ABSTRACT

Environmental health professionals play a significant role in preventing and addressing public health problems. Improving this area of practice continues to be a key strategy of the Australian Government; however, achieving this outcome presents several challenges. These challenges relate to the changing context of the practice and the complexities inherent in the practice itself. To address this problem, we investigated the qualitatively different ways environmental health professionals experienced their practice in Australia to establish a new conceptualization of practice. Phenomenographic qualitative methods underpinned this study, involving open-ended, semi-structured interviews with 19 environmental health professionals from diverse backgrounds and practice settings. The study revealed four qualitatively different ways of experiencing the professional practice of environmental health: ‘protecting’, ‘helping’, ‘collaborating’, and ‘leading and innovating’. These different ways were logically linked by five themes of expanding awareness to form a Holistic Experiential Description of Practice (HEDP), representing a new and novel conceptualization of the professional practice of environmental health. We propose that these findings provide a more useful way to conceptualize this area of practice than the current descriptions allow.

Introduction

Environmental health professionals (EHPs) are vital members of the public health workforce. Their origins stem from the sanitation movement founded in Britain in the mid-19th century, involving the introduction of Public Health Acts and the development of the sanitary profession to administer these Acts (Aston & Seymour, Citation1998; Bell, Citation2002). This also involved professional associations developing codes of conduct and adopting an accreditation role to certify training for the sanitary role (Brimblecombe, Citation2003). In today’s context, this group is now more commonly referred to as the environmental health profession, representing environmental health officers, or practitioners. In many countries, EHPs perform various functions. In Australia, this includes investigating incidents associated with food, water, air, noise, and land contamination; compliance visits subject to public and environmental health legislative control; and involvement in health promotion, community education, disaster management, research, and strategic policies related to this practice area (Dunn et al., Citation2018; Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009). Additionally, given this broad scope of practice, environmental health professionals may be employed in various capacities in both the private and public sector, for example, as a public health, environmental protection or food safety officer or in disaster or waste management, research, academic or in environmental health managerial positions. Thus, in this study, an environmental health professional refers to a person who has gained professional recognition to practice environmental health, involving the completion of a professionally accredited training program. In Australia, Environmental Health Australia (EHA) is the accrediting body for environmental health education programs (Environmental Health Australia, Citation2014).

Supporting improvements to environmental health practice continues to be a key strategy of the Australian Government to ensure this workforce is well-equipped to deal with current and future challenges (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Citation1999; Environmental Health Standing Committee enHealth, Citation2020). Ensuring ongoing improvements to professional practice is also a societal expectation in the context of ensuring competence as a defining characteristic of a profession and essential for any professional field to maintain its legitimacy and sustainability (Higgs et al., Citation2019). However, gaining improvements in this area of practice presents several challenges. These challenges, we contend, relate to the complexities associated with the changing and evolving context of practice and the complexities inherent in the practice itself. To address these challenges, this research asked (1) What are the qualitatively different ways environmental health professionals experience their practice, and (2) what are the critical variations between these different ways of experiencing?

Through in-depth phenomenographic analysis of EHP experiences, we developed a novel Holistic Experiential Description of Practice (HEDP). We propose that the HEDP can help improve the professional practice of environmental health by enabling environmental health professionals, educators, and society to develop a more complete or comprehensive understanding of this practice area. In the following sections, we further explore the complexities associated with the professional practice of environmental health before introducing variation theory and the phenomenographic approach taken to establish the HEDP. This is followed by the presentation and discussion of the research findings.

Complexities associated with the changing and evolving nature of practice

The complexities associated with the changing and evolving context of practice, posing challenges for the environmental health profession, relate to the evolving nature of environmental health problems, such as the resurgence of infectious diseases associated with population growth, globalization, and climate change (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Citation1999; Frumkin, Citation2020). It also relates to changes in environmental health regulatory and operational environments; for example, a greater emphasis on target setting aligned with achieving regulatory-based responsibilities in statutorily based settings (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009) and a range of workforce issues. These workforce issues, experienced in many countries globally, include the recruitment and retention of environmental health professionals, often attributed to poor visibility and lack of societal understanding, valuing, and recognition of the environmental health professional role (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009; Treser, Citation2018; Whiley et al., Citation2019), the viability of tertiary programs aimed at professionally qualifying environmental health professionals, and graduate work readiness (Dunn et al., Citation2018; Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009). These problems also have flow-on effects on environmental health professionals’ ability to address future societal needs (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Citation1999; Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009). This includes adopting more strategic and holistic approaches to dealing with environmental health problems by the practice community beyond those based on regulatory control. For example, the ability to address health inequalities and climate change and have a voice in the broader public health policy agenda (Dhesi & Stewart, Citation2015; Smith et al., Citation2021).

In addition, the crisis in confidence in the professions associated with the erosion of the institutional trust society has placed in these occupational groups to address societal needs in altruistic, competent, and moralistic ways (Allsop, Citation2006), we contend, also poses further complexities for the environmental health profession. This crisis is associated with factors such as globalization and the adoption of a neoliberal agenda by governments (Mayes et al., Citation2016,) within a societal context increasingly framed by supercomplexity (Barnett, Citation2000), wicked problems (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973), liquid times (Trede & Higgs, Citation2019) and an increased societal perception of the political influence on science (Edelman, Citation2024). These factors have also strained many aspects of the traditional conceptualization of a profession, raising questions regarding the future societal role of the professions and professional practice. For example, when considering the environmental health professions’ claim as a source of exclusive skills and knowledge as a defining characteristic of a profession, there is broad recognition that ‘no single set of experts can generate effective solutions to environmental health problems’ (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009, p. 30), posing a challenge to this claim.

Complexities inherent in the practice itself

The complexities inherent in the practice itself relate to how the phenomenon of practice is conceptualized, particularly as a basis for developing and maintaining professional expertise. In many countries, including Australia, education for professional practice often assumes a container view of practice, an approach criticized for promoting decontextualized, fragmented, individualistic, and stepwise approaches to professional development, ignoring the relational, contextual, emergent, and social nature of professional practice (Boud, Citation2012; Dall’alba & Sandberg, Citation2006). This approach not only has implications for the ability of practitioners to deal with ‘the swampy lowlands, where situations are confusing messes incapable of technical solution and usually involve problems of greatest human concern’ (Schön, Citation1983, p. 42), the sorts of situations that are becoming central to the person and professional practice (Cherry, Citation2005) but overlooks the variation in the ways practitioners may experience or understand their practice. Overlooking this variation fails to recognize that the way a practitioner experiences their practice is central to how they perform and develop their practice (Dall’alba & Sandberg, Citation2006). This, in turn, can have implications for a practitioner’s ability to deal with increasingly complex, varying, and uncertain situations (Billett, Citation2004).

To better prepare practitioners for the complexities of practice, we propose that an alternate model for professional development is required, that involves establishing an understanding of the different ways practitioners experience their practice. In this model, the aim is to progressively develop both the different ways of understanding or experiencing practice together with the skills required to operate within these different ways of understanding, as a form of unfolding, ‘professional way- of- being’ (Dall’alba & Sandberg, Citation2006, p. 380). This notion of understanding practice integrates knowing, acting, and being the professional.

Thus, we argue that the above complexities pose critical challenges for improving the professional practice of environmental health and indicate that current descriptions of practice are inadequate to deal with the complexities and uncertainties associated with current and future practice. To address this problem, this empirical study, completed as part of a PhD (Dunn, Citation2021) establishes a new conceptualization of the professional practice of environmental health involving the development of the HEDP. The development of the HEDP was guided by variation theory (Åkerlind, Citation2018; Bussey et al., Citation2013).

Variation theory

Variation theory has stemmed from the empirical research approach known as phenomenography (Bussey et al., Citation2013). Variation theory explains how people experience and understand phenomena in a limited number of qualitatively different but interrelated ways, which may also result in a phenomenon such as practice being enacted in varying ways by both individuals and groups (Åkerlind, Citation2018; Marton & Booth, Citation1997).

The key assumption underpinning variation theory is that when we reflect on an experience of an aspect in the world, because of our cognitive abilities, there are only a limited number of these aspects or features we can hold in our awareness at any one time (Marton & Booth, Citation1997). The combination of these aspects we focus on when we recall this experience becomes critical to how we understand this aspect of the world. For example, two people may reflect on an aspect of the same experience. Owing to their previous experiences, individual backgrounds, the context of the experience, and the combination of features they focus on at that time, they may come to understand or experience that aspect differently (Marton & Booth, Citation1997).

Furthermore, identifying these different ways of experiencing and the critical variations between these different ways provides insight into how these different ways are linked together to form an outcome space (Åkerlind, Citation2005). Critical variations refer to critical features or aspects that vary between different ways of experience. They are the key variants that help describe the shift in focus of awareness from one way of experiencing to another, contributing to the qualitatively different ways of experiencing a phenomenon. Critical features or aspects may also form themes of expanding awareness. This refers to aspects of awareness that may be present in each category but expand or become deeper than in previous categories, providing insight into how these different experiences relate to each other to form a comprehensive or complete way of experiencing a phenomenon (Åkerlind, Citation2005). Comprehensive refers to an expansion and deeper level of awareness of the elements or aspects of practice than previous categories, rather than a better way of experiencing practice (Åkerlind, Citation2005). The different ways of experiencing are represented as categories of description, with the outcome space being a holistic representation of a limited number of qualitatively different ways of experiencing the object of study at any point in time for the population represented by the sample group (Åkerlind, Citation2005).

To establish the HEDP, an exploratory descriptive research design, analyzed through interpretative phenomenographic qualitative methods, was adopted. We have further detailed the methods used in this study.

Methods

Phenomenographic methods were selected for the study, as they aim to uncover the qualitatively different ways of experiencing and the critical variations between these different ways of experiencing the phenomenon of interest (Åkerlind, Citation2005).

Phenomenography adopts a nondualist relational view (Yates et al., Citation2012). Thus, knowledge is constituted through a person’s interaction with a phenomenon. This is important, as the focus in phenomenographic research is on gaining insight into a person’s lived experience, rather than a subjective view, of what they think a phenomenon should be, to achieve a description of practice that represents the phenomenon of interest as experienced (Yates et al., Citation2012).

Participant selection & recruitment

A purposeful sampling strategy involving the administration of an online survey based on a range of diversity criteria (e.g. age, gender, country of birth, and current employment status) was used to maximize variation in practice experience among the participants (Åkerlind, Citation2005; Bowden, Citation2000) and enhance the usefulness and transferability of the findings to other contexts (Åkerlind, Citation2012). The online survey also aimed to support the reliability of the findings by addressing the issues associated with the researcher’s interpretative awareness. Interpretative awareness refers to the researcher acknowledging and explicitly dealing with his or her preconceptions throughout the research process (Sin, Citation2010). For example, for resource and practical reasons, the recruitment and selection of practitioners for the study was confined to those currently practicing in Victoria, Australia, resulting in a potential pool of 350 eligible practitioners. Because one of the researchers was a qualified environmental health practitioner, many practitioners were known to her. The online screening survey enabled the names of the respondents to be kept separate from the selection process to avoid selection of participants based on any preconceived ideas about the nature of participants’ experiences (Sin, Citation2010).

In total, 109 responses to the online survey were received. Guided by the literature related to data management and the potential saturation point regarding discerning aspects of variation in the data (Åkerlind, Citation2005), an initial pool of 22 participants was selected. Data saturation refers to the point in qualitative research at which no new information is elicited. After the 19th interview, data saturation was reached, resulting in a final sample size of 19 participants. The sample included four practitioners practicing in a State Government setting, eight in a Metropolitan Local Government setting, one in a university setting, five in Rural and Regional Local Government settings, and two who identified as practicing in a range of settings due to their role as either a private contractor or consultant. Appendix 1 provides a description of the participants’ characteristics in the order in which they were interviewed.

Data collection

Data collection took place over a 12-month period, concluding in November 2015, and involved face-to-face semi-structured interviews and the use of an interview schedule (Åkerlind, Citation2005; Yates et al., Citation2012). The schedule consisted of a core series of questions to encourage reflection by the participant on the phenomenon and provide a basis to ask further questions. For example, initial questions included, ‘Can you tell me about a recent experience that you have had in environmental health?’ followed by ‘Can you tell me more about what you did in that activity?’ and ‘You mentioned xx, can you explain further what you mean by that?’ The interview questions were designed to enable the exploration of meanings associated with how the participants experienced their practice, while also creating a dialogue to assist in communicative validity (Ashworth & Lucas, Citation2000). All the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Two pilot interviews were conducted to check the interview format and questions; however, these interviews were not included in the analysis. The interviews lasted from 54 to 77 minutes.

Data analysis

The methods adopted for the phenomenographic analysis were based on the methods proposed by Bowden (Citation2000) and Åkerlind (Citation2005) and involved six phases. First, the transcripts were checked against the audio file and de-identified. Second, two researchers tentatively grouped the transcripts based on an initial impression of what practice was for each participant. In the third phase, the initial transcript groupings were set aside. All transcripts were input into NVivo 12, where one researcher made notes on how each participant described their practice, including what they did, how they did it, for what purpose (or motivation), and what practice was about for them, highlighting quotes to support these aspects. This process served as a form of interpretative awareness (Sin, Citation2010) by ensuring that the analysis is grounded in the practitioner’s experiences rather than the researcher’s experience.

The fourth phase of the analysis involved revisiting the groupings from phase two to refine them further based on the similarities and differences in the way practitioners described their practice identified in phase three. This process resulted in the grouping of transcripts into four initial categories of description, the drafting of a sentence describing the overall meaning for each category and the selection of a representative quote from the transcripts to support these meanings. Phase five used the sentences from the newly formed categories of description and the transcripts grouped into each of these categories to further compare similarities and differences with respect to the way practitioners described their practice within these categories. During this iterative process, the categories were further refined and detailed descriptions of the meanings associated with each category were formed.

The sixth and final analysis phase focused on interpreting the critical variations between the different ways in which the practice was experienced. This included identifying the dimensions of variation or themes of expanding awareness, linking and separating the categories, helping to establish the logical relationship between the categories, or how the categories fit together to form the HEDP based on evidence from the transcripts.

The project was approved by the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee (SUHREC) Project-2014/108. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to the commencement of the study.

Results

The results are presented in two sections, one for each research question.

Ways of experiencing the practice of environmental health

The analysis revealed four qualitatively different ways the professional practice of environmental health was experienced by the practitioners. These different ways of experiencing are represented as four categories of description: ‘protecting’, ‘helping’, ‘collaborating’, and ‘leading and innovating’. These four variations address the first research question: What are the qualitatively different ways EHPs experience their professional practice? provides a short description of these categories.

Table 1. Short description of the four categories of description.

The following section briefly extends the description of each of the four categories in .

Protecting

Environmental health practice is protecting people to prevent harm within given boundaries and experienced as the fundamental purpose of practice. Without this protection and prevention from harm, the health and well-being of the community is seen to be at risk. The given boundaries are experienced by practitioners as the boundaries which practice must function within. These boundaries are influenced by the legislative framework, organizational policies underpinned by a practitioners professional training. Paul captures the key focus of this category:

For me it’s basic, keep it basic. We’ve been trained on the basics of what needs to be done as far as food science is concerned. We’ve been trained on the basics of what needs to be done as far as waste, liquid waste, septic tanks are concerned. We should know how to handle nuisance complaints. It’s about – and from the council perspective, it’s about serving the needs of the ratepayers … So, it’s in a council, in local Government, it’s just about using your delegated authority under the various acts and regulations to monitor, administer and to control what you can within your powers. (Paul, p. 10)

Helping

Environmental health practice is helping stakeholders to create a sustainable healthy community by changing boundaries. This was experienced as a key approach to practice. Changing boundaries reflects a practitioner’s focus on changing and adapting practice, particularly to deal with the non-black and white nature of practice whilst not compromising the core statutory responsibilities or boundaries of practice as a practitioner. Carmel captures the focus of this category:

So, for me, environmental health practice is about, I’m trying to think how I can word this because I tend to go like that. But fundamentally for me it’s about having a healthy community, so I look at it from that aspect in terms of what we do and the benefits the community gain from that … What we do effectively creates a healthy community in a number of ways, shapes and forms. So, yeah, I probably look at it in a bit different light than some others, but yeah, that’s just how I’ve seen it. (Carmel, p. 15)

Collaborating

Environmental health practice is collaborating with partners to achieve optimal health outcomes for the community by connecting boundaries and is experienced as an important process. Connecting boundaries reflects an understanding by practitioners that in order to achieve optimal health outcomes, people or organizations connected to the problem and the solution need to be engaged in a collaborative process in order to achieve this goal. Ted captures the focus of this category:

The nature of our work needs a number of skills or typically, we’re looking at risk in environmental health. In my area, there’s engineering issues so there’s asset and infrastructure issues. There’s microbiological issues. There’s toxicology issues. There’s the continuum of public health from legislative administration through to health promotion to achieve the behaviour change you might want to achieve. It’s complex. It’s multidiscipline. The more people sitting around identifying issues and opportunities or different ways to address things, you just get a better outcome. (Ted, p. 5)

Leading and innovating

Environmental Health practice is leading communities and innovating practice to create our future without boundaries. Leading is experienced as an important action of practice and innovating is experienced as a process and an outcome of leading. Both aspects are perceived to have benefits for the practice of environmental health and our future. Without boundaries reflects an understanding by practitioners that there are no boundaries to the practice of environmental health. Colin captures the focus of this category:

So what I like to try and do is put ourselves up there in lights and say we’re innovative, we’re bringing in new ways of doing things, we’re leaders in what we do, not just within environmental health and City of [organization], I mean environmental health in the broader scheme of local Government that we’re … willing to and we’re leaders within local Government, more so than planning or building or recreation. We are setting a standard in terms of how local Government should operate as a department. So for me it’s a broader aspect and it’s something that I sort of want to try to do, to say ‘yeah, environmental health officers are pretty good, they’re pretty innovative, they’re pretty forward thinking about approaches to how they manage their work’. (Colin, p. 7)

Critical variations between the different ways of experiencing

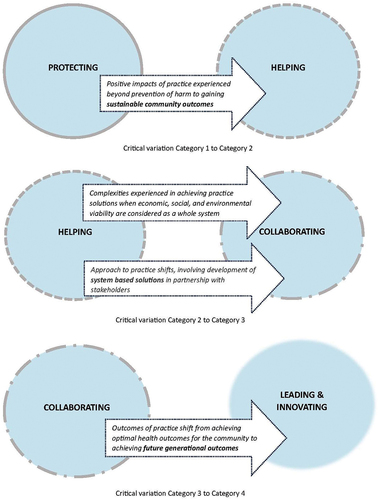

The study revealed three critical variations between the different ways practice was experienced. These were the variations from Category 1 (protecting) to Category 2 (helping), Category 2 (helping) to Category 3 (collaborating), and Category 3(collaborating) to Category 4 (leading and innovating). The critical variations describes how the focus of awareness shifts from one category to the next. These variations provide evidence to support why four categories of description were found in the study and how the categories fit together to form an HEDP.

Five themes of expanding awareness were identified, ‘outcome of practice’ (outcome), ‘those impacted by practice’ (impact), ‘the approach to practice’ (approach), ‘agency’ (agency) and ‘the role of practitioner’ (role). These themes ran through each category of description but expanded to encompass a deeper level of awareness than the previous categories, supporting the logical relationship between the categories, which was hierarchical. Thus, Category 1 (protecting) was the least comprehensive, and Category 4 (leading and innovating) was the most comprehensive way of experiencing the practice of environmental health. The three critical variations between each category are described by the phrases ‘sustainable community outcomes’, ‘system-based solutions’, and ‘future generational outcomes’. provides a succinct description of the three critical variations identified in this study.

Table 2. Succinct description of the critical variation between the four categories of description.

The following extends the description of the critical variations between the four categories described in .

Category 1 (protecting) to category 2 (helping)

The key variation between Category 1 (protecting) and Category 2 (helping) is a shift in focus from only experiencing practice as fundamentally protecting from harm to experiencing practice as creating a sustainable healthy community. This shift in focus is still inclusive of a practitioner’s awareness that the fundamental outcome of practice is to protect from harm, but varies as practitioners experience the positive outcomes practice can have on the community’s economic, social, and environmental sustainability. This shift indicates a broadening of awareness of the outcomes of practice from the former category, as practice is experienced as preventing the negative consequences associated with the prevention of harm and as having a wider benefit for the community. This shift is captured by Trisha:

… ultimately to help the community because if you get a negative interaction quite a lot it can be difficult, but I find it hugely satisfying then when you do provide someone with some education that changes a practice within their business for the better or you gain compliance from a business that’s been non-compliant for quite some time, and to think that even though you may not see any feedback from the community because they haven’t even been aware that that was the issue. But just I think - just to be mindful of the fact that ultimately people want to come into the municipality you’re in, to their home and their area and feel like they can go and eat and relax and that everything’s safe there. Ultimately, it’s satisfaction of the community. (Trisha, p10)

Category 2 (helping) to category 3 (collaborating)

The key variation from Category 2 (helping) to Category 3 (collaborating) is a shift from experiencing the positive outcomes that practice solutions can have on the economic, social, and environmental viability of the community to experiencing the complexities associated with achieving practice solutions when each of these factors (economic, social, and environmental viability of the community) are considered as a whole system. This shift indicates a broadening of awareness of the outcomes of practice from the former category, as achieving practice solutions in this category also requires a shift in the approach to practice. This shift is from a focus on modifying the required process to help stakeholders self-manage risks to developing an agreed upon process by collaborating in partnership with those impacted by problems or those considered to have the expertise to contribute solutions to hazards that impact human health and the environment. The approach involves creating a governance structure and an agreed-upon process that involves identifying those who have a role in developing solutions. This shift is captured by Ted:

Well from day one when it was identified that there might be a species of algae in the lakes that released toxins, probably two years before we ever had to intervene, from day one we did what I explained before with the way we project manage things. We put together a governance group which were Executive Directors of [Industry Group), Department of [Government] and Department of [Government]. We’ve got a problem; we need an authorizing environment to investigate what the solution is. Put together a project team to investigate it which included representative of the (impacted industry). Regional representatives from [organization], us, [organization] etc., food people. (Ted, p. 11)

Category 3 (collaborating) to category 4 (leading and innovating)

The key variation from Category 3 (collaborating) to Category 4 (leading and innovating) is a shift in focus from achieving ‘optimal health outcomes’ in Category 3 to ‘create our future’ in Category 4. This shift varies as practitioners focus on sustaining the future of the practice of environmental health through leading communities and innovating practice. To create our future indicates a broadening of awareness of the outcome of practice, as the outcomes now extend to ensuring that practice can continue to respond to the challenges posed by an evolving world to ensure the future health of generations. This shift is described by Martin:

So that’s where for me I personally believe it’s really important that we’re responsible for creating our future, you know, the next generation we need to be leading them to show them how to actually get good outcomes, how to be empowered to make changes. (Martin, p. 11)

The findings of this study are shown in .

Figure 2. The professional practice of environmental health as a holistic experiential description of practice (HEDP).

succinctly depicts the critical variation between the four different ways practice was experienced by the practitioners interviewed for the study. These key variants help describe the shift in focus of awareness from one way of experiencing to another. For example, as illustrates, experiencing the positive impacts of practice beyond prevention from harm to gaining sustainable community outcomes shifts the focus from experiencing practice as ‘protecting’ Category 1 to experiencing practice as ‘helping’ Category 2. Thus, the key variants between the categories help account for the four qualitatively different ways the professional practice of environmental health was experienced in this study.

succinctly depicts the four qualitatively different ways environmental health practice was experienced by the practitioners interviewed in this study and how they relate to form the HEDP, representing the outcome space. These four different ways represent the referential or meaning aspect of practice: the focus or ‘what’ practice is collectively about for participants in this study. As illustrates, Category 1, ‘protecting’, is at the core of this diagram, as this is experienced as the fundamental purpose of the professional practice of environmental health. Moving from Category 1 to 4, each category encompasses the previous category, which is logically linked from less to more comprehensive ways of experiencing the professional practice of environmental health. Five themes of expanding awareness were identified, which helped to support and describe this relationship: ‘outcome’ (outcome of practice), ‘impact’ (those impacted by practice), ‘approach’ (approach to practice), ‘agency’ (the agency of the practitioner), ‘role’ (role of the practitioner). This hierarchy represents the structural relationship between the categories or ‘how’ they fit together to form the whole.

Discussion

The study’s findings have generated an HEDP by investigating the qualitatively different ways in which 19 environmental health professionals in an Australian context experience their practice. This new and novel way of describing the professional practice of environmental health provides a useful way to conceptualize this area of practice by empirically establishing a detailed description of practice generated from practitioners’ own lived experiences of practice. This approach departs from current descriptions of practice, which are often fragmented and decontextualized, such as those focusing on describing the types of knowledge and skills required to practice as the basis for professional development. The advantage of generating a description of practice based on these characteristics is that it not only provides insight into the realities of practice as experienced, but also provides qualitatively and distinctly different insights into ‘how’ practitioners enact their practice and ‘what’ practice was about for each respective category of description. This has linked how practitioners practice with what they understand their practice to be. This includes recognizing that practitioners may understand and enact the same practice in qualitatively different ways, thus resulting in different outcomes (Marton & Booth, Citation1997).

In addition, by revealing the variation in the different ways practitioners experience their practice and the critical variations between these different ways of experiencing, the findings show how these different experiences are logically and structurally related to form an HEDP. In this study, the relationship was hierarchical, with ‘protecting’ the least comprehensive category and ‘leading and innovating’ the most comprehensive way of experiencing practice. This relationship provides a map of professional becoming by providing insight into how to develop more professional ways of being in this field. The critical variations linking the categories provide insight into how the focus of awareness shifts across the categories of description, namely Category 1 to 2 (protecting to helping), Category 2 to 3 (helping to collaborating) and Category 3 to 4 (collaborating to leading and innovating). In contrast, the themes of expanding awareness illustrate critical features or aspects within practice that evolve through the process of becoming, namely, the ‘outcome’, ‘impact’ the ‘approach’, ‘agency’ and ‘role’. A description of practice from the perspective adopted in this study is currently absent from the literature.

The findings of this study have the potential to act as a framework for improving the professional practice of environmental health and education for professional practice while helping to address the challenges associated with the complex and interrelated relationship between society, the environmental health profession, and education. We further explore this claim.

Societal

At the societal level, the diagram in provides a practical tool that could be disseminated among the broad community by the profession or other relevant stakeholders to improve societal awareness and understanding of what the practice of environmental health is. This includes the societal benefits of this area of practice. This awareness is required to address the problems associated with poor visibility and lack of societal understanding and valuing of this practice area (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009; Whiley et al., Citation2019). Addressing these problems is important to help gain sufficient societal support and resources to assist in achieving improvements in this area of practice, such as the ability to attract sufficient resources to support evidence-based practice initiatives and enhance the relevance and ongoing viability of the profession. Ensuring the ongoing viability of the environmental health profession is important due to the critical role environmental health professionals have in responding to complex and multifaceted environmental health issues (Gerding et al., Citation2019) and the distribution of the environmental health professional workforce throughout many sectors of the community, with close ties to vulnerable groups (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009). These characteristics position the environmental health profession as an important group that can foster integrated partnerships and support holistic responses to complex environmental health problems. These characteristics are essential in a societal context where responding to such issues requires multidisciplinary, coordinated, and collaborative responses (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009). The study’s findings, particularly those associated with the ‘helping’ and ‘collaborating’ categories, also indicate that the profession is well positioned to assist in achieving these outcomes. For example, a key focus of the ‘collaborating’ category involved practitioners engaging in collaborative processes with people or organizations connected to the problem and solutions to achieve optimal health outcomes for the community.

Professional

At the professional level, the framework can help improve the professional practice of environmental health by addressing issues such as workforce retention by shifting the negative perceptions held by some practitioners concerning the narrow focus of this area of practice (Environmental Health Committee enHealth, Citation2009). For example, if a practitioner had only experienced practice as ‘protecting’, the framework could be used to explore how the different ways of experiencing practice could achieve more satisfying outcomes for the practitioner. This approach could also extend to the organizational level, where the framework could be applied to compare the categories of description with current job positions. For example, how current job positions reflect opportunities to provide environmental health services that ‘help create a sustainable community’, the focus of Category 2, or ‘lead and innovate practice’ to create our future, the focus of Category 4. In so doing, it opens opportunities for practitioners to enact practice in more comprehensive ways to assist in job attraction and retention and achieve better societal outcomes.

Educational

A key implication of the HEDP at the educational level for improving the professional practice of environmental health relates to improving education for professional practice for both students and currently practicing professionals. In particular, the HEDP provides the basis for an alternate model of professional development that shifts the focus from conceptualizing, developing, and maintaining expertise based on acquiring knowledge skills to developing professional ways of being (Dall’alba & Sandberg, Citation2006). This includes developing the ontological dimensions of practice to support who students and practitioners are becoming (Dall’alba, Citation2009). By developing students’ and practitioners’ embodied ways of experiencing the professional practice of environmental health, along with their skills and knowledge, to enact practice in qualitatively different ways, ‘professionals not only learn knowledge and skills, but these are renewed over time whilst becoming integrated into ways-of-being the professional in question’ (Dall’alba, Citation2009, p. 401). Thus, expert performance we conceive as developing more ‘professional ways of being’ enabling practitioners to deal with the complexities and uncertainties of practice more effectively.

Study limitations

The first limitation relates to the findings not being generalizable or considered as universal statements (Åkerlind, Citation2018). The applicability of these findings to other contexts is based on an assessment of similarities with the sample population used in this study. Second, the findings reflect the participants’ experiences at the time of the interview, with the interviews completed in 2015. If the same participants were interviewed at different times, their responses might have differed, which is an expectation of the phenomenographic research approach (Åkerlind, Citation2005). However, to increase the communicative validity of the findings and address these limitations, an online survey to recruit participants was used to maximize the variation in experiences to gain the most complete or comprehensive description of practice. Nonetheless, it is also acknowledged that not all participants eligible for the study responded to the online survey, which may have influenced the study outcomes. Despite these limitations, the presentation of the findings in various forums (Dunn, Citation2022, Citation2023) and informal feedback from the practice community indicated that the findings of the study resonate with the practitioner community, supporting the communicative validity of the results.

Future research

This exploratory study provides several avenues for future research. Further research should be undertaken to support the communicative validity of these findings, such as a more formal investigation into whether the HEDP resonates with the environmental health practice community. Additionally, research should be undertaken to examine the pragmatic validity of the findings to effect change at the societal, professional, and educational levels. For example, at the societal level, future research could focus on whether the HEDP has changed perceptions of the professional practice of environmental health among key stakeholders, such as government officials, and the implications of this change for improving practice.

Given that this investigation was based in an Australian setting, studies of this type could also be conducted among a group of environmental health professionals from other countries or specific regions within countries. Such an investigation could provide opportunities to reflect on similarities and differences between the different ways of experiencing practice among different settings and the implications of these different ways of experiencing for improving practice. It could also provide the opportunity to create a strong, unified identity among the environmental health profession.

More broadly, similar research could be undertaken among other professions. To date, whilst the phenomenographic research approach used in this study has been used to investigate a wide range of concepts and various aspects of practice (Hajar, Citation2021), to our knowledge, no other research exploring professional practice from the holistic standpoint we have adopted in this study has been undertaken more broadly among the professions. Gaining this view is important, as highlighted in this study, it provides the opportunity to develop a framework to help improve practice. It may also provide further opportunities to explore how to join these professional groups or communities of practice more effectively to help deal with the complexities and uncertainties associated with human interaction with the environment to improve societal outcomes. Doing so may also help restore societal trust in the professions to address societal needs in altruistic, competent, and moral ways.

Conclusion

This study addressed the lack of empirical qualitative research on environmental health professionals’ practice experience and established a holistic experiential description of practice (HEDP). We argue that this new conceptualization has the potential to assist environmental health professionals in effectively dealing with the complexities and uncertainties associated with human interaction with the environment, both now and in the future. This new conceptualization provides a new way forward for the environmental health profession and the professions more broadly. We also suggest that studies of this nature are essential in informing organizational and educational change to help improve professional practice and restore societal trust in the professions.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, L.D; L.M and K.F.; methodology, L.D.; LM; formal analysis, L.D; L.M.; writing – original draft preparation, L.D.; writing – review and editing, L.D, L.M and K.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for their time and sharing their experiences in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not provide written consent for their data to be shared publicly because of the sensitive nature of the research, so supporting data are not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åkerlind, G. (2005). Learning about phenomenography: Interviewing, data analysis and the qualitative research paradigm. InJ. A. Bowden & P. Green (Eds.), Doing developmental phenomenography (p. 63). RMIT University Press.

- Åkerlind, G. (2012). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.642845

- Åkerlind, G. S. (2018). What future for phenomenographic research? On continuity and development in the phenomenography and variation theory research tradition. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(6), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1324899

- Allsop, J. (2006). Medical dominance in a changing world: The UK case. Health Sociology Review, 15(5), 444–457. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2006.15.5.444

- Ashworth, P., & Lucas, U. (2000). Achieving empathy and engagement: A practical approach to the design, conduct and reporting of phenomenographic research. Studies in Higher Education, 25(3), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/713696153

- Aston, J., & Seymour, H. (1998). The new public health. Open University Press.

- Barnett, R. (2000). University knowledge in an age of supercomplexity. Higher Education, 40(4), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004159513741

- Bell, S. (2002). Environmental health: Victorian anachronism or dynamic discipline? Environmental Health, 2(4), 23.

- Billett, S. (2004). Learning through work: Workplace participatory practices. In A. Fuller, A. Munro, & H. Rainbird (Eds.), Workplace learning in context (pp. 125–141). Routledge.

- Boud, D. (2012). Problematizing practice-based education. In J. Higgs, S. Billett, M. Hutchings, & F. Trede (Eds.), Practice-based education (pp. 55–68). Brill Sense.

- Bowden, J. A. (2000). The nature of phenomenographic research. In J. A. Bowden & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 1–18). RMIT University Press.

- Brimblecombe, P. (2003). Historical perspectives on health: The emergence of the sanitary Inspector in Victorian Britain. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 123(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/146642400312300219

- Bussey, T. J., Orgill, M., & Crippen, K. J. (2013). Variation theory: A theory of learning and a useful theoretical framework for chemical education research. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 14(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2RP20145C

- Cherry, N. L. (2005). Preparing for practice in the age of complexity. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(4), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360500284649

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. (1999). The National environmental health strategy. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Dall’alba, G. (2009). Learning professional ways of being: Ambiguities of becoming. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 41(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00475.x

- Dall’alba, G., & Sandberg, J. (2006). Unveiling professional development: A critical review of stage models. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 383–412. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076003383

- Dhesi, S., & Stewart, J. (2015). The developing role of evidence-based environmental health: Perceptions, experiences, and understandings from the front line. Sage Open, 5(4), 2158244015611711. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015611711

- Dunn, L. (2021). Reconceptualizing the professional practice of environmental health. A framework for improving practice [ Doctoral thesis]. Swinburne University of Technology. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/463857

- Dunn, L. (2022). Improving the practice of environmental health. 45th EHA National Conference, Launceston, Tasmania.

- Dunn, L. (2023). A new holistic description of the practice (HEDP) of environmental health. Reimagining Environmental Health Australia National Symposium, Melbourne, Victoria.

- Dunn, L., Nicholson, R., Ross, K., Bricknell, L., Davies, B., Hannelly, T., & Roiko, A. (2018). Work-integrated learning and professional accreditation policies: An environmental health higher education perspective. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 19(2), 111–127.

- Edelman, D. (2024). 2024 Edelman trust barometer. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2024/trust-barometer

- Environmental Health Australia. (2014). Environmental health course accreditation policy. http://accreditation.eh.org.au/

- Environmental Health Committee (enHealth). (2009). enHealth Environmental health officer skills and knowledge matrix. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Environmental Health Standing Committee (enHealth). (2020). enHealth strategic plan 2020–2023. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-environ-enhealth-committee.htm.

- Frumkin, H. (2020). Climate change and human health. In S. Myers & H. Frumkin (Eds.), Planetary health: Protecting nature to protect ourselves (pp. 245–254). Island Press.

- Gerding, J. A., Landeen, E., Kelly, K. R., Whitehead, S., Dyjack, D. T., Sarisky, J., & Brooks, B. W. (2019). Uncovering environmental health: An initial assessment of the profession’s health department workforce and practice. Journal of Environmental Health, 81(10), 24–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6945822/

- Hajar, A. (2021). Theoretical foundations of phenomenography: A critical review. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(7), 1421–1436. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1833844

- Higgs, J., Cork, S., & Horsfall, D. (2019). Challenging future practice possibilities. Brill.

- Marton, F., & Booth, S. A. (1997). Learning and awareness. Routledge.

- Mayes, C., Kerridge, I., Habibi, R., & Lipworth, W. (2016). Conflicts of interest in neoliberal times: Perspectives of Australian medical students. Health Sociology Review, 25(3), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2016.1198713

- Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Sin, S. (2010). Considerations of quality in phenomenographic research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(4), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691000900401

- Smith, J. C., Whiley, H., & Ross, K. E. (2021). The new environmental health in Australia: Failure to launch? International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 18(4), 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041402

- Trede, F., & Higgs, J. (2019). Collaborative decision-making in liquid times. In J. Higgs, S. Jensen, N. Loftus, & N. Christensen (Eds.), Clinical reasoning in the health professions (4 ed. pp. 154). Elsevier.

- Treser, C. D. (2018). Environmental health: The invisible profession. Journal of Environmental Health, 81(5), 34–36.

- Whiley, H., Willis, E., Smith, J., & Ross, K. (2019). Environmental health in Australia: Overlooked and underrated. Journal of Public Health, 41(3), 470–475. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy156

- Yates, C., Partridge, H., & Bruce, C. (2012). Exploring information experiences through phenomenography. Library and Information Research, 36(112), 96–119. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg496