ABSTRACT

This study focuses on teacher professional learning in early childhood education and care (ECEC) in response to the contemporary challenge of understanding the role of teachers in play. It explores the learning process of teachers when investigating how an ECEC work team in Sweden collaboratively changes their way of reasoning regarding their role in play when introduced to a theoretical framework that takes on this topic. This study is part of a combined research and development project, including focus group conversations (FGC) with video-stimulated recall. From a sociocultural perspective, the findings show how the participants’ reasoning is mediated and re-mediated at two levels. The first level includes the re-mediation of the concept of steering (from a more negative connotation to a more positive one). The second level explores how this shift re-mediates the team’s reasoning regarding their role in children’s play, from uncertainties regarding the risk of over steering the play to reasoning about the teacher’s key role in play for teaching to take place. Another finding focuses on the nonlinear progression of learning, as reasoning evident in the first FGC remained in the last but to a lesser extent. Implications for professional development training are discussed.

Introduction

As part of ensuring quality in early childhood education and care (ECEC), international organizations (OECD Citation2020) and the research community have shown increased interest in the professional development of early childhood (EC) teachers (e.g., Cherrington and Thornton Citation2015; Peleman et al. Citation2018). Like research on professional development and learning in school (e.g., Desimone Citation2009), much of the research literature on this topic in ECEC has focused on the effectiveness of professional development programs (e.g., Vu, Han, and Buell Citation2015). While this research has provided important findings regarding the effect of professional development programs on the quality of ECEC (e.g., Peleman et al. Citation2018), little is known about the processes by which EC teachers learn (Peleman et al. Citation2018; Sheridan, Pope Edwards, Marvin and Knoche Citation2009). In this study, learning is understood from a sociocultural perspective, highlighting the importance of concentrating on the ‘process by which higher forms are established’ (Vygotsky Citation1978, 64) rather than the product. From this perspective, learning as a process can be studied by investigating how people (e.g., teachers) change their way of reasoning about something (e.g., their role in play).

In Sweden, the issue of teacher professional learning is made visible in the Education Act (SFS, Citation2010), which states that teachers’ work should be based on scientific knowledge. This means that a part of their profession is to reflect continuously on their way of working, as well as on their views of children and knowledge. This requires the need to learn about scientific methods that provide tools for analyzing and handling challenges that occur in preschool practice. One contemporary challenge in ECEC (both internationally and in Sweden) is to understand the relationship between teaching and play – that is, how to teach learning content while at the same time promoting play (Fleer and van Oers Citation2018; Pramling and Wallerstedt Citation2019). In Sweden, this challenge became evident when the concept of teaching was added to the national curriculum for preschool (National Agency for Education Citation2018), while the curriculum simultaneously highlighted the importance of not only play but also the teacher’s role in play. The theoretical framework of Play-Responsive Early Childhood Education and Care (PRECEC) relates to this challenge by theorizing about how to create opportunities for teaching within and in response to play without turning play into non-play (Pramling et al. Citation2019; Pramling and Wallerstedt Citation2019). In the current study, the process of learning is studied by conducting focus group conversations (FGCs) with an ECEC work team, when PRECEC is introduced.

This study aims to contribute to filling the research gap in the area of teacher professional learning as a process by generating new knowledge about how EC teachers change their reasoning regarding what is arguably one of the key issues in current ECEC debates: their role in play with children (e.g., Bubikova-Moan, Næss Hjetland, and Wollscheid Citation2019). This is studied in terms of how they collaboratively reason about the issue. As an important aspect of teachers’ professional learning concerns gaining new perspectives, for example regarding their role in play, the mediating and re-mediating roles of language are used as analytical concepts in this study (these concepts will be elaborated upon in the section on the theoretical framework). The research question addressed is as follows:

How do members of an ECEC work team collaboratively change their way of reasoning regarding their role in play when introduced to a theoretical framework with principles and implications for understanding this issue?

With the focus of this study on teacher professional learning, it is important to contextualize why it is pivotal to learn more about the teacher’s role in play with children. Therefore, in the next section, previous research regarding this issue is presented and discussed.

Research on the Teacher’s Role in Play

While there is consensus regarding the importance of play for children’s learning and development (e.g., Pramling Samuelsson and Johansson Citation2006; Fleer and van Oers Citation2018), ideas concerning the teacher’s role in play, both in research and in practice, include a debate often deriving from philosophical arguments relating to the relationship between learning and play and how the teacher or the adult might interfere with the allegedly natural learning process taking place in children’s play (Cutter-Mackenzie et al. Citation2014). This especially becomes evident in research on EC teachers’ views or beliefs regarding their role in play, where views on learning as naturally occurring in play are apparent, in addition to EC teachers’ expressing uncertainties regarding when and how to participate in play with children (e.g., Bubikova-Moan, Næss Hjetland, and Wollscheid Citation2019; Walsh, McGuinnes, and Sproule Citation2019). Also, other studies on this topic have shown that EC teachers prefer to take on an observing role in relation to children’s play (e.g., Ivrendi Citation2020). In terms of observations of teachers’ engagement in play, similar results were found. For example, Fleer (Citation2015) found that most teachers in her study positioned themselves outside of children’s play, where they monitored or supervised the play. Also, Løndal and Greve (Citation2015) found that teachers’ involvement in children’s play in preschool and an after-school program was characterized by three approaches: surveillance, an initiating and inspiring approach, and a participating and interactional approach. The authors emphasize the importance of the surveillance approach, not overshadowing the other two approaches.

When it comes to whether and how EC teachers change their views on their role in play or how they change their ways of engaging in play, a few studies have approached this topic. In an early study, Wood and Bennett (Citation2000) investigated EC teachers’ reflection processes when discussing theories of play and their relationship to practice through a research-based inquiry project. The study included a multimethod approach, including stimulated recall, and the authors found that theoretical reflections and play practices changed in a three-stage process. This process took place through situated reflection, especially by watching and discussing video-recordings. While this study has elements of investigating collaborative learning (for example, some of the data included audio-recorded discussion groups), it does not have a specific focus on the mediating role of language in collaborative learning processes, which is the focus of the current study. In addition, in a more recent quantitative study, Vu, Han, and Buell (Citation2015) investigated the effect that a professional development program concerning play would have on EC teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding play. The authors found that the teachers did not change their beliefs after the training; that is, they still believed that play had benefits in relation to learning. However, the teachers did change in terms of engaging more in play with the children after the training. While this study provides interesting findings regarding the effect of professional development training on EC teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding play, it does not illustrate the processes by which teachers learn, which the current study aims to do.

The above-mentioned studies provide important findings, often in the form of categories (such as non-participatory, over-participatory, appropriately participatory in Walsh, McGuinness, and Sproule Citation2019 or leader, director, uninvolved, onlooker, and co-player in; Ivrendi Citation2020) representing different kinds of participation in play with children, both in terms of teachers’ views and in terms of observations of teachers’ engagement in play with children. The purpose of this study is not to present yet another range of categories; instead, it is to investigate how members of one ECEC work team change their way of reasoning regarding their role in play and especially how they do this jointly when introduced to a theoretical framework, PRECEC, regarding the relationship between teaching and play.

Theoretical Framework

This study is informed by a sociocultural perspective in which learning and development are understood as situated in social and cultural contexts (Vygotsky Citation1978). According to Vygotsky (Citation1978), when attempting to study learning and development, it is therefore pivotal to investigate ongoing activity. In this study, this means that, to investigate how an ECEC work team changes their way of reasoning about their role in play, the unit of analysis is the conversation between the members of the work team and the participating researcher in the FGCs. A particular focus is directed toward a dialogical understanding of language (Linell Citation2009), meaning that language, in contrast to being regarded as a system or structure, is understood as a social practice or an activity. This dialogical view of language has implications for how to study it, with a special focus on how words acquire meaning in situated interaction (Linell Citation2009). This way of approaching dialogue is made visible in the analysis of the excerpts in this study, as it sheds light on how the participants build upon and respond to each other’s utterances.

Moreover, as one must include cultural tools and social practices when studying learning and development from a sociocultural perspective, attention needs to be paid to the way participants use cultural tools; both intellectual, such as language or concepts, and physical ones (Säljö Citation2009). These cultural tools, especially language which, from a Vygotskian perspective, is regarded as the most important cultural tool – are understood as mediating our contact with the world (Wertsch Citation2007). Mediation is therefore a central concept within sociocultural perspectives, and it suggests that people are not in immediate, uninterpreted, and direct contact with the world. Instead, people use cultural tools, such as language, to make sense of the world. Here, language is regarded as a tool used by people in interaction to create meaning (Säljö Citation2014), and therefore allows for the possibility of understanding phenomena in a more nuanced and collaboratively negotiated way. When investigating the process of how the participating work team changed their way of reasoning regarding their role in play, the concepts of mediation and, especially, re-mediation have therefore been found fruitful to use for analytical purposes. Cole and Griffin (Citation1986) define re-mediation as ‘a shift in the way that mediating devices regulate coordination with the environment’ (1986, 113). An everyday example of re-mediation would be someone using Excel to create a data sheet, something that was previously done with pen and paper (Säljö Citation2013). In professional discourse, an example of re-mediation would be to go from perceiving the freedom of play as ‘free from adults’ intervention’ to children being ‘free to’ (van Oers Citation2014) take play in an unforeseeable direction. While mediation in this study can help us understand how the work team reason about their role in play, re-mediation is used to understand the shift in this reasoning through the mediating role of language. The concept of re-mediation has been used in theoretical arguments by, for example, Cole and Griffin (Citation1986) and Daniels (Citation2007) when discussing how we can learn to see things differently. However, studies where re-mediation has been used as a tool to analyze empirical data are scarce. One rare example of such a study is Nilsen et al. (Citation2021), who investigated how artifacts mediate and re-mediate analogue and digital game activities among preschool children. In the present study, re-mediation in addition to mediation will be used as analytical concepts to empirically analyze the shift in an ECEC work team’s reasoning regarding their role in play with children.

Method and Methodology

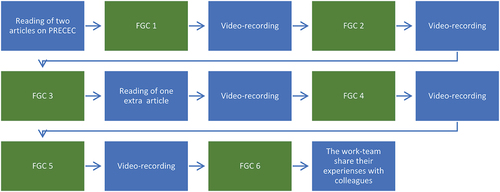

The data for this study were derived from a combined research and development project. This means that six audio-recorded FGCs with an ECEC work team and a researcher, including video-stimulated recall, were conducted over a period of eight months (see ). The participants, four teachers working with children between the ages of one and three years in a preschool in Sweden, represent a full work team. The work team was asked to participate in the study by an ECEC development manager who was part of a collaboration network between preschools and university, focusing on practice developing research with a special interest in PRECEC. The teachers were selected based on their willingness to learn more about and develop their work with play and teaching.

Meeting over an extended period was considered important to investigate learning as a process (Johnson and Mercer Citation2019). The first FGC was based on research literature on PRECEC (Pramling et al. Citation2019), while the other five were based on video-recordings of the teachers participating in play with children. The research literature consisted of two articles (Pramling and Wallerstedt Citation2019; Björklund and Palmér Citation2019) on PRECEC that the participants read before FGC 1. Later, based on the participants’ desire to learn more about meta-communication, an additional article (Lagerlöf, Wallerstedt, and Kultti Citation2019) was added after FGC 3. During the eight months, the participants also attended lectures, both online and at the University of Gothenburg, regarding PRECEC.

In this study, the ECEC work team participated in six audio-recorded FGCs with video-stimulated recall that lasted approximately one hour each, during which they discussed a predefined topic, that is the relationship between teaching and play, with a facilitator, in this case, the first author of the article. As focus group discussions, in contrast to individual interviews, make it possible to observe why participants might agree or disagree or how they build on the responses of others in addition to ‘providing a space for the generation of new ideas’ (Bourne and Winstone Citation2021, 353), it was chosen as an appropriate method as it aligns with the sociocultural perspective of the study. The FGCs were based on both the research literature and the video-recorded sequences of two of the teachers in the work team participating in play with children. Watching sequences of video-recordings in FGCs is referred to in this study as video-stimulated recall (e.g., Calderhead Citation1981). This indicates that interest lies in how the participants collaboratively reason about the stimuli that the recorded material provides. More specifically, how they reason about the relationship between teaching and play, and especially the teacher’s role in play with children. The video-recordings were conducted by the first author; however, the situations to video-record were decided along with the participants during each FGC, in line with the practice-oriented approach of the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines developed by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet Citation2017), meaning that informed consent was sought and received from both teachers and children’s caregivers. In addition, all of the participants were represented by pseudonyms in the transcribed FGCs.

Analysis

The six FGCs were transcribed verbatim in Swedish, as this was the language spoken by the participants. However, for international readers, the selected excerpts have been translated into English. In this process, careful attention was paid to context rather than literal translation to stay as close as possible to the meaning of what was said. Pauses are marked with (.) and interruptions, with // in addition to italics being used when the participants read aloud. Moreover, the empirical data of this study were structured in accordance with sociocultural discourse analysis (SCDA). SCDA is theoretically informed by a sociocultural perspective on learning and development, as it focuses on analyzing the use of language for collective thinking (Johnson and Mercer Citation2019). In this study, it means that attention has been given to Content, Time, Joint Intellectual Action and Impact. In terms of content, we carried out a careful recurring reading of the transcribed FGCs, resulting in the emergence of the theme of the teacher’s role in play. When rereading these instances, three different categories of reasoning about the teacher’s role in play became apparent. It is important to note that these categories were not characterized by a linear progression; instead, how the participants reasoned in FGC 1 remained in FGC 6, but with a shift in emphasis, as will be discussed in the findings and discussion of the article below. The categories found were as follows:

Afraid of steering the play: When the participants reason about the balance between steering the play in a certain direction and following the children’s intentions.

Coordinating the play: When the participants discuss their role in play as entailing merging participants’ different perspectives and wishes.

Expanding the play: When the participants reason about their role in play being to challenge the children.

In total, 86 sequences were found when the participants reasoned about their role in play (see ). This made it possible to analyze the sequences from the second area of SCDA, Time, that is, how a shared understanding is developed sequentially in a social context. This means that the analysis focused on how the participants changed their way of reasoning regarding their role in play during the six FGCs over a period of eight months. The third area, Joint Intellectual Action, relates to how participants acknowledge the thinking of other participants and how they use it to coordinate a shared understanding. Within this area, we paid attention to how the participants built upon and responded to each other’s utterances in accordance with a dialogical perspective on language, as well as the mediating and re-mediating role of language in the participants’ reasoning around their role in play (see Findings, below) When it comes to the fourth area, Impact, concerning ‘the effect that discourse has on the cognition and behavior of the participants’ (Johnson and Mercer Citation2019, 268), the analysis focused on how the work team applied their reasoning about their role in play to their practice.

Table 1. The number of sequences in which the participants discuss their role in play. In some sequences, elements of several categories were evident, as illustrated in the table with /. These sequences are written within parentheses in the total column.

Findings

In this section, we present a qualitative analysis of how the work team reasoned about their participation in play. Although there is no simple linear progression throughout the six FGCs in terms of the three categories outlined above (see Analysis section), there is a shift in their way of reasoning about their role in play, which in the analysis is discussed in terms of re-mediation. These shifts, which theoretically are understood as implying collective re-mediation, are illustrated through excerpts exemplifying each category.

The following excerpt takes place at the beginning of the first FGC, and the participants are reasoning about how much they might steer the children when participating in play with them. The excerpt starts with Daniela referring to a play activity which took place earlier that day, where one child was playing with a Pippi Longstocking house and figurines when another child tried to enter the play with his toy cars by pretending to drive them into the house.

Excerpt 1: Steering the play (FGC 1) 32 Daniela:And there it becomes us then. Either ‘no, now you have to use the parking garage there’ or ‘wow, has a car moved into the garage’ so how you (.) 33 Sofia: Yes yes 34 Facilitator: //what role you 35 Daniela: Yes, what role you have, yes, take there, or 36 Sofia: //Yes yes 37 Katarina: //mmm 38 Sofia: Because it was also like that with the examples 39 Facilitator: What examples? 40 Sofia: The one with the store, they had decided that they would have merchandise and then that boy came and ‘ah, thieves are coming!’ and kind of disconnected a bit (.) so 41-43 [—] 44 Sofia: And then you think ‘how would I have acted there?’ I felt that I would probably have picked up on those thieves kind of. It added a bit of an exciting spice here but her idea was to kind of play market and then the thieves does not fit in. 45 Facilitator: //yes exactly 46 Sofia: And then you also have this thought. How much do we adults really steer the children? (.) like, that is what it is about really. Where do you kind of draw the line? How much should we interfere? Is it what we think is important that steers or is it the children’s intentions with the play?In turn 32, Daniela brings up the dilemma of whether to direct the new child’s initiative toward another area (a parking garage) or to include the child’s initiative by asking, ‘Oh, has a new car moved into the garage?’ She ends by expressing concerns or wondering how she should handle the situation: ‘That is how you (.)’ but she does not finish the sentence and instead pauses, indicating that she is unsure about what role to take in this play activity. Sofia responds by agreeing with Daniela (turn 33), and the facilitator attempts to understand the uncertainty expressed by Daniela and Sofia by expressing that it relates to what role one takes (turn 34). Daniela concurs with this in turn 35 but still expresses some uncertainty when she ends her sentence with ‘or.’ In the two following turns (36 and 37), both Sofia and Katarina seem to concur with the idea that the issue concerns what role to take in a play activity. Sofia follows this in turn 38 when she refers to an example (from the provided literature). The facilitator tries to clarify what example (turn 39), and Sofia elaborates on the referred example as being one they have read about where the participants had decided to play store with merchandise, and one child tries to add the element of thieves (turn 40). This, therefore, constitutes an example of how the research literature read by the teachers’ mediates their reasoning. In turn 44, Sofia continues to explain that the example she referred to made her reflect on how she would have acted in the same situation, expressing that she most probably would have followed the direction of the thieves’ element, in contrast to what the teacher in the example decided to do. In the last turn (46), she describes how the thought of how much adults steer children has been evoked, describing it as a central issue, while also asking questions concerning this issue. These questions indicate an uncertainty about how to participate in play with children, as there is a risk of steering the play away from the children’s intentions.

Excerpt 1 illustrates the mediating role of text (see also Stavholm, Lagerlöf, and Wallerstedt Citation2021) and language as the participants build upon and respond to each other’s utterances when they refer to an example taking place in their everyday practice (play with Pippi Longstocking), followed by a discussion of an example derived from the shared research literature concerning a situation in which a teacher participated in play. In building on her reasoning regarding the example, Sofia expressed how the example evoked thoughts relating to her role in play and the risk of steering the children too much. The balance between steering the play too much and being responsive to children’s intentions in play to allow teaching to take place is a central idea in PRECEC, which indicates that the shared literature, when discussed in the FGC, mediates the participants’ reasoning regarding their role in play. While this first excerpt indicates that the participants are unsure about what role to take in play with children, especially relating to the risk of steering the play away from the children’s intentions, in the following excerpt, from FGC 4, the participants discuss their role in play in a more nuanced manner when describing it as coordinating the play, illustrating a shift or re-mediation in their reasoning. This re-mediation is thus evident in them going from an either/or position (to steer or not steer the play) to an integrative (coordinated) position.

In Excerpt 2, the participants discuss, with the help of the concept of meta-communication, how the teacher’s role is to coordinate the play. Before FGC 4, the participants had expressed an interest in learning more about meta-communication and had therefore read an additional article on this topic (Lagerlöf, Wallerstedt, and Kultti Citation2019).

Excerpt 2: Coordinating the play (FGC 4) 214 Katarina: Mm and just this it says interact on a meta-level with what is happening in the play 215 Sofia: //mm yes 216 Facilitator: //mm yes 217 Katarina: //so you sort of discuss then through them communicating about it 218 Sofia: //yes hmm 219 Katarina: //so even though you are playing you should still start comm eh sort of talking 220 Sofia://yes put it into words 221 Katarina://yes exactly 222 Daniela://mm mm 223 :.. 224 Facilitator, Katarina, Sofia: Mm yes 225 Sofia: Yes but a little bit like that clarify what’s happening, confirm what´s happening, discuss the event together and that the play continues in a mutual direction. To sort of coordinate this activity the whole time 226 Facilitator: //mm 227 Sofia: //so that everyone sort of pulls together in the same directionThe excerpt starts with Katarina reading from an article about how to interact on a meta-level when participating in play (turn 214). Sofia and the facilitator express that they are listening (turns 215 and 216), and in turn 217, Katarina tries to explain what she had just read ‘so you sort of discuss then through them communicating about it’. Sofia again confirms that she is listening but also says ‘hmm,’ indicating that she is still unsure about what it means (turn 218). Katarina continues by trying to explain that even though you play, you also have to talk, indicating a more nuanced understanding of the teacher’s role in play – to not only play but also talk (turn 219). In turn 220, Sofia confirms what Katarina is saying also elaborating when she says, ‘Yes put it into words.’ Katarina and Daniela express that they agree (turns 221–222), but then there is a pause, indicating continuing difficulties in understanding the teacher’s role in relation to the idea of meta-communicating. Sofia then confirms Katarina’s previous utterance in turn 225 and starts reading from the article about how meta-communicating means clarifying and confirming for the play to continue in a mutual direction. She continues by expressing that the teacher’s role is to coordinate the activity. However, some insecurities about the teacher’s role are still evident in the words ‘sort of’. In turn 227, she elaborates on her reasoning when she expresses that the purpose of coordinating the activity is to allow everyone to pull the activity in a mutual direction.

Excerpt 2 illustrates how the introduction of a new cultural tool, the concept of meta-communication, in combination with building upon and responding to each other’s utterances, re-mediates the participants’ reasoning regarding their role in play. It shows that although the participants still expressed some uncertainties regarding their role in play, they discussed their role in a more nuanced manner by trying to understand it in relation to communicating on a meta-level. Excerpt 3 derives from FGC 6 and is an example of how the participants have moved to express greater certainty regarding their role in play when discussing challenging the children and expanding the play.

Excerpt 3: Expanding the play (FGC 6) 428 Katarina: In the play so to say they come up with something but we may add something in order for it to develop and to keep it going for a longer time sort of, they wouldn’t be able to do that on their own 429 Facilitator: //mm 430 Sofia: //no 431 Katarina: If you were not there kind of but, then it then it becomes more that you [inaudible] someone younger there so that eh they are not there yet that they can manage it on their own sort of so that’s the difference between older and younger but that the older ones absolutely also need guidance so that eh it becomes a good play and it becomes a more eh even so that everybody has their roles sort of and that no one becomes shoved away 432 Sofia: And developing play also 433 Katarina: //yes yes 434 Sofia: I don’t think you can call it teaching if you’re not eh of course children teach children but then you have to know that children teach each other good things 435 Katarina: //yees 436 Sofia: And that a development takes place in order for it to be called teaching I think that you can’t just say that yes but they have played with dinos mm there are a lot of dinosaurs, if we had allowed them to play on their own then it would just have been this 437 Katarina: //mm 438 Sofia: like donk donk donk 439 Facilitator: //mm 440 Sofia: If it’s to be called teaching we have to add something I think in order for the play to 441 Katarina: //yees 442 Sofia: So that the play develops, then you don’t have to be part of the play all the time but I still think that eh we can’t just say that today they played this and that became teaching but yes what was the teaching in the play? What was a new sort of? What did they learn? You can only know that if you were a part of so ehIn turn 428, Katarina expresses that, although the children start the play, the teacher can add something for the play to develop and to last longer, something that the children would not be able to do by themselves, indicating that the teacher’s role in play is central for the play to develop. Sofia indicates that she agrees with Katarina’s utterance (turn 430). Katarina elaborates on her reasoning in turn 431 by pointing to the importance of the teacher being present in the play activity, especially in relation to younger children, as they would not manage to do this by themselves. Although pointing to this difference, she expressed that older children also need guidance from the teacher for the play to be ‘a good play,’ in addition to making sure that everyone in the play has a role and does not get excluded. Here, Katarina expresses more certainty regarding the importance of the teacher’s role as guiding the play, in contrast to the uncertainty expressed by the participants in Excerpt 1 regarding the balance between the teacher steering the play and following the children’s intentions, indicating a shift in her reasoning regarding her role in play. Sofia responds by adding that the play itself has to develop as well (turn 432), and Katarina agrees with this in turn 433. Sofia elaborates in turn 434 by relating the discussion to another matter when she expresses that one cannot call it teaching if the teacher is not present. She expands this reasoning by adding that children can teach children, but you (meaning the teacher) have to know that children teach each other good things. Katarina responds by agreeing (turn 435), and Sofia continues her reasoning regarding teaching and play when she expresses that development is needed for it to be called teaching, indicating that the teacher’s role is pivotal when expressing that if the children only played by themselves, the play would be limited (turn 436 and turn 438). This, again, can be argued to contrast with the uncertainties expressed in Excerpt 1 from the first FGC, hence indicating how the conversation between the participants has re-mediated Sofia’s understanding of her role in play. Sofia continues with the same line of reasoning in turn 440, when she expresses that if something is to be called teaching, the teacher has to add something. She indicates that she tries to elaborate on how this matters for the play but is interrupted by Katarina, showing that she agrees with Sofia (turn 441). Sofia then continues with her line of reasoning from turn 440 by pointing out that the teacher needs to add something for the play to develop (442). Although she argues that the teacher does not have to participate in the play all the time, she asserts that you cannot say that the children play and then there was teaching; instead, you (indicating the teacher) must ask yourself what was the teaching in the play, what was new, and what did they learn. She argued that you can only know this if you (as a teacher) participated in the play. Note that this kind of questions differs from the ones in Excerpt 1, as they pertain to the content of instruction derived from the standpoint that the teacher’s role in play is pivotal for teaching to take place. In the first excerpt, however, the questions reflected uncertainty regarding what role a teacher should take in play in order not to steer the play in a direction away from the children’s intentions. This again shows a re-mediation in Sofia’s reasoning from the first FGC and excerpt where almost a fear of steering the children too much was evident. While the concept of steering is not used explicitly in Excerpt 3, the participants indicate that they have a more positive attitude toward participating in play by steering, as the questions concerning content and instruction relate to the teacher focusing on something in the play that might not be in line with the original intentions of the children. This indicates that the concept of steering has been re-mediated, allowing for a change in reasoning about the role of the teacher in play.

Discussion

This study contributes to existing knowledge about ECEC professional development by shedding light on teachers’ learning processes. Through the analysis of how the participants build upon and respond to each other’s utterances, the findings show how the conversation between the members of the work team re-mediates their reasoning about their role in play. One finding relates to the study’s long-term perspective on learning which, in line with previous results (e.g., Peleman et al. Citation2018), indicates the importance of allowing professional development to take place over a longer period, in contrast to, for example, single workshop opportunities. This is particularly evident in relation to the second interesting finding, that is, how the participants do not move linearly from one way to a second to a third when reasoning about their role in play. Instead, although they change their way of reasoning, how they reasoned in, for example, FGC 1 persists in FGC 6, but to a lesser extent (see ). Hence, learning in this regard entails appropriating a wider repertoire of ways of mediating. A third interesting finding is that re-mediation happens at two levels. The first level relates to how the concept of steering is recharged with new meaning, that is, it is re-mediated into something more positive when the dimension of understanding and participating in response to children’s intentions, while at the same time focusing on content and instruction, is built into the concept. At the second level, this allows for the re-mediation of the teacher’s role in play in terms of moving from a fear of steering the play excessively to more certainty regarding the importance of participating in play with children if teaching is to take place. The observation that the work team members gradually show greater certainty in their reasoning implies that they appropriate this part of their professional knowledge – that is, the toolkit of their (different) role(s) in play with children. However, such increased certainty should not be mistaken for rigidity or single-mindedness since learning, from our theoretical point of view and as indicated by re-mediation, implies both appropriating a wider repertoire rather than one understanding supplanting another and nuancing initially strictly defined differences (even dichotomies), as we have already mentioned.

The findings discussed above have been made visible by focusing on studying the process of learning rather than the product. This focus contributes to previous research on professional development within the area of ECEC which has mainly focused on the outcome of professional development efforts (e.g., Vu, Han, and Buell Citation2015). To study the process of learning becomes especially important in relation to the issue of the teacher’s role in play as previous research indicates that teachers find it challenging to participate in children’s play (e.g., Bubikova-Moan, Næss Hjetland, and Wollscheid Citation2019; Walsh, McGuinnes, and Sproule Citation2019) and that ideas concerning the adult’s role in play often derive from philosophical arguments rather than empirical findings (Cutter-Mackenzie et al. Citation2014).

Conclusion

This study set out to investigate how members of an ECEC work team collaboratively changed their way of reasoning regarding their role in play with children. The findings illustrate how time and dialogue based on scientific knowledge played a central part in the teachers’ learning process. These findings have implications for professional development training in ECEC settings, as they indicate that opportunities for teachers to participate collaboratively in training with a focus on dialogue based on scientific knowledge are pivotal, in contrast to, for example, attending lectures without follow-up conversations. Another implication concerns how learning takes place in dialogue within the work team and how the constellations of work teams continually change when new teachers arrive and others leave. In relation to this, the findings point to the importance of having an overarching professional approach anchored in the organization of the preschool, rather than carried by individuals, when it comes to the professional development of work teams in preschools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Björklund, C., and H. Palmér. 2019. “I Mötet Mellan Lekens Frihet Och Undervisningens Målorientering I Förskolan [At the Intersection of the Openness of Play and the goal-orientation of Teaching in Preschool].” Forskning om undervisning och lärande 7 (1): 64–85.

- Bourne, J., and N. Winstone. 2021. “Empowering Students’ Voices: The Use of activity-oriented Focus Groups in Higher Education Research.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 44 (4): 352–365. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2020.1777964.

- Bubikova-Moan, J., H. Næss Hjetland, and S. Wollscheid. 2019. “ECE Teachers’ Views on play-based Learning: A Systematic Review.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 27 (6): 776–800. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2019.1678717.

- Calderhead, J. 1981. “Stimulated Recall: A Method for Research on Teaching.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 51 (1): 211–217. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.1981.tb02474.x.

- Cherrington, S., and K. Thornton. 2015. “The Nature of Professional Learning Communities in New Zealand Early Childhood Education: An Exploratory Study.” Professional Development in Education 41 (2): 310–328. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.986817.

- Cole, M., and P. Griffin. 1986. “A socio-historical Approach to Remediation.” In Literacy, Society and Schooling: A Reader, edited by S. De Castell, A. Luke, and K. Egan, 110–131. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A., S. Edwards, D. Moore, and W. Boyd. 2014. Young Children’s Play and Environmental Education in Early Childhood Education. Springer briefs in education. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Daniels, H. 2007. “Pedagogy.” In The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky, edited by H. Daniels, M. Cole, and J. V. Wertsch, 307–331. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Desimone, L. M. 2009. “Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures.” Educational Researcher 38 (3): 181–199. doi:10.3102/0013189X08331140.

- Fleer, M. 2015. “Pedagogical Positioning in play—teachers Being inside and outside of Children’s Imaginary Play.” Early Child Development and Care 185 (11–12): 1801–1814. doi:10.1080/03004430.2015.1028393.

- Fleer, M., and van Oers, B. 2018. International trends in research: Redressing the north-south balance in what matters for early childhood education research. In M. Fleer and B. van Oers (Eds.), International handbook on early childhood education, Volume 1 (pp. 1 -31). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Ivrendi, A. 2020. “Early Childhood Teachers’ Roles in Free Play.” Early Years 40 (3): 273–286. doi:10.1080/09575146.2017.1403416.

- Johnson, M., and N. Mercer. 2019. “Using Sociocultural Discourse Analysis to Analyze Professional Discourse.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 21: 267–277. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.04.003.

- Lagerlöf, P., C. Wallerstedt, and A. Kultti. 2019. “Barns Agency I Lekresponsiv Undervisning [Children’s Agency in Play-Responsive Teaching].” Forskning om undervisning och lärande 7 (1): 44–63.

- Linell, P. 2009. Rethinking Language, Mind, and World Dialogically: Interactional and Contextual Theories of Human sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

- Løndal, K., and A. Greve. 2015. “Didactic Approaches to Child-Managed Play: Analyses of Teacher’s Interaction Styles in Kindergartens and After-School Programmes in Norway.” International Journal of Early Childhood 47 (3): 461–479. doi:10.1007/s13158-015-0142-0.

- National Agency for Education. 2018. Curriculum for the Preschool. Stockholm: National Agency for Education.

- Nilsen, M., M. Lundin, C. Wallerstedt, and N. Pramling. 2021. “Evolving and re-mediated Activities When Preschool Children Play Analogue and Digital Memory Games.” Early Years 41 (2–3): 232–247. doi:10.1080/09575146.2018.1460803.

- OECD (2020). “Building a High-Quality Early Childhood Education and Care Workforce: Further Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018, TALIS”. Paris: OECD

- Peleman, B., A. Lazzari, I. Budginaitė, H. Siarova, H. Hauari, J. Peeters, and C. Cameron. 2018. “Continuous Professional Development and ECEC Quality: Findings from a European Systematic Literature Review.” European Journal of Education 53 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1111/ejed.12257.

- Pramling Samuelsson, I., and E. Johansson. 2006. “Play and Learning: Inseparable Dimensions in Preschool Practice.” Early Child Development and Care 176 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1080/0300443042000302654.

- Pramling, N., and C. Wallerstedt. 2019. “Lekresponsiv undervisning—ett Undervisningsbegrepp Och En Didaktik För Förskolan [Play-responsive Teaching – A Concept of Teaching and a ‘Didaktik’ for Preschool].” Forskning om undervisning och lärande 7 (1): 7–22.

- Pramling, N., C. Wallerstedt, P. Lagerlöf, C. Björklund, A. Kultti, H. Palmér, M. Magnusson, S. Thulin, A. Jonsson, and I. Pramling Samuelsson. 2019. Play-responsive Teaching in Early Childhood Education. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Säljö, R. 2009. “Learning, Theories of Learning, and Units of Analysis in Research.” Educational Psychologist 44 (3): 202–208. doi:10.1080/00461520903029030.

- Säljö, R. 2013. Lärande Och Kulturella Redskap: Om Lärprocesser Och Det Kollektiva Minnet [Learning and Cultural Tools: About Learning Processes And the Collective Memory]. 3rd. ed. Studentlitteratur.

- Säljö, R. 2014. Lärande I Praktiken - Ett Sociokulturellt Perspektiv [Learning in Practice – a Sociocultural Perspective] (3.Ed.). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- SFS. (2010:800). “The Swedish Education Act”. Stockholm: Swedish Ministry of Education and Research.

- Sheridan, S. M., C. P. Edwards, C. A. Marvin, and L. L. Knoche. 2009. “Professional Development in Early Childhood Programs: Process Issues and Research Needs.” Early Education and Development 20 (3): 377–401. doi:10.1080/10409280802582795.

- Stavholm, E., P. Lagerlöf, and C. Wallerstedt. 2021. “Appropriating the Concept of Metacommunication: An Empirical Study of the Professional Learning of an Early Childhood Education Work Team.” In Teaching and Teacher Education, 102 doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103306.

- van Oers, B. 2014. “Cultural-historical Perspectives on Play: Central Ideas.” In The Sage Handbook of Play and Learning in Early Childhood, edited by I. L. Brooker, M. Blaise, and S. Edwards, 56–66. London: Sage.

- Vetenskapsrådet. 2017. God Forskningssed. [Good Research Practice]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Vu, J., M. Han, and M. Buell. 2015. “The Effects of in-service Training on Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Children’s Play.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (4): 444–460. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2015.1087144.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, Eds. M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Walsh, G., C. McGuinness, and L. Sproule. 2019. “‘It’s Teaching … but Not as We Know It’: Using Participatory Learning Theories to Resolve the Dilemma of Teaching in play-based Practice.” Early Child Development and Care 189 (7): 1162–1173. doi:10.1080/03004430.2017.1369977.

- Wertsch, J. V. 2007. “Mediation.” In The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky, edited by H. Daniels, M. Cole, and J. V. Wertsch, 178–192. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Wood, E., and N. Bennett. 2000. “Changing Theories, Changing Practice: Exploring Early Childhood Teachers’ Professional Learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education 16 (5): 635–647. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00011-1.