Abstract

In this review paper, we critically examine the evidence base relating to engagement within the public sector given a wide range of public services have faced acute human resource challenges over recent years. Our review of 188 empirical studies reveals that much of the evidence focuses attention on individual and job level factors, such that specific public sector contextual contingencies have rarely been considered. Through identifying significant ‘context gaps’, we present a future research agenda addressing the following key areas: i) clarifying the relationship between engagement and public service motivation, ii) further contextualizing general engagement models, iii) exploring cultural, socio-political, and institutional factors in more depth, iv) encouraging a more critical perspective on engagement, v) understanding the variation in the experience of engagement across different public services/delivery models, and vi) connecting more strongly with practical concerns and initiatives within public organizations. In presenting this agenda, we highlight how engagement and HRM scholars can more strongly embed their research within a sectoral context.

Introduction

As research on engagement has gathered pace over the last decade, with more efforts being made to apply this knowledge to inform HR policy and practice (Bailey, Citation2016; Purcell, Citation2014), evaluating the quality of the evidence base becomes particularly important (Madden, Bailey, Alfes, & Fletcher, Citation2018). Although a small number of reviews and meta-analyses on the topic have been published over the last few years (e.g. Bailey, Madden, Alfes, & Fletcher, Citation2017; Crawford, LePine, & Rich, Citation2010; Peccei, Citation2013), none have explicitly situated engagement within a sectoral context. In consequence, our understanding of engagement remains acontextual which, as Purcell (Citation2014, p.242), argues is “taking us backwards to a dangerously simplistic view of work relations” and as such reduces the precision and application of engagement theory to HRM practice. This issue is more acute when considered alongside other concerns within the HRM community regarding the susceptibility of engagement as a ‘fad-like’, ‘old wine’, ‘normative’ concept that is too focused on the micro-level (Guest, Citation2014; Keenoy, Citation2014; Valentin, Citation2014). Moreover, although many scholars have tended to coalesce around the notion of engagement as ‘work engagement’, i.e. a positive psychological state connoting vigor, dedication, and absorption in work activities (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, Citation2002), disputes persist concerning definitions and measures (Bailey et al., Citation2017).

The relevance of context, and in particular the relevance of sectoral/institutional context, to understanding psychological and behavioral phenomena within organizations has been highlighted by a range of HRM scholars (e.g. Cooke, Citation2018; Dewettinck & Remue, Citation2011). More specifically for engagement, features of the wider industrial context are likely to shape how engagement is experienced because they “affect the occurrence and meaning of organizational behavior as well as functional relationships between variables” (Johns, Citation2006, p.386). In one of the first attempts to explicitly examine the influence of context on engagement, Jenkins and Delbridge (Citation2013) found evidence to suggest that industry sector and market conditions influence the HRM and the general managerial approach adopted with the aim of fostering engagement within the organization. Moreover, in a recent meta-analysis, Borst, Kruyen, Lako, and de Vries (Citation2019) highlighted that the relationships between work engagement and other work-related attitudes tends to be stronger for public sector than for private employees. Findings such as these suggest that a more contextualized analysis of engagement is needed because when we examine engagement in context, we can better identify the specific range of influencing factors as well as the precise ways in which engagement is experienced.

Related to this, there is also concern that much research within HRM focuses on a psychologized view that objectifies, generalizes, and reduces the employment relationship in such a way whereby “human beings [are treated] almost as if they are billiard balls, subject to rather simple laws of behaviour” (Godard, Citation2014, p.10). As Purcell (Citation2014, p.244) notes “the consequence is…a distorted and misleading mirror on the world of work”, which therefore leads to simplistic, yet potentially ineffective initiatives. Importantly, a key issue arises when legitimate findings from academic research are applied in an uncritical and generalized way to a wide range of organizational settings (Dundon & Rafferty, Citation2018). Often practitioners, and scholars, may articulate broad recommendations from these findings that are not specific enough to address the pragmatic issues at hand, or indeed that obscure managers’ ability to tailor practices to fit their own organizational context. Moreover, they may also neglect very real changes within a sector, such as the impact of austerity and regulatory reform within public services. These concerns regarding the lack of contextual and critical insight have also been levelled at engagement research (Guest, Citation2014; Purcell, Citation2014; Valentin, Citation2014), yet, thus far, no attempt has been made to systematically review the evidence base on engagement while also considering the relevance of context.

The public sector context

To address this gap, our goal is to present the findings of a systematic review of the empirical evidence relating to engagement within the public sector context. In this paper, the public sector refers to the broad sectoral domain occupied by three types of public organizations: a) governmental/federal institutions, b) public institutional systems, and c) public enterprises, i.e. hybrid/semi-public organizations. In this sense, the ‘public sector' often denotes an aggregated sector of (mainly) publicly-funded activities whose performance is evaluated against a series of social oriented values based on institutional expectations and democratic accountability. The term ‘public services' then denotes the range of organizational settings, within the public sector, that deliver specific services to the public, such as healthcare or education.

The public sector is a particularly interesting setting to focus on given the reported differences between private sector and public service employees. For instance, Bakker (Citation2015, p.723) argues that it is those people who want to “make the world a better place” who are often attracted to public services while Furnham, Hyde, and Trickey (Citation2014) find differences in personality traits between those in public and private sectors. This suggests that different individual processes may operate across the two sectors, with those predisposed to public service values and ideals more likely to self-select into public service roles (Vandenabeele, Citation2008). Therefore, the approach taken by HRM practitioners to facilitate engagement may need to be different within the public sector context compared with the private sector context. Indeed, there is evidence that some HR practices may not be as relevant or important within the context of the public sector; for example, Bryson, Forth, and Stokes (Citation2017) show that performance related pay is positively associated with work attitudes for private sector, but not for public sector employees.

Focusing on engagement within the public sector context is especially pertinent at a time when the sustainability of traditional public service motivation (PSM), i.e. the extent to which an individual is altruistically and prosocially motivated to serve other people and society (Perry & Wise, Citation1990), is called into question through government reforms centred around austerity and marketization (Esteve, Schuster, Albareda, & Losada, Citation2017). These reforms have tended to focus on the notion of New Public Management (NPM) which emphasizes performance improvement and accountability, the embedding of results-orientated cultures, and the adoption of private-sector managerial practices (Verbeeten & Speklé, Citation2015). However, in many public sector organizations, this performance-focused, marketized logic has increased the divide between management and workers such that public sector workers may feel as if they are managed by people who do not understand or care about public sector work and its ethos. Therefore, despite public managers across many countries welcoming engagement as an individually-focused motivational approach that underpins a public service value chain linking engaged employees with customer or service user satisfaction (OECD, Citation2016), there remain potential issues surrounding NPM and austerity that may undermine the experience of engagement (Esteve et al., Citation2017). Moreover, given that social norms and expectations surrounding the provision of public services, as well motivations of public sector employees, tend to be society/community focused, there is also a need to evaluate the evidence regarding the links between engagement and public service outcomes, particularly those that may be obscured by the move towards a customer/value chain orientation.

In reviewing the empirical evidence on engagement within the public sector, we aim to develop an informed understanding of ‘what’s missing’ theoretically and empirically from the evidence base and in doing so help to clarify avenues for future research that enable a stronger sector-specific and contextually nuanced understanding of engagement. In doing so, we aim to help HRM scholars and practitioners identify how engagement models and practices may need to be modified to better meet the needs and challenges within a particular sectoral context. Overall, we seek to answer three questions: (1) what antecedents are associated with the engagement of public service workers, (2) what evidence is there that engagement is associated with desired public service outcomes, and 3) what critical contextual gaps emerge from the evidence base that, if addressed, could provide further theoretical and empirical insight into engagement within the public sector?

Review method

For the current review the five stages of systematic approach recommended by Briner and Denyer (Citation2012) were followed. Business Source Complete, International Bibliography for the Social Sciences, Nexis, Zetoc and Scopus were systematically searched for relevant, peer-reviewed studies published in the English language from 1990, the date when the first major peer-reviewed study on engagement was published (Kahn, Citation1990), to 2017. To cover the most up-to-date and relevant research, we ran an additional focused search in selected HRM and public administration/management journals using the Chartered Association of Business Schools journal ranking list.

Search terms were initially developed by conducting open search approaches to determine the potential scope of the literature and to test variations of keywords. We tried various combinations and configurations of keywords to collate a list of potential search strings. We then asked external subject matter experts to review the keywords/search strings before trialling longer search string combinations to ascertain the range of studies that would be included or excluded. We then agreed upon two strings of search terms; the first focusing on the most common terms for engagement such as “work engagement” OR “employee engagement”; the second focusing on terms to describe the public sector context such as “public sector” OR “public service”. The search strings focused on keywords within titles and abstracts.

Four quality criteria were agreed for items to be taken forward for evaluation: a) adequacy/validity/sufficiency of research design, b) sensitivity and specificity of sample and analyses, c) relevance and appropriateness of the study to the review’s research questions, and d) robustness, rigor, and replicability of the study1. Moreover, to identify those studies that focused on public services, we carefully examined the reported methodology and sample characteristics. We included any study where at least 75 percent of the sample comprised public service employees in order to ensure findings were focused on the public sector context. If the study included a mix of workers from different sectors2, then it was only included if a) the number of public service employees allowed robust statistical analyses/qualitative interpretations to be drawn, and b) the subsample of public service employees was analyzed separately or comparatively with other subsamples. To confirm which studies to include, we individually contacted the authors of 149 studies to clarify sample characteristics. Six studies were included based on these criteria and from communicating with authors. These were all comparative in nature and represented an emerging new strand of evidence that is detailed at the end of the findings.

We piloted the abstract sifting process first – each of four members of the research team evaluated a total of 50 abstracts and each abstract was double evaluated. We calculated the consensus kappa rating and found that it satisfied conventional thresholds (kappa = .77). We therefore proceeded to reviewing the full range of abstracts, whereby a sample of 20% of each reviewers’ evaluations, along with any ‘unsures’, were double checked. Data from each included item were extracted using a proforma that focused on retaining key details regarding the study’s theoretical and methodological foundations as well as information addressing the research questions. In total, 188 studies are included in our review.

Overview of studies

Conceptualizing engagement

Given that previous reviews of the engagement literature find multiple conceptualizations of engagement (e.g. Bailey et al., Citation2017), we first examine the extent to which different perspectives on engagement have been utilized across the 188 included studies. We find that most studies (160 studies; 85.1 percent) coalesce around one main perspective of engagement; that of ‘work engagement’ (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002), with the remaining 28 studies drawing on a mix of other perspectives. Considering this, we decided to bring the main collection of 160 studies together as one core grouping of ‘work engagement studies’, while the remaining 28 studies were grouped together as a secondary grouping of ‘employee engagement’ studies. In conducting the rest of this review, we therefore separate out and distinguish between the body of evidence regarding the ‘work engagement’ studies and that of the ‘employee engagement’ studies so that a cohesive, yet comprehensive narrative can be developed. In doing so, we critically evaluate the dominant ‘work engagement’ perspective whilst also being able to contrast this with the evidence arising from the ‘employee engagement’ studies. Before continuing with the review, we now briefly discuss the main theoretical foundation of the ‘work engagement’ studies and the more diverse range of theoretical approaches underpinning the ‘employee engagement’ studies. For more comprehensive overviews please refer to Shuck (Citation2011), Peccei (Citation2013), Saks and Gruman (Citation2014), and Truss, Delbridge, Alfes, Shantz, and Soane (Citation2014).

‘Work engagement’

Schaufeli et al's. (Citation2002) work engagement definition and perspective views engagement as a positive work-related psychological state that connotes vigor (i.e. feelings of energy, mental resiliency, and persistence), dedication (i.e. feelings of involvement, commitment, and enthusiasm), and absorption (i.e. feeling fully immersed and engrossed) in work activities. The theoretical foundations of Schaufeli et al's. (Citation2002) work engagement construct are grounded in the job demands-resources model (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008), which differentiates between two main categories of job characteristics: demands and resources. Job demands refer to characteristics such as time pressure, workload, and emotional demands that cost energy and exert strain on the individual and so have a negative effect on engagement as they represent a health impairment pathway. In contrast, job resources represent a motivational pathway that enhances engagement and connote characteristics such as autonomy, social support, and opportunities for development that enable individuals to cope with demands, satisfy basic psychological needs, and achieve organizational goals. It is also claimed that resources and demands interact, such that the resources are particularly important for engagement when demands are high.

‘Employee engagement’

Of the remaining 28 studies, 20 studies adopt one of the following four perspectives on engagement, whilst the remaining eight draw upon a mix of different perspectives rather than focusing on one specifically.

‘Personal role engagement’

11 studies draw mainly from Kahn’s (Citation1990) personal role engagement perspective that views engagement as a socially embedded and role-based phenomenon, such that engaged “people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances” (Kahn, Citation1990, p.694). The theoretical framework often adopted in these studies draw upon Kahn’s (Citation1990) psychological conditions of meaningfulness, availability, and safety, which are viewed as core processes through which the work context influences the experience of engagement.

‘Multidimensional engagement’

Extending the notion of role-based engagement, four studies utilize Saks’s (Citation2006) conceptualization of engagement as a multi-foci construct connoting ‘psychological presence’ within one’s job role as well as within one’s role as an organizational member that is underpinned by the social exchange relationship, i.e. giving and receiving of socio-emotional resources, between the employee and the employer.

‘Engagement as management practice’

Three studies explore engagement as a management/organizational practice (e.g. Reissner & Pagan, Citation2013), which is quite different from the others in that it focuses on the practice of “doing” engagement rather than the experience of “being” engaged (Bailey, Citation2016; Bailey et al., Citation2017). These studies tend to draw upon broader theories within HRM and critical management studies.

‘Faculty engagement’

One emerging new perspective adopted by two studies is that of “faculty engagement” (Selmer, Jonasson, & Lauring, Citation2013), which draws on Schaufeli et al's. (Citation2002) work engagement perspective to delineate an occupation-specific (i.e. academic/teaching-specific) form of engagement.

Timeline

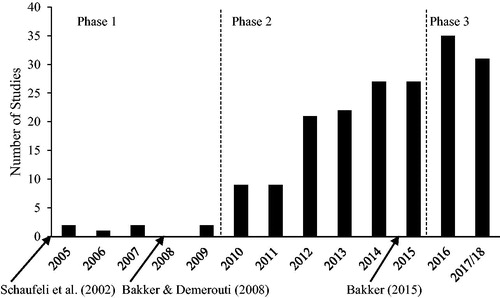

Despite starting our search in 1990, the first empirical study that met the inclusion criteria was not published until 2005. From 2005 to 2009, only seven studies met our inclusion criteria, and this then increased from nine in 2010 to 36 in 2016, with numbers rising steeply from 2012 and levelling out in 2017/18. illustrates this and indicates that the evidence is clustered around three main time periods: 1) 2005- 2009 whereby studies tended to focus on applying general theoretical models of engagement to various public service contexts; 2) 2010-2015 when studies started expanding application of engagement into occupation-specific domains such as education and nursing; and 3) 2016-to-date, during which time a more sector-specific discussion of engagement began to emerge, particularly as interest in engagement expanded into the public management/administration disciplines.

These time periods are not explicitly distinct nor represent core shifts in viewpoints or research agendas. However, they do represent gradual changes in focus and a branching out from the applied psychology discipline that broadly follows from key highly cited conceptual papers on ‘work engagement’ published a few years prior to each phase. The 2005-2009 time period seems to follow on from the seminal introduction of Schaufeli et al's. (Citation2002) conceptualization of ‘work engagement’ to the applied psychology discipline, the 2010 to 2015 period follows on from the establishment of the JD-R model underpinning ‘work engagement’ (e.g. Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008), and the 2016-to-date period follows on from Bakker’s (Citation2015) application of this core foundational model to the public services context. Although it has been problematic that engagement research has historically not been focused on developing a contextualized understanding, it is encouraging that the latest phase of research is starting to put context more centre stage. However, this phase is emerging and there remain relatively few studies, particularly from the dominant ‘work engagement’ research groups, that specifically focus on context.

Study characteristics

gives an overview of the core methodological characteristics of the included studies. We discuss the characteristics of the 160 ‘work engagement’ studies first before outlining the characteristics of the 28 ‘employee engagement’ studies.

Table 1. Overview of the methodological characteristics of the included studies.

‘Work engagement’ studies

It is somewhat surprising that relatively few of the ‘work engagement’ studies in our sample are explicitly orientated towards advancing our understanding of public sector/service workers. Rather, many take an occupational or profession-specific focus in that they orientate themselves to better understanding the engagement experiences of a particular group of workers within a specific profession or occupation, such as nursing (e.g. Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, Citation2012), or orient themselves towards testing a general engagement model by using a sample of public sector workers (e.g. Barbier, Dardenne, & Hansez, Citation2013). Moreover, nearly three quarters of the ‘work engagement’ studies focus on healthcare (e.g. Hakanen & Schaufeli, 2012) or educational (e.g. Bakker & Bal, Citation2010) settings; with only 10 percent focusing on governmental employees (e.g. van der Voet & Vermeeren, Citation2017).

Although this may not appear overly problematic, it represents a lack of precision regarding whether findings can be attributed more towards general occupational factors or more towards the specific public service/sector context. For example, public sector nurses may be more strongly constrained by budgetary cuts and national targets than their private sector counterparts. Therefore, differentiating between what can be attributed to the nursing occupation versus the public healthcare context is important. Additionally, the vast majority of studies were conducted in European countries, particularly in Continental European countries such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium. This therefore gives only a partial and somewhat skewed insight into understanding the public sector context.

Regarding research designs and measures, most studies are based on cross-sectional (mainly self-report) surveys that utilize the 9-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9), for example Petrou, Demerouti, and Xanthopoulou (Citation2017). However, there are several studies that utilize complex research designs, particularly longitudinal/time-lagged (e.g. Nguyen, Teo, Pick, & Jemai, Citation2018), multilevel (e.g. Vera, Martínez, Lorente, & Chambel, Citation2016), or intervention (e.g. Boumans, Egger, Bouts, & Hutschemaekers, Citation2015) designs, yet, given the reliance on cross-sectional and single method studies, causal inferences regarding antecedents/outcomes of engagement are somewhat limited.

Overall this methodological landscape adds to the problem regarding understanding the precise contextual contingencies that may influence the drivers and outcomes of engagement. For example, these types of studies neglect to consider how the climate of austerity, work intensification, and pay freezes over recent years, within many public sector contexts across the globe, may be impacting upon/confounding empirical findings.

‘Employee engagement’ studies

Regarding the focus and orientation of the 28 ‘employee engagement’ studies, there is a more balanced split (compared with the ‘work engagement’ studies) between those that adopt a general or profession/occupation-focused orientation versus a public service/sector-specific orientation. However, it is still concerning that fewer than a third take a specific public service/sector perspective or theoretical grounding. Although cross-sectional (self-report) surveys also represent the majority of the 28 ‘employee engagement’ studies, there is a higher proportion of qualitative studies than in the ‘work engagement’ grouping. Unsurprisingly given the diversity of perspectives represented in the ‘employee engagement’ group, there is a wider range of measures utilized compared with the ‘work engagement’ collection of studies. Despite this, there tends to be more diversity in sample characteristics and there are good examples that help address a perennial problem within the wider engagement literature: that of the challenge of connecting with policy makers and HR practitioners (Bailey, Citation2016). For example, Byrne, Hayes, and Holcombe’s (2017) study shows how a large-scale survey dataset utilized by public organizations in the US can be analyzed in a theoretically meaningful way that helps build connections with the wider practitioner community.

Review findings

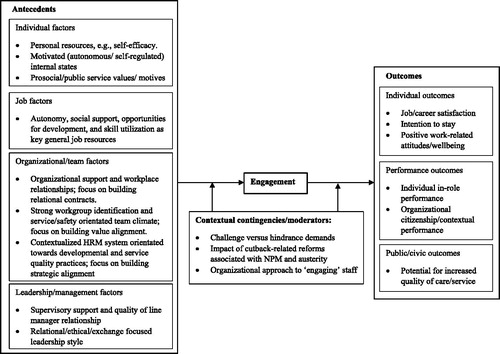

We now present the findings of our review of engagement studies within the public sector context starting with the antecedents of engagement within the public sector (RQ1), then its outcomes (RQ2) and lastly an emerging strand of evidence on differences between the public sector and other sectors (RQ3). To address RQ3 further, we highlight critical gaps within the evidence base throughout the review. In evaluating the evidence, wherever possible we focus on exemplar studies and evidence/insights that specifically focus on the public sector/services context. As discussed in the previous section, we differentiate between the 160 studies that have utilized Schaufeli et al's. (Citation2002) conceptualization and operationalization of ‘work engagement’ and the 28 studies that have adopted an alternative ‘employee engagement’ perspective. To aid holistic understanding, we provide an overarching map of the key antecedents, outcomes, and contextual contingencies uncovered by the review as . It is worth noting that ‘work engagement’ studies focus most on job-related antecedents and individual level outcomes, whereas the ‘employee engagement’ studies tend to provide insight into broader organizational/institutional contingencies.

Figure 2. Map of antecedents, outcomes, and contextual contingencies/moderators uncovered by the review.

Antecedents of engagement

The first research question aims to identify the antecedents of engagement within the public sector context. A total of 143 ‘work engagement’ studies and 25 ‘employee engagement’ studies examine various antecedents of engagement; summarizes the key findings from these studies. We begin by focusing on the ‘work engagement’ studies before outlining any additional insights from the ‘employee engagement’ studies.

Table 2. Overview of the findings for antecedents of engagement.

‘Work engagement’ studies

Individual resources/factors

There is strong support demonstrating the positive effects of personal resources, such as self-efficacy and hope (e.g. Airila et al., Citation2014) as well as a wider range of internal states, such as meaningfulness (e.g. Mostafa & Abed El-Motalib, Citation2018) on engagement. There is also moderate evidence that active self-regulatory/coping (e.g. van Loon, Heerema, Weggemans, & Noordegraaf, Citation2018) and goal-directed/self-management (e.g. Breevaart, Bakker, & Demerouti, Citation2014) processes influence the engagement of public service workers. Moreover, there is some evidence that general attitudinal outcomes of engagement, such as job satisfaction, may also act as antecedents, such that there is a reciprocal ‘gain spiral’ effect between engagement and attitudinal outcomes (e.g. Guglielmi et al. Citation2016). This collection of findings derives mainly from, and is in line with, generalized theoretical models/studies of engagement (e.g. the JD-R model; Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008), and so largely comprises a ‘checklist’ of positive individual attributes that may not be specific to the public sector context. Therefore, it is not clear what the practical implications for HRM practice in the public sector are. For example, could these attributes be selected for use within recruitment and hiring decision making processes, or are they more malleable to influence through training and development? If we make the link with findings presented later on in this review, it may be that developmental HRM practices are instead of may be the most appropriate intervention, yet the impact of related interventions may vary depending on contextual factors, such as the nature of the profession and the extent of institutional changes and regulatory requirements (e.g. regarding health and safety).

In terms of motivational elements more commonly associated with the public services environment, there is some evidence that pro-social or public service-driven values/motives (e.g. de Simone, Cicotto, Pinna, & Giustiniano, Citation2016) and intrinsic/autonomous motivational factors (e.g. Tadić, Oerlemans, & Bakker, Citation2017) are linked with higher levels of engagement. For example, there is an emerging yet somewhat fragmented collection of five studies that have focused on public service motivation (PSM), an altruistic form of motivation that connotes a desire and commitment to serve the interests of a community of people rather than just serving one’s self and the organization (Perry & Wise, Citation1990). PSM is widely thought to be multidimensional and to consist of the following core dimensions: attraction to policy making, commitment to public values/doing one’s civic duty, compassion towards those in need/beneficiaries, and self-sacrifice (Breaugh, Ritz, & Alfes, Citation2018).

Collectively, the five studies find support for a positive association between PSM and engagement (e.g. de Simone et al., Citation2016), however there seem to be some complex nuances to this relationship. For example, the type of institution and service provided may be influential. A distinction can be made between people-processing institutions where there is fixed and limited contact with a broad range of service users, such as the police and central/local government, and people-changing institutions where there is intense and longer contact with a specific group of service users, such as schools and hospitals (Hasenfeld, Citation1972). Borst (Citation2018) finds that the relationship between the attraction and commitment dimensions of PSM and engagement are stronger for those in people-processing institutions, whereas the relationship between the compassion dimension of PSM and engagement is stronger for those in people-changing institutions. The latter finding regarding the importance of compassion is also reflected in Noesgaard and Hansen (Citation2018) qualitative study of Danish caregiving organizations. They find compassion to be a key theme underlying the experience of engagement within these healthcare organizations, yet they also highlight a potential ‘dark’ side to the relationship between PSM and engagement as some caregivers, particularly those with high levels of PSM, became too ‘absorbed’ (a core component of work engagement) with their service work, such that their wellbeing was threatened due to enacting detrimental emotional suppression strategies. Overall, whilst it is pleasing to see a small, yet developing stream of studies in this area, there remains a relative silence within the wider engagement empirical literature on attempting to embed/integrate engagement within the PSM literature. Considering that PSM is a mature and important topic within public management/administration research, this seems a worthy gap to address in future research.

Lastly, there was a less comprehensive evidence base regarding the effects of relaxation, recovery, sleep quality, and energy on engagement (five studies: three positive, two weak/mixed); one of these studies however is longitudinal and finds that such effects fade and become non-significant over time (Kühnel & Sonnentag, Citation2011). Similarly, the impact of mindfulness or psychological health interventions on increasing engagement is somewhat questionable, with five (out of seven) studies mostly finding weak or equivocal effects (e.g. van Dongen et al., Citation2016). However, most of these mindfulness/psychological health intervention studies do not fully consider the implications of NPM, such as increased work intensification, on these findings. It may be that these contextual factors place limits on the potential benefit of these types of interventions.

Job resources/demands

It is unsurprising that around half of the ‘work engagement’ studies focus on examining antecedents based on the JD-R model, given its positioning as a foundational model underpinning this perspective of engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008). Although most of this research is undertaken across a range of countries and public service contexts, most are undertaken in public healthcare.

A great deal of support is shown for a positive association between job resources as a collective factor (i.e. comprising a number of different resources) and engagement (e.g. Airila et al., Citation2014). However, studies over multiple time points tend to show more mixed and equivocal findings, such as Ouweneel, Le Blanc, and Schaufeli (Citation2012) who find no significant lagged effects of job resources on engagement six months later. Despite this, there is a range of other studies that broadly show that specific resources, rather than a collective set of resources, have a positive association with engagement, with the most evidence shown for job autonomy (e.g. Borst, Citation2018) and co-worker/social support (e.g. Vera et al., Citation2016); and moderate evidence for opportunities for development/learning (e.g. Bakker & Bal, Citation2010) and skill variety/utilization (e.g. van den Broeck et al., Citation2017). A small number of additional studies examine positive job characteristics from other work design theories/models, such as relational characteristics (Castanheira, Chambel, Lopes, & Oliveira-Cruz, Citation2016). Despite a wide range of support for the notion that job resources help facilitate engagement, the evidence very rarely focuses on delineating and examining sector-specific resources. Hence most engagement research applies a general framework of job resources that tends to focus on job autonomy, co-worker support, and opportunities for development. Differentiating between specific types of resources, such as personal, job, organizational, and relational resources, and examining differences between sectors/institutional settings may also help further advance our contextual understanding of which resources are most important (Fletcher, Citation2017). More specifically, for the engagement of public sector workers, Borst (Citation2018) makes a starting point by positioning autonomy as a public sector-specific resource, which he finds differs in salience for the engagement of public workers across different institutional settings. However, autonomy is well established within general job resource frameworks and therefore a more concerted effort to identify the most salient public sector resources is needed. Moreover, some of the generalized job resources may need to be modified when contextualized to the public sector context, for example professional discretion focuses on how autonomy can be utilized within bureaucratic public institutions (Taylor & Kelly, Citation2006).

Although there is ample evidence regarding the positive effects of job resources, the evidence surrounding the impact of job demands is equivocal, whereby the most persuasive evidence derives from two longitudinal studies, which find that the negative relationship between demands and engagement mostly become non-significant when effects over time are taken into account (Brough & Biggs, Citation2015; Mauno, Kinnunen, & Ruokolainen, Citation2007). Moreover, although a few studies find that the negative relationship between demands and engagement is strongest when resources are scarce (e.g. Hu, Schaufeli, & Taris, Citation2011), some find this interaction to be weak or ‘elusive’ (e.g. Brough & Biggs, Citation2015).

The mixed evidence for the influence of demands may be because not all demands are universally negative, whereby some demands on the one hand are effortful, yet on the other are motivational and enhance engagement. Thus, there is an important distinction between these motivational demands, labelled as ‘challenge demands’, such as increased responsibility, and traditional depleting demands, labelled as ‘hindrance demands’, such as bureaucracy/red tape (Crawford et al., Citation2010). Importantly this distinction has not been considered much within the literature and this issue has been exacerbated by the lack of effort to identify specific public sector demands. Two studies (Tadić, Bakker, & Oerlemans, Citation2015; Tadić et al., Citation2017) do examine the different effects of challenge and hindrance demands, and show that challenge demands are positively related to engagement and strengthen the relations between resources and engagement, whereas hindrance demands are negatively related to engagement and weaken the relations between resources and engagement. Within the context of NPM and austerity, it may be that hindrance demands are likely to be most salient and prevalent in the public sector (Esteve et al., Citation2017; Kiefer, Hartley, Conway, & Briner, Citation2015). Moreover, there may be differing effects when considering a more nuanced classification of resources as Borst, Kruyen, and Lako (Citation2017) find that the positive impact of job-specific resources, such as autonomy, on engagement is strengthened by red tape (a hindrance demand), yet this demand also weakens the positive association between organization-specific resources, such as opportunities for development, and engagement. Further still, some demands may be difficult to categorize or may vary in valence depending on the occupation (Brough & Biggs, Citation2015). This is important when considering different public services as Noesgaard and Hansen's (Citation2018) qualitative study of Danish caregivers reveals that job characteristics associated with the optimization of work processes, helping others, and emotional work elicit both positive and negative perceptions/experiences. This underscores the need for more qualitative studies that help to contextualize and bring attention to factors that may be missed by the dominant deductive quantitative approach within the literature. Bringing these studies together reveals that applying the general principles of the JD-R model to the public sector context is not straightforward and further work is needed to understand these specific complexities.

Lastly, and not surprisingly given the above discussion, there seems to be equivocal evidence regarding the specific positive impact of individual/psychological level interventions where workers are asked to think through and enact changes to their work activities based on the JD-R model of engagement: one study finds positive effects (van Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, Citation2016) whereas three show mixed or equivocal findings (e.g. van Wingerden, Derks, & Bakker, Citation2017). These interventions focus on a bottom-up approach where the individual employee is responsible for enacting actions that focus upon re-designing their own job to better meet their psychological needs. However, as the evidence indicates, whether they can be applied effectively to the public sector is still somewhat unknown. This is further exacerbated as most of these studies are conducted with teachers or healthcare professionals in the Netherlands, which limits our understanding of the impact across cultures and differing institutional settings.

Perceptions of organizational/team factors

A large number of studies, mainly involving healthcare and emergency service workers, find that organizational support factors are positively associated with engagement (e.g. Caesens, Marique, Hanin, & Stinglhamber, Citation2016). However, the majority focus on applying a general understanding of organizational support and social exchange to explain these links. This offers limited insights into the specific mechanisms of support and exchanges of socio-emotional resources within the public sector context. Despite this, some studies have delved deeper into contextualizing this understanding within public services. For example, Brunetto et al. (Citation2017) find some variation in the levels of perceived organizational support between police officers in Australia, USA, and Malta (Australia lowest, Malta highest) as well as differences in how these perceptions are related to engagement across the three countries (i.e. the strength of leader-member exchange and discretionary power as mediators varied between the countries). They argue that these differences may be partly due to the focus and extent of management reforms within respective national contexts of policing. This also relates to the moderate evidence that bullying, harassment, or misconduct have deleterious effects on engagement, and this may be more likely in Anglo-American public sector contexts due to changes in discretionary power and reduced budgets that have, in consequence, damaged the quality of workplace relationships (Brunetto et al., Citation2016). These all point to tensions between the implementation of reformed management systems and practices and public sector workers’ need for professional discretion and value as professionals (Taylor & Kelly, Citation2006), which could be further explored within engagement research.

Related to the quality of workplace relationships, another significant number of studies across a range of public services indicate that workgroups with positive team climates, which share knowledge and are psychologically identified with each other, are likely to be highly engaged (e.g. Barbier et al., Citation2013). Within this category of studies, there appear to be two specific types of climates that may relate more to enabling public sector workers to identify with their workgroup and organization: a service-orientated climate that puts the needs of the service user/beneficiary first (e.g. Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, Citation2012) and a psychologically safe climate that actively monitors and regulates psychosocial risks within the work environment (e.g. Nguyen, Teo, Grover, & Nguyen, Citation2019).

Connected with the idea of fostering positive team climates, another notable collection of studies examines the link between employee perceptions of HRM/organizational practices and engagement across a balanced mix of public services and countries. A few consider the impact of perceptions regarding an overall HRM system or collection of related HR practices, and generally show positive effects on engagement, especially when these practices are contextualized to public services. For example, Luu’s (Citation2019) time-lagged study of Vietnamese public sector legal service workers shows a positive relationship between service-orientated high performance work systems and engagement, whereby this relationship is further enhanced by HRM system strength (i.e. the perceived distinctiveness, consistency, and consensual understanding of what HR practices signify within the organization).

A moderate group of studies focus on employee perceptions of specific HRM/organizational practices, such as flexible work arrangements, rewards, performance management, and voice/participation. Although the majority of these find positive effects, there is evidence, particularly in one study (Conway, Fu, Monks, Alfes, & Bailey, Citation2016), that some HRM approaches associated with modern public sector practices (such as performance management) could have negative impacts on engagement within the public sector due to increased demands to ‘do more with less’. Overall, this body of literature is disappointingly underdeveloped theoretically. It is unclear which specific types of practices, bundles, or systems are most effective, or problematic, in facilitating engagement within the public sector context, and why that may be. Most HRM research on engagement tends to focus upon the psychological processes linking employee perceptions of HRM with employee outcomes, which is helpful for understanding the micro-level foundations of how HRM can shape engagement. However, this focus is not so fruitful at contextualizing HRM and its effects on engagement within the public sector context. Therefore, more effort is needed to connect with the theoretical foundations and literature on HRM practices within the public management/administration discipline (e.g. Boon & Verhoest, Citation2018).

Lastly, there is reasonable evidence to show that individuals who are in alignment with the values and strategic purpose of the organization, and who feel a strong sense of embeddedness in the organization, are more likely to be engaged (e.g. Biggs, Brough, & Barbour, Citation2014). This is underpinned by some additional studies that show the positive effects of justice perceptions on engagement (e.g. Demirtas, Citation2015) and others finding that relational psychological contracts are beneficial for engagement (e.g. Bal, Kooij, & de Jong, Citation2013), although the majority of these are conducted in the public healthcare sector in Germany or the Netherlands. What is missing from this strand of evidence is a focus on public service values and ethos as most of these studies focus on applying general principles of person-environment fit, psychological contract, and organizational justice theories to a public sector sample. More is needed to ascertain the extent to which these theoretical frameworks need to be modified or adapted to more accurately capture cultural/institutional values and strategic aims around serving the community and society.

Overall, studies examining these broader organizational factors associated with alignment/fit with the organization as well as psychological contracts, apply a general social exchange theoretical rationale to explain the link between these factors and engagement. Therefore, this collection of evidence seems to not be specific to the public sector and is largely under contextualized.

Perceived leadership/management

‘Work engagement’ studies focusing on leadership and management factors cover a variety of public sector contexts, although these are somewhat skewed towards healthcare. This may suggest a limitation given that leadership approaches and concepts can differ across sectors/services. A large number show that supportive line management behavior has a significant positive effect on engagement (e.g. Brunetto et al., Citation2017), and there is strong support for the notion that a relational, ethical, and exchange-focused leadership style helps to facilitate the engagement of direct reports (e.g.,Ancarani, Di Mauro, Giammanco, & Giammanco, Citation2018). Collectively these studies also indicate that some specific aspects of supportive leadership behavior are particularly important for the engagement of public sector workers who are facing highly stressful or demanding work environments. For example, Eldor’s (Citation2018) time-lagged study of frontline civil servants in Israel highlights how compassion from supervisors is particularly beneficial for engagement when demands from citizens are high, and Nguyen et al's. (Citation2019) study of Vietnamese public agency workers focuses on the importance of recognition and respect from one’s leader for reducing the negative impact of bullying on engagement. However, we do not know which leadership styles work best in which public sector context. This is a worthy gap to explore as it is likely that the resources needed from a leader may vary depending on the type of service being provided and who the beneficiaries of the service are (Borst, Citation2018). Moreover, there appears to be a lack of connection with the public management literature on the influence of specific management practices adopted as a consequence of NPM reforms (Karlsson, Citation2019).

Organizational/institutional change

This strand of the evidence has started to develop a more advanced understanding of the complexities surrounding the impact of reforms and austerity on work engagement. This is a reassuring sign that some contemporary studies are focusing more upon understanding the contextual factors that may influence engagement. Three studies focus on the broader effects of national governmental reforms: one shows that the implementation of cutbacks (within the Dutch government) may not significantly impact engagement (van der Voet & Vermeeren, Citation2017); another finds that seeking challenges is positively related to engagement within the context of cutbacks in Greece (Petrou et al., Citation2017), and one reveals that cutback-related changes associated with the NPM reform within the UK public sector are linked to decreased engagement (Kiefer et al., Citation2015).

These mixed findings may be better explained by three additional studies that focus more specifically on the organizational level of analysis. In a two-wave survey study of public nurses in Australia, Nguyen, Teo, Pick, and Jemai (Citation2018) show that organizational changes over the past year increased workloads and administration stressors, which promoted cynicism towards organizational change that lead to decreased work engagement six months later. This highlights that individuals’ attitudes and prior experiences of change are also important to consider. Moreover, Noesgaard and Hansen's (Citation2018) qualitative study within three Danish public caregiving organizations reveals that reforms and their subsequent demands may, in some circumstances, have a positive impact on engagement through enhancing opportunities to show compassion and the meaningfulness of one’s work. However, the study also highlights a ‘dark’ side if this causes people to become overwhelmed, particularly when the individual is driven by self-sacrifice, i.e. feel the need to suppress one’s own feelings whilst also expressing a sense of meaning in one’s work.

This ‘double edged’ sword is also reflected in Boumans et al's. (Citation2015) two-year study examining the effects of an innovation project seeking to embed more effective/efficient ways of working within a Dutch public hospital undergoing national institutional reform. The authors found that the engagement levels of those impacted by the innovation project decreased during the period of wider institutional reforms, compared with those not impacted by the innovation project. One potential reason proffered in the study suggests that although nurses worked hard to change and improve their working practices, they felt frustrated and unable to uphold these new standards during a wider period of instability and institutional reform. This underscores the need to understand the specific organizational factors/processes that may help soften the negative impact whilst facilitating positive elements of reforms. It also highlights the necessity for more mixed methods research that longitudinally evaluates programs and changes, given this type of study is the exception rather than norm.

Overall this strand of evidence is still evolving yet constitutes a promising area for future theoretical and empirical research as it has the potential to tease apart the complexities and nuances of the impact of public sector reforms. What makes bringing together evidence on the impact of reforms and changes difficult is the lack of an overarching framework of the socio-political, cultural, and institutional factors that could be coloring the picture.

‘Employee engagement’ studies

Generally, the scope of the above findings is also reflected in the ‘employee engagement’ studies. However, four qualitative studies help to provide more insight into how engagement is managed during periods of public sector change and reform, of which three adopt an ‘engagement as management practice’ perspective. The studies highlight that the managerial approach and organizational methods adopted for engaging employees during a period of cutback-related change and NPM reforms affect how engagement is experienced. For example, communication, mentoring, and voice mechanisms foster reciprocity and personal agency that in turn help facilitate engagement (e.g. Reissner & Pagan, Citation2013). However, Arrowsmith and Parker's (Citation2013) study underscores that these types of ‘engagement practices’ require political astuteness, strategic positioning, and commitment of resources from the HR function to be sustainable. Similarly, the findings from qualitative case studies reported by Davis and Van der Heijden (Citation2018) reveal that personal role engagement can be fostered by idiosyncratic deals (i-deals; special conditions of employment negotiated between an individual worker and their manager/employer) during the challenging period of austerity. However, they also highlight the need for trustworthy and clear communication from managers as not all i-deals are approved and therefore ‘disengagement’ may occur if the employee feels that their psychological contract has been breached. These studies bring nuanced and rich insight into the specific public sector contextual issues that are sometimes overlooked by the more positivistic research paradigm which underpins the ‘work engagement’ perspective. Therefore, it is important that divergent and emergent perspectives of engagement are included and examined alongside the dominant ‘work engagement’ perspective to provide a more rounded overview of the evidence.

Outcomes of engagement

The second research question focuses on clarifying whether engagement leads to desirable public service outcomes. A total of 60 ‘work engagement’ studies and 11 ‘employee engagement’ studies examine the links between engagement and individual or performance outcomes; summarizes these findings. A third of studies looking at individual outcomes and half of the studies focusing on performance outcomes show that engagement mediates the relations between antecedents of engagement and outcomes. Five of these are longitudinal (e.g. Caesens, Marique, et al., Citation2016). Similar to the antecedents section, we focus first on the ‘work engagement’ studies and then outline any additional insights from the ‘employee engagement’ studies.

Table 3. Overview of the findings for outcomes of engagement.

‘Work engagement’ studies

Individual outcomes

Many studies, across a range of countries, find a positive relationship between engagement and job/career satisfaction (e.g. Nguyen et al., Citation2018), and a negative association between engagement and intentions to leave (e.g. Barbier et al., Citation2013), although these studies tend to focus on healthcare and education. However, one of these studies indicates that these relationships may also be curvilinear, such that very high levels of engagement may then be detrimental for retaining staff (Caesens, Stinglhamber, & Marmier, Citation2016). Some studies find positive links between engagement and a wider range of work attitudes and wellbeing factors (e.g. Borst et al., Citation2017; de Simone et al., Citation2016). However, there is generally less conclusive evidence for a link between engagement and negative indicators of wellbeing/health, although two of the seven ‘work engagement’ studies examining this link are longitudinal and show that engagement can reduce mental health problems (*Hakanen & Schaufeli, Citation2012; Simbula & Guglielmi, Citation2013). Given increasing reports of poor morale in the public sector, it is disappointing that we cannot be more conclusive on this point. Overall, these studies reflect an application of general attitudinal/wellbeing frameworks to understanding the outcomes of engagement for public sector workers. More thought is needed to identify the most critical individual outcomes across different public service contexts; for example, it is well known that burnout and sickness/health outcomes are particularly important when looking at public healthcare/emergency services (partly due to the emotional labor and physical demands of this type of work) whereas job satisfaction and organizational commitment are more salient to civil servants and governmental workers (partly due to the ‘employer of choice’ tradition of public sector institutions).

Performance outcomes

There is strong evidence for a positive relationship between engagement and individual level in-role performance (e.g. Luu, Citation2019). There is also a growing amount of evidence to suggest a positive effect of work engagement on organizational citizenship/general contextual performance (e.g. Simbula & Guglielmi, Citation2013), and specific forms of contextual performance such as creativity and proactive behaviour (e.g. Bakker & Xanthopoulou, Citation2013), as well as specific public service outcomes, such as quality of patient care (e.g. Abdelhadi & Drach-Zahavy, Citation2012).

It is somewhat unclear from these studies what the benefits are of having highly engaged staff for the overall quality and effectiveness of public service provision/outcomes, particularly at the organizational/institutional level. No studies seem to compare what is common or what varies in terms of outcomes across different services, particularly given that there may be differences in what types of performance behavior public (versus private) employees perceive as most relevant/critical. It is largely assumed that general work role behavioral models apply similarly to all public services, yet as different public services vary in terms of their beneficiaries and their outputs, it may be important to understand more nuanced connections with outcomes specific to the target beneficiaries, such as quality of patient care for healthcare, student attainment rates and learning outcomes associated with education, or service quality ratings for civil servants. This is concerning given the increasing interest and pressure for public sector organizations, particularly within public healthcare, to clearly capture, audit/monitor, and report on performance-related outputs and outcomes.

‘Employee engagement’ studies

The ‘employee engagement’ studies reflect a similar pattern of findings to the ‘work engagement’ studies for both individual and performance outcomes, yet there is evidence from one study to suggest that proficiency (i.e. in-role) rather than innovative (i.e. specific contextual) behavior is more salient to public sector workers (Eldor, Citation2018).

Understanding differences between the public sector and other sectors

An emerging strand of evidence from 2010 onwards focuses on understanding differences between the public sector and other sectors in relation to the experience of engagement. Whilst only five ‘work engagement’ studies met our inclusion criteria, they do shed light on potential differences. Vigoda-Gadot, Eldor, and Schohat (Citation2013) find that levels of engagement are higher in the public than private sector within the Israeli context, which they rationalize by arguing that the enjoyment of serving society may, in itself, be a particularly strong motivational force. In contrast, Brunetto et al. (Citation2016) find that public sector nurses in Australia exhibit lower levels of engagement than private sector counterparts, which they argue is in part due to the poorer quality of relationships in Anglo-American public sector contexts resulting from changes in the discretionary power of management and reduced per capita spend. This connects with Xerri Farr-Wharton, Brunetto, Shacklock, and Robson’s (2014) and Brunetto et al's. (Citation2018) findings that discretionary power is particularly important for the engagement of public sector (versus private sector) nurses in a range of countries. However, van den Broeck et al. (Citation2017) paint a slightly more complex picture in their study comparing various sectors within Belgium; the public administration/services sector’s profile reflects relatively low levels of demands and resources, and the relationship between three core job resources (social support, autonomy, skill utilization) and engagement may be fairly equal across sectors. Despite this, they do highlight that the public sector context may be different from other sectors in terms of the types of resources and demands that are most relevant. Overall these findings echo those of Borst et al. (Citation2019) meta-analysis, which finds noticeable differences between the public and private sector in terms of the relationships between engagement and work-related attitudinal outcomes, such as job satisfaction and turnover intentions.

Discussion and agenda for future research

This is one of the first review papers to systematically synthesize the evidence on employee engagement in the public sector. In doing so, we have moved away from previous engagement reviews (e.g. Bailey et al., Citation2017; Crawford et al., Citation2010) which aimed to identify universal mechanisms regarding employees’ experience of engagement, to develop a more nuanced understanding of the meaning and mechanisms surrounding engagement in one particular context. Our paper therefore makes a key contribution to engagement theory, which – similar to other research domains in organizational behavior and human resource management – has not sufficiently incorporated a contextual perspective to understand how specific characteristics of the macro-level environment influence individual motivation at work (Johns, Citation2006). In particular, by focusing our review on the public sector, this paper demonstrates that context matters for engagement theory and practice in a number of different ways. First, our review has highlighted that engagement in the public sector differs from the private sector with regards to its motivational implications. This is because public sector research has for a long time demonstrated the relevance of PSM as the key motivational concept for public sector employees, and a theory of engagement for the public sector therefore needs to consider the motivational effects of engagement alongside PSM. Second, our review has demonstrated that the relative importance of engagement drivers differs substantially between public and private sector contexts. For example, prosocial motives were found to be an important antecedent of engagement in the public sector. Additionally, our review showed that generalized constructs/models may not be readily applied to the public sector context and may need to be modified to better fit the institutional logic and bureaucratic environment of public organizations, such as adapting the concept of job autonomy to align more with the notion of professional discretion. By paying attention to the context when specifying the drivers of engagement we add to theoretical clarity and enable public sector managers to make correct assumptions about the management of engagement amongst their workforce. Third, our review has also demonstrated that the public sector itself is not a homogenized sector allowing uncritical application of research findings. The public sector and the nature of engagement are shaped by a range of cultural, regulatory and institutional factors as well as the types (e.g. supervisory support) and levels (e.g. organizational-level versus job-level) of resources that are relevant to this specific context thereby influencing the relationships between antecedents of engagement, engagement and its outcomes. Our review therefore highlights the need to incorporate contextual dimensions in the analysis and understanding of micro-level relationships and to move away from a generalization of research findings on engagement across sectors and industries to a much more specific contextual understanding about how engagement unfolds in specific research settings.

Based on the key gaps and issues identified within the review, we now turn to presenting a more in-depth agenda for future research that seeks to advance engagement research within the public sector context structured around the following six research questions.

How is engagement related to PSM within the public sector?

The first research question seeks to advance our understanding of the relationship between engagement and PSM, considering we found only a small number of studies that have empirically examined the link between the two. Public management research has long focused on PSM, and the desire of public employees to serve the public interest and improve the wellbeing of society (Perry & Wise, Citation1990), yet the current environment of “doing more with less” places extra demands on public service employees at a time of diminishing resources, which could limit the extent to which PSM may be beneficial to public organizations (Esteve et al., Citation2017). Given that Bakker (Citation2015) proposes that PSM moderates the relationship between job resources and engagement for public service workers and recent studies (e.g. Noesgaard & Hansen, Citation2018) highlight the specific role of compassion (a core dimension of PSM) in facilitating engagement, it is important that more empirical work is conducted to tease out the precise relations between PSM and engagement within highly demanding work environments. Some attempts have been made to begin this process of understanding the distinctions and relations between PSM and engagement. For example, Breaugh et al. (Citation2018) argue that PSM is a dispositional/values based motivational construct that is forward-looking and focused on achieving end goals, whereas engagement connotes a more fluctuating/phenomenologically based motivational concept that takes a present-perspective and describes how employees become immersed in their immediate tasks. It is therefore critical to understand whether public service employees can be simultaneously motivated by their dedication to public service (PSM) and their dedication to the job (engagement), or whether one source of motivation dominates or “crowds out” the other source of motivation.

How can a contextual understanding of the JD-R model and related theories be further advanced with respect to public services?

Given that the weight of evidence draws on one specific theoretical perspective, i.e. Schaufeli et al's. (Citation2002) work engagement construct and the associated JD-R model, it has become obvious that the distinction between challenge and hindrance work demands, as well as types of resources, and their effects on engagement still needs further research and adaptation to public services. More specifically, not enough has been done to identify which types of job resources/demands across different public services are likely to be the most salient, and consequently the effectiveness of potential interventions geared towards raising engagement levels cannot be fully evaluated. Additionally, there is a lack of contextualization when applying other general psychological, relational, and leadership models/theories, such as social exchange theory. Although recent work by Borst (Citation2018) extends the J-DR model by applying institutional logics and Brunetto et al. (Citation2017) provide a more nuanced understanding of social exchange relationships within the public sector context, there is a need to connect more with broader structural/sociological theories and models within the public management and HRM literature, such as that on professionalism and professional discretion (Taylor & Kelly, Citation2006). We therefore encourage HRM scholars to focus on comparing the experience of engagement across different contexts to further specify resources/demands that are most salient in various public services. Johns (Citation2006, p.391) provides a useful initial framework to better categorize different elements of what he refers to as ‘omnibus’ context, i.e. the who, what, when, where and why. Importantly, Johns’ (2006) framework offers opportunities to advance multilevel, case study, and intervention-based research designs by enabling key contextual factors to be analyzed alongside psychological and work environmental features; research by Jenkins and Delbridge (Citation2013) provides an illustration of how a contextual approach to studying engagement can be undertaken within the HRM discipline. We would also encourage engagement researchers to consider how to capture some of these wider contextual features when conducting data collection activities so that these can be at least reported on when contextualizing the study; for example, Fletcher’s (Citation2017) qualitative study exploring the situational context of personal role engagement also considered variation across different organizational settings.

How is engagement within the public sector shaped by cultural, socio-political, and institutional factors?

We have made a first step with our review towards putting engagement in context, yet it is clear that the current evidence base does not fully consider the cultural, socio-political, and institutional contextual factors surrounding the public sector and public services. Therefore, we encourage further research that focuses on these dimensions of context.

Focusing on the cultural or societal context, the current evidence base is founded principally on studies conducted in Europe. Despite an increase in studies from a wider range of countries, there are still relatively few that compare data from different countries that represent a variety of public service systems. National cultures and values, political structures and ideologies, and economic activities are all likely to influence the way in which public service work is designed, organized, and perceived (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, ideals of public service vary across different international contexts in terms of ideological positions on the role of government in serving public interests. Therefore, the dynamics and processes of engagement for public employees are likely to vary across countries, which raises the question of whether the antecedents, experience, and outcomes of engagement are applicable to those countries that are culturally and politically very different from those in Europe. Given that HRM scholars have started to highlight the variation in relevance, meaning, and experience of engagement across cultures (Rothmann, Citation2014), this underscores the need to examine the cultural context in more depth, and as such, engagement studies should consider the different cultural concepts that exist in public sectors around the world.

When looking at the socio-political context, the question arises of how engagement can be facilitated given the marketization of public services globally? Driven initially by the emergence of NPM and the widespread adoption of private sector management practices (Verbeeten & Speklé, Citation2015), and exacerbated by the current climate of austerity (Esteve et al., Citation2017), a commodified model of public sector employment based on the production of manufactured goods and internal performance efficacy is increasingly being embraced by many countries. The extent to which such reforms and changes within HRM functions impact on the engagement and motives of public sector workers is worthy of much greater attention. In particular, examining how reforms are implemented and the attributions that public sector workers have about these would be useful as such studies would uncover design and process issues that threaten engagement. An important consequence of marketized public service delivery is how public workers delivering the same service may be employed under differing work conditions (e.g. pay), which can have depletive effects on work motivation, particularly as it may undermine the quality of workplace relationships.

Regarding the institutional context, there is a need for engagement research to better understand the complexity, diversity and increasing fluidity of institutional structures and forms within the public sector. For example, many public organizations are changing to become a hybrid of different forms with varying levels of co-production, co-creation, and delegation of services (Voorberg, Bekkers, & Tummers, Citation2015). This increasing hybridity may have implications regarding how employees experience engagement, particularly as these different configurations may align to a greater or lesser extent with the values and motives of public service work as well as their sense of professionalism. Within the UK context, Reissner and Pagan (Citation2013, p.2755) highlight the issue that fostering engagement in a public-private partnership, i.e. a hybrid institutional form, is not straightforward as many employees “find it difficult to accept [the partnership’s] private-sector ethos, culture, and working practices”. Therefore, future research should compare the experience of engagement within public sector organizations with varying degrees of hybridity to better understand how HRM strategies and practices may need to adapt to suit these different organizational forms.

What might be the potential “dark” side to engagement within the public sector?

The fourth question examines a neglected, yet vital perspective on engagement that is particularly relevant in light of the contextual changes surrounding the public sector. The engagement discourse among scholars and practitioners is traditionally centred on a “prescriptive and normative ‘managerialist’ approach” (Valentin, Citation2014, p.478). This promotes a transactional, rose-tinted view that what is good for the organization is good for employees. As such, engagement fits with the dominant discourse surrounding NPM and liberalized public services (Verbeeten & Speklé, Citation2015) that considers important motivational characteristics of public sector work as “transactional commod[ities]” that are fundamentally externally controlled (Bargagliotti, Citation2012, p.1416). Thus, the dominant view that an individual freely chooses to engage may fail to fully consider the complexities of the employment relationship, particularly within the public sector. Importantly, HRM scholars have criticized engagement research for promoting a rather unitarist, psychologized, and acontextualized view of the employment relationship (Guest, Citation2014; Keenoy, Citation2014; Purcell, Citation2014). It is therefore no surprise that the ‘added value’ of engagement has been questioned as its positioning as a universal positive psychological experience that can be managed and controlled seems to overlap with more general work-related attitudes that can be subsumed within a Taylorist approach to management (Keenoy, Citation2014). Thus, it is important that HRM scholars interested in understanding the complexities of engagement should situate their study more carefully within a pluralistic and contextualized perspective. Furthermore, these issues highlight a need to explore engagement from a more critical perspective that can uncover the “dark” side to engagement. For example, it would be fruitful to examine engagement from a diversity and inclusion perspective given that we find virtually no studies that have considered this within the public sector context, even though it is well known that the public sector ethos in many countries emphasizes diversity and inclusion as part of the public sector’s ‘employer of choice’ tradition and values around representing/serving society.

How do the antecedents and outcomes of engagement vary across different services and modes of service delivery within the public sector?

A fifth question arises from the diversity of services and modes of delivery across the public sector. Few, if any, studies specifically adopted a public service focus; rather, the emphasis tended to be on the group of workers or on the occupation, thus suggesting that a theoretically coherent body of evidence specific to the public sector is lacking. This is of concern, as there may be important nuances and differences in the experience of engagement between the public sector and other sectors (Vigoda-Gadot et al., Citation2013; Xerri, Farr-Wharton, Brunetto, Shacklock, & Robson, Citation2014) as well as across different types of public institution/services (Borst, Citation2018). Moreover, most studies examining the outcomes of engagement focus on individual level behavioral indicators, and so did not necessarily focus on public service outcomes that may be particularly important or unique to the public service setting under investigation. Studies within HRM should focus more on comparing engagement across different public service settings to understand which factors are important in one type of service setting, for example in public education, and which are more common/universal across many types of services. Borst’s (Citation2018) study applying institutional logics to differentiate people-processing and people-changing public organizations may provide a useful starting point to understanding the unique characteristics and public service outcomes within each type of public service setting.

How can engagement research better connect with the practical concerns and initiatives within public organizations?