ABSTRACT

The pandemic-induced shift to online learning has increased the relevance of Online Intercultural Exchanges (OIE) as a means to navigate student mobility challenges. Our study investigates the role of OIE in the internationalisation of higher education, focusing on how students’ perceptions of the benefits of internationalisation through OIE have shifted from the pre-pandemic to the pandemic period. We analysed an English-Japanese OIE programme conducted by an Australian and a Japanese university from 2018 to 2022, noting students self-reported higher gains in learning engagement and outcomes during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. Our research, guided by the frameworks of ‘Internationalisation at Home’ (IaH) and ‘Internationalisation at a Distance’ (IaD), highlights the potential of OIE as an effective model that addresses the diverse needs of a student body transcending the traditional dichotomy of ‘home’ and ‘abroad’.

Introduction

In response to the rapid shift to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this study investigates a pivotal question: How have students’ perceptions of the benefits of internationalisation through Online Intercultural Exchanges (OIE) shifted from the pre-pandemic to the pandemic period? Drawing on data from 2,158 participants in English-Japanese semester-based OIE sessions held between an Australian and a Japanese university from 2018 to 2022, the study evaluates students’ self-reported learning engagement and outcomes. It compares these aspects across pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, specifically investigating the pandemic's impact.

OIE involves ‘the engagement of groups of students in online intercultural interaction and collaboration with partner classes from other cultural contexts or geographical locations under the guidance of educators and/or expert facilitators’ (Lewis and O’Dowd Citation2016: 3). Central to OIE are activities that foster intercultural and international exchange. Prominent examples include the Erasmus + Virtual Exchange (VE) programme supported by the European Commission and Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), an initiative pioneered by the State University of New York (Rubin Citation2016; SUNY COIL Citationn.d.). Our study examines the role of OIE in tertiary language education, comparing pre- and during-pandemic scenarios through the frameworks of ‘Internationalisation at Home’ (IaH)’ and ‘Internationalisation at a Distance’ (IaD). IaH is geared towards enhancing intercultural and international understanding among students in their home countries (Beelen and Jones Citation2015; De Wit Citation2016; Huang et al. Citation2022; O’Dowd Citation2023; Potolia and Derivry-Plard Citation2023). In contrast, IaD centres on education that transcends geographical boundaries, virtually connecting students, educators and institutions, regardless of their current locations, through technology (Knight Citation2008; Mittelmeier et al. Citation2019). While both IaH and IaD facilitate virtual student mobility, we employ the framework of IaD as an extension of IaH, highlighting that OIE allows participation not only by students within their home countries but also by those engaging from overseas locations. This approach thus aims to expand the conventional ‘home’ and ‘abroad' dichotomy often used in the discourses of internationalisation.

While the effectiveness of OIE programmes is increasingly recognised, their development and implementation have often been marginalised in education, primarily utilised by limited groups of language educators in Euro-American regions (O’Dowd Citation2017). The mobility constraints imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic have propelled OIE further to the forefront as a potentially effective pedagogical solution (Breaden et al. Citation2023). Despite this growing prominence, there remains a lack of multi-year empirical research on OIE’s role in internationalisation efforts, particularly in non-Euro-American regions (De Wit Citation2016). Our research aims to bridge this gap by analysing data from students participating in extracurricular OIE programme sessions between an Australian and a Japanese university over a five-year span, encompassing both pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. It seeks to explore the potential of OIE as a fundamental component of IaH and IaD, facilitating student engagement and enhancing learning outcomes. This investigation aims to provide additional insights into OIE’s role in intercultural understanding and international education. Research suggests that OIE can serve as a substitute for physical global exchange programmes during pandemics like COVID-19 (Breaden et al. Citation2023; Ikeda Citation2022; Konishi Citation2021; Normand-Marconnet et al. Citation2022; Skidmore Citation2023; Tajima and Fukui Citation2022; Takei et al. Citation2021; Weinmann et al. Citation2024). This study initiates a discussion on the potential of OIE as a pivotal tool that offers unique learning experiences beyond pandemics, providing benefits that traditional internationalisation methods may not fully replicate.

The article is organised into four sections. The first section examines the interplay between OIE and internationalisation in language learning, anchored by the IaH and IaD frameworks. The subsequent section briefly discusses the heightened demand for OIE in higher education in Australia and Japan, catalysed by pandemic-induced opportunities and challenges. The third section presents research findings on students’ perceptions of OIE’s impact on learning engagement and outcomes, drawing from multi-year student survey data. The article concludes with a discussion of these findings through the lenses of IaH and IaD, identifying key areas for further research to advance language learning and internationalisation in higher education.

Assessing the nexus between the frameworks of internationalisation and OIE

The evolution of higher education’s internationalisation approach has been marked by a significant shift over the past few decades. Initially focused on ‘Internationalisation Abroad’ (IA), which primarily involved physical student mobility programmes (Knight Citation2008), the scope has now broadened to include ‘Internationalisation at Home’ (IaH). IaH integrates intercultural and international elements into the local educational environment (Beelen and Jones Citation2015; De Wit Citation2016; Huang et al. Citation2022; O’Dowd Citation2023; Potolia and Derivry-Plard Citation2023). A key feature of IaH is its emphasis on virtual mobility, supported by technological advancements such as increasingly accessible digital tools and platforms. This approach delivers an intercultural and international experience within students’ own countries, thereby eliminating the need for physical travel and associated costs.

The pandemic’s impact on global mobility has accelerated the transformation of intercultural and international education. Technological advancements have further facilitated cross-border learning, making these educational opportunities more accessible to students with stable internet access and digital tools, whether they are at home or abroad. This shift exposes the limitations of the IaH framework, which does not account for students engaging in internationalisation programmes remotely from locations other than their home countries. This includes international students in host institutions who utilise opportunities to connect with peers in other countries. The ‘Internationalisation at a Distance’ (IaD) framework addresses this gap. IaD encompasses students who engage in intercultural and international education from locations outside their own countries, primarily through remote online learning (Knight Citation2008; Mittelmeier et al. Citation2019). The emergence of this framework signals a significant shift in the landscape of higher education internationalisation, moving beyond the traditional dichotomy of ‘home’ and ‘abroad’. This shift is exemplified by the OIE programme in our study, which engages both domestic and international students from an Australian and a Japanese university, including those situated beyond traditional campus settings. This development necessitates a combined application of the IaH and IaD frameworks, offering a comprehensive perspective of OIE’s role in higher education. While research on IaD is in its nascent stages and not as theoretically developed as IaH, it expands the scope of IaH by encompassing diverse student experiences in intercultural and international education. This integration enhances our understanding of internationalisation, where student experiences now span a continuum from local to global, propelled by digital technologies and online global interactions.

The theoretical development of IaD benefits from the established principles of IaH, which advocate for inclusivity, technological innovation and comprehensive curricula (Beelen and Jones Citation2015; De Wit Citation2016; Huang et al. Citation2022; O’Dowd Citation2023; Potolia and Derivry-Plard Citation2023). These curricula are designed to equip students with the knowledge, skills and intercultural sensitivity needed to thrive in a globally interconnected world. In the context of higher education internationalisation, comprehensive curricula are not limited to language studies but include non-language and interdisciplinary courses that provide a well-rounded, internationally-focused education (Hudzik Citation2015). This approach should be embraced by institutional leadership, governance, faculty, students and all academic service and support units, integrating it throughout the teaching, research and service missions of higher education (Hudzik Citation2015).

Applying these IaH principles to an IaD perspective offers valuable insights, including: (1) leveraging language and cultural diversity as a learning resource and promoting cultural inclusivity as a pedagogical mission; (2) utilising technological innovation to widen access for those with limited mobility options; and (3) integrating a comprehensive curriculum that infuses intercultural and international dimensions into teaching, research and support services across the university (Crowther et al. Citation2000; Harrison Citation2015). These tenets are key to democratising access to internationalisation practices, reflecting the ongoing shift towards pedagogical innovation and strategic planning in the internationalisation of higher education (Beelen and Jones Citation2015; De Wit Citation2016; Huang et al. Citation2022).

These principles resonate with the aims of OIE, which focus on facilitating online intercultural interactions and learning among diverse student groups (Lewis and O’Dowd Citation2016). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the relevance of OIE, demonstrating its adaptability not only in language education but also across a range of other disciplines (O’Dowd Citation2023). Traditionally prominent in Euro-American contexts (O’Dowd Citation2021; Stevens Initiative Citationn.d.; UNICollaboration Citationn.d.), the adoption of OIE has recently expanded to regions like Asia and Oceania, driven by pandemic-related physical mobility constraints. This trend is evident in recent academic contributions (Breaden et al. Citation2023; Ikeda Citation2022; Konishi Citation2021; Normand-Marconnet et al. Citation2022; Skidmore Citation2023; Tajima and Fukui Citation2022; Takei et al. Citation2021; Weinmann et al. Citation2024). While there is an expanding body of literature exploring the impact of the pandemic on language learning and how OIE can support learning during such times, to our knowledge, there are few multi-year comparative studies examining the usage of OIE in language learning within higher education across pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. Our study further contributes to the field by repositioning OIE from a temporary solution to a potentially transformative educational strategy aligned with the key principles of the IaH and IaD frameworks. To achieve this, we evaluate OIE’s potential in redefining internationalisation in language education, with a specific focus on student engagement and learning outcomes within an extracurricular English-Japanese OIE programme conducted by an Australian and a Japanese university.

Navigating Covid-19: language learning and mobility challenges in Australian and Japanese higher education

This section examines the impact of the pandemic on OIE in higher education in Australia and Japan. It highlights how the pandemic reshaped the landscape of intercultural and international education, especially in language learning, presenting both challenges and new opportunities for innovation in this field.

Australia

Since the 1980s, Australian universities have actively engaged in international education, focusing primarily on recruiting international students for both revenue generation and enhancing internationalisation in education (De Wit and Altbach Citation2021; Rizvi Citation2020). By 2019, international student enrolment was Australia’s third largest export, contributing AU$40.3 billion to the economy (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2023), with about 30% of university revenue deriving from international student fees (Australian Government Citation2016). The pandemic thus profoundly impacted Australia’s university financial model, with international student numbers plummeting from 509,160 in 2019 to 266,000 by late 2021 (Department of Home Affairs Citation2023; UNESCO Institute for Statistics Citation2019). Travel restrictions and visa complications contributed to this decline, particularly affecting the financial health of 39 members of Universities Australia out of the total 42 universities in the country (Universities Australia Citation2022). These members, known as ‘comprehensive universities’, offer a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate programmes across various disciplines, including arts and humanities, sciences, social sciences, engineering, business and professional fields. This downturn led to reductions in language course offerings in some of the members of Universities Australia amid fluctuating international student enrolments (The Guardian, 16 April 2021; ABC News, 19 June 2020; BBC, 29 July 2020). This occurred despite the ‘Job-Ready Graduates’ reform package introduced by the previous Morrison Government in 2021, which prioritised funding for courses deemed directly job-enhancing, including exemptions for language courses (ABC News, 19 June 2020; BBC, 29 July 2020).

The adoption of OIE in Australian universities for language education predates the COVID-19 pandemic, and this is also the case for English-Japanese OIE programmes. These programmes traditionally integrated a blend of synchronous and asynchronous activities, including email exchanges and live text chats, to facilitate language learning (Bower and Kawaguchi Citation2011; Pasfield-Neofitou Citation2011; Stockwell and Levy Citation2001; Toyoda and Harrison Citation2002). The pandemic’s onset expedited the transition to online platforms, underscoring not merely the effectiveness of virtual learning (Drane et al. Citation2020) but also the importance of participatory digital learning practices, including student-initiated collaborative online international learning projects (Breaden et al. Citation2023). This shift is exemplified in a study by Breaden et al. (Citation2023), which highlights the transformative role of OIE in redefining higher education’s approach to internationalisation and the dynamics between students, educators and universities. As part of an action research project, the study examines the implementation of the ‘Students as Partners’ (SaP) approach in shaping OIE. The SaP approach is described as a ‘collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualisation, decision making, implementation, investigation, or analysis’ (Cook-Sather et al. Citation2014: 6-7 Citation2023). This approach challenges the prevailing ‘Students as Customers’ model (Gravett et al. Citation2020) and the conventional educator-student power imbalance (Breaden et al. Citation2023). Empirical data from the study suggests that the SaP model can serve as an effective ‘“win-win” strategy’ for OIE (Breaden et al. Citation2023: 1193), potentially fostering a more profoundly student-centric approach in intercultural and international education. While further case studies and empirical research are necessary to bolster the evidence, this study illuminates novel avenues for OIE’s influence, expanding beyond logistical and pedagogical aspects of internationalization to make a contribution to the field of action research.

Japan

While Japan’s reliance on revenue from international students is much less than Australia’s, the country has experienced dramatic growth in the number of international students in higher education over the past few decades, increasing from 5,849 in 1978 to 228,403 in 2019 (Japan Student Services Organization [JASSO] Citation2021). However, like Australia and many other countries, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted student mobility. By May 2021, international student enrolment in Japan had fallen by 13.3%, with nearly 9.1% of students forced to study online due to travel restrictions (JASSO Citation2021). Additionally, a 2020 survey by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) reported declines in international student applications at numerous Japanese universities. Concurrently, in the fiscal year 2020, the number of Japanese students studying abroad plummeted by 98.6%, with only 1,487 attending overseas institutions (JASSO Citation2021).

Amid the pandemic-induced challenges, some Japanese universities have adopted OIE and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) solutions. These efforts align with key pre-pandemic initiatives such as the ‘Inter-University Exchange Project’ and the ‘Top Global University Project’, spearheaded by the MEXT. The ‘Inter-University Exchange Project’, initiated in 2011, focuses on fostering international collaborations and student exchanges to enhance global competencies (MEXT Citationn.d.a). Meanwhile, the ‘Top Global University Project’, launched in 2014, aims to boost the international standing of Japanese universities by supporting the attainment of ‘world-class’ educational standards and the development of global leaders (MEXT Citationn.d.b). Despite the ambitious goals of these initiatives, as of now, there is limited data available to assess their effectiveness.

The pandemic heightened the importance of offering inclusive alternatives to traditional study abroad experiences, which are often exclusively available to students with financial resources (Iwaki Citation2012). This transition is seen as a means to reduce the risk of elitism in international education (Mason et al. Citation2024). In response to the shifting educational landscape, the National University Association’s Committee on International Exchange (Kokuritsu Daigaku Kōkai Citation2021) recommended developing new international exchange models post-pandemic, emphasising a dual approach of expanding both traditional and online exchanges. This strategy involves fostering informal virtual interactions, such as voluntary extracurricular OIE programmes outside of class, alongside formal online courses. While research on the effectiveness of the approach is still emerging, preliminary studies have identified opportunities and challenges for both practitioners and participants. A key challenge in the literature on OIE practices in Japanese higher education is that, despite the growing recognition of their benefits in Japan (Ikeda Citation2022; Nakahashi Citation2022; Shimmi et al. Citation2021; Yonezawa et al. Citation2023), instructors tend to perceive integrating OIE into traditional teaching as ‘burdensome’ (Ikeda Citation2016). This perception stems from the various tasks involved, including pre-negotiations with overseas partner institutions, task preparation, technology setup and learning new teaching approaches and effective intercultural communication (Ikeda Citation2016). Consequently, full-scale implementation and expansion of OIE remain rare university-wide in Japan, with only a few exclusive instructors currently implementing it. For participants, while they exhibit increased motivation for intercultural communication and experience improvements in mental health through these interactions (Konishi Citation2021), some challenges persist. These challenges include the absence of clear non-verbal language markers and difficulties in forming a cohesive learner community (Akasaki Citation2021). These findings underscore the complex impact of OIE on educational and interpersonal outcomes.

The study

This section presents the background to the programme reported in this study, introduces the participants, details the methodologies utilised and describes the analytical approach taken for the gathered data.

The English-Japanese OIE programme

The programme is a collaboration between an Australian university’s Japanese studies department and a Japanese university’s study abroad centre. It provides students from both universities with an optional extracurricular OIE each semester. Annually, 100–200 Australian students and an equivalent number of Japanese students participate. Though voluntary and non-credit-bearing, participants are advised to have basic language proficiency. Australian attendees usually study at various Japanese language levels, while many Japanese attendees are from non-English majors. The Australian participants are increasingly international, predominantly from Asia, whereas the Japanese participants are largely domestic. Students are paired based on their language abilities and interests by the staff from their respective universities. In the programme, emphasis is placed on practical language application. Students manage their OIE sessions largely independently, but staff can intervene when necessary to address concerns.

Launched in 2015, this OIE programme represents a joint initiative by the Japanese department of Monash University in Australia and the intercultural exchange centre of Waseda University in Japan. It provides a voluntary extracurricular OIE for students from both institutions, conducted outside of regular class hours each semester. The programme’s focus on language application and intercultural understanding reflects key principles for effective OIE outlined by Normand-Marconnet et al. (Citation2024), including (1) a shared sense of responsibility and ownership among students and (2) multimodal and multilingual communication. Participants have the flexibility to personalise their OIE sessions, choosing when and how often to meet, and selecting their preferred online platforms of communication. This autonomy fosters self-directed learning, allowing students to shape their own learning paths. However, it is equally important to have a support system that nurtures a shared sense of responsibility and ownership among students. In this programme, students receive support from programme staff for any challenges that arise, ensuring they are not navigating this process alone. Additionally, before the programme begins, students are provided with guidelines to ensure respectful interaction among all participants. Further, there is an increasing trend towards integrating interactive, multimodal and multilingual communication strategies. This trend includes incorporating online games and YouTube videos in various languages into the sessions. The shift became particularly evident during the pandemic with the widespread adoption of Zoom, which supports various modes of communication and has surpassed Skype as the main platform used pre-pandemic. Notably, several Japanese students who participated in the sessions during the pandemic reported learning additional languages such as Chinese and German. This was achieved not only through conversation times but also by incorporating multimedia elements into the sessions, driven by their multilingual partners. This reflects the diverse linguistic backgrounds, particularly among the participant group from their Australian partner institution.

Participants

In our study, a total of 2,158 students from both the Australian and Japanese university participated between 2018 and 2022, with each university contributing equally, amounting to 1,079 students each. Participants from the Australian university were enrolled in Japanese language courses ranging from introductory to advanced, or joined the programme outside of formal course enrolment to maintain their Japanese skills. From 2018 to 2022, a notable 16.13% of these students chose to major in Japanese. The majority of the students were enrolled in the Faculty of Arts, averaging 43.93% over this period. Other students pursued degrees in the Faulty of Information Technology, Business and Economics, and Arts, Design and Architecture, reflecting a diverse range of academic interests. The national composition of the Australian university cohort was diverse, with 47.82% being Australian citizens and 52.18% comprising international students from 25 different countries. The representation of students from Asian countries in the cohort was particularly significant, with an average of 32.62% coming from China, 5.84% from Malaysia and 2.41% from Vietnam. This diversity underscores the programme’s wide-reaching appeal and its capacity to engage a globally diverse student body. Notably, students with international citizenship accounted for more than 40% of total undergraduate enrolments at the university, according to the most recent data available (Monash University 2019), further contributing to the diversity of the OIE programme participants. The programme has been widely promoted within the institution’s Japanese language courses, which attract over 1,500 enrolments annually, thus drawing a large and diverse range of students.

At the Japanese university, the majority of OIE programme participants were Japanese citizens, exceeding 95%. Like their partner university, these students were enrolled in a variety of faculties, including media and society, political science and economics, international studies, and law and education. The programme saw limited international participation in 2018 and 2019, with typically one to three students from China and South Korea. However, there was a notable increase in international student involvement in the second semester of 2020 and the first semester of 2022, attracting six to ten students from up to eight different countries. The institution has a dedicated administrative team promoting the OIE programme as part of its university-wide internationalisation initiative. This effort has facilitated broader distribution of the programme and ensured that participants align with the scale and needs of their counterparts at the Australian partner institution.

Pre-pandemic, participants from Monash University and Waseda University were located in their respective countries. However, this does not mean that their engagement in OIE was limited to IaH. Notably, Monash University hosts a significant international cohort, with many students participating in the OIE programme from locations outside their home countries. This situation indicates that the IaD framework more accurately describes their participation, rather than IaH. During the pandemic, the complexity increased as some international students returned to their home countries, while others stayed in Australia, diversifying participation modes. While this was more evident at Monash University than at Waseda University, not all participants from Waseda University engaged in the OIE programme in their home country; a few international students participated from abroad. Given these conditions, the IaD framework more aptly describes the nature of OIE engagement than IaH, since it captures the experiences of both local and distant students, better reflecting the varied realities of engagement in the programme.

Research design

This study (Project ID: 30513) received approval from the Human Ethics Committee of the authors’ affiliated institution. Our findings stem from anonymous online surveys conducted at the end of each OIE programme semester from 2018 to 2022. While survey completion was expected of participants, anonymity was assured and it was clearly communicated that their responses would not affect academic performance. This measure was intended to ensure that responses genuinely reflected the participants’ experiences without external influence.

The OIE programme commenced in 2015; however, this study only includes data from 2018 onward to focus on the two years immediately preceding the pandemic and the first three years of the pandemic itself. Data from before 2018 were excluded also due to the surveys not being in accessble formats, making comprehensive data retrieval from the Japanese partner university challenging. The survey, consistent each semester, comprised 18 questions before the pandemic and was expanded to 19 questions during the pandemic. In 2020, an extra question was added to the survey to collect information about the communication tools used. Before the pandemic, Skype was the primary online communication platform. However, during the pandemic, other platforms like Zoom began to be widely used among students (see Appendix for survey details). Both quantitative and qualitative formats were used in a single survey per semester to assess participants’ experiences in the OIE programme. This consistent methodology across the years ensured the comparability of data. Quantitative queries, which utilise multiple-choice options, focused on the logistical aspects of the OIE sessions. Qualitative questions explored participants’ perceptions of the benefits of the OIE programme and their overall experiences, including the challenges they encountered during the sessions.

Our study employs a mixed-methods approach, harnessing the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative research techniques. Quantitative survey data about session frequency and communication platforms provide a broad overview of the programme’s logistics. Meanwhile, qualitative insights offer a deeper understanding of student perceptions and personal experiences. The combination of these methods enables data triangulation, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of our findings (Dörnyei Citation2007). This triangulation aligns with our study’s objectives to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of OIE in the contexts of language learning, as well as intercultural and international education.

Data analysis

Our analysis centres on the research question indicated at the outset: how have students’ perceptions of the benefits of internationalisation through OIE shifted from the pre-pandemic to the pandemic period? We examined both quantitative and qualitative data to assess student engagement and learning outcomes within the OIE programme. Student engagement, which is closely linked to motivation, is defined as sustained behavioural involvement in learning activities, accompanied by positive emotional and cognitive states (Skinner and Belmont Citation1993: 572). This focus stems from well-supported evidence that engagement is pivotal to student learning and its absence is detrimental (e.g. Carini et al. Citation2006). We maintain that student engagement and learning outcomes are interrelated, playing a crucial role in shaping students’ experiences of the OIE programme and their perceptions of its benefits.

Our analysis of student engagement focused on three dimensions: (1) ‘behavioural engagement’, evaluated through the frequency and duration of student participation; (2) ‘emotional engagement’, gauged by students’ emotional connections with partners, including feelings of interest, boredom, happiness or anxiety; and (3) ‘cognitive engagement’, characterised by students’ strategic, critical approach and a keen interest in learning the target language and culture (Wang and Eccles Citation2012). For learning outcomes, we concentrated on three areas highlighted in the survey data: (1) intercultural awareness; (2) target language skills and motivation; and (3) interpersonal relationships.

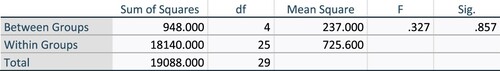

We employed SPSS version 27 for the analysis of quantitative data, specifically using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate relevant data pertaining to student behavioural engagement. For our study’s qualitative component, we conducted thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke (Citation2016) to identify key patterns and themes related to emotional and cognitive engagement and learning outcomes. This process involved each author conducting an individual review of the transcripts from participants’ survey comments to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the data. This was followed by joint discussions to collaboratively and inductively develop a list of themes. This method enabled a detailed and nuanced analysis of the qualitative data, ensuring that it accurately reflected student experiences. The selected quotes in what follows exemplify the identified themes and showcase specific participant experiences.

Findings

Student engagement

This section explores aspects of student engagement, focusing on behavioural, emotional and cognitive dimensions. The total number of participants engaged in the programme almost doubled between 2019 and 2020. Our analysis of quantitative data on the frequency of OIE sessions per pair (see question 1 in Appendix), however, shows no significant increase in behavioural engagement during the pandemic. However, our survey data, both qualitative and quantitative, covering overall OIE experiences, successful aspects and media usage (see questions 7, 10, 14 and 19 in Appendix), demonstrate enhancements in emotional and cognitive engagement within the OIE programme during the pandemic years (2020, 2021 and 2022) compared to the pre-pandemic period (2018 and 2019).

1. Behavioural engagement

A key indicator of heightened student engagement between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods is the notable increase in participants, which surged from 227 in 2019 to 456 in 2020. However, participant numbers dropped sharply to 171 in 2022 as face-to-face sessions resumed. Despite this decline, there has been a gradual recovery, with numbers rising to 174 in 2023. The significant growth from 2019 to 2020 likely signifies enhanced behavioural engagement at a programmatic level, reflecting a marked rise in interest in the OIE programme. Nevertheless, this increase may not necessarily indicate heightened engagement during individual sessions. To evaluate session-specific engagement, we analysed the frequency of OIE sessions per pair (refer to question 1 in Appendix), and our findings indicate no significant changes. Consistently, the number of OIE sessions held by Australian and Japanese university students remained stable both before the pandemic (2018–2019) and during the pandemic (2020–2022) periods (see ). A One-Way ANOVA, used to compare the means of independent groups to determine if at least two group means (in this case, ‘pre-pandemic’ years and ‘pandemic’ years) are significantly different, yielded an F-value of 0.327 and a p-value of 0.857, suggesting no substantial variation in OIE session frequency even during the pandemic. Moreover, session durations were consistently about one hour, both pre-pandemic and during the pandemic (refer to question 2 in Appendix). This indicates that although more students participated in the programme during the pandemic, the level of active involvement per session did not correspondingly increase. Nevertheless, it implies that the pandemic did not disrupt the regularity of interactions, reflecting the resilience and adaptability of the OIE framework. Further analysis is required to distinguish between overall programme engagement and specific session engagement, and to explore the factors influencing each type of engagement.

Figure 1. The frequency of OIE sessions organised among participants during the pre-pandemic years (2018–2019) and throughout the pandemic years (2020–2022).

2. Emotional engagement

Emotional engagement in this study is defined by the emotional connections students form with their partners, characterised by feelings of interest, boredom, happiness or anxiety. We examined shifts in participants’ emotional engagement from the pre-pandemic period (2018−2019) to the pandemic period (2020−2022), focusing particularly on Semester 1 of 2020. Our qualitative data, sourced from the final open-ended question of our survey on overall OIE experiences (see question 19 in Appendix), indicates that not all but some participants from both universities reported deeper emotional connections with their session partners during this semester compared to any previously examined periods. It is important to note that the participants did not attend the sessions consecutively, which means that they had no prior knowledge of their partners. Despite this, they expressed positive emotions, indicating a significant level of emotional engagement within a single semester. Below are illustrative comments from participants that highlight this shift in emotional engagement:

Due to the pandemic, it became difficult to make friends and the opportunities to talk to people were absolutely reduced, so I was very happy that I could make friends [from the Australian university] through this programme. In my case, we met once a week and I was able to talk about things that happened that week, vent frustrations and discuss our respective future prospects. It was a lot of fun.

It was very exciting and enjoyable to be able to talk with my Australian friends at home during the stay-at-home orders due to the coronavirus.

I was happy to make a friend abroad [in Australia]. I definitely want to meet them in person once the coronavirus situation settles down.

During the periods of self-isolation, this programme was a lifeline. My spirits lifted every time I met with my [Japanese] partner.

I’m really happy that I signed up for this programme, and I feel very lucky to have made a new friend [from the Japanese university], especially during the COVID-19 lockdown/self-isolation period. In our last session, we said that if we ever meet each other, we will get bubble tea together.

Further, in the survey conducted during Semester 2, 2019, 73.33% of participants from the Australian university and 71.2% from the Japanese university expressed a desire to meet their session partners in person if given the opportunity. By Semester 1, 2020, these percentages had increased to 91.9% and 86.5%, respectively (see question 13 in Appendix). This increase suggests that the sessions during the pandemic not only maintained engagement but also deepened the participants’ sense of partnership, reflecting a strengthened desire to meet in person.

3. Cognitive engagement

Our qualitative data, collected from open-ended survey questions about overall OIE experiences (refer to questions 9, 10 and 19 in Appendix), demonstrates that shared issues and challenges can enhance cognitive engagement in the OIE programme. This effect was particularly pronounced during the pandemic. Despite the constraints the pandemic imposed, some students actively engaged in discussions about current events which had sparked their interest, including those related to COVID-19. The way this engagement enriched their conversations and deepened their understanding of cultural differences and global challenges is most vividly illustrated by the reflections of an Australian university student on their Semester 1, 2021 OIE experience, as shared below:

I feel that I have gained a deeper insight into Japanese culture and into the life of a Japanese university student. It has been really interesting discussing our lives and our cultures and being able to share that. Particularly with the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, we have both been able to learn about how another country is handling it.

Students initiated the use of digital media such as YouTube videos and online video games through Zoom’s ‘share’ function, alongside utilising LINE and Instagram for exchanging photos and videos outside of sessions. For example, some Australian students integrated online shōgi (Japanese chess) and other games into their sessions, noting improved communication and reduced awkward silences. This trend since 2020 underscores how technological advancements during the pandemic have spurred students to leverage multimodal tools, fostering more diverse engagement with their partners and purposefully enhancing online communication.

4. Challenges to engagement

Although this section primarily focuses on shifts in student engagement, the study also reveals how the pandemic introduced new challenges. Based on responses to an open-ended qualitative survey question about unsatisfactory aspects of the exchange (see question 10 in Appendix), challenges before the pandemic predominantly involved mismatches in language proficiency levels and interests, along with scheduling conflicts and technological issues like internet connectivity. While these challenges persisted, the pandemic also brought new difficulties related to student (im)mobility. A notable example is that international students at the Australian university, especially those returning to mainland China, faced access difficulties due to government restrictions distinctive to the pandemic period. These challenges provide some insights for reassessing the digital frameworks of both IaH and IaD.

The impact of OIE on student learning outcomes

Leveraging insights from studies highlighting OIE’s benefits in boosting language skills and intercultural competence (Kern et al. Citation2022; Lewis and O’Dowd Citation2016; O’Dowd Citation2017; Potolia and Derivry-Plard Citation2023; Skidmore Citation2023), our study reinforces these positive impacts, focusing on (1) intercultural awareness; (2) target language skills and motivation; and (3) interpersonal relationships. Notably, participants reported enhanced benefits from the OIE programme during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period.

1. Intercultural awareness

As shown in , both pre-pandemic and during the pandemic, ‘understanding of different cultures’ was the most widely perceived gain from the OIE programme. During the pandemic years, there was a notable increase in the number of students highlighting this gain. In 2020, 76.6% of all participants (both from Monash University and from Waseda University) indicated that they gained a better understanding of each other’s cultures. This figure represents a substantial increase compared to 47.6% in 2019.

Table 1. Aggregate responses indicating what participants believe they gained from the OIE programme from 2018 to 2022.

Furthermore, survey results from the Australian university reveal a significant increase in the positive impact of the OIE programme on participants’ understanding of Japanese culture and the life of a Japanese university student. In 2020, 82.2% of participants reported this, rising to 84% in 2021, compared to 62.8% in 2018 and 24.6% in 2019.

This noticeable increase in reported understanding of both other and own cultures in 2020 and 2021 is corroborated by qualitative data from questions 9, 18 and 19, which include the following comment from a Japanese university student participating in the Semester 1, 2021 OIE programme:

It was also interesting who I’d be matched up with and what country they would be from. My partner was from Hong Kong, and it was due to this that I was able to broaden my world outlook by watching news about China and Hong Kong and I began to take an interest in the events surrounding it as if they were happening in my own country.

2. Target language skills and motivation

Quantitative data from survey questions 11 and 12 in this study indicate that OIE provided valuable opportunities not only for intercultural connections and understanding but also for the enhancement of practical language learning skills. During the pandemic, students reported notable improvements in key language skills, specifically listening and speaking. The data show that these improvements averaged 24.65% during the 2018 and 2019 period and increased significantly to an average of 40.9% from 2020 to 2022, as detailed in .

Moreover, the quantitative and qualitative data from survey questions 9, 11, 18 and 19 indicate a shift in participants’ motivation and future study plans. As shown in , there was a significant increase in motivation to study abroad post-2020, with figures rising from 9.9% in 2018 and 17.9% in 2019 to over 30% in the subsequent three years, especially among Australian students. This shift suggests that OIE experiences during the pandemic changed language learning from a theoretical academic pursuit into development of a practical communicative tool. While pre-pandemic surveys only touched fleetingly on motivational aspects, comments from 2020 reflect a deeper appreciation for how online exchanges directly motivated participants to continue learning Japanese.

Although there is no quantitative data available, qualitative data from survey questions 9, 18 and 19 indicate that boosted motivation to learn the target language may have been enhanced by participants' cultural understanding, confidence and speaking practice with their partners. This is indicated by responses from both Australian and Japanese university participants in 2020, with individuals commenting: ‘It really helped me gain more confidence to speak more and improve my Japanese’, and ‘My comprehension and speaking skills improved significantly, as well as my general confidence with the Japanese language’. A Japanese university student in 2021 remarked: ‘Although my language skills didn’t improve significantly, I was able to lower the hurdle of speaking English with a native speaker’. Prior to the pandemic, confidence was not highlighted as a learning outcome in the OIE survey results.

3. Interpersonal relationships

The OIE experiences during the pandemic also impacted the formation and maintenance of interpersonal relationships. Data from survey question 11, detailed in , shows a notable increase in the number of participants reporting that they ‘made a friend’ through the OIE programme, with figures rising from 39.6% in 2019 to 62.4% in 2020 and 59.8% in 2021. Participants highlighted the development of new friendships, an aspect of the programme that was particularly valued during the challenging times of lockdown and self-isolation. Comments from Australian participants in Semester 1, 2020 provide further insight into the positive impact of these connections:

I think due to the lockdown I was able to interact more with my partner and since we get along well, I hope it means we can stay in touch in the future!

This is one of the most valuable cultural experiences I’ve ever gained. The connection built upon the internet with someone with a totally different geographic and cultural background surprised me. My partner and I meet every week for an approximately one hour-long skype. We always can think of a new interesting topic to dive right in. We have gradually become closer and shared more personal insights, which has motivated me to love studying more of this language. Thanks so much for developing this programme.

Discussion and conclusion

Our study situates OIE within the frameworks of IaH and IaD, providing insights into its potential as a model that addresses the diverse needs of a student body transcending the traditional dichotomy of ‘home’ and ‘abroad’. Traditionally, OIE and other virtual exchange programmes have been viewed as supplemental to physical study abroad programmes (Lewis and O’Dowd Citation2016). However, the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside the ongoing diversification of learning environments, have prompted a reevaluation of OIE’s role and benefits. Our research suggests that OIE could serve as a vital component in higher education’s internationalisation efforts. Through our analysis of students’ self-reported experiences in the OIE programme via online surveys, we found that the programme offered valuable language and intercultural learning opportunities that positively influenced their engagement and outcomes. Remarkably, our data suggests that the pandemic actually facilitated, rather than hindered, student engagement at both cognitive and emotional levels, leading to enhanced learning outcomes.

The notable surge in participants from 227 in 2019 to 456 in 2020 serves as a significant indicator of increased student engagement between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. Despite no significant increase in the frequency of OIE sessions, consistent participation from 2018 to 2022 underscores the programme’s sustained relevance. One-Way ANOVA results confirm that the pandemic did not disrupt the regularity of interactions, reflecting the resilience and adaptability of the OIE framework. The pandemic enhanced emotional engagement, with students forming deeper emotional connections and expressing feelings of happiness, excitement and emotional support. Participants’ narratives reveal that OIE provided a critical lifeline for social interaction and emotional support amid severe mobility restrictions, highlighting the programme’s importance in fostering positive emotional experiences during challenging times. Cognitive engagement also saw notable increases, with students engaging in meaningful discussions about cultural values, traditions and intercultural aspects. This engagement often led to enhanced intercultural sensitivity, aligning with the principles of IaH and IaD. The effective use of digital tools, especially the transition to platforms like Zoom, further enriched cognitive engagement, allowing for multimodal and multilingual interactions.

Our study demonstrates the positive impacts of OIE on intercultural awareness, language skills, motivation and interpersonal relationships, serving as indicators of learning outcomes. Participants reported enhanced benefits during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period in these aspects. Understanding diverse cultures emerged as the most prominent gain, with a considerable increase in students highlighting this benefit during the pandemic. Moreover, participants reported improvements in speaking and listening skills, alongside a heightened interest in studying abroad. In addition, OIE experiences during the pandemic notably influenced the formation and maintenance of interpersonal bonds, with a significant increase in participants forming positive emotional connections and friendships, particularly valued during lockdowns and periods of self-isolation.

These findings underscore the potential benefits of incorporating OIE into higher education curricula, not merely as a temporary solution to student (im)mobility but also as a distinctive educational strategy that physical exchange programmes may not replicate. Our study suggests that OIE has the capacity to expand international opportunities beyond conventional ‘home’ and ‘abroad’ distinctions, fostering a more inclusive academic environment that addresses the diverse needs of students. By effectively implementing OIE, universities can advocate for a more inclusive model of international education, ensuring that all students have access to meaningful intercultural exchanges, regardless of their physical mobility limitations (Lewis and O’Dowd Citation2016). This perspective aligns closely with the IaH and IaD frameworks, both of which utilise technology to overcome physical barriers, although the latter emphasises a broader scope of inclusivity than the former.

The findings of our study highlight several key factors supporting this perspective. Firstly, the OIE programme leverages online platforms to enable consistent intercultural interactions, ensuring the continuity and potential expansion of international education even during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. The significant increase in participant numbers during the pandemic illustrates the programme’s effectiveness in maintaining student engagement. Crucially, this indicates that the programme provides international learning experiences to students who face mobility constraints or lack the financial means for traditional study abroad programmes, thereby broadening access to intercultural and international education. Our study also demonstrates that the formation and maintenance of interpersonal bonds through these sessions significantly increase students’ motivation to visit each other’s locations for physical interactions in the future. This process is typically unavailable through traditional methods of international education, where students often need to form relationships on-site without prior interaction opportunities, limiting their ability to deepen bonds within a constrained timeframe. Finally, the increased use of multimodal communication in OIE during the pandemic, including text, video and interactive media, is notable. This approach allows students to explore and design different learning styles that cater to their needs, enhancing their sense of ownership and engagement in the sessions. This aspect of OIE is unique compared to traditional educational settings, where the methods of language learning are often determined by educators. By reimagining these potential benefits of OIE, universities can offer flexible, consistent and meaningful internationalisation opportunities that respond to the complex and diverse realities of a globally connected student body.

While our study highlights the benefits of OIE, it also reveals several limitations in the approach, although a comprehensive examination of these is beyond our scope. The pandemic introduced new challenges, such as accessibility issues due to government restrictions. These insights highlight the need for continuous improvement in digital frameworks supporting IaH and IaD.

To build on these findings, further investigation is needed into the long-term impacts of OIE on student engagement and intercultural competence across a broader geographical range of institutions and participants. Moreover, this study’s scope is limited to student perceptions of the benefits of OIE. Future research would benefit from objective measurements of OIE’s effectiveness, as well as insights from educators, coordinators, support members and other stakeholders involved in the development and implementation of OIE programmes. Research should also explore effective strategies for integrating OIE into educational practices and curricula holistically, examining how OIE influences curriculum design, teaching methodologies, faculty development and strategic institutional planning.

Ethics approval details

The name of the ethics committee – Monash University Human Research Ethics Committees. The respective institution – Monash University. The project ID – 30513.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Intercultural Communication Center at Waseda University for generously allowing us to utilise the data collected from the programme participants. Our heartfelt appreciation goes to the OIE project team members, including Nadine Normand-Marconnet (Chief Investigator; listed in alphabetical order hereinafter), Howard Manns, Jeremy Breaden, Linh Nguyen, Lola Sundin, Lucas Moreira dos Anjos Santos, Shani Tobias and Thu Do, for their invaluable contributions to this study. We would also like to acknowledge the support provided by our research assistant, Eliza Nicoll.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akasaki, M. 2021. Onrain jugyō no kadai to kanōsei - Ibunka komyunikēshon no shiten kara [Challenges and possibilities of online classes: from the perspective of intercultural communication]. Ibunka Komyunikēshon Ronshū [Journal of Intercultural Communication Studies] 19: 109–119.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2023. International trade in goods and services, Australia. 7 March 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/international-trade-goods-and-services-australia/latest-release.

- Australian Government. 2016. National strategy for international education 2025. https://protect-au.mimecast.com/s/qohgCgZolKFAwXQDoF328J6?domain=nsie.education.gov.au.

- Beelen, J., and E. Jones. 2015. Redefining internationalization at home. In The European Higher Education Area: Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies, eds. A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, and P. Scott, 59–72. Cham: Springer.

- Bower, J., and S. Kawaguchi. 2011. Negotiation of meaning and corrective feedback in Japanese/English E-tandem. Language Learning & Technology 15, no. 1: 41–71. http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2011/bowerkawaguchi.pdf.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2: 77–101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Breaden, J., T. Do, L. Moreira dos Anjos-Santos, and N. Normand-Marconnet. 2023. Student empowerment for internationalisation at a distance: enacting the students as partners approach in virtual mobility. Higher Education Research & Development 42, no. 5: 1182–1196. DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2023.2193728.

- Carini, R.M., G.D. Kuh, and S.P. Klein. 2006. Student engagement and student learning: testing the linkages*. Research in Higher Education 47, no. 1: 1–32. DOI: 10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9.

- Cook-Sather, A., C. Bovill, and P. Felten. 2014. Engaging Students As Partners in Learning and Teaching: A Guide for Faculty. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- Crowther, P., M. Joris, M. Otten, B. Nilsson, H. Teekens, and B. Wächter. 2000. Internationalisation at home: a position paper. Amsterdam: European Association for International Education. https://www.univ-catholille.fr/sites/default/files/Internationalisation-at-Home-A-Position-Paper.pdf.

- Department of Home Affairs. 2023. Visa statistics. 31 March 2023. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-statistics/statistics/visa-statistics/study.

- De Wit, H. 2016. Internationalisation and the role of online intercultural exchange. In Online Intercultural Exchange: Policy, Pedagogy, Practice, eds. Robert O’Dowd, and T. Lewis, 69–82. New York, NY: Routledge.

- De Wit, H., and P.G. Altbach. 2021. Internationalization in higher education: global trends and recommendations for its future. Policy Reviews in Higher Education 5, no. 1: 28–46. DOI: 10.1080/23322969.2020.1820898.

- Dörnyei, Z. 2007. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Drane, C., L. Vernon, and S. O’Shea. 2020. The impact of ‘learning at home’ on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NCSEHE_V2_Final_literaturereview-learningathome-covid19-final_30042020.pdf.

- Gravett, K., I.M. Kinchin, and N.E. Winstone. 2020. ‘More than customers’: conceptions of students as partners held by students, staff, and institutional leaders. Studies in Higher Education 45, no. 12: 2574–2587. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1623769.

- Harrison, N. 2015. Practice, problems and power in ‘internationalisation at home’: critical reflections on recent research evidence. Teaching in Higher Education 20, no. 4: 412–430. DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2015.1022147.

- Huang, F., D. Crăciun, and H. Wit. 2022. Internationalization of higher education in a post-pandemic world: challenges and responses. Higher Education Quarterly 76, no. 2: 203–212. DOI: 10.1111/hequ.12392.

- Hudzik, John K. 2015. Comprehensive Internationalization: Institutional Pathways to Success. International in Higher Education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ikeda, K. 2016. A discussion based on COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning) practice in Japan. JASSO 67, no. 10: 1–11.

- Ikeda, K. 2022. Emergence of COIL as online international education before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Language Education and Applied Linguistics 12, no. 1: 1–5. DOI: 10.15282/ijleal.v12i1.7616.

- Iwaki, N. 2012. Ryūgaku Suishin no Torikumi ga Kōkan Ryūgaku ni Ataeru Eikyō ni Tsuite no Jittai Chōsa [A survey on the impact of study abroad promotion efforts on exchange programmes]. Nagoya University International Student Center Bulletin 10: 23–29.

- Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO). 2021. The summary of results on an annual survey of international students in Japan 2020. March 2021. https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/statistics/zaiseki/data/2020.html.

- Kern, R., A.J. Liddicoat, and G. Zarate. 2022. Research perspectives on virtual intercultural exchange in language education. In Virtual Exchange for Intercultural Language Learning and Teaching: Fostering Communication for the Digital Age, eds. A. Potolia, and M. Derivry-Plard, 1–20. New York: Routledge.

- Knight, J. 2008. Higher Education in Turmoil: The Changing World of Internationalisation. Global Perspectives on Higher Education 13. Rotterdam and Taipei: Sense Publishers.

- Kokurisu Daigaku Kyōkai. 2021. Koronaka wo Keiki toshite Kangaeru Kongo no Kokusai.

- Konishi, M. 2021. Bideo chatto de no ītandemu onrain kokusai kōryū ni okeru komyunikēshon no tame no kyōdō [Collaboration for communication in E-tandem online international exchanges via video chat]. Gaikokugo Kyōiku Media Gakkai Kikan-shi [Journal of the Association for Foreign Language Education Media] 58: 43–67.

- Lewis, T., and R. O’Dowd. 2016. Introduction to online intercultural exchange and this volume . In Online Intercultural Exchange: Policy, Pedagogy, Practice, eds. R. O’Dowd, and T. Lewis, 3–20. New York: Routledge.

- Mason, A., F. Robert, A. Webb, A.M. Siega, A.K. Mazlin, and L.M.C. Jamie. 2024. Sustainable internationalisation through collaborative online intercultural learning. In Sustainability in Business Education, Research and Practices, eds. T. Wall, L. Viera Trevisan, W. Leal Filho, and A. Shore. Switzerland: 195–208. Springer Nature. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-55996-9_13.

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. n.d.a. Inter-university exchange project. https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/highered/title02/detail02/sdetail02/1373893.htm (accessed April 22, 2024).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. n.d.b. Top global university project. https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/highered/title02/detail02/sdetail02/1395420.htm ((accessed April 22, 2024).

- Mittelmeier, J., B. Rienties, J. Rogaten, A. Gunter, and P. Raghuram. 2019. Internationalisation at a distance and at home: academic and social adjustment in a South African distance learning context. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 72: 1–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.06.001.

- Nakahashi, M. 2022. Implementation and challenges of online international exchange under the COVID-19 pandemic. Gurōbaru jinzai ikusei kyōiku kenkyū [Global Human Resource Development Education Research] 10, no. 1: 47–59.

- Normand-Marconnet, N., J. Breaden, and T. Do. 2022. Partnering with students: a win-win strategy in virtual mobility. Monash Lens, 10 October 2022. https://lens.monash.edu/education/2022/10/10/1385091/partnering-with-students-a-win-win-strategy-in-virtual-mobility.

- Normand-Marconnet, N., J. Breaden, T. Do, and L. Santos. 2024. Boosting students’ global competence through virtual exchange. Monash Teaching Community, 9 April 2024. https://teaching-community.monash.edu/virtual_exchange/.

- O’Dowd, R. 2017. Online intercultural exchange and language education. In Language, Education and Technology, eds. S.L. Thorne, and S. May, 207–218. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- O’Dowd, R. 2021. Virtual exchange: moving forward into the next decade. Computer Assisted Language Learning 34, no. 3: 209–224. DOI: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1902201.

- O’Dowd, R. 2023. Internationalising Higher Education and the Role of Virtual Exchange. New York: Routledge.

- Pasfield-Neofitou, S. 2011. Online domains of language use: second language learners’ experiences of virtual community and foreignness. Language Learning & Technology 15, no. 2: 92–108. http://llt.msu.edu/issues/june2011/pasfieldneofitou.pdf.

- Potolia, A., and M. Derivry-Plard. 2023. Virtual Exchange for Intercultural Language Learning and Teaching: Fostering Communication for the Digital Age. Milton: Routledge.

- Rizvi, F. 2020. Reimagining recovery for a more robust internationalization. Higher Education Research & Development 39, no. 7: 1313–1316. DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1823325.

- Rubin, J. 2016. The collaborative online international learning network online intercultural exchange in the State University of New York Network of Universities. In Online Intercultural Exchange: Policy, Pedagogy, Practice, eds. Robert O’Dowd, and Tim Lewis, 236–272. New York: Routledge.

- Shimmi, Y., H. Ota, and A. Hoshino. 2021. Internationalization of Japanese universities in the COVID-19 era. International Higher Education 107: 39–40. https://www.internationalhighereducation.net/api-v1/article/!/action/getPdfOfArticle/articleID/3259/productID/29/filename/article-id-3259.pdf.

- Skidmore, M. 2023. Effects of participation in an online intercultural exchange on drivers of L2 learning motivation. Language Teaching Research 27: 136216882311536. DOI: 10.1177/13621688231153622.

- Skinner, E.A., and M.J. Belmont. 1993. Motivation in the classroom: reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology 85, no. 4: 571–581. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571.

- Stevens Initiative. n.d. About us. https://www.stevensinitiative.org/about-us/ (accessed May 9, 2023).

- Stockwell, G., and M. Levy. 2001. Sustainability of e-mail interactions between native speakers and nonnative speakers. Computer Assisted Language Learning 14, no. 5: 419–442. DOI: 10.1076/call.14.5.469.5770.001.

- SUNY COIL. n.d. The SUNY COIL Center. https://coil.suny.edu/about-suny-coil/ (accessed October 28, 2023).

- Tajima, M., and N. Fukui. 2022. The significance of crossing the boundaries: a case study of an online student exchange project between Ibaraki University and UNSW, Sydney. Journal of Liberal Arts Education 5: 93–108. Institute for Liberal Arts Education, Ibaraki University.

- Takei, M., M. Fujiwara, and M. Shimojo. 2021. Online conversation project between universities in Japan and the US: its rationale and design for integrating research and pedagogy. Hiroshima Shūdai Ronbun Shū [Hiroshima Shūdo University Journal] 61, no. 1: 1–23.

- Toyoda, E., and R. Harrison. 2002. Categorization of text chat communication between learners and native speakers of Japanese. Language Learning and Technology 6, no. 1: 82–99. DOI: 10125/25144.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2019. Inbound internationally mobile students by continent of origin. http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3804.

- UNICollaboration. n.d. Home. https://www.unicollaboration.org/ (accessed May 9, 2023).

- Universities Australia. 2022. Data snapshot. June 2022. http://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/publication/data-snapshot-2022/.

- Wang, M.-T., and J.S. Eccles. 2012. Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. Journal of Research on Adolescence 22, no. 1: 31–39. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00753.x.

- Weinmann, M., R. Neilsen, and C. C. Benalcázar. 2024. Languaging and language awareness in the global age 2020–2023: digital engagement and practice in language teaching and learning in (post-)pandemic times. Language Awareness 33, no. 2: 347–364. DOI: 10.1080/09658416.2023.2236025.

- Yonezawa, A., H. Ota, K. Ikeda, Y. Yonezawa, et al. 2023. Transformation of international university education through digitalisation during/after the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges in online international learning in Japanese universities. In The Impact of Covid-19 on the Institutional Fabric of Higher Education: Old Patterns, New Dynamics, and Changing Rules?, ed. Rómuldo Pinheiro, 173–198. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.