ABSTRACT

A deeper understanding of the pre-primary teacher’s profession is made possible by the use of pictures in pedagogical research, i.e. the hermeneutic analysis of symbols visually representing this profession. The study seeks comprehension through quantification of the thematic motifs in the students’ pictures (n = 132) as well as a detailed qualitative analysis of selected artefacts (n = 8). An interesting tension arises from the juxtaposition of the authors’ descriptions and the expert team’s interpretations. Thus, aspects of the profession that are at first glance absent from the research, such as spirituality, love, atmosphere, colour, airiness and horizon, emerge.

1. Introduction

In addition to the number of children in the classroom, the amount and focus of didactic resources, etc., teachers and their qualifications are undoubtedly structural indicators of the quality of pre-primary education (Slot Citation2018) and significantly determine its level. The way to reflect on pre-primary education and its quality is not only through representations of knowledge about the profession and subjective perceptions but also through the prejudices and opinion barriers of teachers themselves, as well as university students in the field. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the conscious and unconscious mental representations which female students in the field construct about the profession of pre-primary teacher (hereinafter P-PT), we chose the form of pictorial representations.

Most pre-primary children in the Czech Republic undergo some form of institutional pre-primary education, which is most often implemented in kindergartens. Since 2017, the year before entering the next level of education has had the character of an obligation, and the age of the child in relation to the legal eligibility for a place in a kindergarten has gradually decreased. Thus, P-PTs work with children from approximately 2 to 6 years of age, and they need at least a high-school diploma with a focus on P-PT training to be able to practice this profession.

For the last 20 years, however, Czech education policymakers have also been discussing the requirement for higher education for P-PTs (MŠMT Citation2001, MŠMT Citation2015). For almost 30 years, it has been possible to obtain this education, as 10 Czech universities offer the possibility of studying the field of pre-primary teacher education at the bachelor’s degree, and some even at the master’s degree, level. The model of key competences became the basis for the development of professional standards for teachers, which were intended to provide a definition of the quality of their professional performance. In the conditions of the Czech Republic, one sophisticated concept is the Framework of Professional Qualities of Teachers (hereinafter referred to as the Framework), which was conceived as a goal and a vision towards which the teacher is heading, thus emphasizing the dynamic concept of requirements for teachers expressing long-term direction and approaching the desirable parameters of the teaching profession (Tomková et al. Citation2012). The Framework was also adapted for the needs of pre-primary education (Syslová Citation2013).

A P-PT’s perception of the profession is naturally dependent not only on experience, expectations and social consensus but also on the depth of knowledge related to the activities a teacher has to perform. According to research findings, although the subjective perception of P-PTs in the Czech Republic is based on the social standing of the teaching profession among the general public as well as parents, it is marked more by professional marginalization, associated with a lack of appreciation and disrespect, which is embedded in the perception of the work of P-PTs as babysitting and playing with children (Majerčíková and Urbaniecová Citation2020). However, the educational and socialization dimension of pre-primary teaching, neglected by a part of society, integrates a number of sophisticated practices that optimally require university qualifications. Another research investigation involving students of pre-primary teacher education, conducted through thematic writing, shows that they see their future profession as a mission to prepare children for life, foster their personality development and prepare them for their role as primary school students (Wiegerová and Gavora Citation2014).

The view of the profession in the presented research is based on analysis of images that were intended to reflect the subjective representation of their creators – the student P-PTs. The subsequent interpretation of their images is based, with respect to the principles of depth-hermeneutics as applied to a text (Gripsrud, Ramvi, and Mellon Citation2018), on an attempt to go beyond the immediate latent meaning of a word or image and to remind ourselves that not everything we do or say is entirely conscious and rational (Jung Citation1964). We see the hermeneutic analysis and interpretation of images of the profession of P-PT as a way of entering into dialogue with the meanings in these images and as a platform for accepting and understanding the contexts of human experience.

With this in mind, the purpose of our study becomes an analysis and interpretation of the profession through pictures made by female students in the field, with a specific focus on the study of P-PT. In our research, we set the following objectives:

To reveal the key themes of the depiction of the profession of P-PT in the pictorial representations of female students in the field;

To capture the semantic enrichment of the declared conception through the symbolic pictorial representations of female students;

To compare student self-reflections and team reflections related to pictorial representations.

2. Methodology and methods

2.1. The research sample

For the purposes of this empirical investigation, students in selected years of the Bachelor’s degree program Teaching for Kindergartens and the Master’s degree program Preschool Pedagogy at the Faculty of Humanities, Tomas Bata University in Zlín, the Czech Republic, in both full-time and combined forms of study, were contacted. Out of the total 146 female respondents (no male students were currently in the group), 132 students agreed to cooperate and provided pictures. In this group of female respondents, 56 were in full-time study, and their teaching experience was limited to the experience gained during their studies; the remaining 76 respondents were in combined study, and most of them were in the profession of P-PT at the time of data collection, based on their secondary school qualifications. Twenty-two pictures were then selected for the purpose of hermeneutic analysis, eight of which are used within this study. Their authors are students in their first year in the previously mentioned study program.

The choice of the original 22 and the final 8 pictures presented here was based on the relative specificity and originality of the artists’ expressions. Primarily, pictures were selected in which less frequent meanings and unusual, relatively unexpected semantic connections appeared. Another criterion was the degree to which abstraction and symbolism gave the pictures new information. Last but not least, we were influenced by the search for pictures that were accompanied by comments from the artists where the words and the picture did not present the same latent meaning.

2.2. Data collection

A request to share research data was presented in March 2021, via email (via school addresses) and in person. Research participants were asked to produce pictures based on this instruction:

Please take a clean white sheet of A4 paper and draw a picture on the theme “profession of a pre-primary teacher”. The picture should take approximately 30-40 minutes to create and can be accompanied with a few words. You can work with any art supplies. Try to use at least six different colours.

2.3. Data analysis

The initial sorting of the data and arrangement into a categorical system was followed by a verbal description of each of the selected pictures, without a search for any meanings. The next step was a hermeneutic interpretation based on the method of free association of the selected pictures. The level of validity of the research was supported by triangulation from a four-member group of experts (educators with a background in pedagogy, psychology and philosophy and a practicing P-PT) who participated in the interpretation. The interpretation meeting was conducted in May 2021 through MS Teams, and a video and audio recording was made. A verbatim transcription of the interpretation record (13,661 words in Czech) was made, which was then reformulated with respect to the scope, continuity and clarity of the utterance, in an attempt to provide a coherent and meaningful description.

2.4. Ethical aspects and limits of research

During the conduct of the research, all the requisites of research ethics were respected, and the applicable principles and regulations for research involving human participants were followed. The student-respondents and the researchers belonged to the same university in Moravia and, in light of this, its code of ethics was taken into account (the code of ethics of this university is part of the statute of the university); the rules resulting from the Code of Ethics of Educational Research in the Czech Republic and the code of relevant international organizations were also determined (more in Průcha and Švaříček Citation2009). In order to carry out the research, the participants were required to agree to participate in the research and to share its results, and thus, their voluntary participation in the research was important. Ensuring their anonymity and safety with the option to withdraw from the research at any time was key. We were also committed to the confidentiality of both external and internal (i.e. among the research actors) information about the research process, especially in terms of the availability of information obtained in the research.

Reflection on the limits of the research led us to the sampling processes. In the construction of a research sample, the intentionality of sampling may indicate reduced credibility of the research investigation (Gavora Citation2015). In this case, it could have been the fact that the students were in the academic environment of one university, acquiring and deepening their theoretical knowledge and developing their pedagogical competences for working in pre-primary education. The student teachers had completed a part of their studies (both full-time and combined), and their attitudes and preferences within the topic, professional self-confidence and identity and evaluation of the experienced situations could have been influenced by the study and by meeting the authors of the study as their teachers.

Another limitation appears to be the selection of the analysed pictures. We deliberately present symbolically rich expressions, exceeding rational reportability with unambiguous formulations. Through this confrontation, we want to point out the poly-semantic characteristic of the symbols, which greatly enriches the overall tone of the research and thus the understanding of the profession of the P-PT. Indeed, many other representations reflect contents and meanings usually associated with pre-primary teaching, such as the persons of the teacher and the children, toys, educational areas, environment, etc. To avoid distorting the meaning by narrowing down to only selected pictures, we also present a descriptive analysis of all the data collected (see Table 2 in supplemental materials).

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative overview of the results of the initial analysis of the visual representation of the profession

We identified 68 thematic meanings in the pictures to which we assigned codes; these acted as the meaning unit of the input analysis. We then grouped the codes into 11 subcategories and 5 analytic categories. As part of the initial analysis of the pictures, we present a basic elaboration and summary of the results in a tabular summary (see Appendix 1, Table 2 in supplemental material).

The thematic richness, in some places even diversity, in the content of the student pictures resonates in the summary. In this simple enumeration, the individual codes already represent a view of the profession in its broadest sense. The relational and direct educational dimension of the profession emerges more strongly.

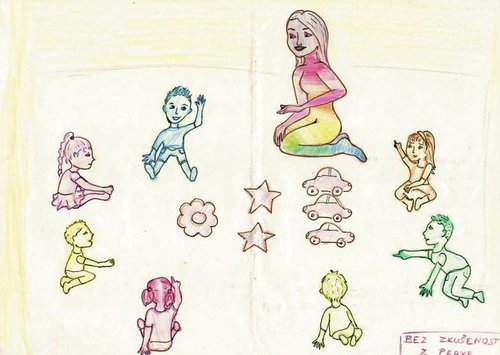

The key is the characters in interaction, which is most often visualized in various forms of teaching and socialization. The diversity of the characters is expressed not only by the different colours, sizes and shapes but also by the compositions in which they are placed. Almost half of the images carry positive emotions, most often represented by the characters smiling, jumping or raising their hands, and a heart symbol. In addition to the characters, the drawings usually show the implementation of a school programme, the main protagonist of which is a female teacher. Teaching is dominated by an artistic focus, developing literary as well as pre-math, physical and scientific literacy. The socialisation aspects of the school programme are expressed through sharing, mutual observation, communication, etc. In terms of the environment, the drawings usually offer the exterior (school garden, sandpit, playground and natural environment); the interior is readable through the seating area in a circle (on a carpeted area) or through characteristic elements (toys and books or tables and chairs, pictures, etc.).

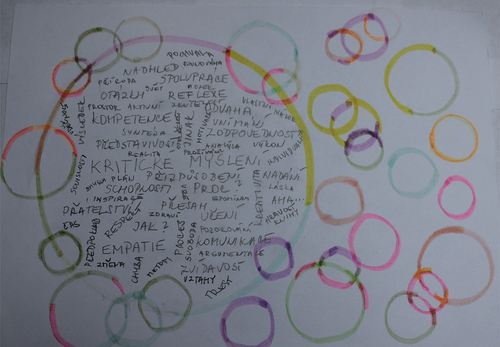

Approximately 3 out of 10 drawings did not use human figures. In these, the students chose abstract motifs with a combination of different colours, shapes and lines, using several artistic techniques. Extreme cases are represented by several highly symbolic drawings, such as a tree – a heart in its crown, a large palm offered, an avenue of trees with a path highlighted inside, only coloured concentric circles or a kind of coloured concept map resembling a sociogram.

Broader contexts, transformed into diagnostic, consultative or reflective activities of the teacher, appear less in the pictures. The dimension of the teacher’s cooperation with the parents of the children and the emphasis on the propaedeutic function of pre-primary education in relation to the child’s entry into primary school were also quite unexpectedly neglected. As these were university students preparing to work in pre-primary education, a link to innovative educational strategies applied within the profession (e.g. inquiry-based education) was also expected but did not appear much in the students’ representations.

3.2. Qualitative analysis of selected pictures

Many of the pictures are perceived as very successful artistically; several of them could withstand even more demanding professional criticism. Nevertheless, we leave the aesthetic or artistic effect of the pictures out of consideration, as we are focusing on the semantic aspect of the message. As already mentioned, 22 pictures were chosen for qualitative analysis, of which 8 were selected for public presentation through this study. In the following section, we copy only the pictures and summary their descriptions (). In Appendix 2, in the supplemental materials, we offer the full analysis of each image, following the scheme: (1) the insight into the student’s communication about the drawing and (2) the team’s interpretation of the drawing, modified by the authors of the study.

Table 1. Summary descriptions of pictures.

4. Discussion

The results obtained require more detailed interpretation in two directions. The first is the methodological dimension of this research; the second is the thematic enrichment, with new possible meanings obtained, thanks to the analysis of the visual data.

If positivist-oriented researchers will inevitably express dissatisfaction with the validity of such a research design, the increasing support for qualitatively oriented approaches from hermeneutically and phenomenologically grounded research strategies has been unmistakable in recent years. The interest in the intrinsic value of symbols that has been increasing since the middle of the last century (Eliade Citation1961; Jung Citation1964) is intensified in contemporary research approaches linked to the artistic component of human self-expression (Mitchell, De Lange & Moletsane Citation2017; Shanks and Svabo Citation2018; Thornquist Citation2015). These approaches have been used in pedagogical research, e.g. in outdoor education settings (Jirásek & Hanuš Citation2022; Jirásek et al. Citation2016), or in the representation of the recreation and leisure studies profession, in combination with the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) personality typology of students (Jirásek et al. Citation2021).

Adhering to certain methodological procedures of qualitative analysis interpreting the symbolic content of student pictures, we are faced with the question of the meaning and significance of the results of this research design. We consider it necessary to stress that the goal of hermeneutics – in contrast to the ambitions of positivism – is not objective measurement and the generalization of results into the form of a revealed explanation but a deeper understanding of the subsections of the reality under study, in our case the understanding of how students in the field of teaching in the primary school perceive their profession. This expands the overall horizon of consciousness and experience (in our case with the profession of the P-PT), a methodological theme coming from the background of phenomenology, drawing attention to the openness of the horizon not only of what is experienced directly but also of what is not directly experienced but which participates in the ordering of meaning, e.g. the past with our memories and the future of expectations (Husserl Citation1999). Thus, each particular has meaning only in the context of other possibilities, not only those remaining in consciousness but also the sensations, the hunches, the colouring of the atmosphere, all that constitutes the horizon of reference and meaning (Patočka Citation1998).

The purely abstract pictures illustrate aspects of the profession beyond what can be directly represented. At first glance and when simply described, a set of circles of different colours and sizes () may appear completely unrelated to the profession. Yet the deeper, symbolic interpretation points to important aspects of the profession that, when expressed in this way, enrich the verbal identification of the subject.

We believe that it is the students’ hermeneutic interpretations of the visual representation of the profession that allow for a deeper understanding of the profession. Here, too, as with the use of in-depth hermeneutic analysis of texts, socially repressed meanings emerge, and their potential for conveying a different, radical idea is revealed (Salling, Olesen & Weber Citation2012). They show the power, enthusiasm, energy and variety in the work of the P-PT while revealing the nature of the embodied, individual, unconscious, relational and social experience of the student herself. We will attempt to situate this special knowledge within the broader context of knowledge of the teaching profession we are exploring.

In our opinion, we can also perceive some international and transcultural parallels, similar to those brought about by the focus on identifying some research priorities, including the need to go beyond the mere quantification of courses and credits in these programs of study or to develop various tools to assess preservice students’ competencies, beliefs and attitudes (Horm, Hyson, and Winton Citation2013). Motivation for child care work is the most important characteristic predicting retention in the profession, more important than years of education, credentials or compensation (Torquati, Raikes, and Huddleston-Casas Citation2007). Love for children is the most important component of personality when deciding to choose this profession and study (Temiz Citation2018; Wiegerová and Gavora Citation2014), and a sense of belonging, course-specific activities at certain times and a mentorship programme are very important for retention in this study (Kirk Citation2018). If almost half of the pictures we analysed express positive emotions, joy, smiles or a dominant heart symbol in various ways, it is possible to interpret such results as joyful anticipation, no doubt enhancing motivation to pursue this activity. Explicitly expressed joy, a smile and a heart () refer to a positive atmosphere and spiritual aspects. Emotionality, relationship with children, joy and feelings of happiness from the presence of children resonate in another survey of Czech students of pre-primary teacher education, as an important motive for choosing this profession (Wiegerová and Gavora Citation2014). Teaching thus becomes an integrative quality, developing children’s diverse individuality ().

The relationship with children and the students’ perceived meaning and importance of the profession are essential for finding a strong personal attitude towards their chosen vocation. In fact, despite all the verbal assurances from politicians and rhetorical expressions about the necessity of this job, the prestige of the P-PT in the eyes of the general public is not very high, as this is manifested across cultural or geographical contexts. This is evident in the notion of babysitting rather than educating and developing children (Majerčíková & Urbaniecová Citation2020), in the professional undervaluation across countries (Gahwaji Citation2013; Vujičić, Boneta, & Ivković Citation2015) or in the incredible undervaluation characterized by the image of pre-school as the bottom and university education as the top, rather than the beginning and end of the educational journey (Gibbons Citation2018). Our respondents’ statements seem to provide a more optimistic picture: themes of arts, literature and pre-math education, physical and science literacy and socialization in outdoor and indoor environments emerge. A distinct development and growth () is made possible, especially by a loving relationship, although overcoming obstacles and negative feelings is part of the profession ().

The profession of P-PT still lacks an unquestionable definition, although the arguments for promoting child development in preschools, not only with regard to intellectual stimulation but also in relation to the inclusion of socially disadvantaged children in society, have been known for many decades (Heffernan Citation1964). The call to build our own paradigm of professionalism for the pre-primary education profession, especially in further clarifying meaningful relationships between child development knowledge and pre-primary teacher preparation, remains an unfulfilled vision (Goffin Citation1996), although we can perceive obvious progress and reforms over time (Lohmander Citation2004). The use of student pictures in pre-primary teacher education has become a part of these disciplinary transformations, with the combination of visual culture, multiple readings and situated knowledge seen as a sign of the shift to a postmodern paradigm in pre-primary teacher education (Ryan and Grieshaber Citation2005). Thus, a conceptualization of the profession not as a fixed and rigid monolith, but rather a dynamic field with values of symbolic and cultural capital, is emerging (Jackson Citation2017). The developmental aspect is also evident in the imagery of our respondents, including the necessary unveiling of this specific world hidden to the outside world behind the curtain () or the journey leading to the light of knowledge over time (). Effective pre-primary education is extraordinarily content-rich, yet inherently diverse, joyful and colourfully airy ().

However, the identity of a teacher is not something constant; it is formed and transformed during the course of study and later life. If, at the beginning of their studies, the position is evident mainly in an interest in didactic topics and firm statements of the moral essence of teaching, a smaller representation is revealed by students at the beginning of their studies in the curriculum or the context of the school and society as part of the teacher identity (Stenberg et al. Citation2014). The optimistic and joyful mood that can be perceived in the students’ visualized representations of the P-PT profession points to much broader concerns in the construction of teacher identity. The categories of people, emotions, environment and programme that emerge from the quantification of the various codes identified in the content dimension take on much richer and more plastic dimensions when looking at specific pictures. Most researchers would probably be reluctant to use these terms because they are not easily quantifiable : spirituality, love, relationship, atmosphere, joy, discovery, colour, variety, airiness and horizon. However, the students’ pictorial accounts testify that these qualities can also be rightly perceived as part of the profession of a P-PT.

5. Conclusions

The use of hermeneutic analysis and interpretation of the pictures of pre-primary teachers, who are also in the role of students improving their qualifications, has its practical application. The hidden potential of these practices stems from the assumption that teaching and learning involve complex relationships mediated by social and cultural contexts (Gripsrud, Ramvi, and Mellon Citation2018). This undoubtedly requires further investigation and analysis of the practices of pre-primary teachers themselves. We are inclined to conclude that the capacities of qualitative methods are unexhausted for these purposes and can be well applied in uncovering the often diversified processes and problems of professional practice (Dausien et al. Citation2008). One of them is the finding that even though the students in this research were students who had undergone didactic training with an emphasis on innovative strategies and approaches to the child as an actor in their education, similar motifs occurred only sporadically in their drawings. This is undoubtedly a signal of the need to think more thoroughly about the strategies and impacts of P-PT undergraduate training itself. It is clear from the drawings that each of the students is developing her own ideas and practices, styles and methods in the profession based on her own interpretations, experiences, values, preferences, and personal attunement. These then form the basis of the implicit theories of the teachers (Stephen Citation2012). What then emerges is the need to better connect them precisely with approaches that have the potential to move towards explicit theories that show some stability in early childhood education and thus contribute to its improvement through teachers. Thus, hermeneutic practices are undoubtedly a way of knowing, supporting and developing the reflective practice of pre-primary teachers and teacher candidates.

Author contributions

Ivo Jirásek: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Roles/Writing – original draft; Writing – review and editing; and Supervision; Jana Majerčíková: Data curation; Formal analysis; Project administration; Visualization; Roles/Writing – original draft; and Writing – review and editing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Magda Zycháčková, Renata Matušů and Klára Křivánková for their help in data processing and analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2022.2093336.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bílá kniha [White Paper]. MŠMT. 2001. Národní Program Rozvoje Vzdělávání V České Republice [National Programme for the Development of Education in the Czech Republic]. Praha: MŠMT.

- Dausien, B., A. Hanses, L. Inowlocki, and G. Riemann. 2008. “The Analysis of Professional Practice, the Self-reflection of Practitioners, and Their Way of Doing Things: Resources of Biography Analysis and Other Interpretative Approaches.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 9 (1): Art. 61.

- Eliade, M. 1961. Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gahwaji, N. 2013. “Controversial and Challenging Concerns Regarding Status of Saudi Preschool Teachers.” Contemporary Issues in Education Research 6 (3): 333–344.

- Gavora, P. 2015. “Obsahová Analýza V Pedagogickom Výskume: Pohľad Na Jej Súčasné Podoby [Content Analysis in Educational Research: A Look at Its Current Forms].” Pedagogická orientace 25 (3): 345–371. doi:10.5817/PedOr2015-3-345.

- Gibbons, A. 2018. “Not the Bottom, but the Beginning: The Failure of the Teaching Profession to Value Early Childhood Education.” New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work 15 (1): 5–9. doi:10.24135/teacherswork.v15i1.258.

- Goffin, S. C. 1996. “Child Development Knowledge and Early Childhood Teacher Preparation: Assessing the Relationship—A Special Collection.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 11 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(96)90001-0.

- Gripsrud, B. H., E. Ramvi, and K. Mellon. 2018. “Depth-hermeneutics: A Psychosocial Approach to Facilitate Teachers’ Reflective Practice?” Reflective Practice 19 (5): 638–652. doi:10.1080/14623943.2018.1538955.

- Heffernan, H. 1964. “A Challenge to the Profession of Early Childhood Education.” The Journal of Nursery Education 19 (4): 236–241.

- Horm, D. M., M. Hyson, and P. J. Winton. 2013. “Research on Early Childhood Teacher Education: Evidence from Three Domains and Recommendations for Moving Forward.” Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 34 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1080/10901027.2013.758541.

- Husserl, E. 1999. Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Jackson, J. 2017. “Beyond the Piece of Paper: A Bourdieuian Perspective on Raising Qualifications in the Australian Early Childhood Workforce.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (5): 796–805. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2017.1356575.

- Jirásek, I., I. Plevová, M. Jirásková, and A. Dvořáčková. 2016. “Experiential and Outdoor Education: The Participant Experience Shared through Mind Maps.” Studies in Continuing Education 38 (3): 334–354. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2016.1141762.

- Jirásek, I., T. Janošíková, F. Sochor, and D. Češka. 2021. “Some Specifics of Czech Recreation and Leisure Studies’ Students: Personality Types Based on MBTI.” Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 29: 100315. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100315.

- Jirásek, I., and M. Hanuš. 2022. ““General Frost”: A Nature-based Solution and Adventure Tourism: A Case Study of Snowshoeing in Siberia.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 46 (3): 490–517. doi:10.1177/1096348020934530.

- Jung, C. G. 1964. Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books.

- Kirk, G. 2018. “Retention in a Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood Studies) Course: Students Say Why They Stay and Others Leave.” Higher Education Research & Development 37 (4): 773–787. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1455645.

- Lohmander, M. K. 2004. “The Fading of a Teaching Profession? Reforms of Early Childhood Teacher Education in Sweden.” Early Years 24 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1080/0957514032000179034.

- Majerčíková, J., and K. Urbaniecová. 2020. “Prestiž Učitelství V Mateřské Škole Optikou Subjektivní Percepce Učitelek [Prestige of Teaching in Kindergarten through the Lens of Teachers’ Subjective Perceptions].” Studia Paedagogica 25 (1): 51–77. doi:10.5817/SP2020-1-3.

- Mitchell, C., N. De Lange, and R. Moletsane. 2017. Participatory Visual Methodologies: Social Change, Community and Policy. London: SAGE Publications .

- MŠMT. 2015. “Dlouhodobý Záměr Vzdělávání a Rozvoje Vzdělávací Soustavy České Republiky Na Období 2015-2020 [Long-term Plan of Education and Development of the Education System of the Czech Republic for the Period 2015-2020].” Praha: MŠMT.

- Olesen, S. H., and K. Weber. 2012. Socialization, Language, and Scenic Understanding: Alfred Lorenzer’s Contribution to a Psycho-societal Methodology. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13(3), Art. 22.

- Patočka, J. 1998. Body, Community, Language, World. Chicago, Ill.: Open Court.

- Průcha, J., and R. Švaříček. 2009. “Etický kodex české pedagogické vědy a výzkumu [Code of Ethics of Czech Educational Science and Research].” Pedagogická orientace 19 (2): 89–105.

- Ryan, S., and S. Grieshaber. 2005. “Shifting from Developmental to Postmodern Practices in Early Childhood Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 56 (1): 34–45. doi:10.1177/0022487104272057.

- Shanks, M., and C. Svabo. 2018. “Scholartistry: Incorporating Scholarship and Art.” Journal of Problem-Based Learning in Higher Education 6 (1): 15–38. doi:10.5278/ojs.jpblhe.v6i1.1957.

- Slot, P. 2018. “Structural Characteristics and Process Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: A Literature Review: Éditions OCDE/OECD Publishing. working paper.”

- Stenberg, K., L. Karlsson, H. Pitkaniemi, and K. Maaranen. 2014. “Beginning Student Teachers’ Teacher Identities Based on Their Practical Theories.” European Journal of Teacher Education 37 (2): 204–219. doi:10.1080/02619768.2014.882309.

- Stephen, C. 2012. “Looking for Theory in Preschool Education.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 31 (3): 227–238. doi:10.1007/s11217-012-9288-5.

- Syslová, Z. 2013. Profesní kompetence učitele mateřské školy [Professional Competences of a Kindergarten Teacher]. Praha: Grada.

- Temiz, Z. 2018. “Pre-service Early Childhood Education Teachers’ Perception of Their Future Profession.” Anadolu Üniversitesi Egitim Fakültesi dergisi 2 (1): 38–51.

- Thornquist, C. 2015. “Material Evidence: Definition by a Series of Artefacts in Arts Research.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 14 (2): 110–119. doi:10.1080/14702029.2015.1041713.

- Tomková, A., V. Spilková, M. Píšová, N. Mazáčová, T. Krčmářová, K. Kostková, and J. Kargerová. 2012. Rámec profesních kvalit učitele [Teacher Professional Qualities Framework]. Praha: Národní ústav pro vzdělávání.

- Torquati, J. C., H. Raikes, and C. A. Huddleston-Casas. 2007. “Teacher Education, Motivation, Compensation, Workplace Support, and Links to Quality of Center-based Child Care and Teachers’ Intention to Stay in the Early Childhood Profession.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 22 (2): 261–275. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.03.004.

- Vujičić, L., Ž. Boneta, and Ž.. Ivković. 2015. “Social Status and Professional Development of the Early Childhood and Preschool Teacher Profession: Sociological and Pedagogical Theoretical Framework.” Croatian Journal of Education 17 (1): 49–60. doi:10.15516/cje.v17i0.1540.

- Wiegerová, A., and P. Gavora. 2014. “Proč se chci stát učitelkou v mateřské škole? Pohled kvsalitativního výzkumu [Why Do I Want to Become a Kindergarten Teacher? A Qualitative Research Perspective].” Pedagogická orientace 24 (4): 510–534. doi:10.5817/PedOr2014-4-510.