ABSTRACT

In western mental health systems, the involvement of user organisations has become an important dimension of contemporary policy development. But the processes constituting users as a relevant/irrelevant group have received little investigation, especially outside the English-speaking world. Drawing on Luhmann’s theory of society, this article presents a reconstruction of involvement initiatives in mental health policy in Chile between 1990 and 2005. It is based on 17 oral history interviews with policy-makers, high-level professionals, involved users, ex-users, and family activists, drawing also on relevant policy documents. Five processes are identified. In the early 1990s, the relevance of family groups as care providers in the context of deinstitutionalisation shaped the first encounters between psychiatry and community. Later, user groups became relevant as political supporters of the Mental Health Department’s funding requests, and in their capacity to legitimise decisions on involuntary treatment. The first National User Organisation resulted, in 2001. Its relevance was quickly undermined, however, by the AUGE health reform which restricted the definition of diseases and treatments with reference to evidence and costs. The legitimation of users was no longer needed and efforts to involve them subsided. Thus, we argue that the way in which the mental health system observes the voices of users is less a result of the actual status of users’ organisations than of the changing needs of mental health policy for ‘user representation’. By highlighting the contingency of policy shifts, we suggest that this historical and systemic perspective provides grounds for the strategic irritation and transformation of mental health systems through users’ activism.

Chilean Mental Health Policy and the role of users

For most of Chile’s history, the asylum constituted the dominant institutional response to those deemed ‘mad’. The creation of the National Health Service in 1952 increased the reach of services, but psychiatry was still understood as a legal/penal field (Minoletti, Rojas, & Sepúlveda, Citation2010). From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, coinciding with a strong condemnation of the living conditions of psychiatric inmates, alternative approaches were explored throughout Latin America, following Franco Basaglia’s deinstitutionalisation process in Trieste and the ‘Movement of Community Psychiatry’ in the USA (Maass, Mella, & Risco, Citation2010; Scheper-Hughes & Lovell, Citation1986).

The military coup of 1973 and the ensuing 30 years of dictatorship destroyed the incipient community-based experimentation and the psychiatric hospital regained its monopoly. Meanwhile, radical neoliberal reforms divided the health system into a small private sector and a poor and overcrowded public sector (Missoni & Solimano, Citation2010). By the end of the dictatorship, four mental hospitals consumed most of the mental health budget. People were locked in overcrowded institutions, without opportunities for rehabilitation or social inclusion, and subjected to human rights violations (Minoletti et al., Citation2010). The return of democratic institutions ignited a series of reforms guided by the ‘Conference for the Restructuring of Psychiatric Care in Latin America’ and its ‘Caracas Declaration’, signed by most countries in the region in 1990. Subsequently, a long overdue process of deinstitutionalisation and decentralisation began (Caldas de Almeida, Citation2005).

Two distinct policy paths followed the Declaration. Countries, such as Brazil and Argentina promoted deep reforms and experimentation at the local level, while Chile, Cuba and others prioritised the integration of mental health into primary health (Maass et al., Citation2010). In Chile, this was reflected in the first National Mental Health Plan of 1993. Despite these efforts, by the end of the 1990s deinstitutionalisation had stagnated (Minoletti, Sepúlveda, & Horvitz-Lennon, Citation2012).

In this context, the new Mental Health Department (MHD) within the Ministry of Health aligned new sources of support for its Second National Mental Health Plan. A network of civil society actors developed, including human rights lawyers and advocates, NGOs, mental health professionals and family organisations, culminating in the establishment in 1999 of CORFAUSAM, the National Coordinator of Organisations of Families, Users and Friends of Persons with Mental Disorders. Users within CORFAUSAM developed the idea of a user-led advocacy organisation with national representation. The National Association of Mental Health Service Users (ANUSSAM) was created in 2001.

In 2000, the Second National Mental Health Plan was published, consolidating the first plan’s main goals, increasing the budget for mental health, relocating services from psychiatric wards to decentralised units and improving the macro-organisation of the system as a whole (Minoletti & Zaccaria, Citation2005). In 2005, the AUGE reform was signed, which aimed to expand health coverage by prioritising a delimited set of health problems, and defining the authorised treatments, waiting times and statutory rights of patients (Dannreuther & Gideon, Citation2008). Among 69 diseases, three mental health diagnoses were included: Schizophrenia, Depression, and Problematic Substance Abuse. This was to have a specific impact on the interaction between ANUSSAM and the MHD.

Unlike Argentina or Brazil, whose advances in mental health policy have privileged subregional experimentation and differentiation (Alarcón & Aguilar-Gaxiola, Citation2000), Chile has followed WHO’s technical recommendations carefully before and after the Caracas Declaration. Its gradual deinstitutionalisation process and the sustained scaling-up of services have been promoted as a model for other countries (Araya, Alvarado, & Minoletti, Citation2009). Nonetheless, and although ANUSSAM has been functioning since 2001, the latest version of the WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (AIMS) concludes that, in Chile, ‘a low presence and a poor level of organisation of the mental health users and family members associations is still observed’ (World Health Organization, & Ministerio de Salud, Citation2014, p. 11).

This article uses oral histories to examine the processes that preceded, influenced and accompanied the creation of ANUSSAM in order to historicise the visibility of users, and understand how the Chilean mental health field has produced the conditions for this observation of a ‘poor’ state of user organisations.

User organisations and the mental health system

The collective agency of users and their ability to influence policy has been differently conceptualised and justified in the psy-sciences, the social sciences and by users/survivors themselves. Speaking from a user perspective and in the UK context, Campbell (Citation1996) identifies two major processes explaining the emergence of self-advocacy by mental health users. First, deinstitutionalisation allowed a minimum degree of freedom to engage in conversation with peers outside the hospital, discussing experiences and developing self-help practices. Influenced by the civil rights movement, these groups embraced self-determination and political activism (Cook & Jonikas, Citation2002). Ownership of mental health services became distributed away from psychiatry, creating new opportunities, with new stakeholders, for users to be heard (Castel, Castel, & Lovell, Citation1982).

Second, the consumerist turn shaping the health sector in England and other countries through the 1980s and 1990s (Milewa, Valentine, & Calnan, Citation1999) forced services to hear what users had to say (Campbell, Citation1996). This turn afforded opportunities for users to be regarded as a group with consistent and challenging views, although it was not a deep democratisation of the mental health field (Tovey, Atkin, & Milewa, Citation2001). Pilgrim claims that while ‘the voice of users has been asserted, the voice of consumerism has been elicited’ (Citation2005). He identifies the active role of the mental health system in framing and, fundamentally, controlling the nature, scope and results of the engagement of users. This process has been described as ‘incorporation’ (Forbes & Sashidharan, Citation1997) and ‘co-option’ (Pilgrim, Citation2005). As Tomes notes, ‘In the mental health field […] consumers’ interests tend to be the least well organised and most underfunded. Their input has been welcomed and acted on only to the extent that it serves the purposes of other, better-organised stakeholders’ (Tomes, Citation2006, p. 725).

While this line of analysis validly emphasises the power imbalances limiting the nature and outcomes of participation, it tends to overemphasise the domination of institutions and their rationality. Other authors have sought to unpack concrete instances of involvement in their contingent policy scenarios. El Enany, Currie and Lockett analyse the mechanisms by which the mental health system has adapted itself to ‘involvement’, safeguarding its own boundaries ‘through a combination of self-selection by those wanting to be involved, and professionals actively selecting, educating and socialising certain users’ (Citation2013, p. 24). Martin (Citation2008) considers representativeness as a negotiated outcome of concrete attempts at engagement, situated in specific policy contexts, beyond the abstract ‘interests’ each side represents. This literature points to how patterns of selection and representation cut across the boundaries of institutions and user groups, complicating a stable model of positions and interests (Hutta, Citation2010). We follow this analytical line to examine how users, their goals and organisational potential have been framed in policy, and how this framing is rooted in the transformations of the mental health system over time.

To do so, we draw on Niklas Luhmann’s theory of society and particularly his twin notions of observation and distinction (Luhmann, Citation1995, 2012). Following this approach social entities and processes are the results of forms or ‘distinctions’ used to observe them. In modern society different subfields (economics, politics, art, etc.) gain increased functional differentiation and the ability to observe other social systems and society as a whole through distinctions adapted to their own self-reproducing requirements (Luhmann, Citation1995). In the context of our discussion this means that the organised agency of users is filtered by the mental health system through selective patterns of attention or relevance. Observation is an operation occurring in the system (Luhmann, Citation2012), meaning, here, that those patterns are rooted in the mental health system’s own complexity and its contingent and dynamic relations with other systems (legal, economic, etc.). The observations made by the mental health system serve to maintain and reproduce that system.

While abstract, this conceptualisation closely matches the notions of selectivity and legitimation already present in empirical analyses of participatory practices in mental health systems (El Enany et al., Citation2013; Harrison & Mort, Citation1998). Selectivity becomes one expression of how systems make observations on the basis of distinctions, in a recursive, self-referential way. Present distinctions are based on prior distinctions and form the basis for further distinctions upon which observation become possible.

In this article, the relation between users’ organisations and the mental health system is conceived as a temporal process of selectivity and observation embedded in broader institutional transformations. The analysis is focused on those contingent policy scenarios that shifted the relevance of user organisations and their input. This is done in order to understand how certain policy processes, within and outside the mental health field, have configured a particular relation between the mental health system and users’ organising efforts, affecting the distinctions through which those efforts are observed.

Methods

There exists no written history of users’ self-advocacy in Chile. Users are absent from the available historical treatments of psychiatry and mental health policy (Marconi, Citation1999; Minoletti et al., Citation2010). In this article, we follow the principles of oral history, pragmatically formulated as ‘the interviewing of eye-witness participants in the events of the past for the purposes of historical reconstruction’ (Grele, Citation1996, p;.63). According to Perks & Thomson, a distinctive contribution of oral history is to include ‘the perspectives of groups of people who might otherwise have been hidden from history’ (Citation1998, p. ix). Mental health service users are one such group.

Selection

Seventeen interviews were conducted between July and December 2015, with actors centrally involved in the creation of ANUSSAM in 2001. A snowball sample was initiated by approaching five participants known to the first author, across policy and user-led initiatives. Nine authorities and professionals working and/or directly collaborating with the Mental Health Division during the 1990s and early 2000s were selected on the basis of their close relation with the creation of ANUSSAM.

Users were harder to reach, revealing an asymmetry between visibility of their accounts and those of policy agents. Activist users have fluctuating trajectories, with periods of heightened activity followed by relative absence due to changes in their lives. The two main originators and ongoing leaders of ANUSSAM were interviewed as were three users and three family activists involved in advocacy at that time. All interviewees continue to be active in the mental health field, within academia, policy or advocacy, so their perspectives are inevitably grounded in the contemporary challenges of the field.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted in Spanish, and audio-recorded. They lasted between 45 and 120 minutes. Current policy-makers were interviewed in their own work environments. Former policy-makers held academic positions and were interviewed in universities. Family activists were spread across public health institutions and NGOs. Since ANUSSAM has no formal space or office, activists were interviewed in their houses, workplaces, or public places such as coffee shops.

Interviews followed each participant’s early involvement in the field, their views on user involvement during the 1990s and 2000s, the creation of ANUSSAM and the context of its emergence, its development as an organisation and its interaction with the mental health system. The interviews also covered participants’ views on the current challenges faced by user organisations, and by the mental health system as a whole.

Context-setting documents

To trace policy processes, 56 documents were selected from the MHD and the Library of the Ministry of Health. They include National Plans, Local Mental Health Plans, Clinical Guidelines and Protocols, Evaluation reports and Legal Documents. They were used to verify facts and milestones reported in the interviews. ANUSSAM provided all of their written information, 26 documents, including funding proposals, reports of activities, and administrative and legal documents related to their legal consolidation.

Ethics

The research process was conducted in full accordance with the LSE’s Research Ethics Policy and Procedure, and formal ethical approval was granted. Since users were approached through their own organisation, not by virtue of their engagement with health services, ethical approval from a health service IRB was not required.

Interviewees took part under conditions of voluntary informed consent. The nature and aims of the research project were clearly explained both over email and in person. Participants were given the option of having their interview anonymised. For the sake of consistency and to reduce possibilities of identification, pseudonyms are used in this paper.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was applied by the first author to the interview transcripts, with a coding framework combining deductive and inductive themes. The analysis focused on how users, their roles in policy, and the notion of user involvement were understood across different points in time. At this stage, themes describing the nature of user involvement, such as ‘early organising practices’, ‘notions of advocacy’ and ‘representativeness’ were identified. Relations between the themes, their changes over time, and their relations to contextual elements were explored in order to produce a historicised understanding. Written sources helped to cross-check and contextualise emerging interpretations.

The understandings of user involvement that emerged in the thematic analysis were not uniform across time. A second stage of analysis clustered the meanings of user involvement that were dominant at different points. Drawing on Luhmann’s (Citation2012) formulation of sociology as the observation of how things are observed (or second order observation), this stage distinguished a series of five interlocking institutional processes in which users’ agency was observed differently by policy at different stages. The presentation of the analysis follows the temporality of the oral histories, both enriching and departing from the official account of events and milestones usually presented in policy discourses on mental health policy modernisation, across the period from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s.

Findings

Processes and events look notably consistent across the descriptions of current and former policy-makers, resembling a logical unfolding of scenarios and decisions. Regardless of the variations in how events are described or valued, a consistent distinction between past, present and future organises their narrative description, matching the accounts in policy documents and statements. Even the doubts and self-criticism apparent in the interviews were always accommodated within narratives of progress. However, as we explore below, the position of user organisations vis-à-vis the modernisation of the system reveals the contingency of that history and the shadows of this progress.

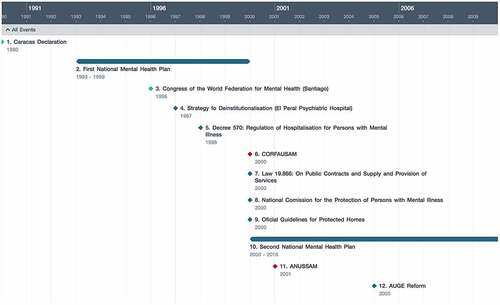

Hence, the findings are not presented as a single temporal narrative, wherein the moment of emergence of user organisations can be pinpointed. Instead, five overlapping and interdependent processes are sketched, revealing an eventful, open-ended, and contingent temporality. These processes directly framed the meaning of users’ self-advocacy and its organisational emergence. A single timeline of macro-events is presented first (), to guide the reader through the events, reforms and policies that marked this period.

First process: The Second Mental Health Plan and the need for expanded political support

In the overarching horizon of deinstitutionalisation that defined the long-term policy agenda in Chile during the 1990s, the relevance and role of family caregivers and their organisations changed fundamentally. Families became a valuable sanitary resource, at first individually, as care-providers to their family members, then collectively, as managers of protected homes in the community, and eventually politically, demanding more resources for mental health in the community. Family organisations thus gained a new status as agents in the mental health system.

According to the authorities interviewed, at the end of the 1990s, it became increasingly clear that stronger political support was required to increase the national budget for mental health and make the changes devised in the Caracas Declaration. Deinstitutionalisation was stagnated, community-based alternatives were underdeveloped and funding amounted to 1.5% of the health budget, a 0.5% increase since 1990. The main challenge was to increase the relevance of mental health in relation to other priorities. This was the goal of the Second Mental Health Plan.

In this context, starting in 1997, family organisations became framed as an advocacy resource. Slowly, within them, users started to gain some space. Javiera Reyes, the executive secretary for the plan’s creation, explains the rationale for involving families and users.

We wanted them to understand the need for their participation in advocacy, their incorporation, we wanted them to give force to this national plan so it could become true. I mean, together, to push harder so this could come true. You have to understand that at that time we were asking for some major funding for mental health. So it was important to become partners with these organisations, recognising their contribution based on their experience. [Our emphasis]

But for authorities, who were supposed to be co-ordinating a national process of developing the mental health plan, selectivity became a problem, as it was unclear which user or family organisations they should engage with, which ones would add legitimacy to the plan. According to Nicolás Galiani, a key figure in the modernisation of the system who worked in the MHD during the 90s and 2000s, at that point

(…) there were some organisations working inside or alongside hospitals, psychiatric hospitals. They were working since the 80s, there was a degree of local organisation, but I don’t think they had a national organisation, I think they didn’t, I think that only when our team [the MHD] started to invite carers and small groups to these national events, only after that they became nationally organised, they developed a national representation [CORFAUSAM]. [Our emphasis]

Retrospectively Nicolás Galiani observes that the representation of families at a national level was the result of an institutional effort to reach their voices and harness their support. In contrast, for Samuel Robles, original leader of the family organisation CORFAUSAM, the idea of creating a national body representing the voices and concerns of families resulted from a process of empowerment. Influenced by international experiences, different family groups sharing common concerns came together and decide to act together in relation to the authorities. While their descriptions map a process of organisational adaptation between the MHD and family groups, each side highlights its own agency in the ensuing process.

Second process: The Mental Health Department and the representativeness of CORFAUSAM

At the beginning of the 1990s, the role of family groups was framed as aiding deinstitutionalisation. Users were treated as passive, waiting to be relocated from ‘institution’ to ‘community’. Gradually, between 1993 and 1996, more family organisations started to emerge. These organisations shared a demand for more and better support that resonated with the MHD’s ambitions in terms of funding and scaling up. Fernando Flores, former head of the MHD during that period, describes the excitement – and subsequent disappointment – that surrounded this process.

There’s no doubt that there was an explosive development of organisations between ‘93, ‘94, ‘95. In those years, we went from two to three organisations, completely dominated by doctors, organising Christmas activities and that sort of thing, to having 50 or more organisations, each with a proper legal personality. This was a boom. Over time, all these small organisations created a macro-organisation, CORFAUSAM, that originally was much more powerful than today. In a way this super-organisation both helped and restricted, because it created a structure, reducing the spontaneity, producing a specific dialogue that generated conflicts with the rest of the organisations.

CORFAUSAM was born in 1999 to unify the advocacy efforts of smaller local organisations. It had ‘national representation’, but it was quickly accused of being unrepresentative. Lidia Hernández, a nurse who had worked in the mental health division since 2003, links the operation of the MHD with these problems.

(…) maybe it was the lack of funding, the lack of a different structure, I don’t know, but we had a much stronger relation with national-level representations, because of resources. But we noticed that these national representations didn’t represent the local groups. Or maybe they represented them, maybe ‘representation’ is not the word but what we saw was a lack of coordination between them, a lack of communication. [Our emphasis]

Limited resources forced the MHD to work with one macro-organisation, despite the awareness of its lack of representation, coordination and communication with other organisations. Representation became secondary after ‘the representative’ is formally and irreversibly constituted. This is confirmed by Lidia:

Let’s see, I can talk about 2005-2006 … that was the last year in which we [at the MHD] had an important number of registered organisations. I don’t remember exactly but they were more than 100, with name, address, and membership. We did that [kept a register of organisations] only until then. After that, in a way, we have rested on the assumption that CORFAUSAM has that information, that CORFAUSAM unifies, that CORFAUSAM mediates, etc. Do you see? So, we’ve been devolving too many responsibilities on CORFAUSAM, but without working too much with them, just assuming that they know . [Our emphasis]

In a burgeoning and diverse world of locally organised family groups, one organisation had to be selected in order to reduce the complexity of engagement. More than an attribute of the representative based on its commonalities or similarities with other organisations, representation was the outcome of a pragmatic act of selection by the mental health system. Thus, CORFAUSAM was given the role of representative, even in the face of its acknowledged failures of coordination and communication with those it was expected to ‘represent’.

Third process: The National Commission for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illnesses (NCP) and decisions on coercive measures

One of the thorniest aspects of deinstitutionalisation was the regulation of coercive measures, particularly forced hospitalisations. In 1998, decree 570 was implemented, ‘to regulate the forced hospitalisation of people with mental health problems and the services that provide it’. This decree explicitly required decisions upon forced hospitalisation to be approved by a panel of representatives of legal and scientific bodies, and also of users and family organisations. The panel was termed the NCP. The requirement of user representation led to the creation of ANUSSAM.

The NCP, of which I’m a member right now, has one or two representatives from users’ groups and that’s their channel, and that helps and limits. Users’ groups understand I think, that this is their only way to exchange and participate, and nothing else. (Fernando Flores)

Users became visible by the legitimacy they could add to a complex decision-making process. A specific role was required and formalised, and only then an invitation was extended. And, as Fernando Flores comments, this became the main, if not the only channel for users to express their views. At the same time, participating in a legally endowed group able to make decisions on coercion enriched and gave added justification to the notion of users’ involvement, where previously only families had been addressed. This space for the first time differentiated the position of ‘the user’, assumed the existence of a ‘user perspective’, and allowed users to make a difference. According to Javiera Reyes:

I would say that the only moment in which users had a real voice, such as Valeria, was in the National Commission. She was the only one that was able to show differences with the rest, to demand things. Family representatives did not.

Fourth process: ANUSSAM, and a point of view emerges and evolve

The need for wider political support pushed the MHD to work with family organisations and, indirectly with users. But the need to regulate decisions upon coercion differentiated, for the first time, the voice and the contribution of users. By the late 1990s, Valeria Canales was a member of CORFAUSAM and from there she became the first service user in the NCP. In trying to explain what happened then – and still happens – she commented:

A thing that users have against them is the fact that people with mental disability, according to the traditional concept, can’t be healed, there’s no cure. They are a problem so, ‘what do we do with mental disability?’ That is the big question that medicine, and society in general, obsess about: ‘what should we do?’ [Our emphasis]

Valeria was aware of something of which policy-makers and other interviewees were not. Users had been framed strictly as a problem and, until that point, for authorities, professionals and families alike, they were visible only through that distinction.

(…) there was no participation, no users’ organisations at that time, and it wasn’t clear if users’ organisations could live peacefully with family organisations. It wasn’t easy because we needed identity, autonomy and empowerment. Families were more … protective or paternalistic, reproducing the dependencies and subordinations. For me, that wasn’t a proper environment for the development of users’ organisations with their own identity and autonomy.

With this in mind, Valeria proposed the idea of a user organisation to the authorities in the MHD. Among users, she approached sociology professor Gonzalo Poblete who became the leader of ANUSSAM since its birth in 2000. Their relation with family groups was among the first challenges.

Initially, we wanted to form an organisation together with family groups. They came to the first meetings, we had the user and the relative, father or mother, and they didn’t allow the user to talk. After that, we knew we had to do this independently because re-adaptation to the family of origin is a component in the users’ mental health treatment. At the end, if the relative is there, only his voice is heard, not the voice of users.

Autonomy could only be cultivated on the margins of family, both at an individual level and at an organisational level. And the same principle applied to mental health services.

(…) in the first assemblies, we were able to bring 80, even 90 users, big numbers. But … when we started to learn and discuss more critically about services, this growth started to decay (…) families started to ask ‘why do you need to go to these meetings?’ Users came, encouraged by services, but only as long as we had a positive view of services.

ANUSSAM was not born as a small-scale initiative, growing into a national organisation through collective action, as observed in the UK, the USA, and Canada. The organisation was supposed to be big and strong from the beginning, a legally preconfigured entity with a specific internal organisation so that it could accomplish the function that the NCP and the MHD required. In the words of Jorge:

We are a corporation, and this is very demanding. According to our legal statutes, we can create schools, even health services, it’s a very powerful figure. (…) But we’ve never had that because we have no resources. We don’t even have our own place to meet.

It is hard to understand how the organisation has managed to remain active over the years. They use the channels provided by the MHD, and over time other state agents have come to value their role as representing ‘the user perspective’, particularly SENADIS, the national disability service. But even when talking about how exhausting and unrewarding their roles can be, the leaders express a parallel sense of achievement, mainly illustrated by moments of recognition, invitations to high-level meetings, and participation as experts in policy processes, including the NCP, and the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. They were the vanguard, becoming the first users in places dominated by medical and administrative authority.

Fifth process: AUGE

In 2005, four years after the creation of ANUSSAM, a new reform process became national law: the AUGE reform. Its aim was to expand access to health care to all Chilean citizens suffering from one or more diseases included on a priority list. Diseases were selected on the basis of four criteria: the burden of disease; effectiveness of treatment; capacity of the health system and costs. The AUGE reform brought fresh funding for the still ongoing deinstitutionalisation process, and, over its three first years, the MHD managed to include three mental health conditions (Schizophrenia, Depression, and Drugs and Alcohol Abuse), but at a price. Talking about the effect of this reform, Fernando Flores:

Yes, clearly, I would say indirect, unnoticed, unpremeditated. But certainly, when we got schizophrenia into the AUGE, it was impossible to include something for the caregiver within that package, something for self-help groups or for protected homes. Then, by exclusion, this weakened the social participation of carers and groups.

The selection of diseases had to be accompanied by a rigorous and narrowly biomedical definition of a treatment, in the form of a ‘package’. Services of all kinds became rigorously quantified, for this was the only way to introduce fairness and control in the administration of health resources. This had further consequences:

The reform demanded documents and guides. A guide wasn’t only for the public system; it was also for the private. Therefore, we were instructed to work only with evidence, so evidence reviews became more important. We had to work primarily with scientific societies and users were left behind. The health ministry didn’t include users, and we had so many goals to achieve that users were left behind. The same with money, we had to fight for every penny from the head of finances in the Ministry, he looked at our packages asking ‘what is this? a community activity?’ I mean, they opposed everything related to community-based activities, it was a technocratic nightmare. (Nicolás Galiani)

‘Evidence’ became the main criterion not only for the definition of treatments but, indirectly, for the selection of voices authorised to make that definition. According to Lidia Hernández, who experienced this process from the beginning:

Somehow we are commanded to base everything we say on evidence. Since our role is to make policy, programmes, protocols, norms, guidelines … everything has to be universal. So you look for evidence that says, for example, how important is social participation in the treatment of schizophrenia. You write the terms and make a search, and nothing, there’s nothing.

As well as changing the ecology of ‘stakeholders’, AUGE introduced an added organisational dimension that further affected the relation with users. According to Lidia Hernández:

So, from 2005 onwards, with the sectoral reform [AUGE] came the division of functions. We [the MHD] remained in the Public Health Division, the area where policies, norms and protocols are elaborated. Our budget was also split, and all the funding remained in the hands of the other division, in charge of implementation. Our budget was reduced, our administrative possibilities to work more directly and systematically with users are very limited. All we did up until that moment was stopped.

According to all the participants, since the mid-2000s, there have been no major transformations or improvements in the formal relation between the mental health system and users’ organisations. The last survey of organisations operating in the country was conducted in 2005. After that, the role of interaction with the universe of users was assumed by CORFAUSAM, an organisation that has been explicitly questioned by authorities and users alike.

Although a new Mental Health Plan has recently been approved (Ministerio de Salud, Citation2017), Chile does not have a Mental Health Law, deinstitutionalisation is stalled and funding remains below PAHO's standard. In this sense, the fragility of ANUSSAM matches the patchy modernisation of the sector and its diminished position in the wider context of the health system.

Discussion

Direct initiatives by users could have emerged but users have not had the ability to develop a powerful claim, or to develop a self-help movement, or for advocacy, or to multiply organisations … there’s no activist organisation across users, no activism to create new organisations, there’s no power, no empowerment to engage with the legislators and authorities. And there’s no working methodology within them – (Nicolas Galiani).

Interestingly, this quote matches what is expressed in the latest WHO AIMSs: ‘a low presence and a poor level of organisation of the mental health users and family members’ associations are still observed’ (World Health Organization, & Ministerio de Salud, Citation2014, p. 11). This is the representation that currently circulates as fact at a national and global scale.

But when the position and value of user organisations are placed in the context of larger institutional changes in the mental health system, a different image emerges. According to this reconstruction, and in line with critical approaches in the field (Brosnan, Citation2012; Carr, Citation2007; Lewis, Citation2014; Pilgrim, Citation2005), the visibility and organisational potential of users has historically responded to specific policy scenarios and institutional requirements external to users themselves, scenarios configuring specific forms of representation and relevance.

Our reconstruction shows that, for the prospect of deinstitutionalisation, families became a key resource and ally, initiating a process of organisation, guided by a real need for support and information. Eventually, one organisation, CORFAUSAM, assumed the role of representative, engaging directly with the MHD. It was the need for expanded political support for the second mental health plan which created the impetus for formal, national-level family representation. The agency was not one-sided; these processes opened possibilities of reciprocal adaptation, guided by a horizon of action that went beyond each side’s interests: deinstitutionalisation. More importantly for the aims of this paper, the sequence of policy scenarios created a dual framing for the observation of organisations working outside the clinical realm: As collaborators, articulated with the system’s plans and actions and, at the same time, as carriers of true advocacy and representation. This dual framing conditioned the way in which user organisations would eventually be configured and approached.

The need to legitimise decisions about coercion differentiated, for the first time, users from family representatives. Only at the interface between the medical and legal systems did users acquire visibility, not just as supporters of the MHD’s request for funding and relevance, but as users, with an irreplaceable perspective on the damage and consequences of coercive measures. Users on the NCP would be claiming to ‘represent’ users, and ANUSSAM was created as a national organisation to allow that claim. Again, it would be a mistake to frame this process as simple utilisation or co-option. The legal side effects of deinstitutionalisation gave users a role in deciding what could be done against the will of other users. Thus, users were constituted as independent stakeholders.

However, the channel opened by the NCP became the only formalised space for users to be heard. Any potential growth in this relation was blocked by the AUGE reform of 2004. AUGE, with its imperative of equity in the distribution of services, transformed the way in which diseases were conceived and treatments designed and, as a side effect, the way users and their experiences were valued and dealt with by the system. Since the plan meant secure funding, political support from users was no longer needed and the clinical distinction prevailed, framing users, again, as a problem, and not as a stakeholder with a specific contribution to make. If users were engaged at all, they were approached through the representation of CORFAUSAM and ANUSSAM, whose authenticity was questioned, both by authorities and by users, because of their proximity to the MHD.

In this sense, in the context of a fragmented mental health system struggling for its own stability, the legitimation that users can add only makes a difference in relation to certain decision-making scenarios. The value of ‘experience’ is differently constituted or commodified (Renedo, Komporozos-Athanasiou, & Marston, Citation2017) in the context of evidence-based policy reforms (as in the AUGE process) than in the context of medico-legal procedures to decide on the administration of forced treatment. While in the first context statistical evidence of treatments carries more weight than user experiences for the definition and communication of protocols, decisions upon coercion carry an irreducible controversy that cannot be closed through evidence and protocols, actualising a requirement of legitimacy that gives value to users’ experiences and claims.

In our reconstruction both scenarios are simultaneous, they are both aspects of the modernisation of the mental health system, understood, following Luhmann, as increased differentiation across internal domains (Castel, Citation1975; Luhmann, Citation2013). This is accompanied by a differentiation in the observation and the relevance afforded to users and their organised activities. In this sense, a critique of definitions and initiatives of participation within mental health systems needs to be matched by a recognition of the internal complexity of this field and its process of historical stabilisation within the health system and other relevant contexts such as the legal system. This dual attention makes possible the second order observation of how users are observed.

Conclusions

Historicising involvement

The declaration of user organisations’ low presence and fragmentation in Chile, as in many other countries, should not be seen as ‘inaccurate’ in a purely referential sense. As a snapshot of the current level of organisation and the strength of users’ influence in policy, the assessment is not substantially different from what users themselves say about their current capacity to organise and mobilise others. But, in the words of Gadamer, ‘we miss the whole truth of the phenomenon – when we take its immediate appearance as the whole truth’ (Gadamer, Citation2004, p. 300). Only through the inclusion of time is possible to see the snapshot itself as the result of contingent institutional drifts shaping the visibility of users.

For this reason, we suggest a historicisation of users’ involvement as a meaningful category in the mental health field. Tracing the concrete processes underlying how the meaning and value of involvement has shifted gives contextual substance to the notion of participation (Campbell & Burgess, Citation2012) against a purely technical or clinical justification. In this sense, involvement cannot be prescribed or simply ‘implemented’ as an item in a context-indifferent formula for a modern mental health system, as framed in the Global Mental Health Action Plan and other international calls (Saxena & Setoya, Citation2014; World Health Organization, Citation2013). Instead, these calls and their local uptake constitute an opportunity for a more substantial discussion about the contexts, meanings, and practical expressions of involvement.

Moreover, recognising the temporal dimension of involvement opens analytic alternatives to a normative critique of ‘failures’ of participation common in the literature (Brosnan, Citation2012; Lewis, Citation2014; Pilgrim, Citation2005). Instead of evaluating involvement within a fixed normative grid, which Contandriopoulos calls the classical approach to public involvement in health (Citation2004), our reconstruction points to an assemblage of policy requirements and instances of self-identification (Voronka, Citation2017), multiplying sites of agency and shaping the subsequent parameters of visibility. While authorities ascribe agency and responsibility to themselves, users and families also created opportunities, while all groups were subject to deep transformations in the mental health system and its relation to other powerful systemic forces, as a sociosystemic framework can elucidate.

A systemic view on mental health and users’ involvement

Across our history, processes of selection and need for legitimation explain why and how users became relevant as a group on the basis of the mental health system’s changing requirements (El Enany et al., Citation2013; Harrison & Mort, Citation1998). A systemic approach radicalises and enriches this insight by framing the mental health system as a social system, and users as shifting in and out of the system’s scope of visibility or relevant environment. For the mental health system, the actions of users have to be dealt with selectively, in the context of multiple simultaneous requirements and pressures coming from other systems (the legal system, the political system and, particularly, the broader health system). The dominant framework for the selection of users’ communications and actions is the clinical distinction between health and illness. This is the distinction that justifies the very existence of the mental health system, and, as such, guides the way in which the system observes its outside, allocating relevance or irrelevance to specific ‘irritations’ (Luhmann, Citation1995). In this context, the involvement of organised users and the recognition of their forms of self-advocacy constitutes a double improbability: The fundamental improbability, for users, of being observed and recognised outside the guiding distinctions of the system, and, if this happens, the improbability of their views matching the selectivity of the system, and being incorporated into its own operations.

On the other hand, a systemic framework places the emphasis on contingency rather than on any particular telos towards which institutions or civil society agents move (Mascareño, Citation2006). Post-dictatorship mental health policy can be seen as a fragile, meandering realm in permanent search of stabilisation, jumping onto opportunities of relevance and experimenting with its own identity (Pors, Citation2012). In analytical terms, and against a tendency to locate power and control exclusively in the hands of the mental health system, a systemic perspective invites us to see the shifts in mental health policy as responses and strategic adaptations to an ecology of systems which compete for resources and establish the terms of legitimacy of different actors. In other words, the notion of authenticity needs to be studied as a communicative tool within contingent policy scenarios, and not simply assumed as a parameter of evaluation of the action of users and other groups outside the mental health system.

Two further challenges stem from this perspective. First, a challenge to explore the analytical potential and limitations of systems theory for the observation of policy as a contingent realm where groups in society are produced and observed. And second, more politically, a challenge to historicise involvement and reconstruct its contingent basis as the grounds for the strategic irritation and transformation of mental health systems.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica and London School of Economics and Political Science.

References

- Alarcón, R. D., & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. A. (2000). Mental health policy developments in Latin America. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78(4), 483–490.

- Caldas de Almeida, J. M. (2005). Estrategias de cooperación técnica de la Organización Panamericana de la Salud en la nueva fase de la reforma de los servicios de salud mental en América Latina y el Caribe [Strategies for technical cooperation of the Panamerican Health Organisation in the new phase of reform of mental health services in Latin America and the Caribbean]. Rev. Panamá Salud Pública, 18, 314–326.10.1590/S1020-49892005000900012

- Araya, R., Alvarado, R., & Minoletti, A. (2009). Chile: An ongoing mental health revolution. The Lancet, 374(9690), 597–598.10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61490-2

- Brosnan, L. (2012). Power and participation: An examination of the dynamics of mental health service-user involvement in Ireland. Studies in Social Justice, 6(1), 45–66.10.26522/ssj.v6i1.1068

- Campbell, P. (1996). The history of the user movement in the United Kingdom. In T. Heller, J. Reynolds, R. Gomm, R. Muston, & S. Pattison (Eds.), Mental health matters: A reader (pp. 218–225). London: Macmillan Education.

- Campbell, C., & Burgess, R. (2012). The role of communities in advancing the goals of the movement for global mental health. Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(3–4), 379–395.10.1177/1363461512454643

- Carr, S. (2007). Participation, power, conflict and change: Theorizing dynamics of service user participation in the social care system of England and Wales. Critical Social Policy, 27(2), 266–276.10.1177/0261018306075717

- Castel, R. (1975). Genèse et ambiguïtés de la notion de secteur en psychiatrie [Genesis and ambiguities of the notion of sector in psychiatry]. Sociologie Du Travail, 17, 57–77.

- Castel, F., Castel, R., & Lovell, A. (1982). The psychiatric society. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Contandriopoulos, D. (2004). A sociological perspective on public participation in health care. Social Science & Medicine, 58(2), 321–330.10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00164-3

- Cook, J. A., & Jonikas, J. A. (2002). Self-determination among mental health consumers/survivors: Using lessons from the past to guide the future. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 13(2), 87–95.

- Dannreuther, C., & Gideon, J. (2008). Entitled to health? Social protection in Chile’s plan AUGE. Development and Change, 39(5), 845–864.10.1111/dech.2008.39.issue-5

- El Enany, N., Currie, G., & Lockett, A. (2013). A paradox in healthcare service development: Professionalization of service users. Social Science & Medicine, 80, 24–30.10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.004

- Forbes, J., & Sashidharan, S. P. (1997). User involvement in services– Incorporation or challenge? British Journal of Social Work, 27(4), 481–498.10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011237

- Gadamer, H.-G. (2004). Truth and method. (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.). New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Grele, R. J. (1996). Directions for oral history in the United States. In D. K. Dunaway & W. K. Baum (Eds.), Oral history: An interdisciplinary anthology (pp. 62–83). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Harrison, S., & Mort, M. (1998). Which champions, which people? Public and user involvement in health care as a technology of legitimation. Social Policy & Administration, 32(1), 60–70.10.1111/spol.1998.32.issue-1

- Hutta, J. S. (2010). Paradoxical publicness: Becoming-imperceptible with the Brazilian LGBT movement. In N. Mahony, J. Newman, & C. Barnett (Eds.), Rethinking the public: Innovations in research, theory and politics (pp. 143–161). Bristol: Policy.

- Lewis, L. (2014). User involvement in mental health services: A case of power over discourse. Sociological Research Online, 19(1), 6.

- Luhmann, N. (1995). Social systems. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Luhmann, N. (2012). Theory of society, volume 1. (R. Barrett, Trans.). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Luhmann, N. (2013). Theory of society, Volume 2. (R. Barrett, Trans.). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Maass, J., Mella, C., & Risco, L. (2010). Current challenges and future perspectives of the role of governments in the psychiatric/mental health systems of Latin America. International Review of Psychiatry, 22(4), 394–400.10.3109/09540261.2010.500876

- Marconi T. J. (1999). La reforma psiquiátrica en Chile: Precedencia histórica de los problemas del alcohol 1942-2000 [The psychiatric reform in Chile: Historical precedence of alcohol problems 1942–2000]. Cuadernos Médico Sociales (Santiago de Chile), 40(2), 33–40.

- Martin, G. P. (2008). Representativeness, legitimacy and power in public involvement in health-service management. Social Science & Medicine, 67(11), 1757–1765.10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.024

- Mascareño, A. (2006). Ethic of contingency beyond the praxis of reflexive law. Soziale Systeme, 12(2), 274–293.

- Milewa, T., Valentine, J., & Calnan, M. (1999). Community participation and citizenship in British health care planning: Narratives of power and involvement in the changing welfare state. Sociology of Health & Illness, 21(4), 445–465.10.1111/shil.1999.21.issue-4

- Ministerio, de Salud (2017). Plan Nacional de Salud Mental 2017–2025. Santiago: Ministerio de Salud.

- Minoletti, A., & Zaccaria, A. (2005). Plan Nacional de Salud Mental en Chile: 10 años de experiencia [National mental health plan in Chile: 10 years of experience]. Revista Panamericana de Salud, 18(4–5), 346–358.10.1590/S1020-49892005000900015

- Minoletti, A., Rojas, G., & Sepúlveda, R. (2010). Notas sobre la historia de las políticas y reformas de salud mental en Chile [Notes on the history of mental health policies and reforms in Chile]. In M. A. Armijo (Ed.), La psiquiatría en Chile: Apuntes para una historia (pp 132–154). Santiago: Andros Impresores.

- Minoletti, A., Sepúlveda, R., & Horvitz-Lennon, M. (2012). Twenty years of mental health policies in Chile: Lessons and challenges. International Journal of Mental Health, 41(1), 21–37.10.2753/IMH0020-7411410102

- Missoni, E., & Solimano, G. (2010). Towards universal health coverage: The Chilean experience. World Health Report.

- Perks, R., & Thomson, A. (1998). The oral history reader. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203435960

- Pilgrim, D. (2005). Protest and co-option – The voice of mental health service users. In A. Bell & P. Lindley (Eds.), Beyond the water towers: The unfinished revolution in mental health services (pp. 1985–2005). London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

- Pors, J. G. (2012). Experiencing with identity. Paradoxical government in times of resistance. Tamara: Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry, 10(3), 33.

- Renedo, A., Komporozos-Athanasiou, A., & Marston, C. (2017). Experience as evidence: The dialogic construction of health professional knowledge through patient involvement. Sociology. doi: 10.1177/0038038516682457

- Saxena, S., & Setoya, Y. (2014). World health organization’s comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 68(8), 585–586.10.1111/pcn.2014.68.issue-8

- Scheper-Hughes, N., & Lovell, A. M. (1986). Breaking the circuit of social control: Lessons in public psychiatry from Italy and Franco Basaglia. Social Science & Medicine, 23(2), 159–178.10.1016/0277-9536(86)90364-3

- Tomes, N. (2006). The patient as a policy factor: A historical case study of the consumer/survivor movement in mental health. Health Affairs, 25(3), 720–729.10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.720

- Tovey, P., Atkin, K., & Milewa, T. (2001). The individual and primary care: Service user, reflexive choice maker and collective actor. Critical Public Health, 11(2), 153–166.10.1080/09581590125146

- Voronka, J. (2017). The politics of ‘people with lived experience’ experiential authority and the risks of strategic essentialism. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 23(3–4), 189–201.

- World Health Organization. (2013). WHO mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva: Author.

- World Health Organization, & Ministerio de Salud (2014). Informe WHO AIMS sobre el Sistema de Salud Mental en Chile: Segundo Informe [WHO AIMS Report on the Chilean Mental Health System: Second Report]. Santiago de Chile: WHO.