ABSTRACT

This article is part of a Book Forum review of Sanjib Baruah’s book In the Name of the Nation: India and its Northeast. The Book Forum consists of individual commentaries on this text by five interested scholars, followed by a response by the author. The article may be read individually or alongside the other contributions to the Forum, which together constitute a comprehensive discussion of the themes and arguments in the book.

Sanjib Baruah’s writings on Northeast India have always been an exemplar for a kind of dialectical thinking that moves from entrenched historical-political realities to future possibilities – or as he phrases it in In the Name of the Nation (Citation2020), toward a political imagination ‘beyond state-centric thinking’ in which we can ‘engage with the vernacular intellectual life in the societies of Northeast India’ (180–181). But in his latest book’s concluding reflections this dialectic stalls, and Baruah’s position becomes decidedly pessimistic:

Northeast India urgently needs a politics of citizenship based not on memories of a real or imagined past but on a vision of a common future for the people who live in the region today. Unfortunately, we are unlikely to see an expansion of the political imagination in the near future. India’s prevailing governing philosophy is not conducive to fostering a climate of political innovation in the region. In the current scheme of things, it is hard to imagine the political space opening up for alternatives to the exclusionary politics of rightful shares to emerge in those parts of Northeast India where it has become the dominant form of claims-making’. (Baruah Citation2020, 192)

To rekindle Baruah’s dialectic, I would like to shift our attention from statist paternalism to ‘national kinship’ and its vernacular alternatives. By ‘national kinship,’ I mean the filial idioms through which political belonging and mutual dwellings/destinies are symbolized, and how they organize latent assumptions about how one can and should relate to others within the fait accompli of nationalized space.

It’s important to note that modern polities have never settled on an exact filial prototype (with its attendant sentiments and moral obligations) for national kinship. Mother India, for example, might evoke sentiments of maternal nurturing at an imaginary level of the body politic, but at a symbolic level hers is a paternal function that unites desire with the law – what Lacan called the ‘Name of the Father,’ which is also the commanding ‘No!’ of the Father. Mother India is unquestionably phallic as she necessarily merges with state apparatuses and ad hoc forms of sovereignty.

What about other idioms of national kinship? Unlike other modern polities, India has never had much success in rendering the demos in terms of siblingship-as-solidarity. Take the sorority of the ‘Seven Sisters,’ a catchphrase originating in the 1970s that was presumably meant to encourage coalition-building among the newly born federated states of the so-called Northeast. When its deixis shifted to the nation at large, the slogan seems to have unintentionally influenced the political unconscious of the mainland, emplacing the Northeastern states into what psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin calls the ‘daughter position’ of the Oedipal situation – that is, the feminized role of the Oedipal child in a patriarchal family who is charged with ‘accommodating and absorbing unmanageable tensions’ (Benjamin Citation2015, 275). If we replace ‘family’ with ‘nation,’ then we can easily translate Baruah’s argument from In the Name of the Nation into a psychoanalytic idiom: the so-called sisters of the Northeast have come to accommodate and absorb the nation’s sexual, economic, geopolitical, militaristic, and increasingly racialized anxieties and desires. And thus, within popular metaphors of national siblingship, we find ourselves returning to the name of the father/nation.

But what if there was an existing filial idiom that we could oppose to India’s rigid paternalism? Perhaps one that does not, in the name of the nation, simply opt for a horizontal integration of subnational identities under that authority? Instead, if we could find a lateral alternative to national kinship, a politically imaginative mode of siblingship-as-solidarity on the margins of the nation, then what political possibilities might it entail?

In Northeast India, one such mode exists which we might call ‘rites of total conversion.’ Trouble is, these are rarely conceived of as ‘political.’ In the vernacular, such rites are usually qualified as ‘pardons’ (uddhar in Assamese) and carry with them associations to marriage or, among the region’s Hindus, to the inclusive umbrella-like refuges of Vaishnava universalism. Phenomenologically, however, they entail a complete transformation of personhood (Ramirez Citation2014). In the modern era, these rites have become instances wherein individuals and families essentially convert from one ethnic group to another. Or, if Constitutional categories are preferred, from one caste or tribe to another. In other words, while these rites might be ‘traditional’ and even have precolonial origins, in the present imaginaire their continued salience is driven by a political pragmatism squarely within the confines of colonial-era demographics.

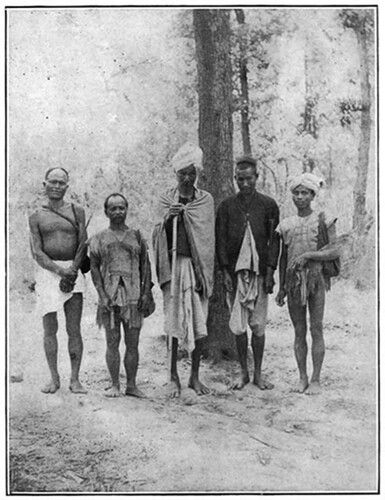

And yet, I have often heard these rites couched in terms of fulfilling a desire for ‘brotherhood’ – especially in response to fratricidal traumas. For example, in 2018 my friend Mr. Biren Bangthai, a Karbi activist from Mayong, was trying to explain to me what had gone wrong in the case of the ‘Panjuri Lynchings’Footnote1 and used these rites as an allegory. Biren Da claimed that the lynchings would not have happened if the lynchers had remembered, instituted, and educated their children about traditional mechanisms for incorporating strangers as brothers. During our conversation, Biren Da excused himself and went into his house. He soon emerged with a book: Edward Stack’s 1908 ethnography of The Mikirs (a colonial epithet for the Karbi people). Biren Da pointed to a bookmarked photograph (see ):

Look. These five men are … all Karbi. The author wrote here, this one is Assamese and this one Khasi … But the truth is they are all brothers. All Karbi brothers. They all completed the Bir-Kulut [conversion ritual]. Other castes-tribes have similar rituals.

Figure 1. ‘Group of Mikirs (North Cachar)’ From The Mikirs by Edward Stack (Indian Civil Service) and edited by Sir Charles James Lyall (Chief Commissioner of Assam).Footnote2

In his conclusion, Baruah makes use of a bon mot from French historian Pierre Vilar: ‘The history of the world can be best observed from the frontier’ (cited in Baruah Citation2020, 177). I would add that frontiers (however manufactured) are not one-dimensional. And maybe, the frontiers of those frontiers can tell a different story: not of the ‘history’ of the world, but of possible pasts and possible futures. Should we neglect these stories or write them off as too derivative or obviated to make a real difference, then we have more or less resigned ourselves to the waiting room of history. Baruah is far from being guilty of this; his work is cautious and careful, and no other scholar of Northeast India has done as much as he has to present a clear scholarly analysis of why a nuanced understanding of this complex region makes all the difference for moving beyond the mired anxieties of postcolonial politics. But not everything in this corner of India is done in the name of the nation; beyond the name of the father are bands of brothers and sisters who are tired of the same old governmental shit … and not all of their imaginative responses are equally governmental. If the history of the world can be best observed from the frontiers, then perhaps it can also be best critiqued from there with an eye to how we might transform the world into something better.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sean M. Dowdy

Sean M. Dowdy is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Oslo and an advanced candidate at the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute.

Notes

1 This bloody event occurred on 8 June 2018 near Dokmoka town in Karbi Anglong Autonomous District. Two interloping Assamese caste Hindus from Guwahati were murdered by a mob of Karbi and Kachari villagers who had misrecognized them as kidnappers following a rash of rumors about sightings of preternatural ‘child thieves’ (xupadhora in Assamese, phankodong in Karbi). In the weeks following the murders, the entire state of Assam fell into a collective panic. What began as a very local and contextual (if tragic) misunderstanding transformed into bona fide ethnopolitical conflict between tokens of more general sociopolitical types: Assamese vs. Karbi, Castes vs. Tribes, Valley vs. Hills, etc.

2 Stack and Lyall (Citation1908, 23) elaborate on this photograph: ‘During the Burmese wars in the early part of the last century, the [Mikir/Karbi] tribe deserted its settlements in the submontane tract, and fled into the higher hills. Many Assamese are reported to have taken refuge with them during this time, and to have become Mikirs…in North Cachar outsiders are admitted into the tribe and are enrolled as members of one of the kurs [clans], after purification by one of the Bē-kuru kur…. In the group [above]…the short man is evidently a Khasi, while the man to his left appears to be an Assamese.' What are referred to as Bē-Kuru clans here is, in contemporary Karbi lexicography, written as Bîr-Kūlut. The term is actually a totemic one (a fact that is absent from Stack's ethnography). It refers to a particular species of tree that is the totem for the Kro sub-clan of the Terang sib. If a person is to ritually ‘become Karbi,’ then they must pass under a bent branch of this tree over a stream of water for a specified number of times.

References

- Baruah, Sanjib. 2020. In the Name of the Nation: India and its Northeast. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Benjamin, Jessica. 2015. “Masculinity, Complex: A Historical Take.” Studies in Gender and Sexuality 16: 271–277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2015.1107451.

- Ramirez, Philippe. 2014. People of the Margins: Across Ethnic Boundaries in North-East India. Guwahati: Spectrum.

- Stack, Edward, and Charles James Lyall. 1908. The Mikirs: From the Papers of the Late Edward Stack. London: D. Nutt.