ABSTRACT

Unequal access to language learning resources has been exacerbated by the global expansion of English private tutoring (EPT). Despite its popularity, no study has examined the implications of EPT during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this mixed-methods study explored the nature and effectiveness of EPT that first-year Kazakhstani undergraduate students had experienced over the previous 12 months during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was informed by Benson’s (2011) model of language learning beyond the classroom. Data were collected through a close-ended questionnaire and semi-structured online interviews. The study found that 318 out of 750 (42.4%) had experienced EPT, and 64% of respondents had received face-to-face EPT although it was considered a health risk during the pandemic. All the interviewees perceived EPT sessions as an encouraging environment for coaching towards the university entrance examination and expanding their knowledge. They attributed this mainly to the individual attention they obtained from their tutors, which was lacking in online classes with their English teachers due to teachers’ indifferent attitude to students’ questions and the limited duration of video conferencing sessions. The participants acted agentively by evaluating the advantages and drawbacks of online EPT. Pedagogical implications and areas for further research are suggested.

1. Introduction

A steadily growing body of education literature has been systematically focusing on schools and schooling. However, insufficient attention seems to be paid to the widespread phenomenon of private tutoring (PT), which is ‘inevitable, universal, and will likely continue to intensify into the foreseeable future’ (Baker Citation2020: 311, italics in original). Shadow education is the academic term for PT, which operates alongside regular schooling and, to some extent, copies its curriculum (Bray and Hajar Citation2023). PT commonly refers to the ‘tutoring in academic subjects provided on a fee-charging basis by companies, teachers undertaking such work in addition to their regular duties, and informal suppliers such as university students’ (Zhang and Bray Citation2021: 43). It can take various forms – one-to-one, small-group, live or video-recorded lectures and online. Yung and Hajar (Citation2023) underline that English private tutoring (EPT) is still in its infancy despite its popularity and implications for the nurturing of new generations, economic growth, the operation of formal education systems, and cultural and social development.

Related concerns are the way neoliberalism promotes English as an essential artefact for fostering the ideologies of individualism and competition in both educational and non-educational settings, such as the workplace (Manan and Hajar Citation2022). Neoliberalism is a political-economic ideology advocating state deregulation, the privatisation of diverse educational services, and competitive market policies with limited state interventions and social security (Block, Gray and Holborow Citation2013; Manan and Hajar Citation2022). In many education systems worldwide, neoliberal doctrines acquire practical expression by asserting that governments should not be viewed as the sole source to finance and provide education (Addi-Raccah Citation2019). This has prompted both the marketisation of education services and the family’s responsibility for the educational outcomes of their children (Holloway and Kirby Citation2020). Consequently, parents tend to believe that doing well academically is the clearest path towards a better life and, therefore, they strive to purchase a competitive advantage for their children by sending them to PT, usually in addition to formal education. The English language is one of the most popular subjects in PT, particularly in contexts where English is learnt as an additional language (Yung and Hajar Citation2023). However, it remains a relatively under-researched area.

The employment of private tutors largely takes place when children approach significant transition points in the standard education system. Related to this, PT can be ‘a major vehicle for maintaining and exacerbating social inequalities’, because some families cannot afford PT or only of a lower quality (Bray Citation2021: xi). Hence, some children may not become fully acquainted with the content or nature of such high-stakes tests. The issue of social inequality associated with PT intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. As Luo and Chan (Citation2022) remark, the global pandemic has raised significant concerns about how PT amplifies the education attainment gap because more parents – especially prosperous ones – used their own resources by hiring private tutors for their children when the COVID-19 pandemic closed schools and thus their face-to-face instruction. Parents’ dissatisfaction with disrupted schooling contributed to legitimising teachers’ involvement in PT and driving more serving teachers to become tutors (Zhang Citation2023). Related to this, increasing volumes of PT have begun to be delivered over the Internet, as a response to the need for social distancing caused by COVID-19 (Bray Citation2022). In China, for instance, Zhang (Citation2023: 61) points out that during the COVID-19 crisis many online tutoring companies such as China 61 Baidu, Tencent and Bytedance expanded their shares in the online tutoring market.

With the above in mind, the mixed-method study reported in this paper focuses on the nature and effectiveness of fee-charging English private tutoring (EPT) that first-year Kazakhstani undergraduate students had experienced over the previous 12 months (during the COVID pandemic). The focus of much of their EPT was the Unified National Test (UNT), a high-level test for entrance to most universities in Kazakhstan. This examination is likely to be highly tutored, especially because the state grant for entrance to higher education in Kazakhstan is awarded according to UNT results. The UNT has two parts: the first consists of tests on the history of Kazakhstan, mathematical literacy, and reading literacy; the second examines the two specialist subjects of the applicant’s choice, one of which can be English (Chankseliani, Qoraboyev, and Gimranova Citation2020).

2. Sociolinguistic profile of Kazakhstan and the implementation of emergency remote teaching and learning (ERT&L)

Kazakhstan, the context of the present study, is a multilingual and multicultural country with over 130 ethnic groups and languages. Kazakhstan is regarded as the first country in Central Asia to actively develop a trilingual education policy of teaching different subjects through Kazakh, Russian, and English in secondary schools and higher education institutions (Hajar and Ait Si Mhamed Citation2021). Kazakh has been made the official state language, Russian the language of inter-ethnic communication and the regional language, and English the language of successful integration into the global economy. The emphasis on English as L3 (after Kazakh and Russian) in Kazakhstan, as Hajar and Ait Si Mhamed (2021) point out, is driven by two assumptions: that English serves as a universal lingua franca and that English language competency is essential for individuals to secure good economic returns for their labour and national economic development.

School education in Kazakhstan is divided into primary (grades 1–4), lower secondary (grades 5–8) and upper secondary education (grades 9–11). Grade 11 is a critical stage in the Kazakhstan education system because at the end, most students take a special academic entrance exam called the UNT to attend one of the state universities. Thus, parents who wish their children to pass this high-stakes examination may coach their children themselves, and/or hire private tutors, mainly because many mainstream teachers have difficulty covering the whole curriculum during school hours, and COVID-19 exacerbated this problem. Bokayev et al. (Citation2021) indicate that 131 universities, 801 colleges and 7398 schools in Kazakhstan switched to ERT&L during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

There are only a few studies on ERT&L due to the global pandemic in Kazakhstan (e.g. Bokayev et al. Citation2021; Durrani et al. Citation2021; Hajar and Manan Citation2022). Hajar and Manan (Citation2022), for instance, qualitatively explored the ERT&L experiences of a group of primary school students (aged 10–11) and their female English teachers in Kazakhstan. The study found that most mainstream schoolteachers were late to subscribe to online platforms and did not receive appropriate training on how to use them. However, the teachers demonstrated their agency by taking action to choose and use the most appropriate platforms to fulfil their online English teaching responsibilities effectively. The students were critical of their English language teachers’ practices, particularly because of the scarcity of co-operative activities, the overuse of WhatsApp, and delays in responding to inquiries. The study also found that EPT was one of the strategies used by some parents to free themselves from the burden of tracking their children’s progress and/or helping them obtain additional support, especially since many parents were not competent in English language.

3. Review of research into fee-charging private tutoring in Kazakhstan and beyond

Although the phenomenon of PT has been documented since the 1940s–1960s in several countries such as Egypt, Japan, Kuwait, India and South Korea, it has been under-researched, mainly because the policy makers in many countries have adopted a laissez-faire stance towards the PT market, considering students’ out-of-classroom experiences outside their area of responsibility, while some tutors and families are reluctant to provide data about PT because it is viewed as an illegal form of education (Hajar and Karakus Citation2022). Bray (Citation2022) points out that the forces of globalisation, neoliberalism, and social competition have caused an expansion in PT, and there has been a worldwide increase in PT research in Africa (Bray Citation2021), Central Asia (Silova Citation2009), East Asia (Zhang and Yamato Citation2018), Europe (Bray Citation2011), North America (Aurini, Davies, and Dierkes Citation2013), South America (Lasekan, Moraga, and Galvez Citation2019) and the Middle East (Bray and Hajar Citation2023).

In Kazakhstan, the context of the present study, few empirical research studies on PT exist (e.g. Hajar and Abenova Citation2021; Hajar and Karakus Citation2023; Hajar, Sagintayeva, and Izekenova Citation2022; Kalikova and Rakhimzhanova Citation2009) and none have focused on EPT in particular. Kalikova and Rakhimzhanova (Citation2009), for instance, collected quantitative data from 1004 first-year students, then interviewed 37 university instructors from six universities in two Kazakhstan cities, Almaty and Shymkent. The authors found that 64.8% of students had sought PT in the previous 12 months, principally to prepare for university entrance examinations (42%). The other reasons participants mentioned for attending PT were to improve their understanding of school subjects (31%), to fill knowledge gaps (26%) and to compensate for the poor quality of education in public schools (11%). 84.6% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that students who had PT had a greater chance of winning a place at university than students of equal ability who did not attend PT. The participants had PT mainly in mathematics (67%), history (36%), physics (36%), the Kazakh language and literature (17%) and English (14%). The percentages in the findings may be influenced by the fact that mathematics, history and the state language, Kazakh, are compulsory subjects in the UNT, the high-level entry test for most Kazakhstan universities, whereas English is an optional subject in this test. Kalikova and Rakhimzhanova (Citation2009: 98) concluded their study by suggesting that the centralised examination system in Kazakhstan had made access to university ‘more competitive, and the private tutoring market has been quick to take advantage of this situation’.

Unlike Kalikova and Rakhimzhanova (Citation2009), most of the respondents in Hajar and Abenova’s (Citation2021) study in Astana had PT in English language and Mathematics because they had applied to a highly selective university in Kazakhstan, where entrance examination success depended on high-level proficiency in English and mathematical skills. In terms of PT intensity, Hajar and Abenova (Citation2021) reported that 86 out of 144 participants (60%) had sought PT, mainly to secure a place at a highly selective university in Kazakhstan. Concerning the modes of PT delivery, 50% of the participants took PT lessons in groups, 27% reported having received both individual and group tuition, and 16% had only had individual PT. This finding concurs with Silova’s (Citation2009), who indicated that over 40% of students in Central Asia had PT in groups because it is more affordable than individual tutoring. However, only 5 participants (7%) had received online tutoring.

Although the above studies give some insights into the intensity, reasons for the prevalence of face-to-face PT in Kazakhstan and its impact on students’ access to universities, none of these studies has focused on EPT in particular and student voices and critical reflections on their PT/EPT experiences – especially online tutoring during the COVID-19 – in Kazakhstan remain largely absent. Therefore, the mixed-methods study reported in this paper aims to address this major lacuna by reporting the EPT experiences of 318 first-year university students from two highly selective universities in Kazakhstan over 12 months, i.e. during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Theoretical framework

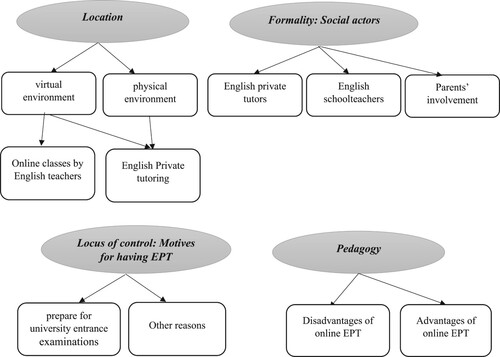

Without understanding individuals’ out-of-class learning experiences including EPT, language researchers and policymakers ‘would only see a partial picture of [students’] real English-learning experiences and proficiency’ (Lee Citation2010: 70) and miss ‘alternative perspectives on the meaning of, and social and cognitive processes involved in, language learning and teaching’ (Benson and Reinders Citation2011: 1). This study is guided by Benson’s (Citation2011) theoretical model because it is one of the few theoretical models that seek to understand the less well-charted terrain of learners’ language learning experiences beyond the classroom. It covers four dimensions: location, formality, locus of control and pedagogy. Location refers to the place in which a language learning activity occurs, which can include both physical and virtual environments. In this study, EPT sessions can take place face-to-face and/or online, using different online platforms, such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. The second dimension, formality, here refers to the practices of both formal and informal actors (e.g. English language teachers, peers, English private tutors, and family members) that contribute to or hinder learners’ language learning and development. The dimension of locus of control in this study, centres on how far learners’ goals when attending EPT are influenced or controlled by significant others such as their English language tutors and parents (i.e. the goal of ‘grade achievement’), or the extent to which they feel in control of their own language learning and development; i.e. the extent to which their learning goals for having EPT are regulated by themselves and may be associated with achieving their own personal, academic and/or vocational purposes (i.e. EPT can help them work/study abroad and mingle with people from different nationalities). The fourth dimension, pedagogy, in this study mainly pertains to students’ evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of EPT.

5. Data and methodology

The present study adopts an explanatory sequential mixed-method research design. In this research design, the qualitative data collection process follows the quantitative one in order to allow the researchers to gain better understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Creswell and Clark Citation2017). Giving students an opportunity to reflect on their experiences of EPT is at the heart of this study. Informed by Benson’s (Citation2011) four-dimensional model of out-of-class language learning, this article addresses the following question: how were the four dimensions (location, formality, locus of control and pedagogy) interpreted in the participants’ EPT experiences?

The data were collected online between August and December 2021, from first-year undergraduate students in the first semester of their undergraduate studies at two highly selective universities in Almaty, the former capital of Kazakhstan. These students were selected because their memories of their EPT experiences while at secondary school were relatively fresh and they tended to feel less anxious about reflecting on it than any current EPT (Silova, Būdienė, and Bray Citation2006). The students selected were from the Engineering Department since they were more likely to have received EPT than students from other departments at the selected universities, as English is the medium of instruction for many subjects in this department. All the participants were Kazakh and none of them was known to the researchers before collecting the data. The UNT is the main admission path to the two universities, which the participants of the present study had competed in to attend.

The study used two research methods: a close-ended online survey and individual online interviews. The survey sought to elicit the intensity, cost and modes of EPT as well as the participants’ motives for having EPT. Informed consent was gained in the first part of the survey. The administrative staff at the two universities sent emails to the first-year undergraduate students in the Engineering Department with a link to the survey designed in Qualtrics. The survey remained available online for 40 days to get as many responses as possible. A total of 952 students over the age of 18 (66% male and 34% female) participated in the survey.

The final item of the survey asked respondents to give their email address if they agreed to participate in an individual online semi-structured interview. Forty-five students expressed their initial willingness to participate in a follow-up interview. An email was sent to these participants about the objectives of the study, their rights and the requirements of their participation in the interview part. Only 24 students (13 from University A and 11 from University B) responded to this email. The two researchers used the Zoom programme to conduct the interviews according to the participants’ preferences. The names of the universities were anonymised. The interviewees were informed at the beginning of each interview that their participation was entirely voluntary, their identities would not be disclosed, and they could withdraw from the study at any point without any reason and with no repercussions. The interviews helped the researchers generate meaningful insights into the students’ experiences, attitudes, and feelings about EPT during ERT&L. Two interviews with each participant were conducted, the second to check the responses from the first interview and give them additional time to describe their EPT experiences (Seidman Citation2006). Interviews 1 and 2 each lasted around 40 minutes and were tape-recorded for transcription purposes (see Appendix for sample interview questions).

Clarke and Braun’s (Citation2013) guidelines for conducting thematic analysis were used to analyse the qualitative interview data. The researchers familiarised themselves with the data through reading and re-reading the interview transcripts ‘actively, analytically and critically’ after they had been translated into English (Clarke and Braun Citation2013: 205). After the process of familiarisation, the data were grouped to generate the initial codes in response to the topics in the research questions and according to the theoretical framework. Codes that shared features in general were collated to generate themes. The tentative themes derived from the coded data and the entire data set were tested. Once all the themes had been identified, the sub-themes within each theme were located to produce the thematic map of the data, presented in .

6. Results and discussion

6.1. EPT intensity and its modes

The quantitative survey data revealed that 750 out of 952 (81%) had PT, and 318 out of 750 (42.4%) had EPT within the previous 12 months. Among those who had EPT (n = 318), 55.7% (n = 177) of them were male and 43.7% (n = 139) were female. This reveals that the scale of EPT Grade 11 students in Kazakhstan had increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to Kalikova and Rakhimzhanova’s (Citation2009) study that showed only 14% of first-year undergraduates had experienced EPT over the previous 12 months, mainly to prepare for the university entry examination.

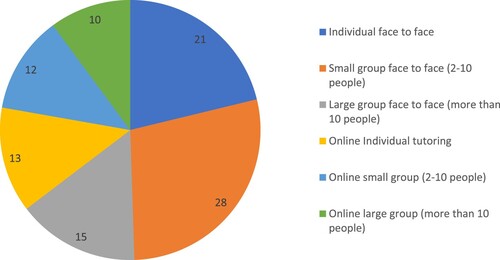

Concerning the mode of EPT delivery, 66% of the respondents took group tutoring, with 44% having face-to-face and 22% online (see ). The results also revealed that 34% of the respondents attended individual EPT, 21% face-to-face and 13% online. This finding aligns with that of Hajar and Abenova (Citation2021), who found that 50% of their participants in Kazakhstan had group tutoring because it was more affordable than individual tutoring for many households, and group tutoring tended to be more profitable for both private tutors and tutoring companies.

The quantitative data also revealed that 35% of the participants (n = 189) had received online EPT. This finding clearly indicates that more students took online tutoring during the COVID-19 pandemic than previously, because the previous empirical studies on PT in Kazakhstan either made no reference to online tutoring (e.g. Akimenko Citation2017; Kalikova and Rakhimzhanova Citation2009) or pinpointed a low scale of online tutoring, i.e. 7% (Hajar and Abenova Citation2021). As Zhang (Citation2021: 49) points out, ‘COVID-19 increased the power of technology and capital in digital learning, and online tutoring greatly expanded the shadow space’, especially since some people lost their jobs during the global pandemic, and some mainstream teachers were driven by parents who were dissatisfied with the quality of education at schools during ERT&L. Remarkably, this study reported that 64% of students received face-to-face EPT although this type of tutoring was regarded as unsafe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Related to this, Hajar Sagintayeva, and Izekenova (Citation2022) assert that Kazakhstan adopted a laissez-faire approach to the PT market – when education takes place outside mainstream school hours, it is not considered within the government’s purview. Rather, it is left to PT market forces and to the decisions of families and teachers.

6.2. Formality: practices of social actors

An analysis of the interview data showed that almost all the participants had decided themselves or with their parents to undertake EPT. As regards the mediating role of parents in the participants’ English language learning during ERT&L, most participants indicated that their parents engaged positively, but indirectly in their language education; their support was confined to emotional and/or financial support, such as by encouraging them to prepare well for the final examination, purchasing or sharing technological devices (e.g. laptops and smartphones) for online sessions and hiring for them a private tutor in English. Extracts 1 and 2 exemplify this point.

Extract 1:

It was my decision to attend tutoring because I wanted to prepare well for both UNT and IELTS exams … . My parents do not speak English, but they know its importance for my future. They supported me by giving me money to register in a tutorial centre and purchase a laptop for my online sessions. (Student 3, School B)

Extract 2:

My parents encouraged me to take tutoring in Mathematics and English because of the low quality of education at my school during the COVID-19 pandemic. My mother is a physics teacher, and she couldn’t help me with English. However, she always said to me ‘go to a private tutor and we will help you as much as we can’. (Student 7, School A)

The interviewees also commented on the teaching practices of their English language teachers and English private tutors during ERT&L due to the global pandemic. Surprisingly, perhaps, all the interviewees perceived EPT sessions as a better environment for coaching for the university entrance exam and expanding their knowledge than online classes taught by their English language teachers. They attributed this largely to the intensive practice with similar UNT items along with learning certain techniques to answer questions. Further, they received some tangible incentives and individual attention from their English private tutors, which was lacking in online English classes due to the main focus on covering the school curriculum, the indifferent attitude of some teachers to their students’ questions, the large number of students in a class or online session and the limited duration of video conferencing sessions. This point is elucidated in the following extracts.

Extract 3:

In the tutorial centre, we had a monthly quiz in Mathematics and English to prepare us for the UNT test. I was happy because when I got high scores in these quizzes, I received some presents and the fee for two months was waived … At school, none of my teachers were ready to teach online. They sometimes asked us to help them login on Zoom. Also, the online class was only for 30 minutes, and teachers didn’t care much if we understood because they had to cover the curriculum … The tutorial sessions were organised. The tutors sent us the materials in advance and the recordings of each session. (Student 2, School A)

Extract 4:

My English tutor was familiar with the format of UNT and what questions we might face. He was patient and explained the topics very well, using different activities from YouTube and other resources … . He could see my progress and if I had a question, I didn’t feel shy … My English teacher on Zoom conferencing sessions spoke most of the session and most students were afraid or embarrassed to ask a question. (Student 1, School B)

6.3. Locus of control: motives of having EPT

The analysis of the descriptive statistics provided the motives for having EPT, shown in . The most common reason reported by students was preparing for the university entrance exam (n = 222, 69.8%). The second most common reason was to understand the subjects better (n = 102, 32.1%), and 18.86% (n = 60) of respondents took EPT to prepare for the IELTS exam as a pre-requisite to pursue their own studies at one of the highly selective EMI universities in Kazakhstan, or abroad. Also, some indicated that they needed to obtain additional support because of the disruption from the COVID-19 outbreak (n = 28, 8.8%). Other possible reasons like parents or teachers’ recommendations did not have a substantial impact on students’ decisions to receiving EPT.

Table 1. Reasons for having EPT.

The interview data also demonstrate that almost all interviewees indicated that their main reason for receiving EPT was to receive UNT test familiarisation and practice so as to obtain state tuition grants for highly selective universities, mainly because their teachers at mainstream schools did not coach them for this test. Extracts 5 and 6 elucidate this point.

Extract 5:

I had tutoring in Mathematics, Physics and English. Tutoring was important to me to get a high score in the final exam and apply for a state grant at one of the top universities in Kazakhstan. I wanted to live up to my parents’ expectations. (Student 6, School B)

Extract 6:

Almaty was on a red zone due to COVID-19. My father was worried about my safety, so I had only online tutoring to pass the UNT and win a grant to my favourite university. (Student 6, School B)

6.4. Pedagogy: advantages and disadvantages of online EPT

As already stated, 35% of the respondents (n =189) and 16 out of 24 interviewees had received online EPT. summarises the interviewees’ reported advantages and disadvantages associated with online EPT.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of online EPT.

As illustrated in , almost all the interviewees had a positive attitude towards online EPT sessions because they were largely tailored to their individual needs, especially because the online classes delivered by their schoolteachers were less organised, and the schoolteachers provided mediocre teaching without covering the whole curriculum during COVID-19 pandemic or preparing their students adequately for the high-stakes university entrance exams. Therefore, tutoring represented almost the only solution for students to be coached for the high-stakes exams and win a state grant to higher education. As Yung (Citation2021: 125) suggests, ‘PT exploits the oppressive education system embedded with high-stakes testing and makes a profit from the oppressed learners’.

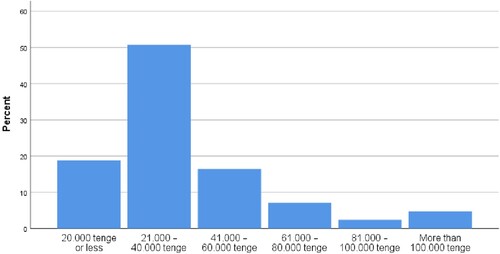

also indicates that PT created a considerable financial burden on many students’ parents. The quantitative data revealed that 47.5% (n = 151) of the respondents reported their parents spent 21,000–40,000 Tenge (US$ 44–84) on average on PT sessions per month, 17.6% (n = 56) spent 20,000 Tenge or less (US$42) and 15.4% (n = 49) spent 41,000–60,000 Tenge (US$ 86–125) (see ). The issue of expenditure on PT as a financial burden has also been reported in other studies (e.g. Hajar Citation2018 in England; Bray, Kobakhidze, and Kwo Citation2020 in Myanmar; Kim Citation2016 in South Korea). Bray, Kobakhidze, and Kwo (Citation2020), for instance, found that 68.1% of Grades 9 and 11 students in Myanmar indicated that PT was a moderate or heavy financial burden on their families.

Further, one of the disadvantages of EPT mentioned by some interviewees was being deceived by being taught by some private tutors who pretended that they were highly qualified before they discovered that these tutors had little teaching experience and/or were not specialised in English language teaching. This finding might be ascribed to the fact that some individuals sought an alternative income after they had lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bray and Hajar Citation2023) and the PT market in Central Asia is not regulated by the governments of these countries. As Silova (Citation2010: 340) argues, ‘imperfect legislation, lack of implementation mechanisms, and absence of legal enforcement’ describes the PT market in Central Asia.

7. Conclusion and implications

The study reported here is the first empirical study to examine students’ EPT experiences in Kazakhstan during the global pandemic, using both a close-ended questionnaire and semi-structured online interviews. The findings show that the scale of EPT expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, in that 318 out of 750 (42.4%) had EPT. 64% of respondents received face-to-face EPT although this type of tutoring was regarded as unsafe during the global pandemic. This is mainly because Kazakhstan – like many other countries in Central Asia and elsewhere – adopted a laissez faire approach to the PT sector by ignoring the phenomenon and viewing it as beyond their control and responsibility (Hajar, Sagintayeva, and Izekenova Citation2022).

Notably, the governments of some other countries prohibited all types of face-to-face PT alongside face-to-face schooling in their efforts to restrict the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. The United Arab Emirates, for instance, took the logical step of closing face-to-face PT in tutorial centres and by individual tutors, warning that anyone giving face-to-face PT would be fined AED30,000 (US$8168), and host venues would also be fined AED20,000 (US$5445) (Bray and Hajar Citation2023). Elsewhere, Bray (Citation2022: 10) described how some governments in higher-income countries (e.g. England and Australia) had encouraged online tutoring during the global pandemic because it was regarded as mechanism to ‘catch up’ in the context of ‘lost time’ where social distancing measures were applied. As PT has become a globally pervasive phenomenon and obtained more pragmatic and normative legitimacy, Bray (Citation2022: 10) underlines the importance of understanding the nature, effectiveness and implications of fee-charging PT in the post-Covid period ‘rather than being simply allowed to slide forward with the changing times’.

The largely laissez-faire situation in relation to the PT market in Kazakhstan and elsewhere allowed the emergence of tutors who faked information about their academic qualifications to attract customers. Therefore, it is essential for the authorities to issue a licensing system to regulate the PT market in general, not only during the global pandemic, by introducing codes of practice. In Mainland China, for instance, schoolteachers are banned from giving PT to their students and tutorial companies are prohibited from covering the official school curriculum in advance, to protect schools and take the pressure off students from disadvantaged backgrounds who are unable to participate in fee-charging PT to catch up with their counterparts (Zhang Citation2021). To license a tutorial centre in Qatar, certain conditions must be fulfilled, including clearly displaying prices at the headquarters, only employing tutors with a higher qualification in their field of specialisation and maintaining data on courses and other services (Bray and Hajar Citation2023).

The findings of this study revealed that the students acted agentively by critically reflecting on the benefits and disadvantages of EPT during the global pandemic, especially because their English language teachers at school did not coach them for the university entrance exam and showed indifferent attitude to students’ questions as well as having little experience of teaching online. Therefore, receiving EPT tutoring at the end of secondary schooling to pass a high-stakes exam and win a state tuition grant to one of the prestigious universities represents what Denzin (Citation1989: 70) calls ‘an epiphany’, or ‘key transformational episodes’ (Dörnyei and Ushioda Citation2011: 68) that could affect their future vision of themselves. Therefore, EPT was perceived as a real salvation for students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gao (Citation2013: 228) remarks that ‘reflexive/reflective thinking or thinking during action and post-event in the learning process’ is indicative of agency as it shows an individual’s intentionality. Related to this, policy makers should not only provide schoolteachers with adequate training for delivering online classes, but also in how to use online platforms and evaluate their effectiveness. Insufficient teacher preparation on how to deliver online lessons and design teaching materials during the COVID-19 pandemic was reminiscent of reports in other contexts, especially in developing countries, such as Hashemi (Citation2021) in Afghanistan and van Cappelle et al. (Citation2021) in India.

It is worth noting that the findings of the present study in relation to the importance of PT to prepare for significant examinations align with international research which has shown that education systems with high-stakes assessments at watershed points have a strong incidence of PT (Zwier, Geven, and Werfhorst Citation2020). It seems that PT has been absorbed into the education culture and is hard and unrealistic to eliminate it altogether because families will always be competitive, but policy makers need to pay attention to matters of curriculum, including the impact of high-stakes examinations. They can also consider teachers’ delivery styles and the availability of in-school support for students with diverse needs (see Bray and Hajar Citation2023; Zhang Citation2023). Although this study can be a call to language researchers to conduct additional research to further understand the nature and effectiveness of EPT during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, it has some limitations. For example, it relied only on the data collected from undergraduate students from two universities in Kazakhstan. Therefore, future empirical studies which include students, parents and English private tutors would enrich the database available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addi-Raccah, A. 2019. Private tutoring in a high socio-economic secondary school in Israel and pupils’ attitudes towards school learning: A double-edged sword phenomenon. British Educational Research Journal 45, no. 5: 938–996.

- Akimenko, O. 2017. Investigating the effectiveness of private small group tutoring of English in Kazakhstan: Perceptions of tutors and students. NUGSE Research in Education 2, no. 1: 16–26.

- Aurini, J., S. Davies and J. Dierkes. 2013. Out of the Shadows: The Global Intensification of Supplementary Education. Bingley: Emerald.

- Baker, D. P. 2020. An inevitable phenomenon: Reflections on the origins and future of worldwide shadow education. European Journal of Education 55, no. 3: 311–315.

- Ball, S.J. 2003. The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy 18, no. 2: 215–28.

- Benson, P. 2011. Language learning and teaching beyond the classroom: an introduction to the field. In Beyond the Language Classroom, eds. P. Benson and H. Reinders, 7–16. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Benson, P. and H. Reinders. 2011. Introduction. In Beyond the Language Classroom, eds. P. Benson and H. Reinders, 1–6. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Block, D., J. Gray and M. Holborow. 2013. Neoliberalism and Applied Linguistics. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Bokayev, B., Z. Torebekova, Z. Davletbayeva, and F. Zhakypova. 2021. Distance learning in Kazakhstan: Estimating parents’ satisfaction of educational quality during the coronavirus. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 30, no. 1: 27–39.

- Bray, M. 2011. The Challenge of Shadow Education: Private Tutoring and Its Implications for Policy Makers in the European Union. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

- Bray, M. 2013. Benefits and tensions of shadow education: comparative perspectives on the roles and impact of private supplementary tutoring in the lives of Hong Kong students. Journal of International and Comparative Education 2, no. 1: 18–30.

- Bray, M. 2021. Shadow Education in Africa: Private Supplementary Tutoring and Its Policy Implications. Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong: UNESCO.

- Bray, M. 2022. Timescapes of shadow education: patterns and forces in the temporal features of private supplementary tutoring. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 1–14.

- Bray, M. and A. Hajar. 2023. Shadow Education in the Middle East: Private Supplementary Tutoring and Its Policy Implications. Hong Kong: Routledge.

- Bray, M., M.N. Kobakhidze and O. Kwo. 2020. Shadow Education in Myanmar: Private Supplementary Tutoring and its Policy Implications. Hong Kong/Paris: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong/UNESCO.

- Chankseliani, M., I. Qoraboyev, D. Gimranova, and Kurakbayev K. 2020. Rural disadvantage in the context of centralised university admissions: a multiple case study of Georgia and Kazakhstan. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 50, no. 7: 995–1013.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. and V. L. P. Clark. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Denzin, N. 1989. Interpretive Biography. biography. Newbury Park: Falmer Press.

- Dörnyei, Z. and E. Ushioda. 2011. Teaching and Researching Motivation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Longman.

- Durrani, N., J. Helmer, F. Polat, and G. Qanay. 2021. Education, Gender and Family Relationships in the Time of COVID-19: Kazakhstani Teachers’, Parents’ and Students’ Perspectives. Partnerships for Equity and Inclusion (PEI) Pilot Project Report. Graduate School of Education, Nazarbayev University.

- Gao, X. 2013. Reflexive and reflective thinking: a crucial link between agency and autonomy. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 7: 226–37.

- Hajar, A. 2018. Exploring year 6 pupils’ perceptions of private tutoring: evidence from three mainstream schools in England. Oxford Review of Education 44, no. 4: 514–31.

- Hajar, A. and S. Abenova. 2021. The role of private tutoring in admission to higher education: evidence from a highly selective university in Kazakhstan. Hungarian Educational Research Journal 11, no. 2: 124–42.

- Hajar, A. and M. Karakus. 2022. A bibliometric mapping of shadow education research: achievements, limitations, and the future. Asia Pacific Education Review 23: 341–359.

- Hajar, A. and M. Karakus. 2023. Throwing light on fee-charging tutoring during the global pandemic in Kazakhstan: implications for the future of higher education. Asia Pacific Education Review, 1–13.

- Hajar, A. and S.A. Manan. 2022. Emergency remote English language teaching and learning: voices of primary school students and teachers in Kazakhstan. Review of Education 10, no. 2: e3358.

- Hajar, A., A. Sagintayeva and Z. Izekenova. 2022. Child participatory research methods: exploring grade 6 pupils’ experiences of private tutoring in Kazakhstan. Cambridge Journal of Education. DOI:10.1080/0305764X.2021.2004088.

- Hajar, A., A. Si Mhamed. 2021. Exploring postgraduate students’ challenges and strategy use while writing a master’s thesis in an English-medium University in Kazakhstan. Tertiary Education and Management 27, no. 3: 187–207.

- Hashemi, A. 2021. Online teaching experiences in higher education institutions of Afghanistan during the COVID-19 outbreak: challenges and opportunities. Cogent Arts & Humanities 8, no. 1: 1–22. DOI:10.1080/23311983.2021.1947008.

- Holloway, S. L., and P. Kirby. 2020. Neoliberalising education: New geographies of private tuition, class privilege, and minority ethnic advancement. Antipode 52, no. 1: 164–184.

- Kalikova, S. and Z. Rakhimzhanova. 2009. Private tutoring in Kazakhstan. In Private Supplementary Tutoring in Central Asia: New Opportunities and Burdens, ed. I. Silova, 93–118. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP).

- Kim, Y.C. 2016. Shadow Education and the Curriculum and Culture of Schooling in South Korea. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lasekan, O., A. Moraga and A. Galvez. 2019. Online marketing by private English tutors in Chile: a content analysis of a tutor listing website. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 18, no. 12: 46–62.

- Lee, B. 2010. The pre-university English-educational background of college freshmen in a foreign language program: a tale of diverse private education and English proficiency. Asia Pacific Education Review 11, no. 1: 69–82. DOI:10.1007/s12564-010-9079-z.

- Luo, J. and C.K.Y. Chan. 2022. Influences of shadow education on the ecology of education – a review of the literature. Educational Research Review 40, no. 3: 327–44. DOI:10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100450.

- Manan, S. A., and A. Hajar. 2022. “Disinvestment” in learners’ multilingual identities: English learning, imagined identities, and neoliberal subjecthood in Pakistan. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–16.

- Seidman, I. 2006. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Silova, I. 2009. Private Supplementary Tutoring in Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Silova, I. 2010. Private tutoring in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: policy choices and implications. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 40, no. 3: 327–44.

- Silova, I., V. Būdienė and M. Bray, eds. 2006. Education in a Hidden Marketplace: Monitoring of Private Tutoring. New York: Open Society Institute.

- Van Cappelle, F., V. Chopra, J. Ackers and P. Gochyyev. 2021. An analysis of the reach and effectiveness of distance learning in India during school closures due to COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Development 40, no. 3: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102439.

- Yung, K.W.H. 2021. Shadow education as a form of oppression: conceptualizing experiences and reflections of secondary students in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 41, no. 1: 115–29.

- Yung, K.W.H. and A. Hajar. 2023. International Perspectives on English Private Tutoring: Theories, Practices, and Policies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zhang, W. 2021. Non-State Actors in Education: The Nature, Dynamics and Regulatory Implications of Private Supplementary Tutoring. Background Paper for the Global Education Monitoring Report. UNESCO.

- Zhang, W. 2023. Taming the Wild Horse of Shadow Education: The Global Expansion of Private Tutoring and Regulatory Responses. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Zhang, W. and M. Bray. 2020. Comparative research on shadow education: achievements, challenges, and the agenda ahead. European Journal of Education 55, no. 3: 322–41.

- Zhang, W. and M. Bray. 2021. A changing environment of urban education: historical and spatial analysis of private supplementary tutoring in China. Environment and Urbanization 33, no. 1: 43–62.

- Zhang, W. and Y. Yamato. 2018. Shadow education in East Asia: entrenched but evolving private supplementary tutoring. In Routledge International Handbook of Schools and Schooling in Asia, 323–32. London: Routledge.

- Zwier, D., S. Geven and V. Werfhorst. 2020. Social inequality in shadow education: the role of high-stakes testing. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 61, no. 6: 412–40.

Appendix

Selected interview questions

Have you received English private tutoring in the last 12 months? Who suggested it?

Were your English tutoring sessions face-to-face or online? Which one was more useful? Why?

How many hours per week did you attend English private lessons? How much was the cost?

What did you learn in English private tutoring? Was it different to learning in online classes with schoolteachers? Why and how?

Why did you take English private tutoring? Was it useful? Why?

As learning became online due to the COVID-19 virus, did you think this made you and your peers attend private tutoring?

Did your parents know about your academic progress? What did they do? What sorts of support did they give to you?

What about the advantages and disadvantages of English private tutoring during COVID-19 pandemic?

What do you think about the future of the private tutoring market in Kazakhstan? Is it going to expand or decrease? Why do you think so?