Since the 1990s, there have been hundreds of conceptual and empirical articles investigating the relationship between Strategic Human Resource Management (SHRM) and performance. To this end, scholars have studied the role of the HR function, ‘fit’ between SHRM, and a range of contextual factors which include the external environment (market and institutions), internal structures and processes, and an organization’s administrative heritage. Empirical evidence convincingly demonstrates the added value of SHRM for organizational performance in terms of increased productivity, higher profitability, and lower employee turnover rates (Arthur, Citation1994; Combs, Liu, Hall, & Ketchen, Citation2006; Van De Voorde, Paauwe, & Van Veldhoven, Citation2010). However, almost without exception, SHRM research has relied on evidence from private sector organizations. Therefore, the aim of this special issue is to address this imbalance by considering SHRM in a public sector context (see Ongaro & Van Thiel, Citation2017).

In many countries, public sector organizations tend to be the largest employer. Public sector employment is typically characterized as being labor intensive, as the performance of public sector workers is critical to the delivery of services. The services offered by public organizations affect a person’s life from birth (hospital care), through childhood and teenage years (schooling), throughout adult life (refuse collection, transportation, highways, social housing, parks, and open spaces), old age (elderly care), and eventually death. To a very large extent, the quality of the welfare state and the health and well-being of the nation depends on the performance of public sector employees. However, in many countries, public organizations are experiencing cut-backs in resources and increasing demands to demonstrate accountability and improve service quality to meet the expectations of service users. All these developments make the study of HRM and public sector performance a highly relevant theme. Encouragingly, initial findings based on public sector research suggest that strategic HRM has positive effects on employee motivation and organizational performance (Messersmith, Patel, Lepak, & Gould-Williams, Citation2011). It is our intention to supplement theses initial findings by providing an outlet for papers studying HRM, employees’ attitudes and behaviors, and individual and organizational performance in a public sector context.

What is the public sector?

Before we discuss the relevance and distinctiveness of studying strategic HRM and performance in a public sector context, we first need to clarify what constitutes the public sector (Perry & Rainey, Citation1988). We adopt Knies and Leisink’s (Citation2017) typology which states that the first set of criteria are ‘formal’ in nature and include ownership, funding, and authority. In this way, organizations are categorized as public when they are government-owned, government-funded, and when political authorities are the primary stakeholders (Rainey, Citation2009). This set of criteria works well for some types of public organizations (e.g. local and national government), but not all. For example, healthcare organizations in the U.K. are classified as public, whereas in the Netherlands they are legally private providing a public service. Therefore, Knies and Leisink complement this set of criteria with the notion of public value (Moore, Citation1995). In this way, non-profit and private organizations would be classed as ‘public’ when they create public value for citizens. We follow this broad definition by using two sets of criteria to define what constitutes the public sector: formal criteria based on ownership, funding, and authority, and the creation of public value. In line with this approach, this special issue includes papers about hospitals, elderly care, primary and vocational education, and intergovernmental international organizations (United Nations).

Studying HRM in the public sector: not just ‘business as usual’

Here we argue that the public sector is not just another context when it comes to studying questions of HRM and performance. We believe there are often far-reaching implications for the study of HRM within the public sector, so applying ‘what works’ in private sector contexts to the public sector is too simplistic. We do not believe scholars should view lessons from private sector studies as ‘business as usual’ by giving no or limited thought to the public sector context. The public sector has characteristics that make research into HRM and performance complex and distinctive from studies conducted in private sector contexts. At the same time, we do acknowledge that there is much for public management scholars to learn from private sector research. Nevertheless, we believe that the following three distinctive features lie at the heart of the HRM and performance debate within the public sector (Guest, Citation1997, p. 263): the nature of organizational performance, the nature of HRM, and the linkages between the two (for an elaborate discussion of these issues see Knies & Leisink, Citation2017).

The first characteristic that distinguishes public organizations from private ones is the fact that private sector organizations have a single bottom-line (maximizing profit), whereas public sector organizations do not (Boxall & Purcell, Citation2011). Achieving the mission is the ultimate goal of public organizations in that the mission ‘defines the value that the organization intends to produce for its stakeholders and society at large’ (Moore, Citation2000, pp. 189, 190). This value is generally authorized by politicians. According to Rainey and Steinbauer (Citation1999, p. 13) ‘evidence that the agencies’ operations have contributed substantially to the achievement of these goals [included in the mission] provides evidence of agency effectiveness’. The mission can involve multiple goals that often conflict (Rainey, Citation2009). This is a distinctive feature of public organizations that has important implications for studying HRM in this context. For example, the police service has to fight crime on the one hand but prevent it on the other. These roles tend to involve extremes, such as dealing with criminals and the general public, and knowing how to manage both peaceful and violent interactions. Public organizations also endeavor to provide high quality services equitably with public monies used to create public value for the benefit of the public at large rather than individual citizens.

The second distinctive characteristic relates to HRM, more precisely the set of HR practices that is implemented to contribute to performance or mission achievement. Empirical evidence shows that not all HR practices are suitable for application in public sector organizations, given the nature of services provided, characteristics of public sector employees, and the fact that public organizations are accountable for the ways in which they spend public funds (Kalleberg, Marsden, Reynolds, & Knoke, Citation2006). Empirical evidence suggests that many public organizations have adopted bundles of ability- and opportunity-enhancing HR practices, but far fewer motivation-enhancing practices (Boyne, Jenkins, & Poole, Citation1999; Kalleberg et al., Citation2006; Vermeeren, Citation2014). That is, HR practices that are compatible with the humanistic goals of public organizations, aimed at strengthening employees’ abilities and opportunities to participate in decision-making are more prevalent in the public sector, whereas financial incentives are used to a lesser extent, because they may ‘crowd out’ intrinsic motivation (Georgellis, Iossa, & Tabvuma, Citation2011). However, not all decisions regarding the implementation of HR practices are strategic, as public sector HR practices are also subject to a high degree of institutionalization. That is, various stakeholders (such as politicians or unions) have more influence on public sector HR practices compared to the private sector. For example, policies related to pay and employee benefits are subject to collective bargaining. As such, this implies that the adoption of HR practices needs to be contextualized when studying public organizations.

The third distinction relates to the relationship between HRM and outcomes, and is twofold. First, a prominent question in the literature on HRM and performance in the public sector is to what extent public managers can influence employee performance given the constraints on managerial autonomy and the prevalence of red tape. Adherence to excessive red tape has resulted in compliance cultures with managers viewed as ‘guardians’ of established rules and procedures (Bozeman, Citation1993; Knies & Leisink, Citation2014; Rainey, Citation2009). Second, a related question – assuming public managers can to some extent at least, impact employee performance – is what mechanisms link the practice of HRM with these performance outcomes? Wright and Nishii (Citation2013) have proposed a general value chain outlining the mediating variables linking HRM and performance, in particular employees’ attitudes and behaviors. This value chain can also be applied to the public sector, but needs to be adjusted to fit the distinctive motivational context of public employees. Here we specifically refer to public service motivation (PSM). PSM is defined as ‘an individual’s orientation to delivering services to people with a purpose of doing good for others and for society’ (Perry & Hondeghem, Citation2008, p. vii), and is shown to be positively related to mission achievement of public organizations (e.g. Bellé, Citation2013; Vandenabeele, Citation2009). From this we can conclude that the mediating variables in the HRM value chain should be relevant to the public context and may not reflect mechanisms reported in private sector studies.

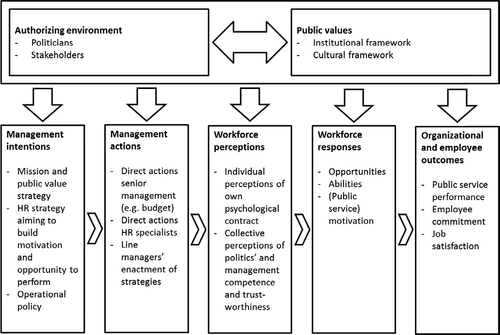

Vandenabeele, Leisink, and Knies (Citation2013) developed a model entitled ‘public value creation’ summarizing the insights presented above, which can serve as contextualized alternative for the general HRM value chain, when conducting research in a public sector context (see Figure ). This model creates a bridge between the public administration/public management disciplines on the one hand and the HRM discipline on the other by using theories from both bodies of literature. The public value creation model builds on the HRM process model (Wright & Nishii, Citation2013), the AMO model (Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, & Kalleberg, Citation2001), and the Harvard model (Beer, Spector, Lawrence, Mills, & Walton, Citation1984) from the HRM literature, the notions of public value (Moore, Citation1995), public values (Jorgensen & Bozeman, Citation2007), and public service motivation (Perry & Wise, Citation1990) from the public administration/public management literature, and institutional theory (Scott, Citation1995) which is used in both disciplines. The model highlights several distinctive characteristics: the authorizing environment (politicians, stakeholders) and public values that influence the complete value chain, public service performance/public value as an ultimate outcome, and several distinctive management and workforce characteristics (such as public service motivation). This model forms the conceptual framework of this special issue.

Figure 1. Public value creation (Vandenabeele et al., Citation2013, p. 48).

Contextualizing in HRM: a balancing act

In the previous section, we built a case for contextualizing studies of HRM and performance. Here, we address the question of how scholars can contextualize their work. In doing so, we build on the work by Delery and Doty (Citation1996), and Boxall, Purcell, and Wright (Citation2007) who respectively focus on substantive and process-oriented issues of contextualizing. Delery and Doty (Citation1996) distinguished three modes of theorizing in strategic HRM: a universalistic approach, which claims that HR practices are universally effective; a configurational approach, which assumes synergetic effects among HR practices; and a contingency approach, which suggests that HRM is contingent on an organization’s strategy. These three modes suggest an ascending level of contextualization which moves beyond a best practices approach. Boxall et al. (Citation2007) also make a claim for contextualizing. They coined the term ‘analytical HRM’ which primary task is to: ‘build theory and gather empirical data in order to account for the way management actually behaves in organizing work and managing people across different jobs, workplaces, companies, industries, and societies’ (p. 4). In discussing their analytical approach they point to the importance of crossing boundaries between disciplines, and of balancing rigour and relevance. That is, researchers should strive for research that is relevant for the particular context they are studying by contextualizing, on the other hand this research should be rigorous building on previous research and applying adequate research methods and techniques. This can be a balancing act for individual researchers.

In this section, we distinguish three levels of contextualization (basic, intermediate, advanced) (see Table ) which parallel the three modes of theorizing by Delery and Doty. To this end, we provide examples from public sector studies that have been published in the International Journal of Human Resource Management, and we discuss the implications for the rigour and relevance of empirical studies. For the sake of the argument, we follow the common structure adopted by the majority of HRM-performance papers based on quantitative research designs.

Table 1. How to contextualize a paper.

The first level of contextualization is where the author makes reference to the public sector in the introduction and conclusion or discussion sections of their paper only. We refer to this as a ‘basic’ level of contextualization (cf. Delery & Doty’s universalistic mode). We contend that when undertaking HRM studies in the public sector, authors should at least highlight in the introduction the relevance of the public sector context and how it differs from mainstream studies. The concluding section should provide a reflection on the generalizability and/or distinctiveness of the findings. An example of the application of a ‘basic’ level of contextualization, is a recent study about innovative work behavior in the public sector by Bos-Nehles, Bondarouk, and Nijenhuis (Citation2017). In the abstract and introduction the authors clearly state how the public sector context is relevant for their topic of study and how the public sector context is different from the private sector: ‘Studying innovative employee behaviors within knowledge intensive public sector organizations (KIPSOs) might seem an odd thing to do given the lack of competitive pressures, the limited identification of the costs and benefits of innovative ideas and the lack of opportunities to incentivize employees financially. Nevertheless, KIPSOs require innovations to ensure long-term survival. To help achieve this goal, this paper …’ (p. 379). Another example is a study by Su, Baird, and Blair (Citation2013) about employee organizational commitment (EOC) in the public sector. In the introduction of their paper they clearly state why a study of EOC in the public sector is relevant. In the discussion they explicitly compare their results with those from previous private sector studies and address public sector-specific findings: ‘a comparison of the level of EOC with that reported in Su et al. (2009) revealed that the level of EOC in the public sector is now on par with the level of EOC reported in the private sector’ (p. 256) and ‘the fact that job stability was not associated with the level of EOC for public sector organizations could be attributed to the traditionally higher levels of job stability in these organizations’ (p. 258).

The second or ‘intermediate’ level of contextualization involves using theories and concepts from a range of literatures (e.g. public management, public administration, and HRM) and reflecting on the implications of the empirical findings for the different bodies of knowledge. Notable ‘intermediate’ contextualized studies include Park and Rainey’s (Citation2012) research on motivation and social communication amongst public managers, in which they consider the effects of red tape and PSM; Bordogna and Neri’s (Citation2011) analysis of the transformations of public service employment relations in two countries, using the concept of new public management (NPM); and Williams, Rayner, and Allinson’s (Citation2012) research on the mediated relationship between NPM and organizational commitment. In all these studies, insights from the HRM literature are combined with insights from the public management and public administration disciplines, which is reflected in the use of citations to articles published in journals such as Public Administration Review, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, and Public Management Review.

We refer to the third and final level of contextualization as ‘advanced’, which usually applies to variables and measures developed for use in the public sector. At times this involves adjusting variables and scales to measure features that are distinct to the public sector, hence the measures achieve a close fit with the specific context. In the main, these measures are generally concerned with performance outcomes. Although such contextualization is rare for articles published in the International Journal of Human Resource Management, there are notable exceptions such as Eaton’s (Citation2000) study linking HRM to patient quality care in nursing homes, and Bartram, Karimi, Leggat, and Stanton’s (Citation2014) study linking high performance work systems to patient care in hospitals. These are highly contextualized applications of the general HRM and performance question in the context of nursing homes and hospitals, where the dependent variable (performance) is adjusted to fit the particular context (quality of patient care).

Although there are good reasons to contextualize HRM research (it increases the fit with the context and therefore it contributes to the relevance of the study) (Boxall et al., Citation2007), there are also potential downsides. When the level of contextualization increases, generalizability of the results decreases along with opportunities to compare the results with studies conducted in other contexts (Dewettinck & Remue, Citation2011). Some would even suggest that contextualizing could threaten the rigour of empirical studies, especially when instead of previously developed scales, newly developed (non-validated) measures are used to fit the context. This implies that contextualizing in HRM is a balancing act (see also Dewettinck & Remue, Citation2011) which requires careful consideration how and to what extent context is incorporated, finding the tipping point between rigor and relevance. In this special issue we aim to gain more insight into public sector-specific matters related to HRM and performance, without losing sight of the general picture that is relevant beyond the scope of the public sector.

About this special issue

In May 2015, a seminar dedicated to this special issue on SHRM and public sector performance was organized at Utrecht University (the Netherlands). Researchers from all over the world submitted papers to the seminar showing the broad and global interest for SHRM research in the public sector. In the end, six papers were selected for this special issue covering a wide range of HRM themes (e.g. performance management, leadership, team learning, job demands-resources, and person-organization fit), from different countries (Belgium, China, Germany, and the Netherlands), and different services (elderly care, health care, primary and vocational education, and intergovernmental international organizations). The wide range of services offered by public sector organizations provide opportunities to test the effects of context-specific characteristics on HRM, performance and the linkage between the two (see the model by Vandenabeele et al. (Citation2013)). Below we will present each of the six papers of the special issue on SHRM and public sector performance briefly.

Oppel et al. (Citation2016) study HRM and employee outcomes in German public and private hospitals. The authors look at recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal and incentives, in relation to employee attitudes of both physicians and nurses. The inclusion of data from physicians is both interesting and relevant given the dominance of HRM research on nurses. One of the reasons for the lack of research from physicians is the fact that data collection is much more difficult within these specific employee groups. Physicians are classic professionals with strong professionals norms, values and regulations that affect employment relationships within hospitals. Employee attitudes are measured by job satisfaction, job motivation, and organizational commitment. The findings show a difference between public and private hospitals suggesting the relevance of ownership as part of contextualization of SHRM research. There are several differences in the impact of specific SHRM domains on attitudes of physicians vs. nurses, suggesting the necessity of employee differentiation within public sector organizations taking into account professional specific characteristics.

The focus of the paper by Audenaert et al. (Citation2016) is the about the link between employee performance management at the organizational level and individual innovation, whereas the locus is elderly care in Belgium. The data used is a multilevel set, in which leader-member exchange is used as a moderator in the aforementioned relationship. This paper has two features that make it even more appealing and make it serve as a bridge between HRM and PA. First, the topic is particularly inspiring for HRM, as innovation is a topic not often associated with public services by some people – who then tend to forget that government employees have invented the first computer as an outcome of their innovative behaviour or have put men on the moon by their innovations. Second, the paper is equally inspiring for PA as it includes individual relationship with a leader as a driver for behaviour, which focuses the explanation on both the leader and the individual. These latter two actors are precisely the ones that have long been ignore in running public affairs under the – wrongful – assumptions that employees can be replaced and that structures can replace leaders. Both lessons demonstrate the necessity of bridging HRM and PA.

Vekeman et al. (Citation2016) focus their HRM research on Belgian primary schools. The authors combine a SHRM approach based on configurations, bundles, and resource based view insights with theory on person-organization (PO) fit. The main focus is on teachers and mixed methods were applied using survey data from teachers and interview data from school principals. The findings show potential impact of SHRM aimed at teachers with a crucial role of school leaders. It is not just HRM that matters with respect to optimal person-organization fit, but the vision, mission and enactment of school leaders as well. Schools are ‘people businesses’ and human services organizations in which the human capital matters in a strong and intense relationship with the clients (the students). Other HRM research (Knies & Leisink, Citation2014) also shows how important leadership is in the successful enactment of HRM in public sector organizations. Research on HRM in education (including primary schools, secondary schools, and higher education) is still in its infancy and research such as the study by Vekeman et al. (Citation2016) is valuable for showing the relevance of sectoral differences even within the public sector.

The Bouwmans et al. (Citation2017) article seeks to determine whether HR practices, designed to promote team working amongst teachers in vocational and training institutions in the Netherlands, produce desired effects. This is an important context to test the effects of HR practices, as historically teachers responsible for vocational education in the Netherlands did not engage nor desire to engage in team-working activities. Bouwmans et al. rely on a well-established HRM theory to test their hypotheses, namely AMO theory (Appelbaum et al., Citation2001). They adjust the usual battery of ability-, motivating- and opportunity-promoting HR practices to reflect team-orientation. Of particular note are their efforts to identify the mechanisms (team-commitment and willingness to engage in information processes) through which team-oriented HR practices affect team performance (innovation and efficiency – key outcomes for contemporary public sector organizations). In this way their paper directly links to the central issues of this special issue. Their research uses responses from 704 teachers working in 70 teams based in 19 Dutch vocational educational teaching institutions. Based on multilevel structural equation modelling, their findings confirm their hypotheses that team-oriented HR practices are indeed linked to desirable team-oriented outcomes, such as innovation and efficiency, with both team-commitment and willingness to engage in information processing partially mediating this relationship.

The paper by Giauque et al. (Citation2016) focuses on stress and turnover intents in intergovernmental international organizations building on the job demands-resources model and insights on HRM and employee well-being. There is little or no empirical HRM research within international organizations (IOs) such as the United Nations. IOs represent very specific organizations with unique contexts that can be characterized by significant impact of (international) politics and institutional mechanisms. IOs often employ a significant number of expatriates who live and work in challenging environments. This is likely to cause stress and employee turnover. The results show that social support and work-life balance reduce stress levels and turnover intention among employees of an IO. Red tape and expatriation status have detrimental effects on stress perception. Some of the findings are fully in line with similar research in the private sector, while other findings, in particular the findings related to red tape and status, are highly context-specific. The generalizability is in the underlying mechanisms of the job demands-resource model with respect to for example social support.

Many countries and states have driven through managerial changes based on so-called ‘best practice’ HRM in an attempt to improve the productivity of public sector organizations. Chinese state government is no exception. Wang et al. (Citation2017) undertake exploratory research in a public university to assess whether national values and state involvement influences an important HR practice, performance appraisals. Public universities in China not only receive state funding and support (Knies & Leisink, Citation2017), but are also subjected to government involvement in HR processes. Wang et al. anticipate that the China Party state government will influence workers’ perceptions of performance appraisals in a very different way to that experienced in the west. On the basis of interviews using 18 university ‘middle’ managers (deans, associate deans and heads of section), Wang et al. report the tensions experienced by respondents who endeavor to balance their academic work (undertaking research) with their desire for increased status and prestige associated with administrative responsibilities (official worship). Also, tightly held social norms were found to shape employees’ responses to performance management practices to the extent that identifying under-performance became problematic due to guan-xi (the power of personal relationships). In this way, this study suggests that the Chinese state government may experience significant challenges when relying on western ‘best’ HR practices to address productivity issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. (2001). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Arthur, J. B. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal , 37, 670–687.10.2307/256705

- Audenaert, M., Decramer, A., George, B., Verschuere, B., & Van Waeyenberg, T. (2016). When employee performance management affects individual innovation in public organizations: The role of consistency and LMX. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1–20.

- Bartram, T., Karimi, L., Leggat, S. G., & Stanton, P. (2014). Social identification: Linking high performance work systems, psychological empowerment and patient care. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 25, 2401–2419.10.1080/09585192.2014.880152

- Beer, M., Spector, B., Lawrence, P., Mills, D., & Walton, R. (1984). Managing human assets. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Bellé, N. (2013). Experimental evidence on the relationship between public service motivation and job performance. Public Administration Review , 73, 143–153.10.1111/puar.2013.73.issue-1

- Bordogna, L., & Neri, S. (2011). Convergence towards an NPM programme or different models? Public service employment relations in Italy and France. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 22, 2311–2330.10.1080/09585192.2011.584393

- Bos-Nehles, A., Bondarouk, T., & Nijenhuis, K. (2017). Innovative work behaviour in knowledge-intensive public sector organizations: The case of supervisors in the Netherlands fire services. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 28, 379–398.

- Bouwmans, M., Runhaar, P., Wesselink, R., & Mulder, M. (2017). Stimulating teachers’ team performance through team-oriented HR practices: The roles of affective team commitment and information processing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1–23.

- Boxall, P., & Purcell, J. (2011). Strategy and human resource management (3rd ed.). Houndsmill: Palgrave.

- Boxall, P., Purcell, J., & Wright, P. (2007). Human resource management: Scope, analysis, and significance. In P. Boxall, J. Purcell, & P. Wright (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of human resource management (pp. 1–16). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boyne, G., Jenkins, G., & Poole, M. (1999). Human resource management in the public and private sectors: An empirical comparison. Public Administration , 77, 407–420.10.1111/padm.1999.77.issue-2

- Bozeman, B. (1993). A theory of government ‘red tape’. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , 3, 273–303.

- Combs, J., Liu, Y., Hall, A., & Ketchen, D. (2006). How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Personnel Psychology , 59, 501–528.10.1111/peps.2006.59.issue-3

- Delery, J. E., & Doty, D. H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Academy of Management Journal , 39, 802–835.10.2307/256713

- Dewettinck, K., & Remue, J. (2011). Contextualizing HRM in comparative research: The role of the Cranet network. Human Resource Management Review , 21, 37–49.10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.09.010

- Eaton, S. C. (2000). Beyond ‘unloving care’: Linking human resource management and patient care quality in nursing homes. International Journal of Human Resource Management , 11, 591–616.10.1080/095851900339774

- Georgellis, Y., Iossa, E., & Tabvuma, V. (2011). Crowding out intrinsic motivation in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , 21, 473–493.10.1093/jopart/muq073

- Giauque, D., Anderfuhren-Biget, S., & Varone, F. (2016). Stress and turnover intents in international organizations: Social support and work–life balance as resources. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1–23.

- Guest, D. E. (1997). Human resource management and performance: A review and research agenda. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 8, 263–276.10.1080/095851997341630

- Jorgensen, T. B., & Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values: An inventory. Administration and Society , 39, 354–381.10.1177/0095399707300703

- Kalleberg, A., Marsden, P., Reynolds, J., & Knoke, D. (2006). Beyond profit? Sectoral differences in high-performance work practices. Work and Occupations , 33, 271–302.10.1177/0730888406290049

- Knies, E., & Leisink, P. L. M. (2014). Leadership behavior in public organizations: A study of supervisory support by police and medical center middle managers. Review of Public Personnel Administration , 34, 108–127.10.1177/0734371X13510851

- Knies, E., & Leisink, P. L. M. (2017). People management in the public sector. In C. J. Brewster & J. L. Cerdin (Eds.), Not for the money: People management in mission driven organizations (pp. 15–46). Cham: Palgrave/Macmillan.

- Messersmith, J. G., Patel, P. C., Lepak, D. P., & Gould-Williams, J. S. (2011). Unlocking the black box: Exploring the link between high-performance work systems and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology , 96, 1105–1118.10.1037/a0024710

- Moore, M. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moore, M. (2000). Managing for value: Organizational strategy in for-profit, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly , 29, 183–204.10.1177/0899764000291S009

- Ongaro, E., & Van Thiel, S. (2017). The Palgrave handbook of public administration and management in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Oppel, E. M., Winter, V., & Schreyögg, J. (2016). Examining the relationship between strategic HRM and hospital employees’ work attitudes: An analysis across occupational groups in public and private hospitals. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1–21.

- Park, S. M., & Rainey, H. G. (2012). Work motivation and social communication among public managers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 23, 2630–2660.10.1080/09585192.2011.637060

- Perry, J. L., & Hondeghem, A. (2008). Preface. In J. L. Perry & A. Hondeghem (Eds.), Motivation in public management (pp. 1–14). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, J. L., & Rainey, H. (1988). The public-private distinction in organization theory: A critique and research strategy. Academy of Management Review , 13, 182–201.

- Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public Administration Review , 50, 367–373.10.2307/976618

- Rainey, H. G. (2009). Understanding and managing public organizations (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Rainey, H. G., & Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , 9, 1–32.10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024401

- Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Su, S., Baird, K., & Blair, B. (2009). Employee organizational commitment: The influence of cultural and organizational factors in the australian manufacturing industry. International Journal of Human Resource Management , 20, 2494–2516.

- Su, S., Baird, K., & Blair, B. (2013). Employee organizational commitment in the Australian public sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 24, 243–264.10.1080/09585192.2012.731775

- Vandenabeele, W. (2009). The mediating effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on self-reported performance: More robust evidence of the PSM-performance relationship. International Review of Administrative Sciences , 75, 11–34.

- Vandenabeele, W. V., Leisink, P. L. M., & Knies, E. (2013). Public value creation and strategic human resource management: Public service motivation as a linking mechanism. In P. L. M. Leisink, P. Boselie, M. van Bottenburg, & D. M. Hosking (Eds.), Managing social issues: A public values perspective (pp. 37–54). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Van De Voorde, K., Paauwe, J., & Van Veldhoven, M. (2010). Predicting business unit performance using employee surveys: Monitoring HRM-related changes. Human Resource Management Journal , 20, 44–63.10.1111/hrmj.2010.20.issue-1

- Vekeman, E., Devos, G., & Valcke, M. (2016). The relationship between principals’ configuration of a bundle of HR practices for new teachers and teachers’ person–organisation fit. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1–21.

- Vermeeren, B. (2014). HRM implementation and performance in the public sector ( PhD thesis). Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

- Wang, M., Zhu, C. J., Mayson, S., & Chen, W. (2017). Contextualizing performance appraisal practices in Chinese public sector organizations: The importance of context and areas for future study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1–18.

- Williams, H. M., Rayner, J., & Allinson, C. W. (2012). New public management and organisational commitment in the public sector: Testing a mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 23, 2615–2629.10.1080/09585192.2011.633275

- Wright, P. M., & Nishii, L. H. (2013). Strategic HRM and organizational behaviour: Integrating multiple levels of analysis. In J. Paauwe, D. Guest, & P. Wright (Eds.), HRM & performance: Achievements & challenges (pp. 97–110). Chichester: Wiley.