?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study empirically investigates the myopic behavior of the stock market toward firms’ human capital resource investment, paying particular attention to two key proxies: human resource expenditure and the firm value added allocated to the employees. Focusing on human capital resource investment decisions’ alignment with near versus longer-term emphasis by investors, we examine firms listed in the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 100 over a five-year period using an established accounting-based valuation model. Our results show that human capital investment discourse leads to overweighting of the forecasted longer-term earnings in the apportionment of share price constituents, suggesting that investors consider investment in employees to generate more return in the longer-term. Additionally, our findings prove that investors respond to firm level human capital resource as an investment generating more return in the longer-term. This emphasises the importance of communicating human capital resource investment information that accurately reflects the firm value creation via employees in external financial reporting.

Introduction

Human assets are considered the most important factor in a competitive business environment. The economic progression from manufacturing to service-driven economies has triggered the emergence of the following fields of study: human capital (HC); human capital resource management (Crocker & Eckardt, Citation2014; Ployhart et al., Citation2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011); strategic human resource management (HRM) (Boon et al., Citation2018; Messersmith & Guthrie, Citation2010; Wright & McMahan, Citation2011); human capital resource investment (Becker, Citation1962, Citation1964; Delery & Roumpi, Citation2017; Flamholtz & Main, Citation1999); and human resource accounting (AAA, Citation1973; Schultz, Citation1960, Citation1961; Zula & Chermack, Citation2007). As suggested by Flamholtz et al. (Citation2002), accounting for employees as a human asset ‘has important implications for external financial reporting in the contemporary economic environment. It also has even greater significance as a powerful managerial tool in internal HRM decisions’ (p. 947). Therefore, HCR investment decisions are critical for firms and HRM strategy, which should go hand in hand—see for example, Boxall and Purcell (Citation2016).

We define firm level human capital resource(s) (HCR) as the service potential of the employees that generates future income. The role of HCR investment has been tested both at micro (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006; Samudhram et al., Citation2014) and macro (see Bronzini & Piselli, Citation2009) economic levels, revealing remarkable positive effects on productivity and organizational outcomes (Huselid, Citation1995; Jiang et al., Citation2012; Tzabbar et al., Citation2017). However, because those studies have been approached from multiple disciplines, theoretical frameworks, and levels, they have resulted in construct ambiguity in assessing the impact of HCR outcomes (Ployhart et al., Citation2014)—particularly in distinguishing HC analysis outcomes at the unit/firm and individual levels (Messersmith & Guthrie, Citation2010). The relationship of firm investment in HCR to firm performance and stock market performance remains a challenge for research, and is considered a ‘black box’ for scholars to uncover (Chowhan, Citation2016). Thus, unit- or firm-level empirical analysis examining the impact of HCR investment is timely.

The universalistic, configurational, and contingency theories (Tzabbar et al., Citation2017) support leveraging individual level HC (Becker, Citation1962) to the managerial unit level and to firm level HCR, which generates longer term returns for the firm (Andersén, Citation2021; Crocker & Eckardt, Citation2014; Ployhart et al., Citation2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011). However, the accounting system requires immediate expensing of firms’ HRE, which reduces the net income of the firm (Bushee, Citation2001). In contrast, firms’ investment in HCR by way of training and development and more value-added allocation to their employees will provide future benefit to the firm in the longer-term (Keep & Storey, Citation2014). Disclosure of HCR via current external financial reporting has continuously been subjected to myopic reactions from the stock markets due to firms’ approach to expenditures. Therefore, the markets require an equitable measure reflecting firm level HCR investment as a part of external financial reporting (AAA, Citation1973; Bassi & McMurrer, Citation2005; DTI, Citation2003a &b; Fulmer & Ployhart, Citation2014).

Research evidence related to the importance of HCR information and the impact of a firm’s investment in HC on financial performance is mixed (Roslender et al., Citation2015; Roslender & Stevenson, Citation2009), primarily due to how HC resources are treated under current accounting and financial reporting practices. The real impact of the expenditure perception on firm level HCR is also evidenced by the depletion of firm level HCR via redundancies and job cuts during the SARS CoV-2 pandemic, which left certain industries, such as hospitality, devastated in the recovery phase due to the loss of their talent base (Hancock, Citation2021). A clear research gap exists in our knowledge, mainly in relation to the inadequacy of empirical evidence to suggest that external stakeholders, such as investors, should take an investment perspective based on the future earning potential of employees, rather than treating HCR as an expense or budget item to be curtailed. Additionally, how the stock market reacts to firm level HCR investment is still to be addressed, due primarily to the absence of an equitable measure reflecting firm level HCR as an investment—due to the future earnings/value creation potential of employees—instead of viewing them solely as an expense.

Addressing the above gap, we contribute to the literature by being pioneers in using a market-based perspective to explore whether the stock market perceives firm level HCR as an investment generating longer-term outcomes (Mabey & Ramirez, Citation2005). Our study examines two HCR valuation measures reflecting firm-level investment in employees. First, human resource expenditure (HRE) is the amount firms immediately write-off in their income statements. HRE includes short-term employment benefits, as well as firms’ spending for employee training and development, which creates longer-term benefits. As an addition to financial statement information, we propose that firms disclose how the firm’s total value added is allocated between each category of stakeholders. Our contribution in proposing the second measure is instrumental, as it allow firms to calculate the human capital value added (HCVA). HCVA is derived taking in to account the techniques used by Pulic (Citation1998; Citation2000) in deriving the value-added intellectual capital coefficients (VAIC). HCVA can be defined as the employee contribution in the firm value creation. This second measure HCVA that we propose allows firms to calculate how much of the firm’s total value added is allocated to employees as a proportion of the total value added.Footnote1 We then use an accounting-based valuation model proposed by Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000),Footnote2 which was based originally on Ohlson (Citation1995). It is widely applied currently (e.g. Fullana et al., Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2017; Sampson & Shi, Citation2020) to investigate firms’ market value. We use the same model to ascertain whether the market values of firms with high (low) levels of HRE and HCVA are driven mostly by their longer-term (near-term) earnings.

We further contribute to the HC accounting literature by providing empirical support for the theoretical debate that HCR is an investment (Becker, Citation1962; Breton, Citation2015; Ployhart et al., Citation2014 and Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011; Qadri & Waheed, Citation2014; Schultz, Citation1961). We have developed and tested four hypotheses to determine whether firm level investment in HCR generates more return in the longer term and whether the investment in a firm’s HCR correlates to non-myopic pricing when investors consider HCR as an investment generating longer-term return.

Theoretical underpinning

Human Capital resources

Human capital provides the capacity to achieve economic outcomes at the individual level (Becker, Citation1962; Youndt & Snell, Citation2004). Leveraging individual-level HC to unit/firm-level HCR through emergence or complementarity provides the foundation for unit/firm-level HCR (Andersén, Citation2021; Ployhart et al., Citation2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011). According to the universalistic perspective, accumulating cognitive ability enables organizations to achieve significantly better outcomes (Tzabbar et al., Citation2017). The configurational perspective supports firm-level HCR emergence and complementarities as bundles of HRM practices having a stronger impact than individual practices (Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011). The contingency perspective, however, suggests that the relationship between a firm’s HCR and its outcome is context-specific. All three theories: universalistic, configurational, and contingency (Tzabbar et al., Citation2017), support the leveraging of individual level HC (Becker, Citation1962) into managerial and firm level HCR, which generates longer term returns for the firm (Andersén, Citation2021; Crocker & Eckardt, Citation2014; Ployhart et al., Citation2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011). Thus, firm level HCR has to be recognized as a capital investment, instead of as an expenditure in accounting terms. And it needs to be communicated to the external stakeholders, including investors, lenders, and other finance providers, as this information is instrumental in understanding the future earning potential of a firm (Lepak & Snell, Citation1999).

Human capital theory, under which HCR is perceived as an investment, underpins the ‘future service potential of employees for the firm’ (Flamholtz, Citation1972; Lev & Schwartz, Citation1971, Citation1972). Accordingly, considering the two factors, specialty in skills and non-transferability, developing employees’ skills—where skills are firm-specific and have no value apart from the firm—can be capitalized as HC investment (Lepak & Snell, Citation1999). The resource-based theory advocates that a resource becomes valuable for firms if it has the potential to contribute to their competitive advantage; thus, resource-based theory makes a case for categorizing HCR as an investment (Nyberg et al., Citation2014). Both HC and resource-based views substantiate the notion that part of firms’ spending on employees constitutes an investment in the longer-term. From either perspective, investment in HCR leads to strong organizational performance, be it relating to universalistic, configurational, or contingency HRM (Tzabbar et al., Citation2017). The experimental studies of Elias (Citation1972) and Schwan (Citation1976) indicated that stakeholders tend to respond well to HCR investment calculated separately from expenditures when this information is communicated appropriately in financial reports.

Financial accounting perspective, economic short-termism and Human Capital resources

Investors rely on several indicators to measure firm investment in HCR (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006; Pfeffer, Citation1997). Investors mainly use HRE, as it is the most easily tracked and commonly used HCR indicator in accounting and financial reporting systems (Pfeffer, Citation1997). According to financial accounting standards, HRE, which is the total spent on the HCR of an organization, is written off as an expense in the income statement (IASB, Citation2011). The total amount of HRE includes short-term employment benefits, as well as the amount that firms spend on employee training and development, which creates longer-term benefits. Ironically, despite being continuously referred to as a firm’s most valuable asset, the value of HCR has never been capitalized or recognized as an asset in the balance sheets, and has likely been overlooked by investors as well, particularly since higher HRE lowers key financial indicators, such as profit. According to current accounting treatment, the more a firm spends on employees, the lower is the profit reported at the end of the accounting year. Investors, managers, and most other stakeholders make their investment and managerial decisions based on this financial outcome.

Issues related to the current accounting treatment and financial reporting practices described above have attracted much debate over the years, as these characterize investment in employees as value destruction (expense) rather than value creation (investment) (Becker, Citation1993; Elias, Citation1972; Roslender et al., Citation2015; Roslender & Stevenson, Citation2009). Recognition of a firm’s investment in HCR under mainstream accounting is seldom researched or practiced at the empirical level (Roslender et al., Citation2015; Turner, Citation2005). As a consequence, to date, HCR investment decisions have mostly relied on the accounting discourse around cost minimization, and not on the importance of HCR investment from a value creation point of view (Toulson & Dewe, Citation2004; Turner, Citation2005). The most obvious solution to increasing competitive pressure has always been cost cutting; in this context, the HR budget—particularly in knowledge-based industries—lays claim to being the most susceptible (Teague & Roche, Citation2014), in spite of its role in achieving organizational aims (Millar et al., Citation2017). According to the managerial opportunism argument (Antia et al., Citation2010; Laverty, Citation1996), the existing expenditure perspective of accounting for HRM, where all HRE is treated as an expense item, is drawing myopic behavior from managers by inducing them ‘to focus excessively on short term profits relative to long term objectives’ (Cannon et al., Citation2020, p1444). This could also be associated with a similar myopic reaction from the stock market, in which investors prefer short-term earnings to longer-term earnings (Bassi & McMurrer, Citation2005; Bushee, Citation2001; Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006). This is characterized by the investors shortsighted view of potentially longer-term investments, such as investment in a firm’s HCR, if perceived as an expenditure. In this scenario, the capital market tends to place less emphasis on the longer-term earnings, thus leading managers to tilt investments toward short-term payoffs. When HCR is perceived as an investment, the capital market realizes the longer-term earnings potential of this investment and places more emphasis on the longer-term investment, while placing less emphasis on the near-term earnings.

To date, studies evaluating the outcomes of HCR have mainly focused on the direct relationship between HCR measures and short-term economic or financial performances (Elias & Scarbrough, Citation2004; Fulmer & Ployhart, Citation2014; Mirvis & Macy, Citation1976). Therefore, the longer-term value creation potential of the HCR investment is yet to be examined and understood through empirical analysis. It is yet unknown how the impact that firm level HCR has on longer-term performance outcome and its associated effect on the stock market return in the longer-term can be explained or modeled; hence, it represents a black box, leading to further investigation (Demortier et al., Citation2014). In deciphering this black box (Boxall et al., Citation2011), the direct relationship between HCR and organizational performance appears to be opaque, due to the inadequacy of existing models to capture the true value of HCR (Bassi & McMurrer, Citation2005; Fulmer & Ployhart, Citation2014; Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006). It is arguable that a direct approach involving a market response would force one to either assume that a given market response is entirely attributable to HCR investment or to find a way to disentangle the potion of market response caused by HCR investment, both of which present significant hurdles in developing a reliable model.

However, based on the firm value apportionment model through book value and the present value of future earnings (Ohlson, Citation1995), previous studies segregated earnings into near-term and longer-term components to examine investors’ shortsightedness in general (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000) and towards organizational practices (Bushee, Citation1998) or investor characteristics in particular (Bushee, Citation2001). This approach addresses the current research gap between HCR and performance outcomes by investigating whether HCR investment decisions are aimed at longer-term performance results or at near-term profit increases at the expense of future persistent longer-term earnings. Therefore, instead of focusing on the often studied direct relationship between HC indicators and the short-term performance and finance indicators, we rely on value line data and an accounting based valuation model (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000). We did so to assess whether the share price of firms with high HCR valuation measures is determined more by their forecasted longer-term earnings than by their forecasted near-term earnings. The model we use facilitates the decomposition of firm value via three segments: (1) the book value of the firm’s shares, (2) forecasted near-term firm earnings, and (3) forecasted longer-term earnings or terminal value (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000). These segments are defined further in the research method section. Following Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000), we assume that if investors exhibit non-myopic behavior, then book value, forecasted near-term earnings, and forecasted longer-term earnings/terminal value contribute equally in the apportionment of the share price. Hence firms would tend to equally weight near-term and longer-term outcomes related to their decisions. We test the model for the weight assigned to near-term and longer-term earnings by investors using empirical data for firms supporting high and low HCR valuation measures.

Hypotheses development

In HRM, the strategic level objective—i.e. achieving strategic competitive advantage via investment in HCR—is expected to be more long-term focused (Elias & Scarbrough, Citation2004). However, in an environment where measurement is strongly emphasized, a common response to real and immediate pressure has been the view that the ‘primary function of human resources is to contribute to organizational productivity and profit enhancement’ in the short term (Pfeffer, Citation1997, p. 364). From this standpoint, HR professionals are pressured to seek short-term victories at the expense of longer-term benefits. On the other hand, the strategic objectives follow the HCR investment argument by proposing HCR as an investment with longer-term value creation potential (Huselid, Citation1995; Tzabbar et al., Citation2017). Treating HCR as an investment motivates stakeholders to adopt an HCR investment perspective in making firm-related decisions. Our research hypotheses are developed around the argument that investment in HCR generates more returns/earnings in the longer-term.

Human resource expenditure as an investment

Since the early 1960s, spending on education at household and state levels was considered an investment in HC with longer-term benefits (Becker, Citation1962, 1993; Breton, Citation2015; Qadri & Waheed, Citation2014; Schultz, Citation1961). Additionally, firms spent to develop firm-level HCR to make their employees more suitable for their roles at work (Hayek et al., Citation2016). As a result, the accounting variables of labor and related costs—including salaries, wages, pension costs, profit-sharing and incentive compensation, payroll taxes, training, and other employee benefits—have long been used as measurement tools for firms’ investment in HCR (Becker, Citation1962; Chan, Citation2009; Chen et al., Citation2005; Chen & Lin, Citation2004; Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006; Samudhram et al., Citation2014). From both universalistic HRM and labor-economic perspectives, investors perceive the aggregate labor cost disclosed in annual reports as a proxy for HCR investment (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006; Pulic, Citation1998, Citation2000).

Empirical evidence on HRE is mixed: While some studies show that firms voluntarily disclosing high labor-costs outperform their non-disclosing counterparts, others suggest a lack of consistency (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006). Existing classifications of HRE and the current accounting conventions hardly substantiate the HCR investment argument (Toulson & Dewe, Citation2004). From a financial perspective as well, it would be unhelpful to use ‘big data’ to capture firms’ HCR investment, because labor should not be modeled as an expense (Angrave et al., Citation2016). Similar empirical evidence is also reported for research and development (R&D) expenditures (Chan et al., Citation2001; Green et al., Citation1996; Nixon, Citation1997), suggesting a lack of consensus among accounting standard-setters (Roslender et al., Citation2015; Roslender & Stevenson, Citation2009). The danger of short-termism in the interpretation of investment related to intellectual capital, which includes human capital and R&D expenditures, is reported as a critical issue in accounting and management literature (Green et al., Citation1996; Heyden et al., Citation2017). Against this backdrop, relying on our proposed HCR investment argument, we expect investors to perceive HRE as an investment generating longer-term return, and thus, to hypothesise a positive (negative) relationship between the level of HRE and the longer-term (near-term) earnings of firms.

Hypothesis 1: The level of human resource expenditure by firms will be positively (negatively) associated with the proportion of firm value in longer-term terminal value (near-term earnings).

Human Capital value added as investment

As increasing profits in the near-term are usually linked to executive rewards (Lev, Citation2000), an expenditure perspective on HRM could drive opportunistic behavior from managers (Antia et al., Citation2010; Laverty, Citation1996) and encourage a myopic reaction in the stock market (Bushee, Citation1998). By ‘myopic reaction’ we mean investors over estimating near-term earnings and under estimating longer-term earnings in assigning value for constituent components of share price for firms curtailing HRE, thus inadvertently penalizing firms that heavily invest in firm-level HCR (Bassi & McMurrer, Citation2005). This could adversely influence stakeholder perceptions of treating HCR as a strategic longer-term investment.

A complementary view to the expenditure perspective occurs when stakeholders perceive HR as an investment in firms’ value creation. That employees have future service potential has been a fundamental principle underpinning several HCR valuation studies (Flamholtz, Citation1971; Lev & Schwartz, Citation1971). As a recognition of the growing power of labor in firm value-creation, the value-added concept has been proposed for use in conceptualizing the HCR investment in different contexts (Burchell et al., Citation1985; Haller et al., Citation2018; Toulson & Dewe, Citation2004). From the vantage point of HCR investment, the use of this measure is more realistic and equitable than the use of HRE (Turner, Citation2005).

The statement of value added shows ‘how the benefits of the efforts of an enterprise are shared between employees, providers of capital, the state, and reinvestment’ (ASSC, Citation1975, p. 48). On the premise that the value added allocated to the employees reflects the portion of a firms’ value that is created by its employees (Burchell et al., Citation1985), the portion of value added allocated to employees (HCVA) has been proposed as a more equitable measure of firms’ HCR investment (Chan, Citation2009; Chen et al., Citation2005; Turner, Citation2005). According to the HCR investment perspective, a high investment in firms’ employees and the allocation of higher value added to their employees leads to a strategic competitive advantage that contributes to firms’ value creation, which in turn generates higher returns for firms in the longer-term. Thus, we hypothesise a positive (negative) relationship between the level of HCVA and the longer-term (near-term) earnings.

Hypothesis 2: The portion of value added allocated to employees by firms will be positively (negatively) associated with the proportion of firm value in longer-term terminal value (near-term earnings).

Stock pricing and HCR investment

Previous empirical evidence suggests there is a myopic reaction in the stock market when investors place a greater emphasis on near term earnings than on longer term earnings of the firms they invest in (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000). Myopic reaction has also been attributable to the types of investors (Bushee, Citation2001) and to firm management practices, such as curtailing investment in research and development (Bushee, Citation1998). While hypotheses 1 and 2 address firms’ returns in relation to the level of their HC investment measured via the HRE and HCVA indicators, indicating whether firm level HCR investment is positively related to the longer term earnings and the impact of the control variables on that relationship, they do not necessarily provide strong evidence as to whether firms’ decisions to invest more in HCR have led firms to be more longer-term oriented. If this were the case, then investors of firms with high investment in HCR would place a greater value on longer-term earnings in share price determination. Therefore, we use the approach adopted by Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) and Bushee (Citation1998; Citation2001) to examine and better understand the stock market’s reaction to firm level HCR investment. Adopting the seminal work by Ohlson (Citation1995), Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000), and Bushee (2001), we take into account the constituent components of share price/firm value: (1) book value of the firm’s shares, (2) forecasted near-term firm earnings, and (3) forecasted longer-term earnings or terminal value (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000). Under myopic investor behavior, it is reported that forecasted near-term earnings constitute more, whereas forecasted longer-term earnings/terminal value constitute less in the apportionment of a firm’s value (measured via the share price). However, if investors perceive a firm’s investment in HCR as a capital investment generating more longer-term returns than near-term returns, then investors would place more weight on longer-term earnings/terminal value and less weight on the near-term earnings; thus forecasted longer-term earnings constitute more, while forecasted near-term earnings constitute less, in the apportionment of firm value. We developed hypotheses 3a and 3 b to test this model for the weight assigned to near-term and longer-term earnings by using value line data and analysts’ forecasts for firms supporting high and low HCR valuation measures.

Hypothesis 3a: For firms with a high (low) level of human resource expenditure, the proportion of value in long term terminal value will be over (under) valued while the proportion of value in near-term earnings will be under (over) valued.

Hypothesis 3 b: For firms with a high (low)level of value added allocated to employees, the proportion of value in long term terminal value will be over (under) valued while the proportion of value in near-term earnings will be under (over) valued.

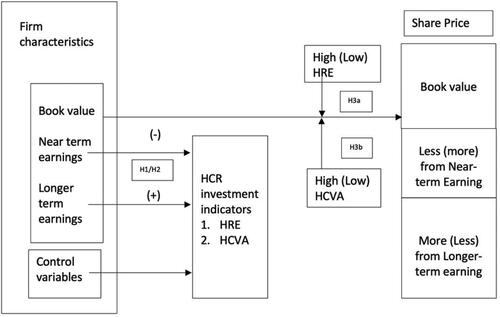

Following the development of the hypotheses, we developed the following model as presented in . The figure illustrates how the value components and control variables determine the HCR investment level and the price-level testing, incorporating the HCR indicator interaction effect. The research model section illustrates how the constituent components: book value, near-term earnings and longer-term earnings are estimated using the value line data and analysts’ forecasts.

Research model

Ohlson (Citation1995): starting point of (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000)

According to Ohlson (Citation1995), the value of the firm (Pt) can be represented as the accounting book value (BVt) plus the expected present value of all future abnormal earnings (PVAEt). In this case, abnormal earnings are defined as the actual earnings (Xt+τ) minus normal earnings (prior book value times a rate of return equal to the cost of capital (r) i.e. rbt+τ-1). Firm value (Pt) can be given using equation (1), below.

(1)

(1)

where: pt= stock price of the firm at time t; bt= book value at time t; r = discount rate measured as risk-free rate of return (treasury bond rate); Xt+τ= earnings for period t + τ

Accounting-based valuation model (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000)

From Equation (1) of Ohlson’s (Citation1995) model, Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) noted the expected price-to-book premium for the arbitrary future horizon, T. The arbitrary horizon T is used to demarcate the near-term (T) and the longer term (Beyond T) time horizons. Accordingly, a firm’s value is decomposed to book value (which accounts for the past year’s earnings and the net capital contribution), forecasted earnings in the near-term (which accounts for the discounted abnormal earnings for the time defined as a near-term period, T), and the forecasted earnings in the longer-term/terminal value (which accounts for the abnormal earnings to be generated for infinite years after the defined near-term period, T). The accounting-based valuation model proposed by Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) regresses the actual stock price against its estimates of constituent components: book value (BVt), the present value of forecasted earnings in the near-term (PVNTt), and the present value of forecasted earnings in the longer-term, which is also termed as the terminal value (PVTVt). (equation (2)).

(2)

(2)

where: pt= stock price of the firm at time t, bt= book value at time t (i.e. section 1 of equation (1)), r = discount rate measured as risk-free rate of return (treasury bond rate), Xt+τ= earnings for period t + τ, and T = demarcation for near-term/longer-term conditions (T = 1year), Term 2 of equation (2) calculates the near-term earnings (PVNTt), Term 3 of the equation (2) calculates the longer-term earnings/terminal value (PVTVt)

Value line forecast data provide earnings, book values and dividend estimates up to four years. However, following the Bushee (2001) argument, in order to test for the most extreme near-term, we defined the near-term to be the one-year ahead forecast horizon, and we considered all of the forecast beyond one year to be the longer-term earnings or the terminal value. Value line forecast data helps investors estimate the value they assign for the near-term earnings and the longer-term earnings in determining the current year’s share price at any point in time.

Human Capital investment and firm value distribution in near versus longer-term earning

To test for firm level HC investment preference for the distribution of value in book value contribution (BVC), near-term earning contribution (NTC), and longer-term earning or terminal value contribution (TVC), we have divided all the variables in the right hand side of equation (2) by Pt (Bushee, Citation2001) and regressed them with the level of HCR investment indicators: HRE and HCVA. Equations (3) and (4) test for hypotheses 1 and 2 respectively.

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Since prior research suggests that the level of HCR investment could vary with firm size (SIZE), industry (IND), leverage (LEV), profitability (PRO), liquidity (LIQ), and employee productivity (EMPRO), which are likely to be correlated with the distribution of firm value, we have added these variables as control variables (Bushee, Citation2001; Chen et al., Citation2005; Samudhram et al., Citation2014; Vithana et al., Citation2021), as indicated below in Equationequations (5)(5)

(5) and Equation(6)

(6)

(6) .

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

Price level test using cross-sectional regression (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000)

Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) originally captured the myopic pricing of stock using Equationequation (7)(7)

(7) , which regresses actual share price against its constituent components: book value, forecasted near-term earnings, and forecasted longer-term earnings.

(7)

(7)

where:

pjt= stock price of the firm at time t,

= regression coefficients, and

ωjt= residual error

Following Bushee (Citation2001), we extended the Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) model to ascertain whether the relationship between the level of HCR investment and the apportionment of future earnings between near-term and longer-term earnings translates into stock mispricing. In this case, to test whether mispricing is concentrated in firms with high HCR investment, we interact the variables in the Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) model with the HCR investment indicators, HRE and HCVA. In this case, HRE/HCVA equals 1 if the firm is above the median HRE/HCVA, and HRE/HCVA equals 0 otherwise. The results of these models (equations (8) and (9)) help us understand how investors perceive firm level HCR investment—whether it’s an investment generating more longer-term return.

Pjt = α0 + α1 HREt+ α2BVt + α3 (BV* HRE) t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HRE) t + α6PVTVt +α7 (PVTV*HRE) t +ωjt(8)

Pjt = α0 + α1 HCVAt+ α2BVt + α3 (BV* HCVA) t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HCVA) t + α6PVTVt +α7 (PVTV*HCVA) t +ωjt(9)

Where: pjt= stock price of the firm at time t, = constant,

= regression coefficients, and ωjt= residual error

The values the cross-sectional regression assigns to the coefficients are analyzed and interpreted as proposed by Bushee (Citation2001). If the firm level HC investment is associated with longer term financial outcome and higher return in the longer term, the regression results for equations (8) and (9) should yield these estimated coefficients: α5 < 0 and α4 + α5 < 1; α7 > 0 and α6 + α7 > 1. This indicates that the coefficients for the interaction terms are not zero, and the sum of the two coefficients of the value component variable should be significantly different from 1 in the directions predicted above. The results for these two models can confirm whether firm level HCR investment, measured as HRE or HCVA, is in fact perceived as an investment generating longer-term return.

Method

Research sample and data

The UK has witnessed attempts to formalize the practice of HCR accounting and to develop policies to enhance its current inadequacies and anomalies (DTI, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Elias & Scarbrough, Citation2004). Major initiatives in this regard were taken by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) (DTI, Citation2003a, Citation2003b) and the previous labor government (Roslender et al., Citation2015; Roslender & Stevenson, Citation2009). Recognizing this positive intervention, firms listed in the London Stock Exchange (UK) for a five-year span (from 2005 to 2009) in the FTSE100 listing were chosen for our research sample, facilitating a longitudinal panel study (Schmidt, Citation1997). The study period follows UK policy attempts to encourage more HC management practices. Moreover, the period under study takes into account similar economic policies in favor of accounting for people, under labor government initiatives (Roslender et al., Citation2015). The decision to choose the FTSE 100 listing reduces the impact of size effect and minimizes the impact of having many outliers in the study. Additionally, Duggal and Millar (Citation1999) reported that large firm size and being listed in the top tier index (S&P 500) significantly determine institutional ownership, which could be an indicator in examining timely response to managerial information in the stock market, contributing to selection of the FTSE100 as our sample. The initial research sample included 500 firm-year observations, which was screened down to 210 firm-year observations based on the availability of data on HRE and data to calculate HCVA. The sample was further reduced to 198 firm-year observations due the data availability in value line data of forecasted earnings per share, price earning ratio, and dividend per share, which were used in the calculation of the near-term and longer-term earnings contributions to be used in the (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000) price apportionment model.

Out of 500 firm-year observations, data for HRE and data to calculate HCVA were hand collected from 210 published annual reports of FTSE 100 firms and the FAME (bureau van dijk) database; data for these variables were not published in the remaining sample. Historical data on book values and all the other control variables and value line data, including forecasts of future earnings per share, price earnings ratio, and book value, were collected from the Bloomberg database. We used these data to calculate the forecasted near-term earnings and the forecasted longer-term earnings contribution in share price apportionment, following the (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000) model. All the variables in the model are further explained in Appendix 1, which illustrates data collected for the variables and the calculations based on the equations. Data analysis was conducted using STATA 16.1. We employed the pooled linear regression technique with robust standard error to estimate the regression coefficients in the research models described above. Additionally, we used panel data analysis with the firm and year fixed effect and random effect model estimates as robustness checks (Pennings et al., Citation1999). A complete set of data diagnostic tests was performed to ascertain the robustness of the results.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Firm sizes in the research sample range from £Mn 4,390 – £Mn 134,376 with an average market capitalization of £Mn 28,573. The sample firms publishing data on the HC investment indicators (i.e. the key variables of the study) are large firms. The average of the HC investment indicator HRE is £Mn 2,911 (range: £Mn 46 – £Mn 14,438), and the average HCVA is .53 (range: −.36 − 24.32). Following the Bushee (Citation2001) sample statistics, firm value is mostly concentrated in book value, whereas, the near-term and longer-term earnings contributions were relatively small and, on average, negative (which does not mean they have negative expected earnings). presents all the descriptive statistics for the HC investment indicators, share price, value component variables, and control variables used in the research model. The correlation matrix for all the variables in the model is given in . Except for book value and near-term earnings, all the other correlation coefficients are significantly lower than they would have been, especially in the case of earnings estimates for longer-term and near-term components (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Corelation matrix.

Human Capital investment and proportion of firm value in near and longer-term earnings

Results for the pooled linear regression () revealed that firms with a greater proportion of firm value based on book value and near-term earnings, and less on the longer-term terminal value, resulted in higher HRE. This result was the same after considering control variables, such as firm size, industry, leverage, profitability, and illiquidity. Among the control variables, firm size and leverage revealed a positive relationship with HRE, whereas profitability and employee productivity revealed a negative relationship. In addition to pooled linear regression, firm and year fixed effect () and random effect () are used to mitigate the problem of cross-sectional correlation. Results also held for the introduction of the firm and year fixed effect and the random effect models, where, out of all the control variables, only firm size showed a negative relationship with HRE. For the HC investment proxy, HCVA, pooled linear regression revealed no significant relationship between the proportion of firm value in value component variables and the level of HCVA. However, the introduction of firm and year fixed effect resulted in a positive relationship between the proportion of near-term earnings in firm value and HCVA and a significant negative relationship between the proportion of longer-term earnings in firm value and HCVA. None of the control variables revealed a significant relationship with the level of HCVA.

Table 3a. Model 1:

Model 2:

Table 3b. Model 1:

Model 2:

Table 3c. Model 1:

Model 2:

Price level test to investigate human Capital resource investment and stock pricing

Price level testing using cross-sectional regression (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000) is implemented to ascertain whether a firm’s preference for HCR investment translates into stock pricing to determine whether HCR investment generates more longer term return. Results are reported for the pooled linear regression (), regression with firm and year fixed effect (), and regression with random effect (), where panel A reports regression without HCR investment interaction, and panels B and C report regression with the HCR investment indicators HRE and HCVA, respectively. Results reported in panel A did not reject the null hypothesis for the P value (coefficient = 1), which suggests that, when taking into account the full FTSE100 sample, results revealed no evidence for near-term or longer-term earnings preference, and thus revealed no mis-pricing in general. panel B reveals that firms with high HRE are not associated with undervaluation (overvaluation) of near term (longer term) earnings, as the null hypothesis for P value (coefficient = 1) was not rejected. Additionally, the total of the coefficients for PVNT + HRE*PVNT and PVTV + HRE*PVTV was fairly close to 1. However, according to panel C, results revealed that firms with high HCVA are associated with undervaluation (overvaluation) of near-term (longer term) earnings, as there is evidence to reject the null hypothesis based on the P value (coefficient = 1). In this case, the total of the coefficients for PVNT + HCVA*PVNT was less than 1, whereas PVTV + HCVA*PVTV was greater than 1. Overall, for HCVA, regression results fulfilled the conditions α5 < 0 and α4 + α5 < 1, and α7 > 0 and α6 + α7 > 1, revealing that firms allocating a greater portion of value added to their employees assign more weight to the longer-term earnings component of share price and are in fact longer-term-oriented.

Table 4. Panel A: Regression without HCR investment interactions: Pooled linear regression Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1 BVt + α2PVNTt + α3PVTVt +ωjt

Panel B: Regression with HCR investment indicator HRE interaction: Pooled linear regression Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1 HREt+ α2BVt + α3(BV*HRE)t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HRE)t + α6PVTVt +α7(PVTV*HRE)t +ωjt

Panel C: Regression with HCR investment indicator HCVA interaction with: Pooled linear regressionResearch model: Pjt = α0 + α1 HCVAt+ α2BVt + α3(BV*HCVA)t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HCVA)t + α6PVTVt +α7 (PVTV*HCVA)t +ωjt

Table 5. Panel A: Regression without HCR investment interactions with firm and year fixed effect Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1 BVt + α2PVNTt + α3PVTVt +ωjt

Panel B: Regression with HCR investment indicator HRE interaction with firm and year fixed effect Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1 HREt+ α2BVt + α3 (BV*HRE)t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HRE) t + α6PVTVt +α7(PVTV*HRE)t +ωjt

Panel C: Regression with HCR investment indicator HCVA interaction with firm and year fixed effect Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1 HCVAt+ α2BVt + α3(BV*HCVA)t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HCVA)t + α6PVTVt +α7(PVTV*HCVA)t +ωjt

Table 6. Panel A: Regression without HCR investment interactions: Random effect model Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1 BVt + α2PVNTt + α3PVTVt +ωjt

Panel B: Regression with HCR investment indicator HRE interaction: Random effect model Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1HREt+ α2BVt + α3(BV*HRE)t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HRE)t + α6PVTVt +α7(PVTV*HRE)t +ωjt

Panel C: Regression with HCR investment indicator HCVA interaction with: Random effect model Research model: Pjt = α0 + α1HCVAt+ α2BVt + α3(BV*HCVA)t+α4PVNTt + α5(PVNT*HCVA)t + α6PVTVt +α7(PVTV*HCVA)t +ωjt

Discussion

Market reactions in favour of either near-term or longer-term earnings, in general or as a reaction to specific management practices or environment circumstances, have been evidenced in the literature (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000; Bushee, Citation2001; Kim et al., Citation2017). Taking an interdisciplinary approach, we used the proxies HRE and HCVA to interact the price level test (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000; Bushee, Citation2001) with firm level HC investment decisions. The full FTSE100 sample is neither near-term nor longer-term oriented. However, we show that once interacted with the proxy for firm level HCR investment, firms allocating more value added to employees have a longer-term focus. This supports the argument that firm value creation by employees, reflected by the portion of value added that firms allocate to the employees, is a better proxy for investment in HCR (Burchell et al., Citation1985; Haller et al., Citation2018). We show that investors have reacted positively to firms making a greater investment in employees in terms of value-added allocation by placing more weight on their longer-term earning potential.

These results suggest that firms should strategically manage their HCR, treating it as an investment by understanding the relationship between near term cost-cutting and longer-term prosperity. Our results are in line with the argument that downsizing, layoffs, cutbacks, and other actions firms take to target their HR budgets during periods of economic downturn make it harder for those firms to reverse the declining spiral due to the loss of institutional knowledge and erosion of mutual commitment (Bedeian & Armenakis, Citation1998). Confirming previous theoretical and conceptual literature, our findings posit HCR as an investment—as employees contribute to firm-level value creation—substantiating the argument that such investment can be treated as an investment and needs to be communicated to the external stakeholders. (Fulmer & Ployhart, Citation2014; Nyberg et al., Citation2014; Ployhart et al., Citation2014).

Contrary to evidence from the human resource accounting field, which continues to use HRE as a proxy for investment in HCR in market research (Chen et al., Citation2005; Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006), this proxy can be quite deceptive, whereas the alternative suggested approach of firm value creation via employees—i.e. HCVA—appears to be a better choice. Once HCVA is used as the proxy, the results align to make intuitive sense, revealing that firms that create/allocate more value added through/to their employees are more sustainable and longer-term focused.

Using HRE as a proxy might lead to budget cuts to limit HRE in financial distress scenarios. However, downsizing, job redundancies, and trimming down training and development, among other cost-saving measures, can render firms vulnerable to erosion of their intellectual asset base (Likert, Citation1967) from losing their most talented employees (Baruch & Vardi, Citation2016; Kets de Vries & Balazs, Citation1997). This will leave the firm with only the ‘dreck that float on top,’ where the firm’s future is left in the hands of the less talented (Bedeian & Armenakis, Citation1998, p. 58). We have witnessed the overall economic repercussions of this after the financial crisis, and now particularly in the hospitality sector, as a result of the SARS CoV-2 pandemic related talent losses over the period (Hancock, Citation2021). Using HCVA as a proxy for the measurement of HCR correctly segregates firms that invest in HCR and exhibit a longer-term nature, thus proving HCVA to be a better approximation of firms’ investment in their HCR than HRE. Our empirical evidence, based on the market-based analyses, shows that money spent on HCR is a strategic investment with a longer-term nature, which also suggests that HCR is an investment.

Lastly, we highlight the mismatch between accounting discourse on employees, which relies on transaction cost theory, and HR discourse on employees, which relies on both HC theory and resource-based argument. This lends support to HRM theory—from universalistic, configurational, and contingency perspectives—suggesting that investment in people via HRM practices will lead to better performance, in line with recent meta-analyses (Jiang et al., Citation2012; Tzabbar et al., Citation2017).

Contribution to theory and literature

Theoretical and conceptual strands of literature on HCR argue that firms invest in employees to generate (1) HC at the individual level (Becker, Citation1962; Youndt & Snell, Citation2004), and (2) HCR at the firm level (Fulmer & Ployhart, Citation2014; Nyberg et al., Citation2014; Ployhart et al., Citation2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011). However, there is a black box surrounding the relationship between firm-level HCR and performance/outcome, with a lack of firm-level empirical evidence on whether investment in HCR leads to longer-term benefits (Kilroy et al., Citation2017).

In our study, we propose HCR investment measures and substantiate the HCR investment argument with empirical data. We conceptualise HCR investment using first, the most frequently used measure, that is, HRE (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006), and second, the alternative measure reflecting firm value creation, that is, HCVA. We comprehensively test both these measures. First, we revealed investors myopic reaction towards the levels of HRE—the most widely available and most widely used proxy for firm-level investment in HCR (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006). Second, we discovered that our conclusions significantly change when we use HCVA as a proxy for HCR. As the firm value added distributed to employees resembles firm value creation via employees (Burchell et al., Citation1985; Haller et al., Citation2018), this alternative proxy, HCVA, supports the argument that HCR is an investment generating return in the longer term. Additionally, the real impact of the expenditure treatment on firm level HCR is also significantly evidenced, owing to the depletion of firm level HCR via redundancies and job cuts during the SARS CoV-2 pandemic, which left certain industries, such as hospitality, devastated at the recovery phase due to the loss of their talent base (Hancock, Citation2021). The empirical contributions of our study, therefore, effectively warn against the expenditure approach and emphasize the importance of taking firm level HCR as an investment generating returns for firms in the longer term.

Our main conceptual contribution is that, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to examine the near-term and longer-term impact of firm level HCR investment on firm valuation, taking into account the future value creation potential of firm level HCR. We are also pioneers in adopting market based empirical testing to demonstrate this. Our findings extend the theoretically proposed HCR investment concepts in previous literature to the empirical level (Becker, Citation1962; Breton, Citation2015; Ployhart et al., Citation2014 and Ployhart & Moliterno, Citation2011; Qadri & Waheed, Citation2014; Schultz, Citation1961). Further, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to propose HCVA as a valid and reliable approximation for firm-level HCR investment when relying on the argument that employees contribute to firm value creation in the longer term. We find that the theoretically proposed measurement tool, firm value creation via employees (Lev, Citation2000; Turner, Citation2005) is a highly suitable indicator to reflect the investment in HCR, whereas the use of the widely adopted measure, HRE (Lajili & Zéghal, Citation2006; Samudhram et al., Citation2014), could generate misleading results.

Managerial implications

Our study has important implications for managers, investment communities, employers, employees, and regulators in the field, in general, and across the globe. The redistribution of the value created in firms among key stakeholders appears to be increasingly unequal, and this has significant impacts not only on business firms, but on society and the economy in general as well (Lev, Citation2000). We highlight the need for employers to reconsider the practice of viewing HR spending as an expense to be curtailed, and instead support a higher wealth allocation to employees, in order to generate better longer-term performance.

Investors would be in a better position to identify firms with a longer-term focus on performance by monitoring the proportion of their investment in employees and the value added allocated to the employees. Hence, exploitable trading strategies could be formulated, as firms with a longer-term focus will generally witness a gradual increase in their capitalization value in a perfect market. Regulators could gain insights to develop more equitable measures reflecting HCR investment through our analysis of the longer-term focus of firms allocating more wealth to employees as part of their HRM practices promoting organizational performance (Fu et al., Citation2017). We confirmed that the ‘human asset [is] responsible for a high share of company wealth’ (Baruch, Citation2000, p. 73), which by implication needs to be appropriately accounted for.

Finally, accounting professionals are advised to consider reinstating the value-added statement via accounting practices, as it continues to reflect social reality. The value-added statement is a practical, effective, efficient, and reliable reporting instrument for integrated reporting, as it highlights the attribution of a firm’s value to the main stakeholders contributing to it. (Haller et al., Citation2018; Vithana et al., Citation2021). The value added statement was instrumental in the development of the proposed measure, HCVA, which has been empirically tested in the current study.

Agenda for future research

Future studies may seek empirical confirmation for our findings by focusing on industry and sector variance. This could provide a foundation for expanding the current study for industry-level, firm-size related, and country comparisons. As an example: How do different industries balance near-term vs. longer-term focus in relation to HCR investment? Further studies may also aim at comparative analysis of near-term and longer-term HCR investment decisions made during the start-up/initial public offering stage, versus during a business failure stage or high versus low growth stages, to identify more implications from the current literature.

Conclusion

Employing alternative measures of HCR valuation and an accounting-based valuation model (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000; Bushee, Citation2001), we investigated how economic short-termism in HCR investment decisions aligns with firms’ longer-term and near-term earnings. Our findings inform scholars and practitioners that the current accounting information system is inadequate to communicate information on firms’ investment in HCR, and can actually distort the ‘true and fair’ view of financial statements. We suggest a value creation approach to measuring firm-level investment in employees.

Our main conceptual contribution is that, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to examine the near-term and longer-term impact of firm level HCR investment on firm valuation, and the first to propose HCVA as a proxy for firm-level HCR investment. This is a valid and reliable approximation for firm-level HCR investment when relying on the argument that employees contribute to firm value creation in the longer term. We are also the first to test HRE and HCVA using a widely recognized accounting-based valuation model (Abarbanell & Bernard, Citation2000). Using this model, we empirically test the stock markets’ reaction to firms’ investment in their HC resources, revealing that firms allocating more value added to their employees are more sustainable and longer-term focused. Although voluminous literature establishes this premise, to the best of our knowledge, to date, it has not been empirically verified through a rigorous statistical analysis, making this paper a pioneering attempt to do so.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The statement of value added illustrates how the firm value added, or the difference between the output and input, is divided among the four key categories of stakeholders: shareholders, debt holders, government, and employees. HCVA measures the value added allocated to the employees as a portion of the total value added for the firm.

2 The near-term and the longer-term earnings are defined based on the approach adopted by Abarbanell and Bernard (Citation2000) in which the firm life span is divided into time horizons: near-term and longer-term. The immediate first accounting year is considered as the near-term period for the empirical analysis, and the period beyond the immediate year is defined as the near-term to infinity (the period beyond the immediate first year to an infinite number of years in this empirical analysis) is considered as the longer-term horizon.

References

- AAA. (1973). Report of the committee on human resource accounting. The Accounting Review, 48, 169–185.

- Abarbanell, J., & Bernard, V. (2000). Is the U.S. stock market myopic? Journal of Accounting Research, 38(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.2307/2672932

- Andersén, J. (2021). Resource orchestration of firm-specific human capital and firm performance—the role of collaborative human resource management and entrepreneurial orientation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(10), 2091–2123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579250

- Angrave, D., Charlwood, A., Kirkpatrick, I., Lawrence, M., & Stuart, M. (2016). HR and analytics: Why HR is set to fail the big data challenge. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12090

- Antia, M., Pantzalis, C., & Park, J. C. (2010). CEO decision horizon and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(3), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.01.005

- ASSC. (1975). The corporate report: A discussion paper published for comment: Accounting Standards Steering Committee of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales.

- Baruch, Y. (2000). HR accountancy: The issue can no longer be ignored. The International Journal of Applied Human Resource Management, 1(1), 66–76.

- Baruch, Y., & Vardi, Y. (2016). A fresh look at the dark side of contemporary careers: Toward a realistic discourse. British Journal of Management, 27(2), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12107

- Bassi, L., & McMurrer, D. (2005). What to do when people are your most important asset. Handbook of Business Strategy, 6(1), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/08944310510557503

- Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human Capital. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Becker, G. S. (1993). HC: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education Chicago (3rd ed). The University of Chicago Press.

- Bedeian, A. G., & Armenakis, A. A. (1998). The cesspool syndrome: How dreck floats to the top of declining organizations. Academy of Management Perspectives, 12(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1998.254978

- Boon, C., Eckardt, R., Lepak, D. P., & Boselie, P. (2018). Integrating strategic human capital and strategic human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(1), 34–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1380063

- Boxall, P., Ang, S. H., & Bartram, T. (2011). Analysing the ‘black box’ of HRM: Uncovering HR goals, mediators, and outcomes in a standardized service environment. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1504–1532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00973.x

- Boxall, P., & Purcell, J. (2016). Strategy and human resource management (4th ed.). Macmillan.

- Breton, T. R. (2015). Human capital and growth in Japan: Converging to the steady state in a 1% world. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 36, 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2015.03.001

- Bronzini, R., & Piselli, P. (2009). Determinants of long run regional productivity with geographical spill overs: The role of R&D, human capital and public infrastructure. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(2), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2008.07.002

- Burchell, S., Clubb, C., & Hopwood, A. G. (1985). Accounting in its social context: Towards a history of value added in the United Kingdom. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10(4), 381–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(85)90002-9

- Bushee, B. J. (1998). The influence of on institutional R&D behavior investors myopic investment. The Accounting Review, 73(3), 305–333.

- Bushee, B. J. (2001). Do institutional investors prefer near-term earnings over Long run value? Contemporary Accounting Research, 18(2), 207–246. https://doi.org/10.1506/J4GU-BHWH-8HME-LE0X

- Cannon, J. N., Hu, B., Lee, J. J., & Yang, D. (2020). The effect of international takeover laws on corporate resource adjustments: Market discipline and/or managerial myopia? Journal of International Business Studies, 51(9), 1443–1477. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00370-6

- Chan, K. H. (2009). Impact of intellectual capital on organisational performance: An empirical study of the companies in the Hang Seng Index (Part 2). The Learning Organisation, 16(1), 22–39.

- Chan, L. K. C., Lakonishok, J., & Sougiannis, T. (2001). The stock market valuation of research and development expenditures. The Journal of Finance, 56(6), 2431–2456. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00411

- Chen, M., Cheng, S., & Hwang, Y. (2005). An empirical investigation of the relationship between intellectual capital and firms’ market value and financial performance. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930510592771

- Chen, H. M., & Lin, K. J. (2004). The role of human capital cost in accounting. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(1), 116–130.

- Chowhan, J. (2016). Unpacking the black box: Understanding the relationship between strategy, HRM practices, innovation and organizational performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(2), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12097

- Crocker, A., & Eckardt, R. (2014). A multilevel investigation of individual-and unit-level human capital complementarities. Journal of Management, 40(2), 509–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313511862

- Delery, J. E., & Roumpi, D. (2017). Strategic human resource management, human capital and competitive advantage: Is the field going in circles? Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12137

- Demortier, A. L. P., Delobbe, N., & El Akremi, A. (2014). Opening the black box of hr practices-performance relationship: Testing a three pathways AMO model. In Academy of Management Proceedings. (Vol. 2014, No. 1, pp. 14932). Academy of Management.

- DTI (2003a). Accounting for people - Consultation paper. Department of Trade and Industry.

- DTI (2003b). Accounting for people - Report of the taskforce on human capital management. Department of Trade and Industry.

- Duggal, R., & Millar, J. A. (1999). Institutional ownership and firm performance: The case of bidder returns. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1199(98)00018-2

- Elias, N. (1972). The effect of human asset statement on the investment decision: An experiment. Journal of Accounting Research, 10, 215–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/2489876

- Elias, J., & Scarbrough, H. (2004). Evaluating human capital: An exploratory study of management practice. Human Resource Management Journal, 14(4), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2004.tb00131.x

- Flamholtz, E. G. (1971). A model for human resource valuation: A stochastic process with service rewards. The Accounting Review, 46(2), 253–267.

- Flamholtz, E. G. (1972). Towards a theory of human resource value in formal organization. The Accounting Review, 47 (4), 666–678.

- Flamholtz, E. G., Bullen, M. L., & Hua, W. (2002). Human resource accounting: A historical perspective and future implications. Management Decision, 40(10), 947–954. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740210452818

- Flamholtz, E. G., & Main, E. D. (1999). Current issues, recent advancements, and future directions in human resource accounting. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 4(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb029050

- Fu, N., Flood, P. C., Bosak, J., Rousseau, D. M., Morris, T., & O’Regan, P. (2017). High-Performance work systems in professional service firms: Examining the practices-resources-uses- performance linkage. Human Resource Management, 56(2), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21767

- Fullana, O., González, M., & Toscano, D. (2021). The Role of Assumptions in Ohlson Model Performance: Lessons for Improving Equity-Value Modeling. Mathematics, 9(5), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9050513

- Fulmer, I. S., & Ployhart, R. E. (2014). Our most important asset” A multidisciplinary/multilevel review of human capital valuation for research and practice. Journal of Management, 40(1), 161–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313511271

- Green, J. P., Stark, A. W., & Thomas, H. M. (1996). UK Evidence on the market valuation of the research and development expenditure. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 23(2), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.1996.tb00906.x

- Haller, A., van Staden, C. J., & Landis, C. (2018). Value Added as part of Sustainability Reporting: Reporting on Distributional Fairness or Obfuscation? Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 3, 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3338-9

- Hancock, A. (2021). UK pubs and restaurants warn of staff shortage, Financial Times, April 18 2021, available at https://www.ft.com/content/f999d75d-f6ff-44e3-a20b-5281f849714b, 25th May, 2021.

- Hayek, M., Thomas, C. H., Novicevic, M. M., & Montalvo, D. (2016). Contextualizing human capital theory in a non-Western setting: Testing the pay-for-performance assumption. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 928–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.039

- Heyden, M. L., Reimer, M., & Van Doorn, S. (2017). Innovating beyond the horizon: CEO career horizon, top management composition, and R&D intensity. Human Resource Management, 56(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21730

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635–672.

- IASB (2011). IAS 19 Employee benefits. International Accounting Standards Board.

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

- Keep, E., & Storey, J. (2014). Corporate training strategies: The vital component?. In J. Storey (Ed) New Perspectives on Human Resource Management (pp. 109–125). Routledge.

- Kets de Vries, M. F. R., & Balazs, K. (1997). The downsize of downsizing. Human Relations, 50(1), 11–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679705000102

- Kilroy, S., Flood, P. C., Bosak, J., & Chênevert, D. (2017). Perceptions of High-Involvement Work Practices, Person-Organization Fit, and Burnout: A Time-Lagged Study of Health Care Employees. Human Resource Management, 56(5), 821–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21803

- Kim, Y., Su, L. N., & Zhu, X. K. (2017). Does the cessation of quarterly earnings guidance reduce investors’ short-termism? Review of Accounting Studies, 22(2), 715–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9397-z

- Lajili, K., & Zéghal, D. (2006). Market performance impacts of human capital disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25(2), 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2006.01.006

- Laverty, K. J. (1996). Economic “Short-Termism”: The debate, the unresolved issues, and the implications for management practice and research. Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 825–860.

- Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (1999). The human resource architecture: Toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.1580439

- Lev, B. (2000). Intangibles: Management, measurement and reporting. Brookings Institution Press.

- Lev, B., & Schwartz, A. (1971). On the use of the economic concept of human capital in financial statements. The Accounting Review, 46(1), 103–112.

- Lev, B., & Schwartz, A. (1972). On the use of economic concept of human capital in financial statements: A reply. The Accounting Review, 47(1), 153–154.

- Likert, R. (1967). The human organization: Its management and values. McGraw-Hill.

- Mabey, C., & Ramirez, M. (2005). Does management development improve organizational productivity? A six-country analysis of European firms. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(7), 1067–1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500143931

- Messersmith, J. G., & Guthrie, J. P. (2010). High performance work systems in emergent organizations: Implications for firm performance. Human Resource Management, 49(2), 241–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20342

- Millar, C. C., Chen, S., & Waller, L. (2017). Leadership, knowledge and people in knowledge-intensive organisations: Implications for HRM theory and practice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(2), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244919

- Mirvis, P. H., & Macy, B. A. (1976). Accounting for the costs and benefits of human resource development programs: An interdisciplinary approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1(2-3), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(76)90022-2

- Nixon, B. (1997). The accounting treatment of research and development expenditure: Views of UK company accountants. European Accounting Review, 6(2), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/713764720

- Nyberg, A. J., Moliterno, T. P., Hale, D., Jr, & Lepak, D. P. (2014). Resource-based perspectives on unit-level human capital: A review and integration. Journal of Management, 40(1), 316–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312458703

- Ohlson, J. A. (1995). Earnings, book value and dividends in equity valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(2), 661–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1995.tb00461.x

- Pennings, P., Keman, H., & Kleinnijenhuis, J. (1999). Doing Research in political science: An introduction to comparative methods and statistics. Sage.

- Pfeffer, J. (1997). Pitfalls on the road to measurement: The dangerous liaison of human resources with the ideas of accounting and finance. Human Resource Management, 36(3), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199723)36:3<357::AID-HRM7>3.0.CO;2-V

- Ployhart, R. E., & Moliterno, T. P. (2011). Emergence of the human capital resource: A multilevel model. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0318

- Ployhart, R. E., Nyberg, A. J., Reilly, G., & Maltarich, M. A. (2014). Human capital is dead; long live human capital resources!. Journal of Management, 40(2), 371–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313512152

- Pulic, A. (1998). Measuring the performance of intellectual performance in knowledge economy. Paper presented at the The 2nd McMaster world congress on measuring and managing intellectual capital by the Austrian team for intellectual potential.

- Pulic, A. (2000). VAIC – An accounting tool for intellectual capital management. International Journal of Technology Management, 20(5/6/7/8), 702–214. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2000.002891

- Qadri, F. S., & Waheed, A. (2014). Human capital and economic growth: A macroeconomic model for Pakistan. Economic Modelling, 42, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.05.021

- Roslender, R., Marks, A., & Stevenson, J. (2015). Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: Conflicting perspectives on the virtues of accounting for people. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 27, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2014.06.002

- Roslender, R., & Stevenson, J. (2009). Accounting for People: A real step forward or more a case of wishing and hoping? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20(7), 855–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2007.02.003

- Sampson, R. C., & Shi, Y. (2020). Are US firms becoming more short-term oriented? Evidence of shifting firm time horizons from implied discount rates, 1980–2013. Strategic Management Journal, 1–33, https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3158

- Samudhram, A., Stewart, E., Wickramanayake, J., & Sinnakkannu, J. (2014). Value relevance of human capital based disclosures: Moderating effects of labor productivity, investor sentiment, analyst coverage and audit quality. Advances in Accounting, 30(2), 338–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2014.09.012

- Schmidt, M. (1997). Determinants of Social Expenditure in Liberal Democracies. Acta Politica, 32, 153–173.

- Schultz, T. W. (1960). Capital formation by education. Journal of Political Economy, 68(6), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1086/258393

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1–17.

- Schwan, E. S. (1976). The effect of human resource accounting data on financial decisions: An empirical test. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1(2-3), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(76)90024-6

- Teague, P., & Roche, W. K. (2014). Recessionary bundles: HR practices in the Irish economic crisis. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(2), 176–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12019

- Toulson, P. K., & Dewe, P. (2004). HR accounting as a measurement tool. Human Resource Management Journal, 14(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2004.tb00120.x

- Turner, G. (2005). Accounting for human resource quo vadis. International Journal of Environmental. Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability, 1(3), 11–17.

- Tzabbar, D., Tzafrir, S., & Baruch, Y. (2017). A bridge over troubled water: Replication, integration and extension of the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance using moderating meta-analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 24(1), 134–148.

- Vithana, K., Soobaroyen, T., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). Human resource disclosures in UK corporate annual reports: To what extent do these reflect organisational priorities towards labour? Journal of Business Ethics, 169(3), 475–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04289-3

- Wright, P. M., & McMahan, G. C. (2011). Exploring human capital: Putting ‘human’ back into strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Journal, 21(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00165.x

- Youndt, M. A., & Snell, S. A. (2004). Human resource configurations, intellectual capital, and organizational performance. Journal of Managerial Issues, 16(3), 337–360.

- Zula, K. J., & Chermack, T. J. (2007). Integrative literature review: Human capital planning: A review of literature and implications for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484307303762