Abstract

This work concerns the role of winemakers as independent consultants of wineries with respect to recent changes in the Italian wine industry. Internationalisation and new consumption styles have turned the wine market into a mass market. Furthermore, new actors have emerged that mediate the convergence of supply and demand, and foster the adoption of new winemaking practices. Innovations in winemaking have had to overcome the resistance of the advocates of the traditional conception of quality, institutionalised by the denomination of origin regulations. Independent winemaking consultants and industry media, mainly wine guides, were key actors behind the innovations that fit the new context. We document the growing importance of winemaking consultants, and how they have been complemented by wine guides. We analyse the networks of wineries induced by the multiple affiliations of winemakers, as reported by the oldest Italian guide, I Vini di Veronelli, in the period 1997–2006. In these networks two wineries are tied if a winemaker has an affiliation with both of them. We analyse the evolution of these networks, and assess whether the structural position of a winery is associated with the ratings of its wines.

Introduction

The wine industry has recently undergone important changes in both demand and supply. The demand for wine is increasingly international, since wine consumption is growing in countries that were not traditional consumers. Countries that were traditional producers and consumers, like Italy, faced a shift of consumption habits toward lower volumes per capita but higher average quality, and an increased weight of mass distribution in retail sales. Production internationalised, too, since wines from newcomer countries pose credible commercial challenges to older prestigious producers. Communication of the quality of products, through recognisable brands and wine guides, has become very important for producers because the geographical distances between production and consumption tend to enlarge. With some oversimplification, we might describe these changes as a turn from a niche market to a mass market.

This evolution is fostering changes in winemaking practices as well as in the conception of wine quality, which imply a departure from the traditions of the industry. Traditional winemaking practices and conceptions of ‘good wine’ were institutionalised in the denomination of origin regulations. These regulations embed each wine within a geographical locus of production, implying a dependence of production on natural contingencies. On the contrary, the exploitation of emergent market opportunities requires a finer control of production. This caused the diffusion of methods of winemaking that allow stabilisation of the quality of wines across time (vintages) and space, loosening the tie between grape and geographical area. Much of this change in production practices has been implemented by a relatively new category of professionals, namely independent winemakers who sell their consulting services to wine producers. The conflict between traditional and ‘modern’ conceptions sparked debates among industry practitioners and was reflected in the evaluation criteria adopted by wine guides. The guides perform a key role of interface between wine producers and consumers, and rewarded the market orientation of the wineries through their policies of selection and evaluation of wines.

The aim of this paper is to document the role of independent winemakers and wine guides in these recent trends of the Italian wine industry. We analyse data coded from the issues 1997–2006 of the Italian wine guide I Vini di Veronelli. By means of these data, we i) describe the network induced among wineries by shared winemakers, and ii) assess the association between wineries' position in the network and the guide evaluations of wines. This introduction is followed by a description of the traditional features of the wine industry and the changes that it has recently undergone. Subsequently, we discuss the role of winemakers and wine guides throughout these changes. Sections follow where we present the data and methods of our analysis, and the ensuing results. Finally, we discuss our findings and conclude.

Recent Trends in the Wine Industry

Important transformations have characterised the Italian wine market in recent decades. In the first place, the patterns of wine consumption and production changed dramatically, with a sharp rise in wines with a recognisable brand at the expense of bulk wines. The volume of wines endowed with a controlled denomination rose from 10.7% in 1980 to 25.3% of total production in 2005, whereas total production decreased from 83,950 to 53,275 thousands of hectolitres in the same period (Enotria, Citation2000–2007). On the consumption side, the volume of wines with a controlled denomination rose from 10.9% in 1980 to 21.7% of total consumption in 2005. In the same period, wine consumption decreased from 48,723 thousands of hectolitres to 28,207.

A second important change is the growing internationalisation of the wine market. New countries emerged worldwide, both as producers and consumers of wine, posing a competitive challenge to older producers such as Italy and France (Anderson et al., Citation2003; Anderson, Citation2004; Bernetti et al., Citation2006; Campbell and Guibert, Citation2006). This increased competition has come along with a growing concentration at a number of levels of the global value chain (Coelho and Rastoin, Citation2006a, Citation2006b; Goodhue et al., Citation2008; Taplin, Citation2006). Indeed, all over the world both wineries and distributors have consolidated through mergers and acquisitions, seeking scale and scope economies and vertical integration (Cholette et al., Citation2005; Guibert, Citation2006).

These changes in the global wine market context imply pressures that challenged the established arrangements and traditions of the Italian wine industry. The Italian wine industry is fragmented into many small producers, whose production tends to be highly heterogeneous across time (vintages) and space (regions, and specific geographical areas within them). Indeed, the traditional conception of a good wine regards heterogeneity and variability as intrinsic to it. According to this perspective, the quality of a wine is enhanced by the fact of being idiosyncratic to its terroir. This French word subsumes the referral to the geographical locus of production, to the contextual preconditions that a given location expresses for the growing of grapes and the making of wines (natural factors, like weather and soil, as well as historical and cultural ones). Traditional winemaking practices leave a great weight to natural factors by setting relatively narrow limits for human intervention in the processes of wine fermentation and aging.

In Italy, tradition was institutionalised by the denomination of origin law in 1963. This law introduced an official recognition of wine quality, by requiring the satisfaction of very detailed requirements before a wine can be marketed under a specific denomination of origin. These requirements are specific to each denomination, they are stated in the disciplinare di produzione and include the geographical area of production, the grape varieties to be used and their blend, the grape/vineyard and wine/grape yields, the alcoholic content, several production and aging methods, and regulate also the information be printed on the bottle's label. Denominations were initially grouped in two classes, DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) and DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita). The second group collects denominations of higher quality wines.

This classification was conceived as a vertical classification system (Zhao, Citation2005), that expressed a presumption of the value of wine related to the category it belonged to (Delmastro, Citation2005). However, besides being an official recognition of wine quality, this institutional classification was also intended as a minute inventory of wine varieties. Furthermore, as shown in , the number of denomination categories increased over time (Mondo Agricolo, Citation1996; Terra e vita, Citation2001).

Table 1. Number of DOC and DOCG wines in the Italian denominations' system (1967–2007)

The Italian denomination system was both induced by and tended to reproduce the fragmentation of the wine industry. Furthermore, it formalised the traditional conception of quality based on the bond wine-terroir. Such a framework of categories was supposed to be helpful for the development of the market by narrowing the gap between high quality products and the general public. In fact, wine quality can only be appreciated with consumption, and non-expert consumers typically lack the ability to choose among products at a medium-high quality level. Product categories were supposed to bring order into the heterogeneity of wine types and qualities, by performing the role of a cognitive framework that would help consumers and producers to formulate their own judgements and choices, and foster their convergence in market exchanges (Odorici and Corrado, Citation2004).

The denomination of origin system failed to perform this role. “The heaviest fault of the whole denomination system of DOC and DOCG is to be a system of wine quality guarantee. In reality, quality corresponds to territorial origin as much as the birthplace of a person is related to his or her merits and defects” (from Blog Archive of Vino al Vino, 18 January 2007). The exaggerated articulation of categories tends to confuse consumers. On the production side, even though in 1992 a new category of denominations (the IGT, Indicazione Geografica Tipica) was introduced in order to accommodate high quality productions that could not meet the DOC/DOCG requirements, the rigidity of the disciplinare di produzione hampered the innovative efforts of producers. Innovations required by the exploitation of emergent market opportunities were difficult within the rigidity of the DOC/DOCG framework.

The Role of Independent Winemaker Consultants and Wine Guides

In brief, the system of denominations suffered from two related problems: i) it failed to provide effective guidance to production and consumption choices, and ii) institutionalised a logic of wine production and quality that at least in part was at odds with emergent market pressures. Since the 1980s other actors gained a prominent position in the Italian wine industry by filling these gaps, at times complementing and at times challenging the official denomination system (Odorici and Corrado, Citation2004; Zhao, Citation2005). A key role in this respect was jointly performed by wine guides and independent winemakers.

Wine guides appeared in the early 1980s in order to meet the consumers need for guidance about products' quality, left unattended by the DOC/DOCG regulations. There are currently five main wine guides in Italy. The oldest ones are the Vini d'Italia guide, published jointly by Gambero Rosso Editore and Slow Food Arcigola Editore, and I Vini di Veronelli, founded by the famous wine expert Luigi Veronelli, very active in the industry since the 1950s. The great success of these two guides in the 1980s and 1990s fostered the appearance of new ones. In 1996 the Guida dei Vini Italiani was first published by Luca Maroni. In 2000 the Italian Association of Sommeliers (AIS) started its own guide, Duemila Vini. In 2001 the editorial group L'Espresso added a wine guide, I Vini d'Italia de L'Espresso to its famous guides of hotels and restaurants. Unlike the situation in France, the influence of foreign guides like Wine Spectator is still weak in Italy.

The need for actors that mediate the matching of supply and demand in the “large number wine market setting” (Roberts and Reagans, Citation2005, Citation2007; Hsu et al., Citation2008) explains the immediate success of the wine guides. They select and review thousands of wines, performing an intermediary role between the supply and demand sides of the market. Wine guides are not directly engaged in production or consumption choices, but contribute to their structural context by providing the informative infrastructure that underpins market decisions; they foster market functioning by providing at the same time guidance for consumers and an important reference for producers. Given the ambiguities that are intrinsic to the definition of a ‘good’ wine, the process of product selection and review undertaken by the guides is not just a neutral and objective assessment of how far products correspond to an absolute standard of quality. Selection and review instead reflect criteria that implicitly embody specific conceptions of quality, which may differ across the guides (Odorici and Corrado, Citation2004) but always complement the rigid codification scheme of the denomination system, and often depart from it.

While the requirements for admission of a wine in a denomination category are explicit, the mechanisms through which it gets reviewed in the guides are ambiguous, as are the actions a producer should take in order to get positive evaluations. The role of independent winemakers, professionals of winemaking that provide independent consultancy to wineries, is important in this respect. The importance of these actors has grown only recently, in parallel with that of the wine guides. Some of these independent winemakers are now well known celebrities in the industry, and many of them provide consultancy services to a great number of wineries, sometimes more than ten at once. They act as a meeting point between the guides and the many small wineries into which the industry is fragmented. Their contribution to wineries includes both technical and market advice, as well as reputation benefits. First, the advice of independent winemakers is valuable to wineries in that it includes an evaluation of which kind of wine may attract interest and good reviews from the industry media. In this respect, winemakers act as interpreters of the conceptions of quality embodied in the selection and evaluation practices of the guides. They bring to the producer both a knowledge of which features will enhance a wine's chances of success, and a knowledge of which production practices are conducive to that kind of wine. Second, winemakers are often considered as sort of public relations experts (Arrigoni, Citation2000; Roberts and Reagans, Citation2005) and endow wineries with their own reputation (Delmastro, Citation2005; Castriota and Delmastro, Citation2008). Wine is an experience good and the wine industry is what Karpik (Citation1989, Citation2000) would call an “economy of quality”. The evaluation of a wine cannot be made in advance of its consumption, and it involves a complex judgment that cannot be entirely based on objective and intrinsic characteristics. Extrinsic factors matter as well, and the affiliation of a winemaker is more easily observed than a difference in quality (Benjamin and Podolny, Citation1999). Prominent winemakers serve “as indicators of the unobserved quality of the producers that employ them” (Roberts and Khaire, Citation2008; Callon et al., Citation2002).

Both independent winemakers and wine guides were crucial in the diffusion of modern practices among many small wineries. “Modern winemaking constitutes a set of practices that is looser to define (and observe) than traditional [winemaking]” (Negro et al., 2007), but can be distinguished from tradition in that it fosters the departure from established practices “in the interest of gaining good outcomes in the market” (Negro et al., 2007). In their turn, wine guides were the window of modernists on the market. They provide orientation to consumers, and at the same time reflect a logic of quality that is closer to the taste of the general public than to the traditionalists' logic. They are decisive in building the reputation of winemakers, and their selection and review policies reward the wines that better fit the taste of the general public.

Terroir-driven wines are often associated with wines of a ‘natural’ style. By ‘natural’, proponents mean wines with limited human intervention. That is, no additions of acid, tannin, concentrate, etc. Thus, the terroir (as it relates to the effects of climate anyway) remains unmasked. Style-driven wines are wines where a winemaker strives to create wine of a certain style—typically a ‘New World’ or riper style. Wines of this type are more likely to have less variation between vintages, utilise technology and post-harvest additions like those described above. These wines are also thought by critics to reveal less of their terroir as those subtleties are masked by the intervention.

If we were to count this as an election and votes equalled purchases, the Style-driven wines would win hands down. I mean would you want to buy apple pies from the lady at the farmer's market if you didn't know for certain if this week's batch would be as good as last week's? On the other hand, are terroir fans enjoying something that the rest of the masses are missing out on? (The Zinquisition, 20 December 2005)

Main Directions of the Study

We analyse the affiliations of winemakers with wineries and the ratings of wines reported by the wine guide I Vini di Veronelli, for the decade 1997–2006. We analyse the evolution of networks where nodes are wineries and a tie exists among two of them if they share the winemaker. We also analyse the association between the network position of a winery and the ratings given by the Veronelli guide to its wines. Our general expectation is that the network induced between the wineries by the multiple affiliations of independent winemakers gets more connected across the period of observation, and that the involvement of a winery in the network is positively associated with the evaluation of its wines.

Data and Method

The empirical context of our study are Italian high quality wines in the decade 1997–2006. The source of our data is the most prominent Italian wine guide, I Vini di Veronelli, named after its founder Luigi Veronelli, who was very active and influential in the wine industry from the 1950s to his death in 2004. This guide targets both expert and non-expert consumers and offers a comprehensive view of Italy's best wines by listing hundreds of wineries and reviewing a selection of wines for each of them. With respect to other guides, the information reported in I Vini di Veronelli is the most detailed. For each winery it reports address, owner, winemaker's and agronomist's identity and total size of the vineyards. For each wine it reports vintage, size of the vineyard, production in bottles, the type of aging (in steel tanks, wood tanks, barriques or combinations of these), grape(s) used, category of price, class of denomination of origin (DOCG, DOC, IGT, Table wine), and ratings based on wine's tasting.

There are two such ratings. The first rating is expressed in hundredths and refers to the tasting of a sample of wine; it is reported with an indication of the vintage the sample comes from and of the identity of the taster. The second rating is expressed on a one to three scale (symbolised by stars) and expresses a general evaluation of the wine's features across recent years. While the rating in hundredths is reported only for a subset of the wines, the second type of rating is reported for almost all the wines cited in the guide. Only wines that were not reviewed in past issues are excluded. Our database codes all the information available in the source.

Our sample consists of all the wineries cited by the guide during the period 1997–2006. reports the number of wineries year by year; the totals are 16,468 wines and 3157 wineries. All those wineries are included for which the guide selected and reviewed at least one wine (a few wineries cited in the guide were excluded because none of their wines was reviewed). The total number of wine reviews during the ten-year observation period is 74,274.

Table 2. Number of wineries and wines in I Vini di Veronelli guide: 1997–2006

We coded the affiliations of winemakers with wineries for each of the 1997–2006 issues of the guide. This resulted in ten networks (named 1997, 1998, etc. in the tables), where wineries are nodes and ties represent the sharing of a winemaker between pairs of wineries. We also analyse the network of wineries obtained by conflating the time dimension of the data. This network (called All in the tables) includes all wineries observed across the period. In this case, ties connect wineries that employed the same winemaker even at different times within the observed period. For instance, in the All network two wineries are tied if one of them employed a winemaker in 1997 and the other one employed the same winemaker throughout the period 2001–2006.

Our network analysis proceeds in two steps. We first report basic statistics that describe the amount of connectivity in the network:

| i. | The number of ties is the number of pairs of wineries that share the same winemaker. | ||||

| ii. | The density of the network is the number of ties as a percentage of all possible pairs of wineries, that is n(n − 1) / 2 where n is the number of wineries. Density is a measure of the amount of connectivity in the network that can be compared across networks with different size. This allows a meaningful comparison across the observed years. | ||||

| iii. | The average degree of the wineries is closely related and sometimes preferred to the density. The degree of a node is the number of other nodes it is directly tied to; in the present case it is the number of wineries with which a given winery shares a winemaker. The average degree of wineries is, like density, a measure of the extent to which the nodes are tied to one another. | ||||

| iv. | Indirect connections: Even if no direct tie exists between two nodes, they can be indirectly connected by an alternate sequence of intermediate lines and nodes (path). The length of a path is the number of lines it contains, and the (geodesic) distance among two nodes is the length of the shortest path: 1 if two nodes are directly tied, 2 if they are directly tied to the same third node (if no direct tie exist among them), and so on. The % of connected pairs is the number of wineries connected by a path over the number of all possible pairs. It is akin to density, but counts both indirect paths as well as direct connections (paths of length 1). | ||||

The last step of the analysis is focused on the association between the ratings given by the guide and the position of the winery in the network induced by winemakers' affiliations. For each winery we computed the mean of the evaluations that the guide gave to its wines in each year. We tested whether the mean evaluations obtained by wineries are associated with their inclusion in the web of ties induced by winemakers affiliations, with the expectation that membership of wineries in large connected components is associated to higher ratings of their wines.

Results

Across the ten years 1997–2006 the guide cited 2123 different winemakers, among which 286 were cited only once and 235 were cited in all ten years. In 2006, 27 winemakers held an affiliation with ten or more wineries, and the maximum number of affiliations of a winemaker was 61 wineries, observed in 2006. shows that the number of winemakers cited in the source rises from 714 in 1997 to 1124 in 2006, and the average of their affiliations rises from 1.49 in 1997 to 2.16 in 2006. If we look at the ratings of the wines related to a winemaker, that is the wines produced by wineries with which a winemaker held an affiliation, we see that in 2006 more than 40% of the winemakers obtained at least a three star evaluation, whereas in 1997 this percentage was lower than 19%.

Table 3. Winemakers in I Vini di Veronelli guide: 1997–2006

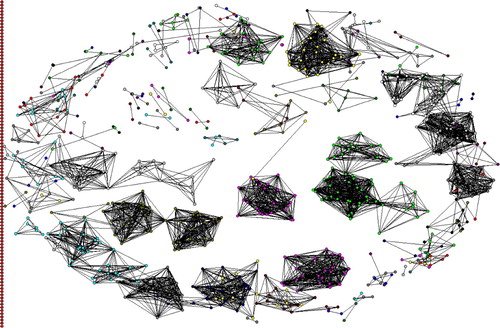

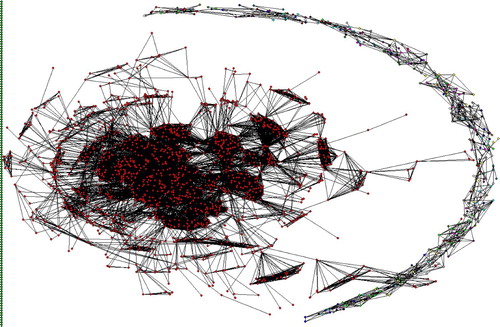

shows a description of the networks of wineries induced by the multiple affiliations of winemakers in each of the observed years (1997, 1998, etc.), and in the case of the All network also by the movement of winemakers across wineries. From 1997 to 2006 we observed a remarkable increase in the average degree of the wineries, that is the number of other wineries with which they share a winemaker. In fact, this statistic rose from four in 1997 to almost 12 in 2006. Network density increased, too, though not as much as the average degree: 0.43% in 1997 versus 0.58% in 2006. This is an artefact of the increased size of the network, due to the increasing number of wineries cited by the Veronelli guide in the observed period. In fact, the number of possible ties increases more than linearly with the size the network, whereas the number of ties that each winery holds is constrained by the affiliations a winemaker may hold at once. The All network in the last row of includes 2869 wineries, all those that were included in at least one of the 1997 –2006 networks. This number does not include the wineries for which the winemaker was not reported by the source. These wineries were not included in the networks, hence the difference in the total number of wineries observed in the decade (3157 as reported above). It is remarkable that in the All network, which allows a tie to be created not only by the simultaneous affiliations of winemakers but also by their transfer among wineries, the percentage of connected pairs jumps to almost 30%, whereas it is never higher than 1.21 (in 2004) in the single-year networks.

Table 4. Network descriptives

describes the structural form of the networks by reporting the size distribution of their connected components. In each of the observed years the networks are quite fragmented, since the largest component never includes more than 9% of the wineries. However, in 2003 a sudden increase occurred in the size of the largest component (both absolute and relative), while the number of isolated wineries (those that do not share the winemaker with any other) is more or less stable. Consistently with the high percentage of connected pairs in the All network shown in , shows that in this case the largest connected component includes 1553 wineries, more than a half of the wineries included in the All network.

Table 5. Network components

A graphical description of the structure of the networks is given by and . The figures help give an appreciation of the differences between the single-year networks, exemplified by the 2001 network in , and the All network of , which is dominated by a very large connected component.

Next we examined the association between the structural position of wineries in the networks and the evaluation of their wines by the Veronelli guide. We averaged the evaluations of the wines of each winery in each year, and compared year by year these averages across two groups of wineries: those that belonged to a network component larger than two, and those that did not. These comparisons are shown in .

Table 6. Wineries membership in network connected components and wines evaluations

The fifth column of the table shows that wineries that were members of meaningful connected components obtained higher evaluations, and this difference increased across the observation period. All these differences are statistically highly significant (at a 0.01 level). It is also remarkable that in 2006 38.2% of the wineries that were members of network components with size greater than two received at least one three star evaluation, against the 26.4% of other wineries. In 1997 these percentages were 18.9% and 12.9%, respectively.

compares the members of the largest connected component in the All network to the non-members. Once again, evaluations are higher for the wineries included in the largest connected component of the All network, and the differences increase during the observation period. Values are statistically highly significant (at a 0.01 level). The table shows also that in 2006 40.8% of the members of the largest component received at least one three star evaluation, as compared with 26% of the others. In 1997 these percentages were 17.4% and 12.8%, respectively.

Table 7. Wineries membership in the All network' largest component and wines evaluations

Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to document the role performed by both independent winemaking consultants and wine guides in the evolution of the Italian wine industry. We discussed the major challenges that the change of market opportunities in terms of growing internationalisation and mass consumption of quality wines posed to producers and to established traditions in the wine industry. We suggested that independent winemaking consultants and wine guides complemented each other in opening the way to major changes in winemaking. Independent winemakers diffused a modern approach to winemaking against the resistance of the advocates of tradition. They overcame this resistance with the help of the wine guides that tended to reward those products that are more consistent with the taste of the general public rather than with the dictates of tradition. Our results support this view.

The evolution of the networks of wineries induced by the multiple affiliations of the winemakers shows how pervasive they have been in the industry, and the continuous growth of their importance. Networks get denser in the period of observation and the size of their largest connected component tends to increase from 1997 to 2006. Networks in each year are fragmented, but the network where two wineries are tied if both employed the same winemaker at any time in 1997–2006 shows a far greater connectivity and a very large connected component that includes more than 50% of the observed wineries. We did not observe which winemaking practices were introduced by each winemaker, but we provided evidence of how pervasive their intervention has been and how great is their potential to diffuse practices among small wineries.

The intervention of independent winemakers had a positive impact on the rating of the wines reviewed by the Veronelli guide. The share of winemakers whose wines were rewarded with the maximum rating of the guide increased across the observed period. Wines from wineries embedded in the ties induced by winemakers, either through their multiple affiliations (networks 1997–2006) or through their circulation among wineries (All network), obtained systematically better reviews from the guide.

Good reviews from wine guides are strongly related to the economic fortunes of wines and wineries (Roberts and Reagans, Citation2007). This lends support to our view of the role of the guides as complementary to that of independent winemakers in changing established industry traditions.

It is appropriate to point out certain limitations in our investigation. First, our study focused on data provided by one single wine guide. Extending our analysis to the reviews of other Italian wine guides would strengthen our results. Second, even though our analysis lends support to the contention that winemakers and wine guides were key in bringing innovations to the traditions of the industry, we neither directly observed the introduction of new practices in winemaking, nor assessed if these innovations differently affected distinct geographical areas and different denomination categories.

These limitations are also future research directions. Data about winemaking practices are scarce, but the Veronelli guide reports the methods of aging, among which the barrique was criticised as a break in tradition motivated by market pressures. Methods of aging are already coded in our datasets, and we will present an analysis of the diffusion of barriques in a forthcoming work. Our datasets include also the reviews of another very prominent Italian wine guide (Vini d'Italia, by Slow Food and Gambero Rosso). We plan to analyse the reviews of this second guide as well.

In our future work we will address also another issue, related to the structure of the network and the pervasiveness of independent winemakers for different geographical areas. In fact, Italian regions have different prominence in wine production. Some of them, such as Piemonte (Piedmont) and Toscana (Tuscany), enjoy an established reputation. Others became significant producers of wine very recently. Assessing the regional composition of network components across time could clarify the possibly different dynamics of winemakers' intervention (and innovation) in different geographical areas.

References

- Anderson , K. 2004 . World Wine Markets: Globalization at Work , Edited by: Anderson , K. London : Edward Elgar .

- Anderson , K. , Norman , K. and Wittwer , G. 2003 . Globalisation of the world's wine markets . The World Economy , 26 : 659 – 687 .

- Arrigoni , F. 2001 . La trasformazione di una professione: da enologo a P.R . Enotime – Fatti & Sfatti , Available at: www.enotime.it (accessed 21 August 2009)

- Benjamin , B. and Podolny , J. 1999 . Status, quality, and the social order in the California wine industry . Administrative Science Quarterly , 44 : 563 – 589 .

- Bernetti , I. , Casini , L. and Marinelli , N. 2006 . Wine and globalization: changes in the international market structure and the position of Italy . British Food Journal , 108 : 306 – 315 .

- Callon , M. , Meadel , C. and Rabeharisoa , V. 2002 . The economies of qualities . Economy and Society , 31 : 194 – 217 .

- Campbell , G. and Guibert , N. 2006 . Introduction. Old World strategies against New World competition in a globalising wine industry . British Food Journal , 108 : 233 – 242 .

- Castriota , S. and Delmastro , M. 2008 . Individual and collective reputation: lessons from the wine market . working paper n. 30, American Association of Wine Economists

- Cholette , S. , Castaldi , R. and Fredrick , A. The globalization of the wine industry: implication for old and new world producers . International Business and Economy Conference Proceedings .

- Coelho , A. and Rastoin , J. L. 2006a . Le strategies de development des grandes firmes de l'industrie mondiale du vin sur la longue période (1980–2005) (première partie) . Progrès agricole et viticole , 123 : 34 – 41 .

- Coelho , A. and Rastoin , J. 2006b . Financial strategies of multinational firms in the world wine industry: an assessment . Agribusiness , 22 : 417 – 429 .

- Delmastro , M. 2005 . An investigation into the quality of wine: evidence from Piedmont . Journal of Wine Research , 16 : 1 – 17 .

- Enotria . 2000–2007 . Il Quaderno del vino e della vite. Supplemento del Corriere Viti-vinicolo .

- Goodhue , R. , Green , R. , Heien , D. and Martin , P. 2008 . California wine industry evolving to compete in 21st century . California Agriculture , 62 : 12 – 18 .

- Guibert , N. 2006 . Network governance in marketing channels . British Food Journal , 108 : 256 – 272 .

- Hannan , M. , Negro , G. , Rao , H. and Leung , M. 2007 . “ No barrique, no Berlusconi: collective identity, contention and authenticity in the making of Barolo and Barbaresco wines ” . Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper N. 1972. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1008367 (accessed 21 August 2009)

- Hsu , G. , Roberts , P. and Swaminathan , A. 2008 . Standards for quality and the mediating role of critics . Working paper

- Karpik , L. 1989 . L'economie de la qualité . Revue Française de Sociologie , 30 : 187 – 210 .

- Karpik , L. 2000 . Le Guide Rouge Michelin . Sociologie du Travail , 42 : 369 – 389 .

- Mondo agricolo . 1996 . Doc ‘ufo’: ovvero non identificate . 2 March

- Odorici , V. and Corrado , R. 2004 . Between supply and demand: intermediaries, social networks and the construction of quality in the Italian wine industry . Journal of Management and Governance , 8 : 149 – 171 .

- Roberts , P. and Khaire , M. 2008 . Getting known by the company you keep: publicizing the qualifications and former associations of skilled employees . Industrial and Corporate Change , : 1 – 30 .

- Roberts , P. and Reagans , R. 2005 . Establishing order in markets: investigating the dual role played by critics . Working paper

- Roberts , P. and Reagans , R. 2007 . Critical exposure and price-quality relationships for New World wines in the U.S. market . Journal of Wine Economics , 2007 : 56 – 69 .

- Taplin , I. 2006 . Competitive pressures and strategic repositioning in the California premium wine industry . International Journal of Wine Marketing , 18 : 61 – 70 .

- Terra e vita . 2001 . Occorre una scelta politica . 31

- The Zinquisition . 2007 . Available at: www.zinquisition.blogspot.org (accessed 20 October 2007)

- Zhao , W. 2005 . Understanding classifications: empirical evidence from the American and French wine industries . Poetics , 33 : 189 – 200 .