ABSTRACT

Today, higher education (HE) faces new challenges, such as incorporating consideration of diversity and inclusion into its operations. Such challenges, many of which are part of strategic institutional plans, offer teachers an opportunity to introduce new practices in the classroom. In this paper, we look at introducing language students to the task of audio description (AD) – that is, making visual content available to blind and visually impaired people by verbal means. We first present a framework for evaluating the learning that might derive from such an activity in the context of FL study, and then use this framework to evaluate a sequence of five tasks undertaken with Irish learners of Spanish. The tasks provided opportunities for the students to reflect on the communication needs of blind and visually impaired people and to understand how these could be addressed effectively in AD. The students practised AD in various contexts: both ‘improvised’ or ‘spontaneous’ AD as well as more carefully prepared AD, and undertaking AD in both the L1 (English) and the FL (Spanish). The pedagogic approach investigated here was inherently multidisciplinary and aimed to help learners become self-reflecting agents and mediators in their L1 and FL.

Introduction: affordances of translation in language teaching and learning

The first two decades of the twenty-first century have witnessed significant changes in the role of translation in language education, which take account of a number of social and educational needs. Recent research in this area relates in particular to the role of translation and social practices in educational settings, and studies have explored curriculum design (Floros Citation2021) and the development of plurilingual competence in high-complexity schools (González-Davies Citation2020). Other publications (e.g. Laviosa and González-Davies Citation2020) look at the development of applied translation studies within educational disciplines such as second language acquisition, bilingual education or language teaching methodologies. Carreres, Noriega-Sánchez, and Pintado Gutiérrez (Citation2021b) specifically discuss the new possibilities and challenges associated with the practice of translation in language learning, in the context of commitment to developing plurilingual learners and the implementation of plurilingual pedagogies. Embracing plurilingual pedagogies has allowed researchers and practitioners to reassess the role that translation plays in the FL classroom (Martínez Sierra Citation2021). Translation-related tasks are thus increasingly considered integral to FL pedagogies, offering possibilities for exploring students’ pluricultural and plurilingual repertoires while promoting ‘the dynamic nature of those practices and the fluidity of the boundaries between them’ (Carreres, Noriega-Sánchez, and Pintado Gutiérrez Citation2021a: 1).

One particular focus that is gradually gaining recognition in educational settings is the issue of accessibility in translation; in other words, the importance of encouraging skills not just of accurate (cross-linguistic) translation but also of inclusive communication where the student learns to act as a ‘mediator’, i.e. using strategies to transfer meaning in different languages and different modalities based on an understanding of the needs of the interlocutor.

Mediation and translation: a framework for introducing audio description into language education

Societal and cultural changes as well as pedagogic advances in the last two decades have led to changes in the practices of language teaching and learning, including greater attention to educational processes, the agency of the learner and the need to address communication gaps or breakdowns, rather than just seeing language proficiency as a body of knowledge and skills to be developed in isolation from its wider contexts of use. In the European context, the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe Citation2001), recently expanded in the CEFR Companion Volume (CEFRCV) (Council of Europe Citation2020), now reflects some of these societal and cultural changes through the development of ‘mediation’ as one of the four language activities, alongside reception, production and interaction.

Mediation is about to ‘mak[ing] communication possible between persons who are unable, for whatever reason, to communicate with each other directly’ (Council of Europe Citation2001: 14) and where the language user ‘act[s] as an intermediary between interlocutors who are unable to understand each other’ (87). Recognition of the importance of mediation in language education has developed since the early 2000s. The values attached to multi- and plurilingualism (such as recognising as cognitive tools the languages that students already speak or are familiar with, or promoting democratic values by acknowledging heritage languages in the learning process) have been particularly important in understanding and developing mediating skills and their role in building the communicative competence of learners. While the notion of mediation was clearly referred to in the 2001 CEFR, its role in FL teaching and learning remained rather limited (Pintado Gutiérrez Citation2019: 28). The Companion Volume, published by the Council of Europe in 2020, enhances the 2001 CEFR by extending the notion of mediation and providing detailed descriptors of what it entails.

Other advances that have been crucial to the development of the notion of mediation revolve around the social role of the learner, their learning trajectory and their personal development. These foci are now considered integral to the ‘interactive agency’ of learners/users in the CEFRCV (Council of Europe Citation2020: 90):

… the user/learner acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning, sometimes within the same language, sometimes across modalities (e.g. from spoken to signed or vice versa, in cross-modal communication) and sometimes from one language to another (cross-linguistic mediation).

A connection between FL, translation and mediation and a consolidated interest in the pedagogical value of translation in language education has emerged from recent advances in research and practice (Pintado Gutiérrez Citation2022); in fact, we would argue that mediation provides a space for maximising the pedagogical value of translation in the language learning curriculum. Policy making bodies such as the Council of Europe have demonstrated their commitment to advancing this area in their most recent 2022 publication on mediation: Enriching 21st Century Language Education: The CEFR Companion Volume, Examples from Practice, which offers case studies showcasing a range of practical applications for implementing the approaches specified in the CEFRCV (Council of Europe Citation2020). Specific indications of new directions in research and practice on translation, mediation and FL teaching and learning include works that focus on: plurilingual and pluricultural competences (Baños, Marzà, and Torralba Citation2021); the potential and challenges of integrating translation into language education (Carreres, Noriega-Sánchez, and Pintado Gutiérrez Citation2021b); proposals for a pedagogical framework for the implementation of an ‘Integrated Plurilingual Approach’ (IPA) to language learning (González-Davies and Soler Ortínez Citation2021); and the links between translation, plurilingual competence and heritage languages (Gasca Jiménez Citation2021).

The presentation of the construct of mediation in the 2001 CEFR initially led to the narrow assumption that it related mainly to translation and interpreting. This view was challenged by the 2020 CEFRCV whose wider perspective ‘reposition[s] the basic model [of the CEFR] within a more […] embracing view of [the] social agents’ learning trajectory and personal development’ (Coste and Cavalli Citation2015: 6). It explores mediation both as an activity and a set of strategies where the language learner conveys meaning, for example translating a written text, explaining data, facilitating collaborative interactions with peers, adapting language for a particular need or audience, or amplifying a dense text (Council of Europe Citation2020: 90). This revision of the construct has important implications for the type and the role of translation-related tasks that can be used in FL pedagogy.

A particularly relevant distinction is between translation as it is practised in professional training, and translation as it is used in other learning contexts (or TOLC) such as FL learning (González-Davies Citation2017). According to González-Davies, transfer skills (that is, those generic skills necessary to carry out a translation or effective ‘transfer’ of meaning such as noticing, observing, analysing, evaluating and creating) that promote language learning are at the core of translation competence, a notion that Baños, Marzà, and Torralba (Citation2021) deem critical in establishing connections between transfer skills and the mediation strategies included in the Companion Volume. The authors, who work in audio-visual translation (or AVT), make the case for AVT tasks in FL learning by arguing that such tasks can be used both as a means to improve plurilingual and pluricultural competence (PPC), and as an end in themselves in the acquisition of mediation skills. This means that students need to focus both on the AVT process and on the creation of an audio-visual product (such as a dubbed clip).

In this way, audio description (henceforth AD) as an AVT modality emerges as a particularly useful tool that has the potential to foster creative links between mediation and FL teaching. Defined as a ‘narrative technique’, AD translates the visual information of an audio-visual text into language, i.e. words. Whether in the context of film, television, theatre, opera or even exhibitions, AD facilitates the communication of information that blind or visually impaired audiences cannot receive by describing, as necessary, the most significant aspects of the visual information, typically in gaps in the production dialogue (Fryer Citation2016). The intersemiotic (i.e. transferring from non-verbal to verbal communication) and inter-modal (i.e. from visual to aural mode) nature of AD is very much in line with the mediation activities and mediation strategies presented in the Companion Volume. A successful AD is not one which perfectly communicates visual information in language; rather, it is one which is able to communicate key visual information verbally in a way that fits the constraints of the source material and thus supports communication with the end-user.

AD was not a major field within translation studies until very recently (Matamala and Orero Citation2016; Orero Citation2005; Perego Citation2012), but it represents a powerful task for language learning in that it allows for integrated development of the four language skills (written and oral production, as well as reading and aural comprehension) (see Ibáñez Moreno and Vermeulen Citation2014). When audio describing a clip, as such is the modality discussed in this paper, language learners, much like AD trainees, have to deconstruct and select the film elements that need to figure in the new text. In the creation of a script, which is central to any AD task, learners thus perform an intersemiotic and inter-modal process, as mentioned above (Benecke Citation2004; Bourne and Jiménez Citation2007). The AD process (looking at the source audio-visual material, deciding which audio-visual elements need to be explained, creating a script for the AD, and performing the AD within the constraints of the source material) particularly involves developing lexical and phraseological competence, enhances use of idiomatic formulae and accurate language (Ibáñez Moreno and Vermeulen Citation2013), and fosters stylistic richness by improving vocabulary acquisition (Calduch and Talaván Citation2018). AD is likely to have a positive impact on aural comprehension (Burger Citation2016), as well as on oral skills (Ibáñez Moreno and Vermeulen Citation2015) as it requires ‘good public speaking’ and attention to ‘successful communication’ (Lee Citation2008: 173).

In the same way as translators, language learners as AD describers can be considered ‘social mediators’ (Ibáñez Moreno and Vermeulen Citation2017). If the overall aim of FL teaching, as conceived in the CEFR, is to help the learner become an effective multilingual and intercultural agent, AD can be considered a useful FL learning task, as it combines linguistic and social skills based on real-life situations. From a pedagogical FL approach, AD can be used in oral or written activities that help learners develop mediation skills, in line with the CEFRCV, such as the reformulation of an existing text in order to communicate effectively, taking into considerations the needs of the audience.

The study

Context and purpose

The demand for AD is currently on the rise, partly due to EU legislation requiring its member states to provide a certain amount of accessible content (Audiovisual Media Services Directive of 2010 and the European Accessibility Act of 2019). However, the European AD landscape is still fragmented and countries are at different implementing stages. AD rates in Ireland, where the study took place, are especially low; for example, only 8% of content on the Irish public television channels, RTÉ1 and RTÉ2, is provided with AD (BAI Citation2019). Thus, a preliminary assumption behind this project was that Irish HE students would not be aware of AD and thus, introducing it into FL teaching might help future linguists and translators understand the communication issues as well as professional potential and relevance of audio-visual translation and media accessibility. Our student participants would therefore need to learn to think beyond ‘translation’ as a linguistic transfer between languages, and think rather of ‘mediation’ as an activity where they have to engage with a wider range of modalities to facilitate communication across different codes. The social and cultural aspects of the communication process involved in AD were also felt to offer students sufficient agency to (re)create optimal conditions for communication and cooperation between linguists and the visually impaired or blind, with students ultimately learning to resolve challenging communication issues and develop their plurilingual competences (relating to English and Spanish in this particular case).

The aim of this study was thus to explore the extent to which a sequence of pedagogic tasks focusing on AD as a mediation activity and requiring mediation strategies, would raise awareness of the challenges involved in this form of mediation. In the proposed pedagogic intervention, students were invited to act as plurilingual and pluricultural facilitators and to (1) reflect on the challenges of intersemiotic transfer both in their L1 and FL and to (2) develop their awareness of the barriers and accessibility challenges faced by those who are blind or visually impaired. More specifically, the study offered students an opportunity for hands-on experience with multimedia translation; it also allowed teacher-researchers an opportunity to put into practice new trends in language teaching and mediation, following the recommendations made by the CEFRCV; and to introduce an innovative pedagogical task that might help students become aware of issues to do with accessibility in communication, and to explore linguistic solutions aimed at addressing inequality.

The tasks included in this study were designed to simulate a context where communicative challenges arise between the non-blind and the blind or visually impaired; in other words, an opportunity for the majority of FL learners to engage with communication needs they might not have previously thought of. Helping students explore the difficulties involved in this specific process of intersemiotic communication and to find ways of overcoming obstacles were core goals, within the wider framework of encouraging tolerance and inclusivity in communication. We felt that having an awareness of AD would allow language learners to find a common space for communication with the blind community, using their language and intercultural resources in a highly targeted manner.

In order to understand how students experienced this pedagogic intervention, we explore their reflections guided by the following research questions (RQs):

To what extent does the pedagogic intervention activate understanding of ‘accessibility’ as a means to overcome barriers in communication?

Do FL learners perceive themselves as ‘mediators’ after the pedagogic intervention?

Does the students’ attention to their language skills vary during the different phases of the pedagogic intervention?

Participants

Participants were 21 final-year students studying for a degree in languages and translation at an Irish university. The module where this pedagogic intervention was introduced focused on advanced oral skills in the target foreign language, Spanish. All students had studied Spanish in a formal educational setting for between 3 and 7 years (university and/or secondary school). In this module, grounded in task-based activities, learners developed their communicative competence at CEFR B2 level. The module aimed to increase students’ accuracy and fluency through oral interactions, mediation tasks and aural comprehension activities. It focused on the process of communication and sociolinguistic norms.

Methodology

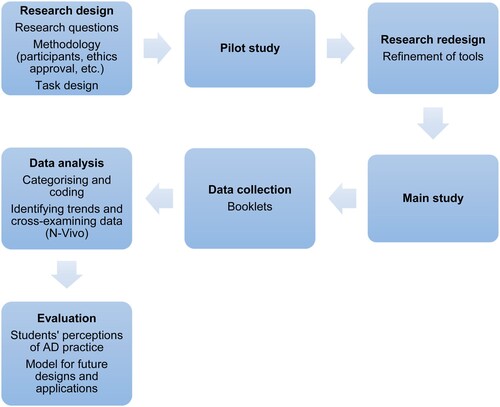

This case study of a pedagogic intervention is qualitative in nature as we undertake an in-depth analysis of students’ reports on their experiences (Stake Citation1995) as they completed different AD-related tasks. As shown in , the study process was divided into the following phases:

Research design. The goal of the study was to assess whether pedagogic interventions based on AD tasks have a place in higher education FL classrooms. All ethical implications were considered and approved by the University Research Ethics Committee. The pedagogic intervention was developed following the expanded presentation of mediation in the CEFRCV. AD was selected as a relevant practice for inclusion in the undergraduate curriculum, as students require higher intermediate language proficiency to carry out these activities and they have the potential to replicate relevant mediation roles in contemporary societies.

Pilot study. A preliminary study took place in 2018/2019 (see Sánchez Cuadrado et al. Citation2022) and served as a preview of how AD might work as a mediating task in the classroom. During the pilot study, observational records were gathered through field notes and audio recordings in order to collect students’ perceptions of the activities. Additionally, students were given a booklet with questions about the tasks so they could further elaborate on their reflections. Based on students’ perceptions of the tasks, an exploration as to how this approach could be delivered in the curriculum then followed. Students’ reflections revealed a lack of awareness of the communicative challenges that blind individuals face in relation to audio-visual support, which encouraged us, as leaders of this project, to liaise with the National Council for the Blind in Ireland (NCBI) and invite a blind person to take part in the subsequent project to help students with an introductory hands-on task.

Pedagogic intervention redesign. When analysing the data from the pilot study, the researchers also realised that the low quality of audio recordings of the students’ dialogues while working, which were used to collect their perceptions, made transcription problematic. For this reason, they explored ways of improving data collection tools. The booklets given to students to guide the reporting of their reflections were more comprehensive than those used in the pilot study and included clearer instructions and distinct objectives: they were divided in five sections, one corresponding to each activity, and each section contained an explanation of the activity and specific questions designed to get students to reflect on the challenges represented by each task and their own performance. The booklets also provided information on AD and how to implement it. The booklets meant that relevant data from the participants were collected in writing and did not require transcription. Finally, some of the clips used in the pilot study were changed to include more suitable ones.

Main study. The final intervention was implemented in the 2019/2020 academic year. Tasks were carried out in two one-hour sessions per week over a period of three weeks, in addition to independent homework. A blind person participated in the introductory task, where hands-on AD group work was followed by a general reflection about communicative needs and challenges facing blind or visually impaired people.

Data collection. Activities were completed in the classroom and the answers to the questions guiding the activities, along with students’ reflections of the different tasks, were collected in the booklets (mentioned above) distributed to participants at the start of the project.

Data analysis. The answers and reflections gathered in the booklets were analysed using N-Vivo software to identify themes and cross-examine the data. Different categories and subcategories (from the fields of linguistics, intersemiotics and mediation) were identified, providing a taxonomy which served as a guide for further interpretation of the collected data. This taxonomy (see ) was then used in the evaluation process.

Evaluation process. In this process, the data recorded from the students was reviewed. The results obtained indicated that the pedagogic intervention was effective and that the framework we developed could (a) advance the consolidation of AD pedagogic interventions in FL teaching and learning and (b) act as a model for future designs and applications.

Table 1. Framework for the analysis of intersemiotic tasks.

Developing a framework for the analysis of intersemiotic tasks

As explained above, in this article we propose AD as an innovative pedagogic practice in FL that explores communication as a mediation activity. Learners consider how to communicate across different codes in both their L1 and their FL, thus integrating mediation in FL teaching and learning, and AD as a modality of AVT translation. To guide our evaluation of the pedagogic intervention, we developed a framework based on three widely validated theoretical frameworks: the CEFR (Council of Europe Citation2001), the CEFRCV (Council of Europe Citation2020) and professional and pedagogical criteria specific to AD in AVT (as represented, for example, in Fryer Citation2016 and other technical documents referred to below). In developing the framework, we followed an inductive process; we first read and explored students’ answers and reflections in the booklets they completed as part of the activities. Based on this analysis, different categories and subcategories for consideration in the tasks were established, cross-referencing with our three source frameworks.

As shown in , our framework encapsulates a taxonomy that follows a general-to-specific pattern. The first column lists the three source theoretical frameworks. The second column shows the key categories for consideration (competence, activity, strategy) that derive from these sources, while the third and last column shows sub-categories used to interpret the collected data.

Communicative language competence in the CEFR was the starting point. In particular, linguistic competence in the CEFR refers to the students’ overall language use depending on their language resources (Council of Europe Citation2001). The specific elements that comprise it include vocabulary range, vocabulary control, grammatical accuracy and general linguistic range.

Mediation is conceptualised in the Companion Volume (Council of Europe Citation2020) as both (a) an activity and (b) a strategy. Mediation activities are defined as activities where the learner ‘is less concerned with [their] own needs, ideas or expression, than with those of the party or parties for whom [they are] mediating’ (Council of Europe Citation2020: 91), while mediation strategies ‘are concerned with strategies employed during the mediation process, rather than in preparation for it’ (Council of Europe Citation2020: 50 – our italics).

Under the heading of mediation activities, the tasks that were proposed as part of our pedagogic intervention involved mediating a text and mediating communication.

Mediating a text comprises passing on the content of a text to another person who cannot access it for reasons to do with linguistic, cultural, semantic or technical barriers. In our pedagogic intervention, this involved students in, for example, relaying information such that another student could draw a representation of it, and specifically, in ensuring that only relevant information was communicated (see Council of Europe Citation2020: 93). It also potentially involves using dictionaries (see Council of Europe Citation2020: 263) and other resources, as well as collaborating with other speakers, in order to clarify and select appropriate language for the task, which is likely to involve summarising and reformulating.

Mediating communication involves learning to facilitate shared space between culturally different interlocutors and acting as an intermediary in communication (Council of Europe Citation2020: 91). In our proposed tasks, students were confronted with the idea that language may not be the only challenge in achieving successful communication. In the context of mediating communication as part of an AD exercise, students had to work with three notions that are not included explicitly in the CEFR or the Companion Volume: accessibility (specifically here, enabling access to audiovisual products for blind or visually impaired people), awareness of such accessibility needs; and perception, that is, understanding how audiovisual elements might be perceived and, therefore, how they can be described.

Mediation strategies, according to the Companion Volume, are ‘the techniques employed to clarify meaning and facilitate understanding’ (Council of Europe Citation2020: 126). Adapting language – for example, as a way to ‘make difficult concepts (…) more comprehensible through paraphras[ing]’ (Council of Europe Citation2020: 263) – is a mediation strategy. While some of the strategies included in the Companion Volume, such as adapting language (e.g. paraphrasing; adapting speech/delivery) and streamlining a text (e.g. excluding what is not relevant for the audience), are relevant in the process of AD, we felt that a more comprehensive taxonomy was needed, one based on the principles of the Companion Volume but also taking into consideration Fryer’s (Citation2019) review of criteria for assessing AD, along with the information presented in the official British (Ofcom Citation2021) and Spanish (AENOR Citation2005) guidelines that regulate the practice of AD, as well as the studies conducted by Vercauteren (2007), Salway (2007) and Turner (1998) (cited in Marzà Citation2010). Our framework includes two specific areas of mediation strategies: (a) intersemiotic transfer and (b) intersemiotic translation.

Intersemiotic transfer includes elements or criteria related to Lee’s (Citation2008) concept of ‘delivery’ and the quality of speaking and successful communication. All of the AD elements below are significant in accomplishing mediation strategies:

timing, or synchronising the AD with the action and fitting it around the dialogue;

relevance, that is, the selection of significant information for understanding;

detail, refers to evaluation of which of the many possible aspects to keep or omit in the AD, depending on synchronisation and time constraints;

tone, that is, how the audio descriptor uses their voice to express different moods to describe and narrate the clip;

rhythm, referring to speech melody and emphasis;

speed of the narrator, or the pace of the narration.

Intersemiotic translation includes elements related to the visual information that should ideally be described and, in our framework, they are established using the following list of items, typically used in preparation of an AD:

character, or who takes part in the scene;

space, or where the action develops;

action, or what happens;

soundtrack, referring to sounds that can be useful in the understanding process

Other considerations relevant to AD that we include within the heading of intersemiotic translation following the students’ responses are:

genre, or style of the audiovisual product (documentary, cartoon film, etc.);

gist, or general meaning of the scene;

emotion, which can be rendered through choice of vocabulary or tone of delivery.

Task design and findings

In what follows, we present a sequence of the five tasks which were designed to help students become acquainted with different aspects of AD while developing their FL skills. For clarity, insights from our study on the students’ reflections on each of the intervention tasks are presented separately from Tasks 1 to 5.

Task 1. Research on audio description

In the first task, the teacher and the students researched and discussed AD and its (in)visibility in Ireland. Students were first asked to carry out individual research on the presence of AD in Irish television to obtain a sense of its overall context in contemporary Ireland. All students emphasised the low rate of audio-described TV products. In a follow-up to this task, students discussed what they thought of current AD services in Ireland. 70% reported that their perception was negative; that is, the services offered were insufficient. Only 20% expressed a positive perception, with 10% not making a judgement either way.

Task 2. A warm-up activity

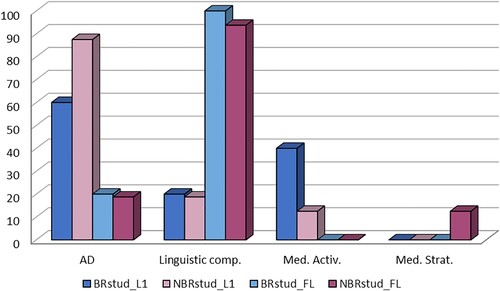

The second task was designed as a warm-up activity in which students worked in pairs and practised being descriptors for two different pictures, respectively. They were asked to undertake different roles, acting either as a blind person (‘blind role’ or BR) or non-blind person (‘non-blind role’ or NBR). First of all, the NBR described a picture in their L1 (English in this case) to the BR, who had not seen it and had to draw what was being described. In a second run of this activity, the students swapped roles, and this time, the NBR student had to describe a picture in their FL (Spanish).

A blind person from the NCBI was available to discuss students’ performance at the L1 stage and helped them understand what type of descriptions work for AD audiences. In the first place, students were asked which elements they considered relevant to understand the description when they used their L1. As shown in , 60% of BR and 87.5% of NBR students focussed on AD elements – i.e. space, character, detail. The second most frequent category revealed a difference between students playing BR and NBR: 40% of BR students identified the exercise as a mediation activity, while some NBR students tended to perceive the task as a communicative language skills exercise (18.75%).

Figure 2. Categories mentioned by students according to their role (BR/NBR) and language (L1/FL) in Task 2.

In the second run of the task, where students used their FL, communicative language competence became the main concern for both BR (100%) and NBR (93.75%) students, as they referred largely to the lack of vocabulary. ‘Spanish’ (the students’ FL) was the second most frequent word mentioned in relation to the second stage task where the BR students were trying to draw an image based only on their peer's description in Spanish.

Task 3. Hands-on practice 1

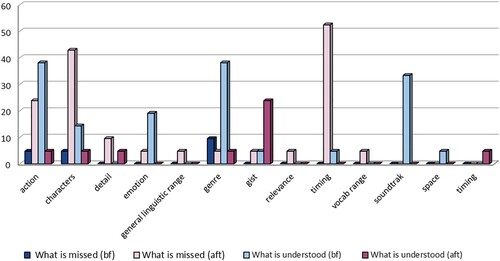

This task involved group work based on a clip from the animated film Frozen (Buck and Lee Citation2013). First, NBR students watched the clip (visual and audio information) while BR students just listened to it. The audio information comprised the soundtrack and paralinguistic ‘dialogue’ (no words). In pairs, the students then reflected on the extent to which the clip could be understood in just its audio form. In the second stage of the activity, the NBR students improvised an AD for the clip in their L1, and subsequently, both BR and NBR students discussed what the BR students had understood before and after listening to the AD (see ).

Based on feedback on the first stage of the task (listening to just the audio track of the clip), the BR students appeared not to have any deep understanding of what the clip was about: for example, only 38% reported that they had even understood the genre of the clip (an animated cartoon film), and the action that was taking place (running, fighting), and only 33% recognised the style of the (Disney) soundtrack. Initially, only 5% of the BR students got the overall gist of the clip. However, after the AD provided by their NBR peers, 24% of the BR students reported that their overall understanding of the clip had improved. The most prominent issues that the BR students mentioned as needing improvement related to timing (52%), characters (43%) and action (24%).

Task 4. Observation and assessment

In this task, students analysed two professional ADs. As in the previous task, the clips were animated cartoons. Students were asked to observe and assess the clips and to comment on the features of the ADs that they found most interesting (mediation, intersemiotic transfer, intersemiotic translation). A group discussion followed. The categories that appeared most frequently in the students’ assessments were intersemiotic transfer (95%), mediation activity (71%) and intersemiotic translation (67%). Among the various subcategories, tone was considered key (76%), and timing and effective transfer (both 67%) were also salient.

Task 5. Hands-on practice 2

Task 5 followed the same structure as Task 3, but in this case, the AD task was carried out in the students’ FL (Spanish). In our analysis, we draw only on the BR students’ comments rather than those from the full cohort (i.e. including those students who presented an AD). The clip used in this task was a cartoon, and while there were no aural elements that could be easily identified (as happened with the archetypal Disney soundtrack in the clip used in Task 3) the dialogues helped the BR students to follow the storyline, at least to some extent. After listening to the clip, all BR students reported getting the gist of what was happening, in contrast to their performance in Task 3. An AD was then provided by the NBR students, and the BR students reported on the elements that they had understood most effectively and the information that could have been improved. According to 60% of the BR students, their peer's AD brought a better sense of relevance (i.e. chose the most important information) as part of the intersemiotic transfer, and 20% reported an improvement in other elements (understanding of characters, details, timing, vocabulary range, vocabulary control and gist). On the other hand, 60% of the BR students also reported that they felt their peers could have provided more details in their AD. 40% also felt there needed to be more attention to timing and relevance. Finally, 20% felt that insufficient information was provided about the characters.

In a final stage of Task 5, the full cohort reflected on two aspects: (a) what type of tools (e.g. different dictionaries, on-line repositories, etc.) were needed to prepare a good AD; and (b) the role of audio descriptors and what the main skills of a good professional should be. 38% reported that they felt they needed to work with specific tools to improve vocabulary, 33% mentioned the importance of learning a wide range of vocabulary and 29% said that a dictionary was necessary to prepare a good script for the AD. The data revealed that all students identified AD as a mediation activity rather than an activity focusing solely on language or linguistic aspects. This was evident in the fact that words such as ‘intermediary’ (76.2%) and ‘awareness’ (66.7%) appeared most frequently in the students’ answers.

Discussion

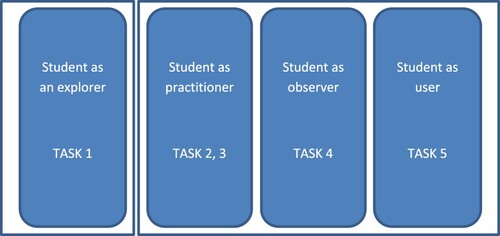

The discussion that follows explores the different phases of the pedagogic intervention, focusing in particular on the various roles played by the students: researcher, practitioner, observer and AD user. This development of roles from Tasks 1 to 5 is shown in .

The student as explorer – Task 1

The first task was key to contextualising mediation in Ireland. The poor presence of AD and the rather unpromising future where an increase of as little as 2% by 2021 was agreed (BAI Citation2019) led students to realise the low rate of AD and the subsequent poor awareness of AD services and products among the population. In fact, many students acknowledged that they themselves had not been aware of AD on public TV, and only a few knew that AD was available on streaming platforms. This general lack of awareness makes pedagogical interventions such as the one presented here all the more valuable, as they can raise students’ awareness of this particular social need. They also prompt students to realise the importance of the function of mediators by drawing attention to AD, an area in which linguists or translators may want to specialise. Ultimately, it was important for students to identify AD as a mediation service where the descriptor makes communication possible for blind or visually impaired individuals. Furthermore, the results confirm the suitability of our pedagogic intervention for developing transversal skills such as conducting research and raising awareness, and for reflecting on the relevance of mediation.

The student as practitioner – Tasks 2 and 3

Task 2, which introduced students to AD-related activities, was important in getting students to experience a new challenge. Students first described a drawing – a rich intersemiotic exercise – and then subsequently worked with video clips. Both the pictures and audiovisual texts, alongside the students’ different roles in undertaking the task, led them to focus on some of the most relevant (and challenging) elements when audio describing audiovisual texts, such as conveying the gist, and adjusting timing and relevance.

The students’ concerns at this stage varied depending on which language they were using. When using their L1, they concentrated on the transfer process (that is, elements related to implementing the AD, such as timing, action, speed, detail, character, etc.). When they used their FL, they focused on the challenge of coming up with an adequate AD in terms of quality, reflecting their perceived lack of vocabulary and generally, their limited linguistic range. When audio describing, the students were in a situation where they had to use language purposefully; as some of them reported, they had to adapt their language carefully, either because they might not know specific vocabulary, or because they might need to condense the description to fit in the time available in the source material.

The presence of a blind person when the students were undertaking Task 2 helped them realise how to avoid communication breakdowns by optimising their description using relevant information. It also brought about a fruitful debate on the need to address specific inequalities in society, the difficulty of carrying out these tasks, what AD services might be missing, and non-blind citizens’ very limited awareness of the existing barriers in communication for blind and visually impaired people.

Task 3 involved students acting as practitioners, functioning in both BR/NBR roles. In the pre-AD phase, those BR students familiar with the soundtrack of the clip – in this case, a Disney production – found it easier to identify the genre and subsequently establish general connections between the genre, soundtrack and action that was happening (since animated films typically involve plenty of action or movement, as was the case with the clip used). However, most students did not understand the overall clip.

After students’ first reflections, it became clear that, as stated earlier in this article, the proposal had the potential to link FL teaching to mediation. A number of studies had already showed how AD – as an AVT mode – was useful to developing specific language skills. However, in Task 3 students focused on aspects related to mediation, as conceived in the revision of the 2020 CEFRCV, which highlights mediation strategies such as explaining data or facilitating collaborative interactions with peers. Thus, after the first AD was provided, a larger number of BR students reported that, while they understood more or less what was happening in the clip, they required more accurate information about elements relating to the characters involved, the specific actions that took place, and how the information was distributed (timing). Therefore, BR students demanded elements classified as intersemiotic transfer and intersemiotic translation, overlooking specific items related to their linguistic competence. Furthermore, the fact that students who were not specialising as audio descriptors, focused on aspects related to AD procedures, endorses our framework as a proposal devoted to promote an educational space of translation-related tasks in the FL curricula as authors as Floros (Citation2021) or Pintado Gutiérrez (Citation2022) demand.

The student as observer – Task 4

In Task 4, students acted as observers and reflected on AD products. When acting as observers of professional products, they drew particular attention to the nature of AD as an intersemiotic transfer and mediation activity, and to specific elements of intersemiotic translation. Focusing on these elements seems natural, given that students were analysing two professional products and they were already familiar with how AD works based on their experience as practitioners. Students praised the AD products, highlighting the importance of the features that ensure an effective transfer and the relevance of an effective intersemiotic transfer in an AD. These results can also be related to González-Davies’ reference to transfer skills (Citation2020) and proved the students’ capacity of observing, analysing and evaluating those elements required to carry out an effective transfer of meaning. Task 4 demonstrates that linguistic competence came to play a secondary role and students’ attention was focused mainly on two features Lee (Citation2008) considers necessary to accomplish a good delivery: tone, (referred to for the first time in this set of tasks), and timing (a recurrent issue throughout the entire pedagogic intervention).

Finally, just as Baños, Marzà, and Torralba (Citation2021) identified connections between transfer skills related to translation competence and the mediation strategies included in the CEFR in different AVT modes (dubbing and subtitling), this task makes clear that transfer skills can also be developed while focusing on intersemiotic transfer and intersemiotic translation.

The student as user – Task 5

In Task 5, BR students acted as end users of an AD provided by their NBR peers. BR learners assessed this AD and explained which elements were helpful and which elements were lacking. This exercise, which was the final task, provided an opportunity to observe progress on language use and AD skills. In fact, this task, which was the most similar to a real audio description exercise, confirmed the suitability of the pedagogic intervention in order to broaden the use of mediation in FL teaching and learning, as various authors suggest (Carreres, Noriega-Sánchez, and Pintado Gutiérrez Citation2021a; Pintado Gutiérrez Citation2019).

In preparation for the AD product, BR students emphasised the importance of words and wording, in terms of both accuracy (or control) and range, as noted in the Companion Volume (Council of Europe Citation2020). After the AD provided by the NBR students, a majority of the BR students reported an improvement in information related to intersemiotic transfer and intersemiotic translation, such as characters, details, timing, vocabulary range, vocabulary control and gist. Although there was a clear improvement in students’ work as audio descriptors between Tasks 3 and 5, the use of the FL in Task 5 highlighted students’ linguistic limitations (also mentioned in the second phase of Task 2). Overall, however, it was clear that the NBR students focused much more on their role as mediation agents in Task 5 than in the earlier task.

Conclusions

The study presented here provides an evaluation of a sequence of pedagogic tasks that aimed to further language students’ understanding of accessibility in communication through audiovisual translation. The overall conclusion is that the intervention was positive, in that it provided the students with an innovative practice that indeed activated their awareness of accessibility and brought them the opportunity to trial different approaches to AD. Students engaged with all the tasks and, as we have attempted to demonstrate above, came to act as mediators, developing greater insight into their mediating role. To start with, there was a natural shift from an overwhelming consensus that AD (public) services remain insufficient in Ireland to the realisation that (audio)describing is no easy task. Working in the L1 language was unsurprisingly easier than doing so in the students’ L2 but the students recognised that even in their L1, AD had its own non-linguistic challenges. In subsequent tasks where the students operated in L2 only, the data suggested that they move away from simple language concerns to a better understanding of how to use their L2 to produce an effective audio description.

A further educational aspect that enhanced the students’ experience was the collaborative nature of all the tasks where students alternated different roles in the learning cycle (exploring, practising, observing and assessing their own final AD product) while developing a number of skills as either blind/non-blind users, thus allowing them to acquire relevant practice and to become aware of their progress through reflection. Students learned to use both the contextual cues and the information needed to create an appropriate AD script.

This case study suggests that the tasks implemented were suitable for developing students’ generic transversal skills such as researching, gaining awareness of how to use effective communication in challenging situations, and developing their role as mediators in L1 and FL in relation to the communication needs of blind and visually impaired individuals. Naturally, the proposed sequence of tasks we have reviewed can be adapted to suit a variety of learning contexts and tasks depending on the learning aims. We also recognise, from an FL teaching and learning perspective, that it is important to support learners in accessing the range of vocabulary and structures in the FL which students might need to undertake a successful AD further to the AD techniques.

We hope that the framework we propose and our exploratory study will serve both as a basis for the design of pedagogic interventions through a set of tasks, and a tool to guide the students in their process to familiarise themselves with mediation exercises and to assess their final AD product within an FL teaching and learning context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- AENOR (Agencia Española de Normalización). 2005. Audiodescripción para personas con discapacidad visual. Requisitos para la audiodescripción y elaboración de audioguías (UNE 153020:2005).

- BAI (Broadcasting Authority of Ireland). 2019. BAI access rules. https://www.bai.ie/en/media/sites/2/dlm_uploads/2019/01/AccessRules_2019_vFinal.pdf.

- Baños, R., A. Marzà and G. Torralba. 2021. Promoting plurilingual and pluricultural competence in language learning through audiovisual translation. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 7, no. 1: 65–85. http://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00063.ban.

- Benecke, B. 2004. Audio-description. META 49, no. 1: 78–80. https://doi.org/10.7202/009022ar.

- Bourne, J. and C. Jiménez. 2007. From the visual to the verbal in two languages: a contrastive analysis of the audio description of The Hours in English and Spanish. In Media for All. Subtitling for the Deaf, Audio Description, and Sign Languages, ed. J. Díaz-Cintas, P. Orero and A. Remael, 175–88. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Buck, C. and J. Lee (Directors). 2013. Frozen. Los Angeles: Walt Disney Animation Studios.

- Burger, G. 2016. Audiodeskriptionen anfertigen – ein neues Verfahren für die Arbeit mit Filmen. Info DaF-Informationen Deutsch als Fremdsprache 1: 44–54. doi:10.1515/infodaf-2016-0105

- Calduch, C. and N. Talaván. 2018. Traducción audiovisual y aprendizaje del español como L2: el uso de la audiodescripción. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 4, no. 2: 168–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2017.1407173.

- Carreres, Á., M. Noriega-Sánchez and L. Pintado Gutiérrez. 2021a. Introduction: translation and plurilingual approaches to language teaching and learning. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 7, no. 1: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00066.int.

- Carreres, Á., M. Noriega-Sánchez and L. Pintado Gutiérrez, ed. 2021b. Translation and plurilingual approaches to language teaching and learning: challenges and possibilities. Special issue. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 7, no. 1: 1–131.

- Coste, D. and M. Cavalli. 2015. Education, Mobility, Otherness. The Mediation Functions of Schools. Strasbourg: Language Policy Unit, Council of Europe.

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Floros, G. 2021. Pedagogical translation in school curriculum design. In The Oxford Handbook of Translation and Social Practices, ed. M. Ji and S. Laviosa, 281–99. London: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190067205.013.20

- Fryer, L. 2016. An Introduction to Audio Description. A Practical Guide. London: Routledge.

- Fryer, L. 2019. Quality assessment in audio description: lessons learned from interpreting. In Quality Assurance and Assessment Practices in Translation and Interpreting, ed. E. Huertas-Barros, S. Vandepitte and E. Iglesias-Fernández, 155–77. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Gasca Jiménez, L. 2021. Traducción, Competencia Plurilingüe y Español como Lengua de Herencia (ELH). London: Routledge.

- González-Davies, M. 2017. The use of translation in an integrated plurilingual approach to language learning: teacher strategies and best practices. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 4, no. 2: 124–35. doi:10.1080/23247797.2017.1407168

- González-Davies, M. 2020. Developing mediation competence through translation. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Education, ed. S. Laviosa and M. González-Davies, 434–50. London: Routledge.

- González-Davies, M. and D. Soler Ortínez. 2021. Use of translation and plurilingual practices in language learning: a formative intervention model. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts 7, no. 1: 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00059.gon.

- Ibáñez Moreno, A. and A. Vermeulen. 2013. Audio description as a tool to improve lexical and phraseological competence in foreign language learning. In Translation in Language Teaching and Assessment, ed. G. Floros and D. Tsigari, 41–64. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Ibáñez Moreno, A. and A. Vermeulen. 2014. La audiodescripción como recurso didáctico en el aula de ELE para promover el desarrollo integrado de competencias. In New Directions on Hispanic Linguistics, ed. R. Orozco, 263–92. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Ibáñez Moreno, A. and A. Vermeulen. 2015. Profiling a MALL app for English oral practice: a case study. Journal of Universal Computer Science 21, no. 10: 1339–61.

- Ibáñez Moreno, A. and A. Vermeulen. 2017. The ARDELE project: audio description as a didactic tool to improve (meta)linguistic competence in foreign language teaching and learning. In Fast-forwarding with Audiovisual Translation, ed. J. Díaz Cintas and K. Nikolic, 195–211. Bristol: Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

- Laviosa, S. and M. González-Davies, ed. 2020. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Education. London: Routledge.

- Lee, J. 2008. Rating scales for interpreting performance assessment. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2, no. 2: 165–84. doi:10.1080/1750399X.2008.10798772.

- Martínez Sierra, J.J., ed. 2021. Multilingualism, Translation and Language Teaching. The PluriTAV Project. Valencia: Tirant Humanidades

- Marzà, A. 2010. Evaluation criteria and film narrative. A frame to teaching relevance in audio description. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 18, no. 3: 143–53. http://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2010.485682.

- Matamala, A. and P. Orero, ed. 2016. Researching Audio Description: New Approaches. London: Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56917-2

- Ofcom. 2021. Ofcom’s guidelines on the provision of television access services. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/212776/provision-of-tv-access-services-guidelines.pdf.

- Orero, P. 2005. La inclusión de la accesibilidad en comunicación audiovisual dentro de los estudios de traducción audiovisual. Quaderns de Traducció 12: 173–85.

- Perego, E. 2012. Emerging topics in translation: Audio description. Trieste: EUT.

- Pintado Gutiérrez, L. 2019. Mapping translation in foreign language teaching: demystifying the construct. In Translation and Language Teaching. Continuing the Dialogue, ed. M. Koletnik and N. Froeliger, 23–38. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Pintado Gutiérrez, L. 2020. Inverse translation and the language student: a case study. Language Learning in Higher Education 10, no. 1: 171–93. doi:10.1515/cercles-2020-2013

- Pintado Gutiérrez, L. 2022. Current practices in translation and L2 learning in higher education: lessons learned. L2 Journal 13, no. 2: 32–50. doi:10.5070/L214251728

- Sánchez Cuadrado, A., J. Cruz, S. Lorenzo-Zamorano, M. Navarrete and L. Pintado Gutiérrez. 2022. Role of contextual factors in the implementation of mediation. Descriptors with higher education language learners. In Enriching 21st Century Language Education: The CEFR Companion Volume, Examples from Practice, ed. B. North, E. Piccardo, T. Goodier, D. Fasoglio, R. Margonis and B. Rüschoff, 57–67. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.