity and international norms of democracy can explain this effect. Domestically, the democratic identity, defined as ‘the constitutive values and norms that define membership in a democracy’, encourages democracy promotion abroad (Huber Citation2015, 38). Due to public contestation of norms and values of democracy, donors can use democracy promotion to affirm their own identity. We assume that a substantive democratic decline goes beyond contestation and leads to changes in the democratic identity of a state and of its decision-makers. Consequently, we expect fewer democracy promotion efforts abroad after domestic democratic decline.

Internationally, we observe a recent decrease in democracy as an international norm (Lührmann et al. Citation2020). Inverting Huber’s argument (Citation2015, 39), we expect that, from the perspective of decision-makers with declining levels of democracy, democracy promotion becomes less legitimate and feasible. This is supported, firstly, by the fact that democracy as a one-fits-all solution has become increasingly questioned, reducing confidence in democracy promotion as a suitable policy. Secondly, democracy promotion is not perceived as a moral duty by decision-makers anymore, which allows them to compare its costs and benefits with alternative policies. And, thirdly, leadership in compliance with the norm of democracy and democracy promotion is not expected to generate the same level of soft-power as before (Huber Citation2015). These changes on the domestic and international level impact donors’ roles in foreign policy. From a constructivist perspective, role theory suggests that ‘foreign policy roles are not static’ (Knodt and Jünemann Citation2007, 20). We expect that alongside democratic decline roles, such as the EU’s role as an agent of international security and some member states’ role as a preserver of national interest (Knodt and Jünemann Citation2007), may conflict with and take precedence over the role as a democracy promoter. While these implications of a decrease in democracy as an international norm may affect all states’ international relations, this should be most substantive in such states that experience democratic decline domestically. This is why we expect lower allocation of aid for democracy promotion from a strategic and a constructivist perspective.

Hypothesis 1: If the donor experiences a democratic decline, the share of aid allocated for democracy promotion will decrease.

Does this argument affect all aspects of aid for democracy promotion equally? To analyse the quality of democracy promotion, we focus on the recipients as they have different approaches to implement democracy promotion aid. We provide insight into the allocation of democracy promotion to governments and CSOs relative to other aid recipients.Footnote13 We focus on governments and CSOs as aid recipients because they are two key actors crucial for successful democracy promotion, according to democratisation theories, and apply contrary approaches (see, for example, Tilly Citation2000). Government institutions contribute to democratisation within existing political structures, including free and fair elections and peaceful transitions to democratically elected office holders. CSOs do not aim for holding office but perform important democratic functions bottom-up, for example by aggregating societal interests, holding the state accountable (Diamond Citation1994; Fukuyama Citation2001), fostering democratic socialization and encouraging political participation (Hahn-Fuhr and Worschech Citation2014). Most importantly, CSOs may control and limit state power as they aim for ‘concessions, benefits, policy changes, relief, redress, or accountability’ (Diamond Citation1994, 6). Donors can prioritise any of these two approaches by selecting government institutions or CSOs as recipients of aid for democracy promotion.

Due to democratic decline in aid sending countries, we expect that democracy as a principle is less valued. Therefore, decision-makers expect less pushback from political opponents and the electorate if the recipient of democracy promotion aid is a non-democratic government. This is attractive for decision-makers aiming to save their face and legitimacy on the international level: by allocating aid to government institutions decision-makers can continue to support democracy promotion and yield additional benefits. Choosing government institutions in non-democratic states as the recipient of aid can be beneficial. Compared to CSOs and other aid recipients, these non-democratic governments can provide more added value to aid sending decision-makers as they have leverage in domestic and international politics without facing accountability towards their electorate.Footnote14

As recipients of aid, non-democratic governments can provide benefits to donors as they have unrestricted control over foreign politics. These benefits include soft power, for example through positive foreign public opinion (Goldsmith, Horiuchi, and Wood Citation2014), or more tangible results such as supporting policy initiatives or voting in international organisations (Bueno De Mesquita and Smith Citation2013). Aid receiving governments can also provide economic benefits by opening or restricting access to markets, preferential trade agreements and increases in bilateral trade (Nowak-Lehmann et al. Citation2009). Geo-strategic and security interests can be met, such as access to infrastructure, for example airbases (Dzyubenko Citation2014), security or military cooperation (Browne Citation2006). This is why we expect a higher benefit from choosing government institutions as recipients compared to CSOs. If donors experience a democratic decline, we hypothesise an increase in the proportion of government institutions as recipients.

CSOs provide the least additional benefits in the eyes of leaders in aid sending countries compared to other types of aid recipients. Thus, we expect democratic decline to change the focus from support for an independent civil society to support for strong government institutions in domestic as well as foreign policy. Rather than promoting bottom-up democratic practices implemented by CSOs, democracy promotion should address effective bureaucracies, the stability of the government and enhanced performance of institutions. As these aspects target government institutions, we expect that sending governments will favour such institutions when allocating aid. This enables donors to focus more on supporting and stabilising the government rather than the civil society sector.Footnote15

This argument is in line with the literature suggesting that less democratic states aim to strengthen the incumbent governments rather than other actors (Dietrich and Wright Citation2015). Less democratic governments face less opposition by civil society at home and, therefore, have only limited experience and interest in building effective working relationships with civil society abroad (Heiss Citation2017). We expect that donors who have recently experienced a democratic decline decrease their allocation of democracy promotion aid for projects implemented by CSOs. Consequently, we hypothesise that the relative level of democracy promotion aid allocated to governments will increase while aid provided to civil society organisations will decrease when the donors experience a decline in democracy. We assess the allocating of aid for democracy promotion to government institutions and CSOs relative to all other recipients of foreign aid, including multilateral organisations, teaching, research and private sector institutions.

Hypothesis 2.1: If the donor experiences a democratic decline, it will provide more aid for democracy promotion to government institutions relative to other recipients.

Hypothesis 2.2: If the donor experiences a democratic decline, it will provide less aid for democracy promotion to CSOs relative to other recipients.

5. Research design, data and operationalisation

We assess how democratic decline affects the allocation of aid for democracy promotion across Central Asia from 2000 to 2018. We combine data provided by the OECD (OECD Citation2020a), the V-Dem Project (Lührmann et al. Citation2020) and the World Bank (WB 2020). To assess the robustness of our findings, we provide a complementary analysis including IATI data (IATI Citation2020b). Compared to many studies focusing on the volume of aid flows, we closely examine the aid projects and recipients. This requires more detailed data. The OECD and IATA datasets provide the most comprehensive and fine-grained information available to measure aid allocation in Central Asia. This allows us to analyse the impact of democratic developments in the EU and its member states on the aid projects for democracy promotion and the recipients of such aid.Footnote16

Our dependent variables are the allocation of aid for democracy promotion relative to all other types of aid and the allocation of aid to governments or civil society organisations. These variables provide insight into the features of aid allocation for democracy promotion from the EU and its member states to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. We study the five Central Asian states as an example of many other non-democratic states worldwide, which are not dependent on the EU and its member states and do not hold the special status of inclusion in the European Neighbourhood Policy (Jünemann and Knodt Citation2007). Compared to other aid data, such as AidData, complementing OECD with IATI data is advantageous as it contains fine-grained information on the characteristics of aid allocation beyond aid flows and budgets.Footnote17

Our dataset includes information on the Central Asian states that receive aid and the EU and its member states that allocate aid. This allows us to trace the allocation of aid for democracy promotion to the respective state (Hypothesis 1) and to the government institutions or CSOs as recipients (Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2). While many studies analyse the volumes of aid flows aggregated temporally and spatially, we focus on individual aid projects and more specifically aid activities. One project can consist of one or multiple aid activities, which can vary in terms of duration, budget and scope. Analysing aid activities provides the advantage to more accurately examine the allocation of individual, disaggregated aid activities and to take their specifics and context into consideration. Individual aid activities are our unit of analysis and are defined as ‘any individual piece of development or humanitarian work, the scope of which is defined by the organisation publishing the data’ (IATI Citation2020b).Footnote18

Focusing on the aid activity as the unit of analysis allows us to assess the scope of democracy promotion by the EU and its member states connected to the ‘government and civil society’ sector (OECD Citation2020b). Aid activities in this sector are directly related to democracy promotion. This sector includes ‘Democratic participation and civil society’, ‘Elections’, ‘Legislatures and political parties’, ‘Media and free flow of information’ and ‘Human rights’ (OECD Citation2020b). We assess the proportion of aid allocated for democracy promotion with the dummy variable DemAid that takes the value 1 for aid projects on democracy promotion and 0 otherwise. We also assess the share of aid allocated to different types of organisations that are carrying out aid activities on the ground. Information on the type of organisation is available both in the OECD and IATI data. In our analysis, we differentiate between governmental and civil society actors implementing aid projects, rather than the private sector or multilateral organisations.Footnote19 We create the dummy variable government institution that takes the value 1 if aid is allocated to government institutions and 0 otherwise. Likewise, the dummy variable CSOs measures if the recipient is a civil society organisation (1) or any other type of organisation (0).

We focus on aid allocated by the EU or one of its member states from 2000 to 2018, as this time period guarantees a relative consistency of the reported data. Our dataset contains 986,342 aid activities reported by the OECD as allocated to the five Central Asian states by the EU as an institution or bilaterally by any of its member states. To test Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2, we only focus on aid for democracy promotion, analysing 108,236 aid activities in the OECD data. As OECD data provides more comprehensive information while IATI data allow for a more detailed insight into the aid activities, we run separate statistical models for each of the two data sources.

We assess the effect of our main independent variable, DemDecline to study the variation in the features of allocated aid activities. Our measure of democratic decline relies on the V-Dem dataset and identifies annual changes based on the liberal democracy index for the EU as a whole and for each EU member individually in each of the years under study. We employ the change in the liberal democracy index as compared to the previous year to examine democratic decline. Data from the V-Dem project provides the most comprehensive measure of a country’s changing levels of democracy based on a combination of expert assessment and large-n data compared to other measures such as Polity IV and Freedom House. Changing levels of democracy reflect short-term changes and not necessarily threats to democracy as a regime type. Our democratic decline score is calculated as follows:

To check the robustness of the effect of democratic decline, we also include the variable LibDem EU. It measures the level of democracy as an alternative to democratic decline with V-Dem’s liberal democracy index and Polity IV based on the scores from the Polity IV dataset. Both measures are lagged by one year to account for the adjustment of aid policy over time. As democratic decline in the EU constitutes a recent trend, we focus on one-year lags to capture short-term changes. One-year lags also reflect the EU’s approach to evaluate its Central Asia strategy in a one up to maximum two-year timeframe (Council EU Citation2007, 18).

To assess the explanatory power of our main independent variable, we added a number of control variables. We differentiate characteristics of the donor and recipient country, which might affect the relationship between democratic decline and aid allocation for democracy promotion. Regarding the donor, we include the sending country’s economic situation, as this should have an effect on its ability and willingness to allocate aid. The variable GDP per capita EU measures the economic prosperity based upon GDP per capita in current US Dollar and GDP growth EU provides the annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita (WB 2020). To account for differences in the allocation of multilateral and bilateral aid, we include the dummy variable multilateral based on information in the OECD or IATI data. The dummy variable takes a value of 1 for the EU as a funding institution and 0 for a member state as funder. We include both bilateral and multilateral aid as the EU member states impact the decision-making process in both cases.

We also assess how developments in the recipient country influence aid allocation in Central Asia. We check if the economic situation in the recipient country has led to a different aid allocation pattern. The variable GDP per capita CA is measured in current US Dollar and GDP growth CA is the GDP per capita’s annual percentage growth included to account for changes over time (WB 2020). We also control for changes in aid related to the recipient country’s level of democracy (Warkotsch Citation2007). We measure LibDem CA based on the V-Dem liberal democracy index using a lag of one year as we expect donors to adjust their allocations over time. To address any potential substitution of aid in the form of foreign direct investment (Alesina and Dollar Citation2000), we include the annual value of foreign direct investment with the control variable FDI (WB 2020). As foreign direct investment can be used by donors to reach their goals, for example in terms of aid conditionality, it is relevant to control for it in our analysis. Foreign direct investment also provides evidence of the recipient country’s openness towards international interactions which can relate to democracy promotion efforts (Carothers Citation2006). Given the importance of oil in the region and potential economic costs or benefits for the EU and its member states (Knodt and Jünemann Citation2007), we included the variable oil rents. It measures the share of oil rents from the overall GDP based on World Bank data (WB 2020). To account for conflicts in the recipient countries that could redirect aid away from democracy promotion and towards other types of aid, for example, humanitarian aid, we included a dummy variable for conflict which accounts for all conflicts recorded by the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (Gleditsch et al. Citation2002), UCDP Non-State Conflict Dataset (R. Sundberg, Eck, and Kreutz Citation2012) and the revolution in Kyrgyzstan in 2005 (1) or no conflict (0) on the country-year level.

Another major impact on the allocation of aid for democracy promotion stems from foreign support for elections and election observation. We included the dummy variable election to account for the years in which presidential or parliamentary elections took place (1) versus years in which there were none (0) in the aid receiving countries. With the country dummies Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, we examine the effects specific to the individual recipient countries. provides summary statistics for the variables in our analysis for Hypothesis 1 based on OECD data.

Table 1. Summary statistics OECD data (Hypothesis 1).

Due to the nature of our dependent variables, which have binary outcomes, we calculate logistic regression models in our analysis of the OECD and IATI data. We estimate the effects of democratic decline on the features of aid allocation in Central Asia. To address our nested data structure, we combine logistic regression models with cluster-robust standard errors and country dummies to account for country effects.

6. Findings

6.1. Aid allocation in Central Asia

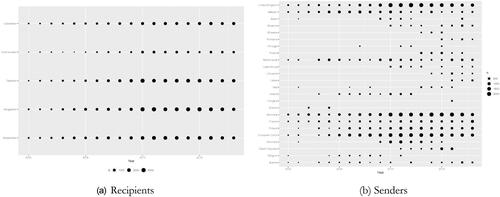

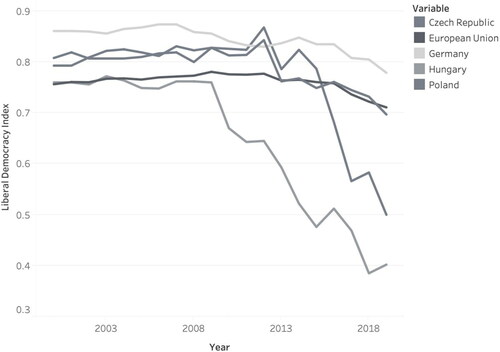

Based on OECD data on aid allocation by the EU and its member states from 2000 to 2018, we find that 10.9% of all aid activities are for promoting democracy. The number of democracy promotion activities varies among the recipients and the donors (see ). Regarding aid recipients (see ), Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan obtain the least aid for the promotion of democracy. There is a rise in the number of aid activities across all countries starting from 2009, with a subsequent decline in the number of activities in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan starting from 2015.Footnote20 In contrast, activities in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and the overall region have slightly increased over this time. Given the recent announcements by Germany, one of the biggest donors in Central Asia, regarding a decrease in its aid activities in the region and to cooperate only with Uzbekistan, further declines are likely to follow (BMZ Citation2020). Such trends are consistent with democratic developments in Central Asia (Tumenbaeva Citation2020) and with our expectations based on the democratic development of the EU and selected member states (see ).

Figure 2. Liberal democracy index (selected cases) (Lührmann et al. Citation2020).

We observe changes in the number of activities by donor across Central Asia. The distribution of aid by donor (), indicates that the major providers include the EU institutions, Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and Austria. The EU countries with the most pronounced democratic decline, Hungary and Poland, have diverged from the overall trend of decreasing aid activities in non-democratising states. Instead, they started their activities from 2013. Poland became a donor in the field of democracy promotion in the region starting in 2013, and has sent aid to three countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan), while Hungary started its activities in 2014. This is consistent with the idea that autocratic states are prone to cooperating with autocratic partners (Bader, Grävingholt, and Kästner Citation2010). This could be one explanation why Hungary and Poland have slightly shifted their foreign policy focus toward Central Asia. Germany, on the other hand, has taken a conditionality approach and cut its activities in the region in response to the absence of improvements in the democratic sector.

6.2. Democratic decline and democracy promotion

Using regression analysis, we test our hypotheses on OECD and IATI data. We compare three different specifications of logistic regression models including cluster-robust standard errors and country dummies.Footnote21 We present the results from selected logistic regression models and the change in predicted probabilities of aid allocation for democracy promotion relative to all aid types to test our first hypothesis.

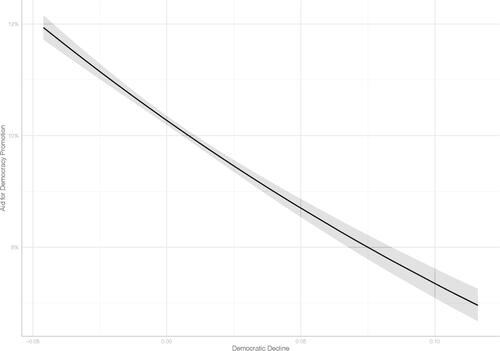

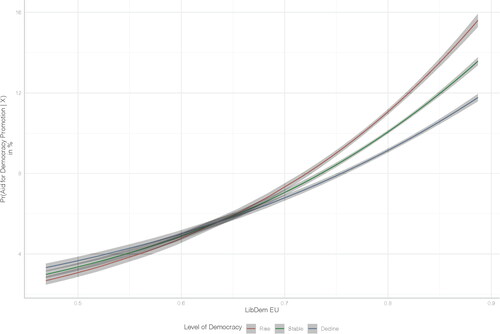

provides the results for OECD data, which include three alternative measures for democratic decline in the EU. Model 1 assesses the effect of democratic decline and shows that it has a statistically significant negative effect on providing aid for democracy promotion. Thus, we find support for Hypothesis 1, which claims that if the donor experiences democratic decline, the share of aid allocated for democracy promotion will decrease. Such findings are in accordance with the strategic and constructivist perspective on aid allocation. We observe that even a short-term decline in democracy in the donor countries leads decision-makers to immediately put less priority on democracy promotion. As donors experience democratic decline, decision-makers may benefit more from other forms of aid and reduce their relative share of aid allocated for democracy promotion.

Table 2. Democratic decline and aid for democracy promotion (OECD).

This result is robust for both OECD and IATI data (for results based on IATI data see the Appendix, ). To test the robustness of our findings, we include V-Dem’s liberal democracy index and the Polity IV index both lagged by one year as an alternative measure of the level of democracy in the aid sending country (Model 2 and 3). These alternative approaches to measuring the donor’s state of democracy also support the finding indicating that higher levels of democracy of the sender increase the allocation of aid for democracy promotion relative to other aid types. Additional robustness tests examine if democratic decline impacts countries with high or low levels of democracy differently (see the Appendix, and ).

These results can only be partially supported by IATI data (see ). Both models show statistically significant findings, while only for Polity IV the effects display the expected direction. As IATA is less comprehensive than OECD data, we rely more heavily on the findings based on OECD data. For OECD and IATI data, these findings are consistent for models with cluster-robust standard errors with and without country dummies. Across all models assessing Hypothesis 1, our measure of democratic decline DemDecline provides a better model fit compared to the other measures which represent annual democracy scores.Footnote22 The results also hold for individual models by recipient country (see the Appendix, ) and bilateral aid allocation (see the Appendix, ).Footnote23

To evaluate the substantive effect of democratic decline on the share of aid allocated for democracy promotion, we calculate predicted probabilities based on OECD data in Model 1 (). If we compare donors that experience no democratic decline with donors with a decline of 0.12, this results in a decrease in aid for democracy promotion compared to other aid types by 3 percentage points from 10% to 7%. These findings are statistically significant as indicated by the confidence intervals (CI) in support of our expectations from Hypothesis 1. Poland has experienced such a democratic decline from 2016 to 2017 ().Footnote24

6.3. Democratic decline and recipients

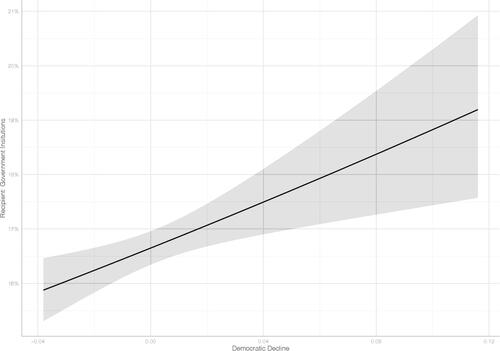

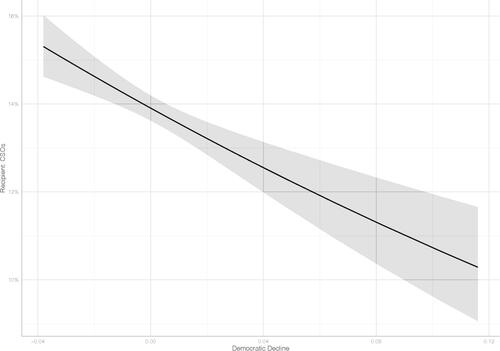

To test the second set of hypotheses, we focus only on aid for democracy promotion and its recipients. Our basic models without cluster-robust standard errors and country dummies provide statistically significant findings in support of Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2 based on the more comprehensive OECD data. Based on the models for OECD data in , we find some support for our expectations for Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2. While the direction of the effect holds up to our expectations in all models, only the model without cluster-robust standard errors and country dummies provides statistically significant findings.

Table 3. Democratic decline and recipients of democracy promotion (OECD).

The majority of results based on the IATI data (see ) do not show significant results. Only the model including cluster-robust standard errors provides significant findings at the 5% level but the effect is counter our expectations. One explanation for these diverging findings could be the small number of observations and higher number of missing values measuring the type of recipients in IATI data. As the consistency and comprehensiveness of the OECD data are more substantive, we still find partial support of Hypotheses 2.1 and 2.2. We conclude that decision-makers experiencing democratic decline in their home county are more likely to allocate aid for democracy promotion to government institutions relative to all other recipients. Under such conditions, decision-makers allocate less aid to CSOs. Such findings are in line with assumptions on increased cooperation among less democratic governments. While the supporting evidence has limitations, our results imply that as democracy is decreasing in donor countries, in the recipient countries government institutions can expect to benefit from more aid for democracy promotion relative to other recipients, while CSOs receive less funds. To assess the substantive effect, we compare donors experiencing no democratic decline and such with a decline of 0.12 with OECD data (Model 1 in ). They differ in their predicted probability of aid for government institutions compared to all other recipients of aid by 2 percentage points of about 17% and 19% (see ). For CSOs as recipients of aid for democracy promotion, we find a relative decrease in allocated aid projects as expected. As shows, the predicted probability that the recipient is a CSO compared to all other types of recipients is about 4 percentage points lower for donors with a democratic decline of 0.12 (14%) compared to no democratic decline (10%). As indicated by the confidence intervals, these findings from predicted probabilities are statistically significant. From 2016 to 2017 Romania experienced such a democratic decline.Footnote25

7. Conclusion

To address the question of how democratic decline in the donor states affects their allocation of aid, we focus on the perspective of decision-makers in the donor countries. Based on strategic and constructivist approaches, we hypothesise that as donors experience democratic decline, they allocate less foreign aid for democracy promotion. Regarding the recipients of aid, we expect that donors, which experience democratic decline, allocate more aid to governments compared to other types of aid recipients. We expect that CSOs receive less aid for democracy promotion compared to other aid recipients. We find evidence that aid allocation for democracy promotion is affected by democratic decline in the EU and its member states. Studying the five Central Asian states, allows us to retrieve findings generalizable to other regions beyond the immediate EU neighbourhood and cases where democracy promotion is fragile despite the EU’s ongoing engagement.

We identify a decline in allocation for democracy promotion relative to other types of aid if donors face democratic decline. Our descriptive findings identify volatility in the number of aid activities implemented in the period from 2000 until 2018. They indicate shifting trends with an overall decrease of aid for democracy promotion coinciding with democratic decline in the EU and some of its members. We find statistically significant effects of donors’ democratic decline on the proportion of aid for democracy promotion. This finding is robust across OECD and IATI data, three operationalizations of democratic decline in the donor states and three model specifications. Our measures also reflect our interest in understanding short-term effects and to investigate substantive democratic decline in the recent past.

More inconclusive findings stem from our investigation of the recipients. We find support for our expectations that democratic decline in the donor countries leads to a relative increase in aid projects allocated to government institutions. CSOs experience a relative decrease compared to other aid recipients. These findings are not robust across all model specifications and IATI data. This is why we only find partial support for the expected relative increase in government institutions and decrease in CSOs as recipients of aid for democracy promotion. As IATI data is less reliable and comprehensive, we place our trust on the main results based on OECD data. More detailed data reporting from aid projects may allow for more conclusive findings in the future.

While our study shows that the allocation of democracy promotion through aid is reduced along-side the donor’s declining levels of democracy, some limitations remain. Our quantitative approach presents empirical evidence beyond individual cases and experts’ assessments. Further qualitative studies could provide insight into the underlying individual motives to complement our findings. Our study is the first approach to identify overall effects of democratic decline in donor countries covering a wide range of donor and recipient countries. We find statistically significant effects across multiple data sources, operationalizations and model specifications, but the effect sizes are moderate. Regarding the recipients of aid, we only find partial support for our expectation that the proportion of aid allocated to government institutions increases, while it decreases for CSOs. Multiple factors might be responsible for this: the short timeframe of democratic decline in the EU and its member countries has limited our analysis so far. As the EU member states with the sharpest democratic decline only recently started distributing aid to Central Asia beyond multilateral projects, we cannot expect to see strong effects. Over time, we might be able to identify more substantive trends. Future aid allocation by the countries that are most affected by democratic decline and their foreign policy relationships deserve our attention. Our results are also in line with the EU and its member states’ overall limited efforts in democracy promotion (Warkotsch Citation2007). Given the rather small although clear trend towards democratic decline, small effect sizes or mixed findings should not be surprising.

Future approaches to address the multidimensionality of democracy promotion can benefit from more comprehensive data availability and reporting quality as well as a broader scope of available information on aid allocation. This includes large-n data on recipients’ openness to receive aid for democracy promotion (Carothers Citation2006). Compared to many studies, we went beyond aggregated aid flows and analysed the allocation of individual aid activities. Studies identify difficulties to differentiate the EU’s policies for good governance and democracy promotion (Youngs Citation2010) outside of in-depth single case studies (Bossuyt and Kubicek Citation2011). We presented a quantitative approach to study the variation in democracy promotion by disaggregating the support of good governance through local governmental institutions and support for democracy from below through CSOs with existing data. This allowed us to shed light on the multiple faces of the EU and its member states’ democracy promotion efforts. It highlights the importance to look beyond the normative rhetoric of the EU and focus on the perspective of the respective decision-makers’ allocation patterns. Taking both the national and EU level into account proves important to understand recent trends.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna-Lena Hönig

Anna-Lena Hönig is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Konstanz. Her research examines civil society in autocracies with a focus on political protest, repression and cooperation. Email: [email protected]

Shirin Tumenbaeva

Shirin Tumenbaeva is an assistant professor at the American University of Central Asia and a PhD candidate at the Central European University. Her research areas are elections, voting behaviour and democratisation. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 We use the term donor to describe aid sending counties synonymous with aid provider and aid sender. We do not imply altruistic motives but use the term to increase readability and to address the relevant literature.

2 The exception is Kazakhstan as the country was more attractive to foreign donors due to its natural resources and political stability (Luong and Weinthal 2010).

3 The European Neighbourhood Policy specifies a more pronounced interest in promoting democracy in the EU’s immediate neighbourhood compared to other regions (EC 2015).

4 While we use the term democratic decline in this paper, we think of democratic backsliding as identical concept. Short term democratic decline may or may not amount to a substantive threat to democracy as a regime type and governance model.

5 Bermeo (Citation2016) takes a different approach including cases of complete overturn of the political system, for example coups d’état. We do not study cases of sudden regime change in this paper, only those of gradual decline in democracy.

6 For example, the Council of the European Union’s Foreign Affairs Council has defined the following priorities that foreign aid should address in Central Asia: ‘(a) rule of law, human rights and democratisation; (b) education and training; (c) economic development, trade and investment; (d) transport and energy; (e) environmental sustainability and water management; (f) facing shared threats and challenges; (g) intercultural dialogue’ (ECA 2013, 12).

7 For a comprehensive overview of the EU’s democracy promotion efforts addressing civil society see Shapovalova and Youngs (Citation2014).

8 For a discussion with a focus on populism, which can appear alongside democratic decline, see Verbeek and Zaslove (Citation2017).

9 For further discussion of regime types’ impacts on different forms of international cooperation see for example Mattes and Rodríguez (Citation2014) or Leeds (Citation1999).

10 While this paper focuses on democratic decline, our argument is also in line with the literature on populism, which identifies a prioritisation of self-interest (see for example Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2018).

11 Full autocracies might engage in autocracy promotion. We expect donors from the EU and its member states experiencing only a relative decline in democracy not to shift to promoting autocracy but to instead reduce their efforts in democracy promotion.

12 Huber (Citation2015) refers to these concepts as democratic role identity composed of democratic type identity and international norms of democracy.

13 These include local branches of international organisations and for-profit consulting firms (Carothers Citation2009).

14 This argument also holds for CSOs that are state-controlled, such as government-operated NGOs (GONGOs), as providing aid to them compared to government institutions directly also holds a higher risk for decision-makers in aid sending states not to receive the expected returns and level of accountability.

15 Based on existing research on the relevance of all CSOs for building and maintaining democracy through social capital (Putnam Citation2000), we are not only interested in those CSOs that directly promote democracy but all CSOs.

16 While we include aid flows from the EU and its member states, note that there is no overlap as we focus on multilateral aid by EU institutions and bilateral aid by the individual member states respectively.

17 Complementing the data provided by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD with IATI data provides the main advantage that information on various dimensions of individual aid activities is accessible. This enables hand-coding of missing data and cross-checking the plausibility of the reported information.

18 We also refer to aid activities as projects in this paper.

19 OECD and IATI data distinguish between the following types of recipients referred to as channels: ‘public sector’, ‘NGOs & civil society’, ‘public-private partnerships’, ‘multilateral organizations’, ‘teaching institutions, research institutions or think-tanks’, ‘private sector institutions’, ‘other’ and ‘not reported’ (OECD Citation2020b).

20 The recent increase in the number of aid projects for democracy promotion in Kazakhstan can be related to the resignation of President Nazarbaev and new opportunities commencing with the term of Tokaev.

21 We compare the results of three model specifications all based on logistic regression models: (1) without cluster-robust standard errors and country dummies; (2) with cluster-robust standard errors and no country dummies; (3) cluster-robust standard errors and country dummies.

22 We find similar effects if we measure democratic decline by a two year difference (ΔDemDecline = LibDemScore(year) − LibDemScore(year 2)). A five-year moving average would provide a suitable alternative measure. It cannot be applied yet as democratic decline in the EU and its member states is a recent phenomenon.

23 To assess if the results are driven by those countries that experience the most substantive decline in democracy, we exclude Hungary and Poland. We can show that the main effects remain robust.

24 Poland’s liberal democracy index decreased from 0.682 (CI 0.62–0.74) in 2016 to 0.566 (CI 0.52–0.6) in 2017.

25 The Romanian liberal democracy index decreased from 0.595 (CI 0.62–0.74) in 2016 to 0.493 (CI 0.52–0.6) in 2017.

References

- Alesina, Alberto, and David Dollar. 2000. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (1): 33–63.

- Babayan, Nelli. 2015. “The Return of the Empire? Russia’s Counteraction to Transatlantic Democracy Promotion in Its Near Abroad.” Democratization 22 (3): 438–458.

- Bader, Julia, Jörn Grävingholt, and Antje Kästner. 2010. “Would Autocracies Promote Autocracy? A Political Economy Perspective on Regime-Type Export in Regional Neighbourhoods.” Contemporary Politics 16 (1): 81–100.

- Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 5–19.

- BMZ. 2020. “Reformkonzept ‘BMZ 2030’.” Accessed 21 January 2021. https://www.bmz.de/de/mediathek/publikationen/reihen/infobroschueren_flyer/infobroschueren/sMaterialie510_BMZ2030_Reformkonzept.pdf.

- Boonstra, Jos, and Riccardo Panella. 2018. “Three Reasons Why the EU Matters to Central Asia.” Voices on Central Asia, March 13. Accessed 20 April 2020. https://voicesoncentralasia.org/three-reasons-why-the-eu-matters-to-central-asia/.

- Bossuyt, Fabienne. 2018. “The EU’s and China’s Development Assistance towards Central Asia: Low versus Contested Impact.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 59 (5–6): 606–631.

- Bossuyt, Fabienne, and Paul Kubicek. 2011. “Advancing Democracy on Difficult Terrain: EU Democracy Promotion in Central Asia.” European Foreign Affairs Review 16 (5): 639–658.

- Bourguignon, François, and Mark Sundberg. 2007. “Aid Effectiveness–Opening the Black Box.” American Economic Review 97 (2): 316–321.

- Browne, Stephen. 2006. Aid and Influence. Do Donors Help or Hinder? London: Earthscan.

- Bueno De Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. 2007. “Foreign Aid and Policy Concessions.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51 (2): 251–284.

- Bueno De Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. 2009. “A Political Economy of Aid.” International Organization 63 (2): 309–340.

- Bueno De Mesquita, Bruce, and Alastair Smith. 2013. “Aid: Blame It All on ‘Easy Money’.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 57 (3): 524–537.

- Burnside, Craig, and David Dollar. 2000. “Aid, Policies, and Growth.” American Economic Review 90 (4): 847–868.

- Carnegie, Allison, and Nikolay Marinov. 2017. “Foreign Aid, Human Rights, and Democracy Promotion: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 671–683.

- Carothers, Thomas. 2006. “The Backlash against Democracy Promotion.” Foreign Affairs 85 (2): 55–68.

- Carothers, Thomas. 2009. “Democracy Assistance: Political vs. Developmental?” Journal of Democracy 20 (1): 5–19.

- Chen, Dingding, and Katrin Kinzelbach. 2015. “Democracy Promotion and China: Blocker or Bystander?” Democratization 22 (3): 400–418.

- Chin, Gregory, and Fahimul Quadir. 2012. “Introduction: Rising States, Rising Donors and the Global Aid Regime.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 25 (4): 493–506.

- Cornell, Svante E., and S. Frederick Starr. 2019. “A Steady Hand: The EU 2019 Strategy & Policy towards Central Asia.” Silk Road Paper.

- Council of the European Union (Council EU). 2007. “The EU and Central Asia: Strategy for a New Partnership.” Accessed 21 January 2021. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10113-2007-INIT/en/.

- Del Biondo, Karen. 2015. “Promoting Democracy or the External Context? Comparing the Substance of EU and US Democracy Assistance in Ethiopia.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28 (1): 95–114.

- Diamond, Larry. 1994. “Rethinking Civil Society: Toward Democratic Consolidation.” Journal of Democracy 5 (3): 4–17.

- Diamond, Larry. 2017. “When Does Populism Become a Threat to Democracy?” FSI Conference on Global Populisms (Stanford University, November 3-4, 2017). Accessed 26 September 2020. https://diamond-democracy.stanford.edu/speaking/speeches/when-does-populism-become-threat-democracy.

- Dietrich, Simone, and Joseph Wright. 2015. “Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa.” The Journal of Politics 77 (1): 216–234.

- Dreher, Axel, Peter Nunnenkamp, and Rainer Thiele. 2008. “Does US Aid Buy UN General Assembly Votes? A Disaggregated Analysis.” Public Choice 136 (1–2): 139–164.

- Dzyubenko, Olga. 2014. “‘Mission Accomplished’ for U.S. Air Base in Pro-Moscow Kyrgyzstan” Reuters, March 6. Accessed 21 January 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kyrgyzstan-usa-base-idUSBREA251SA20140306.

- European Commission (EC). 2015. “Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Review of the European Neighbourhood Policy.” Accessed 26 September 2020. http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/neighbourhood/pdf/key-documents/151118_joint-communication_review-of-the-enp_en.pdf.

- European Court of Auditors (ECA). 2013. “EU Development Assistance to Central Asia. Special Report No 13.” Accessed 04 January 2021. http://eca.europa.eu.

- European Union (EU). 2019. “Factsheet Central Asia.” Accessed 26 September 2020. http://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/factsheet_centralasia_2019.pdf

- Fawn, Rick. 2020. “The Price and Possibilities of Going East? The European Union and Wider Europe, the European Neighbourhood and the Eastern Partnership.” In Managing Security Threats along the EU’s Eastern Flanks, edited by Rick Fawn, 3–29. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2001. “Social Capital, Civil Society and Development.” Third World Quarterly 22 (1): 7–20.

- Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg, and Håvard Strand. 2002. “Armed Conflict 1946-2001: A New Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 39 (5): 615–637.

- Goldsmith, Benjamin E., Yusaku Horiuchi, and Terence Wood. 2014. “Doing Well by Doing Good: The Impact of Foreign Aid on Foreign Public Opinion.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 9 (1): 87–114.

- Greene, Zachary D., and Amanda A. Licht. 2018. “Domestic Politics and Changes in Foreign Aid Allocation: The Role of Party Preferences.” Political Research Quarterly 71 (2): 284–301.

- Grimm, Sonja, and Julia Leininger. 2012. “Not All Good Things Go Together: Conflicting Objectives in Democracy Promotion.” Democratization 19 (3): 391–414.

- Hahn-Fuhr, Irene, and Susann Worschech. 2014. “External Democracy Promotion and Divided Civil Society – The Missing Link.” In Civil Society and Democracy Promotion, edited by Timm Beichelt, Irene Hahn-Fuhr, Frank Schimmelfennig, and Susann Worschech, 11–41. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hansen, Henrik, and Finn Tarp. 2000. “Aid Effectiveness Disputed.” Journal of International Development 12 (3): 375–398.

- Heiss, Andrew. 2017. “Amicable Contempt: The Strategic Balance between Dictators and International NGOs.” PhD thesis, Duke University.

- Hönig, Anna-Lena. 2020. “Zivilgesellschaft [Civil Society].” In Die Politischen Systeme Zentralasiens: Interner Wandel, Externe Akteure, Regionale Kooperation [Central Asia’s Political Systems: Internal Change, External Actors, Regional Cooperation], edited by Jakob Lempp, Alexander Brand, and Sebastian Mayer, 191–205. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Hoffmann, Katharina. 2010. “The EU in Central Asia: Successful Good Governance Promotion?” Third World Quarterly 31 (1): 87–103.

- Holzhacker, Ronald, and Marek Neuman. 2019. “Framing the Debate: The Evolution of the European Union as an External Democratization Actor.” In Democracy Promotion and the Normative Power Europe Framework: The European Union in South Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, edited by Marek Neuman, 13–36. Cham: Springer.

- Huber, Daniela. 2015. Democracy Promotion and Foreign Policy: Identity and Interests in US, EU and Non-Western Democracies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hyde, Susan D. 2020. “Democracy's Backsliding in the International Environment.” Science 369 (6508): 1192–1196.

- IATI. 2020a. “Data Quality.” Accessed 14 March 2020. http://dashboard.iatistandard.org/data_quality.html.

- IATI. 2020b. “Types of Data.” Accessed 14 March 2020. https://iatistandard.org/en/using-data/types-of-data/.

- Jünemann, Annette, and Michèle Knodt. 2007. “Explaining EU-Instruments and Strategies of EU Democracy Promotion. Concluding Remarks.” In European External Democracy Promotion, edited by Annette Jünemann and Michèle Knodt, 353–369. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Kaufman, Robert R., and Stephan Haggard. 2019. “Democratic Decline in the United States: What Can We Learn from Middle-Income Backsliding?” Perspectives on Politics 17 (2): 417–432.

- Kluczewska, Karolina, and Shairbek Dzhuraev. 2020. “The EU and Central Asia: The Nuances of an ‘Aided’ Partnership.” In Managing Security Threats along the EU’s Eastern Flanks, edited by Rick Fawn, 225–251. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Knack, Stephen. 2004. “Does Foreign Aid Promote Democracy?” International Studies Quarterly 48 (1): 251–266.

- Knodt, Michèle, and Annette Jünemann. 2007. “Introduction: Theorizing EU External Democracy Promotion.” In European External Democracy Promotion, edited by Annette Jünemann and Michèle Knodt. Baden-Baden: Nomos: 9–29.