ABSTRACT

Teaching through a second language (L2) poses many challenges, as second language learners (SLLs) have fewer linguistic resources in the language of instruction. Scaffolding students’ learning is a possible way of overcoming these challenges, but there are few studies on this in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) contexts. The present study suggests a framework for how to empirically identify and classify scaffolding. Using the framework, the study investigates how three Norwegian CLIL teachers support learning for second language learners (SLL) through scaffolding. Twelve lessons (science, geography and social science) were filmed in one 11th-grade CLIL class. A coding manual (PLATO) was used to identify the scaffolding strategies the teachers used. The findings indicate that CLIL teachers scaffold their students to comprehend material. However, they provide few strategies to help students solve tasks, such as modelling and strategy use. CLIL teachers scaffold differently in the natural and social sciences; the natural science teaching has more visual aids, whereas the social science teachers allows for more student talk. The results imply that natural and social science teacher complement each other. However, CLIL teachers need to create more specific learning activities to provide their students with more support.

Introduction

This study investigates how teachers use scaffolding strategies to support students learning English L2 in a content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classroom. CLIL is a bilingual teaching approach defined as an additional language integrated into a non-language subject (Coyle, Hood and Marsh Citation2010: 1). CLIL students have greater difficulties learning material than L1 students because they learn material at the same level as L1 students but with larger language deficits in the language of instruction (Cummins and Early Citation2015). CLIL teachers are generally untrained in teaching second language learners (SLLs), and they express concerns about how to teach them (Pérez-Cañado Citation2016). SLL researchers claim that scaffolding is a promising way to help SLLs (Gibbons Citation2015; van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen Citation2010). By using scaffolding strategies, CLIL teachers can integrate language learning into content subjects (Pawan Citation2008), thus exploring meaning negotiation and linguistic assistance in the classroom. This is crucial to the language development of SLLs (Kayi-Aydar Citation2013). However, even though many SLL researchers note the potential benefits of scaffolding to SLLs, the research on CLIL is disparate and limited (Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018). There is a need for empirically grounded studies on naturally occurring CLIL teaching in order to map out how content teachers scaffold. The current study suggests a framework for how to identify and classify scaffolding based on previous literature from ELL and CLIL contexts. A coding manual is employed to identify scaffolding in video-recorded classroom interaction in a CLIL classroom in which science, geography, and social science is taught. The main unit of analysis is the interaction between the teacher and the students. The study contributes to unifying an understanding a scaffolding in the classroom, and mapping what the teachers do and do not do to scaffold the students’ learning. The results may be used to further discuss how CLIL teachers may more effectively support their students in their learning processes. This study is guided by the following research question: Which scaffolding strategies do three CLIL teachers use to help their L2 English students comprehend material and complete tasks?

Theoretical background of scaffolding

The current section aims to clarify what is meant by the term ‘scaffolding’ in a classroom context, and how this term is understood in this study. Bruner introduced the term scaffolding in an educational sense in the 1970s. It refers to the ‘interactional instructional relationship’ between adults and learners that ‘enables a child or novice to solve a problem […] beyond his unassisted efforts’ (Wood, Bruner and Ross Citation1976: 90). Scaffolding has its roots in psychology but has since expanded into the educational sciences. Due to its flexible nature, scaffolding is a broad concept. Some researchers understand scaffolding as a new metaphor for Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, placing it firmly in sociocultural theory (Bliss, Askew and Macrae Citation1996; Smagorinsky Citation2018; Verenikina Citation2004). Others insist on further developing it as a tool to use in the classroom, leaning toward more constructivist approaches (Hogan and Pressley Citation1997).

Researchers generally agree that the goal of scaffolding is student autonomy (van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen Citation2010), which is realised through tailored support from a teacher or more capable peer and involves the responsibility of learning slowly transferring from the teacher to the student (Lin et al. Citation2012). This study uses Maybin, Mercer and Stierer’s (Citation1992) definition of scaffolding: a type of teacher assistance that helps students learn new skills, concepts, or levels of understanding (hereafter comprehension of material) that leads to the student successfully completing a task (‘a specific learning activity with finite goals’) (188).

The field of SLL largely takes a practical approach to scaffolding by identifying what teachers do or should do (Echevarría, Vogt and Short Citation2017; Gibbons Citation2015; Masako and Hiroko Citation2008). Scaffolding strategies operate from a macro level (e.g. curriculum planning that integrates language systematically) to a micro level (i.e. interactional scaffolding). Interactional scaffolding is the minute-to-minute support teachers give their students in the classroom (van Lier Citation2004: 148). Interactional scaffolding poses a challenge to teachers because they must support students with unpredicted problems on the spur of the moment (Many et al. Citation2009; Walqui Citation2006). The present study focuses on scaffolding strategies CLIL teachers use during interactional scaffolding.

A framework for analysing scaffolding

As viewed above, there are numerous complex understandings of what scaffolding is. In order to empirically identify scaffolding, this article has synthesised SLL studies that explicitly investigate scaffolding in the ESL/EFL classroom to create a framework for analysing scaffolding. The majority of SLL scaffolding research is qualitative and descriptive and takes place in naturally occurring teaching (Lin et al. Citation2012). SLL researchers typically create their own frameworks in a bottom-up approach to identify scaffolding practices in the classroom (Gibbons Citation2003; Kayi-Aydar Citation2013; Li Citation2012). The main unit of analysis is the dialogue between teachers and students, although some studies include non-verbal behaviour and gestures (Miller Citation2005). Most SLL studies use video observation and create coding schemes (e.g. Ajayi Citation2014; van de Pol and Elbers Citation2013). Researchers use vastly divergent conceptualisations, approaches and terms – in other words, they measure disparate items. As van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen (Citation2010: 287) put it, ‘the measurement and analysis of scaffolding still appears to be in its infancy’. To move forward, they suggest agreeing on a clear conceptualisation of scaffolding and how to empirically operationalise and measure it.

Since there are many rich descriptions of scaffolding, the current study aims to research scaffolding in a top-down manner by building on existing literature to work toward a more unified understanding of scaffolding. The following section synthesises SLL research in five emerging themes that researchers have used to describe how SLL teachers practice interactional scaffolding (). The framework builds on literature primarily from English language learner (ELL) contexts and CLIL contexts. ELLs and CLIL students represent two of the largest SLL groups and were therefore chosen for the scaffolding framework. ELL contexts refer mainly to immigrant students who come to North America and learn English as a second language, studying the same content subjects as L1 students (see Echevarría, Vogt and Short Citation2017; Gibbons Citation2015; Walqui Citation2006, for examples of students). CLIL students refer to students mostly in Europe, who speak the majority language of the country (e.g. Norwegian in Norway), and together with the teacher, speak the L2, which is most frequently English (Lasagabaster and Sierra Citation2009; Nikula and Mård-Miettinen Citation2014). There are several differences between these learner groups; for instance, CLIL students are often selected from high socioeconomic backgrounds, and share a common L1 with the teacher (Bruton Citation2011). The teachers also have different foci; ELL teachers must accommodate to English L1 and L2 speakers simultaneously in the classroom, and CLIL teachers have language learning goals in addition to content (Coyle Citation2007; Pawan Citation2008). Even though these contexts are different, the language learning mechanism still remains the same: students have the same linguistic deficiencies in the L2. Since the ELL literature is much larger, it is used as a resource to draw upon for further CLIL research as well.

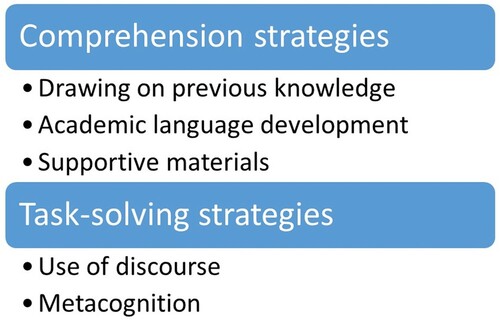

Figure 1. Mahan’s classification of SLL scaffolding strategies, modified from Maybin, Mercer and Stierer (Citation1992).

The literature review focuses on five scaffolding themes related to comprehending material and solving tasks, following Maybin, Mercer and Stierer’s (Citation1992) classification of scaffolding (see ). This classification of scaffolding was used because it provides clear goals for scaffolding. The five emerging themes also correspond to the coding manual (Protocol for Language Arts Teaching Observation [PLATO]) used in this research and presented in the methods section. In what follows, each emerging theme will be discussed. The methods section will explain how PLATO empirically measures these emerging themes in the present study.

Comprehension strategies in SLL scaffolding

Scaffolding that aids comprehension emphasises how to help students understand new material (Maybin, Mercer and Stierer Citation1992). Pawan (Citation2008) found that content teachers generally focus little on comprehension scaffolding strategies (as little as 28%). The first emerging theme to support comprehension draws on the previous knowledge of SLLs to introduce new material (Walqui Citation2006). In PLATO, this concept is known as ‘connecting to prior knowledge’ (Grossman Citation2015). It stems from the idea that SLLs are not ‘empty vessels’ but that they bring with them ‘a collection of prior knowledge and skills acquired in their native language’ (Dong Citation2017: 145). Linking known knowledge to unknown knowledge is pivotal, as prior knowledge is one of the most important factors in student learning (Tomlinson and Moon Citation2013: 421). Examples of comprehension strategies include assessing what students already know, referring to prior lessons, or using relatable real-world examples. Gallagher and Colohan (Citation2017) argue that L1 can be a powerful scaffolding strategy in CLIL contexts (in which students and teachers have a common L1 and cultural background). Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard (Citation2018) and Dalton-Puffer (Citation2007) have found that CLIL teachers frequently use L1 as a resource for helping students comprehend, drawing connections between concepts in L1 and L2.

The second emerging theme concerning comprehension is the role of supportive materials (Gibbons Citation2015; Walqui Citation2006). Supportive materials comprise visual aids, graphic organisers, use of body language, and other items to help students understand language in context (Grossman Citation2015). Academic language can be more difficult to acquire because one often cannot infer the meaning of an academic word from context (Cummins Citation2013). Walqui (Citation2006) asserts that SLLs therefore require rich extralinguistic contexts and supportive materials to ‘construct their understanding on the basis of multiple clues and perspectives’ (169). Boche and Henning (Citation2015) describe how a teacher of 11th- and 12th-grade history used supportive materials to scaffold. By contextualising texts with visual aids, sounds, and other ways of organising information, the teacher helped students understand content. Likewise, Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard (Citation2018) investigated supportive materials in CLIL teaching. They found that CLIL science teaching involved visual aids, graphic organisers, and film clips that help students understand abstract concepts.

The third emerging theme is how to support SLL’s academic language development so students can use correct terminology (cf. Meyer et al. Citation2015; Meyer and Coyle Citation2017; Morton Citation2015). Gibbons (Citation2015) suggests that although academic language is also new to L1 students, they have a clear advantage because they have a solid linguistic foundation. Scaffolding strategies include allowing students to use their own words to describe terminology; bilingual translations, and so forth (Barr, Eslami and Joshi Citation2012). Ajayi (Citation2014) found that Mexican-American ELLs learned vocabulary more efficiently when their English teacher employed explicit scaffolding strategies that targeted academic language. Researchers have found that vocabulary teaching can be implicit in CLIL contexts because CLIL teachers are often not language teachers (Dalton-Puffer Citation2007; De Graaff et al. Citation2007). However, one Norwegian study revealed a ninth-grade English L2 CLIL math and science class in which the CLIL teachers used several scaffolding strategies to support academic language development (Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018).

Task-solving strategies in SLL scaffolding

Task-solving strategies comprise scaffolding strategies aimed at helping students complete a specific learning activity (Maybin, Mercer and Stierer Citation1992). Pawan (Citation2008) found that 70% of scaffolding (as self-reported by SLL content teachers) focuses on completing content-related tasks. The fourth theme is how teachers use discourse as a supportive tool to help students with tasks (cf. Gibbons Citation2003; Kayi-Aydar Citation2013). According to McNeil (Citation2011), key scaffolding strategies include revoicing (repeating the student’s answer in academic language), repetition (echoing a student’s answer in class), and elaboration (prompting the student to justify or lengthen their answer) (398). Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard (Citation2018) provide evidence of these three scaffolding strategies in CLIL teaching, but they found more strategies in mathematics than in science. The science discourse included more patterns of Initiation-Response-Evaluation (IRE). McNeil (Citation2011), Dalton-Puffer (Citation2007), and Banse et al. (Citation2017) have investigated types of teacher questions in ELL/CLIL classrooms. They differentiate between referential questions (in which the teacher does not know the answer) and display questions (in which the teacher knows the answer) (definitions taken from Long and Sato Citation1983). All three studies conclude a significant amount more of display questions than referential questions. Referential questions are more relevant for language learning because they prompt students to form longer and more complex sentences (Farooq Citation2007). The overabundance of display questions, particularly in the natural sciences, indicates that students do not have many opportunities in which to speak or use L2 creatively (Banse et al. Citation2017; Lemke Citation1990; McNeil Citation2011).

The fifth and final emerging theme is metacognition, or ‘learning to learn’ (Coyle, Hood and Marsh Citation2010: 29). This theme focuses on how teachers support students in completing tasks by making students aware of their own learning processes (Gaskins et al. Citation1997). Research suggests that one of the most effective ways of creating independent students is by showing them how to solve tasks (Gritter, Beers and Knaus Citation2013; van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen Citation2010). This could range from modelling and providing strategies to create tangible tasks (e.g. physical objects that the students produce), to modelling how to create an effective and respectful discussion (Grossman Citation2015). In science teaching, metacognition has been emphasised in 72% of scaffolding frameworks (Pawan Citation2008). Scaffolding strategies that target metacognition include providing examples of tasks and discussing them (e.g. modelling) and suggesting meta-strategies to help students complete tasks (Grossman Citation2015). In CLIL contexts, only two studies have focused on metacognition. These studies were conducted in Basque Country on fifth- and sixth-grade English L2 science students (Ruiz de Zarobe and Cenoz Citation2015; Ruiz de Zarobe and Zenotz Citation2017). The studies conclude that reading strategies have a moderate impact on reading comprehension and that they encourage the use of strategies in completing tasks. The results of the studies indicate that metacognition can be a powerful tool for the learning process in the CLIL classroom.

In conclusion, many aspects of scaffolding have been examined in SLL classrooms, but very few studies have used similar tools to investigate scaffolding. Scaffolding is a more comprehensive field in ELL literature than in CLIL (Gibbons Citation2015; Walqui Citation2006). CLIL is only now starting to look at the role of scaffolding to support learning, and there is a need for more systematic, empirical research to describe how CLIL teachers scaffold their students’ learning (Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018; Ruiz de Zarobe and Zenotz Citation2015). The present study addresses this need by observing how three Norwegian CLIL teachers scaffold learning for their students in English L2.

Methods

The present study is an analysis of 12 video-recorded lessons from 1 CLIL classroom in which 3 CLIL subjects (science, geography, and social science) were taught. It was filmed over the span of one month during the 2015–2016 school year. The video data were transcribed and coded with an observation manual (PLATO). The research design was developed and validated by the Linking Instruction and Student Achievement (LISA) team, University of Oslo (Klette, Blikstad-Balas and Roe Citation2017).

Sample

The sample was an 11th-grade CLIL class at an upper secondary Norwegian school (ages 15–16). It was a convenience sample, as only 4–7% of upper secondary schools in Norway offer some form of CLIL teaching (Svenhard et al. Citation2007). The school offered an English CLIL programme for science, geography, and social science. Students apply for the CLIL programme and are accepted based on their grades. The participants in this study were the science, geography, and social science teachers (n = 3) and the CLIL students (n = 25). All the teachers and students were female, and most had Norwegian as their L1. The CLIL teachers had one to two years of experience teaching CLIL, and two had attended CLIL courses. Three CLIL subjects were chosen for cross-comparison to see if the CLIL teachers scaffolded similarly to the same class regardless of subject (see Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018).

Data collection and analysis

Video recordings were used for this study, as they allow researchers to systematically investigate complex educational settings (Snell Citation2011) and because they are useful in studying interactional scaffolding (van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen Citation2010). The CLIL classroom was filmed using two cameras: one small camera mounted in the back of the classroom, and one above the blackboard. The teacher wore a microphone; another was placed in the middle of the classroom to capture student utterances.

The video data were analysed with PLATO, which is a teacher-centred observation manual that describes 12 aspects (here called ‘elements’) of teaching (Grossman et al. Citation2013). PLATO classifies elements on a scale from 1 to 4. Raters assign scores for every 15-minute segment of video data (approximately 10 segments per subject in this study). A score of 1 or 2 signifies low-end teaching, and a score of 3 or 4 signifies high-end teaching. Low-end teaching indicates no evidence (score 1) to little evidence (score 2) of an element, whereas high-end teaching indicates limited evidence (score 3) to strong and consistent evidence (score 4). This study uses the percentage of segments that score within high-end teaching. For example, a score of 80% means that eight of the 10 segments scored a 3 or 4. PLATO was chosen because it is a useful tool with which to identify, label, and measure teaching practices across subjects, and the scaffolding field calls for reliable and valid instruments of measurement (van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen Citation2010). Six of the PLATO elements correspond well with the emerging scaffolding themes (see ), allowing the researcher to accurately score them. PLATO was originally created for language arts teaching but has been used to study science and mathematics teaching, and it takes SLLs into account (see Cohen Citation2018; Klette, Blikstad-Balas and Roe Citation2017; Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018).

Six PLATO elements were selected to identify various scaffolding strategies in CLIL teaching. Three elements captured comprehension scaffolding strategies (connections to prior knowledge, supportive materials, and academic language). Three others captured task-solving strategies (uptake of student responses, strategy use and instruction, and modelling and use of models). Each element in the video data was identified, scored, and described. defines each element and what constitutes each score. All definitions are taken from Grossman (Citation2015).

Table 1. Classification of scaffolding strategies and how they were scored in PLATO.

Research credibility and ethics

In accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Norwegian Center for Research Data, the teachers and students were informed orally and in writing about the project, and they each provided written consent (NESH Citation2006). A certified PLATO rater coded the video data. A second certified PLATO rater double-scored 25% of the video data to ensure reliability (interrater reliability = 90%). PLATO provided a useful lens with which to observe and interpret the aspects of scaffolding (Klette and Blikstad-Balas Citation2018). PLATO is supported by years of research on effective teaching, and using it will allow for comparison with other research that uses the same tool (Klette and Blikstad-Balas Citation2018; Klette, Blikstad-Balas and Roe Citation2017; Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018). However, using a manual with pre-determined codes may have limited the researcher’s perception of scaffolding, and cannot measure the effect of the scaffolding strategies on the students’ learning processes. The limited sample does not allow for generalizability.

Findings

The findings indicate that CLIL teachers employ an array of scaffolding strategies to help students comprehend material, but they employ limited strategies to help students complete tasks. The CLIL teachers frequently make connections between known and unknown material, provide the students with supportive materials, and consistently use, define, and prompt subject-specific terminology. The teachers consistently engage in dialogue that helps students solve tasks. However, there is limited evidence of strategies and models (metacognition).

Comprehension scaffolding strategies

Connections to prior knowledge (CPK)

The CLIL teachers consistently create connections between known and unknown material (high-end teaching, score 3–4, science 80%, geography 50%, social science 46%). Prominent scaffolding strategies include asking students if they are familiar with concepts, making explicit links to previous lessons, and using real life or personal examples.

The science teacher in particular refers to observable, scientific phenomena, e.g. she asks the students what happens when the students cut an apple in half. The geography teacher uses geographical land formations with which the students are familiar. The social science teacher prompts students to draw on everyday experiences to understand sociological phenomena, such as discussing how the students have resocialized from lower to upper secondary school.

In the following excerpt, the science teacher illustrates a redox reaction (new topic) by dropping a sink nail into copper chloride. She draws on the students’ prior knowledge to guess what will happen, and why redox reactions are relevant for Norwegians:

Excerpt 1 (Science, Connections to Prior Knowledge, score 4):

Here, the science teacher uses several tools to elicit and refer to prior knowledge. She creates a clear link between known material (what they know about copper) and how this is relevant to the unknown material (redox reactions). The segment scores a 4 because the new material builds explicitly on prior knowledge (see for more information).

Supportive materials

There is a large difference among the CLIL teachers’ use of supportive materials (science 60%, geography 90%, social science 18%). The most striking difference is the role of video clips and animations to show phenomena in the natural sciences. The science and geography teacher consistently use body language to illustrate the meanings of words. The science teacher uses Bohr models and the periodic table as aids for helping students understand the compositions of atoms. She shows a webpage that allows users to build atoms by adding and subtracting electrons and protons. The geography teacher uses instructional videos and pictures to illustrate geographical phenomena. The use of instructional videos allows students to see how land formations occur over time. She introduces a video clip with a song about erosion. She uses her hands and fingers to physically demonstrate the meaning of words, such as ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’. Finally, the social science teacher uses a graphic organiser to help students categorise terminology, but she does not use other supportive materials.

Academic language

Academic language is present in all lessons, and the teachers employ many scaffolding strategies to support academic language development (science 60%, geography 90%, social science 54%). Geography concentrates the most on the meanings of many terms, and it provides the students with the most opportunities to discuss terminology. All the teachers appear highly aware of academic language, and most lessons centre around terminology. Throughout the lessons, students must identify, define, and explain subject-specific terminology. The teachers strategically use L1 to provide bilingual translations. The science and geography teacher frequently ask for definitions of subject-specific terminology, whereas the social science teacher asks how students personally interpret abstract concepts (see excerpt 2).

In the next excerpt, the geography teacher began the lesson by moving from one topic (weathering) to a new topic (erosion). The students were given two minutes to discuss the difference between these topics in groups, and now they have a classroom discussion:

Excerpt 2 (Geography, Academic Language, score 4):

There is a high use of terminology in the excerpt. An interesting observation is the tension between everyday explanations of scientific terminology (e.g. ‘weathering is breaking’). The segment scores a 4 because the teacher consistently introduces, defines, and prompts terminology and because the students have many opportunities to use their own definitions.

Task-solving scaffolding strategies

Uptake of student responses (UP)

The students have many opportunities to speak, and the teachers often expand on their ideas (science 50%, geography 60%, social science 91%). The teachers revoice student answers into academic language, prompt students to elaborate, and use student examples to further build on ideas and concepts. However, there is a noticeable difference between the natural sciences (science and geography) and social science. Science and geography are characterised by display questions with yes/no answers half of the time, which leads to briefer student responses. This in turn leads to several IRE sequences. The social science teacher poses more referential questions and allots more time to open classroom discussions. The next excerpt is from social science. In this excerpt, the students are working in groups to discuss the difference between the terms ‘rule’ and ‘law’. The teacher stops by a group to see what they are discussing:

Excerpt 3 (Social Science, Uptake of Student Responses, score 4)

The student responses are long and not teacher-directed. The teacher responds by building on student ideas and revoicing ideas in academic language. The teacher does not pose any questions, but the task allows students to explain how they understand terminology. The segment scores a 4, as the teacher is consistently referring to and building on student ideas.

Strategy use and instruction (SUI)

There is little evidence of strategy instruction except in science (science 40%, geography 0%, social science 18%). This means that, overall, CLIL students are provided little explicit and detailed instruction on strategies to help them complete tasks.

Modelling and use of models (MOD)

No models were found, and there are limited instances of modelling (science 30%, geography 30%, social science 27%). Modelling consists of walkthroughs in which the teacher asks students to define terminology and later models an answer. The teachers do not decompose features of modelling (i.e. point to specific features) to explicitly illustrate what they are doing

Discussion

This study has sought to shed light on how CLIL teachers scaffold their students’ learning by identifying what SLL scaffolding is, and labelling the teachers’ scaffolding strategies during interaction. The findings indicate that CLIL teachers provide many scaffolding strategies with which to comprehend material. This is realised through linking concepts in L1 and L2, defining and prompting students to use subject-specific terminology, and the use of visual aids. Some of these strategies have been identified in previous CLIL literature (Dalton-Puffer Citation2007; Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018). They stand in contrast to Pawan (Citation2008)’s study, which suggests that content teachers in ELL classrooms only use scaffolding strategies for comprehending material 28% of the time. Nineteen per cent of ELL teachers expressed that aiding ELLs in comprehending material was not their responsibility. This may suggest a contrast between CLIL and ELL teaching: CLIL teachers are more preoccupied with students understanding the material, perhaps because all their students are SLLs. In ELL contexts (i.e. immigrant students placed in classrooms with L1 students), the needs of ELLs may be overshadowed by the needs of L1 students.

On the other hand, the findings show that CLIL teachers use limited strategies to help students solve tasks (metacognition). It is worth noting that the students do not create any tangible products (texts, posters, presentations) in the course of the 12 hours. They are largely discussing and trying to comprehend material. This may lead to a lack of strategies and modelling for students to complete tasks. However, the teachers could have provided suggestions for how to conduct a discussion, or modelled how to define words more clearly.

Subject-specificity in CLIL teaching

An important finding is the divide in the use of scaffolding strategies between natural sciences (science and geography) and social science subjects. This divide may be explained by the historicity and nature of the subjects – the way they have been developed, practised, and taught over the years (Nikula et al. Citation2016). The natural sciences provide multiple supportive materials, whereas social science provides limited supportive materials, which is in line with Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard (Citation2018). This difference incidentally makes natural sciences more understandable, as they provides students with contextual clues. The social science teaching, in turn, has more in-depth conversations. Discussions are student-led, have fewer IRE patterns, and provide more referential questions. This leads to longer stretches of student speech and allows students to expand more on their ideas. Several studies have found an overabundance of display questions and IRE patterns in the natural sciences (Lemke Citation1990; McNeil Citation2011; Mortimer Citation2003). Some researchers believe that the IRE pattern is incompatible with tenets of scaffolding, as it may stifle student autonomy and shorten student answers (Kinginger Citation2002; Walqui Citation2006). However, others have argued that the IRE pattern in itself is a scaffold, providing a predictable speech sequence (Silliman and Wilkinson Citation1994).

Although some of the scaffolding elements in PLATO score similarly, the teachers may still use different strategies. Science uses the most real-world examples to connect to prior knowledge, reflecting that it is a subject that expresses how the world works (Mortimer Citation2003). Geography connects to national and local knowledge, showing that it is a subject that builds national identity (Sætre Citation2013). Lastly, social science relates to more personal examples, relating to its promotion of civic competence (Torrez and Claunch-Lebsack Citation2013). These findings highlight the importance of subject-specificity in teaching. Natural science and social science subjects provide different types of support for SLLs, and these differences appear to complement each other.

Conclusion

This study has used existing literature to create a framework with which to study scaffolding. The framework () has proven to be a useful analytical tool to empirically identify interactional scaffolding in the CLIL classroom. In this study, 12 hours of CLIL teaching were observed, and scaffolding strategies were identified with a coding manual to determine which scaffolding strategies three CLIL teachers use to help their students comprehend material and solve tasks. The findings indicate that CLIL teachers use a variety of scaffolding strategies in science, geography, and social science. Many of the scaffolding strategies pertain to comprehension, in which the teachers show connections between known and unknown knowledge, use supportive materials, and define and prompt academic language. The teachers build on student ideas to help students solve tasks, but they show little evidence of metacognition. There are further differences between how teachers scaffold in the natural sciences and social sciences. One implication from the findings is that context is important: there are clear differences between how CLIL and ELL teachers scaffold. The homogeneity of CLIL teachers and students allows them to better scaffold the comprehension of material, since they have similar points of reference. However, these teachers show less evidence of scaffolding the solving of tasks. Lastly, this study suggests that content teachers support their L2 students even when they do not have a background in language teaching.

The strength of this study is that it unifies understandings of scaffolding in SLL literature. It cross-compares three subjects and teachers in one classroom (see Mahan, Brevik and Ødegaard Citation2018). The design is systematic and detailed and uses a validated and reliable tool (PLATO) to measure scaffolding. However, the limitations of this study are that it provides insight into only one CLIL classroom and that it does not consider student perspectives. The next step in scaffolding research is to discuss how we can empirically measure how students perceive scaffolding strategies and how they become more independent learners. Teacher-centred approaches like PLATO do not fully cover these dimensions of scaffolding. Further research could delve into student-centred approaches and how students may experience scaffolding (Koole and Elbers Citation2014; Maybin, Mercer and Stierer Citation1992).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Teaching Learning Video Lab (TLVlab) at the University of Oslo. With the expertise of technician Bjørn Sverre Gulheim, I was able to collect data and use relevant tools for this article. I would also like to thank my advisors, Associate Professor Karianne Skovholt and Professor Tine Prøitz. I highly value your input on this article. Lastly, I would like to thank my dear friend Jennifer Luoto for her coding expertise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ajayi, Lasisi. 2014. Vocabulary instruction and Mexican–American bilingual students: how two high school teachers integrate multiple strategies to build word consciousness in English language arts classrooms. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 18, no. 4: 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2014.924475.

- Banse, Holland W., Natalia A. Palacios, Eileen G. Merritt, and Sara E. Rimm-Kaufman. 2017. Scaffolding English language learners’ mathematical talk in the context of calendar math. Journal of Educational Research 110, no. 2: 199–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1075187.

- Barr, Sheldon, Zohreh R. Eslami, and R. Malatesha Joshi. 2012. Core strategies to support English language learners. Educational Forum 76, no. 1: 105–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2011.628196.

- Bliss, Joan, Mike Askew, and Sheila Macrae. 1996. Effective teaching and learning: scaffolding revisited. Oxford Review of Education 22, no. 1: 37–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498960220103.

- Boche, Benjamin, and Megan Henning. 2015. Multimodal scaffolding in the secondary English classroom curriculum. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 58, no. 7: 579–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.406

- Bruton, Anthony. 2011. Is CLIL so beneficial, or just selective? Re-evaluating some of the research. System 39, no. 4: 523–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.08.002.

- Cohen, Julie. 2018. Practices that cross disciplines?: revisiting explicit instruction in elementary mathematics and English language arts. Teaching and Teacher Education 69: 324–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.10.021.

- Coyle, Do. 2007. Content and language integrated learning: towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10, no. 5: 543–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.2167/beb459.0

- Coyle, Do, Philip Hood, and David Marsh. 2010. Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cummins, Jim. 2013. BICS and CALP: empirical support, theoretical status, and policy implications of a controversial distinction. In Framing Languages and Literacies: Socially Situated Views and Perspectives, ed. Margaret Hawkins, 10–23. New York: Routledge.

- Cummins, Jim, and Margaret Early. 2015. Big Ideas for Expanding Minds: Teaching English Language Learners Across the Curriculum. Oakville, ON: Rubicon Publishing.

- Dalton-Puffer, Christiane. 2007. Discourse in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- De Graaff, Rick, Gerrit Koopman, Yulia Anikina, and Gerard Westhoff. 2007. An observation tool for effective L2 pedagogy in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10, no. 5: 603–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.2167/beb462.0.

- Dong, Yu Ren. 2017. Tapping into English language learners’ (ELLs’) prior knowledge in social studies instruction. The Social Studies 108, no. 4: 143–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2017.1342161.

- Echevarría, Jana, MaryEllen Vogt, and Deborah Short. 2017. Making Content Comprehensible for English Learners. The SIOP Model. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

- Farooq, M. 2007. Exploring the effects of spoken English classes of Japanese EFL learners. The Journal of Liberal Arts 2: 35–57.

- Gallagher, Fiona, and Gerry Colohan. 2017. T(w)o and fro: using the L1 as a language teaching tool in the CLIL classroom. The Language Learning Journal 45, no. 4: 485–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2014.947382.

- Gaskins, Irene W., Sharon Rauch, Eleanor Gensemer, Elizabeth Cunicelli, Colleen O’Hara, Linda Six, and Theresa Scott. 1997. Scaffolding the development of intelligence among children who are delayed in learning to read. In Scaffolding Student Learning, ed. Kathleen Hogan and Michael Pressley, 43–73. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books.

- Gibbons, Pauline. 2003. Mediating language learning: teacher interactions with ESL students in a content-based classroom. TESOL Quarterly 37, no. 2: 247–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.5054/tj.2010.215611. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3588504

- Gibbons, Pauline. 2015. Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning. Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. New Hampshire: Heinemann.

- Gritter, Kristine, Scott Beers, and Robert W. Knaus. 2013. Teacher scaffolding of academic language in an advanced placement U.S. history class. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 56, no. 5: 409–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.158.

- Grossman, Pamela. 2015. Protocol for Language Arts Teaching Observations (PLATO 5.0), Center to Support Excellence in Teaching (CSET). Palo Alto: Stanford University.

- Grossman, Pamela, Susanna Loeb, Julie Cohen, and James Wyckoff. 2013. Measure for measure: the relationship between measures of instructional practice in middle school English language arts and teachers’ value-added scores. American Journal of Education 119, no. 3: 445–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/669901.

- Hogan, Kathleen, and Michael Pressley. 1997. Scaffolding Student Learning. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books.

- Kayi-Aydar, Hayriye. 2013. Scaffolding language learning in an academic ESL classroom. ELT Journal 67, no. 3: 324–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct016.

- Kinginger, Celeste. 2002. Defining the zone of proximal development in US foreign language education. Applied Linguistics 23, no. 2: 240–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/23.2.240

- Klette, Kirsti, and Marte Blikstad-Balas. 2018. Observation manuals as lenses to classroom teaching: pitfalls and possibilities. European Educational Research Journal 17, no. 1: 129–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904117703228

- Klette, Kirsti, Marte Blikstad-Balas, and Astrid Roe. 2017. Linking instruction and student achievement. A research design for a new generation of classroom studies. Acta Didactica 11, no. 3: 1–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.5545

- Koole, Tom, and Ed Elbers. 2014. Responsiveness in teacher explanations: a conversation analytical perspective on scaffolding. Linguistics and Education 26: 57–69. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.02.001

- Lasagabaster, David, and Juan Manuel Sierra. 2009. Immersion and CLIL in English: more differences than similarities. ELT Journal 94, no. 4: 367–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccp082

- Lemke, Jay L. 1990. Talking Science: Language, Learning, and Values, Language and Educational Processes. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Li, Danli. 2012. Scaffolding adult learners of English in learning target form in a Hong Kong EFL university classroom. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 6, no. 2: 127–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.626858.

- Lin, Tzu-Chiang, Ying-Shao Hsu, Shu-Sheng Lin, Maio-Li Changlai, Kun-Yuan Yang, and Ting-Ling Lai. 2012. A review of empirical evidence on scaffolding for science education. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 10, no. 2: 437–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-011-9322-z.

- Long, M.H., and C.J. Sato. 1983. Classroom foreigner talk discourse: forms and functions of teachers’ questions. In Classroom Oriented Research in Second Language Acquisition, ed. H.W. Seliger and M.H. Long, 268–86. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Mahan, Karina R, Lisbeth M. Brevik, and Marianne Ødegaard. 2018. Characterizing CLIL teaching: new insights from a lower secondary classroom. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1472206

- Many, Joyce E., Deborah Dewberry, Donna Lester Taylor, and Kim Coady. 2009. Profiles of three preservice ESOL teachers’ development of instructional scaffolding. Reading Psychology 30, no. 2: 148–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710802275256.

- Masako, Douglas O., and Kataoka C. Hiroko. 2008. Scaffolding in content based instruction of Japanese. Japanese Language and Literature 42, no. 2: 337–59.

- Maybin, J., Neil Mercer, and B. Stierer. 1992. Scaffolding: learning in the classroom. In Thinking Voices. The Work of the National Oracy Project, ed. Kate Norman, 186–95. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- McNeil, Levi. 2011. Using talk to scaffold referential questions for English language learners. Teaching and Teacher Education 28, no. 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.005.

- Meyer, Oliver, and Do Coyle. 2017. Pluriliteracies teaching for learning: conceptualizing progression for deeper learning in literacies development. European Journal of Applied Linguistics 5, no. 2: 199–222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2017-0006

- Meyer, Oliver, Do Coyle, Ana Halbach, Kevin Schuck, and Teresa Ting. 2015. A pluriliteracies approach to content and language integrated learning – mapping learner progressions in knowledge construction and meaning-making. Language, Culture and Curriculum 28, no. 1: 41–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.1000924.

- Miller, Patricia H. 2005. Commentary on scaffolding: constructing and deconstructing development. New Ideas in Psychology 23, no. 3: 207–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2006.07.001.

- Mortimer, Eduardo. 2003. Meaning Making in Secondary Science Classrooms. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Morton, Tom. 2015. Vocabulary explanations in CLIL classrooms: a conversation analysis perspective. Language Learning Journal 43, no. 3: 256–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2015.1053283.

- NESH. 2006. Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences, Law and the Humanities. National Committees for Research Ethics in Norway.

- Nikula, Tarja, Emma Dafouz, Pat Moore, and Ute Smit. 2016. Conceptualising Integration in CLIL and Multilingual Education. Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

- Nikula, Tarja, and Karita Mård-Miettinen. 2014. Language learning in Immersion and CLIL classrooms. In Handbook of Pragmatics, ed. Jan-Ola Östman and Jef Verschueren, vol. 18, 1–26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Pawan, Faridah. 2008. Content-area teachers and scaffolded instruction for English language learners. Teaching and Teacher Education 24, no. 6: 1450–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.02.003.

- Pérez-Cañado, María Luisa. 2016. Are teachers ready for CLIL? Evidence from a European study. European Journal of Teacher Education 39, no. 2: 202–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1138104.

- Ruiz de Zarobe, Yolanda, and Jasone Cenoz. 2015. Way forward in the twenty-first century in content-based instruction: moving towards integration. Language, Culture and Curriculum 28, no. 1: 90–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.1000927.

- Ruiz de Zarobe, Yolanda, and Victoria Zenotz. 2015. Reading strategies and CLIL: the effect of training in formal instruction. The Language Learning Journal 43, no. 3: 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2015.1053284.

- Ruiz de Zarobe, Yolanda, and Victorria Zenotz. 2017. Learning strategies in CLIL classrooms: how does strategy instruction affect reading competence over time? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21, no. 3: 319–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1391745

- Silliman, E., and L.C. Wilkinson. 1994. Discourse scaffolds for classroom intervention. In Language Learning Disabilities in School-Age Children and Adolescents, ed. G. Wallach and K. Butler. New York: Perason Higher Education.

- Smagorinsky, Peter. 2018. Deconflating the ZPD and instructional scaffolding: retranslating and reconceiving the zone of proximal development as the zone of next development. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 16: 70–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.10.009.

- Snell, Julia. 2011. Interrogating video data: systematic quantitative analysis versus micro-ethnographic analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 14, no. 3: 253–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.563624

- Svenhard, Britt Wenche, Kim Servant, Glenn Ole Hellekjær, and Henrik Bøhn. 2007. Norway. In Windows on CLIL, ed. Anne Maljers, David Marsh, and Dieter Wolff, 139–46. The Hague: European Platform for Dutch Education.

- Sætre, Per Jarle. 2013. The beginning of geography didactics in Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography 67, no. 3: 120–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2013.796568.

- Tomlinson, Carol Ann, and Tonya R. Moon. 2013. Differentiation and classroom assessment. In SAGE Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. James H. McMillan, 415–30. London: Sage.

- Torrez, Cheryl A., and Elizabeth Ann Claunch-Lebsack. 2013. Research on assessment in the social studies classroom. In SAGE Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. James H. McMillan, 461–72. London: Sage.

- van de Pol, Janneke, and E. Elbers. 2013. Scaffolding student learning: a micro-analysis of teacher-student interaction. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 2, no. 1: 32–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.12.001.

- van de Pol, Janneke, Monique Volman, and Jos Beishuizen. 2010. Scaffolding in teacher-student interaction: a decade of research. Educational Psychology Review 22, no. 3: 271–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9127-6.

- van Lier, Leo. 2004. The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning. A Sociocultural Perspective. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic.

- Verenikina, Irina. 2004. From theory to practice: what does the metaphor of scaffolding mean to educators today? Outlines: Critical Practice Studies 6, no. 2: 5–16.

- Walqui, Aida. 2006. Scaffolding instruction for English language learners: a conceptual framework. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 9, no. 2: 159–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050608668639

- Wood, David, Jerome S. Bruner, and Gail Ross. 1976. The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17, no. 2: 89–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.