ABSTRACT

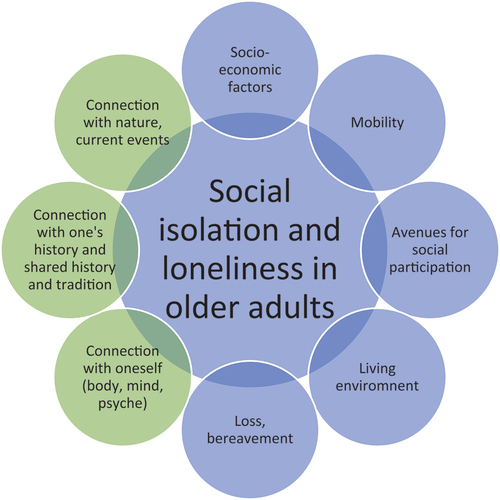

Older adults worldwide are facing disproportionate levels of isolation and loneliness. The current frameworks for understanding social isolation and loneliness include factors such as the physical and mental health of the individuals, loss of friends and family, level of education, relationships, and the built environment. While these models are useful, they fail to consider the individual experiences of older adults holistically; as an example, they do not include older adults’ relationship with themselves as they navigate the many challenges of life. In this article, I propose a novel framework for describing social isolation and loneliness in older adults that includes relationships to their changing bodies and experiences, to history and literature, and to nature and current events. Considering this revised framework, I summarize my observations as a teaching artist using Bharatanatyam, a 2,000-year-old Indian traditional dance form, in alleviating loneliness and isolation. Outcomes are in the form of qualitative narratives that are thematically united and presented. Given the highly communicative and relational nature of Bharatanatyam, I hypothesize that immersion in Bharatanatyam will enable connections of various kinds. This article describes three ways in which Bharatanatyam is particularly well-suited to build connections; these are 1. Connection with oneself in body, mind, and psyche; 2. Connection to tradition and history and 3. A systematic structure of relating to others, to the nature and environment, and current events.

Social isolation and loneliness in older adults as a critical public health issue

Older adults worldwide are facing enormous levels of isolation and loneliness (Reducing Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older People: World Health Organization, Citation2024; Social Isolation and Loneliness: World Health Organization, Citation2021). Social isolation is defined as the overt lack of social connections (Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, Citation2020), and loneliness is defined as the subjective ‘feeling of being alone’ irrespective of the number of social contacts one has. The two concepts are related, though not entirely the same. The WHO states that approximately one in three older adults experience social isolation worldwide. In the US, approximately one-fourth of community-dwelling individuals 65 and over are socially isolated, and a significant proportion of older adults face loneliness (Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, Citation2020). Research on the tangible impacts of loneliness suggests that loneliness and isolation could act as instigators for physical and mental conditions such as heart disease, high blood pressure, weakened immunity, and depression (Social isolation, Loneliness in Older People Pose Health Risks, Citation2019). Recognizing the impacts of social isolation and loneliness on individual and community health, the US Surgeon General issued a call for action characterizing social isolation and loneliness as a public health crisis in the general population and specifically older adults, and social connection as the cure (New Surgeon General Advisory Raises Alarm about the Devastating Impact of the Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation in the United, Citation2023). The recent COVID pandemic has also had significant impacts on older adults’ mental and physical well-being and has exacerbated functional limitations (Frutos et al., Citation2023; MacLeod et al., Citation2021). A disproportionate number of older adults (both in the community and nursing home settings) lost their social connections because of social distancing and the passing of loved ones due to COVID. Social isolation, in addition to negative impacts on health outcomes of the individual and the community, is also associated with an increase in healthcare spending. In the US, studies show that social isolation is linked to approximately $6.7 billion in annual additional Medicare spending (Medicare Spends More on Socially Isolated Older Adults; AARP, Citation2017). With people living longer lives, aging in place, and many times living far away from loved ones, social isolation and loneliness can negatively impact many more people in years to come if proactive and holistic steps are not promptly taken (Navigating Social Isolation and Loneliness as an Older Adult, Citation2022).

In this paper, I describe some of the frameworks currently used to conceptualize social isolation and loneliness in older adults, introduce the traditional Indian dance form of Bharatanatyam, and describe three specific ways in which this dance form can alleviate social isolation and loneliness in older adults. I have been trained in Bharatanatyam for more than two decades and continue learning from my gurus. I enrich my dance training by studying Carnatic music and Sanskrit and perform in and around New York City (NYC) to make Bharatanatyam accessible to all. I am also a neuroscientist and passionate about relieving suffering through the sciences and the arts. My work in creative aging was inspired by the loss of my mother and the lack of avenues she had towards the end of her life for safe, expressive movement. I hope to create a systematic-yet-creative framework to bring aspects of Bharatanatyam to all and hope to pass along the gift of movement to older adults in all settings.

The experiences described in this paper consist of working with approximately 500 older adults in a multitude of settings in and around NYC and the Greater Washington D.C. area. Sessions range from one-off interactions to sustained sessions, in-person, online, or in a hybrid setting. Based on information derived from notes, conversations and observations, I introduce and summarize qualitative information on the usefulness of this dance form to alleviate isolation and loneliness. Inferences and participant testimonials have been thematically arranged and presented.

Current frameworks to understand social isolation and loneliness, and their limitations

The study of social isolation and loneliness among older adults took an intense form during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, even before the pandemic, the impact of social isolation and loneliness on older adults and their physical and mental health was articulated (Donovan & Blazer, Citation2020). Three categories of mediators of isolation and loneliness in older adults were described: behavioral, psychological, and biological. Living alone, bereavement, sensory impairment, depression, and cognitive and physical limitations were proposed to be risk factors. Other risk factors that have been proposed are retirement, poverty, and caring for others, as well as gender identity and sexual orientation, belonging to an ethnic minority, disability, family circumstances, socioeconomic environment and the local area, and personal circumstances (Donovan & Blazer, Citation2020; CitationRisk factors for loneliness: Campaign to end Loneliness). While these factors undoubtedly contribute to social isolation and loneliness, they paint an incomplete picture.

Not taken into account in these frameworks are ageist attitudes that can contribute to a negative body image (Kang & Kim, Citation2022). Studies regarding self-perceptions of aging show nuanced results, such as a complex interplay of physical and social losses related to health-related variables and how they relate to one’s self-perception with age (Diehl et al., Citation2021). Older women who are survivors of physical and sexual violence and assault earlier in life have been shown to report PTSD well into older adulthood (Cook et al., Citation2011). While an increase in acceptance of one’s physical self has been described with aging (Shallcross et al., Citation2013), other studies describe several kinds of ‘aging body reminders’. These include ‘everyday body problems’ such as trouble breathing or sleeping; fear of falling; ‘body repairs’ such as surgeries for hips, knees, and cataracts, and medications for pain; and ‘body aids’ such as those for hearing, mobility, vision, showering or toileting (Barrett et al., Citation2020). Reviews of current ways to ease social isolation among older adults highlight the individuality of aging-related experiences which may make standardizing and scaling interventions challenging. The importance and challenges of positioning older adults with their unique lived experiences and history at the center of healthy aging programs have recently been described (Fakoya et al., Citation2020).

Limited access to culturally-sensitive adaptive movement and a shortage in the geriatric psychiatric workforce (Small, Citation1983) are just two of the factors that compound social isolation and loneliness. A city like New York City may seem to be exceptionally pedestrian-friendly, with intentional and abundant green spaces, but these are not always accessible for older adults who need assistive devices. Several intersections are particularly dangerous for older adults because the walk signals allow little time to cross (See you in a few centuries: DOT senior safety program for intersections would take 800 years to cover all of NYC, Citation2022), and stairs are a ubiquitous impediment to mobility. There is also the feeling of insecurity and vulnerability caused by the lack of infrastructure such as street lighting, increased criminal activities perpetrated towards older adults, and an increased sense of physical vulnerability and risk because of a sense of frailty and lack of defenses. The state of connectedness of older adults in cities without robust public transport is likely to be even more dire. The fragmented lives of cities and migration from other countries also lead to a sense of disconnect from one’s history and tradition. For older adults specifically, traveling back to their countries of origin may not be, physically or financially, possible, leading to a sense of disconnect. Considering the changing political and civil landscape, I have found that older adults feel strongly about world events and have the willingness and enthusiasm to work towards making the world better through volunteering (for example). However, such opportunities have dwindled for older adults with chronic health conditions and immunocompromised systems leading to a lack of socialization and purpose in life. Many times, older adults have few avenues to express their opinions about current political events or are deemed as ‘dated’ and not having anything important to add.

Role of the arts in alleviating social isolation and loneliness

The role of the arts in promoting social cohesion has been suggested; specifically, it has been shown that ‘creative placemaking’, the process of using arts to shape the physical and social characteristics of a place, can help achieve social cohesion and promote well-being (CitationCreative Placemaking: National Endowment for the Arts). The role of the arts in creating cohesion for crises and social movements for justice and public health, and the impact of innovative arts-based programming on aspects of public health such as immigrant food systems and public housing redesign have been described (Social Cohesion that Promotes Equity and Well-Being through Arts and Culture: Guidance for Research: Arts, Culture, and Community Development Citation2021). A professional field of creative aging has evolved over the last three decades and forms a subset of arts-in-health modalities (Ager et al., Citation1981); these efforts have been shown to be associated with quantifiable impacts in promoting social cohesion, decreasing loneliness, and renewing interest in life (Galassi et al., Citation2022; Jennie FRa, Citation2020). Creative aging activities include visual art, performance art, writing, and additional creative modalities to engage older adults and enable them to create art, enhance skills, combat loneliness, and build community (Ager et al., Citation1981; Hanna, Citation2013). Participants range from those that have been associated with an artistic practice all their lives, to those that are coming into art as a way of expression in older age (Coelho et al., Citation2022). Speaking of movement specifically, traditional and culture-specific dance practices, e.g. the Greek traditional dances and Portuguese traditional singing and dancing, have shown promising results as creative aging endeavors (Douka et al., Citation2019; Iyengar, Citation2023). A program called ‘The Community of Voices’ consisted of weekly choir sessions for a year and looked at the impacts of community choir singing on health and wellbeing. Engagement with this program was associated with ‘reduced feelings of loneliness and increased interest in life’ (Galassi et al., Citation2022).

Bharatanatyam for creative aging

While there are many positive impacts of the creative arts on social connection and well-being in general, it is important to consider non-Western artistic practices in creative aging, and the unique benefits of such traditional art forms. One such traditional art form is Bharatanatyam, a dance form that originated in South India over 2,000 years ago. As the country was subjected to political and civic upheavals such as invasions and colonization, the practice of Bharatanatyam changed over the centuries. This paper is an attempt to link Bharatanatyam as it is practiced today and its impacts on connection at various levels. Bharatanatyam consists of a systematized vocabulary of hand gestures, known as hastas, an embodied language of emotions called rasas, and a schema of rhythmic patterns or tala. Included in Bharatanatyam are components of music and melodic structures called raga and a narrative structure.

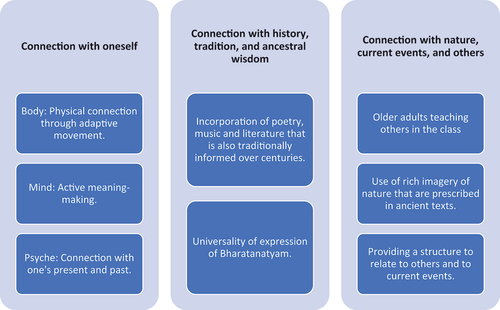

Traditional Eastern art forms are typically contemplative and inward-looking yet provide a connection with the world around us by supplying systematic ways of thinking about oneself and one’s place in the world. Literary works recognize, articulate, and propose a clear view of the individual’s place, and her connection with the world. For example, a simple verse that is familiar to students of Bharatanatyam is called Mangalam – this sloka (verse) connects the individual with the elements (earth, fire, water, wind), the extra-worldly (sky, sun, moon, planets), and with our physical bodies, minds, spirit, and with life itself. By employing themes that are relatable to all, participants also bring in their languages [e.g. fortuna in Italian; propicia in Spanish, and Hakol beseder in Hebrew ()] to express a feeling of being in balance or being in luck. A (predominantly Western) view is that the arts are inherently social – while the arts can be social, this perspective misses the huge impacts of the arts in helping us understand ourselves. Events such as an art opening, block party, etc. all help promote social cohesion, but a traditional art form like Bharatanatyam is more about connection with oneself, and the connection to others is secondary. I have had the opportunity to use aspects of Bharatanatyam for creative aging in a variety of settings: in-person, virtual, and hybrid settings, at senior centers, with people who have dementia with or without aides, and individuals with limited physical mobility (Iyengar, Citation2024; Iyengar, Citation2024; Johnson et al., Citation2020). Movements are adapted to be done by older adults dealing with (for example) arthritis and vertigo; or using assistive devices such as wheelchairs or walkers. Hastas provide an intuitive and safe way to engage with Bharatanatyam, as they can be done seated, and can be used to tell entire narrative stories (Iyengar, Citation2024). While hastas as prescribed in ancient texts such as the Abhinaya Darpana (CitationNandikesvara) are initially used along with their meanings, participants typically create additional ways of using prescribed hastas. Participants also create hastas of their own; indeed, in these very specific ways, older adults can familiarize themselves with the dance form and the power of gestures and their meanings (Iyengar, Citation2024). The approach and pedagogy of Bharatanatyam are also especially conducive to creative aging practices in three specific ways. First, the inherent complexity of the dance form supports and enables the purposeful layering of skills, e.g. participants first learn the physical act of creating hastas, then they learn their meaning and the facial expressions that support that meaning, and then they combine gestures to create a narrative. Second, Bharatanatyam depends on a close relationship with the tradition, as mediated by the relationship between guru and student. Using Bharatanatyam for creative aging can expand the role of the instructor and foster deep relationships. Third, Bharatanatyam practitioners learn many allied artistic modalities, e.g. music, symbolism, and philosophy. In creative aging practices, these modalities can be used to foster engagement and interest among participants with varied interests (Iyengar, Citation2024). In my work, I use watercolors, pastels, textile art, poetry, and a study of rhythm, a study of languages, poetry, and literature to engage people of different backgrounds with the benefits of creating art.

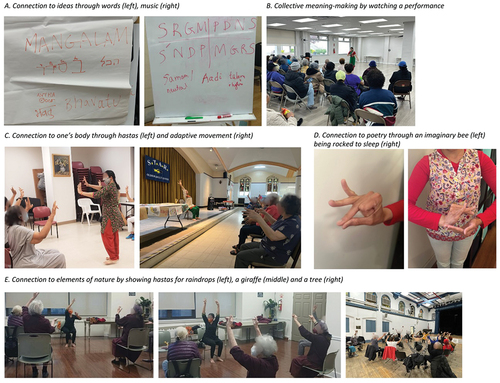

Figure 1. A. Connection to ideas through words (left) and music (middle). In the example to the left, a learner suggested the word manglam and its connection hakol beseder (‘everything is good’) in Hebrew. B. Collective meaning-making by watching a performance. C. Connection to one’s body through hastas (left) and adaptive movement (right). D. Connection to elements of nature through poetry, in this case, an imaginary bee (left) being rocked to sleep (right). E. Connection to elements of nature by showing hastas for raindrops (left) and a giraffe (middle) and a tree (right).

A key aspect of using Bharatanatyam for creative aging is to highlight the universality of the dance form. While some of the stories told require some knowledge of the Indian subcontinent and its specific cultural practices, most themes of Bharatanatyam are universal. The systematic structure of emotions (rasas) for example, provides an avenue for the incorporation of contemporary themes, apprehensions, joys, and victories. The traditional pieces in Bharatanatyam are associated with symbolism and philosophy and provide the distinct advantage of the thinking and wisdom of practitioners, philosophers, and artists who came before us. Through refinement over centuries, traditional art forms such as Bharatanatyam provide food for thought and a structure to respond to today’s problems.

The intentional pedagogical approach of Bharatanatyam enables ways of connecting not just with our histories and our bodies, but with poets and writers of the past, and with traditional knowledge. An art form like Bharatanatyam provides several ways of connection; three specific avenues described in this essay are 1. Connection with oneself in body, mind, and psyche; 2. Connection with tradition and history; and 3. Providing a systematic structure of relating to others, nature and environment, and current events.

The results reported here were developed over the course of three years of work with older adults, both individually and in groups. Connections in creative aging sessions happen in very personal ways that depend deeply on the individual in question and so, at this stage in our understanding, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis is the major tool available for uncovering themes and developing information. It is expected that future development will make possible hypothesis-driven investigation of these ideas.

Connection with oneself in body, mind, and psyche

The physical benefits of dance are numerous (Hanna, Citation2013; Marmeleira et al., Citation2009; Martin-Wylie et al., Citation2022); however, Bharatanatyam is only now being used for creative aging (Johnson et al., Citation2020), which is perhaps paradoxical given the depth of the form and its sustained universality over thousands of years. Bharatanatyam specifically includes many soft, subtle movements (e.g. movement to express one’s seeing a best friend unexpectedly), leaps and jumps (e.g. mimicking a deer or horse), and movements traversing space. The range of movements possible in Bharatanatyam offers a multitude of ways to engage with the form. For older adults, this choice gives a way to reconcile with a body that is different than it used to be. Anecdotally, in my sessions, I have witnessed two female participants recognizing the impacts of their history of sexual trauma and violence and contextualizing it with the grace they feel as they are learning Bharatanatyam. Participants mention that the movements of Bharatanatyam and the articulation of movements contribute to reducing falls and giving older adults a feeling of confidence. By combining the physicality of the dance with meaning, symbolism, and philosophy, Bharatanatyam helps participants connect themselves with the world at large. Many older adults report considerable frustrations related to an aging body, e.g. in the words of one participant ‘I fell off the bed today and feel embarrassed and ashamed’ and in the words of another participant, ‘I used to be so quick at grasping new things. I have seen a marked decline in my mental and physical abilities after the pandemic’. For many, old age is also associated with losses (‘I used to have curves; I used to look good’), and engagement in Bharatanatyam is an intentional act of acquiring a skill, and a novel way of relating to oneself in the physical sense. Other data corroborate the role of self-perception in older adults; a study done in the US showed positive self-perception correlated with lower rates of hospitalizations (Sun et al., Citation2017). Retirement has also been shown to be correlated with a decline in physical and mental health due to a decrease in physical activity, social interaction, and feeling of worth that employment provides (Dhaval Dave & Spasojevi, Citation2006). Specifically, Bharatanatyam offers the benefit of layering skills so that novel and challenging movements can be learned and accomplished. One aspect that is essential to the form is the gaze – students of Bharatanatyam learn myriad ways to move one’s eye, and intentional use of the gaze helps engage with the narrative. For older adults who may have arthritis or mobility issues, the eyes provide an achievable alternative for participation in the dance.

The meaning-making aspect of Bharatanatyam is critical, as every gesture and every glance has a meaning and place in the larger narrative. Participants also mention that while they find Indian dance beautiful, it is the added aspect of meaning that drives them to learn this art form. Many say that learning the exact meaning is like being privy to a mysterious world. By concentrating on creating and appreciating meaning in real time, participants develop their skills of focus, concentration, and even patience with themselves. As one participant talks about finding grace, beauty, and meaning in her body, ‘There is a sense of serenity and magical beauty that comes through hand movements. As we move in unison, we become graceful bodies in motion. It is a journey of wonder! It is an awesome and spiritual experience. I also feel a heightened awareness and sensitivity of my surroundings through the dance’. Through these specific ways, older adults participating in Bharatanatyam become generators of beauty and meaning making as opposed to passive consumers. shows participants immersing themselves by watching performances and engaging in collective meaning-making, and shows learners engaging with their bodies through hastas and adaptive movement. Learners also report feeling self-sufficient; according to one participant, ‘It made me realize that I can make achievements for my benefit when having patient, encouraging people assisting me’. Participants report self-confidence at trying the movements; ‘I am proud of doing things that I have never done in my life’.

Connection with tradition and history

By engaging in Bharatanatyam, as practitioners or as the audience, older adults are actively becoming part of the history and broader lineage of the art form. Two main aspects of Bharatanatyam that foster a connection with history, tradition, and ancestral wisdom are the incorporation of poetry and music that can be as old as the dance itself, and the universality of expression that Bharatanatyam affords. The connection with poets and thinkers of the past is unique to Bharatanatyam, as is the aspect of learning additional creative modalities such as language, music, and semiology (Iyengar, Citation2024). Speaking to the universality of the art form, participants can take part in the lineage of the dance and use the vocabulary to create narratives that are personal to them. Traditional art forms such as Bharatanatyam provide a rich source of knowledge, yet their inclusion and introduction to individuals who may not be familiar with these art forms needs to be done with care and respect. A program in British Columbia, for example, created models that examined the intersection between indigenous and Western music and considered their applicability in educational settings (Prest et al., Citation2022). Some guides on incorporating indigenous music for health and wellness include collaborations between practitioners and the public, creating and maintaining reciprocal relationships with practitioners of the art form, accurately acknowledging ownership, and respecting processes and values and not just the final product (Embracing Local Indigenous Peoples’ Ways and Music in School Music Classes National Association for Music Education, Citation2022); these frameworks can be used for Bharatanatyam and other traditional art forms as well.

Participants routinely mention ‘feeling renewed, joyful, as well as being part of world culture’ after these sessions. A song written in the 16th century ‘Thumak Chalata’ describes the sound of the anklets of an infant as he is learning to walk. The toddles of the child make the sound especially delightful, and participants very quickly relate to this song, from their own experiences of taking care of children and grandchildren. Participants play active roles in the choreography by showing ways of communicating with a child that age and encouraging him to stay still long enough to put anklets on his feet. A song like this is also a great way of leaning into participants’ expertise and experiences, de-emphasizing the hierarchical role of the teaching artist and promoting equality and sharing.

The use of gestures as prescribed in the ancient texts is also a way to learn about the history and geography of the past. For example, birds such as storks, cranes, hawks, owls, and ospreys are mentioned in the Abhinaya Darpana (CitationNandikesvara) and provide a conversation about the biogeography of the time it was written. Learning the history of the dance itself is another way to impart cultural sensitivity, and the study of the history through Bharatanatyam connects people across time and space and can help us understand how and why people are different from us. Learning about the past can help us connect to the future and events that may come next. In the words of a student: ‘I now understand the connection of the movements to the narrative, and the relationship between the dancer and a deity, and the relationship between the dancer and the poet’.

As a humanizing dance form, Bharatanatyam can be a way to express authentically, incidents or emotions that affect us. While working on a song Asai Mukham, where the poet is narrating that he has forgotten his dear mother’s face, participants can appreciate the complexity of such an emotion, many having taken care of those with dementia. In the words of one participant ‘This is life; there are good things and there are not-so-good things. All we can do is take it all in stride’.

Connection to others, to nature, and current events

Social connection has been shown to be a protective factor against loneliness and isolation. The structure, function, and quality of social connections create a multifactorial construct including the number and quality of connections and the availability of connections to fulfil needs. Studies have also articulated the ‘pyramid of vulnerability’ at the level of population health; participants can be at risk for isolation, begin to disconnect, or be highly isolated (Holt-Lunstad, Citation2021; Nobel, Citation2020). There are several theories that inform human connection such as the ‘social exchange theory’ which emphasizes reciprocity and fairness, the ‘attachment theory’ for relationships with caregivers (as an example), and the ‘social learning theory’ that emphasizes the position of role models and reinforcement in creating and sustaining relationships (CitationUnderstanding The Dynamics Of Human Connection).

The central precept in Bharatanatyam is that of Abhinaya with the literal meaning of ‘carrying towards’. The emphasis on connection is so great that it enables the dance form to transcend its originating cultural context, making it highly suitable for Westerners whether or not they have ever been interested in India. Hence, Bharatnatyam is in essence, a communicative dance form and its vocabulary of hastas, rasas, rhythm, melody, etc. are in service of communication. In group sessions, students who have been learning Bharatnatyam for a while generally take on the responsibility of showing others; this removes the instructor from the picture and gives participants agency over movements. In the words of one learner ‘It gives me something to look forward to; it’s a great thing for the community and for those who don’t get out much’. The study of emoting through rasas requires practitioners to imagine themselves in the shoes of the character or the poet. A popular song written in the 15th century, Vaishnava Janato was a favorite devotional hymn of Mahatma Gandhi, and by working on this piece, participants wonder about the struggles he had, the tactics he used to overcome them, and how his principles may be applied to events today. While learning the Mangalam described above, one participant mentioned ‘I feel more in touch with the world around me; my relationship with leaves, trees, birds, and pets have deepened’.

In recent sessions, participants connected with a song Maithreem Bhajatha that was sung at the United Nations General Assembly in 1966; this song entreats listeners to cultivate friendships, renounce competitions, comparison, and aggression, practice restraint, and look at others as we look at ourselves. This song and its gestures were particularly poignant considering recent world events and geopolitical unrest.

Bharatanatyam is rich with depictions of nature, and to individuals with limited mobility, can provide an exceptional way to connect with nature. shows participants learning hastas for raindrops, a giraffe, and a bird. While putting to movement a poem on a butterfly written by Arun Kolatkar, participants can visualize the vivid colors of the butterfly, and the specific movements it makes as it perches on a flower, and add to a sense of wonder at being able to witness something so subtle, beautiful, and fleeting. In another session, participants worked on a piece where a bee was the central character, as the poet requested the bee to take her message to a faraway place. By visualizing the buzzing movements of the bee, and the sound it makes, and by articulating one’s relationship (as the poet) to the bee, participants with dementia took care of this imaginary bee by gently talking to it and rocking it, as one would a baby ().

Effect on the instructor involved in bharatanatyam for creative aging

In doing this work, I have also strengthened my connections with and between my artistic and scientific disciplines by intentionally recognizing that my work has a direct impact on individuals. I am aware of the potential to do harm as well, and I constantly assess the words I use, and examine the space for physical and emotional safety for participants. Being responsive to each person as an individual is key; for example, earlier in this work, at the beginning of a session, I asked a participant how his week was going. This person (a full-time caregiver to his partner with dementia) said that all weeks are alike for him. I stopped using that greeting for him and started focusing on the present moment instead of even the recent past. Additionally, I am conscious of how to use participant information for public health research in ways that are empowering to learners and respectful to Bharatanatyam and the tradition of India.

As a practitioner of Indian origin doing this work in the United States, I am aware of the demeaning and patronizing ways in which India (and perhaps of other low-and-middle income countries) is represented in the West. Through Bharatanatyam, I get a chance to present India, my culture, and my teachers in a beautiful, empowering light. Bharatanatyam is also distinguished in the way it is taught – like other classical artistic forms, the pedagogy requires sustained attention and work over a period of several years. Since creative aging setting sessions can be one-off, staying true to the approach and pedagogy of the form can present a challenge. An approach where minute, subtle nuances are important, and where participants may work on a piece over time can be unfamiliar to participants who are used to moving through songs at a rapid pace and where loudness and flash are mistaken for passion.

As a practitioner of Bharatanatyam, working with older adults makes me more aware that simple steps (adavus) of Bharatanatyam are beautiful, and addition of modalities such as fabric, color, patterns can bring out the inherent profundity in the form. Most importantly, it is a privilege to empower older adults as they reassert themselves as generators of meaning and beauty.

Conclusions and future directions

Social isolation and loneliness are dire public health issues, and we need multidisciplinary ways of addressing these issues in older adults, in ways that are focused on the individual and their lived experiences. While current models of social isolation and loneliness include factors such as socioeconomic and educational status, additional aspects such as relationship to oneself, nature, and current events need to be included, to provide a holistic sense of what it means to be connected in this changing world. Social isolation and loneliness are multifaceted issues, and older adults likely need a variety of individual support. Bharatnatyam provides a way for older adults to connect with themselves and their histories, connect with history and tradition, poets, and thinkers of the past, and with nature and others. While this manuscript offers descriptive observations on how immersion in Bharatanatyam and help facilitate connections of various kinds, more detailed, directed, and systematic studies will shed light on important nuances.

The implications of this work are many. One is that definition of factors leading to isolation and loneliness needs to be expanded, to include a lack of connection with nature, history and tradition, and current events (). The second implication relates to funding for creative aging programs; typically, private and government funders mandate a certain number of people. While the absolute number seemingly makes data collection easier, it is not informative about how deep or meaningful the connections are and fails to evaluate the impact of the program on the individuals it serves. A profound influence on a single individual is as important as a superficial impact on every member of a crowd.

Figure 2. A holistic framework to articulate social isolation and loneliness in older adults. The issues in blue have been described before (Kemperman et al., Citation2019); the ones in green are proposed in this paper.

Thinking about the individual engaged in Bharatanatyam opens one’s eyes to the idea that connections happen in many ways, that genuine connection may even require small groups and an intimate setting, and that imposing arbitrary numbers on it helps exacerbate the loneliness and isolation that older adults are already feeling. For example, talking about difficult experiences in one’s past requires smaller, intimate settings. We also need novel ways of quantifying the impacts of a traditional art form like Bharatanatyam, where the focus and intent are on individual impact, and over time, aggregated impact. Above all, Bharatanatyam provides many ways of connecting to older adults that are unique to the form (). Practitioners of other art forms can potentially use lessons from Bharatanatyam to increase the depth of connections in their creative aging practices in a way that is authentic to this art form and its tradition. Future work includes exploring the impact of Bharatanatyam in alleviating social isolation and loneliness in a multitude of communities and settings, as well as systematically understanding the impacts of this dance form on the psychology of older adults.

Author contributions

The author, Sloka Iyengar, is responsible for all aspects of this manuscript, its conception, design, data collection, thematic analysis, data interpretation, drafting of the paper, and revising it critically for intellectual content. No other author is involved with the work described in the manuscript.

Ethics approval

The manuscript has no personal or identifying information about the participants.

Informed consent

The manuscript has no personal or identifying information about the participants.

Participant images

Participants have been de-identified; the author, Sloka Iyengar consents to her image being published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The manuscript has no personal or identifying information about the participants. The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ager, C. L., White, L. W., Mayberry, W. L., Crist, P. A., & Conrad, M. E. (1981). Creative aging. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 14(1), 67–76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7044991/

- Barrett, A. E., Feeling Old, G. C., & Carr, D. (2020). Body and soul: The effect of aging body reminders on age identity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(3), 625–629. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby085

- Coelho, P., Marmeleira, J., Cruz-Ferreira, A., Laranjo, L., Pereira, C., & Bravo, J. (2022). Creative dance associated with traditional Portuguese singing as a strategy for active aging: A comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(Suppl 2), 2334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12978-4

- Cook, J. M., Dinnen, S., & O’Donnell, C. (2011). Older women survivors of physical and sexual violence: A systematic review of the quantitative literature. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(7), 1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2279

- Creative Placemaking: National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/CreativePlacemaking-Paper.pdf

- Dhaval Dave, I. R., & Spasojevi, J. (2006). The effects of retirement on physical and mental health outcomes. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w12123/w12123.pdf

- Diehl, M., Wettstein, M., Spuling, S. M., & Wurm, S. (2021). Age-related change in self-perceptions of aging: Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of change. Psychology and Aging, 36(3), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000585

- Donovan, N. J., & Blazer, D. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a national academies report. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(12), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005

- Douka, S., Zilidou, V. I., Lilou, O., & Tsolaki, M. (2019). Greek traditional dances: A way to support intellectual, psychological, and motor functions in senior citizens at risk of neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 11, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00006

- Embracing Local Indigenous Peoples’ Ways and Music in School Music Classes National Association for Music Education. (2022). https://nafme.org/blog/embracing-local-indigenous-peoples-ways-and-musics-in-school-music-classes/

- Fakoya, O. A., McCorry, N. K., & Donnelly, M. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6

- Frutos, M. L., Cruzado, D. P., Lunsford, D., Orza, S. G., & Cantero-Téllez, R. (2023). Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on daily life activities and independence of people over 65: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054177

- Galassi, F., Merizzi, A., D’Amen, B., & Santini, S. (2022). Creativity and art therapies to promote healthy aging: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 906191. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.906191

- Hanna, G. P. (2013). The central role of creative aging. Journal of Art for Life, 4(1). https://journals.flvc.org/jafl/article/view/84239

- Holt-Lunstad, J. (2021). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors: The power of social connection in prevention. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 15(5), 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276211009454

- Iyengar, S. (2024, June 24). The use of hand gestures (hastas) in Bharatanatyam for creative aging. The Journal of Medical Humanities. https://link.springer.com/epdf/10.1007/s10912-024-09861-1?sharing_token=V4ThaWN-32DdGTOWHhRp_Pe4RwlQNchNByi7wbcMAY66aQ_GQ6N9vh825Y_CnmLVP7TJ-kYeBDmPVI2VcsnPR0TVbrIq9M6493zoS3jQmnjjdwcW9ltMSiXvX7TQRRG2CsaZAG9b6wl79DMFvB6P0nJ3tG7X5FJAc8z2vJ6W458%3D

- Iyengar, S. S. (2023). BMJ medical humanities blog 2023. https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-humanities/2023/03/07/bharatanatyam-in-creative-aging/

- Iyengar, S. S. (2024). Application of bharatanatyam pedagogy for creative aging. In Review: Journal of Dance Education.

- Iyengar, S. S. (2024). Facilitating adaptive movement in older adults through Bharatanatyam. In press perspectives in public health.

- Jennie FRa, K. (2020). Creative aging in NYC. https://brookdale.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Creative-Aging_ExecSum.pdf

- Johnson, J. K., Stewart, A. L., Acree, M., Nápoles, A. M., Flatt, J. D., Max, W. B., & Gregorich, S. E. (2020). A community choir intervention to promote well-being among diverse older adults: Results from the community of voices trial. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(3), 549–559. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30412233/]

- Kang, H., & Kim, H. (2022). Ageism and psychological well-being among older adults: A systematic review. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 8, 23337214221087023. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214221087023

- Kemperman, A., van den Berg, P., Weijs-Perrée, M., & Uijtdewillegen, K. (2019). Loneliness of older adults: Social network and the living environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030406

- Kolatkar, A. The Butterlfy. https://allpoetry.com/poem/8619585-The-Butterfly-by-Arun-Kolatkar

- MacLeod, S., Tkatch, R., Kraemer, S., Fellows, A., McGinn, M., Schaeffer, J., & Yeh, C. S. (2021). COVID-19 era social isolation among older adults. Geriatrics (Basel), 6(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6020052

- Marmeleira, J. F., Pereira, C., Cruz-Ferreira, A., Fretes, V., Pisco, R., & Fernandes, O. M. (2009). Creative dance can enhance proprioception in older adults. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 49(4), 480–485. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20087310/

- Martin-Wylie, E., Urmston, E., & Redding, E. (2022). Impact of creative dance on subjective well-being amongst older adults: An arts-informed photo-elicitation study. Arts & Health, 1–17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36519236/

- Medicare Spends More on Socially Isolated Older Adults; AARP. (2017). https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/health/coverage-access/medicare-spends-more-on-socially-isolated-older-adults/

- Nandikesvara. The mirror of gestures (Abhinaya Darpana). https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/hinduism/cooma-mirrorofgesture.pdf

- Navigating Social Isolation and Loneliness as an Older Adult: National Council on Aging 2022. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25663/social-isolation-and-loneliness-in-older-adults-opportunities-for-the

- New Surgeon General Advisory Raises Alarm about the Devastating Impact of the Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation in the United. (2023). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/05/03/new-surgeon-general-advisory-raises-alarm-about-devastating-impact-epidemic-loneliness-isolation-united-states.html.

- Nobel, J. (2020). Loneliness in older adults: Urgency and opportunity. U-Maine Colloquium:https://mainecenteronaging.umaine.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/201/2020/11/The-Challenge-of-Older-Adult-Isolation-and-Loneliness.pdf

- Prest, A., Goble, J. S., & Vazquez-Cordoba, H. (2022). On embedding indigenous musics in schools: Examining the applicability of possible models to one school District’s approach. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 41(2), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/87551233221085739

- Reducing Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older People: World Health Organization. (2024). https://www.who.int/activities/reducing-social-isolation-and-loneliness-among-older-people

- Risk factors for loneliness: Campaign to end Loneliness. https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/risk-factors-for-loneliness/

- See you in a few centuries: DOT senior safety program for intersections would take 800 years to cover all of NYC. (2022). AM New York. https://www.amny.com/news/dot-proposal-to-make-intersections-safer-for-seniors-would-take-800-years-to-cover-entire-city/.

- Shallcross, A. J., Ford, B. Q., Floerke, V. A., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). Getting better with age: The relationship between age, acceptance, and negative affect. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 104(4), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031180

- Small, G. W. (1983). Health manpower shortage in geriatric psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(11), 1256–1257. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100102018

- Social Cohesion that Promotes Equity and Well-Being through Arts and Culture: Guidance for Research: Arts, Culture, and Community Development 2021. https://communitydevelopment.art/node/66201

- Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults. (2020). National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine:http://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25663/social-isolation-and-loneliness-in-older-adults-opportunities-for-the.

- Social Isolation and Loneliness: World Health Organization. (2021). https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/social-isolation-and-loneliness

- Social isolation, Loneliness in Older People Pose Health Risks: National Institute on Aging.2019. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/social-isolation-loneliness-older-people-pose-health-risks

- Sun, J. K., Kim, E. S., & Smith, J. (2017). Positive self-perceptions of aging and lower rate of overnight hospitalization in the US population over age 50. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(1), 81–90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27359184/

- Understanding The Dynamics Of Human Connection. Human Institute. https://humaninstitute.co/understanding-the-dynamics-of-human-connection/