Abstract

Although organizational support has long been considered a cornerstone of expatriate success, more research is needed to understand how different types of support affect the career outcomes of women expatriates. We draw on strategic human resource management theory to show that organizations interested in gaining or maintaining a strategic competitive advantage should attend to the under-representation of women expatriates. We posit that general (i.e. perceived organizational support [POS]) and targeted (i.e. organizational cultural intelligence [OCQ], family-supportive work perceptions [FSOP]) support perceptions can foster a strategic advantage by addressing the barriers barring women from expatriate assignments. We use two samples to test a model wherein general and targeted support perceptions increase three longevity attitudes (i.e. commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness) through adjustment. Results showed that POS did not significantly increase adjustment and subsequent longevity attitudes for men or women. Then, OCQ aided male employees’ adjustment (as did FSOP to a lesser degree), leading to heightened commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness. Women, in contrast, were aided by FSOP, but not OCQ.

In light of the expected boom in the number of expats around the world, and the associated benefits expats bring to the table, organizations cannot afford to overlook women in their global leadership development programs. – (Welsh & Kersten, Citation2014)

Globalization has given rise to a steady increase in expatriate workers, employees who leave their home-country to live and work abroad (Kraimer, Bolino, & Mead, Citation2016). Despite these growing numbers, only 25% of expatriates are women (Brookfield Global Relocation Services, 2016). In light of the projected increased need for expatriates (Tung & Varma, Citation2008), failing to address the under-representation of women is no longer an option for firms that want to attain or maintain a strategic competitive advantage. Management scholars echo this sentiment (e.g. Shortland, Citation2018a; Varma & Russell, Citation2016), as illustrated by the following conclusion by Shortland (Citation2016, p. 656): ‘expatriate gender diversity [simply] makes sound business sense’. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to examine how organizations can support women expatriates to strategically leverage these underutilized human resources.

Specifically, in the present study we draw on strategic human resource management (SHRM) theory (Wright & McMahan, Citation1992) to explain why organizations should consider targeted support for women expatriates (Tung, Citation2016). Current research shows that many organizations are not replacing expatriates at sustainable rates (Stahl, Chua, Caligiuri, Cerdin, & Taniguchi, Citation2009). We contend that targeted support will help organizations attract and retain more women expatriates because doing so addresses two major barriers to women’s entry into this work segment (Shortland, Citation2018b): (a) institutional discrimination that affects women’s attraction and retention and (b) their desire to maximize success in both work and home domains.

Although prior scholars have suggested that women expatriates may benefit from perceived organizational support (e.g. Shen & Jiang, Citation2015; Varma & Russell, Citation2016), few have considered the different types of organizational support that are most effective for women. In a qualitative exception, Hutchings, Lirio, and Metcalfe, (Citation2012) concluded that training and policies aimed at reducing cultural constraints and work–family imbalance experienced by women expatriates are key in maximizing success for these employees. Thus, we build on these studies by empirically testing the effects of general and targeted support perceptions on women expatriate adjustment and subsequent longevity attitudes.

In doing so, we answer recent calls to better understand the experiences of expatriate women as compared to men (Cole & McNulty, Citation2011; Salamin & Davoine, Citation2015), how organizations can facilitate expatriate success (Caligiuri & Bonache, Citation2016), and, in particular, how they can best support women expatriates (Kraimer et al., Citation2016). Such knowledge is also practically relevant given that only 20% of organizations are addressing expatriate gender diversity issues, as described by the 2018 Trends in Global Mobility report:

while addressing the needs of diversity and inclusiveness at the C-suite level is a hot topic, it has not yet made its way to the implementation level when it comes to adapting [global] mobility programs and policies to meet the needs of [this] more diverse population (CARTUS, Citation2018).

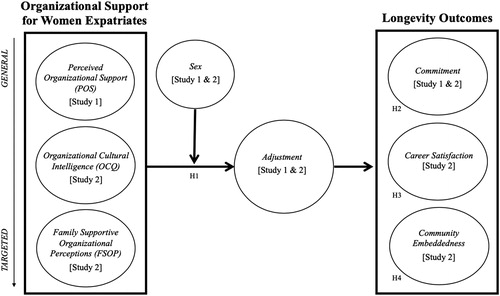

The remainder of the manuscript is organized as follows. First, we review the literature highlighting the unique barriers that women expatriates face. Second, we discuss the role of SHRM theory in examining how to better support expatriates. That is, we examine the impact of three organizational support perceptions on adjustment: general support (i.e. perceived organizational support [POS]), targeted expatriate support (i.e. organizational cultural intelligence [OCQ]), and targeted support for women expatriates (i.e. family-supportive organizational perceptions [FSOP]). Third, we hypothesize how these support perceptions augment adjustment and indirectly relate to three longevity attitudes (defined as indicators of general satisfaction with one’s life circumstances as well as intentions to remain in an international assignment): organizational commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness (see ). Overall, we investigate how sex may alter the relationship between organizational support and expatriate longevity outcomes.

Figure 1. Hypothesized model.

Notes. In Study 1, POS and sex were measured at T1, adjustment was measured at T2 (while controlling for adjustment at T1). Commitment was measured at T2. In Study 2, OCQ, FSOP, sex, adjustment, commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness were measured at T1.

The unique experiences of women expatriates

Prior scholarship shows that institutional barriers and discrimination against women expatriates remain widespread (Bader, Stoermer, Bader, & Schuster, Citation2018), negatively impacting the selection and retention of women expatriates. First, the selection systems for expatriates are often informal and subjective (Linehan & Scullion, Citation2001), leading staffing decisions to be particularly susceptible to biases (Harris, Citation2002). Exacerbating this, women also often lack close mentoring relationships with supervisors (Linehan & Walsh, Citation1999) who could potentially provide access to expatriate assignments. Moreover, institutional discrimination (e.g. differential treatment) can impact women expatriate retention. This can take many forms, including harassment (Bader et al., Citation2018) and social isolation (Hutchings et al., Citation2012). In sum, decades of research have shown that women are likely to face more cultural constraints, corporate resistance, and stereotypes about their expatriation interest than their male peers (Adler, Citation1987; Altman & Shortland, Citation2008; Shortland, Citation2018b).

Second, Shortland (Citation2018b) notes that women’s preferences to satisfice or maximize both work and family goals needs to be considered to address their under-representation. Women are often unwilling to sacrifice one arena of their lives for the other (Crompton & Harris, Citation1998) and thus make strategic choices about how to reach goals in both domains simultaneously (Shortland, Citation2018b). As expatriate roles increasingly become short term and unaccompanied (Caligiuri & Bonache, Citation2016), women may decide that the career boosts of expatriate roles are not enough to compensate for the sacrifice the family endures (Shortland, Citation2018b). Supporting this, research has noted that women are concerned (more than men) with accommodating their spouse’s career (Känsala, Mäkelä, & Suutari, Citation2015), suffer more if their spouses fail to adjust to foreign environments (Cole, Citation2011), and are deeply concerned with their children’s education and well-being (Puchmüller & Fischlmayr, Citation2017). In light of the barriers they face, however, we suggest that targeted support for women expatriates will make the choice of accepting and remaining on an assignment easier while helping to counteract any systematic biases and discrimination. Considered together with the fact that women express a willingness to accept expatriate positions (Stroh, Varma, & Valy-Durbin, Citation2000) and perform well once on the job (Harrison & Michailova, Citation2012; Tung, Citation2004), suggests that women and their organizations may benefit from their increased support.

The role of SHRM theory in women expatriate longevity attitudes

To leverage expatriates as human resources, managers must strategically attract and support these unique employees. SHRM, ‘the pattern of planned HR deployments and activities intended to enable the firm to achieve its goals’ (Wright & McMahan, Citation1992, p. 298), concerns itself with how organizations select, develop, retain, and utilize their human capital to achieve organizational objectives. Essentially, employees are construed as resources that can positively contribute to the organization (Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011). To date, a SHRM approach has proven effective to combat the challenging aspects of expatriate assignments (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004), especially after Jackson, Schuler, and Jiang, (Citation2014) drew research attention to SHRM in the expatriate domain. For example, a large portion of recent research (see Caligiuri & Bonache, Citation2016 for a recent review) focuses on two SHRM tactics: (a) ensuring candidates are a good fit for cross-cultural environments (i.e. selection) or (b) certifying expatriates in cultural competencies before their assignment (i.e. training).

Unfortunately, in our review of the expatriate literature, we did not find any previous systematic treatment of women expatriate issues using a SHRM lens. We believe that SHRM theory can guide organizations in enhancing their strategic efforts to support women expatriates. A number of indicators (e.g. consistently low levels of adjustment and high expatriate turnover rates; Stahl et al., Citation2009) suggest that HRM theories need to expand to increase the effectiveness of how scholars and practitioners think about the management of women expatriates. Supporting this idea, scholars have commented on missed opportunities by organizations that improperly support women expatriates (e.g. Caligiuri & Lazarova, Citation2002). We develop two primary points underlying our use of a SHRM lens to study women expatriates: (a) It is strategic for organizations to attract and retain women expatriates, and (b) targeted support for women expatriates is strategic because organizations can address two viable reasons for the under-representation of women expatriates (Shortland, Citation2018b).

We suggest that it is strategic for organizations to prioritize support for women as a way to meet their international staffing needs. The demand for expatriates continues to increase (e.g. Tung & Varma, Citation2008; Varma & Russell, Citation2016). Indeed, Tung (Citation2016) noted that practitioner surveys consistently show that global talent shortages are among the most pressing topics discussed by top management teams. Yet, as noted by several recent reviews on women expatriates (Altman & Shortland, Citation2008; Salamin & Hanappi, Citation2014), the number of women expatriates has not dramatically increased to fill these talent gaps. The continued low level of women expatriates is particularly notable given that the generosity of expatriate packages has dwindled in recent years (ORC Worldwide, Citation2007), which, theoretically, would make such positions less attractive to men, opening up even more opportunities for women (Reskin & Roos, Citation1990). As such, it appears that organizations need to be more strategic in their attempts to attract and retain women expatriates to meet the demands for global talent.

We further argue that organizational support may be a tool that helps strategically increase the numbers of women expatriates. Varma and Russell (Citation2016, p. 202) similarly suggested that ‘by designing [support] programs specifically geared toward potential women expatriate candidates, organizations will be able to increase the number of women expatriates applying for, and succeeding in global roles…’. We build on this work and contend that targeted forms of support address two viable reasons for women’s low numbers (Shortland, Citation2018b): (a) institutional discrimination and (b) personal choices (i.e. maximizing achievement at work and home). Namely, organizational support can help counteract institutional discrimination (e.g. offering social activities for expatriate wives but not husbands; Lauring & Selmer, Citation2009) while also supporting these women with family goals.

Targeted organizational support as a SHRM intervention

Multiple types of expatriate support have been identified in previous work, including financial compensation, generous benefit packages (Cateora & Graham, Citation2005), fair rewards, help in decision-making, growth opportunities (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, & Hammer, Citation2011), relocation policies tailored to helping employees with their adjustment, career, finances, and family situations (Wu & Ang, Citation2011), and both pre-deployment preparation and in-country assistance (Peterson, Sargent, Napier, & Shim, Citation1996). To explore the strategic role that targeted support can have in addressing the under-representation of women expatriates, we examine three types of organizational support.

First, we consider non-targeted support perceptions, or the employee’s ‘general beliefs concerning how much the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being’ (i.e. POS; Rhoades, Eisenberger, & Armeli, Citation2001, p. 825). POS has been linked to expatriate adjustment, performance, and retention (Cao, Hirschi, & Deller, Citation2014) as employees experience reduced stress and an obligation to work hard to repay their organization (e.g. Chen & Shaffer, Citation2017; van der Laken, van Engen, van Veldhoven, & Paauwe, Citation2016). With regard to women expatriates specifically, Shen and Jiang, (Citation2015) found that high-POS muted the relationship between experienced prejudice and performance.

In terms of more targeted support, we also examine both OCQ and FSOP given that women expatriates experience considerable challenges related to both dealing with unfamiliar cultures (van der Laken, van Engen, van Veldhoven & Paauwe, Citation2016) and managing work–family balance (Fischlmayr & Kollinger, Citation2010). OCQ refers to firm’s ability ‘to function and manage effectively in culturally-diverse environments and to gain and sustain its competitive advantages’ (Yitman, Citation2013, p. 5). Moon (Citation2010) proposed that organizational CQ acts as a dynamic capability that enables organizations to effectively adapt and respond to fluid, culturally diverse settings. Essentially, OCQ captures the level that organizations are engaging in HR efforts (e.g. selection, training) that are culturally savvy and support expatriates to also be effective in cross-cultural interactions.

By incorporating cultural knowledge into HR functions, OCQ supports expatriates by building support structures throughout business operations that enable them to conduct international business effectively. As an example, a high-OCQ organization might establish country-specific HR policies including more group and fewer individual rewards in collectivistic cultures, reducing the amount of conflict management required by an expatriate manager in a society that values harmony. Alternatively, a low-OCQ organization might fail to train employees to display basic cultural etiquette, resulting in awkward cultural gaffes when meeting local clients. Research shows that OCQ can aid strategic efforts given demonstrated relationships with increased international strategic alliances (Yitman, Citation2013) and perceived organizational effectiveness and cohesion (van Driel & Gabrenya, Citation2013).

We also examine a type of organizational support that is specifically targeted at women expatriates. FSOP refers to the global perceptions that employees form about how supportive their organizations are of their families and nonwork lives (Kossek et al., Citation2011). Prior research notes that family-friendly benefits offered by the organization (Hammer, Neal, Newsom, Brockwood, & Colton, Citation2005), benefit usage, and family-supportive supervisors (Kossek et al., Citation2011) can all increase family-supportive organizational perceptions. FSOP has the potential to aid strategic organizational efforts, as it specifically targets barriers that are frequently cited as reasons women expatriates quit their assignments (CARTUS, Citation2018).

Effects of organizational support on expatriate adjustment and longevity attitudes

First, we examine the impact of support on women expatriate’s adjustment, defined as the extent to which employees are comfortable with multiple aspects of their new setting (Black & Gregersen, Citation1991). Adjustment is considered the most central of expatriate outcomes (Zhu, Wanberg, Harrison, & Diehn, Citation2016) and is a complex process that involves emotional, behavioral, and cognitive facets of the job, nonwork life, and the culture (Haslberger, Brewster, & Hippler, Citation2013). Prior studies have linked adjustment with career-related constructs including expatriate job satisfaction, performance, and quit intentions (Bhaskar-Shrinivas, Harrison, Shaffer, & Luk, Citation2005). We propose that various forms of organizational support will help women to adjust more readily to their expatriate roles by (a) helping them to maximize their nonwork and work goals simultaneously and (b) counterbalancing the negative effects of the discrimination they face. As alluded to above, though we expect that all expatriates (men and women) will benefit from heightened support, we hypothesize that women would benefit more than men given the unique barriers they face (Shortland, Citation2018b).

The notion that women expatriates may benefit from organizational and social support more than men has been advocated by a wide range of scholars (e.g. Caligiuri & Lazarova, Citation2002; Fischlmayr & Kollinger, Citation2010; Salamin & Davoine, Citation2015). Indeed, in their review on women expatriates, Altman and Shortland, (Citation2008) concluded that the unique constraints faced by women are created and reinforced by organizational norms and a lack of support. In sum, we suggest that organizational environments characterized by strong support (i.e. high POS, OCQ, or FSOP) signal to women expatriates that the organization is inclusive and supportive of their unique needs, reducing the weight of their burdens. High levels of support may encourage women employees to openly discuss the challenges they are facing and provide them with the tools that help them to resolve them. As such, we propose that organizational support will be more beneficial for women’s, as compared to men’s, adjustment given their unique experiences in the workplace, at home, and in the new cultural context.

H1: Sex moderates the relationship between organizational support ([a] POS, [b] OCQ, and [c] FSOP) and expatriate adjustment such that this relationship is stronger and more positive for women as compared to men.

We also expect that an increase in adjustment will lead to further positive outcomes related to expatriate success and a desire to stay in an international assignment (i.e. high longevity attitudes). Prior studies have linked adjustment with a variety of outcomes including expatriate job satisfaction, performance, and quit intentions (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., Citation2005). To build on these results, we consider how organizational support perceptions impact affective organizational commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness in the host country as a function of the expatriate’s sex.

First, we expect that low levels of support would lead to lowered organizational commitment through the mediating role of adjustment. Organizational commitment is an employee attitude reflecting a sense of loyalty that drives an employee to put forth effort to accomplish organizational goals (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, Citation2002). We focus on the affective component of commitment, defined as an employee’s desire to continue working because of an emotional attachment to the organization (Meyer et al., Citation2002). It is strategic to examine affective commitment in expatriate samples, as this longevity attitude has been positioned as one of the most important predictors of turnover generally (Meyer et al., Citation2002) as well as in expatriate contexts specifically (Gregersen & Black, Citation1990). We propose that when women expatriates feel supported by their organizations, they will more easily adjust to their new environment given the higher number of burdens and barriers they experience and will repay the organization with high levels of affective commitment.

H2: Sex moderates the indirect relationship between organizational support ([a] POS, [b] OCQ, and [c] FSOP) and organizational commitment through adjustment such that this link is stronger and more positive for women as compared to men.

Second, we hypothesize that low levels of adjustment will lead to low levels of career satisfaction. Surprisingly, relatively few researchers (e.g. Cao et al., Citation2014) have examined the antecedents of career satisfaction in the expatriate context. Career satisfaction refers to how much overlap exists between one’s career achievements and personally relevant success markers (Heslin, Citation2005), and has been inversely linked to turnover intentions (Joo & Park, Citation2010). Only one study has shown that POS leads to career satisfaction in the expatriate context (Cao et al., Citation2014). Career satisfaction is important to strategic HR efforts because expatriates that terminate their international assignments early can derail their careers (Zhu et al., Citation2016). In sum, we expected that when women perceive that their organization is helping them to resolve the unique problems they face, a greater satisfaction in their careers will arise as they no longer feel as though their careers are detracting from their nonwork lives.

H3: Sex moderates the indirect relationship between organizational support ([a] OCQ and [b] FSOP) and career satisfaction through adjustment such that this link is stronger and more positive for women as compared to men.

Third, we expected that decreased adjustment will lead to less embeddedness in one’s community within the host country. Little prior research has examined how organizational support relates to expatriate community embeddedness (e.g. Chen & Shaffer, Citation2017). Community embeddedness refers to the ties that employees have to the people, activities, and benefits of the place where they live and work (Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, & Erez, Citation2001). It is an important outcome of study not only because it can enhance expatriate performance (Andresen, Citation2015), but also because organizational and community factors combine to keep these employees from turning over (Ren, Shaffer, Harrison, Fu, & Fodchuk, Citation2014). We expect that support offered to women expatriates will help them resolve work and nonwork barriers, allowing them to embed more deeply in their communities.

H4: Sex moderates the indirect relationship between organizational support ([a] OCQ and [b] FSOP) and community embeddedness through adjustment such that this link is stronger and more positive for women as compared to men.

Overview of studies

Though we present a unified theoretical model in our introduction (see ), we test various facets of the model across two complementary field studies. Study 1 uses time-lagged data from 92 expatriates working in 34 different countries to test the moderating effects of sex on the indirect relationship between broad POS and commitment through adjustment (H1a and H2a). Study 2 employs a large field sample of expatriates (N = 1,129) in the UAE and expands the research model in a number of ways. First, we include additional forms of support that are targeted to expatriates (i.e. OCQ and FSOP). Second, we investigate two additional longevity attitudes in addition to the commitment outcome considered in Study 1. Third, we focus our sample on expatriates working in one country to eliminate a number of between-country confounds that could bias our results (Becker & Gerhart, Citation1996). Overall, by expanding our research model to test the moderating effects of sex on the indirect relationship between two forms of organizational support targeted toward expatriates (FSOP and OCQ) and adjustment (H1b-c) as well as three longevity attitudes (commitment H2b-c, career satisfaction H3a-b, and embeddedness H4a-b), we are able to consider additional aspects of support uncovered in Study 1.

Study 1 methods

Participants and procedure

We recruited participants to the Time 1 (T1) survey using advertisements posted in online public forums with active expatriate memberships (e.g. message boards, Facebook groups). Those who provided their e-mail at the end of the T1 survey were contacted six months later to fill out the Time 2 (T2) follow-up survey. Ninety-two participants fully completed both the T1 and T2 surveysFootnote1 (response rate for the T2 survey = 56%, which is comparable to other web-based surveys of working participants, Anseel, Lievens, Schollaert, and Choragwicka, Citation2010). The final sample (47.9% women) was generally middle aged (M = 42.96, SD = 11.03), married (70.2%), and well educated (79.8% held a Master’s degree or higher). The majority of our sample was American (60.6%), but several other nationalities were represented (e.g. the UK [9.6%], India [4.3%], Canada [4.3%]). Moreover, the expatriates worked in 34 countries (e.g. 9.6% in China, 7.4% in Greece, 6.4% in France).

Measures

Unless noted, we used Likert-type response anchors ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. We assessed POS (α = .87) at T1 using the eight-item scale by Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, and Sowa, (Citation1986; sample item: My organization really cares about my well-being). Respondents answered on a 1–7 scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Sex was reported at T1 by the expatriate and was dummy coded (i.e. men = 0; women = 1). Adjustment was measured at T1 (α = .87) and T2 (α = .84) with 13 items from the Expatriate Adjustment Scale (Black & Stephens, Citation1989). The measure asked participants to rate their adjustment with various aspects of the host country environment (sample item: ‘How poorly adjusted (1) or well-adjusted (5) you are to the following characteristics of your current country… Socializing with host nationals’). Further, we assessed affective commitment (α = .69) at T2 using the three positively worded items from Rhoades et al., (Citation2001; sample item: ‘this organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me’).

Analytic strategy

Our statistical models were estimated using the PROCESS macro designed by Hayes (Citation2018; version 3.0 of the macro) in SPSS version 24. First, we used model 1 to test the moderation model proposed in H1a. Specifically, in H1a we propose that sex moderates the relationship between organizational support for expatriates and expatriate longevity outcomes. Second, we used model 7 to test the first-stage moderated mediation models proposed in H2a (i.e. the indirect relationship between organizational support and expatriate longevity outcomes through adjustment). Extending this model, we further argue that the mediated effect differs depending on the sex of the expatriate. We capture the difference of the conditional indirect effects between men and women in the index of moderated mediation (IMM; Hayes, Citation2015). Finally, as recommended by Hayes (Citation2018), we use bias-corrected bootstrapping to test for statistical significance in the moderated mediation models.

Study 1 results and discussion

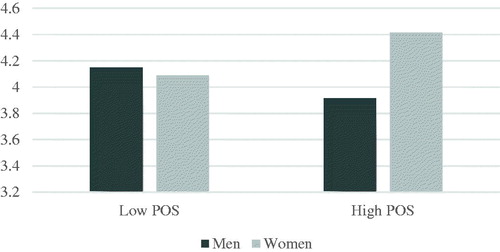

Descriptive statistics and correlations for men and women are presented in . H1a predicted that sex moderated the relationship between POS and adjustment, and H2a stated that sex positively moderates the indirect effects of POS on organizational commitment through adjustment.Footnote2 In weak support of H1a and as depicted in , we found that the interaction of POS with sex (b = 0.19, p = .03) did significantly predict T2 adjustment while controlling for T1 adjustment. Men had a negative, yet insignificant relationship between POS and adjustment (b = –0.09, p = .08), whereas women displayed a positive, yet insignificant relationship (b = 0.11, p = .15). As shown in , we also find weak evidence supporting H2a. Specifically, T2 adjustment was also significantly related to organizational commitment (b = 0.64, p < .001) and the index of moderated mediation (IMM) approached significance (IMM = .12, 95% CI = [.00, .25]). Once again, these indirect effects differed for men and women expatriates, although neither indirect effect reached significance. However, we note that the indirect effects of POS on commitment through T2 adjustment were negative for men (b = –0.05, 95% CI = [–0.12, 0.01]), but positive for women (b = 0.07, 95% CI = [–0.04, 0.18]). Moreover, the direct effects of POS on T2 adjustment were also positive and significant (b = .28, 95% CI = [0.15, 0.41]).

Figure 2. Relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and adjustment as moderated by sex in Study 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations for Study 1 by sex.

Table 2. The effects of perceived organizational support on commitment, as mediated by adjustment and moderated by sex in Study 1.

Though the Study 1 results did not fully support our predictions, they provided initial evidence of sex differences in the effects of support for expatriates. Based on these preliminary results, we determined it was necessary to test an expanded research model with a larger sample to more thoroughly investigate our research hypotheses.

Study 2

Next, we build on the findings of Study 1 by expanding our model within a different context (i.e. a single country: the UAE). Although using data from multiple countries enhances generalizability and having a diverse sample helped to address recent calls to study expatriate phenomena across various countries and companies (Kang & Shen, forthcoming), examining our model in one country likely reduces between-country variance and controls for a number of between-country confounds that could bias our results (Becker & Gerhart, Citation1996). We chose the UAE as the setting for our second study because sex egalitarianism has been traditionally low in the Middle East, with women occupying lower status in society. An environment where women expatriates feel inferior and invisible (70% of the population is male in the UAE) provides an ideal testing ground given that previous scholars have suggested that expatriate support for women may be even more critical in cultures with large gender inequities (e.g. Harrison & Michailova, Citation2012). Study 2 was also necessary because we wanted to test our hypotheses in a larger sample with more power to adequately assess whether two targeted types of organizational support perceptions (i.e. OCQ, FSOP) may be more beneficial to expatriates and, specifically, expatriate women.

Study 2 methods

Participants and procedures

We utilized a market research organization in Dubai to collect a sample of 1,129 expatriate employees living and working full time in the UAE. Market research personnel employed by the organization approached potential participants in public areas (e.g. shopping malls). If they consented, the personnel would then verbally ask the participant each survey question and recorded the answers on an electronic tablet. Demographics of the final sample were as follows: 30.5% were women, and 95% had lived in the UAE for more than two years. Our sample included expatriates with a variety of different nationalities and professions; they hailed from 53 different countries with the majority from India (23%), Pakistan (10.8%), Egypt (10.9%), the Philippines (10.7%), America (7.4%), and the UK (6.4%). Respondents also estimated the percentage of women in their workplace, and the average response was 34.12% (SD = 22.09), similar to global estimates (Brookfield Global Relocation Services, 2016).

Measures

Unless otherwise noted, all variables were measured on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The adjustment (α = .87), affective commitment (α = .82), and sexFootnote3 measures were the same as described in Study 1. We measured OCQ (α = .91) by adapting the Ang et al. (Citation2007) Cultural Intelligence Scale to apply to organizations. A sample item is ‘My organization adjusts its ways of doing business as it enters new countries and cultures’. Family-supportive organization perceptions (α = .78) were measured using Allen’s (Citation2001) nine-item FSOP measure. This scale captures employee perceptions of their organization’s practices, policies, and activities central to the integration of family and work. A sample item is ‘Employees are given ample opportunity to perform both their job and their personal responsibilities well’. We used Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley’s (1990) five-item measure to measure career satisfaction (α = .92) using responses measured on a seven-point scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree). A sample item is ‘I am satisfied with the success I have achieved in my career’. Finally, we assessed community embeddedness (α = .81) by merging the eight items of the Fit and Sacrifice subscales of Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, and Holtom, (Citation2004) measure of community embeddedness. A sample item is ‘I really love the place where I live’.

Analytic strategy

Our analytic strategy in Study 2 was the same as in Study 1. That is, statistical models were estimated using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2018; model 1 to test H1b and H1c and model 7 to test H2b, H2c, H3b, H3c, H4b, and H4c). We also use bias-corrected bootstrapping to test for statistical significance in the moderated mediation models as we did in Study 1.

Study 2 resultsFootnote4

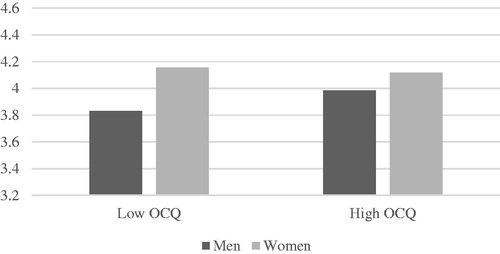

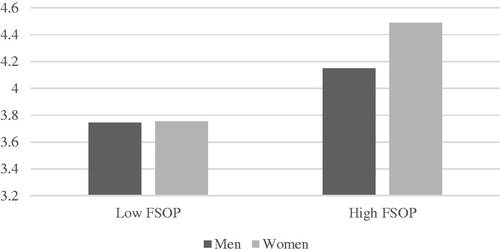

Descriptive statistics and correlations for men and women are presented in . H1b-c predicted that sex moderated the OCQ-adjustment and FSOP-adjustment relationships, respectively, such that women benefit more than men. We also hypothesized that OCQ and FSOP would indirectly relate to organizational commitment (H2b-c), career satisfaction (H3a-b), and community embeddedness (H4a-b) through adjustment, and that the relationship would again be stronger for women than men. Although we tested the six models for the two IVs and three DVs separately, we combined the results in and for parsimony.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlations for Study 2 by sex.

Table 4. The effects of organizational cultural intelligence and family supportive organizational perceptions on commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness as mediated by adjustment and moderated by sex in Study 2.

Table 5. Summary of the indirect effects of perceived organizational support (Study 1), organizational cultural intelligence (Study 2), and family-supportive organizational perceptions (Study 2) by sex.

As shown in and , the interactions between OCQ and sex (b = –0.29, p = .006) and FSOP and sex (b = 0.24, p < .001) both significantly predicted adjustment. Contrary to predictions, the effects of OCQ on adjustment were significant and positive for men (b = 0.23, p < .001, 95% CI = [.12, 33]), but insignificant for women (b = –0.06, p = .528, 95% CI = [–.23, .12]). Then, aligned with our hypothesis, FSOP was positively related to adjustment for both men (b = 0.31, p < .001, 95% CI = [.23, .38]) and women (b = 0.55, p < .001, 95% CI = [.44, 66]), although these perceptions benefited women more than men.

Figure 3. Relationship between organizational cultural intelligence (OCQ) and adjustment as moderated by sex in Study 2.

Figure 4. Relationship between family-supportive organizational perceptions (FSOP) and adjustment as moderated by sex in Study 2.

As expected and summarized in , adjustment was significantly and positively related to organizational commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness. That is, the moderated mediation results confirmed the pattern observed in the two-way interactions summarized above (see ). Specifically, the indirect effects of OCQ through adjustment were significant and positive for men on commitment (b = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.04]), career satisfaction (b = 0.09, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.14]), and embeddedness (b = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.05]). In contrast, the indirect effects of OCQ were insignificant for women on commitment (b = –0.01, 95% CI = [–0.03, 0.02]), career satisfaction (b = –0.02, 95% CI = [–0.10, 0.05]), and embeddedness (b = –0.01, 95% CI = [–0.03, 0.02]). Though the indices of moderated mediation (IMM) were significant for commitment (IMM = –0.03, 95% CI = [–0.06, –0.005]), career satisfaction (IMM = –0.11, 95% CI = [–0.21, –0.02]), and embeddedness (IMM = –0.03, 95% CI = [–0.07, –0.01]), the pattern of results was opposite from what was predicted in H2b, H3a, and H4a.

Confirming our predictions regarding FSOP, however, the indirect results showed that these support perceptions were positively related to commitment (b = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.11]), career satisfaction (b = 0.27, 95% CI = [0.19, 0.38]), and embeddedness (b = 0.09, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.12]) through adjustment for women expatriates. Though weaker, the indirect effects of FSOP for men also positively predicted commitment (b = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.06]), career satisfaction (b = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.22]), and embeddedness (b = 0.05, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.07]). As with OCQ, the indices of moderated mediation were significant for commitment (IMM = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.06]), career satisfaction (IMM = 0.12, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.21]), and embeddedness (IMM = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07]). Together, these results fully support our hypotheses related to FSOP (i.e. H2c, H3b, H4b).

General discussion

Given the global importance of expatriates and the costs associated with managing these human resources (Hechanova, Beehr, & Christiansen, Citation2003), it is crucial that scholars and practitioners understand how organizations can design their HRM systems in strategic ways to help them attract and retain these valuable employees. In particular, we argue that efforts to help increase the number of women expatriates will help organizations win the war on talent (Tung, Citation2016) given the projected future shortages of expatriates (Tung & Varma, Citation2008). In the present study, we develop and test a model that focuses on the types of organizational support that can augment adjustment and longevity attitudes of women expatriates. Specifically, we suggest that organizations should consider how women expatriates’ experiences differ from men's to develop and maintain HRM systems that are targeted to their needs and are, therefore, truly strategic.

Our results over two field studies reveal that women do, indeed, benefit from different types of organizational support than men and that this support can have an appreciable impact on the longevity outcomes of affective commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness. First, Study 1 examined the extent to which POS and sex interact to predict changes in adjustment over time, and, subsequently, affective commitment. Although general organizational support was largely ineffective for both men and women, differential effects did emerge. Though insignificant, we found that women expatriates working in organizations with high than low levels of POS showed increased time-lagged adjustment and commitment.

Contrary to our expectations, however, men demonstrated the opposite relationship. Men working in high-POS firms experienced lower (yet still insignificant) time-lagged adjustment and commitment than those working in low-POS firms. Although counterintuitive, we suggest that perhaps this may be initial evidence of what has been termed ‘the hangover effect’ in prior longitudinal studies of expatriate adjustment (Zhu et al., Citation2016). It could be that high levels of support help to aid expatriate men early on, but then they experience sharper declines in adjustment after the honeymoon has passed.

Building on our initial evidence of sex differences in the effects of organizational support, Study 2 examined more targeted types of support and a greater variety of longevity attitudes with more statistical power. These findings revealed that sex significantly interacted with both OCQ and FSOP to predict adjustment, which was then linked to the longevity attitudes of affective commitment, career satisfaction, and community embeddedness. Contrary to predictions, the effects of OCQ were positive for men but insignificant for women. As employee perceptions of OCQ increase, male expatriates experience higher adjustment and subsequent commitment, career satisfaction, and embeddedness.

One reason that this may occur is due to a sudden status drop. Although in their home countries men may enjoy the privilege of being seen as the normative majority, upon moving abroad they may find themselves faced with a minority status for perhaps the first time. Suddenly being thrust into a situation where they are culturally (and sometimes visibly) different from others may result in an identity shift (Volpone, Marquardt, Casper, & Avery, Citation2018). This newfound ‘other’ status may present a psychological challenge that makes it more difficult for men to adjust than women, who have more experience in both heightened visibility and marginalization (Kanter, Citation1977). Indeed, some studies have demonstrated that women’s affiliative personality traits and conversation skills can sometimes be leveraged into better cross-cultural adjustment (Caligiuri & Lazarova, Citation2002; Cole & McNulty, Citation2011; Tung, Citation2004). Although these speculations should be empirically tested, an unexpected benefit of our findings is that we uncovered the support types that are beneficial for both women and men, further augmenting the strategic potential of targeted support.

Finally, consistent with our hypotheses, women expatriates benefited more than men from high-FSOP. As such, the type of support that is targeted most narrowly at women expatriates (i.e. FSOP) was the only one to significantly increase adjustment and longevity attitudes for women. Women face more barriers to expatriation than men (Altman & Shortland, Citation2008; Shortland, Citation2018b), with institutional discrimination and a desire to maximize both work and family goals being chief among them. We suggest that the provision of FSOP can help to alleviate these burdens most effectively by (a) counterbalancing discrimination by making women’s needs visible and (b) ensuring that expatriate roles do not sacrifice familial happiness and stability, leading to better adjustment. In return for this support and validation, women repay the organization with greater commitment and enjoy higher career satisfaction and community embeddedness.

Theoretical implications

Theoretically, our study extends SHRM theory by showing that organizations can strategically retain and attract a broader range of talent by supporting expatriates in ways that target their unique needs. Prior studies had yet to examine both general and targeted types of support that organizations can provide expatriates to strategically retain them as a result of heightened adjustment. This builds on current findings in the SHRM literature that have primarily focused on targeted recruitment (Avery & McKay, Citation2006), which has shown that minority group members not only respond positively to diversity messages during recruitment, but also seek out information on diversity practices when making job choice decisions. Just as targeted recruitment involves advertising for jobs using tailored messages aimed at particular labor market segments (e.g. Avery & McKay, Citation2006; Newman & Lyon, Citation2009), targeted retention (e.g. policies fostering FSOP) can engender positive impressions of the organization as supporting members of the targeted group (i.e. women expatriates).

Moreover, despite some consensus on the importance of POS for women expatriates (Shen & Jiang, Citation2015; Varma & Russell, Citation2016), little empirical work has determined which types of support can best help women and men adjust and form positive attitudes in international assignments. The results of the present study add to our collective understanding of how we can better support expatriates while encouraging a healthy level of sex diversity in overseas assignments. Specifically, our findings support the work of prior scholars who have noted that targeted support is needed for men and women expatriates (e.g. Caligiuri & Lazarova, Citation2002; Fischlmayr & Kollinger, Citation2010; Salamin & Davoine, Citation2015). In light of the marginal (i.e. POS) and contrary (i.e. OCQ) results for some types of support, however, we suggest that organizations and employees might benefit most by narrowly focusing on FSOP when attempting to augment the number of women expatriates in particular. It is critical that organizations act on these findings in light of recent discoveries that expatriate women are not being sufficiently supported by their companies when pursuing global careers (Fischlmayr & Kollinger, Citation2010). Importantly, we found that male expatriates were also positively impacted by FSOP perceptions (if to a lesser degree), further underscoring the strategic role of offering this type of support to help organizations meet SHRM objectives.

Practical implications

First, our work utilized SHRM theory to suggest that HR cannot be truly viable in the long term unless organizations devise ways to meet the unique needs of all employees making up their expatriate talent pool. Specifically, our results show that to design HRM systems that are truly strategic, organizations need to consider sex and potentially other individual differences when developing programs to support expatriates. Specifically, women in particular are an underutilized resource in achieving strategic HR staffing goals (Salamin & Hanappi, Citation2014), and much needs to be done to retain greater numbers given that they have demonstrated equal effectiveness in performance (e.g. Tung, Citation2004). Our study joins a limited number of others (e.g. Shortland, Citation2016) highlighting things organizations can do to enhance the attitudes and embeddedness of women expatriates. Relatedly, Hutchings et al., (Citation2012) reported that women expatriates often cited teleworking, cross-cultural exchanges, and long-term career planning as a few examples of the types of support they desired. One contribution of our study is that we are able to empirically show which of these facets of support are most likely to yield attitudinal rewards across different types of women expatriates.

Another practical implication of our findings is that HR managers should work to create these targeted support systems for employees given the positive effects associated with FSOP and OCQ identified by this study. Our findings add further support for Shortland’s (Citation2018a, p. 60) contention that although ‘HR policy typically does not differentiate between men and women in terms of international rewards, benefits and support services on assignment’, organizations would do well to assist women with known challenges such as childcare, education assistance, and support to maintain family ties. Prior research has also noted that family-friendly benefits offered by the organization (Hammer et al., Citation2005), benefit usage, and family-supportive supervisors (Kossek et al., Citation2011) can increase family-supportive perceptions. As such, we recommend that managers implement policies and help build supportive working environment to ensure that women expatriates adjust to international assignments, thereby contributing to a sustainable international talent management system.

A final practical implication stems from the findings related to OCQ in the UAE culture. In the UAE, men and women are still discouraged from interacting socially (Harrison & Michailova, Citation2012). Training women to better communicate with the host culture may not be useful if they are barred from exercising these skills. In fact, Harrison and Michailova, (Citation2012) reported that Western women expatriates in the UAE actually viewed lengthy cross-cultural training as unhelpful. Similarly, Shortland (Citation2016) noted that only 44.1% of her women expatriate respondents listed gaining cultural understanding as a ‘very important’ factor leading them to accept an expatriate assignment. This signals that perhaps the cultural concerns facing women are not as pressing as their family responsibilities.

Limitations and future research

The implications of our studies must be tempered by their limitations. First, replication is needed to further confirm the impact of OCQ and FSOP on time-lagged adjustment. Unlike in Study 1, we were unable to collect longitudinal data in Study 2, leaving us unable to definitively determine causality. Second, although we examined the role of sex, there are several other individual differences that may play a role in determining which expatriates benefit most from general and targeted types of support. In light of meta-analytic evidence that extraversion is the most important personality trait in predicting expatriate adjustment (Harari, Reaves, Beane, Laginess, & Viswesvaran, Citation2018), for example, it could be interesting to examine whether expatriate targeted forms of support (e.g. OCQ) could help to bolster the adjustment and longevity attitudes of introverts who may struggle to form bonds with host country nationals. Accordingly, we encourage more research highlighting the types of expatriates that should be targeted with various forms of organizational support.

Third, we collected Study 2 data in a single geographic location, the UAE. Although Study 1 utilized more generalizable data (expatriates across 34 countries), we acknowledge the need for more diverse research on the expatriate experience in general. For instance, Dabic, González-Loureiro, and Harvey (Citation2015) have suggested that researchers widen their geographic scope. Though our study makes initial efforts to answer this call, future research is needed to develop the impact of this research model in additional geographic regions of the world and tests the effects in different industries. For example, we might expect that our findings would be even more pronounced in organizations with the lowest levels of women expatriates, such as in the oil and gas or mining industries (Shortland, Citation2018b).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The response rate of 56% represents the percentage of participant from the T1 survey that also completed the T2 survey. We were unable to calculate a response rate for the T1 survey because we are not aware of how many individuals in total saw our online recruitment post and decided not to participate. To fully explore and ensure that there are no differences between the respondents in T1 and T2, we conducted a series of t-tests and found that there are no systematic differences between participants who responded to the T1 and T2 survey. Specifically, we do not find statistical differences between participants in terms of sex (F = 1.56, p = .41), level of education (F = 2.17, p = .09), or time in country (F = 0.30, p = .67).

2 Although our relatively small sample size limited the power available, we also tested a more stringent version of this model including the demographic control variables of age, marital status, and the number of children. In this model, the interaction between POS and sex on adjustment approached significance (b = 0.17, p = .06) and the pattern of relationships was the same, with men demonstrating a negative indirect relationship through adjustment (b = –0.04, 95% CI = [–0.11, 0.02]) and women demonstrating a positive one (b = 0.07, 95% CI = [–0.05, 0.18]).

3 Some readers may also question whether or not other family-status variables may have a similar moderating effect on the relationships between support and adjustment. We tested the effects of having children and being married and although the pattern of effects was generally as expected (i.e. women with children or spouses generally benefitted more from support), the interactions were largely insignificant, leading us to the decision to not include them as control variables or additional moderators in the main analyses.

4 We also tested each of these models using covariates (i.e. the other type of organizational support, age, expatriate tenure, marital status, and the number of children in light of theoretical links to FSOP and expatriate longevity outcomes) (e.g., Chen, Liu, & Portnoy, Citation2012). Results showed that OCQ significantly predicted adjustment (b = 0.24, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.34]) and the indices of moderated mediation (IMM) were significant and similar in magnitude for commitment (IMM = –0.03, 95% CI = [–0.06, –0.01]), career satisfaction (IMM = –0.15, 95% CI = [–0.26, –0.04]), and embeddedness (IMM = –0.05, 95% CI = [–0.09, –0.01]). Similarly, FSOP still significantly predicted adjustment (b = 0.31, 95% CI = [0.23, 0.38]). The indices of moderated mediation were significant and similar in magnitude for commitment (IMM = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.05]), career satisfaction (IMM = 0.11, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.19]), and embeddedness (IMM = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.06]). As such, we view the effects of these two types of support as robust and distinct from one another.

References

- Adler, N. (1987). Pacific basin managers: A Gaijin, not a woman. Human Resource Management, 26(2), 169–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930260205

- Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 414–435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774

- Altman, Y., & Shortland, S. (2008). Women and international assignments: Taking stock – a 25-year review. Human Resource Management, 47(2), 199–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20208

- Andresen, M. (2015). What determines expatriates’ performance while abroad? The role of job embeddedness. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 3(1), 62–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-06-2014-0015

- Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, A. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 335–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00082.x

- Anseel, F., Lievens, F., Schollaert, E., & Choragwicka, B. (2010). Response rates in organizational science, 1995–2008: A meta-analytic review and guidelines for survey researchers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 335–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9157-6

- Avery, D. R., & McKay, P. F. (2006). Target practice: An organizational impression management approach to attracting minority and female job applicants. Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 157–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00807.x

- Bader, B., Stoermer, S., Bader, A. K., & Schuster, T. (2018). Institutional discrimination of women and workplace harassment of female expatriates: Evidence from 25 host countries. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 6(1), 40–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-06-2017-0022

- Becker, B., & Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of human resource management on organizational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 779–801. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/256712

- Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P., Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Luk, D. M. (2005). Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment: Meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 257–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.16928400

- Black, J. S., & Gregersen, H. B. (1991). When Yankee comes home: Factors related to expatriate and spouse repatriation adjustment. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(4), 671–694. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490319

- Black, J. S., & Stephens, G. K. (1989). The influence of the spouse on American expatriate adjustment and intent to stay in Pacific Rim overseas assignments. Journal of Management, 15(4), 529–544. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638901500403

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. The Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/20159029

- Brookfield Global Relocation Services. (2016). 2016 Global Mobility Trends Survey. Chicago, IL: Brookfield Global Relocation Services.

- Caligiuri, P., & Bonache, J. (2016). Evolving and enduring challenges in global mobility. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 127–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.10.001

- Caligiuri, P., & Lazarova, M. (2002). A model for the influence of social interaction and social support on female expatriates' cross-cultural adjustment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(5), 761–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190210125903

- Cao, L., Hirschi, A., & Deller, J. (2014). Perceived organizational support and intention to stay in host countries among self-initiated expatriates: The role of career satisfaction and networks. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(14), 2013–2032. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.870290

- CARTUS. (2018). 2018 Trends in global relocation biggest challenges survey. Retrieved from https://www.cartus.com/en/relocation/resource/biggest-challenges-survey/

- Cateora, P. R., & Graham, J. L. (2005). International marketing (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Chen, X.-P., Liu, D., & Portnoy, R. (2012). A multilevel investigation of motivational cultural intelligence, organizational diversity climate, and cultural sales: Evidence from U.S. real estate firms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 93–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024697

- Chen, Y., & Shaffer, M. (2017). The influences of perceived organizational support and motivation on self-initiated expatriates’ organizational and community embeddedness. Journal of World Business, 52(2), 197–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2016.12.001

- Cole, N. D. (2011). Managing global talent: Solving the spousal adjustment problem. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(7), 1504–1530. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561963

- Cole, N., & McNulty, Y. (2011). Why do female expatriates ‘fit-in’ better than males? Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 18(2), 144–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13527601111125996

- Crompton, R., & Harris, F. (1998). Explaining women’s employment patterns: Orientations to work revisited. British Journal of Sociology, 49(1), 118–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/591266

- Dabic, M., González-Loureiro, M., & Harvey, M. (2015). Evolving research on expatriates: What is ‘known’ after four decades (1970–2012). The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(3), 316–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.845238

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.71.3.500

- Fischlmayr, I., & Kollinger, I. (2010). Work-life balance – a neglected issue among Austrian female expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(4), 455–487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585191003611978

- Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 64–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/256352

- Gregersen, H. B., & Black, J. S. (1990). A multifaceted approach to expatriate retention in international assignments. Group and Organization Studies, 15(4), 461–485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/105960119001500409

- Hammer, L. B., Neal, M. B., Newsom, J. T., Brockwood, K. J., & Colton, C. L. (2005). A longitudinal study of the effects of dual-earner couples' utilization of family-friendly workplace supports on work and family outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 799–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.799

- Harari, M. B., Reaves, A. C., Beane, D. A., Laginess, A. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2018). Personality and expatriate adjustment: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(3), 486–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12215

- Harris, H. (2002). Think international manager, think male: Why are women not selected for international management assignments? Thunderbird International Business Review, 44(2), 175–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.10010

- Harrison, E. C., & Michailova, S. (2012). Working in the Middle East: Western female expatriates’ experiences in the United Arab Emirates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(4), 625–644. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.610970

- Haslberger, A., Brewster, C., & Hippler, T. (2013). The dimensions of expatriate adjustment. Human Resource Management, 52(3), 333–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21531

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hechanova, R., Beehr, T. A., & Christiansen, N. D. (2003). Antecedents and consequences of employees’ adjustment to overseas assignment: A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 52(2), 213–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00132

- Heslin, P. A. (2005). Conceptualizing and evaluating career success. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(2), 113–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.270

- Hutchings, K., Lirio, P., & Metcalfe, B. D. (2012). Gender, globalisation and development: A re-evaluation of the nature of women’s global work. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(9), 1763–1787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.610336

- Jackson, S. E., Schuler, R. S., & Jiang, K. (2014). An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 1–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.872335

- Joo, B. K., & Park, S. (2010). Career satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention: The effects of goal orientation, organizational learning culture and developmental feedback. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31(6), 482–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731011069999

- Kang, H., & Shen, J. (forthcoming). Antecedents and consequences of host-country nationals’ attitudes and behaviors toward expatriates: What we do and do not know. Human Resource Management Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.001

- Känsala, M., Mäkelä, L., & Suutari, V. (2015). Career coordination strategies among dual career expatriate couples. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26, 2187–2210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.985327

- Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965–990. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/226425

- Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta‐analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family‐specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 289–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x

- Kraimer, M. L., Bolino, M. C., & Mead, B. (2016). Themes in expatriate and repatriate research over four decades: What do we know and what do we still need to learn? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 83–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062437

- Lauring, J., & Selmer, J. (2009). Expatriate compound living: An ethnographic field study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(7), 1451–1467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190902983215

- Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Sablynski, C. J., Burton, J. P., & Holtom, B. C. (2004). The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 711–722. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/20159613

- Linehan, M., & Scullion, H. (2001). Selection, training, and development for female international executives. Career Development International, 6(6), 318–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005987

- Linehan, M., & Walsh, J. S. (1999). Mentoring relationships and the female managerial career. Career Development International, 4(7), 348–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13620439910295718

- Meyer, J., Stanley, D., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/3069391

- Moon, T. (2010). Organizational cultural intelligence: Dynamic capability perspective. Group & Organization Management, 35(4), 456–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601110378295

- Newman, D., & Lyon, J. (2009). Recruitment efforts to reduce adverse impact: Targeted recruiting for personality, cognitive ability, and diversity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 298–317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013472

- ORC Worldwide. (2007). Survey of International Localization Policies and Practices.

- Peterson, R. B., Sargent, J., Napier, N. K., & Shim, W. S. (1996). Corporate expatriate HRM policies, internationalization, and performance in the world's largest MNCs. MIR: Management International Review, 36, 215–230.

- Ployhart, R. E., & Moliterno, T. P. (2011). Emergence of the human capital resource: A multilevel model. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 127–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0318

- Puchmüller, K., & Fischlmayr, I. (2017). Support for female international business travelers in dual-career families. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 5(1), 22–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-05-2016-0023

- Ren, H., Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., Fu, C., & Fodchuk, K. M. (2014). Reactive adjustment or proactive embedding? Multistudy, multiwave evidence for dual pathways to expatriate retention. Personnel Psychology, 67(1), 203–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12034

- Reskin, B. F., & Roos, P. A. (1990). Job queues, gender queues: Explaining women’s inroads into male occupations. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825–836. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.5.825

- Salamin, X., & Davoine, E. (2015). International adjustment of female vs male business expatriates: A replication study in Switzerland. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 3(2), 183–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-12-2014-0055

- Salamin, X., & Hanappi, D. (2014). Women and international assignments: A systematic literature review exploring textual data by correspondence analysis. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 2(3), 343–374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-09-2013-0058

- Shen, J., & Jiang, F. (2015). Factors influencing Chinese female expatriates’ performance in international assignments. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(3), 299–315.

- Shortland, S. (2016). The purpose of expatriation: Why women undertake international assignments. Human Resource Management, 55(4), 655–678. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21686

- Shortland, S. (2018a). Female expatriates’ motivations and challenges: The case of oil and gas. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 33(1), 50–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2017-0021

- Shortland, S. (2018b). Women’s participation in organisationally assigned expatriation: An assignment type effect. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2018, 1–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1510849

- Stahl, G. K., Chua, C. H., Caligiuri, P., Cerdin, J.-L., & Taniguchi, M. (2009). Predictors of turnover intentions in learning-driven and demand-driven international assignments: The role of repatriation concerns, satisfaction with company support, and perceived career advancement opportunities. Human Resource Management, 48(1), 89–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20268

- Stroh, L. K., Varma, A., & Valy-Durbin, S. J. (2000). Why are women left at home: Are they unwilling to go on international assignments? Journal of World Business, 35(3), 241–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(00)00037-7

- Tung, R. L. (2004). Female expatriates: A model for global leaders?. Organizational Dynamics, 33(3), 243–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.06.002

- Tung, R. L. (2016). New perspectives on human resource management in a global context. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 142–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.10.004

- Tung, R. L., & Varma, A. (2008). Expatriate selection and evaluation. In P. B. Smith, M. F. Peterson, & D. C. Thomas (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural management research (pp.367–377). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- van der Laken, P., van Engen, M., van Veldhoven, M., & Paauwe, J. (2016). Expatriate support and success: A systematic review. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 4(4), 408–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-11-2015-0057

- van Driel, M., & Gabrenya, W. K. (2013). Organizational cross-cultural competence: Approaches to measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(6), 874–899. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022112466944

- Varma, A., & Russell, L. (2016). Women and expatriate assignments: Exploring the role of perceived organizational support. Employee Relations, 38(2), 200–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2015-0019

- Volpone, S. D., Marquardt, D. J., Casper, W. J., & Avery, D. R. (2018). Minimizing cross-cultural maladaptation: How minority status facilitates change in international acculturation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(3), 249–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000273

- Welsh, S. & Kersten, C. (2014). Where are women in the expatriate workforce? Leveraging female talent to increase global competitiveness. SHRM Online Global HR page. Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/global-hr/pages/women-expatriate-workforce.aspx

- Wright, P. M., & McMahan, G. C. (1992). Theoretical perspectives for strategic human resource management. Journal of Management, 18(2), 295–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639201800205

- Wu, P. C., & Ang, S. H. (2011). The impact of expatriate supporting practices and cultural intelligence on cross-cultural adjustment and performance of expatriates in Singapore. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(13), 2683–2702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.599956

- Yitman, I. (2013). Organizational cultural intelligence: A competitive capability for strategic alliances in the international construction industry. Project Management Journal, 44, 5–25.

- Zhu, J., Wanberg, C. R., Harrison, D. A., & Diehn, E. W. (2016). Ups and downs of the expatriate experience? Understanding work adjustment trajectories and career outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(4), 549–568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000073