ABSTRACT

Despite of high annual rate of surgery worldwide, few national-level studies have explored the epidemiological aspects of various types of hernia repairs. Our study aims to examine the 5-year prevalence of hernia repairs in Australian adults. The number of hernia repair surgeries for femoral, inguinal, incisional, other abdominal, and epigastric hernias were extracted from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) database from financial year (FY) FY2017 to FY2021. We calculated age-specific prevalence and prevalence ratio (PR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) to compare the prevalence of hernia repairs by age group and sex. The highest prevalence per 100,000 population of hernia repairs was found in inguinal (223), followed by epigastric (111), other abdominal (59), incisional (52), and femoral hernia (10). People over 65 years old had highest PR of hernias. There was a gender-wise variation across types of hernia procedures. Around 89.6% of patients with inguinal hernia repairs were males, while only 10.4% were females. The PR was lower in males for femoral and incisional hernia when compared two genders with corresponding age groups. Women in the pregnancy group (20–39 years) had a high risk of ventral hernia repair when compared to males. Groups of patients who have higher risks of hernia repair should be prioritized for healthcare service delivery, but more research is needed in hernia epidemiology, in Australia and internationally. Also, our study could serve as a national and international reference for other hernia repair studies where healthcare system is comparable.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Hernia is one of the most common medical conditions with approximately 20 million hernia repair procedures conducted every year globally (The HerniaSurge Group, Citation2018). In Australia, there were 175,000 incisional hernia repairs performed from 2000 to 2021 (Gillies et al., Citation2023), and over 56,000 inguinal hernia repairs in the year 2014/2015 (Williams et al., Citation2020). Among hernia repairs, inguinal hernia repairs are the most frequently performed, followed by umbilical, incisional, and femoral hernias (Malangoni & Rosen, Citation2004; Seker et al., Citation2014).

The risk of developing hernias is higher in older people than in younger age groups, and the risk differs by gender (Caglià et al., Citation2014; Hoffmann et al., Citation2023; Perez & Campbell, Citation2022). For inguinal hernia, the prevalence of inguinal hernia has been reported to be 5% in the youngest age group (25 to 34 years), increasing to 45% in men 75 years and older (Perez & Campbell, Citation2022). Males have a far higher incidence of inguinal hernia compared to females, with lifetime risks of 27% and 3% respectively (Kingsnorth & LeBlanc, Citation2003). Yet, in contrast to inguinal hernia, incisional hernias are more common in females (Zhang, Citation2015). Most ventral hernias (umbilical, epigastric, spigelian, and incisional hernias) occur in people over 40 years old (Le Huu Nho et al., Citation2012; Zhang, Citation2015). Hernia may trigger discomfort and abdominal pain for the patients, and in more severe cases, it may lead to strangulation of the bowel, which requires emergency surgery (Birindelli et al., Citation2017).

Despite of high annual rate of surgery worldwide, few studies have examined the epidemiology of various types of hernia, and in particular, hernia repair procedures on a large-scale nationwide level (Turaga et al., Citation2006). For low- and middle-income countries, this can be explained by the lack of high-quality large-scale databases (Koumamba et al., Citation2021). Conversely, Australia provides accessible and affordable public healthcare, including surgery for all Australian citizens through a universal public health insurance program, which facilitates carrying out high-quality nationwide large-scale studies related to medical operations such as hernia repairs. Williams et al. (Williams et al., Citation2020) explored the trends of inguinal hernia repair in Australia over 15 years from 2000/01 to 2014/15, using data extracted from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), an independent statutory Australian Government agency (Gebremedhin, Citation2022). Gillies et al (Gillies et al., Citation2023). also used the AIHW data to examine the trend of ventral hernia in Australia from 2001 to 2021. The results from these studies showed that there have been little changes in the rate of inguinal and ventral hernia repair during the last decades in Australia. However, the comprehensive understanding of hernia repair prevalence by age and sex for all hernia types has not been fully explored yet.

Therefore, we aimed to conduct a comprehensive study to assess the five-year age-standardized prevalence of various types of hernia repairs by stratifying those rates by gender and age among Australian adults, using AIHW data between financial year (FY) FY2017 and FY2021. The results of our study are essential for healthcare leaders and policymakers to estimate hernia repair prevalence in populations of different age groups and both sexes, determining the target groups with the most demands for medical services. Additionally, our study results will contribute to understanding the epidemiological aspect of hernia, in terms of the prevalence of hernia repair in the population age groups and by gender. The results are useful in international contexts and research in other countries that are comparable of healthcare system. Low- and middle-income countries with limited nationwide large-scale can use our study results for understanding the groups of hernia patients that have most demands for medical services.

Methods

Study design and data extraction

We collated data on the total number of hernia repair surgeries from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW) National Hospital Data Collection (AIHW, Citation2022/2023) covering the period from FY2016–17 to FY2020–21. We only examined the rate of hernia repair for various hernia types in the last five years because there were no remarkable changes in rates observed in Australia throughout the last 15 years, as reported by Gillies et al (Gillies et al., Citation2023). and Williams et al. (Citation2020). From the AIHW data cubes, we selected 19 specific procedures comprising five categories of hernia repair subchapters (see Supplement Table A1 for details). Ventral hernia or abdominal hernia includes umbilical, epigastric, spigelian, and incisional hernia (Kalyan et al., Citation2022), while groin hernia includes inguinal hair and femoral hernia (Burcharth et al., Citation2013).

Therefore, we classified hernia repair into five categories, namely, femoral, inguinal, incisional, other abdominal hernia, and epigastric hernia. There is a variability in the definition of hernias in literature and a lack of specification, especially in terms of ventral hernias (Blonk et al., Citation2019; Muysoms et al., Citation2009). Umbilical hernias are considered similar to epigastric hernias, except they develop specifically at the umbilicus (Bradley & Cosgrove, Citation2011). In this study, we included umbilical and linea alba hernia as epigastric hernia (Table A1) and examined the five-year prevalence of ventral (incisional, epigastric, and other abdominal hernia), and groin hernia (inguinal and femoral hernia) repairs. Corresponding population data were accumulated from Australian Demographic Statistics compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, Citation2023).

Ethics statement

The study was supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Ideas Grant (APP2002589). The authors clarify that informed consent was not obtained from the participants because the study was based on publicly available data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) database.

Statistical analysis

We used a set of descriptive statistics to analyze the prevalence of hernia repair procedures using bar graphs, as well as tables, for each type of hernia.

To estimate the overall age-specific prevalence of hernia repair in the adult Australian population, we aggregated the procedure volume of different types of hernia repair and analyzed the rate of hernia repairs per 100,000 adults aged 20 years and above. In addition, age-standardized prevalence of all hernia repairs per 100, 000 adult population was calculated using the 2001 Australian standard population as the reference. Subsequently, for an age-wise comparison, we classified the Australian adult population into three categories following the suggestions from existing literature (Zhang, Citation2015) and calculated the age-specific prevalence ratio (PR) along with their 95% confidence interval (CI) to compare the prevalence of hernia repair by gender and by age groups. We used RStudio version 1 April 1717 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for all statistical analyses.

Results

Overall prevalence of hernia repair

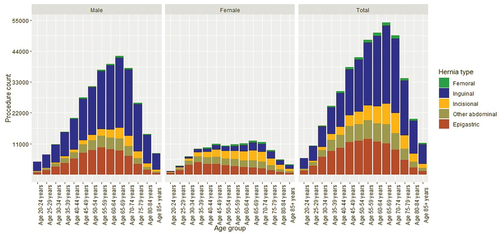

From FY2016–17 to FY2020–21, a total of 435,826 procedures for all types of hernia repairs were performed on adult patients (aged 20 years and above) in Australia, in which, inguinal hernia repair was the most frequently performed procedures, with a total of 212,832 procedures, followed by epigastric hernia repairs (). The median age group for femoral, inguinal, incisional, other abdominal hernia, and epigastric repair were 55–59, 60–64, 60–64, 55–59, and 50–54 years old, respectively (). The age bracket of 60–64 years had the highest total of hernia repair procedures for all hernia types in our study. Males had more hernia repair procedures than females for all age groups and showed the highest total number of hernia repairs in the 65–69 years old ().

Table 1. The 5-year prevalence of hernia repairs operations performed by age and gender in Australia from FY2016–17 to FY2020–21.

The crude average prevalence of inguinal hernia repair procedures per 100,000 of the adult population annually was 223 (range 211–238), the most performed hernia surgery, whilst epigastric hernia repairs, the second most frequently performed repairs, averaged 111 per 100,000 population (range 101–114) ().

Among femoral and inguinal hernia repairs, nearly half of the operations were laparoscopic surgery (40.4% and 49.7%, respectively). Approximately two-thirds of incisional hernia repair operations were done using prostheses (mesh) (71.6%), a similar figure as to other abdominal hernia repair (72.1%) ().

Age-wise distribution and variation in hernia repair procedures

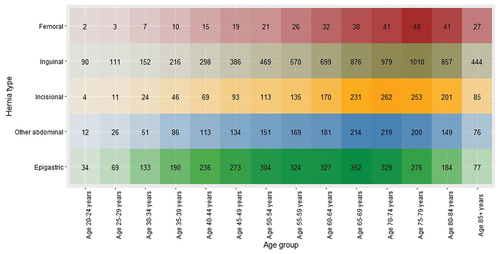

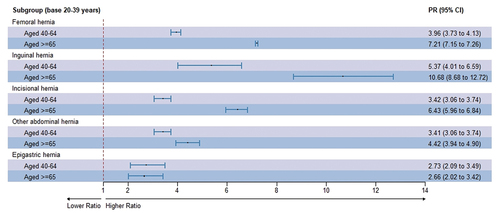

The age-specific prevalence per 100,000 population of each of the five types of hernia repairs is presented by the heatmap (). The age distribution of hernia repair procedures is proportional to the heatmap colour for each hernia, i.e. the darkest shades of the heatmap denote the age bracket with the highest prevalence. For inguinal and incisional repairs, the highest age-specific prevalence per 100,000 adult population was observed for the age bracket of 60–74 years. For abdominal and umbilical hernia repair, the highest prevalence was recorded for patients aged 55–69 years. The age-specific prevalence ratio (PR) of hernia repairs also describes similar stories (). Regardless of the types of hernia repair procedures, the PR was highest among the age group over 65 years for hernia repairs compared to the reference group of 20–39 years in various hernia types ().

Gender-wise variation in hernia repair procedures

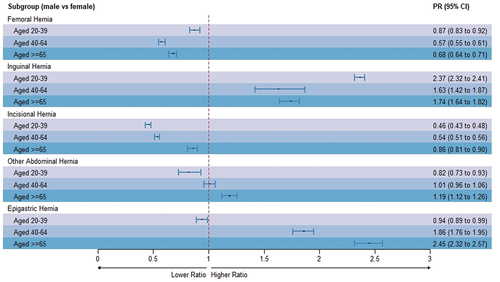

There was a gender-wise variation across types of hernia procedures. For example, 89.6%, of patients with inguinal hernia repairs were males, while only 10.4% were females, and the age-standardized prevalence in men was more than seven times that of females (). Males were found to have a higher age-standardized prevalence of other abdominal hernia repair and epigastric hernia repair than females, in contrast, females had a higher age-standardized prevalence of incisional and femoral hernia repair than males ().

Regarding the prevalence by gender and age groups, as seen from , the total number of procedures for hernia repairs was highest in age brackets 65–69 for femoral and inguinal hernia repair, incisional, and other abdominal, and in age brackets 60–64 for epigastric hernia repair in both sexes. While this pattern was similar in males for all hernia repair types, there were several noticeable differences in the data for females, where the highest number of epigastric, and other abdominal hernia repairs were w found in younger age groups, 30–34 and 35–39 years respectively ().

Thus, the PR of hernia repair was calculated to explore in detail the difference in hernia repair prevalence by age and sex (). The PR of inguinal hernia repairs was higher in males than in females across all age groups. The PRs of femoral and incisional hernia repair were found to be lower among the male cohort than their respective female age brackets for all age groups. The PR among the male cohort was higher than females in age brackets 40–64 years and aged 65 years or above for other abdominal and epigastric hernia repairs. However, PRs in the younger male cohort at 20–39 years old were lower than the female 20–39 years old cohort for abdominal hernia repair and epigastric hernia repair, respectively ().

Discussion

We found that inguinal hernia repairs were the most frequently performed procedure, overall, and this was driven by the high number of males who had inguinal hernia repair. In all age groups, the age-specific prevalence was higher in males than females for inguinal hernia repair, conversely for incisional and femoral hernia repairs where the age-specific prevalence was higher in females than males. For epigastric hernia, females in the pregnancy age group (20–39 years old) have a higher risk than males of the same age group.

Groin hernia

In our study, the ratio of males to females for inguinal hernia repair prevalence was 8:1. Consistent with our findings, some studies showed that males had a higher risk of having hernia surgery compared to females. For example, the Nationwide cohort study in Denmark (Burcharth et al., Citation2013) found that males contributed to 90.2% of the total inguinal hernia repairs, while females only 9.8% for the period five years 2006–2010. The national cohort study in Turkey, consistently, pointed out that around 87.7% of inguinal hernia repair operations were performed in male populations, whereas only 12.3% were females (Seker et al., Citation2014).

We found the highest of inguinal hernia repair was conducted in the age group of 65 years and over. This is concordant to previous findings of other authors. For instance, Ruhl et al (Ruhl & Everhart, Citation2007). found that the oldest group over 74 years old had the highest inguinal hernia incidence. The study in Denmark highlighted that the peak age for the age-specific prevalence of inguinal hernia repair was 75–80 years old (Burcharth et al., Citation2013). The finding that inguinal hernia repairs were less common in females than males can be explained by anatomical differences, i.e. the male inguinal canal is narrower compared to females, predisposing to hernia development. Conversely, regarding femoral hernia repair, we found that the rate was higher in females compared to males, and this is concordant with other authors’ findings (Andresen et al., Citation2014; Lockhorst et al., Citation2020). Women are more likely to have femoral hernia due to wider pelvis than men.

Ventral hernia

In terms of ventral hernia repair prevalence by gender, there are diverse findings from the previous studies, with some studies showing a higher incidence of umbilical hernia repairs in males (Burcharth et al., Citation2015; Helgstrand et al., Citation2013) while others suggesting higher incidence in females (Cassie et al., Citation2014). Likewise, incisional hernia repair incidence was reported higher in females (63.9%) compared to males in a population-based cohort study in the US in 2018 (Flum et al., Citation2003), but lower in females than males in a cohort study in Germany 2017 by Koscielny et al (Koscielny et al., Citation2018). The reasonable explanation for the difference of conclusions among these studies is that there were differences in sample sizes and participants were recruited in the studies.

We found that the five-year prevalence of incisional hernia repair was higher in females than in males, but for epigastric and other abdominal hernia repairs, it was lower in females than in males. The higher prevalence of hernia in males compared to females may be attributable to other risk factors such as more comorbidities or more intense physical activities in males than females (Schlosser et al., Citation2020). In a retrospective observational study of 90,056 surgical outpatients in India (Pandya et al., Citation2021), the ratio of male to female adults for overall abdominal hernia surgery (including groin hernia, umbilical, and epigastric hernia) was 9:1 which could be explained by a higher prevalence of chronic smoking, strenuous exercises, bladder outlet obstruction, chronic airway disorders, hypertension, cardiology diseases in males than females.

The prevalence of incisional hernia repair, however, is higher in females than males, which can be explained by pregnancy-related risk factors (AhmedAlenazi et al., Citation2017; Rutkow, Citation2003). This was reflected in our study where the five-year prevalence of epigastric hernia repair was higher in males than females for all age groups, except for the 20–39 years age group, the age group subjected to pregnancy.

Moreover, besides the effect of gender factors on hernia repair prevalence (Schlosser et al., Citation2020), the peak of hernia repair prevalence could be affected by the eligibility to get hernia repair surgery in countries, including patients’ health condition, for example, their existing comorbidities, such as chronic obstruction pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, obesity, which is supposed to be increasing with age (Hamilton et al., Citation2021). Therefore, further study into risk factors associated with an abdominal hernia is necessary to explore the aetiology of differences in ventral hernia prevalence by age group and by gender.

Median age difference in hernia repair prevalence

Another interesting finding from our study is that the median age group for hernia repairs is higher than median age figures in low- and middle-income countries such as China (age 49 ± 7.3 years for abdominal hernia repair surgery) (Zhang, Citation2015), India (44 ± 15 years for inguinal hernia repair surgery) (Agarwal, Citation2023), Dominican Republic (35.9 ± 22.7 years for inguinal hernia surgery) (Turaga et al., Citation2006). However, it is similar to other developed countries such as Sweden (60 ± 15.2 for inguinal hernia repair) (Nilsson et al., Citation2016), Japan (69 years for abdominal hernia surgery) (Itatsu et al., Citation2014), and France (59.6 ± 14.7 years for incisional hernia repair hernia) (Ortega-Deballon et al., Citation2023). This difference could be attributed to variations in differences in distribution and characteristics of population age among countries, typically between low- and middle-income versus high-income countries (Preston & Stokes, Citation2012) (for instance, Australia had a high proportion of the elderly age group (AIHW, Citation2023)), and also the medical and healthcare systems, including clinical procedure, facility accessibility, and aged care management at the population level (Gutiérrez-Robledo, Citation2002; Peters et al., Citation2008).

One of our study’s strengths is using comprehensive high-quality AIHW data to map hernia procedures in Australia in the last five FYs between FY2016 and FY2021. Our results can serve as an international reference for hernia studies, particularly in low- and middle-income countries with limited nationwide data for large-scale studies. There are few large-scale studies describing the epidemiology of hernia surgery. One of the most reputable studies is the National Danish study on hernias, which analyzed age-specific prevalence for hernia surgery. However, the risk of hernia repair in each age group and gender for hernia repair has not been fully explored yet. Also, in addition to age-specific prevalence, we examined age-standardized prevalence per 100, 000 Australian adult population for various types of hernia repairs, as it is recommended for comparing different populations (Diaz et al., Citation2021; Perez-Panades et al., Citation2020).

In our study, we use the hernia repair data from AIHW instead of hernia prevalence in the population. The results may underestimate the real prevalence of hernia due to non-operative or delayed surgery management (watchful waiting) as an approach for hernia management in patients who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic (Fitzgibbons et al., Citation2006). However, there is a lack of hernia repair studies to clarify watchful waiting as safe management for hernia, especially regarding umbilical and incisional hernia (Henriksen et al., Citation2020). Hernia surgery is considered the optimal choice for hernia treatment, and patients are likely to transition to surgery during the watchful waiting period (Fitzgibbons et al., Citation2006). Thus, hernia surgery can be considered a good indication to reflect the prevalence of hernias in the Australian population.

Additionally, we did not collect individual data on comorbidities, drug use, hernia surgery approaches (laparoscopic and open hernia surgery by age and gender), and the types of mesh used for different types of hernia patients. Strangulation condition of hernia is important to evaluate the healthcare delivery system, we lack of data for the strangulated hernia classified by each type of hernias in the AIHW database. Although nationwide large-scale data for overall prevalence can help to provide a big picture to explore the hernia situation in a country, further studies should be carried out to understand detailed risk factors associated with the prevalence of hernia.

Conclusion

In Australia, the most frequently performed hernia repair was inguinal. Patients aged 40–64 years had the highest risk of having hernia repairs in both sexes. Males had a higher risk of having inguinal, other abdominal, and epigastric hernia than females for most age groups. Females in the pregnancy age group (20–39 years old) have a higher risk of epigastric hernia than males of the same age group. Those findings from our study can be used to identify the groups that need the most medical services and to develop health campaigns and policies to improve the healthcare system and quality of life for people in these groups. Besides, our study could serve as a national and international reference for other hernia repair studies where healthcare system is comparable.

Authors contribution

Thi Nga Le: Conceptualization and design, formal analysis, methodology, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing, proofreading and final approval. Mohammad Afshar: Formal analysis, methodology, visualization of results, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. Svetla Gadzhanova: Data curation, methodology, writing – review & editing. Renly Lim: Investigation, resources, writing – review & editing. Indu Bala: Resources, software, writing – review & editing. Netsanet Kumsa: Methodology, software, writing – review & editing. Marianne Gillam: Conceptualization and design, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing, proofreading and final approval.

Ethics statement

The study was supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Ideas Grant (APP2002589). The authors clarify that informed consent was not obtained from the participants because the study was based on publicly available data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) database.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (182.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) for funding this research. RL is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (APP1156368). KNB is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) and NHMRC Scholarship for PhD program. Open access publishing facilitated by University of South Australia (UniSA) under the agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) Member Institutions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The present study used publicly available data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) database. The AIHW procedure data cubes can be accessed from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/procedures-data-cubes/contents/data-cubes. The list of selected procedures and the extracted data are available on request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2024.2351981

Additional information

Funding

References

- ABS. (2023). National, state and territory population. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release

- Agarwal, P. K. (2023). Study of demographics, clinical profile and risk factors of inguinal hernia: A public health problem in elderly males. Cureus, 15(4), e38053. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38053

- AhmedAlenazi, A., Alsharif, M. M., Hussain, M. A., Alenezi, N. G., Alenazi, A. A., Almadani, S. A., Alanazi, N. H., Alshammari, J. H., Altimyat, A. O., & Alanazi, T. H. (2017). Prevalence, risk factors and character of abdominal hernia in Arar City, Northern Saudi Arabia in 2017. Electron Physician, 9(7), 4806–4811. https://doi.org/10.19082/4806

- AIHW. (2022/2023). Procedures data cubes, national hospital morbidity database. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/procedures-data-cubes/contents/data-cubes

- AIHW. (2023). Older Australians. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians

- Andresen, K., Bisgaard, T., Kehlet, H., Wara, P., & Rosenberg, J. (2014). Reoperation rates for laparoscopic vs open repair of femoral hernias in Denmark: A nationwide analysis. JAMA Surgery, 149(8), 853–857. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.177

- Birindelli, A., Sartelli, M., DiSaverio, S., Coccolini, F., Ansaloni, L., van Ramshorst, G. H., Campanelli, G., Khokha, V., Moore, E. E., Peitzman, A., Velmahos, G., Moore, F. A., Leppaniemi, A., Burlew, C. C., Biffl, W. L., Koike, K., Kluger, Y., Fraga, G. P., Ordonez, C. A. … Catena, F. (2017). 2017 update of the WSES guidelines for emergency repair of complicated abdominal wall hernias. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 12(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-017-0149-y

- Blonk, L., Civil, Y. A., Kaufmann, R., Ket, J. C. F., & van der Velde, S. (2019). A systematic review on surgical treatment of primary epigastric hernias. Hernia, 23(5), 847–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-02017-4

- Bradley, M. J., & Cosgrove, D. O. (2011). Chapter 41 - the abdominal wall, peritoneum and retroperitoneum. In P. L. Allan, G. M. Baxter, & M. J. Weston (Eds.), Clinical ultrasound (3rd ed. pp. 798–827). Churchill Livingstone. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-3131-1.00041-9

- Burcharth, J., Pedersen, M., Bisgaard, T., Pedersen, C., Rosenberg, J., & Burney, R. E. (2013). Nationwide prevalence of groin hernia repair. Public Library of Science ONE, 8(1), e54367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054367

- Burcharth, J., Pedersen, M. S., Pommergaard, H. C., Bisgaard, T., Pedersen, C. B., & Rosenberg, J. (2015). The prevalence of umbilical and epigastric hernia repair: A nationwide epidemiologic study. Hernia, 19(5), 815–819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-015-1376-3

- Caglià, P., Tracia, A., Borzì, L., Amodeo, L., Tracia, L., Veroux, M., & Amodeo, C. (2014). Incisional hernia in the elderly: Risk factors and clinical considerations. International Journal of Surgery, 12, S164–S169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.357

- Cassie, S., Okrainec, A., Saleh, F., Quereshy, F. S., & Jackson, T. D. (2014). Laparoscopic versus open elective repair of primary umbilical hernias: Short-term outcomes from the American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program. Surgical Endoscopy, 28(3), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3252-5

- Diaz, T., Strong, K. L., Cao, B., Guthold, R., Moran, A. C., Moller, A.-B., Requejo, J., Sadana, R., Thiyagarajan, J. A., Adebayo, E., Akwara, E., Amouzou, A., Aponte Varon, J. J., Azzopardi, P. S., Boschi-Pinto, C., Carvajal, L., Chandra-Mouli, V., Crofts, S., Dastgiri, S. … Banerjee, A. (2021). A call for standardised age-disaggregated health data. Lancet Healthy Longevity, 2(7), e436–e443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00115-X

- Fitzgibbons, R. J., Giobbie-Hurder, A., Gibbs, J. O., Dunlop, D. D., Reda, D. J., McCarthy, M., Neumayer, L. A., Barkun, J. S. T., Hoehn, J. L., Murphy, J. T., Sarosi, G. A., Syme, W. C., Thompson, J. S., Wang, J., & Jonasson, O. (2006). Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic mena randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 295(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.3.285

- Flum, D. R., Horvath, K., & Koepsell, T. (2003). Have outcomes of incisional hernia repair improved with time? A population-based analysis. Annals of Surgery, 237(1), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200301000-00018

- Gebremedhin, L. T. (2022). Investment in health data can drive economic growth. Nature Medicine, 28(10), 2000–2000. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02022-8

- Gillies, M., Anthony, L., Al-Roubaie, A., Rockliff, A., & Phong, J. (2023). Trends in incisional and ventral hernia repair: A population analysis from 2001 to 2021. Cureus, 15(3), e35744. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35744

- Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M. (2002). Looking at the future of geriatric care in developing countries. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 57(3), M162–M167. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/57.3.M162

- Hamilton, J., Kushner, B., Holden, S., & Holden, T. (2021). Age-related risk factors in ventral hernia repairs: A review and call to action. Journal of Surgical Research, 266, 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.04.004

- Helgstrand, F., Jørgensen, L. N., Rosenberg, J., Kehlet, H., & Bisgaard, T. (2013). Nationwide prospective study on readmission after umbilical or epigastric hernia repair. Hernia, 17(4), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-013-1120-9

- Henriksen, N. A., Montgomery, A., Kaufmann, R., Berrevoet, F., East, B., Fischer, J., Hope, W., Klassen, D., Lorenz, R., Renard, Y., Garcia Urena, M. A., Simons, M. P., On Behalf of the, E., & Americas Hernia, S. (2020). Guidelines for treatment of umbilical and epigastric hernias from the European Hernia Society and Americas Hernia Society. British Journal of Surgery, 107(3), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11489

- The HerniaSurge Group. (2018). International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia, 22(1), 1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x

- Hoffmann, H., Mechera, R., Nowakowski, D., Adolf, D., Kirchhoff, P., Riediger, H., & Köckerling, F. (2023). Gender differences in epigastric hernia repair: A propensity score matching analysis of 15,925 patients from the herniamed registry. Hernia, 27(4), 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02799-8

- Itatsu, K., Yokoyama, Y., Sugawara, G., Kubota, H., Tojima, Y., Kurumiya, Y., Kono, H., Yamamoto, H., Ando, M., & Nagino, M. (2014). Incidence of and risk factors for incisional hernia after abdominal surgery. British Journal of Surgery, 101(11), 1439–1447. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9600

- Kalyan, M., Rathore, S. S., Verma, V., Sharma, S., Choudhary, M., Irshad, I., & Gupta, P. (2022). Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repair: Experience at a tertiary care center in Western Rajasthan. Cureus, 14(7), e27279. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27279

- Kingsnorth, A., & LeBlanc, K. (2003). Hernias: Inguinal and incisional. The Lancet, 362(9395), 1561–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14746-0

- Koscielny, A., Widenmayer, S., May, T., Kalff, J., & Lingohr, P. (2018). Comparison of biological and alloplastic meshes in ventral incisional hernia repair. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery, 403(2), 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-017-1639-9

- Koumamba, A. P., Bisvigou, U. J., Ngoungou, E. B., & Diallo, G. (2021). Health information systems in developing countries: Case of African countries. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 21(1), 232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-021-01597-5

- Le Huu Nho, R., Mege, D., Ouaïssi, M., Sielezneff, I., & Sastre, B. (2012). Incidence and prevention of ventral incisional hernia. Journal of Visceral Surgery, 149(5, Supplement), e3–e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.05.004

- Lockhorst, E. W., van der Slegt, J., Veen, E. J., & Vos, D. I. (2020). Femoral hernias occur in both genders. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports, 63, 101671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2020.101671

- Malangoni, M. A., & Rosen, M. J. (2004). Hernias. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 201219, 1114–1140.

- Muysoms, F. E., Miserez, M., Berrevoet, F., Campanelli, G., Champault, G. G., Chelala, E., Dietz, U. A., Eker, H. H., El Nakadi, I., Hauters, P., Hidalgo Pascual, M., Hoeferlin, A., Klinge, U., Montgomery, A., Simmermacher, R. K., Simons, M. P., Smietański, M., Sommeling, C., Tollens, T. … Kingsnorth, A. (2009). Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia, 13(4), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-009-0518-x

- Nilsson, H., Angerås, U., Sandblom, G., & Nordin, P. (2016). Serious adverse events within 30 days of groin hernia surgery. Hernia, 20(3), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-016-1476-8

- Ortega-Deballon, P., Renard, Y., de Launay, J., Lafon, T., Roset, Q., & Passot, G. (2023). Incidence, risk factors, and burden of incisional hernia repair after abdominal surgery in France: A nationwide study. Hernia, 27(4), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-023-02825-9

- Pandya, B., Huda, T., Gupta, D., Mehra, B., & Narang, R. (2021). Abdominal wall hernias: An epidemiological profile and surgical experience from a rural medical college in central India. The Surgery Journal, 7(1), e41–e46. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1722744

- Perez, A. J., & Campbell, S. (2022). Inguinal hernia repair in older persons. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(4), 563–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2022.02.008

- Perez-Panades, J., Botella-Rocamora, P., & Martinez-Beneito, M. A. (2020). Beyond standardized mortality ratios; some uses of smoothed age-specific mortality rates on small areas studies. International Journal of Health Geographics, 19(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-020-00251-z

- Peters, D. H., Garg, A., Bloom, G., Walker, D. G., Brieger, W. R., & Hafizur Rahman, M. (2008). Poverty and access to health care in developing countries [10.1196/annals.1425.011]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.011

- Preston, S. H., & Stokes, A. (2012). Sources of population aging in more and less developed countries. Population and Development Review, 38(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00490.x

- Ruhl, C. E., & Everhart, J. E. (2007). Risk factors for inguinal hernia among adults in the US population. American Journal of Epidemiology, 165(10), 1154–1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm011

- Rutkow, I. M. (2003). Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surgical Clinics of North America, 83(5), 1045–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4

- Schlosser, K. A., Maloney, S. R., Thielan, O., Prasad, T., Kercher, K., Colavita, P. D., Heniford, B. T., & Augenstein, V. A. (2020). Outcomes specific to patient sex after open ventral hernia repair. Surgery, 167(3), 614–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.11.016

- Seker, G., Kulacoglu, H., Öztuna, D., Topgül, K., Akyol, C., Çakmak, A., Karateke, F., Özdoğan, M., Ersoy, E., Gürer, A., Zerbaliyev, E., Seker, D., Yorgancı, K., Pergel, A., Aydın, I., Ensari, C., Bilecik, T., Kahraman, İ., Reis, E. … Terzi, C. (2014). Changes in the frequencies of abdominal wall hernias and the preferences for their repair: A multicenter national study from Turkey. International Surgery Journal, 99(5), 534–542. https://doi.org/10.9738/intsurg-d-14-00063.1

- Turaga, K. K., Garg, N., Coeling, M., Smith, K., Amirlak, B., Jaszczak, N., Elliott, B., Manion, J., & Filipi, C. (2006). Inguinal hernia repair in a developing country. Hernia, 10(4), 294–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-006-0111-5

- Williams, M. L., Hutchinson, A. G., Oh, D. D., & Young, C. J. (2020). Trends in Australian inguinal hernia repair rates: A 15-year population study. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 90(11), 2242–2247. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16192

- Zhang, L. (2015). Incidence of abdominal incisional hernia in developing country: A retrospective cohort study. Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 8(8), 13649–13652.