ABSTRACT

Processes of urbanisation create peri-urban spaces that are socially and institutionally fluid. In this article, we analyse how contestations and competition over declining water resources in peri-urban Kathmandu Valley in Nepal reshape water use, access and rights as well as user communities themselves, by creating and reproducing new and existing exclusions and solidarities. Traditional caste-based discriminatory practices, prohibiting Dalits from physically accessing water from sources used by higher castes, are said to be no longer practiced in Nepal. However, our findings show that, exclusion persists for Dalits even though the characteristics of exclusion have changed. In situations of competing water claims in the research location, Dalit households, unlike higher-caste groups, are unable to exercise prior-use water rights. Their water insecurity is compounded by their relative inability to mobilise political, social and economic resources to claim and access new water services and institutions. By juxtaposing the hydro-social and social exclusion analytical frameworks, we demonstrate how exclusions as well as interpretations and experiences of water (in)security are reified in post-Maoist, supposedly inclusive Nepal.

Introduction

Nepal presents a paradoxical urbanisation situation: Kathmandu Valley, where the capital Kathmandu is located, is one of the fastest-growing South-Asian urban agglomerations in the least urbanised country of South Asia (Muzzini and Aparicio Citation2013). Rapid urbanisation entails dynamic movements of people and resources between expanding urban and neighbouring peri-urban spaces. These hybrid (intermixed ‘rural’ and ‘urban’) spaces are rapidly changing, both ecologically and socio-economically (Leaf Citation2011; Narain and Prakash Citation2016). The dynamic character and complexity of the peri-urban landscape leads to a reshaping of resource uses of particularly land and water, which results in diverse forms of contestation and conflict (Allen Citation2003; Butterworth et al. Citation2007).

Several studies discuss the dynamics of competing claims on water in contested peri-urban spaces (Mehta et al. Citation2014; Narain Citation2014, Citation2016; Narain and Singh Citation2017; Shrestha, Roth, and Joshi Citation2018), but very few studies pay attention to caste-determined water exclusions in peri-urban contexts in South Asia.Footnote1 The few studies that discuss caste and water in peri-urban context (Prakash and Singh Citation2016; van der Woude Citation2016; Vij and Narain Citation2016) often report on the traditional nature of caste-determined water exclusions.

In this paper, we show how caste-based exclusions of Dalits are reproduced in (water) governance institutions, processes and mechanisms in peri-urban spaces, by exploring how changes in flows of water and movements of people result in ‘water and society mak(ing) and remak(ing) each other’ (Linton and Budds Citation2014, 170). In doing so, we bring together the conceptual frameworks of social exclusion and hydro-social processes. This allows analysing the meanings and experiences of exclusion through a water lens: how and why some, relative to others, are better able to claim access to and control of water in a rapidly evolving peri-urban location in Nepal. Our analysis shows that, in this dynamic peri-urban space, the Dalits continue to experience exclusions from water, even though the nature of such exclusions has changed.

It is said that the word ‘Dalit’, meaning ‘broken’, ‘ground down’, ‘downtrodden’, or ‘oppressed’ (Nepali Citation2018) was first coined by the Indian socialist reformer, Jyotirao PhuleFootnote2 in the 1930s, as a retaliatory political stand to emphasise the history of oppression and subjugation of a group of people who were placed outside the four-fold varna Footnote3 in which Hindu society is structured. As in India, the Dalits in Nepal are a historically excluded social group. Gurung (Citation2005) writes that Nepal’s historic constitutional amendment, Muluki Ain (Law of the Land), shaped by majority Hindu ideology, placed Dalits at the lowest tier of society as ‘untouchables’. Thus, unlike in India, where exclusion was more a social code of conduct, in Nepal it was formally legalised in 1854 by categorising Dalits as those who are ‘Chhoyi Chhito Halnu Parne’ – ‘those whose touch pollutes others’. After contact with Dalits, members of all other caste groups in the four-fold varna system were required to undertake a ritualistic purification by sprinkling water (further purified by the touch of gold) over themselves.

Although caste-based discrimination in Nepal was constitutionally abolished in 1963 and reshaped to some extent by the 1996–2006 civil uprising or people’s movement known as the ‘Maoist People’s War’, these changes were superficial and opportunistic rather than structural (Bownas Citation2015). Many studies show that the historic fault lines between the castes, particularly in relation to the Dalits, continue to determine political decision-making, policies and the actual practices of their implementation in Nepal (Nightingale Citation2002; Citation2005; Devkota Citation2005; Thoms Citation2008; Sunam and McCarthy Citation2010; Bownas Citation2015; Bownas and Bishokarma Citation2018; for community water taps in eastern Nepal, see Udas, Roth, and Zwarteveen Citation2014).

Pariyar and Lovett (Citation2016) make the interesting observation that, although urban migration provides Nepali Dalits an escape from traditional caste-based discrimination, such disparities for Dalits continue even in the urban context. These authors as well as Bownas (Citation2015), who note ‘the fragility’ of the hard-fought local victories of the Dalits, help explain how the nature of water exclusions has changed, but water exclusion itself continues for the Dalits in peri-urban spaces.

In the location of our research, Lamatar, an urbanising Village Development Committee (VDC) in Kathmandu ValleyFootnote4, we did not hear or see blatant examples of traditional socio-culturally embedded practices of the caste-based ‘purity-impurity continuum’ (ILO Citation2005, 22) that, in the distant past, made water touched by the Dalits ‘polluted’, thereby restricting their access to public water sources and infrastructure used by the higher castes. Yet the Dalit households in Lamatar are still excluded from secure access to and availability of water. The play of politics, power and privilege shape, and are shaped by, changing peri-urban socio-ecological and institutional contexts. By analysing how water is governed in these dynamic peri-urban spaces, we were able to understand how, despite policy emphasis on the inclusion of Dalits, they remain excluded.

Conducting research in Lamatar was particularly useful for an in-depth analysis. As competition for water intensifies between older residents and recently settled migrants, prior-use rights to waterFootnote5, recognised in Nepal both informally and by law (Pradhan Citation2000), are often used to stake claims. This works for the higher caste groups, but unfortunately not for the long-time Dalit residents. They seem to easily lose ‘their’ prior-use water rights, and exclusion takes place relatively easily, because the Dalits are essentially placed outside the boundaries of the older place-based ‘community’, as well as of an emerging socio-economically defined new community.

The article is structured as follows: firstly, we discuss how a nuanced analysis of social exclusion is pivotal to understanding the dynamics and politics of hydro-social interrelations. Then we introduce Lamatar VDC and explain the research methodology adopted for this study. This is followed by a detailed overview of the research findings, which illustrate how some become water secure and others water insecure, some get included and others excluded in this peri-urban village, with Dalits often on the losing side. We conclude that it is essential to understand the historical, contextual fabric of exclusions in order to understand contemporary hydro-social complexities.

Exclusion and the hydro-social dynamics of water (in)security in peri-urban spaces

The concept of social exclusion refers not just to the presence or absence of rights but to a broad array of powers accessible to certain (groups of) people and denied to others (Kabeer Citation2000, Citation2005; Hall, Hirsch, and Li Citation2011). Although ‘social exclusion’ is a contested concept (de Haan Citation1998; Sen Citation2000; Hickey and du Toit Citation2007), it offers diverse insights in analysing how disparities are mediated and resources as well as opportunities granted or denied through complex intersections of social, economic, political and cultural processes, and how these are mirrored in policies, institutions and institutional norms and rules. Given the deep-rootedness of exclusionary attitudes and practices, understanding exclusion requires studying dynamic interrelations between the excluding and the excluded actors, with an emphasis on processes and mechanisms of exclusion, as well as the contested and contingent nature of power, institutions, agency, culture and social identity (Pradhan Citation2006; Lakhani, Sacks, and Heltberg Citation2014; Khan, Combaz, and McAslan Fraser Citation2015).

As explained above, water has been both a medium and source of exclusion for the Dalits in the four-fold varna hierarchy of Hindu society (Sharma Citation2003; Joshi and Fawcett Citation2006). In Nepal, the Muluki Ain of 1854 defined the grounds of caste-based hierarchy and dictated the norms and behaviour of various caste groups.Footnote6 This early legalisation has also cemented many other disparities for the Dalits, as outlined in the ancient religious legal text Manusmriti (Laws of Manu). This text frames Dalits as ‘fringe people’, to be isolated from social interactions, excluded from all socio-economic, legal and political assets and processes, including land, property, education, religious practices, and to be rigorously punished for any violations (see Buhler Citation1886). The Muluki Ain also emphasised that ‘the lower the caste the higher the degree of punishment for the same offence’ (Bennett Citation2005; World Bank Citation2006). Centuries of such deep-rooted discrimination are not easily resolved. Dalits remain the poorest social group in Nepal, either landless or with small landholdings compared to other caste-groups (UNDP Citation2008; Khanal, Gelpke, and Pyakurel Citation2012; Sunar et al. Citation2015).Footnote7

Lawoti (Citation2010) notes that various constitutional reforms, particularly those in 1990, have aimed to reduce caste-based exclusions and inequalities. The Maoist insurgency between 1996 and 2006 also provided an avenue for the socially marginalised to mobilise against various types of exclusion (Lawoti Citation2010; Nightingale Citation2011; Bownas Citation2015; Thapa Citation2015). ‘Social inclusion’ is now identified as one of four pillars of a just, democratic state of Nepal, as outlined in the Tenth Periodic Development Plan of Nepal (2002–2007) (Bennett Citation2005; ILO Citation2005). However, exclusions experienced by the Dalits are often blurred in the political framings of marginalisation by other factors of divide, such as class, gender, disability, ethnicity, sexuality. This is most evident in Nepal’s recent ‘Gender Equality and Social Inclusion’ policy framework (see ADB Citation2010; Sunar et al. Citation2015). It is, therefore, not surprising that particularly Dalit groups argue that, while traditional caste-based discriminatory practices may no longer apply and there is greater awareness of the illegality of caste-based discriminations in post-Maoist democratic NepalFootnote8, historic injustices persist and permeate social practices as well as national, regional and local planning and political processes (Lawoti Citation2010; Nightingale Citation2011; Sunar et al. Citation2015; Thapa Citation2015; Bownas and Bishokarma Citation2018).

All of this explains why ‘in relation to all human development indicators, Dalits score far below the national average’ in Nepal (Khanal, Gelpke, and Pyakurel Citation2012, 17). It is in this context of persisting caste-based social stratification in South Asia that scholars emphasise the need for detailed and contextualised studies in understanding how caste operates and shapes differentiation in access to resources in evolving socio-political and economic contexts (Gorringe, Jodhka, and Takhar Citation2017).

In this article, we research this important but under-researched issue with a focus on the peri-urban space, which is undergoing rapid changes in resource uses, socio-political relationships and institutional mechanisms with increasing urban expansion (Allen Citation2003; Butterworth et al. Citation2007; Narain Citation2009, Citation2016). Does such dynamism in the peri-urbanisation process help transform existing caste-defined exclusions, especially if policies are enabling? This is the key question for us in exploring this issue. In our research, we focus on contestations around water as in-depth analyses of hydro-social processes (see Swyngedouw Citation2009; Linton and Budds Citation2014) provide important insights on micro-dynamics of power underlying exclusion and inequalities in urbanising communities (Mehta and Karpouzoglou Citation2015; Narain Citation2014).

Our research objective was to understand how notions like ‘community’ and ‘identity’ are shaped by power, difference and divide in fluid peri-urban spaces, and how these are manifested in existing as well as evolving forms and processes of water governance and management. Analysing how different communities explore new ways to claim and access contested water sources in peri-urban Kathmandu Valley, our findings indicate that, for the Dalits, caste operates as a persisting determinant of social differentiation, intersecting with and shaping peri-urban water (in)security. We conclude that water insecurity develops in complex ways during urbanisation processes, and that these processes can take on a marginalising, discriminatory and exclusionary character for groups like the Dalits. In order to be able to reduce such water-related inequalities and insecurities, we argue the need for more nuanced analyses of the processes and mechanisms underlying co-evolving water-society interrelations and how these shape differential experiences of water access, allocation and exclusion in these spaces.

Study area and research methodology

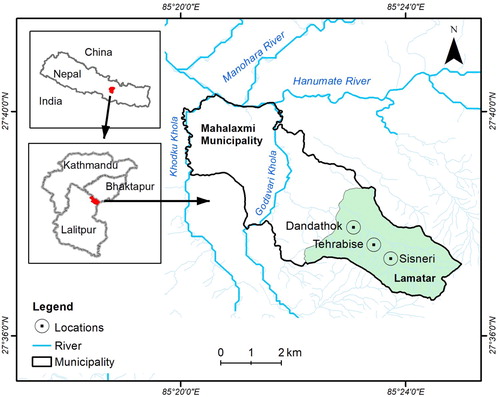

Our research case study is Lamatar VDC, which lies some 16 km southeast of Kathmandu city. This urbanising area was merged with four other peri-urban VDCs to form Mahalaxmi Municipality (urban body) in 2014. As a typical peri-urban space, Lamatar is administratively urban, while rural socio-cultural norms, local governance and self-mobilised institutional mechanisms and practices still prevail. For example, Lamatar has 11 community-managed forests, which are also the sites of several groundwater springs tapped for domestic and drinking water purposes. The nine administrative units, called ‘wards’, in Lamatar consist of villages and hamlets, the latter (often) named after the majority sub-caste group (see note 1) living here traditionally (e.g., Thakuri Gaun, Khadka Gaun, Karki Gaun). While its increase in population (0.8% annually) and number of houses (from 1,497 to 1,759 between 2001 and 2011; CBS Citation2001, Citation2012) have been gradual, the landscape is changing rapidly. The conversion of agricultural land into residential plots, which started in the 1990s, intensified from the mid-2000s. A commercial housing colony lies side by side with still rural hamlets in Lamatar.

Studying a particular location, event or process helps to understand the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of contemporary issues in a real-life context (Yin Citation2009). In Lamatar, we adopted an actor-oriented approach (Long and Long Citation1992; Long Citation2001) to analyse conflicts and contestations over water. An actor-oriented approach ‘points to who is doing what, in relation to whom’, which helps in identifying power relations, particularly in shaping access and exclusion (Khan, Combaz, and McAslan Fraser Citation2015, 3). According to Seur (Citation1992), this is a useful way to understand processes of social change. Following this approach involves interviewing key informants more than once and using the snowball method to interview a network of relevant actors. In our study, we have focused on understanding attitudes, perspectives, values and practices, including the meanings people give to their experiences (Elliot Citation2005) and interactions in relation to water access, use and related decision-making. Thus, our findings show not just what happened, but how events and processes relating to water are perceived and experienced by various actors narrating their complex and often conflicting stories and experiences.

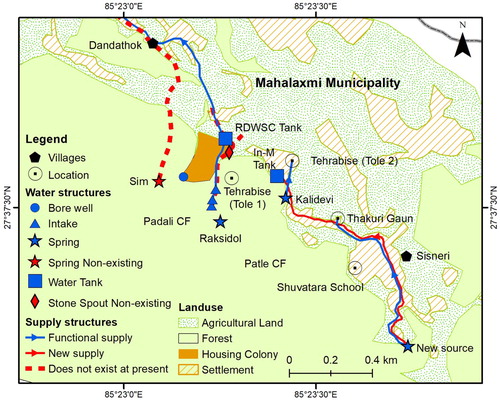

We primarily interviewed residents of three villages and hamlets in Lamatar: Tehrabise, Dandathok, and Sisneri (see and ). When relevant, residents of nearby villages were interviewed. These respondents were male and female, youth and elderly, old inhabitants and new in-migrants, all with various caste and class backgrounds. We also interviewed key stakeholders in water governance and management: chairpersons and representatives of village-level drinking water supply committees, chairpersons of community groups (the forest committee, teachers, the ward secretary and the coordinator of the ward-level citizen forum), the elected ward chairperson for Lamatar, and various officials from governmental and non-governmental organisations. Most of these respondents were higher-caste men, who took decisions on water and built, operated and managed water infrastructure. The empirical data presented here are based on interviews with 74 informants, which included 44 men (of which nine were Dalits), 30 women (14 Dalits), four government officers and two from non-governmental organisations. Many respondents were interviewed more than once. We conducted numerous informal talks and, specifically, 41 conversational interviews and 24 open and semi-structured interviews. We also reviewed recently published and grey literature to understand the dynamics of caste-based disparities in Nepal, focusing particularly on Dalits.

The hydro-social dynamics of exclusion and water insecurity in Lamatar

Static caste-based institutions and the control of a dynamic resource

In the early-1990s, higher-caste villagers living in an upstream ward (number 7) of Lamatar VDC secured government funding and support to develop a piped water scheme from a reliable groundwater spring (known locally as sim). This community had been using the water source historically, i.e., they had secure prior-use rights to the source. Water provision from this Sim Drinking Water Supply scheme (as it was named) was extended (on request) to a neighbouring downstream village called Dandathok,Footnote9 whose residents relied on distant traditional water sources that they shared with neighbouring villages. Although village-level data are not available, with over 200 houses Dandathok is the largest settlement in Ward 7 of Lamatar and is known as an affluent village. Its residents are involved in farming and cattle rearing; supplying milk and vegetables to the growing population and neighbouring urban areas makes for a reliable business. Many inhabitants have new urban ‘office-based’ occupations. Only around five per cent of the residents in Dandathok, mostly Dalits, rely on manual labour for their livelihoods. In sum, with increasing in-migration, the population of Dandathok is growing and water demands are increasing.

After a few years, the upstream villagers of Ward 7 realised that it was not a wise decision to ‘share water’ with an expanding Dandathok. The Sim water supply was stopped, and Dandathok villagers accepted this decision. It was the prerogative of the uphill villagers to decide to share (or not) ‘their’ water source through the rule of prior water use rights. We contrast this story with another event, which shows that historical prior-use rights do not work for the Dalits.

Having briefly experienced a reliable piped water supply, Dandathok residents knew that the only reliable solution was to secure water access by staking a claim to a water source. The residents got together to form an informal water user committee and intensified the search for a more reliable water supply. They approached a non-governmental organisation (NGO), which offered technical and financial support, provided the following criteria were met: an undisputed and reliable water source, the requisite number of water-user households, an upfront cash contributions to the scheme’s construction costs, and agreement of full responsibility for operating and maintaining the scheme. Dandathok residents identified a spring source, Raksidol, which originated in the uphill Patle community forestFootnote10 () and was known to have a reliable annual discharge. The prior-users of this spring outlet were Dalit (Sarki) residents living in Tehrabise hamlet, upstream of Dandathok.

There are about 35 Sarki households living in Tehrabise hamlet, who have been resident here for as long as they and other settled Lamatar residents can recall. Unlike higher-caste residents, most Sarki households in Tehrabise have only a small plot of land. Only a few have small agricultural land-holdings. As determined in the caste order, Dalits in Nepal tend to own very little or no land (see note 7). The traditional caste-determined occupation of the Sarkis was shoemakingFootnote11, which no longer sustains in a modern economy. In the recent past Tehrabise residents, both men and women, worked as daily agricultural wage labourers. Following the rapid conversion of agricultural land into residential plots in the valley, many of them are now construction workers. Options for work are often limited by caste prejudices. According to a female Dalit resident of Tehrabise:

A few from our village were selected for the position of guard cum helpers in a nearby school.Footnote12 However, local higher-caste residents complained to the school management to not appoint Dalits. We lost these jobs to other higher-caste people.

Despite such issues, access to water had not been a problem for the Dalit residents of Tehrabise who live in two neighbouring smaller hamlets (Tole Footnote15 1&2, see ). Water from the Raksidol spring fed a traditional stone spout, providing reliable water for drinking and other domestic purposes. The overflow continued downhill, flowing into an irrigation canal used for downstream paddy fields. Additionally, the Sarki community living in Tole 2 of Tehrabise hamlet had access to another spring source (known as Kalidevi), located on the boundary between Tole 2 of Tehrabise and Thakuri Gaun, an upstream higher-caste hamlet in Sisneri village. The Thakuris of Thakuri Gaun unwillingly shared water with Dalits, a practice contrary to caste norms of pollution and purity.

The higher-caste, relatively well-endowed residents of Sisneri are also elected members of several local government organisations. This privileged position enabled them in the mid-1990s to allocate village development funds to the construction of piped household water supply schemes from spring sources originating in the Patle Community Forest. These schemes provided individual household connections in all hamlets in Sisneri, including Thakuri Gaun. Five public standposts were also provided in the neighbouring Tole 2 of Tehrabise. The Dalit residents of Tehrabise saw no reason to question this development. They had been provided (free of cost) with public standposts, which meant that they no longer had to keep distance from the higher-caste Thakuris, while fetching water from the Kalidevi spring. Little did they know that this was the start of stark changes in their water security.

Soon after the above developments in Sisneri, Dandathok residents formally registered their community organisation as the Raksidol Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation User committee (RDWSSC).Footnote16 They identified the Raksidol spring as an uncontested water source and addressed all other formalities outlined by the supporting NGO. A member of RDWSS recalled: ‘The population in our village did not match NGO norms of a ‘beneficiary community’, hence we included households from a village across the stream as water users’.Footnote17 The decision of Dandathok residents to include higher-caste households from a rather distant village, instead of including the Dalit households in Tehrabise residing close to the Raksidol spring, suggests a conscious political strategy to avoid any possible prior-use right claims.

Lack of secure access to water was key in bringing together an otherwise diverse Dandathok community. An elderly resident in Dandathok donated land needed for the scheme (water supply tanks). The community agreed to contribute financially and through labour inputs, with technical and additional financial support from the NGO, and ‘additional households’ were conveniently identified to meet the criteria of number of users. Tehrabise residents were unaware that a committee, named after the spring source that was traditionally ‘theirs’, had been formally registered. This decision had been approved by the Patle Forest Committee, headed by higher-caste Sisneri residents.

Lamatar residents mentioned that during the Maoist conflicts (1996–2006), non-Dalit Maoist leaders of Lamatar had encouraged and facilitated the Dalits from Tehrabise to ‘enter’ non-Dalit households, defying an age-old practice of social exclusion. Both Dalit and non-Dalit respondents of Lamatar stress that exclusionary practices of untouchability no longer apply. Current policy guidelines in Nepal specify mandatory equitable representation (of the marginalised) in village-level political and governance institutions. For example, the Community Forest User Groups (CFUG) management committee must include at least 50% female representatives as well as a proportionate representation of poorer, lower-caste groups, minority ethnic groups and indigenous people. The Patle forest committee also includes two Dalit representatives from Tehrabise. Yet, it is evident from the above examples (and several others, as we will note below) that these Tehrabise Dalit representatives were not involved in decision-making about this very institution and that caste divides still operate, albeit in different ways.

A higher-caste resident of Sisneri, a former elected local government representative and currently member of the forest users’ group, explained:

Tehrabise residents had been using this (Raksidol) spring. We assumed that the RDWSSC committee had consulted with the Sarkis of Tehrabise and provided the approval. In fact, we assumed that this scheme would also improve water infrastructure for the residents of Tehrabise. We thus supported it. But, as is evident now, it seems that [Dalit] members from Tehrabise have been unfairly treated. It appears that no negotiations and agreements were made with them, when the source was taken over by the RDWSS.Footnote18

Processes of exclusion

When construction of the RDWSS scheme started, a few Tehrabise villagers tried to contest this development. However, these contestations were scattered and ineffective, leading RDWSSC to state that there had been no counter-claims by Tehrabise residents. Class burdens derived from caste-inequalities continue to limit the agency of the Sarkis in Tehrabise. Simply put, organising for water is at odds with their struggles of everyday life. Further, challenging the authority of higher-caste groups is something that the Dalits are not used to. A Sarki resident of Tehrabise in his early-twenties explained:

Two decades ago, most elders and adults [in our community] were uneducated. Discrimination by caste was prominent. None [among us] would dare to raise a voice. If someone among us attempted to confront the higher-caste groups and claim for our rights, we would [in fear] distance ourselves from such claims.Footnote19

In 2008, the RDWSSC managed to get additional funding from another NGOFootnote22 to repair the Raksidol scheme. The repair work included enlargingFootnote23 the water intake. During this re-appropriation of the source, Tehrabise villagers managed to come together, but it was clear that they had now lost their prior-use rights to the Dandathok residents. According to a RDWSSC member:

Tehrabise residents requested for water. The request was for an independent scheme, a one-inch diameter water pipeline diverted to Tehrabise directly from Raksidol. We did not agree to this, but we agreed to provide a tap drawn from our main pipeline [… .].Footnote24

A Tehrabise resident explains:

Initially, Dandathok had agreed verbally to give us a one-inch pipeline outlet from the Raksidol spring. Had that decision been written down, they would not have been able to deny this. [… .] We have this weakness. Voice raised by a few individuals will not be taken seriously. But here only a few raise their voice. Most people in our village did not show concern nor raise their voice. [… .] We would rather go to fetch water in other villages. When RDWSS users come, they come as large group. They argue and often dismantle our pipes. If there were people here who could debate and tackle them, we could have obtained our share of water.Footnote26

It is evident that the claims on water have now changed hands. RDWSSC states that Tehrabise residents relied on and used the stone spout (fed by the spring), not the spring itself, and denies the latters’ claims for prior-use rights of the Raksidol spring. Meanwhile, water no longer flows from the stone spout that Tehrabise had historically used. A woman from Tehrabise: ‘When there were no obstructions [intake of RDWSS], the discharge of the stone spout was large. [… .] We had accessed this water since generations’.Footnote27 RDWSSC admitted that, although Raksidol spring yield has declined over the years, until the water flow drastically declined after the earthquake in 2015, it had exceeded their water demands.Footnote28 Yet, they denied access to Tehrabise and say, ‘Those Sarki people do not ask our permission to take water. When water is not sufficient for us, we simply dismantle their pipes’.Footnote29

Hydro-social dynamics of exclusion and water (in)security

As Dandathok continued to expand and the demand for water kept growing, the Committee innovatively expanded and maintained the scheme. Around 2008, they started collecting an annual fee (US$ 4.84Footnote30) from water-using households and charging new in-migrants an additional membership fee (US$ 48.6). In 2013, in exchange for a material support for maintenance of RDWSS by a commercial housing developer, they allowed the former to use Raksidol water. Additionally, in 2015, they agreed to share the spring water with the housing developer, in exchange for significant financial contributions to improve the source (and thus RDWSS). The Committee also discussed plans to provide all Dandathok users with private household connections for an additional fee. However, the 2015 earthquake, which caused a drastic decline of water flow from the Raksidol spring, resulted in these plans being shelved. RDWSSC has added one additional intake from the spring. Several households in Dandathok have invested in dug-wells, as has the housing developer, who has sunk dug-wells and a deep bore-well. In other words, capital can offset water insecurity in Lamatar village.

Since the earthquake, RDWSSC closely monitors any damage to the input pipelines by Tehrabise villagers. In desperation, Tehrabise Sarki villagers offered to become new formal members of the RDWSSC, but were told that they would need to ‘pay the same rate as new migrants to get water’, forgetting, as one Sarki respondent said, ‘that it is our water that they now control!’Footnote31 In these unequal contestations for water, the Tehrabise villagers are unable to do anything more than informally ‘steal’ (according to the RDWSSC) water from the Raksidol spring source. Accessing water in this way is unreliable and costly. The Tehrabise residents now mainly rely on the few public taps provided long ago from the Kalidevi spring, which, however, also has largely declined ().

Given an increasing water insecurity, Tehrabise Sarki villagers started requesting the Patle CFUG management committee for a new water source. After years of being ignored, a Tehrabise Sarki resident, who returned from working in a Gulf country and is better-off, took the lead to renegotiate for water. He explained:

Being a Dalit settlement, our village is disregarded. [… .] Nobody here could demand water. I have been working to improve our water supply for seven years. In our village people depend on daily wages and cannot spend time or money on negotiating for water.Footnote32

No one in Tehrabise is contesting this development, even though everybody knows that this scheme is only rhetorically theirs. Women from Tehrabise say: ‘The house-owner has hired one of our villagers as a guard, to fill the private tank and to water the plants on his land. After all this is done, there is hardly any water left to share’.Footnote36 As water insecurity intensifies, Tehrabise Sarki villagers are left competing with each other over water from the various public taps. Many are compelled to access water from villages further away, where caste dynamics still persist. According to a woman from Tehrabise:

Few days back, children from our village went to fetch water from a village of higher-caste households [… .] They were harshly scolded, humiliated and told never to come again to fetch water. We know that, compared to what we experienced in the past, the situation has changed, but this does not mean caste-based discrimination of Dalits has ended here, or in Nepal.Footnote37

Table 1. An overview of the hydro-social dynamics and exclusion of Dalits in Lamatar.

Discussion and conclusion

The case of Lamatar, an urbanising village in Kathmandu Valley shows how, as water becomes contested in the peri-urban space, access to water, the ability to claim it, contest its uses, and take decisions on it varies significantly for different individuals and groups. The reshaping of place from rural to peri-urban has been particularly burdensome for the Dalits of Tehrabise. They lost their reliable water source and are unable to exercise their prior-use rights to water. This is compounded by their relative inability to invest in new infrastructure and systems, as well as their socio-political inability to negotiate for water, as they lack access to the new drivers, managers and financiers of water services and infrastructure.

This does not just ‘happen’, but is caused by the fact that caste continues to define water norms, decision-making processes and governance in Lamatar. As argued by Pariyar and Lovett (Citation2016, 134), while there is ‘some relief from discrimination … caste still remains prominent in the lives of Dalits in Nepal’. The intersection of caste-based exclusions and hydro-social processes is evident in how the various claims, contestations and eventually requests by the Dalit residents in Tehrabise to reverse the appropriation of ‘their’ water is continually ignored and overlooked. As we note, the Dalit residents of Lamatar could not unite and organise to oppose against the water appropriations, which made it even easier for the higher castes to ignore the claims and requests made by the former. Despite being historically settled residents, they found little to no support or solidarity from the higher-caste community in these competitions for water security.

Regardless of the fact that the Tehrabise Dalits are (formally) members of the community forest management committee, they were an excluded minority. Clearly then, official policies of representative governance and for social inclusion hardly define everyday ‘relational-dialectical’ relations around water (Linton and Budds Citation2014). Dalits in Lamatar continue to be physically, socially and politically isolated from the ‘community’ and governance structures. Thus, as Khanal, Gelpke, and Pyakurel (Citation2012, 155) observed, the ‘adverse effect [of caste] … continues to be observable … in the lives of Dalits’. Indeed, the structural, internal disadvantages (Sen Citation2000) – the historical social, economic and political disadvantages that caste endows on the Dalits – stand firmly in the way of Dalits’ ability to reclaim their rightful place as equal citizens in Nepal’s new inclusive, democracy. Although Dalits have become relatively better able to voice their water rights, in Lamatar their weak economic position remains a major constraint in materialising their rights and contesting exclusion and water insecurity. As Bownas (Citation2015, 422–423) notes, the success in the struggle against caste-based discrimination practices in Nepal is ‘very fragile’ as the ‘functional separation of the economic spheres of Dalits and higher castes’ is growing.

It is in relation to continuously evolving socio-economic, political and institutional contexts, Cameron (Citation2005) has emphasised that anthropological approaches to caste based on religious and ideological dimensions of purity and pollution confine our understanding of the lived realities of everyday caste hierarchy and how these reproduce, challenge and change people’s agency that determines access to and control over resources. Our analysis of the processes and mechanisms of water governance provided fascinating deeper insights on ‘the problem of intersectional marginalisation’ (Bownas and Bishokarma Citation2018, 14) and evolving practices of caste-based exclusions experienced by Dalits in peri-urban contexts with increasing competition for water. As seen in Lamatar, with Dalits remaining unable to influence and mobilise socio-cultural, economic and political processes and relationships that determine ‘bundles of rights’ and ‘bundles of powers’ (Ribot and Peluso Citation2003), caste-based domination and exclusion persist in more subtle ways than the traditional, explicit forms of untouchability or inter-personal discrimination. Furthermore, our findings show that without critical attention to the practices and processes of making resource-related decisions and their implications for different social groups, community-centred approaches, despite bureaucratic reforms, can reproduce caste-based exclusion and inequalities in the changing socio-political, institutional and economic contexts.

Our findings are relevant for ongoing attempts to reframe water governance and water policy in Nepal. Firstly, recent studies on water in Nepal argue that community-centred approaches are more likely to amicably resolve water-related conflicts, improve water management and ensure a water-secure future (Biggs et al. Citation2013, 392). This is pointed out in the context of changes in governing systems, legal arrangements, bureaucratic reorientations and institutional restructuring (Upreti Citation2007; Biggs et al. Citation2013). While we do agree that local communities should participate in water governance, our findings point to the need for a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes a ‘community’. Given the entanglements of class and caste in Lamatar, our findings pose serious questions on what makes for a local community, and who is excluded and/or included in positions and processes of community-based resource governance and management (see also Udas, Roth, and Zwarteveen Citation2014).

Secondly, our findings show that it is not possible to transform deep-rooted practices and experiences of exclusion by formal, legal-bureaucratic tinkerings of change, such as declaring caste-disparities illegal or announcing and putting in place affirmative policies of representation at various institutional levels. Thus, while the official intent and related policy measures to include Dalits are an important first step (Purkoti et al. Citation2009), a ‘thicket of informal behaviours and deep-seated norms and values and networks … stand between formal policy statement[s] and … actual implementation’ (Bennett Citation2005, 2). More is needed than just affirmative action in policies and institutions to transform entrenched inequalities and injustices. Concurring with Upreti’s (Citation2007) analysis, we find that, in Nepal, water management and governance policies and strategies lack attention to systemic social, historical, cultural and economic entanglements. With Bennett (Citation2005, 42), we would emphasise that progressive reform policies and formal institutions crafted at high government level must have roots on the ground, especially at district level and below. It is in the local context that formal institutions ‘interact with the dense network of informal systems of behaviour and values’, as ‘the influence of these informal institutions can be especially strong in changing patterns of exclusion based on social identity’. In peri-urban spaces, a lot is changing: institutions, actors, networks, social and political connections, economic contexts and realities and yet certain injustices appear difficult to reverse. This necessitates a better understanding of existing and newly emerging dimensions of injustices and how these hit some more than others.

In sum, although caste-based discrimination has been formally abolished and the inclusion of Dalits into social, political, and institutional spheres identified as political priority, their position has not significantly changed in Nepal. Exclusion continues for Dalits in multiple new ways. In this paper we focused on how exclusion persists in relation to water. In the upheaval of urbanisation in Nepal, it is easy to disregard exclusion as ‘inevitable’ and ‘normal’. This is precisely why delicate nuances of exclusion remain poorly understood and researched. We emphasise the need to critically analyse evolving constellations of actors, agencies, and institutions, and the processes and mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion in peri-urban spaces, to discover in such fluid spaces the potential for transforming and reversing deep-rooted historical inequalities and injustices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anushiya Shrestha

Anushiya Shrestha is a PhD candidate at the Department of Social Sciences, Wageningen University, Netherlands. Her research interests include critical analysis of policies and practices around changing resources use and management, with a focus on peri-urban land and water issues.

Deepa Joshi

Deepa Joshi is Honorary Research Fellow at Coventry University, United Kingdom. A feminist political ecologist by training, her research has analysed shifts in environmental policies and how these restructure contextually complex intersections of gender, poverty, class, ethnicity and identity. Her interests lie in connecting gender and environmental discourse to local capacity building initiatives and advocating for policy-relevant change across developmental institutions. She has worked primarily in South Asia, and to a lesser extent in South East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Her published research presents ethnographic analyses of how inequality is reiterated and experienced across institutions and processes of policy-making, in policies per se and in implementing institutions at scale. Email: [email protected]

Dik Roth

Dik Roth is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology of Development and Change, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. Among his research interests are the anthropology of law and policy, legal plurality and complexity, property rights and justice, natural resources and resource conflicts, with a focus on land and water. His regional research focus is on South and Southeast Asia, and the Netherlands. He is editor-in-chief of the Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Caste is an elaborate traditional system of social stratification that combines elements of occupation, endogamy, culture, social class, tribe affiliation and political power. Each caste is further divided into sub-castes, which are often used as surnames (for Dalit castes, sub-castes, surnames and traditional occupations, see Bhattachan, Sunar, and Bhattachan Citation2009, 48–49).

3 Varna is the basic stratification of the caste system, which divides society into four layers: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Sudras. According to Pariyar and Lovett (Citation2016, 135), ‘tasks assigned to the Dalits are considered to be too ritually polluting to merit inclusion within the traditional Varna system and so the Dalits experience social exclusion’.

4 Prior to restructuring of the local government units in 2017, the Village Development Committee was the lowest local government unit, and was administratively divided into nine wards.

5 Claims for rights to use and make decisions related to a water source on the basis of historically being the prior user(s) of it.

6 It hierarchically organised Nepali caste groups into four broad categories: (1) Tagadhari (wearers of sacred thread); (2) Matwali (liquor consuming castes); (3) Pani nachalne choi chito halnu naparne (impure but touchable castes); (4) Pani nacalne choi chito halnu parne (untouchable castes). The fourth are referred to as Dalits or untouchables (with heterogeneity and hierarchy within the group) in present Nepali society (Dahal et al. Citation2002).

7 Nepal has a long history of feudal land governance. Although land reform began in the early 1950s and remains a repeated political commitment, for lack of political will there has not been any real change so far. Compounded by a discriminatory and strictly hierarchical society, landlessness among Dalits has historically been, and remains, far above the average of Nepal (see Wickeri Citation2011; Khanal, Gelpke, and Pyakurel Citation2012).

8 After two rounds of Jana Andolan (people’s movement), in 1990 and 1996-2006.

9 This includes several hamlets, including one of 16 Dalit households. Uphill villagers commonly refer to the area as Dandathok, one of the hamlets.

10 Dandathok belongs to the Padali Community Forest User Group (CFUG). Raksidol spring now lies in Padali CFUG after GPS-based boundary delineation in 2016.

11 Among Dalits, the titles (surnames) correspond to their traditional occupations, e.g. Sunar (goldsmiths), Tamta (coppersmiths), and Sarkis (shoemakers). There are many sub-clans and sub-castes, so a social hierarchy exists amongst the Dalits themselves, even though they are all considered untouchable and impure (Dahal et al. Citation2002; Bhattachan, Sunar, and Bhattachan Citation2009).

12 An expensive private school with a secondary branch is in Sisneri since the late-1990s. The school management provided financial support to the school managed by Patle CFUG Committee and gained access to its water.

13 Interview, December 23, 2017.

14 Alcoholism was common among Tehrabise elders.

15 Tole refers to a small settlement within a hamlet.

16 No other community-managed drinking water supply in Lamatar has been formally registered.

17 Interview, April 5, 2016.

18 Interview, September 23, 2016.

19 Interview, April 7, 2016.

20 Interview, January 22, 2017.

21 Interview, January 18, 2016.

22 It worked in wards 1, 7 and 9 of Lamatar in two phases (2008-2011; 2011-2013). The first phase focused on improving drinking water supply in Dandathok.

23 The 1-inch main pipeline was replaced by a larger (1.5-inches diameter) pipe.

24 Note that there are 32 taps in Dandathok.

25 Interview, April 5, 2016.

26 Interview, April 7, 2016.

27 Interview, April 7, 2016.

28 They recall their water supply pipes were broken due to water pressure. RDWSS users also used this supply for construction of houses.

29 Interview, April 7, 2016.

30 December 2017.

31 Interview, August 28, 2016.

32 Interview, January 23, 2017.

33 He was in-migrating from USA and had bought over 0.6 hectare of land, earlier owned by non-dalits. The interview was with his brother, who took care of the property.

34 The rule under this informal resource governing practice is ‘right to water comes through right to forest’. Thus, to get the right to use water originating in Patle CF, in-migrants have to be a member of the Patle CFUG.

35 Most houses in Tehrabise were damaged by the 2015 earthquake.

36 Interview, September 10, 2017.

37 Interview, September 10, 2017.

References

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2010. Overview of Gender Equality and Social Inclusion in Nepal. Mandaluyong City, Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9092-198-1.

- Allen, A. 2003. “Environmental Planning and Management of the Peri-Urban Interface: Perspectives on An Emerging Field.” Environment and Urbanization 15: 135–147. doi: https://doi.org/10.1630/095624703101286402

- Bennett, L. 2005. “Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal: Following the Policy Process from Analysis to Action.” Working paper for Arusha Conference, New Frontiers of Social Policy.

- Bhattachan, K. B., T. B. Sunar, and Y. K. Bhattachan (Gauchan). 2009. “Caste Based Discrimination in Nepal.” Working Paper Series Vol III No 8, Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, New Delhi.

- Biggs, E. M., J. M. A. Duncan, P. M. Arkinson, and J. Dash. 2013. “Plenty of Water, Not Enough Strategy How Inadequate Accessibility, Poor Governance and A Volatile Government Can Tip the Balance Against Ensuring Water Security: The Case of Nepal.” Environmental Science and Policy 33: 388–394. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.07.004

- Bownas, R. A. 2015. “Dalits and Maoists in Nepal’s Civil War: Between Synergy and Co-Optation.” Contemporary South Asia 23 (4): 409–425. doi:10.1080/09584935.2015.1090952.

- Bownas, R. A., and R. Bishokarma. 2018. “Access After the Earthquake: The Micro Politics of Recovery and Reconstruction in Sindhupalchok District, Nepal, with Particular Reference to Caste.” Contemporary South Asia 27: 179–195 doi:10.1080/09584935.2018.1559278.

- Buhler, G. 1886. The Laws of Manu. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Butterworth, J., R. Ducrot, N. Faysse, and S. Janakarajan, eds. 2007. “Peri-urban Water Conflicts: Supporting Dialogue and Negotiation.” Technical Paper Series No 50. IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, Delft.

- Cameron, M. M. 2005. On the Edge of the Auspicious. Gender and Caste in Nepal. Reprinted in Nepal. Kathmandu: Mandala Publications.

- CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics). 2001. Statistical Year Book of Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: HMG.

- CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics). 2012. National Population and Housing Census (Village Development Committee/ Municipality). Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- Dahal, D. R., Y. B. Gurung, B. Acharya, K. Hemchuri, and D. Swarnakar. 2002. “National Dalit Strategy Report. Part I: Situational Analysis of Dalits in Nepal. Final Report.” Action-Aid Nepal, CARE Nepal and Save the Children US, National Planning Commission, Kathmandu.

- de Haan, A. 1998. “‘Social Exclusion’ An Alternative Concept for the Study of Deprivation?” IDS Bulletin 29 (1): 10–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.1998.mp29001002.x

- Devkota, P., ed. 2005. Dalits of Nepal. Issues and Challenges. Lalitpur: Feminist Dalit Organization (FEDO).

- Elliot, J. 2005. “Listening to People’s Stories: The Use of Narrative in Qualitative Interviews.” In Using Narrative in Social Research. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, edited by J. Elliott, Chap. 2., 17–35. London: Sage Publications.

- Gorringe, H., S. S. Jodhka, and O. K. Takhar. 2017. “Caste: Experiences in South Asia and Beyond.” Contemporary South Asia 25 (3): 230–237. doi:10.1080/09584935.2017.1360246.

- Gurung, H. 2005. “The Dalit Context.” Occasional Papers. Sociology and Anthropology 9: 1–21.

- Hall, D., P. Hirsch, and T. M. Li. 2011. “Introduction.” In Powers of Exclusion Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia Challenges of the Agrarian Transition in Southeast Asia, edited by D. Hall, P. Hirsch, and T. Li, 1–26. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Hickey, S., and A. du Toit. 2007. “Adverse Incorporation, Social Exclusion and Chronic Poverty.” CPRC Working Paper 81. Chronic Poverty Research Centre. ISBN 1-904049-80-X.

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2005. Dalits and Labour in Nepal: Discrimination and Forced Labour. Kathmandu: Format Printing Press.

- Joshi, D., and B. N. Fawcett. 2006. “Water, Hindu Mythology and An Unequal Social Order.” In The World of Water. A History of Water, edited by T. Tvedt, and T. Oestigaard, 119–136. London: I. B. Taurus.

- Kabeer, N. 2000. “Social Exclusion, Poverty and Discrimination: Towards An Analytical Framework.” IDS Bulletin 31 (4): 83–97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2000.mp31004009.x

- Kabeer, N. 2005. Social Exclusion: Concepts, Findings and Implications for the MDGs. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

- Khan, S., E. Combaz, and E. McAslan Fraser. 2015. Social Exclusion: Topic Guide. Revised Edition. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

- Khanal, K., F. S. Gelpke, and U. P. Pyakurel. 2012. Dalit Representation in National Politics of Nepal. Lalitpur: Nepal National Dalit Social Welfare Organisation (NNDSWO).

- Lakhani, S., A. Sacks, and R. Heltberg. 2014. “They Are Not Like Us” Understanding Social Exclusion. Policy Research Working Paper No. 6784, The World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.com/bitstream/handle/10986/17340/WPS6784.pdf?sequence=1.

- Lawoti, M. 2010. “Introduction to Special Section: Ethnicity, Exclusion and Democracy in Nepal.” Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 28 (1): 9–16. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol28/iss1/1.

- Leaf, M. 2011. “Periurban Asia: A Commentary on “Becoming Urban”.” Pacific Affairs 84 (3): 525–534. doi: https://doi.org/10.5509/2011843525

- Linton, J., and J. Budds. 2014. “The Hydrosocial Cycle: Defining and Mobilizing A Relational-Dialectical Approach to Water.” Geoforum 57: 170–180. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.008

- Long, N. 2001. Development Sociology: Actor Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Long, N., and A. Long, eds. 1992. Battlefields of Knowledge. The Interlocking of Theory and Practice in Social Research and Development. London: Routledge.

- Mehta, L., J. Allouche, A. Nicol, and A. Walnycki. 2014. “Global Environmental Justice and the Right to Water: The Case of Peri-Urban Cochabamba and Delhi.” Geoforum 54: 158–166. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.05.014

- Mehta, L., and T. Karpouzoglou. 2015. “Limits of Policy and Planning in Peri-urban Waterscapes: The Case of Ghaziabad, Delhi, India.” Habitat International 48: 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.008

- Muzzini, E., and G. Aparicio. 2013. Urban Growth and Spatial Transition in Nepal: An Initial Assessment. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Narain, V. 2009. “Gone Land, Gone Water: Crossing Fluid Boundaries in Periurban Gurgaon and Faridabad, India.” SAWAS South Asian Water Studies 1 (2): 143–158.

- Narain, V. 2014. “Whose Land? Whose Water? Water Rights, Equity and Justice in a Peri-Urban Context.” Local Environment 19 (9): 974–989. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.907248

- Narain, V. 2016. “Peri-urbanization, Land Use Change and Water Security: A New Trigger for Water Conflicts?” Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode Society & Management Review 5 (1): 5–7.

- Narain, V., and A. Prakash, eds. 2016. Water Security in Peri-Urban South Asia. Adapting to Climate Change and Urbanization. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Narain, V., and A. K. Singh. 2017. “Flowing Against the Current: The Socio-Technical Mediation of Water (In)Security in Periurban Gurgaon, India.” Geoforum 81: 66–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.02.010

- Nepali, G. 2018. “Discrimination on Dalit in Karnali and its Impact to Sustainable Development.” Research Nepal Journal of Development Studies 1 (2): 84–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.3126/rnjds.v1i2.22428

- Nightingale, A. J. 2002. “Participating or Just Sitting In? The Dynamics of Gender and Caste in Community Forestry.” Journal of Forest and Livelihood 2 (1): 17–24.

- Nightingale, A. J. 2005. ““The Experts Taught Us All We Know”: Professionalisation and Knowledge in Nepalese Community Forestry.” Antipode 37: 581–604. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0066-4812.2005.00512.x

- Nightingale, A. J. 2011. “Bounding Difference: Intersectionality and the Material Production of Gender, Caste, Class and Environment in Nepal.” Geoforum 42: 153–162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.03.004

- Pariyar, B., and J. C. Lovett. 2016. “Dalit Identity in Urban Pokhara, Nepal.” Geoforum 75: 134–147. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.006

- Pradhan, R. 2000. “Land and Water Rights in Nepal (1854–1992).” In Water, Land and Law. Changing Rights to Land and Water in Nepal, edited by R. Pradhan, F. von Benda-Beckmann, and K. von Benda-Beckmann, 39–70. Kathmandu: Freedeal.

- Pradhan, R. 2006. “Understanding Social Exclusion and Social Inclusion in the Nepalese Context: Some Preliminary Remarks.” Paper presented at the workshop Understanding Social Inclusion and Exclusion: Theories, Methodologies and Data organised by Social Science Baha and the Social Inclusion Research Fund Secretariat/SNV, Kathmandu, June 3.

- Prakash, A., and S. Singh. 2016. “Gendered and Caste Spaces in Household Water Use: A Case of Aliabad Village in Peri-Urban Hyderabad, India.” In Water Security in Peri-Urban South Asia. Adapting to Climate Change and Urbanization, edited by V. Narain, and A. Prakash, 187–207. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Purkoti, S. K., G. Pariyar, K. Bhandari, and G. Sob. 2009. Study of Reservation for Dalits in Nepal. Bakhundole, Lalitpur: Social Inclusion Research Fund (SIRF)/SNV Nepal.

- Ribot, J. C., and N. L. Peluso. 2003. “The Theory of Access.” Rural Sociological Society 68 (2): 153–181. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00133.x

- Sen, A. 2000. Social Exclusion: Concept, Application, and Scrutiny. Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and Lamont University Professor Emeritus, Harvard University. Social development papers No. 1 Office of Environment and Social Development, Asian Development Bank.

- Seur, H. 1992. “The Engagement of Researcher and Local Actors in the Construction of Case Studies and Research Themes. Exploring Methods of Restudy.” In Battlefields of Knowledge. The Interlocking of Theory and Practice in Social Research and Development, edited by N. Long, and A. Long, 115–143. London: Routledge.

- Sharma, S. 2003. “Water in Hinduism: Continuities and Disjuctures Between Scripitural Canons and Local Traditions in Nepal.” Water Nepal 9/10 (1/2): 215–247.

- Shrestha, A., D. Roth, and D. Joshi. 2018. “Flows of Change: Dynamic Water Rights and Water Access in Peri-Urban Kathmandu.” Ecology and Society 23 (2): 42. doi:10.5751/ES-10085-230242.

- Sunam, R. K., and J. F. McCarthy. 2010. “Advancing Equity in Community Forestry: Recognition of the Poor Matters.” International Forestry Review 12 (4): 370–382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.12.4.370

- Sunar, M. S., K. B. Bishokarma, S. Poudel, P. Nepali, B. K. Sushil, and A. Manabi. 2015. Human Rights Situation of Dalit Community in Nepal. Submission to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review of Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal for Second Cycle Twenty Third Session of the UPR Human Rights Council 2-13 November 2015. Dalit Civil Society Organizations’ Coalition for UPR, Nepal and International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN).

- Swyngedouw, E. 2009. “The Political Economy and Political Ecology of the Hydro-Social Cycle.” Journal of Contemporary Water Research and Education 142: 56–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-704X.2009.00054.x

- Thapa, D. B. 2015. “Struggling Against the Caste-Based Inequalities: A Study of Dalits in Devisthan VDC, Baglung, Nepal.” Master’s thesis, The Arctic University of Norway.

- Thoms, C. A. 2008. “Community Control of Resources and the Challenge of Improving Local Livelihoods: A Critical Examination of Community Forestry in Nepal.” Geoforum 39: 1452–1465. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.01.006

- Udas, P. B., D. Roth, and M. Zwarteveen. 2014. “Informal Privatisation of Community Taps: Issues of Access and Equity.” Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 19 (9): 1024–1041. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.885936

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2008. The Dalits of Nepal and a New Constitution. A Resource on the Situation of Dalits in Nepal, Their Demands and the Implications for a new Constitution. Kathmandu: United Nations Development Programme.

- Upreti, B. R. 2007. “Changing Political Context, New Power Relations and Hydro-conflict in Nepal.” Paper presented at the Nepal Water Security Forum organised by The Silk Road Studies Program, Uppsala University, Uppsala, March 27.

- van der Woude, A. 2016. “Changing Environment, Changing Waters: An Analysis of Drinking Water Access of Vulnerable Groups in Peri-Urban Sultanpur.” In Water Security in Peri-Urban South Asia. Adapting to Climate Change and Urbanization, edited by V. Narain, and A. Prakash, 208–232. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Vij, S., and V. Narain. 2016. “Land, Water and Power: The Demise of Common Property Resources in Periurban Gurgaon, India.” Land Use Policy 50: 59–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.08.030

- Wickeri, E. 2011. “Land is Life, Land is Power”: Landlessness, Exclusion, and Deprivation in Nepal.” Fordham International Law Journal 34 (4): 931–1040.

- World Bank. 2006. Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal: Summary. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design And Methods. Fourth Edition. Applied Social Research Methods Series Volume 5. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.