ABSTRACT

It is natural to assume the languages classroom to be a key site for the construction of learners’ linguistic and multilingual identities. Yet, an underlying assumption exists that this will occur regardless of whether teachers explicitly raise learners’ awareness about the nature of language and how language is implicated in their lived experience. We argue, therefore, that a new dimension of languages pedagogy is necessary in order for learners to understand their own and others’ linguistic repertoires (whether learned in school, at home or in the community) and so to recognise their agency in being able to claim a multilingual identity. In this paper, we present a rationale for and explore the effect of an innovative programme of participative multilingual identity education which was implemented by teachers in languages classrooms across four secondary schools in England over the course of one academic year. Data were collected through questionnaires administered before and after the intervention and sought to trace the formation of students’ multilingual identity. Evidence from this study suggests that while more traditional interventions focusing on raising awareness about the benefits of languages can be beneficial, effects can be enhanced by an additional ‘identity’ element, i.e. actively promoting reflexivity.

Introduction

Language learning is a vital part of school curricula. It not only provides opportunities for individual students to develop communication skills and broaden their mental horizons, but can also enhance national social cohesion and enable future participation on the global stage (British Academy Citation2019). Yet, in England less than half the student population study a foreign language beyond the compulsory phase. In communities viewed as traditionally ‘monolingual’ some may struggle to see the personal relevance of language learning, both now and in the future. Similarly, students in more multilingual communities may lack awareness of the ways in which the various languages within their repertoire relate to them personally. It is also important to note that the current national curriculum for languages in England predominantly centres on developing skills in the particular target language (e.g. in grammar, vocabulary and linguistic competence) and fails to acknowledge the potential for drawing on and developing students’ wider multilingual repertoires (Department for Education Citation2014). In this paper, we, therefore argue that a new dimension of pedagogy for the languages classroom is necessary in order to help learners understand their own and others’ linguistic repertoires (whether learned in school, at home, or in the community) and so to recognise their agency in being able to claim a multilingual identity, by which we mean individuals’ explicit understandings of themselves as users of more than one language. We hope that this can, in turn, positively influence students’ uptake of and investment in language learning.

In this paper, we draw on data gathered as part of a large-scale, longitudinal, mixed-methods study which aimed to investigate the link between multilingualism, and the extent to which one identifies as multilingual, and learning in school. We focus here particularly on the development and effects of an innovative intervention of participative multilingual identity education which was implemented by teachers in languages classrooms across four secondary schools in England over the course of one academic year. We begin by providing an overview of our conceptualisation and operationalisation of multilingual identity and consider the potential for identity-based interventions in schools. We then provide an overview of the development of the intervention itself and the questionnaire used to collect data. The findings presented and discussed focus on the extent to which this pedagogical intervention in the languages classroom supported the development of students’ multilingual identity.

Background

Multilingual identity

Research in identity, which can be broadly defined as ‘how a person understands his or her relationship to the world, how that relationship is structured across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future’ (Norton Citation2013: 45), has flourished in recent years across a wide range of disciplines. It has been researched in relation to constructs such as ethnicity, class, gender, culture, and political and religious affiliations, amongst others. However, within the fields of applied linguistics and languages education, analytic primacy is given to language as an integral part of identity; after all, it is through language that we think, define ourselves, and represent ourselves to others.

Yet, the sheer diversity of research traditions within the field has led to a plethora of diverse (and often competing) theoretical lenses through which to explore this relationship. Dominant frameworks to date include psychosocial perspectives which consider identity to be developed rather than constructed (e.g. Erikson Citation1968); sociocultural perspectives where identity is seen as relational, mediated and shifted i.e. it is socially-constructed rather than developed (e.g. Vygotsky Citation1978), and; poststructuralist perspectives which view identity as dynamic, multiple and shifting (e.g. Norton Citation2013). While there are undoubtedly differences between these various perspectives, there are also areas of intersection and it is precisely at this nexus where we situate the current study by adopting a multi-theoretical perspective. As such, we consider identity as both individual and social, and as a process with the potential for self-transformation (see Fisher et al. Citation2020 for a full account of the theoretical background of this study).

As noted above, we focus here particularly on the relationship between languages and identity. While the term ‘linguistic identity’ has commonly been used to refer to the way one identifies in each of the languages in one’s repertoire, we instead use ‘multilingual identity’ as a more inclusive ‘umbrella’ term which encompasses individuals’ explicit understandings of themselves as users of more than one language (Fisher et al. Citation2020; Henry Citation2017). We use the term ‘multilingual’ here in its widest sense to include not only proficient bi/multilinguals, but also ‘monolingual’ speakers who are beginning to learn a foreign language in school (and who, consequently, may have relatively low levels of proficiency in this language), dialects and varieties of language and non-verbal forms of communication such as sign languages.

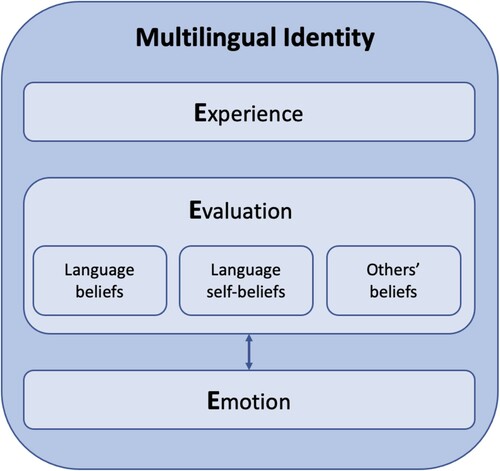

We further operationalise multilingual identity as being shaped by learners’ experiences of languages and language learning, their evaluations of languages and of themselves as language learners (and, by extension, others’ evaluations of languages) and, by their emotions relating to language learning. This ‘3Es model’ (see ) is grounded in data collected from over 2,000 students as part of the wider study on which this paper is based. Analysis conducted using structural equation modelling revealed these ‘3Es’ as the key dimensions underpinning multilingual identity. While we present a simplified form of this here, full explication of this model is the focus of a paper currently in preparation by the research team.

By experience, the first ‘E’, we refer here to a learner’s exposure to and interaction with languages across their lifespan. This could include languages encountered in a range of different contexts such as in the home, at school, in the wider community, on holiday, or through books or other forms of media. In line with Aronin’s (Citation2016) definition of the related construct of ‘multilinguality’, we similarly argue that a person’s multilingual identity is shaped by their family history, social activities and personal life scenarios. This, in turn, aligns with the emphasis on the role of historical, contextual and social factors which are prioritised in sociocultural and poststructural perspectives on identity (e.g. Norton and Toohey Citation2011). While we fully acknowledge the importance of such experiences in constructing one’s multilingual identity, the emphasis of this paper, however, is predominantly on the remaining two ‘Es’ (evaluation and emotion) as these are the factors most likely to undergo change through the process of a classroom-based intervention. Yet, we do not preclude the possibility that the intervention itself could indeed be classed as a transformational ‘experience’.

The next ‘E’ focuses primarily on students’ evaluations of languages and of themselves as language learners. This broadly relates to what Vignoles et al. (Citation2011) refer to as individual or personal identity which encompasses a person’s beliefs, attitudes, values, self-efficacy, self-esteem and goals. Indeed, beliefs in particular have long been recognised as being highly influential in the language learning process. They have the potential to exert a powerful influence on students’ learning (Fisher Citation2013) and are intrinsically related to other evaluative self-concepts and to emotions (Barcelos and Kalaja Citation2011). However, a relational aspect is also key here and we focus not only on learners’ evaluations of languages, but also on their evaluations of others’ beliefs about languages. As suggested by Taylor (Citation2013: 13), ‘it is both intuitive and supported by a substantive body of literature that the main relational contexts shaping adolescents’ identity are their family, their friends, their classmates and their teachers’. If those around a learner are seen to value languages, for example, this may in turn influence their own evaluations.

The third ‘E’ is similarly crucial in light of the widely accepted view that ‘identity formation and emotion are inextricably linked’ (Zembylas Citation2003: 223) and is closely related to evaluation. Emotions, in addition, are an important factor in language learning. Aronin and Laoire (Citation2003: 22), for example, speak of the ‘emotional changes accompanying the process of acquiring a new language while moving from a mono- or bilingual state to a multilingual one’ and Dewaele (Citation2011) similarly highlights the emotional dimension of the language learning process and, crucially for this paper, the role that the teacher can play in shaping these emotions in the classroom. Yet, in spite of the existing acknowledgement in the literature of the importance of emotions in identity more broadly and in the process of language learning in particular, Henry (Citation2017: 549) highlights that the emotions attached to ‘self-identifications as being multilingual’ (our emphasis) have received little research attention. Our focus on the emotional aspects of multilingual identity therefore constitutes a timely response to this call.

Having considered briefly how we both theorise and operationalise the construct of multilingual identity in this study, we now turn to the importance of issues related to identity and, by extension, the role of identity-based interventions, in the classroom context.

Identity-based interventions

There is a well-established body of literature which suggests a strong link between education and identity. Wenger (Citation1998), for example, conceptualises learning as an aspect of identity and identity as a result of learning. Here, learning is considered as ‘not just an accumulation of skills and information, but a process of becoming’ (215). Lestinen et al. (Citation2004: 6) similarly consider that a basic goal of education ‘is to contribute to the construction of an individual’s identity’ which is achieved by recognising social and cultural identity as an integral part of the educational process. Such a connection also emerged in data collected by Nasir and Cooks (Citation2009) in the US context and Lamb (Citation2011) in the UK context. Yet, while there is much evidence to suggest that the process of going through schooling can influence a student’s identity, too often there is an underlying assumption that this will occur tacitly, without the teacher drawing explicit attention to such processes.

While the potential for school-based curricula interventions to promote identity formation has long been recognised (e.g. Waterman Citation1989), there has been surprisingly little research investigating ‘the role of school and of teachers as agents in their students’ identity formation’ (Kaplan et al. Citation2014: 249). Indeed, it is only in more recent years that this has been investigated empirically in the form of explicit identity-based education, defined by Schachter and Rich (Citation2011: 222) as ‘the purposeful involvement of educators with students’ identity-related processes or contents’. Such identity exploration can be promoted through activities which encourage both reflection and reflexivity in the classroom. As suggested by Kaplan et al. (Citation2014), self-relevance is a key part of identity exploration within the curriculum; this entails both establishing an explicit connection between a certain aspect of the curriculum (i.e. knowledge) and an aspect of the self (i.e. identity), and encouraging learners to question and examine those self-aspects. This is a multifaceted process and, as cautioned by Sinai et al. (Citation2012: 196), ‘identity exploration is not a single behaviour. It may involve different cognitive, emotional, and behavioural actions’.

To date, there are only a small number of empirical studies which have explored the influence of identity-related interventions in the classroom. One group of such studies has focused on developing more general learner characteristics. Sorenson et al. (Citation2018), for example, examined the effects of an identity-based motivation intervention (see Oyserman Citation2014) on 380 high school students in Chicago. The students took part in small-group activities for 30–45 min twice weekly for the first six weeks of the school year. Grounded in social psychological theory, these activities focused on helping students to set goals, develop possible identities and overcome difficulties. Findings indicated positive academic outcomes for the intervention group students. Another study by Perez et al. (Citation2020) focused on piloting an identity-based intervention to develop college students’ educational commitment, values and persistence. The intervention was conducted in a study skills course and used identity-focused prompts within journal assignments to promote reflection and to encourage learners to explicitly connect course content to their current and future identity. An example of a prompt used was: ‘how do your academic goals relate to how you see yourself now?’. Analysis revealed positive outcomes for the intervention group students with regard to their task value and commitment; however, no differences emerged between groups in relation to future course registration.

Another group of studies are more subject-specific. Chapman and Feldman (Citation2017), for example, examined how participation in an authentic science experience helped to develop high school students’ science identity. It is important to note that the construct of ‘science identity’ was used here more as an analytical tool rather than as a foundation for the intervention itself, nonetheless, useful insights are provided. The researchers noted that learners’ science identity developed from being able to do science (performance), to knowing science content and practices (competence) to being recognised by themselves and others as a scientist (recognition). Identity-based interventions have also proven successful in mathematics contexts (Heffernan et al. Citation2020) and in a developmental writing course (D’Antonio Citation2020). Yet, little is known about the potential for similar identity-focused interventions in the language learning classroom.

The need for an identity-oriented pedagogy in the languages classroom

While there have been a number of intervention studies designed to improve motivation and mindsets in foreign language lessons (e.g. Lanvers Citation2020), to the best of our knowledge there are currently no studies in this context which specifically take an identity-based approach. In line with Kramsch (Citation2009), we argue that foreign language classrooms are key sites for the construction of multilingual identities and that, in turn, the development of such identities may positively influence learners’ investment in (and potentially also their attainment in) language learning. In addition, we consider this to be particularly pertinent for adolescent, secondary school learners who are at a crucial stage of their identity construction (Taylor Citation2013).

We similarly argue that for this to be effective, any intervention must be explicit and participative, that is, learners need to engage in the active and conscious process of considering their linguistic and multilingual identities and to become aware of the possibility of change in relation to these identifications (Fisher et al. Citation2020). We therefore hypothesised that developing a classroom-based intervention which focuses on developing students’ knowledge, awareness and reflexivity about languages could have positive effects on the development of their multilingual identity. This led to the following research question which is the focus of the current paper: To what extent can a pedagogical intervention in a languages classroom support the development of multilingual identities?

Research design

Context and participants

As noted above, the data presented in this paper are taken from a much larger project involving over 2,000 students in seven state-funded secondary schools across the East of England and London. This included collection of student demographic and attainment data from schools, as well as student self-report data from questionnaires, interviews and drawing tasks in order to explore what multilingual identity is, how this can be developed, and how this relates more broadly to attainment in school. In this paper, we focus on the intervention dimension which involved 268 Year 9 (age 13–14) students and their languages teachers in four of these schools. The schools were chosen to represent a range of geographical locations (urban/rural) and student demographics (e.g. first language background and socioeconomic status) (see ). The students were in their third year of secondary school which is the final year of compulsory foreign language education in England. As such, they not only represented a broad range of attainment levels and attitudes towards languages, but they were also a crucial group to target as they were making decisions about which subjects to continue (or not) the following year. Three parallel Year 9 classes were selected in each of the four schools and were designated as either the full intervention group, the partial intervention group or the control group (as explained below). provides an overview of the number of participating students in each group. For the purpose of analysis for the current paper, the number includes only those students who completed both the pre- and the post-intervention questionnaires.

Table 1. Overview of participating schools and number of students per group.

Quasi-experimental research design and intervention

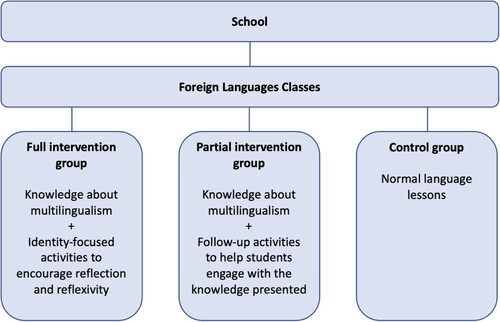

As noted above, the focus of this paper is on the influence of a pedagogical intervention on the development of students’ multilingual identity. As such, a quasi-experimental design was adopted based on the framework for generating a participative approach to multilingual identity formation proposed by Fisher et al. (Citation2020). This suggests there are three key elements in developing an identity-oriented pedagogy for the languages classroom: (a) cultivating students’ knowledge about multilingualism (i.e. the cognitive and social benefits); (b) raising their awareness of the potential for these issues to interact with identity and; (c) encouraging reflexivity and personal reflection. These elements align closely with the ‘3Es’ model outlined above and, in particular, target students’ evaluations and emotions relating to languages and language learning. We therefore devised a quasi-experimental design involving three classes in each school, as shown in .

The control groups continued with their normal language lessons, while the intervention groups were exposed to six one-hour intervention lessons over the course of one academic year (approximately two lessons per term). These took place during their normal timetabled language lessons (equivalent versions were created in each of French, German and Spanish to accommodate differing language provision in the schools) and were taught by their normal class teachers who collaborated with the research team in developing the materials. The lessons firstly focused on developing students’ knowledge in a range of topics including languages in various contexts (e.g. the classroom, school, community), links between culture and language, and sociolinguistic knowledge such as the use of dialects. While some elements of the lessons involved some discussion in English, each also included input (text, audio and/or video) and various tasks in the relevant target language so as to complement (and not detract from) students’ language learning.

While the ‘knowledge’ elements of the lessons outlined above remained broadly the same for the full and the partial intervention group students, the nature of the subsequent activities varied. The partial intervention group students completed follow-up activities which encouraged them to engage with the knowledge presented, whereas the full intervention group students were explicitly encouraged to be reflective and reflexive and to consider how the knowledge presented related to themselves as users and learners of multiple languages. The rationale for the two intervention groups was to explore whether the knowledge element alone was sufficient, or whether incorporating an identity-focused pedagogy was more effective. An outline of the lesson objectives and example activities can be found in Appendix 1 and an extended set of resources for languages teachers developed from this study is freely available to download at www.wamcam.org.

Method of data collection: questionnaire

Researching identity and, by extension, multilingual identity is inherently complex, and researchers have adopted a wide range of methods and approaches. While some use questionnaires (e.g. Haukås, Storto and Tiurikova, Citationthis volume) or semi-structured interviews (e.g. Ceginskas Citation2010), others rely more heavily on drawings or visual narratives (e.g. Dressler Citation2015; Melo-Pfeifer Citation2015). In the wider study from which this paper is drawn, the research team used a combination of these methods and also collected demographic and attainment data from schools. However, given that the focus of this paper is on quantifiable change arising from the quasi-experiment, we draw here only on data collected from the pre- and post-intervention questionnaires which incorporated a range of question types in order to access data on key dimensions of multilingual identity. As noted above, the construct of multilingual identity is conceptualised here as being influenced by students’ experiences of languages (i.e. their exposure to and use of languages both in and out of the home), both their own and others’ evaluations of languages and their emotions towards languages and language learning. While the questionnaire addressed each of these dimensions, this paper will focus on data related to the latter two ‘Es’ (i.e. evaluation and emotions) as these are the dimensions most likely to be directly influenced by the classroom-based intervention (which, as suggested above, could itself be considered as a transformational experience).

Evaluation: We drew on two key question types to collect data relating to evaluation: the multilingual visual analogue scale (mVAS) and Likert-scale responses to a series of statements about languages and language learning. The mVAS consisted of a 100 mm straight line with the labels of ‘monolingual’ and ‘multilingual’ at each end and aimed to provide an insight into how participants identify themselves in relation to these terms. Students were asked to put a cross on the line to indicate where they would position themselves and to provide a reason. Visual analogue scales have proven useful for measuring attitudes or characteristics which are believed to exist on a continuum and are therefore particularly useful when researching a phenomenon as complex and multifaceted as identity (see Rutgers et al. Citationunder review, for more information). Students were also asked to respond to a series of statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (see Appendix 2). The statements related to three key constructs:

Language beliefs: These statements focused on students’ own views of languages more broadly, for example, whether they felt they were useful or important.

Language self-beliefs: These statements focused on students’ views of themselves in relation to languages and language learning and incorporated items related to self-efficacy, for example, whether they felt they had a talent for learning languages.

Others’ beliefs about languages: Given that the views of students may be influenced by those around them, participants were also asked to indicate their perception of their parents’ and their friends’ beliefs about languages.

Emotion: Given the complexity of researching emotions, we gathered data on this through three question types. The first asked students to respond to the following statement on the same 5-point Likert-scale as above: ‘I like learning other languages’. The aim here was to capture a sense of students’ enjoyment of languages and language learning. Next, we sought to explore students’ sense of pride in relation to each of the languages in their repertoire. As stated by Van Osch et al. (Citation2018: 404), ‘pride is an interesting emotion because it simultaneously focuses on the self and on others’ and is therefore highly relevant to our focus on identity. Students were first invited to list any languages they knew (including those spoken at home, learned in school or which they were exposed to in any other way). For each language listed, they were asked to indicate (by ticking a box) whether they were proud to be able to speak this language. An overall ‘pride score’ was then calculated by dividing the number of languages they were proud of speaking by the total number of languages identified. Finally, data on emotions were elicited through an open-ended metaphor elicitation task and two sentence completion tasks. The use of metaphors has proven promising in accessing learners’ emotions and beliefs (Barcelos and Kalaja Citation2011; Fisher Citation2017) as an indirect means of encouraging participants to ‘articulate beliefs that they might previously have been unaware of’ (Fisher Citation2013: 376). Students were therefore asked to complete the following statement: ‘Learning a foreign language is like … because … ’. To complement this, students were asked more directly about their feelings through completing the following sentences: ‘When I speak in a foreign language I feel like … because … ’; and ‘When I’m in the foreign language classroom I feel like … because … ’. While this data will be analysed qualitatively elsewhere, for the purpose of this paper each statement was coded as either positive, negative or neutral (examples are provided below).

The data were entered into SPSS and were analysed using a series of non-parametric Wilcoxon signed ranks tests to explore change within each group over time. Non-parametric tests were selected due to the non-normal distribution of the data as indicated by Shapiro–Wilk tests. Given restrictions of space and the overall aim of this paper to explore the potential for identity-based interventions in the languages classroom more broadly, we consider here the data across all four schools. We acknowledge that the school environment itself will influence the implementation and outcomes of any intervention; however, to fully explore this requires a case study approach which draws on a wider range of data sources.

Ethical considerations

This study gained institutional ethical approval and was also conducted in line with guidance from the British Educational Research Association (Citation2018). However, in addition to following appropriate procedures in terms of gaining informed consent from school leaders, teachers, parents and students, there were also particular ethical considerations to be taken into account given the focus of the study in shifting students’ identity. An identity-focused intervention in itself may be viewed as ‘an overstepping of the teacher’s legitimate social role’ or, at the extreme, as ‘an educational stance with sinister Orwellian connotations’ (Schachter and Rich Citation2011: 234). In order to combat any such negative effects or perceptions, we worked closely with classroom teachers to develop the activities and they took particular care to adopt a dialogic approach to the intervention lessons so as not to impose their own particular versions of (multilingual) identity on students. As cautioned by Waterman (Citation1989: 399), we did not seek to ‘undermine existing identity commitments’, but rather to encourage students to reflect on these.

Results

Evaluation

This section will present results relating to students’ evaluation of languages according to their responses to the multilingual scale (mVAS) and their responses to a series of Likert-scale statements relating to their language beliefs, self-beliefs and beliefs of others.

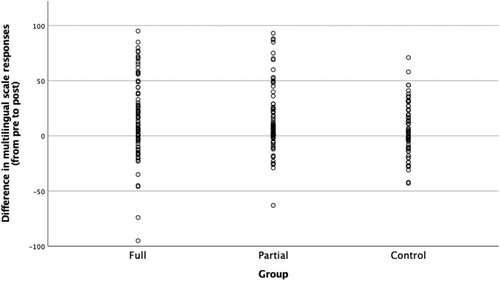

(a) Identification as multilingual

As noted above, the mVAS was used as a general indicator of the strength of students’ overall self-evaluation of themselves as multilingual (or not). A mean score for each group was initially calculated based on where students placed their cross on the line in both the pre- and post-intervention questionnaires (as measured in millimetres), with scores closer to 0 indicating an evaluation as more ‘monolingual’ and those closer to 100 as more ‘multilingual’. As shown in , the mean score of the full intervention group students increased by over 11 following the intervention, with a very small positive change for the partial intervention group and minimal change for the control group.

Table 2. Pre- and post-intervention results for the mVAS.

A Wilcoxon signed ranks test revealed that the increase among the full intervention group students was significant, while the differences were not significant among the partial group or the control group. To further explore this, a scatter plot was created to visualise the change in the mVAS scores from pre- to post-intervention for each student (see ). This provides further evidence that the full intervention group students experienced a greater shift towards multilingual identification than the other two groups. However, it is also worth noting that the spread is also broader compared with the partial and control group students and that a small number of outliers in the full intervention group experienced a substantial negative shift. While this was certainly not the intended outcome of the intervention and does not reflect the majority of students in the group, it perhaps illustrates the power of the identity-related elements of the intervention to encourage students to engage with these issues one way or another.

(b) Language beliefs and self-beliefs

This section draws on data from the Likert-scale responses about students’ language beliefs (i.e. their beliefs about languages and the value of language learning) and their language self-beliefs (i.e. their beliefs about themselves as language learners) as detailed in Appendix 2. A composite mean score for ‘language beliefs’ and ‘language self-beliefs’ was calculated for each student based on their responses to the corresponding statements and a series of Wilcoxon signed ranks tests were conducted as shown in . The pattern of results for both of these evaluative constructs was largely similar; while all groups showed some increase in their mean scores after the intervention, this was greater for both the full and the partial groups. A series of Wilcoxon signed rank tests confirmed that this increase was significant for both groups in relation to their language beliefs and language self-beliefs. While effect sizes are small, these results are nonetheless encouraging.

Table 3. Pre- and post-intervention results for language beliefs and self-beliefs.

However, while it is certainly encouraging to note the significant increases over time within both the full and partial groups, it is important to acknowledge that the differences between these two groups are small and non-significant. Yet, even these small differences are of interest. On the one hand, the partial group students demonstrated a slightly greater increase than the full group students with regard to their language beliefs. We could hypothesise here that the ‘knowledge’ component of the intervention and the subsequent activities undertaken by the partial group to engage with that knowledge may have been sufficient to shift students’ beliefs about languages. Yet, ratings for language self-beliefs improved slightly more for the full intervention group students which might suggest that the identity-focused activities played a facilitating role in shaping self-beliefs.

(c) Others’ beliefs about languages

Students were also asked about their perceptions of others’ beliefs about languages and responded to separate sets of Likert-scale statements relating to their parents and their friends. An overall mean score was calculated for each and a series of Wilcoxon signed ranks tests were conducted as shown in . Of particular note here is that only the partial intervention group experienced a significant shift in responses from the pre- to the post-intervention questionnaires. We hypothesise that this may be the result of the focus of the intervention on knowledge about languages. It could be that the partial intervention group students went home and passed some of this knowledge onto their parents or discussed it with their friends and therefore perceived more positive views about languages among these groups over time. Yet, the full intervention group students also received a similar input of knowledge and a comparable trend would have been expected here.

Table 4. Pre- and post-intervention results for others’ beliefs about languages.

In order to investigate this further, correlations between the change in students’ mVAS scores (as an indicator of their willingness to identify as multilingual) and the change in responses to statements about parents’ and friends’ beliefs were explored. Pearson correlations revealed a significant positive relationship between these two variables for the full group students in relation to the beliefs of both parents (r = .245, p = .036*) and friends (r = .273, p = .018*). Among the partial group this correlation was very weak and non-significant for both parents (r = .069, p = .586) and friends (r = .033, p = .794), and among the control group students this correlation was actually negative (but non-significant) in relation to parents (r = −.134, p = .316) and significantly negative in relation to friends (r = −.329, p = .012*).

This indicates that those students in the full intervention group who reported the greatest increase in their evaluation of their own multilingual identity were also those who reported the greatest improvement in relation to the beliefs of others, a link which was not evident amongst the other groups. One possible explanation for this, is that by developing their own multilingual identity, students also became more aware of others’ beliefs, or perhaps even more likely to talk to their parents and friends about languages outside of the classroom. While we originally included these items on the questionnaire as we believed that individual students may be influenced by the beliefs of those around them, perhaps this also suggests that students who develop a multilingual identity within the classroom may, in turn, influence others’ beliefs about languages. This represents an interesting avenue for further investigation.

In summary, the findings presented so far suggest that both the partial and full interventions positively influenced students’ evaluation of languages in comparison to the control group. This suggests that being provided with knowledge about languages and language learning may increase the extent to which students value languages as well as their own ability to do well (which may then also extend to influencing the views of those around them). However, we note that it was only the full intervention group students who were significantly more likely to identify themselves as multilingual on the mVAS following the intervention, which would confirm the importance of the element of reflexivity.

Emotion

While we acknowledge that emotions are inevitably linked to (self) beliefs, the results presented in this section explore those aspects of the questionnaire which sought to elicit students’ emotions towards languages and language learning more directly.

(a) Enjoyment

In order to capture a sense of students’ enjoyment of languages and language learning, the students were asked to respond to the following statement on the same 5-point Likert scale as the evaluation statements above: ‘I like learning other languages’. Mean scores for each group were calculated and a series of Wilcoxon signed ranks tests were conducted to explore changes over time as shown in . This reveals a significant increase in scores for the full intervention group students only. While it is important to acknowledge that there are a range of other factors which will similarly affect students’ enjoyment of a subject, such as their classmates or teacher, this finding could suggest that the identity-focused dimension had a greater effect on students’ enjoyment of languages and language learning than the knowledge element alone.

Table 5. Pre- and post-intervention results for enjoyment.

(b) Pride

In order to explore students’ feelings of pride in relation to each of their languages, they were first asked to identify any languages they know (regardless of how they were/are learned) and were then asked to indicate by ticking a box whether they were proud to know this language. While we provided ‘English’ as a starting point, any additional languages were listed by students in an open-ended way. The main languages identified by students were those learned in school such as French or German (either at the time of completing the questionnaire or previously) or home languages other than English, such as Polish or Urdu. However, some students also chose to identify languages which they were exposed to in other ways, for example, Greek because they travelled to Greece regularly on holiday, or Japanese because they watched a lot of anime. Given that the number of languages identified ranged between one (i.e. only English) and eight we calculated an overall ‘pride score’ for each student by dividing the number of languages they were proud of speaking by the total number of languages identified. However, before doing so we removed ‘English’ in order to increase the reliability of the results. For example, if a student only listed English but was proud to speak it, they would have received a ‘pride score’ of 1.0 which may have skewed the results. Findings are shown in and indicate a significant positive increase in the pride score among the full intervention group only with minimal changes among both the partial and control groups. As was the case with enjoyment, we might explain this result by suggesting that the identity dimension of the intervention had the greatest impact on students’ sense of pride.

Table 6. Pre- and post-intervention results for pride.

(c) Metaphor elicitation and sentence completion

One metaphor elicitation and two sentence completion items were included on the questionnaires as an indirect means of eliciting students’ feelings towards languages and language learning. For the purpose of this paper, they were broadly coded as either negative (1), neutral (2) or positive (3) to explore possible changes as a result of the intervention. Examples are provided in .

Table 7. Examples of metaphors and sentence completion tasks.

The statements were firstly considered descriptively and shows the percentage of negative, neutral and positive responses for each group both before and after the intervention. What is immediately apparent when considering the change in percentage points over time is that there was a decrease in neutral positions across all groups and all three elicitation statements. This broadly led to a corresponding increase in both negative and positive responses. However, positive changes are more evident among the full intervention group students who demonstrated an increase in positive responses of 14.8%, 35.1% and 35.9% in each of the three statements respectively as against a corresponding change of −2.7%, +14.9% and 14.2% in the partial group.

Table 8. Percentage of responses for metaphors and sentence completion statements.

To explore this further, the coding of the responses as negative (1), neutral (2) or positive (3) were then treated as ordinal data and analysed using a series of Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. This revealed that the positive shift evident in for the full intervention group students was significant for both metaphor 1 (Z = −2.500, p = 0.012*, r = −0.31) and statement 3 (Z = −3.363, p = 0.001*, r = −0.42). None of the changes among either the partial or control groups emerged as significant. While we acknowledge that there are limitations in analysing the qualitative data from the metaphor elicitation task in this way, it nonetheless provides some further evidence to support the conclusion that the identity-focused elements of the full intervention may have contributed to students’ emotions towards languages and language learning.

While both the partial and the full versions of the intervention seemed to influence aspects of students’ evaluation of languages as shown above, it seems that only the full intervention, with its greater focus on identity-related elements, had a particular impact on students’ emotions towards languages and language learning. This is evident in the significant positive shift revealed for the full intervention group students only and may also explain why this was the only group which experienced a significant increase in the mVAS scores, as shown above.

Discussion and conclusion

Our data revealed that both the partial and full versions of the intervention positively influenced students’ evaluation of languages in comparison to the control group. This suggests that being provided with information about the benefits of language learning may increase the extent to which students value languages as well as their own ability to do well in languages (which may also extend to influencing the views of those around them). This is broadly in line with findings from other intervention studies which aimed to increase engagement with foreign language learning. In the UK context, for example, Lanvers (Citation2020) found that an intervention which focused on a range of metalinguistic issues, such as the cognitive benefits of language learning and world languages, improved students’ beliefs about language learning. However, while Lanvers (Citation2020) found little effect on self-efficacy, we found some improvement in relation to self-beliefs.

What emerged as particularly notable in our own study was the greater impact of the full intervention on students’ emotions relating to languages. These findings could indicate a seemingly symbiotic relationship between emotions and identity; the full intervention (distinguished by its identity-focused activities) influenced students’ emotions towards languages and language learning which, in turn, may have contributed to their increased willingness to identify as multilingual as indicated in the mVAS results. While these findings, which suggest the possible influence of an identity-focused pedagogy in the languages classroom, are largely in line with results from identity-based intervention studies conducted in other subject areas (e.g. D’Antonio Citation2020; Heffernan et al. Citation2020), our data provide more nuanced insights into the potential of such interventions to influence both students’ (self) evaluations and emotions in the foreign languages classroom.

However, given that we relied on predominantly quantitative data for the purpose of this paper, there is a need to look beyond the numbers and to consider whether findings reported as statistically significant ‘are also theoretically or pedagogically meaningful or important’ (Nassaji Citation2020: 742). At a theoretical level, this study not only points to the potential positive effects of identity-based interventions in schools, but the particular increase in results among the intervention group students indicates the importance of a tripartite framework to underpin such pedagogic intervention, combining knowledge, awareness and reflexivity. The results also enhance our understanding of how such an identity-focused pedagogy influences the various dimensions of multilingual identity, in particular, evaluation and emotions. However, while the focus of the quantitative data in this paper has revealed interesting trends at the level of the whole group, the next step will be to draw on the qualitative data from the wider study in order to explore some of the potential reasons behind these trends. For example, we noted small differences in the way in which the full and partial interventions may have influenced students’ language beliefs and self-beliefs and, additionally, our data pointed towards possible links between a student’s multilingual identity and others’ beliefs. The qualitative data may help us to further explore and explain the relationship between an identity-focused pedagogy and these evaluative constructs.

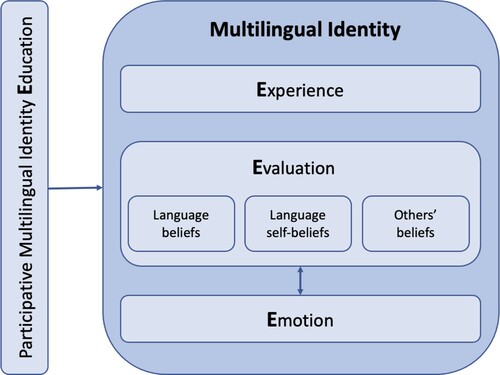

At a pedagogical level, this study, and indeed the resulting intervention resources, have important implications for enhancing language learning in schools. Evidence suggests that while more traditional interventions focusing on raising awareness about the benefits of languages can be valuable, effects may be enhanced by an additional ‘identity’ element, i.e. actively promoting reflexivity, that is, ‘what this intervention means for me personally’. This was most evident in the increase in positive emotions among the full intervention group students which seemed, at least in part, to be associated with an increased sense of multilingual identity. By developing their multilingual identity students may therefore become more engaged with and invested in their language learning, which is crucial for reversing the declining trend in language learning in schools highlighted in the introduction to this paper. We suggest, therefore, that there is another ‘E’ in play here, and that our intervention of participative multilingual identity education could serve as a transformational process to support the development of students’ multilingual identity in the languages classroom (see ).

Crucially, evidence presented elsewhere from the wider project indicates a further link between students’ multilingual identity and academic attainment more broadly (see Rutgers et al. Citationunder review). This therefore suggests that putting in place an intervention to shift students’ dispositions towards a multilingual identity may have wider implications for improving attainment and overall engagement with language learning. However, while the results from the current study are encouraging, we need to interpret them with caution. While our participating students come from four schools in very diverse settings, the sample size does not allow for us to make robust generalisations across all contexts. In addition, there are a range of other factors which may influence results (such as teachers, school ethos, linguistic diversity in the school and wider community) which space does not allow us to fully account for here. Nevertheless, the evidence presented in this paper points to the potential for an identity-based approach to contribute a new dimension to pedagogy in the languages classroom.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, for its support in funding this project under the auspices of the Open World Research Initiative. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments, and Harper Staples for her input into the theoretical and conceptual discussions. We are also incredibly grateful to the teachers involved in this study for their valuable feedback on the intervention resources and for their willingness and enthusiasm to incorporate these into their languages lessons.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

List of References

- Aronin, Larissa. 2016. Multi-competence and dominant language constellation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Multi-Competence, ed. Vivian Cook, 142–163. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aronin, Larissa, and Muiris Ó Laoire. 2003. Exploring multilingualism in cultural contexts: towards a notion of multilinguality. In Trilingualism in Family, School and Community, ed. Charlotte Hoffmann, and Jehannes Ytsma, 11–29. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Barcelos, Ana Maria Ferreira, and Paula Kalaja. 2011. Introduction to beliefs about SLA revisited. System 39, no. 3: 281–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.07.001.

- British Academy. 2019. Languages in the UK A Call for Action. doi:9780856726345.

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. British Educational Research Association. London. http://www.bera.ac.uk/publications.

- Ceginskas, Viktorija. 2010. Being ‘the strange one’ or ‘like everybody else’: school education and the negotiation of multilingual identity. International Journal of Multilingualism 7, no. 3: 211–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790711003660476.

- Chapman, Angela, and Allan Feldman. 2017. Cultivation of science identity through authentic science in an urban high school classroom. Cultural Studies of Science Education 12, no. 2: 469–491. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-015-9723-3.

- D’Antonio, Monica. 2020. Pedagogy and identity in the community college developmental writing classroom: a qualitative study in three cases. Community College Journal of Research and Practice 44, no. 1: 30–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2019.1649221.

- Department for Education. 2014. The National Curriculum in England: Framework Document. London: Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/381344/Master_final_national_curriculum_28_Nov.pdf.

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2011. Reflections on the emotional and psychological aspects of foreign language learning and use. Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies 22, no. 1: 23–42.

- Dressler, Roswita. 2015. Exploring linguistic identity in young multilingual learners. TESL Canada Journal/Revue TESL Du Canada 32, no. 1: 42–52.

- Erikson, Erik. 1968. Identity, Youth and Crisis. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Fisher, Linda. 2013. Discerning change in young students’ beliefs about their language learning through the use of metaphor elicitation in the classroom. Research Papers in Education 28, no. 3: 373–392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2011.648654.

- Fisher, Linda. 2017. Researching learners’ and teachers’ beliefs about language learning using metaphor. In Discourse and Education, ed. Stanton Wortham, Deoksoon Kim, and Stephen May, 3rd ed., 329–339. Cham: Springer.

- Fisher, Linda, Michael Evans, Karen Forbes, Angela Gayton, and Yongcan Liu. 2020. Participative multilingual identity construction in the languages classroom: a multi-theoretical conceptualisation. International Journal of Multilingualism 17, no. 4: 448–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1524896.

- Haukås, Åsta, André Storto, and Irina Tiurikova. This Volume. Developing and validating a questionnaire on young learners’ multilingualism and multilingual identity. Language Learning Journal.

- Heffernan, Kayla, Steven Peterson, Avi Kaplan, and Kristie J. Newton. 2020. Intervening in student identity in mathematics education: an attempt to increase motivation to learn mathematics. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education 15, no. 3: em0597. doi:https://doi.org/10.29333/iejme/8326.

- Henry, Alastair. 2017. L2 motivation and multilingual identities. Modern Language Journal 101, no. 3: 548–565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12412.

- Kaplan, Avi, Mirit Sinai, and Hanoch Flum. 2014. Design-based interventions for promoting students’ identity exploration within the school curriculum. Advances in Motivation and Achievement 18: 243–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-742320140000018007.

- Kramsch, Claire. 2009. The Multilingual Subject. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lamb, Terry Eric. 2011. Fragile identities: exploring learner identity, learner autonomy and motivation through young learners’ voices. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 14, no. 2: 68–85.

- Lanvers, Ursula. 2020. Changing language mindsets about modern languages: a school intervention. Language Learning Journal 48, no. 5: 571–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1802771.

- Lestinen, Leena, Jelena Petrucijová, and Julia Spinthourakis. 2004. Identity in Multicultural and Multilingual Contexts. London: CiCe Thematic Network Project.

- Melo-Pfeifer, Sílvia. 2015. Multilingual awareness and heritage language education: children’s multimodal representations of their multilingualism. Language Awareness 24, no. 3: 197–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2015.1072208.

- Nasir, Na'ilah Suad, and Jamal Cooks. 2009. Becoming a hurdler : how learning settings afford identities. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 40, no. 1: 41–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1492.2009.01027.x.41.

- Nassaji, Hossein. 2020. Statistical significance tests in language teaching research. Language Teaching Research 24, no. 6: 739–742. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820958512.

- Norton, Bonny. 2013. Identity and Language Learning: Extending the Conversation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Norton, Bonny, and Kelleen Toohey. 2011. Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching 44, no. 4: 412–446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309.

- Oyserman, Daphna. 2014. Identity-based motivation: core processes and intervention examples. Advances in Motivation and Achievement 18: 213–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-742320140000018006.

- Perez, Tony, Kristen H. Gregory, and Peter B. Baker. 2020. Pilot testing an identity-based relevance-writing intervention to support developmental community college students’ persistence. Journal of Experimental Education. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2020.1800562.

- Rutgers, Dieuwerke, Michael Evans, Linda Fisher, Karen Forbes, Angela Gayton, and Yongcan Liu. Under Review. Multilingualism, multilingual identity and academic attainment: evidence from secondary schools in England.

- Schachter, Elli P., and Yisrael Rich. 2011. Identity education: a conceptual framework for educational researchers and practitioners. Educational Psychologist 46, no. 4: 222–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.614509.

- Sinai, Mirit, Avi Kaplan, and Hanoch Flum. 2012. Promoting identity exploration within the school curriculum: a design-based study in a junior high literature lesson in Israel. Contemporary Educational Psychology 37, no. 3: 195–205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.01.006.

- Sorenson, Nicolas, Daphna Oyserman, Ryan Eisner, Nicholas Yoder, and Eric Horowitz. 2018. Developing and testing a scalable identity-based motivation intervention in the classroom. SREE Spring 2018 Conference Abstract.

- Taylor, Florentina. 2013. Self and Identity in Adolescent Foreign Language Learning. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- van Osch, Yvette, Marcel Zeelenberg, and Seger M. Breugelmans. (2018). The self and others in the experience of pride. Cognition and Emotion 32, no.2: 404–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1290586

- Vignoles, Vivian L., Seth J. Schwartz, and Koen Luyckx. 2011. Introduction: toward an integrative view of identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research, ed. Seth J. Schwartz, Koen Luyckx, and Vivian L. Vignoles, 1–27. New York: Springer.

- Vygotsky, Lev. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Waterman, Alan S. 1989. Curricula interventions for identity change: substantive and ethical considerations. Journal of Adolescence 12, no. 4: 389–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-1971(89)90062-6.

- Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2003. Emotions and teacher identity: a poststructural perspective. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 9, no. 3: 213–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600309378.