ABSTRACT

This study explores the dialogical nature of agency when two immigrant pupils, who are learning Finnish as their new target language, are authoring their selves. Bakhtin’s dialogism was the inspiration for this examination of the discourses that surround the L2 pupils’ agency and how they respond to discourses through their agency. Ethnographically oriented data collection included classroom observations, the pupils’ portfolios, and interviews with the pupils (as main participants) and meaningful adults. These data yielded a set of narratives from multiple voices. The results show that the pupils negotiate more subjective meanings of their selves, and re-color them with their internal goals and values, through the act of answerability, while the other sides of their selves react to others’ voices. It is concluded that we, L2 education providers, need to recognise the high level of engagement of young language learners’ agency and remember how our own voices might affect their navigation process of authoring their selves.

Introduction

I seek and find myself in another’s emotional-excited voice; I embody myself in the voice of the other who sings of me; I sing of myself through the lips of a possible loving soul. (Bakhtin Citation1990: 170)

Sometimes I need to know my saying would work out to ‘them’. (Katie – an immigrant child)

Although current applied linguistic research emphasises the active role of the individual in the learning process (Miller Citation2014), studies on children’s agency are still rare in research (see, however, Aro Citation2016; Koivistoinen Citation2016; Skinnari Citation2014). Even more rare are perspectives on immigrant children as active meaning makers and authors of their own multilingual identities; the studies on immigrant language learners have often focused on adults (Iikkanen Citation2019; Miller Citation2014; Pöyhönen and Tarnanen Citation2015). Understanding the experiences of immigrant children is, however, of foremost importance in attempts to develop sound practices and policies (Ibrahim Citation2016) for increasingly culturally and linguistically heterogeneous classrooms (Schwartz and Palviainen Citation2016). This study aims to address this gap in research on immigrant children as active agents by examining the language learning pathways of two immigrant children learning Finnish. Their agency is not, however, studied as an isolated phenomenon nor as an individual property, but as formed in a dialogic relationship with significant others (Miller Citation2014). To address this complex process, we draw on Bakhtin’s dialogial approach to agency and self.

From socioculturally to interactionally mediated agency

During the past two decades, the sociocultural approach to language learning has become more prominent in second language research (Miller Citation2014). As part of this change, the importance of learner agency is widely acknowledged (Miller Citation2014; Vitanova Citation2005). The shift of focus has been from ‘linguistic inputs and mental information processing to the things that learners do and say while engaged in meaningful activity’ (van Lier Citation2007: 46). The focus has turned towards ‘socioculturally mediated agency’ (Ahearn Citation2001): the agent as a user of sociocultural mediating means. For example, Norton and Toohey (Citation2001) analyse the language learning success of two of their research participants, one a young child in an English pre-school programme and the other an adult immigrant female. The authors describe the agentive actions taken by these two learners as they use available resources in order to gain access to desirable social networks, efforts that enhanced their English learning. Norton and Toohey (Citation2001: 317) indicate the need for researchers to consider how these individual actions develop in terms of how their social context evaluated the worth of their contribution. In this way, they introduce a view of human agency exercised in relation to the social world.

Miller (Citation2014), however, indicates that such L2 research implicitly or explicitly adopts a perspective on agency and language learning as something that is occurring in a ‘dialectic between the individual and the social – between the human agency of learners and the social practices of their communties’ (Toohey and Norton Citation2003: 58). She cautions against such perspective which may risk treating the learners as already agentive, without a careful consideration given to human agency (Miller Citation2014). Such a predeterministic view lacks a profound understanding of the interactional nature of human agency, which is thoroughly social, dynamic and co-constructed, rather than an a priori property of an indiviual as a ‘pre-given’ subject-agent (Price Citation1996: 332). Miller (Citation2014: 18) adds that in comparison to socioculturally mediated agency, Bakhtin’s dialogism will help better understand the interactionally mediated agency which represents ‘ongoing social struggles and the continuous social demands’ of human experience (Holland et al. Citation1998: 185). Not only have our well-developed higher mental functioning and complex consciousness emerged out of our participation in socioculturally meaningful actions; we are still individuals whose sense of self and agentive capacity is continually mediated through interaction with the social world. That is, an individual’s actions are only ever possible in dialogic relation to others (Miller Citation2014).

Sullivan and McCarthy (Citation2004) also point out that the sociocultural view on agency may become biased toward systems and activities rather than agents, and may become less suitable for understanding learners’ own viewpoints (Hicks Citation2000). They suggest that such a view needs to be enriched with individual sensibility: the affective and emotional aspects of an individual’s agency (Sullivan and McCarthy Citation2004). From a sociocultural outsider’s view of an individual acting within a system, the focus shifts to the interaction of that individual with that system (Dufva and Aro Citation2014; Vitanova Citation2005).

This shift has raised a growing interest in the dialogical viewpoint in research on L2 learner agency (Hicks Citation2000; Sullivan and McCarthy Citation2004). For example, Vitanova’s (Citation2005, Citation2010) study built on Bakhtin’s dialogism and the self, and examined issues of gender, culture and agency in the everyday discursive practices of adult immigrants as they acquired an L2. Miller (Citation2014) used both Vygotskian and Bakhtinian ideas in her study of adult immigrants learning English, in which she examined how the participants co-construct their agency in relation to language learning. However, young L2 learners’ agency has not, as yet, been extensively studied within the dialogical framework (however, see Aro Citation2016). This means there is a gap, to which the present study seeks to contribute by drawing on the dialogical approach to explore young L2 learners’ agency. This will enrich our understanding of the dimension of agency with individual sensitivity and explore the interactional nature of agency through the examination of the pupils’ felt, lived experience as expressed in their L2 learning.

Dialogical understading of self and agency

In dialogical thinking, individuals are connected to others through constant interaction with the environment – both physical and social – in which they find themselves (Kalaja et al. Citation2015). Davies (Citation2000: 60), in her search of women’s subjectivity in feminist stories, refers to a self as ‘one who can only exist by what the various discourses make possible, and one’s being shifts it with the various discourses through which one is spoken into existence’. Agency is manifested at any one moment. It is fragmented, transitory, a discursive position that can be occupied within one discourse simultaneously with its non-occupation in another (Davies Citation2000: 87). Agency enables the meaning of self to move between discourses, which position, negotiate and modify the self in the process of experiencing one’s subjectivity. In this sense, agency does not liberate the self from its discourses but stems from the self’s ability to mobilise existing discourses in new ways and to establish one’s unique voice (Davies Citation2000: 85).

Such understanding of self and agency resonates with Bakhtin’s dialogic meaning of self ‘as a conversation, often a struggle of discrepant voices speaking from different positions’ (Morson and Emerson Citation1990: 218). To Bakhtin, one becomes a subject only by participating in dialogue, and selfhood is fostered by something inherent only in the self: a voice carrying a distinct emotional-volitional tone in the presence of others in dialogue (Hall et al. Citation2004). Bakhtin (Citation1990) refers to the process of carrying such emotional-volitional tone in one’s voice as acts of ‘authoring self’ and this is the very human agency that he sought to describe.

Agency as act of authoring self: answerability

Dialogue, for Bahktin, is a socially embedded meaning-making process (Hall et al. Citation2004). It is impossible to voice oneself without appropriating others’ words (Aro Citation2016). The linguistic forms have already been used in a variety of settings, and language users have to make them their own by positioning them anew with their own accents. This process of appropriation of discourses and making them one’s own is an important aspect of agency (Hicks Citation2000). Bakhtin (Citation1981) contends that ‘responsive understanding’ entails the ability to read a particular situation and its discourses and navigate them in morally specific ways (Hicks Citation2000: 240). This active engagement with one’s situation through responsive understading can be explained with a central concept in Bakhtin’s notion of authoring, answerability (Bakhtin Citation1990). This notion points to the need for dialogues between selves who act to answer others’ actions. Dialogue here means a form of answering others’ voices and their axiological positions (Vitanova Citation2005). Bakhtin (Citation1993) viewed one’s whole life as a series of complicated acts and the self as a responsive human being putting one’s signature to the actions. More precisely, dialogue involves a form of ‘answerability’ (Bakhtin Citation1990), in which individuals, as responsive moral agents, are able to respond to the environment and answer the cacophony of all the multiple voices and navigate proactive meanings of selves (Hicks Citation2000). Drawing on the Bakhtinian meaning of authoring the self and agency, the pupils in our study are not seen as powerless puppets who are passively subject to external forces or learning variables (Dufva and Aro Citation2014). Their agency – the act of answerability – enables them to navigate their own voices with an emotional-volitional tone among the multiple voices around them. They, through the act of answerability, do not simply accept something given from the outside (Aro Citation2016); instead, they allow themselves to be aware of either contradictions or conformities between the inner and outer voices around them and the discursive constitution of the self as either contradictory or accordant with the others (Davies Citation2000: 74). Meanwhile, this interactional nature of process of authoring self through agency is inevitably influenced by the others. (Dufva and Aro Citation2014).

Research questions

As explained above, this study seeks to examine the dialogic nature of self and agency of two young immigrant learners of Finnish as L2 and to show how they navigate the multiple discourses around them to form the discursive sense of self. We have accordingly formulated two research questions:

How are the pupils’ self constructed and negotiated in relation with the voices of their parents and teachers?

How do the pupils, through agency, respond to the multiple voices and make them their own in authoring self?

The study

Participants and context of the study

This study was conducted with an immigrant family with four members (a Finnish father, American mother and two children). They moved to Finland from the US because of the father’s career. The main participants are the two children in the family. There are also other participants, including the mother and the two teachers of the preparatory class where the children started learning Finnish. gives information about the participants’ language use and background (Sun Citation2019). All the names used to refer to the family are pseudonyms in order to guarantee the participants’ anonymity.

Table 1. Language profile of the participants (at the time of data collection).

As described in , the dominant language spoken in the family is English. Although the two children were exposed to Finnish culture and language because of their father’s influence, their Finnish skills were not sufficient for them to study in a regular class at the time Author 1 met them. They therefore started their schooling in a class for pupils who need preliminary instruction in the Finnish language as their additional language, which is commonly referred to in Finland as a ‘preparatory Finnish language classroom’ and which, in this particular school, was given the name ‘Vary’. According to the Finnish Basic Education Act 5, special instruction preparing for basic education must be provided for immigrant pupils in Finland. The preparatory instruction is intended for immigrant pupils whose Finnish skills are not sufficient to study in a pre-primary school or in basic education (Finnish National Agency for Education Citation2009). At the time of data collection, the children had been learning Finnish for about two months, that is, since their arrival in Finland.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted during one semester (March ∼ June 2017) at the primary school in Finland where the preparatory class was located. The data include Author 1’s field notes from classroom observations, the pupils’ portfolios including drawings, and interviews conducted with the two pupils, their mother and the teachers. When some significant moments regarding the pupils’ learning acts were captured during the classroom observation, we further explored how the children acted through follow-up tasks such as language activities and interviews with them. Some parts of their portfolios were also selected to explore their language learning experience and detect their agency in their construction of self. Author 1, who conducted the interviews, was aware of her active participation in the analysis of data. displays the dialogical way of data collection along with the engagement of Author 1 and the participants. As the focus is on agency as it is experienced, this dialogical study of learner agency does not simply observe actions; instead, we use methods such as interviews to capture the participant’s own viewpoints (Kalaja et al. Citation2015). All of the multiple voices collected from the different forms of data were produced in tasks designed for this research. The voices of the participants then formed the narratives about the pupils’ self as language learners.

Table 2. Forms of collected data.

Data analysis

Creating narratives about the pupils’ authoring self

The analysis of the data occurred in two consecutive phases. Firstly, to show the multiplicity of voices echoing the pupils’ language learning, we created narratives about their self as language learners. Our goal in doing so was to understand the discursive nature of the pupils’ self with both the voices of meaningful others – who are significantly engaged in the pupils’ L2 learning (e.g. their parents and the teachers in the preparatory class in the context for this study) – and their own. We then adopted the Bakhtinian sense of narrative to construct the discourses about the pupils’ self for our methodology. Narratives, for Bahktin, mean zones of dialogic construction. They are the essential forms of story about a self (Vitanova Citation2005). In these narratives, a self is never a single consciousness but a polyphonic meaning-making process (Aro Citation2009). Speaking subjects in the narratives do not simply describe particular events and moments. Instead, they engage in an active dialogue with concrete others or ‘generalized others’ (Vitanova Citation2005) who do not necessarily show up in the dialogues but whose presence is potentially apparent within the narrator’s ‘emotional-volitional tone’ (Bakhtin Citation1990: 49–50). To create such narratives for Janne and Katie respectively, we began with pairing the multiple voices of the pupils’ own and others in the format of dialogues. Direct excerpts from the transcribed interviews and from the fieldnotes written up in the classroom observation by Author 1 were turned into the script of the dialogues that form each narrative. In other words, the narratives were not formed by actual conversations in which the participants talked to each other. Instead, they were narratives created by the authors to bring together the voices that surrounded the participants’ self as language learners. These narratives were grouped according to four central themes in the data. This process of establishing narratives was intended to conceptualise the pupils’ agency as socio-historically mediated and embedded in the voices of others from previous contexts (Bakhtin Citation1990) ().

Table 3. Four leading themes.

Learner agency in the narratives

In the analysis of the created narratives, we noticed that the pupils were active in authoring self both by reacting to others’ voices and by making sense of these voices for their own goals of language learning (Hicks Citation2000). To be more precise, agency was, firstly, present when the pupils reacted to the voices of other people who had the power to control their lives (Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate Citation2015). Agency was further present in the ways in which they were proactively engaged with the tension between themselves and others through either contradiction or conformity, and navigated towards their own goals instead of having them imposed on them by external authorities or circumstances (Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate Citation2015). Through this process, we sought to establish how the pupils interacted with others’ voices, based on which they made their own choices about how they valued events, others’ ideological discourses and power, still centered on their own morality, to navigate their own goals (Dufva and Aro Citation2014). Finally, we borrowed the term of ‘answerability’ (Bahktin Citation1990) to illustrate their acts of navigation, through which they realised their dialogical self.

Analysis

In this section, we present four narratives that represent the voices and themes that surround Janne’s and Katie’s language learning. We then investigate how the pupils’ and others’ voices either contradict or conform to each other.

Narrative 1. Janne as a Finnish speaker

I was imagining making myself a lot of friends when I actually get there … in the airplane. Later in 2016 … on my first day of (Vary) class, I was amazed at how much Finnish I already knew … coz I didn’t know that I knew that much Finnish (..)

In 4th grade (regular) class, there’s no fun. I don’t talk to other classmates. The Vary class is fun, but another emotion I have here (in the Vary classroom) is ‘I feel annoyed’. But .. in general, it’s more fun. I make friends with most of them and the teachers are quite nice. I think having good interaction with your classmates is the most important thing, but it’s also very important that you are respectful to the teachers.

Janne, from the beginning, tried to speak Finnish about whatever it was. In the beginning .. like the first two days, he was trying to use every Finnish word that he knew. I think he is a goal-oriented person. He is the most motivated one in the class. Maybe this is because his father is Finnish.

When he tried to approach the teacher’s table, he had to meet the boys who were yelling at the teachers and making a lot of noise. The boys tried to stop Janne. However, Janne gave only a quick glance at them and completely avoided them. He finally reached the teacher’s table and smiled at the teacher, asking, “I’m done. Can you check my answers?” (Classroom observation on 24 May 2017 / 13:45:15∼14:00:03)

I admire them (Janne and Katie). Is it tolerance? (..) There are lots of newcomers all the time. It’s very very wild here in this classroom .. children are quite noisy. But they (Janne and Katie) get on with their own work. They have to mind but they don’t complain. I think they used to live in a big city where most people must’ve been quite civilized .. so they learned how to behave in class. Or the parents taught them how to behave in class. They are so .. kind of.. kiltit lapset (good children)’.

Narrative 2. Impact of ‘time’ on Janne’s Finnish learning

I’m unique when I know Finnish because there aren’t many people who speak Finnish. When I go to America, I still want to keep speaking Finnish because it gives me ability if I want to come and work here (in Finland). If you learn a language, it gives you the ability to speak with millions of people (..) to be able to deal with anything. (..) Or what if I choose to go to the army back here? I also want to be a best story-teller with so many different languages.

He’s the first-born child and we weren’t so certain about the best choice for him when we decided to come to Finland. It was a big challenge. (..) He’s been lonely. He doesn’t have any friends who are fluent only in Finnish. English can be a huge hindrance for the kids’ Finnish acquisition. When we go back to the States .. in the US, there isn’t so much variety of choice for your second language learning at school. (..) He won’t be able to keep up his Finnish.

During break time, Janne is quite alone. Maybe this is because not many Finnish kids come up to him. It’s because of the language. It kind of separates him from the Finnish students. Janne is a stranger to them.

Narrative 3. Katie as a Finnish and English speaker

(Describing herself as a Finnish speaker) I can’t really carry any feelings because I can’t process what they are saying exactly. Sometimes it takes quite a while to understand them. (Describing herself as an English speaker) Here I am in Finland. This whole picture is me talking to my guinea pig in my room. One thing is probably the emotions I give to him. I can always speak English to him .. even though he is only a guinea pig. But I know that he is greatest in understanding me (See ).

Katie’s Finnish was quite .. little in the beginning. She is generally very shy in class. Of course, she does everything but she doesn’t come and ask for more. It could be about personality. I think Katie tries to learn but she is not so enthusiastic compared to Janne.

She’s very reserved at home. I think she’s very afraid of joining a group where she would have to speak Finnish. I think she’s really afraid of being in a situation like ‘I don’t know the word, I won’t be able to ask what I need’

Narrative 4. Impact of ‘spaces’ on Katie’s Finnish learning

I also try to speak Finnish, but normally I am speaking to them in English in Vary class. That’s actually a lot easier than speaking Finnish in second grade (regular) class because we are spending most of our time together. The second grade class..I found it a lot calmer. But it’s harder for me to speak to anyone than in Vary class. Because I know that anyone in Vary class will understand me. I know that I do not improve my Finnish that much in Vary class. But I wasn’t comfortable in the second grade class. Here (Vary classroom) everyone’s crazy. Still I can stand up in the middle. But I can’t stand up in the second grade class.

Katie’s standing next to the table that Janne and other students are sitting around. (..) Then she moves to her place to one of the tables in the middle of the classroom. She pays a lot of attention to the worksheet, sitting alone and keeping quiet. (..) After completing the task, she goes toward the back of the classroom where Amy was sitting. (..) Now she’s moving back to the teacher and watching her struggling to calm down a young boy. (Classroom observation on 17 April 2017 / 13:18:01∼13:44:09)

When they go their normal classes, they start their Finnish. After they stay there for one or two hours, they always want to come back here (Vary classroom) because this is their safety zone. It would be at first scary to go when there are 25 Finnish children looking at you, doubting ‘Where are you coming from? Who are you?’ It is a hard life for them.

Amy (a pseudonym for a classmate in the Vary class) and Katie are playing together a lot because they can speak English to each other. But I’m not sure it’s really good thing for children to have same mother tongue in the beginning.

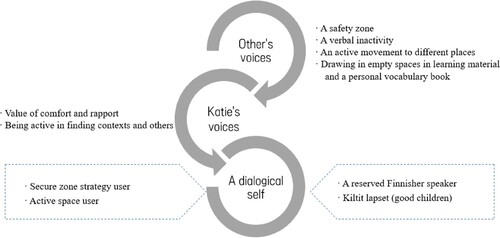

Furthermore, it is very apparent that Katie actively uses varied spatial elements as positive learning strategies to author her L2 self. She was observed moving to lots of different spaces to stay closer to the others (e.g. Janne, the teachers, Amy) in the Vary classroom. Although she appeared to be a verbally quiet and inactive learner, it was seen that she was actively moving herself to the places where she could meet other people. She also enjoyed using spatial elements to concentrate better on Finnish learning tasks; for example, she enjoyed using free space on the language worksheet and created geometric patterns with new Finnish words (see ). Here we can detect that Katie’s agency was presented in a more positive way in the Vary class than in the regular classes through her own unique voices.

This examination of the narratives has revealed a great deal of tension between the pupils’ and the adults’ voices. The adults tended to interpret the pupils’ learning behaviours mainly with static and predetermined variables such as personality, verbal linguistic output in class, family, up-bringing, and educational background. The pupils, however, interact with more dynamic and contextual variables such as relationships and rapport with others in language classrooms, time (Janne’s futuristic view) and space (Katie’s active use of varied spatial elements). This tension is further highlighted by another significant disparity. The adults tended to use more negative terms to describe the pupils’ identity such as shy, lonely and passive, an outsider, a big challenge for Janne and less enthusiastic, quiet, reserved, a big fear for Katie. In the middle of this tension among the voices, we detected that the pupils’ own emotional-volitional voices resonate positively and with an orientation to the future in authoring the meaning of their L2 self (Bakhtin Citation1990). Next, we illustrated further how the pupils, through agency, navigate their self with a focus on their internal goals and values among the multiple voices.

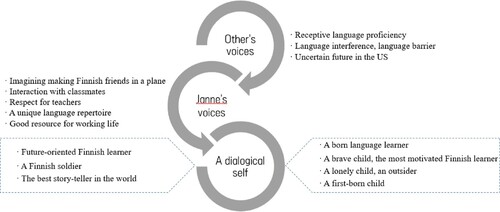

Learner agency in the presentation of the pupils’ dialogical self

In this section, we aim to answer research question 2 by examining how the two main participants of the study responded to others’ voices and made them their own. presents the ways in which Janne navigated the multiple voices surrounding his multilingual self. First of all, when we look at the multiple voices surrounding Janne’s self, we see that he, through agency, attempts to author a positive self that is in accord with his own goals and values. These include an optimistic and long-term view of his language learning and valuing rapport with others in class. At the same time, the tension between his and others’ voices shows the dialogicity of his L2 self (see ). In either the accordance or the disparity with these multiple voices, his emotional-volitional tone navigates the meanings of self towards his internal goals and values (Hicks Citation2000). The dialogical nature of his self manifests itself, on one hand, when he finds it difficult to integrate into the community of Finnish children and, on the other hand, when he reacts to the adults’ pessimistic views of him as a Finnish speaker, his agency proactively navigating himself towards an optimistic and promising way forward.

The tensions between the inner and outer side of the multiple voices surrounding her showed the dialogic nature of Katie’s L2 self in the same way as Janne. presents the ways in which she navigates the multiple voices surrounding herself. While she reacts to the passive and reserved self that is channelled to her by the voices of others, who mainly evaluate her verbal capacity as a Finnish speaker, her exertion of agency, by identifying secure zones in which she can establish understanding with others, the value she gives to rapport and the active use of spatial elements for her Finnish learning, have navigated her in such a way as to create an active and positive self in line with her internal goals and values.

Discussion

This study has explored two immigrant pupils’ agency in authoring self in a situation of learning Finnish as a new target language. Bakhtin’s dialogism has inspired the study at every stage. The ethnographic data collected through classroom observations, the pupils’ portfolios, and interviews with the pupils as main participants as well as with others yielded a set of multiple voices that, turned into dialogical interaction, made it possible to identify the two pupils’ agency and self (Morson and Emerson Citation1990). We identified their agency at the intersection where the cacophony among all the multiple voices impacts on the formation of dialogical self (Hicks Citation2000; Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate Citation2015). By looking at the dynamic tension among all the voices surrounding the pupils, we detected how Janne and Katie’s emotional-volitional voices, through agency, navigate toward the positive side of their L2 self (e.g. Janne’s choice of loyalties and relationships as his main values, Katie’s establishing a zone of understanding in speaking contexts, use of spaces, and the value she placed on rapport) (Bakhtin Citation1990). The models that we constructed of the two pupils’ selves helped us to understand how the multi-voiced nature of pupils’ voices, representing self and others, impacts and enriches the dialogicity of their L2 self. While one side of their self was formed in reaction to others’ voices, the other side of their self was negotiated. They, through agency, re-coloured the multiple voices around them and navigated towards their internal goals and values (Bakhtin Citation1990; Dufva and Aro Citation2014; Hicks Citation2000; Ruohotie-Lyhty and Moate Citation2015). Recalling Bakhtin’s definition of agency, we further identified how Janne and Katie’s deeper level of engagement in their personal consciousness – which is to say, the act of answerability (Bakhtin Citation1990; Vitanova Citation2010) – enabled them to deal with multiple voices, cope with others and particular relationships, through which they author their L2 self (Hicks Citation2000). We certainly detected some significant instances in which they exerted themselves in this act of answerability in their language learning situations. Using Bakhtin’s dialogical frame of the self as our starting point and examining their exertion of agency, we have been able to see how the pupils placed themselves in the best possible position in an unknown environment with others, centering themselves on their subjective values and morality and authoring self (Emerson Citation1996; Hicks Citation2000).

This study of immigrant pupils as active meaning-makers and authors of their own L2 self points towards some implications for immigrant pupils and L2 classrooms (Vitanova Citation2010). The dynamic tension between the immigrant pupils’ and others’ views helped to make sense of how the pupils’ agency is negotiated among multiple voices in the process of authoring their selves. We discovered that the L2 pupils’ self and agentive capacity were negotiated through an ongoing interaction with the others (Bakhtin Citation1981; Holland et al. Citation1998; Miller Citation2014). We also identified that the adults mostly judged the pupils in terms of static and predetermined variables. To us, these views can sometimes seem biased and may overlook the importance of the pupils’ subjective views (Aro Citation2016). Those biased voices might complicate or undermine the pupils’ agency (Bakhtin Citation1993). Through this study, we suggest that immigrant pupils’ voices be more attentively heard in the process of developing culturally and linguistically sound pedagogies in the L2 classroom (Schwartz and Palviainen Citation2016) and that pupils should be supported during the navigation process of authoring their L2 self through the acts of answerability (Bahktin Citation1990, Citation1993). Finally, we hope that this article can provide studies of pupil agency with more individual sensibility (Sullivan and McCarthy Citation2004).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahearn, L.M. 2001. Language and agency. Annual Review of Anthropology 30, no. 1: 109–137.

- Aro, M. 2009. Speakers and Doers: Polyphony and Agency in Children's Beliefs About Language Learning. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House.

- Aro, M. 2016. In action and inaction: English learners authoring their agency. In Beliefs, Agency and Identity in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching, eds. P. Kalaja, A-M.F. Barcelos, M. Aro, and M. Ruohotie-Lyhty, 48–65. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bakhtin, M. 1981. Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. 1990. Art and Answerability, ed. M. Holquist and V. Liapunov. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. 1993. Toward a Philosophy of the Act. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Davies, B. 2000. A Body of Writing: 1990–1999. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

- Dufva, H., and M. Aro. 2014. Dialogical view on language learners’ agency: connecting intrapersonal with interpersonal. In Theorizing and Analyzing Agency in Second Language Learning, eds. P. Deters, X. Gao, E. Miller, and G. Vitanova, 37–53. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Emerson, C. 1996. Keeping the self intact during the culture wars: a centennial essay for Mikhail Bakhtin. New Literary History 27, no. 1: 107–126.

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2009. National core curriculum for instruction preparing immigrants for basic education, https://www.oph.fi/english/curricula_and_qualifications/education_for_immigrants.

- Hall, K., G. Vitanova, and L.A. Marchenkova, eds. 2004. Dialogue With Bakhtin on Second and Foreign Language Learning: New Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- Hicks, D. 2000. Self and other in Bakhtin's early philosophical essays: prelude to a theory of prose consciousness. Mind, Culture, and Activity 7, no. 3: 227–242.

- Holland, D., W. Lachicotte, D. Skinner, and C. Cain. 1998. Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ibrahim, N. 2016. Enacting identities: children's narratives on person, place and experience in fixed and hybrid spaces. Education Inquiry 7, no. 1: 69–91.

- Iikkanen, P. 2019. Migrant women, work, and investment in language learning: two success stories. Applied Linguistics Review, doi:10.1515/applirev-2019-0052.

- Kalaja, P., F. Barcelos, M. Aro, and M. M. Ruohotie-Lyhty. 2015. Beliefs, Agency and Identity in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. London: Springer.

- Koivistoinen, H. 2016. Negotiating understandings of language learning with Elli and her parents in their home. Apples: Journal of Applied Language Studies 10: 29–34.

- Miller, R. 2014. The Language of Adult Immigrants: Agency in the Making. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Morson, S., and C. Emerson. 1990. Mikhail Bakhtin: Creation of a Prosaics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Norton, B., and K. Toohey. 2001. Changing perspectives on good language learners. TESOL Quarterly 35, no. 2: 307–322.

- Pöyhönen, S., and M. Tarnanen. 2015. Integration policies and adult second language learning Finland. In Adult Language Education and Migration. Challenging Agendas in Policy and Practice, eds. J. Simpson, and A. Whiteside, 107–118. New York: Routledge.

- Price, S. 1996. Comments on Bonny Norton Peirce's ‘Social identity, investment, and language learning’: a reader reacts. TESOL Quarterly 30, no. 2: 331–337.

- Ruohotie-Lyhty, M., and J. Moate. 2015. Proactive and reactive dimensions of life course agency: mapping student teachers’ language learning experiences. Language and Education 29, no. 1: 46–61.

- Schwartz, M., and Å. Palviainen. 2016. Twenty-first-century preschool bilingual education: facing advantages and challenges in cross-cultural contexts. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 19, no. 6: 603–613.

- Skinnari, K. 2014. Silence and resistance as experiences and presentations of pupil agency in Finnish elementary school English lessons. Apples: Journal of Applied Language Studies 8, no. 1: 47–64.

- Sullivan, P., and J. McCarthy. 2004. Toward a dialogical perspective on agency. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 34, no. 3: 291–309.

- Sun, D. 2019. Learner agency of immigrant pupils in a Finnish complementary language classroom context. Masters diss., University of Jyväskylä.

- Toohey, K., and B. Norton. 2003. Learner autonomy as agency in sociocultural settings. In Learner Autonomy Across Cultures: Language Education Perspectives, eds. D. Palfreyman, and R.C. Smith, 58–72. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Lier, L. 2007. Action-based teaching, autonomy and identity. International Journal of Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 1, no. 1: 46–65.

- Vitanova, G. 2005. Authoring the self in a non-native language: a dialogic approach to agency and subjectivity. In Dialogue with Bakhtin on Second and Foreign Language Learning: New Perspectives, eds. K. Hall, G. Vitanova, and L.A. Marchenkova, 138–157. New York: Routledge.

- Vitanova, G. 2010. Authoring the Dialogic Self: Gender, Agency and Language Practices. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.