ABSTRACT

Like other conflict-torn societies, Sri Lankans have long sought to build peace through constitutional re-design with devolution of power and minority protections. However, the preoccupation with legal norms and institutions runs counter to the widely-held conviction that politicians routinely transgress norms and twist institutions. It is thus imperative to study the lived political realities of power-sharing arrangements, rather than their intended design. The 1987 Thirteenth Amendment devolved state power to the provinces to assuage Tamil separatism. The limited academic work that exists on the Provincial Council system outlines its shortcomings and failures, but there is little scholarship of the councils as a political arena in their own right. This article discusses the politics around the Eastern Provincial Council, especially the brief but unique period between 2015 and 2017 when it was run by Tamil and Muslim parties. More specifically, the empirical material pivots on three Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim Ministers in the Eastern Province and two lower-ranking Muslim politicians. The Provincial Council has very different meaning, legitimacy and utility to these diverse political figures. I argue that we must consider these diverse ethno-nationalist manifestations of provincial politics to understand what the Provincial Council system entails in Sri Lanka.

Introduction

The uneasy relationship between constitutionalism and the transgressive proclivity of democratic politics is no sign of democratic immaturity. Many supposedly advanced democracies grapple with decay of the constitutional order, perhaps most visible in the 2021 storming of the Capitol in Washington DC. In South Asia, tensions and frictions between law and politics have always been palpable. The region combines a proud tradition of constitutional order and democratic governance with a great propensity for transgressive politics (Jaffrelot and Verniers Citation2020; Jhaveri, Khaitan, and Samararatne Citation2023; Waseem Citation2012). Legal and political scholarship considers constitutional design essential in preventing and resolving violent conflicts about the nature of the state. The contours of peaceful coexistence emerge, so the reasoning goes, when belligerent parties see their political grievances addressed with the right forms of power-sharing, minority protection, devolving autonomy or shared authority to aggrieved regions, or some version of federalism (Bastian and Luckham Citation2003; Choudry Citation2008; Reynolds Citation2002). Notwithstanding the merits of this scholarship, the steadfast focus on pinning down the constitutional bounds of politics sits uncomfortably with the widespread popular conviction that politics routinely transgresses its bounds. As we know from the literature on informal politics (Klem and Suykens Citation2018; Michelutti et al. Citation2018; Spencer Citation2007; Witsoe Citation2013), effective politicians regularly tweak, bend, and break the rules. And arguably, they need to do so to be effective and they are expected to do so by their voters.

This focus on the interaction between the constitutional architecture of state institutions and the manoeuvring, jostling and trickery of electoral politics offers a helpful vantage point to consider Sri Lanka’s Provincial Councils. These councils were brought about through coercive Indian diplomacy in 1987. The North-Eastern Provincial Council (NEPC) was supposed to assuage Tamil minority grievances with a degree of autonomy, but it fell prey to a persistent stand-off between the central government and the Tamil nationalist movement.

The faults and failures of devolved government in Sri Lanka are no news (Amarasinghe et al. Citation2019; Bastian Citation1994; Welikala Citation2012; Wickramaratne Citation2014). What my analysis adds to the predominantly legal scholarship is a detailed scrutiny of the NEPC as a political arena in its own right. For all the deliberation about constitutional clauses on regional autonomy, there has hardly been any detailed interest for provincial politics and for the members of the Provincial Councils, their diverse orientations and strategies and the resulting political outcomes. An analysis of these dynamics sheds helpful light on the diverse political manifestations of a constitutional framework, and it helps us understand the paradoxes of pursuing ethno-nationalist politics in an arena that forecloses its cardinal aspirations.

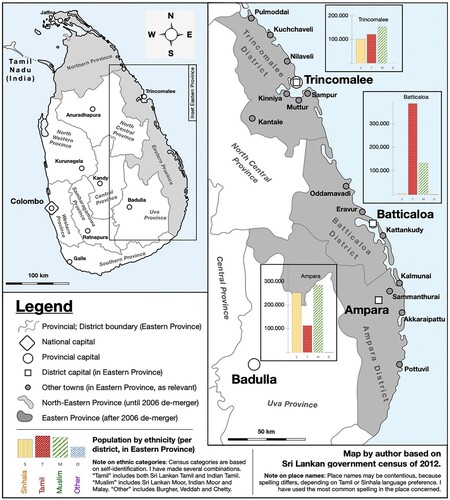

My analysis concerns the Eastern Provincial Council (dissected from the North in 2006), especially the brief but unique spell between 2015 and 2017, when it was run by a Tamil- and Muslim-dominated executive that operated in the context of an unusually permissive central government under President Sirisena. The Eastern Province is the island’s only region where the three main ethnic communities live in roughly similar proportions (see below). Most of my data are drawn from Trincomalee District, the seat of the Eastern Provincial Council, and arguably the most ethnically mixed of the province’s three districts. The Tamil and Muslim community – the national minorities for whom the Provincial Council system supposedly exists – jointly comprise a clear majority in the East, while the Sinhalese majority community comprises a regional minority. Politicians from all ethnic communities are under pressure to simultaneously do two things. They need to stand up for the socio-economic, cultural, linguistic and religious rights of their ethnic group, and they are expected to offer their constituency access to government largesse in the form of infrastructure, employment, funding and licenses. For Tamil and Muslim leaders this raises a persistent dilemma: standing up for their constituency’s minority rights pits them against the national government, but securing access to the government patronage pyramid requires pragmatic loyalty to the top. The rationale of the Provincial Council system was to break this dependency with a constitutionally anchored degree of regional autonomy, but given its weak legal, administrative, and fiscal foundations, it cannot escape from national patronage hierarchies.

To understand what devolved government entails in Sri Lanka, I argue, we must consider the diverse ways in which distinct ethno-nationalist polities engage with the Provincial Council. The official strictures of Provincial Council system are codified in the Thirteenth Amendment and concurrent legal and administrative texts. But what provincial politics actually looks like – what purpose it serves, what authority it claims, what role in has in relation to the centre – depends in great measure on how it is enacted. And as such, my article shows, the Eastern Provincial Council offers a stage for diverse political aspirations. For some it comprises a platform of dissent; for others it comprises a distribution channel for largesse; and for others yet it comprises a mounting block for aspirations of regional autonomy. Each political faction thus experiments with the Provincial Council in its own way. The utility that the council offers them stands far removed from the rationale of devolved government that was envisaged in the peace negotiations of the late 1980s and enshrined in the resulting Thirteenth Amendment to the Sri Lankan constitution.

This article builds on qualitative field research in Northeastern Sri Lanka over the period 2000–2019. I will mainly draw on interviews with political figures in Trincomalee District with different ethnic backgrounds and political orientations. These interviews were embedded in a broader fieldwork on electoral campaigning, the provincial bureaucracy, and land conflict. I have organised my empirical section around three Eastern Provincial Ministers of the period 2015–2017 and two lower-ranking politicians. These condensed encounters with politicians shift our focus from the overall tenets of Sri Lanka’s devolved system of government to the life worlds of the marginal politicians enacting this system.

Devolution, politics, and patronage

The search for a constitutional configuration that balances group interests and keeps executive power in check is a common feature of conflict-torn states as diverse as Somalia, the United Kingdom, Honduras, Iraq, Tunisia, Burundi, and Nepal. Global standards and principles of constitution-making processes have emerged (Bastian and Luckham Citation2003; Bell Citation2017; Choudry Citation2008). Constitutional experiences with federalism, electoral reform, interim arrangements, judicial review, or eternity clauses in one conflict context inform deliberations elsewhere (Rodrigues Citation2017; Sapiano Citation2017; Suteu Citation2017).

Sri Lanka is an early example of such constitutional bricolage. It has a British legacy constitution with adapted features to grapple with contextual specificities (such as the place of Buddhism), with a whiff of French presidentialism added in the 1970s, and a layer of provincial power-sharing modelled on India inserted in the 1980s (Schonthal Citation2016; Welikala Citation2012). The formidable scholarship of constitutionalism, power-sharing and peace-making in Sri Lanka has long grappled with the concept of ‘devolution’ to address ethnic minority and other grievances (Amarasinghe et al. Citation2019; Bastian Citation1994; Thiruchelvam Citation2000; Welikala Citation2012; Citation2016; Wickramaratne Citation2014, 137–250). Conciliating the separatist aspirations of the Sri Lankan Tamil minority (11 percent versus 74 percent Sinhalese, 2012 census) has been the central motive of devolving legislative, executive and juridical authority to Sri Lanka’s regions, but this combines with the objective of addressing Muslim (9 percent), Upcountry Tamil (4 percent) and other minority grievances and a more general agenda of improving democratic governance.

The notion of devolution entered the Sri Lankan constitution via the 1987 Thirteenth Amendment as a coercive implant by the federal government of India to settle Sri Lanka’s Tamil question. However, reading the texts of the Thirteenth Amendment and the Provincial Council Act elucidates very little about how Sri Lanka’s devolved government works in practice. Bell (Citation2017) argues that we must consider constitutional order in conjunction with the configuration of political elite bargains. A constitutional text is not just a ‘once-off codification’ of the understandings that underpin a constitution (Bell Citation2017, 19). Rather, constitutions are ‘tools of navigation between political and legal conceptions of the political order’ (Bell Citation2017, 20). In their study of peripheral politics postwar in Nepal and Sri Lanka, Goodhand et al. (Citation2021) adopt a similar vantage point of informal constellations of elite bargaining to account for escalations of violence. One can have meticulous debates about setting the rules of politics, but what will become of these deliberations in a context where politicians routinely tweak, of simply break, the rules? Sri Lankan politics, like South Asian politics more widely, has a transgressive propensity (Herath, Lindberg, and Orjuela Citation2019; Spencer Citation2007). Effective politicians intervene in administrative procedure, transgress institutional boundaries, redirect funding, and deploy more or less subtle forms of violence. And although this is widely perceived as a dirty business, it is what many people understand ‘normal politics’ to be (Klem and Suykens Citation2018; Michelutti et al. Citation2018; Piliavsky Citation2014; Witsoe Citation2013).

Patronage politics – a dynamic of reciprocal but unequal exchange between a patron who displays benevolence (e.g. by brokering access to state resources) and a client constituency that displays loyalty (e.g. by offering the patron a reliable vote bank) – has recently resurfaced as a phenomenon worthy of inquiry. Rather than treating it as a feudal legacy that will somehow wear off when a democratic society matures, much of the current scholarship on South Asia holds that patronage politics intermingles with modern democracy. In fact, distributing the state’s means of welfare through clientelist networks may be more effective in raising living standards than impersonal policy interventions that aspire to lofty principles but get stuck in bureaucratic mechanisms (Witsoe Citation2013). Patronage instils a form of legitimacy that is not merely transactional; it harbours its own ‘moral idiom’ (Piliavsky Citation2014, 22) where patrons see themselves obliged to display the virtues of selfless munificence and their constituents are able to demand results (Philip Citation2017). It may instil a form of populism that cuts across entrenched class divides and thus the access of ordinary people to public welfare facilities (Wyatt Citation2013).

The academic rehabilitation of patronage politics raises knock-on questions in a political context that revolves around ethno-nationalist contentions and a protracted conflict over the nature of the state. We know from experiences in India, Indonesia and elsewhere that ethnic politics and patronage politics may combine quite well, provided elite bargains and electoral arithmetic stack up (Diprose, McRae, and Hadiz Citation2019; Spencer Citation2007; Witsoe Citation2013). But what role does patronage politics assume when political mobilization does not centre on the distribution of material welfare but on more fundamental contentions over the architecture of the state, minority protection and aspirations of self-determination? The pragmatic wheeling and dealing of clientelism offers little redress to such political grievances. The rationale of patron-client relationships is ultimately agnostic to minority rights and constitutional principles. If anything, it often has majoritarian inclinations. Though Sri Lankan patronage politics conforms to some degree with ethnic (as well as class, caste and religious) lines, it ultimately produces friends and enemies of convenience, pools disparate ethnic communities and mixes constitutional layers of government. And as such it is a potential corrosive of Sri Lanka’ system of devolved government.

The tug of war over Sri Lanka’s Provincial Council system

The Thirteenth Amendment of 1987 has always been like a pebble in the shoe to Sri Lanka’s constitutional settlement. It inserted provincial devolution, as a watered-down form of shared sovereignty, into an otherwise staunchly unitary constitution, thus yielding a whole array of ambiguities, frictions, and contradictions. The central government apparatus curtailed and undercut provincial prerogatives, not just through the legal frameworks that brought the Provincial Council system into being, but also with subsequent administrative measures, fiscal adjustments, skewed resource allocation and a gradual expansion of special-mandate authorities. The Tamil nationalist movement – both the armed insurgency of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the prevalent Tamil political parties – consistently spurned the system for being a foreign dictate that failed to match their aspirations. They were deeply divided about whether to try and ameliorate it or to dismiss it altogether. The LTTE rejected the very idea of devolution as treason to the separatist cause and violently opposed the Provincial Council system (at least initially). More moderate Tamil leaders were prepared to explore space for compromise, but those who did were threatened or even killed (Kadirgamar Citation2019; Sivarajah Citation2007; Wilson Citation2000).

Sri Lanka’s Provincial Council system was ‘introduced in the most unfavorable circumstances possible’ (Shastri Citation1992, 728). It emerged out of a capsizing peace process. Determined to secure a constitutional bargain for the Tamil majority (one that stepped well short of secession), while also asserting its own status a regional power (Krishna Citation1999), the Indian federal government forced both Sri Lankan government and Tamil separatist leaders into the 1987 Indo-Lankan Accord. The resultant compromise of provincial power-sharing was codified in the Thirteenth Amendment and the Provincial Council Act. Some of the key pillars of the constitutional fix that India imposed were already scuttled in the fine print of these documents, which engrossed in ambiguities, overlaps between central and provincial prerogatives and the re-insertion of central controls over provincial staff, resources, and revenue. Perhaps most significant, the merger of Northern and Eastern Province into one North Eastern Provincial Council (NEPC) – a cornerstone of Tamil nationalist politics – was kept out of the constitutional set-up and hustled together as a provisional arrangement on wobbly legal foundations.Footnote1

After a short-lived attempt to uphold the NEPC as a credible autonomous government for the Tamil-dominated region with military and financial means, India withdrew. The LTTE, which vehemently opposed provincial devolution, overran the NEPC, drove elected councillors into exile and redeployed whatever they found in the council offices for their own state-building experiment. In 1990, two years after its creation, the NEPC became politically defunct. Throughout the war years, a minimal bureaucratic apparatus worked under the Governor, a presidential stalwart. Despite several efforts to address the shortcomings of the Thirteenth Amendment – under President Kumaratunga (mid 1990s), during the Norwegian-facilitated peace talks (2000s) and in the postwar era – the Provincial Council system has remained in check.

These efforts have fostered a lexicon of their own, and because Sri Lanka’s history of ethnic power-sharing is marred by political trickery, abrogation and deception, we should attend to specifics. Devolution can mean very different things, depending on three broad parameters. First, the geographical nature of devolution: the unit and the question of symmetry (a uniform system or a special arrangement for certain regions). The central bone of contention here is whether the unit of devolution converges with the whole Northeast (the aspired ‘Tamil homeland’) or smaller, less politically significant entities. Second, the degree of devolution: what prerogatives do devolved units have and how is their relationship with the centre defined? Third, the legal status of this design (and thus the ease with which it can be stifled or overturned): is it constitutionally anchored, a parliamentary act, a legal workaround or an informal interim arrangement? A related set of parameters concerns the terminology of devolved units (Loganathan Citation2006): are they aggrandised as ‘government’ or subjected to technical-sounding terms such as Provincial Council or local governance?

The NEPC’s interim mode – an apparatus without elected politicians – ended in 2006, after the government military drove the LTTE out of the East. The North-East merger was ruled unconstitutional. The resultant de-merger cleared the way to hold elections for the Eastern Provincial Council, thus enabling the Sinhala-nationalist Rajapaksa government to consolidate its military victory, while the war in the North continued until the 2009 defeat of the LTTE (Northern provincial elections were pushed back until 2013).

The Eastern Province, with its checkerboard geography of Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim pockets (see map), thus received its own political arena. As an elected body, the Eastern Provincial Council (EPC) has had two terms. The first council, with Pillayan (a renegade LTTE cadre that had sided with the Rajapaksa government) as Chief Minister emerged from a peculiar political constellation: the Tamil Nationalist Alliance (TNA, the premier Tamil party) boycotted the elections, while the region’s Muslim and Sinhala strongmen (and Pillayan) all aligned themselves with President Rajapaksa and competed for a nomination on his party list (Goodhand, Klem, and Walton Citation2017; Klem Citation2024). The second council comprised of two discrete phases. The EPC initially continued to function as a provincial extension of the Rajapaksa government, though there was a change of cast: Pillayan dropped out and was replaced by Majeed, a Muslim politician; the TNA participated in the polls this time but remained in the opposition. The real change took place with the presidential and parliamentary elections of 2015, which dethroned President Rajapaksa and brought to power a rainbow coalition. This drastic (but short-lived) shift in Colombo did not change the composition of the EPC but prompted a reshuffle of the executive. This yielded a political precedent: a coalition led by the two main Tamil and Muslim parties (TNA and Sri Lanka Muslim Congress) with Naseer Ahamed (SLMC) as Chief Minister. No less significant, the hawkish Eastern Governor (ex-Admiral Mohan Wijewickrama) was replaced by a well-respected veteran bureaucrat without a Sinhala nationalist profile (Austin Fernando).

When the term of Naseer’s administration ran out, in 2017, the council re-entered its interim mode (as a bureaucratic apparatus under the Governor without an elected council), from which it is yet to be resurrected. Elections were initially postponed by a reform of the electoral system that was endlessly stalled. Soon after the Rajapaksa family returned to power in 2019, the corona pandemic hit Sri Lanka, followed by an unprecedented economic nosedive in 2022, culminating into public uproar, the storming of the Presidential palace, the ousting of the government, and the establishment of a new government, which the let the Rajapaksas in through the back door (when their close ally Dinesh Gunawardena was appointed Prime Minister). Through this political rollercoaster, hopes and discussions about a constitutional reset and a more comprehensive process of ‘re-democratization’ (Uyangoda Citation2023) came to the limelight.

This prompts a new chapter in Sri Lanka’s devolution debate. This debate cannot remain confined to theoretical questions of constitutional design. It must also be informed by the lived experience of devolved government thus far, and the Eastern Province – as a multi-ethnic crucible of the country at large – is a key part of that experience. To shed light on this, my account pivots on three provincial ministers of the 2015–2017 period (Thandayathapani, Galappaththi and Naseer), who understand and approach devolved provincial government in fundamentally different ways. While their accounts are broadly reflective of Tamil, Sinhala and Muslim politics respectively, there is significant variance within these ethnic polities. In a fourth section – placed between Galappaththi’s and Naseer’s account – I will attend to two lower-ranking Muslim politicians (Abdullah and Nishardeen) and their interaction with a major Sinhala strong man (Punchinilame) to illustrate the jostling around ethnic minority politics.

Thandayuthapani: governing a ‘leaky boat'

On first glance, there was nothing spectacular about meeting S. Thandayuthapani during his time as the Provincial Minister of Education (2015–2017) in his office on Orr’s Hill, Trincomalee. There was a waiting room with people queuing to see him, with the Ministry’s Secretary acting as a gatekeeper to the minister’s office. There was big desk, plenty of binders and paraphernalia, and an attendant serving milk tea. When I interviewed Thandayuthapani about current developments in the province (which I did three times over his term as minister), he would educate me on administrative obstacles and political tussles – he often knew the answers from the top of his head and if not, he would instruct one of the bureaucrats to get a file or gave me the phone number of a next person to speak to.

While all of this may seem routine, it was remarkable when placed in the broader history of Tamil nationalist politics. Encountering a Tamil nationalist governing a state office was far from routine. And being able to ask critical questions about controversial government activities in Eastern Sri Lanka and getting mostly straightforward answers from a minister was plain startling. Thandayuthapani generously elucidated the impotence of the provincial government. I had been following the stand-off over military land occupation and resultant conflicts with displaced Tamil communities, most significantly in Sampur, which had been displaced by a special military economic zone. My earlier attempts at asking even subtle questions from different kinds of state authorities had at best resulted in vacuous responses (and at worst in tirades). But when I asked Thandayuthapani, he would eagerly review the key issues, show me maps, explain which authority was doing what, and what legal or administrative scheming was involved.

The fact that Thandayuthapani had taken charge of a provincial ministerial post was itself peculiar. He belonged to the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), a coalition of several Tamil parties around the Federal Party (the mainstay of Tamil nationalist politics), which had vehemently rejected the Provincial Council system as a feeble compromise that would thwart the Tamil cause rather than offer any redress. Tamil nationalists had explicitly boycotted the 1988 NEPC elections and the 2008 EPC elections. Even when the TNA reluctantly agreed to participate in the 2013 Northern Provincial Council elections, not least to avoid being outflanked by rival Tamil parties, they made it a point to highlight the inadequacies of the office they now governed. In his inaugural speech, the Northern Chief Minister Vigneswaran compared the council to a ‘leaky boat’ that was good for nothing and many of the council’s resolutions covered issues that it had no mandate on, but which made good publicity, by accusing the government of war crimes and genocide and reiterating an agenda of Tamil self-determination. The TNA primarily used the Provincial Councils to amplify dissent.

A year before the Northern election, in 2012, the TNA participated in the Eastern elections and Thandayuthapani became the provincial Leader of the Opposition. However, with the 2015 political landslide in Colombo, the TNA and SLMC joined hands, Naseer (SLMC) became Chief Minister and Thandayuthapani was appointed Education Minister. One of the key shifts on the ground occurred in Sampur. With a more amenable central government and a new, supportive Governor, the special zone was at long last overturned and Sampur’s inhabitants (who had been in camps for a decade) returned to the rubble that was once their home (for detailed discussion on the Sampur case, see Caron Citation2016; Fonseka and Raheem Citation2009; Klem Citation2014; Klem Citation2024; Klem and Kelegama Citation2020). The TNA had consistently sided with this displaced community, not least because Sampur lay in TNA leader Sampanthan’s home district Trincomalee. The return to Sampur was their success too, and this was the time to show it. As provincial minister with personal connections to the Sampur community, Thandayuthapani was in a key position to do so. However, there were some snags in the portfolio he had been given, as he explained to me when we met in his office. Land administration, a crucial and controversial dossier in Eastern Sri Lanka, used to be under Education, but when Thandayuthapani assumed office, it had been moved to the Roads ministry, which was under a Sinhala minister (Galappaththi, whom we will encounter below).

Resettlement, however, was still Thandayuthapani’s responsibility. Given that Sampur had been heavily bombarded and bulldozed, this was an important portfolio. The TNA’s strategy of exhibiting the uselessness of devolved government was no longer expedient. The politics of the day called for tangible results. The TNA needed to demonstrate that it did not just stand alongside its Tamil voters to scold the central government in case of injustice, but that it could rehabilitate villages, roads, public facilities, and paddy fields. As we were discussing this, Thandayuthapani passed an A4 print-out with financial stats across his desk. The provincial budget for resettlement was 17 mn Rupees (∼ 0,1 mn euro) – a drop in the ocean. The vast majority of resettlement funds was controlled by the central line ministry. There were a few foreign donors who were prepared to step in, but those were also required to operate through the centralised hierarchy.

Thankfully, for Thandayuthapani, there was an administrative loose end. Some money was left over in a World Bank project. It wasn’t quite designed for what he wanted to do but with some creative adjustment, 297 mn Rupees (∼ 1,8 mn euro) could be channelled to the reconstruction of roads, schools and health centres in Sampur. This was a modest success for Thandayuthapani as a provincial minister, but it did not resolve his awkward position. His small contribution to Sampur’s reconstruction had little to do with putting Sri Lanka’s system of devolved government to use by actioning provincial prerogatives. In terms of delivering structural patronage to the vote banks of the whole Eastern Province, he was completely outflanked. The lack of patronage did not go unnoticed in the Sampur constituency. TNA party organisers told me that popular support for the party was waning. During the war and its immediate aftermath, Tamil voters clung to the TNA as the only voice of opposition towards an authoritarian government, but now they were expecting the party to offer them help. Other constituencies received new roads, facilities, and job opportunities, but TNA leader Sampanthan only came to his district for elections and temple festivals.

Galappaththi: delivering patronage with ‘whoever comes to power'

Ariyawathi Galappaththi – Thandayuthapani’s fellow provincial minister, responsible for Roads Development – catered to her Sinhala constituency. In October 2018, I visited her office next to the fish market. The building was painted in a tint that a paint catalogue would list as navy or indigo but which Sri Lankans would instantly recognise as SLFP blue, the brand colour of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (purportedly the left-leaning of what were once Sri Lanka’s two mainstream parties). Squashed on a narrow plot between neighbouring blocks, the building reflected her socio-economic profile. Steep, uneven stairs across a small farrago of storeys led to the top floor where Galappaththi held her office – though ‘office’ is perhaps a misleading word: there were no dividing walls, piles of stuff to be distributed littered the various corners, and the only furniture was a large plastic table with chairs. This was a place for people who roll up their sleeves to get stuff done, not for people who like to sit back in velvet seats to ponder constitutional philosophy. The only tidy thing about the office was the photo gallery on the walls around us. The snapshots with Galappaththi meeting higher-ups in Sri Lanka’s political food chain, most prominently former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and his brothers Basil and Gotabaya, offered a backdrop of political accomplishment.

Galappaththi was born on the south coast, but her father married her to a Trincomalee resident. She was widowed early, but even before that she made her living with hard work and dedication, she emphasized. Her personal slogan was: ‘I am one lady, but a strong lady.’ To get by, she started a kottu roti stand. She made a chop-chop sound and gesture, as she recalled the old times with a smile. Kottu roti, a dish with shreds of dough, vegetables, meat and spices chopped on a hot metal plate, is working-class street food – the loud banging of metal blades on the hotplate is characteristic of urban evening atmosphere. This background earned her the political nickname kottu roti Ari akka. Ari is short for her first name Ariyawathi and akka means sister. Ari akka is what you would call your older sister Ari in an informal context. Kottu roti Ari akka is an epithet of a simple woman, and she carried it like a badge of honour, though some of her enemies used the reference to plebeian cookery as a pejorative.

As a political figure, Kottu roti Ari akka could rise above her direct social network (securing the ten to fifteen thousand votes needed for a Provincial Council seat), but she was a size too small to become a Member of Parliament, which requires about twenty thousand in Trincomalee District. She started her political career in the 1980s, following in her late husband’s tracks. He was a staunch supporter of the United National Party (UNP, the right-leaning mainstream party), and she initially ran for that party in local elections. She also campaigned for the UNP presidential candidate Ranil Wickremesinghe (who lost to Rajapaksa) in 2005. Like so many, she switched sides after that and ran for Rajapaksa’s SLFP. She won a seat in the Eastern Provincial Council in 2008 but was outflanked by two Sinhala strongmen (MKADS Gunawardena and Susantha Punchinilame) in the 2010 parliamentary elections. After defaulting the Rajapaksas and switching to President Sirisena’s camp, she became Road Development minister for the Eastern Province in 2015.

When I asked about her switches of allegiance, she reviewed her experiences with Wickremesinghe, Rajapaksa and Sirisena and summed up her philosophy with the words, ‘whoever comes to power, I will give them my full support. To do something for the people.’ She went on to explain that she is well positioned to connect people and government as a strong woman who is rooted in her constituency. She knew the ruling government might not last (though nobody could have foreseen President Sirisena’s ‘self-coup’ later that week). ‘The person who is coming [whoever wins nationally] will recognise my talent. Whoever it is, they will call on me.’ I knew that this was how patronage politics worked, but I was slightly taken aback by her candidness – most politicians feel the need to couch such logics in some semblance of principle or loyalty. Looking at her hall of fame, I noticed that she wore the same dress on every occasion, that day included: a simple but eloquent gown with a chequered pattern in the familiar hue of SLFP blue. I afforded myself a small jest – conversations about political scheming are best kept light in my experience – when I said that she might need to get herself a new dress if she swapped back to the UNP. Her assistants laughed with amusement, but she was dead serious when she responded: ‘I have this dress in many different colours.’ The chameleonic qualities of patronage politics were clearly no embarrassment to her. It is what she does. Parties affiliations are moving parts of the patronage machine, means to an end.

What piqued my attention was her conviction that the same is true for constitutional layers of government. The central part of our interview went as follows:

What is your opinion on the Provincial Council system?

A reason is there, but people have to use it properly.

What then is the reason?

There are three or four districts in a province. Each district needs to have a minister, so that they can help everyone in a proper way. If the Provincial Council is not needed, then another person must be there to lead each district. If they take it out, they should create a different layer. To address our problems. Then for each district there will be a person to the problem. That way money can be saved.

For people like Sampanthan and Vigneswaran [the key Tamil nationalist figures], the Provincial Council may have a different purpose.

I target all the people, without looking at race or religion. There should be no borders, no race. Sampanthan and Vigneswaran back the Tamils. This is a small island. Under one flag and under one shelter. All should live together. If I give a housing project, all people should benefit. All should be shared.

Galappaththi’s reading of the councils as just another layer for spreading benefits instils a contrarian version of decentralisation as a form of subsidiarity: distributing development at the lowest-possible level of government, in closest proximity to the people. Importantly, one does not need Provincial Councils to honour such subsidiarity principles. Members of Parliament and line ministries are quite proficient at distributing state benefits. These ministries operate through the administrative hierarchy with its nerve centre at the district level. Because of these linkages, the district bureaucracy (the kachcheri) is more powerful and better resourced than the province, though in practice, patronage politics percolate the Provincial Councils too. The imperative of better distributing development opportunities by spreading state largesse across constituencies resonates with President Rajapaksa’s post-war sinister attempt to declare ethnic differences redundant (Wickramasinghe Citation2009). What is presented as a call for fairness and equality in effect denies the basic validity of ethnic minority grievances. What startled me about Galappaththi was the fact that she did not use this as a discursive smokescreen for a Sinhala nationalist agenda. This is simply what she understood politics to be. And in terms of how the Eastern Provincial Council came to function over the years, she was to a large degree correct.

Abdullah, Nishardeen and Punchinilame: inter-ethnic patronage and camouflage politics

For politicians who represent an ethnic minority constituency, it is more difficult to embrace Galappaththi’s pragmatism of working with whomever comes to power. While Tamil and Muslim voters expect their politicians to secure opportunities for state employment and infrastructural funding, they also call on their leaders to defend ethnic minority concerns and offer protection against the dominance of the Sinhalese community. The competing logics of protecting ethnic minority rights and brokering patronage coexist within the same institutional landscape, and effective political operators need to be able to master both repertoires. This requires a high degree of discursive flexibility and adaptability.

Historically, Muslim politicians have taken more moderate positions than Tamil nationalists, and as such, they have been much more successful in securing ministerial posts and associated access to patronage. Though Muslim politicians derive legitimacy from their developmental feats, they also receive near-continuous flak for failing to protect minority rights when it matters most. They can deliver a brand-new carpet road, but when Muslim lands are under threat, when radical Buddhist monks make furore about sacred Buddhist sites, or when Sinhala extremists perpetrate anti-Muslim violence, the creed of Muslim leaders are often mute, divided or otherwise unable to defend collective Muslim interests (see also Hasbullah and Korf Citation2013; Klem Citation2011; Nuhman Citation2002).

The tensions between patronage politics and a more principled ethnic minority politics are even more visible among Muslim politicians from small constituencies, who lack the clout to become an effective big man. I will illustrate this based on my encounter with two Muslim politicians from one small town. One, whom I will call Nishardeen, was elected as a Provincial Councillor; the other, whom I have called him Abdullah elsewhereFootnote2, got stuck at a lower level, as the elected chairman of the Pradeshiya Sabha. Nishardeen and Abdullah were patronage rivals, elbowing into the same hierarchies, but they shared an agenda of Muslim minority grievances. The chameleonic nature of their politics became dramatically visible when we jointly encountered their main political paymaster in 2013. This powerful Sinhala politician, further up the patronage pyramid, was called Susantha Punchinilame. They were apprehensive about Punchinilame’s politics but they saw no option but to align themselves with him.

Like Ari akka, Punchinilame was a Sinhala politician who had once been with the UNP but closely aligned himself with the Rajapaksa government after the war. Unlike her, he may aptly be labelled a big man (of the kind described by Michelutti et al. Citation2018). His political potency encompassed both the ability to tap into top-level patronage networks and the ability to intimidate people. In the postwar years, he became the District Minister for the national Nation-Building department. This entity, which was headed by the president’s brother Basil Rajapaksa, was the patronage powerhouse within the Rajapaksa government, bypassing other layers of government, most obviously the provinces. Fittingly, Punchinilame translates as ‘little sir’: a man of small posture whose formidable political muscle commanded the respect of a lord. He was on precisely the same side as Galappaththi: part of the same ethnic group, in the same party, in the same district. And because of that, as the unwritten laws of patronage politics go, they were archenemies. I followed Punchinilame’s spectacular campaign and his ability to impress voters by fixing virtually anything with a simple phone call during the 2010 parliamentary elections (see Klem Citation2015), but I only met him in 2013.

To be exact, we did not meet him; he came to check on us. I was visiting Abdullah’s house along with a colleague and an assistant. In this period there was ubiquitous anxiety about militarisation and various forms of land occupation through military zones, sacred Buddhist sites and development schemes (Hasbullah and Geiser Citation2019; Hasbullah and Korf Citation2013; Klem Citation2014; Satkunanathan Citation2016; Spencer et al. Citation2015). The Muslim community was deeply concerned about these Sinhala nationalist forms of land grabbing. Abdullah had invited Nishardeen as well as a religious leader and farmers who had recently been evicted from their lands. Between them, they offered a vivid rendition of the Muslim plight in their locality.

The Muslim farmer told us in detail how his family plot, which they had owned for generations, was vulnerable because the registration of land titles had been wrecked by the war. Now government administrators were pushing him and his family to vacate his land, and navy men of the adjacent camp intimidated them. Afraid of what might happen in such a remote place during hours of darkness, they decided to spend the nights with relatives in town. One morning when they came home to work their paddy fields, the barbed wire of the navy camp had been moved and now encircled their land. A sign in front of his house read ‘no admittance, navy personnel only.’ A few miles down the road, belligerent Sinhala monks were claiming a purportedly ancient Buddhist site and called for the surrounding paddy fields of Muslim farmers to be handed over. When the survey department came to conduct a land survey, the people knew they had to act quickly or face the consequences of whatever lay of the land the department would officialise, so they took to the streets and protested. As frontmen of the protest, Abdullah and Nishardeen were arrested and released on bail. The fact that Nishardeen was an elected member of the Eastern Provincial Council did not stop the police from waylaying him. Abdullah and Nishardeen were desperate to find justice, but there was no feasible alternative to aligning oneself with the ruling party, Abdullah wryly explained: ‘in the opposition we can’t oppose the government.’ And such alignment was conditional on not questioning the government’s Sinhala nationalist outlook.

Just as that message dawned on us, we heard a small disturbance outside Abdullah’s house. Somebody had come. One of the boys in the garden came running into our room, whispering in a panicked voice, ‘minister, minister, minister!’ What happened next reminded me of a sudden change of scene in theatre, where everyone (except us) knows exactly what to do, or a James Bond movie where someone disappears through a revolving wall. Abdullah rushed out to meet Minister Punchinilame, whose small motorcade with henchmen and bodyguards filled the front yard. By the time they came to the living room – Punchinilame with the slow, steady pace of a visitor with gravitas – everybody else had disappeared through the private quarters of the residence and the kitchen back door. The domestic worker had rushed through the room, collecting all the half-empty cups of tea and small bites, moving chairs away, ruffling up pillows, taking the tablecloth to shake off the crumbs, putting it back and placing the vase with fake flowers where it had been. And there we were, sitting by ourselves, when the minister came in to shake hands and we had a polite chat. It was make-believe from both sides, as became clear a few minutes later, when he displayed his subtle ability to intimidate. He received a phone call and his brief Sinhala responses suggested someone was filling him in on the dubious visa status of an unmentioned foreigner. We later learned that Mr. Punchinilame’s visit was not coincidental – a rival Muslim politician had tipped him off.

If the act before this theatrical scene transition had been a performance of Muslim minority politics with its detailed narrative of land, genealogy, grievances and calls for justice, the act after the shifted mise en scène was a performance of the contrarian repertoire of inter-ethnic patronage politics. In this latter political idiom, ethnic minority grievances are taboo and all that really matters is reaching out to the halls of power to ‘do something for the people.’ Abdullah knew that he had been found out. He blushed and smiled frantically. But then he skilfully switched vocabulary and speaking points to mitigate the awkward situation. We talked about the Northern Provincial Council elections which were reaching their climax not far from where we were. Punchinilame conceded this was an uphill battle given the Tamil signature of the North, but the government coalition was doing its best to showcase the incredible developmental benefits and poverty relief that he himself had brought to the Eastern Province. Abdullah added that he was part of the campaign effort and would travel up North the following day to canvas. The cogs of my brain grinded for a second. He was actively calling on people to vote for the government in another province, though that very same week he had been arrested in his own province by that same government for leading a protest march against government-sponsored occupation of Muslim lands.

Naseer: applying the spirit of the Thirteenth Amendment

While this was an exceptionally dramatic display of the tensions between ethnic grievances and patronage politics, the basic challenge of having to master both political repertoires and manage both sets of networks is routine for all Muslim leaders in Eastern Sri Lanka. The above incident was illustrative of the militarised tension of the immediate postwar years, but the 2015–2017 period offered a brief window of opportunity, particularly for Muslim leaders with more political clout, like Naseer Ahamed, Chief Minister in these final two years of the EPC’s tenure. The Rajapaksa government had collapsed, and President Sirisena’s ‘good governance’ assumed office with the explicit ambition to combine equitable development with redress of ethnic grievances. It became possible for Tamil and Muslim leaders to envisage a convergence between patronage and minority interests, but this required an approach that combined principled stances with pragmatism. As Chief Minister, Naseer parted from the wholesale pragmatism of his predecessors, Pillayan and Majeed, who had by and large served like muted extensions of the Rajapaksa patronage machine. At the same time, he steered clear of the staunchly oppositional course that Chief Minister Vigneswaran had adopted in the Northern Province. Rather than seeking to demonstrate the deficiency of the Provincial Council, Naseer’s council set out to find practical ways of making a material difference to Eastern communities without sacrificing the spirit of devolution.

As a long-standing Sri Lanka Muslim Congress member and deputy leader of the party, Naseer had the credibility of a dedicated Muslim leader, but he had never antagonised the Tamils. Unlike SLMC leader Rauff Hakeem (from Kandy), he was unmistakably a man from the East. His home was in Eravur, and his ways, dress and Tamil dialect resembled those of the region, not those of the national elite. But at the same time, he was a successful entrepreneur who spoke fluent English and Sinhala and who had good networks with high-level civil servants and politicians in Colombo. I met Naseer in 2018 (a year after his council’s term had ended) at the SLMC headquarters in Kompannavidiya, a central part of the capital that has long been home to the ethnic minorities who were crowded out by the expanding real estate of the defence establishment and malls. The SLMC office, a small run-down flat on a minor backroad, held its ground amidst these shiny new towers. As I arrived, he was in a meeting with party members and Tamil and Muslim bureaucrats who had come from the East to discuss the construction of a new market in Naseer’s natal town of Eravur. Ledgers with files, letters, excel sheets and street-plan designs were moved around the table as they discussed how to move their plans through the administrative apparatus, with all its competing layers and overlapping sectoral divisions. They talked in Tamil with an occasional English phrase. ‘Bureaucrats will be bureaucrats,’ Naseer told his visitors as he concluded the meeting, ‘but Sarath will be fine,’ referring to Eastern Province Chief Secretary Sarath Abayagunawardana. On that note of reassurance, they wrapped up with a polite thanks to their chairman and made their way out into the late afternoon heat, folders and to-do-lists tucked under their arms.

Pushing back against the appropriation of funds and powers by line ministries in Colombo had been the central part of his job as Chief Minister, Naseer explained in the subsequent interview. ‘Education is a 95 per cent devolved subject, but 90 per cent of the education budget is allocated to the [national] education ministry.’ The national government spends large amounts of money in the Eastern Province, but these funds do not flow through the council. In fact, central ministries may not even inform the council about it. ‘It was a big struggle. But I have some influence with central ministries. I know all the ministers and secretaries, so I can approach them personally.’

The centrepiece of Naseer’s ambition was to create an investment authority for the East to attract foreign capital for all sectors of the economy by simplifying procedures for international companies. Naseer explained, ‘the process will go and go. In the end the investor runs away with the speed of Usain Bolt.’ His term was too short to see this through, but he had not given up. I suggested that there has also been a level of efficiency under the (central) nation-building ministry of the Rajapaksa government (of which Punchinilame had been a part). ‘That was a dictatorship government!’ he shot back. ‘That was the central government doing these things without the Provincial Council. But when I came to power, we pushed the other way.’ He prided himself in having some modest success, but he added with a sigh: ‘All that pushing. That is not what the Provincial Council should be about. Those rights are given in the constitution, but I had to do all that. I can’t keep running after each of these incidents forever. I can give you a hundred examples.’

The heart of the matter, in his view, was to assure the implementation of the constitution, particularly the Thirteenth Amendment on devolved governance. The problem with the Tamil parties was that they were completely preoccupied with bargaining for a new arrangement that might never come, while they failed to use the opportunities under the present setup. TNA leader Sampanthan had been heavily involved in consultations and negotiations with the Sirisena government in the period 2015–2017, but after the initial enthusiasm the process ran into some very familiar obstacles of constitutional constraint, electoral pressures and party-political rivalry. ‘The whole debate on constitutional reform is a delaying tactic,’ Naseer posited. ‘Go for full implementation of the Thirteenth Amendment. Finish this first. Then think about things you might change, if you want more.’ That way, there would be no need for complicated legal procedures, a two-thirds majority in parliament or even a popular referendum, all of which would promulgate Sinhala nationalist opposition. ‘The key thing is to work with what we have. I have been trying to convince my friends in the TNA: let’s work with what is in the constitution. If they don’t even give you that, why waste your time on expecting even more.’

Conclusions

Sri Lanka’s Provincial Council system was created under Indian duress to assuage ethno-nationalist conflict by devolving state power to the regions. Its failure to do so was clear soon after (if not at) its inception in the late 1980s, and since then constitutional lawyers and peacebuilding specialists have debated shortcomings, redressive amendments and constitutional resets. Moving beyond the state’s institutional architecture, I have argued that we must focus on what devolved government entails as a lived political reality. This requires an appreciation of the diverse ways in which distinct ethno-nationalist polities engage with the Provincial Council system. My article has discussed the political manifestation of the Eastern Provincial Council, particularly its final years (2015–2017) which were arguably the most conducive for devolved government and ethnic minority politics.

The provincial politicians I have described adopted radically different strategies in relation to the Provincial Council. Thandayathapani reluctantly claimed executive power in the province and used it as an elevated platform to stage opposition to the government, but when confronted with acute needs, such as resettlement in Sampur, he came under pressure to deliver resources. Galappaththi, locally known as kottu roti Ari akka, represents the quintessence of a pragmatic Sinhala patronage broker. To her, the Provincial Council is just one of several institutional trappings to distribute largess. For Abdullah and Nishardeen a seat in the Provincial Council represents a mandate to advocate people’s rights while bargaining for material support, but because those two agendas often clash, they engage in camouflage politics, which then becomes exposed when they need to show their colours – for example because their political paymaster rocks up unexpectedly. For Naseer, finally, the Provincial Council represents the promise of the Thirteenth Amendment. Like Galappaththi, he will try to ‘do something for the people’, but to him the constitutional devolution of power is no mere machinery to dispense patronage; delivering results to the people ought to bolster the legitimacy and credibility of the Provincial Council.

Due to these divergent political practices, the Eastern Provincial Council is many things at once: a platform for minority dissent, a channel to distribute state resources, and an incipient form of provincial autonomy. There is a clear ethnic signature to these renditions – the belligerence, pragmatism and chameleonic jostling towards the Provincial Council is common among Tamil, Sinhalese and Muslim politicians respectively. But this is far from absolute. Camouflage politics and principled dissent also occur among Sinhalese politicians when it comes to internally divisive issues, and some Tamil politicians have become proficient patronage operators, especially those that dropped out of the main Tamil nationalist movement.

This article’s title ‘Unravelling the constitutional settlement’ alludes to the double meaning of the first word. It seeks to untangle and understand the nature of provincially devolved government in Sri Lanka, as encoded in the Thirteenth Amendment. And it describes how this arrangement of regional autonomy as an antidote to the island’s ethno-national conflict has fallen apart. After a mere eight years of electoral rule, both the Northern and the Eastern Provincial Council have re-entered their ‘interim mode’ (this time along with the other seven provinces): a bureaucratic mode of conduct under an unelected Governor. This turns the Provincial Councils into extensions of the central government and curtails all the above political strategies – staging dissent, leveraging patronage, nurturing provincial autonomy.

While pragmatic patronage politics could be seen as an effective and to some degree legitimate use of regional governance, as has been argued elsewhere (Diprose, McRae, and Hadiz Citation2019; Michelutti et al. Citation2018; Piliavsky Citation2014; Witsoe Citation2013 ), it arguably makes the Provincial Councils redundant. District MPs, for one, are typically proficient at delivering patronage – one does not need a whole layer of provincial government. The Provincial Council system exists, because the devolution of power from the centre to the provinces was supposed to assuage Tamil ethno-nationalism and accommodate the separatists within a comprise of regional autonomy and an (implied) notion of shared sovereignty. If the Sri Lankan polity decides to retain the devolution of power – as it resurrects itself from the current economic, political and constitutional crisis – it should make sure that the parameters of that system fit its purpose. What that means is evidently a loaded political question, but it would arguably require a smaller number of larger provinces with a greater degree of autonomy, the abolishment of central controls over provincial prerogatives and vaguely defined shared responsibilities, as well as firm anchoring in the constitution and both legal and political channels to resolve disputes between the centre and provinces. Much in line with my analysis above, the provinces would remain a diverse arena with competing renditions of politics, but it would be an arena with more clearly defined boundaries. These suggestions, which resonate with well-rehearsed debates (Amarasinghe et al. Citation2019; Bastian Citation1994; Thiruchelvam Citation2000; Welikala Citation2012; Citation2016; Wickramaratne Citation2014), are highly controversial, but arguably Sri Lanka’s present crisis offers an opportunity to extract the question of devolution from the sphere of (perceived) zero-sum ethnic bargaining into a much broader sphere of re-democratizing Sri Lanka and improving the quality of governance for its citizens across the island (Jhaveri, Khaitan, and Samararatne Citation2023; Uyangoda Citation2023).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bart Klem

Bart Klem is an associate professor at the School of Global Studies, Gothenburg University. His research focuses on civil war, postwar transition and contested sovereignty. His new book with Cambridge University Press adopts a performative perspective on the frictions and contradictions around the Tamil nationalist movement in Sri Lanka.

Notes

1 The imperative for the president to effect the merger of the Northern and Eastern Province was made subject to security considerations through the Public Security Ordinance (Amarasinghe et al. Citation2019, 12–14).

2 Abdullah’s experiences were previously discussed in my contribution to Goodhand, Klem, and Walton (Citation2017), but the analytical framework differed from my account in this text.

References

- Amarasinghe, Ranjith, Asoka Gunawardena, Jayampathi Wickramaratne, A. Navaratna-Bandara, and N. Selvakkumaran, eds. 2019. Thirty Years of Devolution: An Evaluation of the Workings of Provincial Councils in Sri Lanka. Colombo: ICS.

- Bastian, Sunil. 1994. Devolution and Development in Sri Lanka. Colombo: ICES.

- Bastian, Sunil, and Robin Luckham. 2003. Can Democracy Be Designed? The Politics of Institutional Choice in Conflict-Torn Societies. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Bell, Christine. 2017. “Introduction: Bargaining on Constitutions – Political Settlements and Constitutional State-Building.” Global Constitutionalism 6 (1): 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045381716000216

- Caron, Cynthia. 2016. “The Subject of Return: Land and Livelihood Struggles for Place and Citizenship.” Contemporary South Asia 24 (4): 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2015.1098589

- Choudry, Sujit. 2008. Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation? New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Diprose, Rachael, Dave McRae, and Vedi Hadiz. 2019. “Two Decades of Reformasi in Indonesia: Its Illiberal Turn.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (5): 691–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2019.1637922

- Fonseka, Bhavani, and Mirak Raheem. 2009. Trincomalee High Security Zone and Special Economic Zone. Colombo: CPA.

- Goodhand, Jonathan, Bart Klem, and Oliver Walton. 2017. “Mediating the Margins: The Role of Brokers and the Eastern Provincial Council in Sri Lanka’s Post-war Transition.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal 1 (6): 817–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2016.1302816

- Goodhand, Jonathan, Oliver Walton, Jayanta Rai, and Sujeet Karn. 2021. “Marginal Gains: Borderland Dynamics, Political Settlements, and Shifting Centre-Periphery Relations in Post-War Nepal.” Contemporary South Asia 29 (3): 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2021.1937060

- Hasbullah, Shahul, and Urs Geiser. 2019. Negotiating Access to Land in Eastern Sri Lanka: Social Mobilization of Livelihood Concerns and Everyday Encounters with an Ambiguous State. Colombo: ICES.

- Hasbullah, Shahul, and Benedikt Korf. 2013. “Muslim Geographies, Violence and the Antinomies of Community in Eastern Sri Lanka.” The Geographical Journal 179 (3): 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2012.00470.x

- Herath, Dhammika, Jonas Lindberg, and Camilla Orjuela. 2019. “Swimming Upstream: Fighting Systemic Corruption in Sri Lanka.” Contemporary South Asia 27 (2): 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2019.1579171

- Jaffrelot, Christophe, and Gilles Verniers. 2020. “A New Party System or a New Political System?” Contemporary South Asia 28 (2): 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2020.1765990

- Jhaveri, Swati, Tarunabh Khaitan, and Dinesha Samararatne, eds. 2023. Constitutional Resilience in South Asia. London: Bloomsbury.

- Kadirgamar, Ahilan. 2019. “Tamil Nationalism, Political Parties, and War-Torn Political Culture.” In In Political Parties in Sri Lanka: Change and Continuity, edited by Amita Shastri and Jayadeva Uyangoda, 222–242. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klem, Bart. 2011. “Islam, Politics and Violence in Eastern Sri Lanka.” The Journal of Asian Studies 70 (3): 730–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002191181100088X

- Klem, Bart. 2014. “The Political Geography of War’s End: Territorialisation, Circulation, and Moral Anxiety in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka.” Political Geography 38 (1): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.10.002

- Klem, Bart. 2015. “Showing One’s Colours: The Political Work of Elections in Post-War Sri Lanka.” Modern Asian Studies 49 (4): 1091–1121. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X13000528

- Klem, Bart. 2024. Performing Sovereign Aspirations: Tamil Insurgency and Postwar Transition in Sri Lanka. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Klem, Bart, and Thiruni Kelegama. 2020. “Marginal Placeholders: Peasants, Paddy and Ethnic Space in Sri Lanka’s Post-War Frontier.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (2): 346–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2019.1572604

- Klem, Bart, and Bert Suykens. 2018. “The Politics of Order and Disturbance: Public Authority, Sovereignty and Violent Contestation in South Asia.” Modern Asian Studies 52 (3): 753–783. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X17000270

- Krishna, Sankaran. 1999. Postcolonial Insecurities: India, Sri Lanka and the Question of Nationhood. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Loganathan, Ketesh. 2006. “Indo-Lanka Accord and the Ethnic Question: Lessons and Experiences.” In Negotiating Peace in Sri Lanka: Efforts, Failures and Lessons, edited by Kumar Rupesinghe, 69–102. Colombo: Foundation for Coexistence.

- Michelutti, Lucia, Ashraf Hoque, Nicolas Martin, David Picherit, Paul Rollier, Arild Engelsen Ruud, and Clarinda Still. 2018. Mafia Raj: The Rule of Bosses in South Asia. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Nuhman, M. 2002. Understanding Sri Lankan Muslim Identity. Colombo: ICES.

- Philip, Jessy K. 2017. “‘Though He Is a Landlord, That Sarpanch Is My Servant!’ Caste and Democracy in a Village of South India.” Contemporary South Asia 25 (3): 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2017.1353951

- Piliavsky, Anastasia, ed. 2014. Patronage as Politics in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Reynolds, Andrew. 2002. The Architecture of Democracy: Constitutional Design, Conflict Management, and Democracy. London: Oxford University Press.

- Rodrigues, Charmaine. 2017. “Letting Off Steam: Interim Constitutions as a Safety Valve to the Pressure-Cooker of Transitions in Conflict-Affected States?” Global Constitutionalism 6 (1): 33–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045381716000241

- Sapiano, Jenna. 2017. “Courting Peace: Judicial Review and Peace Jurisprudence.” Global Constitutionalism 6 (1): 131–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045381716000253

- Satkunanathan, Ambika. 2016. “Collaboration, Suspicion and Traitors: An Exploratory Study of Intra-Community Relations in Post-War Northern Sri Lanka.” Contemporary South Asia 24 (4): 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2016.1252315

- Schonthal, Benjamin. 2016. “Environments of Law: Islam, Buddhism, and the State in Contemporary Sri Lanka.” The Journal of Asian Studies 75 (1): 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911815002053

- Shastri, Amita. 1992. “Sri Lanka's Provincial Council System: A Solution to the Ethnic Problem?” Asian Survey 32 (98): 723–743. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645365

- Sivarajah, Ambalavanar. 2007. The Federal Party of Sri Lanka. Chennai: Kumaran Book House.

- Spencer, Jonathan. 2007. Anthropology, Politics, and the State: Democracy and Violence in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Spencer, Jonathan, Jonathan Goodhand, Shahul Hasbullah, Bart Klem, Benedikt Korf, and Tudor Silva. 2015. Checkpoint, Temple, Church and Mosque: A Collaborative Ethnography of War and Peace. London: Pluto.

- Suteu, Silvia. 2017. “Eternity Clauses in Post-Conflict and Post-Authoritarian Constitution-Making: Promise and Limits.” Global Constitutionalism 6 (1): 63–100. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045381716000265

- Thiruchelvam, Neelan. 2000. “The Politics of Federalism and Diversity in Sri Lanka.” In In Autonomy and Ethnicity: Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-Ethnic States, edited by Yash Ghai, 197–215. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Uyangoda, Jayadeva, ed. 2023. Democracy and Democratisation in Sri Lanka: Paths, Trends and Imaginations. Vols I and II. Colombo: Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies.

- Waseem, Mohammad. 2012. “Judging Democracy in Pakistan: Conflict Between the Executive and Judiciary.” Contemporary South Asia 20 (1): 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2011.646077

- Welikala, Asanga. 2012. The Sri Lankan Republic at 40: Reflections on Constitutional History, Theory and Practice. Colombo: CPA.

- Welikala, Asanga. 2016. “A New Devolution Settlement for Sri Lanka.” In Proceedings and Outcomes, Conference of Provincial Councils. Colombo: CPA.

- Wickramaratne, Jayampathy. 2014. Towards Democratic Governance in Sri Lanka: A Constitutional Miscellany. Colombo: ICS.

- Wickramasinghe, Nira. 2009. “After the War: A New Patriotism in Sri Lanka?” The Journal of Asian Studies 68 (4): 1045–1054. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911809990738

- Wilson, A. Jeyaratnam. 2000. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Developments in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. London: Hurst.

- Witsoe, Jeffrey. 2013. Democracy Against Development: Lower-Caste Politics and Political Modernity in Postcolonial India. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Wyatt, Andrew. 2013. “Populism and Politics in Contemporary Tamil Nadu.” Contemporary South Asia 21 (4): 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2013.803036