ABSTRACT

Despite the difficulty of defining young adult literature (YAL), the benefits of it have been well recognised for adolescent learners. With the aim of exploring pedagogical approaches to L2 literature, this study reports on a YAL reading programme carried out in a secondary EFL classroom in China. To gain both teacher and student perspectives, data were collected from three main sources: semi-structured interviews with the teacher and student participants (N = 3); teacher’s reflective journal; students’ written works published on a social media platform (N = 304). Following the comprehensive approach model of L2 literature teaching [Bloemert, J., A. Paran, E. Jansen and W. van de Grift. 2019. Students’ perspective on the benefits of EFL literature education. The Language Learning Journal 47, no. 3: 371–384.], the teaching activities of the reading programme carried out over ten weeks arepresented and analysed, illustrated by samples of students’ work. Findings of the study suggest that YAL has positive effects on teenage L2 learners including interest in the story and relatable protagonists, enhanced understanding of the embedded culture, and personal growth. Teaching activities conducted in this programme are categorised into facilitating activities and reading tasks. Two principles for L2 literature teaching are drawn out of the teaching activities: providing others’ perspectives and eliciting students’ perspectives on the novel; and integrating multimodal production into literature teaching. Detailed implications for future practice are explored.

Introduction

Literature demonstrates an advanced usage of language, created with the highest level of skills that a language user could display (Bassnett and Grundy Citation1993), which can ‘engage, change, and provoke intense responses in readers’ (Hunt Citation2005: 1). Young adult literature (YAL), a genre of literature oriented towards adolescent readers, addresses various coming-of-age issues and therefore is potentially more accessible for teenage learners, including L2 learners (Chambers Citation1985; Richardson and Eccles Citation2007). Literary texts encapsulate language in subtlety, intricacy and nuances of meaning (Fleming Citation2007), thereby serving as a reservoir of authentic language for language learners. Literature can be regarded as a facet of culture, enabling readers to experience other cultures, while the vicarious experience may prepare them for future cultural communication and exchange (Rosenblatt Citation1995/2016). However, akin to other types of authentic text, literary works may be linguistically challenging for L2 learners, especially for intermediate and lower language learners (Macalister and Webb Citation2019). This being the case, young adult literature (YAL), literature written for and about adolescents, may be appropriate reading materials for teenage L2 learners. First, relatable protagonists and relatively lesser linguistic challenge may make YAL more accessible and attractive to adolescent learners compared with classics or literary works intended for other age groups (Day and Bamford Citation1998). Second, the comprehensible and compelling content should motivate students to actively engage in the reading, which should lead to enhancement of target language acquisition (Krashen, Lee, and Lao Citation2018). In addition to the benefits for language acquisition, YAL also contributes to the identity building of teenage readers who are experiencing a vital life stage (Trites Citation2014) and whole-person education by fostering readers’ cognitive, affective and psychological developments (Hall Citation2005). Pedagogical approaches to L2 literature are generally grouped into three categories: a language-based approach, literature as content and literature for personal enrichment (Carter and Long Citation1991; Lazar Citation1993). A latest model created by Bloemert et al. (Citation2019) outlines four directions in which teachers can approach literary works in L2 classrooms: text, context, reader and language orientations. In addition to the three well-established criteria, this comprehensive approach model highlights readers’ own interpretation of the text, drawing on their personal experience and prior knowledge.

Literature provides the drive to read and therefore promotes the acquisition and development of literacy (Sawyer Citation1987). With the advent of information technology and digital innovation, literacy pedagogy (L2 teaching included) has been progressing tremendously. The proliferation of communication channels and digital tools necessitates a pedagogy of multiliteracies, integrating different modes of meaning-making in literacy practices (New London Group Citation1996). Visual or audio materials, graphic or symbolic representations and any other modes of communication are encouraged in the process of semiotic translation of literacy. The combination of multiple modalities helps close the gap between teacher-centred assessment-driven pedagogy and student-centred purpose-driven learning (Thibaut and Curwood Citation2018). Meanwhile, transforming one type/mode/genre of text into another requires crossing language barriers and therefore escalates conceptualising and promotes deep learning (Meyer Citation2016).

In the context of Chinese secondary schools, YAL has been experimentally used in EFL classrooms in regions where English education is comparatively advanced. Concurrently, there has been a discernible increase in empirical research addressing this topic in the past decade or so. A review of three recent studies (Sun Citation2021; Yan Citation2016; Zhang Citation2018) carried out in similar educational contexts leads to the conclusion that L2 literature teaching is prevailingly language-based, and students’ perspectives were not included in these studies. Some studies carried out in a broader context explored students’ perceptions but mostly with quantitative methods (e.g. Bloemert, et al. Citation2019; Tsang et al. Citation2020). Gaining a deeper understanding of students’ perspectives, particularly on specific pedagogical activities, could help teachers/educators evaluate and refine the designs (Nation and Macalister Citation2010). Meanwhile, teachers’ views on the rationale for teaching practice and employed strategies can contribute to an in-depth understanding from the perspective of context-sensitive pedagogy (Littlewood Citation2013). Thus, including both teacher’s and students’ perceptions on YAL teaching in EFL classrooms, the current study scrutinises a YAL reading programme carried out in a secondary school in Beijing.

Literature review

YAL and L2 teaching

Young adult literature, as the name indicates, is a genre of literature written for and about young adults (Bull Citation2011; Glaus Citation2014). Since adolescent and young adult are commonly interchangeably used (Kroger Citation2000), YAL is also defined as ‘the novel specifically marketed to an adolescent audience’ (Trites Citation1998: xi). However, many YAL writers revealed that when they created a novel, they did not envision the target readers; rather, they just focused on building characters and the storyline (Bond Citation2011). To make defining YAL even more complicated, there is no clear dividing line between children and young adults. According to Chambers (Citation1985), Sarah Trimmer was the first educationalist who distinguished books oriented towards children and young adults at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the age of 14 was set as the dividing line between these two groups of readers. Of course, many scholars do not follow this division. Some (e.g. Alsup Citation2010) hold that YAL is intended for teenage readers between 12 and 18 years old, while others (e.g. Bucher and Hinton Citation2014) define the age group as 12–20 years old. Notwithstanding the disparity in specifying the target audience, YAL has a distinctive feature compared with other genres of literature: it conceptualises growth – an important and sometimes painful phase of life leading to adulthood (Trites Citation2014). Thus, YAL tells coming-of-age stories, which concern those who are crossing the threshold of childhood into young adulthood and address issues that adolescent readers can easily relate to (Burger Citation2016; Cadden Citation2011; Coats Citation2010).

Benefits of reading YAL for adolescent learners are multitudinous and impossible to list exhaustively. First, YAL can be enlightening and transformative because it enables readers to negotiate and renegotiate identities in aspects such as gender roles, ethnic and racial identification (Chambers Citation1985; Di Martino Citation2019; Richardson and Eccles Citation2007). In the process of self-transformation, subjectivity, the sense of personal identity distinct from other selves or positionality in society in relation to others, is fostered due to the dialogic intercourse with the narratives which are laden with social ideologies and discourses (McCallum Citation2012). YAL also helps readers comprehend the world through vicarious experience in literature. These vicarious experiences may help young readers question and critique stereotypes, oppression, injustice and the limitations of normality and assist them in transcending these limitations to achieve the power of agency (Hilton and Nikolajeva Citation2012). At the cognitive level, engagement in, and interpretation of, literary works, canpromote analysis, evaluation, synthesis and other high-order thinking skills (Nagayar et al. Citation2015). With benefits in such a wide range of aspects, YAL presents itself as an invaluable source of texts for adolescent learners to further perception and deepen understanding of the intricate relationships between Self, Other and the world with enhanced sociocultural knowledge as well as affective and cognitive development.

In L2 classrooms, in addition to the merits presented above, YAL possesses other values for adolescent learners with respect to language acquisition and cultural awareness. YAL may help compensate for the lack of natural language environment with the vividness of its literary world construction (Burke and Cutter-Mackenzie Citation2010). Therefore, for learners who do not have the chance to go to the countries where the target language is used, reading YAL may serve as a substitute, although obviously, vicarious experience cannot completely replace real-world experience. Compared with other types of literary works, YAL is more accessible and engaging due to relatable protagonists and empathetic conflicts. The relevance and accessibility of YAL may attract young learners to the textual world and language environment, which may incrementally improve their L2 acquisition (Groenke and Scherff Citation2010). Meanwhile, the compelling content and intriguing language could boost learners’ motivation for the language study (Maley Citation1989; Van Citation2009). Closely related to the language immersion that YAL offers, it should also enriche and enhance L2 learners’ intercultural understanding and competence with the embedded culture and customs of the target language (Carter and Long Citation1991; Khatib et al. Citation2011; Lee Citation2013). The reciprocal relationship between literature and culture also implies that lack of relevant cultural background knowledge may give rise to difficulty in understanding text or the study of the language in a broad sense (Wallace Citation1992). In light of this, it is legitimate to integrate culture-related competence into L2 literature teaching, such as cultural competence, critical cultural literacy and intercultural communicative competence (Bland Citation2013; Serafini Citation2005). Considering all the potential benefits of YAL for young language learners, albeit with challenges in practice, it is worth considering YAL as suitable reading material and a useful language teaching tool in L2 classrooms (Day and Bamford Citation1998).

Theoretical frameworks and concepts applicable to YAL teaching in L2 classrooms

Pedagogical approaches to L2 literature have gone through several phases. Traditional approaches highlighted features of literature as ‘the highest level of (language) achievement’, and therefore classic and canonical works were commonly used for their linguistic and literary values (Hall Citation2015: 19). In the 1980s and 1990s, the popularity of the communicative language teaching approach led to greater recognition of literature in L2 classrooms, promoting it as authentic and imaginative use of language. Replacing the original utilitarian use of literature (through a language-focused approach), a content-focused approach was foregrounded in this period (Bland Citation2013). In addition to the language-based and content-focus approaches, using literature for personal growth and enrichment was another teaching orientation of L2 pedagogy (Carter and Long Citation1991; Lazar Citation1993). The latest theoretical developments in this field are reflected in the comprehensive approach model of L2 literature teaching (Bloemert et al. Citation2019), which integrates the key elements of previous frameworks regarding L2 literature teaching. The comprehensive approach consists of the text approach (focusing on literary discourse, genres and related terminology and knowledge), the context approach (seeing literature as embodiment or reflection of sociocultural and historical backgrounds), the reader approach (emphasising readers’ independent interpretation of the text and critical thinking) and the language approach (focusing on the language per se as authentic texts). In addition to what previous models highlighted in L2 literature teaching, readers’ creativity and originality in their understanding of the text is also incorporated in this comprehensive approach.

In tandem with the development of L2 literature teaching approaches, the pedagogy of multiliteracies has been gaining popularity in literacy research and practices. As the New London Group (Citation1996: 81) claimed, ‘all meaning-making is multimodal’, which legitimises the integration of different modes of meaning-making, including but not confined to textual, visual, audio, spatial, behavioural elements in interpretation of meaning. Alternatively, some scholars use the term pluriliteracies to place emphasis on hybridity of literacy practices, drawing on modern technologies and the interrelationship of semiotic systems (García et al. Citation2008, 10, emphasis in original). Another closely related term – multimodality – also underlines the combination of different modes in meaning-making and communicative intercourses (Adami Citation2016). One major benefit of involving multimodality is that in the process of generating meaning across modes, genres and styles of text, the semiotic translation of literacy gives rise to deep learning and multi-dimensional acquisition (Meyer Citation2016). Thus, it is fair to conclude that integrating textual variations, be it audio or video materials, graphic or symbolic representations or any other modes of communication in literacy pedagogy could conceivably enhance linguistic development along with cognitive and higher-level processing skills.

Recent research in similar teaching contexts

As mentioned earlier, teaching YAL and children’s literature in secondary EFL classrooms in China is still at an initial stage, although empirical research in this field is on the rise. This section introduces three case studies conducted in different regions of China, all exploring L2 literature teaching in secondary EFL classrooms (see ).

Table 1. Three studies of teaching L2 literature in Chinese secondary EFL classrooms.

As demonstrates, the three case studies reflected some elements of Bloemert et al.’s (Citation2019) comprehensive approach model, but not all. Among the four criteria, the language approach was predominantly adopted and the reader approach was largely reflected in post-reading activities. In comparison, limited focus was given to the sociocultural and literary backgrounds of the novels. In other words, the text approach and the context approach were not adequately demonstrated in these practices. Another shared feature is that students’ voice and perceptions were not included in the research ; thus, the discussions were chiefly teacher-centred. Adding to the existing literature, the current study scrutinises activity designs of a YAL reading programme from both teacher and student perspectives. It sets out to answer the following two questions:

What are the features of the pedagogical activities used to support YAL teaching in a secondary EFL classroom in China?

What are teacher and student perspectives on YAL reading activities and post-reading tasks?

Methodology

The research context

This study was part of the author’s doctoral research which investigated ten extensive reading programmes in different secondary schools in China. There are two reasons (related to the research questions) for the selection of the particular case reported in the current study. Firstly, this reading programme used a YAL novel as the reading material; secondly, the programme demonstrated a detailed and complete process of teaching a novel in L2.

Lily (the pseudonym of the teacher participant) had been teaching EFL for 13 years. The school in which Lily was working is a key middle school located in downtown Beijing with a history of almost 100 years. The two classes Lily was teaching were Junior Three English experimental classes (aged 14–15). As an incentive to recruit students, most of the students in English experimental classes did not need to take the Senior High School Entrance Examination to continue studying in this school. Time saved from preparing for the high-stakes examination enabled these students more freedom to study in a way they and their teachers considered beneficial. This was the third year that Lily was teaching these students and she used Senior One (one year ahead of her students’ grade) English textbooks as a reference but did not strictly follow their structure. In the previous two years, Lily had incorporated in-class reading of graded readers, short stories and children’s books (e.g. Charlotte’s Web) into her EFL teaching. The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton was the first young adult novel that Lily used in her class.

Data collection

To achieve triangulation and therefore increase the credibility of this qualitative case study (Flick Citation2017), data were collected from three main sources: semi-structured interviews with the teacher and three students (coded as S1, S2 and S3); 304 items of student work related to the reading programme; and the teacher’s reflective journal. The interviews were conducted individually with each participant when the reading programme was completed. The three studentshad volunteered to participate in the interviews which were conducted in Chinese (L1 for participants and the researcher). The interview with the teacher lasted for approximately one hour and the interviews with each student lasted 30 minutes or less. All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the researcher.

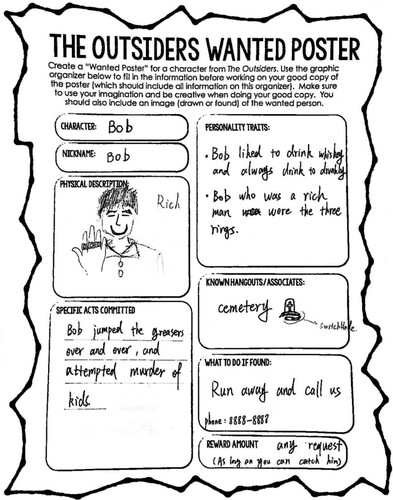

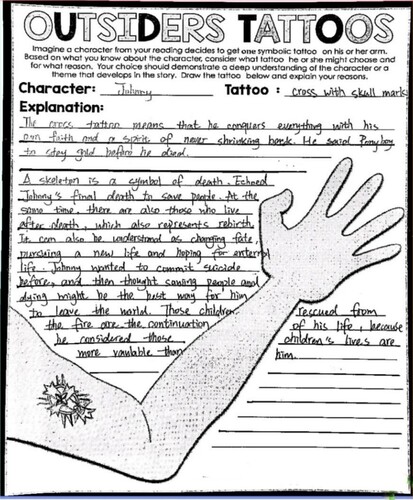

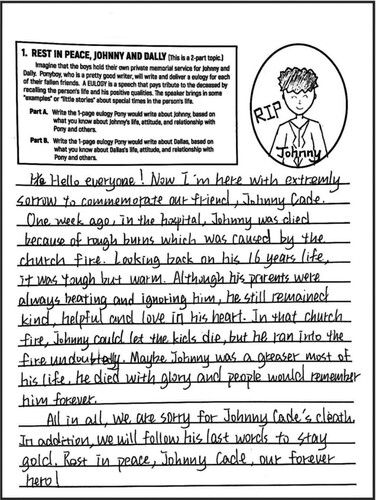

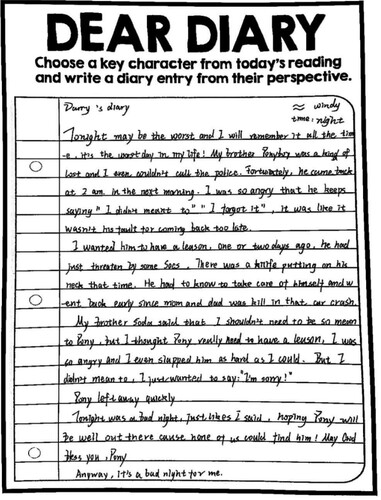

To enable students to share work, Lily selected and published students’ writings and other forms of output related to the novel reading on a social media platform. As a source of data, some items of student work were used as samples of students’ achievement of learning outcomes in this article (see Figures ). Two principles were followed for the sample selection: that the work was clearly legible; and that it amply fulfilled the task (each task was presented prior to the work on the platform). Informed consent was given by the teacher and students involved, and all student work used for the study was anonymised to ensureconfidentiality (Wiles et al. Citation2008).

While implementing this reading programme, Lily produced a reflective journal entry each week to record the rationale for her activity design and reflections on students’ responses and work. In total, Lily created ten journal entries corresponding to the ten weeks of reading activities, and these served as another source of data for the analysis of the pedagogical activities comprising this L2 reading programme, specifically addressing Research Question 1.

Data analysis

I followed the six steps of thematic analysis to interpret the data collected from the interviews and the teacher’s reflective journal (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). I first analysed journal entries and transformed my confusion and thoughts about the content into interview questions. After conducting each interview with student and teacher participants, I immediately transcribed the interview to allow memory of details to come into play. I adopted the orthographic transcription method, recording all verbal utterances from all speakers with no amendment or correction (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). In the process of coding, I implemented thorough coding which was not influenced by any pre-set framework except the research questions (Linneberg and Korsgaard Citation2019). According to the initial codes, I detected some emergent themes, including perceptions of the novel, facilitating activities, reading tasks, teacher-led reading, difficulty of the text, benefits of the reading and expectations of pedagogical improvement. Based on the emergent themes, I identified and worded the final themes and used them as the subheadings for the Findings section below. Considering the nature of the study and the research aims, the items of students work (n = 304) were not analysed in depth. Rather, they were mainly used as demonstration of students’ achievement of learning outcomes and guided the generation of interview questions (Rapley Citation2018).

Findings

Pedagogical activities related to L2 YAL teaching

This reading programme lasted for ten weeks. In the first five weeks, students read the novel and completed relevant reading tasks, while in the second half of the programme, assessment of students’ reading skills and overall analysis of characters and themes were conducted (see ). This section adopts the comprehensive approach to L2 literature teaching (Bloemert et al. Citation2019) and uses the four criteria – text, context, reader, language – as the framework to present and analyse the reading activities implemented in Lily’s reading programme.

Table 2. Teaching schedule and activities for The Outsiders.

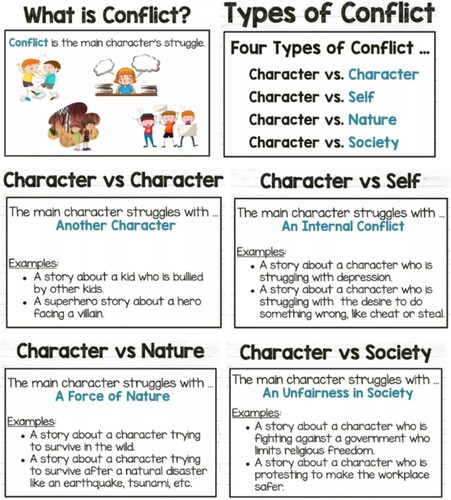

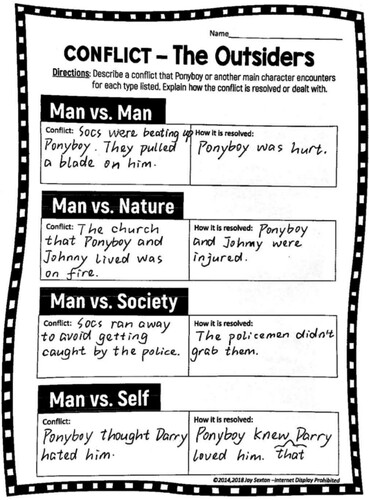

In terms of text approach, literary elements such as character depiction, conflict analysis, identifying themes (embedded in chapter questions) were integrated into the reading activities. Taking ‘conflict analysis' as an example, this activity was carried out after students had finished reading the novel, and consisted of three teaching steps: learning background knowledge (see ); differentiating conflicts in exercises; and identifying conflicts in the novel (see ). The three steps respectively symbolised theoretical/conceptual input, teacher scaffolding and output in actual reading.

The reader approach was embodied in activities that necessitated students’ independent interpretation of the text, including chapter questions, free-writes, making and confirming predictions and Costa's 3 levels of thinking (see for example What Are Costa's Levels of Questioning? (teachthought.com)). For example, in Chapters 1–2, Lily raised the following questions for students to answer:

What symbolical roles within the family do Darry and Sodapop play?

Why does S.E. Hinton use warm colours to describe the Socs and cool colours to describe the Greasers?

Why are the Greasers considered outsiders of the society? (Lily Journal 1)

These questions, if examined closely, include analysis of character, symbolism and themes of literature. Rather than asking questions using specialist jargon, these questions were worded in a way fully accessible for teenage learners. Compared with chapter questions, free-writes was more topic-specific and permitted students more freedom of their own interpretation. For instance, the free-writes task in Week 2 was:

Ponyboy tells us, ‘Dallas Winston could do anything’, and when the boys are in trouble, he just does that! He even provides a loaded gun.

*Do you think Dally is a positive influence on Pony and Johnny or a negative influence?

*Think about Dally’s background and personality … What makes him a good guy or a bad guy? Use reasons and examples. (Lily Journal 2)

Focusing attention on a citation about one character, this task elicited students’ personal opinions and critical thinking. Lily not only asked students questions, but also trained them to ask questions about the novel. In the Costa's3 levels of thinking activity, Lily gave students the following instructions:

Level 1 – Gathering: you can directly find the answer from the text, e.g. ‘Who is the main character?’;

Level 2 – Processing: you can collect evidence from the text to produce an answer, e.g. ‘How does the action reflect the character’s personality?’;

Level 3 – Applying: you need to apply your prior knowledge to answering the question rather than find the answer from the text, e.g. ‘If you were the character, how would you solve the problem?’. (Lily Journal 4)

With these instructions, Lily provided opportunities for students to apply theory into practice: she asked students to read Chapter 7 and raise questions at different levels of Costa's scheme. Lily collected the questions and selected one from each student and shared them on the social media platform:

− Give me an example of Randy doesn’t want to fight? – Level 1

− What evidence can you find to support that Randy and Pony all changed their thoughts about the relationship between Socs and Greasers? – Level 2

− Why do you think Randy tells Bob's family background to Pony? – Level 3.

The context approach, which involves focusing on the sociocultural backgrounds of the story, was mainly reflected in the chapter questions that Lily raised. Take the question ‘Why are the Greasers considered outsiders of the society?’ (Lily, Journal 1) as an example again: rather than directly introduce students to the sociocultural background, Lily guided them to think about it and search for relevant information if necessary.

Regarding the language approach, Lily’s guidance was embodied in the assistance she offered in the in-class reading activity to facilitate students’ understanding of slang and other linguistically challenging items. Other than that, Lily did not explicitly address linguistic features of the text.

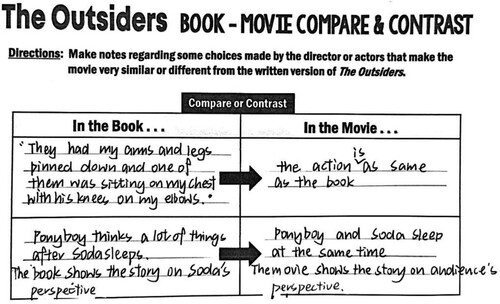

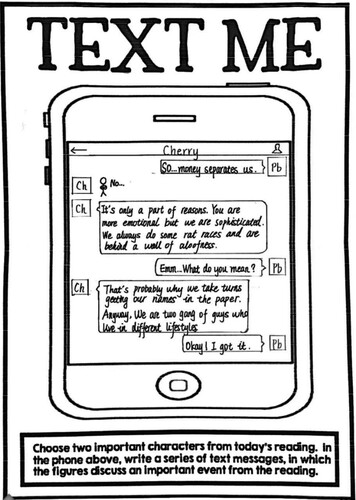

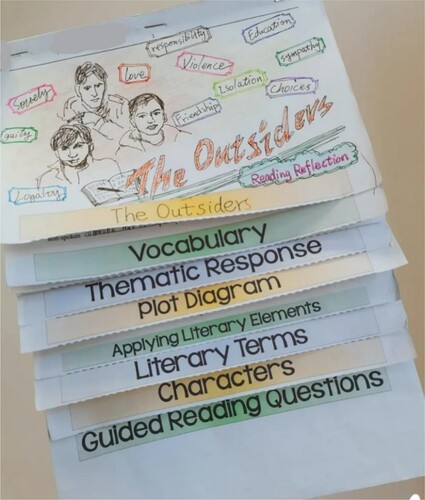

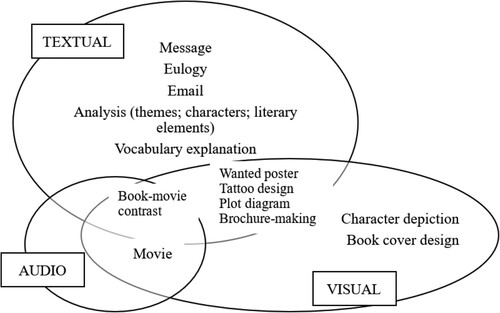

Multimodality was integrated into quite a few reading activities that Lily designed, such as 'Book-movie compare & contrast' (), 'Text me' (), 'Wanted poster' (), 'Tattoo design' (), 'Eulogy writing' (), 'Dear diary' () and 'Brochure-making' (). These activities in various forms combined textual, visual and video modalities into activity design. Samples of student work showcased a variety of lively and interesting combination of modalities and genres of text. In the case of 'brochure-making', after reading the novel, students were instructed to design a brochure of The Outsiders to report the outcomes of their reading, composed of eight sections: Book cover (visual); Vocabulary (textual and explanatory); Thematic response (textual and analytical); Plot diagram (visual and textual); Applying literary elements (textual and analytical); Literary terms (textual and explanatory); Characters (textual and analytical); Guided reading questions (textual and explanatory). Multimodal creation was a striking feature of this post-reading task which integrated a wide range of modes, genres and styles of text.

In addition to the brochures that students created as a presentation of their reading outcomes, Lily assigned students another summative task: writing a letter to the author of the book, ‘explaining to her what you have learned from this novel’ (Lily Journal 7). After collecting all the electronic letters from students, Lily compiled them and sent it to S.E. Hinton with the email address she found online.

The assessment activity concerning the novel reading focused on Chapters 9–11. Rather than covering the whole book, Lily explained the partial coverage thus: ‘I didn’t give much instruction in class about these three chapters, because I wanted to test how students could apply some strategies and knowledge they learnt in the previous chapters.’ (Lily Interview) This assessment task consisted of three sections: Reading comprehension (10 points); Skills (20 points) including plot, questioning, conflict and theme; and Writing (20 points). When summarising students’ progress in novel reading reflected in the assessment, Lily wrote the following in her journal: ‘Judging from the answers, students were able to have an in-depth analysis of the plot, pay attention to important details, identify the conflicts of the story, and have their own views on the themes and analyse them.’ (Lily Journal 8)

Teacher’s and students’ perspectives on the reading activities

Concerning the reasons for selecting this novel, Lily gave the following explanations. First, the author was a teenager when she created this novel, which made the book stand out among coming-of-age stories. Second, Lily herself had not read the novel before teaching it, which enabled her to maintain a learner’s perspective when reading and teaching it. Third, Lily had obtained some relevant materials about this novel, including the electronic version of the book, summary and analysis of each chapter created by experts in this field, and the movie adapted from the novel. These resources to a great extent facilitated her teaching.

Responses from student interviews showed that this novel was an appropriate choice for Junior Three students. All the three students interviewed mentioned the differences between The Outsiders and the books they had read previously. One said, ‘There’s quite a lot of slang, from which I learn about the richness of the language’ (S1). Similarly, the colloquial language was perceived by the other two students as ‘very helpful for understanding the local culture and customs’ (S2) and as embodiment of ‘liveliness of the language’ (S3). One student (S1) commented that compared with other English books they had read, this novel had a distinct feature – it covered many topics of growth, and therefore reminded them of their own experiences. This was elaborated upon by another student:

This novel deepened my understanding of family and affection between family members. At the beginning of the story, the protagonist had some prejudice against his eldest brother, unable to understand his love, but after going through many things, he finally understood this kind of love. (S2)

While I was reading the novel, my thoughts and emotions fluctuated with the protagonist, which I had never experience before … when reading other books, I needed to switch to a Chinese mode, but I didn’t need to do so for this novel … I guess it’s because I can relate to the protagonist quite well. (S3)

Students not only acknowledged the appropriate selection of the novel but also appreciated the reading tasks that Lily designed. One student provided a detailed comment on how these tasks deepened his understanding of the novel:

Sometimes these tasks covered topics that I really wanted to express my opinions about. Some activities are quite interesting, for example, designing a tattoo and writing a eulogy for a character … to finish these tasks, we need to think deeper to gain our own understanding. I think this is very helpful for our study. (S2)

I have collected many relevant activities from various resources about novel reading, and I can use these activities in different novels. For example, when I taught A Christmas Carol, I asked students to design a symbol for each character, while for The Outsiders, I asked them to design a tattoo for one character – these two activities are similar in essence. (Lily Interview)

I don’t think so. Watching the movie and reading the summary could help students figure out the relationship between characters and the main plot. The background knowledge from these sources facilitates their deeper understanding of the text. (Lily Interview)

Reading this novel is a bit difficult for me because of the new words … watching the movie and reading summaries were quite helpful for me; otherwise, I might be unable to understand a lot and consequently lose interest in it (S1)

The analysis that Lily shared with us is very helpful, for example, the symbolisation of colours in the novel … my understanding of it was a bit superficial, but after reading others’ analyses, I gained a more profound understanding of such details and the author’s intentions. (S2)

Regarding watching the movie, one student gave quite positive feedback:

Watching the movie became something that I expected each day … it intrigued my interest in the book. The protagonist also liked reading and watching movies, which made me and him even closer to each other. Lily asked us to compare the book and the movie … I think this could help us notice something we couldn’t have otherwise. (S3)

Another type of facilitation Lily provided was the combination of reading-aloud and thinking-aloud she conducted in class:

I extracted some passages from the novel and read them aloud to students; meanwhile I did some thinking aloud, for example, I might pause and say ‘I think this part is quite important because it reflects the character’s attributes’. I hope in this way they learn to read between the lines. (Lily Interview)

Another facilitating activity that Lily organised was publishing students’ work on a social media platform which was accessible to all the students, their parents, and anyone who was given the link. Two students gave positive comment on this form of presenting their works. One of them summarised the benefits as follows:

It gave us a sense of achievement, and parents could learn about our fruits of learning. Very importantly, we can see others’ works and learn from each other. (S2)

Discussion

Students’ perceptions of YAL and related reading activities

Data collected from the student interviews indicate that YAL can have substantial benefits for adolescent learners’ L2 reading and learning. First and foremost, coming-of-age stories can powerfully resonate with teenage readers, which may result in their eagerness to read the book. In the current study, two of the three interviewed students exhibited evident excitement when talking about how they enjoyed reading this book. One student perceived that their strong interest in the book reduced the difficulty in understanding the text by strengthening their strategies for guessing meanings of new words. This perception echoes some scholars’ (e.g. Groenke and Scherff Citation2010) supposition about the correlation between relatable characters in YAL and adolescent readers’ immersion in the text. Also corroborating previous literature (e.g. Khatib et al. Citation2011; Lee Citation2013), this study collected evidence from students concerning the positive effects of YAL on their (L2 learners’) understanding of the culture and customs embedded in the stories. Regarding the influence of YAL on students’ motivation for L2 learning (Maley Citation1989; Van Citation2009), this study added some fresh perceptions to the existing literature. In addition to the appeal of the novel itself, watching the movie adapted from the novel and carrying out various novel-reading tasks appeared to improve students’ motivation for reading and consequently L2 learning . Last but not least, there is evidence from this study showing that reading YAL can enhance readers’ perceptual development and personal growth (Carter and Long Citation1991; Lazar Citation1993). As one student revealed, the book enabled him to broaden his understanding of love and affection between family members.

The teacher’s facilitation and scaffolding in L2 literature teaching

In the reading programme under discussion, teacher scaffolding took two main forms: facilitating activities and reading tasks. Drawing on Bloemert et al.’s (Citation2019) comprehensive approach to L2 literature teaching, the analysis of reading tasks and facilitating activities implemented in the reading programme falls into the categories of context, text, reader and language approaches.

Facilitating activities enable students to gain knowledge about the sociocultural and historical context of the story and literary devices applied to the writing, reflecting the context approach and the text approach respectively. In Lily’s reading programme, watching the movie, reading others’ summaries (before students’ own reading) and reading others’ analyses (after students’ reading and discussing the chapter) were the main facilitation that the teacher provided. Students’ feedback and written work indicate that involving intertextuality (e.g. transforming written text into non-written text relating to the literary work) and others’ perspectives could broaden and deepen students’ understanding of contextual knowledge about the story and enhance their literary interpretation and appreciation. Teaching about literature is essential especially for L2 readers because the gap in culture and language may pose formidable obstacles to the reader (Wallace Citation1992). Another important facilitating activity – sharing students’ work on a social media platform – was well received by the interviewed students. This finding corresponds with a case study conducted in Belgium, in which the teacher researcher concluded that utilising information technology in L2 literature teaching could enhance students’ motivation for the reading activities (Johan Citation2013). This also affirms the supposition that involvement of digital media in teaching activities may improve learner engagement (Coyle and Meyer Citation2021).

In addition to facilitating activities which are oriented to teaching about literature (i.e, text approach and context approach), reading tasks serve the main purpose of teaching literature which necessitates the reader’s deeper engagement and independent interpretation of the text (i.e. reader approach and language approach) (Bloemert et al. Citation2019; Short and Candlin Citation1986). The current study introduced various tasks designed for teaching the novel The Outsiders. Summarising the features of these activities, three themes emerged. From teachers’ perspective, the strategies for designing L2 literature activities are transferrable, which means reading activities designed for one novel can be recycled for other novels. Specific strategies will be elaborated upon in the following section. From students’ perspective, the variety of reading tasks enhanced their interest and engagement in the reading and post-reading activities. One student in this study attributed his deepened understanding of the text to the varied forms of communication of ideas, which in turn stimulated his interest in reading the novel.

It is important to note that different from some relevant studies carried out in similar contexts (e.g. Sun Citation2021; Yan Citation2016; Zhang Citation2018), the findings of the present study did not demonstrate a leaning towards language approach in the YAL reading programme under study. Except the Vocabulary section in brochure-making, language approach was not explicitly employed in Lily’s activity design. However, this study shares similarity with the previous studies in that reader approach was adopted in the main form of writing-after-reading activities in which students expressed their interpretation of the text in various written forms. Specifically replicating Sun’s (Citation2021) finding that writing-after-reading activities could deepen students’ understanding of the text, this study collected evidence from students affirming this proposition.

Two principles of activity design for L2 literature teaching

Based on the strategies demonstrated in Lily’s novel reading activities, two principles are outlined to inform future practice and encourage further discussion into L2 literature teaching.

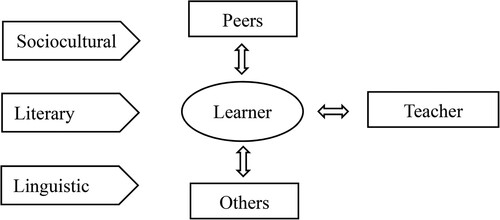

Principle 1. Providing and eliciting multiple perspectives

Drawing on and adding to the comprehensive approach (Bloemert et al. Citation2019), perspectives involved in novel reading not only include sociocultural, literary and linguistic aspects of the literary work (respectively relating to context, text, and language approaches) and the reader’s own interpretation (reader approach), but also include other readers’ perspectives, encompassing teacher’s, peers’ and competent others’ perspectives (see ). First, the teacher’s perspective is indispensable. As one student in the current study revealed, when the teacher shared with them her understanding of the text, especially about linguistic and literary elements of the novel, this student found it easier to comprehend some details, including slang and other colloquial expressions. Peers’ perspectives were, however, no less important according to the students’ feedback. When commenting on utilising social media to share their work, one student stated that peers’ perspectives could enrich and expand their understanding of the novel. Another source of perspective is from competent others, be it experts in this field or teachers who have taught this novel, which was recognised as very helpful by the student participants who had limited knowledge of the sociocultural background involved, and of literary genres and techniques. The wrap-up reading activity – creating a brochure of the novel – is a typical example of approaching a literary work from differing perspectives. The eight sections of the brochure could be categorised into three groups: literary perspectives (i.e. Book cover; Thematic response; Plot diagram; Applying literary elements; Literary terms; Characters), reader’s perspectives (i.e. Guided reading question) and linguistic perspectives (i.e. Vocabulary).

What merits attention is that although the student were provided with a variety of channels to present their opinions about the novel (mostly in written forms in this study), the student participants interviewed expressed their hope for more chances to share their perceptions especially in class. This expectation could be regarded as resulting from a lack of collaborative activities in which students may freely express their thoughts about the reading. In this sense, the finding corresponds with Zhang’s (Citation2018) study which highlighted the importance of collaborative activities in L2 literature teaching.

Principle 2. Integrating multimodal production into L2 literature teaching

In the reading programme under discussion, various forms of meaning-making were involved in the post-reading tasks, including textual communication, visual presentation and multimodalities such as Wanted poster and Tattoo design (see ). Take the brochure design as an example again. In fulfilling the task, students engaged with a kaleidoscope of communication modes, including textual representations (e.g. vocabulary explanation, thematic response, application of literary elements, character analysis and guided reading questions), visual creation (e.g. book cover design) and multimodal presentation (e.g. plot diagram). Corroborating the notion that transformation between different modes of meaning-making contributes to deep learning (Meyer Citation2016), the current study collected evidence from students showing that in the process of switching between different modalities of meaning-making, such as text message, eulogy, wanted poster and tattoo design, students’ understanding of the novel and cognitive thinking were deepened. More importantly, due to the variation of expression forms, students’ enthusiasm for reading and doing the post-reading tasks remained high from beginning to end. The involvement of digital media in publishing students’ works added another layer of modality to students’ products, which not only disseminated students’ learning outcomes to a wider audience, but also boosted their motivation for the novel-related reading and writing activities. This positive result confirms the advocacy of adopting a pedagogy of multiliteracies to keep abreast of and take advantage of digital technology (New London Group Citation1996; Thibaut and Curwood Citation2018). Adding to the existing literature, the present study provides some detailed and practical multimodal task designs illustrated with student samples, which might provide L2 teachers with some inspiration for literature teaching.

Conclusion

The main findings of this study can be summarised in the following four points. From students’ viewpoints, reading YAL enhanced their interest in the novel due to the relatable protagonists and engaging plot, which to a certain extent reduced the difficulty of understanding the text, in particular, slang and other colloquial expressions. Also importantly, the coming-of-age story was able to deepen students’ understanding of growth and related topics, for example, family love. From teachers’ point of view, the activities applied to the reading programme provide some insight into L2 literature teaching. First, integrating facilitating activities into novel reading, such as playing the movie adapted from the novel and reading others’ summaries and analyses could reduce L2 readers’ difficulty in understanding the text. Another function of such activities was providing students with sociocultural and literary background knowledge about the novel. Second, reading tasks were designed in various forms which approach the text from different angles. These tasks mainly addressed language issues and elicited students’ own interpretation of the text. In this sense, the four approaches of comprehensive model for L2 literature teaching (Bloemert et al. Citation2019) were integrated and interwoven into a tangible teaching system. This finding deviates from some studies carried out in similar contexts which placed emphasis on the language approach. This implies that even in exam-oriented contexts such as Chinese secondary schools, L2 literature can not only be integrated into the curriculum but can also be approached in a comprehensive manner rather than restricted to just a language-focus approach.

The pedagogic implications of this study can be formulated as two principles for L2 literature teaching, which emerge from our analysis of the activity design: (1) providing and eliciting multiple perspectives, and (2) integrating multimodal production into reading activities. Multiple perspectives include the historical, political and social context of the story, along with literary and linguistic elements embedded in the text. Perspectives also denote different readers’ interpretations of the text, including the L2 learner’s (through doing various post-reading activities), that of their peers (through sharing works on a social platform), of the teacher (through giving in-class instruction) and of competent others (through reading their summaries and analyses). The students interviewed also expressed their hope for more chances of voicing their viewpoints in classroom discussion. They also demonstrated preferences for more open-endedness in post-reading tasks. These findings indicate that while attaching importance to broadening students’ understanding by inviting others’ views, teachers should foreground students’ own perspectives. Regarding the principle of integrating multiple modalities in meaning-making and presenting perceptions, students expressed evident satisfaction and confirmed that this type of integration enhanced their understanding and deepened their learning (Meyer Citation2016). Moreover, utilising digital media and Internet resources to publish students’ works increased some students’ motivation for novel reading and L2 learning.

One major limitation of the study is the transferability of the findings. The student participants in this study were under less pressure in relation to exam preparation, compared with their peers of the same age group who need to take the Senior High School Entrance Examination. Therefore, it may not be possible to assume the same availability of time for L2 literature reading in the case of other students of the same age. However, the approaches that the teacher adopted and tested as effective with this group of students might well be applicable to other contexts with similar student needs and motives. Another factor that limits the transferability of the study is the fact that this was a small-scale case study, based on interviews with only three students. Future studies may want to test and improve the two principles for L2 literature teaching generated from this specific context in wider teaching practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adami, E. 2016. Introducing multimodality. In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society, eds. O. García, N. Flores and M. Spotti, 451–472. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alsup, J. 2010. Young Adult Literature and Adolescent Identity Across Cultures and Classrooms: Contexts for the Literary Lives of Teens. London: Routledge.

- Bassnett, S. and P. Grundy. 1993. Language Through Literature. London: Longman.

- Bland, J. 2013. Introduction. In Children's Literature in Second Language Education, eds. J. Bland and C. Lütge, 1–11. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bloemert, J., A. Paran, E. Jansen and W. van de Grift. 2019. Students’ perspective on the benefits of EFL literature education. The Language Learning Journal 47, no. 3: 371–384. doi:10.1080/09571736.2017.1298149.

- Bond, E. 2011. Literature and the Young Adult Reader. London: Pearson Education publishing as Allyn and Bacon.

- Braun, V. and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2: 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V. and V. Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE.

- Bucher, K. and K. Hinton. 2014. Young Adult Literature: Exploration, Evaluation and Appreciation, 3rd ed. New Jersey, NJ: Pearson.

- Bull, K. 2011. Connecting with texts: teacher candidates reading young adult literature. Theory Into Practice 50, no.3: 223–230. doi:10.1080/00405841.2011.584033.

- Burger, A. 2016. Teaching Stephen King. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Burke, G. and A. Cutter-Mackenzie. 2010. What’s there, what if, what then, and what can we do? An immersive and embodied experience of environment and place through children’s literature. Environmental Education Research 16, no. 3–4: 311–330. doi:10.1080/13504621003715361.

- Cadden, M. 2011. Genre as Nexus. In Handbook of Research on Children’s and Young Adult Literature, eds. S. Wolf, K. Coats, P. A. Enciso and C. Jenkins, 302–313. New York: Routledge.

- Carter, R. and M. N. Long. 1991. Teaching Literature. Harlow, Essex: Longman.

- Chambers, A. 1985. Booktalk: Occasional Writing on Literature and Children. London: Bodley.

- Coats, K. 2010. Young adult literature. In Handbook of Research on Children’s and Young Adult Literature, eds. S. Wolf, K. Coats, P. A. Enciso and C. Jenkins, 315–329. New York: Routledge.

- Coyle, D. and O. Meyer. 2021. Beyond CLIL: Pluriliteracies Teaching for Deeper Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Day, R. R. and J. Bamford. 1998. Extensive Reading in the Second Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Di Martino, E. 2019. The benefits of young adult literature in the Italian language class. NEMLA Italian Studies 41: 55–71.

- Fleming, M. 2007. The use and mis-use of competence frameworks and statements with particular attention to describing achievement in literature. In Towards a Common European Framework of Reference for Languages of School Education? Selected Conference Papers, ed. W. Martyniuk, 47–59. Poland: Waldemar Martyniuk.

- Flick, U. 2017. Triangulation. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 5th ed. 444–461. Los Angeles: Sage.

- García, O., L. Bartlett and J. Kleifgen. 2008. From biliteracy to pluriliteracies. In Handbook of Multilingualism and Multilingual Communication, eds. P. Auer and L. Wei, 207–228. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Glaus, M. 2014. Text complexity and young adult literature: establishing its place. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 57, no. 5: 407–416. doi:10.1002/jaal.255.

- Groenke, S. L. and L. Scherff. 2010. Teaching YA Lit Through Differentiated Instruction. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

- Hall, G. 2005. Literature in Language Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Hall, G. 2015. Recent developments in uses of literature in language teaching. In Literature and Language Learning in the EFL Classroom, eds. M. Teranishi, Y. Saito and K Wales, 13–25. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hilton, M. and M. Nikoleva. 2012. Contemporary Adolescent Literature and Culture: The Emergent Adult. London: Ashgate.

- Hunt, P. 2005. Understanding Children’s Literature, 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Johan, S. 2013. Free space: an extensive reading project in a Flemish school. In Children’s Literature in Second Language Education, eds. J. Bland and C. Lütge, 45–52. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Khatib, M., S. Rezaei and A. Derakhshan. 2011. Literature in EFL/ESL classroom. English Language Teaching 4, no. 1: 201–208. doi:10.5539/elt.v4n1p201.

- Krashen, S., S. Lee and C. Lao. 2018. Comprehensible and Compelling: The Causes and Effects of Free Voluntary Reading. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

- Kroger, J. 2000. Identity Development: Adolescence Through Adulthood. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lazar, G. 1993. Literature and Language Teaching: A Guide for Teachers and Trainers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, L. F. 2013. Taiwanese adolescents reading American young adult literature: a reader response study. In Children’s Literature in Second Language Education, eds. J. Bland and C. Lütge, 139–149. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Linneberg, M. S. and S. Korsgaard. 2019. Coding qualitative data: a synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal 19, no. 3: 259–270. doi:10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012.

- Littlewood, W. 2013. Developing a context-sensitive pedagogy for communication-oriented language teaching. English Teaching 68, no. 3: 3–25. doi:10.15858/engtea.68.3.201309.3.

- Macalister, J. and S. Webb. 2019. Can L1 children’s literature be used in the English language classroom? High Frequency Words in Writing for Children. Reading in a Foreign Language 31, no. 1: 62–80.

- Maley, A. 1989. Down from the pedestal: literature as resource. In Literature and the Learner: Methodological Approaches, eds. R. Carter, R. Walker and C. Brumfit, 1–9. Oxford: Modern English Publications and the British Council.

- McCallum, R. 2012. Ideologies of Identity in Adolescent Fiction: The Dialogic Construction of Subjectivity. London: Routledge.

- Meyer, O. 2016. Putting a pluriliteracies approach into practice. European Journal of Language Policy 8, no. 2: 235–242.

- Nagayar, S., A. Abd Aziz and M. N. Kanniah. 2015. Young adult literature and higher-order thinking skills: a confluence of young minds. International Journal of Language Education and Applied Linguistics 3: 51–61.

- Nation, I. S. P. and J. Macalister. 2010. Language Curriculum Design. Oxford: Routledge.

- New London Group. 1996. A pedagogy of multiliteracies: designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review 66: 60–92.

- Rapley, T. 2018. Doing Conversation, Discourse and Document Analysis, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Richardson, P. and J. Eccles. 2007. Rewards of reading: toward the development of possible selves and identities. International Journal of Educational Research 46, no. 6: 341–356. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2007.06.002.

- Rosenblatt, L. M. 1995/2016. Literature as Exploration. New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

- Sawyer, W. 1987. Literature and literacy: a review of research. Language Arts 64, no. 1: 33–39.

- Serafini, F. 2005. Voices in the park, voices in the classroom: readers responding to postmodern picture books. Reading, Research and Instruction 44, no. 3: 47–65.

- Short, M. H. and C. N. Candlin. 1986. Teaching study skills for English literature. In Literature and Language Teaching, eds. C. Brumfit and R. Carter, 89–109. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sun, X. 2021. Literature in secondary EFL class: case studies of four experienced teachers’ reading programmes in China. The Language Learning Journal, 1–16. doi:10.1080/09571736.2021.1958905.

- Thibaut, P. and J. S. Curwood. 2018. Multiliteracies in practice: integrating multimodal production across the curriculum. Theory Into Practice 57, no. 1: 48–55. doi:10.1080/00405841.2017.1392202.

- Trites, R. S. 1998. Disturbing the Universe: Power and Repression in Adolescent Literature. Iowa: University of Iowa Press.

- Trites, R. S. 2014. Literary Conceptualizations of Growth: Metaphors and Cognition in Adolescent Literature, vol. 2. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Tsang, A., A. Paran and W. W. F. Lau. 2020. The language and non-language benefits of literature in foreign language education: an exploratory study of learners’ views. Language Teaching Research, 1–22. doi:10.1177/1362168820972345.

- Van, T. T. M. 2009. The relevance of literary analysis to teaching literature in the EFL classroom. English Teaching Forum 3: 2–9.

- Wallace, C. 1992. Reading. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wiles, R., G. Crow, S. Heath and V. Charles. 2008. The management of confidentiality and anonymity in social research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 11, no. 5: 417–428. doi:10.1080/13645570701622231.

- Yan, Q. 2016. An experimental research on Original English Literary works as supplementary materials for extensive reading teaching in senior high school. Master’s diss., Hangzhou Normal University.

- Zhang, R. 2018. The study of extensive reading class in high school: using young adult fictions as reading materials. Master’s diss., Shanghai Normal University.