Abstract

This paper empirically examines the impact of organisational psychological support on employees’ outcomes as an example of the ‘Common Good HRM’ model on the well-being – performance continuum of police officers, using a Conservation of Resources (COR) theoretical framework.

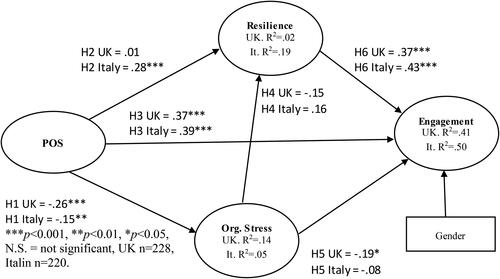

The study uses Structural Equation Modelling to analyse data from 220 Italian police and 228 English police officers to compare the impact of Perceived Organisational Support (POS) on organisational stress, employees’ resilience, and engagement. The findings show that low Perceived Organisational Support (POS) leads to high stress, which then comprises employees’ resilience and likely demotivates them from being engaged on the job, explaining approximately half of their engagement. Stress and resilience also mediate the relationship between POS and engagement. COR theory explains that when POS is low, employees perceive a resource loss spiral which compromises their wellbeing, and consequently, police officers’ engagement is low. The contribution of this paper is that it shows how organisational support is an integral part of managing emotional labour and therefore demonstrates how the ‘Common Good HRM’ model has the potential to protect emotional labour more effectively.

Introduction

For the past two decades the ‘ability, motivation and opportunity’ (AMO) model has been used in HRM to explain the link between Human Resource Management (HRM) and performance. The assumption underpinning AMO is that high employee performance is a function of HR interventions aimed at improving their existing capabilities via, for example, targeted selection, training, and empowerment and performance management processes so as to create ideal working opportunities for them to succeed (Bos-Nehles et al., Citation2013). From this framework, HR scholars have attempted to demonstrate that management can enhance employees’ work behaviours via soft HRM (such as training) and the implementation of high-performance work systems (HPWS).

However, the financial crisis and subsequent austerity derived management models have driven a significant shift towards more hardline HRM models as uncertainty becomes almost routine. As part of the change, Wilkinson and Wood (Citation2017, p. 2511) argue that ‘the relative power of employees has not increased since at least the 1970s, and in a large proportion, this has significantly diminished’. Hence, there are now growing concerns that HRM has failed to act as the employee’s champion during the change (Ulrich, Citation2016), and as a consequence, the ‘potential trade-offs’ between employee wellbeing and employee performance outcomes have been neglected by HRM scholars (Peccei & Van De Voorde, Citation2019).

The gap is further exacerbated when considering particular types of labour where the nature of employees’ work tasks coupled with the existing work conditions means that the potential trade-offs between employee wellbeing and employee performance outcomes are amplified. In particular, employees working within Street Level Bureaucracies (SLBs) delivering emergency services (such as police officers), are constantly juggling to cope with the increasing demands for their services, organisational deadlines, red tape, and the high levels of emotional labour required in delivering services (Brunetto et al., Citation2014; Farr-Wharton et al., Citation2021).

Emotional labour refers to the process of internalising real emotions whilst presenting an emotion to the public that is significantly different (surface acting) (Hochschild, Citation1983). This is important because of how it affects the employee. In particular, the undertaking of emotional labour causes emotional dissonance, which occurs because of the incongruence between personal feelings and the expected ‘official’ emotions (Grandey, Citation2000). Employees can respond by either engaging in surface acting, deep acting or a genuine expression of feelings (Grandey, Citation2000). When employees engage in surface acting, they suppress their real feelings and instead display behaviour in line with organisational expectations. On the other hand, when employees engage in deep acting, employees adjust their real feelings in line with organisational expectations. Grandey and Gabriel (Citation2015) further clarified emotional labour by explaining that it involves internal processes of emotional awareness and emotional regulation, and an external process which involves the expression of an emotion. In contrast to deep acting, which generates very little emotional dissonance, surface acting causes varying degrees of emotional dissonance which can negatively impact the physical and psychological well-being of employees over time, in turn, increasing the likelihood of negative job-related attitudes.

Police officers regularly use emotional labour in servicing the public. However, their high levels of stress and reduced wellbeing (Purba & Demou, Citation2019) suggest that they predominantly use surface acting which leads to emotional dissonance (Grandey & Gabriel, Citation2015). These issues have implication for HRM research and practice. Cooke et al. (Citation2021, p18) argue for ‘… more employee well-being oriented HRM research in times of uncertainty and crises’ and Peccei and Van De Voorde (Citation2019) argue that there is a ‘blackbox’ in understanding which HR models can promote both employee wellbeing and performance outcomes sustainably. The way forward, according to Kramar (Citation2014, p. 1085), is ‘… a new approach to managing people … through its recognition of the complexities of workplace dynamics and the explicit recognition of the need to avoid negative impacts of HRM practices’.

This paper empirically examines the impact of organisational psychological support within the ‘Common Good HRM’ model (Aust et al., Citation2019, p5) on developing ‘an organizational culture of common good values and introducing HR practices based on such values as dignity, solidarity, and reciprocity’ for those managing employees who undertake high levels of emotional labour, especially during emergencies. Common Good HRM is underpinned by four principles: (1) HR practices should address specific SDG(s), such as employee wellbeing (United Nations (UN), Citation2020); (2) the workplace context should be characterised by “equal and fair” treatment’; (3) democratic relationships that promote employee engagement and (4) uphold the psychological contract being held in common good HRM models. Most importantly, employees should be guaranteed adequate ‘… security, safety, and meaningful work’ (Aust et al., Citation2019, p. 9). The concept of organisational psychological support is already captured in the Common Good Model somewhat, although not explicitly examined empirically. For example, principle 2 stipulates that relationships should be equal and fair and Perceived Organisational Support (POS) measures whether employees perceive their relationships with their employing organisation are fair. Additionally, the fourth principle establishes the importance of the psychological contract in promoting the wellbeing-continuum by ensuring the wellbeing of employees.

Employee resilience and wellbeing are significantly related (Hu et al., Citation2015; Tonkin et al., Citation2018) and within Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, Chen et al. (Citation2015) posits that workplace stress is the antithesis of resilient employees with high wellbeing. Resilience is a personal attribute that some people have, and some do not. Those who have resilience possess a personal psychological capability to rebound in the face of challenging adversities and can, therefore, navigate and manage crises effectively (Cooke et al., Citation2019; Luthans et al., Citation2006). Resilient employees are also likely to have the ‘behavioural capability to leverage work resources in order to ensure continual adaptation, well-being, and growth at work, supported by the organization’ (Kuntz et al., Citation2017, p. 224). According to Cooke et al. (Citation2019), resilient employees may also be linked to engaged employees, with resilient employees being the most engaged. Engaged police officers are those that demonstrate dedication and vigour in doing their job, and therefore they have high work performance outcomes (Brunetto et al., Citation2020). The question remains whether employee resilience can be enhanced or negated by organisational actions. Scholars argue that it is the responsibility of HRM to ensure that organisational policies and programs, and management actions support positive outcomes of their employees (Guest, Citation2017).

Despite policy statements in many organisations that identify the importance of supporting employees, police and emergency services employees remain over-identified in stress-related illnesses statistics and it remains a significant cause of high absenteeism and turnover (Dunn et al., Citation2015; Public Health England, Citation2015; Purba & Demou, Citation2019). Employees perceive the role of HRM through the behaviours of organisational management, especially their line managers (Brunetto et al., Citation2020). However, Cordner (Citation2016) argues that managers use their power to increase bureaucracy and red tape as a way of soliciting compliant behaviour from police officers and Cronin et al. (Citation2017) argue that the command hierarchical structure lends itself to ‘sanction’ the use of poor management practices. Hence, police officers have to use emotional labour daily to negotiate emotionally challenging interactions with their multiple stakeholders (such as perpetrators, victims, line managers, colleagues and the court system) that involve them hiding their true feelings, and instead communicating in an officially sanctioned manner (Farr-Wharton et al., Citation2021; Wankhade, Citation2021), which leads to emotional dissonance and increases their exposure to stress-related illnesses (Grandey & Gabriel, Citation2015). Unlike other types of emergency workers, police officers are potentially exposed to violence daily and are subsequently at greater risk of personal injury, which is further compounded by their responsibilities associated with protecting the public and carrying firearms (Purba & Demou, Citation2019). However, similar to most types of emergency workers, police officers are increasingly subject to austerity-driven funding and management models, which exposes them to high work harassment and intensity, and subsequently reduced wellbeing (Brunetto et al., Citation2014; Hesketh, et al., Citation2017). According to Bakker (Citation2015), continual under-resourcing negatively impacts motivation and engagement no matter how committed employees are to their profession. Consequently, Purba and Demou (Citation2019, p. 1) argue that:

Policing is one of the most stressful occupations as maintained by academic researchers, police practitioners, health-care professionals and psychologists and it ranks in the top three occupations in the Occupational Disease Intelligence Network (ODIN) system for Surveillance of Occupational Stress and Mental Illness (SOSMI)… [and some scholars argue that this makes them] … more resilient to stress than civilians.

RQ1: What is the impact of POS on police officers’ stress, resilience and engagement?

RQ2: What are the similarities and differences of the impact of POS on Italian and English police officers’ stress, resilience and engagement?

Background and hypotheses development

Conservation of resources theory (COR)

Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) has become one of the major approaches to understanding the impact of motivation on burnout and traumatic stress in the workplace. It theorises that employees make choices about work engagement based on their access to physical, psychological, social, organisational and personal resources (Hobfoll, Citation2011). The core principle is that ‘individuals (and groups) strive to obtain, retain, foster, and protect those things they centrally value’ (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018, p. 106). When employees cannot protect themselves, they become stressed because central or key resources are (a) threatened with loss, (b) lost, or (c) when there is a failure to gain central or key resources following significant effort. According to Chen et al. (Citation2015, p. 96) ‘COR theory posits, where resource loss is salient, negative consequences will outweigh positive outcomes. Indeed, thriving and resilience are fostered by circumstances where people are able to apply, grow, and sustain their personal, social, and material resources’. Four types of resources are identified by Hobfoll (Citation2001), namely: objects, conditions, personal attribute and energy which impact individuals.

The relevant COR principle explaining behaviour in this paper is that a perceived loss of resources causes a disproportionately greater impact than a resource gain. The relevant corollary that explains employee behaviour follows that an initial perceived loss of resources is likely to be followed by further perceived losses leading to a loss spiral. Over time, the impact of a continual resource drain is likely to cause a defensive, aggressive or even irrational response once resources are exhausted. Organisational levers such as culture and access to organisational support (or lack of support) provided by managers and policies either provide ‘support’ resources – called ‘resource caravan passageways’ or erodes such a foundation for resource maintenance or gain (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018).

The argument presented in this paper is that organisations decide on the quality of the resource caravan passageways in the form of POS (from policies and management practices), which then establishes a dynamic of negating or increasing the stress perceived in navigating policing, in turn affecting their resilience. Over time, these processes trigger or dampen the motivational component of the AMO framework, either encouraging or discouraging police officers to fully engage in job tasks in England and Italy.

If POS is low, police officers may perceive increased stress, which may then negatively impact their resilience and compromise their performance (captured by examining their engagement). This is important since police work has been identified as physically demanding and emotionally challenging, and recent evidence suggests a correlation between perceived support and employee wellbeing (Farr-Wharton et al., Citation2021). However, to the best knowledge of the authors, the impact of POS on their resilience has never been examined previously. The next section discusses how POS applies to the policing context and its association with employee resilience and engagement.

Perceived organisational support (POS)

POS refers to employees’ perception of organisational support. A high POS signifies that employees perceive supportive policies and management practices (Brunetto et al., Citation2020; Farr-Wharton et al., Citation2018). Low POS promotes poor workplace relationships, which then leads to low engagement (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017), although the relationship has not been tested for roles requiring emotional labour. POS tends to be higher in those public organisations that have implemented New Public Management (NPM) reform that empowers employees in workplace decision-making roles (managers) (Rodwell et al., Citation2011).

Previous research has found an association between POS and higher discretionary power for police officers (Brunetto et al., Citation2014). In a comparative study of police officers in Australia, USA and Malta, Brunetto et al. (Citation2020) found that low quality POS was associated with low engagement. However, the link between POS, stress and engagement was not examined. It may be that the underpinning factors linking POS to engagement are that low POS may trigger increased stress, which then reduces employee resilience and compromises their engagement.

Stress

According to COR theory, stress is an individual’s reaction to a loss of perceived resources (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Emergency workers such as the police and paramedics are constantly exposed to emotional and critical incidents, heightening their levels of stress and anxiety (Granter et al., Citation2019; Heath et al., Citation2021). MIND (Citation2019), the mental health charity, concludes that more than 85 per cent of emergency services staff have experienced stress and poor mental health issues at work. The nature of emergency work is that they do not get advanced warning to prepare and deal with the operational and emotional demands of their jobs, which then increases their propensity to affect their ability to cope with the emergencies because they become ‘overwhelmed’ (Tehrani & Hesketh, Citation2019, p. 2).

Additionally, emergency workers tend to work in public organisations driven by austerity-driven funding and management models (Farr-Wharton et al., Citation2021) and hence are exposed to long working hours, especially in the case of UK police officers. In particular, Turnbull and Wass (Citation2015) found that UK police regularly worked in excess of the maximum of 48 hours per week regulation. Hence, for police officers, stress can come from the working environment (operational and occupational stressors) or exposure to emotional or critical incidents (Wankhade et al., Citation2020). This means that police officers need POS to help them cope with a range of experiences including a terrorist incident or apprehending a dangerous criminal, as well as negotiating red tape and subsequent organisational stressors (Farr-Wharton et al., Citation2016). Police services across the globe are expected to operate efficiently during periods of great uncertainty, and the many challenges associated with policing during the COVID-19 pandemic heightened their levels of stress and anxiety (Drew & Martin, Citation2020; Laufs & Waseem, Citation2020).

Using a COR theoretical framework, the argument presented is that POS is an example of a resource caravan passageway (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018), and depending on how supportive the policies and management practices are in assisting police officers to cope with operational and organisational stressors, the outcomes will be different. If POS is low, police officers may perceive a continual drain on their resources to cope – leading to a spiral loss (third corollary). If the perceived loss in resources is considered chronic, then the fourth corollary may occur with negative consequences such as high levels of burnout, divorce, drug-abuse and suicide as well as a rise in a range of health problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, mental and somatic problems, injuries or fatal accidents (Boxall & Macky, Citation2014; Dunn et al., Citation2015; Wankhade & Patnaik, Citation2019). Hence, it is expected that low POS is associated with high stress amongst police officers.

H1: Low POS is associated with high stress levels of police officers

Resilience

The term ‘organisational resilience’ originated from the crisis management literature. Previous research has mainly focused on the macro level in relation to how well organizations can adopt new models of delivery and reconfigure their structure, especially in the public sector where the backdrop is massive reductions in public funding (Duit, Citation2016; Wankhade et al., Citation2019). Duit (Citation2016) argues that since organizations are made up of employees, the gap in the literature is understanding the factors that affect employees’ resilience, since organisational resilience is a function of the cumulative impact on the resilience of individual employees. According to Britt et al. (Citation2013, p. 6) individual resilience refers to ‘the demonstration of positive adaptation in the face of significant adversity’. Since Kuntz et al. (Citation2017) argue that a supportive organisational environment provides a nurturing culture and leadership, which enables the development of employee resilience, we expect that high POS will be associated with high resilience. In terms of the first principle of COR theory, when employees perceive that a loss of resources is likely, the impact of a resource gain is greater and those who perceive the most resources cope the best (Hobfoll, Citation2011). For this reason, it is expected that high POS is associated with high resilience.

H2: High POS is associated with high employee resilience.

Additionally, there is emerging research that positive emotions and high wellbeing are antecedents of resilience (Kuntz et al., Citation2017; Ong et al., Citation2006, Citation2010) and Britt et al. (Citation2016) conceptualises adverse events (either operational or organisational in origin) as stressors in showing the link between stress and resilience generally. However, the relationship between stress and resilience has not been examined for police officers. In terms of COR theory, a spiral loss is likely when employees perceive high stress continuing, which is likely to erode their resilience. The expectation is that high stress will be associated with low resilience.

H3 High stress is associated with low resilience.

On the other hand, just as personal factors such as positive emotions and high wellbeing were found to mediate the impact of stressors (Ong et al., Citation2006, p. 2010), it is expected that stress will mediate the relationship between POS and resilience, with high stress negatively impacting the relationship, and low stress positively impacting the relationship. High POS is likely to enhance employee resilience by offering supportive management, a positive learning culture and a supportive work environment (Kuntz et al., Citation2016; Näswall, et al., Citation2015). In contrast, when organisations fail to provide support to reduce employee stress, then it seems likely that it will negatively impact employees’ resilience. Hence, it is expected that employees’ stress levels are likely to mediate the relationship between POS and employee resilience because it affects whether they perceive a resource gain or loss spiral (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018).

H4: Stress mediates the relationship between POS and resilience.

Engagement

All organisations want their employees to energetically engage in work tasks. They want employees to perceive the work as meaningful and, as a consequence, to perform efficiently and effectively. According to Brunetto et al. (Citation2020, p.755), who compared the impact of POS on the engagement of police officers in Australia, the USA and Malta, ‘… the engagement of police officers is arguably compromised by poor management’. It is, therefore, expected that low POS will be associated with low engagement for police officers in the UK and Italy.

H5: Low POS is associated with low engagement.

However, the reasons underpinning why poor POS compromises employee engagement has received far less attention. Using COR theory, it seems likely that if POS is high, then the supportive environment operates as a resource caravan passageway. Specifically, that is a workplace environment that is conducive to further resource gains. Past research suggests that if employees perceive high levels of organisational resources, it is likely to enhance their perception of personal resources and enhance their engagement (Bakker, Citation2015). Hence, we propose that resilience mediates the relationship between POS and engagement.

H6: Resilience mediates the relationship between POS and engagement.

According to Parul and Pooja (Citation2020), employees with high resilience also have high engagement. They argue that this is because employees with high resilience promote positive attitudes towards work, enhancing work engagement. Hence, we intend to replicate this research for police officers.

H7: High resilience is associated with high engagement.

There is existing research that shows the relationship between stress and resilience (Dunn et al., Citation2015; Harms et al., Citation2018). Their research shows that when organisations embed strategies to increase employee resilience, the consequences of stress (burnout and attrition) can be reduced. Using COR theory to underpin their study, Parul and Pooja (Citation2020) found that those employees who use their positive emotions as a resource likely trigger a ‘resource gain spiral’. Consequently, employees use personal resources to increase their resilience in coping with workplace challenges and motivating their engagement in the workplace. However, employees’ reservoir of personal resources is finite, and it is an organisation’s responsibility to embed processes that likely ‘… support their employees in becoming resilient…’ (Parul & Pooja, Citation2020, p. 17) because it benefits organisations to have employees able to cope with stressful work conditions, especially in terms of their higher work engagement. We test these premises for police officers.

H8: Low stress is associated with high employee engagement.

H9: Stress mediates the relationship between resilience and engagement.

The similarities and differences in the policing context in the UK and Italy

Policing is typical of most emergency services in that it is largely a public sector endeavour. This means that the differential implementation of reforms across different countries underpins the organisational context in which policing occurs. In particular, core-NPM countries (such as Australia, the USA and UK) were expected to experience much greater levels of management reform than NPM laggards (such as Italy and Malta) (Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011). However, Brunetto et al. (Citation2020) found low levels of satisfaction with POS across both the USA and Australia (examples of core-NPM countries) as well as Malta (example of NPM laggard), suggesting the strong negative impact of austerity-driven management practices across countries. We, therefore, expect low POS for both Italian and UK police officers.

H10: Italian and UK police officers have low POS.

On the other hand, Farr-Wharton et al. (Citation2021) found there were differences in the police officers’ outcomes of NPM laggard countries such as Italian police compared with the outcomes of UK police officers. Specifically, Italian police officers perceived higher wellbeing and affective commitment, inferring that they likely had access to more organisational support resources, in turn providing them with better resource caravan passageways. We, therefore, expect that Italian police officers will have lower stress, higher resilience and engagement.

H11: Italian police officers have higher resilience and engagement and lower stress.

Together, these hypotheses form the model which guides data collection and analysis.

Methods

This study involves a latent model invariance testing using structural equation modelling to test the hypotheses and compare the impact of POS on organisational stress, resilience and engagement, across UK and Italian police forces. The study uses cross-sectional data from a self-completed anonymous questionnaire distributed to police officers in England and northern Italy. Ethical clearance was obtained from relevant university ethics committees.

Sample

The UK sample comprised police officers from a large police force in England. Over 600 surveys were distributed, and in return, a total of 228 completed survey were received (a response rate of 38%). Analysis of statistical outliers indicated that all items displayed appropriate normality evidenced by skewness and kurtosis scores of between −2 and +2. 61.4 per cent of the sample were male, with the remaining 38.6 per cent identifying as female. Almost 50 per cent of the respondents were aged less than 33 years, 38 per cent were between the ages of 34–47 years, and approximately 10 per cent were over 48 years old. The ranks consisted of 92 per cent frontline constables and 8 per cent sergeants and inspectors.

Similarly, Italian police officers attending training in one region of Italy over a 12-month period during 2018 and 2019 were targeted. The type of police targeted were Italian National Police (Polizia di Stato) because, similar to the UK sample, their main task is national security, including the maintenance of public order to prevent crime. Over 700 surveys were distributed, and in response, 220 usable surveys were returned (a response rate of 31%). The majority of the respondents were male (n = 165, 75%) and the majority (n = 122, 56%) were aged over 48 years. The majority of police officers (61%) were constables.

Instruments

A six-point Likert scale was used for all survey items, with ‘1′ representing ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘6′ representing ‘strongly agree’. Six-point Likert scales have been shown to have preferential normality in comparison to five-point scales (Leung, Citation2011) and higher trends of discrimination and reliability (Chomeya, Citation2010). The POS instrument comprised the 8-item validated scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (Citation1997). A typical question included ‘My organisation cares about my opinion’. The engagement instrument comprised the 9-items validated scale developed by Schaufeli et al. (Citation2002). A typical item is ‘When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work’. The resilience instrument comprised 3-items from the shortened Psychological Capital scale developed by Lorenz et al. (Citation2016). shows the acceptable factor loadings for the items.

Table 1. Factor loadings for the Resilience scale for the UK and Italian sample.

The organizational stress instrument comprised 6-items capturing organisational stress from the Police Stress Scale developed by McCreary and Thompson (Citation2006). shows the acceptable factor loadings for each item for the UK and Italian sample.

Table 2. Factor loadings for the Stress scale for the UK and Italian sample.

Analysis

Instrument reliability, discriminant and convergent validity were tested through an exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) process. The initial CFA model for both the UK and Italian sample displayed adequate model fit properties. First, we adhered to Hu and Bentler’s (Citation1999) model fit prescriptions, including chi-square (χ2) between 1 and 3, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) close to .06, and Corrected Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) greater than .90. For the UK sample, the model fit the data well χ2(df) = χ2, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.94 and TLI = 0.93. For the Italian sample, χ2(df) = χ2, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.93 and TLI = 0.92. The composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE – a measure of convergent validity), maximum-squared variance (MSV – an indicator of discriminant validity) for both the UK and Italian sample is displayed in . For these to be valid, the CR needs to be above .7, the AVE needs to be above .5, and the MSV needs to be less than the AVE – in this case, all constructs proved robust. A Harmon’s Single Factor Test was utilised (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012) to test the extent of common method bias. The results indicate that in the UK data, 32 per cent of the variance was explained by one factor. For the Italian data, 31 per cent of the variance was explained by one factor, indicating a low likelihood of common method variance in both cases. However, the generalisability of the study is limited by common method variance (CMV) because of the use of cross-sectional self-report survey data.

Table 3. UK – Italy: the composite reliability, average and maximum-squared variance.

Results

As the data was robust in terms of reliability, validity, normality and common method variance tests, latent mean equivalent testing was undertaken. Latent mean equivalent testing may be conceptualized around three analytical steps (Byrne, Citation2016). The first step compares the equivalence of factor loadings across the two groups. Two measures are typically compared to ascertain whether the factor loadings are substantially different across the two groups – the Δ χ2/df, and the ΔCFI. For the constrained model, the Δ χ2/df was 28.324/21, which is not significant; further, the ΔCFI was .006, lower than the recommended cut off of .01 prescribed by Byrne (Citation2016). Byrne (Citation2016) argues that the Δ χ2/df is much more sensitive to variation than the ΔCFI, and as a result, recommends ΔCFI as a more appropriate tool for comparisons factoring in low sample sizes. The conclusion from this test is that the factor loads are not significantly different across the two groups. The final step of analysis examined the differences in the path models between the two groups. below highlights the standardised regression weights of the hypothesized paths for both samples.

The Δ X2/df of the constrained and unconstrained model was 5015.053/30, which is significant (p=.000), meaning that a significant difference between UK and Italian path models is observed.

The second step in latent mean equivalent testing examines the mean differences of the latent constructs across the two groups. highlights the mean difference between the UK and Italian samples. highlights the direct and indirect effects between the UK and Italian samples.

Table 4. Mean comparison: UK to Italy.

Table 5. Direct and indirect effects.

The analysis indicates that the latent means are significantly different. The UK sample noted substantially lower POS, resilience and engagement scores, and higher organisational stress, confirming H11 and rejecting H10. The final step examines the differences in the path models between the two groups. highlights the standardised regression weights of the hypothesised paths for both samples, in addition to the R2 values, and the outcomes of each hypothesis. indicates the results from the bootstrapped mediation testing method, highlighting the direct and indirect effects. confirms all hypotheses, although the direct effects were masked via the mediation processes for H4 and H5. In particular, the relationship between POS and resilience was fully mediated by stress for the UK sample and partially mediated for the Italian sample. Additionally, the relationship between stress and engagement is fully mediated by resilience for the Italian sample and partially mediated for the UK sample.

Discussion

This paper empirically examined the impact of POS as an example of a ‘psychological support mechanism’ within the ‘Common Good HRM’ model (Aust et al., Citation2019) to ensure a sustainable balance in the trade-off between employee wellbeing and performance when managing emotional labour. The wellbeing – performance continuum has been largely neglected by HRM scholars (Cooke et al., Citation2021; Peccei & Van De Voorde, Citation2019), with detrimental effects for such employees in terms of stress-related illnesses (Drew & Martin, Citation2020; Dunn et al., Citation2015; Public Health England, Citation2015).

The study used two research questions and eleven hypotheses to demonstrate the importance of organisational support on the stress, resilience and engagement of police officers, as a means of understanding the dynamics involved in the wellbeing- performance continuum. The findings indicate that low POS (which is evident in the form of unsupportive organisational policies and management practices at every level of the hierarchy), provides the context likely to promote stress, in turn reducing employee resilience to be able to bounce back from adversity. Under such conditions, the result is reduced engagement. The variance of POS, organisational stress and resilience explained approximately half of the engagement of police officers in Italy (50%) and the UK (41%). The second research question compared the similarities and differences of the impact of POS on Italian and English police officers’ stress, resilience and engagement. Whilst the means were low for both cohorts, the results show that Italian police officers had higher POS, resilience and engagement and lower stress compared with UK police officers. One explanation is that Italy is an example of an NPM-laggard, and although most countries have implemented austerity-driven funding reforms, it is core NPM countries such as the UK that have implemented the most management reforms likely to have negatively impacted POS and changed police officers’ access to a resource caravan passageway.

Overall, the findings indicate minimal evidence that police officers perceived that POS provided the organisational mechanism for delivering fairness (principle 2) and ensuring resilience (principle 4) as part of the ‘Common Good HRM’ model for police officers, especially those in England. Instead, the findings indicate minimal organisational support for English police officers in particular, in recovering from delivering emotional labour in emergencies. One explanation is that austerity-driven management practices evident in public bureaucracies, continue to erode the wellbeing – performance continuum negatively impacting how essential emergency services are delivered to the public. These findings are underpinned by COR theory (Hobfoll, Citation2011) which explains that when POS (which is an example of a resource caravan passageway) is low, police officers perceive a drain on their resources to cope – leading to a resource loss spiral. As a result, the fourth corollary became evident with police officers acting defensively to protect themselves by disengaging their energy and dedication to the job (low engagement).

Previous research by Cooke et al. (Citation2019) found a relationship between high-performance work systems, employee resilience and engagement for Chinese workers in the banking industry. In the case of English and Italian police officers, the quality of organisational support is a significant determinant of their ability to cope with the stressors caused by the operational and organisational nature of policing (Purba & Demou, Citation2019), in turn affecting their resilience and engagement (Kuntz et al., Citation2017). The continual use of austerity-driven management practices is therefore likely to further exacerbate the over-representation of emergency workers with stress-related illnesses (Drew & Martin, Citation2020; Dunn et al., 2020; Public Health England, Citation2015; Purohit, Citation2020; Tehrani & Hesketh, Citation2019), which is unsustainable long term because it erodes public value.

Implications for HRM models

Supported employees are high performers, whereas this study shows that poorly supported employees engage less. HRM models suitable for managing emotional labour should be underpinned by the principles informing Common Good HRM, particularly in targeting the improvement of employee resilience and wellbeing (principle 4), which is the third SDG (UN, 2020). Hence, HR models must ensure both physical and psychological safety (Aust et al., Citation2019) of employees, especially those over-represented in statistics about stress-related illnesses (Purba & Demou, Citation2019; Tehrani & Hesketh, Citation2019). Organisational policies already exist; it is the implementation of those policies ensuring adequate organisational support processes for employees that remains the gap. Austerity driven funding and management models will remain firmly entrenched in organisations until HR along with management adopts a paradigm shift such that they become responsible for the resilience and wellbeing of their employees – not just in terms of organisational policies, but also in terms of implementing effective organisational management support practices. Otherwise, the burden for caring for over-worked, under-supported employees remains the community instead of the organisation.

Conclusion

There are not only moral issues relating to managing emotional labour delivering emergency services, but also performance, cost and litigation implications. The link between POS, stress, resilience and engagement has been established and therefore organisations would benefit from proactively implementing support interventions to assist employees coping with stressful from delivering emergency services (Tehrani & Hesketh, Citation2019). Therefore, human resource development (HRD) strategies could be targeted towards increasing employee resilience as a means of unleashing untapped performance potential. Such strategies show promising results (Brunetto et al., Citation2020).

Implications of policing in practice

Police officers have responsibilities associated with protecting the public and maintaining law and order, and they also have the obligation of carrying and using firearms responsibly (Purba & Demou, Citation2019). On the other, SLBs have a responsibility to provide their employees with the resources they require to undertake their job effectively (Hobfoll, Citation2011). Numerous scholars argue that adequate support is one such resource which police officers need to ensure their wellbeing. In particular, Jiang (Citation2021) argues that management support should be standard for every SLB. It seems likely that police officers are experiencing the cost of surface acting causing emotional dissonance (Grandey & Gabriel, Citation2015). Without support, communities must accept realities such as more police officers’ suicide in the USA than are killed in the line of duty (Heyman et al., Citation2018). Unsupported police officers are a public concern if they are suffering the effects of stress and burnout because of the weaponry they carry. High wellbeing amongst police officers and the communities they service and are part of, requires new HRM models that standardize support for police officers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aust, I., Matthews, B., & Muller-Camen, M. (2019). Common good HRM: A paradigm shift in Sustainable HRM? Human Resource Management Review, 30, 100705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100705

- Bakker, A. B. (2015). A job demands-resource approach to public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12388

- Bos-Nehles, A. C., Van Riemsdijk, M. J., & Kees Looise, J. (2013). Employee perceptions of line management performance: Applying the AMO theory to explain the effectiveness of line managers’ HRM implementation. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 861–877. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21578

- Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2014). High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being. Work, Employment & Society, 28(6), 963–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013512714

- Britt, T. W., Shen, W., Sinclair, R. R., Grossman, M. R., & Klieger, D. M. (2016). How much do we really know about employee resilience? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(2), 378–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.107

- Britt, T. W., Sinclair, R. R., & McFadden, A. C. (2013). Introduction: The meaning and importance of military resilience. In Sinclair, R. R. & Britt, T. W. (Eds.), Building psychological resilience in military personnel: Theory and practice (pp. 3–17). American Psychological Association.

- Brunetto, Y., Dick, T., Xerri, M., & Cully, A. (2020). Building capacity in the healthcare sector: A strengths based approach for increasing employees’ well-being and organisational resilience. Journal of Management & Organization, 26 (3), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.53

- Brunetto, Y., Farr-Wharton, B., Farr-Wharton, B., Shacklock, K., Azzopardi, J., Saccon, C., & Shriberg, A. (2020). Comparing the impact of management support on police officers’ perceptions of discretionary power and engagement: Australia, USA and Malta. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(6), 738–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1375964

- Brunetto, Y., Shacklock, K., Teo, S., & Farr-Wharton, R. (2014). The impact of management on the engagement and wellbeing of high emotional labour employees. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(17), 2345–2363. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.877056

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge

- Chen, S., Westman, M., & Hobfoll, S. (2015). The commerce and crossover of resources: Resource conservation in the service of resilience. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 31(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2574

- Chomeya, R. (2010). Quality of psychology test between likert scale 5 and 6 points. Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 399–403.

- Cooke, F. L., Cooper, B., Bartram, T., Wang, J., & Mei, H. (2019). Mapping the relationships between high-performance work systems, employee resilience and engagement: A study of the banking industry in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), 1239–1222. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1137618

- Cooke, F., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2021). IJHRM after 30 years: taking stock in times of COVID-19 and looking towards the future of HR research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1833070

- Cordner, G. (2016). The unfortunate demise of police education. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 27(4), 485–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2016.1190134

- Cronin, S., McDevitt, J., & Cordner, G. (2017). Police supervision: Perspectives of subordinates. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 40(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-07-2016-0117

- Drew, J. M., & Martin, S. (2020). Mental health and wellbeing of police in a health pandemic: Critical issues for police leaders in a post-COVID-19 environment. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being, 5(2), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.35502/jcswb.133

- Duit, A. (2016). Resilience thinking: Lessons for public administration. Public Administration, 94 (2), 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12182

- Dunn, R., Brookes, S., Rubin, J., & Greenberg, N. (2015). Psychological impact of traumatic events: Guidance for trauma-exposed organisations. Occupational Health at Work, 12(1), 17–21.

- Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 812–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.5.812

- Farr-Wharton, B., Azzopardi, J., Brunetto, Y., Farr-Wharton, R., Herold, N., & Shriberg, A. (2016). Comparing Malta and USA police officers’ individual and organizational support on outcomes. Public Money & Management, 36(5), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1194078

- Farr-Wharton, B., Brunetto, Y., Wankhade, P., Saccon, C., & Xerri, M. (2021). Comparing the impact of authentic leadership on Italian and UK police officers’ discretionary power, well-being and commitment. Policing: An International Journal, 44(5), 741–755. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2020-0156

- Farr-Wharton, B., Farr-Wharton, G., Brunetto, Y., Farr-Wharton, R., Xerri, M., & Shriberg, A. (2018). Social networks, problem-solving, managers: Police officers in australia and the USA policing. An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 14(3), 778–791. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay095

- Grandey, A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.95

- Grandey, A., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Emotional labor at a crossroads: Where do we go from here? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 323–349. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111400

- Granter, E., Wankhade, P., McCann, L., Hassard, J., & Hyde, P. (2019). Multiple dimensions of work intensity: Ambulance as edgework. Work. Employment and Society, 33 (2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018759207

- Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well‐being: towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12139

- Harms, P. D., Brady, L., Wood, D., & Silard, A. (2018). Resilience and well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 1–12). DEF Publishers.

- Heath, G., Wankhade, P., & Murphy, P. (2021). Exploring the wellbeing of ambulance staff using the ‘public value’ perspective: opportunities and challenges for research. Public Money & Management, 1–11. early cite) https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1899613

- Hesketh, I., Cooper, C. L., & Ivy, J. (2017). Well-being and engagement in policing: the key to unlocking discretionary effort? Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(1), 62–73.

- Heyman, M., Dill, J., & Douglas, R. (2018). The Ruderman white paper on mental health and first responders. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/rudermanfoundation/docs/first_responder_white_paper_final_ac270d530f8bfb

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In S. Folkman (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 127–147). Oxford University Press.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press, CA.

- Hu, L.T., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1):1–55

- Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

- Jiang, Q. (2021). Stress response of police officers during COVID‐19: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender, 18(20), 116-128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1569

- Kramar, R (2014) Beyond Strategic Resource Management: Is sustainable resource management the next approach? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(8) 1069–1089.

- Kuntz, J. R. C., Malinen, S., & Näswall, K. (2017). Employee resilience: Directions for resilience development. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69 (3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000097

- Kuntz, J. C., Näswall, K., & Malinen, S. (2016). Resilient employees in resilient organizations: Flourishing beyond adversity. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9 (2), 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.39

- Kurtessis, J.N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M.T., Buffardi, L.C., Stewart, K.A., Adis, C.S. (2016). Perceived organizational support:A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884

- Laufs, J., & Waseem, Z. (2020). Policing in pandemics: A systematic review and best practicesfor police response to COVID-19. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: Ijdrr, 51, 101812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101812

- Leung, S.-O. (2011). A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(4), 412–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2011.580697

- Lorenz, T., Beer, C., Pütz, J., & Heinitz, K. (2016). Measuring psychological capital: Construction and validation of the compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12). PLoS One, 11(4), e0152892–1371. /journal.pone.0152892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152892

- Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G., & Lester, P. (2006). Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Human Resource Development Review, 5(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305285335

- McCreary, D. R., & Thompson, M. M. (2006). Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4)., 494–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.494

- MIND. (2019). Bluelight mental health info. Retreived 2021 March 3, from https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/working-in-the-emergency-services/.

- Näswall, K., Kuntz, J., Hodliffe, M., & Malinen, S. (2015). Employee Resilience Scale (EmpRes): Technical report. Resilient Organizations Research Report.

- Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., Bisconti, T. L., & Wallace, K. A. (2006). Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 730–749.

- Ong, A. D., Zautra, A., & Reid, M. C. (2010). Psychological resilience predicts decreases in pain catastrophizing through positive emotions. Psychology and Aging, 25(3), 516–523.

- Parul, M., & Pooja, G. (2020). Learning organization and work engagement: the mediating role of employee resilience. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(8), 1071–1094. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1396549

- Peccei, R., & Van De Voorde, K. (2019). Human resource management–well‐being–performance research revisited: Past, present, and future. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(4), 539–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12254

- Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., & Podsakoff, N. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform. A comparitive analysis: New Public Management, governance, and the Neo-Weberian State. Oxford University Press.

- Public Health England. (2015). Consensus Statement on Improving Health and Wellbeing between NHS England, Public Health England, Local Government Association Chief Fire Officers Association and Age UK. Retreived 2021 April 10, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/joint-consens-statmnt.pdf.

- Purba, A., & Demou, E. (2019). The relationship between organisational stressors and mental wellbeing within police officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1286)https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7609-0

- Purohit, K. (2020). The National Health Service’s ‘special measures’: Cambridge–A case study. Health Services Management Research, 2020, 1–15.

- Rodwell, J., Noblet, A. J., & Allisey, A. (2011). Improving employee outcomes in the public sector. Personnel Review, 40(3), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481111118676

- Schaufeli, W., Salanova, M., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measure of engagement and burnout: A two sample confiratory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

- Tehrani, N., & Hesketh, I. (2019). The role of psychological screening for emergency service responders. International Journal of Emergency Services, 8(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJES-04-2018-0021

- Tonkin, K., Malinen, S., Näswall, K., & Kuntz, J. C. (2018). Building employee resilience through wellbeing in organizations. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 29(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21306

- Turnbull, P., & Wass, V. (2015). Normalizing extreme work in the police service? Austerity and the inspecting ranks. Organization, 22(4), 512–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415572513

- Ulrich, D. (2016). HR at a Crossroads. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 54(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12104

- United Nations (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals Report https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2020.pdf

- Wankhade, P., McCann, L. & Murphy, P. (2019). (Eds.) Critical perspectives on the management and organization of emergency services. Routledge.

- Wankhade, P. (2021). A ‘journey of personal and professional emotions’—Emergency ambulance professionals during Covid-19. Public Money & Management (Management), 1–3. published online: 30 Nov 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.2003101

- Wankhade, P., & Patnaik, S. (2019). Collaboration and governance in the emergency services: Issues, opportunities and challenges. Palgrave Pivot.

- Wankhade, P., Stokes, P., Tarba, S., & Rodgers, P. (2020). Work intensification and ambidexterity – The notions of extreme and ‘Everyday’ experiences in emergency contexts: Surfacing dynamics in the ambulance service. Public Management Review, 22 (1), 48–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1642377

- Wilkinson, A., & Wood, G. (2017). Global trends and crises, comparative capitalism and HRM. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(18), 2503–2518. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1331624