Abstract

Feminist Book Fortnight was a signal event in the history of feminist publishing, but its history has not yet been written. Throughout the latter half of the 1980s, the Fortnight promoted feminist literature in the UK and Ireland and helped to sustain and power a revolution in feminist publishing. Drawing on the archives of Spare Rib magazine, this article analyses the often fierce tension between the Fortnight’s activist aims and its commercial imperatives, and maps out the distinctive regionalism of this annual book trade promotion. Books and literature were of vital importance to the women’s movement and Feminist Book Fortnight supported the expansion of the feminist literary marketplace outside London. As I will show, the Fortnight navigated not only between the activist margins and the commercial mainstream, but between isolated feminist outposts and metropolitan centres. Combining feminist digital geography with oral histories and literary analysis, this article concentrates not on women readers or authors but on the workings of the industry which mediated the production and consumption of feminist literature at this time. I argue that the Fortnight’s complex renegotiation of extant publishing practices (Murray (2017): 814), both commercial and regional, constituted its most significant contribution to the larger feminist movement.

In 2018, ‘Feminist Book Fortnight’ (FBF) was held in the UK and abroad for the first time in twenty-seven years. The revival of the Fortnight—which marks the recent resurgence of feminist activism, as well as the enduring gender bias in publishing—was instigated and co-ordinated by veteran bookseller Jane Anger and Five Leaves radical bookshop in Nottingham, and 52 independent booksellers across the country took part, with participating authors including Lynne Segal and Deborah Levy. The original Fortnight, which ran from 1984 to 1991, was an annual British book trade promotion which grew out of the women’s movement of the 1970s and 1980s, and a signal event in the history of feminist publishing. Its sister-event, the International Feminist Book Fair (IFBF), has been recognized as the ‘moment when feminist publishing steamrolled the mainstream’ (Withers Citation2018: 150; also c.f. Gerrard Citation1989). An early review of the Book Fair describes how ‘what was planned as a three-day gathering in London spilled over into nearly two weeks of events and gatherings throughout Britain and Ireland’ (Loeb Citation1984: 17). That ‘spill over’ of nationwide events was, in fact, the inaugural Fortnight, known then as ‘Feminist Book Week’. While the Book Fair became a biannual event that travelled around the world, from one Western capital to another, ‘Feminist Book Week’ evolved into a fortnightly promotion held annually in towns and cities across the UK and Ireland.

Figure 1. First International Feminist Book Fair 1984 © Jenny Matthews. Reproduced by kind permission of Jenny Matthews.

The Fortnight quickly became an autonomous national event with its own far-reaching regional networks that stretched from Stirling to Londonderry, and from Swansea to Deal. According to Anger, who was an organizer of the original Fortnight as well as its recent revival, ‘the whole point of the week’ was to get feminist literature out of London and into the regions (Anger and Watts Citation2021). As I will argue, the Fortnight fostered a distinctively progressive and outward-looking regionalism, even as it helped to mainstream not only feminist literature but the term ‘feminist’ itself (Fairbairns Citation2017: 12).

Where the Fair was determinedly international and metropolitan in its focus—even as aspects of this internationalism were hotly contested (Spare Rib August 1984: 48)—FBF joined the local with the international, hosting local writers’ groups alongside internationally renowned authors.Footnote1 During the Fortnight, bookshops and public libraries across the country welcomed international luminaries including Maya Angelou, Kathy Acker, Nawal El Saadawi, Buchi EmechetaFootnote2 and Margaret Atwood alongside community groups from local performance poets in Plymouth to the Huddersfield Women’s Studies Group. In the words of feminist author Nicci Gerrard, ‘the first Feminist Book Fortnight … was an open, angry and exciting meeting between women writers—and their readers—from all over the world’ (Citation1989: 60). Comprised of book launches and signings, readings and discussions, and featuring an annual ‘Selected Twenty’ feminist titles, the Fortnight was a wide-ranging and highly successful event which steadily grew in size. By 1988, four years into its run, more than 500 bookshops, 355 public libraries and 82 educational bodies took part, with 97 ‘locally organised events’ in 23 towns and cities across the UK (SR June 1988: 26). Its twin achievements were commercial success—The Bookseller described the Fortnight in 1990 as ‘one of the UK’s most successful book trade promotions’ (quoted in US publication Feminist Bookstore News August 1990: 48)—and its geographical outreach, which stretched from coast to coast.

Nancy Fraser’s concept of the feminist ‘counterpublic’, frequently invoked by scholars of late twentieth-century feminist print culture, helps us to understand FBF’s unique contribution to the feminist literary sphere (Fraser Citation1992: 123; Hogan Citation2008; Forster Citation2016; Thomlinson Citation2017). The feminist ‘counterpublic’ is, for Fraser, a ‘parallel discursive arena’ where counterdiscourses can be invented and circulated, and oppositional interpretations of identities, interests and needs formulated (Fraser Citation1992: 119). FBF was in many ways an exemplary feminist counterpublic. The Fortnight created physical spaces across the country for feminists to come together and engage with feminist texts, discussion and literary networks for two weeks every June for almost a decade. Many of the FBF events were women-only and some were Black women-only, and thus they supplemented the important ‘counterpublic’ feminist spaces—physical and local—that did not exist within the mainstream book industry. In so doing, it helped to sustain and power a feminist print culture that was of central importance to the women’s movement (Delap Citation2016: 171). A reader survey undertaken by Spare Rib in 1985 found that books were not just a ‘major interest’ for Spare Rib readers—they were a ‘massive addiction’ (SR November 1985: 35). As a trade promotion, the Fortnight not only distributed, highlighted and publicized that literature, but did much to construct the very means of feminist communication through its cultivation of regional, activist and professional networks.Footnote3

In opening up physical spaces for communities of women across the country, in tandem with feminist booksellers and librarians, the Fortnight broadened and extended the feminist literary map, and made more feminist books available to more women. The driving force behind the Fortnight, reiterated by its own promotional literature, its organizers and its structure, was the felt need to make feminist literature more widely accessible. Rather than creating a singular counterpublic, FBF established a network of regional, often ephemeral but recurring feminist counterpublics and, as I shall argue, a sense of feminist community that was simultaneously local and international. While some FBF events were hosted by existing feminist bookshops, many more were hosted by arts centres, public libraries, theatres and other radical bookshops, taking literary events into parts of the country which did not otherwise have access to feminist spaces. Responding to the call for increased attention to the politics of space and place in the history of feminism (Massey Citation1994; Jolly Citation2012; Bruley Citation2016), this article explores this regional organization more closely. To explore the history of FBF is to explore one of the highly localized networks of the women’s movement. This network, which was coordinated at a national level, vitally depended on the energies and commitment of its regional organizers, while also engaging with international feminist networks.

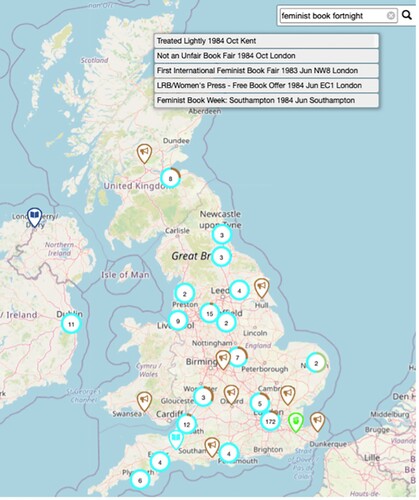

Drawing on the extensive FBF listings contained within the Spare Rib archive—the only available record of the Fortnight’s activities across its entire run—the visualization of these listings on the Spare Rib digital map,Footnote4 and interviews with feminist booksellers, this article seeks to redress what Trysh Travis has identified as a tendency within feminist book history to concentrate on women readers and authors, rather than the workings of the industry that ‘brings them to market’ (Travis Citation2008: 814). As the longest-running feminist magazine in Britain, Spare Rib’s listings afford a unique perspective into the rise and fall of feminist campaigns such as FBF. The Spare Rib digital map, the first such map of the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM), reveals the extent of the feminist literary (and non-literary) enterprise which the movement enabled and which in turn enabled the movement. Firstly, I explore the economics of FBF and its flagship promotion, the ‘Selected Twenty’ titles, to examine the relationship between the Fortnight’s commercial success and its geographical reach; and secondly, through the Spare Rib map and geographically specific case studies, I identify the feminist literary hubs and outposts of the 1980s and examine how FBF contributed to the larger feminist movement. As I will show, the Fortnight navigated between the activist margins and the commercial mainstream in an attempt to balance profit with purpose, although this balancing act was not without its tensions. It also navigated between isolated feminist outposts and metropolitan centres and created highly local, but also progressive and outward looking, feminist-literary networks.

Navigating the Feminist Marketplace of the 1980s

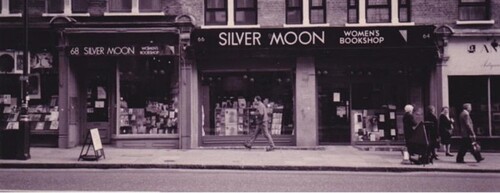

When the Fortnight ran for the first time in 1984, feminist and radical publishing in Britain was thriving; by 1991, the end of the Fortnight’s initial run, the radical book trade (and feminist activism) was in serious decline. The period over which FBF took place was characterized by the entrenchment of Thatcherism, with its advocacy of free-market economics and cuts to public bodies including the Greater London Council (GLC), which supported hundreds of feminist projects in the early 1980s, and the Arts Council. The organizers of the first Feminist Book Fair recognized that its launch took place against a backdrop of political struggle and economic hardship, writing in the inaugural catalogue that ‘it is indicative of the power of the movement that 1984, that most pessimistic of years, sees the First International Feminist Book Fair: an event that has the confidence, strength and audacity to call for a celebration’ (FBF Group Citation1984: 1). The book industry changed rapidly at this time, and FBF negotiated the opportunities and hazards of a decade during which ‘both the promotion and the reception of serious literary fiction [became] steadily more consumer-oriented’ (Todd Citation1996: 128). Chain booksellers were unknown in Britain, with the exception of WH Smith, until the mid-1980s (Feather Citation2006: 226). The growth of the new chains eventually led in 1994 to the collapse of the Net Book Agreement, which had allowed publishers to set the retail price of books, and irrevocably altered the structures of the British book trade. In 1984, the bookselling climate was very different. The Federation of Radical Booksellers (described by bookseller Mandy Vere as ‘a force to be reckoned with in the booktrade’ in Hanman, Citation2010) co-ordinated over 100 radical bookshops across the country, organized an annual conference, circulated regular newsletters and campaigned on behalf of the interests of small independent booksellers. The Federation of Radical Booksellers’ membershops (as they were called) often hosted FBF events and were advertised in its annual catalogue. The International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books, established in 1982 and organized by Jessica Huntley and John La Rose, had become a celebrated annual event, and women’s presses were thriving—in 1984, Onlywomen Press was ten years old, Virago eight, The Women’s Press seven, Sheba four and Pandora, one. The first Black women’s publishing co-operative, Black Womantalk, was launched the same year (SR May 1983: 17; SR October 1984: 30), as was the soon-to-be well-known feminist bookshop Silver Moon on Charing Cross Road. The Fortnight, alongside the Feminist Book Fair, supported the expansion of the feminist book trade still further through the provision of publicity and the facilitation of nationwide networking. Significantly, as I will show, the Fortnight was an early adopter of innovative ways of marketing feminist literature—such as its ‘Selected Twenty’ promotion—and utilized commercial means to non-commercial ends.

Figure 2. Silver Moon Women’s Bookshop © Jane Cholmeley. Reproduced by kind permission of Jane Cholmeley.

FBF constituted the most significant national promotion of feminist literature in Britain in the 1980s, and its organizers were very candid about the commercial commitments which supported its mission to bring feminist literature to a wider audience, and to provide a platform for women writers.Footnote5 In 1988, Carole Spedding, the Fortnight’s main organizer, described the aim of FBF, alongside the IFBF, as

a desire to put feminist books, publishing and ideas firmly onto the commercial marketplace. In other words, to make them more easily available to the general book reading, and buying, public. Feminist publishers and writers in the UK have long felt held-back by resistant retailers who constantly declared ‘Feminist books don’t sell’. We knew that more and more people wanted to read what feminists were writing and publishing and … . a conscious decision was taken then to approach the problem from a strong commercial and business viewpoint. (SR June 1988: 26)

The Fortnight’s marketing strategy involved raising funds to publicize itself through participating publishers. In 1986 there were 80 participating publishers with 300 titles, up from 55 publishers with 200 titles in 1985, and the Fortnight continued to grow year on year (SR June 1986: 22). The Fortnight offered a sliding scale of charges in recognition of the financial struggles faced by small independent publishers (SR June 1986: 22), meaning that inclusion in the FBF catalogue was a welcome promotion opportunity partly funded by much bigger multinational publishers such as Routledge and CVBC (the Chatto, Virago, Bodley Head and Cape Group). In their first year, the Fair and Fortnight received the backing not only of mainstream publishers but also of WH Smith and the Publishers Association of Great Britain, a development that Spare Rib described as ‘mildly astounding’ (SR June 1984: 21), but which ‘alienated many within the radical book trade’ (Chester Citation2020: 38).Footnote6 In 1986, WH Smith printed 15,000 copies of the FBF catalogue at their own expense, stocked many of the 300 or so titles chosen by the book fair committee as representative of the women’s publishing industry (Withers Citation2018: 151) and placed displays of feminist books in 150 of their shops during the fortnight. At the time, WH Smith was the largest chain bookseller in Britain, with a virtual monopoly on booksales in smaller towns (Feather Citation2006: 226).Footnote7 Lennie Goodings attributes Smith’s involvement to Michael Poultney, a ‘quietly political’ book buyer who used his position within the company to try and effect change (Citation2020: 138). Despite Smith’s initial reluctance to use the term ‘feminist’ (minutes from meetings of feminist organizers in 1983 record their preference for ‘Women’s Writing Week’),Footnote8 banners emblazoned with the word ‘feminist’ did end up in Smith’s windows—an early sign of feminism’s mainstreaming.

Unlike the ‘straight’ or mainstream booksellers who funded the Fortnight’s publicity costs, the radical or independent book trade played a rather different role in the organization of the Fortnight. The so-called ‘straight’ bookshops (such as Smith’s) did not host FBF events: they stocked the ‘Selected Twenty’ titles and supported the promotion of the Fortnight, but the venues for the Fortnight’s programme of events (book launches, signings, discussions, talks and readings) were provided by independent bookshops, libraries, theatres, women’s centres and other communal spaces. Radical Black booksellers were at the forefront of what is remembered as an innovative form of promotion within the book trade at that time. Eric Huntley, of Bogle L’Ouverture, remembers that book launches were rare in the 1970s and 80s—many people ‘had never met an author’—and co-founder Jessica Huntley championed author events at the bookshop (Huntley Citation2021).Footnote9 Ferha Farooqui of Sisterwrite Bookshop recalls that author events were a ‘big thing’, a way of ‘nuturing women’s writing’ and fostering interactions between authors and readers rather than being simply a ‘book signing wheeze’ (Farooqui Citation2022). Activist bookshops were not only vendors but community hubs where people could come in, meet and talk to the authors whose books they were buying, and the Fortnight’s inclusion of the reading public and facilitation of local community-building were the non-commercial dividends of its commercial logics. The reasoning behind making the promotion a Fortnight was also driven by the economics of independent bookselling. A week-long promotion would not have been viable for already-stretched independent booksellers who needed at least two weeks’ worth of trading days to justify the costs of stocking up on new titles, publicizing their own events and installing a new window display, and to get maximum exposure to potential customers (Anger and Watts Citation2021).

In another sign of its commitment to mainstreaming feminist literature, FBF marketed itself extensively in mainstream media outlets, with announcements and articles in almost all the ‘glossy’ women’s magazines (Feminist Book News September 1984: 14). By advertising in magazines such as Cosmopolitan, the Fortnight’s organizers aimed to ‘get these [feminist] books into the hands of women who wouldn’t go to a radical bookshop’ (Anger and Watts Citation2021). The Fortnight was also advertised, of course, in the feminist press—most notably, Spare Rib.

Figure 3. From Spare Rib June 1984, ‘Women Writing’ issue. Reproduced by kind permission of Sue O’Sullivan.

Figure 4. From Spare Rib June 1984, ‘Women Writing’ issue. Reproduced by kind permission of Sue O’Sullivan.

At its height, the FBF listings occupied five pages of Spare Rib—an unrivalled amount of magazine space given over to one event or item. Lesbian and Gay Pride listings, by way of comparison and another annual June event, typically took up one or two pages of Spare Rib and no more. Spare Rib also ran features and interviews related to FBF and its ‘Selected Twenty’ authors. The Fortnight was also reviewed and advertised by international feminist publications. In 1988, the US feminist booksellers’ newsletter Feminist Bookstore News feted the British FBF for providing ‘an amazing amount of publicity for feminist titles’ and applauded the Fortnight’s success at keeping ‘an entire nation’s attention […] focussed, for two weeks at least, on women’s writing’ (Seajay Citation1988: 9).

Feminist Bookstore News (FBN) goes so far as to report that ‘several industry observers have suggested that the stability of the mid-size feminist publishers dates from the publicity received via the First International Feminist Bookfair (held in London) and the first Feminist Book Fortnight’ (Seajay Citation1988: 10).Footnote10 It is certainly true that securing the backing of WH Smith represented a step-change for the feminist publishing industry: previously, Smith’s had stocked Virago classics but refused to stock titles from the Women’s Press—a publisher whose books featured prominently in the Fortnight’s ‘Selected Twenty’ (Anger and Watts Citation2021).

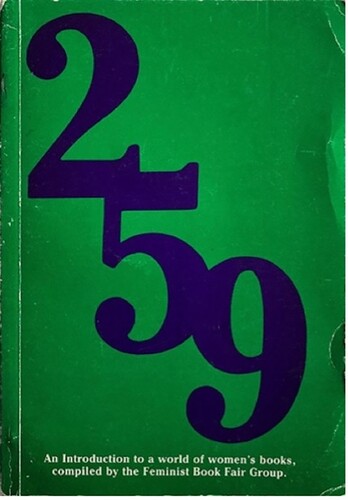

The FBF additionally produced its own promotional catalogue, using funds provided by participating publishers. In 1984, Gail Chester and Urvashi Butalia led the production of the catalogue—Chester recalls that Butalia, an Indian feminist writer and publisher, provided an invaluable internationalist perspective (Citation2022). The first catalogue was titled ‘259’, after the number of recommended feminist titles it listed, and included essays alongside the listed titles on feminist publishing initiatives in Zimbabwe, India, the Nordic countries and the US. In 1984, 20,000 copies of the catalogue were printed; by 1988, demand for copies of the catalogue exceeded 100,000 (FBF catalogue 1988: 2). As well as carefully categorized book lists, the catalogues provided addresses for participating publishers and radical booksellers, linking into a web of independent bookselling in the UK and helping to connect these bookshops to a wider public. A letter from Spedding to the Federation of Radical Booksellers (FRB) in 1988 requests a

complete list of all the radical bookshops in your organisation, for inclusion in the Feminist Book Fortnight ‘87 catalogue … which is given away free to the public in libraries and other bookshops … we have had much feedback from the general public saying that it was very useful to know where their local good, radical bookshop was located.Footnote11

Figure 6. Feminist Book Week catalogue 1984. Reproduced by permission of Feminist Book Fortnight Group.

Figure 7. Feminist Book Week catalogue 1988. Reproduced by permission of Feminist Book Fortnight Group.

Figure 8. Feminist Book Week catalogue 1991. Reproduced by permission of Feminist Book Fortnight Group.

The Fortnight was supportive of and supported by the mainstreaming of feminist literature in the 1980s. Bookseller Jane Anger describes this mainstreaming as a ‘revolution from within’, a consequence in part of women editors establishing feminist lists at mainstream publishers such as RKP (Routledge and Kegan Paul) and Macmillan. As Anger remembers:

although it was vastly unequal in the publishing industry and men made most of the decisions … the women editors who were beginning to be in place … made the case within their own companies that this [feminist literature] was something good to publish … so there was some mainstreaming despite the fact that … most reps and editors and sales directors were men and didn’t have a clue about feminism. (Anger and Watts Citation2021)

The often-vexed relationship between feminist bookselling and the mainstream was itself a topic of discussion at FBF events. As well as book launches and readings, the Fortnight also hosted talks and discussions on the feminist book trade. In 1988 Sarah LeFanu, a senior editor of the Women’s Press, led an event titled ‘Feminist Publishing and the Market Place’ and chaired another titled ‘Women’s Writing: Into the Mainstream’, both of which were held in Bristol; and in 1989, Nicci Gerrard, the author of Into the Mainstream (Pandora Press), gave a talk in Ealing. It seems likely that, as the editor of a financially successful press, LeFanu’s views on women’s writing entering the mainstream corresponded to Gerrard’s celebration of the same (c.f. Murray Citation1998: 171). Indeed, Gerrard welcomes the mainstreaming of feminist literature as a counter-intuitively radical development, and a ‘broadening out from the literature of personal angst and domestic oppression’ (Citation1989: 14). Outside the UK, influential FBN founder Carol Seajay viewed the Fortnight as a commercial pipeline from the mainstream to more specialist booksellers, or in her words a ‘nifty way to support the stores that support radical feminist books and a way to direct those women who first discover feminist books at a chain store (that stocks only the Twenty Selected Titles) to the stores that offer a much broader range of feminist literature’ (Citation1988: 10). The pipeline ran both ways. As Anger puts it:

it’s about changing the publisher’s mind, and if you change publishers’ minds then you get books out to a wider audience … by distributing [feminist titles] in a wider way to WH Smith’s and other bookshops and making Dillons [a high-profile British bookstore chain] stock them. (Anger and Watts Citation2021).

want [their] books not just to be in the radical shops … want them to be accessible … if people don’t see their books in Smith’s, they don’t know they’re there … getting those books on the shelves for FBF was key … especially for working class writers … FBF in the 80s was as much about distribution and placement as it was about publishing. (Anger and Watts Citation2021)

Others in the feminist and radical bookselling movement were strongly opposed to FBF’s more commercial aspects and, as Gerrard observes, the ‘Fortnight [became] an international forum for feminist debate—and sometimes fierce argument’ (Citation1989: 59). In 1986, Grace Evans, a member of the Spare Rib editorial collective at the time, wrote a feature on FBF for Spare Rib which weighed the benefits of the increased visibility of feminist literature against the disadvantages of feminist books becoming governed by commercial imperatives.Footnote14

In Evans’ article, WH Smith’s sponsorship of the Fortnight is characterized as a cynical development. ‘[B]efore feminism became a watchword for “big sales”’, Evans wrote, Smith’s ‘were reluctant to distribute or feature feminist material’—indeed, Smith’s notoriously refused to stock some issues of Spare Rib in its early years (SR June 1986: 23; Chambers, Steiner and Fleming Citation2004: 165). Her concerns resonate with those expressed by the North American Women in Print activist Charlotte Bunch, who argued in 1977 that feminism had to maintain its literary counterpublics not ‘just because the boys won’t print us’, but because ‘today they will print us [but] for money, not to advance feminism’ (qtd in Travis Citation2008: 281). Evans goes on to draw attention to the adverse effects of the absorption of FBF marketing into the mainstream: some radical booksellers participating in FBF, according to Evans, reported no increase or even a drop in sales, as a consequence of their specialist titles becoming easier to obtain. A report on the women’s workshop at the FRB conference 1985 concurs that while the ‘Selected Twenty’ promotion helped with sales at some shops, with the demand for books from the Women’s Press increasing dramatically that year, other shops ‘didn’t notice any difference’. The same report also asks:

should next year be a year off in this country? A suggestion to do the list again but to promote radical bookshops in it this time. It might go a small way to helping the problem whereby we do all the work and the straight bookshops cream off all the profit … but, they do make these books accessible to women.Footnote15

The Selected Twenty

As a key aspect of that publicity strategy, the ‘Selected Twenty’ titles promotion bears further examination. Every year, the ‘Selected Twenty’ were chosen by an independent panel of booksellers and librarians from among the submitted titles in the FBF catalogue as those ‘which best represent the range and strength of feminist books’ published in a given year (SR June 1985: 43). These titles were given special prominence in the publicity for FBF and featured a range of fiction and non-fiction including, in different years, Toni Morrison’s Beloved (Chatto and Windus 1988), Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye (Bloomsbury 1989), Phyllis Chesler’s Sacred Bond: Motherhood Under Siege (Virago 1990) and anthologies Truth, Dare or Promise: Girls Growing Up in the 50s (Virago 1985) and Watchers and Seekers: Creative Writings by Black Women (The Women’s Press 1987). Anger explains that these twenty titles were intended, very practically, as a guide for shops and retailers who did not usually stock feminist titles. Farooqui, one of the ‘Selected Twenty’ panellists for FBF 1989, likens the ‘Selected Twenty’ to a feminist Booker longlist (Citation2022).Footnote17 Farooqui remembers lengthy panel meetings being held in a members’ club on Audley St as an indication of the seriousness and prestige the organizers wished to confer on women’s writing. ‘Selected Twenty’ panels were conscious, too, of the need to make chosen titles accessible by choosing as many (cheaper) paperbacks as possible. Although the ‘Selected Twenty’ promotion was clearly successful, and a defining feature of the Fortnight, there is some evidence of feminist discomfort even on the part of the Fortnight’s organizers and supporters with the ‘Selected Twenty’ concept.

Figure 10. ‘20 Selected Titles’, FBF catalogue 1985. Reproduced by permission of Feminist Book Fortnight Group.

Figure 11. ‘20 Selected Titles’, FBF catalogue 1988. Reproduced by permission of Feminist Book Fortnight Group.

In the August 1990 issue of FBN, Spedding describes the ‘Selected Twenty’ as representing not ‘“the best” feminist books published; but rather a platform celebration of the many excellent books written and produced by women during the last year’ (Spedding Citation1990: 47). In this characterization, Spedding is careful to shift the emphasis from what Barbara Burford describes as the ‘unsisterly competitiveness of the star system’ to the celebration of collective endeavour (Citation1988: 99). In 1991, Spedding again acknowledges that the ‘Selected Twenty … is in its very essence a difficult concept, of course’ (SR June 1991: 29).Footnote18 Nevertheless, the ‘productive paradox’ of the ‘Selected Twenty’ promotion continued up until the last year of FBF and even beyond. In 1992 (by which time Spare Rib had ceased publication), in lieu of an organized event, the news and current affairs magazine Everywoman published its own list of twenty selected titles and encouraged bookshops, libraries and women’s groups around the UK to continue to celebrate the Fortnight (FBN August Citation1992: 41).Footnote19

The promotion of individualism was not the only reason some feminists took issue with the ‘Selected Twenty’ titles; another was unrepresentative selection panels. Notwithstanding the range and diversity of the ‘Selected Twenty’ titles, Spare Rib’s listing for FBF 1991 draws attention to the fact that that year’s selection panel included no Black women (SR June 1991: 29). At the first IFBF in 1984, Audre Lorde famously denounced the Fair’s white, exclusionary organizing structures. Seven years on, at a moment when feminist activism was in serious decline, the Spare Rib collective preface the FBF listings with their assessment that ‘virtually no progress has been made’ (SR June 1991: 29). At times, the FBF selection panel was more diverse and in 1988, the panel included two Black women—Sylvia Parker of Sisterwrite Bookshop and Kathy Watson of The Voice (Seajay Citation1988: 9). But what were the ramifications for a promotion that marketed itself as a platform for Black women’s writing, when Black women did not always have control of the decision-making process? As Simone Murray points out, ‘crucial to the emergence of a distinct black feminist voice since the 1960s has been the concept of authenticity—that representations of black women and their experiences should be self-determined’ (Murray Citation2017: 184). The chosen titles, year after year, demonstrate that writing by Black (often African American) women was recognized as being of great importance to the women’s movement and, moreover, highly marketable. As Francesca Sobande has discussed, ‘the publication of writing by Black women … helped to financially sustain feminist publishers such as the Women’s Press and Virago in the 1980s and beyond’ (Citation2021: 400); and Burford articulates how, after Alice Walker’s The Color Purple won the Pulitzer Prize, ‘Black women’s writing has been used to convey radical chic by so many’ (Citation1988: 97). But without the consistent input of Black women, the ‘Selected Twenty’ could not be said to be truly representative of the ‘range and strength of feminist books’.

The problem of institutional whiteness within the feminist book trade was not limited to the Fortnight. As Spare Rib reported, feminist publishers remained overwhelmingly white, with the exception of explicitly multi-racial or Black feminist publishers such as Sheba (of which Spedding was a founding member) and Black Womantalk (SR May 1991: 11–12). The Spare Rib FBF listing of 1991, which was to be the last year the Fortnight ran, does recognize the promotion’s contribution as well as its failings, concluding that ‘the now long-established Feminist Book Fortnight and International Feminist Book Fairs have done a great deal to promote feminist publishing’ (SR June 1991: 29). That importance took on more acute significance in a year when feminist publishing ventures, and the larger women’s movement, were struggling. The Women’s Press was undergoing a resignation crisis in 1991, and the book industry had been hit hard by the wider economic recession (Murray Citation1998: 188; SR May 1991: 10). Moreover, according to Farooqui, as ‘women’s literature was taken up by the mainstream publishing and bookselling world’ the increase in competition meant that running a feminist bookshop was no longer viable (Chester and Oldziejewska Citation2020). While the Fortnight struggled to diversify its ‘Selected Twenty’ promotion, its products and its larger organizational structure were more diffuse and not confined to a single group. In the final part of this article I will examine the regional organization of the FBF, what this meant for Black feminists who participated in the Fortnight, and the geographies of the Fortnight’s regional feminist counterpublics.

Mapping Feminist Book Fortnight’s Regional Counterpublics

The non-commercial ends of the Fortnight’s commercial means were the establishment of local, recurring feminist counterpublics across the UK, supported by a form of ‘municipal feminism’ (which I discuss at greater length below).Footnote20 Of the Feminist Book Fair, Spedding wrote that ‘we were also determined to achieve a truly international political women’s event’ (SR June 1988: 26). To realize this internationalism, the biennial Book Fair travelled abroad, to Oslo, Montreal, Barcelona, Amsterdam and Melbourne, while FBF continued to be held yearly in towns and cities across the UK. Following the ‘resounding success’ of the first Book Fair and accompanying Book Week, a Spare Rib listing announced that ‘the demand for some sort of follow up promotion from booksellers, libraries and local groups was too great to ignore and so a group of publishers and booksellers have organized Feminist Book Fortnight ’85’ (SR June 1985: 42). The second Fortnight is characterized here as meeting a specifically local demand. In 1984, Susan Ardill similarly emphasizes that the Book Week will be ‘regionally organised’ (SR June 1984: 21). No fewer than 40 autonomous groups, co-ordinated in that first year by Gail Chester, were involved in this organization (Seajay Citation1984: 14). Evans’ 1986 feature on FBF defined its greatest strength as that of outreach beyond the metropolitan centres to those women who ‘usually have to search high and low for feminist reading material’ (SR June 1986: 22). However, as noted above, FBF events were not merely regional—they joined the local with the international. In 1988, the FBF catalogue reported that their ‘ongoing success’ has resulted in ‘other international connections’ including a Feminist Book Fortnight being celebrated concurrently in Bangladesh, and a Feminist Book Week in New Zealand which would be held later in the year (FBF catalogue 1988: 2). The organizational structure of the Fortnight invoked what feminist geographer Doreen Massey (whose work on feminist geography and local specificity was especially influential in the 1980s) terms a ‘global sense of place’—a non-reactionary, extroverted localism that is conscious of its links to the wider world (Massey Citation1991).

What were the contexts of FBF’s highly localized structures? By the mid-1980s, the pioneering work of the Greater London Council had ‘sensationally showed what “municipal feminism” could achieve’ through their support of 400 women’s projects between 1982 and 1985 including feminist bookshops such as Sisterwrite (Jolly Citation2020: 128; c.f. Chester and Oldziejewska, Citation2020). The GLC’s example inspired women’s initiatives in local government across the UK, including in Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Birmingham, Cardiff and twelve of Scotland’s local authorities by 1990 (Lovenduski and Randall Citation1993: 198–204). The attempt in Leeds to ‘feminize’ the local state has been discussed by Sue Bruley, who identifies several instances of feminist organizing being shaped by local priorities and reminds us that national events such as the WLM conferences were regionally organized (Citation2016: 733–34). It is the regional, rather the state-assimilationist, tendencies of municipal feminism that characterized the Fortnight.

As a funder of the first IFBF, GLC grant aid helped to launch the regionally organized feminism of FBF; and minutes from national and regional FBF planning meetings show that organizers applied for, and secured, regional arts funding.Footnote21 Two such regional organizers were Gay Jones and Prudence de Villiers, who founded the long-running feminist bookshop In Other Words in Plymouth in 1982. Two years after the bookshop was opened, De Villiers and Jones took on the role of regional organizers for the Fortnight across Devon and Cornwall—a region ‘less well provided’ with radical bookshops than the rest of the UK (Jones Citation2021). This involved writing grant applications, managing costs, corresponding with librarians, authors and the media, advising other booksellers, and organizing publicity. In their application to South West Arts for £500 of grant funding, de Villiers and Jones emphasize the national reach of the Fortnight as well as its economic benefits:

as you can see, this whole event is being planned on a very ambitious scale, and should make an impact all over the country … We are optimistic that Feminist Book Week will provide a major focus of interest for people in the South West and a boost for the book trade locally.Footnote22

Maps were integral to the Fortnight’s regional organization from the very beginning. Chester, the regional co-ordinator in that first year, pinned up a map on the office wall with each of the 16 regions into which organizers had divided the country marked out; meeting minutes contain reports and updates from each of the 16 regional areas.Footnote23 The much newer Spare Rib map, built by the Business of Women’s Words project in partnership with the British Library in 2020, visualizes the distribution of local Fortnight events across the country not only for that first year, but for its entire run.Footnote24 There are clear clusters of Fortnight events, for example, in the North-West and South-West, as well as in London. The Spare Rib map is also indicative of the outward-looking, non-reactionary localism fostered by the Fortnight. While at first glance it shows clusters of local activity, the description attached to each datapoint reveals the extent of the cultural travelling taking place across the UK. For example, in Liverpool in 1984 the line-up of speakers for what was then ‘Feminist Book Week’ included Egyptian feminist Nawal El Saadawi and prizewinning British author Pat Barker alongside ‘local women writers’ (SR June 1984: 30). However, not every FBF event was listed in Spare Rib, in part due to the long lead times for printing which meant many listings were not confirmed in time. The Spare Rib listings advise that a ‘full national programme’ can be obtained from the FBF co-ordinating group—as a result, the map shows only some of the FBF activity which flourished throughout the 1980s.Footnote25

Feminist geographer Gillian Rose characterizes feminist maps as ‘multiple and intersecting, provisional and shifting’, and the mapped listings for FBF are certainly that, due to the changing nature of Spare Rib listings over time (Rose Citation1993: 155). The early Spare Rib FBF listings were organized by location, but from 1988, as the event expands, the listings began to be organized by date. The shift from listing by place to listing by time reflected the Fortnight’s growth as it became a fixture of the feminist calendar. But this did not mean it lost its regional significance. Indeed, its determinedly local operation proved the possibility of a progressive regionalism and spatially-tuned politics.

What then constitutes a progressive, outward looking, ‘global sense of place’ (Massey Citation1991) that is not reactionary or insular? This is a question that threads through the latter issues of Spare Rib magazine and the women’s movement in the 1980s. Heated and often painful debates over Spare Rib’s increasingly international focus played out in the letter pages and while some readers complained that there was too little content ‘to do with Britain’, others praised Spare Rib for reminding ‘those of us born British that we are living on a small and not so very important island’ (SR October/November 1982: 4). Back in 1984, in the same June issue that launched the IFBF and Feminist Book Week, a reader writes that Spare Rib is too London-centric and asks ‘does so little activity happen outside the grey metropolis?’ (SR June 1984: 3). In the call-and-response so characteristic of Spare Rib’s letters and listings sections, the Fortnight offered precisely that: hundreds of regional events spread across the UK. Feminist network-building in the regions was not a new idea; connecting and embedding local networks had always been of great concern to Spare Rib, which regularly ran advertisements asking readers to ‘Help us put Spare Rib in your local bookshops and on the newsstands’ (SR June 1989: 5) as well as its ‘region by region campaign to gain more readers and contributors’ launched in 1976. Taking place as they often did in radical bookshops, Fortnight events inhabited what were often already countercultural hubs and sites of struggle (radical bookshops were frequent targets of racist and fascist attacks throughout the 1970s and 1980s (see Delap Citation2016)) but they also constructed new local counterpublics or ‘meeting places’ that allowed what Massey calls ‘a sense of place which is extroverted’ without erasing geographical difference and specificity. In 1986, in a sign of the locality and the times (a year on from the miners’ strike of 1984–85), Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre featured a collection of writing by the Sheffield Women Against Pit Closures Group as part of the Fortnight, alongside ‘national women writers’ such as Zoe Fairbairns.Footnote26

There are many more examples of where the Fortnight fostered a progressive and outward sense of place. On the map, the university cities of Dublin, Edinburgh, Bristol, Manchester and Plymouth stand out as hubs of feminist literary activity. In Dublin, FBF events involved collaborations with local presses, including Arlen House and Wolfhound Press; ‘alternative’ academic seminars, including one on the early women’s movement in Ireland and Irish nationalist Anna Parnell; readings by writers from the local community; a talk given by an American feminist academic; collaborations with the Alliance Française, and poetry readings by American poet Marilyn Hacker and Irish poet Eavan Bolan. Edinburgh’s FBF events similarly combine the local—the launch of a book of contemporary writing by Scottish women; readings by Scottish authors Liz Lochhead, Janet Paisley and Rosa McPherson—with the international: a book signing with Maya Angelou. In Bristol, The Watershed boasted a truly star-studded line-up in 1987 with Marge Piercy reading from Gone to Soldiers, a Margaret Atwood reading, Marina Warner in discussion with Michèle Roberts and Sarah Lefanu, and Wendy Mulford and Leah Fritz giving a poetry reading. In 1989, Bristol’s Arnolfini Gallery hosted an event with experimental American writer Kathy Acker as part of the Fortnight. In Manchester, FBF authors ranged from Suniti Namjoshi (1990) to Carol Ann Duffy (1989); an event on cartoon humour; readings from local community writing groups, including Manchester poets such as Sujata Bhatt and Debjani Chatterjee; and a reading by Gillian Slovo, a South African (but British-based) novelist. In Plymouth, In Other Words hosted a wide array of events, from a book signing by Susie Orbach to an event with Wages for Housework campaigner and author Selma James to a local women writers’ evening.

The joining of the local with the national or even international in this way testifies to Fortnight’s aim to reach women for whom feminist literature was not readily available. Unlike regional literary festivals, this was a promotion of and via many places, and a precursor in the UK of Black History Month, which ran in Britain for the first time in 1987. As discussed above, the driving force behind the Fortnight in the 1980s was shifting focus away from the London-centric publishing scene and making feminist literature as accessible as possible. To that end, the organizers circulated lists of authors who were prepared to travel, or of feminist publishers who were prepared to send their authors outside London—a list which may have included writers such as the Grenadian poet Merle Collins, who gave Fortnight readings in Nottingham, Huddersfield and Durham. As well as remembering the visits of international authors such as El Saadawi during the Fortnight, FBF organizer Watts spoke of the importance of local geography to independent bookshops, whose fortunes were so dependent on passing trade. Watts gives as an example the diversion of a pedestrian and cycle route away from York Community Bookshop’s shopfront which had an ‘enormous [negative] effect’ on trade. The hugely successful Silver Moon Bookshop, unusually for a radical bookshop, was located on a main artery (Charing Cross Road) rather than a cheaper side street as a consequence of its building being GLC-owned. Local geographies also made themselves felt through the very physical labour of organizing Fortnight events. Watts memorably describes this labour as ‘footslogging’, from putting up posters around a town or city to organizing the printing of those posters and visiting venues to book them for an event. In Watts’ words, ‘everything was physical, there was nothing virtual, nothing digital, nothing, and it’s so hard to even imagine that now, but … that history is just so important, to remember the physicality of it’ (Anger and Watts Citation2021). Regional organizers started preparing for the Fortnight five or six months in advance, all coordinated by post and telephone. The booksellers I interviewed spoke of their exhaustion by the end of the Fortnight, having run the promotion on top of the day-to-day work of running a bookshop: as Farooqui recalls, ‘I never worked so hard in my life’ (Citation2022). The sheer physicality involved in selling women’s writing may be understood, to paraphrase Forster, as ‘inherently part of the feminist struggle’ (Citation2016: 813).

Records of the new publics reached through ‘footslogging’ are not readily available, although Chester does record the setting up of new women’s writing groups in Bangor, Dublin, Nottingham and Plymouth following the first Book Fair and Book Week in 1984; and ‘lots of books being sold, and not always to the predictable audience’.Footnote27 Another possible audience is suggested by the British author Barbara Burford, who was born in Jamaica and moved to the UK at the age of ten. In July 1986, Burford gave an interview to Spare Rib about her new book The Threshing Floor (Sheba) a collection of short stories and a titular novella which explores different aspects of Black women’s lives. During the interview, Burford says that she will tour the country with The Threshing Floor during FBF and adds that ‘I think it is very important to reach women outside London, particularly black women’ (SR July 1986, 36). Here Burford echoes Maud Sulter’s assessment in Citation1986 of the need for literature about Black British women’s lives outside London and the South East. A brief reading of Burford’s text can here counter the potentially ‘flattening’ effects of mapping and acts as an example of how a sense of ‘plurilocality’ is needed to indicate the ‘diverse spatialities of different women’ (Rose Citation1993: 151). The Threshing Floor is itself about the experience of moving to the countryside as a Black womanFootnote28—specifically, to a village in Kent where the Black protagonist, Hannah, endured ‘nudges and the whispers, the deliberately meant to be overheard comments, the silences; all the things that had haunted and made her first year in the valley hell’ (Burford Citation1986: 109). Hannah’s lover, Jenny, originally ‘fled to London to escape all those village attitudes’ but found that she was not a ‘cosmopolitan woman’ after all and returned to the Kent village where she was born, taking Hannah with her (Burford Citation1986: 159). The novella is no advert for a move to the country; towards the end, Hannah says that ‘“I don’t think I’d raise a child here … she’d be too isolated from other Black people”’ (Burford Citation1986: 203). What sort of connections, and overcoming of isolation, does such fiction afford? Reading is often understood as a means of seeking identification, of forging affective connection to other lives, and this function is frequently framed in ethical terms. But FBF made this a practical as well as metaphorical possibility. In her interview, Burford suggests that it is not only her fiction but her physical presence that might ‘reach [Black] women outside London’, and it was this combination of literal cultural travelling as well as the books and novels themselves which forged the Fortnight’s feminist literary counterpublics.

In this way, FBF performed a form of literary outreach that was distinct from other forms of feminist organizing. One of the main criticisms of the first IFBF was that Black women could not get into its most popular event—a reading by Audre Lorde—and that it gave a platform to high-profile authors of colour such as Alice Walker and El Saadawi, but not to Black British women authors (Withers Citation2018: 150). While the Fortnight did platform writers such as El Saadawi, who was hosted by News from Nowhere and York Community Bookshop in 1984, it also featured Black British writers such as Burford, as well as local writers such as the Manchester Poets. Launches of or readings from books of Black or lesbian voices published by the mainly London-based British feminist press, such as Charting the Journey: Writings by Black and Third World Women (Sheba 1988) and The Pied Piper: Lesbian Feminist Fiction (Onlywomen Press 1989) toured the country and feature large in the Fortnight’s events.Footnote29 But the Fortnight was not merely a proselytizing programme which brought metropolitan writers and their writings to the regions; the Spare Rib map reveals a whole network of local feminist businesses in the 1970s and 1980s which engineered and stimulated literary production and distribution across the country. The Fortnight’s regional organizational structure, and the local feminist or radical booksellers on which its events and sales depended, embedded the production and consumption of feminist literature within their local communities.

As this article has discussed, FBF’s main strength was its joining of feminist enterprise with geographical reach. The Fortnight supported the production and dissemination of feminist literature by harnessing the commercial power of the mainstream booktrade and inhabiting the extraordinary ecology of feminist authorship, publishing and bookselling that existed at this time. Its innovative marketing methods utilized commercial logics to the non-commercial end of cultivating local feminist literary counterpublics across the country, and thus extended and embedded regional feminist networks. FBF, like other sustained attempts to build feminist regional networks such as Spare Rib’s regions campaign, did not always succeed (as we have seen) in bridging geographical, classed or racial divides. But the uniqueness of the Fortnight’s contribution to the construction of feminist spaces lay in its national synchronicity—hundreds of events taking place across the country simultaneously—its global sense of place, and its propagation of the particular form of affective connection that works of literature can create.

Feminist Counterpublics in the Digital Marketplace

The recent revival of the Fortnight faces new, contemporary challenges: the literary marketplace is now a crowded promotional space and the economic climate is not friendly to local, independent enterprise. Yet the advent of the internet has seen a proliferation of micropublics which ‘niche’ booksellers, such as In Other Words (which still sells books online) can more easily find; Jones remarked that 2020 had been the busiest for feminist book sales since the bookshop closed in 2007. This still undiluted thread of pre-financialised, independent marketplace has been able to find a contemporary echo and support too in the surprise revival of independent bookshops. Despite recent challenges, there are now 967 independent bookshops in the UK, up from 868 in 2017 (Flood Citation2021). There are important differences between the original and today’s Feminist Fortnight: the revival is decentralized, with no central organizing group or ‘Selected Twenty’ promotion. Each shop organizes its own events and promotes titles of its choosing, with Five Leaves providing posters for each shop and posting event listings on a dedicated website. While the original Fortnight relied on support from mainstream booksellers like WH Smith, the revived Fortnight is deliberately aimed at independent booksellers, from Housmans Bookshop in London to Lighthouse Bookshop in Edinburgh and Libreria Marco Polo in Venice.

The reassertion of FBF as a political project—itself a response to the frustration Anger felt at the lack of advances in feminist publishing since the 1980s (Onwuemezi Citation2018)—has coincided with the political revival of feminism and global movements such as #MeToo. In the wake of this revival, the number of feminist presses, libraries and bookshops has also grown, with new UK additions including the London-based Silver Press and Second Shelf bookshop, Brighton’s The Feminist Bookshop and Afrori Books for Black authors, new annual feminist literary festivals such as New Suns and Suffolk-based Primadonna Festival, Black Feminist Week and the expansion of the Feminist Library, now housed in Peckham, South London. To paraphrase an argument from Hogan (Citation2016), the Fortnight’s great strength (combining both its geographical outreach and economic success) was that it drew on a whole ecology of feminist bookselling, writing and publishing, and thus benefitted from a collective dialogue and a shared accountability, as the pages of Spare Rib show. The activist aims of recent enterprises, such as Silver Press which aims to ‘reach[…] beyond mainstream publishing and mainstream feminism’, resonate politically with the newly revived Fortnight’s independence from mainstream booksellers. The ‘renewed infrastructure’ (Chester Citation2020: 39) of feminist presses, libraries and bookshops in the twenty-first century offers an arena in which to reclaim at least some of the means of production from the onslaught of corporatization and neoliberalism. At a time when a mainstream feminism ‘dominated by white and privileged women’ sets the agenda for parliamentary politics, institutional reform or corporate equality work (Phipps Citation2021: 34, 5), there is an ever greater need for spaces for the more marginal, less mainstream feminisms that might otherwise be lost—the sorts of spaces that initiatives such as the Fortnight, with its enduring distinctive regionalism and complex negotiation of feminist publishing and consumption practices, have long helped to create.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to my colleagues on the Business of Women’s Words project, especially Margaretta Jolly and Lucy Delap for their valuable and generous feedback on this article; to Jane Anger, Jane Cholmeley, Gail Chester, Ferha Farooqui, Gay Jones, and Jane Watts for generously sharing their memories and personal archives; to all those who have granted kind permission to reproduce images; and to the Leverhulme Trust [grant number RPG-2017-218] and Northumbria University for funding the project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Spare Rib referred to henceforth as SR.

2 While Nigerian-born Emecheta lived and wrote in Britain, many of her novels focus on the role of women in Nigerian society.

3 See Laurel Forster on how constructing the means of communication was integral to the development of second-wave feminism (Citation2016: 813).

4 Cf. Spare Rib map (2021), British Library, https://www.bl.uk/spare-rib/map (accessed 7 October 2022).

5 It was however far from the only book trade promotion event in operation at that time: Granta’s ‘Best of Young British Novelists’ promotion was established in 1983, as was the Trask Award; the Whitbread Awards increased their allocated prize money substantially in 1985; and the Commonwealth Writers Prize was established in 1987 (Todd Citation1996: 101, 86–7, 91).

6 Spedding had a reputation among Spare Rib collective members for having a shrewd head for business and negotiation—Róisín Boyd attributes the take-up of Spare Rib by Comag, the Cosmopolitan distributor, to Spedding in an interview by Zoe Strimpel for The Business of Women’s Words: Purpose and Profit in Feminist Publishing oral history project, reference C1834-05 © the British Library and the University of Sussex.

7 WH Smith sales had long been used as a yardstick for success in the world of feminist publishing; Marsha Rowe used it as a measure of how well Spare Rib was distributed, and the authors of Rolling Our Own: Women as Printers, Publishers and Distributors note that Sheba’s first book, Sourcream, sold well because Smith's stocked it; as did the journal Camerawork (Cadman, Chester and Pivot Citation1981: 38, 90).

8 Gail Chester, personal archive, IFBF ‘Minutes of Meeting held on 26th July 1983’.

9 See Todd on the ‘development of a “meet-the-author” culture’ as a ‘major change [in British publishing] since the late 1980s’ (Citation1996: 100).

10 Feminist Bookstore News henceforth referred to as FBN.

11 Letter from Spedding to FRB 1988, Working-Class Movement Library (WCML), Salford, org/radbook/5/2 box 8.

12 Cf. Women in Publishing: An Oral History. https://www.womeninpublishinghistory.org.uk/ (accessed 25 October 2022).

13 Cf. Bird (Citation2003).

14 Delap (Citation2021) traces the move from a more to less commercial basis for the magazine as it gained public funding and its related changes in collective membership.

15 ‘FRB Conference July ’85 Workshop Notes’, WCML, Salford, org/radbook/1/3.

16 Minutes of FRB Annual Conference 1986, WCML, Salford, org/radbook/1.

17 Richard Todd describes prominent literary awards such as the Booker Prize as ‘associated in the public mind with the entrepreneurship that characterized the Thatcher decade’, and its shortlist as a ‘consumers’ guide’ or ‘commercial “canon”’ (Citation1996: 61, 71).

18 Indeed, feminist author Alison Fell dubbed the Fortnight ‘Paranoia Book Fortnight’ for this reason (Gerrard Citation1989: 60).

19 Everywoman, set up in 1985, was ‘informational and liberal in approach’ (Chambers et al Citation2004: 152).

20 For a longer discussion of ‘municipal feminism’ and its relation to the WLM, c.f. Ross (Citation2019).

21 Gail Chester, personal archive, IFBF ‘Minutes of the Meeting held on 4th October 1983’; Gay Jones, personal archive, ‘Minutes from Planning Meeting held at A Woman’s Place’, 1984.

22 Gay Jones, personal archive, application for funding from South West Arts, 1984. For a history of In Other Words, c.f. Jones Citation2021a.

23 Gail Chester, personal archive, IFBF ‘Minutes of Meeting held on 6 December [1983]’ and ‘Minutes of the regional meeting, 24 January 1984’.

24 Search for ‘Feminist Book Fortnight’ on British Library’s Spare Rib map: https://www.bl.uk/spare-rib/map.

25 I have not been able to obtain copies of this ‘full national programme’, which remains elusive.

26 One regional campaign, contemporaneous with the establishment of the Fortnight, was Spare Rib’s support of the miners’ strikes of 1984 and 1985, a political event that dramatically drew the whole of the national imaginary toward the regions.

27 Gail Chester, personal archive, letter dated 21 June 1984.

28 Cf. Goldsmith (Citation1994).

29 Rose notes that titles such as Charting the Journey demonstrate the frequency with which feminist writing ‘makes use of spatial images’ (Citation1993: 140).

Works Cited

- Anger, Jane and Jane Watts (2021), ‘Interview 24 February 2021’, The Business of Women’s Words: Purpose and Profit in Feminist Publishing oral history project © the University of Sussex.

- Bazin, Victoria (2017), ‘“A New Kind of Trade”: Advertising Feminism in Spare Rib’, in Angela Smith (ed.), Re-reading Spare Rib, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 197–212.

- Bird, Elizabeth (2003), ‘Women’s Studies and the Women’s Movement in Britain: Origins and Evolution, 1970–2000’, Women’s History Review 12:2, pp. 263–88.

- Bruley, Sue (2016), ‘Women’s Liberation at the Grass Roots: A View from Some English Towns, c.1968–1990’, Women’s History Review 25:5, pp. 723–40.

- Burford, Barbara (1986), The Threshing Floor, London: Sheba.

- Burford, Barbara (1988), ‘and a Star to Steer her by’, in Shabnam Grewal, Jackie Kay, Liliane Landor, Gail Lewis and Pratibha Parmar (eds), Charting the Journey: Writings by Black and Third World Women, London: Sheba, pp. 97–9.

- Cadman, Eileen, Gail Chester and Agnes Pivot (1981), Rolling Our Own: Women as Printers, Publishers and Distributors, London: Minority Press Group.

- Chambers, Deborah, Linda Steiner and Carole Fleming (2004), Women and Journalism, London: Routledge.

- Chester, Gail and Magda Oldziejewska (2020), ‘Interview with SisterWrite Collective’, The Feminist Library, https://feministlibrary.co.uk/in-conversation-with-members-of-sisterwrite-collective/ (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Chester, Gail (2022), ‘Interview 24 September 2022’, The Business of Women’s Words: Purpose and Profit in Feminist Publishing oral history project © the University of Sussex.

- Chester, Gail (2020), ‘Culture vs Commerce: The Publishing of Feminist Books Since the 1940s’, in Laurel Forster and Joanne Hollows (eds), Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1940s-2000s, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 29–45.

- Delap, Lucy (2016), ‘Feminist Bookshops, Reading Cultures and the Women’s Liberation Movement in Great Britain c. 1974–2000’, History Workshop Journal 81:1, pp. 171–96.

- Delap, Lucy (2021), ‘Feminist Business Praxis and Spare Rib Magazine’, Women: A Cultural Review 32:3-4, pp. 248–71.

- DiCenzo, M., L. Delap and L. Ryan (2011), Feminist Media History: Suffrage, Periodicals and the Public Sphere, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Everywoman (1992), ‘Everywoman’s Selected Twenty’, Feminist Bookstore News 15:2, pp. 41–2.

- Fairbairns, Zoe (2017), ‘Feminist Publishing – Then, Now and in the Future’, talk presented at Five Leaves Bookshop/Nottingham Mechanics.

- Farooqui, Ferha (2022), ‘Interview 16 March 2022’, The Business of Women’s Words: Purpose and Profit in Feminist Publishing oral history project © the University of Sussex.

- Feather, John (2006), A History of British Publishing, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Feminist Book Fair Group (1984), 259: An Introduction to the World of Women’s Books, London: Calverts Press.

- Flood, Alison (2021), ‘Indie Bookshops Defy Covid to Record Highest Numbers for Seven Years’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jan/08/uk-and-ireland-independent-bookshops-defy-covid-19-100-closures (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Forster, Laurel (2016), ‘Spreading the Word: Feminist Print Cultures and the Women’s Liberation Movement’, Women’s History Review 25:5, pp. 812–31.

- Fraser, Nancy (1992), ‘Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy’, in Craig Calhoun (ed.), Habermas and the Public Sphere, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 109–42.

- Gerrard, Nicci (1989), Into the Mainstream: How Feminism Has Changed Women’s Writing, London: Pandora.

- Goodings, Lennie (2020), A Bite of the Apple: A Life with Books, Writers and Virago, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goldsmith, Jane Esuantsiwa (1994), Staring at Invisible Women: Black and Minority Ethnic Women in Rural Areas: Research Report, Twickenham: NAWO.

- Hanman, Natalie (2010), ‘The Return of Radical Bookshops’, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/apr/09/return-of-radical-bookshops (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Hogan, Kristen (2008), ‘Women’s Studies in Feminist Bookstores: All the Women’s Studies Women Would Come in’, Signs 33:3, pp. 595–621.

- Hogan, Kristen (2016), The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hollows, Joanne (2013), ‘Spare Rib, Second-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Consumption’, Feminist Media Studies, 13:2, pp. 268–87.

- Huntley, Eric (2021), ‘Books, Violence and Resistance’, Black History Walks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9bgeQPZn2x8 (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Jolly, Margaretta (2012), 'Recognising Place, Space and Nation in Researching Women's Movements: Sisterhood and after', Women's Studies International Forum 35:3, pp. 144–46.

- Jolly, Margaretta (2020), Sisterhood and After: An Oral History of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement, 1968-Present, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Gay (2021), ‘Interview 6 April 2021’, The Business of Women’s Words: Purpose and Profit in Feminist Publishing oral history project © the University of Sussex.

- Jones, Gay (2021a), ‘In Other Words’, Radical Bookselling History Newsletter, 2: 20.

- Loeb, Cathy (1984), Feminist Collections: Women’s Studies Library Resources in Wisconsin 6:1, p. 17.

- Lovenduski, Joni and Vicky Randall (1993), Contemporary Feminist Politics: Women and Power in Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Massey, Doreen (1994), Space, Place and Gender, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Massey, Doreen (1991), ‘A Global Sense of Place’, Marxism Today 28, pp. 24–9.

- Murray, Simone (1998), ‘“Books of Integrity”: The Women’s Press, Kitchen Table Press and Dilemmas of Feminist Publishing’, The European Journal of Women’s Studies 5, pp. 171–93.

- Murray, Simone (2017), Mixed Media: Feminist Presses and Publishing Politics, London: Pluto Press.

- Onwumezi, Natasha (2018), ‘Feminist Book Fortnight Launches this summer’, The Bookseller, https://www.thebookseller.com/news/feminist-fortnight-769166 (accessed 7 October 2022).

- Phipps, Alison (2021), Me, Not You: The Trouble With Mainstream Feminism, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Rose, Gillian (1993), Feminist Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge, Cambridge: Polity.

- Ross, Freya Johnson (2019), ‘Professional Feminists: Challenging Local Government Inside Out’, Gender Work and Organization 26:4, pp. 520–40.

- Seajay, Carol (1984), ‘The First International Feminist Bookfair’, Feminist Bookstore News 7:3, pp. 13–5.

- Seajay, Carol (1988), ‘Feminist Book Fortnight ’88’’, Feminist Bookstore News 11:1, pp. 9–10.

- Spedding, Carol (1990), ‘Feminist Book Fortnight ’90’’, Feminist Bookstore News 13:2, pp. 47–9.

- Sobande, Francesca (2021), ‘By Us, for Us? Past and Present Black Feminist Publishing Narratives and Routes’, Women: A Cultural Review 32:3-4, pp. 395–409.

- Sulter, Maud (1986), ‘Surveying the Scene: Writings by Women of African and Asian Descent’, GLC Women’s Bulletin, 27:March, pp. 28–9.

- Thomlinson, Natalie (2017), ‘“Sisterhood is Plain Sailing?” Multiracial Feminist Collectives in 1980s Britain’, in Kristina Schulz (ed.), The Women’s Liberation Movement, Impacts and Outcomes, New York: Berghahn, pp. 198–213.

- Todd, Richard (1996), Consuming Fictions: The Booker Prize and Fiction in Britain Today, London: Bloomsbury.

- Travis, Trysh (2008), ‘The Women in Print Movement: History and Implications’, Book History 11, pp. 275–300.

- Withers, D-M (2018), ‘The International Book Fair’, in Bonnie J. Morris and D-M Withers (eds), The Feminist Revolution: The Struggle for Women’s Liberation 1966-1988, London: Virago, pp. 150–3.