Abstract

This article builds on the most recent work done on ekphrasis in contemporary fiction and explores its capacities to blur the boundary between visual art and life writing. Since ekphrasis can contest the border of the work of art, this article also draws from Derrida's notion of the parergon (1987). Ekphrasis is most commonly understood as the ‘verbal representation of a visual representation’ (Heffernan 1993), while the parergon captures the ambiguous, ‘ornamental’ frame that separates the artwork from the world beyond it. By focusing on Amy Sackville's Painter to the King (2018) and Laura Cumming's The Vanishing Man (2016), two books that use Diego Velázquez's painting Las Meninas (1656) to frame their life narratives, this article shows how ekphrasis can act as a discursive parergon that challenges the borders between art and life, fact and fiction, literature and painting, and inside and outside. These empathetic life narratives—of a Spanish painter and a Victorian bookseller respectively—emulate Velázquez's visual techniques and implicate the reader, who is turned into a quasi-eyewitness through ekphrasis, within their meaning-making structures. In both instances, the enchanting spell of Velázquez's painting is used to push these life narratives into the realm of the imagination.

Introduction: Beholding Las Meninas (1656)

In the centre of Diego Velázquez's Las Meninas (1656) is the five-year-old Infanta Margaret Theresa of Spain, who will one day grow up to marry the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I (see ). Flooded in light, the princess is framed by her two ladies in waiting, María Agustina Sarmiento de Sotomayor on the left and Isabel de Velasco on the right, after whom the painting was named in 1843.Footnote1 Above them, a rectangular mirror reflects the figures of the Infanta's parents: King Philip IV of Spain and his second wife, Queen Mariana of Austria. To the right of the mirror and standing in the illuminated doorframe is José Nieto Velazquez, the queen's chamberlain. Finally, positioned to the left of the mirror is the painter himself, hovering in front of the mysterious canvas as if he is just about to lean in to make another mark or just about to lean away to look at his work.

Figure 1. Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656, oil on canvas, 318 cm × 276 cm, credit: Editorial copyright ©Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado.

This rigid yet lively composition is marked by numerous frames, most notably by the frame around Velázquez's canvas on the far left and around the two paintings by Rubens that hang on the back wall, supplementing this seventeenth-century cast of characters with Ovid's myths. As a painting about painting, Las Meninas shares similarities with Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (1434) and Johannes Vermeer's The Art of Painting (c. 1666). In these three paintings, the artists enter their creations to stage a moment of self-inspection. Like Carel Fabritius's The Goldfinch (1654), which was painted merely two years before Las Meninas and which survived a gunpowder explosion in Delft, Velázquez's painting was pulled from the flames when the Alcázar burned in 1734 and narrowly escaped being lost forever. Today it is one of the most treasured art objects in the world and the subject for an infinite series of re-adaptations.

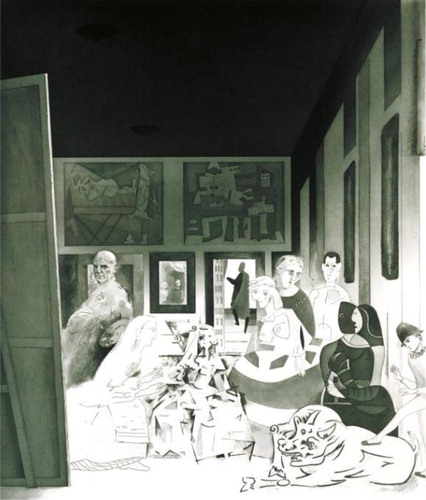

Within art history itself, the phantasmagoric nature and importance of Las Meninas can be traced paradigmatically through Pablo Picasso and Richard Hamilton. In 1957, Picasso began a series of forty-four paintings based on Las Meninas, attempting to finally understand the captivating qualities of the artwork he had loved since his childhood. His take on the Infanta (see ), for example, reworks Velázquez's angelic princess into an abstract icon of modernity. Picasso's admiration of Las Meninas and his attempts to unlock its mysteries by translating it into his own style was carried on by Hamilton, who in turn tried to comprehend Picasso via Las Meninas. In Picasso's Meninas (1973), an etching commissioned to celebrate Picasso's ninetieth birthday, Hamilton uses Velázquez's composition but redraws each of the seventeenth-century characters in one of Picasso's different styles (see ). For example, the Infanta is represented in an Analytical Cubist manner while the dog in the bottom right corner is drawn as one of Picasso's dying bulls. The most crucial change is the substitution of Velázquez by a realistic drawing of Picasso: ‘The subjects of the original painting […] have been transformed into the entourage of Picasso’ (Tate website). Hamilton's etching acknowledges that Picasso's efforts to discern Las Meninas have created its own cultural legacy, just as his response to Picasso's response to Velázquez has done. Similar to the endlessly readapted Mona Lisa, Las Meninas serves as an infinite well of inspiration for and even beyond the visual arts.

Figure 2. Pablo Picasso, Las Meninas (Infanta Margarita María), 1957, oil on canvas, 100×81 cm, Museu Picasso, credit: © Succession Picasso / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich.

Figure 3. Richard Hamilton, Picasso's Meninas, 1973, etching on paper, 57×49 cm, Tate collection, credit: Photo @ Tate. © R. Hamilton. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2021.

Even though a plethora of books and articles have been written about Velázquez's painting, this artwork famously escapes all monolithic interpretations. Perhaps the best-known reading of Las Meninas can be found in Michel Foucault's The Order of Things (1966; English transl. 1970), in which he focuses on the painting's composition of restricting frames and transgressing gazes. Foucault claims that the triangulation of the king, the painter and the observer, whose shared position is indicated by the mirror and reinforced by the gaze, constantly destabilizes these binary pairs. These three figures ‘come together in a point exterior to the picture: that is, an ideal point in relation to what is represented, but a perfectly real one too, since it is also the starting-point that makes the representation possible’ (Foucault, Order 16). Foucault's complex analysis of the gaze-topos reveals the painting's interplay between presence and absence, the visible and invisible, the observable and the hidden, the spectator and the model, the centre and the margin, and the represented and the representation. These binaries carry the signification of power and powerlessness in Foucault's theory of knowledge, which he elaborates in Discipline and Punish (1975). It is not only the superimposition of artist, sovereign and spectator that is important, but also the fact that they are outside of the picture. Since that which is being represented is absent, Foucault argues, Las Meninas is about representation itself:

But there, in the midst of this dispersion which it is simultaneously grouping together and spreading out before us, indicated compellingly from every side, is an essential void: the necessary disappearance of that which is its foundation – of the person it resembles and the person in whose eyes it is only a resemblance. This very subject – which is the same – has been elided. And representation, freed finally from the relation that was impeding it, can offer itself as representation in its pure form. (Foucault, Order 17–18)

The art critic Svetlana Alpers hypothesizes that disciplinary organizations make ‘picture[s] such as Las Meninas literally unthinkable under the rubric of art history’, which is why writers attuned to text have delivered the most meaningful contributions to the study of this painting (Alpers 30). Two contemporary discursive responses to Las Meninas, which support Alpers’ point, are Amy Sackville's biofiction Painter to the King (2018) and Laura Cumming's non-fictional The Vanishing Man (2016). Both authors employ Las Meninas to tell the life narratives of the seventeenth-century painter, Diego Velázquez, and the nineteenth-century Velázquez admirer, John Snare, respectively.Footnote2 Like John Ashbery's postmodern poem ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ (1973), which builds on the mirrored and distorted self in Parmigianino's eponymous painting (c. 1524), Sackville and Cumming use Las Meninas as a source of inspiration to generate life narratives and to meditate on art, affect and constructions of self. Through ekphrasis—a verbal response to visual art—they conjure Las Meninas at the beginning and end of their narratives. Moreover, they parallel the painting's emphasis on frames (created by architecture, the edges of canvases, the mirror, and character constellations) with literary form: in both works, Las Meninas acts as a frame narration to encompass mise-en-abyme-like stories-within-stories. Both works thus harness the painting's genre-plurality as ‘a royal portrait, a genre painting and a self-portrait’ for the stories they tell and the characters they portray (Finaldi n. pag.). Since Las Meninas is commonly viewed as a metaphor for self-reflexive representation, its centrality in Sackville's and Cumming's books suggests that these texts are not only interested in the lives they narrate, but also in narration itself. They are fundamentally metafictional texts that reflect on their own poetics.

Crucially, the complexities of signification in Las Meninas, with which Picasso, Hamilton and others have grappled, are transferred into and multiplied within these texts. Since ekphrasis invites readers to ‘“see” the subject in their mind's eye’ (Webb 2) by halting the narration to emphasize the presence of the rendered artwork to the seeing eye/evoking I (Cunningham 60–61), readers are further entangled in the texts’ meaning-making processes. Both the actual painting and the mode of ekphrasis thus work together to turn readers into co-producers of meaning and to complicate the borders between art and life, literature and painting, self and other.

Theoretical Background: Ekphrasis and the Frame

Given its long tradition that dates back to Homer's description of Achilles’ shield, today's ekphrasis comes in various shapes and forms. Theoretically speaking, ekphrasis is best known as ‘the verbal representation of a visual representation’ (Heffernan 3). While its beginnings lie in Greek and Roman Antiquity, this mode of speaking and writing has been proliferating in literature and scholarship since the late 1980s with the transition into the digital age and the emergence of intermediality studies. As a dynamic form of description, ekphrasis is a literary response to visual art that can produce form- and content-related patterns throughout a text. It is a discursive intervention that breaks the ‘pregnant’ silence of the artwork (German prägnant; Lessing 78), or, to put it in James Heffernan's words, it ‘typically delivers from the pregnant moment of visual art its embryonically narrative impulse, and thus makes explicit the story that visual art tells only by implication’ (5). In doing so, ekphrasis doubles, re-actualizes and challenges the painting's visually encoded semantics with words and creates an intermedial version of retelling. Such meditations on ekphrasis as an original ‘repetition’ are close to other theoretical concepts such as adaptation, remediation, translation, quotation, and more (Rippl 2015).Footnote3

Sometimes this medial contact in ekphrasis is viewed as a competition or in Italian a paragone. Indeed, the approach to ekphrasis as a literary tool to stage and unveil power structures with the medial ‘other’ is an important critical tradition and counts scholars such as W. J. T. Mitchell (1994) and David Kennedy (2012) amongst its proponents. This staging of conflict is only one ekphrastic function among numerous others (cf. Louvel 2011 and 2018). Its diverse uses were recently discussed in a special issue of Poetics Today on ‘Contemporary Ekphrasis’ (2018), in which Renate Brosch argues that the

central aim of ekphrasis—the description of an artwork—has been replaced by modes of rewriting the artwork and in the process questioning accepted meanings, values, and beliefs, not just relating to the particular artwork in question but referencing the ways of seeing and the scopic regimes of the culture at large. (Brosch, ‘Ekphrases’ 225)

Their oscillation between critique and enchantment, their use of ekphrasis to simulate ‘seeing’ through language, and their focus on a frame-filled artwork, allows both texts to be discussed with Jacques Derrida's notion of the parergon in mind. Derrida's parergon, which captures a reception-aesthetic problem of defining where the artwork begins and where it ends, facilitates the study of frames in visual art and in ekphrastic writing. In The Truth of Painting (1987), Derrida deconstructs the concept of ‘art’ by working with the Greek terminology of para (beside), ergon (work) and parergon (ornament), which were also important for Kant's aesthetic theory. He states that the parergon is

neither work (ergon) nor outside the work [hors d’oeuvre], neither inside nor outside, neither above nor below, it disconcerts any opposition but does not remain indeterminate and it gives rise to the work. It is no longer merely around the work. That which it puts in place – the instances of the frame, the title, the signature, the legend, etc. – does not stop disturbing the internal order of discourse on painting, its works, its commerce, its evaluations, its surplus-values, its speculation, its law, and its hierarchies. (Derrida 9)

While these ideas were uttered with the visual arts in mind, they can also be applied to the discursive arts. Combining ekphrasis with the parergon via the motif of the frame, this article shows that ekphrasis can be considered as a discursive parergon whose employment in contemporary non/fictional life writing upends binary pairs. Like the parergon, ekphrasis challenges the borders of art and life, fact and fiction, literature and painting, and inside and outside. Given its powers to highlight visualization (Brosch, ‘Images’ 343) and make the reader a quasi-eyewitness, ekphrastic texts actively entangle the reader within their own meaning-making processes of representing, looking, challenging and reassessing, thereby further dismantling the opposition between ergon and parergon. Thus oscillating between various porous frames, the reader experiences the parergon through the act of reading ekphrastic writings.Footnote4

By exploring how Amy Sackville and Laura Cumming employ this complex visual strategy that combines ekphrasis with parergonal frames, this article adds to the critical understanding of women's contemporary life writing. The next section discusses Sackville's historical novel, which stages a metaphorical entrance through the frame of Las Meninas to enter Velázquez's time period, and the final section analyses Cumming's non-fictional book, which gives the reader an understanding of the protagonist's obsession with Velázquez by evoking Las Meninas in the frame narrative. By ekphrastically closing the distance between the present and the past—seventeenth-century Spain and nineteenth-century Britain respectively—both writers make a profound statement on the enduring power of Velázquez's art and the persistent occupation with selfhood.

Through the Frame: Amy Sackville's Painter to the King (2018)

In her 2018 novel Painter to the King the British author Amy Sackville (b. 1981) uses intermedial aesthetics to explore the process of looking and interpreting, and the mechanisms of power within and without the frame of representation. Her historical novel is a biofiction of Velázquez and of the different court residents that are depicted throughout his work. The novel is thus a Pygmalion fantasy that brings Velázquez's famous artworks to life. It is comparable to Tracy Chevalier's Girl with the Pearl Earring (1999) and Maureen Gibbon's Paris Red (2015), which reimagine the lives of Johannes Vermeer and Édouard Manet respectively. While these novels lend a voice to Vermeer's Girl with the Pearl Earring (1665) and Manet's Olympia (1863), enlivening their female sitters, Sackville's novel makes Las Meninas speak.

Formally speaking, Painter to the King is split into two levels of diegesis: a frame narration that follows a first-person narrator in present-day Madrid and a story-within-the-story that covers the life of Velázquez at the Spanish royal court from 1622 to1660. The story-within-the-story, subdivided into three main sections that are delineated by Velázquez's two trips to Italy in 1629 and 1649, is given as a chronological string of births, marriages, festivities, deaths and portraits to commemorate all of those events: ‘The painter looking on, living still, in the world; seeing it, seeing its surfaces, the things in it, the light on it, moving through it, and arranging it’ (Sackville, Painter 240). Sackville's style is stuffy and crowded, full of nouns and lengthy descriptions of life at the court; it is full of ellipses and dashes that break the narrative apart, disrupt its continuity and the illusion of realism, and that evoke the lengthy, fragmentary, non-linear process of seeing, painting and ultimately also writing and reading; it brims over with rhetorical devices such as repetitions and syntactic parallelisms; it persistently evokes the images of frames, doors and openings, which organize the literary space as one that can be traversed; and its typographical oddities, such as crossed out words to indicate censorship at the court, once again highlight the act of writing and reading itself. In other words, this is a novel that openly displays its nature as a text.

With the decline of the Spanish empire as a backdrop, readers follow Velázquez's life at the Alcázar and witness how he creates the paintings that have changed art history. Twenty-one black-and-white reproductions furnish the text and ‘serve disruptive or associative functions, rather than being purely deictic’ (Behluli and Sackville n. pag.), while bilingual chapter titles reflect its nature as a dynamic contact zone between cultures, time epochs, and media. The novel's contents page, which lists chapter titles such as ‘Bodégon/Still life’ and ‘Las hilanderas/Spinners’ (Sackville, Painter ix-x), reads like a list of figures from an art criticism book. Clearly, Sackville's novel is emulating visual art by having such a genre-bending paratext and a frame-like narrative structure.

Many of these concerns are brought to the fore by putting Las Meninas at the heart of the novel. The figures in the painting are evoked on the very first pages, welcoming the reader into their royal world. An important detail of this initial ekphrasis can be found on the left-hand side of the painting: it is the painted back of the canvas, with its surface remaining unknowable to anyone but the painted Velázquez who is about to make another line with his brush. This mysterious painted painting is also known as ‘the most famous canvas in the history of painting’ (Cumming, Face 118) and immediately captures the reader's interest. Moreover, since it also captures the narrator's interest, this painted canvas triggers a narrative desire to step into the frame of Las Meninas and discover the secrets that lie within:

I want to pass through this archway I’m stopped in and cross the gallery and step through the frame and into the whole room beyond it, find my way through and between them, their heads all turning to watch me pass or else still staring out as I move invisible among them; pause and stand at the painter's shoulder and find out at last what he's painting, what's on the surface of the canvas, the reverse of that vast framed blank back, what he and only he can see […]. (Sackville, Painter xi–xii)

Through the use of form (multiple layers of diegesis, self-reflexivity, the motif of the frame) and the mode of ekphrasis, Painter to the King offers its reader a dynamic, critical and affective exploration of the world in Las Meninas. The temporal and spatial travel that is enabled by the above-quoted ekphrasis highlights the porousness of frames and borders, inviting the reader to compare seventeenth-century with twenty-first-century power structures: from a declining monarchy in the narrated time of the story-within-the-story to a functioning democracy in the narrative time of the frame narration; from the restriction of paintings to an elite group of patrons and collectors to the democratized access to fine art in museums; and from the male gaze of Velázquez's art to the female voice of Sackville's narrator.Footnote5

These socio-political comparisons between the past and the present are enhanced by the ekphrastically-evoked Las Meninas, which pulls the viewer (and, through ekphrasis, the reader) into the novel's meaning-making structures. As Foucault has shown by paying attention to the mirror and the gazes, the composition of Velázquez's painting puts the viewer in the same spot where the king and the painter are. Because the viewer and the reader thus inhabit the painting's compositional centre, they are necessarily a part of it; they are simultaneously outside and inside its frame. Sackville confirms these connections between the verbally described painting and the effect on the reader:

Las Meninas in particular (as well as other works that play with frames and complex perspective) provided a formal model for the book as a whole, in terms of the voice and the point of view. I wanted to do something that would unsettle the reader, as that painting unsettles the viewer, so that we are never quite sure where we stand in relation to it or where it is we should be looking. (Behluli and Sackville n. pag.)

Painter to the King is an exercise in ‘deliberately break[ing] the frame of fiction’ (Behluli and Sackville n. pag.). In the first half of the frame narration, titled ‘Frame’ (Sackville, Painter xi-xiii), the narrator delivers the first full ekphrasis of Las Meninas:

It opens out from this dark corner: halfway along this corridor and – there's the door. […] I see: opposite, a man is also pausing in a doorway. And everything's stopped. Between us: on my side of the frame, the buzz and brightness of the gallery; and on his a cool grey room, lofty, quiet, dim in its high and far corners. Both of us at a threshold, and the threshold of the frame between. And they are all there – all long familiar, I’ve been half-seeking them even and yet – – this shock. There they all are! Just as if they always have been, or have just this moment stopped. Looking back. And, just off-centre, just looking, he has just stepped back, he's also just stopped – the painter; there he is, with his long brush. (Sackville, Painter xi)

The passage is full of frames, doorways, corridors, and thresholds—spatial confinements that set the scene for the frame narration and the story about to begin. The evoked spatial frames mirror the formal frame, and thus immediately create a parallel between the spatial, visual work of art and the temporal, consecutive work through which it is being consumed.Footnote6 The moment of sudden arrest, indicated by the dashes and the numerous temporal markers ‘just’, is reminiscent of Foucault's interpretation of Las Meninas. Sackville's language evokes a bustling energy that was just interrupted by the narrator/spectator/reader, who entered the space of the painting (on the level of diegesis or through ekphrasis) and made the painted faces look out. The figures and the painting seem alive. The passage continues:

But look how real, in contrast: this illusion he has made. How true to a life that is, itself, illusion: nothing more – but not less, either. Shadows and shams. A life lived as a dream that repeats and retreats and refracts through succession of sometimes impossible frames; I was – – but also at the same time you – I was there and also watching and you – and then – – But – then again – – Step closer, and it's all just a surface of smears; rough daubs, features half-formed, hands that only gesture at the shape of hands. The painter's brush has a long handle – made only of a swipe of that same brush; and so, stepping back, stopped, he sees clearly the illusion of coherence he is bringing into being. (Sackville, Painter xiii)

However, we have to remember that the evoked painting is a historical artefact that physically exists as an intertext outside the pages of the novel, which is why the novel cannot be self-contained. In other words, the narrative frame is as porous as the frame of the painting. This conflict between inward pointing vectors of signification and outward pointing vectors toward the intertext create an unresolved dynamic within the novel, in which the reader is also entangled. Las Meninas is perfect for this kind of reader engagement as its own composition, according to Foucault, relies on the inclusion of the viewer via the palimpsest of sovereign, painter, viewer. The first half of the frame narration thereby creates an intersubjective, mutually dependent presence of painting, observer and, by ekphrastic extension, reader.

The same effect is produced in the second and closing half of the frame narration, titled ‘Expinxit’ (Sackville, Painter 311–314). Naturally, this second half is given after the entire story-within-the-story, pulling the reader out of the seventeenth and into the twenty-first century. Here are the final lines of the novel:

I grin back at you as if we share a joke. You, still in the world. […] I keep glancing, moving off, stopping. Don't want the last time I look to be the last time. How can I, how can I – – And then here are the marks of your brush where you swiped the paint off, the true mark of your hand – so that I am close to tears, when I thought I meant to laugh – and I’m here, this morning in April, still a bit sneezing, and I’ll have to leave eventually but you – about to make your mark, the first, the last – – here you almost are. (Sackville, Painter 314)

Moreover, through the topos of the gaze and the trifold construction of the centre outside of its own frame, Las Meninas includes the spectator/reader within its composition and asserts their existence, too: ‘I’m here, this morning in April’. Given this clever compositional trick, Velázquez's portrait not only immortalizes the presence of its sitters but also reaffirms the presence of the spectator. To repeat, seeing is not only intertwined with hierarchies of power but also with the construction of the self. Being seen is being acknowledged to exist (Berger 8–9), or, as Siri Hustvedt's protagonist in The Summer Without Men (2011) says: ‘I want you to see me, see Mia. Esse est percipi’ (Hustvedt 81). To be is to be seen. Paradoxically, then, reading ekphrastic fiction on Las Meninas is not only an immersive engagement with Foucauldian questions of power and representation, but also a self-affirming act of intersubjective identity construction as it has been discussed since Maurice Merleau-Ponty's phenomenological approach (1945). The frame expands to include the outside of the painting within the inside of the painting, and the construction of the viewer's self becomes intertwined with the artwork. The reader, who is reading a novel about the lives of others, is asked to turn their gaze on their own life.

Framing a Life: Laura Cumming's The Vanishing Man (2016)

In her non-fictional book, The Vanishing Man: In Pursuit of Velázquez (2016), the art critic Laura Cumming (b. 1961) tells the story of John Snare, a Victorian bookseller from Reading whose claim to have found Velázquez's missing portrait of Charles I leads to his personal and financial ruin. This suspense-filled tale of enchantment and obsession blurs the border between various genres, including life writing, art criticism and detective fiction. Even though the primary focus of this genre-bending book is not Las Meninas but Velázquez's missing portrait of Charles I, the first and the last chapters deliver lengthy descriptions of Velázquez's masterpiece. In other words, these two ekphrastic chapters on Las Meninas frame the other eighteen chapters on Snare's discovery and function similar to Sackville's frame narration. Instead of beginning and ending her story with the painting that the book is about, Cumming thus creates a formal, visual and cognitive frame by ekphrastically evoking the complexity of characters, frames and gazes from Las Meninas.

Given that the story-within-the-story is about a painting that no living person has ever seen, Cumming's use of Las Meninas—a widely known artwork with a complex semantic code—creates a quick and effective frame of reference for the reader. By priming her reader's mental eye with Velázquez's known visual language, Cumming can work within this frame of reference to visually evoke a painting that presumably does not exist anymore in any other medium than words. Moreover, through ekphrasis Cumming is again able to transgress the frames that the image and the text pose to viewers and readers. Here is how she evokes Las Meninas:

his painting has the characteristics of a mirror, too: look into it and you are seen in return. Many paintings have the scene-shifting power to take us to another time and place but this one goes further, creating the illusion that the people you see are equally aware of your presence, that their scene is fulfilled by you. Velázquez invents a new kind of art: the painting as living theatre, a performance that extends out into our world and gives a part to each and every one of us, embracing every single viewer. (Cumming, Vanishing 3–4)

By verbalizing the aesthetic experience that the encounter with Las Meninas produces, Cumming also makes an explicit appeal to affect. Before she plunges into Snare's story, she laments that ‘Even quite fundamental emotions are not in the language of scholarship, let alone museums, which rarely speak of the heart in connection with art. Yet so many people have loved Las Meninas’ (Cumming, Vanishing 6). Cumming's critique is profound as it sets up not only the story that is about to ensue—a man driven by his obsessive love for a painting—but also the way in which she as the narrator is about to deliver her narrative. It is also an instruction to the reader, who is encouraged to read John Snare's story with empathy. Take the following passage:

The moment you set eyes on them, you know that these beautiful children will die, that they are already dead and gone, and yet they live in the here and now of this moment, brief and bright as fireflies beneath the sepulchral gloom. And what keeps them here, what keeps them alive, or so the artist implies, is not just the painting but you. […] It [the painting] shows the past in all its mortal beauty, but it also looks forward into the flowing future. Because of Velázquez, these long-lost people will always be there at the heart of the Prado, always waiting for us to arrive; they will never go away, as long as we are there to hold them in sight. (Cumming, Vanishing 2–4)

While this paragraph makes a clever observation on the role of the spectator and how he is turned into a vital part of the painting's composition through the gaze across the frames, Cumming's language is more that of an art lover than that of an art critic. Still mourning the death of her father—just as Sackville's narrator mourns the death of her beloved painter, Velázquez—Cumming's hybrid narrative is heavily influenced by subjective experience and affect. It celebrates emotions and integrates them into John Snare's life narrative, which is permeated with descriptions of Velázquez's art. After all, claims the author, affect was the main propeller for John Snare's passionate actions, and so is also the propeller behind her narration of Snare's life: ‘Snare's feeling for Velázquez touched me’ (Cumming, Vanishing 7). Seeing, feeling, interpreting and telling become intertwined. By premising her book on strong feelings evoked by art rather than on critical ideas on art, and by ekphrastically describing that art in the hope of evoking similar feelings in the quasi-seeing reader, the celebrated art critic, Cumming challenges academia's categorical omission of affect in favour of reason. Las Meninas is used to bend disciplinary borders and to turn art criticism itself into a form of art.

Cumming's decision to begin her non-fictional account of Snare's life with an ekphrasis of Las Meninas, the ultimate ‘allegory of watching and looking’ (Cumming, Face 129), harvests the narrative impulse of the painting. Seven years before the publication of The Vanishing Man, Cumming also dedicated a section of her study On Self-Portraits to Las Meninas, where she maintained that ‘Novelists think of it as a pictorial novel—all these characters, the relationships between them so carefully plotted—and playwrights as a brilliantly complex tableau’ (Cumming, Face 121). Thus, by beginning Snare's story with an ekphrastic prologue on Las Meninas, Cumming aligns herself with narrative storytelling, with affect and with genre-bending practices. With this mixture of genres Cumming is truly at the forefront of contemporary life writing.Footnote7

Just as literary ekphrasis has a long tradition, Cumming's use of ekphrasis in non-fiction is not uncommon. In fact, Jas´ Elsner argues in his article ‘Art History as Ekphrasis’ (2010) that art history as a discipline ‘is nothing other than ekphrasis, or more precisely an extended argument built on ekphrasis’ (Elsner 11). Drawing from Elsner and extending it to the discipline of literary studies, the complexification of literature through digitality is forcing scholars to fall back on the use of ‘critical ekphrasis’ more and more (Behluli and Rippl 166–168). The realization ‘that large parts of [academic writing] are ekphrastic in themselves and that we, as academics, have entered the realm of aesthetics’ (Behluli and Rippl 171) holds true, and Laura Cumming seems to have come to the same conclusion. After all, Velázquez's painting of Charles I has not survived as an object and exists only in the realm of words, created by Cumming. The form of The Vanishing Man certainly suggests this interpretation by shifting its attention back to Las Meninas in its final chapter, which is titled ‘Saved’, and thereby closing the frame that it opened in the first chapter:

As many as five hundred paintings burned in the flames [of the Alcázar in 1734]. On the palace walls that Christmas were two large works by Velázquez. One was a famous early triumph, The Expulsion of the Moors from Spain […]. This masterpiece burned. The other was Las Meninas, greatest of all paintings, saved only by the speed and dexterity of exactly the humble people Velázquez depicts – the servants of the palace, who managed to free the canvas from its frame and push it out into the wintry courtyard below before the smoke overwhelmed them. (Cumming, Vanishing 262)

Whereas Amy Sackville employs Las Meninas as a gateway into an imaginative world, where readers can experience the intricate lives of Velázquez's royal sitters in a quasi-embodied manner, Laura Cumming draws from the enchanting quality of Las Meninas to explain John Snare's fascination with a painting. After all, it can be hard for a twenty-first-century reader to identify with a privileged and war-burdened seventeenth-century Spanish king, for example, or with a nineteenth-century bookseller from England who turned his life upside down for an artwork. While most readers will value art in some shape or form, these two narratives are about the lives of those to whom art is everything. Both texts strongly highlight empathy, which is also commonly ascribed to the manner with which Velázquez depicts his subjects. This is crucial because just as the gaze pulls the viewer of Las Meninas into the frame and just as the mirror reflects a version of selfhood back to the viewer, Sackville's and Cumming's empathetic tone invites their readers to step into the lives of the people that are features in these life narratives. Moreover, just as Velázquez's painting is organized in a way to incorporate the viewer within its own composition, so are Sackville's and Cumming's texts constructed to include their readers into their meaning-making structures: this narrative is not just about the lives of others, they seem to be saying, but also about the life that you live and the self that you see in the mirror—this book is also about you.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Amy Sackville, Laura Marcus and the Americanists at the University of Bern, including Gabriele Rippl, for their invaluable help with this article. My research and my visit to the Prado were kindly funded by the Berrow Foundation Scholarship and the Vivian Green Fund at Lincoln College, Oxford, respectively.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Before 1843, the painting was referred to by various other names, including “The Family”.

2 Both Sackville and Cumming have experimented with visual storytelling elsewhere: Sackville's novel Orkney (2013) is set on a Scottish island and is filled with colorful descriptions of the environment; Cumming's non-fictional On Chapel Sands (2019) relies on photography to tell her mother's childhood story.

3 Cf. Gabriele Rippl's article for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature (2019) for a more comprehensive overview on ekphrasis to date.

4 Needless to say, this article silently builds on numerous other preceding studies. Apart from research on frames, for example by Erving Goffman in the social sciences (1974), Mary Ann Caws in modern fiction (1985), and Werner Wolf and Walter Bernhart's in literature and other media (2006), implicit attempts to bring ekphrasis and the parergon have also been attempted (Heffernan 137; Brock 133-134; Milkova 160; Müller 201).

5 Strictly speaking, the narrator of the novel remains ungendered. There are various indicators, however, to interpret this narrative voice as a fictionalized version of the author herself.

6 Cf. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's Laocoon (1766), from which the adjectives in this sentence are borrowed, for the first systematic comparisons of the sister arts.

7 Contemporary literature has indeed experienced a meteoric rise of genre-bending life narratives, especially of ‘autofiction’. Examples include Rachel Cusk's Outline trilogy (2014-2018), Sheila Heti's Motherhood (2018), and Siri Hustvedt's Memories of the Future (2019).

Works Cited

- Alpers, Svetlana (1983), ‘Interpretations Without Representation, or, The Viewing of Las Meninas’, Representations 1, pp. 30–42.

- Ashbery, John (1994 [1973]), ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’, in Selected Poems, 188–204. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Banville, John (2014 [1989]), The Book of Evidence, London: Picador.

- Behluli, Sofie and Amy Sackville. Literary Portraits: An Interview with Amy Sackville. Email correspondence thread “Re: DPhil Chapter on Painter to the King”, 4 April 2019.

- Behluli, Sofie and Gabriele Rippl (2017), ‘Ekphrasis in the Digital Age’, in Christina Hoffmann and Johanna Öttl (eds.), Digitalität und Literarische Netz-Werke, Antikanon 2, 131–76. Wien: Turia + Kant.

- Berger, John (2008 [1972]), Ways of Seeing, London: Penguin.

- Brock, Richard (2011), ‘Framing Theory: Toward an Ekphrastic Postcolonial Methodology’, Cultural Critique 77, pp. 102–45.

- Brosch, Renate (2018), ‘Ekphrases in the Digital Age: Responses to Image’, Contemporary Ekphrasis, edited by Renate Brosch, special Issue of Poetics Today 39:2, pp. 225–43.

- Brosch, Renate (2015), ‘Images in Narrative Literature: Visibility – Visualization – Description’, in Gabriele Rippl (ed.), Handbook of Intermediality: Literature – Image – Sound – Music. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 343–60.

- Carroll, Lewis (2010 [1865]), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, London: Collins Classics.

- Caws, Mary Ann (1985), Reading Frames in Modern Fiction, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chevalier, Tracy (2014 [1999]), Girl with a Pearl Earring, London: Borough Press.

- Cumming, Laura (2019), On Chapel Sands: My Mother and Other Missing Persons, London: Chatto & Windus.

- Cumming, Laura (2017 [2016]), The Vanishing Man: In Pursuit of Velázquez, London: Vintage.

- Cumming, Laura (2009), A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, London: Harper.

- Cunningham, Valentine (2007), ‘Why Ekphrasis?’, Classical Philology 102:1, pp. 57–71.

- Dannenberg, Hilary P (2008), Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

- Derrida, Jacques (1987), The Truth in Painting, Translated by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Elsner, Jas´ (2010), ‘Art History as Ekphrasis’, Art History 33:1, pp. 10–27.

- Finaldi, Gabriele (2006), Velázquez: Las Meninas, London: Scala.

- Foucault, Michel (2005 [1966]), The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, London and New York: Routledge.

- Foucault, Michel (1995 [1975]), Discipline and Punish, New York: Vintage Books.

- Frayn, Michael (1999), Headlong, London: Faber and Faber.

- Gibbon, Maureen (2015), Paris Red, New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Goffman, Erving (1986 [1974]), Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Heffernan, James A. W (1993), Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Hepburn, Allan (2010), Enchanted Objects: Visual Art in Contemporary Fiction, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Hustvedt, Siri (2011), The Summer Without Men, London: Sceptre.

- Kennedy, David (2012), The Ekphrastic Encounter in Contemporary British Poetry and Elsewhere, Farnham: Ashgate.

- Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim (1984 [1766]), Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, translated and edited by Edward Allen McCormick, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lewis, Clive Staples (2010 [1950–56]), Chronicles of Narnia, London: Harper Collins.

- Louvel, Liliane (2018), ‘Types of Ekphrasis’, Contemporary Ekphrasis, edited by Renate Brosch, Special Issue of Poetics Today 39:2, pp. 245–63.

- Louvel, Liliane (2011), Poetics of the Iconotext, introduction by Karen Jacobs and translation by Laurence Petit, Farnham: Ashgate.

- Marriner, Robin (2002), ‘Derrida and the Parergon’, in Paul Smith and Carolyn Wilde (eds.), A Companion to Art Theory. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell, pp. 349–59.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2002 [1945]), Phenomenology of Perception, London and New York: Routledge.

- Milkova, Stiliana (2016), ‘Ekphrasis and the Frame: On Paintings in Gogol, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky’, Word & Image 32:2, pp. 153–62.

- Mitchell, William John Thomas (1994), Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Müller, Anja (2004), ‘“You Have Been Framed”: The Function of Ekphrasis for the Representation of Women in John Banville’s Trilogy (The Book of Evidence, Ghosts, Athena)’, Studies in the Novel 36:2, pp. 185–205.

- Rowling, Joanne K (2011 [1997–2007]), Harry Potter, the Complete Collection, London: Bloomsbury.

- “Richard Hamilton: Picasso’s Meninas. 1973” Tate Official Website. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hamilton-picassos-meninas-p07659 (accessed 7 February 2021).

- Rippl, Gabriele (2019), “Ekphrasis.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press. N. pag. https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-1057 (accessed 7 February 2021).

- Rippl, Gabriele (2015), ‘Introduction’, in Gabriele Rippl (ed.), Handbook of Intermediality: Literature – Image – Sound – Music, 1–31. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter.

- Sackville, Amy. “Dog in a Hole.” BBC Radio 4, radio broadcast, 2018. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/71034 (accessed 7 February 2021).

- Sackville, Amy (2018), Painter to the King, London: Granta.

- Sackville, Amy (2013), Orkney, London: Granta.

- Todorov, Tzvetan. “The Typology of Detective Fiction.” In The Poetics of Prose, translated by Richard Howard and with a Foreword by Jonathan Culler. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977, 42–52.

- Webb, Ruth (2009), Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical Theory and Practice, Farnham: Ashgate.

- Wolf, Werner and Walter Bernhart eds. (2006), Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media. Studies in Intermediality, Volume 1, Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi.