ABSTRACT

In post-war transitions, how do centre-periphery relations change, and what is the role of actors at the margins of the state in negotiating these changes? This article explores these questions by examining Nepal’s post-war transition following the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Agreement focusing on three borderland districts (Saptari, Bardiya and Dolpa). The article analyses contrasting dynamics in these districts to highlight changes in centre-periphery relations across several areas including state reform, the economy, and transitional justice. The analysis shows how post-war transitions often generate new forms of contentious politics, and how groups at the margins can push back against emerging political settlements to reshape politics at the centre. The ambiguities and contradictions inherent to these processes are explored, with state restructuring processes susceptible to elite capture, and re-balancing of power between centre and periphery also coinciding with continuing or increased divisions and inequalities within borderland regions.

Introduction

How are post-war transformations experienced and negotiated at the margins of the state? How do centre-periphery relations change in war-to-peace transitions? In what ways are borderland regions incorporated into post-war political settlements? What is the role of borderland brokers in these processes? This article explores these questions in the context of Nepal’s war-to-peace transition following the People’s War (1996–2006) and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed in 2006. Drawing on the perspectives of those living on the state’s margins, we show how post-war transitions have been negotiated in different ways in three borderland districts. In doing so we highlight the diversity of experiences of contentious politics and borderland brokerage in these three marginal spaces. This comparative perspective on borderlands aims to spatialise understandings of political settlements and state-society relations in the aftermath of war.

After situating our study of post-war Nepal within a wider theoretical framework, we provide an analysis of post-war dynamics in three borderland districts, with a focus on shifting centre-periphery relations: Saptari in the Eastern Tarai, Bardiya in the Western Tarai, and Dolpa in the Karnali region in the Northwest. This is followed by a set of comparative reflections, that aim to illuminate and explain subnational variation in post-war-pathways. We conclude by drawing out the wider implications of this analysis for the study of war-to-peace transitions.

This paper is based on research conducted in Nepal between January 2016 and May 2019. A total of 117 interviews with key politicians, civil society representatives, academics, officials, and businesspeople were conducted in three districts and Kathmandu by the authors and other research team members. A further 23 life history interviews were conducted with ten borderland brokers.Footnote1 The research was conducted at three levels. Firstly, key informant interviews were conducted in Kathmandu with politicians, civil society activists, academics and government officials in order to capture national level political change. Second, studies of three borderland districts were conducted to capture borderland perspectives which involved interviewing a cross section of individuals including civil society representatives, community leaders (especially those representing marginalised populations), businesspeople, local politicians and government officials. These interviews took place both in district centres and peripheral regions, to allow an exploration of uneven development processes within the borderland districts.

Thirdly, in-depth life history interviews were conducted with 10 Nepali borderland brokers; defined as individuals who come from, and remain connected to, borderland regions, and play a role in mediating between the centre and the margins. The selection covered men and women who played different kinds of brokering roles including, coercive, political, economic and social brokers. Writing the broker life histories involved reconciling brokers’ accounts of their lives with the contrasting narratives provided by other informants, which we achieved by triangulating findings with a wide range of respondents. The three brokers who are the subject of this article were selected because their lives, backgrounds and brokerage roles exemplify the diverse characteristics and practices of borderland brokers in the context of post-war change. Through these life histories, alongside the district and national-level research, we aim to show how post-war transitions were negotiated and contested in different borderland spaces, in relation to key arenas of struggle: state reform (Tula Narayan Shah in Saptari), transitional justice (Bhagiram Chaudhary in Bardiya), and economic development (Angad Buda in Dolpa).

Centre-periphery relations and Nepal’s post-war transition

Spatialising post-war transitions

Recent research on political settlements has focused attention on the role of political coalitions, informal networks and bargaining processes in shaping war-to-peace transitions (Bell and Pospisil Citation2017; Cheng, Goodhand, and Meehan Citation2018; World Bank Citation2018). This work shows that post-war conflict and instability are likely to occur where there is a misalignment between formal institutions and the underlying configurations of power (Cheng, Goodhand, and Meehan Citation2018). The starting point of this article is the foundational research on political settlements (Di John and Putzel Citation2009) drawing particularly on the work of Khan (Citation2017, 640) who understands political settlements as a ‘description of the distribution of power across organisations.’ This work, rather than seeing political settlements as the result of elite bargains, sees them as a reflection of the underlying configurations of power, linked to the formal and informal organisations that underpin elite influence (which may include corporations, political parties, political networks or civil society organisations).

We extend upon and nuance this work on political settlements by bringing it into conversation with questions of space, territory and brokerage (Agnew Citation1994; Elden Citation2013; Lefebvre Citation1991; Meehan and Plonski Citation2017). In doing so we move beyond a top-down statist perspective on post-war transitions, which is associated with several problematic assumptions; first, the idea that post-war settlements are primarily shaped by negotiations between national-level elites; second, that post-war transitions involve the steady diffusion of power outwards from centre to periphery; third, that borderland regions can be understood as marginal and unruly regions waiting to be pacified and integrated into the central state.

The literature on borderlands shows that far from being lagging regions, they are frequently key sites of political, economic and social innovation crucial to shaping the trajectory of post-war transitions (Goodhand Citation2008; Nugent Citation2004; Raeymaekers Citation2009; Wilson and Donnan Citation2012). Post-war transitions tend to be uneven and ragged processes and stability at the national level may be accompanied by violent contestation at the state’s margins. They frequently involve the oscillation of power between centre and periphery, in which political elites navigate and broker between centripetal and centrifugal forces, jostling for power and resources.

For the purposes of this paper, borderland regions are understood as zones straddling an international border (Goodhand Citation2018). We use the terms ‘margins’ and ‘peripheries’ to refer to regions that are geographically distant from the political and economic centre (in the case of Nepal, the Kathmandu valley). As we elaborate below, however, the lines between peripheries and centres are typically fuzzy, and centres and peripheries exist in a dialectical relationship. Furthermore, ideas about ‘centres’, ‘margins’ or ‘peripheries’ are best understood as socially constructed spatial imaginaries of how different groups view or claim territory. In this article, we use these terms to refer to geographically defined regions but acknowledge that these terms may be mobilised to reinforce certain assumptions about borderland regions or state margins (e.g., the idea that they are unruly or lagging zones).

Power shifts between centre and periphery are rarely contained within the borders of an individual state. Social groups divided by an international border may have more in common with those living across the border than with those at the centre; they may speak the same language and cross-border economic activity may be more intense. From the perspective of the central state, the political loyalty of borderland communities may be suspect – in Nepal, borderlanders living in the Tarai and along the northern border are often viewed as ‘un-Nepali’ by those at the centre. Therefore, post-war transitions take place within a regional context, and borderlands are enmeshed in complex social and geopolitical environments, which can lead to very different trajectories out of, or back, into armed violence.

Political intermediation, or ‘brokerage’, is central to our analysis. We understand brokers as key individuals who mediate power, resources or ideas between different places (Meehan and Plonski Citation2017; Wolf Citation1956). Brokers typically play an ambiguous role – seeking to balance the interests of different constituencies, whilst also pursuing their own agendas. We are interested in a particular sub-category of brokers called ‘borderland brokers’. These are individuals who mediate across the gaps between the central state and the periphery, and between national and local political elites. They may play a role in asserting demands of their borderland constituencies at the centre and mediating complex processes of elite bargaining. These brokers operate across a variety of arenas (political, economic, civil society) and engage in a range of strategies, which often shift significantly over time in response to wider political ruptures.

Three caveats need to be highlighted in relation to our borderland perspective. First, not all peripheries are the same – as this article shows, each periphery has its own social structures, configurations of power and dynamics of change. Our approach is comparative; we are interested in understanding variation and similarities across different state peripheries.

Second, we take a relational approach, which involves studying the dialectical relationship between centre and periphery, and how each co-produces the other. Just as borderland regions have been transformed by war, Kathmandu has also changed significantly, growing rapidly during this period (Ishtiaque, Shrestha, and Chhetri Citation2017; Upreti, Breu, and Ghale Citation2017). Simplistic divisions between centre and periphery break down when one studies the flows of people, commodities and ideas between the borderlands and the centre.

Third, borderlands are themselves highly differentiated – they are places of multiple boundaries – social and administrative – and the international border may not always be the most salient one in people’s lives. Spatial imaginaries are complex, contested and constantly changing. Borders are ‘ordering devices’ and, as explored below, internal borders linked to state restructuring may be as significant in shaping the lives of border communities as the international border.

However, with these caveats in mind, we believe there is strong merit in studying war-to-peace transitions from the vantage point of the margins. In developing spatial histories of borderlands, alongside individual biographies of brokers, we aim to bring questions of space, territory and agency into conversation with political economy research on political settlements.

Shifting settlements: Nepal’s post-war politics

Post-war transitions frequently involve a re-spatialisation of power. Borderland regions often play a central role in conflict and in the political wrangling for power that follows. In Nepal, borderland regions, particularly the Tarai, were key sites of violence during the Maoist conflict and have played an important role in shaping Nepal’s post-war political trajectory as we elaborate further below. The pre-war state in Nepal was highly centralised – underpinned by a political settlement in which Bahun-ChhetriFootnote2 groups controlled key institutions and the main sectors of the economy. The King and the military stood at the apex of this system. As Joshi (Citation2010, 93) notes, historically state-society relations were ‘largely extractive’ and the periphery was ruled through loyal intermediaries, a network of landed elites who served as agents of the state at the local level (Sugden Citation2013). Borderland populations’ relationship with the centre varied across different state margins. There are major differences between, on the one hand, peripheral regions where there is a high rate of exploitation as a result of adverse integration between the periphery and the twin centres of Kathmandu and New Delhi (as for instance in the case of the Eastern Tarai), and ‘marginal’ peripheries in which there is a relationship of neglect by the centre in terms of investment and surplus appropriation (as, for example, in the case of Dolpa), on the other (Blaikie et al. Citation1980).

As state-led modernisation gave way to a period of economic liberalisation, this in turn affected centre-periphery relations as growth and prosperity did not diffuse evenly. The benefits of the liberal market economy were concentrated in urban areas, particularly Kathmandu, whilst the burden of World Bank/IMF-driven structural reforms largely fell on rural areas (Deraniyagala Citation2005; Joshi Citation2010).

The war transformed Nepal’s political settlement and the distribution of power between centre and periphery. The Maoists mobilised peripheral groups around a discourse of exclusion, gender equity and citizenship. They challenged the feudal, ‘mediated’ state by targeting landlords and the local elites, transforming social structures and politics in the countryside. In Bardiya and other parts of the Western Tarai, for example, the targeting of feudal landlords created a new space for TharuFootnote3 political mobilisation (Fujikura Citation2013; OHCHR Citation2008). Besides the war, other forces contributed to shifts in the social structure that loosened patron-client relations. For example, in the Tarai labour migration and remittances fuelled new processes of accumulation and investment, including the purchasing of land by returned labour migrants, further diluting the power of feudal elites (see Sijapati et al. Citation2017).

The CPA of 2006 appeared to reflect and consolidate a radical power shift within Nepal. The new political settlement was to some extent horizontally inclusive, as it incorporated the Maoists and their diverse constituencies. But, the Interim Constitution of 2007 failed to incorporate the concerns of all groups, particularly the Madhesis,Footnote4 whose exclusion led to violent mobilisation in 2007 – the Madhesi andolan – which was followed by further unrest in 2008. The Madhesi movement opened up wider discussions around political inclusion in Nepal and led to the negotiation of a new constitution.

These uprisings created an opportunity for central elites from mainstream parties, who had significant ‘holding power’ (Khan Citation2010), to push back against Maoist-inspired reforms (Adhikari and Gellner Citation2016). The centrifugal forces unleashed by Madhesi identity politics, opened a space for the reassertion of the centripetal forces of state-building and centralised patronage.

After the election of a Constituent Assembly (CA) in 2008, constitutional negotiations centred on Madhesi demands for a radical restructuring of the state along federal lines – devolving power to provincial and local bodies and boosting representation of marginalised groups in the national parliament by allocating seats based on population rather than geography. Madhesis also demanded changes to citizenship laws, which discriminated against those who had family ties beyond in India. Discussions revolved around what powers should be devolved and the delimitation of internal boundaries.

These negotiations dragged on until 2012, leading to elections for a second CA in 2013, which resulted in significant losses for the Maoists and Madhesi parties. A new constitution was finally agreed after a ‘fast-track’ process of intense negotiations in 2015, in the wake of the devastating earthquake.Footnote5 These proposals were followed by the blockade along the southern border with India and violence in the Tarai, as some borderland communities felt the constitution did not address their demands on citizenship rights, proportional inclusion, population-based electoral constituencies, and the inclusion of three Eastern Tarai districts in Province 2. Local, provincial and national elections took place in 2017.

The new political settlement was shaped by growing geopolitical competition in the wider region. India sought to assert the interests of Madhesi parties in constitutional negotiations. The refusal by the Nepali leadership to accommodate India’s requests precipitated the 2015 economic blockade. For over four months, protestors in the Tarai, with the unofficial backing of India, enforced a closure of the main border crossings, blocking the transit of goods. This resulted in severe shortages of fuel, medicines and other goods, but also had the effect of generating a strong anti-Indian sentiment within Nepal and uniting the country’s leadership against Indian interference. The blockade thus resulted in stronger political ties and greater economic cooperation between Nepal and China (Sharma Citation2019) while the amendments to the constitution, despite accepting some of the demands of Madhesi parties, did little to address their main grievances.

The new constitution was criticised for reinforcing a centralised status quo (Jha Citation2018). Many borderland communities objected to revised citizenship laws and the newly demarcated provinces, whilst the constitution also eroded commitments to proportional inclusion, supporting the continued dominance of Bahun-Chhetri groups in the bureaucracy and the judiciary (Hutt Citation2020). While the constitution established a new federal system, devolving powers to the local and provincial levels, and leading to the creation of one ‘Madhesi-controlled’ Province (2) in the East, the Tarai districts were split across five separate provinces with only one lying wholly in the Tarai.

Roy and Khan (Citation2017) argue that the new federal structures will drive a major shift in Nepal’s political settlement, through the decentralisation of rents and the empowerment of ‘intermediate classes’ whose economic interests are not so clearly tied either to labour or capital.Footnote6 In the Tarai, this shift is manifest in growing middle-class mobilisation in opposition to high-caste domination (Basnet Citation2019). The decentralisation of resources is likely to have a significant effect on the dynamics of brokerage, with political disputes centring on the channelling and distribution of resources to the provinces and municipalities.

However, borderlanders may not necessarily be the principal beneficiaries of an ostensibly more inclusive and decentralised political settlement. There is a need for careful analysis of, and variation between, subnational politics and specifically the role of political intermediation in brokering tertiary political settlements (Parks and Cole Citation2010). Brokerage, involving the management of political coalitions and constituencies, has its own distinct characteristics and patterns across the three districts, which vary over time, linked to the destruction of pre-war social structures in wartime, the emergence of new elites, and new forms of post-war political mobilisation.

Claim-making and contestation: post-war change in the borderlands

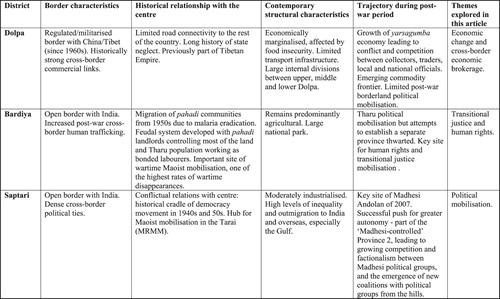

The three districts examined here were chosen because they capture contrasting features – allowing an analysis of variations relating to international borders (north and south); physical features/topography; resource endowments; histories of state incorporation; ethnic composition; experiences of wartime; and post-war political mobilisation (for a summary of the key features of the three districts see ).

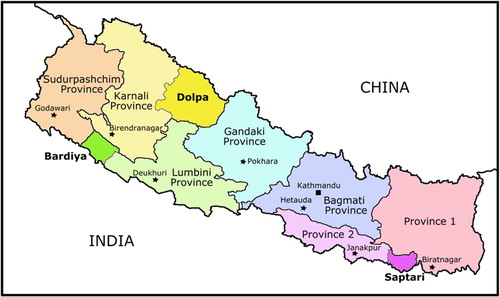

Nepal’s border regions are extremely varied. The border with India is a largely open and integrated and there is long history of exchange, shared cultural and economic interactions, cross-border movement and light regulation. In contrast, the border with Tibet in China, since the 1960s has been more highly regulated/militarised border, cutting off historic trade flows and interactions between people living on the Tibetan plateau (Bauer Citation2004; Karn Citation2018) ().

Figure 2. Map of Nepal showing new provincial boundaries (adapted by the authors from Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation).

Notes: This new map has been approved by the government after consultation with other political parties. It also reflects Nepal’s claim to a 370 square km strip in the far west region, which is disputed by India (see Shakya Citation2020).

Dolpa sits on the northern border with Tibet. With its high mountains, limited resources, sparse population and inaccessibility, from the perspective of the central state, historically the borderlands could not be profitably administered (cf., Scott Citation2010). Dolpa remains economically and politically marginalised, and chronically food insecure. There is a long history of state neglect and limited interaction with politicians and officials from Kathmandu. Since the 2010s, there have been efforts to build connectivity through improvements in road and rail infrastructure in China (and promised developments in Nepal), driving economic and political change, although progress has been less rapid on the Nepali side (Bauer Citation2014; Karn Citation2018).

The Tarai, in contrast to Dolpa, has several key economic hubs with a relatively well-developed industrial sector and transport infrastructure. Some regions of the Tarai have seen the emergence of a local elite and intelligentsia, and an associated presence of political parties, universities, business elite, and civil society organisations (Sugden Citation2011).

There are also significant differences within these borderland regions such as ethnic, caste, class and political differences between western and eastern Tarai (especially between the Madhesi and Tharu communities), which have been accentuated by the new federal provincial boundaries. In this article, we examine these contrasts by looking at Bardiya district in the West and Saptari in the East. In Dolpa, there are also topographical, social, linguistic differences – manifest in long-standing divisions between upper, middle and lower Dolpa.

Although all three districts straddle an international border, none are major crossing points or gateways for significant flows of people, money and commodities. Therefore, the ‘border effect’ (Gallant Citation1999) is more limited. This, of course, can change rapidly as regulation on one side of the border creates new ‘border gradients’ which generate opportunities for brokerage (Goodhand Citation2018). The significance of these borderlands as gateways can shift during war and peace – for instance, Bardiya was an important arms-smuggling route during the war, but its strategic value disappeared in the post-war period.Footnote7

In all three districts, the demarcation of provincial boundaries generated by the new constitution has been more salient than the status of international border. Madhesis, Tharus and groups living in the Karnali region sought to modify proposed boundaries to strengthen their political voice. Madhesis managed to carve out a ‘Madhesi’ province (Province 2), while civil society leaders in the Karnali region successfully blocked initial proposals for a large Province 6. Tharu calls for a province that grouped together Tharu-majority districts, however, were unsuccessful. While Madhesis are now ‘over-represented’ in the provincial assemblies, Tharus and JanajatiFootnote8 groups remain under-represented (Paswan and Gill Citation2018).

New provincial boundaries re-balanced centre-periphery relations, providing local leaders with a new platform to challenge the federal government. Following elections at the end of 2017 and the formation of provincial governments, there were disputes about the names of provinces, and the location of the provincial capitals. While many respondents in Saptari, for example, welcomed the election of local representatives, the new structure also led to new tensions and grievances (Karn, Limbu, and Jha Citation2018). In Rajbiraj, the district centre of Saptari, the subsuming of several rural Village Development Committees (VDCs) into the Rajbiraj municipality led to complaints from rural communities that it was now harder for them to access state services (Karn, Limbu, and Jha Citation2018). In Gulariya, the district capital of Bardiya, local businesses complained that the reduced role for district-level authorities meant that fewer people would need to travel there to visit district-level officials.Footnote9

In the next three sections, we provide a brief account of each district’s structural features and post-war dynamics, in addition to short vignette of a borderland broker who has played a role in mediating between centre and periphery.Footnote10 These three individuals are illustrative of the diversity of brokerage roles, the ambiguities and contradictions bound up with such roles and the differing sources of legitimacy that brokers draw upon. In Saptari, we examine the life of Tula Narayan Shah, an NGO activist who engaged first in civil society politics and then, unsuccessfully in formal party politics; in Bardiya, we explore the career of Bhagiram Chaudhary, a transitional justice leader, who mediated between local populations and international organisations advocating for transitional justice;Footnote11 and in Dolpa, Angad Buda, a district-level businessman and politician. The emergence of all three as key brokers is closely tied to shifting post-war settlements and the opening and closing of political, discursive and economic spaces at the subnational level, with each life history revealing the churning politics and constrained agency of brokers operating in these environments.

Eastern Tarai: Saptari – new contested political spaces

Saptari is a district in the Eastern Tarai. Our research focused particularly on Rajbiraj, a mid-sized town of 45,000 inhabitants situated on the Postal Highway, which connects the Eastern and Western Tarai. Rajbiraj was the earliest planned township in Nepal, becoming a municipality in 1959, and developing into a trading hub and an administrative and educational centre for the region. The town was also a political and intellectual centre, influenced by political currents and educational exchange across the border. It acted as a cradle for the democracy movement in the 1940s and 50s. During its heyday, the ruling class was composed of pahadi (hill people) and Madeshi feudal landlords. Economic decline set in with the construction of the East–West Highway, which bypassed the city, leaving it outside the main circuits of trade and exchange that integrated the Tarai with the hills.

There are centres and peripheries within the Eastern Tarai. Key nodes such as Biratnagar in neighbouring Morang district, that are privileged by their location and infrastructure, co-exist alongside marginal hinterlands such as Rajbiraj that are structurally disadvantaged by their location and adverse incorporation into local and national markets. Also, as the history of Rajbiraj demonstrates, these relationships are dynamic and changing; hubs can become peripheries due to shifts on both sides of the border. However, Saptari’s recent history suggests a more complicated story than one of simply gradual decline. The economic picture is certainly one of growing marginality: Saptari has a poverty rate of 40% (more than 1.5 times the Nepal average) (Open Nepal Citation2013), high levels of inequality in land ownership, and increasing outmigration from the rural areas – to India for seasonal work, but also increasingly to the Gulf states and Malaysia.

Notwithstanding this picture of economic stagnation, Saptari in the post-war period has remained a centre for the Madhesi movement. This can be explained by several factors, including the region’s longstanding history as a political and educational centre and the impacts of the Maoist conflict on local governance and identity formation.

The Tarai was not initially a Maoist centre but as the war intensified and expanded in scope, the Maoists’ reached out to Madhesi groups, creating a Madhesi Rashtriya Mukti Morcha (MRMM), initially under the leadership of Jai Krishna Goit, a native of Saptari, as part of their strategy to use identity politics to win the support of excluded communities (Nayak Citation2011; ICG Citation2007; Karn Citation2011). The Maoists also targeted feudal landlords and pahadi elites, leading to an outmigration of the latter. The Maoist focus on exclusion resonated with Madhesi groups even though the former’s anti-Indian rhetoric had little appeal. The Maoists, therefore, contributed to dismantling the patronage networks of the pahadi elites, increased the organisational power of Madhesi groups and, by advocating for regional and ethnic autonomy for historically marginalised groups, framed Madhesis’ expectations in the post-war period.

Following the end of the Maoist conflict, there was a growing divergence between Maoists and Madhesi interests. Saptari became an important centre for new political groups, including a breakaway faction within the Maoist movement, and for emerging armed groups after 2006. Historical and contemporary political movements in the Tarai have relied heavily on cross-border connections and political patronage from India. Similarly, Madhesi groups moved back and forth across the border to avoid state reprisals.

After the CPA, mainstream parties and the Maoists shied away from addressing the concerns of marginalised groups. The failure to address Madhesis’ demand for federalism and for the delineation of electoral constituencies in proportion to population in the draft interim constitution, triggered the Madhes Movement of 2007. Three weeks of violent protests forced the parties in Kathmandu to include the demands in the interim constitution (Lal Citation2013; Gautam Citation2008; Karn Citation2011). Sharma (Citation2019) argues that while the Movement forced the Nepali state to recognise the Madhesi community for the first time, India saw the rise of Madhesi forces as serving its own interests.

The 2015 protest and blockade, while demonstrating Madhesis’ capacity to inflict economic harm on the rest of the country, also highlighted the holding power of traditional elites, who were able to mobilise against Indian interference. While the compromise that ended the protests sanctioned the continuing dominance of traditional parties at central level, Madhes-based parties strengthened their position at the sub-national level, especially in Province 2.

Tula Narayan Shah, a leading Madhesi activist, played an important role in the emerging Madhesi movement after 2007. Born in Goithi in Saptari district, Tula was involved in student politics before moving to Kathmandu becoming an engineer and then a journalist. During his time in Kathmandu, he experienced discrimination, which motivated him to play a more active role following the 2007 Madhesi Andolan. He established the Nepal Madhes Foundation (NEMAF), a research and advocacy NGO, which produced reports and held workshops on Madhesi issues, and became a prominent media figure helping shape public discourse on Madhesi issues.

Although Tula had some influence on Madhesi politicians and constitutional negotiations (see Jha Citation2018, 40–41), his legitimacy was built upon maintaining a critical distance from party politics. His brokerage role was largely confined to triangulating between the mainstream parties, constituencies in the Tarai and international funders. This triangulation created tensions – at times he doubted whether he was making a genuine political contribution and regretted getting sucked into the bureaucratic world of donors and NGO politics. As Tula said in an interview in 2017, ‘[I sometimes think that] NGO work is only good enough to feed oneself, and I’m slowly and subtly getting coopted … So NGO activism and Kathmandu is now making me addicted in the way that college students get addicted to cigarettes’.

In 2018, Tula saw a new political opportunity emerging with the creation of the Madhesi-controlled Province 2, and decided to join the Sanghiya Samajbadi Forum Nepal (SSFN), the leading Madhes-based party at the time, convinced that he could have a greater impact there. This move proved short-lived, however, and less than a year later, he had resigned from the party, having failed to obtain a prominent position and becoming disillusioned by a perceived lack of commitment towards social transformation from his party’s leaders.Footnote12

Tula’s experience highlights the difficulties facing brokers who seek to carve out a niche in a fragmented and competitive post-war environment. Tula sought to influence the Madhesi agenda through a range of channels, but he ultimately found it difficult to inhabit any of the ‘deal spaces’ that emerged for long. His experience highlights the intense jostling for positions that characterised post-war Madhesi politics. It also shows the difficulties brokers face when converting influence in one sphere (civil society activism) into another (party politics).

In contrast to the other six provinces, which were won in 2017 by the CPN-UML-Maoist alliance, provincial elections in Province 2 were won by Madhes-based parties (the Rastriya Janata Party (RJPN) and Sanghiya Samajbadi Forum-Nepal (SSFN)).Footnote13 As a result, Province 2 has repeatedly clashed with the central government over the latter’s reluctance to devolve power and resources (Hachhethu Citation2018). The new provincial structures led to new strategies and alliances. New coalitions of caste, religious and ethnic groups emerged, with Yadavs, Muslims and Dalits positioning themselves in coalition against higher-caste Madhesis (Karn, Limbu, and Jha Citation2018; Basnet Citation2019).

The new political landscape also led to shifts in the strategies and coalitions pursued at the centre. The Nepal Communist Party (NCP), founded in 2018 from the unification of CPN-UML and the Maoists, made efforts to draw the RJPN and SSFN into the federal government. While the participation of Madhes-based parties in the federal government was short lived, the leader of SSFN, Saptari-native Upendra Yadav, was for a while Deputy Prime Minister, and used his position to gain greater access to resources and patronage, resulting in several new development initiatives in Saptari, such as the announced creation of an Institute of Health Science, the reopening of a local airport, and road repairs around Rajbiraj (Jha Citation2019). These developments are consistent with a noticeable shift in the rhetoric of Madhesi politicians in Rajbiraj during the 2019 elections. Madhesi politicians combined identity-based mobilisation with a growing focus on local development issues (Karn, Limbu, and Jha Citation2018). Attempts by the NCP to play Madhesi parties off against each other have generated tensions in Madhesi politics but have ultimately backfired, precipitating the unification of the two main Madhes-based parties in 2020 (Pradhan and Giri Citation2020).

Saptari’s post-war experience highlights the centrality of the margins to the renegotiation of political settlements following armed conflict. Through various waves of political mobilisation, Madhesi leaders in Saptari were able to shape the contours of the new constitution. While the new constitution opened political spaces and opportunities for brokerage, the benefits have largely been captured by more established and organised elites, limiting space for less powerful players like Tula Narayan Shah.

Western Tarai: Baridya – brokering identity and justice

Bardiya district in southwest Nepal has a poverty rate of 29% (around 1.2 times the national average) (OpenNepal Citation2013). The district came under the control of the British East India Company, following the Anglo-Gorkha war of 1814–1816 and was subsequently returned to Nepal in 1860. In the early twentieth century, Bardiya was heavily forested and was sparsely populated, mostly by Tharu people. From the 1950s onwards, malaria eradication projects and forest clearance facilitated the migration of Tharus from the Dang and Deukhuri valleys and Nepali-speaking pahadis into the district. Pahadi migrants were granted control over most of the land in Bardiya and large sections of the Tharu population became bonded labourers, known as kamaiya or domestic servants (kamlaris). When the kamaiya system was abolished in 2000, there were around 7,000 kamaiya households (some 34,000 people) in Bardiya district (Adhikari Citation2008, 51).

The district is dominated by the Bardiya National Park and the surrounding buffer zones, which come mostly under the authority of the central government. The Bardiya National Park forms a corridor of forested land across the border into India. Besides facilitating the migration of wildlife, the park also became an important corridor for Maoists and for smuggling arms and illicit drugs and timber over the border to India. Like Saptari, Baridya shares an open border with India and people cross daily to buy goods for personal consumption. There is a limited flow of licit trade with most goods crossing at the nearby town of Nepalgunj in Banke district.

Tharu activists began campaigns for land rights and an end to bonded labour in the 1990s. When the conflict broke out the Maoists quickly recognised them as a community that would be receptive to their message of social transformation (Adhikari Citation2014, 85). The Maoists invested heavily in Tharu mobilisation, rousing support by highlighting the need to abolish the feudal system and targeting local landlords, many of whom left the area during the war (Hoffmann Citation2015). Several Nepali and international NGOs became active in promoting the rights of the kamaiya, and some developed a co-operative relationship with the Maoists (Hoffmann Citation2015; Fujikura Citation2013).

Following the liberation of the kamaiya, a portion of large landholdings was distributed to them (around 0.17 hectares each). While this reform achieved a degree of re-distribution, many large landowners were able to hold on to large parts of their holdings and most kamaiya households remained dependent on landlords (Adhikari Citation2008). The kamaiya have continued to lobby government for additional support, intensifying their efforts in 2006.

Bardiya was heavily militarised during the war and had one of the highest rates of wartime disappearances. According to a report from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), over 200 disappearances took place during the conflict, with most occurring between 2001 and 2003 (OHCHR Citation2008). The high rate was caused partly by the fact that the local Tharu population were often assumed by government forces to be Maoist sympathisers, and partly due to emerging conflicts over land.

Transitional justice was one of the three pillars of the CPA – together with state restructuring and the integration of former combatants in the army – but, unlike the other two strands, has remained unimplemented and controversial. After 2006, representatives from the OHCHR and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) investigated human rights violations in Bardiya and the district became a hotspot for international engagement on transitional justice. Several local groups representing conflict victims were established and acted as brokers between international (western) and national-level transitional justice initiatives, whose approach was informed by a more legalistic understanding of justice, emphasising individual accountability and the pursuit of emblematic cases. This was in tension with local understandings of collective justice, economic compensation for victim and retrieving the bodies of the disappeared (Marsden Citation2015; Robins Citation2012).

Bhagiram Chaudhary, the local secretary of the Bardiya Conflict Victims Committee, was a key local figure in the transitional justice movement. His life history illustrates some of the neglected ideational and discursive dimensions of political settlements (Rocha Menocal Citation2015), and how brokers may play an important role in shaping these by adapting international or national discourses – or in this case, amalgams of the two – to serve the interests of their communities.

Before taking on this role in 2007, Bhagiram had been a Maoist cadre, working for the Tharuwan Rastriya Mukti Morcha and the Maoist student wing. During the war, Bhagiram became well known in the community and developed links with international organisations as a result of his brother and sister-in-law being arrested and subsequently disappeared.Footnote14

Bhagiram and the Conflict Victims Committee mobilised conflict victims, to pressurise the government to deliver on transitional justice commitments. International organisations like ICRC and Peace Brigades International supported Bhagiram’s role as a broker financially whilst providing a level of protection in a volatile post-war context (‘If I maintained a balance, I could reduce risks’). Like Tula, Bhagiram struggled to avoid co-optation during this period. He noted that human rights NGOs worked both to make money and to protect rule of law: ‘I don't like the first goal. But they are right in performing the second’.

The political salience of the transitional justice agenda waned over time.Footnote15 Little progress was made in delivering accountability for conflict victims, and the issue of transitional justice was not a strong feature during the 2017–2018 electoral campaigns in Bardiya. Bhagiram and others advocated social and economic rights to be more central to the human rights agenda (‘Only killing people is taken as violation of human rights. In this way, human rights activists … do not speak for those who live a life with a hungry stomach on the roadside’). Bhagiram’s experience highlights how local brokers can draw on a shifting set of discourses, networks and practices to vocalise the demands of their community, alongside their own interests. Just as the Maoists provided space for Tharu leaders to challenge the status quo, international and national transitional justice groups provided new opportunities for local brokers to influence the political agenda and access resources (cf., Fujikura Citation2013). This form of brokering shows how ideas and appeals to norms may be central to political mobilisation or resource allocation. While Bhagiram’s experience highlights the opportunities presented by this kind of discursive adaptation, it also shows how space for such ideas may rapidly close as funding dries up and as other priorities emerge.

Like Saptari, Bardiya has also been a centre of contestation of the emerging political settlement. In 2009, discussions at the centre around a new constitution provoked violent protests from Tharu groups who objected to what they saw as an attempt by Madhesis to subsume Tharus under the Madhesi identity and undermine their aspirations for a Tharu-majority province. Tharu protests ran alongside other groups of protestors calling for an undivided Far-West as well as those aggrieved at plans to combine what later became Provinces 6 and 7 into a single Province. While the government largely acceded to both these latter groups, Tharu protests were met with force. In 2015, Tharu protests in Tikapur grew violent and seven policemen were killed.

In the 2015 Constitution, Tharu-dominated districts were split between Provinces 5 and 7 and Tharu politics lost its distinctive thrust. Two key mergers of Madhesi and Tharu-led parties occurred in 2017 and following the elections, most Tharu leaders worked through Madhesi coalitions or joined mainstream parties. As in Saptari, political rhetoric around the 2018 elections moved away from identity-based mobilisation, towards a focus on development work.

In 2019, representatives from the NC and NCP lobbied for Bardiya and Banke districts to break away from Province 5 and join the Karnali Province, citing neglect within Province 5 and the long distance to the Provincial capital, a move that was opposed by the Madhesi parties (see Oli Citation2019).

The contrasting political dynamics in two districts in east and west Tarai illustrate how borderlands themselves are highly differentiated and how these divisions may be exploited by political elites at the centre to prevent contiguous blocks of opposition from emerging. Bardiya also shows that tensions between centripetal and centrifugal political forces are not limited to state reform but are also evident in the field of transitional justice. Borderland brokers engage with a shifting set of national-level actors and agendas to assert the interests of their communities, though their impacts may be fleeting as funding priorities and political discourses shift.

Northern periphery: Dolpa – a new commodity frontier

The sparsely populated, mountain district of Dolpa has a poverty rate of 43% (nearly double the Nepal average) and has been deeply affected by food insecurity (OpenNepal Citation2013; Karn, Limbu, and Jha Citation2018). The region previously formed part of the Tibetan Empire and, later, the Lo and Jumla kingdoms. Throughout its history, it has remained relatively autonomous and isolated from the rest of the country due to limited transport links (Bauer Citation2004, Citation2014). The district headquarters in Dunai and the airport in Juphal in mid-Dolpa are the district’s economic and political hub. People from Upper Dolpa travel for many days on foot to access state officials and basic services. Most villages in Upper Dolpa lack basic services, with the only available schools run by NGOs.

Since 2000, there has been a shift in traditional livelihood strategies with declining reliance on animal husbandry and a growth in trade of medicinal plants, particularly yarsagumba, a fungus that feeds on caterpillar moth larvae. The fungus has become a popular commodity (as an aphrodisiac and gift) in China and its price has increased significantly. Trade in yarsagumba was legalised in 2001 and has since become a key contributor to the cash economy in Dolpa. Shifting livelihood patterns have also been driven by growing regulation at the Chinese border, which began in the 1960s but became tighter in 2003/2004 and made traditional trading over the border into Tibet more difficult (Bauer Citation2004).

Research studies have estimated that Nepali harvesters receive around USD 59 million per annum from yarsagumba, making it Nepal’s third leading export earner. Dolpa produces the highest volume of yarsagumba in Nepal. Total production in Nepal is estimated to be around 14 times the official trade. Local traders receive around USD 10,000 per kg, while yarsagumba has retailed for as much as USD 140,000 per kg in China (Pyakurel and Smith-Hall Citation2018). It has been estimated that earnings from yarsagumba account for more than 70% of household income in Dolpa. Entire communities leave their villages to reach the collection areas during the harvest season, leading to the closure of schools and severely affecting the work of the local administrations (Pant et al. Citation2017). The rewards can be unpredictable, as demonstrated in 2019, when many pickers failed to clear their debts (Singh Citation2019). Most district-level politicians in Dolpa are heavily involved in the yarsagumba trade and many use political connections in Kathmandu to evade taxation. While, in the past, the Dolpa elite have invested capital in farming land, today’s yarsagumba revenues have been concentrated in hotels and residential property in Dolpa, Kathmandu and other urban areas.

Dolpa’s experience shows how the exploitation of high-value resources can transform a remote borderland region into a new commodity frontier – in this case re-orientated towards feeding the consumer habits of the growing middle classes in East Asia. The post-war period has seen a major shift in the ‘institutions of extraction’ (Snyder Citation2006). During the war, there was a rebel monopoly, which ensured a relatively ordered system of extraction and taxation. Local yarsagumba collectors paid tax to the Maoists who in return provided the collectors with security. This changed after the signing of the CPA, and the emergence of new governance arrangements around yarsagumba. This can be characterised as a more fluid ‘joint extraction’ (Snyder Citation2006) regime in which private actors negotiate with various state actors leading to growing competition over the regulation and distribution of rents. Dolpa opened to outsiders and became less tightly regulated, creating new conflicts between locals and outsiders from lowland areas. Conflicts over collection sites also emerged between collectors and local traders (Pant et al. Citation2017).

In response to these developments, the military and the police also made a more concerted effort to capture these rents. In the Shey Phoksundo National Park, which covers a large part of Dolpa, the authorities now sell permits to collect yarsagumba (RSS Citation2018). In 2014, violence erupted after local yarsagumba collectors in Lang were asked to pay new fees to collect yarsagumba in their communal lands. Twelve protesters were arrested and, according to reports, some of these protestors were tortured and one died (Gurung Citation2014). This incident illustrates how outsiders have sought to renegotiate the political settlement by increasing their control of rents, leading to violent contestation and highlighting emerging centre-periphery tensions.

The life of Angad Buda, a Dunai-based businessman and politician, illustrates some of the complex interactions between politics and business, and between centre and periphery in Dolpa.Footnote16 His history highlights some of the emerging tensions generated by the booming yarsagumba trade and development programmes in the district and how brokers have attempted to reconcile these external and internal pressures. He originally became involved in politics during the 1990 People’s movement when he was a student activist while studying in Kathmandu. He returned to Dolpa the following year and joined the Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP, the Royalist right-wing party). After a falling out with the RPP leader, he left and later joined the CPN-UML in 1998. Around this time, he began to concentrate on business, establishing a successful hotel and becoming involved in the yarsagumba trade.

In 2006, he considered a return to party politics, motivated by a desire to promote the interests of his community and to tackle corruption. His return to active politics was delayed by a lack of funding and his concern about becoming embroiled in potentially dangerous local political disputes. In 2009, he was elected District President of CPN-UML. In 2013, however, he felt betrayed after the party’s ticket in the second CA elections was sold to the businessman/contractor Dhan Bahadur Buda. Despite switching party allegiances to the Nepali Congress and maintaining good links with leading politicians in Kathmandu, he remained on the sidelines of district politics. Other local politicians viewed him with suspicion and his own economic position remained precarious. He experienced direct violence from political opponents and narrowly escaped with his life on one occasion. More recently he turned to the yarsagumba trade to bolster his income and suffered large losses. While he remains disillusioned by the state of politics in Dolpa (‘There’s not much one can expect in a country where politicians are contractors’), he is also committed to returning to the political fray, vowing to adopt a more cautious approach next time (‘I will tread with caution, [and] perhaps appear less as a threat to my rivals’).

Angad Buda’s life highlights some of the real dangers facing local leaders who become embroiled in politics. It also illustrates some of the ingredients needed by a successful local broker: ideological flexibility (moving between parties), money, and a willingness to engage in corruption and violence.

Dolpa’s post-war experience demonstrates how the growing market for yarsagumba has impacted upon social and political relations, cementing the position of local elites in mid-Dolpa, who have been able to use connections with political actors at the centre to exploit these emerging economic opportunities, and strengthen their position as brokers between the district and Kathmandu. Yarsagumba has led to new processes of accumulation and investment, providing start-up capital for new hotels in upper Dolpa and facilitating labour migration (Bauer Citation2014).

As in the Tarai, the elections and devolution of resources to local representatives have been largely welcomed. New politicians promised to use the emerging political system to overcome the severe logistical challenges that previously faced communities in Dolpa and hampered their ability to access basic services. While local people are generally hopeful that there will be greater scope to push back against state violations of the kind that occurred in 2014, the amalgamation of VDCs into municipalities has benefitted the more centrally located VDCs at the expense of more remote or rural ones, and large swathes of land remain under the control of central authorities (forests, national parks etc.), ensuring that valuable natural resources such as yarsagumba, timber and tourism permits remain out of reach of local bodies. Local people still lack representatives in the police, army or bureaucracy and four out of eight rural municipalities in Dolpa continue to execute their business via liaison offices in Dunai (Gautam Citation2020).

Conclusions: spatialising post-war settlements

Existing work on post-war transitions has tended to adopt a national perspective. Borderlands are frequently a blind spot – a blindness that is linked to a set of embedded statist reflexes, which view post-war settlements from the perspective of the centre, and see the primary post-war challenge as being how the centre can better integrate, incorporate and develop the periphery. In this article, we have shown how this perspective neglects the varied experiences of post-war ‘peace’ on the ground. We have argued for a more spatialised understanding of post-war transitions which recognises the uneven nature of these processes. We have analysed three border districts to explore sub-national variation in pathways out of armed conflict. The three brief borderland biographies presented in this article show that post-war transitions are frequently conflictual and violent processes. Conflicts that surface during these transitions are often rooted in processes and events that precede the war, linked to long-standing structures and policies of marginalisation and exclusion, or the adverse incorporation of peripheral communities into states and markets.

Post-war political settlements and borderlands

Political settlements are volatile and constantly ‘unsettled’ during post-war transitions, particularly in moments of rupture. In Nepal, there have been several key inflection points – including the CPA in 2006, the Madhesi andolan in 2007 and 2008, the 2015 earthquake and subsequent constitution – each of which generated important shifts in the political settlement. Although the CPA dispensed with the monarchy and key elites from the old regime, important members of the ‘old guard’ – including the military, the bureaucracy, the mainstream parties and the business elite – remained in the political coalition that emerged. Nepal’s post-war experience highlights how transitions out of war do not simply involve contestation between a ‘conservative centre’ and more ‘radical peripheries’. Within the peripheries, there are conservative forces, which were often silenced during the war but increasingly re-emerged in the post-war period to push back against emerging settlements.

We have shown that borderlands, rather than being marginal to post-war transitions, are often in fact central to these processes and can play a key role in shaping the trajectory of national-level political settlements. In the aftermath of war, borderland regions are often disruptive and transformative spaces, which mould emerging political markets at the national level. Our district studies have illustrated how the margins can shape political settlements in a variety of ways: the 2015 blockade shifting political coalitions at the centre; revenues generated by yarsagumba being channelled into Kathmandu; and the discourses of transitional justice and accountability being picked up and acquiring new meanings in the periphery, leading to new forms of claim-making at the margins. Borderlands are often key sites for varied forms of international engagement, whether for the promotion of western discourses and peacebuilding agendas (as highlighted by the life histories of Tula and Bhagiram), for Indian intervention (highlighted especially in the Saptari case), or for Chinese economic actors in the case of Dolpa.

Borderlands are inherently difficult places in which to develop stable coalitions, due to their cross-border dynamics and allegiances, relative inaccessibility, and internal divisions around class, caste and ethnicity. In Nepal these challenges were intensified by war, which heightened borderlanders’ demands for state reform and inclusion.

Rather than involving a steady diffusion of power outwards from the centre, as is often implied by mainstream accounts, post-war transitions are characterised by a constant oscillation of power backwards and forwards and post-war borderlands are places where centrifugal and centripetal forces converge and interact. As our ‘borderland biographies’ show, new demands and new spaces for mobilisation have emerged from the periphery. In Saptari, we have seen emerging identity-based demands for greater political voice and representation. In Bardiya, we have traced the emergence of new forms of mobilisation linked to questions of transitional justice. And in Dolpa, centre-periphery tensions coalesced around struggles for the control of revenues generated by yarsagumba and increasingly in relation to road building and development programmes. In exploring these different forms of mobilisation, we seek to illustrate the political, economic and discursive dimensions of post-war claim making and how these demands are managed by, and also shape political coalitions at the centre.

Although Nepal’s centre-periphery relations are likely to be transformed by the new federal system, federalism seems unlikely to deliver a straightforward transfer of representation and resources to the margins. Underpinning the debates and wrangling around federalism were underlying and spatialised power struggles between ‘centrists’, who tended to emphasise the developmental logic for federalism, and those for whom support for federalism was linked to issues of identity, voice and representation. To date it seems that the ‘centrist’ version has won out, reflecting how the underlying configurations of power had changed in favour of centripetal forces.Footnote17

In many respects, federalism has been less an instrument for the transfer of power and instead served more as a tool through which the centre has fragmented and diluted challengers from the periphery. The centre has also been able to use the under-resourced federal system as a tool with which to discredit borderland leaders and exploit over-inflated expectations, a tendency which may be exacerbated by poorly coordinated responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (Saferworld Citation2020).

It is too early to predict how federal reforms will shape centre-periphery relations and the dynamics of brokerage. However, our analysis suggests that political dynamics will vary in different borderlands – where for example, as in Province 2 the holding power of local elites is stronger and there is greater scope to resist the centralising tendencies of the mainstream parties or to negotiate better deals with national elites. Our analysis also implies that identity politics and political demands are likely to be undercut by competition for resources, in particular development programmes. Finally, our case studies suggest that local forms of elite capture may blunt aspirations for the federalism to increase voice and inclusion of borderland populations.

Post-war brokerage

We have argued that political intermediation is key to understanding the making and unmaking of post-war settlements. Peripheries are places of ‘friction’ where the central state meets resistance, and where distance and hybridity generates demand for brokers to mediate between borderland populations and the central state.

The brokers examined in this article each drew upon different discourses and sources of legitimacy to justify their roles – from justice and accountability in Bardiya, to political rights and representation in Saptari, to fair access to development and resources in Dolpa. In each case, the declining ability of these brokers to deliver on their promises – as political space, room for manoeuvre or external funding declined – led to a legitimacy crisis and a decline in the relevance of the broker in question. The three brokers have struggled with transitions into and out of party politics – legitimacy accrued, for example, via civil society activism or business, does not convert easily into status within formal politics, particularly in the volatile post-war period.

There is likely to be a shift from identity brokerage to a growing salience of ‘development brokers’ as the key concern of local constituencies will be to capture resources and programmes flowing from the central state and provincial level structures. Brokers with external linkages tend to have more bargaining power than those who derive their power primarily from local constituencies. For example, Bhagiram’s salience as a broker was greatest when he had the support of international organisations. Madhesi elites were most powerful when they could draw on the backing of India to act as a bulwark against mainstream party elites. Yet brokers who rely too heavily on international funding and support have limited long-term credibility or leverage in shaping political settlements – they lack the embeddedness, reliable backing or legitimacy to operate in the political marketplace for any length of time. Post-war politics creates new ‘deal spaces’ for borderland brokers to emerge, occupy these spaces and manage the flows of power, ideas and resources. While brokerage affords opportunities for these individuals to enhance their communities (and their own) prospects, their position is typically vulnerable, and their scope to influence wider politics is often fleeting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jonathan Goodhand

Jonathan Goodhand is Professor of Conflict and Development Studies, in the Department of Development Studies at SOAS, University of London, and an Honorary Professorial Fellow at the University of Melbourne, School of Social and Political Sciences. He is the Principal Investigator of a four-year Global Challenges Research Fund project ‘Drugs & (dis)order: Building sustainable peacetime economies in the aftermath of war’. His research interests include the political economy of conflict, war economies, war to peace transitions and the role of borderlands, with a particular focus on Central and South Asia

Oliver Walton

Oliver Walton is a Senior Lecturer in International Development at the University of Bath specialising in the political economy of war-to-peace transitions, NGO politics, conflict and peacebuilding. His research has focuses on the political economy of war to peace transitions, civil society, NGOs and NGO legitimacy. Recent work has examined the role of borderlands and brokers in post-war transitions in Nepal and Sri Lanka, and the role of alcohol in conflict-affected regions.

Jayanta Rai

Jayanta Rai is a PhD Candidate in Development Studies at SOAS, University of London. Her research examines the political economy of post-war state restructuring and federalism in Nepal. She has worked in the media field, reporting on a range of issues, including education, constitution making and federalism in Nepal, and for NGOs, advocating for indigenous and women rights; she was selected by the UN Voluntary Fund to be one of four representatives from Nepal to the United Nation Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in 2007. She has worked as a research consultant for the ‘Borderlands, Brokers and Peacebuilding’ project.

Sujeet Karn

Sujeet Karn is a senior researcher associated with Martin Chautari in Nepal and a visiting faculty at the Department of Social Work, Tribhuban University, Nepal. Sujeet’s research focuses on anthropology of violence, death and bereavement, borderland livelihoods and security in South Asia, Water Governance, Gender and Social Inclusion, and everyday Religion in the Himalayas.

Notes

1 The research was conducted as part of an ESRC-funded research project ‘Borderlands, Brokers and Peacebuilding in Sri Lanka and Nepal: War to Peace Transitions viewed from the margins’ (Ref: ES/M011046/1). The Nepal research team from Martin Chautari was led by Sujeet Karn and included Pratyoush Onta, Bhaskar Gautam, Madhusudan Subedi, Kalpana Jha, Sangita Thebe Limbu, Bhawana Oli, Ankalal Chalaune, Asmita Khanal and, Indu Chaudhari. We also draw on separate research conducted by Jayanta Rai as part of her PhD research project on post-war state restructuring and the political economy of federalism in Nepal.

2 Bahun and Chhetri are the two Hindu high-caste groups which have historically dominated the Nepali state. They constitute around 31% of the population.

3 The Tharu are an ethnic group that includes a number of communities living across the Tarai, accounting for 6.6% of the population. Tharu communities do not share a common culture or language; a common Tharu identity only emerged in the mid-twentieth century (Guneratne Citation2018).

4 The term Madhesi is a political or experiential term denoting the people living in the Tarai who feel discriminated against by a state dominated by hill castes (Hutt Citation2020; Karki Citation2019). A more restrictive definition identifies Madhesis as the Hindu caste groups in the Tarai sharing close cultural and linguistic ties with similar groups in neighbouring India, excluding Tharu and Muslim communities (Pandey Citation2017). Under this definition, Madhesis constitute around 20% of Nepal’s population.

5 For further discussion about the impact of the earthquake on the constitutional process see Hutt (Citation2020).

6 Khan and Roy estimate that this group make up around 30–40% of the society.

7 Interview with NGO representative, Gulariya, 21st February 2018.

8 Janajatis are not a cohesive group, but include more than 60 communities with different languages, cultures and distinct historical homelands. Janajatis have been traditionally marginalised from the state and denied access to resources, with the partial exception of Newars. Janajati groups (with the exclusion of Tharus) account for approximately 28% of Nepal’s population.

9 Interview with businessman, Gulariya, Bardiya District, 23 February 2018.

10 These brokers have been selected from a wider sample of ten life histories conducted in Nepal.

11 We provide fuller life histories of Tula Narayan Shah and Bhagiram Chaudhary in Goodhand, Walton, and Pollock (Citation2018).

12 Interview with Tula Narayan Shah, Kathmandu, 15 May 2019.

13 This was particularly the case in Saptari, where Madhes-based parties elected 5 of the 8 provincial representatives and won 10 of the 18 mayoral positions.

14 Interviews with Bhagaram Chaudary 25 June 2016, 6 May 2017, and 20 February 2018.

15 In 2020, the government sought to move forward with its transitional justice agenda although these moves have been heavily criticized by conflict victims, including Bhagiram Chaudhary (Ghimire Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

16 This account is based on interviews with Angad Buda in Dolpa (18 December 2016, 18 and 24 January 2017) and with other local politicians, officials, civil society activists and journalists.

17 At the time of writing (early 2021), the federal government has not devolved power on issues clearly established in the constitution. There has been substantial interference from the central leadership into provincial governments. Many commentators have argued that the federal government remains committed to weakening federalism and that the centralised structure of political parties limits space for provincial chief ministers to influence party decisions (Bhatt Citation2020; Shrestha Citation2020; Nepal Citation2020).

References

- Adhikari, J. 2008. Land Reform in Nepal: Problems and Prospects. Kathmandu: ActionAid. https://nepal.actionaid.org/sites/nepal/files/land_reform_complete_-_done.pdf.

- Adhikari, A. 2014. The Bullet and the Ballot Box. The Story of Nepal’s Maoist Revolution. Kathmandu: Aleph Book Company.

- Adhikari, K. P., and D. N. Gellner. 2016. “New Identity Politics and the 2012 Collapse of Nepal's Constituent Assembly: When the Dominant Becomes ‘Other’.” Modern Asian Studies 50 (6): 2009–2040.

- Agnew, J. 1994. “The Territorial Trap. The Geographical Assumption of International Relations.” Review of International Political Economy 1: 53–80.

- Basnet, C. 2019. “The Federal Socialist Forum: Incipient Middle Caste Politics in Nepal?” Studies in Nepali History and Society 24 (2): 355–380.

- Bauer, K. 2004. High Frontiers. Dolpa and the Changing World of Himalayan Pastoralists. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bauer, K. 2014. “High Frontiers: Dolpo Revisited.” Tibet Journal 39 (1): 157–181.

- Bell, C., and J. Pospisil. 2017. “Navigating Inclusion in Transitions from Conflict: The Formalised Political Unsettlement.” Journal of International Development 29 (5): 576–593.

- Bhatt, L. 2020. “Nepalma sanghiyaya: Biu ropiyo suntalako, phal phalayo bhogateko!” Ratopati, October 6. https://ratopati.com/story/149978/2020/10/6/nepal-federalism-debate-.

- Blaikie, P. M., J. Cameron, D. Seddon, and J. Cameron. 1980. Nepal in Crisis: Growth and Stagnation at the Periphery. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Cheng, C., J. Goodhand, and P. Meehan. 2018. Elite Bargains and Political Deals Project. Synthesis Paper: Securing and Sustaining Elite Bargains that Reduce Violent Conflict. United Kingdom Stabilisation Unit.

- Deraniyagala, S. 2005. “The Political Economy of Civil Conflict in Nepal.” Oxford Development Studies 33 (1): 47–62.

- Di John, J., and J. Putzel. 2009. Political Settlements: Issues Paper. GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- Elden, S. 2013. The Birth of Territory. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Fujikura, T. 2013. Discourses of Awareness. Kathmandu: Martin Chautari.

- Gallant, T. W. 1999. “Brigandage, Piracy, Capitalism, and State-Formation: Transnational Crime from a Historical World-Systems Perspective.” In States and Illegal Practices, edited by Josiah Heyman, 25–62. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- Gautam, Bhaskar, ed. 2008. Madhes Bidrohako Nàlãbelã. Kathmandu: Martin Chautari.

- Gautam, H. 2020. “Local Units in Dolpa Operate from District Headquarters.” Kathmandu Post, January 9. https://kathmandupost.com/karnali-province/2020/01/09/local-units-in-dolpa-operate-from-the-district-headquarters.

- Ghimire, B. 2020a. “Conflict Victims Decry Government’s Consultations as a Sham.” Kathmandu Post, January 14. https://kathmandupost.com/2/2020/01/14/conflict-victims-decry-government-s-consultations-as-a-sham.

- Ghimire, B. 2020b. “Conflict Victims Condemn Parties for Bulldozing Decision on Transitional Justice Appointments.” Kathmandu Post, January 18. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2020/01/18/conflict-victims-condemn-parties-for-bulldozing-decision-on-transitional-justice-appointments.

- Goodhand, J. 2008. “War, Peace and the Places in Between: Why Borderlands are Central.” In Whose Peace? Critical Perspectives on the Political Economy of Peacebuilding, edited by M. Pugh, N. Cooper, and M. Turner, 225–244. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goodhand, J. 2018. The Centrality of Margins: The Political Economy of Conflict and Development in Borderlands, Working Paper 2: ‘Borderlands, Brokers and Peacebuilding: War to Peace Transitions Viewed from the Margins’.

- Goodhand, J., O. Walton, and L. Pollock. 2018. Living on the Margins: The Role of Borderland Brokers in Post-War Transitions. http://borderlandsasia.org/living-on-the-margins.

- Guneratne, A., 2018. Many Tongues, One People: The Making of Tharu Identity in Nepal. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Gurung, P. 2014. “Police Brutality on Dolpo’s “Black Day” under Investigation.” The Record, June 14. http://www.recordnepal.com/wire/police-brutality-on-dolpos-black-day-under-investigation/.

- Hachhethu, K. 2018. “The Reluctant Federalist.” The Kathmandu Post, December 7. https://kathmandupost.com/author/krishna-hachhethu.

- Hoffmann, M. P. 2015. “In the Shadows of the Maoist Revolution: On the Role of the ‘People’s War’ in Facilitating the Occupation of Symbolic Space in Western Nepal.” Critique of Anthropology 35 (4): 389–406.

- Hutt, Michael. 2020. “Before the Dust Settled: Is Nepal’s 2015 Settlement a Seismic Constitution?” Conflict, Security & Development 20 (3): 379–400.

- ICG. 2007. Nepal’s Troubled Tarai Region (Asia Report No. 136). Brussels: International Crisis Group.

- Ishtiaque, A., M. Shrestha, and N. Chhetri. 2017. “Rapid Urban Growth in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: Monitoring Land Use Land Cover Dynamics of a Himalayan City with Landsat Imageries.” Environments 4 (4): 72.

- Jha, Dipendra. 2018. Federal Nepal: Trials and Tribulations. Kathmandu: Aakar Books.

- Jha, Awadhesh Kumar. 2019. “Nirmanma Aghi Badhdai Saptari.” Kantipur, January 11, https://ekantipur.com/pradesh-2/2019/01/11/154717850124154177.html.

- Joshi, M. 2010. “Between Clientalist Dependency and Liberal Market Economy: Rural Support for the Maoists Insurgency.” In The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal. Revolution in the Twenty First Century, edited by M. Lawoti and A. Pahari, 92–112. London: Routledge.

- Karki, D. 2019. “What’s Not in a Name? The Significance of Calling the Nepali Lowlands ‘Madhes’ or ‘Tarai’.” Paper Presented to the 17th Nepal Study Days of the Britain-Nepal Academic Council, April 15, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh.

- Karn, Sujeet. 2011. “Everyday Violence in Madhes: Identity Politics, Armed Groups and the Parallel Economy.” Studies in Nepali History and Society 16 (2): 297–319.

- Karn, S. 2018. “Continuity and Transformations in Nothern Borderlands: A Study of Contemporary Dolpo.” In Research Report, ‘Borderlands Brokers: War to Peace Transition in Nepal (District Maping Papers: Bardiya, Dolpa, Humla and Saptari)’, edited by Sujeet Karn, 33–60. Kathmandu: Martin Chautari. http://www.martinchautari.org.np/files/Borderlands-Brokers-War-to-Peace-Transition-in-Nepal.pdf.

- Karn, S., S. T. Limbu, and K. Jha. 2018. “2017 Local Elections in Madhes: Discussions from the Margins.” Studies in Nepali History and Society 23 (2): 277–307.

- Khan, M. 2010. Political Settlements and the Governance of Growth-Enhancing Institutions (Unpublished). http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/9968/.

- Khan, M. H. 2017. “Political Settlements and the Analysis of Institutions.” African Affairs 117 (469): 636–655.

- Lal, C. K. 2013. “Tarai-Madhesmà ântarik Upanive÷Vàdko Artha-Ràjnãti.” Madhes Adhyayan 2: 7–18.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Marsden, R. 2015. “Not Yet at Peace: Disappearances and the Politics of Loss in Nepal.” PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh.

- Meehan, P., and S. Plonski. 2017. Brokering the Margins: A Review of Concepts and Methods. Working Paper 1. Borderlands, Brokers and Peacebuilding Project. http://borderlandsasia.org/.

- Nayak, N. 2011. “The Madhesi Movement in Nepal: Implications for India.” Strategic Analysis 35 (4): 640–660.

- Nepal, P. 2020. “‘Anicchit garbha’ nai thiyo ta sanghiyata?” Ratopati, October 19. https://www.ratopati.com/story/151841/2020/10/19/debate-on-federalism-in-nepal-.

- Nugent, P. 2004. Smugglers, Secessionists and Loyal Citizens: The Lie of the Borderland Since 1914. London: James Currey.

- OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights). 2008. Conflict-Related Disappearances in Bardiya District. http://nepal.ohchr.org/en/resources/Documents/English/reports/HCR/2008_12_19_Bardiya_Report_Final_E.pdf.

- Oli, A. 2019. “Committee Formed to Merge Banke and Bardiya in Karnali Province.” myRepublica, December 29. https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/committee-formed-to-merge-banke-and-bardiya-in-karnali-province/.

- OpenNepal. 2013. Poverty Rates on District Level, 2001–2011. http://data.opennepal.net/content/poverty-rates-district-level-2001-2011.

- Pandey, Krishna. 2017. “Politicising Ethnicity: Tharu Contestation of Madheshi Identity in Nepal's Tarai.” The South Asianist 5 (1): 304–322.

- Pant, B., R. Rai, C. Wallrapp, R. Ghate, U. Shrestra, and A. Ram. 2017. “Horizontal Integration of Multiple Institutions: Solutions for Yarshagumba Related Conflict in the Himalayan Region of Nepal?” International Journal of The Commons. https://www.thecommonsjournal.org/articles/10.18352/ijc.717/.

- Parks, T., and W. Cole. 2010. Political Settlements: Implications for Development Policy and Practice. Asia Foundation, Occasional Paper No 2, US.

- Paswan, B., and P. Gill. 2018. “On Gender and Social Inclusion, Nepal's Politics Has a Long Way to Go.” The Wire, February 28. https://thewire.in/south-asia/nepal-politics-gender-social-inclusion.