Abstract

Research on the ‘new career’ has explored some individual correlates of protean and boundaryless career orientations while largely neglecting their consequences for organizations. Our paper addresses this omission by exploring the link between ‘new career’ orientations and both positive and negative extra-role behaviours based on the argument that these dimensions of performance are potentially more variable given their volitional nature. In addition, it explores the role of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support in shaping this relationship. We present the results of a study with 641 employee-supervisor dyads in nineteen organizations showing that a protean career orientation results in more positive extra-role behaviours, whereas a boundaryless career orientation is associated with less citizenship behaviour and higher deviant behaviour due to its negative impact on commitment. In addition, our findings suggest that organizations can positively influence the behaviour of individuals with high boundaryless career orientations by offering high levels of support.

Introduction

Over the last two decades a growing literature has proclaimed the demise of traditional organizational careers and the rise of ‘new’ independent and self-driven careers. While inter-organizational and self-driven careers have always existed and were arguably even dominant for many types of worker, the contrast with the ‘old’ organizational careers reflects their increasing salience among those traditionally offered stable employment and opportunities for hierarchical progression. These career patterns have been captured, among others, by the notions of the protean and the boundaryless career. The protean career orientation captures a preference to take control and ownership over one’s career (Briscoe et al., Citation2006) while the boundaryless career orientation highlights an increasing preference for a career that physically and psychologically transcends organizational boundaries (Sullivan & Arthur, Citation2006). This literature has focused mainly on describing and operationalizing the protean and boundaryless career (Arthur, Citation2014; Baruch, Citation2014; Briscoe & Hall, Citation2006; Inkson, Citation2006); debating their usefulness to capture contemporary career experiences (Inkson et al., Citation2012; Rodrigues & Guest, Citation2010); and, more recently, exploring their implications for individuals. Evidence suggests that the protean orientation is associated with high career, job and life satisfaction (De Vos & Soens, Citation2008; Grimland et al., Citation2012; Rodrigues et al., Citation2015), high psychological well-being (Briscoe et al., Citation2012) and adaptability to changing labour market circumstances (Chan et al., Citation2015). The individual outcomes of the boundaryless career orientation are less clear. One study reported a positive association with career satisfaction (Culié et al., Citation2014) but another found a range of negative outcomes for employees (Rodrigues et al., Citation2015). What we know less about are the consequences of both orientations for organizations seeking to engage and motivate employees.

The aim of this paper is to evaluate elements of the ‘new career’ exchange and, more specifically, its impact on dimensions of employee behaviour that are relevant for organizations. Specifically, our paper explores the extent and circumstances under which ‘new career’ orientations influence the display of organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours. Research has paid increasing attention to the implications of the display of positive and negative employee voluntary behaviours that go above and beyond task performance (Dalal, Citation2005; Podsakoff et al., Citation2014; Vigoda-Gadot, Citation2007). Positive voluntary behaviours, often labelled organizational citizenship behaviours, have been defined as ‘constructive behaviours that support the social and psychological environment in which task performance takes place’ (Organ, Citation1988, p. 4). These include, for example, defending the organization in public and helping co-workers complete their tasks. In contrast, workplace deviant behaviours ‘violate[s] significant organizational norms and, in so doing, threaten[s] the well-being of the organization or its members, or both’ (Bennett & Robinson, Citation2000, p. 349). Examples of workplace deviant behaviours include deliberately taking longer than needed to complete a task and embarrassing colleagues in public. While organizational citizenship behaviours have been consistently associated with positive organizational outcomes, such as financial and operational performance and customer satisfaction (Podsakoff et al., Citation2000, Citation2014), research has shown that workplace deviant behaviours carry important operational and financial costs (Cohen, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2015).

There are three reasons to focus on extra-role behaviours. First, we might anticipate that ‘new career’ orientations will not negatively affect in-role behaviours as those engaging in independent careers will need to maintain their employability. This is corroborated by Baruch (Citation2014), Briscoe et al. (Citation2012) and Rodrigues et al. (Citation2015) who generally found a positive association between protean and boundaryless career orientations and task performance. However, research has not extended to explore any positive or negative effects on the more discretionary extra-role behaviour. Second, research has shown that organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours can be as important as task performance in determining employee overall job performance (Dunlop & Lee, Citation2004). Podsakoff and colleagues (2000), for instance, reported that organizational citizenship behaviours accounted for nearly 43% of the variance in performance evaluations, while task performance contributed with only 9.5%. In understanding the implications of contemporary career orientations for organizations it is therefore important to consider their impact on extra-role behaviours. Finally, these more volitional extra-role behaviours are not necessarily a part of explicit role expectations (Spector & Fox, Citation2010) so they provide good illustrations of how strongly motivated individuals are to contribute to the organization. However, this can work two ways. First, it is possible that those pursuing independent careers and giving primacy and commitment to pursuing their own career goals rather than identifying with an organization feel less inclined to go beyond their job requirements to benefit their employer and other employees. Second, as Baruch and Vardi (Citation2016) further highlight, the pressure and the stress associated with taking responsibility for one’s career development and continuously seeking new opportunities in the labour market may lead individuals to engage in deviant behaviours. If personal goals are thwarted, creating perceptions of unfairness and dissatisfaction with desired outcomes (Cohen-Charash & Mueller, Citation2007) then the probability of engaging in such behavior is potentially enhanced. An evaluation of the impact of ‘new career’ orientations on these volitional dimensions of employee performance as well as key features of organizational life that potentially influence this association is therefore timely.

Our paper reports the findings of a study conducted among 641 employees and respective supervisors in 19 organizations and makes four contributions to the literature. First, we explore the link between protean and boundaryless career orientations and supervisor ratings of employee organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours. In so doing we integrate contributions from career theory with research on the antecedents of extra-role behaviours which has thus far focused on the role of individual differences, task characteristics and organizational factors (Dalal, Citation2005; Podsakoff et al., Citation2014). Second, we explore key organizational factors that might help to explain any link between ‘new career’ orientations and key dimensions of employee behaviour. We therefore go beyond the focus on agentic careers that has dominated the literature over the last decades (Akkermans & Kubasch, 2017) and has been criticized for neglecting the context in which careers are enacted (Forrier et al., Citation2009), and bring back the role of the organization as a key arena in which careers continue to unfold. Specifically, we explore the role of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support in shaping organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours among individuals with high protean and boundaryless career orientations. Thirdly, our study contributes by exploring differences between protean and boundaryless career orientations and, more specifically, the extent to which they have a differential impact on positive and negative behaviours. Finally, we achieve these aims within an analytic framework that draws on social exchange theory and seeks to discuss how the provision of organizational support influences the behaviour of individuals pursuing independent careers.

Theoretical framework

Our model is informed by contributions from the literature on career orientations and social exchange theory. The former provides a rationale for understanding how the behaviour of individuals with ‘new career’ orientations is perceived by their supervisors. In turn, social exchange theory offers a framework to discuss how organizations can manage the attitudes and behaviour of those pursuing independent careers.

Protean and boundaryless careers have mostly been discussed as orientations. Career orientations are ‘relatively stable career preferences emerging inter alia from the interaction between self-identify, family relationships, social and cultural background, education, work experiences and labour market conditions’ (Rodrigues et al., Citation2013). While we lack a comprehensive theory and empirical exploration of the process of development and maturation of career orientations, the extant literature proposes that orientations develop as people experience work and identify and gravitate towards contexts that suit their values, goals and preferences (Feldman & Bolino, Citation1996). Career orientations, as Schein suggests ‘increasingly become a stable part of the personality’ (1980, p. 21) and can be associated with enduring patterns of career attitudes and behaviour.

There are good reasons to consider that an association between protean and boundaryless career orientations and extra-role behaviours exists. In contrast with task performance, which requires both ability and motivation, ‘the performance of discretionary work behaviours (…) is viewed primarily as a motivational phenomenon’ (Hoffman et al., Citation2007, p. 556). This suggests that work and career-related values and preferences should be more strongly associated with organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours than with job performance.

The first aim of the paper is then to identify any differences in both positive and negative supervisor rated extra-role behaviours associated specifically with holding protean and boundaryless career orientations. A key assumption in the contemporary career literature is that those with ‘new’ career orientations are mostly committed to their own careers and potentially less motivated to invest in their organization with potential implications for the display of both positive and negative extra-role behaviours. It is, however, possible to expect important differences in the behaviour of individuals with high protean or high boundaryless career orientations. While both concepts are often used interchangeably in the literature (Uy et al., Citation2015), they capture quite different preferences and, potentially, behavioural patterns. This is also suggested by Wiernik and Kostal’s (Citation2019) review and meta-analysis showing that self-directed career management and organizational career mobility preference are distinct constructs. The key feature of a protean career is freedom and self-direction (Briscoe & Hall, Citation2006) and when this is experienced, a self-managed career is not incompatible with a traditional organizational career. In contrast, the boundaryless career is mostly understood as one ‘that involves physical and/or psychological career mobility’ (Sullivan & Arthur, Citation2006, p. 22) and typically involves lower levels of organizational attachment.

A second aim of the paper is to understand the processes through which protean and boundaryless career orientations are associated with the display of extra-role behaviours. We propose to explore the role of organizational commitment in shaping this relationship. The focus on commitment is justified in light of the argument that attachment to an organization is being replaced by a focus on personal career values and priorities (Arthur, Citation1994). In addition, research on extra-role behaviours also highlights the importance of commitment as a key antecedent of organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours (Spector & Fox, Citation2010). We will therefore consider the mediating role of organizational commitment in the link between contemporary career orientations and extra-role behaviours.

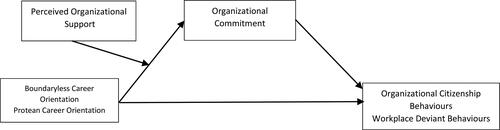

The final key aim of the paper is to discuss the implications of contemporary career orientations for organizations and, more specifically, how they can mitigate any potential negative impact of contemporary career orientations on relevant dimensions of employee behaviour. In doing so, we highlight the potential importance of the organizational context in which careers unfold and in which employees may engage in extra-role behaviours. The dominant theoretical framework informing our understanding of extra-role behaviours is social exchange theory. While there isn’t a unified theory of social exchange, social exchange theories spanning a number of social science disciplines, including management and social psychology, share a number of important common features that are useful to explain the transactions between two parties (Cropanzano et al., Citation2017). In general, social exchange theory proposes that in the employment relationship, informal social and implicit exchanges develop. In contrast with a purely economic exchange, social exchange requires trust and some flexibility. Social exchanges are based on the existence of a norm of reciprocity whereby individuals feel obliged to reciprocate organizational investments in some way. The implication is therefore that greater investment in supporting employees will be reciprocated with attitudes and behaviours valued by the organization, including commitment and performance. We propose that providing perceived organizational support to those with contemporary career orientations may lead to the display of higher levels of commitment and, subsequently, to positive extra-role behaviours. The converse is that low levels of support may result in low commitment and the risk of workplace deviant behaviour. Our choice is justified by evidence suggesting that perceived organizational support is an important antecedent of commitment (Meyer et al., Citation2002) and a key argument in the talent management literature suggesting that organizations still recognize the value of developing and retaining employees and may use a range of policies and practices, including offering high levels of support, to generate commitment and desired employee behaviours (Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009). Perceived organizational support reflects employees’ perceptions about the extent to which their organization is committed to them and offers support in times of need (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002). We argue that organizational support might encourage those holding contemporary career orientations to become better organizational citizens and to avoid infringing important organizational rules. Our model is depicted in . Next, we offer a more detailed discussion of the propositions underpinning our model.

The link between ‘new career’ orientations and extra-role behaviours

While it is generally accepted that a negative correlation between organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours exists, and that individuals likely to engage in one form of extra-role behaviour are less likely to engage in the other, this seems to be an over-simplification. As Spector and Fox (Citation2010) observe, several studies show no relationship or even a positive association between both forms of extra-role behaviour (Dalal, Citation2005). It is therefore possible that people engage in both, either or neither form of extra-role behaviour depending on individual characteristics and perceptions of the state of the deal at work. Bearing this evidence in mind we will discuss the link between ‘new career’ orientations and extra-role behaviours.

Individuals pursuing high physical and psychological career mobility are mainly committed to their own career values and goals (Sullivan & Arthur, Citation2006). Given the transactional nature of their association with any one organization, we argue that they should be focused on meeting explicit role expectations, reflected in job performance, as a way of maintaining external employability and not to engage in any form of extra-role behaviour. Bolino et al. (Citation2016) have suggested that organizational citizenship behaviours are often driven by selfish interests, such as impression management. Research shows that managers typically use them as an indicator of employee motivation and incorporate them in their performance evaluations and recommendations for reward allocations (Vigoda-Gadot, Citation2007). As such we propose that individuals with a high boundaryless career orientation should lack motivation to run the extra mile to benefit their employer and co-workers given that the rewards associated with being a good organizational citizen are uncertain, deferred in time and potentially of higher valence for people who are more inclined to make long-term investments in their relationship with their employer (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002).

In addition, we argue that individuals with a high boundaryless career orientation will also be unlikely to engage in deviant behaviours. There are two reasons for this. First, workplace deviance is often a response to perceptions of organizational injustice or breach or violations of the psychological contract (Dunlop & Lee, Citation2004). Engaging in many forms of deviant behaviour requires motivation and effort to either actively fail to conform to organizational norms or to act against the organization and/or its workers (Bennett & Robinson, 2000). Research further indicates that the display of deviant behaviours does not typically occur in a vacuum. Rather, they are enacted in a context where individuals are deeply embedded in their organizations and feel that shared norms, values, beliefs and expectations about the employment relation were unmet or broken (Fida, Paciello, Tramontano, Fontaine, Barbaranelli & Farnese, Citation2015). This does not seem to be the case of individuals with a high boundaryless career orientation who traditionally have weaker relational ties with their organizations and may, as a result, have lower expectations about the employment relationship when compared with those pursuing stable careers within an organization. They are therefore potentially less sensitive to – or have lower expectations about - organizational inducements which reduces the potential for psychological contract breach and its negative behavioural consequences. Second, research shows that deviant behaviours are often viewed as the most important factor of overall job performance (Rotundo & Sackett, Citation2002). Given that developing a reputation as a top performer to maintain external employability is key for those seeking inter-organizational career mobility, we argue that they might avoid engaging in deviant behaviours that damage their reputation. We propose that:

Hypothesis 1: The boundaryless career orientation will be negatively associated with organizational citizenship behaviours and with workplace deviant behaviours.

In contrast, we expect people with a high protean career orientation to engage in organizational citizenship behaviour and avoid deviant behaviour. A relationship between proactive behaviours and organizational citizenship behaviour has been proposed on the grounds that proactive employees are more motivated to participate in organizational improvement initiatives (Jawahar & Liu, Citation2016). Since the protean career is not necessarily associated with inter-organizational career mobility (Wiernik & Kostal, Citation2019), we argue that individuals might use their proactivity and self-direction to craft their jobs and careers in the context of their current organization and see value in the type of rewards commonly associated with being a good organizational citizen.

In addition, research shows that workplace deviance stems from a range of individual and contextual sources, including being low on conscientiousness and emotional stability (Colbert et al., Citation2004), feeling stressed and not being in control over one’s work (Fida et al., Citation2015). Given that protean careers are fostered by continuous learning and adaptability, proactivity and self-direction (Sullivan & Arthur, Citation2006) we would expect them to be associated with higher perceptions of ownership and control as well as higher levels of satisfaction with one’s work and career therefore resulting in a negative association with deviant behaviours. We propose that:

Hypothesis 2: The protean career orientation will be positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviour and negatively associated with workplace deviant behaviour.

The mediating role of organizational commitment in the link between ‘new career’ orientations and extra-role behaviours

The association between organizational commitment and extra-role behaviours has been extensively discussed and reported in various reviews and meta-analyses (see, for instance, Lee et al., Citation2015; Meyer et al., Citation2002; Riketta, Citation2002). While Spector and Fox (Citation2010) suggest that organizational citizenship behaviour and workplace deviant behaviour are not necessarily opposite forms of voluntary active behaviour, the overall evidence points to a positive association between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour and a negative link with workplace deviant behaviour.

In turn, the ‘new career’ literature is underpinned by the idea that individuals are replacing commitment to their organization by commitment to their own career values and goals (Arthur, Citation1994; Briscoe et al., Citation2006). However, there may be differences in the readiness to display commitment between those with high boundaryless and protean career orientations. The boundaryless career orientation has been consistently associated with lower commitment and higher intention to quit the organization (Çakmak-Otluoğlu, Citation2012; Porter et al., Citation2016). This can be explained by the nature of the orientation with its focus on external employability and inter-organizational career mobility. In contrast, the protean career ‘may not affect organizational commitment negatively’ (Gubler et al., Citation2014a, p. 28). While the evidence is not always consistent, Baruch (Citation2014), Çakmak-Otluoğlu (Citation2012) and Porter et al. (Citation2016) for example have reported positive associations between the protean career orientation and organizational commitment. This is in line with research on proactivity showing that those who are more proactive in managing their careers not only report higher levels of fit with their job and organization (Sylva et al., Citation2019) but also higher levels of organizational, team and career commitment (Belschak & Hartog, Citation2010). Hence, while a boundaryless career orientation may have a negative impact on organizational citizenship behaviour and a positive association with deviant behaviour via its association with lower commitment, the protean career orientation may have a beneficial impact on extra-role behaviours through its association with organizational commitment. We therefore propose that:

Hypothesis 3a: The boundaryless career orientation will be negatively associated with organizational citizenship behaviour and positively associated with workplace deviant behaviour via organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3b: The protean career orientation will be positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviour and negatively associated with workplace deviant behaviour via organizational commitment.

The moderating role of perceived organizational support in the link between ‘new career’ orientations and organizational commitment

A key aim and contribution of our paper is to take into account the context in which careers are enacted and, more specifically, to discuss how organizations influence the display of extra-role behaviours among those with high protean and boundaryless career orientations. Organizations should be interested in managing the attitudes and behaviours of individuals with ‘new’ career orientations, particularly if they possess valuable human capital and are at a higher risk of underperforming and/or quitting.

One way in which commitment can be gained is by demonstrating high levels of organizational support. Despite the proclaimed challenges to the traditional employment relationship and organizational careers, key assumptions in the HRM literature suggest that gaining employees’ commitment remains an organizational priority (Mostafa et al., Citation2019). Organizational support reflects employees’ beliefs about the extent to which the organization values their contribution, considers their socio-emotional needs and delivers on promised rewards (Rhoades et al., Citation2001). Evidence shows that organizational support will be perceived as more valuable when it is discretionary rather than the result of formal negotiations (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002) and extensive research has shown that it leads to a range of positive individual and organizational factors, including job satisfaction, employee commitment, retention and performance (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). What we know less about is the extent to which organizational support generates commitment among individuals with ‘new career’ orientations.

Research shows that individuals who are more proactive and rely on their own agency to develop their careers not only report higher expectations about organizational support in attaining their work and career-related goals (De Vos et al., Citation2009) but also experience higher levels of support (Sturges et al., Citation2002). In fact, as shown by De Vos and Buyens (Citation2005), career self-management and organizational career management are not substitutes for each other – both are relevant to achieving positive individual and organizational outcomes. Therefore, while it is possible that people with high protean and boundaryless career orientations may place a lower value on traditional organizational rewards such as job security and the prospect of organizational career progression, they should nevertheless expect organizational support in achieving desired career goals which might be idiosyncratic and include, among others, developing marketable skills and opportunities for job and career crafting. In turn, and as long as they believe they are receiving enough support, they are likely to reciprocate by displaying higher levels of commitment as a path to positive extra-role behaviours. We therefore propose that:

Hypothesis 4: Perceived organizational support moderates the association between a) the boundaryless career orientation and b) the protean career orientation and organizational commitment such that the association is more positive at high levels of perceived organizational support.

Finally, our model implies a pattern of moderated mediation whereby the mediating effect of organizational commitment in the link between boundaryless and protean career orientations and extra-role behaviours depends on the level of perceived organizational support. We argue that organizational support is an important boundary condition mitigating any potential negative impact of contemporary career orientations on extra-role behaviours, particularly among those with a high boundaryless career orientation, and enhancing the expected positive effect of the protean career on contextual performance via its effect on organizational commitment. We therefore additionally explore the extent to which perceived organizational support moderates the indirect effects of contemporary orientations on organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours.

Hypothesis 5: The conditional indirect effects of a) the boundaryless career orientation and b) the protean career orientation on extra-role behaviours via commitment will be more positive for organizations (i.e. more positive association with organizational citizenship behaviours and more negative association with deviant behaviours) at higher levels of perceived organizational support.

Methods

Sample and procedure

Data were collected through a questionnaire from a sample of 641 workers and respective supervisors in 19 private organizations in Portugal who responded to an invitation to participate in our study. Organizations were contacted via a university’s alumni network. Participant organizations were from a broad range of sectors and ranged in size from under 50 to over 3000 employees. A researcher visited all organizations, distributed the questionnaire and informed all those who agreed to participate of the aims of the study. Participants were asked to identify their immediate supervisor. Supervisors received a questionnaire asking them to provide information about the behaviours of subordinates who agreed to participate. Confidentiality was assured to all participants and subordinates and supervisors did not have access to each other’s responses. The mean age of subordinates was 36.4 years (SD = 10.3). 369 (56.1%) participants were men and 368 (55.9%) had partners. Mean job tenure was 5.7 years (SD = 6.3). 496 (79.7%) respondents were permanent workers and 50 (8.1%) worked part-time.

Measures

Validated measures of all constructs were used. Unless otherwise stated, responses to all items were obtained using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1= strongly disagree’ to ‘5 = strongly agree’. Items were translated from English to Portuguese and then back-translated by independent bilingual translators. Unless otherwise stated, validated measures of all constructs were used although in some instances the number of items in specific measures were reduced to meet the concerns of participating organizations about the length of the questionnaire. All measures present good reliability (see ).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities and correlations between study variables.

Self-report measures

Organizational commitment was measured using three items from Meyer and Allen’s (1997) measure of affective commitment. A sample item is ‘I do not feel a strong sense of ‘belonging’ to my organization (R)’

Perceived organizational support was measured using three items from the measure developed by Eisenberger et al. (Citation1986). Sample items is ‘My organization takes pride in my achievements’.

Boundaryless career orientation was measured with the four highest loading items from Briscoe et al. (Citation2006) career mobility preference scale. A sample item is ‘I like the predictability that comes with working continuously for the same organization (R)’. A decision was made not to use the boundaryless mindset scale. This measure focuses on people’s attitudes towards working across organizational boundaries (e.g. with people in different departments, functions and organizations) and is arguably less relevant for capturing the core meaning of the boundaryless career as defined by Arthur (Citation1994). In addition, it is not clear how it resonates among people working in SMEs (which comprises many of our participants) where boundaries between jobs and departments are often unclear.

Protean career orientation was measured with the four highest loading items from Briscoe et al. (Citation2006) self-directed career management scale. A sample items is ‘Overall, I have a very independent, self-directed career’. We have not used the values driven scale as evidence suggests that it is problematic in non-US samples (Baruch, Citation2014).

Supervisor ratings of employee behaviours

Organizational citizenship behaviours were measured with four items of the measure of OCB directed towards the organization developed by Lee and Allen (Citation2002). A sample items is ‘This employee attends functions that are not required but that help the organizational image’.

Workplace deviant behaviours were measured with four items from Bennett and Robinson (Citation2000) measure of organizational deviance directed towards the organization (2000). A sample items is ‘This employee has taken additional or longer breaks than is acceptable at his or her workplace’.

Analyses and results

Analyses

Data were analysed using structural equation models in Mplus, version 7. To test for direct and conditional effects we have calculated 95% confidence intervals.

Means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations

The means, standard deviations, reliabilities and correlations of the study variables are presented in . Overall, participants report moderate protean career orientations (Mean = 3.61; SD = .61) and somewhat lower boundaryless career orientations (Mean = 2.76; SD = .71). Supervisors report moderate levels of organizational citizenship behaviour (Mean = 3.57; SD = .75) and low levels of workplace deviant behaviour (Mean = 1.87; SD = .71). As expected, the boundaryless career orientation is negatively correlated with organizational commitment (r = −.27; p < .01). The correlations with organizational citizenship behaviour (r = .04; ns) and workplace deviant behaviour (r = −.06; ns) are both non-significant. In contrast, the protean career orientation is positively associated with organizational commitment (r = .26; p < .01) and organizational citizenship behaviour (r = .17; p < .01) and negatively associated with workplace deviant behaviour (r = −.14; p < .01). The correlation between organizational commitment and perceived organizational support is positive as expected (r = .40; p < .01).

Results

Before testing the structural paths between variables in the model we first assessed the fit of the measurement model and of the hypothesised moderated mediation model. To estimate the distinctiveness of the five-factor model we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses. As shown in , the hypothesised five factor model fits the data well (χ2 = 564.53; df = 194; CFI = .93; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .05) and significantly better than four comparator models as indicated by the better fit indices and significant chi-square tests.

Table 2. Fit statistics from measurement and comparison models.

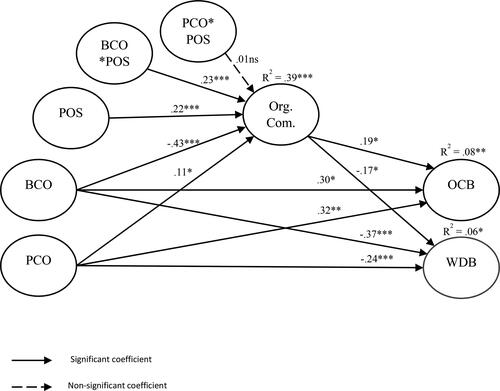

We have tested our model adapting the Mplus code developed by Stride et al. (Citation2015). A model with interactions between latent variables does not meet the assumptions of maximum likelihood estimation and the typical fit indices reported in studies using structural equation models would not be reliable. To estimate model fit we followed the procedure recommended by Sardeshmukh and Vandenberg (Citation2017). We started by computing a baseline model considering all the hypothesised relationships between constructs with the exception of the moderator which was included but only its main direct effects were specified. While in cases of disordinal interactions the fit of the baseline model may be affected, it should still meet the minimum criteria for model fit (Sardeshmukh & Vandenberg, Citation2017). Our baseline model fits the data adequately (χ2 = 637.33; df = 195; CFI = .92; TLI = .91; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .06). We compared the baseline model against the hypothesised model and assessed the extent to which the inclusion of the latent interaction reduces information loss. The values for the information criteria in the baseline model (AIC = 29986.429) are higher than those obtained in the hypothesised model (AIC = 29907.256). This confirms that introducing the latent interaction reduces information loss and, as a result, improves model fit (ΔAIC = 79.173). We are therefore confident that the hypothesised model fits the data well and have decided to retain it. The structural pathways between the variables in our model are depicted in and in which also includes information about hypothesised conditional effects.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 discuss the direct effects of ‘new career’ orientations on extra-role behaviours. Hypothesis 1 argues that people with high boundaryless career orientations will be seen by their supervisors as less likely to engage in both organizational citizenship behaviours and deviant behaviours when compared with those who do not display this orientation. Results in show, contrary to our expectations, that the boundaryless career is positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviours (β = .31; LLCI = .11, ULCI = .53) and negatively associated with deviant behaviours (β = −.37; LLCI = −.57, ULCI = −.019). Hypothesis 1 is therefore not supported.

Table 3. Direct and indirect effects between BCO/PCO and OCB/WDB.

Hypothesis 2 posits that people with a high protean career orientation will be seen by their supervisors as more likely to engage in behaviours that benefit the organization and less likely to engage in deviant behaviours. Findings in confirm our hypothesis and show that the protean orientation is positively associated with citizenship behaviours (β = .32; LLCI = .14, ULCI = .43) and negatively associated with deviant behaviour (β = −.24; LLCI = −.36, ULCI = −.03).

Hypotheses 3 discusses the mediating role of organizational commitment in the link between boundaryless and protean career orientations and extra-role behaviours. Results in show that the boundaryless career orientation is negatively associated with organizational citizenship behaviours (β = −.08; LLCI = −.31; ULCI = −.03) via its negative impact on organizational commitment (β = −.42; LLCI = −.64; ULCI = −.28). Furthermore, results show a positive indirect effect of the boundaryless career on deviant behaviour (β = .07; LLCI = .03; ULCI = .16) via commitment. Hypothesis 3a is supported.

Results show a positive association between the protean career orientation and organizational commitment (β = .11; LLCI = .01; ULCI = .22). The link between the protean career orientation and extra-role behaviours is also partly achieved via commitment and reinforces the positive direct effect found for citizenship behaviour (β = .02; LLCI = .00; ULCI = .05) and the negative association with deviant behaviour reported above (β = −.01; LLCI = −.04; ULCI = −.00). Hypothesis 3b is therefore supported.

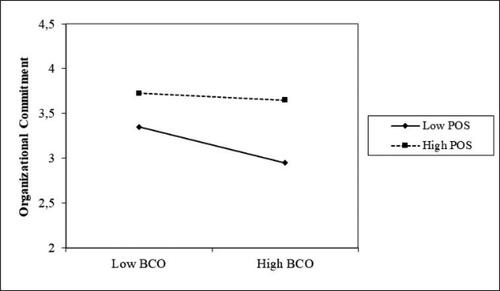

Hypothesis 4 proposes that perceived organizational support moderates the link between ‘new career’ orientations and organizational commitment. Results in show a significant interaction between the boundaryless career orientation and perceived organizational support on organizational commitment (β = .23; LLCI = .09; ULCI = .40). We have plotted the interactions to facilitate interpretation (see ). The results suggest that support is particularly important in sustaining commitment among individuals with a high boundaryless orientation who would otherwise disengage from their organization. Hypothesis 4a is supported. In contrast, results in indicate that link between the protean career orientation and organizational commitment is not shaped by perceived organizational support (β = .01; LLCI = −.09; ULCI = .09). Hypothesis 4b is therefore not supported.

Hypothesis 5 proposes that perceived organizational support shapes the conditional indirect effect of boundaryless and protean career orientations on extra-role behaviours via commitment. Findings in show that the boundaryless career orientation is negatively associated with organizational citizenship behaviour via commitment at low (β = −.12; LLCI = −.22; ULCI = −.03) and medium (β = −.08; LLCI = −.14; ULCI = −.01) levels of perceived organizational support. No significant conditional effect exists at high levels of organizational support (β = −.03; LLCI = −.08; ULCI = .01). Results further indicate that the link between the boundaryless career orientation and deviant behaviour via commitment is positive at low (β = .10; LLCI = .02; ULCI = .20) and medium (β = .07; LLCI = .01; ULCI = .13) levels of perceived organizational support but not at high levels of support (β = .02; LLCI = −.01; ULCI = .05). These findings indicate that the potential negative association between the boundaryless career orientation and positive extra-role behaviours greatly depends on the displays of support and confirm hypothesis 5a. Finally, findings in show that the effect of the protean career orientation on extra role behaviours via commitment is not influenced by the levels of perceived organizational support as all confidence intervals for the estimated coefficients cross the value of zero. Hypothesis 5b is therefore not supported.

Discussion and conclusion

Our paper aimed to contribute to career theory by evaluating aspects of the ‘new career’ deal and, more specifically, the extent to which contemporary career orientations are beneficial for organizations. We empirically explored links between protean and boundaryless career orientations and supervisor ratings of key dimensions of employee behaviour – organizational citizenship behaviours and workplace deviant behaviours – based on the argument that relatively volitional performance behaviours are the ones being challenged in the ‘new career’ landscape. In doing so, a distinctive feature of our study is the focus on workplace deviance which has largely been neglected in research on the contemporary career but which, in the context of rapid change, with its opportunities but also its frustrations, may become more salient (Baruch & Vardi, Citation2016). In addition, the paper has explored the processes through which ‘new career’ orientations stimulate extra-role behaviours. Drawing on contributions from the literature on career orientations, suggesting that stable career preferences are associated with patterns of career attitudes and behaviour (Rodrigues et al., 2013), we explored the mediating effects of organizational commitment in shaping the display of extra-role behaviours among those pursuing protean and boundaryless careers. In addition, we drew on contributions from social exchange theory to explore the extent to which this relationship was influenced by displays of organizational support based on the argument that organizations are interested in managing the attitudes and behaviours of those pursuing independent careers, particularly if they possess valuable human capital. Three key sets of findings were obtained.

First, contrary to our hypothesis, our findings showed that individuals with a high boundaryless career orientation were seen to be engaging in more behaviours that benefitted the organization as well as fewer deviant behaviours when compared with people with a low boundaryless career orientation. As expected, similar findings were obtained for individuals with a high protean orientation who also engaged in more organizational citizenship behaviour and less workplace deviant behaviour compared with those with a lower protean career orientation.

On the surface these findings – particularly those of the boundaryless career orientation - seem to suggest that contemporary career orientations are beneficial for organizations. However, when exploring the process through which protean and boundaryless career orientations lead to extra-role behaviours, a different picture emerges. This is clear in our second set of findings exploring the indirect effect of organizational commitment in the link between career orientations and extra-role behaviours. Our findings showed, as expected, that individuals with a high boundaryless career orientation were less committed to their organization and this ultimately was negatively associated with citizenship behaviours and positively linked with workplace deviance. Our study therefore shows that the boundaryless career orientation is potentially harmful for organizations if organizational commitment is low as those valuing inter-organizational career mobility are then likely to display lower voluntary constructive contributions towards the organization and more likely to engage in violations of organizational norms. In contrast, the protean career orientation was associated with higher levels of commitment and displayed a significant indirect association with extra-role behaviours. These, however, reinforce the direct effects reported above and suggest that individuals who more proactively manage their careers tend to be better organizational citizens. Potential explanations are that these people are probably able to craft their jobs and careers and, as previous research has indicated (Sturges et al., Citation2002), tend to seek and benefit from higher levels of organizational resources. Future research should further explore these mechanisms.

Finally, we explored the role of organizational support in generating commitment among individuals with ‘new career’ orientations based on the argument that individuals pursuing independent careers still have expectations about the role of organizations in contributing to the fulfilment of their work and career-related goals and organizations still value employee attachment and implement sets of practices aiming to attract and retain valuable workers (Clarke, Citation2013). Our findings showed that organizational support is particularly important in generating commitment among individuals with high boundaryless career orientations, who, as previously shown, are also more at risk of withdrawing their contribution to their employer and displaying negative performance behaviours. What our findings indicate is that when organizations offer extensive support there is no significant difference in the display of positive and negative extra-role behaviours between those possessing boundaryless and more traditional organizational career orientations. In addition, our findings showed important differences compared with the protean orientation since organizational support is relatively unimportant in generating commitment and stimulating positive and preventing negative extra role behaviours among individuals who are highly proactive in managing their careers.

Our findings contribute to career theory and have implications for the understanding of contemporary careers. First, they highlight the importance of going beyond the primacy given to individual agency in contemporary careers research (Forrier et al., Citation2009) and highlight the influence of context in shaping the outcomes of protean and boundaryless career orientations. Our findings emphasize the importance of considering the characteristics of the organizational contexts where careers unfold. Our study demonstrates the importance of support in generating commitment and positive behaviours among individuals seeking independent careers and, more specifically, a boundaryless career which can be potentially undesirable for organizations seeking to engage and get the most out of their workers. Our findings indicate that for those with a boundaryless career orientation, positive extra-role behaviour is conditional upon a positive social exchange, reflected in perceived organizational support which helps to ensure organizational commitment and which in turn generates positive extra-role behaviour and avoids negative behaviour. Future research can explore additional features of work contexts valued by individuals with ‘new career’ orientations and discuss how organizations can effectively manage their attitudes and behaviours. A possible avenue is to explore the role of key organizational resources including opportunities for job and career crafting or engagement as they may be particularly valued by individuals preferring independent careers.

Second, our findings contribute to career orientations theory by further highlighting the distinction between and the implications of the boundaryless and the protean career orientations for organizations. While the protean career orientation seems to be more generally associated with positive behaviours, the boundaryless career orientation can result in a reluctance to engage in positive citizenship behaviours and a stronger propensity to violate organizational norms. In this case it is also important to note that the outcomes of the boundaryless career orientation are more contingent on organizational policies and therefore manageable, whereas individuals with a high protean orientation seem to be more internally driven. Additional longitudinal research on the antecedents and outcomes of both orientations is needed to better understand their development and sensitivity to individual and organizational resources, job demands, and contextual variables. In particular, it is possible that the positive outcomes reported here and in other studies result from the fact that more proactive individuals are also more likely to craft their careers and are more capable of finding work contexts that suit their preferences when compared with individuals who are less inclined to or lack personal and social resources to manage their careers. It would therefore be important to explore how individuals who are highly proactive in managing their careers behave in circumstances where poor job, organization or career fit are perceived.

Thirdly, our findings have implications for HR theory and, more specifically, for the discussion of the extent to which HR practices have a universal or contingent impact on individual attitudes and behaviours. They suggest that provision of perceived organizational support has a different effect for those with boundaryless or protean orientations. This implies that other HR practices may also have different impacts and points to advantages of a more individualised approach to managing people which might be accomplished, among others, by the implementation of I-Deals, opportunities for job and career crafting and open conversations about careers.

Finally, it is important to highlight certain limitations of our paper. First, the cross-sectional design of our study is an important limitation. While our model is theoretically sound and plausible it is also possible that perceptions of organizational support influence the extent to which individuals are protean or boundaryless in their careers. Longitudinal research is needed to establish the status of protean and boundaryless careers as relatively stable orientations, ideally following individuals’ views about their careers over time and exploring how they influence their attitudes and behaviours towards their organization and also how this relationship is shaped by varying job demands and resources. The research might also be replicated in different contexts and with a more homogenous sample. Additionally, although all our measures presented good reliability, we also have to acknowledge that the need to reduce the items in some measures may impose limitations on our study.

Practical implications

It is an over-simplification to contrast the ‘old’ organizational career, controlled by management and the ‘new’ independent career characterised by career self-management by individual employees with their boundaryless and protean career orientations. Our study suggests that the application of appropriate HR policy and practice can lead to mutual gains, making this contrast less apparent. Firstly, our research confirms the importance of gaining organizational commitment. Steps organizations can take to ensure high commitment include developing a positive social exchange, offering experienced responsibility through job design, ensuring a positive psychological contract, providing supervisor support and creating a sense of security by ensuring high employability (Meyer et al., Citation2002). Secondly, organizations can take steps to ensure organizational support. Bowen and Ostroff (Citation2004) have outlined steps to create what they describe as a ‘strong’ organizational system with a supportive culture that operates throughout the organization. Organizations should ensure that regular career conversations take place that wherever possible show employees that they have an attractive future within the organization. This can include opportunities for mutually agreed career (Akkermans and Tims, 2017) and job (Tims et al., Citation2013) crafting. Carefully handled developmental performance management and talent management programmes that create opportunities for career development will help to ensure this. Evidence about contemporary employees indicates that they value employability (Nelissen et al., Citation2017). The fears among employers about the new career is that talented, highly employable staff will move on to other organizations. In this context, the challenge for organizations is to ensure that employees feel both highly employable but also highly committed to their organization. When employability is enhanced by remaining with the organization, then there is the promise of high retention and, as our research indicates, high engagement in positive organizational citizenship behaviour alongside low levels of workplace deviant behaviour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Arthur, M. (1994). The boundaryless career: A new perspective for organizational inquiry. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(4), 295–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150402

- Arthur, M. (2014). The boundaryless career at 20: Where do we stand, and where can we go?Career Development International, 19(6), 627–640.

- Baruch, Y. (2014). The development and validation of a measure for protean career orientation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(19), 2702–2723. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.896389

- Baruch, Y., & Vardi, Y. (2016). A fresh look at the dark side of contemporary careers: Toward a realistic discourse. British Journal of Management, 27(2), 355–372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12107

- Belschak, F. D., & Hartog, D. N. (2010). Pro‐self, prosocial, and pro‐organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2), 475–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X439208

- Bennett, R., & Robinson, S. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349

- Bolino, M., Long, D., & Turnley, W. (2016). Impression management in organizations: Critical questions, answers, and areas for future research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 377–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062337

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “Strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2004.12736076

- Briscoe, J., & Hall, D. (2006). The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.002

- Briscoe, J., Hall, D., & DeMuth, R. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers: An empirical exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.003

- Briscoe, J., Henagan, S., Burton, J., & Murphy, W. (2012). Coping with an insecure employment environment: The differing roles of protean and boundaryless career orientations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 308–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.12.008

- Çakmak-Otluoğlu, K. (2012). Protean and boundaryless career attitudes and organizational commitment: The effects of perceived supervisor support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 638–646. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.03.001

- Chan, K., Uy, M., Moon-Ho, R., Sam, Y., Chernyshenko, O., & Yu, K. (2015). Comparing two career adaptability measures for career construction theory: Relations with boundaryless mindset and protean career attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 22–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.006

- Clarke, M. (2013). The organizational career: Not dead but in need of redefinition. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(4), 684–703. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.697475

- Cohen, A. (2016). Are they among us? A conceptual framework of the relationship between the dark triad personality and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). Human Resource Management Review, 26(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.07.003

- Cohen-Charash, Y., & Mueller, J. (2007). Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to envy?The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 666–680. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.666

- Colbert, A., Mount, M., Harter, J., Witt, L., & Barrick, M. (2004). Interactive effects of personality and perceptions of the work situation on workplace deviance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 599–609. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.599

- Collings, D., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E., Daniels, S., & Hall, A. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099

- Culié, J., Khapova, S., & Arthur, M. (2014). Careers, clusters and employment mobility: The influences of psychological mobility and organizational support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(2), 164–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.01.002

- Dalal, R. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1241–1255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

- De Vos, A., Buyens, D., Organizational versus individual responsibility for career management: Complements or substitutes, Vlerick Leuven Gent Working Paper Series 2005/18, 2005,

- De Vos, A., Dewettinck, K., & Buyens, D. (2009). The professional career on the right track: A study on the interaction between career self-management and organizational career management in explaining employee outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320801966257

- De Vos, A., & Soens, N. (2008). Protean attitude and career success: The mediating role of self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 449–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.08.007

- Dunlop, P., & Lee, K. (2004). Workplace deviance, organizational citizenship behavior, and business unit performance: The bad apples do spoil the whole barrel. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.243

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

- Feldman, D. C., & Bolino, M. C. (1996). Careers within careers: Reconceptualizing the nature of career anchors and their consequences. Human Resource Management Review, 6(2), 89–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(96)90014-5

- Fida, R., Paciello, M., Tramontano, C., Fontaine, R., Barbaranelli, C., & Farnese, M. (2015). An integrative approach to understanding counterproductive work behavior: The roles of stressors, negative emotions, and moral disengagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 131–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2209-5

- Forrier, A., Sels, L., & Stynen, D. (2009). Career mobility at the intersection between agent and structure: A conceptual model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(4), 739–759. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X470933

- Grimland, S., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Baruch, Y. (2012). Career attitudes and success of managers: The impact of chance event, protean, and traditional careers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(6), 1074–1094. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.560884

- Gubler, M., Arnold, J., & Coombs, C. (2014). Reassessing the protean career concept: Empirical findings, conceptual components, and measurement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1908

- Hoffman, B., Blair, C., Meriac, J., & Woehr, D. (2007). Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 555–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.555

- Inkson, K. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers as metaphors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.004

- Inkson, K., Gunz, H., Ganesh, S., & Roper, J. (2012). Boundaryless careers: Bringing back boundaries. Organization Studies, 33(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840611435600

- Jawahar, I., & Liu, Y. (2016). Proactive personality and citizenship performance: The mediating role of career satisfaction and the moderating role of political skill. Career Development International, 21(4), 378–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-02-2015-0022

- Kurtessis, J., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M., Buffardi, L., Stewart, K., & Adis, C. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

- Lee, E., Park, T., & Koo, B. (2015). Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 1049–1080. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000012

- Lee, K., & Allen, N. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131

- Liu, S., Luksyte, A., Zhou, L., Shi, J., & Wang, M. (2015). Overqualification and counterproductive work behaviors: Examining a moderated mediation model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 250–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1979

- Meyer, J. & Allen, N. (1997). Commitment in the workplace. Sage Publications.

- Meyer, J., Stanley, D., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Mostafa, A. M. S., Bottomley, P., Gould‐Williams, J., Abouarghoub, W., & Lythreatis, S. (2019). High commitment human resource practices and employee outcomes: The contingent role of organizational identification. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(4), 620–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12248

- Nelissen, J., Forrier, A., & Verbruggen, M. (2017). Employee development and voluntary turnover: Testing the employability paradox. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 152–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12136

- Organ, D. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com.

- Podsakoff, N., Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Maynes, T., & Spoelma, T. (2014). Consequences of unit‐level organizational citizenship behaviors: A review and recommendations for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), S87–S119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1911

- Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Paine, J., & Bachrach, D. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26(3), 513–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600307

- Porter, C., Woo, S., & Tak, J. (2016). Developing and validating short form protean and boundaryless career attitudes scales. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(1), 162–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072714565775

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

- Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825–836. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

- Riketta, M. (2002). Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 257–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.141

- Rodrigues, R., Guest, D., & Budjanovcanin, A. (2013). From anchors to orientations: Towards a contemporary theory of career preferences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.04.002

- Rodrigues, R., & Guest, D. (2010). Have careers become boundaryless?Human Relations, 63(8), 1157–1175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709354344

- Rodrigues, R., Guest, D., Oliveira, T., & Alfes, K. (2015). Who benefits from independent careers? Employees, organizations, or both?Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 23–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.005

- Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.66

- Sardeshmukh, S., & Vandenberg, R. (2017). Integrating moderation and mediation: A structural equation modeling approach. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 721–745. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115621609

- Spector, P., & Fox, S. (2010). Theorizing about the deviant citizen: An attributional explanation of the interplay of organizational citizenship and counterproductive work behavior. Human Resource Management Review, 20(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.06.002

- Stride, C., Gardner, S., Catley, N., & Thomas, F. (2015). Mplus code for mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation models. http://www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/mplusmedmod.htm

- Sturges, J., Guest, D., Conway, N., & Davey, K. (2002). A longitudinal study of the relationship between career management and organizational commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 731–748. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.164

- Sullivan, S., & Arthur, M. (2006). The evolution of the boundaryless career concept: Examining physical and psychological mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.001

- Sylva, H., Mol, S. T., Den Hartog, D. N., & Dorenbosch, L. (2019). Person-job fit and proactive career behaviour: A dynamic approach. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(5), 631–645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1580309

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141 23506549

- Uy, M., Chan, K., Sam, Y., Ho, M., & Chernyshenko, O. (2015). Proactivity, adaptability and boundaryless career attitudes: The mediating role of entrepreneurial alertness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 115–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.005

- Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2007). Redrawing the boundaries of OCB? An empirical examination of compulsory extra-role behavior in the workplace. Journal of Business and Psychology, 21(3), 377–405. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-006-9034-5

- Wiernik, B. M., & Kostal, J. W. (2019). Protean and boundaryless career orientations: A critical review and meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(3), 280–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000324