abstract

Although a contextual perspective in HRM research has been strongly advocated, empirical evidence on how context shapes HRM is still lacking. This study explored HRM philosophies and policies in Dutch semi-autonomous government agencies and how they are shaped. These agencies were given considerable autonomy by central government with regard to their HRM philosophies and policies in order to make more effective use of their human capital. Based on our findings from thirty semi-structured interviews with HRM managers, we identified that (a) facilitation philosophies are dominant, while accumulation philosophies are less present and utilization philosophies nonexistent; (b) mixed philosophies are present in some cases; (c) ability- and motivation-enhancing policies are dominant, while opportunity-enhancing policies are less present; (d) similarities in HRM are strongly shaped by external factors; and that (e) differences in HRM are strongly shaped by internal factors.

Since the 1980s, scholars have argued that HRM is ‘inherently contextualized’ (Jackson, Schuler, & Jiang, Citation2014). Early HRM models acknowledged that it is too simplistic to assume that choices regarding HRM are made in a vacuum (Beer, Spector, Mills, & Walton, Citation1984; Fombrun, Tichy, & Devanna, Citation1984). While scholars have advocated the adoption of contextual perspectives (Beer, Boselie, & Brewster, Citation2015; Paauwe, Citation2004), studies testing universalistic predictions remain dominant in the HRM literature (Guest, Citation2011; Jackson et al., Citation2014). Although there are a few studies that examined the influence of context on HRM (e.g. Farndale and Paauwe, Citation2007), most studies have ‘ignored the embedded and contextualized nature of HRM’ (Jackson et al., Citation2014, p. 31). In order to advance our knowledge of how context shapes choices organizations make regarding HRM, additional studies are needed.

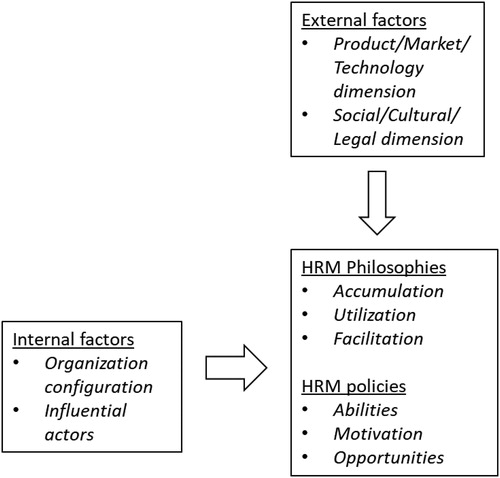

In this respect, studying the influence of context on an organization’s HRM philosophies and policies is a useful approach to adopt in scholarly work, as these concepts are more reflective of an organization’s choices regarding HRM, as opposed to the often-researched HRM practices (Lepak, Marrone, & Takeuchi, Citation2004). HRM philosophies and policies, defined as the general guiding principles and specific programs of the management of personnel, have been positioned as essential and successive components of the HRM architecture (Becker & Gerhart, Citation1996; Kellner, Townsend, Wilkinson, Greenfield, & Lawrence, Citation2016). As components reflecting organizational choices, an organization’s HRM philosophy and policies are expected to be shaped by the organization’s environment, distinguished by the external and internal context. Therefore, to gain a better insight into which and when certain philosophies and policies are used, it is important to study a group of organizations that vary in some respects, but that also share parts of their organizational environment. This approach enables scholars to examine the impact of both broad and organization-specific contextual factors, providing a more complete picture of how HRM is shaped.

Against the background of the above-mentioned line of reasoning, a study among semi-autonomous government agencies – hereafter called agencies – provides an interesting case. On the one hand, agencies represent a specific group of public organizations, since they are structurally disaggregated from central government while remaining under the formal control of parent ministries (Verhoest, Van Thiel, Bouckaert, & Laegreid, Citation2012). Previous findings on HRM autonomy in these agencies indicate that they are partly affected by similar contextual factors, especially those relating to a political context (Bach, Citation2014; Verhoest, Roness, Verschuere, Rubecksen, & MacCarthaigh, Citation2010). On the other hand, agencies vary substantially on various aspects, such as organizational task, legal personality and parent ministry. Furthermore, this variation is coupled with the fact that agencies are given considerable formal autonomy, inspired by managerialism, to make individual choices regarding HRM philosophies and policies (James & Van Thiel, Citation2011; Rodwell & Teo, Citation2008; Truss, Citation2008). Thus, agencies partly share an organizational environment but also vary on several aspects, which provides a valuable case to examine how context shapes choices regarding HRM.

Following from the aforesaid, the aim of this study is to answer the following research question: What are the similarities and differences in HRM philosophies and policies among semi-autonomous agencies, and what are important external and internal factors? To answer this question, data have been collected from 30 semi-structured interviews at 30 agencies in the Netherlands, a country with a strong tradition of agencies (Yesilkagit & Van Thiel, Citation2012). Building upon previous research (Van Thiel, Citation2012), we have gathered data at the three types of agencies that have been identified based on legal identity and managerial autonomy.

By answering our research question, this study contributes to HRM and public administration literature. First, although scholars have repeatedly argued that HRM is contextualized (Beer et al., Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2014; Paauwe, Citation2004), empirical evidence is still lacking on how context shapes choices regarding HRM. In particular, this study examines how HRM is shaped and which contextual factors play a role under which conditions. Second, this study is one of the few that focuses on HRM philosophies as a separate component. Although underrepresented in the literature, HRM philosophies play an essential role in how organizations manage their employees (Lepak et al., Citation2004). Third, our focus on both philosophies and policies allows us to explore whether both components are shaped similarly or differently. Although policies are often represented as the logical outcomes of the HRM philosophy (Lepak, Liao, Chung, & Harden, Citation2006), in many occasions the implementation process is not perfect and discrepancies between components may be present (Wright and Nishii, Citation2007). We note that discrepancies may not only reflect problems in the implementation process itself but may also result into negative effects on employees since mixed messages are perceived (Kellner et al., Citation2016). Finally, this study contributes to the literature on HRM in agencies by focusing on their actual choices. This focus on what HRM in agencies actually entails adds to the public administration literature that almost exclusively examined HRM autonomy in these agencies (e.g. Bach, Citation2014; Verhoest, Peters, Bouckaert, & Verschuere, Citation2004; Wynen, Verhoest, & Rubecksen, Citation2014).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, the literature regarding HRM philosophies and policies is discussed as well as theory on how they are shaped by external and internal factors. Next, the conceptual framework that is used to analyze the data is presented. This is followed by an elaboration on our methodology and findings. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings for theory and practice, reflect on the limitations of our study and offer suggestions for future research.

Theory

HRM philosophies and policies

HRM philosophies

HRM philosophies – also referred to as guiding principles (Becker & Gerhart, Citation1996; Wright, Citation1998) – are considered the highest level in the HRM architecture (Kellner et al., Citation2016). These terms refer to a general overarching philosophy that guides the design of HRM policies and is developed and shared by management (Lepak et al., Citation2004; Posthuma, Campion, Masimova, & Campion, Citation2013). In this respect, Kellner et al. (Citation2016, p. 1244) argued that ‘the HRM philosophy provides an important framework for [.] the HRM system’. Although research on HRM philosophies is scarce, findings from studies so far indicate the pivotal role of HRM philosophies in the shaping of HRM policies (e.g. Bin Othman, Citation1996; Kelliher & Perrett, Citation2001; Monks et al., Citation2013).

Schuler (Citation1989) classified three types of philosophies that reflect the way an organization treats and manages its people: accumulation, utilization and facilitation. An accumulation philosophy emphasizes maximum involvement and focuses on attracting people with great potential and developing them over time, consistent with the organization’s needs. Organizations with a utilization philosophy seek to achieve high efficiency for HRs by mainly focusing on technical skills. People are mostly employed on a short-term basis and matched with the organization’s short-term needs. Finally, a facilitation philosophy reflects a focus on the generation of knowledge and facilitating knowledge creation. Emphasis is put on self-motivated employees, who are encouraged to develop those abilities and skills that they deem to be important. The focus that is put on employee responsibility illustrates the role of the organization as a facilitator, which is much more the case than in an accumulation or utilization philosophy.

HRM policies

In contrast to HRM philosophies, HRM policies have gained more attention in the literature (Jackson et al., Citation2014). As noted by Lepak et al. (Citation2006, p. 211), HRM policies ‘reflect an employee-focused program that influences the choice of HRM practices’. HRM policies are presented as specific components representing the organization’s HRM architecture and should, in a well-aligned HRM architecture, follow the principles of the HRM philosophy (Posthuma et al., Citation2013).

In line with the Ability-Motivation-Opportunity (AMO) model introduced by Appelbaum, Bailey, Berg, and Kalleberg (Citation2000), many studies have classified HRM policies into three distinct HRM policy domains based on their goal to increase the abilities, motivation, or opportunities of employees to perform (e.g. Boselie, Citation2010; Jiang et al., Citation2012; Lepak et al., Citation2006; Subramony, Citation2009). In this respect, policies that aim to increase the knowledge, skills and abilities of personnel, such as training, recruitment and selection, are classified into the abilities domain. Policies that aim to increase the motivation of employees, such as performance management and incentives, are classified into the motivation domain. Finally, policies that aim to provide employees opportunities to contribute, such as direct participation and teamwork, are classified in the opportunities domain.

Scholars have argued that a focus on HRM policies provides advantages over a focus on HRM practices – defined as ‘specific organizational actions designed to achieve specific outcomes’ (p. 221) – when trying to distinguish between organizations with regard to HRM (Lepak et al., Citation2004). More specifically, concepts of equifinality and multifinality make it difficult to compare organizations based on their HRM practices. After all, to realize a certain HRM policy, a multitude of HRM practices can be used. For example, an organization that promotes employee development can apply HRM practices such as job-specific training, interpersonal training, or team building. In a similar vein, selection policies can be implemented through realistic job interviews, internal promotion, or ability tests. So far, this is not different from multiple specific HRM policies realizing a particular HRM domain. However, the same HRM practices can also be used for different HRM policies. In other words, a single HRM policy can include multiple HRM practices and a single HRM practice can be included in multiple HRM policies. For example, job-specific training can be used for employee development as well as for workplace safety.

Contextualized HRM philosophies and policies

As previously noted by scholars, decisions concerning HRM are strongly influenced by an organization’s context (Jackson et al., Citation2014; Verhoest et al., Citation2010). In this respect, the Contextually-Based HR Theory (CBHRT) states that context influences the adoption of HRM philosophies and policies across organizations in a specific population (Paauwe, Citation2004). More specifically, it builds on new institutionalism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983) and the Resource-Based View (RBV; Barney, Citation1991) to provide a framework explaining the influence of external and internal factors on organizational decisions regarding HRM. In particular, the CBHRT states that external factors from a Social, Cultural, and Legal (SCL) dimension and a Product, Market, and Technology (PMT) dimension create a need to achieve legitimacy within organizations, leading to the adoption of similar philosophies and policies. In contrast, internal factors associated with the configuration of the organization, such as structure and staff composition, and strategic choices made by top management result into differentiation among organizations.

As mentioned before, we argue that agencies belong to one specific population. Agencies are often viewed as more ‘private’ than central government and more ‘public’ than businesses. The freedom to make choices regarding HRM makes agencies distinctive from departments in central government (Dunleavy, Margetts, Bastow, & Tinkler, Citation2005). Furthermore, they are often single-purpose organizations that are less hierarchically organized and face less political influence on their operations than central government. However, agencies are also distinctive from private organizations because their funding is often separately assigned from their tasks, and they are bound by stricter legislature and are influenced by their parent ministry (Kickert, Citation2001). For example, the social benefits agency in the Netherlands deals with a considerable amount of government regulation, but is funded by taxes and premiums. Thus, given the arguments that agencies are distinctive from central government and businesses, it can be expected that they are influenced by a particular context. However, up till now, it is unclear how this context affects decisions of HRM philosophies and policies.

On the one hand, based on new institutionalism, it can be expected that external institutional and competitive pressures – which the CBHRT refers to as factors from the SCL and PMT dimensions (Paauwe, Citation2004) — result in similar philosophies and policies across agencies (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). Institutional pressures, differentiated between coercive, normative and mimetic pressures, are related to an organization’s need to achieve legitimacy within its environment. These pressures may stem from external factors such as legislation, government, labor unions, but also from social and cultural norms and values (Paauwe & Boselie, Citation2003). For example, an agency’s decisions regarding HRM could be strongly shaped by coercive pressures residing from beliefs of central government on how public organizations should act or operate, even if they are not legally obliged to follow government policy.

In addition to institutional pressures, competitive pressures, related to an economic rationality expressed in terms as efficiency, effectiveness and flexibility, may also be reflected in external factors that shape decisions regarding HRM. Although these pressures do not seem to be present in agencies, due to a lack of real competition, introducing business-like conditions has been a vital part of governments when creating agencies (Verhoest et al., Citation2012). For example, agencies have been confronted with the introduction of performance indicators, result-based steering and competitive incentives over the years. As such, both institutional and competitive pressures are external institutional pressures that can affect decision-making in agencies in such a way that similar philosophies and policies are adopted.

On the other hand, differentiation can result from choices regarding HRM shaped by internal institutional factors (Paauwe, Citation2004). These influences are found in the organizational configuration or heritage. Past choices in combination with organizational characteristics, such as the organizational structure, staff composition and organizational culture, are important factors shaping HRM. This process, also referred to as path dependency (Barney, Citation1995), is unique for each organization, leading to the adoption of different HRM philosophies and policies.

Furthermore, based on the RBV, it can be expected that differentiation in HRM philosophies and policies occurs because agencies cultivate their human capital differently to create strategic advantages (Barney, Citation1991; Paauwe & Boselie, Citation2003). Although the RBV is mainly applied to explain competitive advantage in businesses, we consider it to be applicable to the context of agencies as well. Since the rise of managerialism in the public sector, efficiency and cost-reduction have increasingly been emphasized in public service delivery (Alford & Hughes, Citation2008). In combination with the autonomy to make strategic choices, agencies became able to develop their human capital to adhere to these outcomes. Furthermore, as underperforming may result in becoming part of central government or having to deal with structural reforms (Verhoest et al., Citation2012), an internal drive may be created in agencies to justify their existence by creating strategic advantages, thus behaving in a ‘business-like’ manner. Based on these aspects, it could be expected that influential actors within agencies make strategic choices, leading to differentiation among agencies.

Thus, by incorporating the ideas of new institutionalism and the RBV, the CBHRT acknowledges the important role of an organization’s context in shaping HRM. However, this theory cannot explain which philosophies and policies are ultimately adopted, and it remains unknown which factors are strong drivers for similarity or differentiation in the adoption of HRM philosophies and policies. Using the CBHRT (Paauwe, Citation2004), in combination with Schuler’s (Citation1989) typology of HRM philosophies and the three HRM policy domains based on the AMO model (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000), this study explores these questions empirically using the conceptual framework that is displayed in . This framework is used to analyze our empirical findings and to compare agencies.

Method

Research context

Following Van Thiel’s (Citation2012, p. 20) categorization of public organizations, three types of agencies are identified based on their legal personality and formal autonomy.

Type 1 agencies have some degree of managerial autonomy but no legal independence, see for example the Next Steps Agencies in the UK. Type 2 agencies, with legal independence and managerial autonomy, are the most common types of agencies in Europe (e.g. public establishments in Italy and France, Crown Entities in New Zealand, NDPBs in the UK). In general, they have been founded in the 1990s and early 2000s, although some of these agencies have existed much longer, for example in the Nordic countries (Verhoest et al., Citation2012). Type 3 agencies consist of organizations with corporate forms, such as foundations and limited companies. These agencies are established by, or on behalf of, the government that owns part of or all stock/shares.

Over the years, all three types of agencies have been created in the Netherlands, together employing more people than central government (Yesilkagit & Van Thiel, Citation2012). Agentschappen, thirty in total, are Type 1 agencies, performing a variety of public tasks, such as the management of public works and water infrastructure (Rijkswaterstaat) and the payment of student loans (DUO). Furthermore, Zelfstandig bestuursorganen (ZBOs) are Type 2 agencies, which are public bodies established by law or charged with a task by law. There are about 110 ZBOs registered in the formal ZBO register, including some large clusters of ZBOs. Like executive agencies, ZBOs carry out different tasks, ranging from the payment of social benefits (UWV) to the protection of person data (Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens). Finally, state-owned enterprises are Type 3 agencies. In 2015, the Dutch government owned shares of 34 enterprises. Examples of state-owned enterprises are the largest airport of the country (Schiphol) and the operator of the high-voltage energy grid (TenneT).

Research design and sample

Given our research question, this study adopted an exploratory design in which 30 cases were compared using qualitative coding. We adopted a method of diverse case selection, where the goal was to include cases that exemplify the diversity of agencies in the Netherlands (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008). In contrast to the clear distinction based on their legal status, agencies in the Netherlands vary in task, size and parent ministry, independent from their type. Using convenience sampling, we tried to get access to agencies of each type, varying by parent ministry, task and size. In addition to achieving a representative sample of agencies in the Netherlands, achieving thematic saturation was an important goal in our sampling strategy (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, Citation2006).

Between November 2016 and March 2017, data were collected by the first author who conducted 30 semi-structured interviews in Dutch with 36 employees of 30 agencies. Characteristics of our sample are shown in and compared to the population of agencies in the Netherlands. As can be concluded from this table, our sample is fairly representative in terms of type, task and parent ministry. Small agencies are underrepresented, and large agencies are overrepresented in our sample.

Table 1. Characteristics of sample and population.

For reasons of anonymity, the names of the interviewees and agencies have been excluded from the table. Interviews were conducted with representatives who were head of HR within the organizations, although not all held this as their official title. Some were a member of the board of directors, while others reported to a member of the board of directors. Only interviewing a single, or sometimes two, respondent(s) per organization has limitations in providing a complete picture of HRM in the organizations they are representing. Nevertheless, their position as head of HR ensures their knowledge regarding their organization’s intentions toward HRM and the factors that shape these intentions.

Interview and coding procedure

Before each interview, the interviewer briefly explained the goal of the research project, the general subjects to be discussed and the procedure regarding protecting anonymity. Interviews were carried out face-to-face, lasted on average one hour, were tape recorded and fully transcribed verbatim in Dutch. The interview questions explored HRM philosophies, HRM policies as well as both internal and external factors that had an impact on HRM.

To get comprehensive and rich answers, we first derived questions based on our conceptual framework adapted to suit a practitioners’ perspective. Instead of asking interviewees directly what their HRM philosophy was, we asked how they would define HRM, which HRM themes were important in the organization and why, and how HRM policies are adopted. To complement this set of relatively open questions, specific questions related to the conceptual framework were asked later on in the interview. The interviewees were asked to state which HRM policies were emphasized in their organization and which external and internal factors influenced choices regarding HRM.

Using ATLAS.ti, we adopted a coding approach in line with template analysis (King, Citation2004). Template analysis is a flexible technique that involves the use of a list of codes – i.e. the template – that are defined a priori. During the coding process, these initial codes can be modified or more codes can be added if the initial codes are not sufficient to cover the data. As such, this approach allows for a hybrid form of both deductive and inductive coding and is considered suitable to explore a theoretical conceptual framework empirically.

Before the data were analyzed, we created a template of codes in line with our conceptual framework. Thus, codes were created relating to HRM philosophies, HRM policies, external and internal factors. To differentiate between HRM policies from philosophies, we only coded a quote as a policy if it reflected a specific employee-focused program (Lepak et al., Citation2004). In this respect, a term like autonomy is considered as an aspect of the HRM philosophy, because it can be operationalized in a wide range of policies. For example, an organization can strive for autonomy in the hours employees work or in the courses employees follow, or in the benefits employees choose.

After creating the template, we analyzed the data in three cycles, using a combination of open, axial and selective coding (Saldaña, Citation2009). During the first coding cycle, we marked quotations with one of the initial codes from the template. In addition, basic descriptive information of the organizations and interviewees were coded. In the second cycle, we used open coding to further specify the marked quotations from the first cycle. In the final cycle, we used axial coding to identify subthemes among the codes in the second cycle. During each cycle, the initial coding was done by the first author, followed by a discussion between the first and second author on the codes after which adjustments were made. After this coding procedure, we ended up with codes that were deductively derived from the conceptual framework and codes that were inductively derived. In Appendix A, the list of codes in the template, their definitions and examples of codes derived from inductive coding are presented.

Based on a comparison of the 30 individual cases, the results have been categorized in themes that emerged as relevant to the research question during the coding procedure. Whereas the codes from the template illustrated the themes in a broad sense, the codes derived inductively illustrated the themes in a detailed matter. For example, the codes from the template showed that policies pertaining to the abilities and motivation domains are dominant and the inductive codes showed which specific policies were emphasized most. As such, the themes are related to the research question in terms of the similarities and differences in HRM philosophies and policies and how they are shaped by external and internal factors.

Findings

In this section, we discuss our findings according to five themes that have emerged. Based on Schuler’s (Citation1989) typology and the three policy domains, we have identified the dominant philosophy and policy domain for each agency in our sample in . Furthermore, and illustrate which factors are drivers for similarities and differences in philosophies and policies.

Table 2. Number of cases for dominant HRM philosophies and policy domainsTable Footnotea.

Table 3. Internal and external factors influencing HRM philosophies mentioned by interviewees.

Table 4. Internal and external factors influencing HRM policies mentioned by interviewees.

Theme 1: Facilitation philosophy dominant in most agencies

In general, around 80 percent of the agencies in our sample seem to have a clear philosophy in line with Schuler’s typology. That is, based on what the interviewees indicated as the agency’s idea on what guides their HRM system, we could assign one of the three philosophies in 80 percent of the cases. It should be noted however, that no cases were identified that showed a utilization philosophy.

Of the cases with a clear philosophy, our findings indicate that a facilitation philosophy is dominant. That is, 60 percent of the total sample demonstrated the presence of this philosophy. The pivotal role of autonomy and responsibility of the employee is essential in this philosophy:

[.] you have to be able to determine for yourself what the next step is in your development. Autonomy is really important. That patronizing and controlling behavior of managers had to stop. Managers have no clue of what needs to be done, thus employees should make their own plans. (Organization 15)

Besides employee autonomy, interviewees highlighted the importance of both internal and external mobility as well as a high degree of interaction between employees. These aspects emphasize the role of the organization as a facilitator, providing resources that enable employees to independently find opportunities to learn.

Besides the HR department, the interviewees often defined the supervisor as one that facilitates and serves the employee:

The employees are the ones on top [of the pyramid] and the supervisor is mainly there to let the employees do their work as good as possible and support that. (Organization 4)

The remaining cases that showed a clear philosophy demonstrated an accumulation philosophy. Interviewees of these agencies mentioned concepts such as adaptivity, vitality and employability as important employee characteristics to stimulate long-term employment within the organization:

We want that our young employees have a certain career within [organization]. In this aspect, vitality and work pressure are important issues. In other words, how vital are you to mitigate that work pressure. (Organization 6)

Different from organizations with a facilitation philosophy, these agencies have a strong focus on internal mobility, both vertical and horizontal, which is stimulated in various ways. For example, Organization 13 tried to decrease specialization by implementing more generic job positions within the organization, whereas Organization 7 highlighted the need for talent management.

Theme 2: Mixed philosophies in a small number of cases

Interestingly, 20 percent of the cases demonstrated a mixed philosophy and could not be positioned into Schuler’s typology. That is, based on what the interviewees indicated as the agency’s idea guiding the design of their HRM system, it was not possible to assign one of the three philosophies in 20 percent of the cases. Rather, these cases showed a mix of a facilitation and accumulation philosophy.

On the one hand, Organizations 2 and 10 indicated that they actively support the broad development of employees for long-term employment, while at the same time emphasize that external mobility is just as important as internal mobility. While the first practice is associated with accumulation, the latter is more indicative of facilitation:

The talents that are there need to be developed and utilized as good as possible within the work field of [organization]. But if a gap develops between the talent and the organization, it is important to talk about the possibility to stay employed outside the organization. (Organization 10)

On the other hand, a group of five organizations (Organizations 5, 14, 16, 18 and 26) all strongly supported internal mobility, while also stressing that employees should take responsibility to seek development opportunities. Their strong focus on internal mobility is indicative of accumulation, while their emphasis on employee responsibility is indicative of facilitation:

Internal mobility is really important [.] and we have to facilitate this mobility. [.] That is mostly self-directed. People are responsible for their own development plan (Organization 16)

Theme 3: Ability- and motivation-enhancing policies are dominant policies

Looking at the HRM policies, four policies from the ability and motivation domains emerged as dominant: 1) training & development; 2) HR planning; 3) recruitment & selection and 4) performance management were mentioned by 60 to 70 percent of the interviewees as essential policies.

Many interviewees indicated that they explicitly focus on training & development, which includes at least a management or leader development program. Of these cases, six agencies mentioned that they have their own academy to offer training & development opportunities (Organizations 6, 11, 13, 14, 15 and 30). For example, Organization 6 offers long-term learning and work programs, while Organizations 14 and 15 mostly offer short modules for specific skills.

Around 63 percent of interviewees stated that their organization actively focuses on HR planning, although they differ in how advanced their planning process is. For most organizations, HR planning means trying to forecast the future needs of the organization in terms of numbers and type of employees.

Explicit policies around recruitment & selection are also viewed as essential by the interviewees:

[.] they are our gatekeepers of what gets into our organizations. That says something about the quality that we bring in. If it doesn’t go well there, then the effectiveness of your human capital could become worse. (Organization 22)

Finally, performance management appears to be a relatively common policy as well, although it mostly refers to performance appraisals. Almost all agencies of the 60 percent that mentioned performance management as important have developed a system of at least three different appraisals in one year and have given supervisors the main responsibility for these tasks.

In contrast to the four dominant policies, there are four less common policies – mainly from the opportunities domain—that were mentioned by 20 to 27 percent of the interviewees: 1) policies around internal promotion and labor market, 2) working conditions, 3) diversity and 4) job design.

The interviewees that mentioned internal promotion policies indicated that they mostly try to give opportunities to employees by posting vacancies on the intranet, although other ways are used to stimulate internal mobility. For example, Organization 26 has introduced the so-called opportunity board, with internal projects to which employees can subscribe.

Policies around working conditions were mentioned by a small number of interviewees as an important means to actively decrease absenteeism, stress or burnout. Ways to confront these issues vary from conducting research into employees’ workload (Organization 18), offering a health check (Organizations 5, 15 and 26) to free use of sport facilities (Organization 28). Policies around diversity and equal opportunities are mostly implemented based on the idea of being socially responsible:

In every aspect you want to strive towards, reflection is too strong a word, but more balanced representation of what is found in society. [.] it is always better to become more diverse. This means diversity in the broadest sense, not limited to ethnicity or origin. (Organization 20)

Finally, policies around job design mainly refer to the implementation of new ways of working. This often includes time- and place-independent work arrangements. Also, employees are often given a laptop and telephone to facilitate working outside the organization physically.

Theme 4: Similarities in HRM strongly shaped by external factors

As shown in and , it becomes apparent that the philosophies and policies that are dominant in our cases – i.e. a facilitation philosophy and the four common policies – are strongly shaped by external factors. Whereas philosophies seem mostly shaped by societal trends and parent ministries, policies are shaped by parent ministries, central government, politic, the labor market and technology.

Societal trends

The facilitation philosophy that is present in many agencies seems particularly shaped by societal trends in the Netherlands, a factor from the SCL dimension. In this respect, a society in which citizen participation and voice has increased, and wherein views on careers have changed from a traditional organization-steered to an individual-steered process, is reflected in the agency’s philosophy (De Vos & Van der Heijden, Citation2017). For example, Organization 21 stated that the facilitating role staff departments have taken is mainly the result of societal developments.

Parent ministry

The parent ministry, another factor from the SCL dimension, also drives a facilitation philosophy, though not quite as strongly as societal trends. Agencies are regularly advised to adopt a certain HRM approach similar to that of the parent ministry, although, depending on the degree of autonomy, agencies can decide to adopt or not. Interviewees indicated that managers at parent ministries have instructed to adopt a facilitation approach toward employees, for example by adopting a self-directed benefits model.

In addition to a facilitation philosophy, parent ministries also have an influence on recruitment and selection policies. In particular, interviewees from agencies with less autonomy – mainly Type 1 agencies – mentioned the lack of freedom in hiring or firing employees.

Central government

Whereas parent ministries seem to primarily shape recruitment and selection policies, the influence of central government, via norms drawn up by the Home Office, is discernable in all four common policies. For example, following the so-called mobility letter in 2015 of the Minister concernedFootnote1, organizations were expected to develop policies around HR planning and mobility. Also, relatively strict norms exist for recruitment & selection and performance management policies. For example, agencies are strongly advised to use the same 62 job profiles (Functiegebouw Rijk) as the central government uses, which has consequences for how agencies select and appraise their employees. It does seem, however, that the influence of central government seems stronger for agencies with less formal autonomy. Interviewees of Type 1 agencies indicated that there are government guidelines for nearly every aspect of their HRM design, whereas interviewees of Type 2 and Type 3 only mentioned the influence on specific policies.

Politics

Another finding noteworthy is the influence of political decisions on recruitment & selection and training & development policies, mainly indirect via imposed reforms or through changes in an agency’s task. For some interviewees, the constant possibility to reform is something that heavily affects their policies:

[.] if you live in an organization that goes from one reorganization to another, you cannot even talk about HRM policy. Then you are not doing that at all. (Organization 21)

Labor market and technology

In addition to factors from the SCL dimension, developments in the labor market and technology, factors from the PMT dimension, also drive the adoption of one of the four common policies. Interviewees mentioned that the availability of competent and suitable candidates on the labor market strongly affects the recruitment & selection and training & development policies. In some cases, the specialized task they perform hinders the search for suitable employees. Finally, technology is often mentioned as an important factor that shapes training & development policies, because many of the older employees need to gain new skills in this area.

Theme 5: Differences in HRM strongly shaped by internal factors

Where similarity in HRM seems mostly driven by external factors, differences are strongly shaped by internal factors, both as the result of institutionalized organizational characteristics and of strategic choices made by influential actors. The agencies that have adopted philosophies and policies that diverge from the majority of the cases appear to do so because of internal instead of external demands. As seen in and , these philosophies and policies seem to be shaped by internal factors related to organizational characteristics, influential actors and one external factor related to digitalization.

Organizational characteristics

Interviewees from agencies that have adopted an accumulation philosophy or one of the four less common policies argued that organizational characteristics are strong internal institutional drivers. For example, the accumulation philosophy in Organization 2 is a direct consequence of their organizational strategy for the period until 2020, while the accumulation philosophy at Organization 26 is partly influenced by the fact that they have 24-hour work shifts. For the less common policies, some interviewees noted that being a public organization, and a role model, is an important factor to use diversity policies. In this respect, their publicness gives agencies a need to be more socially responsible by striving for a diversified staff that is representative of society.

Influential actors

Besides organizational characteristics, differentiation is strongly driven by influential actors in in the organization, especially in medium-to-large Type 2 and Type 3 agencies. For example, in Organization 14, the head of HR has a strong influence on the presence of an accumulation philosophy, as constant development was viewed as particularly important to focus on. Also, board members and shareholders were mentioned as influential actors for the adoption of one of the less common policies. For example, interviewees of Organizations 25 and 28 noted that their diversity policies are strongly stimulated by their shareholders, the ministries of Economic Affairs and Finance.

Digitalization

In addition to internal factors, digitalization, a factor from the PMT dimension, seems to be the only external factor important for organizations with an accumulation philosophy. In this case, digitalization does not account for differences between agencies per se, but rather affects agencies with an accumulation philosophy more than agencies with a facilitation philosophy. Given the fact that digitalization substantially changes the nature of some jobs, agencies that emphasize long-term employment need to guide their employees in these changes.

Discussion

Taking a contextual perspective, this explorative study examined the similarities and differences in HRM philosophies and policies in Dutch agencies, and how they are shaped. To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the very first to show the influence of context on HRM (see for an exception Farndale & Paauwe, Citation2007), especially on HRM philosophies and policies. In comparing the data across our cases, several themes have emerged. In general, these themes illustrate that among a variety of agencies similar philosophies and policies prevail. Furthermore, in line with Farndale and Paauwe (Citation2007), our findings show that decisions regarding HRM are strongly affected by external factors, leading to similarity among agencies. Internal factors seem to be more instrumental in light of differentiation among agencies. Finally, our study demonstrates that, at least among agencies, context influences HRM philosophies and policies differently, leading to potential discrepancies in the implementation process.

Our findings highlight the dominance of the facilitation philosophy among agencies. Emphasizing employee responsibility and taking a facilitating role diverge from the traditional view on public sector HRM, which is more consistent with an accumulation philosophy that is only present in a small number of our cases (Truss, Citation2008). Standardization and paternalization seem to have been replaced by ideas of flexibility and individualization, which fit with the often-mentioned motive of the Dutch government to create agencies in the first place (Van Thiel, Citation2001)

In addition to changes in public sector HRM, the dominance of this philosophy can also be linked to general changes in career patterns from traditional careers to protean (Hall, Citation2002), boundaryless (Arthur, Citation2014) and sustainable careers (De Vos & Van der Heijden, Citation2017). Giving employees responsibility to look for development opportunities outside the agency stimulates careers that are individually steered and not confined to a single organization. This trend is further enhanced by a high degree of openness in the recruitment process in Dutch government for external applicants (OECD, Citation2008).

Our findings show that the four common policies that were identified pertain to the abilities and motivation domains, whereas policies from the opportunities domain were much less emphasized. Training & development is found to be one of the policies mentioned most often, which is in line with earlier research demonstrating its importance in both the public and private sectors (Kalleberg, Marsden, Reynolds, & Knoke, Citation2006). The dominance of policies around HR planning and performance management demonstrates that business-like policies and processes, such as result-oriented management and strategic decision-making, have been adopted in agencies (Truss, Citation2008).

In line with the CBHRT, we found that similarities in philosophies and policies are strongly shaped by external factors (Paauwe, Citation2004). Interestingly, there seems to be a considerable difference in how similarities in philosophies and policies are shaped. Whereas societal trends are the main drivers toward the adoption of a facilitation philosophy, the adoption of the four common policies is for a great deal affected by actions and norms set by central government and parent ministries. For agencies, this finding leads to the question whether they indeed have autonomy to design HRM on all levels and, in turn, their ability to adopt strategic HRM. This issue seems especially present for Type 1 agencies, who are free to develop their own philosophy but are, at the same time, strongly pressured to adopt specific policies developed by central government. Furthermore, these differences in how philosophies and policies are shaped can have negative consequences as it may lead to discrepancies in the implementation process that, in turn, may have a negative impact on employee attitudes and behavior (Kellner et al., Citation2016).

In contrast to the drivers of similarity, differences between agencies seem mostly driven by internal factors, which is also in line with the CBHRT (Paauwe, Citation2004). Both the influence of internal institutionalized factors and strategic choice made by influential actors become visible in the findings of our empirical study. For the use of an accumulation philosophy, the organization’s strategy appears to be one of the main drivers, supporting the notion that part of the agencies exhibits at least some aspects of strategic HRM (Teo, Citation2000). For the use of the four less common policies, a variety of internal factors play an important role. Noteworthy is the impact of influential actors, such as top-level management and shareholders. It appears that in some agencies, the influential actors are able to mitigate the influence of external factors and, herewith, enable them to make strategic choices, which Paauwe (Citation2004) refers to as having considerable room for maneuver. Future research using a longitudinal approach is needed to examine the process of how influential actors deal with external pressures when making choices regarding HRM.

Several of our results are inconsistent with the earlier theories that have been used for HRM philosophies and policies. First, some agencies demonstrated a mix of both a facilitation and accumulation philosophy. Schuler (Citation1989) argued that inconsistency in the adoption of a philosophy is described as a potential source of conflict and could increase ambiguity. For two small- to medium-sized agencies, with almost no internal labor market, their mixed philosophy seems contradictory and could potentially have negative consequences. In contrast, for five large agencies, their mixed philosophy of long-term development with high employee responsibility does not seem contradicting, due to their large internal labor market containing many internal development opportunities. This finding indicates that a mixed philosophy could be a logical choice based on the organizational structure. Future research could further identify other types of hybrid HRM philosophies and determine whether they may be a potential advantage or source of conflict. Second, we found that policies from the opportunities domain were not mentioned often. According to the AMO framework (Appelbaum et al., Citation2000; Lepak et al., Citation2006), organizations that fail to address all three AMO domains may not maximize their employees’ potential by creating synergetic effects and may, consequently, underperform (Jiang et al., Citation2012). It could be that employees in our cases do get the opportunity to perform, but that this has not been formalized in HRM policies. Future research should examine if and how employees are provided with opportunities to perform in agencies. Finally, our study shows that HRM philosophies and policies are shaped differently by the specific context, which contrasts with the idea that the relationship between components of the HRM architecture is ‘rational and deterministic in nature’ (Lepak et al., Citation2004, p. 649). Achieving alignment between HRM components does not seem to be just a case of fitting policies with the philosophy, but also requires recognizing and, possibly, managing the contextual factors that shape the different components. Future research should further examine how other components of the HRM architecture are influenced by context and whether similar mechanisms can be found in other types of organizations.

Our conclusions are limited due to the inclusion of Dutch agencies only. Given the dearth of research on HRM philosophies, we are not able (yet) to posit that the dominance of the facilitation philosophy is unique for agencies. We urge scholars to examine philosophies in other types of organizations, especially in purely public and private organizations. Our study is also limited due to the use of HR managers only as our interviewees, which limits our perspective to intended HRM philosophies and policies only (Renkema, Meijerink, & Bondarouk, Citation2017). Investigating line manager and employee perceptions of HRM philosophies and policies would be valuable to see to what degree they differ from the views of managers. Another limitation is the possibility of social desirability in the answers given by the interviewees. This may explain the absence of agencies with a utilization philosophy in our sample, as this philosophy may have negative connotations. In addition to addressing social desirability in future research, it would also be interesting to investigate the presence of utilization philosophies in other types of organizations, indicating whether these negative connotations are universal or specific to the type of organization. Finally, because we did not ask about the influence of specific factors, it is possible that some existing factors were unobserved. For example, we did not identify mimetic pressures that shape HRM, although our findings certainly identified mimicry among agencies. It would be interesting to further examine the influence of specific factors that are not identified in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 On November 20 in 2015, the former Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations sent a letter to the House of Representatives, which focused on increasing the mobility and flexibility of civil servants. This letter addressed every organization connected to central government and civil servants falling under the government labor agreement. One of its primary action points for organizations was to develop a multiyear HR planning.

References

- Alford, J., & Hughes, O. (2008). Public value pragmatism as the next phase of public management. The American Review of Public Administration, 38(2), 130–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008314203

- Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Manufacturing advantage. Why high-performance work systems pay off. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Arthur, M. B. (2014). The boundaryless career at 20: Where do we stand, and where can we go? Career Development International, 19(6), 627–640. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/cdi-05-2014-0068

- Bach, T. (2014). The autonomy of government agencies in Germany and Norway: Explaining variation in management autonomy across countries and agencies. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 80(2), 341–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852313514527

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barney, J. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Perspectives, 9(4), 49–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1995.9512032192

- Becker, B. E., & Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of human resource management on organizational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 779–801. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/256712

- Beer, M., Boselie, P., & Brewster, C. (2015). Back to the future: Implications for the field of HRM of the multistakeholder perspective proposed 30 years ago. Human Resource Management, 54(3), 427–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm

- Beer, M., Spector, B. A., Mills, D. Q., & Walton, R. E. (1984). Managing human assets. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Bin Othman, R. (1996). Strategic HRM: Evidence from the Irish food industry. Personnel Review, 25(1), 40–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00483489610106172

- Boselie, P. (2010). High performance work practices in the health care sector: A Dutch case study. International Journal of Manpower, 31(1), 42–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/01437721011031685

- De Vos, A., & Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2017). Current thinking on contemporary careers: The key roles of sustainable HRM and sustainability of careers. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 28, 41–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.07.003

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & Tinkler, J. (2005). New public management is dead - Long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(3), 467–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui057

- Farndale, E., & Paauwe, J. (2007). Uncovering competitive and institutional drivers of HRM practices in multinational corporations. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(4), 355–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2007.00050.x.

- Fombrun, C., Tichy, N., & Devanna, M. (1984). Strategic human resource management. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

- Guest, D. E. (2011). Human resource management and performance: Still searching for some answers. Human Resource Management Journal, 21(1), 3–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00164.x

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Hall, D. T. (2002). Careers in and out of organizations. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Jackson, S. E., Schuler, R. S., & Jiang, K. (2014). An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 1–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.872335

- James, O., & Van Thiel, S. (2011). Structural devolution and agencification. In T. Christensen & P. Laegreid (Eds.), Ashgate research companian to new public management (pp. 209–222). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Han, K., Hong, Y., Kim, A., & Winkler, A.-L. (2012). Clarifying the construct of human resource systems: Relating human resource management to employee performance. Human Resource Management Review, 22(2), 73–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.11.005

- Kalleberg, A. L., Marsden, P. V., Reynolds, J., & Knoke, D. (2006). Beyond profit? Sectoral differences in high-performance work practices. Work and Occupation, 33(3), 271–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888406290049

- Kelliher, C., & Perrett, G. (2001). Business strategy and approaches to HRM ‐ a case study of new developments in the United Kingdom restaurant industry. Personnel Review, 30(4), 421–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480110393303

- Kellner, A., Townsend, K., Wilkinson, A., Greenfield, D., & Lawrence, S. (2016). The message and the messenger: Identifying and communicating a high performance “HRM philosophy”. Personnel Review, 45(6), 1240–1258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2015-0049

- Kickert, W. J. M. (2001). Public management of hybrid organizations: Governance of quasi-autonomous executive agencies. International Public Management Journal, 4(2), 135–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7494(01)00049-6

- King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C.Cassel & G.Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp 256–270). London: Sage Publications.

- Lepak, D. P., Liao, H., Chung, Y., & Harden, E. E. (2006). A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 25, 217–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0742-7301(06)25006-0

- Lepak, D. P., Marrone, J. A., & Takeuchi, R. (2004). The relativity of HR systems: Conceptualising the impact of desired employee contributions and HR philosophy. International Journal of Technology Management, 27(6/7), 639–655. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2004.004907

- Monks, K., Kelly, G., Conway, E., Flood, P., Truss, K., & Hannon, E. (2013). Understanding how HR systems work: The role of HR philosophy and HR processes. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(4), 379–395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00207.x

- OECD. (2008). The state of the public service. Paris: Author.

- Paauwe, J. (2004). HRM and performance: Unique approaches for achieving long-term viability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Paauwe, J., & Boselie, P. (2003). Challenging ‘strategic HRM’ and the relevance of the institutional setting. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(3), 56–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2003.tb00098.x

- Posthuma, R. A., Campion, M. C., Masimova, M., & Campion, M. A. (2013). A high performance work practices taxonomy: Integrating the literature and directing future research. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1184–1220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313478184

- Renkema, M., Meijerink, J., & Bondarouk, T. (2017). Advancing multilevel thinking in human resource management research: Applications and guidelines. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 397–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.03.001

- Rodwell, J. J., & Teo, S. T. T. (2008). The influence of strategic HRM and sector on perceived performance in health services organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(10), 1825–1841. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802323934

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE Publications.

- Schuler, R. S. (1989). Strategic human resource management and industrial relations. Human Relations, 42(2), 157–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678904200204

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Subramony, M. (2009). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between HRM bundles and firm performance. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 745–768. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20315

- Teo, S. T. T. (2000). Evidence of strategic HRM linkages in eleven Australian corporatized public sector organizations. Public Personnel Management, 29(4), 557–574. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/009102600002900412

- Truss, C. (2008). Continuity and change: The role of the HR function in the modern public sector. Public Administration, 86(4), 1071–1088. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.00718.x

- Van Thiel, S. (2001). Quangos: Trends, causes, and consequences. (Dissertation) Utrecht University.

- Van Thiel, S. (2012). Comparing agencies across countries. In K. Verhoest, S. Van Thiel, G. Bouckaert, & P. Laegreid (Eds.), Government agencies: Practices and lessons from 30 countries (pp. 18–28). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Verhoest, K., Peters, B. G., Bouckaert, G., & Verschuere, B. (2004). The study of organisational autonomy: A conceptual review. Public Administration and Development, 24(2), 101–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.316

- Verhoest, K., Roness, P. G., Verschuere, B., Rubecksen, K., & MacCarthaigh, M. (2010). Autonomy and control of state agencies. Houndmilss: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Verhoest, K., Van Thiel, S., Bouckaert, G., & Laegreid, P. (2012). Government agencies: Practices and lessons from 30 countries. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wright, P. M. (1998). HR – strategy fit: Does it really matter? Human Resource Planning, 21(4), 56–57.

- Wright, P. M., & Nishii, L. H. (2007). Strategic HRM and organizational behavior:Integrating multiple levels of analysis. CAHRS Working Paper Series, Paper, 468, 1–26.

- Wynen, J., Verhoest, K., & Rubecksen, K. (2014). Decentralization in public sector organizations: Do organizational autonomy and result control lead to decentralization toward lower hierarchical levels? Public Performance & Management Review, 37(3), 496–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576370307

- Yesilkagit, K., & Van Thiel, S. (2012). The Netherlands. In K. Verhoest, S. Van Thiel, G. Bouckaert, & P. Laegreid (Eds.), Government agencies: Practices and lessons from 30 countries (pp. 179–190). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.