Abstract

The past decade has seen a growing interest in the ‘turn to history’ which has coincided with a counter-reading of the archive as a means to trouble contemporary practices of governance. In this article, I explore what a decolonial feminist approach to the colonial archive can look like through the development of a research method that involves counter-mapping. This method included the use of participatory interviews, carried out between 2019–2020, that involved asking interviewees to annotate colonial maps of Cairo, and the co-creation of an alternative map. This method presented a decolonial space where I, the researcher, and the participants, co-investigated the spatial securitisation of urban sites as ‘security threats’ and ‘dangerous communities’. In doing so, we co-examined how certain security ‘truths’ constructed by the colonial archive transcend the colonial/modern continuum in new postcolonial forms of securitisation in Egypt. Securitised spaces on the map were, instead, reimagined as spaces of emancipation and life. At the same time, the gendered differences between participants also point to the coloniality of gender in Egypt. In light of this, I thereby also discuss the troubles of representative methods, and the need for an intersectional feminist approach to decolonial research methods.

Introduction

Over the past decade there has been a growing interest in what is known as the ‘turn to history’ across the Humanities and Social Sciences broadly, and within the disciplines of International Politics and International Law in particular. Genealogical studies into the ‘colonial present’ of contemporary state practices have subsequently blossomed. Much of this scholarship is influenced by Foucault’s processes of ‘descent’ and ‘emergence’, that speak to the ‘troublesome associations and lineages’ underpinning contemporary practices and institutions (Garland Citation2014, 372). Scholars explain that a genealogical approach is not simply a useful method to interrogate contemporary hegemonic narratives but is a necessary and potentially transformative challenge to some of the most violent global phenomena (Stoler, McGranahan, and Perdue Citation2007). Critical historical approaches destabilise Eurocentric narratives of the vulnerable white western subject, exposing colonial histories, not as traces of the past, but as durable structures and processes that ‘cling to the present’ (Abourahme Citation2018, 106).

However, there are methodological challenges associated with the interrogation of the colonial archive as a source of data. Colonial presents are notoriously difficult to trace because, as Stoler (Citation2016, 4) notes, ‘they do not have a life of their own: instead they work to shape logics of governance through racial distinctions, dwelling in the slippery realms of affect’. This is not least because a genealogy configures ‘as neither smooth and seamless continuity (an eternal colonial present) nor abrupt epochal break (a stagist overcoming), but the protracted temporality and uneven sedimentation of colonial practice’ (Abourahme Citation2018, 107). The challenge, then, is: ‘how to recognise a simultaneity of different histories while not subsuming them into a commensurable spatial and temporal moment of encounter?’ (Gunaratnam and Hamilton Citation2017, 4). This dilemma is particularly relevant when it comes to decolonial methods given that the colonial archive has been produced largely in the voice of the coloniser, making it difficult to read the colonial archive through a decolonial lens. Given these insights, in this article I ask: how can we read the colonial archive in a way that centres decolonial truths?

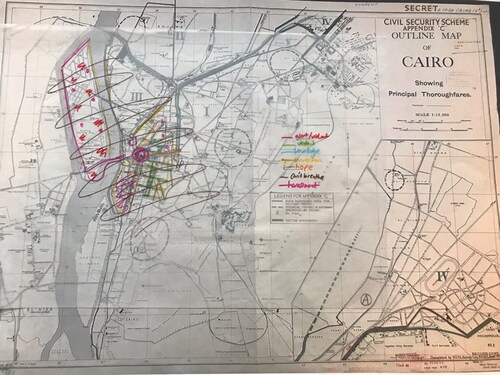

This article adds to these methodological debates through the development and presentation of a participant-centred, decolonial feminist archival method. This method involved inviting participants to annotate and ‘counter-map’ a British colonial map taken from the British Library archives. The context of this methodological inquiry is research I carried out between 2019–2021 which investigated the persistent colonial logics in present-day British and Egyptian countering terrorism and security practice and how these are formed through race, gender, sexuality and class dynamics. My participants, all of whom were Egyptian, were asked to use the colonial map to think about the history of law and policing in Egypt and their own experiences of law and violence in Cairo today. Participants were provided with colourful pens, pencils and tracing paper and asked to draw their own experiences of the city of Cairo on top of the colonial map. This process presented a method to trace the continuities of colonial discursive and constitutive violence and the refashioning of such violence through forms of state security practice in Egypt. This, as I argue in more detail below, provides a visual representation of the colonial/modern continuum that underscores the postcolonial spatial securitisation of racialised, gendered and classed communities in the urban centres of Egypt.

The counter-mapping process presented a generative space for new knowledge to emerge from marginalised subject positions, illustrating the decolonial potential and feminist underpinnings of such methods. This method is feminist not only because it takes an intersectional approach to colonialism and coloniality as the fusion of technologies of race, gender, sexuality and class, but also because it centres the registers of the everyday and the affective. These are spaces and levels that feminist work in particular examines, exposing the regulation of hidden, intimate relations and everyday and private spaces as central in the production of colonial power, but also as key yet forgotten spaces of decolonial resistance (Lugones Citation2007, Citation2010). Participants added alternative ontological and affective forms of knowledge on top of the colonial map and, in so doing, interrogated colonial truth claims, presenting alternative truths in terms of the state construction of ‘threat’. However, there was a clear gender distinction between what was experienced by those who identified as women and those who identified as men. The level of gender-based violence towards feminised and gender non-conforming communities in Egypt is so pervasive that it prevented women from reconceptualising the space in the same way as men.Footnote1 This, I argue, speaks to both the coloniality of gender in present-day Egypt but also to the risks of counter-mapping in that representations of gendered violence can be easily used to bolster the spatial securitisation of classed and racialised communities. Given these insights, I therefore note the necessity of a feminist approach to decolonial counter-mapping and to exploring archival ‘truths’ that likewise centres intersectionality. This article, therefore, presents a new decolonial and feminist method that adds methodological and conceptual insights to the broader discipline of International Politics and the subfields of Decolonial Studies and Gender Studies.

I begin, through an engagement with the existing literature, by outlining the possibilities and methodological considerations of decolonial feminist research methods and counter-mapping as a decolonial praxis. Second, I discuss my own development of this counter-mapping method. Third, I present the security ‘truths’ about Egypt that are constructed through the colonial archive and one colonial map in particular: the map from the British archives I used in my counter-mapping exercise. Fourth, I discuss my findings, including the potential for such methods to interrogate colonial truths and the forms of colonial continuity and rupture in postcolonial Egypt that they highlight. Finally, I reflect on the coloniality of gender and the need for intersectional feminism when undertaking decolonial praxis.

Counter-mapping the colonial archive

The colonial archive presents researchers with an invaluable resource to rethink contemporary narratives of truth, exposing how many of the conditions of contemporary global politics ‘are intimately tied to imperial effects and shaped by the distribution of demands, priorities, containments, and coercions of imperial formations’ (Stoler Citation2016, 3). However, archives, as ‘hegemonic instruments of the state’ (Zeitlyn Citation2012, 462), perpetuate unnuanced colonial fantasies of Empire at its pinnacle and present a form of ‘truth’ that, in its totalising and universal form, can be easy to reify and difficult to think past. State archives and the administrative practices involved in archiving hold the power to construct histories and origin stories, and thus, to whitewash the violent pasts (and presents) of contemporary institutions and practices (Garland Citation2014, 372; Ghaddar and Caswell Citation2019). Furthermore, as researchers, we are implicated in the reproduction of hegemonic narratives of security through our bodily encounters with archival spaces (Chukwuma Citation2022).

The colonial map is part of this larger architecture of colonial truth-making; these maps being produced through archiving practices whereby the continuous publishing of security documents occurred with the aim of foreclosing the freedoms of colonised communities (Stoler Citation2010). Colonial geographical imaginaries of central Africa as ‘conceptually empty’ spaces (Yao Citation2022), for example, provided a justification for occupation and colonisation, but also for the implementation of new security practices that sought to protect the Empire all the while ‘rescuing’ colonised communities from ‘immorality’ (Amar Citation2013). Counter-insurgency practices such as the separation and enclosure of colonised communities, furthermore, produced new subjectivities such as the ‘insurgent’ and the ‘extremist’ (Doty Citation1996; Khalili Citation2013; Sen Citation2022) as ‘threats’ to the stability of Empire (Nijjar Citation2018; Singh Citation2012). The colonial archive is littered with references to such subjects, and so too, is the colonial map, which works to ‘fix’ the spatial and temporal existence of ‘threatening’ communities. Given this, it becomes clear that the colonial map is an epistemic and political tool, one that highlights geographical areas of ‘concern’, being deeply implicated in surveillance and monitoring (Tazzioli and Garelli Citation2019).

Archiving, when understood as a process of creating a totalising truth, becomes a prime location for the evolution of epistemic and cultural forms of control that decolonial scholar Quijano (Citation2007) termed the ‘coloniality of power’. Coloniality refers to systems of power that rely upon the repression and re-writing of Indigenous modes of knowing and the reformulation of cultures and societies along a European universal blueprint (Quijano Citation2007). These systems of power transcend the supposed colonial/modern binary through the production of ‘rational’, ‘civilised’ and ‘moral’ subjects, who exist within cultural, societal, governmental and legal structures bound to European norms. The production of colonial/modern truths alter and come to constitute the lives, experiences and knowledge systems of colonised communities (Quijano Citation2007; Mignolo Citation2000, Citation2009) and work upon racialised, classed and gendered logics that are naturalised into a ‘worldwide system of power’ (Lugones Citation2007, 188). Mignolo (Citation2009, 112) has conceptualised coloniality as, by extension, the ‘darker side of globalisation’ whereby the cosmopolitan ideal of an inclusive global community is premised upon the inclusion of the colonised on the condition that they be disciplined and reformed through European norms.

This paradigm constructs the European subject as bearer of ‘reason’ and ‘knowledge’ in relation to its ‘other’ which was invariably ‘totally absent; or… present, only in an “objectivised” mode’ (Quijano Citation2007, 173). Such truths were produced through imperial scientific and anthropological research and archiving practices that ‘represented the Other to a general audience back in Europe which became fixed in the milieu of cultural ideas’ (Smith Citation2012, 8), and continues to define the epistemic hierarchy of the Euro-American academy today that views Indigenous and Black knowledge as non-existent, informal and untruthful (Hill Collins Citation2002). Indeed, when we encounter the colonial archive, the ‘radical absence’ (Quijano Citation2007, 173) of the colonised is overwhelmingly loud. When colonial subjects are represented, ‘the stories that exist are not about them, but rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives, transformed them into commodities and corpses…’ (Hartman Citation2008, 2).

However, as Esmeir (Citation2012) explores in her account of colonial Egypt, there is an important difference to be made between discursive violence and constitutive violence. This distinction has implications for how we, as researchers, approach the power of the archive and the permeability of colonial truth. Examining Fanon’s account of violence, Esmeir (Citation2012, 6–8) explains that Fanon distinguishes between the coloniser’s creation of the narrative of the colonised as ‘dehumanised’ (discursive violence) and the endowment of this narrative with constitutive force (constitutive violence), making it clear that this vocabulary is not constitutive: there exists a ‘moment of realisation’, after which ‘he [the colonised] knows that he is not an animal’ (Fanon Citation1963, 35, cited in Esmeir Citation2012, 7). For Esmeir, the two will exist at the same time throughout processes of resistance: ‘the insistence on one’s humanity in the first instance is an act of resistance that struggles against that which attempts, but never succeeds, to dehumanise’ (Esmeir Citation2012, 7). Similarly, while for Quijano (Citation2007) the idea of the ‘totality’ at first suggests the all-encompassing nature of colonial truth, both on the level of the discursive and the constitutive, the possibility of a decolonial logic is found in the necessity of ‘difference’ that underpins the very foundations of colonial truth. Arondekar (Citation2005, 12) explains that the challenge of the archive, therefore, is to ‘juxtapose productively the archive’s fiction-effects (the archive as a system of representation) alongside its truth-effects (the archive as material with ‘real’ consequences), as both antagonistic and co-constitutive’. In this sense, a decolonial approach notes the limitations of colonial power and provides a starting point to pick apart archival truths. How in practice can we as researchers examine forms of coloniality without simplifying and reifying the discursive ‘truths’ of the colonial archive? And how can research, a practice that has been built upon colonial objectification of Indigenous communities, become a transformative praxis?

Scholars of Critical Geography Studies look to the disruptive potential of counter-mapping practices that provide interlocutors with the tools to address silences of the colonial archive and to interrogate the truths these maps claim (Yao Citation2022; Boatcă Citation2021; Lobo-Guerrero, Lo Presti, and dos Reis Citation2021). Boatcă (Citation2021, 245) explains that counter-mapping ‘unsettles and unpacks the spatial assumptions upon which maps are crafted and that trouble the spatial and temporal fixes of a state-based gaze’. Counter-mapping practices therefore posit the colonial archive and the colonial map as not so much reflecting the reality of colonial borders but instead as the desired outcomes of imperial administrators (Stoler, McGranahan and Perdue, Citation2007, 9). Maps, as visual objects are also spaces of possibility and reimagination, in a decolonial vein, or as Lobo-Guerrero, Lo Presti, and dos Reis (Citation2021, 7) put it, of ‘connectivity’. Reading between the contour lines we can see changeable stories of a broader Empire and hints of revolutionary challenges. Attending to colonial maps, therefore, provides researchers with opportunities to engage with the ‘unstable politics of representation’ lying underneath (Lobo-Guerrero, Lo Presti, and dos Reis Citation2021, 7).

Counter-mapping is a praxis that has decolonial characteristics through its provision of space to marginalised communities to interrogate colonial truths and to rewrite global hierarchies that endure ‘at the level of both lived experience and social scientific production’ (Boatcă Citation2021, 250). For Mignolo (Citation2009, 125) a decolonial project is one that is located at the ‘margins’ or, ‘places, histories, and people whom non-being Christian and secular Europeans, without dwelling in that particular history, were forced to deal with it’. Such projects are where ‘silenced and marginalised voices are bringing themselves into the conversation’, providing space for ‘the transformation of the hegemonic imaginary’ (Mignolo Citation2000, 736). Decolonial counter-mapping is therefore an ‘epistemic approach’ (Tazzioli and Garelli Citation2019, 398) that locates power and knowledge with non-Western research participants, challenging the researcher/researched binary, providing participants with a means to refuse the totalising effects of coloniality and to generate new hopeful futurities (Mignolo Citation2000). Co-creating counter-maps alongside research participants can provide space to reconfigure the discursive and constitutive ‘truths’ found in the colonial archive and to investigate forms of persistence and resistance in the present day. These approaches are powerful; not only because they provide forms of resistance to colonial truths and discourses, but also because they locate knowledge within the traditions and cultures of colonised communities that have been rendered ‘irrational’ and the object of western anthropological study (Lorde [1984] Citation2007; Moraga Citation1983; Smith Citation2012). For instance, Smith (Citation2012, 8) notes how decolonial methods provide Indigenous researchers with ways to ‘research a recovery of ourselves, an analysis of colonialism, and struggle for self-determination’.

Feminist work on colonial archives, coloniality, and decoloniality notes the systematic erasure of gendered and queer histories according to a colonial hierarchy of rationality and civilisation (Arondekar Citation2005; Lugones Citation2007, Citation2010; Hartman Citation2008). Yet, feminist work and the importance of an intersectional feminist lens is very often side-lined, even within postcolonial and decolonial scholarship, as both Lugones (Citation2007) and Yegenoglu (Citation1998) find in their critiques of Quijano (Citation2007) and Said ([1978] Citation2003). Lugones (Citation2007, Citation2010) describes a ‘coloniality of gender’ as the imposition of a system of gender difference in which forms of morality and practices of reproduction and sexuality are imposed upon colonised communities. Lugones (Citation2007) also understands that the process of rendering a subject as non-existent within the archive, such as the history and existence of the ‘colonised woman’, is directly connected to the colonial separation of categories of race, gender and class. When gender and race are rendered distinct logics, violence against women of colour, for example, cannot be seen (Crenshaw Citation1991). Intersectional feminism accounts for this erasure and exposes what is hidden at these traditionally marginalised junctures.

Feminist work, by understanding gender as much more than simply relating to categories of ‘women’ or ‘men’, but instead as an entire system of regulation that both erases non-western practices of gender and sexuality, and enforces ‘legitimate’ and ‘acceptable’ means of labour, family life and public space, helps us pay attention to the lesser viewed ‘distribution of social and political vulnerabilities’ (Stoler Citation2016, 308) and the resulting legitimisation of the regulation of spaces of intimacy and privacy. By paying attention to the more intimate spaces of the everyday, as the work of feminists like Lugones (Citation2007, Citation2010), Arondekar (Citation2005), and Hartman (Citation2008) does, decolonial feminist approaches provide a holistic picture of the subtle mechanisms of colonial power through intersecting technologies of gender, race and class. By focusing on the realms of affect and emotion – sites of knowledge that have traditionally been gendered and thereby undervalued – a space to examine the persistence of and resistance to forms of discursive and constitutive violence is provided. In other words, emotions can expose not only how coloniality reshapes postcolonial subjectivities but can also speak to the ‘unpredictable autonomy of the body’s encounter with the event, its shattering ability to go its own way’ and thus, internal forms of resistance to normativity (Hemmings Citation2005, 552) and the ‘truths’ of the colonial archive. Resistance here is understood as a psychic process that is ‘emotionally invested in racial survival because it is the glue that makes political communities’ (Georgis Citation2013, 19). Hartman (Citation2008, 11) carries out this work by reframing silences and erasures of the colonial archive into the conditional tense of ‘what could have been’. This method, termed by Hartman as ‘critical fabulation’, rearranges the basic elements of the story found in the colonial archive to throw ‘into crisis “what happened when”’ (Hartman Citation2008, 13). Hartman’s conditional rendering of the silences of the archives opens up space for possible stories of intimacy that can be read across time, and into hopeful futurities.

Methodologically, Black queer feminist praxis has been central in the recognition of art and poetry and creativity as legitimate forms of intellectual thought and theory (Lorde [1984] Citation2007; Lugones Citation2007, Citation2010; Moraga Citation1983). This body of thought has also been central in highlighting the importance of non-traditional registers, such as emotions, as spaces from which regulation but also resistance take flight (Ahmed Citation2004). Feminist counter-mapping with sensory and emotive questions in mind, therefore, can produce alternative stories of resistance to colonial truths. For the Disembodied Territories group, a project that re-maps coloniality across Africa, this praxis:

gestures towards a break from dominant and Eurocentric notions of bio-determined place and time, centring instead place-making as imaginings of what an African space can feel, look, smell, sound, and be like… We ask how we might subvert or transcend this violent past and present to instead centre ideas of space imagined otherwise. (Disembodied Territories Citation2023)

However, there are also risks to such an approach. When a counter-map is constructed by participants, the imagery represented there can be picked up to help bolster imperial frames of racialised populations as ‘closer to’ certain forms of violence, as shown by Grove (Citation2015). As she notes, some examples of counter-mapping have even reproduced the same geographical security paradigms as the state, thus bolstering state-led and international calls for intervention into poorer neighbourhoods. Furthermore, the investment in research as a decolonial site remains a contentious issue because of its colonial and Eurocentric paradigms, the risks of assimilating Indigenous knowledge into the Eurocentric universal and glossing over core differences in ways of knowing and being (Khan Citation2021; Smith Citation2012; Thambinathan and Kinsella Citation2021). As a white British researcher, I am keenly aware that I cannot presume to reinterpret or transform colonial ‘truths’ from the perspective of subaltern or formerly colonised subjects, and indeed, that this practice could lead to a projection of desired research outcomes from my own perspective. As Hartman (Citation2008, 8) notes, ‘the loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them’, and the possibility for the researcher to project their imagined story onto archival silences. This is particularly poignant to remember when researching on an area of the world that has been the fetishised object of orientalist study.

Following the scholarship of Quijano (Citation2007) and others, this article, then, understands the colonial archive (and colonial map) as a structure that signifies the totality of coloniality. However, while coloniality thrives upon the erasure and rewriting of Indigenous and colonised forms of knowledge – including logics of gender, race and class – there is a difference between discursive and constitutive violence, as Fanon understood it, where we can distinguish between the archive as producing a discursive truth and a constitutive truth. It is this difference that provides the opportunity for a decolonial reinterpretation of hegemonic, colonial truth, as a decolonial approach opens space for refusal and reinterpretation. Furthermore, taking not only a decolonial but a feminist approach guides us to listen to intersectional stories, intimate spaces and emotional registers that are important yet often forgotten areas of regulation and resistance. As I show, counter-mapping can hold these decolonial and feminist approaches together as a means to reinterpret histories of International Politics.

The counter-mapping method

Counter-mapping as a collaborative process between myself and my participants provided a space for active listening on my part ‘as a demonstration of resistance’ (Thambinathan and Kinsella Citation2021, 4) and of solidarity and space to my participants to examine and re-interpret the ‘truths’ of their own past, to reimagine what ‘could have been’ and therefore, the spaces of potential decolonial freedoms in Cairo. The ‘truth’ narratives that I was particularly interested in interrogating related to security ‘threats’ and forms of anticolonial ‘insurgency’. I brought a British colonial map of Cairo to my interviews and asked my participants to use it to think about the history of law and policing in Egypt and their own experiences of law and violence in Cairo today. The map was a British military map of Cairo drawn in 1942, accessible from the British Library (see picture in next section) (Maps Citation1942). Participants were presented with tracing paper, colourful pens and pencils and were asked to remap the colonial document according to their own experiences and emotions attached to the city. The reasoning for investigating the Cairo case in particular was that the Egyptian experience of colonialism has been the subject of debate between those who argue that Egypt had a much less formalised and totalising experience of British colonialism (Brown Citation1990, Citation1995; Ezzat Citation2020; Fahmy Citation2012) and those who that hold that British colonial processes of legal and secular reform produced Egyptian modern identities, tying them to European liberal frameworks (Asad Citation2001; Esmeir Citation2012; Mahmood Citation2009). As Rao (Citation2020) notes, and as I demonstrate elsewhere (Finden, Forthcoming), it is necessary to pay attention to both colonial continuities and forms of postcolonial agency in the redeployment of colonial security practices today on the level of both the state and the citizen. Indeed, throughout my research, some of my participants re-enforced Egyptian state narratives on security, however, further exploration of this avenue is beyond the scope of this article.

My participants were Egyptian migrants living in the UK. Most were from Cairo, and some had experienced living there.Footnote2 Their backgrounds varied widely: ages ranged from early twenties through to early eighties. They identified as four women and eight men. Seven were Muslim and five were Coptic Christian, although not all ‘practicing’. Their visa statuses in the UK ranged from long term resident to temporary student or worker, to asylum seeker. Several expressed fear about being picked up by the police were they to return to Egypt. The majority were highly educated, some in the UK to pursue Masters or PhD programmes. The majority were able to move internationally because of their relatively privileged class position in Egypt. However, under the current regime of el-Sisi, a number of these mostly political activists would be arrested despite their class location if they returned to Egypt. As I demonstrate, this decolonial method does not solely rely upon identifying ‘authentic’ ‘decolonial’ or ‘Indigenous’ subjects, which could result in essentialist ends, but instead asks about the multiple means by which narratives of colonialism persist and are resisted. It is nonetheless rooted in an understanding that Egyptian citizens have grown up with the stories of British colonialism and Egyptian anticolonial nationalism, and their subjectivities are therefore in part a product of this colonial history.

A key variation in the use of this method was that there was a clear gender difference in terms of how participants engaged with the map. While, broadly speaking, male identifying participants presented alternative stories to the discursive and constitutive violence of the colonial map, for female identifying participants, the violence that the map spoke of appeared to be more pervasive and reminiscent of their experience in Egypt today, which, as I explain below, is suggestive of state-sanctioned crackdowns on feminised and gender non-conforming communities. The representation of violence on the map by female identifying participants illustrates the coloniality of gender. This practice, however, also risks the reification of framing gendered violence as a ‘cultural’ or ‘Arab’ phenomenon. Researchers must be alive to these risks and be aware of the need for intersectional feminist approaches to decolonial methods.

British production of security ‘truths’ in Egypt

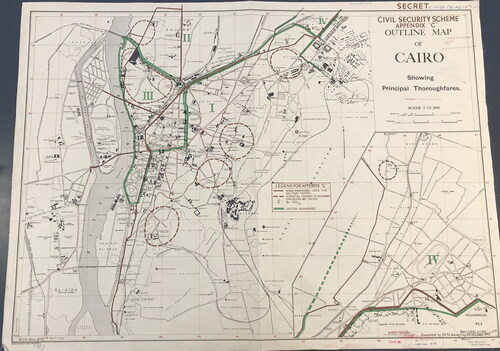

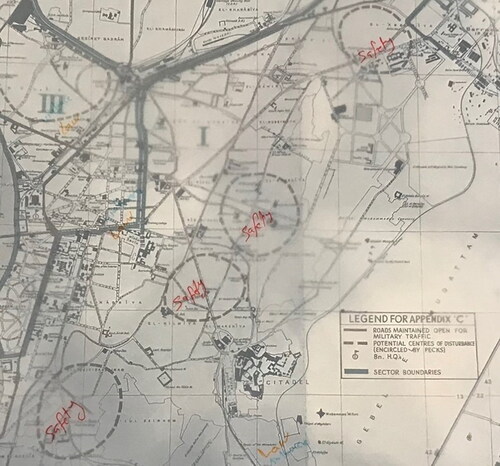

A British military map of Cairo dated 1942 is filed away in the British library. The map comes with little description, but the legend gives away suggestions as to the reason it was drawn. Four items appear in the legend: ‘roads maintained open for military traffic’ are marked with a continuous brown line; ‘potential centres of disturbance’ are circled by a broken brown line; ‘Bn H.Q.s’ or Battalion HQs are marked with a small brown flag; and ‘sector boundaries’ are marked with a thick green line. The map dissects inner city Cairo along straight lines and labels administrative districts in roman numerals .

The presence of the colonial power is represented visibly on the 1942 map especially in its marking of ‘potential centres of disturbance’. When read in the context of the broader colonial archive, the meaning of ‘disturbance’ becomes clearer.

The British occupation of Egypt lasted from 1882 until 1956 when Britain finally removed its last troops. Throughout this time period, the British presented various modes of rule in Egypt, however they could never quite access the country in its entirety. When Britain entered in 1882, there was already a complex set of legal and governmental structures in place that took from Ottoman and Shari’a based codes. What we can see from archival documentation on Egypt is that the early twentieth century signified an existential crisis for the colonial power. This is because the upsurge in anticolonial resistance throughout the British colonies, combined with liberal calls for decolonisation at ‘home’, interrupted the colonial imaginary of an unshakable British Empire. As a result of this ‘geopolitical anxiety’ (Karrar Citation2022), the British administration heightened their surveillance and control of areas and communities construed as ‘threatening’ to the Empire.

By 1942, when this map was drawn, the British protectorate over Egypt had long ended after the nominal independence of 1922. However, this ‘independence’ was negotiated with several reserve clauses which were normalised in the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty. Therefore, Britain continued to occupy Egypt in different modes, past the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and ‘true’ independence, until their final withdrawal in 1956. Forms of monitoring and policing persisted across the different colonial periods and sites, and an understanding of the signifiers of ‘danger’ and ‘threat’ was produced through the constant movement and information sharing of colonial officers and administrators, of soldiers and tourists, of missionaries and of colonial subjects themselves across the ‘patchwork’ of laws and policies that made up a fragmented British Empire (Reynolds Citation2010, 36; Zichi Citation2021, 56).

A list of names drawn up by the Department of Public Security in Egypt in 1922 gives an example of the categories of danger produced by the British power. This document is suggestive of the routinisation of security measures surrounding colonised communities and the production of truths about suspicious and dangerous spaces, as a means to retain control throughout this period of anxiety. The document consists of a twelve-page ‘Provisional Special List’ of Egyptians and foreigners who were to be stopped at ports and borders and to be ‘arrested and disposed of in accordance with instructions given’ (Martial law: powers of the Ministry of the Interior, Citation1922). Next to the name, a section labelled ‘Particulars’ lists an assortment of pieces of information, all varying from person to person. These include: present whereabouts as far as is known, race, family connections, date of deportation, date of birth, criminal interests, affiliation with infamous groups, and a description of the ‘character’ of this person. Next to this list of particulars is listed the file number and ‘instructions’ (i.e., how to deal with this person should they turn up at a port).

Within these pages, we find a broad range of ‘political undesirables’ including the ‘extremist’ and ‘undesirable’ political activists – Bolsheviks, Anarchists, Communists, German sympathisers and Egyptian nationalists – who gather in meeting halls and whisper secrets of plots against the colonial authority; we find the working classes ‘vulnerable’ to influence from middle class activists and who act with a ‘collective’ mentality; we find the immoral and unhygienic communities of sex workers, pimps and criminal ‘gangs’, ‘hashish traders’, ‘arms smugglers’, ‘white slave traders’, who threaten to infect British residents in the big cities of Egypt. Finally, we find the good and moderate Muslims who are friends of the British Empire, and who work with the colonial administration. All such characters are cast out of or drawn into security practices at differing moments. In such a way, identification as a ‘dangerous’ subjects is a slippery process attached to classed, gendered and racialised bodies and communities cast as threatening at different moments (Ahmed Citation2000). This colonial taxonomy of threat works in dispersed, fragmented and compounding ways ‘to discipline dangers and desires that mark the controlled boundary of the human’ (Amar Citation2013, 17) or for Ahmed (Citation2000, 8), to mark the ‘stranger’ ‘as the body out of place’. Communities cast as dangerous are visually transposed and fixed onto the 1942 map in a form that produces a static epistemic truth about poorer areas of the city and the need for intervention, segregation and policing. The practices of segregation and dispossession of poorer areas of the city were carried out by the colonial power in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Egypt, where security policies were produced in moments of power struggle between Britain and Egypt (Brown Citation1990).

For some, the colonial truths produced by the map and the broader archive are suggestive of the British colonial power’s totalising control over and reformation of Egyptian ways of living and being which have transcended the colonial/modern divide, underpinning postcolonial Egypt’s security practices today. Esmeir (Citation2012), Asad (Citation2001) and Mahmood (Citation2009) hold that British colonialism and secularism reformed and replaced local Egyptian governance and law-making by forcing through a new discourse of modern humanity that recast understandings of morality and identity. For Esmeir (Citation2012, 4), the application of colonial law in Egypt was part of a much broader process of ‘humanisation’ that ‘was directed at prescribing new, modern sensibilities toward pain and at delineating the sphere of useful, legal, and acceptable violence’. From this perspective, western secular processes and institutions were instructive in the formation of modern Egyptian identities, which as Takla (Citation2021) shows, have a particular gendered framing.

However, when interrogating archival and cartographical truths we must remain alert to the risks of reifying colonial truth claims and simplifying continuities across timeframes using linear pathways that flatten the messiness of colonial and imperial governance (Stoler, McGranahan, and Perdue Citation2007, 17) and, instead, look to forms of persistence and discontinuity and the re-shaping of imperial truths in new postcolonial forms (Abourahme Citation2018; Rao Citation2020; Stoler Citation2016). The dependence of postcolonial states on colonial structures has shaped the inability of these newly independent governments to manufacture consent and thus a hegemonic rule (Salem Citation2020), underpinning the spatial securitisation of poorer and working-class areas (Abdelrahman Citation2017; Ismail Citation2006) and gendered communities (Amar Citation2013; Takla Citation2021) that both extend colonial logics and refashion them in new postcolonial forms. As I show in the next sections, by carrying out counter-mapping as a research method, we can access both the shifting forms that coloniality inhabits to shape postcolonial security and also the ways in which subjects and communities resist both discursive and constitutive claims to the ‘truth’ by both the colonial power and the postcolonial state.

Counter-mapping ‘threat’ and ‘violence’ in Cairo

A key question I asked my interlocutors was what they thought was meant by the ‘potential centres of disturbance’ marked on the 1942 map. A conversation I had with Amir highlights the rethinking of colonial narratives. Amir is a young Egyptian man who has been involved in activism in Egypt. Many of his friends have been arrested under the current President el-Sisi’s rule and he himself has been targeted by police in Egypt. When Amir looked at the map of 1942 Cairo with me, he understood the ‘areas of potential disturbance’ to be associated with the regulation of poorer Egyptians. He explained that his family had lived for generations in areas like those marked as centres of disturbance on the map. Amir associated the working-class aspect of these areas to mean a sense of community, of neighbourhoods full of ‘families that descend from families’:

These neighbourhoods are basically the old Cairenes. Those are the people that have these houses that are more than 100 years old. Or more. And there are families there known by […]that or this [person] from this family. That’s the son of that and this son of […] and everybody knows each other. And what I mean is that people that lived there have lived there for a long time […] Maybe classes changed, but generally it is a working-class neighbourhood still […] my grandfather is from the same place that I grew up in as well, in that sense. (Amir, pers. comm. December 6, 2019).

While the places under discussion were of various religiosity, there was an understanding that around the places where Mosques were located, there would have been rallies and protests. Demonstrations and labour strikes also took place in these areas. They were understood by the participants as dangerous because of the police presence, rather than because of the communities who lived there. For Youssef, the circled areas varied hugely from one another, and thus, to depict them all as the same ‘centres of disturbance’ did not make sense (Youssef, pers. comm. November 19, 2019). Many re-interpreted the word ‘disturbance’, like Ilyas who told me, ‘this is not disturbance for me, this is like actually … my favourite place in Cairo’ (Ilyas, pers. comm. January 13, 2020). As presented below, Ilyas annotated the map to show that for him, each centre of disturbance represented safety .

For Ismail (Citation2006, xxiii), the practices of everyday life in these ‘informal’ spaces have the potential to become ‘infrastructures of action-foundations upon which resistance in the form of collective action can be built’. It is therefore no surprise that the downtown communities of Cairo have been some key players in anticolonial and anti-governmental revolutionary action. For Amir, such areas had been misinterpreted as violent:

There’s this theory that says that if you go to a neighbourhood and you see the broken windows, it means that this neighbourhood is not safe, as in like people don’t care for the windows of their neighbours or something like that. But I think that this is not right. Because there, in Bab el-Shariya you will see a lot of houses with broken windows and you wouldn’t care because basically if somebody stole something from you, you would know who they are. And no strangers are going to enter the houses. People don’t lock their doors and stuff like that. People are basically living in the streets. So, there is a lot of safety in that sense. (Amir, pers. comm. December 6, 2019).

I would argue that violence is coming from the neglection by the state and somehow how young generations are growing more desperate and with nothing to do. I was the only kid of my age that went to university. So [the area] it’s all about skills and workshops and stuff like that. Somehow, it’s getting hard with gentrification. And all like you know, the rising capitalism and neoliberal policies by the government all of that. And so a lot of people are not earning as much money and there’s a lot of drugs and therefore there’s a lot of violence. But of course, it used to be safer than now, like it’s getting worse. (Amir, pers. comm. December 6, 2019).

While the counter-mapping practices shown above speak to the persistence of spatial forms of coloniality, they primarily imagine the coloniality of power as centralised within the state. Forms of self-regulation, upon which Egyptian security has come to rely, where surveillance and informing is carried out by communities themselves (Abdelrahman Citation2017), is surprisingly absent. Such everyday, citizen-led forms of policing have developed from the encouragement of tensions between competing groups and the ‘creation of enemies’ who pose a threat to public security and are both a particular feature of Egypt’s neoliberal, security-obsessed landscape (Abdelrahman Citation2017; Ismail Citation2006) and a longer legacy of British colonialism (Abozaid Citation2022). For instance, Brown, Dunne, and Hamzawy (Citation2007) explain that internal divisions between leftists and the Muslim Brotherhood have been constructed through the shifting use of emergency law to both quell and placate the groups at different moments.

The use of social planning as a security strategy carries through a form of coloniality as is felt by the marginalisation and erasure of certain ‘informal’ communities in the vying for control over the Egyptian state. The counter-readings of the map therefore transcend the colonial/modern binary, demonstrating that the segregation and securitisation of communities within Egypt is a normalised practice within the collective memory of Egyptians, in new forms. As such, the power struggles layered onto this map can be read as both those between the British colonial power and the Egyptian government, and also between those that vie for power in present-day Egypt. At the same time, the counter-mapping practice is restricted to certain understandings of power. The feminist element of this practice, which gives participants space to sit with and to pay attention to their emotions and memories, added depth and reflection to the interview process. As Mina told me ‘you wouldn’t recognise your connection to places like this unless you’ve been challenged so I think it [the counter mapping process] is interesting… the emotional attachment to places is quite something else’ (Mina, pers. comm. January 17, 2020).

The coloniality of gender and the troubles of representation

While several of my male-identifying participants provided an interrogation of colonial truths and produced alternative, hopeful stories, a number of my female-identifying participants found the process all together more difficult. Salma expressed that the map’s depiction of poorer and working-class areas as ‘dangerous’ was reminiscent of how she feels postcolonial Egypt is being policed and governed today. She told me that the map is:

[…] really disturbing […] what the legend is saying that this is what colonisers deemed to be areas of disturbance and how that kind of echoes with how Egyptians who are like the regime right now […] they still have that same kind of… way of projecting things onto the geography of the city (Salma pers. comm. October 4, 2019).

Salma’s annotation of the map as encompassing layers of violence is more akin to how Leszczynski and Elwood (Citation2015, 15) describe cities as ‘spaces of negotiation’ for women. Similarly, Mariam told me:

When people usually talk about Cairo as a safe city […] I only every really felt safe if I was like if I were at home. Like in my own house and like with the door closed. I think a lot of people don’t understand this because they have not lived anywhere else. But as a woman […] The streets of Cairo […] they’re not something that’s very friendly. Maybe not safe but you know, this sense of being threatened is there all the time. And it’s something that most of us if not all […] it’s been something that our parents and our families have nurtured in us. That you have to be on high alert (Mariam pers. comm. January 11, 2020).

If colonialism is dependent upon the production of gender ‘difference’, then the daily occurrence of gendered violence, particularly targeted at women and queer communities in postcolonial Egypt, can be understood as the neoliberal manifestation of this logic. As Pratt (Citation2020) and Amar (Citation2013) note, a hegemonic form of morality or ‘politics of respectability’ (Pratt Citation2020, 33–58) underscores Egyptian national security and allows for gendered subjects to be cast as a ‘threat’ to Egyptian social mores and norms, and to refuse them access to the political arena. The postcolonial Egyptian state in this sense has refashioned a colonial form of security politics around marginalised subjects through framing Egyptian nationalism ‘in the language of Islamic moralism versus “Westoxified” liberalism or East-versus-West “culture wars”’ (Amar Citation2013, 72). Against a backdrop of post-colonial self-determination which saw the rejection of western ideals and a ‘refashioning of alternative modernities’ (Mourad Citation2014) this framework allows the Egyptian state to deem gendered and queer subjects ‘western imports’, just as it allows the construction of religious nationalist groups as ‘backwards’ and ‘extremist’ at different moments. Gender-based violence can therefore be understood as part of the development of the postcolonial state as a 'securocratic’ regime (Abdelrahman Citation2017) in which the production of security procedures such as surveillance and policing is decentralised and outsourced to ‘everyday’ citizens. In such a way, Mariam and Salma’s mapping experiences speak to a different form of power and violence than that explored with most of my male-identifying participants: they point to the more insidious, everyday and community-based forms of (self)policing and informing.

Salma’s map is reminiscent of community projects such as the Cairo-based online mapping initiative, HarassMapFootnote3, which was developed for women to map incidences of sexual harassment in Egypt. This online platform provides a space for women to present their own realities of gendered and sexual violence in Cairo, and is testimony to the fact that, while certain downtown areas of Cairo that can be reframed as ‘safe’, pockets of resistance and ‘full of life’ by some, they cannot necessarily be thought in the same way for feminised and gender non-conforming communities, as indeed these are the spaces in which daily violence is reproduced as a part of the security state. However, while a gender lens is essential to understanding how daily life is shaped by gendered and sexualised violence, Grove (2015, 347) has argued that this particular practice of counter-mapping or ‘crowd-mapping’ has appealed to ‘culturalist explanations of sexual violence in the Arab world’, and, by being framed in a ‘liberal rule of law frame’, has bolstered the racialised imagery of particular communities of men as prone to violence, justifying legal and police action against them.

What this suggests is that a decolonial counter-mapping project must be aware that representation ultimately risks re-fixing imperial constructions of ‘threatening’ spaces and communities and can help bolster neoliberal plans for their securitisation and destruction. In all cases, these experiences point to the necessity for intersectional feminist and decolonial research that is respectful, reflective and that seeks contextualised interpretations of truths.

Conclusion

As I have outlined in this article, drawing on the existing literature as well as my own research practice, counter-mapping provides an example of a decolonial feminist method. This method can be used to transform the research space into one of active listening and dialogue, one whereby the researcher and participants can co-investigate colonial truths and re-map alternative forms of knowledge. This is vitally important, providing a means by which to speak back to coloniality and its erasures of and control over knowledge production and imagination. Furthermore, a feminist approach which pays attention to affective processes within counter-mapping offers the possibility of engaging with decolonial praxis through allowing participants space to reimagine the colonial archive, as demonstrated by my interlocutors who re-mapped Cairo. This process can also help to expose, not only continuities but also ruptures, where stories of the present must be interpreted within their socio-political context.

In the context of research investigating coloniality of counter terrorism in Britain and Egypt, I demonstrated that some forms of the colonial truth-making regarding the designation of certain areas as ‘threatening’ persist in postcolonial Egypt, which speaks to the normalisation of ‘classes’ of danger within Egyptian society. Using counter-mapping, my participants reimagined historical uses of security narratives through their own lived experience. Spaces labelled as potentially dangerous were described as full of life, safety and joy. Homogenous claims to ‘danger’ were interrogated through a diversity of the different characters of who might have lived in such areas.

The counter-mapping process also spoke to forms of coloniality in different guises, allowing for a reflection on how the past and the present interact with one another. This was seen when the map was framed as holding the many layers of security practices, both those carried out by the British colonial power and those of the postcolonial Egyptian state. The securitisation and segregation of working class and gendered communities was experienced by Salma in particular, who felt that similar techniques of segregation still applied today, suggesting the persistence and appropriation of colonial security in postcolonial Egypt. These readings transcend the separation of a colonial ‘past’ and a modern ‘present’ and illustrate how the colonial/modern continuum is felt by marginalised communities in Egypt.

In addition, I uncovered an important gender difference in the praxis of counter-mapping. My male-identifying participants generally re-interpreted the map with alternative truths. However, they did not speak to the more everyday forms of violence present in Egypt. The female-identifying participants were generally unable to reimagine the city as a safe or joyful place. I argued that this difference denotes the pervasive nature of the coloniality of gender that has become a major form of everyday control in present-day Egypt, developing alongside other forms of self-policing. At the same time, the practice of counter-mapping itself can risk being reappropriated into imperial paradigms that reify constructions of poorer communities as dangerous or ‘informal’ (Ismail Citation2006) areas that require intervention. A decolonial feminist counter-mapping project must therefore be aware of the risks of (re)representation and carry out an intersectional praxis that is respectful, reflective and one that seeks contextualised interpretations of truths.

Counter-mapping is therefore a transformative tool for researchers when critically approaching the archive and is an approach that could be used when speaking to members of other formerly colonised communities. Researching alongside participants within the archival research space transforms not only our conceptualisations of political history but also the research environment itself. When we hold a shared intellectual space with participants, we are transformed into more reflexive researchers, and the colonial order of researcher/researched is perhaps not upended but is certainly unsettled.

Data Access Statement

Our supporting research dataset will not be published because it contains personal and / or sensitive data.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the anonymous peer reviewers for their invaluable comments on this article as well as the editorial team at Cambridge Review of International Affairs. Thank you to Ruth Kelly, Raquel da Silva and Emily Jones for providing me with generous feedback on this article. Thank you to my participants for being part of my research. Thank you to Anne Alexander for pointing me towards the map. Thank you also to Gina Heathcote and Mayur Suresh for all your support. The author acknowledges and thanks the British Library for providing permission to reproduce their images in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alice E. Finden

Dr Alice E. Finden is an Assistant Professor of International Politics at Durham University. Her research explores the coloniality of counter terrorism and the normalisation of everyday violence through logics of race, gender, class, and sexuality. Her work has been supported by the ESRC. She has peer reviewed publications with Feminist Review journal and the Australian Feminist Law Journal and is the co-editor of a special journal issue entitled ‘Hygiene, Coloniality, Law’ also with the Australian Feminist Law Journal. She is a co-convenor for the British International Studies Association Critical Studies on Terrorism Working Group. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 I understand gender to be part of a constructed system of coloniality that orders and divides on a binary of male/female (Lugones Citation2007) and erases pre-colonial and non-colonial systems of gender and sexuality. As a result of this gender order, violence is aimed at groups who are gendered in certain fashions, often those who are feminised or are seen to stray outside of acceptable gender expressions. My participants did not expressly identify as anything other than male or female, and therefore I utilise these terms to both acknowledge this and to acknowledge the level of violence against women in Egypt.

2 NB. All participants quoted in this article are anonymised.

References

- Abdelrahman, Maha. 2017. “Policing Neoliberalism in Egypt: The Continuing Rise of the ‘Securocratic’ State.” Third World Quarterly 38 (1): 185–202.

- Abourahme, Nasser. 2018. “Of Monsters and Boomerangs: Colonial Returns in the Late Liberal City.” City 22 (1): 106–115.

- Abozaid, Ahmed M. 2022. Counterterrorism Strategies in Egypt: Permanent Exceptions in the War on Terror. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Akked, Dania. 2012. “Gezirit Al-Waraq: Cairo’s Forgotten Island.” LSE Blog (Blog), October 4. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2012/10/04/geziri-al-waraq-cairos-forgotten-island/

- Amar, Paul. 2013. The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexuality Politics, and the End of Neoliberalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Arondekar, Anjali. 2005. “Without a Trace: Sexuality and the Colonial Archive.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 14 (1): 10–27.

- Asad, Talal. 2001. Thinking about Secularism and Law in Egypt. Leiden: ISIM. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/10066/paper_asad.pdf?sequence=1.

- Biancani, Francesca. 2013. Sex Work in Colonial Egypt: Women, Modernity and the Global Economy. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Boatcă, Manuela. 2021. “Counter-Mapping as Method: Locating and Relating the (Semi-) Perepheral Self.” Historical Social Research 46 (2): 244–263.

- Brown, Nathan J. 1990. “Brigands and State Building: The Invention of Banditry in Modern Egypt.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 32 (2): 258–281.

- Brown, Nathan. J. 1995. “Retrospective: Law and Imperialism: Egypt in Comparative Perspective.” Law & Society Review 29 (1): 103–126.

- Brown, Nathan J., Michele Dunne, and Amr Hamzawy. 2007. Egypt’s Controversial Constitutional Amendments. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/egypt_constitution_webcommentary01.pdf.

- Chukwuma, Kodili Henry. 2022. “Archiving as Embodied Research and Security Practice.” Security Dialogue 53 (5): 438–455.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299.

- Disembodied Territories 2023. “About.” https://disembodiedterritories.com/About.

- Doty, Roxanne L. 1996. Imperial Encounters: The Politics of Representation in North-South Relations. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Egyptian Independent. 2020. “Cairo court imprisons 35 people over Warraq Island clashes.” Egyptian Independent, December 27. https://egyptindependent.com/cairo-court-imprisons-35-people-over-warraq-island-clashes/

- Esmeir, Samera. 2012. Juridical Humanity: A Colonial History. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Ezzat, Ahmed. 2020. “Law and Moral Regulation in Modern Egypt: Ḥisba from Tradition to Modernity.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 52 (4): 665–684.

- Fahmy, Khaled. 2012. “The Birth of the ‘Secular’ Individual: Medical and Legal Methods of Identification in Nineteenth-Century Egypt.” In Registration and Recognition: Documenting the Person in World History, edited by Keith Breckenridge and Simon Szeter, 335–356. Oxford: Oxford University Press/The British Academy.

- Finden, Alice Ella. 2021. “Hygiene, Morality and the Pre-Criminal: Genealogies of Suspicion from Twentieth Century British-Occupied Egypt.” Australian Feminist Law Journal 47 (1): 27–45.

- Finden, Alice Ella. Forthcoming. “Colonial Law and Normal Violence: The Racialised, Gendered and Classed Development of Counter Terrorism.” In Global Counterterrorism: A Decolonial Approach edited by Tahir Abbas, Sylvia Bergh and Sagnik Dutta. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Fanon, Franz. 1963. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

- Garland, David. 2014. “What is a ‘History of the Present’? On Foucault’s Genealogies and Their Critical Preconditions.” Punishment & Society 16 (4): 365–384.

- Georgis, Dina. 2013. The Better Story: Queer Affects from the Middle East. Albany: Suny Press.

- Ghaddar, J. J., and Michelle Caswell. 2019. “To Go Beyond’: Towards a Decolonial Archival Praxis.” Archival Science 19 (2): 71–85.

- Grove, and Nicole, Sunday. 2015. “The Cartographic Ambiguities of HarassMap: Crowdmapping Security and Sexual Violence in Egypt.” Security Dialogue 46 (4): 345–364.

- Gunaratnam, Yasmin, and Carrie Hamilton. 2017. “The Wherewithal of Feminist Methods.” Feminist Review 115 (1): 1–12.

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12 (2): 1–14.

- Hemmings, Clare. 2005. “Invoking Affect: Cultural Theory and the Ontological Turn.” Cultural Studies 19 (5): 548–567.

- Hill Collins, Patricia. 2002. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ismail, Salwa. 2006. Political Life in Cairo’s New Quarters: Encountering the Everyday State. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Karrar, Hasan H. 2022. “The Geopolitics of Infrastructure and Securitisation in a Postcolony Frontier Space.” Antipode 54 (5): 1386–1406.

- Khalili, Laleh. 2013. Time in the Shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgencies. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Khan, Rabea M. 2021. “Race, Coloniality and the Post 9/11 Counter-Discourse: Critical Terrorism Studies and the Reproduction of the Islam-Terrorism Discourse.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 14 (4): 498–501.

- Kholoussy, Hanan. 2010. “Monitoring and Medicalising Male Sexuality in Semi-Colonial Egypt.” Gender & History 22 (3): 677–691.

- Leszczynski, Agnieszka, and Sarah Elwood. 2015. “Feminist Geographies of New Spatial Media.” Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes 59 (1): 12–28.

- Lobo-Guerrero, Luis, Laura, Lo Presti and Filipe, dos Reis, eds. 2021. Mapping, Connectivity, and the Making of European Empires. Maryland: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

- Lorde, Audre. (1984) 2007. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press Berkeley.

- Lugones, María. 2007. “Heterosexualism and the Colonial/Modern Gender System.” Hypatia 22 (1): 186–219.

- Lugones, María. 2010. “Towards a Decolonial Feminism.” Hypatia 25 (4): 742–759.

- Mahmood, Saba. 2009. “Feminism, Democracy, and Empire: Islam and the War on Terror.” In Gendering Religion and Politics: Untangling Modernities edited by Hanna Herzog and Ann Braude. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2000. “The Many Faces of Cosmo-Polis: Border Thinking and Critical Cosmopolitanism.” Public Culture 12 (3): 721–748.

- Mignolo, Walter. 2009. “Cosmopolitanism and the De-Colonial Option.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 29 (2): 111–127.

- Mourad, Sara. 2014. “The Naked Body. of Alia: Gender, Citizenship, and the Egyptian Body Politic.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 38 (1): 62–78.

- Moraga, Cherríe and Gloria Anzaldúa. eds. 1983. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.

- Nijjar, Jasbinder S. 2018. “Echoes of Empire: Excavating the Colonial Roots of Britain’s ‘War on Gangs.” Social Justice 45 (2/3): 147–162. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26677660.

- Pratt, Nicola. 2020. Embodying Geopolitics: Generations of Women’s Activism in Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon California: University of California Press.

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2007. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 168–178.

- Rao, Rahul. 2020. Out of Time: The Queer Politics of Postcoloniality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reynolds, John. 2010. “The Long Shadow of Colonialism: The Origins of the Doctrine of Emergency in International Human Rights Law.” Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy 6 (5): Research paper no. 19/2010. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/clpe/86

- Said, Edward. (1978) 2003. Orientalism. London: Penguin Books.

- Salem, Sara. 2020. Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt: The Politics of Hegemony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sen, Somdeep. 2022. “The Colonial Roots of Counter-Insurgencies in International Politics.” International Affairs 98 (1): 209–223.

- Singh, Avinash. 2012. “State and Criminality: The Colonial Campaign against Thuggee and the Suppression of Sikh Militancy in Postcolonial India.” Sikh Formations 8 (1): 37–58.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London and New York: Zed Books Ltd.

- Stoler, Ann Laura, Carole McGranahan, and Peter Perdue. eds. 2007. Imperial Formations. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2010. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2016. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Takla, Nefertiti. 2021. “Barbaric Women: Race and the Colonization of Gender in Interwar Egypt.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53 (3): 387–405.

- Tazzioli, Martina, and Glenda Garelli. 2019. “Counter-Mapping Refugees and Asylum Borders.” In Handbook of Critical Geographies of Migration, edited by Katharyne Mitchell; Reece Jones and Jennifer L. Fluri, 397–409. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Thambinathan, Vivetha, and Elizabeth Anne Kinsella. 2021. “Decolonizing Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Creating Space for Transformative Praxis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 160940692110147.

- Yao, Joanne. 2022. “The Power of Geographical Imaginaries in the European International Order: Colonialism, the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, and Model International Organizations.” International Organization 76 (4): 901–928.

- Yegenoglu, Meyda. 1998. Colonial Fantasies: Towards a Feminist Reading of Orientalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2012. “Anthropology in and of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (1): 461–480.

- Zichi, Paola. 2021. “Prostitution and Moral and Sexual Hygiene in Mandatory Palestine: The Criminal Code for Palestine (1921–1936).” Australian Feminist Law Journal 47 (1): 47–65.

Archival Documents

- Maps 1942. “Cairo [Civil Security Scheme].” In MDR Misc, 875. London: The British Library. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/maps/africa/5000632.html

- Martial law: powers of the Ministry of the Interior. 1922. Provisional Special List. FO 141/430/4/5512/12. The National Archives, Kew Gardens, London, UK.