Abstract

In this paper, we explore how institutional actors push or resist equality, diversity and inclusion in light of power relations in their respective country contexts. We conducted interviews with a range of institutional actors, including governmental organizations, employer representatives, unions, professional associations, and civil society organizations working on EDI issues in Germany and Turkey, two countries with very different socioeconomic and political settings. Our findings suggest that EDI fields are structured by country-specific power relations: they appear as competitively dispersed in Germany and politically polarized in Turkey, depending on the social position of the actors and the type of field fragmentation. These field characteristics, in turn, nurture different patterns of actors’ strategies such as framing and mobilizing aimed at maintaining or disrupting the institutionalized status quo of EDI. We propose that a critical, power-sensitive institutional work approach to EDI is a useful lens through which to examine extra-organizational country contexts in international HRM research and, in particular, context-sensitive studies of EDI. As a practical implication, EDI and HR managers will be sensitized to the relevance of building coalitions with external stakeholders if they are to advance EDI within their organizations.

Introduction

Countries vary significantly in how equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) is institutionalized, for example, in terms of their antidiscrimination laws or societal norms (Klarsfeld et al., Citation2022). This has important implications for the implementation of human resource management (HRM) and related diversity management practices (Peretz et al., Citation2015; Kemper et al., Citation2016) and, ultimately, workplace inequalities (Calás et al., Citation2009; Hyman et al., Citation2012; Tatli et al., Citation2012). Accounting for country contexts—for instance, along institutional (e.g. Kostova, Citation1999) or cultural specificities (e.g. House et al., Citation2004)—lies at the core of international HRM research and the study of the transfer and adaptation of HR practices (e.g. Bonache & Festing, Citation2020). Likewise, there is increasing research on the diffusion of EDI practices in work organizations, focusing on the institutional environment and the influence of regulatory, normative (i.e. cultural), and cognitive EDI institutions (e.g. Acar Erdur, Citation2022; Moore et al., Citation2017; Süß & Kleiner, Citation2007). However, an often neglected aspect of international HRM research and related context-sensitive management studies on EDI is the power-laden role that external actors play in shaping and contesting the institutional context focused on (Kornau et al., Citation2020; Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Seierstad et al., Citation2017).

Indeed, we know that in addition to employers, various institutional actors (e.g. governments, pressure groups, employers’ associations, and unions) are present and interact in the EDI field, but often with conflicting interests that must be negotiated (Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Schreiblmayr & Reichel, Citation2022; Stringfellow, Citation2020). Research in the U.K. health sector (Healy & Oikelome, Citation2007), and in the U.K. higher education sector (Tatli et al., Citation2015) shows that alliance building and negotiation with external stakeholders play an important role for diversity managers in promoting EDI in their organizations. While we know that extra-organizational actors are an important resource for EDI professionals (Tatli, Citation2011), we have very little knowledge about the strategies of these actors, their coalitions, and their struggles in a specific country context. Therefore, the research questions the paper aims to answer are: how can the country-specific EDI field be characterized based on the power relations among the actors involved? How do institutional actors push or resist progress toward EDI at work within the country-specific EDI field?

In answering these research questions, we follow others (e.g. Collien et al., Citation2016; Styhre, Citation2014) and take the concept of institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006) as a starting point, combined with a perspective on institutional fields as ‘political arenas where actors vie for the advantages provided by field positions’ (Furnari, Citation2018, p. 326). On this basis, we define institutional work in the field of EDI (EDI work for short) in this paper as political process in which multiple institutional actors seek to advance, contest or maintain the institutionalized status quo of EDI as reflected, for example, in antidiscrimination legislation. We thus adopt a critical perspective on EDI that is sensitive to politics and power, foregrounding the contested nature of the EDI field as a power-laden space of pluralistic interests (Jonsen et al., Citation2013; Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Tatli, Citation2011; Zanoni et al., Citation2010). For our study of country-specific EDI fields, we selected Germany and Turkey, two countries with very different socioeconomic and political environments. In each country, we sought to cover a broad range of key institutional actors and conducted a qualitative-explorative study based on interviews with representatives of government organizations, employers’ associations, trade unions, professional associations, and civil society organizations (CSOs) working on EDI issues.

This study has numerous theoretical contributions. First, by analyzing EDI fields in Germany and Turkey, we provide contextualized insights into EDI work, contributing to the theoretical maturity of comparative perspectives in field structures (Furnari, Citation2018) and the EDI field in particular (e.g. Calás et al., Citation2009; Klarsfeld et al., Citation2019; Tatli, Citation2011). Second, our study contributes to the growing body of studies on relational diversity management that go beyond the much-researched perspectives of employers and managers to include a broader range of institutional actors such as CSOs or unions (Ahonen et al., Citation2014; Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Zanoni and Janssens, 2021) and follows calls for a more explicit examination of the role of external stakeholders and the national contexts in which EDI and HR management are embedded (e.g. Farndale et al., Citation2015; Gooderham et al., Citation2019; Kornau et al., Citation2020; Pudelko et al., Citation2015). This allows for a more nuanced and holistic examination of the political nature of EDI and offers important practical implications for policymakers, EDI and HR managers. Finally, this study is one of the first to reap the benefits of applying the institutional work perspective to the institutional field of EDI. By looking at the power relations of actors involved in HR-related issues such as EDI, we contribute to a growing body of knowledge on power-sensitive applications of institutional work (Gidley & Palmer, Citation2021; Munir, Citation2015; Lawrence, Citation2008; Lewis et al., Citation2019; Lok, Citation2019).

The paper is organized as follows: First, we present the theoretical background of the paper by introducing the context-sensitive perspective on EDI and the concepts of institutional work, actors, and field. The methods section describes the context of the study, research design, data collection, and analysis. Then, we present the findings of our study in two main sections: first, the exploration of the institutional field of EDI and second, the strategies of institutional actors. Finally, we lay out the theoretical and practical implications and identify limitations and future research directions.

Theoretical background

Context-sensitive perspectives on EDI

Around the world, inequalities based on gender, race, and class, as well as other dimensions such as (dis)ability, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation, shape our societies and workplaces (Acker, Citation2006). In response, organizations, policymakers, and researchers are challenged to find ways to advance equality and its allied concepts of diversity and inclusion. While diversity captures the heterogeneity of groups or workforces along socially meaningful identity categories, inclusion refers to the involvement and integration of diversity and differences into organizational cultures, practices, and processes (Roberson, Citation2006; Nishii, Citation2013). In many countries, EDI is on the political and business agenda. However, a growing number of studies have shown that practices and discourses around EDI cannot be understood or interpreted uniformly across countries (e.g. Klarsfeld et al., Citation2019; Klarsfeld et al., Citation2022).

A helpful theoretical lens for explaining the context specificity of EDI is institutional theory. The core idea is that organizations face certain constraints in a particular regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutional environment and that they adapt to that environment and to each other to gain legitimacy, secure resources, and ensure their survival. While regulatory institutions include laws and policies within countries, cognitive institutions build on a society’s shared knowledge, categories, and discourse, and normative institutions refer to people’s norms and values (Kostova, Citation1999; Scott, Citation1995). In relation to EDI, relevant regulatory institutions include, for example, equal opportunity laws and quotas, as well as the lack thereof. An example of EDI-specific cognitive institutions is the prevailing political discourse on EDI issues, such as on gender or migration. Finally, examples of EDI-specific normative institutions are norms of acceptance or openness to difference. Neo-institutional theory suggests that these three institutional drivers simultaneously determine how organizations deal with EDI issues. Because these three drivers tend to vary more across countries than within a country, organizations within the same context adopt similar solutions, leading to isomorphism (i.e. homogeneous patterns of organizational responses to EDI issues).

Previously, scholars have investigated such patterns in relation to EDI issues, such as how diversity management practices disseminate within a country through isomorphism (Süß & Kleiner, Citation2007) or how disability inclusive HR practices are adopted in response to societal expectations (Moore et al., Citation2017). Some studies in this tradition take a comparative approach, contrasting institutions in different countries and examining how they influence organizational diversity management in each context (Klarsfeld et al., Citation2012; Klarsfeld, Citation2016; Peretz et al., Citation2015). For example, Kemper et al. (Citation2016) compare diversity management practices used by organizations in Germany and Japan and conclude that the scope and focus of these practices vary significantly due to institutional differences (e.g. tighter versus looser norms, more versus less homogeneous composition of the population). These studies are valuable for understanding how the institutional context shapes EDI practices in organizations and, in turn, how EDI practices vary across countries. Instead, few research efforts have focused on the actors involved in these processes and, in particular, how relevant actors proactively shape the institutional context in which they are embedded (Lewis et al., Citation2019). However, an actor-centered perspective is critical to understanding how institutional change occurs (Battilana et al., Citation2009). This is especially true in the academic EDI field, where researchers seek to understand why structural inequalities are so persistent in different countries and how social change comes about.

Multiple actors and their institutional work in the EDI field

To account for the interplay between structure and agency, we draw on the theoretical approach of institutional work, which captures individual or organizational actions aimed at creating, maintaining, or disrupting institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Lawrence et al., Citation2009). As such, this approach bridges and extends research on institutional entrepreneurship (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2009; Maguire et al., Citation2004), social movement theory (e.g. Rao et al., Citation2000), and deinstitutionalization (e.g. Oliver, Citation1991), combining them with insights from the sociology of practice (Bourdieu, Citation1977; Giddens, Citation1984). While scholars studying institutional entrepreneurship are interested in dramatic changes or the creation of new institutions and how these are brought about by powerful institutional entrepreneurs with sufficient resources, institutional work is also concerned with incremental and less visible efforts to change or preserve existing institutional arrangements (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Lawrence et al., Citation2009; Citation2011). This distinction raises important questions about how power is distributed in a field (Furnari, Citation2018) and how, for example, actors who have fewer resources due to the conditions of the institutional environment in which they are embedded are (un)able to invoke change (also referred to as the ‘paradox of embedded agency’; Battilana & D’Aunno, Citation2009, p. 36). Accordingly, the power relations in a field—understood here as the social position of actors (reflecting access to various resources) and the field structure (centralized versus fragmented)—shape the possibilities of actors and the degree of their agency (Battilana et al., Citation2009; Furnari, Citation2018). Thus, an institutional work perspective provides a useful lens for the purpose of this study, as it considers the power relations among relevant actors that structure a given country’s EDI field and influence actors’ strategies to advance or resist change toward workplace equality.

Previous management studies that have taken an actor-centered perspective to investigate institutional change related to EDI issues have mostly examined the strategies of individuals (e.g. diversity managers, HR managers, line managers, and/or employees) aimed at changing the status quo within organizations (e.g. Hunter & Swan, Citation2007; Kirton & Greene, Citation2010; Meyerson & Tompkins, Citation2007; Tatli et al., Citation2015). Some have used an institutional work perspective (e.g. Collien et al., Citation2016; Roos et al., Citation2020; Styhre, Citation2014). For example, in their case study, Collien et al. (Citation2016) develop the concept of ‘age work’ and show how age images and related organizational age inequalities are maintained and disrupted by multiple individual actors. Similarly, Doldor et al. (Citation2016) apply an institutional work perspective to show how headhunters are involved in micro-processes of change. This type of ‘diversity work’ may happen accidentally and be more marginal, in contrast to the dramatic changes or creation of new institutions brought about by institutional entrepreneurs (Doldor et al., Citation2016; Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Lawrence et al., Citation2009; Citation2011). Moreover, in their study of gender inequality in personnel selection, Blommaert and van den Brink (Citation2020) examine a combination of internal and external actors involved in selection processes to understand their multiple roles, associated strategies, and practices of collaboration among them. In this study, we build on the idea that understanding such complex dynamics among multiple actors is crucial. However, because we examine the country-specific characteristics of EDI fields, our focus is on institutional actors and their collective actions rather than individuals within single work organizations.

Within management research, few studies have scrutinized the role of institutional actors in EDI fields and the cooperative or competitive dynamics between them. Exceptions are studies in the industrial relations literature that have begun to expand their traditional focus on social dialog between employer associations and unions to include so-called new actors such as nongovernmental organizations (e.g. national identity networks) or consulting firms (e.g. Elomäki & Kantola, Citation2020; Healy & Oikelome, Citation2007; Kirton & Greene, Citation2010; Stringfellow, Citation2012, Citation2020). These studies show how institutional actors approach EDI issues, what discourses dominate, and why and how actors relate to each other. For example, they show how women’s organizations are marginalized at the EU level while unions and employers gain influence (Elomäki & Kantola, Citation2020), or the way unions are replaced and complemented by other actors such as pressure groups (Healy & Oikelome, Citation2007).

Another stream of literature that focuses on institutional actors is the literature on social movements (see McAdam et al., Citation1996). Social movements are described as ‘organized collective endeavors to solve social problems’ (Rao et al., Citation2000, p. 242), and related studies focus on how collective actors de-institutionalize existing rules, norms, and values on the one hand, and define new legitimate options on the other. In doing so, they pursue broader strategies to ‘identify political opportunity, frame issues and problems, and mobilize constituencies’ (Rao et al., Citation2000, p. 238). Typical examples include studies of the gay and lesbian movement (Engel, Citation2001) or the women’s movement (Taylor, Citation1989).

It is important to draw attention to this multiplicity of actors, their relationality, strategies, and power struggles in the EDI field, as this provides a more holistic picture of the complex reality of addressing social inequalities and goes beyond holding single corporate actors accountable for providing solutions (Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Jonsen et al., Citation2013). Building on these ideas and applying them to the EDI field, we conceptualize EDI work in this paper as a political process in which multiple institutional actors seek to advance, contest, or preserve the institutionalized status quo of EDI, taking into account the power dynamics among these actors.

Methods

The purpose of this interview study was to explore how institutional actors in Germany and Turkey (try to) push or resist EDI at work in light of power relations in their respective countries. Given the lack of research that takes a multi-actor perspective on EDI, and in order to capture the context-specific conditions relevant to EDI actors and their struggles, we adopted a qualitative-explorative approach. Following the call to make paradigmatic viewpoints explicit in qualitative research (Welch & Piekkari, Citation2017), we also situate our study as interpretive by exploring the socially constructed experiences of EDI actors in Germany and Turkey and therefore taking their subjective accounts as the starting point for our analysis. During data collection and analysis, we adhere to accepted principles of rigorous qualitative research such as transparency, deep engagement, and reflexivity to enhance the credibility of our findings (Bansal & Corley, Citation2011; Welch & Piekkari, Citation2017). Before delving deeper into data collection and analysis, we outline the context of our study.

Country context of the study

We chose Germany and Turkey for our study—two countries with very different socioeconomic and political contexts. The juxtaposition of these different contexts allowed us to highlight the main characteristics of the EDI field that nurture the EDI work strategies of institutional actors. The following section provides a basic description of the regulatory, cognitive, and normative EDI institutions in Germany and Turkey (see also Acar Erdur, Citation2022; Bruchhagen et al., Citation2010; Özbilgin et al., Citation2010; Ozgener, Citation2008; Sürgevil, Citation2010; Yamak et al., Citation2015) to familiarize the reader with the context under study.

The increasing institutionalization of EDI in Germany is reflected in various laws (e.g. Federal Constitutional Law, 1949 and General Equal Treatment Act, 2006) and related efforts to implement it in the workplace, supported by the Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency and other actors (Bruchhagen et al., Citation2010). In Turkey, women and other marginalized groups are protected from discrimination by the Turkish Constitution (1982), but the Turkish Constitution does not cover, for example, the protection of LGBT + individuals (Yılmaz & Göçmen, Citation2016). Enforcement of anti-discrimination laws in Turkey is limited, human rights activists are intimidated, and civil society and democratic institutions are increasingly undermined (European Commission, Citation2018; Küskü et al., Citation2021). In particular, following the failed coup attempt in 2016, freedom of expression, access to human, democratic, and labor rights, and the independence of the judiciary have been further and severely curtailed. Despite the dynamic debate and activism on EDI issues in both countries, the Turkish government marginalizes EDI actors and actively undermines progressive elements engaged in EDI work (Özbilgin et al., Citation2010; Öztürk & Özbilgin, Citation2014), while the German government arguably acts as a key partner in creating an enabling environment for the promotion of EDI in the country (Bruchhagen et al., Citation2010; Stringfellow, Citation2020).

Looking at cognitive EDI institutions, both countries show common categories and discourses that reinforce existing inequalities. For example, while Germany is the second most popular immigration country in the world (OECD, 2018) and migrants (e.g. from Turkey, Poland, and Syria) represent a strong economic potential for the German labor market, employment data and studies on the organizational inclusion of migrants and refugees show that this potential has not yet been fully realized (e.g. Al Ariss et al., Citation2013; Bruchhagen et al., Citation2010; Pesch & Ipek, Citation2017; Schmidt & Müller, Citation2013). A vivid example of the rhetoric surrounding this issue is the common use of the term ‘migration background’. Germans with at least one parent who did not receive German citizenship by birth are considered to have a migration background (Destatis, Citation2018). Thus, even second- and third-generation descendants with German passports are still considered migrants, underpinning the public view that being German is based on ethnicity and ancestry (Mahadevan & Kilian-Yasin, Citation2017). Similar, but even more problematic, are the increasingly racist and exclusionary discourses toward migrants in the German parliament, which has experienced a shift to the right due to the presence of right-wing populist parties such as the AfD (Süddeutsche Zeitung, Citation2021).

In Turkey, while the country remains a signatory to key international conventions (e.g. CEDAW, European Social Charter, relevant ILO conventions), high-level political discourse on EDI stands in stark contrast to the official state position as ratified internationally. Examples of government-led political discourse include conservative statements from the highest levels of the state, including the president, who stated that ‘women are not equal to men, our religion has defined a position for women: motherhood’ (The Guardian, Citation2014), although the government has expanded women’s rights in some areas, such as lifting the ban on wearing headscarves in schools, universities, and public offices.

Normative institutions are values and norms shared by people in a country (Kostova, Citation1999). Cultural values have often been used to structure and measure normative institutions (e.g. Björkman et al., Citation2008; Busenitz et al., Citation2000; Knappert et al., Citation2021; Nelson et al., Citation2017). Comparing the cultural values of Germany and Turkey, several differences relevant to EDI become apparent. For example, while Germany scores significantly higher than Turkey on individualism—the degree to which societies value individual rights and needs—Turkey ranks higher than Germany on power distance—the degree to which people accept privilege and power differences (Hofstede Insights, Citation2022; House et al., Citation2004; Peretz et al., Citation2015). In addition, the Global Tolerance Index (Zanakis et al., Citation2016) shows significant differences, with Germany ranking 5th and Turkey ranking 37th out of 56. The index summarizes a country’s ‘recognition and acceptance of differences, willingness to grant equal rights, and refraining from openly intolerant attitudes’ (Zanakis et al., Citation2016, p. 480). Accordingly, both countries struggle to find common ground on values such as human rights and equal opportunities and repeatedly bring these topics to the agenda of their leaders’ joint meetings (Pancevski, Citation2018).

Data collection

In total, 17 semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with institutional actors from Germany (9 interviews) and Turkey (8 interviews). Interview partners were selected based on two criteria: First, we wanted to cover a broad range of perspectives from organizations that are important actors in their respective national EDI fields. Second, we intended to match similar organizations in Germany and Turkey to understand how views varied across and along different types of organization.

In Germany and Turkey, similar types of actors are part of the country-specific EDI field, including the government, employers, professional associations, trade unions, and CSOs (Bruchhagen et al., Citation2010; Özbilgin et al., Citation2010), and were therefore considered in this study. Two important groups of actors are trade unions (4 interviews) and employer representatives (2 interviews), as they represent the interests of employees and employers, respectively, and act on their behalf (e.g. Müller-Jentsch, Citation2004). In addition, to go beyond the much-studied employer perspective and to account for the multi-actor nature of EDI (Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Schreiblmayr & Reichel, Citation2022), we also included specific CSOs that advocate for the value of diversity in society as well as for human rights and/or interests of specific minority groups (5 interviews). Furthermore, professional associations (3 interviews) play a role in the EDI field through activities such as lobbying or consulting on diversity issues. Finally, legislative bodies establish the relevant regulations, with government organizations acting as their implementing agencies (3 interviews). To protect the anonymity of our interviewees, the names of the organizations must remain confidential.

Interviews were conducted face-to-face and lasted an average of 1.7 hours. We chose semi-structured interviews because they allow for some structure and comparability across actors and countries, while allowing for in-depth conversations and flexibility in the course of the interviews. We developed an interview guideline to explore EDI work as a relational phenomenon. It included questions about the interviewee’s personal background, the organization’s role in promoting EDI within and beyond its own organizational boundaries, related interactions with other actors, and perceptions of the country’s institutional and political context (see full interview guideline in the Appendix). Face-to-face interviews allowed us to clarify the meaning of questions and answers on the spot, thus avoiding misunderstandings. Following methodological contextualization (Welch & Piekkari, Citation2014; Welch & Piekkari, Citation2017), we relied on the help of a native Turkish-speaking research assistant to recruit interviewees in Turkey. This approach helped to gain trust and reduce potential interview participants’ uncertainties about the research process and its purpose.

Data analysis

We recorded all interviews, transcribed them, and imported them into NVivo. Following Gioia and colleagues (Gioia et al., Citation2013), we began the analysis by inductively formulating codes that were closely aligned with our interviewees’ perspectives and formulations; that is, our goal was to capture our interviewees’ experiences as authentically as possible. In doing so, we engaged in a process of open coding (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) regarding barriers and resources to EDI work, the ways in which actors deal with problems, how they relate to and perceive each other, etc. This resulted in an extensive code list of 308 first-order codes for both countries.

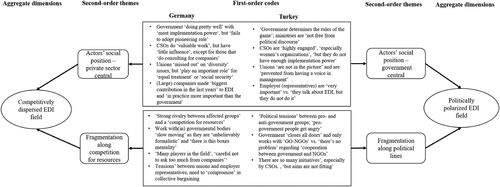

In a next step, we reduced this large number of categories by performing axial coding, i.e. noting similarities and differences between codes, across countries and actors, and began to group codes accordingly. Throughout this process, we delved further into the interview material and relevant literature on institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006; Lawrence et al., Citation2009), social movement theory (e.g. Rao et al., Citation2000), institutional change (e.g. Furnari, Citation2018) and institutional entrepreneurship (e.g. Battilana et al., Citation2009). This iterative process between theory and data helped us understand the deeper structure of this collection of themes and possible relationships. As a result, we found that the country-specific EDI fields in Germany and Turkey differ fundamentally along two theoretically underpinned second-order themes, namely the actors’ social position in the field and the specific types of field fragmentation. Together, these two themes characterize country-specific EDI fields in terms of actors’ power relations.

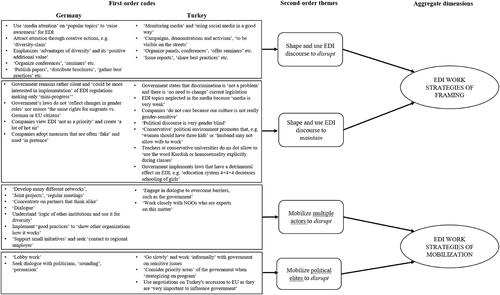

To structure and visualize these contextual differences, we created a comparative data structure ( and ). In the middle of , we arranged the first-order codes for both countries separately to account for the country-specific content and wording of interviewees. We then used the data structure () to illustrate the country specificity of the two second-order themes: (i) actors’ social position in relation to the central actors of the field and (ii) the fragmentation of the field that runs along the competition for resources or political lines, respectively. As aggregate dimensions, we derived a characterization of the EDI fields as competitively dispersed and politically polarized.

Furthermore, we searched the data for actors’ attempts to push or resist EDI within these contextual conditions. Based on our conceptualization of EDI work, we identified several strategies, which we divided into strategies of framing (used to either maintain or disrupt the status quo) and mobilization (aimed at disrupting the status quo) (see ).

Results

The presentation of our results follows our data structure. First, we present our findings on the EDI fields in Germany Turkey, which we conceive of as competitively dispersed and politically polarized, respectively (see ). In a second step, we zoom in on the EDI work strategies of framing and mobilization (see ) and show how the actions of institutional actors are shaped by the country-specific EDI fields in which they are embedded.

Country-specific EDI fields: politically polarized or competitively dispersed

We found two second-order themes that characterize the country-specific EDI fields. The first theme summarizes our findings about institutional actors’ social position, i.e. actors’ ‘legitimacy in the eyes of, and the ability to bridge, diverse stakeholders, thereby enabling them to access dispersed sets of resources’ (Battilana et al., Citation2009, p. 77). For the second theme, type of field fragmentation, we synthesized interviewees’ responses about existing tensions, struggles, or obstacles when working with other actors. In line with , we present below our findings on these two themes and highlight commonalities and differences between the EDI fields in Germany and Turkey.

Actors’ social position

In both countries, the government plays a critical role in that it largely determines the focus and nature of legislative action affecting EDI, thus controlling the space in which other actors can (not) contribute to disrupting the status quo. However, the extent to which the government limits other actors’ room for maneuver varies by country context. For example, one German interviewee described how the various actors

‘(…) do not move in a vacuum, they have a framework within which they can move. And this is—yes—set by laws, so by the government and everything that has to do with legislation’. (employer representative 1, Germany)

Contrasting this with the view on the Turkish government, it becomes evident that the Turkish authorities were perceived as much more dominant and restrictive:

‘The government determines the rules of the game, whether we like it or not. (…) Unfortunately, the government always wins. No matter what we ask for, the government ends up with what it wants’. (union 1, Turkey)

In contrast, interviewees in Turkey largely agreed that private companies and employer associations play a minor role in EDI work, despite the interest of large and/or multinational corporations in EDI matters:

‘I can say that multinational companies are interested regardless of their size. Large companies are also interested because they are competing with international companies. They want to attract people, as multinationals do (…). [But] 80% are small companies, so I do not think it’s on their agenda’. (professional association 1, Turkey)

Type of field fragmentation

In Germany, there are a large number of organizations working for equality for ‘their’ specific target group. As a result, many actors are vying for a legitimate role in the highly contested EDI field, competing for attention and resources. This kind of rivalry can even be found within governmental institutions, where bureaucratic hurdles combined with a certain ‘boxes mentality’ (governmental organization 2, Germany) prevent different actors from bundling their efforts and working together, especially on issues of intersectionality of diversity dimensions, as one of our interviewees explains:

‘in the whole governmental sphere, single [diversity] characteristics are negotiated separately (…) because people have their own farm, cultivate it and don’t let others in’ (governmental organization 1, Germany).

‘You know they are GO-NGOs [governmental non-governmental organizations], they are close to the government, they have the same ideology and the government prefers NGOs that are close to their ideology’ (CSO 1, Turkey).

When the social position of actors and the type of fragmentation of the field are considered together and these characteristics are compared in Germany and Turkey, it becomes clear that the EDI field in both countries is fragmented into different groups. However, the type of fragmentation along lines of conflicting interests and the social position of these actors are very different in the two countries. In Turkey, actors’ social position is largely determined by their relationship with the government. Due to its strong formal authority, the Turkish government restricts the selection of its cooperation partners to those actors that are in line with its political agenda and goals in EDI. As a result, actors close to the political elites also have a more advantageous social position to push through changes that are in line with their interests. This social positioning of actors leads to a certain type of fragmentation of the field, characterized by two opposing groups of actors, those who support government policies and those who oppose them. This political polarization is based on fundamentally different value systems and a binary of progressive and conservative EDI approaches. Organizations that are on the progressive side are increasingly marginalized and struggle on the periphery of the field. For this reason, we refer to the country-specific EDI field in Turkey as ‘politically polarized’.

In Germany, the social position of the various actors and the patterns of fragmentation associated with them are less obvious. Governmental bodies are sometimes seen as challengers themselves, that work on par with non-governmental actors in the sense that they must negotiate institutional change in similar ways. Furthermore, actors generally agree upon the common vision that EDI at work is a desirable goal. However, they differ significantly in their approaches to how best to achieve this goal (e.g. binding laws vs. voluntary agreements) and what the main effort should be (e.g. which dimension of diversity to focus on). On this basis, actors are less concerned with political standpoints, but more concerned with gaining an advantageous position and access to resources to enforce their specific approach. Therefore, organizations with extensive resources such as large private sector companies are perceived as ‘dominants’ around which other actors in the EDI arena revolve in order to gain access to (financial) resources and successfully implement change. The private sector thus plays an important gate keeping role when it comes to prioritizing EDI issues, for example. However, the perceived consensus among actors and their dependence on resource-rich actors can cause economically less ‘useful’ EDI issues to disappear from view. For this reason, we describe the country-specific EDI field in Germany as ‘competitively-dispersed’.

EDI work strategies of framing

The strategies described by our interview participants seemed to be broadly consistent with the categories of ‘strategic action’, for example, in reference to issues of framing (Battilana et al., Citation2009; McAdam et al., Citation1996; Rao et al., Citation2000). Framing is about creating a common understanding of a problem by communicating a vision and shaping a discourse (Rao et al., Citation2000). In what follows, we build on this idea as we present our findings on EDI work strategies aimed at disrupting or maintaining the institutionalized status quo of EDI.

Shape and use EDI discourse to disrupt

All actors in both countries (with the exception of the Turkish government) are taking steps to frame EDI positively and to spread the values associated with it, e.g. through publications, organizing conferences, or using various media channels. In Germany, a common theme among all actors is the strategic use of media and media attention to specific issues or dimensions of diversity. For example, one interviewee stated that

‘(…) the extent to which we address these different groups always depends a bit on current topics. (…) In terms of gender, it was of course the debate about the gender quota that made the topic present (…). You need such a hook (…) then you can try to get a foot in the media coverage and build on that to try to inform people further. Or now the topic of refugees is current, now we publish a brochure on this topic, simply because there is a need’. (CSO 1, Germany)

Finding a ‘hook’ to which they can attach their ideas and then emphasize, for example, the positive outcomes of diversity seems to be a common strategy to shape the thinking of people. A pitfall of this approach is that disproportionate attention and resources are given to the more popular EDI issues and dimensions.

Moreover, such activities tend to lead to incremental changes rather than drastic societal upheavals. In Germany, most actions tend to be diplomatic and marginal, while in Turkey, the picture is mixed. Given the polarized nature of the field, actors who oppose the government seek to disrupt and challenge the system at a more fundamental level and, for example, do not attempt to place topics in mainstream media such as newspapers because ‘freedom of expression is violated’ (CSO 2, Turkey). Instead, they engage in more drastic activism and seek to shape public consciousness through visible actions in the streets.

‘2015 is the first year that we as an organization joined the public demonstrations for 1st of May, Labour Day. We became visible as we walked with the workers, defending their rights’. (CSO 1, Turkey)

This shows how in a politically polarized field like Turkey EDI work is narrowed down to basic demands for progress such as freedom of expression, access to justice and fairness, and fighting direct discrimination. At the same time, the state suppression of a more progressive EDI discourse in Turkey actually acts as a powerful force for grassroots and CSOs to find alternative forms of mobilization—showing a vibrant dynamism of the EDI field.

Shape and use EDI discourse to maintain

We identified various ways in which actors try to counteract the efforts described above and instead seek to maintain the status quo. While some interviewees suggested that the German government is engaged in many EDI issues (e.g. implementation of women’s quota in supervisory boards), especially the unions pointed to the government’s silence and lack of proactivity, reflected in ‘half-hearted laws’ (union 3, Germany) on gender equality or ‘mini-progress’ (union 1, Germany) for people with disabilities. Furthermore, some interviewees mentioned very specific laws such as EhegattensplittingFootnote1 (professional association 2, Germany) that do not adequately reflect the principle of EDI and through which the CDU-led government creates incentives to maintain a traditional, more conservative discourse and lifestyle. Aside from the government playing a role in maintaining the institutional EDI environment in its current form, private sector companies were criticized for not prioritizing EDI issues, even though they hold a leading social position in the field and have the power to enforce potentially far-reaching changes. Instead, interviewees from unions suggested that companies are strategically taking ‘fake’ (union 2, Germany) EDI measures and communicating them as success stories to meet the expectations of external stakeholders. In this way, they use the discourse around EDI to create a façade of legitimacy (Süß & Kleiner, Citation2007) that protects them from criticism and activists demanding real social change.

On the Turkish side, we found that the Turkish government, much like private sector companies in Germany, used this strategy of building a façade of legitimacy: Turkish actors were not concerned per se about a lack of laws to improve EDI legislation, but about insufficient enforcement of existing regulations, including the implementation of already ratified international conventions (e.g. CEDAW) as well as national laws. However, the Turkish government could use the existing regulations to ‘show off’ (CSO 3, Turkey), while the gap between official practices and their actual implementation in the workplace remains. However, unlike in the German context, where there is (at least officially) a consensus among all actors that discrimination is a problem that needs to be addressed, the Turkish government also uses more extreme framing strategies to maintain the status quo, namely to neglect the existence of discrimination altogether. For example, the government official we interviewed stated that discrimination of any kind is ‘not a problem’ in Turkey. At the same time, certain EDI issues, especially those related to LGBTI persons and the Kurdish minority, are taboo in public discourse.

In summary, EDI work strategies of framing aimed at maintaining the status quo are mostly adopted by the field dominants in both countries. In a competitively dispersed field like Germany, resistance to change by the private sector and parts of the government can best be summarized as a lack of interest in EDI issues, a general neglect of its importance, and related window dressing. In a politically polarized field like Turkey, the government is more proactive in this kind of ‘maintenance work’—even to the extent that progress already achieved, e.g. on gender equality, is counteracted by regressive, conservative political discourse and legislative changes.

EDI work strategies of mobilization

Next to framing issues, we found EDI work strategies in our interview material that are consistent with theorizing on strategic action of mobilization and political opportunity creation (Battilana et al., Citation2009; McAdam et al., Citation1996; Rao et al., Citation2000). More specifically, mobilizing constituents describes formal and informal modes of finding collaborators and engage in collective activities, while political opportunity means that actors ‘minimize or escape state repression, possess access to the political system, and have allies in elite groups’ (Rao et al., Citation2000, p. 242). Accordingly, we found that some mobilization strategies target multiple actors for collaborative action, while others focus on mobilizing political elites to disrupt the status quo.

Mobilize multiple actors to disrupt

To mobilize actors for collaborative actions, interviewees in Germany emphasized the importance of seeking dialog and initiating joint projects. These acts of collaboration were described as rather smooth, as there is generally a perceived consensus among actors on the importance of equality and diversity at work—despite sometimes differing opinions on how to achieve this goal or which topics are most relevant. Such cooperations with multiple actors are particularly important for CSOs that lack financial resources, as they can compensate for this by having a well-established network with representatives from the private sector, trade unions, academia or other institutions that support them, e.g. by giving speeches or providing premises for events.

In contrast, the mobilization of multiple actors in the Turkish context appears to be more complex given the importance of politics and the underlying ideology with which organizations identify. For example, one interviewee from a CSO emphasized that some unions, such as the left-leaning KESK (Confederation of Public Employees’ Unions), are very proactive and work very closely with them, while ‘conservative unions do not care about gender issues’ (CSO 2, Turkey). Another interviewee states that there is an urgent need to reach out to different partners to ‘overcome obstacles, like the government’ (CSO 1, Turkey).

In summary, in a competitively dispersed field like Germany, the main effort is to reach out to diverse actors in order to bridge divergent approaches and interests and build consensus and synergies for a shared vision of more diverse and equal workplaces. This is done through dialog, creating joint projects, and building a support network to compensate for a lack of (financial) resources. In contrast, the Turkish EDI actors we interviewed were comparatively less occupied with building relationships with diverse stakeholders. This is partly because actors in politically polarized field are ideologically divided and lack a common vision, which in turn makes collaboration more complex and sometimes undesirable.

Mobilize political elites to disrupt

While it is quite common in Germany to lobby and, for example, invite political decision-makers to networking events, our interview partners were more concerned with the results of this strategy than with the process itself. Frequently cited examples of relevant outcomes in Germany were the AGG (General Equal Treatment Act, 2006) and the 2015 gender quota in boardrooms:

‘This is of course a very, very slow process (…) many years of lobbying by women’s organizations (…) So, and now we finally have the quota—to a large extent—right? (…) this is how it works. The civil society organizations and other organizations have to be a strong lobby toward the politicians, until maybe at some point the politicians say (…) we are doing something binding’. (governmental organization 2, Germany)

‘We are not outside the general system, we cannot play an independent role in ensuring equality. We are just a small part of the government and if they say the legislation is fine, it is fine. We do not have a different opinion’. (governmental organization 1, Turkey)

Discussion

In this paper, we have addressed the question of how institutional actors in Germany and Turkey engage in EDI work, paying particular attention to the power relations between actors structuring the EDI field and the strategies of actors in the two countries. Previous research examining EDI from an institutional work perspective has focused on individual change agents (e.g. Doldor et al., Citation2016) and/or multiple organizational actors, including employees (e.g. Collien et al., Citation2016). While these contributions are important because they help to understand the complex processes of maintaining and disrupting institutionalized social inequalities, in this study we broaden this perspective and put a spotlight on the role of external, institutional actors. Such a relational perspective on diversity management (Ahonen et al., Citation2014; Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Syed & Özbilgin, Citation2009) helps create a more holistic and realistic perspective on the limits and possibilities of implementing social change for people inside and outside single work organizations. In the following section, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of these findings and outline the study’s limitations and future research avenues.

Theoretical implications

Our findings resonate with previous research emphasizing the contested nature of the EDI field as a power-laden space of pluralistic interests and high complexity with multi-faceted problems to be solved (Collien et al., Citation2016; Jonsen et al., Citation2013, Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011, Tatli, Citation2011). Building on institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006) and related comparative research on institutional fields (e.g. Furnari, Citation2018), we contribute to the EDI literature by adding an empirically grounded, context-sensitive, and actor-centered analysis. In doing so, we move beyond the more static focus on regulatory, normative, and cognitive institutions and their effects on EDI practices (e.g. Süß & Kleiner, Citation2007). Instead, we systematize and compare country-specific EDI fields in light of existing power relations—conceptualized in terms of the actors’ social position in the field and the type of field fragmentation.

Previous studies of institutional change have tended to focus on the degree of fragmentation (e.g. Furnari, Citation2018). In this sense, the EDI fields in Germany and Turkey could be understood as more centralized when it comes to dominant actors ‘around whose actions and interests the field tends to revolve’ (McAdam & Scott, Citation2005, p. 17) and who have superior (financial and social) resources (Greenwood & Suddaby, Citation2006) (i.e. large private sector companies in Germany and the government in Turkey). However, our findings suggest that both fields are not simply ‘populated by a coalition, but by fragmented groups’ (Battilana et al., Citation2009, p. 85): in the case of Turkey, we see the extreme case of two opposing coalitions based on political ideology. In Germany, we observe a dispersed field populated by numerous coalitions struggling to obtain resources. Thus, this study also extends previous research on institutional field structures by paying particular attention not only to the degree but also to the type of fragmentation—showing that EDI fields can be structured along political and economic struggles in a given country context. With the resulting differentiation in competitively dispersed vs. politically polarized EDI fields and the underlying concepts, we provide means to analyze the power relations of actors in a field as an important contextual dimension of EDI and HR management. In this sense, we follow the call to go beyond simply describing or accounting for country contexts when examining global perspectives of EDI, but instead expand theorizing on them (Farndale et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, we zoom in on the different strategies institutional actors use and show how they are shaped by power relations within these country-specific EDI fields. For example, in Germany, actors’ mobilization efforts tend to be directed at the multiplicity of stakeholders in order to gain access to a diverse set of resources and build collaborations, while in Turkey—given the complexity of creating a common vision among multiple parties in a politically polarized field—efforts tend to be directed at mobilizing political elites at the informal level. However, we also found that dominant actors in both countries employ similar strategies, such as aiming to maintain the status quo by creating a façade of legitimacy. Such a comparative approach helps to show how institutional work adapts to the power structure of the broader society, while there are also similarities in the strategies of EDI work in both countries, especially among actors with comparable social positioning. By applying the concept of institutional work to the highly contested EDI field, we enable a more critical and power-sensitive understanding of institutional work as political action.

Practical implications

The societal context and multiple stakeholders shape HRM policy and practice in complex ways and should be taken into account by HRM practitioners (Beer et al., Citation1984). In this sense, Tatli et al. (Citation2017) suggest endogenizing the social context as an integral dimension of HRM. Similarly, an important implication of our research for HR practitioners, including those with specific EDI responsibilities, is the need to recognize external, institutional actors and context as intrinsic determinants of the success and effectiveness of organizational policy and practice. Understanding the dynamics of EDI work within a country’s EDI field, may change how organizations and policymakers work toward and push for EDI initiatives. More specifically, our paper underscores the importance for EDI and HR managers to build and mobilize coalitions with institutional EDI actors, if they are to advance EDI in their organizations and reap the potential benefits of increased employee retention, creativity, performance, and talent utilization.

Considering the external context and external actors is particularly relevant for international HRM (Gooderham et al., Citation2019) and the international transfer of EDI policies and practices, which is a complex and challenging process (Lauring, Citation2013; Syed & Özbilgin, Citation2009). For MNCs it is not only critical to consider the institutional EDI environment in which they operate, but also to develop the political sensitivity and an understanding of the multitude of actors involved in EDI work in each national context. For example, it would be important to identify the dominant actors in the field and understand how they relate to other actors. In this way, HR managers could clarify who they work with, how they frame issues, and avoid pitfalls during cross-national transfer of their EDI policies. Similarly, professionals in governmental organizations, unions, professional associations or CSOs can legitimize their EDI work and make it more effective by engaging with HRM professionals.

Limitations and future research

We took a qualitative, interpretive, and critical approach to explore the experiences and perspectives of different institutional actors in Germany and Turkey to gain insights into their unique political struggles over EDI. While we do not claim generalizability of our findings, we argue, in line with Gioia et al. (Citation2013), that the more abstract concepts and dynamics outlined in our results may be transferable to structurally equivalent contexts and/or topics. Therefore, country-specific EDI field characteristics and strategies can direct future research to further refine and contextualize concepts and deepen our theoretical understanding of EDI work. For example, researchers may find the identified field characteristics useful in designing studies aimed at developing typologies of EDI contexts and actors’ strategies across multiple countries. Further studies in other countries are needed to further decipher the impact of EDI field characteristics on EDI work strategies. While we have focused on the EDI work of institutional actors in this study, we suggest that further studies could broaden this view to analyze their interaction with corporate actors, particularly EDI and HR managers in an international context. Longitudinal studies could then examine how these EDI field dynamics affect EDI and HR practices, improving our understanding of the underlying processes and outcomes of EDI work within organizations.

Moreover, our critical study can inspire cross-cultural management research of a more functionalist kind. The latter focuses on cultural values and their influence on EDI in organizations that might be related to the field characteristics and EDI work we analyze in this study. For example, the prominent role of competition and financial resources that we find in the German EDI field might resonate with the comparatively higher value of individualism in this country (Hofstede Insights, Citation2022; House et al., Citation2004). A better understanding of these relationships can help bridge different paradigmatic viewpoints and, for example, encourage future research in cross-cultural management to reflect on the role of institutional actors in (re)producing and shaping cultural values. As others have pointed out, a core tenet of critical cross-cultural management studies is to approach the concept of culture ‘with attention to political and economic institutions, structures and processes, discourses and ideologies’ (Romani et al., Citation2020, p. 51).

Finally, given the particular challenges of context-sensitive inquiry, it is especially important for the research team to reflect on the impact of their personal histories and experiences on the research process, i.e. to practice reflexivity (Easterby-Smith & Malina, Citation1999). Specific actions included taking field notes and using these notes to reflect within the research team on the content of the interviews, their own biases, and related interpretations. As researchers originally from Germany or Turkey and working across Europe, we felt confident that as a team we had the insider perspective necessary to interpret our data. Moreover, in the first step of data analysis, we adhered closely to the interviewees’ wording, ensuring that their actual voices were reflected without imposing our own interpretations on them. Nevertheless, there were some difficulties typical of research in different country contexts, as all interviews were conducted by the first author of this article, who identifies as German. Future research could benefit from having a diverse research team at all stages of the research process.

Conclusion

While EDI is on the corporate and political agenda in countries across the world, the implementation of EDI practices in organizations varies due to country-specific institutional differences. This study zooms in on the level of institutional actors to better understand their actions, the power relations between them, and how they shape the institutional context in which they operate. This underscores the importance of embedding EDI analyzes in their specific context and fleshing out the political nature of EDI work (Özbilgin & Tatli, Citation2011; Zanoni et al., Citation2010). More specifically, we provide insights into the country-specific characteristics of EDI fields, which may be competitively dispersed (e.g. in Germany) or politically polarized (e.g. in Turkey), depending on actors’ social positions and the type of field fragmentation. These field characteristics, in turn, nurture different patterns of actors’ EDI work strategies, such as framing and mobilizing, aimed at maintaining or disrupting the institutionalized status quo of EDI. Therewith, our study contributes an innovative approach to better understand the (inter)national context in which HR and EDI practitioners operate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Notes

1 Tax system in which husband and wife each pay income tax on half of their combined incomes.

References

- Acar Erdur, D. (2022). Diversity and equality in Turkey: An institutional perspective. In Klarsfeld A., Knappert L, Kornau A, Ng E and Ngunjiri F (Eds.), Research handbook on new frontiers of equality and diversity at work. International perspectives (pp. 235–254). Edward Elgar.

- Acker, J. (2006). Inequality regimes: Gender, class and race in organizations. Gender & Society, 20(4), 441–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243206289499

- Ahonen, P., Tienari, J., Meriläinen, S., & Pullen, A. (2014). Hidden contexts and invisible power relations: A Foucauldian reading of diversity research. Human Relations, 67(3), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713491772

- Al Ariss, A., Vassilopoulou, J., Özbilgin, M. F., & Game, A. (2013). Understanding career experiences of skilled minority ethnic workers in France and Germany. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(6), 1236–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.709190

- Bansal, P. T., & Corley, K. (2011). The coming of age for qualitative research: Embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60262792

- Battilana, J., & D’Aunno, T. (2009). Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. In Lawrence T B, Suddaby R and Leca B (Eds.), Institutional work. Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (pp. 31–58). Cambridge University Press.

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Beer, M., Spector, B., Lawrence, P. R., Quinn, M., & Walton, R. E. (1984). Management human assets. The groundbreaking Harvard business school program. The Free Press.

- Björkman, I., Smale, A., Sumelius, J., Suutari, V., & Lu, Y. (2008). Changes in institutional context and MNC operations in China: Subsidiary HRM practices in 1996 versus 2006. International Business Review, 17(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2008.02.001

- Blommaert, L., & van den Brink, M. (2020). Gender equality in appointments of board members: The role of multiple actors and their dynamics. European Management Review, 17(3), 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12381

- Bonache, J., & Festing, M. (2020). Research paradigms in international human resource management: An epistemological systematisation of the field. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 34(2), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002220909780

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Bruchhagen, V., Grieger, J., Koall, I., Meuser, M., Ortlieb, R., & Sieben, B. (2010). Social inequality, diversity, and equal treatment at work: The German case. In Klarsfeld A (Eds.), International handbook on diversity management at work (pp. 109–138). Elgar.

- Busenitz, L. W., Gomez, C., & Spencer, J. W. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 994–1003. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556423

- Calás, M. B., Holgersson, C., & Smircich, L. (2009). ‘Diversity Management’? Translation? Travel? Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(4), 349–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2009.09.006

- Collien, I., Sieben, B., & Müller-Camen, M. (2016). Age work in organizations: Maintaining and disrupting institutionalized understandings of higher age. British Journal of Management, 27(4), 778–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12198

- Destatis. (2018). State & society – Migration & integration. https://www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/SocietyState/Population/MigrationIntegration/MigrationIntegration.html

- Doldor, E., Sealy, R., & Vinnicombe, S. (2016). Accidental activists: Headhunters as marginal diversity actors in institutional change towards more women on boards. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12107

- Easterby-Smith, M., & Malina, D. (1999). Cross-cultural collaborative research: Toward reflexivity. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/256875

- Elomäki, A., & Kantola, J. (2020). European social partners as gender quality actors in EU. Social and economic governance. Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(4), 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13018

- Engel, S. M. (2001). The unfinished revolution: Social movement theory and the gay and lesbian movement. Cambridge University Press.

- European Commission. (2018). Turkey 2018 report. Strasbourg: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20180417-turkey-report.pdf

- Farndale, E., Biron, M., Briscoe, D., & Raghuram, S. (2015). A global perspective on diversity and inclusion in work organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(6), 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.991511

- Furnari, S. (2018). When does an issue trigger change in a field? A comparative approach to issue frames, field structures and types of field change. Human Relations, 71(3), 321–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717726861

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of a theory of structuration. Polity Press.

- Gidley, D., & Palmer, M. (2021). Institutional work: A review and framework based on semantic and thematic analysis. M@n@gement, 24(4), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.37725/mgmt.v24.4579

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gooderham, P. N., Mayrhofer, W., & Brewster, C. (2019). A framework for comparative institutional research on HRM. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1521462

- Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785498

- Healy, G., & Oikelome, F. (2007). Equality and diversity actors: A challenge to traditional industrial relations? Equal Opportunities International, 26(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150710726525

- Hofstede Insights. (2022). Country comparison Germany and Turkey. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/germany,turkey/

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, readership and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. SAGE.

- Hunter, S., & Swan, E. (2007). Oscillating politics and shifting agencies: Equalities and diversity work and actor network theory. Equal Opportunities International, 26(5), 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150710756621

- Hyman, R., Klarsfeld, A., Ng, E., & Haq, R. (2012). Introduction: Social regulation of diversity and equality. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 18(4), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680112461575

- Jonsen, K., Tatli, A., Özbilgin, M. F., & Bell, M. P. (2013). The tragedy of the uncommons: Reframing workforce diversity. Human Relations, 66(2), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712466575

- Kemper, L. E., Bader, A. K., & Froese, F. J. (2016). Diversity management in ageing societies: A comparative study of Germany and Japan. Management Revu, 27(1–2), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2016-1-2-29

- Kirton, G., & Greene, A. M. (2010). What does diversity management mean for the gender equality project in the United Kingdom? Views and experiences of organizational actors. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L’Administration, 27(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.168

- Klarsfeld, A., Ng, E., & Tatli, A. (2012). Social regulation and diversity management: A comparative study of France, Canada and the UK. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 18(4), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680112461091

- Klarsfeld A. (Eds.). (2016). Research handbook of international and comparative perspectives on diversity management. Edward Elgar.

- Klarsfeld, A., Knappert, L., Kornau, A., Ngunji, F., & Sieben, B. (2019). Diversity in under-researched countries: New empirical fields challenging old theories? Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 38(7), 694–704. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-03-2019-0110

- Klarsfeld A., Knappert L., Kornau A., Ng E. and Ngunjiri F. (Eds.). (2022). Research handbook on new frontiers of equality and diversity at work. International perspectives. Edward Elgar.

- Knappert, L., Peretz, H., Aycan, Z., & Budhwar, P. (2021). Staffing effectiveness across countries: An institutional perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12411

- Kornau, A., Frerichs, I. M., & Sieben, B. (2020). An empirical analysis of research paradigms within international human resource management: The need for more diversity. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 34(2), 148–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002220908035

- Kostova, T. (1999). Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.2307/259084

- Küskü, F., Aracı, Ö., & Özbilgin, M. F. (2021). What happens to diversity at work in the context of a toxic triangle? Accounting for the gap between discourses and practices of diversity management. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(2), 553–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12324

- Lauring, J. (2013). International diversity management: Global ideals and local responses. British Journal of Management, 24(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00798.x

- Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and institutional work. In Clegg SR, Hardy C, Lawrence TB and Nord WR (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies (2nd ed, pp. 215–254). SAGE.

- Lawrence, T. B. (2008). Power, institutions, and organizations. In Greenwood R, Oliver C, Sahlin K and Suddaby R (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 170–197). SAGE.

- Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2009). Introduction: Theorizing and studying institutional work. In Lawrence TB, Suddaby R and Leca B (Eds.), Institutional work. Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (pp. 1–27). Cambridge University Press.

- Lawrence, T. B., Suddaby, R., & Leca, B. (2011). Institutional work: Refocusing institutional studies of organization. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492610387222

- Lewis, A. C., Huang, L. S. R., & Cardy, R. L. (2019). Institutional theory and HRM: A new look. Human Resource Management Review, 29(3), 316–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.07.006

- Lok, J. (2019). Why (and how) institutional theory can be critical: Addressing the challenge to institutional theory’s critical turn. Journal of Management Inquiry, 28(3), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617732832

- Maguire, S., Hardy, C., & Lawrence, T. B. (2004). Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 657–697. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159610

- Mahadevan, J., & Kilian-Yasin, K. (2017). Dominant discourse, orientalism and the need for reflexive HRM: Skilled Muslim migrants in the German context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(8), 1140–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1166786

- McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge University Press.

- McAdam, D., & Scott, W. R. (2005). Organizations and movements. In Davis GF, McAdam D, Scott WR and Zald MW (Eds.), Social movements and organization theory (pp. 4–40). Cambridge University Press.

- Meyerson, D., & Tompkins, M. (2007). Tempered radicals as institutional change agents: The case of advancing gender equity at the university of Michigan. Harvard Journal of Law & Gender, 30, 303–322.

- Moore, K., McDonald, P., & Bartlett, J. (2017). The social legitimacy of disability inclusive human resource practices: The case of a large retail organisation. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(4), 514–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12129

- Müller-Jentsch, W. (2004). Theoretical approaches to industrial relations. In Kaufman BE (Ed.), Theoretical perspectives on work and the employment relationship (pp. 1–40). Industrial Relations Research Association.

- Munir, K. A. (2015). A loss of power in institutional theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 24(1), 90–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492614545302

- Nelson, D. M., Brooks, S. L., Sahaym, A., & Cullen, J. B. (2017). Family-friendly work perceptions: A cross country analysis. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 32(4), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-03-2016-0066

- Nishii, L. H. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1754–1774. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0823

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/258610

- Özbilgin, M., Syed, J., & Dereli, B. (2010). Managing gender diversity in Pakistan and Turkey: A historical review. In Klarsfeld A (Ed.), International handbook on diversity management at work (pp. 11–26). Edward Elgar.

- Özbilgin, M., & Tatli, A. (2011). Mapping out the field of equality and diversity: Rise of individualism and voluntarism. Human Relations, 64(9), 1229–1253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711413620

- Ozgener, S. (2008). Diversity management and demographic differences-based discrimination: The case of Turkish manufacturing industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(3), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9581-3

- Öztürk, M. B., & Özbilgin, M. (2014). From cradle to grave: The lifecycle of compulsory heterosexuality in Turkey. In Colgan F, Rumens N (Eds.), Sexual orientation at work contemporary issues and perspectives (pp. 166–179). Routledge.

- Pancevski, B. (2018). Turkish president Erdogan’s visit to Germany proves tricky for Merkel. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/turkish-president-erdogans-visit-to-germany-proves-tricky-for-merkel-1538150321.

- Peretz, H., Levi, A., & Fried, Y. (2015). Organizational diversity programs across cultures: Effects on absenteeism, turnover, performance and innovation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(6), 875–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.991344

- Pesch, R., & Ipek, E. (2017). Refugees’ stress coping and social support: A qualitative study of employed refugees in Germany. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2017(1), 15884. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2017.15884abstract

- Pudelko, M., Reiche, B. S., & Carr, C. (2015). Recent developments and emerging challenges in international human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.964928

- Rao, H., Morrill, C., & Zald, M. N. (2000). Power plays: How social movements and collective action create new organizational forms. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22, 237–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(00)22007-8

- Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group & Organization Management, 31(2), 212–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104273064

- Romani, L., Boussebaa, M., & Jackson, T. (2020). Critical perspectives on cross-cultural management. In Szkudlarek B, Romani L, Caprar DV and Osland JS (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of contemporary cross-cultural management (pp. 51–65). SAGE.

- Roos, H., Mampaey, J., Huisman, J., & Luyckx, J. (2020). The failure of gender equality in academia exploring defensive institutional work in Flemish universities. Gender & Society, 34(3), 467–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220914521

- Schmidt, W., & Müller, A. (2013). Social integration and workplace industrial relations: Migrant and native employees in German industry. Relations Industrielles, 68(3), 361–386. https://doi.org/10.7202/1018432ar

- Schreiblmayr, I., & Reichel, A. (2022). At the European intersection: the Austrian way to equality, diversity and inclusion. In Klarsfeld A., Knappert L., Kornau A., Ng E. and Ngunjiri F. (Eds), Research handbook on new frontiers of equality and diversity at work. International perspectives (pp. 16–35). Edward Elgar.

- Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Foundations for organizational science. SAGE.

- Seierstad, C., Warner-Søderholm, G., Torchia, M., & Huse, M. (2017). Increasing the number of women on boards: The role of actors and processes. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(2), 289–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2715-0

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed). SAGE.

- Stringfellow, E. (2012). Trade unions and discourses of diversity management: A comparison of Sweden and Germany. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 18(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680112461094

- Stringfellow, E. (2020). Ideas at work: A discursive institutionalist analysis of diversity management and social dialogue in France, Germany and Sweden. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(19), 2521–2519. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1454489

- Styhre, A. (2014). Gender equality as institutional work: The case of the Church of Sweden. Gender, Work & Organization, 21(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12024

- Süddeutsche Zeitung (2021). Das gehetzte Parlament. https://projekte.sueddeutsche.de/artikel/politik/bundestag-das-gehetzte-parlament-e953507/

- Sürgevil, O. (2010). Is diversity management relevant for Turkey? Evaluation of some factors leading to diversity management in the context of Turkey. In Syed J, Özbilgin M (Eds.), Managing cultural diversity in Asia (pp. 373–392). Edward Elgar.