ABSTRACT

Ragging in Sri Lanka is a longstanding initiation ritual, similar to hazing and bullying. The severe harassment of new students by seniors has led to adverse consequences including depression, university dropouts and suicide. Although, a significant problem, research on ragging is scarce. This research aimed to explore how staff and work-affiliated individuals at Jaffna University resonate around the phenomenon of ragging. Seven focus group discussions and eleven semi-structured interviews were conducted. Foucauldian Discourse Analysis and Bandura’s Moral Disengagement theory were used to interpret the data. Three main discourses reflected the context: ragging as normal and necessary, insecurity and fear of reprisal, and voices of resistance. Participants often felt unsupported and therefore adapted their moral compasses to survive in this insecure environment. These findings demonstrate a fragmented approach to ragging that not only diminished any efforts towards elimination but affected how staff were forced to adjust their behavior to work in this environment. To address ragging, there is a need to adhere to a consistent strategy focusing on increasing awareness and supporting staff by holding accountable those at all levels of the administrative hierarchy in promoting a safe working environment for all.

Introduction

Ragging is an initiation practice carried out by senior students on new entrants in universities in South Asian countries such as Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, and Nepal (Nallapu Citation2013; Premadasa et al. Citation2011; Shakya and Maskey Citation2012; Wajahat Citation2014; Wickramasinghe et al. Citation2022). This practice was initially performed to create friendships, comradery and a rite of passage into university life, but has now transitioned into a more harmful practice where junior students are subjected to psychological/emotional, physical, and/or sexual violence resulting in severe health consequences (Ahmer et al. Citation2008; Gunatilaka Citation2019; Pai and Chandra Citation2009; Shakya and Maskey Citation2012; Wickramasinghe et al. Citation2022). The practice of ragging is analogous to ‘hazing’ in the USA, ‘Bizutage’ in France, ‘Praxe’ in Portugal, and is similar to practices apparent in educational institutions and universities globally. It varies by country context in both form and severity (Garg Citation2009; Huysamer and Seroto Citation2021; Wickramasinghe et al. Citation2022). Most research is from USA (Allan and Madden Citation2012; Campo, Poulos, and Sipple Citation2005; Hoover and Pollard Citation2000) and indicates hazing to be a widespread practice in high schools and universities. Despite many of these initiation rituals being harmful, and causing detrimental effects, they remain understudied (Fávero et al. Citation2015).

In Sri Lanka, ragging is defined by the University Grants Commission (UGC), the main governing body for universities, as ‘any deliberate act by an individual student or group of students, which causes physical or psychological stress or trauma and results in humiliating, harassing and intimidating the other person’ (UGC Citation2017). Ragging has long been considered part of the university subculture. Initiation for new students ranges from performing trivial tasks like singing, adhering to a demeaning dress code, to performing extreme physical activities and sexual harassment (Gunatilaka Citation2019).

In South Asia, ragging has been found to cause adverse health effects, including permanent psychological and behavioral changes in student victims (Garg Citation2009; Gunatilaka Citation2019; Nallapu Citation2013; Premadasa et al. Citation2011; Shakya et al. Citation2011). Ragging cases reported in Sri Lanka include students who have been severely injured, paralyzed or died. (Gunatilaka Citation2019). The Sri Lankan Ministry of Education reports, approximately 2000 university students dropout annually while a few have committed suicide due to ragging (Senanayake Citation2020; Warunasuriya Citation2016). Despite the often harsh nature of this practice, many students still consider it a bonding experience and an orientation into university life (Gunatilaka Citation2019). Similarly, studies conducted globally indicate that many pro-initiation students consider it a small price to pay to have a sense of belonging to a group, be in favor with senior students, and to receive a university education (Dias and Sá Citation2014; Gunatilaka Citation2019; Véliz-Calderón and Allan Citation2017).

To better comprehend the complexity of ragging in Sri Lanka, it is important to understand the context. Sri Lanka is a country with a population of 21 million and a literacy rate of 92% along with higher human development indicators than most countries in the region, such as low maternal and neonatal mortality ratios, low adolescent birth rates (UNDP Citation2020). The country is multicultural, multilingual, and multiethnic, consisting of an ethno-religious blend of Sinhalese (75%), Tamils (11%), Moors (Muslims) (9%), and other groups (5%). The ethnic-religious groups are regionally segregated with the Northern and Eastern Provinces predominated by the Tamil Hindus; the rest of the country is mainly Sinhalese Buddhists while the Muslim population is spread throughout. The main languages are Sinhala and Tamil, and English estimated to be spoken by 10–15% of the population.

Sri Lankan society has been typically stratified by four major elements; caste, class, gender, and ethnicity (Silva Citation1999). The caste system is considered to be more of a secular status upheld by land ownership, religious organizations, and rituals which are firmly rooted in beliefs of innate superiority and inferiority (Silva, Sivapragasam, and Thanges Citation2009). The establishment of a universal welfare system between 1938 and 1950, with free education and health care aimed to eliminate social stratifications and unite all groups (Silva, Sivapragasam, and Thanges Citation2009). This has led to caste becoming a hidden entity, moving from a caste stratified to a class-stratified society. The modern-day class structure evolved due to many socio-economic and political changes, causing a larger disparity between the urban upper class and the rural lower classes which transcends ethnic divisions (Ekanayake and Guruge Citation2016).

The last of the aforementioned dimensions, the normalization of violence is gendered and has been attributed to the patriarchal society that promotes male dominance where Sri Lankan women are often treated like subordinates (Ruwanpura Citation2011). A woman perceived as not conforming to the heteronormative roles of being an obedient daughter, chaste wife, and nurturing mother is frowned upon by society (Alwis Citation2002). This is further enforced by the Sri Lankan concept of ‘Læjja-baya’ (shame and fear of ridicule), where young women are expected to behave with modesty, respectability, and be chaste, if not, they are exposed to ridicule and shame (Ruwanpura Citation2011). Sri Lankan men are expected to exhibit stereotypical ‘masculinity’ conforming to certain hegemonic roles to be considered ‘manly’. They are expected to be strong both physically and mentally, protect, provide and make decisions for their families. Men who don’t comply, often feel emasculated and ridiculed by society (Ruwanpura Citation2011).

Sri Lanka is recovering from the devastation incurred by the 27-year civil war between the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam) and the Sri Lankan government which ended in 2009 (Ganguly Citation2018). Violence has been a part of the past but also remains in daily life as a method of fostering discipline, evident in corporal punishment that continues to occur at home, despite it being prohibited in schools since 2005 (Lakshman Citation2018). Society’s acceptance of male dominance has paved the way for women being victimized, both psychologically and physically (Mel, Peiris, and Gomez Citation2013). Several studies on intimate partner violence in Sri Lanka have shown violence rates to be between 17% and 72% (Jayasuriya, Wijewardena, and Axemo Citation2011; Sri Lanka and Department of Census and Statistics Citation2017). These studies also demonstrate societal perceptions and permissive attitudes toward violence (Gunatilaka Citation2019).

Traditionally, education in Sri Lanka was limited to the high-caste people or the ‘elite’ (Ekanayake and Guruge Citation2016). Following the introduction of the free education policy, there was an increase in the number of university seats, a change of medium of instruction from English to Sinhalese and Tamil, and a change in the admission policy of universities from an elitist to a mass model (Kamala Liyanage Citation2014). The most prominent feature of this change was seen in the socioeconomic structure of the student composition, due to the higher intake from rural areas (Samaranayake Citation2013). The previous majority of English-speaking urban upper- and upper-middle classes, were replaced by Sinhalese and Tamil-speaking lower classes from lesser privileged backgrounds (Samaranayake Citation2013).

Currently, gaining entrance to one of the 15 state universities is an honor bestowed upon a fraction of the eligible students. In 2018 out of the 167,992 students that qualified for university entrance only 31,881 (19%) were enrolled in a university (Sri Lanka University Statistics Citation2019) due to the limited number of seats (Navaz Citation2012). The expansion of government-funded universities and the influx of students did not go hand in hand with the expansion of infrastructure, accommodation, and leisure activities for students (Samaranayake Citation2013). The lack of funding has led to numerous flaws in the university system such as a lack of lecturers, decreased quality of teaching, lack of proper buildings and equipment, lack of student housing, and poor security within the university (Weeramunda Citation2008). These changes and shortcomings have triggered unrest among the students and are believed to contribute to the practice of ragging (Matthews Citation1995; Samaranayake Citation2013).

Ragging is considered a criminal offense that carries a severe punishment (Sri Lankan Government Citation1998). Yet it is still rampant in Sri Lankan universities. Efforts have been made by the government and the UGC to put an end to this practice. The UGC has formed ‘Centers for Gender Equity and Equality’ in all the Universities to facilitate the reporting process, along with hotlines and mobile applications, where students can report incidents of ragging (UGC Citation2020). Recently there has also been an increase in knowledge and awareness of the harmfulness of ragging and a movement to end this practice in Sri Lanka, through organizations such as UNFPA, UNICEF, local media, and other social media forums.

Ragging is a complex phenomenon where not only students are affected but also staff. It remains a persistent and daunting public health challenge. This research aimed to explore how staff and work-affiliated individuals at Jaffna University resonate around the phenomenon of ragging.

Methods

A qualitative design using participant observation was chosen to explore this topic. Eleven semi-structured interviews and seven focus group discussion (FGD) were carried out from February to March and from September to November 2019.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review committee of the University of Jaffna (J/ERC/18/96/NDR/0200). Participants were informed of their right to decline participation at any time and confidentiality was assured. Verbal consents were obtained before the interviews and focus groups.

Established in 1974, the University of Jaffna has 10 faculties including Agriculture, Applied Science, Arts, Business Studies, Engineering, Graduate Studies, Management Studies & Commerce, Medicine, Science and most recently (2016) the Faculty of Technology (University of Jaffna Citation2020). The university has a main campus and two off-site campuses with a student population of about 7000 (University of Jaffna Citation2020). First and final-year students are housed in campus residences, but most students have off-campus housing. The University of Jaffna has similar numbers of students of different ethnicities and was therefore chosen for its diverse student composition, unlike other Sri Lankan universities where the majority are Sinhalese.

The principal investigator (PI) initially sent out a letter to the department heads, introducing the study and the aim. Thereafter, they were asked for assistance in recruiting lecturers and student counsellors willing to participate in the FDGs. The FGDs were conducted with junior and senior lecturers and student counsellors from various faculties in the university (). Junior lectures were defined as newly graduated, with less than five years of teaching experience as compared to senior lectures who held longer tenures and possessed a master’s degree or above (Navaz Citation2012). The student counselors were appointed to look after the welfare of students and were responsible for investigating ragging incidents. They were senior lecturers from different faculties, appointed by the vice chancellor for a one year period and did not require any special qualifications or training.

Table 1. Focus group discussion participants.

Due to group dynamics, logistical and practicality reasons, semi-structured interviews were conducted with other work-affiliated individuals at the university who were willing to share their experiences. These were: marshals providing university security, wardens in charge of student housing, and various university-affiliated and medical personnel in the Jaffna hospital. One of the participants encouraged the research team to interview a self-proclaimed former victim/ragger, who was then included in the study ().

Table 2. Description of participants of semi-structured interviews.

The FGDs and interviews, lasting from 45 to 60 min were conducted in English and Tamil. FDGs and interviews followed a pre-arranged question format. Quiet and private locations were used. FGDs consisted of five to eight participants per group. Notes were taken by two observers in the Tamil focus groups and by one observer in the English groups. FGDs were audio recorded and interviews documented in written form. The extensive notes including verbatim quotes, contained details from the interviews thereby facilitating the use of illustrative extracts from the transcripts. The participating researchers discussed the interviews and FGDs immediately after being conducted and before subsequent interviews to refine probing questions and incorporate emerging information. The qualitative data was transcribed, translated and back-translated into English by the PI and a Tamil-speaking research assistant.

The FDGs and interviews were conducted by members of the diverse research team; PI/first author, a senior researcher, and a Tamil-speaking research assistant. The PI/first author, a Sri Lankan-born medical doctor, grew up in the context yet received her higher education overseas. Having not attended Sri Lankan university, she had an insider/outsider vantage point. She spent several months in Jaffna getting acquainted with the university setup and surroundings, observing interactions of students, lecturers, administrators, and various groups of people connected to the university directly and indirectly. The other researchers were as follows; a Swedish medical doctor with 20 years of experience working in Sri Lanka with an outsider/insider perspective; and a research assistant who was a young Tamil nursing assistant providing insight into the Tamil context.

At the analysis stage, the research team included a senior researcher outside the Sri Lankan context, enhancing questioning the ‘taken for granted’ ideas commonly held by cultural insiders. Being naïve of the context can be a strength and thereby expands the data interpretations.

Theoretical lenses

Foucauldian discourse analysis was employed for its ability to reveal how the participants construct ragging and how they regulate their conduct within the university context through their utterances (Arribas-Ayllon and Walkerdine Citation2017). In other words, how these individuals involved in university life construct, resonate, and position themselves about their responsibilities around ragging. Discourses are culturally constructed norms in the form of statements or how a given group talk about things they have in common which they believe to be the truth. Foucault holds that there is no one absolute truth but perspectives observed as truths. When certain discourses or truths are accepted they become a form of knowledge, giving that group the power to define the problem. Similarly, those persons in power contribute to the production of knowledge, in what can and cannot be discussed. This yields the production and reproduction cycle of power (Foucault Citation1969) and knowledge within a given group or society (Wetherell, Taylor, and Yates Citation2001).

According to Foucault, discourse analysis reveals the interactions of the knowledge and power that governs human conduct surrounding certain practices and the techniques of self-management and behavior modification that the individual lends itself to. Foucault claims that individuals, in their quest to self-manage their conduct, attempt to adhere to a moral code. However, these moral positions are not fixed within the individual but flex to allow them to manage themselves in a place where the power is skewed (Arribas-Ayllon and Walkerdine Citation2017). How individuals problematize and change or modify their behavior in relation to certain practices and its effects is continuously adjusted to, as a survival mechanism. This Foucauldian stance on how individuals’ navigate the production and reproduction of power and knowledge marries well to Bandura’s (Citation2002) theory on Moral disengagement. Whereas Foucault draws attention to the production of knowledge and power, Bandura’s theory provides a step deeper into how the participants adapt and manage themselves within a system that allows ragging to prevail. According to Bandura, people usually refrain from doing wrong or behaving immorally by following their own moral compass or self-regulatory mechanisms. These self-regulatory mechanisms of so-called autonomous moral conduct are not fixed but influenced by the social context they are subjected to. Therefore, behavior that would normally be conceived as reprehensible or harmful becomes more acceptable and benign in a given social setting, allowing a person to selectively disengage from their moral compass (Bandura Citation2002; Haney Citation2016).

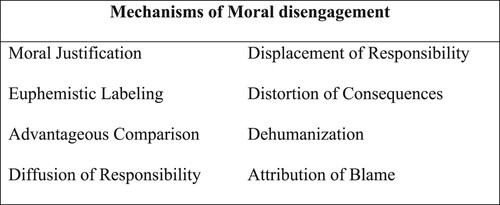

Moral disengagement theory holds that individuals disengage using the following mechanisms; moral justification, euphemistic labeling, advantageous comparison, diffusion of responsibility, displacement of responsibility, distortion of consequences, dehumanization and attribution of blame (Bandura Citation2002; ). These mechanisms elucidate how and why participants might turn a blind eye, condone ragging, or behave as they do. Bandura’s mechanisms become a coping strategy to exist in this particular environment where the university system has difficulties in addressing the problem of ragging.

Findings/discussion

The Foucauldian discourse analysis revealed three main discourses: Ragging as normal and necessary, Insecurity and fear of reprisal, and Voices of resistance. Thereafter, the emergence of participants’ adaptive behaviors from their utterances is examined through the lens of Bandura's moral disengagement theory.

Ragging as normal and necessary

Ragging as normal and necessary was a prominent discourse that emerged during the discussions and interviews. Ragging is often referred to as a ‘rite of passage’ or a university ‘subculture’ both by students and society, reinforcing its normalization. Although some participants claimed it was a form of interaction that helped create deeper bonds between the seniors and juniors, others indicated that ragging has evolved into a harmful practice:

It has definitely worsened. When I was young it was just fun but now it has become a completely different thing. (S2, F)

Some suggest ragging starts even before entering the universities:

Ragging starts (earlier) in schools now, like putting sand inside the shirts, hitting, putting chili powder in the underwear … . (B1, I)

This is in line with the studies found globally (Allan and Madden Citation2012; Dias and Sá Citation2014; Garg Citation2009) where such initiation rituals have changed from their historically milder forms to more violent forms seen within universities. Furthermore, these forms of violent ragging share certain similarities with gang initiation rituals, whereby submitting to violence or enforcing it, which is used as a means of gaining social acceptance within a chosen group of peers and solidifying their standing within this group (Murer and Schwarze Citation2020). On the contrary, Mann et al. (Citation2016) claims that severe initiation practices can lead to less group affiliation depending on the degree of humiliation experienced by the victim. Thus, making the students’ belief that ragging forms deeper bonds between the seniors and juniors, to be questionable (Prevalence of Ragging and Sexual and Gender Based Violence Citation2022).

Universities are microcosms of society that mirror Sri Lanka’s rigid societal roles and norms, related to age, gender, and socioeconomic class (Matthews Citation1995; Ruwanpura Citation2011). Therefore, ragging has been used as a way to ensure these roles and norms are upheld within the university (Wickramasinghe et al. Citation2022). According to some researchers (Due et al. Citation2009; Garg Citation2009), large disparities within a society can lead to a higher prevalence of ragging and similar practices, which may be understood as a method of equalization (Gunatilaka Citation2019). The participants saw ragging as the method of leveling the students:

They (students) are normalizing or making uniformity among the students (through ragging) (S1, F)

Another interviewee cited society as inherently accepting of violence:

We are a masochist society, we like to inflict pain and don’t feel empathy. (C3, I)

The infliction of pain and lack of empathy are reflected in severe ragging, yet those who support this practice, consider it ‘normal’. The post-war situation was considered to possibly have led to more unresolved aggression, manifested through ragging; ‘there is post-war PTSD in families, so they become more violent’. This unresolved sense of loss was said to play into their aggressive acts; ‘many students lost parents or family members during the war, so they have an inner aggression’. This holds true in many post-war societies (Mendeloff Citation2009).

Jaffna University is a melting pot where students from different ethnicities, class, caste, and gender sometimes mix for the first time. Gamage (Citation2017) argues that male students use ragging as a pretext to find a suitable female partner for marriage. The university environment provides an ideal opportunity for males to demonstrate their power and masculinity to approach females they often did not get a chance to interact with. This competition for mates is magnified as most Sri Lankan universities have twice as many female students as compared to males, which is also true of Jaffna university (Sri Lanka University Statistics Citation2019).

Although there are mixed schools in Sri Lanka, most schools are segregated by gender and language, which leads to isolated groups. This sets the stage for what ragging was originally intended for, a way to unite students (Gunatilaka Citation2019; Ruwanpura Citation2011). Therefore, practices such as ragging and hazing are considered to serve a higher purpose, to form group cohesiveness and comradery (Allan and Madden Citation2012; Campo, Poulos, and Sipple Citation2005; Massey and Massey Citation2017).

Apart from being empowered by ragging, some of the staff consider ragging to be beneficial in molding students and making them more disciplined.

According to me ragging should be there … I will say that ragging is the thing that helped improve my personality. (J1, F)

Another commented upon the discipline:

There is no discipline in university now. They don’t know how to behave in lecture hall. In our time if we sat on a chair and put our legs over chairs, seniors will notice that and after lectures, they will hit us. Now it is not there. (J1, I)

Although some considered ragging to be a harmful practice, there were still others who saw it necessary and a part and parcel of University life’.

Insecurity and fear of reprisal

In this particular discourse, the staff believed that there was an inverse power structure within the university, where the students held more power. According to Weeramunda (Citation2008) and Matthews (Citation1995), this has been brought upon by the fragmentation and polarization that has occurred within the university system. A perceived lack of a united front among the staff and administration is demonstrated by

There is violence among the staff members also. They fight among themselves so the students don’t listen to them. The senior staff suppress the junior staff. (B1, I)

Another participant expressed how malleable the chain of command could be:

The students bypass the Marshals and get leniency from the Deans and Vice chancellor. (S1, F)

According to Lekamwasam et al. (Citation2015), although university administrators are supposed to follow a ‘zero tolerance’ policy when it comes to ragging, unfortunately, this is not the case. This is a fact that the students are aware of, knowing that the perpetrator will probably not face any consequences if they are caught has led them to believe that they wield more power than the staff:

Even with all the evidence, if the students get punished, they know that they can get out of that punishment very soon. Maybe they will miss classes for one month and then after some pressure from the parents and their excuses, they are allowed back. (S1, F)

These situations give the students an upper hand underscoring their position of power within the university and thereby giving rise to the ‘power of the gang’ versus authorities:

Students have the upper hand. They think they have the power to control universities. So, the 1st year students think seniors have more power and obey them, because they fight with the university administration. (B1, I)

The lecturers revealed that the students had a lack of trust and respect towards them. This was exemplified by the following statement:

There is no trust between students and the lectures. There’s a big gap. (B2, I)

One interviewee felt that the students lacked confidence in the competency of certain lecturers:

The lecturers of this faculty have been given a curriculum put together by all the experts in these fields but the newly graduated lecturers are not competent enough to teach advanced material. The students think that the lecturers are not competent to teach the subjects. (B1, I)

The lack of confidence in the lecturers stems from outdated pedagogical systems (Edirisinghe Citation2018). The top-down authoritarian style instruction, where there is often no room for discussion between the teachers and the students further contributes to the dissatisfaction. According to Edirisinghe (Citation2018), the method of enrolling lecturers amongst the graduated students of the same university further limits the chances of exchanging new ideas and knowledge. At times the young lecturers were ill-equipped to teach certain subjects let alone know how to handle classroom conflicts.

The disappointment and frustration amongst the students towards the teaching methods and the staff may be the cause of aggression and subsequent lack of belief in the lecturers. There were instances where students used threats and humiliated the lecturers, which in turn made the lecturers avoid getting involved in any ragging incidents; A senior lecturer had this to say:

They (lecturers) are also very keen on controlling ragging but they are threatened and sometimes are scared to get involved directly in these (ragging) matters. So, they pretend they didn’t notice anything. (S2, F)

When the interviewees were asked if the lecturers could not try to discipline the students, they replied:

They will cause problems for us. Whoever gets involved with the students (tries to discipline), gets into trouble. (J2, F)

The student's lack of respect towards the staff was described as

Students use bad words towards the lecturers also. Even the security guards don’t want to intervene because the students verbally abuse them also. (B2, I)

A reason some of the measures taken to prevent ragging may have failed due to the isolated attempts to stop ragging, instead of a single integrated action plan (Lekamwasam et al. Citation2015). The lack of a united front within the university system, between the staff and the administration, has in other words led to the re-creation of a new order where the students rule and the staff are left vulnerable. According to the UGC (Citation2020), the university administration and the academic staff should be unanimous in their stand against ragging and should be able to instill faith in the students by developing better student-teacher relationships.

Voices of resistance

This discourse was more promising in curbing the violence of ragging than the other discourses which showed blind acceptance, lack of hope and powerlessness. Although it was often apathetically stated; ‘people have given up on long term plans’, the voices of resistance discourse demonstrated how some individuals challenged the norm and worked towards eradicating the violence of the practice whilst promoting the benefits. These individuals had recommendations on how to curb ragging and spoke up about the shortcomings in the educational system, as observed in the following comments:

The university should develop policies to prepare the students for the international job market. They must develop policies, systems, and clearly define roles for everyone (university staff). That’s good for the students and challenges them. I can’t say that it’s just ragging, because the problem is us. If we direct them towards the correct path then there is no more ragging. Just see the universities in other countries, there is no ragging because the students know their options for the future. We don’t have such a system so we have to struggle. (S1, F)

Participants stated that there was a small group of students that stood up to the raggers. They refused to become victims of ragging or participate in the ragging of others and are were referred to as anti-raggers. Studies show these students were often isolated from the rest of the batch and excluded from all student activities (Gunatilaka Citation2019; Ruwanpura Citation2011). According to Mann et al. (Citation2016), it’s always a small group of people that brings about change indicating how this resistance could be a supportive catalyst for change. Similarly, some lecturers believed students who have the courage to become isolated and stand up for what is wrong should be recognized for their effort and anti-ragger stances should be encouraged:

Anti-raggers should be made more powerful. We should give them help from the staff and we should build the anti-raggers up. Then by the 2nd year there will be a bigger group of anti-raggers. So, we should help them in a subtle way so that they become more powerful. (S3, F)

The junior lecturers that recently graduated also had solutions to turn ragging into a more positive experience and had ideas how they could support each other by creating peer groups within themselves. This is a method proven to be of value according to several studies (Cowie and Hutson Citation2005; Mann et al. Citation2017). A junior lecturer had this to say from his time as a student:

We asked for a student support system like that in foreign countries. In our batch if there is ragging or something that causes stress, depression or something is going on, he or she can talk to colleagues first. (J3, F)

Even though measures such as a law prohibiting ragging, digital apps to report ragging incidents among others, have been put in place to combat ragging, these have not been successful, yet certain university staff put themselves at risk by directly addressing ragging. An interviewee responsible for security issues expressed his frustration and suppressed emotions at attempting to carry out his job:

Students think we are their enemies. They sometimes damage our motorbikes. It’s a very stressful job we are doing and we need to meditate afterwards, not to lose our temper at home and scold our wives. (A1, I)

Students lacked trust in the university system owing to incidents of ragging which were not properly investigated nor appropriate action taken, yet there was still hope that there were some individuals could make a difference. Some studies conducted in the USA, indicated that the involvement of staff helped reduce such practices (Allan and Madden Citation2012; Hakkola, Allan, and Kerschner Citation2019). One such intervention was carried out by Hakkola, Allan, and Kerschner (Citation2019), where they designed a program to increase knowledge and understanding of hazing, ethical leadership and bystander intervention strategies aimed at the staff and students. Therefore, students and lecturers who attempt to eliminate ragging could be further motivated with similar programs and interventions. Such individuals would also be empowered if they felt supported by the University administration, standing steadfast in punishing perpetrators of ragging and not fold due to the pressure of student retaliations. There is strength in numbers.

The aforementioned discourses; ragging as normal and necessary, insecurity and fear of reprisal, and voices of resistance, seen through the Foucauldian lens reveals skewed power dynamics and lack of training and support within this troubled context. These discourses lay a foundation for moving to a deeper understanding of just how these participants creatively adapt to this context by morally disengaging, as understood through the lens of Bandura’s moral disengagement (Bandura Citation2002). Foucault allowed us to see the macro discourses but as we were interested in actionable interventions, Banduras moral disengagement theory permitted us to go deeper to see on a more personal level how individuals comport themselves to function within this flawed or fragmented system. This gave more valuable information concerning the dynamics on the front line. This paper is about the very staff that one would expect to be able to address the problem, therefore, their individual responses to the environment became most important. This is also part of emergent design.

Moral disengagement

We departed from Foucault’s claims of how statements and subjects are formed within certain societies or groups depending on the power structure within that given system. The power structure within the university system can be seen as fragmented, leading to a loss of the usual top-down power structure where the lecturers and administration normally hold power. The hierarchical structure therefore becomes skewed, leaving a power vacuum whereby the raggers take hold. Selective moral disengagement (Bandura Citation2002) is then employed as a coping strategy for those individuals working at the university. To survive working in this fragmented structure as students fill the power void and the authorities are forced to adapt. According to Bandura (Citation2002), people respond in different ways according to personal interactions and contextual influences by selective activation and disengagement of moral standards. Zimbardo (Citation2011), in his book on The Lucifer Effect highlights how it is in human nature that situational factors can make good people engage in or turn a blind eye to malevolent acts to fulfill their basic human needs of safety and security. He further states that this is in part due to a system failure and in this case a lack of a cohesive institutional approach.

The university staff and administration were often bystanders in incidents of ragging and refrained from intervening due to different reasons. One such reason could be the assumption that they choose not to be the moral agents responsible for curbing ragging. Similar sentiment was shared by bystanders in several studies on bullying (Killer et al. Citation2019; Obermann Citation2011; Thornberg, Pozzoli, and Gini Citation2021) and other forms of group violence (Staub Citation2000) where morally disengaging is encouraged through fear of repercussions.

Bandura’s (Citation2002) eight mechanisms () by which an individual can morally disengage allow people to engage in ‘self-serving’ behavior that deviates from their moral principles without evoking emotions such as remorse and guilt (Obermann Citation2011).

Moral Justification, one of the above-mentioned mechanisms, allows an individual to rationalize harmful behavior by rendering it to serve a higher moral and social purpose. Participants in our study justified ragging by saying things such as; ‘Ragging has gone on for generations’, which they believed absolved them from any wrong doing. While others made statements invoking a tradition:

Some staff members justify ragging by saying ‘we were students and we did these things, so why should we penalize these guys (students)?’ (S2, F)

While others justified the continuation of ragging as essential for the discipline of students:

If we (lecturers) stop the ragging, lecturers will suffer the most because students don’t know discipline. (J1, F)

The necessity of violence for discipline was expressed through this metaphor:

If stone isn’t hit by a chisel, it can’t become statue. (J1, F)

Studies on hazing (Allan and Madden Citation2018; McCreary, Bray, and Thomas Citation2016) conducted among students in the USA had similar findings, where it was suggested that students themselves used moral justification to clear themselves from any wrongdoing. A Canadian study (Massey and Massey Citation2017) found that students justified hazing by describing it as necessary for ‘team bonding’. The practice of hazing by the Brazilian military police recruits was justified as developing the seniors leadership skills (Albuquerque and Paes-Machado Citation2004). Similarly, our participants also reverted to moral justification.

According to Bandura (Citation2002), harmful actions are given a different appearance by referring to them by less harsher terms through the mechanism of Euphemistic Labeling. Research carried out on hazing (E. J. Allan and Madden Citation2012; Hoover and Pollard Citation2000; Silveira and Hudson Citation2015; Wickramasinghe, Axemo, et al. Citation2022) has demonstrated that students often did not acknowledge hazing to be a harmful practice but a bonding experience. This was a sentiment shared by the study individuals as reflected in the following comment:

It’s just bonding and it’s only for a few months. (J3, F)

Advantageous Comparison is another mechanism whereby despicable acts are made to appear righteous by contrasting them with worse actions and conduct and helps individuals morally disengage. Participants also used this to portray that the ragging is much worse at other universities compared to Jaffna University thereby downplaying the severity of ragging there:

Here it is not bad like Colombo. Here they rag only about 2 years. It’s not bad ragging here. (S3, F)

While others downplayed incidents suggesting they were not sexually invasive:

Nothing sexual during ragging. Only asked to undress and salute. (D1, I)

According to McCreary, Bray, and Thomas (Citation2016) when practices like hazing occurs across larger communities and over a long duration, it is easier to draw advantageous comparisons between groups and time frames. This is especially seen among individuals attached to the Jaffna university, where they often compared different faculties, universities, and periods in time to highlight the so-called ‘gentler’ form of ragging that occurs, much like the students of the university (Wickramasinghe et al. Citation2022).

Participants in our study saw Diffusion of Responsibility as a means to justify their attitudes and behavior towards ragging, by minimizing their role and avoiding personal responsibility. This diffusing of responsibility was used to defer blame by saying they are just a small part of the whole system and avoided blaming a particular person, as in this quote ‘the education system is to blame for this’. The following metaphor also captures diffusing responsibility:

I don’t know how we can stop that (ragging). Now it’s like a cancer! It’s developing and new cells keep joining. (S3, F)

Displacement of responsibility, a similar mechanism that also lays blame was noted to ascribe the failure to respond to particular individuals or superiors. The study participants believed it was not their responsibility, but the responsibility of the university administration to put a stop to ragging. Zimbardo (Citation2011) in his experiments of human nature also found that the presence of a large group of individuals leads to the displacement responsibility and the ‘bystander’ effect’, where most believed that it was not their responsibility to stop harmful behavior but someone else’s. Some participants expressed that taking action against ragging was the university administration’s responsibility:

… See the powerful positions they are in? They are Deans and some of the others. If they can’t stop it who else can? (S2, F)

Alternatively, participants also used Distortion of Consequences a way to overcome their moral sanctions by disregarding, distorting, or minimizing the harmfulness of ragging. Similarly, many students were found to distort the harmful consequences of hazing and ragging to be viewed as beneficial in studies carried out by Allan and Madden (Citation2018) and Wickramasinghe et al. (Citation2022). This makes it easier to ignore one’s moral obligations when it is assumed that is serves a higher purpose, like enriching an individual’s life:

They hit me again and again, and I got courage. It improved my personality and brought me to this place. (J1, F)

Despite ragging dehumanizing it’s victim (Wickramasinghe, Axemo, et al. Citation2022), dehumanizing, was not a particularly salient feature of the participants’ discourses. This could be significant by its absence as violence has been normalized. The following quote did reduce students to non-agential material:

They (students) are like clay. They listen to anything. (B3, I)

The study participants frequently used attribution of blame as a means to defer culpability away from themselves and towards the victims or circumstances. Kowalski et al. (Citation2021) states that a method of attributing blame, is to say that the guilt lays with the victims themselves, because they choose to undergo hazing to seek membership in groups or teams. Kowalski et al. (Citation2021) also claimed hazing rituals are dictated by tradition and circumstances and are beyond personal control. Similarly some participants evaded responsibility by attributing blame towards students and other circumstances. This was evident in statements like:

They (the students) say ‘we have to create our batch-fit (group belonging)’, so in the name of ‘Batch-fit’ the juniors will do whatever the seniors want. It doesn’t matter what we (the admin) say. (J2, F)

The following statement by a member of the staff captures how the blame was shifted elsewhere:

The education system and the attitude of lecturers are to be blamed. Some lecturers are not good role models to the students. (S1, F)

Bandura’s (Citation2002) mechanisms of selective moral disengagement together with Foucauldian discourse analysis render a deeper insight into how individuals working with Jaffna University, try to conduct, resonate and place themselves in relation to their responsibilities regarding ragging and self-manage and work in an unsupportive and fragmented environment where the power balance is skewed.

Strengths and limitations

The fact that ragging had gone on for centuries and is considered a university ‘subculture’ has been a controversial topic rarely discussed, until recently. Most people in Sri Lankan society are noted to be cautious about sharing their opinions on ragging which could also been a limitation, affecting the participants of this study. Notwithstanding, sufficiently rich information was generated. Another possible limitation could be that information divulged by the male participants could have been affected by having an all-female research team. However, it would be difficult to say if the participants, who were both males and females, would have been more comfortable sharing certain details due to the gendered roles upheld in society. Despite this, conducting participant observations, FGDs and interviews yielded insights and transcripts, that corroborated information and illuminating a deeper understanding of the dynamics of ragging. One of this study’s strengths is that it addresses staff and other work-affiliated individuals, a group not often addressed.

Conclusion

This study revealed a fragmented environment where the hierarchical power structure was inversed leaving those in official positions of authority unsupported. Through the Foucauldian lens, discourses were revealed which gave a better understanding of this insecure context where ragging is normal and necessary, and fear of reprisal is common yet voices of resistance are present. To work and survive in such a setting staff and other work-affiliated individuals were forced to adopt certain mechanisms of Selective Moral disengagement and deviate from their usual moral standards by turning a blind eye towards ragging.

Following the deaths of several university students due to ragging, general awareness of the harmfulness of this practice has been growing. Therefore, the opportunity is ripe to plan and implement both short- and long-term interventions to make the university environment feel safe not only for the students but the staff as well. This study underscores the necessity to create awareness directed at the staff and students on the harms of ragging. There is a need to look towards transforming ragging into a positive interaction between seniors and juniors. Interventions aimed at increasing the staff responsibility and accountability are essential to thereby promote ethical leadership. An integrated action plan on how to reduce ragging should involve all stakeholders such as the politicians, UGC, university administration, lecturers, where student participation is crucial. The staff could also be empowered by providing them comprehensive training in handling conflicts amongst themselves and with students. This study draws our attention to the importance of a safe and secure work environment for the students and staff, supported by clear and consistent directives to address this serious public health issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ayanthi Wickramasinghe

Dr Ayanthi Wickramasinghe is a Post-doctoral researcher in Sexual reproductive health and rights with a background in Medicine. She received her doctorate in the field of Gender Based violence at the department of Women and Children's health at Uppsala University. Her doctoral project was titled ‘Violence among University Students; exploring the phenomenon of Ragging in Sri Lanka’ which includes several articles. Her current manuscript is the third in a series of four manuscripts.

Birgitta Essén

Birgitta Essén is a Professor in International Reproductive and Maternal Health, as well as a senior researcher at the department of women and Children's health at Uppsala University. She has several research projects worldwide. She is also a researcher funded by the Swedish research council since 2011. She is also a senior consultant in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Uppsala University hospital.

Jill Trenholm

Dr Jill Trenholm is a Gestalt therapist and a registered nurse. Her PhD project investigated war rape in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. She has been a researcher working predominantly with theory, gender and health, violence and with gender and nutrition, globally. She is currently a researcher at the department of Women and Children's Health at Uppsala University, working with theory, gender and health, gender-based violence and more recently with gender and nutrition in several countries.

Pia Axemo

Pia Axemo is an associate professor of International health and a specialist in gynecology/ obstetrics. She is a senior researcher with projects in Asia and Africa in the areas of gender based violence and Sexual reproductive health and rights at the Department of Women and Children's Health at the Uppsala University. She has worked as health advisor for several international organizations such as WHO and World Bank.

References

- “Prevalence of Ragging and Sexual and Gender Based Violence.” 2022. https://www.unicef.org/srilanka/reports/prevalence-ragging-and-sexual-and-gender-based-violence.

- Ahmer, Syed, Abdul Wahab Yousafzai, Naila Bhutto, Sumira Alam, Amanullah Khan Sarangzai, and Arshad Iqbal. 2008. “Bullying of Medical Students in Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Survey.” PLoS ONE 3 (12): e3889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003889.

- Albuquerque, Carlos Linhares de, and Eduardo Paes-Machado. 2004. “The Hazing Machine: The Shaping of Brazilian Military Police Recruits.” Policing and Society 14 (2): 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/1043946032000143497.

- Allan, Elizabeth J., and Mary Madden. 2012. “The Nature and Extent of College Student Hazing.” International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 24 (1): 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh.2012.012.

- Allan, Elizabeth, and Mary Madden. 2018. “Hazing in View: College Students at Risk.” https://books.google.com/books/about/Hazing_in_View_College_Students_at_Risk.html?id=L6A06KMi-28C.

- Alwis, Malathi de. 2002. “The Changing Role of Women in Sri Lankan Society.” Social Research: An International Quarterly 69 (3): 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2002.0036.

- Arribas-Ayllon, M, and Valerie Walkerdine. 2017. “Foucauldian Discourse Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, edited by Carla Willig, 110–123. London: Sage Publications.

- Bandura, Albert. 2002. “Selective Moral Disengagement in the Exercise of Moral Agency.” Journal of Moral Education 31 (2): 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322.

- Campo, Shelly, Gretchen Poulos, and John W. Sipple. 2005. “Prevalence and Profiling: Hazing among College Students and Points of Intervention.” American Journal of Health Behavior 29 (2): 137–149. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.29.2.5.

- Cowie, Helen, and Nicky Hutson. 2005. “Peer Support: A Strategy to Help Bystanders Challenge School Bullying.” Pastoral Care in Education 23 (2): 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0264-3944.2005.00331.x.

- Dias, Diana, and Maria José Sá. 2014. “Transition to Higher Education: The Role of Initiation Practices.” Educational Research 56 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.874144.

- Due, Pernille, Juan Merlo, Yossi Harel-Fisch, Mogens Trab Damsgaard, Mag Scient Soc, Bjørn E. Holstein, Mag Scient Soc, Jørn Hetland, Candace Currie, Saoirse Nic Gabhainn, Margarida Gaspar de Matos, John Lynch. 2009. “Socioeconomic Inequality in Exposure to Bullying during Adolescence: A Comparative, Cross-Sectional, Multilevel Study in 35 Countries.” American Journal of Public Health 99 (5): 907–914. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.139303.

- Edirisinghe, P. Sudarshana. 2018. Structural Changes of Higher Education in Sri Lanka: A Study on Privatised Universities and Emerging Burdens in Free Educational System. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3607473. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3607473.

- Ekanayake, Samantha, and Chamini Guruge. 2016. “Social Stratification, Modernization and Restructuring of Sri Lankan Society.” International Journal of Arts and Commerce 5:96–107.

- Fávero, Marisalva, Sofia Pinto, Fátima Ferreira, Francisco Machado, and Amaia Del Campo. 2015. “Hazing Violence: Practices of Domination and Coercion in Hazing in Portugal.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 33 (11): 1830–1851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515619748.

- Foucault, Michel. 1969. The Archaeology of Knowledge. 2nd ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203604168.

- Gamage, Siri. 2017. “Psychological, Sociological, and Political Dimensions of Ragging in Sri Lankan Universities.” Social Affairs: A Journal for the Social Sciences 1 (7): 13–21.

- Ganguly, Sumit. 2018. “Ending the Sri Lankan Civil War.” Daedalus 147 (1): 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00475.

- Garg, Rajesh. 2009. “Ragging: A Public Health Problem in India.” Indian Journal of Medical Sciences 63 (6): 263. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5359.53401.

- Gunatilaka, Hemamalie. 2019. “Ragging; Its Evolution and Effects: A Literature Review with a Special Reference to Sri Lanka.” International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), 2454–6186. http://dr.lib.sjp.ac.lk/handle/123456789/11918.

- Hakkola, Leah, Elizabeth J. Allan, and Dave Kerschner. 2019. “Applying Utilization-Focused Evaluation to High School Hazing Prevention: A Pilot Intervention.” Evaluation and Program Planning 75:61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.05.005.

- Haney, Craig. 2016. “On Structural Evil: Disengaging from Our Moral Selves.” Edited by Danny Wedding. PsycCRITIQUES 61 (8). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040160.

- Hoover, Nadine C., and Norman J. Pollard. 2000. Initiation Rites in American High Schools: A National Survey. Final Report. New York: Alfred University.

- Huysamer, Carolyn, and Johannes Seroto. 2021. “Hazing Practices in South African Schools: A Case of Grade 12 Learners in Gauteng Province.” SAGE Open 11 (3): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211032177.

- Jayasuriya, Vathsala, Kumudu Wijewardena, and Pia Axemo. 2011. “Intimate Partner Violence against Women in the Capital Province of Sri Lanka” Violence Against Women 17 (8): 1086–1102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211417151.

- Kamala Liyanage, I. M. 2014. “Education System of Sri Lanka: Strengths and Weaknesses.” 116–140. https://www.ide.go.jp/library/Japanese/Publish/Reports/InterimReport/2013/pdf/C02_ch7.pdf.

- Killer, Brittany, Kay Bussey, David J. Hawes, and Caroline Hunt. 2019. “A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Moral Disengagement and Bullying Roles in Youth.” Aggressive Behavior 45 (4): 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21833.

- Kowalski, Robin M., Mackenzie Foster, Molly Scarborough, Leah Bourque, Stephen Wells, Riley Graham, Hailey Bednar, Madeleine Franchi, Sarah Nash, and Kelsey Crawford. 2021. “Hazing, Bullying, and Moral Disengagement.” International Journal of Bullying Prevention 3 (3): 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-020-00070-7.

- Lakshman, Iresha M. 2018. “Can Sri Lankan Teachers Afford to Spare the Rod? Teacher Attitudes towards Corporal Punishment in School.” Edited by Sandro Serpa. Cogent Social Sciences 4 (1): 1536316. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1536316.

- Lekamwasam, Sarath, Mahinda Rodrigo, Madhu Wickramathilake, Champa Wijesinghe, Gaya Wijerathne, Aruna De Silva, Mayuri Napagoda, Anoja Attanayake, and Clifford Perera. 2015. “Preventing Ragging: Outcome of an Integrated Programme in a Medical Faculty in Sri Lanka.” Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2015.059.

- Mann, Liesbeth, Allard R. Feddes, Bertjan Doosje, and Agneta H. Fischer. 2016. “Withdraw or Affiliate? The Role of Humiliation during Initiation Rituals.” Cognition and Emotion 30 (1): 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1050358.

- Mann, Liesbeth, Allard R. Feddes, Anne Leiser, Bertjan Doosje, and Agneta H. Fischer. 2017. “When Is Humiliation More Intense? The Role of Audience Laughter and Threats to the Self.” Frontiers in Psychology 8: 495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00495.

- Massey, Kyle D., and Jennifer Massey. 2017. “It Happens, Just Not to Me: Hazing on a Canadian University Campus.” Journal of College and Character 18 (1): 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2016.1260477.

- Matthews, Bruce. 1995. “University Education in Sri Lanka in Context: Consequences of Deteriorating Standards.” Pacific Affairs 68 (1): 77–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2759769.

- McCreary, Gentry, Nathaniel Bray, and Stephen Thomas. 2016. “Bad Apples or Bad Barrels? Moral Disengagement, Social Influence, and the Perpetuation of Hazing in the College Fraternity.” Journal of Sorority and Fraternity Life Research and Practice 11 (2): Article 3. https://doi.org/10.25774/PVBG-9C47.

- Mel, Neloufer de, Pradeep Peiris, and Shyamala Gomez. 2013. “Broadening Gender: Why Masculinities Matter.”

- Mendeloff, David. 2009. “Trauma and Vengeance: Assessing the Psychological and Emotional Effects of Post-Conflict Justice.” Human Rights Quarterly 31 (3): 592–623. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.0.0100.

- Murer, Jeffrey Stevenson, and Tilman Schwarze. 2020. “Social Rituals of Pain: The Socio-Symbolic Meaning of Violence in Gang Initiations.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 35 (1): 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-020-09392-2.

- Nallapu, Samson S. R. 2013. “Students Perceptions and Feedback on Ragging in a South Indian Medical College.” South-East Asian Journal of Medical Education 7 (2): 33. https://doi.org/10.4038/seajme.v7i2.138.

- Navaz, Abdul Majeed Mohamed. 2012. “Lecturer–Student Interaction in English-Medium Science Lectures: An Investigation of Perceptions and Practice at a Sri Lankan University Where English is a Second Language,” 366.

- Obermann, Marie-Louise. 2011. “Moral Disengagement among Bystanders to School Bullying.” Journal of School Violence 10 (3): 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2011.578276.

- Pai, Sanjay A., and Prabha S. Chandra. 2009. “Ragging: Human Rights Abuse Tolerated by the Authorities.” Indian Journal of Medical Ethics (2). https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2009.021.

- Premadasa, I. G., N. C. Wanigasooriya, L. Thalib, and A. N. B. Ellepola. 2011. “Harassment of Newly Admitted Undergraduates by Senior Students in a Faculty of Dentistry in Sri Lanka.” Medical Teacher 33 (10): e556–e563. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.600358.

- Ruwanpura, Eshani Samantha. 2011. “Sex or Sensibility? The Making of Chaste Women and Promiscuous Men in a Sri Lankan University Setting.” https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/6180.

- Samaranayake, Gamini. 2013. “Changing University Student Politics in Sri Lanka: From Norm Oriented to Value Orient Student Movement.” Social Affairs: A Journal for the Social Sciences 8. http://socialaffairsjournal.com/Achive/Fall_2015/3_SAJ_1(3)Samaranayaka.pdf.

- Senanayake, Hemantha. 2020. “‘Ragging’ Is Dragging Sri Lanka Down.” Daily FT, June 10. http://www.ft.lk/columns/-Ragging–is-dragging-Sri-Lanka-down/4-701376.

- Shakya, D. R., and R. Maskey. 2012. “'Ragging': What the Medical Students of a Health Institute from Eastern Nepal Say?” Sunsari Technical College Journal 1 (1): 27–32. https://doi.org/10.3126/stcj.v1i1.8658.

- Shakya, Dhana Ratna, Pramod Shyangwa, Rabi Shakya, and Chandra Agrawal. 2011. “14 Mental and Behavioral Problems in Medical Students of a Health Institute in Eastern Nepal.” Asian Journal of Psychiatry 4, S61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1876-2018(11)60234-7.

- Silva, Kalinga Tudor. 1999. “Caste, Ethnicity and Problems of National Identity in Sri Lanka.” Sociological Bulletin 48 (1-2): 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022919990111.

- Silva, Kalinga Tudor, P. P. Sivapragasam, and Paramsothy Thanges. 2009. “Caste Discrimination and Social Justice in Sri Lanka: OHCHR Library Catalogue.” Indian Institute of Dalit Studies. http://searchlibrary.ohchr.org/record/9256.

- Silveira, Jason M., and Michael W. Hudson. 2015. “Hazing in the College Marching Band.” Journal of Research in Music Education 63 (1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429415569064.

- Sri Lanka, and Department of Census and Statistics. 2017. “Sri Lanka: Demographic and Health Survey 2016.”

- Sri Lankan Government. 1998. “Prohibition of Ragging and Other Forms of Violence in Educational Institutions Act | Volume VI.” https://www.srilankalaw.lk/Volume-VI/prohibition-of-ragging-and-other-forms-of-violence-in-educational-institutions-act.html.

- Sri Lanka University Statistics. 2019. “Sri Lanka University Statistics 2019.” https://www.ugc.ac.lk/index.php.

- Staub, Ervin. 2000. “Genocide and Mass Killing: Origins, Prevention, Healing and Reconciliation.” Political Psychology 21 (2): 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00193.

- Thornberg, Robert, Tiziana Pozzoli, and Gianluca Gini. 2021. “Defending or Remaining Passive as a Bystander of School Bullying in Sweden: The Role of Moral Disengagement and Antibullying Class Norms.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37 (19-20): NP18666–NP18689. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211037427.

- UGC (University Grants Commission). 2017. Information for Students on Ragging and Gender Based Violence in Universities. Colombo: Center for Gender Equity/Eqality, University Grants Commission.

- UGC (University Grants Commission). 2020. “Redressing Victims of Ragging & Providing a Regulatory Mechanism to Prevent Ragging Related Abusive Conduct in Sri Lankan State Universities and Higher Education Institutes.” https://www.ugc.ac.lk/downloads/publications/ReportoftheRagReliafCommittee/ReportoftheRagReliafCommittee.pdf.

- UNDP, ed. 2020. The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene. Human Development Report 2020. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme.

- University of Jaffna. 2020. “University of Jaffna.” http://www.jfn.ac.lk/.

- Véliz-Calderón, Daniela, and Elizabeth Allan. 2017. “Defining Hazing: Gender Differences.” Oracle: The Research Journal of the Association of Fraternity/Sorority Advisors 12 (2): 12–25. https://doi.org/10.25774/jkyw-fh16.

- Wajahat, Ayesha. 2014. “Harassment due to Ragging.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 113:129–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.019.

- Warunasuriya, Ashanthi. 2016. “Death by Ragging.” The Sunday Leader. http://www.thesundayleader.lk/2016/05/15/death-by-ragging/.

- Weeramunda, A. J. 2008. “Socio Political Impact of Student Violence and Indiscipline in Universities and Tertiary Education Institutes.”

- Wetherell, Margaret, Stephanie Taylor, and Simeon J. Yates. 2001. “Discourse as Data.” https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/discourse-as-data/book211516.

- Wickramasinghe, Ayanthi, Pia Axemo, Birgitta Essén, and Jill Trenholm. 2022. “Ragging as an Expression of Power in a Deeply Divided Society; A Qualitative Study on Students Perceptions on the Phenomenon of Ragging at a Sri Lankan University.” PLoS ONE 17 (7): e0271087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271087.

- Wickramasinghe, Ayanthi, Birgitta Essén, Shirin Ziaei, Rajendra Surenthirakumaran, and Pia Axemo. 2022. “Ragging, a Form of University Violence in Sri Lanka—Prevalence, Self-Perceived Health Consequences, Help-Seeking Behavior and Associated Factors.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (14): 8383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148383.

- Zimbardo, Philip. 2011. The Lucifer Effect: How Good People Turn Evil. New York: Random House.