ABSTRACT

Although Chinese early childhood education policies have high expectations for kindergarten teachers’ play pedagogy, teaching and play are still discussed as a bifurcation in Chinese kindergartens’ daily practice. To support Chinese kindergarten teachers’ development of play pedagogy, this study conducted an educational experiment (EE) framed by cultural-historical theory. The study was conducted in a public kindergarten located in the northeast of China. Two teachers and 34 children (4-5 years) were involved in the study. The data were collected using the methods of digital video observation, interviews, and focus group discussions. The findings indicate that EE creates a new social situation that can motivate teachers’ development in ways of collaborative teaching. Moreover, the collective reflection and Conceptual PlayWorld (CPW) implementation within the EE amplified teachers’ play pedagogy development. We argue that the EE works as a source of teachers’ professional development (PD) and builds their identity as experts in creating playful learning environments in a Chinese cultural context.

Introduction

The benefit of promoting children’s development in play is generally recognised in research. Play facilitates children’s learning in social skills (Jankowska and Omelanczuk Citation2018), academic learning (Yang, Luo, and Zeng Citation2022), moral imagination (Li, Ridgway, and Quiñones Citation2021) and so on. Moreover, play also supports teachers’ intentional teaching (Wu and Goff Citation2021). For example, a play-based setting can provide teaching opportunities in multiple subjects, such as mathematics (Disney and Li Citation2022), engineering (Lewis, Fleer, and Hammer Citation2019), or STEM generally (Stephenson et al. Citation2021). Taken together, research indicates the significance of supporting children’s academic development in play, something that is also important in the Chinese context.

Learning through play has been valued in Chinese for a long period. Since the enactment of the Working Rules for Kindergarten (Trial) (The State Education Commission of the PRC Citation1989), play has been accorded an important position in the Chinese kindergarten curriculum. With the advancement of curriculum reform, this requirement has been included in the general rules of kindergarten education (Ministry of Education Citation2001). The value of play in concept teaching has persisted in the current Chinese early years context.

Although there is a broad agreement that play provides rich prior knowledge for learning, Fleer, Fragkiadaki, and Rai (Citation2020) found in the literature that teaching and play are still discussed as a bifurcation in the daily practice in Chinese kindergartens. In line with the traditional Chinese proverb that achievement is founded on diligence and wasted upon play, play and learning are considered in opposition when it comes to children’s development (Wu and Rao Citation2011). Learning is seen as a serious activity; play is seen as an activity for leisure and entertainment. A contradiction between the policy requirement and Chinese kindergarten teachers’ value of teaching makes it difficult for teachers to implement learning experiences in play in daily practice (Qiu Citation2011). In particular, the low teacher-children ratio in Chinese kindergartens impedes the implementation of play pedagogy in Chinese kindergartens (Vong Citation2012). Although teachers are already familiar with and good at large-group instruction, more attention is directed to teaching because teachers believe that if they are not actively teaching or leading the group, learning will not occur (Hu et al. Citation2015). As a result, less attention has been paid to play. Instead, play is used by teachers to attract children’s attention or to reward for engagement in formal learning activity rather than used as a pedagogy to support learning (Qiu Citation2011). The contradiction that teachers face highlights the need for research that might help resolve this contradiction so that Chinese kindergarten teachers can meet the policy demands.

To support teachers’ development, the Professional Standards for Kindergarten Teachers – Trial version (Ministry of Education Citation2012) requires teachers to collaborate with colleagues and share teaching resources, experiences, and develop together. The requirement reflects a unique Chinese kindergarten context because Chinese kindergartens provide excellent conditions for teachers to work together and develop together. Normally three teachers work together in one kindergarten classroom, namely, the lead teacher, the teaching assistant (Mowrey and Farran Citation2021) and the carer. The ways teachers collaborate in teaching vary based on institutional demands. In most kindergartens, teachers collaborate in a ‘one teach, one assist’ approach (Hsieh and Teo Citation2021). This means, one teacher leads either the morning routine or the afternoon routine, while the other teacher facilitates the process. Both teachers need to prepare, teach, and plan the class together, which indicates the importance of effective teamwork in daily practice. The carer of the class is responsible for children’s health care and assisting with teaching if needed. This working environment provides conditions for teachers to develop together.

However, the strict hierarchy of the Chinese kindergarten administration system may hinder collaboration between teachers (Wang Citation2006). Therefore, a collaborative environment that allows for equal professional dialogue and relationships between teachers is an effective strategy to motivate collaboration among them (Zhang Citation2008). Based on this, the study aimed to provide an environment that allows equal professional dialogue between teachers. This paper presents the results regarding teachers’ development drawing on an educational experiment (EE) into learning and play in a Chinese Kindergarten. In our account of the research, we begin with a brief literature review, followed by the study design, findings, discussion and conclusion.

Literature review

The present study sits within the broad context of early childhood teachers’ professional development (PD) and focuses on teachers’ PD in the Chinese early childhood context. PD has been found to be necessary in the international early childhood setting because it benefits children’s learning and development, including providing benefits for children with special needs (Petersson Bloom Citation2021). As summarised by Brunsek et al. (Citation2020), children’s outcomes become greater when the PD program is aligned with children’s developmental goals.

Additionally, PD supports teachers’ development (Patton, Parker, and Tannehill Citation2015) in subject teaching such as maths (Llinares et al. Citation2019), science (Sakin Citation2020) and STEM (Brenneman, Lange, and Nayfeld Citation2019). Effective PD also facilitates teachers’ sustained practical changes in play (Li, Fleer, and Yang Citation2022), including the use of drama frame strategies (Kilinc et al. Citation2016) and musical play (Nieuwmeijer, Marshall, and van Oers Citation2021). These studies provide valuable research-based experience in supporting teachers’ use of play pedagogy. Despite the recognition of the significance of play pedagogy (Yang, Luo, and Zeng Citation2022), Chinese academic literature has reported little on empirical research conducted to support teachers’ play pedagogy, which justifies the need for this study.

Two important characteristics that lead to effective PD are summarised in the literature. First, ongoing support for teachers is reported as critical in effective PD (Brenneman, Lange, and Nayfeld Citation2019; Sakin Citation2020). Brenneman, Lange, and Nayfeld (Citation2019) argue that including educators in the ongoing design is one of the best practices of PD, which can promote collaboration between teachers (Nooruddin and Bhamani Citation2019). Second, external expertise supports successful PD by motivating teachers’ reflective discussion, creating conditions for their PD (González, Deal, and Skultety Citation2016), and provides feedback to support teachers’ educational practices (Brunsek et al. Citation2020). These studies add research-based evidence regarding effective PD programs in early childhood settings.

The benefits of effective PD programs in the early years represent the beginning point of implementing PD in China. However, to conduct PD in China, more needs to be known about the PD programs in the Chinese cultural context. For the past ten years, Chinese kindergarten teachers’ quality improvement has been given priority following the Outline of the National Medium- and Long-Term Programme for Education Reform and Development (Ministry of Education Citation2010). The central and local governments have actively raised funds and organised national and provincial training programs for kindergarten teachers (Zhu Citation2012b). Acknowledging the importance and value of kindergarten teachers’ PD, many researchers have turned their attention to the national and provincial training programs and propose that the professional training should: (1.) Support teachers’ content knowledge development (Guo, Cao, and He Citation2022) and (2.) Contextualise the training knowledge in the kindergarten practice (Zhu Citation2012a).

Taken together, conducting an effective PD for Chinese kindergarten teachers requires

Ongoing support from external experts, and

Supporting teachers’ content knowledge development in practice.

It is shown that researchers can provide effective PD for teachers by conducting an educational experiment (Fleer, Fragkiadaki, and Rai Citation2022), but this has received limited attention in China (Li, Fleer, and Yang Citation2022). Therefore, the study used an educational experiment (EE) to introduce a new play pedagogy into a Chinese kindergarten (Conceptual PlayWorld [Fleer 2018]) to support teachers’ play pedagogy in concept teaching. The aim of our educational experiment was to provide ongoing support for Chinese kindergarten teachers to enhance their content knowledge development. In our study, the content knowledge refers to both the discipline concept that the teachers wanted the children to learn and pedagogical content knowledge of play pedagogy. Therefore, we sought to answer the research question: How do the new conditions of an educational experiment change Chinese teachers’ concept teaching practices and their conceptualisation of play pedagogy of Chinese teachers?

Cultural-historical view of Teacher’s development

Cultural-historical theory argues that when teachers experience difficulties or contradictions, this can be seen as a positive factor to motivate individual developmental processes. In this theorisation, the challenges of Chinese context to introduce play pedagogy can be viewed as opportunities for teacher development (Sagre, Herazo, and Davin Citation2022). Given the current situation that Chinese kindergarten teachers are facing, we introduce our theorisation of teachers’ development as a foundation for the study design and findings that follow. First, we give our reason for using cultural-historical theory to understand teachers’ development. Second, we discuss a cultural-historical conception of the social situation of development to explain our analysis of the development of teachers during the educational experiment.

Vygotsky (Citation1997) illustrates how an individual’s higher mental function development begins with the social interaction between people, and then becomes internalised to serve an individual’s development. To be specific, the social situation creates conditions for development through the interaction between people. To understand development in relation to the social situation, Vygotsky (Citation1998) proposes the concept of the social situation of development, which represents the initial moment of the relation between an individual’s development and the social environment in a certain age period. This theoretical framework provides ‘fertile ground to explore teacher development as this theory focuses on the role that culture plays in human interactions’ (Eun Citation2011, 330).

Fleer (Citationin press) proposes that for adults, the institutional context might work as a source for adults’ development. Based on this, a kindergarten classroom could be an important social situation that creates potential developmental conditions for teachers’ play pedagogies. Based on this theoretical framework, the concept of the social situation of development led this study to focus on the relationship between teachers and the kindergarten context to understand Chinese kindergarten teachers’ developmental process.

An ‘individual’s development cannot be understood only through the analysis of the social situation around them, but also how individuals refract the situation’ (Bozhovich Citation2009, 60). To be specific, only social situations that are in line with an individual’s developed motives can become the individual’s social situation of development. For teachers, the social situation of development is influenced by how teachers position themselves within that social situation (Edwards, Chan, and Tan Citation2019). Therefore, this study not only examines how the social situation impacts teachers but also how teachers ‘refract’ the new social situation.

When a play pedagogy is introduced to teachers, a new activity setting (a recurrent event that a person experiences in the institutional practice (Hedegaard Citation2012)) is generated which brings new demands for teachers. In this study, a play pedagogy, Conceptual PlayWorld (CPW), developed by Fleer (2018), can be seen as the activity setting that supports teachers’ development. The contradiction between teachers’ capabilities and the new demands from the play pedagogy can be seen as a motivating force that drives the developmental process (Hedegaard Citation2019). Therefore, it was posited that the CPW as a new social situation would prompt Chinese kindergarten teachers’ development.

To capture teachers’ development in play, there are two important aspects that this study needs to pay attention to. The first one is how we define play. Drawing on a cultural-historical perspective, play is a process of creating an imaginary situation where players change the meaning of objects and actions and give them a new sense (Vygotsky Citation1966). The definition of play directed the study to pay special attention to the imaginary situation that teachers and children created. The second aspect is to clarify what we mean by development. An individual’s development is conceptualised as ‘a qualitative change in his or her motive and competencies’ (Hedegaard Citation2008a, 11). To be specific, development is not a quantitatively increased process, but a process of qualitative transformation. Taken together, this study focuses on how teachers changed their professional practice within an educational experiment.

Methodology

Drawing upon a cultural-historical understanding of development, capturing teachers’ practical changes in a natural setting is what this study mainly looked for. An educational experiment (Hedegaard Citation2008b) was used as a methodology to frame the study. An educational experiment ‘implies a cooperation between researchers and educators’ (200), aiming to solve a theoretical problem within a naturalistic setting (Hedegaard Citation2008b). To support teachers’ development in play, we introduced the CPW in the EE. The CPW is a play pedagogy that supports teachers to use imaginary play to teach scientific concepts. The CPW fits well in the Chinese kindergarten context (Fleer, Fragkiadaki, and Rai Citation2020; Ma et al. Citation2022) and suggests the possibility of teachers collectively engaging in a CPW (Lewis, Fleer, and Hammer Citation2019). Therefore, the CPW was utilised in this study as an intervention to support teachers’ development in a Chinese cultural context.

Research participants and settings

This study was conducted in a public kindergarten located in a provincial capital city of China. Two teachers, Ms Li and Ms Han, and 34 children from class C (age group 4–5, mean: 4.65 years old) participated in this study. Both participating teachers had obtained diplomas in early childhood education from a teachers’ college. With Ms Li’s 15 years of teaching experience and Ms Han’s three years of teaching experience, the two teachers had been working together in this class for four months. Pseudonyms were used in the study.

Procedure and data collection

There were three phases of the data collection using the methods of digital video observation, interviews, and focus group discussion (FGD). All three phases were documented, and a total of 58.59 hours of data were collected for the study. As we have a researcher who was overseas and could not travel to China due to the outbreak of Covid-19, video data was collected by the first author with the help of a research assistant. The overseas researcher collected data via zoom for all the interviews with children and FGDs with teachers.

The first phase included pre-implementation data collection, a PD workshop, and a teachers’ interview. Two sessions of the PD workshop were organised to introduce the CPW approach. The workshop created chances for teachers to explore, discuss, and plan the CPW. As most of the teachers in the kindergarten expressed their interest in the CPW, the workshop was organised so that all the teachers could participate. Considering the uncertainty of Covid, the PD workshop was organised once to accommodate all teachers’ schedules. Therefore, pre-implementation data collection for this study comes after the PD workshop.

The pre-implementation data aimed to capture teachers’ daily practice before the CPW was implemented. Pre-implementation data were collected from four sessions (12.75 hours in total) using digital video observation. After the pre-implementation data collection, a teachers’ interview (0.4 hours) was conducted via zoom to understand the daily activities and basic information about classroom children.

The second phase of the data collection included eight sessions of focus group discussion (FGD) and eight sessions of the CPW implementation. Each FGD session was conducted collectively by the two researchers and the two teachers before each session of the CPW, aiming to provide a platform for ongoing support and for teachers’ reflection on their practices. The CPW was conducted over two months. The two researchers and two teachers designed the CPW following the five characteristics of CPW (Fleer, Fragkiadaki, and Rai Citation2020) considering children’s interests, and perspectives.

First, select a story. A storybook named <The whale and the snail> by Julia Donaldson (Citation2003) was selected to develop a CPW, which illustrated a story about a sea snail going out for an adventure with a big whale. The book was chosen because the story is set in the ocean and aligns well with children’s interests and the classroom’s environmental theme (see ).

Second, designing the imaginary spaces. The imaginary situation was set up in an ocean aligning with the storyline.

Third, entering and exiting the PlayWorld. The teachers and children were entering or exiting the imaginary situation as characters in the story.

Fourth, planning a problem to be solved. Different problem scenarios were brought out following the storyline for children to solve with the teachers.

Fifth, determining the roles teachers would take in the CPW; the two teachers planned their interaction within the imaginary situation.

The researchers were both researchers and participants in this educational experiment. As researchers, we always kept the aim of the research in mind within the research setting. As participants, we planned and designed the activity together with the teachers and got involved in the activity to promote dramatic moments for children to solve problems. How the two researchers engaged in the study is presented in . It was challenging for the researcher in the field to capture the whole activity with one camera as a participant. Therefore, three cameras were used to video record the data, two roaming cameras were used to capture teachers and children respectively, and another still camera was used to capture the whole situation. A total of 27.63 hours of digital data were collected during the CPW implementation.

Table 1. Summary of digital video data.

The third phase was the post-interview, with children and teachers respectively, aiming to understand the CPW implementation from different perspectives. Prior to the children’s interview, researchers would clarify the interview’s purpose and obtain the children’s consent to participate. Ethical approval was granted by the authors’ university’s Human Research Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained from the participating kindergarten, teachers, and families before data collection. We explained the research purpose to teachers and parents before the consent forms were sent out. Parents were strongly encouraged to consider their children’s opinions when they signed the consent form. The summary of the research procedure and digital data is exhibited in . Data highlighted in the table represents the data used in the study, including the pre-implementation data, the implementation of the CPW, the focus group discussion and teachers’ interviews.

Data analysis

The study used three levels of interpretation (Hedegaard Citation2008c) for the data analysis to ensure the validity and stability of the data analysis. The three levels of interpretation (Hedegaard Citation2008c) include common-sense interpretation, situated practice interpretation, and thematic interpretation.

At the level of common-sense interpretation, researchers repeatedly watched the data and documented kindergarten daily practice from both teachers’ and children’s perspectives to get a holistic view of the dataset. In the situated practice interpretation, we focused on the patterns of the two teachers’ qualitative changes in their play pedagogy in the EE. At the level of thematic interpretation, the data were analysed using the theoretical concepts of the social situation of development to address the research question.

Findings

To answer the research question, this study focused on teachers’ pedagogical changes in supporting children’s concept learning in play, including the transformation of teachers’ roles, teachers’ relationships, and teachers’ collaboration in play, presented in . The study also found the change of teachers’ beliefs in play pedagogy, which will be explained via two typical vignettes of the two teachers’ pedagogy.

Table 2. The transformation happening in the educational experiment.

Vignette 1: one teach, one assist approach

This vignette was selected from the 2nd time pre-implementation data. The educational purpose of this activity was to teach the habits of fish. A story was told to promote children’s discussion about whether fish need to be taken out from the pool when winter is coming. Ms Li was the teacher who led this session and directly told children that fish cannot be taken out from the pool because fish can adjust their body temperature according to the temperature of the water (the concept of ectothermy). During the whole time, Ms Han was standing at the back of the classroom and helping Ms Li manage the children’s behaviours, as presented in .

When the teachers were asked about their collaboration in concept teaching, both teachers valued collaboration in the kindergarten context. As Ms Li said

‘Collaboration is really important. Sometimes she (Ms Han) knows what I’m about to do with eye contact. I think this is important for us to work in a kindergarten’. (C-FI-T)

In this session, the two teachers presented the ‘one teach, one assist’ approach (Hsieh and Teo Citation2021). To be specific, Ms Li was taking the leading role in the collaborative teaching relationship. Ms Han took her role as an assistant teacher in this activity so that Ms Li could focus on her concept teaching. However, as presented in Vignette 2, the way of teaching shifted as the CPW was implemented.

Vignette 2: mutual support

The vignette selected from the 2nd session of the CPW generally presents how the two teachers support children’s science learning by taking character roles in the story and how teachers change their teaching practice.

During the second focus group discussion, the researchers and teachers planned the educational aim, which was understanding the differences between the snail and the sea snail. Then, we planned the CPW collectively.

Ms Li reflected on her practice and said

At the last (CPW) session I always call sea snail as a land snail. Each time I made this mistake children would correct me. I think this is a great opportunity to explore the differences between sea snails and snails (C-2nd FGD).

The big whale (Ms Li) and little sea snails (children) came across a little snail (Ms Han) on a cliff.

Ms Li: ‘Who are you?’

Ms Han: ‘I’m a little snail’.

Ms Li: ‘What are you doing here, little snail?’

Ms Han: ‘I want to go on an adventure with you all’.

The big whale and little sea snails agreed that the little land snail could join them. However, when they dived into the water, the land snail called for help.

Ms Han: ‘Oh no! I can’t go with you anymore!’

Ms Li: ‘Why? What is happening?’

Ms Han: ‘Because I cannot breathe under the water!’

Ms Li (Big whale asking children): ‘Oh no! What should we do? Should we find a way to help her?’

The two teachers worked closely together to dramatise a scientific problem for children to solve. This way of collaborative teaching is conceptualised as the ‘mutually supportive’ approach in this study. According to the teachers, the EE motivated teachers’ practical changes in play.

Ms Li: Before the CPW, we always took the leading position even in play. Through working with you (researchers), we realised the importance of supporting children as a player and giving children chances to explore concepts. Both children and ourselves enjoyed this process. (C-FI-T)

Ms Han: ‘When we were inside the CPW, we became the play partners who contributed to the play. This makes children feel relaxed and get more involved in the activity’. (C- FGD(WeChat) -T)

Teachers’ play pedagogical changes were recognised by children. When the researchers showed to children during the interview, they said ‘We were having a class’ (C-FI-C). However, when was presented to children, they were excited and explained to the researchers about how ‘we were playing’ (C-FI-C).

‘We were having a great time in the big ocean because we were playing. I was a little sea snail, and we saw lots of animals in the deep ocean’.

Moreover, both teachers recognised the value of this new practice.

Ms Li: ‘Within the CPW, we need to collaborate and participate in imaginary play with children. This allows us to create a richer concept-learning environment for children’s learning’. (C-FGD(WeChat) -T)

The data showed how the two teachers changed their teaching practice in response to the new demand from the EE. As expected, we found in the pre-implementation data that the teachers worked in the one teach, one assist approach (Hsieh and Teo Citation2021). However, the EE created a new social situation that put demands on teachers to change their roles in practice. The collaboration between the two teachers changed. The two teachers mutually supported each other within the CPW.

Discussion

The findings suggested that the EE created developmental conditions for teachers’ qualitative pedagogical changes and motivated the development of their collaborative teaching. The focus group discussion with researchers and the CPW implementation showed how the teachers’ qualitative practices changed and developed as they worked as a dynamic team.

The collective reflection on Teachers’ play pedagogy

Providing ongoing support for teachers is one of the critical factors in conducting effective PD (Brenneman, Lange, and Nayfeld Citation2019; Sakin Citation2020). The researchers’ continual support in the focus group discussion motivated teachers to develop a new way of collectively engaging in play pedagogy. During the CPW, teachers developed a new role (the land snail), played by Ms Han, to enhance the imaginative scenario. Building on this, the researchers encouraged the teachers to use their roles to introduce science concepts to children. For instance, the land snail cannot breathe underwater like sea snails do. Therefore, a dramatic moment is created for children to explore the concept of pulmonary and gill respiration.

The ongoing support from researchers helped teachers integrate play and teaching, which overcame the bifurcation between play and teaching (Fleer and Li 2020). Teachers recognised the value of reflecting collectively with the researchers as they believe this ‘creates a richer concept-learning environment for children’. Furthermore, both teachers and children acknowledged the practical changes, from ‘always taking the leading position, even in play’ and ‘we were having a class’ towards ‘encouraging children to identify problems themselves’ and ‘We were playing’. As a result, the teachers were able to ‘create a more collaborative and effective learning environment for their students’.

In summary, the focus group discussion in EE acted as a motivating force for teachers to develop their play pedagogy. The collective reflection created conditions for researchers and teachers to build on each other’s thoughts and work together to motivate teachers’ practical change. Therefore, effective PD that supported teachers to develop together (Ministry of Education Citation2012) was provided through ongoing support from the researchers (Guo, Cao, and He Citation2022).

The collective imaginary situation motivates the change in play pedagogy

The CPW created collective imaginary situations for teachers to learn from practice (Zhu Citation2012a). Positioning themselves in imaginary roles, teachers developed a new way of collaboration in play pedagogy. They were both play partners and colleagues simultaneously and presented both real and play relationships in an imaginary situation (Kravtsov and Kravtsova Citation2010).

As players, teachers oriented themselves to different play roles so that the play could be continued (Kravtsov and Kravtsova, Citation2010). For example, the character of the big whale was full of compassion and willingness to help others. The play role motivated Ms Li to offer help and interact with Ms Han within the collective imaginary situation. The relation between the imaginary roles motivated the two teachers to develop a new way of collaboration within the collective imaginary situation. They mutually supported each other by dramatising and exploring the conceptual problem so that children were engaged and took initiative in concept learning. Meanwhile, they were also colleagues holding the teaching agenda to support children’s scientific learning. The double relationship between teachers in play provides possibilities for teachers to transit between their relationships in play to support children’s learning (Fleer Citation2019). When teachers collaborate as players, they not only have an equal position with the children but also have an equal position with each other. This equality helps to reduce the strict hierarchy of the administration system, which is believed to impede teacher collaboration in Chinese kindergartens (Wang Citation2006). In conclusion, the collective imaginary situation within a CPW gave teachers the possibility to develop a new way of collaborating to support children’s concept learning.

The educational experiment creates developmental conditions for teachers

The EE created a new social situation and placed demands on teachers to change their motives when supporting children’s scientific learning. They moved from a didactic approach to use play roles to support concept learning. A very different developmental condition for children’s development was created when adults engaged in play (Fleer Citation2019).

The qualitative change in teachers’ motives indicated the development of their play pedagogy (Hedegaard Citation2008a). To be specific, the focus group discussions motivated teachers to engage in reflective discussion and the CPW brought out teachers’ PD in relation to the practice and facilitated the pedagogical changes of teachers. Teachers’ collaboration was reinforced by the EE, which aligned with their developmental motives as they mentioned that they value collaboration in the kindergarten context. The teachers’ collaborative teaching development was realised as they positioned themselves as collaborators in play while supporting children’s science learning.

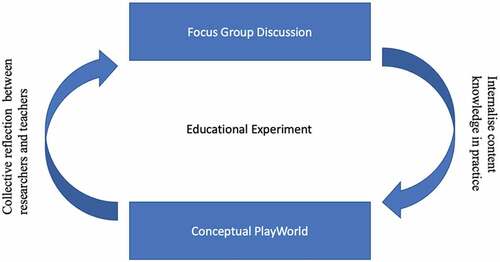

The cultural-historical theory argues that an individual’s development starts from the social interaction between people, and then becomes internalised to serve the individual’s development (Vygotsky Citation1997). In this study, teacher development started from the interaction between researchers and teachers, then was internalised into their teaching practice. The focus group discussion and CPW supported the teachers’ development in a dynamic way in the educational experiment, as presented in .

Conclusion

The expectation from Chinese early years policies has placed demands on kindergarten teachers to develop their play pedagogy (Ministry of Education Citation2001, Citation2012). However, this is challenging work for Chinese kindergarten teachers (Qiu Citation2011; Wu and Rao Citation2011). Drawing upon cultural-historical theory, this study regards the challenge as a developmental opportunity for teachers (Vygotsky 2019) and conducted an EE to support teachers’ play pedagogy.

The findings respond to the literature arguing that the EE works as a source for teachers’ PD through collective reflection and practice (Li, Fleer, and Yang Citation2022). Taking this one step further, this study suggests that EE creates a collective learning environment for teachers to develop play pedagogy together, responding to a significant policy requirement (Ministry of Education Citation2012).

The study is limited because the conclusion is based on two teachers from one Chinese kindergarten. However, the EE is a possible way of supporting Chinese kindergarten teachers’ play pedagogy development in the Chinese kindergarten context. Further study is needed to investigate if EE can support more teachers’ PD in concept teaching in play.

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to the kindergarten where this study was conducted, the participants, as well as Xin Shan for supporting the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bozhovich, L. I. 2009. “The Social Situation of Child Development.” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 47 (4): 59–86. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470403.

- Brenneman, K., A. Lange, and I. Nayfeld. 2019. “Integrating STEM into Preschool Education; Designing a Professional Development Model in Diverse Settings.” Early Childhood Education Journal 47 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1007/s10643-018-0912-z.

- Brunsek, A., M. Perlman, E. McMullen, O. Falenchuk, B. Fletcher, G. Nocita, N. Kamkar, and P. P. S. Shah. 2020. “A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Associations Between Professional Development of Early Childhood Educators and Children’s Outcomes.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 53: 217–248. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.03.003.

- Disney, L., and L. Li. 2022. “Above, Below, or Equal? Exploring Teachers’ Pedagogical Positioning in a Playworld Context to Teach Mathematical Concepts to Preschool Children.” Teaching and Teacher Education 114: 103706. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103706.

- Donaldson, J. 2003. The Snail and the Whale. London: Macmillan.

- Edwards, A., J. Chan, and D. Tan. 2019. “Motive Orientation and the Exercise of Agency: Responding to Recurrent Demands in Practices.” In Cultural-Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development: Societal, Institutional and Personal Perspectives, edited by A. Edwards, M. Fleer, and L. Bøttcher, 201–214. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Eun, B. 2011. “A Vygotskian Theory‐based Professional Development: Implications for Culturally Diverse Classrooms.” Professional Development in Education 37 (3): 319–333. doi:10.1080/19415257.2010.527761.

- Fleer, M. 2019. “Children and Teachers Transitioning in Playworlds: The Contradictions Between Real Relations and Play Relations as a Source of Children’s Development.” In Children’s Transitions in Everyday Life and Institutions, edited by M. Hedegaard and M. Fleer, 185–206. Bloomsbury: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Fleer, M. in press. “A Cultural-Historical Study of Teacher Development: How Early Childhood Teachers Meet the Demands of a Theoretical Problem for Practice Change.” In Sociocultural Approaches to STEM Education: An ISCAR International Collective Issue, edited by P. Katerina and B. Sylvie, 3–32. NYC: Springer Series Cultural Studies of Science Education.

- Fleer, M., G. Fragkiadaki, and P. Rai. 2020. “Programmatic Research in the Conceptual PlayLab: STEM PlayWorld as an Educational Experiment and as a Source of Development.” Science Education and Research Practice 76: 9–23.

- Fleer, M., G. Fragkiadaki, and P. Rai. 2022. “The Place of Theoretical Thinking in Professional Development: Bringing Science Concepts into Play Practice.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 32: 100591. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2021.100591.

- González, G., J. T. Deal, and L. Skultety. 2016. “Facilitating Teacher Learning When Using Different Representations of Practice.” Journal of Teacher Education 67 (5): 447–466. doi:10.1177/0022487116669573.

- Guo, L., J. Cao, and T. He. 2022. “基于学习路径的教师培训: 幼儿园教师专业发展新思路.” 学前教育研究 [Research in Early Childhood Education] 7: 1–11. doi:10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2022.07.002.

- Hedegaard, M. 2008a. “A Cultural-Historical Theory of Children’s Development.” In Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by M. Hedegaard and M. Fleer, 10–29. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Hedegaard, M. 2008b. “The Educational Experiment.” In Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by M. Hedegaard, M. Fleer, J. Bang, and P. Hviid, 181–201. Maidenhead, England; New York: Open University Press.

- Hedegaard, M. 2008c. “Principles for Interpreting Research Protocols.” In Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach, edited by M. Hedegaard, M. Fleer, J. Bang, and P. Hviid, 46–64. Maidenhead, England, New York: Open University Press.

- Hedegaard, M. 2012. “Analyzing Children’s Learning and Development in Everyday Settings from a Cultural-Historical Wholeness Approach.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 19 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1080/10749039.2012.665560.

- Hedegaard, M. 2019. “Children’s Perspectives and Institutional Practices as Keys in a Wholeness Approach to Children’s Social Situations of Development.” In Cultural-Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development: Societal, Institutional and Personal Perspectives, edited by A. Edwards, M. Fleer, and L. Bøttcher, 23–41, Singapore: Springer.

- Hsieh, M. F., and T. Teo. 2021. “Examining Early Childhood Teachers’ Perspectives of Collaborative Teaching with English Language Teachers.” English Teaching & Learning 1–20. doi:10.1007/s42321-021-00102-5.

- Hu, B., X. Fan, S. S. L. Ieong, and K. Li. 2015. “Why is Group Teaching so Important to Chinese Children’s Development?” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 40 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1177/183693911504000102.

- Jankowska, D. M., and I. Omelanczuk. 2018. “Potential Mechanisms Underlying the Impact of Imaginative Play on Socio-Emotional Development in Childhood.” Creativity 5 (1): 84–103. doi:10.1515/ctra-2018-0006.

- Kilinc, S., M. F. Kelley, J. Millinger, and K. Adams. 2016. “Early Years Educators at Play: A Research-Based Early Childhood Professional Development Program.” Childhood Education 92 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1080/00094056.2016.1134242.

- Kravtsov, G. G., and E. E. Kravtsova. 2010. “Play in L. S. Vygotsky's Nonclassical Psychology.” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 48 (4). doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405480403.

- Lewis, R., M. Fleer, and M. Hammer. 2019. “Intentional Teaching: Can Early-Childhood Educators Create the Conditions for Children’s Conceptual Development When Following a Child-Centred Programme?” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 44 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1177/1836939119841470.

- Li, L., M. Fleer, and N. Yang. 2022. “Studying Teacher Professional Development: How a Chinese Kindergarten Teacher Brings Play Practices into the Program.” Early Years 42 (1): 104–118. doi:10.1080/09575146.2021.2000942.

- Li, L., A. Ridgway, and G. Quiñones. 2021. “Moral Imagination: Creating Affective Values Through Toddlers’ Joint Play.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 30: 100435. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100435.

- Llinares, S., O. Chapman, P. Preciado-Babb, M. Metz, B. Davis, and S. Sabbaghan, eds. 2019. Transcending Contemporary Obsessions: The Development of aModel for Teacher Professional Development. In International Handbook of Mathematics Teacher Education: Volume 2: Tools and Processes in Mathematics Teacher Education (Second Edition), 361–391. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Ma, Y., Y. Wang, M. Fleer, and L. Li. 2022. “Promoting Chinese Children’s Agency in Science Learning: Conceptual PlayWorld as a New Play Practice.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 33: 100614. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100614.

- Ministry of Education. 2001. 幼儿园教育指导纲要(试行) [Guidelines for Kindergarten Education Practice—Trial Version]. Edited by Ministry of Education. Beijing.

- Ministry of Education. 2010. National Outline for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development (2010–2020). Beijing: MOE.

- Ministry of Education. 2012. 幼儿园教师专业标准(试行)[professional Standards for Preschool Teachers—Trial Version]. Edited by Ministry of Education. Beijing.

- Mowrey, S. C., and D. C. Farran. 2021. “Teaching Teams: The Roles of Lead Teachers, Teaching Assistants, and Curriculum Demand in Pre-Kindergarten Instruction.” Early Childhood Education Journal 50 (8): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01261-7.

- Nieuwmeijer, C., N. Marshall, and B. van Oers. 2021. “Musical Play in the Early Years: The Impact of a Professional Development Programme on Teacher Efficacy of Early Years Generalist Teachers.” Research Papers in Education 1–22. doi:10.1080/02671522.2021.1998207.

- Nooruddin, S., and S. Bhamani. 2019. “Engagement of School Leadership in Teachers’ Continuous Professional Development: A Case Study.” Journal of Education and Educational Development 6 (1): 95–110. doi:10.22555/joeed.v6i1.1549.

- Patton, K., M. Parker, and D. Tannehill. 2015. “Helping Teachers Help Themselves: Professional Development That Makes a Difference.” NASSP Bulletin 99 (1): 26–42. doi:10.1177/0192636515576040.

- Petersson Bloom, L. 2021. “Professional Development for Enhancing Autism Spectrum Disorder Awareness in Preschool Professionals.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 51 (3): 950–960. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04562-9.

- Qiu, X. 2011. “关于幼儿园游戏指导存在问题的思考 [Thinking About the Problems Existing in Kindergarten Game Guidance.” 早期教育(教师版) [Early Education (Teacher Edition)] 12: 4–6.

- Sagre, A., H. D. Herazo, and K. J. Davin. 2022. “Contradictions in Teachers’ Classroom Dynamic Assessment Implementation: An Activity System Analysis.” TESOL Quarterly 56 (1): 154–177. doi:10.1002/tesq.3046.

- Sakin, A. 2020. “Preschool Pre-Service Teachers’ Scientific Attitudes for Sustainable Professional Development.” International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction 12: 16–33.

- The State Education Commission of the PRC. 1989. “幼儿园工作规程(试行)[working Rules for Kindergarten (Trial)].” edited by 国家教育委员会 [State Education Commission of the PRC].

- Stephenson, T., M. Fleer, G. Fragkiadaki, and P. Rai. 2021. “Teaching STEM Through Play: Conditions Created by the Conceptual PlayWorld Model for Early Childhood Teachers.” Early Years 1–17. doi:10.1080/09575146.2021.2019198.

- Vong, K. 2012. “Play – a Multi-Modal Manifestation in Kindergarten Education in China.” Early Years 32 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1080/09575146.2011.635339.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1966. “Play and Its Role in the Mental Development of the Child.” Voprosy psikhologii 12 (6): 62–76. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-040505036.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1997. “The Collected Works of L.S. Vygotsky Vol 4. In: The History of the Development of Higher Mental Functions. Translated and edited by R. W. Rieber and M. J. Hill. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1998. “The Collected Works of L.S. Vygotsky Vol 5.“ In Child Psychology. Translated and edited by R. W. Rieber and Hill M. J. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Wang, F. 2006. “论阻碍幼儿教师有效合作的潜在因素及其消除 [On the Potential Factors Hindering the Effective Collaboration of Preschool Teachers and Their Elimination.” 学前教育研究 [Research on Early Childhood Education] 12: 48–50.

- Wu, B., and W. Goff. 2021. “Learning Intentions: A Missing Link to Intentional Teaching? Towards an Integrated Pedagogical Framework.” Early Years 1–15. doi:10.1080/09575146.2021.1965099.

- Wu, S., and N. Rao. 2011. “Chinese and German Teachers’ Conceptions of Play and Learning and Children’s Play Behaviour.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 19 (4): 469–481. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2011.623511.

- Yang, W., H. Luo, and Y. Zeng. 2022. “A Video-Based Approach to Investigating Intentional Teaching of Mathematics in Chinese Kindergartens.” Teaching and Teacher Education 114: 103716. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103716.

- Zhang, P. 2008. “幼儿园教师合作的内隐研究[a Study on Pre-School Teacher’s Implicit View on Teacher’s Collaboration].” Southwest University.

- Zhu, J. 2012a. “对幼儿园教师培训问题的再思考[rethinking the Training of Kindergarten Teachers].” 幼儿教育 [Early Childhood Education] 10: 4–5.

- Zhu, J. 2012b. “对幼儿园教师培训问题的思考[thinking the Training of Kindergarten Teachers].” 幼儿教育 [Early Childhood Education] Z1: 18–19.