ABSTRACT

Wine tourism is becoming an increasingly important tourism niche with various regions competing for tourism dollars. It is often assumed that differentiation in the sector is region based. This research investigates the positioning narratives from websites of a sample of top wine tour service firms across the US and Australia. Analysis is undertaken using an innovative methodology that combines computer-based lexical analysis followed by hierarchical clustering on principal components. The research seeks to determine the extent to which identified clusters are region based and whether the positioning narratives on websites can provides useful clusters across regions. Results are reported, implications are discussed, limitations are noted and possible areas for further research are indicated.

Introduction

Wine tourism, which combines tourism and the wine industry, has seen wineries become popular tourist attractions in several wine-growing regions across the world. The resulting synergy from the different combinations of physical, cultural and natural dimensions that provide every region with its particular experience and branding in terms of denomination of controlled origin has been referred to as touristic terroir (Hall & Mitchell, Citation2002; Hall, Sharples, Cambourne, & Macionis, Citation2000). The recognition of these characteristics has given rise to the growth of wine tourism and its recognition as an important tourism niche. Telfer (Citation2001) describes the wine tourist as interested in the ambience, regional culture, cuisine, surrounding environments and the different wine styles and varieties that are on offer. Wine tourism is very much part of the service sector and encompasses agricultural tourism, industrial tourism, rural tourism and special interest tourism (Yuan, Cai, Morrison, & Linton, Citation2005).

The Internet has transformed the tourism industry in general. It has provided platforms that have empowered customers allowing them to decide on location, book travel, accommodation and places of interest to visit completely online. Wine tourism is no exception and the increasing competition between wine regions has witnessed a proliferation of wine tourism websites that provide wine tours and experiences. Wineries in different parts of the world increasingly seek to leverage their websites to attract visitors. Marketers developing content for an effective wine tourism website need to consider various factors and characteristics of their target market. Neilson and Madill (Citation2014) observe that wine tourism websites that provide opening hours and map directions to a winery tend to attract more tourists. In addition, web design quality (Cox & Dale, Citation2002) together with the ease of navigation of a website and its readability (Mills, Pitt, & Sattari, Citation2012) are also known to be of crucial importance. However, it is questionable whether websites targeting tourists seeking a wine experience pay sufficient attention to achieving a desired positioning, possibly leading to poor differentiation and ineffective competition.

This paper sets out to investigate the positioning suggested by websites of service operators that organise wine tours and tastings across major wine regions. These websites are an important marketing tool that are employed to communicate persuasive and meaningful differences about their offering to potential customers. This study explores whether these operators rely simply on their regional origins or whether alternative positioning exists that include other meaningful clusters across regions. The research takes an innovative analytical approach that combines computer-based lexical analysis with hierarchical clustering on principal components (HCPC). Data collection is via text scraped from websites of wine tour firms in the US and Australia. Lexical analysis using the software package DICTION is employed to determine the characteristics of the narrative used by the websites to position themselves to potential customers. Results are reported, implications are discussed, limitations are noted and possible areas for further research are indicated.

Wine tourism

Various definitions for wine tourism have been suggested (e.g. Charters & Ali-Knight, Citation2002; Getz, Dowling, Carlsen, & Anderson, Citation1999) but there is no general consensus (Getz & Brown, Citation2006). Moreover, many definitions have in the past tended to adopt a wine producers’ perspective that focuses on supply side issues (Mitchell, Hall, & McIntosh, Citation2002).

However, one of the most widely used definition encountered in the literature is by Hall et al. (Citation2000, p. 3) who define wine tourism as the ‘visitation of vineyards, wineries, wine festivals and wine shows for which grape wine tasting and/or experiencing the attributes of a grape wine region, are the prime motivating factors for visitors’. Sparks (Citation2007), who conducted research in Australia, concludes that the three unique characteristics of wine tourism are destination experience, core wine experience and personal development. Wine tourism can be distinguished from other forms of service activity because it involves customers visiting a vineyard where experience of tangible and service production are essential for service benefit (O’Neill, Palmer, & Charters, Citation2002). These perspectives suggest that wine tourism can be said to consist of three major service dimensions:

The business or consumer dimension consisting of wine buffs or other buyers, eager to explore the potential of some particular vintage.

The personal education dimension, where visitors seek to better understand the complex processes underpinning wine production, or to improve their personal wine tasting skills.

The explorer dimension, where visitors are more interested in exploring the spectacular scenery, which is synonymous with many wine-producing regions.

Wine tourists are a diverse group and not all three dimensions may be equally salient for all. As Dodd and Bigotte (Citation1997) point out, there are those who are serious about wine and who ultimately travel to purchase wine but there are others who are more interested in the experience of the visit. This suggests that positioning and differentiation that goes beyond regional roots may be important.

Wine tourism and Internet channels

The development of information technology has had a huge impact on tourism with consumers increasingly searching the Internet to plan their trip (Choi, Kim, & Park, Citation2007). This development has had a significant impact generally but especially in terms of travel and accommodation choices (Law, Leung, & Buhalis, Citation2009). The wine tourism sector is no exception and Internet capabilities have also impacted this niche with both challenges and marketing opportunities. Wine producers were quick to provide websites promoting wine tourism (Neilson, Madill, & Haines, Citation2010). The initial development of the Internet in its Web 1.0 form saw many wineries focus on corporate reputation building often concurrently with direct online marketing of wine. At this point, wine tourism was viewed as a peripheral activity and primarily intended as support for wine sales. However, the arrival of Web 2.0 provided website owners with a platform that has facilitated the proliferation of social media, allowing websites, be they wineries or wine tour operators, to be linked to various independent social media channels. The latter include the most popular social networking sites: Facebook, YouTube and Instagram; together with various review websites, blogs, community-driven discussion sites and price hunting sites indicating price trade-offs. TripAdvisor is a popular social media facility for both wine consumption enthusiasts as well as travellers that enable consumers to investigate and compare various offerings. Like other social media platforms, it also allows for multi-way communication with other customers as well as with website owners. Customer reviews on independent electronic sites like TripAdvisor provide a useful marketing tool because such sites are more trusted than traditional company sites (Filieri, Alguezaui, & McLeay, Citation2015). Xie, Zhang, Zhang, Singh, and Lee (Citation2016) report that communicating back with costumers via TripAdvisor platform improves the star rating and the eWOM.

Therefore, TripAdvisor has become an important and useful social media that provides a useful reference point for many customers prior to visiting a location, whether taking a winery tour, visiting a restaurant and much more. TripAdvisor acts to reduce risk for customers who may not be too knowledgeable about or face a new purchase that they may have never or only hesitantly undertaken in the past. Wine and wine tours with their proliferation of brands and alternative tours available are very much a case in point. Social media facilities also provide a useful tool for the reduction of post-purchase dissonance by customers. However, the reliability of recommendations that appear on social media facilities can be threatened by the rising number of trolls, who post fake self-praise content, with an intention to boost sales (Filieri et al., Citation2015). Notwithstanding, dealing with a range of social media tools has become an increasingly important aspect of wine tourism marketing.

Positioning narrative

Positioning is a major challenge for any business that seeks to attract customers. It underlines the need to differentiate a product offering in the market. The long historical roots of wine with production capabilities across many regions and countries have meant a proliferation of wine brands and wineries limiting the presence of a dominant market share for any brand. It is therefore especially critical that any website, focusing on wine tourism must necessarily adopt a distinctive positioning if it is to attract customers. The notion of positioning is based on the seminal work of two advertising practitioners, who argued that: ‘positioning is not what you do to a product. Positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect. That is, you position the product in the mind of the prospect’ (Reis & Trout, Citation1986, p. 2). These authors also point out that: ‘If you didn’t get into the mind of your prospect first (personally, politically, or corporately), then you have a positioning problem’ (Reis & Trout, Citation1986, p. 21).

We live in an increasingly over-communicated world. ‘The average American is exposed to at least three thousand ads every day and will spend three years of his or her life watching television commercials’ (Kilbourne, Citation1999, p. 58). While wine aficionados may remember a little more about particular wines, other customers remember only a fraction or much less. Positioning recognises that customers are inundated with information and the typical consumer’s mind is often likened to a saturated sponge, where unless an offering stands out, it is most likely to be ignored. Finding the proverbial window to the prospects mind is indeed challenging. This is especially so in the case of wine tourism where operators risk failure if they are unable to differentiate effectively. Communication with customers can take various forms, but communication on websites and social media platforms has become increasingly critical. However for communication to stand out, it is necessary to differentiate on something that has value to customers and that can be persuasively communicated to a target market.

Persuasion is defined as ‘human communication that is designed to influence others by modifying their beliefs, values, or attitudes’ (Simons, Citation1976, p. 21). There are a number of persuasion theories in the literature (e.g. social judgment theory – Sherif & Hovland, Citation1961; Sherif, Sherif, & Nebergall, Citation1965; elaboration likelihood model – Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986, cognitive dissonance theory – Festinger, Citation1957, Citation1962). However, given the focus of this paper, narrative paradigm theory (Fisher, Citation1984, Citation1987) lends itself especially well. The theory moves away from an emphasis on rational decision-making and deductive argumentation and instead proposes narrative as a more effective means of persuasion. Significantly, a narrative must have narrative rationality to be convincing enough to permeate the receiver’s consciousness and translate into a change in action (Fisher, Citation1987). Narratives used on wine tourism website reflect actual positioning among customers whether as intended or otherwise.

Research focus

In this context, we set out to investigate whether wine tourism websites from two English-speaking regions successfully communicate persuasive and meaningful differences to their customers in their quest to clearly position their offering. Regions or touristic terroir appears to be the prevalent source of differentiation employed when discussing wine tourism. We investigate whether the narrative provided allows for the identification of differences and the extent to which these differences are region based. We therefore ask:

RQ1: Does the positioning narrative of top wine tourism websites differ between wine regions?

RQ2: Can meaningful clusters be identified from the narratives that website provide?

Methodology

An exploratory methodology that makes use of computer-based lexical analysis is employed in the pursuit of the research questions described. To qualify for inclusion in this study the US and Australian websites chosen had to have an active link to TripAdvisor and an About Us section. In the case of the US, firms in the Napa Valley region were chosen. Although this is a region not a nation, it is a popular wine tourism destination for both international and domestic tourism. Napa Valley is said to have a unique characteristic in that each winery has its own exuberant architectural style. Australia was chosen because the wine industry has since the late 1990s witnessed significant growth. In the early 2000s Australia and particularly Western Australia were perceived to be in the midst of what has been described as a wine tourism boom (O’Neill et al., Citation2002). From 2011 to 2014, it experienced a 10% increase in vineyard acreage (wineinstitute.org, Citation2015).

Although France is an important country for wine it was not chosen because it is more old word and possibly has a more noble wine reputation and because of language considerations. South Africa and New Zealand are other important wine producers but can perhaps be considered as lower in ranking Napa and Australia. Spain, Italy, Argentina, Chile, etc., were not considered because of language concerns. Online research conducted for this research showed that the US and Australian wine regions have the highest level of textual content on the Internet in the English language and have high readability.

Selected websites

Text data were collected from the ‘About Us’ section of 100 websites consisting of the top 50 wine tour operators based on their organic placing on the TripAdvisor website in each of the US and Australia. The keywords ‘wine tours’ and ‘tasting’ were used to search each of the two regions. During the collection two of the top Australian firms had to be dropped because of the absence of an ‘About Us’ section. As a result, the total sample collected consisted of data from 98 websites, 50 from the US and 48 from Australia.

Data collection

Text content data were scraped from the ‘About Us’ section that was present in the investigated websites. The ‘About Us’ section is generally dedicated to introducing and describing the firm to the reader. Nielsen and Tahir (Citation2002) posit that the ‘About Us’ section main objective is to give an overview of the company, together with links to relevant details about products or services offered by the company. Tan (Citation2013) defines the ‘About Us’ page as a personal description of the website to its visitors and should reveal the company’s background, present its products and services and differentiate companies from their competitors. It should therefore reflect the desired positioning of the firm.

Graham (Citation2013) provides detailed guidelines and suggests that companies should include the following in their ‘About Us’ section: (1) Establish a conversational tone that tells the story of the company in the same way it would be told to someone face-to-face. (2) Tell their business stories such as motivation behind the name, motivation for starting the business and what customers should expect when buying their service or product. (3) Show personality; making use of the first person and clearly putting forward the name of the company. The first point highlights the importance of the narrative in achieving persuasion while the latter two points highlight the desire to differentiate and achieve a desired positioning.

Lexical analysis

Computer-based lexical analysis, via DICTION v.7 software, has been employed to investigate the collected narratives in the About Us section where they described and introduced their firm. DICTION has been especially used in political campaigns analyses (Lowry & Naser, Citation2010), strategic management (Short & Palmer, Citation2008), leadership (Bligh, Kohles, & Meindl, Citation2004a, Citation2004b) and accounting (Wisniewski & Yekini, Citation2015). The use of DICTION in marketing is in its early stages (e.g. Aaker, Citation1997; Zachary, Mckenny, Short, Davis, & Wu, Citation2011).

DICTION was created and developed by R. Hart and Craig E. Carroll. It is described ‘as a method for determining the tone of a verbal message using a software that searches a passage for five general lexical features, defined as the five Master Variables’ (Hart, Citation2001). DICTION consists of 31 dictionaries with over 50,000 search words that can be used to analyse any type of text. DICTION processes the text by looking for exact words contained in the dictionaries. It uses dictionaries to search text for the following five master variables. Hart (Citation2001, pp. 45–46) defines the five main variables as follows:

Certainty – ‘Indicates resoluteness, inflexibility, and a completeness and a tendency to speak ex cathedra’.(p. 45)

Activity – ‘Active language featuring movement, change, the implementation of ideas and the avoidance of inertia (apathy)’(p. 46)

Optimism – ‘Language endorsing some person, group, concept or event, or highlighting their positive entailments’ (p. 45)

Realism – ‘Language describing tangible, immediate, recognizable matter that affect people’s every day lives’ (p. 46)

Commonality – ‘Language highlighting the agreed-upon values of a group and rejecting idiosyncratic modes of engagement’ (p. 46)

The scores for the five DICTION master variables are derived by converting all sub-variables to z-scores, combining them via addition and subtraction and then adding a constant of 50 to eliminate negative values. Hart (Citation2001) declares that the master variables were selected intentionally and in accordance with theoretical work of social thinkers. Short and Palmer (Citation2008, p. 732) refer to Hart (Citation2001) suggested theoretical foundations of the five diction variables and described them as follows:

Certainty – ‘Wendell Johnson (Citation1946) produced work on general semantics that looked at reasons leading to language rigidity and outcomes of this. The Certainty variable is associated with resoluteness, inflexibility, completeness and authority’.

Activity – is based on the work by Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum (Citation1957) on The measurement of meaning that examined language featuring movement, change, implementing new ideas, and avoidance of inertia

Optimism – James David Barber (Citation1992) in his book about the US Presidential Characters, noted that optimism was a fundamental factor to understand political personality. Optimism is associated with overconfidence and self-confidence (Hayward, Rindova, & Pollock, Citation2004).

Realism is based on the work of John Dewey (Citation1954) whose work examines language describing tangible, immediate, recognizable matters.

Commonality – Etzioni (Citation1993) and Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, and Tipton (Citation1991) examines language that highlights agreed-on values of a group and rejects idiosyncratic modes of engagement.

The software output provides numerical results in a file that can be used for further statistical analysis.

Analysis and results

The resultant data from the lexical analysis using DICTION was used as input to HCPC in R (R Core Team, Citation2013). This procedure first undertakes principal component analysis (PCA) that is used as a pre-processing step to the hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) that follows. PCA is an exploratory data analysis technique that is appropriate for continuous data as is the case with the resultant z-scores from DICTION. The objective of the PCA analysis is descriptive and provides a small number of uncorrelated variables while retaining as much information as possible. HCA is a specific type of clustering that combines cases into homogenous clusters by merging them together one at a time in a series of sequential steps (Blei & Lafferty, Citation2009). The analysis employed is agglomerative and defined by the similarity or measurement of the distance between cases used and the linkages between clusters (Bratchell, Citation1989). The HCA that follows the PCA in HCPC allows for better visualisation of the hierarchical tree and understanding of the data (Husson, Josse, & Pages, Citation2010).

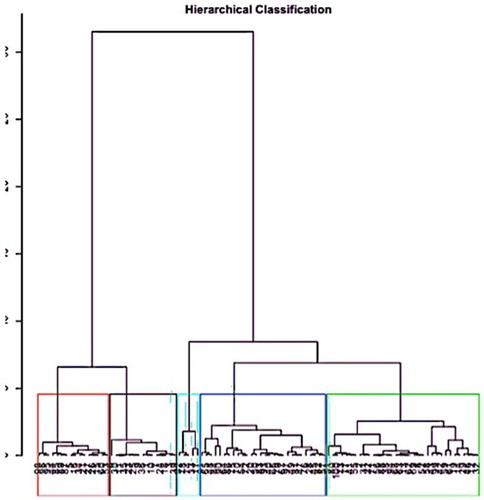

The HCPC output provides an Interia Gain plot that indicates that a 5-cluster cut-off point is most appropriate for the data being analysed. The output from the hierarchical clustering is a dendrogram that provides a visual display of the clustering process. Individual wine tour firms are sorted on the x-axis according to their coordinate on the first principal component. An inspection of the dendrogram in from the base upwards shows wine tour firms that are similar to each other joining up earlier as against those that are more dissimilar, while horizontal lines indicate the stages at which the clusters join up. Long vertical lines suggest clusters that are dissimilar from each other. Combinations of the five variables from DICTION are able to characterise the five clusters identified.

Description of the cluster by variables

The HCPC shows that four of the five DICTION variables are statistically significant namely: Realism (η2 = .83; p < .001), Certainty (η2 = .71; p < .001), Optimism (η2 = .29; p < .001) and Activity (η2 = .24; p < .001). Commonality was not found to be significant. The v.test in determines whether the mean of the category for the cluster variable is equal to the overall mean of the variable. It does this by comparing the proportion of the words in a cluster to the proportion of the words in the total data. Results for all v.tests reported are significant (p < .001) indicating differences. Negative v.test values indicate that the mean of the category is below the overall mean.

Table 1. Overall and category mean and SD scores of clusters by variables.

Description of factors by principal components

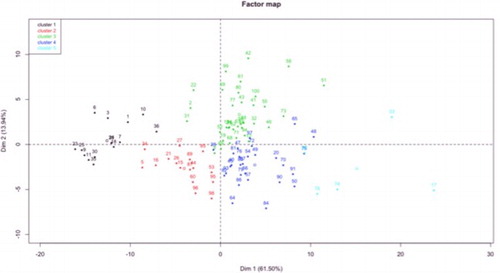

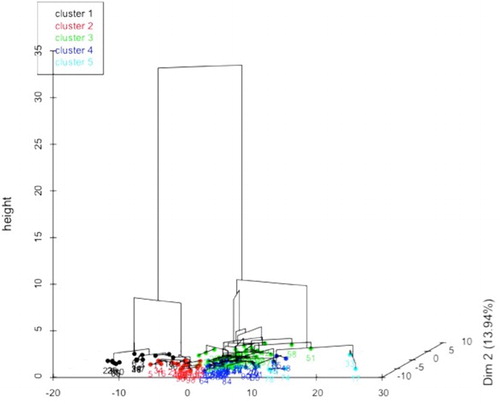

The clustering is also described by three principal components extracted, which are found to be statistically significant (Dim 1: η2 = .84, p < .001; Dim 2: η2 = .57, p < .001; Dim 3: η2 = .22, p < .001). Dimensions 1 and 2 that are used in the factor map plot in capture 75.44% of the total variance (or inertia) in the data. The combinations of dimensions are also able to describe the five clusters and provide v.test scores that are significant (p < .01) – . The partitioning of the data into the five clusters identified is depicted in the factorial map shown in with individuals coloured according to their cluster. combines and by superimposing a three-dimensional hierarchical tree on the factor map thereby providing a clearer view of the clustering.

Table 2. Overall and category mean and SD scores of clusters by principal components.

Wine tourism segmentation is often geographically based emphasising regions. The first research question asked whether the positioning narrative of top wine tourism websites differs between the wine regions investigated. To determine whether similar positioning exists across regions a cross-tabulation of the five identified clusters by the two countries considered was undertaken. Results in show that with the exception of cluster 1 that positions exclusively on Australian roots, the other clusters use elements that do not rely exclusively on their region of origin for differentiation.

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of HCPC cluster members by origin.

Cluster descriptions

To better understand the nature of the clusters identified these were further investigated. Clusters can be described in terms of individuals that are closest to the cluster centre and those that are farthest away from cluster centres. The five firms providing the experiences that are closest to the cluster centres are respectively represented by: 39 (Adelaide's Top Food & Wine Tours), 15 (Leogate Winery Tours), 41 (Bushtucker River & Wine Tours), 49 (Apex Limousines Wine Tours) and 74 (Napa Valley Wine Train Tours). A deeper look at each cluster shows important differences. Therefore:

Cluster 1 are tours that primarily emphasise the Australian roots particularly the uniqueness of the Hunter Valley and Melbourne wine regions which together with the vision of the regions’ wineries characterise the indigenous wine and provides a quality tour experience.

Cluster 2 primarily focuses on the different types of grapes that go into making the different wines and the wineries to be visited. It is clear that these tours are primarily educational targeting the wine enthusiast.

The tours that make up Cluster 3 have a diffused focus and are targeting a general touring market. They are about selling the tour and to do so they highlight a variety of elements that include the wine, wineries, estates and vineyards together with the hospitality, quality, uniqueness and managements’ commitment to the tour.

Cluster 4 emphasises both the wines and the tour. The former is described in terms of the experience as a result of the tasting and vineyard as well as the country region. The latter highlights the fun, timing service, enjoyment and uniqueness of the tour.

Cluster 5 is the smallest cluster and represents a niche positioning that focuses on family-owned wineries in the Sonoma region of the US and the Margaret River and Exmouth regions of Western Australia together with the class and quality of the wine they produce. The appeal here is primarily to wine buffs.

Therefore, with the exception of cluster 1 that has an exclusive Australian emphasis for its positioning, the other clusters use themes that have commonalities across the two wine regions. These results provide support for the second research question in this study indicating that meaningful clusters can be identified from the narratives that websites provide. These clusters exhibit positionings that extend beyond an exclusive emphasis on a particular geographical region.

Key findings and implications

Three main findings can be highlighted and considered. First, the results show that firms in cluster 1 that consist exclusively of 15 Australian wine tour operators show a marked regional basis in their positioning. These are adopting a common narrative that primarily differentiates them as Australian. However, in addition, the results also identify four additional clusters that have commonalities that extend across the two regions investigated that emphasise different elements to position their offering. Indeed, clusters 3 and 4 are the largest clusters with a broad appeal and a positioning that highlights the characteristics of the tour. Therefore, on one hand, wine tourism firms in cluster 3 position in a way that appeals to those that simply want to experience the fun, scenery and other tour characteristics while, besides the tour, firms in cluster 4 also provide some wine information details. On the other hand, clusters 2 and 5 are positioning for those who have a more focussed interests in wine and can be described as catering for enthusiasts and wine buffs, respectively.

It is clear that what these firms are saying about themselves in the About Us section of their website is providing them with a basis for differentiation. This may reflect either the unintended or the intended basis of differentiation chosen by management. It is not possible to be sure without further investigation. While it is possible that the positionings identified may not have been what the tour firms intended, it needs to be borne in mind that the firms being investigated are the top wine tour operating firms with the highest scores on TripAdvisor, suggesting that they are likely to know what they are doing.

Second, this paper demonstrates the use of an innovative methodology that combines computer-based lexical analysis using DICTION followed by HCPC. The methodology employed shows that it is possible to make use of the positioning narratives provided in the About Us section of websites to identify meaningful clusters. The successful application of this computer-based lexical analysis using DICTION provides an interesting methodology for future analysis. The results indicate that the positioning narratives available on corporate websites can be used as a useful source for managers wishing to analyse the competitive stance of competitors. Of course, any such analysis should not rely exclusively on a single source but should be augmented by other sources. The results suggest that the methodology employed that combines DICTION with HCPC is an appropriate tool that may also be employed to identify positioning narratives in other industries. In addition, the methodology offers scope for extending its use to other circumstances that include the analysis of various corporate communications with different stakeholders.

Third, this study highlights the importance of the text narrative used in website. Narrative paradigm theory (Fisher, Citation1984) provides a useful framework to marketers seeking persuasion among readers and ultimately customers. It is more effective to pursue a narrative approach where meaning and emotions can be associated rather than to seek to persuade by leveraging an assumed rational decision-making process. Fisher (Citation1987) argues that what sets humans apart is our ability to narrate stories. In his theory, the author therefore emphasises the importance of ‘narration’ that involves the use of symbolic words and actions demonstrating beliefs and values to which readers can also relate. To do so he makes use of the Greek term mythos, which he describes as ‘ideas that cannot be verified or provided in any absolute way. Such ideas arise in metaphor, values, gestures and so on’ (Fisher, Citation1987, p. 19). In addition, any narrative needs to be ‘believable’ and represent ‘good sense’ and ‘coherence’. In looking at the website narrative to include, marketers need to ensure that the narrative chosen is appropriate and that it positions the offering of wine tour operators in a way that ‘fits in’ to the culture, character, values and experiences of the target market.

Limitations and future research

The research suffers from a number of limitations. Although DICTION employs a standardised technique that allows for comparisons across different countries, it can be argued that it can be restrictive. DICTION standard dictionaries are available in the English language thereby limiting study replication possibilities to regions having web content in other languages. Similarly, clustering as an analytical technique has its limitations particularly with respect to the stability of identified clusters.

Inspection of the websites used in the analysis indicates that some provide less information than others and they may therefore not be in conformity with good practice for ‘About Us’ sections as discussed earlier (cf. Graham, Citation2013; Nielsen & Tahir, Citation2001; Tan, Citation2013). In these circumstances, their resultant scores on the five DICTION master variables would tend to be close to the mean, with none of the five master variables being salient. However, a failure by marketers to highlight a predetermined desired positioning is also a positioning, in that readers will position the firm on the basis of what is available.

Finally, besides text, many websites are increasingly making use of videos to visually position themselves to potential customers. This aspect has not been taken into consideration in this study. Future research could consider this feature. In this respect, are video clips and pictures more effective than the detailed text that is synonymous with what has become a mandated ‘About Us’ section on websites? How satisfied are potential visitors with a more text-based form of website? Is there a particular pattern of how potential customers go about undertaking their search for a wine tour? A better understanding of some of these issues would go a long way in helping wine tourism firms more effectively position themselves in the market.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 347–356. doi: 10.2307/3151897

- Barber, J. D. (1992). The presidential character: Predicting performance in the white house (p. 262). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1991). The good society. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Blei, D., & Lafferty, J. (2009). Topic models. In A. Srivastava, & M. Salami (Eds.), Text mining: Classification, clustering and applications (pp. 71–94). Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Bligh, M. C., Kohles, J. C., & Meindl, J. R. (2004a). Charisma under crisis: Presidential leadership, rhetoric, and media responses before and after the September 11th terrorist attacks. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(2), 211–239. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.02.005

- Bligh, M. C., Kohles, J. C., & Meindl, J. R. (2004b). Charting the language of leadership: A methodological investigation of president bush and the crisis of 9/11. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 562–574. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.562

- Bratchell, N. (1989). Cluster analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 6, 105–125. doi: 10.1016/0169-7439(87)80054-0

- Charters, S., & Ali-Knight, J. (2002). Who is the wine tourist? Tourism Management, 23(3), 311–319. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00079-6

- Choi, C., Kim, S., & Park, Y. (2007). A patent-based cross impact analysis for quantitative estimation of technological impact: The case of information and communication technology. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 74(8), 1296–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2006.10.008

- Cox, J., & Dale, B. G. (2002). Key quality factors in web site design and use: An examination. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 19(7), 862–888. doi: 10.1108/02656710210434784

- Dewey, J. (1954). Evolution and ethics. The Scientific Monthly, no. 78, pp. 57–66.

- Dodd, T., & Bigotte, V. (1997). Perceptual differences among visitor groups to wineries. Journal of Travel Research, 35(3), 46–51. doi: 10.1177/004728759703500307

- Etzioni, A. (1993). The spirit of community: The reinvention of American society. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207(4), 93–106. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1062-93

- Filieri, R., Alguezaui, S., & McLeay, F. (2015). Why do travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust towards consumer-generated media and its influence on recommendation adoption and word of mouth. Tourism Management, 51, 174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.007

- Fisher, W. R. (1984). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs, 51, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/03637758409390180

- Fisher, W. R. (1987). Human communication as a narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value, and action. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

- Getz, D., & Brown, G. (2006). Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tourism Management, 27, 146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.08.002

- Getz, D., Dowling, R., Carlsen, J., & Anderson, D. (1999). Critical success factors for wine tourism. International Journal of Wine Marketing, 11(3), 20–43. doi: 10.1108/eb008698

- Graham, S. (2013). How to write great ‘About Us’ page content. Retrieved from www.shawngraham.me

- Hall, C.M. & Mitchell, R. (2002). The touristic terroir of New Zealand wine: The importance of region in the wine tourism experience. In A. Montanari (Ed.), Food and environment: Geographies of 'taste’ (pp. 69–91). Rome: Societa Geografica Italiana.

- Hall, C. M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B., & Macionis, N. (2000). Wine tourism around the world. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Hart, R. P. (2001). Redeveloping diction: Theoretical considerations. In M. D. West (Ed.), Theory, method, and practice in computer content analysis, Vol. 16. Progress in communication sciences (pp. 43–60). London: Ablex.

- Hayward, M. L. A., Rindova, V. P., & Pollock, T. G. (2004). Believing one’s own press: The causes and consequences of CEO celebrity. Strategic Management Journal, 25(7), 637–653. doi: 10.1002/smj.405

- Husson, F., Josse, J., & Pages, J. (2010). Principal component methods-hierarchical clustering-partitioned clustering: Why would we need to choose for visualizing data. Applied Mathematics Department.

- Johnson, W. (1946). People in quandaries: The semantics of personal adjustment. New York, NY: International Society for General Semantics, previously published.

- Kilbourne, J. (1999). Deadly persuasion: Why women and girls must fight the addictive power of advertising. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Law, R., Leung, R., & Buhalis, D. (2009). Information technology applications in hospitality and tourism: A review of publications from 2005 to 2007. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 26(5–6), 599–623. doi: 10.1080/10548400903163160

- Lowry, D. T., & Naser, M. A. (2010). From Eisenhower to Obama: Lexical characteristics of winning versus losing presidential campaign commercials. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 87(3–4), 530–547. doi: 10.1177/107769901008700306

- Mills, A. J., Pitt, L., & Sattari, S. (2012). Reading between the vines: Analyzing the readability of consumer brand wine web sites. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 24(3), 169–182. doi: 10.1108/17511061211259170

- Mitchell, R., Hall, C. M., & McIntosh, A. (2002). Wine tourism around the world: Development, management and markets (p. 115). Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann.

- Neilson, L. C., Madill, J., & Haines Jr, G. H. (2010). The development of e-business in wine industry SMEs: An international perspective. International Journal of Electronic Business, 8(2), 126–147. doi: 10.1504/IJEB.2010.032091

- Neilson, L., & Madill, J. (2014). Using winery web sites to attract wine tourists: An international comparison. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 26(1), 2–26. doi: 10.1108/IJWBR-07-2012-0022

- Nielsen, J., & Tahir, M. (2002). Homepage usability: 50 websites deconstructed (Vol. 50). Indianapolis, IN: New Riders.

- O’Neill, M., Palmer, A., & Charters, S. (2002). Wine production as a service experience – the effects of service quality on wine sales. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(4), 342–362. doi: 10.1108/08876040210433239

- Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral roles to attitude change. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

- Reis, A., & Trout, J. (1986). Positioning: The battle for your mind. How to be seen and heard in the overcrowded marketplace. New York, NY: Warner Books.

- Sherif, C. W., Sherif, M., & Nebergall, R. E. (1965). Attitude and social change. Philadelphia: W. B Saunders.

- Sherif, M., & Hovland, C. I. (1961). Social judgement. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Short, J. C., & Palmer, T. B. (2008). The application of DICTION to content analysis research in strategic management. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 727–752.

- Simons, H. W. (1976). Persuasion: Understanding, practice, and analysis. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Sparks, B. (2007). Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1180–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.11.003

- Tan, G. (2013). The ecommerce authority. Retrieved from www.onlinebusiness.volusion.com

- Telfer, D. J. (2001). Strategic alliances along the Niagara wine route. Tourism Management, 22(1), 21–30. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00033-9

- Wine Institute. (2015). Statistics – The Wine Institute. Retrieved from http://www.wineinstitute.org/resources/statistics

- Wisniewski, T. P., & Yekini, L. S. (2015). Stock market returns and the content of annual report narratives. Accounting Forum, 39(4), 281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.accfor.2015.09.001

- Xie, K. L., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Singh, A., & Lee, S. K. (2016). Effects of managerial response on consumer eWOM and hotel performance: Evidence from TripAdvisor. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 2013–2034. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2015-0290

- Yuan, J. J., Cai, L. A., Morrison, A. M., & Linton, S. (2005). An analysis of wine festival attendees’ motivations: A synergy of wine, travel and special events? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(1), 41–58. doi: 10.1177/1356766705050842

- Zachary, M. A., McKenny, A. F., Short, J. C., Davis, K. M., & Wu, D. (2011). Franchise branding: An organizational identity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(4), 629–645. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0252-7