Abstract

In 2011, Sweden introduced explicit standards for the curriculum used in compulsory schooling through the implementation of ‘knowledge requirements’ that align content, abilities and assessment criteria. This article explores and analyses social science teachers’ curriculum agency through a theoretical framework comprised of ‘teacher agency’ and Bernstein’s concepts of ‘pedagogic device’, ‘hierarchical knowledge structure’ and ‘horizontal knowledge structure’. Teachers’ curriculum agency, in recontextualisation of the curriculum, is described and understood through three different ‘spaces’: a collective space, an individual space and an interactive space in the classroom. The curriculum and time are important for the possibilities of agency – the teachers state that the new knowledge requirements compel them to include and assess a lot of content in each ‘curriculum task’. It is possible to identify a recontextualisation process of ‘borrowing’ and combining content from curriculum tasks across the different subjects. This process is explained by the horizontal knowledge structure and ‘weak grammar’ of the social sciences. Abilities, on the other hand, stand out as elements of a hierarchical knowledge structure in which a discursive space is opened for knowledge to transcend contexts and provides opportunities for meaning-making. The space gives teachers room for action and for integrating disciplinary content.

Introduction

This paper explores social science teachers’ curriculum agency in the context of the Swedish curriculum for compulsory schooling (primary and secondary education) from 2011 (Läroplan för grundskolan 2011, henceforth Lgr11).Footnote1 In a national survey of teachers on the impact of Lgr11 on their teaching, the responses of teachers in the social sciences (civics, geography, history and religious studies) stood out because no <76% of them claimed that the new curriculum decided the selection of content in their teaching to a very large extent (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015).

In a study on how Swedish social science teachers experienced the implementation of Lgr11 and its implications for their teaching, Strandler (Citation2017) concludes that teaching has become more oriented towards a reproduction of knowledge in line with what he refers to as the ‘intrinsic dimensions’ of the subjects, and less on their critical examination. To a higher degree, the focus is on gaining knowledge ‘about’ the social science subjects. An outcome-based curriculum forces teachers to reduce the complex and multi-faceted character of their subjects and, to a lesser extent, challenge their students to deliberate on issues concerning democracy, social and ethical values and citizenship – that is, the subjects’ ‘extrinsic dimensions’ (Strandler, Citation2017).

A similarly relevant conclusion for the present study is drawn by Bergh and Wahlström (Citation2017), who explore teachers’ agency in relation to Lgr11 from a transactional realism perspective. They identify a tension between teachers’ acceptance of the new curriculum standards and the practical limitations for their teaching. In brief, the curriculum creates a dilemma for teachers in terms of instituting ‘a practical system for knowledge checks and controls on the one hand and shaping their teaching in terms of transdisciplinary themes emphasising an ideal holistic view and overall understanding on the other’ (Bergh & Wahlström, Citation2017, p. 14).

Compared to the previous curriculum, Lgr11 represents a turn towards explicit curriculum standards in terms of content, procedure and assessment standards, encompassing ‘a combination of a neo-conservative curriculum tradition (the subject tradition) and a technical-instrumental curriculum ideology’ (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012, p. 352). The formation of Swedish curriculum policy discourse is influenced by an international education policy movement towards so-called standards-based curricula (Anderson-Levitt, Citation2008). The salient standardisation features of the curriculum become visible in the ‘knowledge requirements’. The knowledge requirements regulate the relationship and alignment between purpose, content, results, and assessment (National Agency for Education [NAE], 2011b, 2015). However, local contextual conditions have a strong impact on the enactment of a curriculum as a result of recontextualisation processes and local reproductions of pedagogic discourse (Neves & Morais, Citation2010). The culturally embedded school practice and institutional norms change slowly, which implies that curriculum reforms can be assumed to be modified to match the institutional logics of the setting in which they are enacted. Teachers do not passively receive new reforms, but actively respond to and enact policies and curricula (Datnow, Citation2012; Datnow, Hubbard, & Mehan, Citation1998). Teachers’ prior experiences and participation in curriculum innovation processes are important for their pedagogical thinking and how they engage in curricular changes (Salminen & Annevirta, Citation2016).

The purpose of this article is to analyse how teachers seek to achieve agency in curriculum work (Priestley, Biesta, & Robinson, Citation2017). First, this paper examines teachers’ recontextualisation of the curriculum in light of the knowledge requirements as central aspects of the curriculum structure by asking how the process of teachers’ recontextualisation of the curriculum can be described and understood from the perspective of ‘teacher’s curriculum agency’. Second, the article will look into discursive formations of knowledge content (Bernstein, Citation2000) by examining how teachers reorganise the knowledge structure of the content in a standards-based curriculum.

The article consists of four sections. The first part provides a background of the Swedish curriculum, Lgr11. The second part introduces the theoretical and analytical framework, followed by the empirical data and methods used. The third part consists of the findings, and the fourth and final section highlights and discusses the main results and conclusions.

The curricular structure and elements in the Swedish curriculum for compulsory schooling Lgr11

Since the turn of the new millennium, transnational organisations and associations, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union, have played an increasingly important role in the making of educational policy (Robertson & Dale, Citation2015; Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012). In the Swedish case, declining student achievement in international large-scale studies, such as the Programme for International Student Assessment, has made national policy-makers more inclined to be informed by and ‘borrow’ policy solutions from the OECD (Forsberg & Lundahl, Citation2012; Wahlström, Citation2017; Waldow, Citation2012). Recent educational reforms in Sweden are more or less examples of how educational policy has aligned with a transnational policy order that advances the application of different technologies of soft governance in order to make ideas have an impact on different local contexts (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012; Waldow, Citation2012; cf. Alvunger, Citation2015). Examples of this are the establishment of the School Inspectorate in 2010, a government agency tasked with the external auditing and monitoring of schools, and a new Education Act in 2010.

The Swedish curriculum of 2011 took a different direction than the ‘curricular turn’ towards the competence-based and learner-centred curricula that are observed in many other countries around the world (Priestley & Sinnema, Citation2014; Young, Citation2008). Lgr11 has moved towards a curriculum orientation that emphasises academic disciplinary knowledge, that is, a content-driven curriculum. Interdisciplinarity is not prioritised in the curriculum. While teachers are encouraged to work interdisciplinarily, and principals should create the right conditions to expand on knowledge areas such as equality, the environment, sexual education and drug abuse in teaching (NAE, Citation2011a), the subjects are clearly separated according to their specific aims within civics, geography, history and religious studies (Strandler, Citation2017; cf. Adolfsson & Alvunger, Citation2017).

Lgr11 follows a standards-based curriculum trajectory as part of an international education policy movement. This is particularly evident in the ‘knowledge requirements’ that feature in the curriculum. In their analysis of Lgr11, Sundberg and Wahlström (Citation2012) and Wahlström & Sundberg (Citation2015) point out its four key aspects:

Standards: The focus on results, achievement and performance of formulated knowledge content is clearly expressed in Lgr11 … Knowledge requirements are specified and made uniform.

Alignment … The three main parts of Lgr11, Aims, Core Content and Knowledge Requirements, are clearly aligned and the knowledge requirements are also aligned with grading criteria.

Assessment: Through specified levels of requirements, a summative assessment for evaluating and measuring learning outcomes has been made possible and strengthened.

Guidelines … (more detailed guidelines for the assessment of knowledge) (Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012, pp. 351–352).

As described in the quote above, the structure of the subject syllabi in Lgr11 consists of three main elements that are interlinked and prescribed: aims, core content and knowledge requirements. describes these three elements and how the curriculum is structured.

Table 1. The curricular elements of the curriculum for compulsory schooling Lgr11.

The curricular elements of the curriculum for compulsory schooling Lgr11

The curriculum elements assume equal status in terms of regulating what is to be taught and thus they have implications for teacher agency. However, the knowledge requirements are especially important because they specify the abilities that the students are expected to demonstrate. The abilities are transversal and formulated as verbs, spanning basic to advanced abilities, e.g. name, describe, comprehend, apply, analyse, compare and discuss. In the knowledge requirements, the abilities are combined with phrases to express the student’s progression and level of complexity in a subject; for example, to perform an assignment ‘in a nuanced and reflective way’ or ‘in a purposeful and effective way’. The requirements cannot be neglected, because they provide the basis for assessment and grading criteria on a scale from A (top grade) to E. Grades A–E are awarded to a student that has passed, while F grade means that the student has failed to meet the knowledge requirements (NAE, Citation2011a, Citation2015). In the NAE (Citation2011b) guidelines for planning and teaching, teachers are advised to make ‘pedagogical plans’ which contain the knowledge requirements, the core content, aims, the organisation of the teaching activities and the grounds for assessment. In brief, they should provide guidance for students to achieve the goals of the curriculum. A pedagogical plan can cover either a single curriculum task or a number of curriculum tasks (NAE, Citation2011b).

Theoretical and analytical framework

The perspective of teachers’ curriculum agency takes as its starting point Doyle’s (Citation1992) line of argument that the teacher authors ‘curriculum events’ in the transformation of curriculum text content into actual teaching content in the classroom to develop students’ knowledge and abilities. In the interactional space of the classroom, students act as ‘co-authors’. In this respect, the curriculum is seen as ‘text’ (Doyle, Citation1992), and this analysis will reveal how teachers enact the different curriculum elements in their teaching practice through a conceptualisation and understanding of ‘teacher agency’ that involves the interaction between individual capacities and environmental conditions (Priestley, Edwards, Priestley, & Miller, Citation2012; Priestley et al., Citation2017).

In order to link teachers’ curriculum agency to curriculum structure and content, this paper analyses how different discourses of meaning are produced and reproduced in pedagogic ‘discourse’ from Bernstein’s (Citation2000) analytical concepts of ‘pedagogic device’, ‘hierarchical knowledge structures’ and ‘horizontal knowledge structures’. By combining the concept of teacher agency and the notion of recontextualisation processes in the production and reproduction of pedagogic discourse, the aim is to create space for new ways of interpreting and understanding teachers’ curriculum agency.

Teachers’ curriculum agency

Over the past decade, there has been extensive research carried out in the field of agency, particularly with regard to how agency is conceptualised within teachers’ work and practice. Studies emphasise the relational aspects of agency (Edwards, Citation2005), teacher agency within the context of educational reform and change (Datnow, Citation2012; Priestley, Citation2010; Pyhältö, Pietarinen, & Soini, Citation2014) or theorise on agency from a macro-perspective, such as through the lens of educational systems in a globalising world (Vongalis-Macrow, Citation2007).

In this study, the analysis of the teachers’ views on how the curriculum is implemented in practice is inspired by Priestley et al.’s (Citation2017) ‘ecological approach’ to teacher agency. Their notion of agency takes into account the interaction between individual capacities and conditions in the environment. In this respect, agency is something that is ‘achieved’ (Priestley et al., Citation2017), rather than being an individually embedded quality. Drawing on the seminal work of Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998), Priestley et al. (Citation2017) develop their theoretical framework using three temporal dimensions of agency: iterational, practical-evaluative and projective (cf. Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998). The iterational dimension concerns how teachers make use of their past – that is, their life experiences in terms of their personal and professional histories – while the projective dimension consists of expectations for the future, both in the short term and in the long run. While these two dimensions are important elements of the concept of agency, this study focuses on the practical-evaluative dimension. This dimension concerns cultural (ideas, values and discourses), structural (social relations, trust and power) and material (environment and resources) aspects (Priestley et al., Citation2012, Citation2017; cf. Bergh & Wahlström, Citation2017). How teachers experience these aspects of agency is essential for describing and understanding their recontextualisation of the curriculum in their teaching activities. The following quote by Priestley et al. (Citation2017) serves as a point of departure for how teacher curriculum agency is perceived and conceptualised for the analysis of the empirical findings in this study:

The main distinctive factor is that agency involves intentionality, the capacity to formulate possibilities for action, active consideration of such possibilities and the exercise of choice. But it also includes the causative properties of contextual factors – social and material structures and cultural forms that influence human behaviour – which is why, as mentioned, a full understanding of agency must consider how individual capacity interplays with contextual factors (Priestley et al., Citation2017, p. 23).

The analytical implication of this conceptualisation of teacher agency is that it includes teachers as agents in the recontextualisation of the curriculum and affects how teachers value their possibilities and room for action in relation to material and social factors. Finally, it involves intentions and teachers’ deliberations and considerations, which becomes particularly important in the light of how teachers experience the reorganisation of the content in a standards-based curriculum.

The pedagogic device, hierarchical knowledge structures and horizontal knowledge structures

How can the concept of teachers’ curriculum agency be linked to the production, reproduction and transformation of discourses and meanings? For Bernstein (Citation2000), these processes occur within what he refers to as interlinked rules of recontextualisation within the ‘pedagogic device’. The distributive rules shape the social and moral order, that is, who has the power to decide what counts as knowledge. In turn, these rules influence the recontextualising rules, which consist of regulative discourse and instructional discourse as inseparable elements in pedagogic discourse. While regulative discourse has to do with the justification of values, the instructional discourse concerns the knowledge and skills that are to be produced and reproduced in pedagogic discourse (Alvunger & Wahlström, Citation2017; Haavelsrud, Citation2010). Finally, the evaluative rules decide what principal elements are to be assessed in pedagogic practice (Bernstein, Citation2000).

Bernstein (Citation2000) distinguishes between two knowledge discourses in which different forms of knowledge are realised: horizontal discourse, with its common and context-bound knowledge (e.g. welcoming guests or using a microwave oven), and vertical discourse, which is theoretical, general, abstract, context-independent and can be integrated into and give potential meaning to different systems and contexts (Bernstein, Citation2000; Maton, Citation2009; cf. Singh, Citation2002). Within vertical discourse, Bernstein (Citation2000) distinguishes between a hierarchical knowledge structure as ‘a coherent, explicit and systematically principled structure’ (p. 160) that seeks to integrate propositions, concepts and theories from lower levels, and a horizontal knowledge structure as ‘a series of specialised languages with specialised modes of interrogation and criteria for the circulation of texts’ (p. 161).

According to Bernstein (Citation2000), the ‘language’ of natural sciences is characterised by its ‘strong grammar’, meaning that it has ‘an explicit conceptual syntax capable of relatively precise empirical descriptions and/or of generating formal modelling of empirical relations’ (p. 163, ital. in original). The disciplines that fall within the humanities and social sciences are examples of horizontal knowledge structures with ‘weak grammar’, that is, competing ‘languages’ representing, for example, different influential schools of thought, perspectives and thinkers (Bernstein, Citation2000; Martin & Maton, Citation2017; Maton & Doran, Citation2017). This weak grammar suggests that the boundaries between the disciplines in social sciences become blurred in the recontextualisation of pedagogic discourse.

The theoretical distinction between a hierarchical knowledge structure and a horizontal knowledge structure, together with the concepts of strong grammar and weak grammar (Bernstein, Citation2000; Maton, Citation2009; Singh, Citation2002), open up for analysis the organisation of the content and structure of the curriculum in teaching. Maton (Citation2009) argues that they can be applied to a ‘unit of study’ in the form of a lesson, module or year in order to distinguish whether knowledge from previous units is integrated and organised in the subsequent unit (cumulative), or segmented and aggregated in a series of fields and topics. In the former case, knowledge ‘transcends’ contexts and creates different forms of meaning, while in the latter, knowledge is segmented, embedded and context-dependent (Maton, Citation2009). In the present study, these perspectives will be applied to analyse discursive formations of knowledge content in curriculum tasks. The pedagogic device provides an overarching framework for conceptualising the contextual factors of teachers’ descriptions of how the curriculum plays out in practice, together with examples of interaction in classroom settings.

Empirical data and methodology

The empirical data used in the present study build on four cases whose material was collected over an entire school year in four year-six classrooms (12/13-year olds). The schools were located in both urban and rural districts. On the basis of the results of a large national survey, social science teachers were selected for this study because they claimed that the curriculum, to a large extent, dictates the selection of their teaching content (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015, Citation2017). The data collection was carried out in the following manner (Sundberg, Citation2017):

Classroom observations were conducted through video recordings of 48 lessons to examine curriculum configurations in classroom discourse. Lessons at the beginning, middle and end of the curriculum tasks were selected to get as wide a sample as possible. Each lesson lasted for about an hour.

Curriculum documents, such as the teaching materials used by the teachers, were collected. The main documents in this respect were the teachers’ pedagogical plans and worksheets.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with four social science teachers (after their lessons) regarding curriculum elements, selection of content, contextual factors and their teaching on different occasions over the course of the school year (16 interviews in total).

Through a combination of methods, complementary types of data could be sampled (Creswell, Citation2010; Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2007), providing a rich material for the analysis of how teachers seek to achieve agency and the production of pedagogic discourse.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of good research practice by the Swedish Research Council. The participating teachers and students were informed about the purpose of the study, that they could withdraw from participating at any time and that the empirical data were treated confidentially (Swedish Research Council (SRC), Citation2017). The data collection for the project ‘Understanding Curriculum Reforms – a Theory-Oriented Evaluation of the Swedish Curriculum Reform Lgr11’ was subjected to ethical review by a board for ethical vetting. As the teaching was videotaped, the parents of the students and the students had to give their approval and consent to participate through written permission (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2017).

Analysis of the data

The analysis of the empirical data is based on a qualitative content analysis approach (Bryman, Citation2012). As a first step, the video-recorded lessons were transcribed, coded and analysed in protocols through a framework focusing on teaching repertoires, content and interaction in the classroom. The teaching was categorised according to whole-class teaching with the teacher as the central actor, whole-class teaching with the student as the central actor, teacher instructions, group (project or theme) work and individual work in the classroom (Adolfsson, Citation2018; Sundberg, Citation2017). In the second step, teaching sequences with whole-class teaching (with the teacher as the central actor and with the students as the central actor) from the primary coding of teaching repertoires were selected and analysed from the following coding scheme based on the theoretical framework of the study.

Coding scheme for qualitative data analysis

During coding, each code was exemplified with a brief characterisation of the lesson content. Because of the actual content of a teaching sequence, codes could overlap, that is, the content could be categorised as oriented both towards specific aspects/questions and towards cross-curricular and interdisciplinary knowledge. The curriculum documents were analysed from the same codes. Altogether, the coding led to the analysis of the organisation of the knowledge content in terms of hierarchical or horizontal knowledge structures and strong or weak grammar. The teacher interviews were analysed from categories that yielded insight into how the content of the curriculum was organised by the teachers in terms of knowledge structures, the organisation and performance of the lessons, and how the teachers perceived their individual capacities and contextual factors for agency within classroom discourse ().

Table 2. Coding scheme for qualitative data analysis.

Spaces for teachers’ curriculum agency in the recontextualisation of the curriculum

Lgr11’s introduction of curriculum standards has had an impact on how teachers experience their agency. The teachers specifically emphasise the practical implications of the knowledge requirements as central aspects of the curriculum structure, for example: ‘I thoroughly go through what parts of the knowledge requirements I must assess the students on. Based on what I have to assess them on, I check the core content’ (Teacher 3).

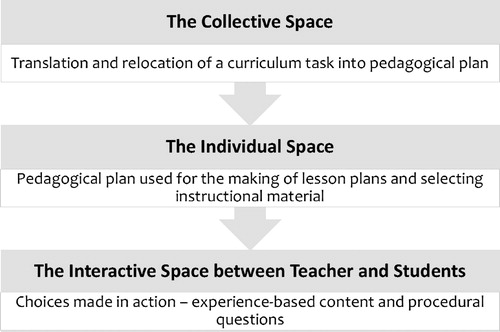

The teachers experience a surplus of content and face time constraints, because each subject contains many curriculum tasks. In other words, contextual factors impede their agency. However, in the interviews they give examples of strategies for dealing with these hurdles. Based on their statements, it is possible to empirically identify three different spaces of curriculum recontextualisation: a collective space where teachers seek room for action through collaboration; an individual space of lesson planning by the teacher; and an interactive space in the classroom between the teacher and students (cf. Adolfsson & Alvunger, Citation2017). captures the essential aspects of the process and spaces.

During the interviews, the teachers constantly return to the need to consult with their colleagues, which indicates that social and collective dimensions form a significant foundation of collegial discourse. The teachers describe how together they create an outline of the semester and/or the whole school year, and place the subjects and different curriculum tasks within timeframes (weeks), or as explained by a teacher: ‘Then you get that overview so you really have the time to sit and check what fits into what and what I could place in there’ (Teacher 2).

The collective space does not only create opportunities for dealing with the pressure caused by time constraints and a heavy curriculum, it is also used to discuss knowledge requirements and core content: ‘We have made interpretations of the central core content in the teacher team and then we have shared it with the other school where we have picked out the most important’ (Teacher 2). In this respect, the pedagogical plans are emphasised as important for making meaning out of the curricular elements and the foundations for teaching and assessment:

We sit down and work with pedagogical plans and matrices and that stuff … that is our main task now during the spring. Based on that the idea is that we actually will look into what we do, when we make a pedagogical plan and to check, what does it mean when we work from these goals or knowledge requirements? What do we have to add? (Teacher 4)

The work with pedagogical plans thus becomes a collaborative strategy for teachers that offers them possibilities for agency in terms of interpreting the knowledge requirements. It also provides a ‘template’ for the teachers. Even if the subjects in the Lgr11 are clearly distinct, the teachers in the study combine content from different curriculum tasks and thus organise segments of knowledge in a horizontal knowledge structure in order to achieve agency (this will be discussed in greater detail in the next section).

Below is an excerpt from a pedagogical plan that serves as an example of how teachers include and combine content from three different subjects: civics, geography and Swedish:

Society’s need for legislation, some different laws and sanctions, and criminality and its consequences for the individual, the family and society.

Private economy and the relationship between work, income and consumption.

The public economy. What are taxes and what do municipalities, county councils and the state use tax revenue for?

Economic conditions for children in Sweden and in different parts of the world. Some causes and consequences of prosperity and poverty.

Present arguments in different conversational situations and decision-making processes.

How choices and priorities in everyday life can influence the environment and contribute to sustainable development. (Excerpt 1)

The structuring of knowledge requirements and content in the pedagogical plan is important for each individual teacher when they plan their lessons and assignments and select instructional material. This is the ‘individual space’. The teachers claim that the knowledge requirements significantly shape the organisation of their teaching: ‘I take the “back-door”, so to say. First, I look at the knowledge requirements and then I relate it to the aim’ (Teacher 4). An essential element of why the knowledge requirements are so important is because the abilities – meaning abilities to analyse, critically assess sources, argue and express opinions, interpret and reflect and communicate – largely define the borders of the teachers’ scope for action and curriculum agency with regard to their instructional discourse and activities in the classroom:

It is all these abilities that you have to work with. That you try to make a plan from start to end in each curriculum task, where you try to cover as many [abilities] as possible. And even when I ask the students how they would like to work, we usually do it when we are going through the pedagogical plan, you know. What are we supposed to learn and what can we do to learn that? (Teacher 3)

In the quote above, the teacher says that the students are involved in discussions on ‘how’ to work, but not ‘what’ to work with. The ‘what’ is already decided in both the ‘collective space’ and the ‘individual space’, but there is still room to discuss procedural questions.

Teachers rarely refer to student influence on matters of content in teaching, but it is possible to identify an ‘interactive space’ in the interplay between teacher and students in the classroom. An overall impression gained from the classroom analyses is that the teachers are careful not to let situations get out of hand, and sometimes simply neglect to answer questions and comments from the students. However, there are sequences in which teachers give way for the students’ experiences. In this respect, teachers exploit the possibilities for agency in classroom discourse provided by certain subject content that can easily be related to everyday experiences and context-bound knowledge.

The excerpt below is a short sample taken from an exchange that lasted for about 40 min during a civics lesson. It illustrates how the teacher makes use of the students’ experiences while going through the textbook content and central concepts related to ‘private economy’. During the exchange, the teacher reads aloud from the textbook. Sometimes the teacher stops to check what the students already know or to allow the students to make comments and ask questions. At times, comments from the students are ignored in order to move on with the lesson. The exchange quoted took place after the students had discussed the concept of a ‘budget’ in small groups and in a brief whole-class discussion. While reading aloud from the textbook about the concepts of savings and loans, mortgages and interest, child allowance and student loans, the students at times ask questions about unexpected expenses, what happens if you cannot pay your debts, how you calculate the interest on a loan and so on. When the teacher talks about the importance of taking out insurance in case your house catches fire, your car gets stolen or there is a break-in, a student raises his hand:

Teacher: Yes, Marcus?

Marcus: Have you ever had, you know, a break-in?

Teacher: No, I have never had a break-in, neither in my car, nor my house. I have never experienced anything like that. Adam?

Adam: Once when we were in Stockholm and were about to walk to our car, there was a stolen car, with a lot of broken glass.

Teacher: I know that cars nearby mine have been stolen, but not mine. It is unpleasant. (The teacher nods to a student with a raised hand, permitting him to speak.)

William: My granny, there had been a break-in at her place and someone had broken the side window of her car and taken her purse.

Teacher: That’s really sad. In there you keep a lot of what you value. It is scary to know someone has been in your house. My granny had some men come to her house who played nice and asked for help. While she was talking to one of them, the others went in and took all her old rings, jewellery and valuables. Alice?

Alice: Once there was a break-in at my grandma’s and grandpa’s place and they stole a lot of jewellery and stuff. And there was a piece of jewellery my grandma really loved and the police said that they never would get it back, but they did.

Teacher: Oh, that was a blessing in disguise for her! That is unusual. Many times, it is hard to get back the stolen goods because the thieves quickly get rid of it, melt down the gold or sell it. Robert?

Robert: Does all insurance cost the same?

Teacher: No, it doesn’t. And you can often get better terms if you have multiple policies with the same insurance company. And it depends, if you have many cars or a big house, that determines how much you pay.

Joseph: Once when my dad was working, they skimmed his company card.

Teacher: Can you explain what ‘skimmed’ means?

Joseph: It means that they have put something in the ATM.

Teacher: Which reads?

Joseph: It reads the code. It can be at gas stations as well.

Adam: Is that really possible?

Teacher: What happened?

Joseph: They bought a lot of things abroad. For a lot of money. (Excerpt 2)

The exchange above provides good insight into the interactive space for teachers’ agency in classroom discourse, where the teacher makes use of the students’ experiences that align with the presentation of central concepts. The teacher also lets the students explain and teach new concepts to their peers (as in the example of the ‘skimmed’ card). In this interactive space, teachers can use knowledge from horizontal discourse (experiences of crime and experiences of family members) and insert it into the subject’s horizontal knowledge structure comprised of subject-specific concepts.

Knowledge structures in the organisation of teaching

The knowledge requirements are an essential part of the curriculum structure. Even if there are clear distinctions between the subjects, the previous analysis of teachers’ curriculum agency has shown that teachers organise and combine content from different curriculum tasks. The teachers employ strategies and try to create ways and innovations that will help them to deal with the content burdens and time constraints. In this section, the focus will be directed towards how this kind of ‘borrowing’ and recontextualisation of the curriculum can be understood from the perspective of knowledge structures.

In Excerpt 1 – presented in the previous section – there was an example of a pedagogical plan covering curriculum tasks from civics, geography and Swedish. The teachers experience Lgr11 as being explicit in terms of prescribed content, and they struggle to find time to assess the students on the knowledge requirements. Meanwhile, it becomes clear that the teachers make use of the content in the curriculum tasks of different subjects and relate them to one another, meaning that they work implicitly interdisciplinarily. The social sciences present good opportunities for this; as one of the teachers describes:

Well, there are so many subjects that you can connect … you can watch different movies that address both democracy and history, for instance. That’s how it is with civics too. It is easier to link, when you talk about civics, you can talk about world news … And then civics also is connected to Swedish. And in geographic terms you bring in the different places you talk about—where in the world is it happening? (Teacher 2)

As suggested in the quote, the similarity in the content of social science subjects enables linkages to be made within the frames of a certain context or topic. What students have previously learnt in a certain subject may be contextualised by referring to an earlier set of knowledge content with a similar terminology and conceptual frame. A particular area of knowledge embedded in a curriculum task is inserted and added in a new context. In this respect, there is a production and reproduction of knowledge in pedagogic discourse, where the placing of content in a series of interlinked curriculum tasks in different subjects can be seen as a segmentation of themes in a horizontal knowledge structure. Various contents are presented through contextual linkages, rather than through an overarching and abstract theoretical system. This segmentation and association can be explained by the weak grammar of the social sciences.

However, the combination and ‘borrowing’ of content from different subjects’ curriculum tasks cannot only be understood through the weak grammar of the social sciences. There is an element in the curriculum that functions as a general structure with the potential to create meaning that helps to integrate content from the different curriculum tasks: the abilities within the knowledge requirements. Thanks to their transversal character, the abilities are central elements, but they also stand out as what can be regarded as valuable and worthwhile knowledge in the pedagogic discourse. The excerpt below comes from a pedagogical plan regarding the curriculum task ‘world religions’ in religious studies. The content is not necessarily in the foreground; rather, the focus is on the abilities in the knowledge requirements in terms of the production and reproduction of knowledge:

We will work with world religions because you should develop your ability to:

Religious studies

Analyse different religions and conceptions of life, as well as different orientations and customs within these.

Analyse how religions affect and are influenced by conditions and courses of events in society.

Reflect on life issues and one’s own identity, as well as those of others.

Seek information about religions and spiritual views and evaluate the relevance and credibility of the sources.

Swedish

Express yourself orally and in writing.

Read and analyse texts for different purposes.

Adapt the language for different purposes, recipients and contexts.

Seek information from different sources and evaluate these. (Excerpt 3)

Based on the introductory sentence, the area of study is justified through the need for students to acquire certain abilities. These abilities – as part of the knowledge requirements – represent a hierarchical knowledge structure in the curriculum, spanning basic to more advanced levels. They provide opportunities to engage in reasoning, critical thinking and theorising, that is, context-independent qualities with the potential to bring meaning to different contexts. Thus, they may help teachers to integrate knowledge from different curriculum tasks. In the following example from a civics lesson concerning the curriculum task ‘work and economy’, it is possible to see how the abilities and core content are enacted in teaching. In this case, the teacher stands in front of the class and ‘checks’ what the students know about the ability to argue:

Teacher: There’s something you need to learn. I told you that you will work with argumentation and argue the topic ‘weekly allowance’. First, I have to ask you: What is an argument? (A number of the students raise their hands.) Jennie?

Jennie: When you discuss things, you need like one who is in favour of something and another one, who is against something.

Teacher: Then you have an argument, yes. What were you planning to say, Henry?

Henry: Yeah, like the same thing. You discuss what you think about different things.

Teacher: You can say that you have something referred to as (teacher turns around and writes on the whiteboard) an ‘emotional argument’. What is that? Can anyone guess what it is? (A student raises her hand and the teacher nods to allow an answer.)

Lisa: If someone starts to cry or something, then you feel sorry for them. Then you might start to agree with them?

Teacher: Yes, it could be that, or if you explain to someone, like: (teacher emulates the tone of an actual conversation) ‘when you do that, it makes me feel really sad. I become disappointed and feel that we cannot go on like this, because I can’t take it anymore’.

(The teacher turns to the whiteboard again and writes a new word. The students start talking amongst themselves.)

Teacher: Then there is something called a ‘factual argument’, and a factual argument, shhhh … (the teacher hushes the students) could simply be when you say to your parents: ‘Now here’s the thing that I have checked. In my class, everyone gets at least 25 Swedish crowns as a weekly allowance and I only get 20. And I know that there are those who get 50 for their weekly allowance. Do you think it’s fair that I only get 20?’ (Excerpt 4)

This passage shows that the teacher wants to make students aware of the importance of demonstrating an ability. In this excerpt, the ability to make an argument is framed within a task in civics, but this specific ability, as well as other abilities expressed in the knowledge requirements, corresponds directly to abilities required in the subject of Swedish, for example.

The nature of the abilities is that they apply to all subjects, and they create space for integrating various kinds of content through their pivotal position. In this respect, the hierarchical structure of the abilities can be linked to horizontal segmentation through the weak grammar of social science subjects. This relationship is discernible in the following quote from one of the teachers:

If you look at what you are supposed to do from the abilities and what it’s about, that you are to be able to analyse and reflect and so forth on various aspects, then you can try to link it together. Then you check the core content and what parts must be included and many times you can weave it together. (Teacher 2)

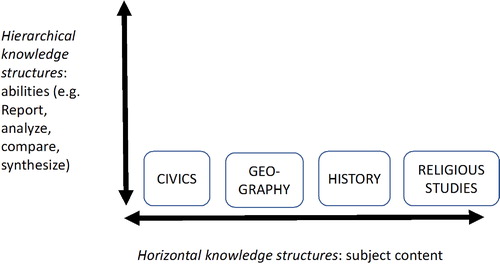

In a process whereby teachers employ a strategy of ‘borrowing’ content from the curriculum tasks of other subjects, an essential dimension that opens up for integrating knowledge content is found in the abilities. Because of their context-independent character, abilities help to ‘bridge’ content between the subjects, which is illustrated in .

Figure 2. Hierarchical and horizontal knowledge structures for organising and combining subject content.

As a hierarchical curriculum structure, the abilities make it possible to transcend the disciplinary boundaries of the different curriculum tasks in the school subjects. Considering the weak grammar of the social sciences, by using the abilities as mediators, content embedded within the same context can be linked and transferred within the languages of civics, history, geography and religious studies.

Teachers’ curriculum agency: Coping with different types of spaces and knowledge structures

In this article, the aim has been to explore social science teachers’ curriculum agency in light of Lgr11 – Sweden’s curriculum for compulsory schooling. In line with previous studies on how social science teachers have perceived the implementation of Lgr11 (Bergh & Wahlström, Citation2017; Strandler, Citation2017), the present study shows that the emphasis on assessing students’ results and the knowledge objectives stated in the knowledge requirements have implications for teachers’ ability to manoeuvre. The teachers in this study claim that there are content burdens and time constraints caused by the fact that each subject contains many ‘curriculum tasks’. With the focus on knowledge requirements and content, in terms of subject-specific concepts, there is a clear shift towards what Strandler (Citation2017) labels the ‘intrinsic dimensions’ of social science subjects. The teachers are faced with dilemmas regarding educational goals that emphasise the standardisation of teaching content and assessment in order to achieve ‘equity’, and their personal ideals and visions of teaching to promote the principles and values of a democratic citizen (Bergh & Wahlström, Citation2017).

Bergh and Wahlström (Citation2017) argue that Lgr11 has meant that teachers must ‘adapt their teaching to the requirements stated in the curriculum (the practical-evaluative experience), and that they need to reflect on some of their earlier assumptions of good teaching and adapt to a partly new discourse on teaching ideals’ (p. 13). This statement also applies to this study; however, the analysis adds new perspectives on teachers’ curriculum agency in terms of how they grapple with the question of translating and recontextualising the knowledge requirements and core content in the curriculum in their teaching. In this process, working with pedagogical plans is an expression of how teachers engage in a recontextualisation process and locally reproduce pedagogic discourse (cf. Neves & Morais, Citation2010).

Collective, individual and interactive spaces

This study has identified the existence of a ‘collective space’ as an important element of curriculum work – that is, framing the curriculum in relation to the institutional logics of the local school. Teachers deal collectively with the knowledge requirements and the curriculum tasks through the construction of pedagogical plans that seek to align aims, content and assessment criteria. The collective space corresponds to the cultural and structural aspects of teacher agency (Priestley et al., Citation2012, Citation2017). Even though the Lgr11 curriculum makes a clear distinction between social science subjects, teachers seek to achieve agency by combining content from different curriculum tasks across subjects. Their intention is to link content from different curriculum tasks by bringing together the knowledge requirements. Thus, the creation of pedagogical plans offers opportunities for teachers to cope with contextual factors and gives them room to act in what has also been referred to as the ‘individual space’, with the pedagogical plan playing a pivotal role in the teacher’s ability to construct assignments and plan lessons.

Hierarchical and horizontal knowledge structures

The strategy of ‘borrowing’ and combining content in different curriculum tasks as a means of achieving curriculum agency is further explained through the analysis of hierarchical and horizontal knowledge structures (Bernstein, Citation2000; Maton, Citation2009). In the pedagogical plans, it is possible to organise segments of knowledge in a horizontal knowledge structure. The disciplinary borders of the school subjects are expressed in the knowledge requirements and the core content as ‘a series of specialised languages’ in a horizontal knowledge structure (Bernstein, Citation2000, p. 161). Since the social sciences are characterised by weak grammar and a pluralism of ‘languages’ (Martin & Maton, Citation2017; Maton & Doran, Citation2017), the boundaries between the subjects are vague. Thus, the open character of the subjects provides scope for action. In what is referred to as the ‘interactive space’, examples from exchanges in the classroom illustrate how teachers build on the students’ everyday experiences in classroom discourse (horizontal discourse) and connect it to concepts and phenomena in the subjects’ horizontal knowledge structures.

Finally, the analysis of knowledge structures reveals that as a transversal and integrated dimension of the knowledge requirements, the abilities can be seen as a hierarchical knowledge structure in the curriculum. Here, it seems that the abilities communicate with the ‘extrinsic dimensions’ of the social studies subjects (Strandler, Citation2017). The abilities constitute a hierarchically organised structure of pedagogic discourse (Bernstein, Citation2000; Maton, Citation2009; Singh, Citation2002) and create possibilities for transcending contexts. This becomes clear in both the pedagogical plans and in the manner in which teachers describe how they begin with the knowledge requirements and particularly focus on the abilities. By ‘patching’ content from different curriculum tasks together in a horizontal knowledge structure and linking abilities as a hierarchical knowledge structure between the school subjects, teachers seek synergies for assessing their students’ abilities.

The weak grammar of the social sciences, in combination with the hierarchical structure of the abilities, opens up a discursive space where knowledge can transcend different contexts. It allows for a reorganisation of content and harbours the potential for the creation of new meanings in classroom discourse. This discursive space gives teachers the room they need to take action and to integrate content in terms of using disciplinary concepts from different subjects, for example. Due to the abstract, general and hierarchical character of the abilities, it is possible to link separate segments of curriculum tasks to each other in a horizontal knowledge structure. Even if the disciplinary boundaries between the subjects are emphasised in the Swedish Lgr11 curriculum, and there are content and time constraints from the perspective of the teachers, the curriculum agency that social science teachers express nevertheless seems to be paving the way for an interdisciplinary dimension to take hold in their teaching.

Note

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Alvunger

Daniel Alvunger is a senior lecturer in education and a member of the research group, Studies in Curriculum, Teaching and Evaluation (SITE), at Linnaeus University, Sweden. His research concerns curriculum theory with a focus on the intertwined relationships between transnational policy, national educational reforms and their implications in local schools.

Notes

1 This article theoretically deepens and develops parts of the empirical results from a Swedish project funded by the Swedish Research Council (2014–2016): ‘Understanding Curriculum Reforms – a Theory-Oriented Evaluation of the Swedish Curriculum Reform Lgr11’. The results are included in a book chapter written by Adolfsson and Alvunger Ref Adolfsson, C.-H., & Alvunger, D. (2017). The selection of content and knowledge conceptions in the teaching of curriculum standards in compulsory schooling. In N. Wahlström & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching (pp. 98–115). New York, NY: Routledge."2017, pp. 48–65).

References

- Adolfsson, C.-H. (2018). Upgraded curriculum? An analysis of knowledge boundaries in teaching under the Swedish subject-based curriculum. The Curriculum Journal, 1–17. doi:10.1080/09585176.2018.1442231

- Adolfsson, C.-H., & Alvunger, D. (2017). The selection of content and knowledge conceptions in the teaching of curriculum standards in compulsory schooling. In N. Wahlström & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching (pp. 98–115). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Alvunger, D. (2015). Towards new forms of educational leadership? The local implementation of förstelärare in Swedish schools. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1(3), 55–66.

- Alvunger, D., & Wahlström, N. (2017). Research-based teacher education? Exploring the meaning potentials of Swedish teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 24(4), 332–349. doi:10.1080/13540602.2017.1403315

- Anderson-Levitt, K.M. (2008). Globalization and curriculum. In: M.F. Connelly (Ed.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 349–368). London: Sage Publications.

- Bergh, A., & Wahlstro¨m, N. (2017). Conflicting goals of educational action: A study of teacher agency from a transactional realism perspective. The Curriculum Journal, 29(1), 134–149. doi:10.1080/09585176.2017.1400449

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Creswell, J.W. (2010). Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 45–68). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J.W., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods. London: Sage Publications.

- Datnow, A. (2012). Teacher agency in educational reform: Lessons from social networks research. American Journal of Education, 119(1), 193–201.

- Datnow, A., Hubbard, L., & Mehan, H. (1998). Educational reform implementation: A co-constructed process (research report 5). Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence.

- Doyle, W. (1992). Curriculum and pedagogy. In P.W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 486–516). New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 168–182.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103, 962–1023.

- Forsberg, E., & Lundahl, C. (2012). Re/produktionen av kunskap i det svenska utbildningssystemet [Re/production of knowledge in the Swedish education system]. In T. Englund, E. Forsberg, & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Vad räknas som kunskap? Läroplansteoretiska utsikter och inblickar i lärarutbildning och skola [What counts as knowledge? Curriculum theory perspectives on teacher education and school] (pp. 200–224). Stockholm: Liber.

- Haavelsrud, M. (2010). Classification strength and power relations. In A. Morais, I. Neves, B. Davies, & H. Daniels (Eds.), Towards a sociology of pedagogy: The contribution of Basil Bernstein to research (pp. 319–337). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Martin, J.R., & Maton, K. (2017). Systemic functional linguistics and legitimation code theory on education: Rethinking field and knowledge structure. ONOMAZEIN Numero especial SFL y TCL sobre educación y conocimiento, 1, 12–45. Retrieved from http://onomazein.letras.uc.cl/03_Numeros/Nespecial-SFL/N-SFLe.html

- Maton, K. (2009). Cumulative and segmented learning: Exploring the role of curriculum structures in knowledge-building. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30(1), 43–57. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40375403

- Maton, K., & Doran, Y.J. (2017). Semantic density: A translation device for revealing complexity of knowledge practices in discourse, part 1 – Wording. ONOMAZEIN Numero especial SFL y TCL sobre educación y conocimiento, 1, 46–76. Retrieved from http://onomazein.letras.uc.cl/03_Numeros/Nespecial-SFL/N-SFLe.html

- National Agency for Education (NAE). (2011a). Läroplan för grundskola, förskola och fritidshemmet [Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the leisure-time centre] Lgr11. Stockholm: The National Agency for Education.

- National Agency for Education (NAE). (2011b). Allmänna råd för planering och genomförande av undervisningen [General guidelines for planning and performing teaching]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- National Agency for Education (NAE). (2015). Kommentarsmaterial till kursplanen isvenska [Commentary material for the syllabus in Swedish]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Neves, I., & Morais, A. (2010). Texts and contexts in educational systems: Studies of recontextualisation spaces. In A. Morais, I. Neves, B. Davies, & H. Daniels (Eds.), Towards a sociology of pedagogy: The contribution of Basil Bernstein to research (pp. 223–249). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Priestley, M. (2010). Schools, teachers and curriculum change: A balancing act? Journal of Educational Change, 12(1), 1–23.

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2017). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Priestley, M., Edwards, R., Priestley, A., & Miller, K. (2012). Teacher agency in curriculum making: Agents of change and spaces for manoeuvre. Curriculum Inquiry, 42(2), 191–214.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2014). Comprehensive school teachers’ professional agency in large-scale educational change. Journal of Educational Change, 15(3), 303–325.

- Priestley, M., & Sinnema, C. (2014). Down-graded curriculum? An analysis of knowledge in new curricula in Scotland and New Zealand. Curriculum Journal, 25(1), 50–75.

- Robertson, S., & Dale, R. (2015). Towards a ‘critical cultural political economy’ account of the globalising of education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 13(1), 149–170.

- Salminen, J., & Annevirta, T. (2016). Curriculum and teachers’ pedagogical thinking when planning for teaching. European Journal of Curriculum Studies, 3(1), 387–406.

- Singh, P. (2002). Pedagogising knowledge: Bernstein’s theory of the pedagogic device. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(4), 571–582.

- Strandler, O. (2017). Constraints and meaning-making: Dealing with the multifacetedness of social studies in audited teaching practices. Journal of Social Science Education, 16(1), 56–67.

- Sundberg, D. (2017). Mapping and tracing transnational curricula in classrooms – The mixed-methods approach. In N. Wahlström & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching (pp. 48–65). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sundberg, D., & Wahlström, N. (2012). Standards-based curricula in a denationalized conception of education: The case of Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 11(3), 342–356.

- Swedish Research Council (SRC). (2017). Good research practice. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council.

- Vongalis-Macrow, A. (2007). I, teacher: Re‐territorialization of teachers’ multi‐faceted agency in globalized education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(4), 425–439.

- Wahlström, N. (2017). The travelling reform agenda: The Swedish case through the lens of OECD. In N. Wahlström, & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching (pp. 15–30). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2015). A theory-based evaluation of the curriculum Lgr11 (working paper no. 2015:11). Uppsala: IFAU – Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy.

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2017). Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Waldow, F. (2012). Standardisation and legitimacy: Two central concepts in research on educational borrowing and lending. In G. Steiner-Khamsi & F. Waldow (Eds.), World year book of education 2012: Policy borrowing and lending (pp. 411–427). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Young, M. (2008). From constructivism to realism in the sociology of the curriculum. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 1–28.