Abstract

Although international organisations (IOs) are created by governments, their international public administrations (IPAs) have succeeded in ring-fencing their resources, and policymaking from direct intervention by member states. Research shows that international civil servants are best able to protect their autonomy when embedded in large and well-resourced IPAs. Staff in large IOs use their huge size, bureaucratic complexities, and different behavioural logics to protect their autonomy and thereby leave a ‘bureaucratic footprint’ in international affairs. Whereas the behavioural logics of large IPAs, mostly headquartered in the Global North, are reasonably well-documented, not much has been written on behavioural logics of international civil servants embedded in small secretariats. We seek to address the gap using the African Union Commission (AUC) staff. Drawing insights from organisational theory and mixed research methods, including the first ever comprehensive survey of AUC staff, the study finds that the AUC staff primarily evoke a departmental behavioural logic. In the absence of departmental logics, the preference of AUC staff is to take on supranational, transnational, and lastly intergovernmental persona. The reluctance of AUC staff to evoke intergovernmental logic is surprising given that the AUC is embedded in an intergovernmental governance architecture.

Introduction

International organisations (IOs) differ significantly in terms of functions and size. Their number and size of their secretariats have grown substantially over the past three decades (Braveboy-Wagner Citation2009; Coe Citation2019; Tieku Citation2018). There has been a corresponding scholarly interest in understanding the complex interface between international ‘bureaucracy’ and policymaking in several social science disciplines, including political sociology, social psychology, comparative politics, and international relations (IR) (Benz and Goetz Citation2021). From the perspectives of political science, it is of paramount interest to, first, grasp the scope of autonomy that international organisations may ultimately command and second to understand how civil servants contribute to it (Jörgens, Kolleck, and Saerbeck Citation2016; Fleischer and Reiners Citation2021; Trondal et al. Citation2010). The latter is at the very heart of the nascent studies of international public administration (IPA). As a subfield of public administration scholarship, it focuses on the extent to which IPAs and their bureaucratic staff contribute to IO autonomy. The capacity of IOs to act is to a large extent supplied by the autonomy of its bureaucratic arm, that is, by the ability of IPAs – and their staff – to act relatively independently of mandates and decision premises from member-state governments (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Biermann and Siebenhuner Citation2009, Citation2013; Cox and Jacobson Citation1973; Reinalda Citation2013; Trondal Citation2013). The issue of autonomy lies at the heart of contemporary IPA research (see for example Ege Citation2020; Eckhard and Dijkstra Citation2017). It is therefore essential to know how autonomous these administrators are and what can explain it. Autonomy used here is defined as the extent to which an organisation can decide for itself matters that it deems important (Verhoest et al. Citation2010: 18–19). While we recognise that autonomy can evolve as a consequence of the international civils servants’ intention (within the confines of a mandate) or the result of a specific decision-making process, in this study, we measure autonomy by the extent to which international civil servants evoke a behavioural logic (see section IV). The IPA scholarship has so far shown that although IOs are created by governments, some of their secretariats have succeeded in ring-fencing their resources, recruitment practices, and – eventually – policymaking from direct member-state interferences (Trondal et al. Citation2010; Olsson and Verbeek Citation2018; Fleischer and Reiners Citation2021; Tieku Citation2021). It has been shown that international civil servants often use different behavioural logics, formalisation, standardisation, and control of procedures to protect their autonomy; they are good at ring-fencing their autonomy when embedded in large, complex well-resourced IPAs (Bauer, Knill, and Eckhard Citation2017; Beyers Citation2010; Checkel Citation2007; Moravcsik Citation1999; Nair Citation2020; Stone and Moloney Citation2019; Debre and Dijkstra Citation2021). International civil servants often use large and complex bureaucracies as platforms to develop their own preferences and shape IO decision-making (Hawkins et al. Citation2006) thereby leaving a ‘bureaucratic footprint’ in global governance and public policy (Biermann and Siebenhuner Citation2009; Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009). Both IPA and IO literature has shown that large IPAs, mostly housed in the Global North, usually evoke supranational and transnational behavioural logics when exercising their autonomy. But what behavioural logics do international civil servants embedded in small and less well-resourced IPAs usually invoke when exercising their autonomy on a day-to-day basis?

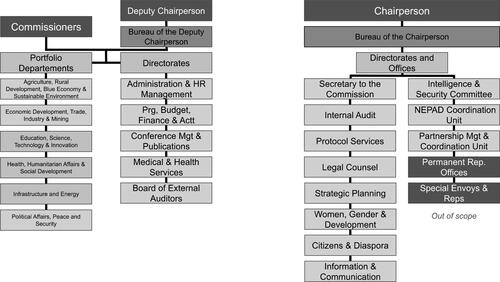

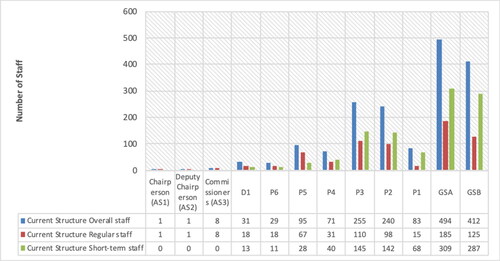

We investigate this puzzle using the African Union Commission (AUC) staff. Since small and less-resourced IPAs may have small capacity to ring-fence their autonomy, the AUC may be considered a less likely case of IPA autonomy. Compared to the executive arms of other IOs, the AUC is relatively small with just approximately 1720 staff as of March 2021 (Tieku Citation2021; see and ). For comparison, the administration of the European Union (EU), the AU’s continental counterpart, has more than 30,000 staff, The UN Secretariat, in turn, employs over 38,000 international civil servants. Moreover, the AUC is embedded within the overall intergovernmental organisational design of the African Union (AU) (Welz Citation2020). Although some of the earlier literature on African IOs (see Clapham Citation1996; Söderbaum Citation2004, Citation2016), treated IPAs as nothing but glorified servants of regimes, many recent studies show that international civil servants of the AUC not only exercise considerable autonomy but also drive international affairs in Africa and beyond (Ayebare Citation2018; Karbo and Murithi Citation2018; Souaré Citation2018; Witt Citation2019; Tieku Citation2021). AUC staff have thus been instrumental in creating and applying rules that shape political dynamics within African countries (Witt Citation2019), developing positions that influence international relations (Ayebare Citation2018), and establishing norms that even impact the politics of other regions (Souaré Citation2018). Thus, by using the AUC staff to examine IO autonomy and behavioural logics, this study offers a hard case.

Figure 1. AUC organisational structure.

Source: Own compilation, based on decision made at the 34th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly in February 2021.

Figure 2. AUC staff structure.

Source: Own compilation, based on data submitted to PRC Sub-Committee on Structural Reforms.

Drawing insights from data collected through mixed research methods the study finds that the AUC staff primarily evoke a departmental behavioural logic. If they are unable or unwilling to evoke departmental logics or wish to exhibit other behaviours, their preference is to take on supranational and transnational persona. The intergovernmental logic is often the last to be evoked. This observation is quite surprising given that the AUC is embedded in an intergovernmental governance architecture.

As specified in section IV of the paper, behavioural logics represent the set of actor-level decision-making patterns that are available to actors within organisations. In our study we operationalise four behavioural patterns – or logics – that international civil servants may choose from or evoke (see section IV). The study thus substantiates that IPAs may possess considerable capacity to act relatively independent of member-state governments as demonstrated when international civil servants develop a departmental mind-set. The study thus makes two particular theoretical contributions. First, it advances contemporary IR literature on IO autonomy. It empirically reveals the behavioural logics of international civil servants based outside of the OECD and UN-system. It shows how AUC bureaucrats balance competing internal expectations and perceptions regarding the roles they play in everyday decision-making processes. Secondly, the study advances contemporary organisation theory by outlining a conceptual role-set for IPA staff. This conceptual toolkit allows us to show that internal organisational structures of IPAs enable international civil servants to exercise autonomy. In line with a Weberian model of bureaucracy, IPAs thus have capacity to create codes of conduct and senses of autonomy that are relatively independent of constituent states (Weber Citation1924). The conceptual typology on actor-level behavioural logics enables precise empirical probes on the complexity and multi-dimensionality of IPAs. The research strategy is to study actor-level autonomy as evoked by international civil servants. There are at least two reasons for choosing an actor-level strategy. First, the behavioural discretion available to bureaucracies is made real by individual officeholders (Cox and Jacobson Citation1973). Secondly, the rise of relatively autonomous IPAs requires that international civil servants’ ‘preferences and conceptions of themselves and others’ are affected (Olsen Citation2005: 13). By accounting for variation in the role-set evoked by AUC staff, the study offers a helpful organisational approach that accounts for how bureaucratic structures may fuel particular behavioural logics among international civil servants. Thus, the study joins a growing body of scholarship that seeks to advance, understand, explain, and theorise the role of IPAs in global politics (Bauer, Knill, and Eckhard Citation2017; Eckhard and Ege Citation2016; Gänzle, Trondal, and Kühn Citation2018; Olsson and Verbeek Citation2018; Federo, Saz-Carranza, and Esteve Citation2020; Tieku, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2020; Riddervold and Trondal Citation2020). These works demonstrate how essential IPAs are for recruitment (Tieku, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2020), buffering external pressures (Debre and Dijkstra Citation2021), mobilising inter- and intra-agency coordination (Mele and Cappellaro Citation2018), serving as sounding boards and agenda setters (Riddervold and Trondal Citation2020; Federo, Saz-Carranza, and Esteve Citation2020).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. The next section embeds our approach in the wider array of different literatures that focus on the autonomy of IOs. We then outline a conceptual and theoretical model in two steps. The following section briefly introduces the data and methods made available to illuminate the multi-dimensional nature of AUC staff. The subsequent empirical section conducts an in-depth analysis of the behavioural logics of AUC officials. The final section concludes by outlining avenues for future studies.

Theorising IPAs: a conceptual typology from an organisation perspective

Modern governments formulate and execute policies with consequences for societies on a daily basis (Hupe and Edwards Citation2012). Governments have become increasingly reliant on IPAs for formulating and executing policies for societies. With the increasing role of IPAs, one unresolved question is to what extent and under what conditions would these IPAs act autonomously or even formulate their own policies and thus transcend their traditional roles of mere servants of governments. Organisational theory can be helpful in this regard in at least two ways. First, it enables us to tease out the role-set at the disposal of international civil servants while allowing us to show that variation in the role-set is driven by mechanisms endogenous to IPAs. Second, organisational theory enables us to theoretically extend the literature on IPAs, which has exhibited a strong bent towards the United Nations and the EU, to include insights from IOs housed in the Global South in general and Africa-based IOs in particular (for exceptions, see Gänzle, Trondal, and Kühn Citation2018 and Murdoch, Gravier, and Gänzle Citation2021).

An organisational approach assumes that bureaucracies possess internal capacities to shape staff through mechanisms such as socialisation (behavioural internalisation through established bureaucratic cultures), discipline (behavioural adaptation through incentive systems) and control (behavioural adaptation through hierarchical control and supervision) (Page Citation1992; Weber Citation1983; Yi-Chong and Weller Citation2004, Citation2008). These mechanisms ensure that bureaucracies perform their tasks relatively independently from outside pressure, but within boundaries set by the legal authority and (political) leadership of which they serve (Weber Citation1924). Causal emphasis is thus put on the internal organisational structures of the bureaucracies.

An organisational approach therefore gives an autonomous role to institutional factors such as hierarchical control and supervision, discipline, and/or bureaucratic cultures (Page Citation1996; Weber Citation1983; Trondal and Peters Citation2013). These factors provide IPAs with their ‘own’ organisational capacities that may routinise the behaviour of IPA staff, ensure that IPAs are isolated from undue outside influences and interferences, and create what Simon (Citation1957, 165) called an ‘organisation man’. Consequently, international civil servants may behave in ways that are primarily created by the IPA in which they are embedded (Olsen Citation2010). In sum, the behavioural logics evoked by international civil servants are expected to be primarily directed by those administrative units that are the primary supplier of relevant decision premises.

Organisations accumulate conflicting organisational principles through horizontal and vertical specialisation, which supplies civil servants with conflicting premises for decision behaviour (Olsen Citation2005). Two organisational variables may systematically foster actor-level roles: organisational vertical and horizontal specialisation (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2018). Organisation can both be distinguished in terms of vertical (for example seniority of staff) and horizontal (for example process versus purpose of tasks) structures (Gulick Citation1937). These structures are likely to systematically bias the role perceptions of organisational members.

Following this argument, organisation theory offers two distinct propositions regarding behavioural logics of IPA staff that are outlined in the following. Both propositions imply that the behavioural logics of international civil servants are mediated by the organisational structure of IPAs.

Proposition (#1) suggests that behavioural logics vary according to the vertical specialisation of IPAs. Staff in higher ranked positions are, we argue, more likely to be supranationally oriented compared to staff in lower ranked positions who are more likely to be departmentally and transnationally minded.

The AUC is a vertically specialised bureaucratic organisation (#1). Vertically specialised bureaucratic organisations have the potential for disciplining and controlling civil servants by administrative command and individual incentive systems like salary, promotion, and rotation (Egeberg Citation2003). Studies show that vertically specialised bureaucracies have stronger influence on incumbents’ behavioural and role perceptions than less vertically specialised bureaucracies (Bennett and Oliver Citation2002, 425; Egeberg Citation2003, 137; Knight Citation1970). One proxy of the vertical specialisation of bureaucratic organisations is the formal rank of personnel. Arguably, officials in different formal ranks are likely to be exposed to different behavioural premises and, subsequently, likely to employ different behaviour and role perceptions. Being organisationally connected to the leadership of IO, officials in top rank positions are more likely to evoke a logic of supranationalism than officials in bottom rank positions. The latter group is more likely to be exposed to sub-unit rules and independent expertise, thus being biased towards departmental and transnational roles (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2018; Mayntz Citation1999, 84).

Proposition (#2) suggests that behavioural logics are likely to vary systematically as a consequence of the horizontal structuring of IPAs. Whereas organisational specialisation according to process may encourage a transnational behavioural logic, organisational specialisation according to purpose is conducive to a departmental behavioural logic.

The AUC is horizontally specialised (#2). A vast majority of AUC departments are administrative support services which are organised according to process, and thus we expect the transnational behavioural logic to be mobilised. Yet, the AUC also hosts policy responsibilities embedded in policy-oriented departments that are thus organised by purpose, and they are expected to be more prone to a departmental behavioural logic. As regards the horizontal specialisation of bureaucratic organisations, department and unit structures are typically specialised according to two conventional principles: purpose and process (Gulick Citation1937; Egeberg and Trondal Citation2018). The first principle is major purpose which encompasses policy themes such as research, health, food safety, etc. This principle of organisation tends to activate behavioural patterns among incumbents along sectoral (portfolio) cleavages (Egeberg Citation2006). Organisation served by major purpose is thus likely to bias behavioural logics towards a departmental logic. This mode of horizontal specialisation results in less than adequate coordination across organisational units and better linkages within organisational units (Ansell Citation2004, 237; Page Citation1996, 10). The AUC department and unit structures serve as prominent examples of this horizontal principle of specialisation. The AUC constitutes a system of ‘government’ which is horizontally organised and specialised according to purpose. This enables units to enjoy relative autonomy vis-à-vis other sub-units and the executive helm (see below).

Data and methods

Studies of IOs and IPA staff are characterised by a case-selection bias that have prioritised cases from the ‘OECD world’ or the UN-system, broadly conceived. This study addresses this void by surveying AUC staff. It thus remedies a biased case-selection which have largely ignored IPAs of non-European IOs because these are deemed fundamentally different for cultural reasons or simply inaccessible ‘black boxes’ with only little delegated authority. Four reasons guide our case selection: First, the AUC broadens the available cases in IPA studies. Secondly, the case serves as a robustness-check on existing IPA literature by gauging the extent to which behavioural dynamics of AUC staff resemble those inside other IPAs (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Biermann and Siebenhuner Citation2009; Trondal and Bauer Citation2017). Thirdly, the AU is relevant as one of the most important and comprehensive political actors in Africa and among IOs (Karbo and Murithi Citation2018; Tieku Citation2018; Witt Citation2019). Finally, the AUC – together with the AU – is the corner stone of continental-level regional integration in Africa, dating back to the early 1960s.

This paper is based on data gathered through mixed research method techniques. First, it benefitted from archival research which uncovered internal documents such as confidential reports, memos, activity reports, meeting notes, and rapporteurs’ reports of closed-door meetings. These materials are kept in different units in the AU system. Some of them are available in the official AU archive, the registry, legal affairs directorate, the office of the Secretary to the AUC while others are kept in the offices where they were produced. In addition, some of the ministries of foreign affairs of AU member-states and embassies of African states in Addis Ababa keep record of AU documents. The absence of a single unit for storing key AU documents means that it not only takes time and good networking skills for researchers to acquire a working understanding of where to find key materials in the AU system, but they need a heavy dose of social trust to gain access to documents that AU officials see as sensitive and/or confidential. In particular, the study draws heavily from the annual activity reports of the African Union Commission, consultancy study on institutional reforms submitted to the Chairperson of the AU Commission (Chairperson) in 2019, reports by the Chairperson to policy organs of the AU and the 2007 institutional audit of the AUC. More crucially, we were fortunate to get hold of two confidential reports on the structure of AUC and its staff that the chairperson of the AUC submitted in May 2020 to Permanent Representative Council of the AU as part of the structural reforms of the AUC. These documents provided comprehensive discussions of the nature of the AUC, departments, AUC staff, and the organisational challenges of the AUC since it was established in 2002 ().

Table 1. Summary and operationalisation of the actor-level typology.

Secondly, the authors were able to launch an online survey inside the AUC collaborating with the African Union Leadership Academy (AULA)–an in-house executive training unit and think tank–covering altogether 137 AUC staff, representing approximately 9 per cent of the total global workforce of the AUC. The survey captures the views of all categories of AU employees, including regular staff, short-term employees, professional staff, and non-professional workers of the AUC. As shows, 53 out of the 137 respondents fall within the junior professional category (P1-3), while 21 of those surveyed are in the senior professional category. To probe further on questions that the online survey was unable to capture, the research team conducted over two dozen open-ended interviews in English with key AUC officials staff categories between June 2019 and February 2020.Footnote1 As the interviewees have been promised anonymity, we can only disclose their ranks and the time of the interview.

Table 2. Distribution of response rate in our survey, by staff categories.

Operationalisation of four behavioural logics

This section operationalises the four behavioural roles-set that international civil servants evoke. An organisational theory approach highlights how the multiple roles evoked by organisation staff may emerge endogenously from inside organisations they work for (Hooghe and Marks Citation2015; Schein Citation1996; Selznick Citation1957). The extant literature suggests that IPA staff evoke four major idealised role-sets namely intergovernmental, supranational, departmental, and transnational behavioural logics (Egeberg Citation2003; Egeberg and Trondal Citation2018; Gänzle, Trondal, and Kühn Citation2018). This conceptual idea is drawn from a long tradition in the study of public administration which argues that civil servants in governing systems tend to balance multiple roles sequentially and/or simultaneously (Olsen Citation2007, Citation2008). The key to understanding public governance is to find out when, where, under what condition(s) would a particular role-set be evoked and the trade-offs that individual staff have to make (Wilson Citation1989, 327). As such, the empirical focus of this study is actor-level autonomy as they relate to how international civil servants evoke any of the four behavioural logics.

The four-fold conceptual typology is unpacked as follows. According to an intergovernmental role, IPA staff are guided by loyalty towards their governments, they have preference for national interests and enjoy close contacts with the home base. The role as civil servants in IOs is considered to be a frontline worker for national government(s) and as loyal Trojan horseswithin IPAs. Such a member state-based role perception stands in sharp contrast to a supranational role perception.

In the supranational role-set, actors have loyalty and allegiance to the IO as a whole (Johnston Citation2001). The staff experience a ‘shift of loyalty’ to IOs, develop a ‘sense of community’ as well as cultivate a shared awareness of common rules, norms, principles, and codes of conduct (Deutsch et al. Citation1957, 5–6; Haas Citation1958, 16). This is consistent with ‘type II socialisation’ put forth by Checkel (Citation2007), whereby actors identify personally with the IPA and IO as a whole.

Third, a departmental role pictures civil servants as neo-Weberian officials that are rule and role players (Olsen Citation2010). They follow rules and roles, but unlike a classic Weberian civil servant they usually think about them in terms of what is good for their department rather than for the organisation as a whole. The departmentally focused official often draws a distinct line between political activities and those that are non-political or non-controversial ones (Trondal et al. Citation2010). Whereas IOs establish ‘rules for the world’ (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004), IPAs establish organised action capacity for the department (Biermann and Siebenhuner Citation2009). Accordingly, departmentally minded civil servants are (boundedly) intelligent professionals who advise their principal(s) based on local organisational rules and routines. We thus expect these civil servants to be guided by administrative silo logics in which intra-organisational communication is weak, resulting in relative isolation of their units from other part of the IPA and/or the IO.

Finally, a transnational role suggests that international civil servants are influenced primarily by professional reference groups and the power of the better scientific argument (Asher Citation1983; Wood Citation2019). International civil servants in this category do their daily work on the basis of their professional competence. Their legitimacy and authority depend on their scientific references, and their role perceptions are guided by considerations of professional and scientific correctness (Marcussen Citation2010). Thus, their role is directed primarily towards own expertise and educational background, as well as towards external professional networks. This is the ‘expert official’ who is institutionally loosely coupled from the IPA and/or considered a high-flying and mobile technocrat (Asher Citation1983; Haas Citation1992).

It is important to emphasise again that these four logics are ideal types. They are established as analytically distinct categories though they are often interconnected. The empirical endeavour is examining the multi-dimensional set of roles and identities evoked by IPA staff in the AUC. Moreover, the typology is empirically measured by eight proxies: Task profiles (), contact patterns (), the concerns and considerations emphasised (), whose arguments are paid attention to when making decisions (), role perceptions (), the origins of AUC proposals (), patterns of conflicts (), and patterns of coordination (). Taken together, this set of proxies serve as a comprehensive measurement of the multi-dimensional behavioural logics of AUC staff. These proxies provide ‘conceptions of reality, standards of assessment, affective ties, and endowments, and […] a capacity for purposeful action’ (March and Olsen Citation1995, 30). In each table, we gauge – albeit cautiously – several proxies taken from the survey against these role types. For example, we interpret the preponderance of each of these proxies within the respondents’ own department to be in line with a departmental behavioural logic (see below).

Table 3. Task profile: Distribution of officials spending much or very much time on the following tasks (Percentages)*.

Table 4. Contact patterns: Distribution of officials having often or very often contacts with the following (percentages)*.

Table 5. Distribution of officials’ perceiving the following considerations and concerns as fairly or very important (percentages)*.

Table 6. Distribution of officials who report the following institutions provide fairly or very important arguments (percentages)*.

Table 7. Role perceptions: Distribution of officials identifying much or very much with following roles (percentages)*.

Table 8. Distribution of officials who very much or much agree that policy proposals reflect the following (percentages)*.

Table 9. Cleavages of conflict: Distribution of officials who much or very much report the following conflicts (percentages)*.

Table 10. Patterns of coordination: Distribution of officials reporting very much or much efficiency in coordination between the following (percentages)*.

The multi-dimensional behavioural logics of the AUC staff

This section proceeds in two steps: The first step provides an overview of the AUC organisational and staff structure. Step two reveals the role-set evoked by AUC officials.

Step I: the AUC organisational architecture

The appointed staff of the AUC are made up of 1,720 officials (as of March 2021) based at the headquarters in Addis Ababa, and at the representative missions around the world (African Union Citation2019). offers a visual representation of the staff structure of the AUC. P1 to D1 are international civil servants appointed into the professional staff category, while the General Service Staff (GSS) are those the AU calls the auxiliary staff. The GSS category is made up of two groups, namely administrative, clerical, maintenance, and paramedical personnel (GSA), and drivers and security personnel (GSB).

Demography studies reveal that the typical AUC staff is middle-aged, highly educated (with a majority of MA- or PhD-level graduates) and educated in the social sciences (Tieku, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2020). 61% (1,043) of the 1,720 AUC workforce are on short-term contracts and a total of 73% (1,261) are lower-ranked officials or in the bottom half of the AUC pay grade (see ). The AUC is organised into six portfolio Departments, 15 Directorates and managed by 6 elected Commissioners (see ).

The grading scale for those in the professional category are: D1 as designation for directors of departments, directorates and the Chief of Staff of the Chairperson; P6 for advisers, mostly in the Bureau of the Chairperson, the Bureau of the Deputy Chairperson and the Deputy Chief of Staff; P5 reserved for heads of the various divisions of the AUC; P4 for primarily interpreters; P3 comprise senior policy officers; P2 policy officers, and P1 are mostly documentalists (Authors’ interview with P4). The AUC operates with 1–10 steps scale at each grade, and a step is given for each year that a staff spends at the AUC. In other words, it takes about 10 years to move from P1 to P2 and so on – pending on the successful passage of a set of examinations (see Tieku, Gänzle, and Trondal Citation2020). Graduation from one step to the next is not automatic but depends on multiple factors including availability of a position at the next level and assessment of a person’s suitability for that position.

The 1,720 appointed staff are housed in departments or directorates, representational offices, or in offices of Special Envoys. As shown below in , there are 6 portfolio Departments each under a commissioner, four Directorates under the Deputy Chairperson, 11 Directorates/offices, Permanent Representational Offices (PRO), and Special Envoys under the Chairperson.

This next section will now turn to the multi-dimensional set of behaviour and roles discernible among AUC personnel.

Step II: the role-set evoked by AUC officials

Multiple proxies assist in building robust probes of the complex nature of AUC governance. To underpin this, outlines the task profile as prioritised by AUC personnel. Three observations can be made. First, the AUC houses a compound set of tasks and activities. Secondly, the AUC thus goes beyond being a mere secretary to the AU. Many respondents report that they usually support the AU and its members in ways that go beyond the provision of technical services, such as providing scientific, drafting policy, and legal advice into areas that may ultimately translate into political influence. For instance, many of the respondents indicate they are very much involved in drafting policy proposals, giving political advice, and facilitating compromises. The claim that AUC staff are not just technical people or ‘diplomats idling around and pushing papers’ came out strongly during interviews. A P5 staff (Author’s interview on June 17, 2019) illustrated the political and policy influence of the AUC staff best when he talked about the ‘Regional Strategy for the Stabilisation, Recovery and Resilience of the Boko Haram-affected Areas of the Lake Chad Basin Region’ (Lake Chad Basin Commission and African Union Commission Citation2018). According to him, this strategy document which is shaping the approach of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria to the menace posed by Boko Haram Islamic terrorists essentially came from the Conflict Management Division.

The ideas came from and were championed by the Division together with the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) and with donor support that the AUC mobilised, the strategy was developed for the affected states to end the scourge of the Boko Haram insurgency in 2018. It is not only the four states that are using the strategy, but you know that the UNDP used it to launch their USD$65 million Regional Stabilisation Facility for Lake Chad. This is not a secret.

Accordingly, the task profile of the AUC is multi-dimensional and not merely compatible with that of a neutral secretariat exclusively occupied with executing technical functions as pictured by an intergovernmental approach. This finding is also consistent with studies that show that the AUC influence political dynamics within African countries and shape African international relations (Tieku Citation2011; Karbo and Murithi Citation2018; Witt Citation2019). Thirdly, the task profile reflects organisational structure in which political tasks are relatively more prominent among higher ranked personnel, whereas technical tasks are more noticeable at the lower echelons. For instance, as shows, while only 22 per cent of P1–3 report they often provide political advice, approximately 47 per cent of P4 and higher indicated they give political advice to member states.

An organisational approach posits that institutional boundaries are likely to affect administrative behaviour. supports this in two ways. First, the vast majority of contacts happens within the confines of the respondent’s own department, illuminating the prominence of departmental behaviour. Contacts are mainly distributed within departments and drops substantially when organisational boundaries are crossed vertically (towards the commissioners) (#1) and horizontally (towards other departments) (#2). Secondly, the impact of organisational structure is displayed by staff categories (#1). Notably, supranationalism and intergovernmentalism features more prominently in the contact patterns among top-ranked staff than among lower ranked personnel. As predicted, staff categories discriminate vertical patterns of contacts towards the administrative leadership in the AUC as well as towards Commissioner(s). Finally, the transnational contact pattern is least frequently reported.

Interviews with AU staff put the culture of working in silos at the AUC down to organisational factors, including the dearth of inter-organisational agencies at the AU, the reporting and incentive structures and the way funding is allocated within the AU system. Staff are contracted to specific departments and directorates, socialised to focus on departmental concerns, and there is a lack of formal inter-agency bodies within the AU system to encourage them to work across departmental lines. Attendance of meetings, events, and missions by AUC staff are strictly by invitation only. As a member of the P5 put it, ‘you can only attend another department’s meetings or missions [only] when you are invited through your commissioner or director. You cannot go in your own capacity. There is no personal invitation in the AUC’ (Author’s interview on November 4, 2021). A P4 staff member (Author’s interview on November 3, 2021) added an interesting angle, pointing out that ‘you attend those meetings and missions as a visitor even though you are in the same organisation. You are required to follow them even if you think you know better’. Both the reporting and incentive structures are designed to make AUC staff focus on departmental and directorate concerns. Evaluations and performance appraisals are departmentally oriented. Thus, the departmental logics becomes intrinsically linked with the officials’ dependence on their superiors within the silo. As much as it provides a shield towards outsiders’ interference it reinforces intra-departmental dependency. A D1 staff member put it this way, ‘the AU headquarters is like a compound house. Your food is served in your home unless you get the odd invitations from others. You will have nothing to eat if you spend precious time in other homes. Your contract and its renewal, especially for the non-regular staff who are the majority, are dependent on what you do in your home not in other people’s homes’ (Author’s interview on October 15, 2021).

While the interviewees agreed that the way the AUC is structured is the primary driver of the silo culture, P3 and P4 staff note that the AUC budgeting process is another major driver of the departmental focus. They explained that every program within a department has a budget line approved by the PRC. Department heads and commissioners are not even allowed to move resources from one budget line to the other within their own departments and directorates unless approval from the PRC is sought through a process called ‘virtment’ (Author’s interview on November 4, 2021). To secure the PRC’s approval for their budget lines during AU budget season and to ensure that they do not reappear before the PRC through the ‘unpleasant “virtment” process’, the focus of directors and commissioners is just on their budget lines. ‘They don’t like to hear anything outside of their department’ (Author’s interview on November 4, 2021). A recently retired AUC staff who participated in PRC budget approval process for more than a decade says that the idea of inter-agency or interdepartmental budget line is not the ‘AU way. You will not get directors and commissioners to go to the PRC to defend that budget line’ (Author’s interview on November 5, 2021). The PRC tough posture during budgeting does not only discourage collaboration between departments and directorates, but it also encourages silo working culture at the AUC. According to him,

the chairperson and commissioners can do whatever they want but not over budget. When it comes to budget, the PRC is the boss. They ask tough questions about every budget line, especially those funded by external partners. They don’t hesitate to ask directors and commissioners to reduce or eliminate budget lines. In Nairobi, they forced the chairperson to reduce his office budget from over $30million to the ceiling of $17million American dollars. Nobody, not even the chairperson, likes to go to the PRC over money issues.

Thus, to avoid PRC’s scrutiny, the AUC staff concentrate on departmental concerns and rarely work across agency lines.

Respondents were asked about the considerations and concerns they emphasise during every-day work. displays three observations. First, a wide variety of considerations and concerns are mobilised beyond those of the member states. This suggests generally that a blend of behavioural logics is at play. Second, intergovernmental concerns are seen as least important – including party-political concerns. Third, staff tend to balance supranational and departmental concerns. Epistemic concerns occupy a third priority. The concerns of their policy sector and overall African concerns are thus equally emphasised. These observations complement existing literature on IPAs which finds that international civil servants are more inclined to adopt supranational and departmental mindsets than intergovernmental ones (Checkel Citation2007; Trondal Citation2016). Finally, vertical specialisation (#1) of staff categories influences these observations, notably making higher ranked officials more departmentally and supranationally minded compared to lower ranked officials.

reports which categories of arguments that AUC staff perceive as important while doing their daily work. The figures suggest that Commission staff are sensitive to multiple arguments but assign most weight to those arriving endogenously from co-workers (H2) or superiors (#1) within the AUC, especially from their own units. It supports how the organisation embedment of staff mobilises a departmental behavioural logic. Comparatively, the intergovernmental and supranational logics score overall equal, yet most prominently among higher than lower ranked officials (#1). In sum, the observations reveal a relative primacy of a departmental behavioural logic, which is influenced by the organisational specialisation of the AUC.

When asked explicitly about their role perception, one prominent observation from is that AUC officials tend to activate multiple roles with the departmental role more pronounced and intergovernmental role least notable. Put differently, respondents thus report viewing themselves primarily as representatives of departments and units within the Commission (#2). Compatible with other studies of IPAs (Bauer, Ege, and Schomaker Citation2019; Trondal et al. Citation2010), AUC staff view themselves secondarily as representatives of the AUC as a whole, and thirdly as independent experts. Finally, given the overly intergovernmental character of the AU as an overall IO, surprisingly, few AUC officials see themselves as representatives of governments of their states. In sum, these observations suggest how role perceptions among AUC staff are endogenously biased by the AUC (1–4).

documents the premises that energise the formation of policy within the AUC. The figures suggest that a blend of supranationalism, departmentalism and intergovernmentalism is at play. Reflecting vertical specialisation and administrative capacities at the helm of the AUC (#1), respondents report that the Commissioner in charge, and his or her political preferences, are influential in shaping Commission proposals, as well as the AUC Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson and the Assembly/Executive Council/PRC/Pan-African Parliament. Intergovernmentalism is perceived as the least influential premise that shapes policy proposals. Moreover, our survey data suggest that a majority of respondents deem influential the political profile/interest of the Commissioner (#1). This is interesting because politicisation often implies increased political scrutiny and control over administrative personnel.

Finally, this study measured cleavages of conflicts within and across the AUC. suggests that conflicts within the AUC are largely organised tensions since they essentially follow organisational boundaries and largely occur within and between AUC departments (#2). also reveals that top ranked officials experience frequent conflicts within their own department and other AU bodies (#1). Reflecting the organisational design of the AUC, tensions are perceived to arise horizontally (#2) and vertically (#1) within the Commission. Thus, cleavages of conflict tend to follow organisational boundaries in which the staff operate largely according to a departmental logic. Moreover, these findings may influence challenges for the heads of the Commission and departments to get the house in order. Studies show that policymaking is generally considered to be driven by dynamics that are endogenous to policy sub-system and that bureaucratic organisations are often rifted by silo logics and policy turfs, hierarchies and resources (Christensen and Laegreid Citation2011; Fernández-i-Marín et al. Citation2022). By contrast, good governance is often portrayed as properly coordinated. suggests that coordination within the AUC overall is perceived as not all good. Only higher ranked staff perceive coordination between the AUC and member states as relatively good (#1). As such, the house of the AUC is observed as disaggregated and in relative disarray by our respondents due to the frequency of in-house patterns of conflict and lack of perceived efficiency in coordination.

Conclusion and implications for future studies

This paper has examined the balancing act which civil servants of the AUC are often compelled to perform during everyday decision-making. This study has outlined a set of four (ideal type) behavioural logics and observed that the departmental behavioural logic dominates AUC decision-making on a day-to-day basis. This logic is followed by supranational and transnational behavioural logics. Most importantly, the intergovernmental logic is much less evoked than one might intuitively assume given the overall intergovernmental design of the AU governance architecture. We draw insights from IPA studies and organisational theory to outline the four-behavioural logics.

We showed that departmental behavioural logic is endogenously generated from the organisational structure of the AUC. By highlighting the role of organisational factors, we have shown that variation in the administrative behaviour of international civil servants is associated with vertical and horizontal specialisation of IPAs, two often neglected variables in the study of international politics in general and IO in particular. The vertical and horizontal specialisation had considerable influence on actor-level behavioural logics (#1 and #2). Moreover, there is no data suggesting that temporary staffed officials with merely part-time affiliation to the AUC are merely intergovernmentally minded. Both regular and short-term contracted staff exhibited similar behavioural logics.

Finally, the study points to several lines of inquiries. First, the findings show that although the AUC is embedded in an intergovernmental governance architecture, the corresponding intergovernmental behavioural logic is often the last to be evoked. The default behavioural logic of AUC staff is departmental. While organisational theory helped us to theorise that the departmental logic is internally generated, it would be interesting to know both in theory and empirics why the intergovernmental behavioural logic is often the last to be evoked given that the AUC was created as an intergovernmental organisation. Second, the findings suggest the IR literature will benefit from data drawn from (ideally) ‘large-N’ and longitudinal studies of the behaviour of international civil servants embedded in small IO secretariats in the world–potentially even allowing for distinguishing between headquarters, agency-level or field operations more broadly. This study has proposed the template and proxies for such a study. Second, drawing on comparative data of IOs across the world to test whether the departmental behavioural logic is just a phenomenon of small IOs and the implications of the siloed behaviour of IO staff for organisational performance and international governance in general. Doing so would not only provide comparable datasets, but also help overcome the ‘Western-liberal’ bias in most of IPA studies thus far and to a larger extent the study of international relations (Acharya and Buzan Citation2019). Third, the findings imply that international civil servants and their IPAs are important, and our understanding of international relations would be greatly enhanced if IR scholars study them in their own rights rather than as a tag along of the study of inter-state politics. The IR discipline can take a cue from the work of scholars who study civil servants at the state level to design a research program that incorporates the causal influence of endogenous IPA variables. Future research can also advance theoretically informed comparative studies of the inner life of IPAs and their wider role in global governance. This study has sought to outline the analytical basis for such endeavours.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Kwasi Tieku

Thomas Kwasi Tieku is an Associate Professor of Political Science in King’s University College at The University of Western Ontario (UWO) and a former Director of African Studies at the University of Toronto where he won the Excellence of Teaching Award. He is also an award-winning author. His latest co-edited book is The Politics of Peacebuilding in Africa (Routledge, 2022). His current research, which is supported by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), focuses on informal international relations, mediation, and international organisations, especially the African Union and the UN. Email: [email protected]

Jarle Trondal

Jarle Trondal is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo, ARENA Centre for European Studies, Norway, Professor at the University of Agder, Department of Political Science and Management, Norway, and a Senior Fellow at University of California, Berkeley, US.

Stefan Gänzle

Stefan Gänzle is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science and Management, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway.

Notes

1 In response to reviewers’ suggestions for cross-checking why AUC staff usually evokes the departmental logic more often, a member of the research team conducted virtual interviews between October 25, 2021 and November 4, 2021 with five purposively selected AUC staff drawn from the P1-P3, P5, D1 staff categories, and a former AUC staff who worked for the AUC since it was created in 2002 until retirement in 2020.

References

- Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. 2019. The Making of Global International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- African Union. 2019. “Restructuring the African Union Commission.” Report of the Chairperson of the African Union (AU) Commission to the PRC Sub-Committee on Structural Reforms on a Proposed Departmental Structure for the AU Commission Pursuant to Assembly Decision Ext/Assembly/AU/Dec.1–4(XI). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, May 27, 2019.

- Ansell, Christopher K. 2004. “Territoriality, Authority and Democracy.” In Restructuring Territoriality, edited by Christopher K. Ansell and Giuseppe Di Palma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Asher, William. 1983. “New Development Approaches and the Adaptability of International Agencies: The Case of the World Bank.” International Organization 37 (3): 415–439.

- Ayebare, Adonia. 2018. “The Africa Group at the United Nations: Pan-Africanism on the Retreat.” In The African Union, edited by Tony Karbo and Tim Murithi. New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Barnett, Michael, and Martha Finnemore. 2004. Rules for the World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bauer, Michael W., Christoph Knill, and Steffen Eckhard, eds. 2017. International Bureaucracy. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bauer, Michael. W., Jörn Ege, and Rahel Schomaker. 2019. “The Challenge of Administrative Internationalization: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead.” International Journal of Public Administration 42 (11): 904–917.

- Bennett, A. Leroy, and James K. Oliver. 2002. International Organizations. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Benz, Arthur, and Klaus Goetz. 2021. “Tents, Not Palaces: International Politics and Administrative Organization.” Paper Presented at the Online Conference “International Public Administrations: Global Public Policy between Technocracy and Democracy, Centre for Advanced Studies, LMU Munich, 18–19 March 2021.

- Beyers, Jan. 2010. “Conceptual and Methodological Challenges in the Study of European Socialization.” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (6): 909–920.

- Biermann, Frank and Bernd Siebenhuner. 2009. Managers of Global Change. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Biermann, Frank, and Bernd Siebenhuner. 2013. “Problem Solving by International Bureaucracies: The Influence of International Secretariats on World Politics.” In Routledge Handbook of International Organization, edited byBob Reinalda. London and New York: Routledge.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline Anne. 2009. Institutions of the Global South. London: Routledge.

- Checkel, Jeffrey T., 2007. ed International Institutions and Socialization in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Laegreid. 2011. “Complexity and Hybrid Public Administration—Theoretical and Empirical Challenges.” Public Organization Review 11 (4): 407–423.

- Clapham, Christopher. 1996. Africa and the International System: The Politics of State Survival. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coe, Brooke N. 2019. Sovereignty in the South: Intrusive Regionalism in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cox, Robert W., and Harold K. Jacobson. 1973. The Anatomy of Influence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Debre, Maria J., and Hylke Dijkstra. 2021. “Institutional Design for a Post-Liberal Order: Why Some International Organizations Live Longer than Others.” European Journal of International Relations 27 (1): 311–339.

- Deutsch, Karl W., Sidney A. Burrell, Robert A. Kann, Maurice Lee, Jr., Martin Lichterman, Raymond E. Lindgren, Francis L. Loewenheim, and Richard W. Van Wagenen. 1957. “Political Community and the North Atlantic Area.” In The European Union: Readings on the Theory and Practice of European Integration, edited by Brent F. Nelsen and Alexander Stubb. Boulder, CO; London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Eckhard, Steffen, and Hylke Dijkstra. 2017. “Contested Implementation: The Unilateral Influence of Member States on Peacebuilding Policy in Kosovo.” Global Policy 8: 102–112.

- Eckhard, Steffen, and Jörn Ege. 2016. “International Bureaucracies and Their Influence on Policy-Making: A Review of Empirical Evidence.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 960–978.

- Ege, Jörn. 2020. “What International Bureaucrats (Really) Want: Administrative Preferences in International Organization Research.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 26 (4): 577–600.

- Egeberg, Morten. 2003. “How Bureaucratic Structure Matters: An Organizational Perspective.” In Handbook of Public Administration, edited by B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre, 77–87. London: SAGE.

- Egeberg, Morten. 2006. Multilevel Union Administration. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Egeberg, Morten, and Jarle Trondal. 2009. “National Agencies in the European Administrative Space: Government Driven, Commission Driven, or Networked?” Public Administration 87 (4): 779–790.

- Egeberg, Morten, and Jarle Trondal. 2018. An Organizational Approach to Public Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Federo, Ryan, Angel Saz-Carranza, and Marc Esteve. 2020. Management and Governance of Intergovernmental Organizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fernández-i-Marín, Xavier, Steffen Hurka, Christoph Knill, and Yves Steinebach. 2022. “Systemic Dynamics of Policy Change: Overcoming Some Blind Spots of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory.” Policy Studies Journal 50 (3): 527–552.

- Fleischer, Julia, and Nina Reiners. 2021. “Connecting International Relations and Public Administration: Toward a Joint Research Agenda for the Study of International Bureaucracy.” International Studies Review 23 (4): 1230–1247.

- Gänzle, Stefan, Jarle Trondal, and Nadja. S. B. Kühn. 2018. “Not so Different after All’”: Governance and Behavioral Dynamics in the Commission of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).” Journal of International Organisation Studies 9 (1): 79–96.

- Gulick, L. 1937. “Notes on the Theory of Organizations. With Special References to Government in the United States.” In Papers on the Science of Administration, edited by L. Gulick and L. F. Urwick. New York: Institute of Public Administration, Columbia University.

- Haas, Ernst. 1958. The Uniting of Europe. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Haas, Peter. M. 1992. “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination.” International Organization 46 (1): 1–35.

- Hawkins, Darren G., David A. Lake, Daniel L. Nielsen, and Michael J. Tierney, editors. 2006. Delegation and Agency in International Organizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2015. “Delegating and Pooling in International Organizations.” The Review of International Organizations 10 (3): 305–328.

- Hupe, Peter, and Andrew Edwards. 2012. “The Accountability of Power: Democracy and Governance in Modern Times.” European Political Science Review 4 (2): 177–194.

- Johnston, Alastair Iain. 2001. “Treating International Institutions as Social Environments.” International Studies Quarterly 45 (4): 487–515.

- Jörgens, Helge, Nina Kolleck, and Barbara Saerbeck. 2016. “Exploring the Hidden Influence of International Treaty Secretariats: Using Social Network Analysis to Analyse the Twitter Debate on the ‘Lima Work Programme on Gender.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 979–998.

- Karbo, Tony, and Tim Murithi. 2018. The African Union: Autocracy, Diplomacy and Peacebuilding in Africa. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Knight, Jonathan. 1970. “On the Influence of the Secretary-General: Can we Know What It is?” International Organization 24 (3): 594–600.

- Lake Chad Basin Commission and African Union Commission. 2018. “Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery and Resilience of the Boko Haram-Affected Areas of the Lake Chad Basin Region.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/rss-ab-vers-en.pdf.

- March, James. G, and Johan. P. Olsen. 1995. Democratic Governance. New York: The Free Press.

- Marcussen, Martin. 2010. “Scientization.” In Ashgate Research Companion to New Public Management, edited by Tom Christensen and Per Laegreid. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Mayntz, Renate. 1999. “Organizations, Agents and Representatives.” In Organizing Political Institutions, edited by Morten Egeberg and Per Laegreid. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

- Mele, Valentina, and Giulia Cappellaro. 2018. “Cross-Level Coordination among International Organizations: Dilemmas and Practices.” Public Administration 96 (4): 736–752.

- Moravcsik, Andrew. 1999. “A New Statecraft? Supranational Entrepreneurs and International Cooperation.” International Organization 53 (2): 267–306.

- Murdoch, Zuzana, Magali Gravier, and Stefan Gänzle. 2021. “International Public Administration on the Tip of the Tongue: language as a Feature of Representative Bureaucracy in the Economic Community of West African States.” International Review of Administrative Science

- Nair, Deepak. 2020. “Emotional Labor and the Power of International Bureaucrats.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (3): 573–587.

- Olsen, Johan P. 2007. Europe in Search of Political Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Olsen, Johan P. 2008. “The Ups and Downs of Bureaucratic Organization.” Annual Review of Political Science 11 (1): 13–37.

- Olsen, Johan P. 2010. Governing through Institution Building. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Olsen, Johan P. 2005. “Unity and Diversity – European Style.” ARENA working paper 24.

- Olsson, Eva-Karin, and Bertjan Verbeek. 2018. “International Organisations and Crisis Management: Do Crises Enable or Constrain IO Autonomy?” Journal of International Relations and Development 21 (2): 275–299.

- Page, Edward C. 1992. Political Authority and Bureaucratic Power. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Page, Edward C. 1996. People Who Run Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Reinalda, Bob. 2013. “International Organization as a Field of Research since 1910.” In Routledge Handbook of International Organization, edited byBob Reinalda. London and New York: Routledge.

- Riddervold, Marianne, and Jarle Trondal. 2020. “The Commission’s Informal Agenda-Setting in the CFSP. Agenda Leadership, Coalition-Building, and Community Framing.” Comparative European Politics 18 (6): 944–962.

- Schein, Edgar. H. 1996. “Culture: The Missing Concept in Organization Studies.” Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (2): 229–240.

- Selznick, Philip. 1957. Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. New York: Harper & Row.

- Simon, Herbert. 1957. Administrative Behavior. New York: Macmillan.

- Söderbaum, Fredrik. 2004. The Political Economy of Regionalism: The Case of Southern Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Söderbaum, Fredrik. 2016. “Old, New, and Comparative Regionalism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism, 16–41. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Souaré, Issake. K. 2018. “The anti-Coup Norm.” In African Actors in International Security: shaping Contemporary Norm, edited by Katharina P. Coleman and Thomas K. Tieku. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Stone, Diane and Kim Moloney, eds. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Global Policy and Transnational Administration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tieku, Thomas. K. 2011. “The Evolution of the African Union Commission and Africrats: drivers of African Regionalism.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Regionalism, edited by Timothy M. Shaw, J. Andrew Grant, and Scarlett Cornelissen. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Tieku, Thomas. K. 2018. Governing Africa: 3D Analysis of the African Union’s Performance. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Tieku, Thomas. K. 2021. “Punching above Weight: How the African Union Commission Exercises Agency in Politics.” Africa Spectrum 56 (3): 254–273.

- Tieku, Thomas. K., Stefan Gänzle, and Jarle Trondal. 2020. “People Who Run African Affairs. Staffing and Recruitment the African Union Commission.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 58 (3): 461–481.

- Trondal, Jarle. 2013. “International Bureaucracy: Organizational Structure and Behavioural Implications.” In Routledge Handbook of International Organization, edited byBob Reinalda. London and New York: Routledge.

- Trondal, Jarle. 2016. “Advances to the Study of International Public Administration.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 1097–1108.

- Trondal, Jarle, and Michael. W. Bauer. 2017. “Conceptualizing the European Multilevel Administrative Order: capturing Variation in the European Administrative System.” European Political Science Review 9 (1): 73–94.

- Trondal, Jarle, Martin Marcussen, Torbjörn Larsson, and Frode Veggeland. 2010. Unpacking International Organisations. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Trondal, Jarle, and B. Guy Peters. 2013. “The Rise of European Administrative Space. Lessons Learned.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (2): 295–307.

- Verhoest, Koen, Paul. G. Roness, Bram Verschuere, Kristin Rubecksen, and Muiris MacCarthaigh. 2010. Autonomy and Control of State Agencies. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weber, Max. 1924. “Legitimate Authority and Bureaucracy.” In Organization Theory, edited by Derek Salman Pugh. London: Penguin Books.

- Weber, Max. 1983. On Capitalism, Bureaucracy and Religion. Glasgow: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Welz, Martin. 2020. “Reconsidering Lock-in Effects and Benefits from Delegation: The African Union’s Relations with Its Member States through a Principal–Agent Perspective.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 33 (2): 159–178.

- Wilson, James Q. 1989. Bureaucracy. New York: Basic Books.

- Witt, Antonia. 2019. “Where Regional Norms Matter. Contestation and the Domestic Impact of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.” Africa Spectrum 54 (2): 106–126.

- Wood, Matthew. 2019. Hyper-Active Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yi-Chong, Xu, and Patrich Weller. 2004. “The Governance of World Trade.” International Civil Servants and the GATT/WTO. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Yi-Chong, Xu, and Patrich Weller. 2008. “To Be, but Not to Be Seen: Exploring the Impact of Civil Servants.” Public Administration 86 (1): 35–51.