Abstract

This review examines the perceived employability of skilled migrants (SMs) through an analysis of 88 management and organisational research articles published over 2009-2019 period. We find the extant literature characterised by context-specific studies featuring considerable variety in terms of levels of analysis, theory, and content. Using the notion of perceived employability, key themes in the literature are identified and presented in an integrative framework. The framework encompasses individual, organisational, occupational, and institutional components of the perceived employability of SMs, different forms of work transition and associated mediators (broadening strategies) and moderators (transition conditions). Proposing adoption of process thinking for future research, suggestions regarding the interaction of individual and contextual components of perceived employability and the mediation and moderation mechanisms in the process of work transition are outlined.

Introduction

The International Labour Organisation has estimated that there are 234 million migrants of working age worldwide constituting 4.7% of the global workforce. The proportion of migrants in the workforce in high-income countries (e.g. Australia, Canada, Germany, France, Singapore, Sweden, UK, USA, Qatar) is 18.5% (Popova & Özel, Citation2018). Skilled migrants (SMs) also known as qualified immigrants are a subgroup of migrant workers and refer to individuals with a post-secondary education or equivalent training and with an intention to reside and work permanently and legally in a country other than their country of birth (Cerdin et al., Citation2014; Hajro et al., Citation2019). SMs are significantly different from other migrant worker groups, such as corporate expatriates or self-initiated expatriates, in their motives, needs, and attitudes towards sociocultural integration and their durations of stay (Baruch et al., Citation2013; Farcas & Goncalves, Citation2017; Przytuła, Citation2015). Prior reviews have examined the experiences of corporate expatriates and self-initiated expatriates at the workplace (e.g. Baruch et al., Citation2016; Shaffer et al., Citation2012). Some reviews analysed a broad literature and attempted to identify opportunities to integrate insights from other disciplines (e.g. traditional expatriate studies, psychology, sociology, ethnic and migration studies) into SM research. Hajro et al. (Citation2019) attempted to apply research on corporate-assigned and self-initiated expatriates to the investigation of skilled international migrants’ acculturation, coping and integration-related outcomes. Tharenou and Kulik (Citation2020) reviewed a multidisciplinary body of research and focused on socialization of skilled migrants after employment in developed and mature economies. Shirmohammadi et al. (Citation2019) reviewed the empirical findings on qualification-matched employment of SMs across multiple disciplines including limited number of journals (17) in management and organisation field. However, to our knowledge, there is no systematic review and integration of empirical studies on skilled migrants in the management and organisation field, covering the whole process of job-seeking, employment and career development across countries and occupations.

SMs in general are more educated than the native population (OECD et al., 2019) and their human capital and talent are considered a source of competitive advantage to the host country (Zikic, Citation2015) and a solution to social issues and problems, such as the ageing population in industrialised countries and shortage in skilled labour in certain occupations (Lu et al., Citation2016; Silvanto et al., Citation2015). Despite the potential impact of this group of individuals on economic and social outcomes of the host country, there is a paucity of reviews of empirical studies on SMs, hence the focus of our investigation. In addition, SMs face challenges in finding employment fitting their levels of education and experience; disparities in their employment outcomes are widespread (Tharenou & Kulik, Citation2020). Non-relevant work, over-qualification, involuntary reduced employment, precarious employment and working under inferior conditions are abundant (Covell et al., Citation2017; Humphries et al., Citation2013; Mahmud et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, Dietz et al. (Citation2015) identified a particular bias against SMs, migrants ‘are more likely to be targets of employment discrimination the more skilled they are’ (p. 1318). As an effort to provide a synthesized review, we attempt to identify and categorise factors at the individual, organisational, and institutional levels, which may influence SMs’ employability and their work transitions in the host countries.

Research on SMs is emerging and growing fast. We identified 88 relevant papers in management and organisation journals published in the period 2009-2019. Also, one paper published in 2002 was added as it was cited and indicated as highly relevant by other papers in our sample. The previous research on SMs in the management and organisation literature have been fragmented, with some studies featuring an atheoretical, explorative approach while others draw on an assortment of theories (Farashah & Blomquist, Citation2021b), including human capital, career capital, sense-making, Bourdieu’s theory of practice, social identity, and intersectionality (as exhibited in the Appendix). In the present review, we incorporate elements from prior research and develop an integrative framework to guide future studies. We use the concept of ‘employability’ to integrate the studies on SMs that have a diverse spectrum including the method, theory and geography. Employability is a concept that has become particularly relevant in the context of adverse employment conditions (Rothwell et al., Citation2009) and is therefore appropriate for studies of migrant employment.

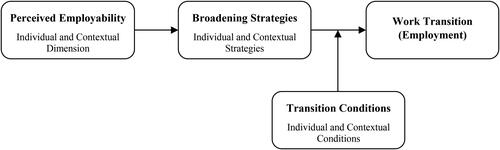

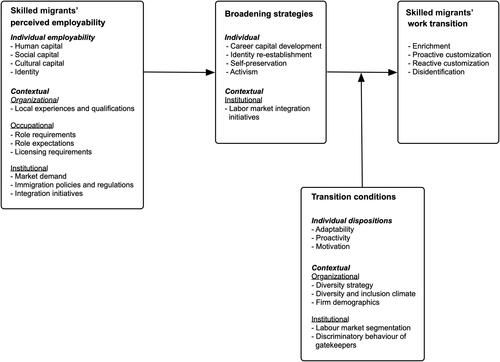

Indeed, finding appropriate employment and career reconstruction are central within the migration experience (Cohen et al., Citation2011). While the employment challenges faced by SMs are well documented, less is known about the process of finding employment (Colakoglu et al., Citation2018). Focusing on the process that migrants go through as they strive to re-establish their careers from scratch, this review summarises the findings regarding employment in three categories: (a) perceived employability, pertaining to SM’s appraisal of their chance of employment including the individual and contextual factors that influence this appraisal, (b) broadening strategies, referring to the initiatives and strategies that SMs and host societies devise to increase SMs’ level of employability, and (c) work transition, referring to SM’s eventual employment types (e.g. either positive such as a professional job or negative such as an overqualified position).

The next section elucidates the employability framework that we use to analyse the literature. Then, our method for identifying the relevant literature and the inclusion criteria are explained. We then summarise the current state of knowledge regarding SMs’ employability, strategies for broadening employability, and work transitions. Current knowledge gaps in the literature are discussed, and subsequently, we propose areas for future research that could move the SM research forward.

Conceptualisation of the employability of SMs

Despite stated need for more flow of skilled workers across borders, skilled migrants experience barriers to enter the labour market (Fang et al., Citation2009) and frequently face long periods of unemployment upon entry to a new country. Even, after being employed, they are likely to have longer paths to socialization and network development (Legrand et al., Citation2019; Tharenou & Kulik, Citation2020) and are likely to experience overqualification, underemployment, and instability in their employment such as short contracts and frequent lateral movements across professions and sectors (Cohen et al., Citation2011; Farashah & Blomquist, Citation2019; Holgate, Citation2005). In such an insecure environment, developing one’s career trajectory can be framed as an individualised life project in a new country that includes reflexive and self-conscious planning (Tomlinson, Citation2013, p. 22). Therefore, the notion of ‘employability’ appears to be an appropriate construct for research on SMs because it focuses on individual competencies and characteristics that lead to employment. However, when assessing their levels of employability and chance of finding an appropriate position, SMs also consider contextual factors (e.g. employers’ needs, economic situation, and societal norms and attitudes) in addition to their individual characteristics (De Cuyper & De Witte, Citation2011). Therefore, we differentiate among the constructs of ‘employability’ from ‘perceived employability’ (hereafter, ‘PE’), and ‘work transition’. Employability is a person-centred construct and represents individual characteristics that promote the prospect of employment, such as human capital, social capital, and career identity (Fugate et al., Citation2004); perceived employability refers to the appraisal of the employment prospect, taking into account the external structural factors that affect the chance of employment (Forrier et al., Citation2015). PE sees the actual employment (i.e. work transition) as a result of an interaction of a migrant’s agency and external contextual factors. Therefore, PE that integrate internal individual factors and external contextual factors is the focus of the paper.

Work transition is not always a desired outcome and sometimes SMs are employed as low-skilled workers or are forced to abandon their professional identity. When SMs with a relatively high level of human capital enter a new country, they are often surprised that their human capital is devalued and, consequently, their perception of employability decreases. This leads a SM to assess their chance of employment (i.e. their PE) to be too limited, subsequently broadening strategy would be a logical response. Smith (Citation2010) argued that during the time of turbulence, disruption, and unpredictability -which matches the situation of migrants in a new labour market- continuous learning and maintaining/enhancing the level of employability becomes a key component of working life. For SMs, since they do not have immediate access to the formal training opportunities inside the host country companies or to local professional networks, it is essential to proactively and continually look for ways of developing their human capital, learning how to look for jobs and networks. These broadening activities are mostly unpaid and often happen outside the formal job structures. Although the host society sometimes might devise strategies and engage in initiatives to increase the likelihood of increasing SMs’ employment. The responsibility of planning and execution is mainly on the shoulders of individual employee/jobseeker (Smith, Citation2010).

An increased PE as a result of broadening does not necessarily lead to employment (i.e. work transition) (Thijssen et al., Citation2008). For this to happen, two types of transition conditions are required: (1) individual conditions related to career competencies, such as career planning and job-efficient search methods, and (2) contextual conditions, such as the labour market demand, regulations, and company support. Based on Thijssen et al. (Citation2008) model, Transition conditions are thus the moderators of the association of PE and actual employment.

We used the perceived employability framework (see ) to code and synthesise the literature. The inclusion of individual and contextual factors in this framework allows us to adopt a multi-level approach and to consider several levels of analysis (i.e. individual, organisational, professional, and societal). This follows the recommendation of prior researchers to apply a multilevel (relational) approach to the study of migrant workers (Al Ariss & Syed, Citation2011; Hajro et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the framework has a process view and takes into account the effects of the individual and broadening strategies on PE and work transition over time.

Method

Selection of the articles

We reviewed empirical articles published in scientific journals ranked according to their impact factor by the Web of Science 2018 Journal Citation Report. Journals indexed under international business, general business and management, applied psychology, organisational behaviour, human resource management, and industrial relations fields were included. We conducted a systematic review (Denyer & Tranfield, Citation2009) from the advent of SM studies in the field (2009–2019). All journals with an impact factor within management and organisation were included and no cut-off point for the impact factor was set. Targeted articles were identified using all possible combinations of the search terms ‘qualified/skilled/professional/educated’ and ‘migrant/immigrant’ and ‘employability/employment/career/work’. The terms ‘qualified’ (Cerdin et al., Citation2014), ‘skilled’ (Silvanto et al., Citation2015; van den Broek et al., Citation2016; Winterheller et al., Citation2017), ‘professional’ (Lu et al., Citation2016; Shenoy-Packer, Citation2015), and ‘educated’ (Clarke et al., Citation2018; Simola, Citation2018) are used interchangeably in the literature. As migration is associated with periods of job searching, temporary jobs, or underemployment (e.g. part-time job, survival job, or over-qualification) as well as with securing a job relevant to the individual’s qualifications, the terms ‘work, career, and employment’ were added in order to cover the whole work experience of SMs. The initial search without restricting the search to management and organisation journals lead to about 1600 papers on the subject including economics, sociology, political science, and migration streams of research. To be able to manage the review process, the search was limited to management and organisation research. The first group of papers including 144 articles then obtained as the starting point.

The management and organisation studies on SMs have started to emerge from 2009. Only one article (Salaff et al., Citation2002) earlier than 2009 was identified. We screened the abstracts and then read the full text of identified articles led to the exclusion of 50 articles. These articles covered topics, including short-term and temporary stays, study, or internships (e.g. Bahn, Citation2015; Toh et al., Citation2009; Zimmermann & Ravishankar, Citation2011); non-documented and unauthorised employment (Bohn & Owens, Citation2012; Marfleet & Blustein, Citation2011); historical data (e.g. Borjas, Citation2011; Constant, Citation2009; Grönberg et al., Citation2015); repatriation (e.g. Jonkers & Cruz-Castro, Citation2013; Qin & Estrin, Citation2015); pre-migration period (e.g. Qin, Citation2015) or inclusion of low-skilled migrant labour (e.g. Baxter-Reid, Citation2016; Bell et al., Citation2010; Friberg et al., Citation2014; Lima & Martins, Citation2012); or the inclusion of skilled self-initiated expatriates in the sample (e.g. Ford & Kawashima, Citation2016; te Nijenhuis et al., Citation2014). Six conceptual articles were excluded (e.g. Crowley-Henry & Al Ariss, Citation2018; van den Broek et al., Citation2016; Zikic, Citation2015).

Different categories of skilled migrants were included, such as forced migrants or refugees (Eggenhofer-Rehart et al., Citation2018; Gericke et al., 2018), accompanying partners (Mayes & Koshy, Citation2018; Riano et al., Citation2015), and migrants on temporary visas with the possibility of extension to permanent residency (Almeida & Fernando, Citation2017; Boese et al., Citation2013). Articles focusing on SMs in low skilled jobs were also included. At the end, a total of 88 articles were included in the final round of review. The articles were published in 47 journals. The ‘International Journal of Human Resource Management’ with 9 articles, ‘Work, Employment and Society’ with 7 articles and ‘Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal’ with 6 articles were the top publishing outlets.

Coding of the content of the articles

Each article first was coded based on the study’s methodology, unit of analysis, the SM’s country of origin and host country, and the profession/occupation of the SMs. shows the scope and methodology of articles analysed in our review We used the perceived employment framework to code and synthesise the literature ().

Table 1. Scope of skilled migrant studies: Occupation, region and publication year.

Table 2. Scope of skilled migrant studies: methodology, level of analysis and topic.

An initial deductive coding was undertaken for analysing the articles. The coding structure was based on the main constructs of the perceived employability framework () including perceived employability (individual and contextual factors), broadening strategy (individual and contextual factors), transition condition (individual and contextual conditions) and work transition (individual). The Appendix provides an overview of the articles included in this review and the results of the initial coding. Then, the initial coding was further developed by categorising the finding in further detail. The main findings regarding the four themes of the framework are presented in the following sections and an overview is presented in .

Perceived employability of SMs

PE concerns the appraisal of employment prospects and implies a combination of individual employability and structural factors at the level of the organisation, occupation/profession, and society (Vanhercke et al., Citation2014). Individual and structural dimensions of PE that were identified in the analysed SM studies are discussed below.

Individual dimensions of perceived employability

At the individual level PE focuses on ‘the extent to which people possess the skills and other attributes to find and stay in work of the kind they want’ (Rothwell & Arnold, Citation2007, p. 23) and includes the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics valued by employers. Following Fugate et al. (Citation2004) definition of employability, we included ‘human capital’, ‘social capital’, and ‘identity’ dimensions, and coded them in the literature. Additionally, the dimension of ‘cultural capital’ emerged as a new theme. Bourdieu’s theory of practice (Al Ariss et al., Citation2013) and career capital theory (Cooke et al., Citation2013) are the main theoretical approaches that discuss the influence of cultural capital on a SM’s employability. A summary of each of these individual determinants of perceived employability is presented below.

Human capital. In line with human capital theory, the accumulated knowledge, skills, and abilities of SMs through education and work experience is the most frequently cited individual level components of employability (e.g. Al Ariss & Syed, Citation2011; Almeida & Fernando, Citation2017; Covell et al., Citation2017; Fang et al., Citation2009; Tyrrell et al., Citation2016). Our review focused on SMs who are highly educated and skilled, and their human capital is often high. Commonly, though, SMs’ human capital is not as well regarded by current and prospective employers in their host countries as by employers in their countries of origin. SMs are targets of employment discrimination the more skilled they are (Dietz et al., Citation2015). In addition, lack of language proficiency can lead to difficulty in professional communication and presentation skills; little or no local or international work experience can be considered an indicator of lower levels of competency and performance in the eyes of employers (Cooke et al., Citation2013; Hakak et al., Citation2010). Previous work experience in multinational corporations (Cooke et al., Citation2013) and having graduated from reputable schools can reduce such negative evaluations (Duvivier et al., Citation2017).

Demographic characteristics also matter. One specific dimension that is studied frequently is gender. While SMs of both genders are challenged by many similar barriers, females encounter additional disadvantages because of gender-related factors. Due to their gender role of caregiver versus male role of provider, women spend more time in providing care and household tasks at the expense of their career progress (Sang et al., Citation2013). Being form specific countries such as Muslim countries, their appearance and visibility can be a barrier (Faaliyat et al., Citation2021). Using intersectionality theory, some studies (e.g. Fullin, Citation2016; Karlsen, Citation2012; Mayes & Koshy, Citation2018; Sang et al., Citation2013) examined the interaction of gender with ethnicity and religion. A negative effect of traditional gender roles or masculine norms of a profession on the employability of skilled female migrants was found. Hilde and Mills (Citation2017) and Mulinari (Citation2015) identified different cognitive processes that male and female SMs adopt to cope with the lower employability levels related to their (new) immigrant status. Length of stay in the destination country is related positively to employment matched to the level of human capital, as it is associated with language proficiency, qualification recognition, and the acquisition of cultural knowledge (Lu et al., Citation2016).

Social capital. Migrants have less social capital, professionally and more broadly, compared to the nationals in the host country (Chung, Citation2013; Lane & Lee, Citation2018; Ressia et al., Citation2017a). According to career capital theory, the loss of social capital leads to lower levels of employability (Cooke et al., Citation2013; Gericke et al., Citation2018). Spouses and extended families (Colakoglu et al., Citation2018), ethnic communities, religious groups, and migrants who share their experiences and friends (Koert et al., Citation2011) are vital resources for SMs to maintain self-esteem and psychological well-being. Social contacts in the home and host countries can provide information and guidance regarding the culture and the labour market, hence acting as intermediaries (e.g. through friends of friends) who can influence career-related and even migration decisions in the first place (Harvey, 2012; Ryba et al., Citation2016).

Cultural capital. Coming from similar societies and countries with less cultural disparity, such as those that use the same language and have postcolonial relationships, can lead to a higher level of cultural capital (Mahmud et al., Citation2014). Not understanding the culture of the host country (Al Ariss & Syed, Citation2011; Guerrero & Rothstein, Citation2012) or its work culture and business thinking (Berthou & Buch, Citation2018; Legrand et al., Citation2019), such as different attitudes towards work (Rajendran et al., Citation2017) or different norms around socialisation, networking, and job seeking (Chung, Citation2013; Rajendran et al., Citation2017), can affect the employability and performance of SMs. Even, not being a graduate of a specific school can be a barrier (Legrand et al., Citation2019). Non-work-related cultural artefacts can also have both negative and positive effects on SMs employability. The artefacts that have negative effects include, for example, lacking a frame of reference for the things clients talk about, being perceived as intellectually inferior due to the lack of knowledge of cultural icons (Chung, Citation2013), or not being able to participate in informal interactions due to different hobbies, sport interests, etc. (Cooke et al., Citation2013; Hakak et al., Citation2010). However, some SMs may have a better chance of employment due to their knowledge and experience of their country of origin. Being bilingual and bicultural – and mobilising this cultural capital – enables SMs to act as cultural brokers and to bridge, link, and mediate between cultures and countries (Fernando & Cohen, Citation2016; Legrand et al., Citation2019; Winterheller et al., 2017). For instance, being a member of a particular ethnic group provided some academics with the opportunity to do research on a local community that resulted in better publications and career advancement (Sang et al., Citation2013; Sang & Calvard, 2019). It allowed other skilled workers to act as a new layer of intermediaries in a contractual chain of the construction industry and attract higher incomes (Shin & McGrath-Champ, Citation2013). It enabled individuals to be employed in jobs that serve co-ethnic clients or the market of the home country (Almeida et al., Citation2012; Cooke et al., Citation2013) and provided a competitive advantage for migrant export entrepreneurs over non-migrant business owners due to their international networks (Neville et al., Citation2014). However, such cultural brokers sometimes remain in positions well below their original high-skilled level jobs in their home countries (Liversage, Citation2009).

Identity. Identity conflict is a common theme in studies of SMs. Identity can be considered from the perspectives of cultural identity and occupational identity. Regarding the former, SMs have to choose (a) to retain or dismiss their original cultural identity and (b) to adopt or exclude the cultural identity of the host group, choices that result in four types of acculturation: assimilation (dismissing the original cultural identity and adopting cultural identity the new country), integration (keeping the country of origin cultural identity while mastering the new identity), separation (keeping the country of origin cultural identity and distancing themselves from the cultural identity of the new country), and marginalisation (Dheer & Lenartowicz, Citation2018; Lu et al., Citation2016).

Occupational identity is an important topic of study too, given the central position of work and career status in a SM’s life in general and in particular the connection to the pre-migration time (Davey & Jones, Citation2019; Yu et al., Citation2015) and also the fact that greater career opportunities are the main motivator behind their decision to migrate (Zikic et al., Citation2010). Barriers to transferring their human capital and language levels can clash with SMs’ belief that their skills and qualifications would provide a firm basis for their new lives and a meaningful employment. This leads to feelings of non-belongingness and not being equal to peers, a loss of status, and an altered sense of identity (Chung, Citation2013; Clarke et al., Citation2018). In this regard, experiencing a broken self (Zhang & Chun, Citation2018), an in-between self (Hilde & Mills, Citation2017), and not being yourself (Zikic & Richardson, Citation2016) were reported in previous studies.

In addition, although global professions and globally accepted professional certificates act as an enabler of migration, SMs’ professional identity re-establishment can be lengthy and difficult due to regulatory hurdles for licensed professions (Yu et al., Citation2015). Accordingly, SMs may decide to maintain their professional identity or re-evaluate their career and personal aspirations and develop a new identity. Occupational/professional identity has been discussed in prior SM studies, mainly through the lenses of sense-making and critical sense-making.

Organisational dimensions of perceived employability

Local experiences and qualifications. Human capital is not completely transferable across labour markets. When assessing SMs, organisations will evaluate person–organisation fit in addition to person–job fit, and herein a preference for local experience and qualifications is frequently reported (Alfarhan & Al-Busaidi, Citation2018; Hakak et al., Citation2010; Hilde & Mills, Citation2017). Newly arrived SMs often face non-recognition or devaluing of their foreign qualifications and experiences, due to the unfamiliarity of employers with their previous companies and educational institutions. The perception of SMs’ qualifications as being dissimilar, less useful, or insufficient (Kahn et al., Citation2017; Klingler & Marckmann, Citation2016) by their new employers leads to lower levels of PE. Employers perceive local education and experience as a signal of having a higher level of communication skills, an acceptance of societal values, and a capacity to fit with the organisational culture and the needs of the clients (Almeida & Fernando, Citation2017).

Occupational/professional components of perceived employability

Role requirements Occupations or jobs that require day-to-day operations based on local knowledge and experience can lead to a lower chance of migrants being offered that job (Almeida et al., Citation2012). SMs have a lower chance of employment in occupations that require greater interpersonal communication skills and informal human capital (Rosholm et al., Citation2013). Peri and Sparber (Citation2011) showed that, while SMs generally enter into occupations demanding quantitative and analytical skills, their native-born counterparts specialise in occupations requiring interactive and communication skills.

Role expectations. Occupational role expectations in a host country can also be a barrier to employment. For instance, expectations of a nurse’s role being more concerned with the emotional and spiritual support of patients or that nurses will be experienced in treating the common illnesses among the population of the host country (Takeno, Citation2010) can hinder migrant nurses who do not share these professional role expectations entering the profession.

Licensing requirements. A profession being regulated appears to be a significant career barrier for SMs. Licensing processes are long and complicated (Banerjee & Phan, Citation2014) and in many cases, the processes demand completion of bridging courses, extra degree-level education (Boese et al., Citation2013), or mandatory examination (Thomson & Jones, Citation2015). In addition, researchers have noted subjective, informal, and subtle ways that a profession’s norms can affect PE. For instance, a SM may be asked to transform their dress, appearance, accent, and manner, such as speaking up in meetings (Thomson & Jones, Citation2015) – in particular, in collegiate professions like medicine with a centralised power system in a national jurisdiction (Zikic & Richardson, Citation2016). In this context, professional regulation structures and processes are used to reconstruct the same dominant cultural hierarchy within the professions (Cameron et al., Citation2019), and the assessment of person–occupation fit is used as a rationale to justify the hierarchy’s reconstruction (Almeida & Fernando, Citation2017).

Institutional dimensions of perceived employability

Market demand. Shortages within specific workforces are a driver of migration, and host countries formulate policies to attract skilled migrants (Almeida et al., Citation2015). Vacant positions due to a lack of skilled professionals in the local market (Adhikari & Melia, Citation2015; Al Ariss et al., Citation2013; Berthou & Buch, Citation2018; Takeno, Citation2010) and a larger labour market (Allmen et al., Citation2015) provide SMs with greater bargaining power and make their work transitions less challenging. In such circumstances, the place and timing of a SM’s entry into the labour market are crucial. For example, a SM relocating in a smaller city or rural area with an almost non-existent labour market (Mayes & Koshy, Citation2018) or entering a country experiencing an economic crisis (Casado & Caspersz, Citation2016; Cueto & Alvarez, Citation2015) would perceive lower levels of employability.

Immigration policies and regulations. Non-recognition of qualifications is common among migration officials (Lane & Lee, Citation2018), but a mutual recognition agreement between countries (e.g. the Washington Accord with respect to the engineering profession) (Cameron et al., Citation2019) and establishing clear and objective licensing requirements for foreign-trained applicants (Banerjee & Phan, Citation2014) can facilitate accreditation recognition.

A country’s immigration policy framework is another influential factor (McGuire & Lozada, Citation2017) for SMs, either acting as a barrier (Alfarhan & Al-Busaidi, Citation2018) or an incentive (Almeida et al., Citation2015). Migration regulations that lack certain basic protection of workplace rights of SMs, such as work authorisation, the right to remain permanently in the country, not having to depend on a third party for one’s right to remain, equal access to public goods such as education and health care, and the right to sponsor and reunify family members (Boese et al., Citation2013), are challenging as they create precarious employment practices. Thus, transparency of government policymaking is the strongest predictor of international talent attraction (Silvanto et al., Citation2015). Conversely, implicit and indeterminate administrative practices (Simola, Citation2018), overly bureaucratic and confusing rules and regulations (Klingler & Marckmann, Citation2016), a lack of synergy at the national level in terms of important information not being shared (Klingler & Marckmann, Citation2016), contradictions between different agencies and institutions (Al Ariss, Citation2010), or conflicting policies (Harvey, Citation2012) are examples of hurdles that a poor policy framework can create.

Integration initiatives. Government and community initiatives regarding counselling, language study, free community centre programmes, pre-departure and settlement workshops, and, in particular, employment-related workshops and labour market integration initiatives would increase PE level (Clarke et al., Citation2018; Koert et al., Citation2011; Ponzoni et al., Citation2017; Winterheller et al., 2017).

Broadening strategies

SMs commonly perceive that they have a lower level of employability following migration (Tharenou & Kulik, Citation2020). Accordingly, they or other actors in the labour market exercise their agency and might formulate strategies and initiatives to enhance the individual dimensions of PE (e.g. learning the language) or reduce the structural barriers (e.g. internship offers). A typology of broadening strategies is presented in section below.

Individual broadening strategies

In our review of the literature, we identified four themes of broadening strategies that a SM can apply using the available resources: (1) career capital development, which refers to efforts to acquire and convert career capital in the new surroundings; (2) identity re-establishment, or a range of strategies to reconstruct threatened identity that occurs because of significant changes in an migrant’s life and career; (3) self-preservation, or sustaining the integrity of the self and maintaining self-esteem; and (4) activism, or proactively attempting to change the institutional arrangements at the host country to make it more favourable for migrants. In the following subsections, these broadening strategies and their career outcomes and transitions are discussed.

Career capital development. As human, social, and cultural types of capital are not completely transferable and, overall, are valued less in the new labour market, the logical choice for SMs is to acquire a type of career capital that is valued. Through such career self-management, SMs can acquire local education and training, learn the language, adopt local job application practices and obtain job-relevant knowledge and skills, and actively establish a social network (Eggenhofer-Rehart et al., Citation2018; Koert et al., Citation2011; Ressia et al., Citation2017b; Zikic et al., Citation2010). Doing this requires a putting lot of time and efforts and even personal investment (Sarpong & Maclean, Citation2019). Such efforts result in SMs developing ‘knowing what’ (professional knowledge and skills; social and cultural skills), ‘knowing why’ (discovering their own career motivation and career goals), and ‘knowing whom’ (developing personal relations and networks that could influence their career) competencies (Hirt et al., Citation2017).

Social capital expansion can be achieved through networking based on shared nationality or ethnicity (ethnic enclaves (Cueto & Alvarez, Citation2015), homophilious networks (Hakak et al., Citation2010), bonding networks (Gericke et al., Citation2018) or through networking with locals and internationals (bridging networks; Gericke et al., Citation2018). Expansion also can be horizontal (i.e. with contacts with a similar relative social status) or vertical (i.e. with contacts from higher social levels and in possession of valuable resources and an extensive knowledge network). Bridging and vertical expansion has been shown to be connected to better job transition (Gericke et al., Citation2018; Rajendran et al., Citation2017).

However, SMs’ careers often start with menial jobs or wage-supported temporary training positions to support the family while the SM attempts to become licensed (Banerjee & Phan, Citation2014; Liversage, Citation2009), non-linear career entries (underemployment, unemployment, volunteer and domestic work) (Colakoglu et al., Citation2018), and capacity building (e.g. employment in a relatively junior position in a small organisation, followed by an internal promotion, and then a move to a larger and more reputable organisation while benefiting from mentoring and training provided or sponsored by the employer; joining professional associations) (Cooke et al., Citation2013; Winterheller et al., 2017). When a SM thinks she or he had reached the glass ceiling, intentional and change in career direction or work environment is a strategy to bypass the obstacle (Legrand et al., Citation2019).

Another aspect to consider is the family dynamics. While SMs act as individuals, they might come with an accompanying partner with a similar level of skills facing similar challenges. In such cases, often commitment to the children and traditional gender roles are additional barriers for female partners (Cooke, Citation2007). However, the broadening strategies are negotiated between two partners and sacrificing one’s career for the sake of stability of the family or instability of marital status due to career progression may likely occur.

Identity re-establishment. Social identity interacts with professional identity; for instance, it sets a SM’s predisposition to develop a bonding or bridging network (Gericke et al., Citation2018). Thus, the re-establishment of social identity also influences a SM’s employability. Lu et al. (Citation2011, Citation2016) used Berry’s (1990) model of acculturation, including four strategies of integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization. They showed that higher levels of acculturation and adapting to the identity of the new country are associated with career success. In the present review of the management and organisation literature, we could not find any empirical examination of the effect of maintaining or retaining their ethnic identity on the career outcome of migrants. Dheer and Lenartowicz (Citation2018) hypothesised that migrants who reinforce their original cultural identity will likely display greater embeddedness in their ethnic enclave than in the host society and will therefore have a higher likelihood of ethnic employment and entrepreneurship, which may lead to employment in low-skilled jobs or underemployment. However, acculturation research in psychology literature offers a more nuanced conception and a better understanding of acculturation outcomes. A study by Birman et al. (Citation2014) offers insights regarding the different mechanisms of effect of adherence to home or host culture on occupational adjustment, life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Schwartz et al. (Citation2010) criticised Berry’s model regarding it’s ‘One Size Fits All’ approach due to not considering variations among migrant like type (e.g. refugees vs. self-initiated), the age of migration (i.e. migration as child, adolescent, or adult), the ethnic origin and cultural similarity (e.g. European vs. non-European for migrants in Western countries). They instead introduced a multi-dimensions model of acculturation to distinguish three dimensions for acculturation including behavioural, value and identity. It should be noted that identity re-establishment can also be a result of downward occupational mobility. When a professional identity is not reconstructed in the new society, the SM might abandon the professional identity or seek establish a new identity (e.g. becoming a philanthropist).

Some SMs initially experience a shock and internal conflict due to a significantly lower level of PE. They may put their professional/occupation identity on hold (e.g. taking ‘survival’ jobs until their qualifications are recognised). Responding to identity conflicts, a SM might navigate and evolve their own understandings within the cultural patterns of the new country and create narratives to give meaning and continuity to past, present, and future employment experiences. Sense-making processes result in different types of identity narratives associated with different types of work transition and future career trajectories. Migrants can also engage in identity exploration to try to understand, interpret, and master unfamiliar norms and practices, which leads to meaning reconstruction. SMs might choose to stick to their existing professional identity, develop a new identity, or abandon their professional identity. Different types of identity reconstruction and the results in terms of work transition and upward or downward occupational mobility are discussed in the Work Transition section below.

Self-preservation. Identity conflict is a significant stressor and is associated with depression, divorce, and even suicidal intentions (de Vries et al., Citation2016; Hilde & Mills, Citation2017). Self-care activities for ‘the mind, body, spirit, and emotions’ (Koert et al., Citation2011) are therefore crucial to the self-esteem and psychological well-being of SMs.

Three types of proactive, reactive and disengaging self-preservation are identified. Proactive self-preservation includes ignoring structural barriers and instead engaging in self-reinforcing discourses, identifying with positive qualities such as ‘competent’ and ‘energetic’ (Hilde & Mills, Citation2017; Zhang & Chun, Citation2018), and picking up new hobbies or learning additional skills (Zhang & Chun, Citation2018). Reactive self-preservation includes seeking social support by joining groups of peers (e.g. migrants in a similar situation) or turning to religion (Mayes & Koshy, Citation2018; Murray & Ali, Citation2017). Disengaging self-preservation includes reducing or giving up one’s career aspirations and professional identity, admitting an inability to find employment, and turning to family and other work substitutes. Self-preservation would be challenging specially for newly migrated individuals as they have limited social and professional networks. Initiative by municipalities, local/regional government in collaboration with non-governmental organisations and companies and also ethnic enclaves are crucial in this stage for providing adequate emotional and social support (Lehtovaara & Jyrkinen, Citation2021).

Activism. Encountering a status quo that allows the dominant culture to exert its power and privilege, some SMs might choose to resist and challenge the structure. Occasionally, the struggles to find their own way motivate few SMs to really want to see fellow migrants go through the transition process smoother by coaching and mentoring new arrivals (Sarpong & Maclean, Citation2019). McGuire and Lozada (Citation2017) explored efforts towards institutional change, the formation of a migrant support group that teaches migrant workers what is acceptable regarding working conditions and provides advice in cases of abuse and inequality. Bornat et al. (Citation2011) showed how migrant doctors segregated into an unpopular specialty, that most locally born and trained medical graduates tried to avoid, contributed to the development of that specialty by enhancing standards and status while, at the same time, building their own careers.

Institutional broadening strategies

Participation in labour market integration initiatives. Integration initiatives such as internship programmes to place SMs temporarily in local organisations through wage-supported training positions (Liversage, Citation2009; Ponzoni et al., Citation2017) are common strategy for public or non-for-profit organisations to support migrants. The integration initiatives can provide individually adapted mentorship and coaching to promote a SM’s confidence and equip them with information critical to navigating the labour market and guiding their job search (Berthou & Buch, Citation2018). Training on writing job applications and CVs, administrative processes, professional terminology, and local work culture are considered critical and empowering by SMs (Berthou & Buch, Citation2018; Gericke et al., Citation2018). These institutional initiatives enhance PE as they usually offer relevant resources for SMs such as connection to networks of local employers, managers and professionals (i.e. increased social capital), training on subjects like language, labour market and culture (i.e. increased cultural capital), and formal professional education (i.e. being licensed or increased human capital) or short local job experiences.

In the present review, no study related to initiatives of organisations or professional associations to increase the employability level of SMs was found. This indicates the scarcity of such initiatives and the belief of organisations that employability and career management are personal responsibilities. However, when contacted by representatives of labour market integration initiatives, organisations are mostly willing to participate in the initiatives and provide internship opportunities and mentorship to SMs (Romani et al., Citation2019). Further investigating the effects of such integration interventions as institutional broadening strategies is undoubtedly a need in future research.

Work transition

Work transition (i.e. employment) happens through enrichment, reactive and proactive customisations, and disidentification (Zikic & Richardson, Citation2016). Each type of work transition is related to specific broadening strategies adopted by SMs.

Enrichment refers to positive change pertaining to the successful exploitation of opportunities provided by a new country and a higher level of PE comparing with the country of origin. The identity re-establishment would be to create an alternative professional identity or develop the current identity to a new level. Getting a dream job or self-employment (Fullin, Citation2016; Zikic & Richardson, Citation2016) are examples of such transitions that yield increased financial and career attainments, social status, and a sense of growth, accomplishment, and satisfaction. Relatedly, boundaryless careers are relevant concepts. Boundaryless career refers to ‘sequences of job opportunities that go beyond the boundaries of single employment settings’ (DeFillippi & Arthur, Citation1994, p. 307). Global careers now have become more boundaryless due to career actors’ increased proactivity in making career moves across organisational and national borders to develop their career competencies and marketability (Carr et al., Citation2005). In the context of our review, SMs can evaluate their career capital, informed by their past experiences and future possibilities, in making conscious decisions on crossing the boundaries of organisations, industries, professions, and nations.

Proactive customisation means re-establishing one’s original professional identity according to local employers’ needs by adopting, for example, a new vocabulary and communication style. Career capital development strategy would be used as a parallel strategy: SMs complete additional training and put efforts into learning and mastering the language, the domain-specific knowledge and skills, and the professional norms. They accept the adaptation responsibilities as they have chosen to migrate, embrace the status quo as normal, and try to modify their attitude, behaviour, and appearance to mimic locals (Sang et al., Citation2013; Shenoy-Packer, Citation2015; Thomson & Jones, Citation2015). In the long term, this strategy enables SMs to have a level of employability in the new market similar to that of the pre-migration period (Zikic & Richardson, Citation2016).

Reactive customisation occurs when SMs are unable to pursue their original identity due to structural barriers and therefore engage in a more flexible and broader job search without totally giving up their identity (i.e. identity shadowing) (Davey & Jones, Citation2019; Eggenhofer-Rehart et al., Citation2018). A doctor working as a technical assistant in a hospital or a professional nurse working in an elderly care institute are examples of such a strategy. Working within the borders of their profession but in an overqualified position, SMs may try to stay connected to their identity by using the terminology and interacting with professionals (Zikic & Richardson, Citation2016). Reactive customisation happens mostly when SMs are constrained by the power dynamics of a majority–minority relationship embedded within an institutional framework (e.g. non-recognition of their qualifications, employers’ perceptions that they lack appropriate social skills, lack of access to top-level managerial/professional positions due to licence requirements, normative role expectations and top-management/gatekeepers’ attitude). Since their levels of employability and professionalism are perceived to be lower than the pre-migration period, SMs might show higher levels of professional commitment and lower levels of organisation commitment and frequently move between organisations or become self-employed (Cueto & Alvarez, Citation2015; Sang et al., Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2015). SMs might also assign more value to the subjective dimensions of career success, such as having a noble career, a sense of calling, and providing for the family, to compensate for lower status or pay (Lane & Lee, Citation2018; Mulinari, Citation2015). Furthermore, reactive self-preservation appears to be mostly used alongside reactive customisation transition

The literature has shown that migrants are more likely to become entrepreneurs than natives (Kahn et al., Citation2017). Notably, there is a distinction between two types of transition towards entrepreneurial career. Reactive entrepreneurship is driven by necessity as migrants are a misfit and unable to find employment. It most likely involves a new occupational identity in the form of providing culture-bound products to culturally similar groups or within ethnic enclaves (e.g. opening a new restaurant) or self-employment in occupations with fewer entry barriers like (driving or owning a taxi agency). On the other hand, star entrepreneurship (described above as the enrichment transition) is generally opportunity driven, considered a dream job and upward occupational mobility among the migrant with high levels of human capital (e.g. science based entrepreneurship) (Kahn et al., Citation2017).

Disidentification refers to putting one’s occupational/professional identity permanently on hold or relinquishing it, such as through repatriation, remigration, long-term unemployment, and low-skilled work. Negative career outcomes such as talent waste, underutilisation of skills, skills atrophy, deskilling, de-credentialing, or discounting (Cameron et al., Citation2019; Eggenhofer-Rehart et al., Citation2018) are associated with this type of transition. Disengaging self-preservation is often used by SMs in this type of transition to maintain psychological well-being.

Transition conditions

Transition conditions moderate the PE–work transition relationship. Without the necessary conditions, PE would not be actualised, and work transition will not happen. Exercising individual agency and external interventions can assist in the occurrence of work transitions.

Individual dispositions

Related to the notion of individual agency, some SMs are able to understand themselves better and to navigate the new environment and pursue their career goals more effectively. The individual characteristics and traits are briefly noted in the literature. We identified adaptability, proactivity, and motivation as facilitators for a desired work transition.

Adaptability incorporates grit personality trait, perseverance, impulse control, and a passion for long-term goals (Chung, Citation2013; Colakoglu et al., Citation2018), interdependent self-construal (i.e. conceiving themselves as connected with the people of the host society) (Lu et al., Citation2016), resiliency and maintaining hopefulness (Clarke et al., Citation2018), a competency to accept and adjust to the new environment (Klingler & Marckmann, Citation2016), and working harder, faster, and accomplishing more to justify one’s presence and make oneself more valuable and attractive to prospective employers (Fernando et al., Citation2016; Mulinari, Citation2015; Rajendran et al., Citation2017).

Proactivity refers to migrant-initiated activities to learn and change. Examples include being self-reliant and having self-belief (Chung, Citation2013); setting specific goals, making plans, and time management (Koert et al., Citation2011); actively seeking information and support (Rajendran et al., Citation2017); and exploring career options and finding ways to exploit them (Eggenhofer-Rehart et al., Citation2018). Note that proactivity refers to initiating the change, while adaptability refers to responding and adjusting to it.

Motivation denotes a SM’s willingness to take part in activities and socialise, learn the new culture and language (Cerdin et al., Citation2014), show they are hardworking and reliable (Ponzoni et al., Citation2017), put their education and skills to use and return to high-level work (Liversage, Citation2009), have purpose and realistic expectations (Koert et al., Citation2011), promote their competencies and achievements (Cooke et al., Citation2013), and undertake intensive job searches (Guerrero & Rothstein, Citation2012).

Organisational characteristics

Diversity strategy. Diversity strategies influence the attraction and retention of SMs. Risberg and Romani (Citation2021) observe that some organisations portray migrants as a risk to local organisational practices and this logic of protection can lead to underemployment of SMs. On the other hand, an innovation logic and learning diversity strategy (a belief in the new perspectives that SMs may bring into the organisation) and an antidiscrimination diversity strategy (aiming to attract and retain the most qualified employees) have the strongest positive impact on developing international talents (Farashah & Blomquist, 2021a; Hirt et al., Citation2017). Similarly, a corporate social responsibility strategy or a diversity committee with independent resources specifically assigned to cultural diversity (Berthou & Buch, Citation2018) makes it easier to recruit more migrants.

Diversity and inclusion climate. The diversity and inclusion climate can affect the SM’s level of job satisfaction (Madera et al., Citation2016); one comprising a cohesive small group and an empathetic supervisor/mentor that accepts the SM and includes them in social activities at work as well as a formal induction programme introducing organisational norms regarding workplace interaction to new recruits can lead to a better job transition (Rajendran et al., Citation2017). Even when a SM enters at a junior position, such a climate enables them to learn the new norms and regain and promote their employability level.

Clientele and firm demographics. Organisations with a diverse ethnic client base are less concerned about the suitability of migrant candidates during recruitment and selection (Fernando et al., Citation2016; Ortlieb et al., Citation2014). Also, larger organisations provide better employment opportunities for SMs, due to resource availability (Almeida et al., Citation2012). Similarly, small businesses founded by a migrant employ friends, friends’ children, and people with similar ethnic bonds at a higher rate (Peri & Sparber, Citation2011). The age and ethnicity of senior managers can affect the selection process: for example, Fernando et al. (Citation2016) showed that White/Anglo Australian and older decision-makers had more suitability concerns regarding migrant candidates.

Institutional variables

Discriminatory behaviour of gatekeepers. Discrimination towards specific minority ethnic groups can bring about ethnicity-based penalty, overeducation issues, unemployment, and lower levels of wages (Rafferty, Citation2012). Examples of such discrimination include anti-immigrant sentiment from the majority of the nationals in the host country based on misconceptions and negative attributes being associated with migrants (DelCampo et al., Citation2011); stereotypes, unspoken judgements and biases surrounding migrants from a certain area or a certain migrant type (e.g. refugees) (Davey & Jones, Citation2019; Lane & Lee, Citation2018); countrified discriminatory management attitudes (Almeida et al., Citation2012); microaggressions like sarcasm and scepticism (Shenoy-Packer, Citation2015); or requiring migrants to reinforce an association with Western cultural traits and behaviours that are supposedly norms of the professional behaviour (Yu et al., Citation2015). Social identity theory and related notions of similarity attraction and assimilation integration are used to theorise discriminatory behaviour of actors in the destination country (Al Ariss et al., Citation2013; Almeida et al., Citation2015).

Labour market segmentation. SMs might be funnelled towards or barred from specific industries, occupations, and positions at the society level, resulting in systemic discrimination. For instance, Fullin (Citation2016) found, in a south European country, migrant men from developing countries working mainly in manufacturing, construction, retail, and catering and women segregated into housekeeping and elderly care activities. Migrants are often directed towards remote locations too, with less possibility to acquire and develop skills and lower professional statuses (Adhikari & Melia, Citation2015; Boese et al., Citation2013; Bornat et al., Citation2011). Such segregation is especially prominent in occupations in which co-ethnic members have established businesses (Shin & McGrath-Champ, Citation2013) or in occupations in which many ethnic group members are already employed (McGuire & Lozada, Citation2017).

Summary of the literature review

Research on employment and careers of SMs in the management and organisation field is a new stream as we found only one research article published before 2009. Through increasing scholarly interest over the past decade, knowledge of the dimensions and determinants of the employability and work transitions of SMs has become more comprehensive and established. The present review drew on prior research to analyse the individual and structural dimensions of SMs’ PE, the broadening strategies to cope with often an adverse labour market, and the different types of eventual work transition. The multilevel framework of a SM’s PE, presented in , summarises our literature review. elaborates the content of constructs shown in as they relate to the context of SMs’ employment at different levels of analysis.

The existing literature is concerned mainly with the question of ‘what’ defines perceived employability and work transition of SMs but is not well equipped for studying the question of ‘how’ or the relationships among perceived employability and other related constructs. In other words, the components of perceived employability in are mainly discussed in a static and isolated way and arrows explaining the causality and the process are less studied. Thus, future research on SMs’ perceived employment will require more process-oriented theorising (Langley, 1999; Mohr, 1982) to truly understand in what order, how and why events such as networking, education, cultural adaptation, job-seeking, qualified or over-qualified employment, career development occur over time and what are the differences across contexts (e.g. licenced vs. unlicenced occupations, in profession with a local skill shortage vs. in global professions, in countries with a humanitarian migration policy like Sweden vs. in countries with a point system migration system like Canada, Australia and UK). Furthermore, regarding the ‘what’ question about employability and work transition, the picture is not detailed in a balanced way. In particular, the transition condition needs further investigation. Studies on the effects of SM’s individual traits and dispositions to exercise their agency are scant. We mapped the little-explored area of individual dispositions. Motivation is discussed minimally, barring a few exceptions (e.g. Cerdin et al., Citation2014) and very few studies refer to the individual differences that we mapped out under adaptability and proactivity. This area needs special attention as post-corporate career perspectives such as the boundaryless and protean career promote career self-management and place the responsibility of staying employable onto the shoulders of career actors – including migrant workers.

Regarding the effects of organisational characteristics on the perceived employability of SMs, the demographic characteristics of the organisation were the most frequent variables in prior studies. A few studies also cited diversity strategy and diversity climate as being particularly influential. These studies are largely exploratory and need further theorization. From ethics, CSR or justice perspective (Guo et al., Citation2020), organisations should accept more responsibility of integrating migrants into the labour market by devising strategies and initiatives for creating of an inclusive culture.

Future research agenda

As noted, future research should focus on the question of ‘how’ PE is related to work transition of SMs. Such studies will enable us to understand how PE develops during post-migration period, and how broadening strategy leads to work transition. Understanding the patterns of post-migration events and the process of work transition (i.e. perceived employability as an appraisal of the intersection of individual and contextual factors may trigger certain broadening strategies, which, in turn, lead to different types of work transition) is key to advancing the literature on SMs’ employability and their career development in a host country.

Below, we propose future research on the process of the employment of SMs; specifically, how PE is construed and how PE leads to different types of work transitions through different mechanisms (different broadening strategies). Furthermore, areas for specifying the role of transition conditions as a moderator of the relationships are suggested.

The formation of perceived employability – agency–structure interaction

PE is a function of individual and contextual dimensions (Thijssen et al., Citation2008; Vanhercke et al., Citation2014). Analysing the literature, the individual and contextual dimensions of PE are presented in (right box). This reveals the ‘what’ constitute PE. Regarding the question of how PE is developed, it can be understood as an interaction of individual and contextual dimensions. High levels of PE correspond with high levels of individual dimensions (i.e. higher levels of human, social, and cultural capital and an established occupational identity) and favourable contextual dimensions (i.e. high labour demand, regulation and initiatives in place for attracting SMs and supporting newly arrived migrants, a low level of discriminatory behaviour, similar role expectations in the home and host country, and unregulated occupations). On the other hand, low levels of PE correspond with lower levels of individual components (i.e. low social and cultural capital, lack of language proficiency) and unfavourable structural components (i.e. low labour demand, no regulatory framework or initiative for supporting migrant integration, prevalence of discriminatory behaviour, dissimilar role expectations and high role requirements, and licensing process). A combination of ‘low levels of individual employability components and favourable structure components, or the combination of or high levels of individual employability components and unfavourable structural components’ may lead to medium levels of PE. Future research can further explore the nuanced variations in these individual and contextual interplays.

It is important to note that racism, as an institutional factor, can also influences migrants’ employability. Racism, sometimes blatant but often subtle, is widespread and persistent dynamic phenomenon relating to increasing intolerance outside the organisations (Ozturk & Berber, Citation2022). Further multi-level research should consider racism and explain the mechanisms of how it impacts organisational processes and decisions. To guide the future research, intersectionality as a main theoretical framework in the study of racism and discrimination can be utilised to understand the workplace inequalities better.

In addition, regarding how PE is developed, previous research has rightfully focused on both agency and structure; however, what is missing is that those often interact: they are not independent but highly intertwined.

As an example of, as discussed previously, a broadening strategy could be a logical response if SMs assess their chances of employment to be limited. While this could indeed be a logical response from the agency perspective, it only partially answered the question. Workers who perceive lower levels of employability have lower job search intensity, leading to lower chance of being employed (Koen et al., Citation2013). The perception of low employability and long-term unemployment might lead to losing confidence and internalization of low PE (Thozhur et al., Citation2007). Therefore, a longitudinal approach and process approach in SMs studies is advised.

Finally, the effect of societal challenges such as COVID-19 pandemic on migrant workers should be examined further. Migrant workers were especially vulnerable to unemployment and poor quality work (Butterick & Charlwood, Citation2021) during the global pandemic. Based on our PE framework, decreased demand in the labour market, quarantine and tighter mobility regulations that reduced opportunities for networking and vicarious learning as well as acquisition of social and cultural capital can lead to migranta’ lower levels of PE.

The mediation effect of broadening strategies

Researchers should explore which broadening strategy is adopted by SM based on their level of PE and how it affects the eventual employment and career attainments. Mechanisms through which PE leads to work transition should be further delineated. The investigation should start with the level of PE after migration, followed by implementation of broadening strategies leading to work transition. For instance, when contextual barriers hamper a highly qualified migrant with an established professional identity from entering the job market, the SM faces an identity conflict and most likely a medium level of PE. To resolve this conflict, the most common response is to maintain the identity, and invest in human capital to increase their employability while engaging in low-skilled survival work and seeking social support. Eventually, the SM might secure a job similar to those of their pre-migration period (proactive customisation transition). Otherwise, the identity conflict will remain and the SM might pursue other paths: (a) working in an overqualified position but within the border of the profession; (b) working as a cultural broker or engaging in necessity-driven entrepreneurship (reactive customisation transition); (c) relinquishing their occupational identity, which may lead to unemployment, repatriation or remigration (disidentification transition); or (d) exercising their agency in order to change the hostile institutional framework. This example shows that the work transition is a dynamic and complex process and encompasses interaction of the SM individual characteristics with the institutional, organisational, and professional factors and actors over time that need to be theorised further. In particular, the mediating effect of broadening strategy in the PE-work transition relationship needs further investigation.

Work transition – the moderation effect of transition conditions

A SM who is willing (motivated) and able (adaptable and proactive) will be likely to engage intensively in broadening strategies and develop the social and cultural capital required in the host country. As shown, organisations with a diverse customer base or with a diversity and inclusion programmes are more likely to provide SMs with better conditions equal employment opportunities and career development. For example, mentored internships and opportunities to work as a cultural broker have facilitated SMs’ entry into the labour market. Similarly, initiatives for integrating migrants into the labour market provide SMs with the language training and access to local job-seeking strategies that will increase the likelihood of employment. Therefore, transition conditions – the SM’s individual characteristics or the conditions of the context– can moderate the relationship between broadening strategies and consequent work transition.

Transition conditions as moderators should be further studied. At the individual level, the effect of personality traits and individual differences in relation to coping and stress are examples of important areas to be examined. At the organisational level, the effects of strategy, organisational culture, and HR processes on employment opportunities for SMs are black boxes that should be investigated. In particular, the effect of gatekeepers (e.g. hiring managers, policymakers, professional association representatives) framing SMs as ‘talents and sources of competitive advantage’ versus ‘people in need’ should be investigated. The common discourse around migrants is one in which migrants are depicted as people who lack proper education, language skills, and cultural capital and therefore should be supported by the host in a moral way (Ponzoni et al., Citation2017). It would be interesting to see how various logics embedded in institutional or professional level programmes and policies (e.g. benevolent discrimination through migrant employment quotas, assessing SMs based on competences related to their ethnic background, or blindness and assessing SMs solely on the required competences of a job) may affect SMs’ long-term employment prospects and career outcomes. The effect of the individual characteristics (e.g. the values and attitudes) of recruitment managers or organisations’ decision-makers is another interesting area to be considered.

Conclusion

Our review of 88 articles in management and organisation research on skilled migrants allows us to build a multilevel integrative framework. The framework allows us to identify patterns of SM’s employment and aggregate findings across countries, professions, and cultures. Our framework reveals major themes and relationships regarding SM’s perceived employability, broadening strategy, work transition and transition conditions. The framework attempts to outline the individual and structural dimensions of SMs’ appraisal of their levels of employability, strategies adopted by migrants or actors at the host country to increase the employability level and the resulting changes in employment status. As the existing literature concerns mainly the individual components of the constructs in the framework, future research may provide us with a better understanding by studying the organisational factors also the relationships among the constructs and by investigating SMs’ employment whole process. Furthermore, such research may contribute to our understanding of career decision-making of individuals in adverse conditions, such as those experiencing career shock (e.g. sudden unemployment due to digitalisation of the industry, skill obsolesce or pandemic), the employment of vulnerable or marginalised individuals (e.g. ethnic or local minorities), or mid-career individuals who cross borders of industries or professions where they face challenges related to identity and different institutions and norms.

Lastly, our review was limited to the organisation and management research fields. Incorporating theoretical and empirical insights offered by other research areas, such as economics, public policy, sociology, human geography and migration studies, would enhance the theoretical explanatory power of the present study’s framework.

Migrants are a diverse group and human experience and migratory behaviour are varied and dependent on a complex set of variables. However, it appears that discernible patterns of migration behaviour exist across time, individuals, and societies. Therefore, it is reasonable ‘to look for a level of a general theory which can make sense of these patterns and explain the processes by which they take shape’ (Bakewell, 2010, p. 1691). Our review is an initial step towards a general theory explaining patterns and processes shaping the perceived employability and work transitions of SMs, considering dynamics of factors at the individual, organisation, profession and institution levels. As international migration has become a challenging issue in many societies across the globe and exclusion and marginalisation of migrant workers in the labour market and organisations is still widespread, it is our hope that our review encourages other researchers to address this important topic by adopting more critically oriented studies that question taken-for-granted research approaches.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive remarks during the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

This study is a literature review and the articles included in the review are available in the Web of Science™ database at https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search. The data regarding coding of the articles are available in the Appendix.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adhikari, R., & Melia, K. M. (2015). The (mis)management of migrant nurses in the UK: A sociological study. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(3), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12141

- Al Ariss, A. (2010). Modes of engagement: Migration, self-initiated expatriation, and career development. Career Development International, 15(4), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431011066231

- Al Ariss, A., & Syed, J. (2011). Capital mobilization of skilled migrants: A relational perspective. British Journal of Management, 22(2), 286–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00734.x

- Al Ariss, A., Vassilopoulou, J., Özbilgin, M. F., & Game, A. (2013). Understanding career experiences of skilled minority ethnic workers in France and Germany. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(6), 1236–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.709190

- Alfarhan, U. F., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2018). A "catch-22": Self-inflicted failure of GCC nationalization policies. International Journal of Manpower, 39(4), 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0174

- Allmen, P. v., Leeds, M., & Malakorn, J. (2015). Victims or beneficiaries? Wage Premia and National Origin in the National Hockey League. Journal of Sport Management, 29(6), 633–641. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2014-0179

- Almeida, S., & Fernando, M. (2017). Making the cut: Occupation-specific factors influencing employers in their recruitment and selection of immigrant professionals in the information technology and accounting occupations in regional Australia. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(6), 880–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1143861

- Almeida, S., Fernando, M., Hannif, Z., & Dharmage, S. C. (2015). Fitting the mould: The role of employer perceptions in immigrant recruitment decision-making. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(22), 2811–2832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.1003087

- Almeida, S., Fernando, M., & Sheridan, A. (2012). Revealing the screening: Organisational factors influencing the recruitment of immigrant professionals. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(9), 1950–1965. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.616527

- Bahn, S. (2015). Managing the well-being of temporary skilled migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(16), 2102–2120. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.971849

- Banerjee, R., & Phan, M. (2014). Licensing requirements and occupational mobility among highly skilled new immigrants in Canada. Relations Industrielles, 69(2), 290–315. https://doi.org/10.7202/1025030ar

- Baruch, Y., Altman, Y., & Tung, R. L. (2016). Career mobility in a global era: Advances in managing expatriation and repatriation. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 841–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1162013

- Baruch, Y., Dickmann, M., Altman, Y., & Bournois, F. (2013). Exploring international work: Types and dimensions of global careers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(12), 2369–2393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.781435

- Baxter-Reid, H. (2016). Buying into the ‘good worker’ rhetoric or being as good as they need to be? The effort bargaining process of new migrant workers. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12111

- Bell, M. P., Kwesiga, E. N., & Berry, D. P. (2010). Immigrants the new "invisible men and women" in diversity research. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011019375

- Berry, J. W. (1990). Understanding individuals moving between cultures. Applied Cross-Cultural Psychology, 14(1), 232–253.

- Berthou, S. K. G., & Buch, A. (2018). Perfect match? The practice ecology of a labor market initiative for refugees. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 8, 27–46. https://doi.org/10.18291/njwls.v8iS4.111158