Abstract

This article investigates how meso-level actors (MeLAs) contribute to HR practice transfer in diffusion and adaptation processes, drawing on the System-Society-Dominance-Corporate Effects (SSDC) framework to interpret the role of MeLAs in the transfer of the Japanese management model to the Indonesian automotive industry. We focus on two issues: i) the way Japanese MeLAs’ training regimes in Japan affect the diffusion of the model and ii) the coordinated Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs strategy in seeking procedural influence through knowledge-sharing and in facilitating transfer activities over how the Japanese model is adapted in Indonesia. Our research adds to our limited understanding of the significance of MeLAs in processes of diffusion-adaptation in emerging market economies characterized by weak regulatory regimes and asymmetric socioeconomic power relations. Drawing on interviews with 75 key informants across Japan and Indonesia, we explore the significance of MeLAs from corporate and labor spheres alongside those of non-corporate MeLAs. Theoretically, this study extends the SSDC framework by highlighting MeLAs’ influence in both diffusing conceptions of dominant management ‘best practice’ (dominance effects) and their role – and that of dominance effects – in shaping societal effects that inform how the model is adapted. We theorize the complex processes through which the effects identified in the SSDC framework are experienced by local actors, showing that they are neither monolithic nor mechanical in nature and thereby elaborating the inter-relationship in how dominance effects inform societal effects.

Introduction

In this article, we argue that intermediary organizations such as employer associations, trade union bodies and non-governmental organizations, which we collectively term meso-level actors (MeLAs), affect the transfer of multinational management practices amongst local firms in emerging market economies (EMEs) in ways that are not yet fully recognized in the literature. Differentiating between types of actors and institutional factors relevant to the roles MeLAs play, we show that MeLAs are influential in the diffusion and adaptation processes. While there is a considerable body of research addressing the processes of diffusion and negotiation through which both national institutions and local actors engage in the adoption, hybridization, transplantation or even rejection of foreign management practices within subsidiary operations (e.g. Chiang et al., Citation2017; Liker et al., Citation1999; Pudelko & Harzing, Citation2007), the significance of meso-institutional factors and actors has only recently received concerted attention despite their impact on various aspects of corporate decision making (e.g. Budhwar et al., Citation2016; Monaghan et al., Citation2020). This meso level of analysis, especially the roles of MeLAs in the diffusion of cross-border HRM practices, has not been adequately documented. Therefore, this paper responds to calls from various scholars for a closer examination of the full range of sociopolitical economic and industrial relations actors involved in these processes at the meso level (Almond, Citation2011; Sheehan & Sparrow, Citation2012; Soehardjojo et al., Citation2022; Vincent et al., Citation2020). The following research question is addressed: How do MeLAs contribute to the diffusion-adaptation mechanisms in the transfer of management practices by dominant MNCs operating in EMEs?

To advance our understanding of MeLAs in HR diffusion-adaptation processes, this paper presents a study of the transfer of the Japanese HRM model (so-called ‘Japanization’) to Indonesia, an EME country characterized by weak regulatory regimes (Bennington & Habir, Citation2003; Do et al., Citation2020). We underscore the institutionalized key enabler roles and strategies of MeLAs in navigating institutional and societal constraints (Budhwar et al., 2016). We also show how MeLAs engage in bilateral socioeconomic cooperation and are directly involved in the MNCs’ attempts to define Japanese human resource management and employment relations (HRM-ER) as ‘best practice’ as they seek to reproduce the Japanese management system in Indonesia (JMS) (e.g. Liker et al., Citation1999; Rowley et al., Citation2017). In theorizing these insights, we draw on the System, Society, Dominance and Corporate Effects (SSDC) framework (i.e. Delbridge et al., Citation2011; Smith & Meiksins, Citation1995).

Our findings indicate the significant role of MeLAs in diffusion processes, particularly through training regimes that take place in Japan influencing its adoption at the workplace level through society-in-dominance effects (Smith & Meiksins, Citation1995). Furthermore, MeLAs are essential to the multi-level negotiation, networking and capacity building, through adaptation processes take place within Indonesia. MeLAs thereby play a role in moderating societal effects on practice transfer in the workplace. This paper makes three contributions. First, in conceptual and empirical terms we elaborate understanding of the meso-level actors that influence processes of practice transfer. We provide new insights into the range of different MeLAs and the dynamic roles that they play in the diffusion-adaptation of dominant HRM-ER ‘best practices’. We conceptualize and differentiate between two types of MeLAs: corporate MeLAs and non-corporate MeLAs. The first type encompasses ‘corporate’ actors organized collectively, including business groups, corporate stakeholders, employee and employer associations. The second type is comprised of ‘non-corporate’ actors operating at the meso level, in our study quasi-governmental and not-for-profit organizations. Second, we elaborate discernible differences (as well as complementarities) in how the various MeLAs affect both diffusion and adaptation. Home country MeLAs exercise influence through both extending dominance and moderating the constraints of societal effects (in diffusion), whereas host country MeLAs are primarily involved in (re-)producing societal effects and supporting the business environment in reproducing the localized dominant model (in adaptation). However, Japanese MeLAs also exercise influence on adaptation processes in Indonesia. In particular, the Japanese collective corporate MeLAs’ advocacy, intelligence sharing and facilitating transfer activities exert procedural influence (that is, influence over the ways things are done rather than exercising direct control on actors and outcomes) in shaping the Indonesian business systems (both macro and micro). This moderating effort facilitates transfer in broad terms while the Japanese non-corporate MeLAs’ focus on training and development activity that is particularly important in overcoming the lack of human capital investment which otherwise limits practice diffusion-adaptation in local institutions. Third, the paper extends the SSDC framework through a detailed examination of the interwoven processes of diffusion-adaptation and the central roles played by MeLAs in the processes through which dominance and societal effects are constituted.

This is the first study that has centered on the role of such actors in the institutional isomorphism processes of diffusion that was initially theorized in the SSDC framework. This has allowed us to understand and further theorize these dominance and societal effects in a more complex way, showing that such effects are neither monolithic nor mechanical in their impacts. These theoretical insights echo work in mainstream institutional theory that has begun to disentangle institutional logics (Durand & Thornton, Citation2018) and examine how actors inhabit and participate in complex institutional settings (Delbridge & Edwards, Citation2013; Creed et al., Citation2020). The article proceeds with an overview of the SSDC framework and its value in understanding practice diffusion in EMEs before introducing the empirical evidence of management practices transfer in Indonesia. Implications and conclusions are then developed and discussed.

SSDC in the analysis of management practice transfer processes in EMEs

Institutional isomorphic effects in explaining cross-national organization and the transfer of management practices were first theorized by Smith and Meiksins (Citation1995). Their System-Society-Dominance framework identified how particular nations were home to internationally ‘dominant’ approaches that diffused through institutional processes of adoption at particular points in history, such as the US and Fordism during the early stages of global industrialization (Elger & Smith, Citation2005). Smith and Meiksins (Citation1995, p. 245) cite Japanese work organization as constituting ‘universal rational prescriptions for regulating work’ and diffusing through Japanese manufacturers’ dominant status during the 1990s. Their System-Society-Dominance approach has informed studies of the transfer of Japanese models to other advanced economies (Pudelko & Harzing, Citation2007) and the diffusion of HR practices more widely (Tyskbo, Citation2021). Their theoretical framework also embraced insights on the underpinning nature and influence of capitalist political economy and from the societal effects school (Maurice et al., Citation1980) on how national legacies and institutional patterns impact practices at the workplace level (see also work on national business systems, e.g. Edwards & Kuruvilla, Citation2005; Hall & Soskice, Citation2001). This provided a neo-contingency advance in cross-national organizational theory that moved beyond a polarized divergence-convergence debate (McSweeney et al., Citation2008). In order to understand strategic choice and how corporate influences were experienced at the workplace level, Delbridge et al. (Citation2011) extended the framework to System, Society, Dominance, Corporate effects (SSDC). Subsequent research has considered these effects on corporate Japan and capitalist employment relations under Japanese HRM (Aoki et al., Citation2014) and their implications for labor-management partnerships under neo-liberal work regimes (Makhmadshoev & Laaser, Citation2021). Recently, work inspired by SSDC has underscored the importance of meso-level institutional features (Morris et al., Citation2018; Soehardjojo et al., Citation2022). Theorizing diffusion and adaptation in practice transfer through the SSDC framework ‘provides the basis for multi-level, multi-actor analysis as the influence of dominant institutional norms and conventions promoted by multiple actors in the organizational field – including regulatory organizations, trade unions, consultancies, the business press, education and training organizations and charities, as well as MNEs – may be observed at global, national, sub-national, and/or industry sector levels’ (Delbridge et al., Citation2011: 497). To date, however, very few studies have explored the roles of non-corporate actors, particularly at the meso-institutional levels.

Applying the SSDC framework to the transfer of the Japanese model to EME context of Indonesia

The SSDC approach provides a framing of the mechanisms involved in transferring dominant management practice, nesting societal and organizational level processes within a system-wide conception of capitalism (Elger & Smith, Citation2005). The current study broadens previous research by considering SSDC effects across macro- (national and international), meso- and micro-levels (organizational and workplace) in evaluating processes of practice diffusion and adaptation where dominance effects interact with the host country business environment and labor market institutions. This speaks directly to recent calls for multilevel analyses which situate management practices in their sociopolitical economic contexts (i.e. Malik et al., Citation2021; Piekkari et al., Citation2022; Vincent el., 2020) and disentangle the SSDC effects (Edwards et al., Citation2013). Moreover, this is the first study to our knowledge that centers specifically on MeLAs and their contribution to processes of diffusion and adaptation in the transfer of a universal model of management practices into an EME. As we will see, a focus on MeLAs’ institutionalized coordination offers new insights into these processes, particularly at the meso-level (Almond, Citation2011; Weinstein et al., Citation1995). Specifically, the focus on meso-level activity involved beyond the firms themselves has provided new insights into the complex processes through which the effects identified in the SSDC framework are constituted and experienced.

Applying the SSDC framework calls for a careful evaluation of institutional contexts. First one must consider the qualities of capitalism as the political-economic system within which contemporary business organizations are embedded. System effects arise from the dominant social relations within a political economic system such as capitalism; these are supranational features ‘regardless of the country context within which those social relations are located’ (Elger & Smith, Citation2005: 61).

While there are important features that are inherent to capitalism, there are widely recognized variations at national levels. For instance, while Japan is generally considered to be a coordinated market economy, coordination by Indonesia’s government and institutions is much lower. Ford and Sirait (Citation2016) portray Indonesia as a hierarchical market economy (HME) similar to Latin America’s developing economies with a large informal economy and a formal economy dominated by domestic conglomerates. These domestic business conglomerates are active in reconstructing and protecting national business systems and management practices within the host country (Dieleman & Sachs, Citation2008). These are theorized as society effects which operate through the institutions, norms and customs that shape specific national business systems; East Asian developmental states have been keen on fostering such national specificities (Witt & Redding, Citation2013).

Albeit eroded at the global level through a combination of Japan’s economic stagnation and China’s rising influence and economic scale, the dominance effect of Japanese practices that was highlighted by Smith and Meiksins (Citation1995) remains particularly relevant in East Asian countries. Endo et al. (Citation2015) pointed to the dominance of the Japanese HRM model amid both Asian and global financial recessions and the relevance of ‘best practice’ transferred outside Japan. As Smith et al. (Citation2008: 21) identify, dominance effects speak both to ‘the recognition that economies do not compete as equals but in ‘hierarchical ensembles’, in which ‘leadership’ circulates on the basis of economic performance but also through subsystem innovations and fads that animate management agents to move with the spirit of the age, and particular management concepts to move in and out of fashion’.

The corporate effects resulting from MNC headquarters and corporate management control are seen in their influence on the local workplaces of subsidiaries; however, studies of subsidiaries repeatedly show how local conditions, and the agency of workplace actors result in considerable variation from the espoused corporate model.

The SSDC framework has been applied to interpret patterns of management practices and evaluate evidence of diffusion mechanism to institutionalized ‘global best practices’ (Pudelko & Harzing, Citation2007; Reiche et al., Citation2019). However, concerns have been raised that the complexities of the processes and the varying impacts of the different effects experienced by local actors have been downplayed or ignored (Edwards et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, to date, the application of SSDC has been almost exclusively focused on MNCs and their local networks. Our research addresses both of these issues with its focus on the roles of MeLAs in diffusion-adaptation processes and an analysis of the dominance and societal effects that are both experienced and produced through these processes.

Setting the scene: Japanese MNCs and MeLAs in Indonesia

This paper focuses primarily on theorizing the influence of Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs through diffusion-adaptation processes in the context of late industrialized country: Indonesia. Indonesia is the largest recipient of Japanese ODA (economic cooperation) across the 11 ASEAN countries since WWII and the only ASEAN state admitted to the G20. On-going multilateral ODA cooperation and international advocacy groups have led Indonesia to ratify 19 ILOs to improve working conditions, promote labor market institutions and democratic industrial relations (Ford, Citation2000).

The activities of these Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs are institutionally coordinated and well resourced, promoting socioeconomic cooperation and HR development through bilateral relations in periphery, global manufacturing hub nations each with specific national systems and diverse industrial actors at government and organizational levels (Gajewska, Citation2013; Williamson, Citation1994). Japan’s integrated approach of advocacy, policy development, industrial and operational strategies promote Japanese practices, providing technical and management training, constructing transfer networks and supporting institutional settings that address the lack of HR development and investment and diverse demographics (i.e. educational background, skills and in-house organizational training capabilities). The primary objective is to improve local HR development and maximize regional economy competitiveness. While there are patterns to Japanese MeLAs’ activities globally, there are specific characteristics in each host nation and the challenge of diffusion-adaptation of JMSs has intensified as Indonesia’s economy has developed. It has led to the call for specific investment opportunities in the local HR in overcoming the regional ASEAN economic competition and the inflow of aggressive Chinese investment (Mamman & Somantri, Citation2014). Japanese MeLAs have increasingly sought procedural influence—rather than direct control—to respond to institutional and other constraints on their actions.

In the case of the Indonesian automotive sector, the development of HR practices is high, with local management striving to safeguard itself from the imported foreign HRM-ER practices (Doner et al., Citation2021). This is particularly true of Astra, south-east Asia’s largest independent automotive group operates in Indonesia (Sato, 1996). Institutional constraints are also imposed by government regulations, but inefficiently, particularly for those professional workers with degree level qualifications and in the skills development of workers (i.e. lack of regulator enforcement, clarifications and chaotic labor regulations) (Bennington & Habir, Citation2003). Thus, the Indonesian labor market is characterized by weak regulatory regimes and challenges with respect to training and securing the consent and collaboration of local industrial actors (Burton et al., Citation2003). Accordingly, Indonesian business systems are somewhat open, with weak labor market institutions and inefficient regulation regimes, and the imposed constraints are relatively manageable for Japanese MeLAs (e.g. Ford and Pepinsky, Citation2014). As examined below, their strategic influence includes coalition building with the key Indonesian MeLAs whose purpose is to modernize Indonesian’s HRM-ER practices and reconstruct the diffusion-adaptation segments of JMSs at the organizational level. In so doing, the narrative of the promotion and protection of Indonesian labor market institutions and business systems is perpetuated. These ‘diffusion enablers’ include the national chamber of commerce, KADIN, and the employer association APINDO, which is the only officially recognized employers’ organization in Indonesia involved in HRM-ER development and tripartite industrial relations. provides an overview of the main MeLAs and maps out their diffusion-adaptation roles.

Table 1. Overview of the meso-level actors and their roles in diffusion and adaptation.

The Japanese management model underscores the importance of employee participation, internal skills formation and training systems, and relatively pluralist or ‘high-trust’ management–labor relations (Endo et al., Citation2015; Iwashita, Citation2021). By contrast, Indonesian managers have traditionally followed a centralized and unitarist approach, capitalized learning resources and the investment of certain elite business groups, reflecting the belief that local employees and unions lack the necessary organizational understanding, commitment and skills to be treated as equal partners (Caraway & Ford, Citation2017). ‘Japanese’ and ‘Indonesian’ HRM-ER characteristics are summarized at a simplified and generalized level in .

Table 2. Japanese and Indonesian HRM-ER characteristics.

Method

A case-based approach was adopted to examine the roles of MeLAs in the transfer of the Japanese model as part of a larger study. The focus is on a nested set of cases that construct the transfer processes and the analysis probes in detail the diffusion-adaptation impact across the identified Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs, i.e. involvement, means and resources. To investigate the diffusion-adaptation processes, two phases of study were conducted: one in October 2014 at the Japanese automotive manufacturing firms and workplace organizations in Karawang Industrial International Park, Indonesia, and another phase in October 2016 in Nagoya and Tokyo, Japan. When the coordinated role of Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs became clear, an extensive third phase of fieldwork was conducted between April and November 2019 in Japan and Indonesia. explains the three phases of data collection design, the full dataset, research program and data sources. The primary data used in this paper are 75 interviews with MeLAs. The interview data collected in Japanese MNCs and subsidiaries were used to understand the training, trainees’ experience and the application of Japanese HRM-ER in workplaces.

Table 3. Phases of data collection.

Primary data were complemented by and cross-referenced with secondary data, including reports and archival material. We corroborated our analysis with secondary data of organization/firm reports available for public consumption as well as reports that are inaccessible to the general public and were provided by certain research participants. Furthermore, JICA and AOTS directors prepared their own documents based on a questionnaire prior to in-person discussion (which included presentations from the organizations with two to five members participating). We analyzed these secondary sources and vignettes carefully and corroborated our findings.

Research was conducted in seven key meso-level MeLAs (see ). Interviewees had been directly involved in transferring the Japanese management model (working with Japanese subsidiaries, local firms and local government offices). Research participants from the Indonesian MeLAs had experienced training in Japan, local HRM systems, ER policy development, and union organization in the automotive sector. The interviews were carried out in a combination of English and the native language of individual interviewees, namely, Japanese and Bahasa Indonesian (the lead author is a fluent speaker of Japanese, Bahasa, Javanese and English) which facilitated accuracy and consistency in the translation into English for coding.

Data analysis

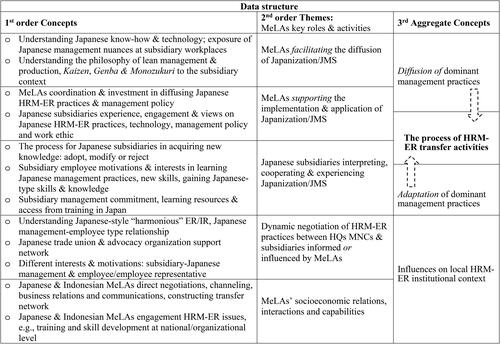

A three-stage thematic coding analysis was conducted, building from first-order concepts derived directly from the interview transcripts. Through subsequent stages, the analysis was systematically refined to develop a conceptual picture and articulate insights at higher levels of aggregation (see ). An iterative process of data analysis was undertaken involving three consecutive phases of data collection and the development of theoretical constructs regarding organizations and actors, which took into account existing literature on JMSs. Data analysis continued until theoretical saturation was reached (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007) in order to gain a fuller understanding of the key roles and activities of each of the MeLAs (i.e. HRM-ER transfer activities: facilitating and supporting) and Japanese subsidiaries implementing Japanization/JMS at the local workplace setting. These inductive processes identify three primary areas for consideration:

the diffusion of Japanese influence and practices;

the adaptation of these management practices in Indonesia;

the wider influence of meso-level actors on diffusion and adaptation activities and their local institutional context.

Therefore, our presentation of the data proceeds through a detailed consideration of the activities of MeLAs related to diffusion-adaptation processes in both Japan (i.e. Indonesian trainees gaining understanding, developing skills and competency) and Indonesia (i.e. Japanese subsidiaries applying, modifying and adapting).

Our inductive theory-building approach begins with contextual description of empirical data on each phase of data collection, continuing with data analyses, and then the diffuser-adapter relationship that is replicated across MeLAs’ operations. The findings are presented in ways that seek to integrate the empirical evidence with the theoretical base (Welch et al., Citation2011) although we also offer a small sample of direct quotations throughout the paper to exemplify the nature of our data and give voice to key respondents. provides further examples of quotations that illustrate aspects of diffusion-adaptation and context.

Table 4. Indicative quotations.

Research findings

In this section, we scrutinize MeLA roles in the two key processes identified in the data analysis: diffusion and adaptation. In this study, diffusion refers to activities influencing the nature and understanding of the practices constituting the dominant model and how that model is transferred to the host country. Adaptation involves activities affecting how the Japanese model is adopted and modified within the host country business environment. Our data allow us to explore the inter-relationships that exist across the effects of the SSDC framework: diffusion activity is primarily informed by and shapes dominance effects while adaptation is influenced by societal effects which in turn are shaped by dominance effects as experienced by local actors and institutions.

The objective and implications of MeLA diffusion activities in their home business environment

Our research identifies a range of activities through which Japanese MeLAs coordinate with other actors engaged in diffusion. These activities center on the training and acculturation in Japan of host nation government employees/bureaucrats, managers, employees and trade unionists. AOTS is a prime example of a non-corporate Japanese MeLA whose roles include disseminating and shaping the understanding of JMSs, i.e. philosophy, practice and policy.

Initially established in 1959 by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) to support the training activities of Japanese firms investing overseas (Williamson, Citation1994), AOTS Japan has served as the leading meso-level player in the diffusion of Japanese management practices for many years. Of direct relevance to our study is its role in management and technical training for Japanese subsidiaries operating in Indonesia. This involvement began in the 1960s when internationalizing Japanese firms did not know ‘how to systematically train people who had no knowledge of the Japanese language, culture, customs and so forth’ (AOTS Director, 2019). AOTS increases MNCs’ capacity to meet the challenges in managing affiliates through its training, particularly the induction of host country employees into the Japanese model and mindset. For example, the chief financial officer of Toyota Motor Manufacturing Indonesia (TMMIN) commented on the importance of its engagement in the AOTS’ training program:

[W]e cooperate with AOTS. We invest in our training fund because we think people development is very important. We secure some funding for specialists, a section head, development training, etc. and dispatch 30-40 young workers annually to Japan. Before departure, trainees receive training in the Japanese language [i.e. terminology related to their jobs] and culture [organization and society]. (AOTS alumni/TMMIN HR director, 2019).

AOTS collects and analyzes the experiences of its trainees and alumni in order to improve the training schemes. The findings are then fed back to Japanese enterprises and training partners to keep training relevant. The training centers serve as knowledge hubs in Japan and contribute to the shaping, understanding and diffusion of the Japanese ‘best practice’ within the country (including social exchange, learning how to work both overseas and side-by-side with non-Japanese workers) for the benefit of Japanese organizations. AOTS’ participation in diffusion activity requires considerable investment and institutionalized arrangements with other MeLAs outside Japan/transnationally. The training conducted in Japan includes coordination with non-corporate MeLAs (e.g. JICA) and corporate MeLAs (e.g. Keidanren, JILAF and APINDO) as well as individual Japanese organizations (multinationals, large and small medium enterprises and government agencies). The heart of the training focuses on ‘the integration of Japanese human resources (HR) practices and advanced technologies as a driving force for maintaining higher productivity’ (AOTS Director and Management, 2019). This management and technical training encompasses basic aspects of Japanese philosophy (hard work, discipline and professionalism) and industrial strategy—that is, aspects related to HR development, human capital investment and capacity building. While from the Indonesian perspective, robotic technology is seen as replacing humans and devaluing workers’ skills, the Japanese promote integrated systems of human-technology-machinery in achieving productivity, promoting safety and competitiveness with the human being as the key driver. Conducted at Japanese manufacturing sites in processes similar to on-the-job training, the training is delivered by Japanese kaizen experts familiar with what AOTS interviewees referred to as:

the ‘art of diffusion: [the training] focuses on changing the trainees’ mind-set/mentality [as workers bear responsibilities to do their best both at the workplace and in their community]’.

A second key MeLA player in the diffusion process is JILAF which is supported by the Japanese union RENGO and cooperates with government agencies and other (inter)national labor advocacy organizations (Williamson, Citation1994)—including the UN ILO, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) based in Germany, and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)—to encourage the proliferation of Japanese ‘democratic’ industrial and ‘harmonious’ employment relations practices (Gajewska, Citation2013). JILAF does not have the power to interfere with management policy. It promotes the non-militant labor movement from within. It is the prominent diffuser of Japanese-style democratic labor relations systems in developing countries, including countries that have a bilateral relationship with Japan. Diffusion is achieved primarily through the following training schemes, all of which are held in Japan and involve 120 leaders annually (JILAF Report, 2018):

the Invitation Program for union leaders/stewards to learn about the Japanese trade union movement, especially concerning the benefits of ‘stable’ [non-radical strategy] employment relations;

the Field Project on knowledge exchange and dialogue administered by RENGO and individual trade unions;

HRD training for junior trade union leaders to gain Japanese-style work organization and leadership skills.

It should be noted that Keidanren (the employers’ association) is an active participant in these labor relations training schemes. Provided free, the training is open to any employee association or overseas union, including non-federated ones. Moreover, holding the training in Japan enables trainees to have open discussions directly with RENGO, Keidanren and Japanese management representatives. By so doing, this institutionalized tripartite ER training arrangement (JILAF, RENGO and management) showcases the advancement of the Japanese-style labor relations system to foreign labor union trainees. According to one JILAF representative (2019), cooperation is possible because the Japan-Indonesia bilateral agreement and Indonesia law are relatively open to the notion of unions forming a confederation (in comparison to other countries such as Malaysia and Thailand) (Bamber et al., Citation2021). The laws have also allowed JILAF to support the Indonesian confederated union since 2003 (Bennington & Habir, Citation2003). As Gajewska (Citation2013) has pointed out, through the ASEAN-Japan Economic Partnership Agreements (ASEAN-Japan EPA), Japan has negotiated agreements on labor standards and workers’ rights with a certain number of ASEAN member states (namely Singapore, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam). This agreement was recently renewed and further intensified with the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) 2022. Such agreements pave the way for Japanese MeLAs, in particular JILAF, to gain influence; they facilitate involvement in relevant local ER issues and promote employee participation in Japanese-style labor relations. However, under Indonesian regulations, JILAF may not engage directly in either negotiations or labor disputes. Therefore, while JILAF does have communication with Indonesian union leaders/stewards through its former trainees and affiliate unions, its primary impact is through procedural influence over the way things are done. The aim of the JILAF-union organization training scheme is to promote solidarity, advocacy and advancement in a form consistent with and shaped by the specific Japanese model of labor-management relations that developed in the post-WWI institutional settlement (Williamson, Citation1994). Thus, while AOTS supports a universal model of management practice, JILAF advocates a reciprocal form of Japanese-style labor relations centered on democratic employee participation and association; both are advanced as part of the ‘Japanese economic miracle’.

JILAF has the authority to design, deliver and coordinate its training schemes in Japan. The Invitation Program and Field Projects exemplify the coordinated and ‘harmonious’ relationship between employment relations actors—a relationship explicit in the Japanese model. This was further substantiated by TMMIN, JJC and APINDO representatives. The two schemes demonstrate how the training content can be adapted to address the specificities of the Indonesian setting. For instance, the approach extends beyond the ‘company unionism’ of the Japanese model (Aoki et al., Citation2014). It includes auto parts workplaces such as the Denso Japan-Indonesia joint venture (the largest auto parts manufacturer in Indonesia with over 5500 employees in three plants in West Java) that have more than one trade union/employee association with different approaches in representing workers’ voice, advocacy strategy and management relations. The JILAF training keeps the messages consistent. At the heart of the training on management-labor communication is the emphasis on the avoidance of militant/radical approaches and conflict (e.g. strikes and lockdowns) and on trainees’ participation in conciliation with management.

JILAF’s influence extends beyond diffusion through its training schemes as its advocacy role helps to shape the democratic political economy context of employment-relations subject to local labor policy and international trade union involvement. Thus, as we report in the following section, JILAF also has an impact on the processes of adaptation and the context of those processes in Indonesia.

Keidanren is another key Japanese collective corporate MeLA with influence on both diffusion processes and the Indonesian context within which policy development and practice adaptation take place. As Japan’s most powerful business group, Keidanren negotiates with overseas governments, chambers of commerce and other business associations on a global scale (Sasada, Citation2019). However, Keidanren’s influence is also significant in shaping policy and conceptions of the Japanese model in Japan. Most notably, Keidanren negotiates/communicates directly with the Japanese government to promote its policy proposals on a range of relevant business and political economy issues. It has drafted blueprint policy and action plans to support comprehensive and long-term development strategies for Japan at home and abroad. In our case, at the corporate level, Keidanren depends on direct links to Japanese headquarters (HQs), management and directors in Indonesia. Its influence on the diffusion of management practices is more extensive and direct in Japan than in individual host countries. As the Keidanren Labor Policy Committee representative notes (2019):

Keidanren does not support Asian countries directly as does NICC (Nikkeiren International Cooperation Center). However, Keidanren does have a regional committee comprised of Asian countries, such as China, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar, to exchange information and support activities.

In summation, the activities of Japanese MeLAs have a substantial impact on the development and understanding of the Japanese management systems model and hence the dominance effects of this model through two mechanisms: influence on key Japanese actors in the shaping of the model and MeLAs’ role in training regimes that exert influence on and build capability in participants from Indonesian government agencies/bureaucrats, managers, employees and trade unionists involved in adopting the model. However, how the Japanese model is actually enacted is subject to societal effects that are also influenced by both Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs. These relationships are at the core of adaptation processes.

The systematic coordination of MeLAs on adaptation processes in the host country

Our interest here is specifically in how MeLAs are involved in and influence processes of adaptation of the Japanese model into the Indonesian context, including their contribution to the societal effects experienced by local actors. At the macro-level, Japanese MeLAs build coalitions with local government institutions and agencies in seeking to influence national Indonesian business policy and infrastructure. Along with lobbying through these advocacy networks, at the micro-level, Japanese MeLAs are involved in the training of large numbers of staff who are active throughout Indonesian organizations. Thus, the influence of Japanese MeLAs in Indonesia is primarily indirect and through procedural means.

Japanese MeLAs’ approach in Indonesia is exemplified by JICA. As indicated in , JICA is a non-corporate MeLA largely financed by Japanese ODA (Official Development Agency) which is important in the promotion of economic cooperation, especially in both the design and delivery of training and in advocating policy development in the recipient country. As the largest Japanese socioeconomic actor engaged in economic cooperation and HR in Indonesia, JICA has spearheaded Japan’s overseas projects there since 1954. Through partnerships with federal, state and municipal governments, JICA is chiefly engaged in HRD projects. In disseminating the Japanese model through such training schemes, it works with various actors at macro (international ODAs and national government), meso (regional and not-for-profit organizations), and micro levels (individual local leaders and bureaucrats). This activity is significant as the collaborations with multiple actors across multiple levels enable JICA to identify challenges, design training appropriate to local issues, directly communicate and negotiate with governments, and strategically operationalize processes suitable for the local government institutional context. One such example is the way JICA’s government-to-government (G2G) HRD activities in Indonesia are complementary to those of AOTS whose management training is applied at the organizational level. Indeed, our findings indicate that AOTS training in Japan is coordinated with JICA’s activities that are relevant to the specific host country business environment. Nevertheless, JICA and AOTS deploy different experts and JICA targets local government agencies and bureaucrats focused on infrastructure and policy, exceeding the manufacturing-orientated training offered by AOTS.

However, AOTS’s impact in Indonesia is far greater than that achieved directly through its business management and technical training programs. Former participants in these programs constitute a large and influential government and business practitioner network that promotes the Japanese-style industrial development model. Such systematic influence helps to shape local processes of adaptation of JMSs. AOTS invests in alumni associations, constructs alumni networks, and utilizes these networks to refine and disseminate the applicability of Japanese ‘best practice’. AOTS’ overseas offices focus on trainee recruitment and support for AOTS alumni in adapting Japanese management practices and skills locally. AOTS is seen by its director as an exemplar of ‘how government, business practitioner and private enterprise can partner to effectively diffuse Japanese knowledge, skills and expertise to facilitate the industrialization of developing countries’ (AOTS, 2016). The outreach of the organization is on a global scale; it currently operates in 43 countries with 72 alumni societies engaged in the diffusion network and economic and industrial development of their home countries. According to the 2018 AOTS Report, there have been 136,000 AOTS trainees worldwide. The influence of this network is not just due to its scale. The AOTS report indicates that many alumni are now working at senior levels both within their own organizations and also in important government positions, including ministerial ones. Additionally, AOTS alumni can be found in other MeLA organizations, including as executive board members and committee members across South and Southeast Asian countries. In Indonesia, AOTS alumni have served on the board of directors of APINDO, BKPN, KADIN and other elite business associations with political ties, such as Astra International business group, the largest employer and pioneer of management modernization in Indonesia (Ford, Citation2014). Their presence in key positions deepens AOTS’ influence on the Indonesian context and informs processes of adaptation well beyond that exercised through the current trainees themselves. Thus the influence is broader than that felt within individual organizations and workplaces. While it is difficult to be specific about the precise impact of this wider network of influence, AOTS respondents were explicit in recognizing that the strategy of the organization is to ‘standardize’ and ‘localize JMSs’ to fit in with local needs and practices through the adaptation processes in which AOTS alumni themselves are key actors. Thereby, AOTS alumni are prominent in these diffusion-adaptation processes working within, and to overcome, local institutional and societal constraints.

This network of influence is the outcome of sophisticated long-term planning. AOTS’ initial training supports their alumni’s ability to succeed in their own organization, whether these are Japanese-owned, local independents or governmental organizations. AOTS’ records indicate that its alumni globally, in particular where Japan has dominant and/or strong economic relations (e.g. East Africa, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, and South America), go on to secure more senior, better-paid jobs. There is an enduring mutuality between trainees and AOTS, and the importance of alumni commitment to the network was emphasized by the AOTS director and management members (group interview, 2016) when they remark that

‘selfless devotion to the creation of an AOTS Alumni Society can be regarded as an extension of the returned-trainees’ higher social awareness and responsibility that were nurtured during their training in Japan’.

The alumni are expected to take wider societal responsibility and exercise societal influence: ‘The AOTS Alumni Society rehabilitates [modernizes] their society’ (AOTS Management, 2016).

JICA also uses its influence on local governments to promote Japanese interests in the local economy and society more broadly. Most notably, JICA experts are dispatched to BPKM, the Investment Coordinating Board of the Republic of Indonesia which was established in 1973 to promote foreign direct investment in Indonesia. For instance, there has been a Japan Desk investment policy advisor at BPKM since 1987. Such influence is deepened and facilitated as JICA routinely negotiates with local MeLAs and government agencies whose members have gained policy, management and technical training in Japan. Since these individuals are familiar with Japanese conceptions of best practices and G2G HRD practices, JICA sees it as important to gather their input on local policies relevant to economic cooperation and business relations which might affect the adaptation of the Japanese model.

The activity of non-corporate Japanese MeLAs such as JICA and AOTS in shaping the processes of adaptation and their context is complemented by collective corporate MeLAs representing unions and employers, including JILAF and Keidanren respectively. Since 1989, JILAF has been dedicated to promoting a free and democratic labor movement through the establishment of independent trade unions in developing countries (Gajewska, Citation2013). JILAF’s strategic mediation approach entails coordinated advocacy targeting national and international labor organizations, training activities for, and with, local unions and the provision of expert advice and guidance to both internationalizing Japanese firms and Indonesian unions. In addition, JILAF shares intelligence with RENGO and Keidanren on overseas trade unions and labor market institutions.

At the national level, JILAF reaches out to international union advocacy organizations, the trade unions of the host country, and RENGO. This outreach helps shape the host country’s labor market institutions for Japanese MNCs, particularly in promoting the ‘harmonious’ labor relations associated with the Japanese HRM-ER practice. JILAF also engages with a variety of actors, namely international NGOs, advocacy groups and think tanks in promoting a democratic labor movement in less developed countries, such as Indonesia, that are sympathetic to this ER approach. JILAF’s HRD activities are generally created and delivered in order to meet demand either from the government, such as the Ministry of Labor through grant assistance for Japanese NGOs, or from labor-related organizations, including ILO, ITUC and RENGO. Such activities range from the tailoring of training templates to the co-creation of a bespoke training program with the client organization. In broad terms, research participants suggest that ‘JILAF training schemes, seminars and advocacy endeavors represent the pillar of Japanese diplomacy, i.e. grooming Japanophile leaders’ (group interview, JILAF, 2019). Through these various advocacy and HRD activities, JILAF has an impact on the Indonesian labor market characteristics, especially by seeking to produce a setting more conducive to the development of ‘harmonious’ employment relations from within.

On the corporate side, Keidanren plays a somewhat similar role in exercising influence on local directors and managers. This includes coaching the director and management trainees in implementing Japanese business philosophy and management practices in their organizations. As described by one of the representatives (Keidanren, 2019), this training is not merely technical upskilling but an investment in producing a conducive context for the adaptation of the Japanese model:

‘Training local management and directors with Japanese personnel management is the best way to support local companies and Japanese affiliates; Keidanren investment interests are in increasing the number of Japanese management supporters’.

‘JJC promotes policy advocacy based on social dialogue and direct communication with the Indonesian government representing Japanese investors and Chamber of Commerce. JJC submits policy proposals directly to the federal government, e.g. identified issues, engaged and proposed mitigation. JJC established a long-standing relationship with the Indonesian government; JJC has power and resources to do so’.

Our research also identified two Indonesian corporate MeLAs with crucial roles in adaptation processes: KADIN and APINDO. KADIN oversees FDI and foreign business practices, promotes business competitiveness and shapes national policy dialogue and development. Its interests lie in advancing the business environment by seeking foreign investors, expertise and technology. At the meso level, Japanese MeLAs establish relations with KADIN with the aim of institutionalizing the adaptation of the Japanese model. KADIN negotiates with its Japanese counterparts and represents the voice of local industrial economy actors. Such interactions demonstrate the importance of the meso-level of activity for both Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs, as they have more limited operations at macro and micro levels.

APINDO oversees national and organizational HRM-ER policies, practices and communicates directly with the government on policy reform. APINDO’s institutional role is to monitor the impact of foreign influence on ER issues, considering issues such as the appropriateness of Japanese ER practices for the Indonesian context. APINDO has strong relations with the government and other stakeholders. Specifically, it has a network across Indonesia in order to navigate local interests and mobilize local industrial economy actors. Japanese MeLAs have developed solid relations with APINDO, and through it to the frontline network of local actors. Moreover, since its establishment in 1975, former trainees of Japanese MeLAs have comprised the majority of the members of the APINDO board of directors. At both the national and organizational level, APINDO has direct influence on ER. In fact, it is the only official organization representing the employer and management in tripartite IR disputes in Indonesia (Caraway et al., Citation2015).

Overall, there are clear contrasts between the activities and objectives of Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs. The primary interest of local MeLAs is to promote and protect local institutions and management practices. Their activity is concentrated on improving business competitiveness, human capital development and attaining international standards for Indonesia’s HRM-ER practices. Local regulations and constraints on direct influence at organizational and workplace levels mean Japanese MeLAs rely on their networks (advocacy, policy lobbying, trained alumni) and systemic coordination with Indonesian MeLAs to create the conditions of diffusion-adaptation of dominant JMSs. Thus indirect and procedural influences on adaptation processes are particularly significant.

Discussion and conclusion

We have argued that the roles and the coordinated transfer activities of meso-level actors have been underplayed in understanding how management practices are transferred into host country contexts. The evidence presented here differentiates between, and demonstrates the significance of, the roles of non-corporate and corporate MeLAs in processes of diffusion-adaptation in ‘best practice’ transfer. We have applied the SSDC theoretical framing to this novel analysis of the roles and institutional effects of MeLAs in an EME characterized by a relatively open-business system with weak labor market institutions and inefficient regulatory regimes. The study produces conceptual, empirical and practical contributions to our understanding of processes of diffusion-adaptation of dominant management practices.

Theoretical implications

Conceptually, our study has elaborated the SSDC theoretical framework in unpacking processes of diffusion and adaptation, differentiating in particular between the influence of dominance and societal effects and how these effects are created. Our distinctive contribution is in conceptually and empirically teasing apart societal and dominance effects and their inter-relationships. This has allowed us to understand and theorize these dominance and societal effects in a more complex way. Our findings show how societal effects are themselves subject to dominance effects through the practices of MeLAs and their alumni. Much as recent theorizing of institutional logics has unpacked their character and acknowledged the significance of different levels of action (Durand & Thornton, Citation2018), our research explicates how the effects of the SSDC theoretical framework are neither monolithic nor mechanical in their impact and that action at the micro-, meso- and macro-levels are all relevant to understanding diffusion-adaptation in management practice transfer (Soehardjojo et al., Citation2022). The SSDC framework facilitates the conceptualization of the importance of institutionalized networks in the exercise of both dominance and societal effects in ameliorating EME labor market institutions. Key enabler networks of actors beyond the MNCs are demonstrated to be significant in both Japan and Indonesia, central to navigating societal and institutional constraints to enable the diffusion-adaptation. Our evidence underlines the importance of multiple effects on workplace organization, management philosophy and practice. It also reinforces the recognition that these may stem from both host and home country actors operating at national and subnational levels. In particular, our study sheds new light on the importance of meso-level institutional factors and actors. It is at this level that MeLAs are particularly influential, helping shape both dominance and societal effects while simultaneously contributing to their reproduction. The findings contribute to work in institutional theory that has examined the way that actors inhabit and participate in complex institutional settings (Delbridge & Edwards, Citation2013; Creed et al., Citation2020).

Our research addresses directly the importance of the hitherto largely neglected meso level. Studying the meso level is useful in three major ways. First, a focus on the meso-level in the transfer of practices to an EME context with societal and institutional constraints relevant to HRM-ER practice modification pressure has underscored the important influence of different types of MeLAs (both corporate and non-corporate) and differentiated between MeLAs from home and host countries. This research has extended and deepened understanding of such intermediaries in the diffusion-adaptation of the imported Japanese HRM-ER practices to the weak labor market institutions of Indonesia. Second, and relatedly, a focus on the meso level in assessing the SSDC effects has shed light on the complex processes through which societal and dominance effects are constituted and experienced. Third, the paper illustrates the institutional complexity within which diffusion-adaptation takes place and which the MeLAs themselves play a significant role in maintaining.

Empirical implications

Firstly, as called for by Edwards et al. (Citation2013), our findings provide an empirical elaboration of the SSDC theoretical framework and underscore not only the complexity of the interconnected processes of diffusion-adaptation, but also the significance of transfer activities at the subnational (meso) context (Monaghan et al., Citation2020) and the multiple socioeconomic and industrial relations actors involved in these processes (Bamber et al., Citation2021; Vincent et al., Citation2020). We distinguish between two types of MeLAs and present new insights into the roles of such organizations operating both in the home and host country. The influence of these actors is not restricted to their own direct involvement. Equally important is the pervasive presence of MeLAs’ trainee alumni (i.e. AOTS, JICA and JILAF) which creates a wide, interlocking, local network system that variously reinforces or moderates the effects of local institutional arrangements. These Japanese-trained Indonesian alumni encourage system reform in order – in their view – to improve the strategic direction and international competitiveness of the Indonesian economy and the effectiveness of its human resources. They are keen to embrace what they understand as the ‘best practice’ of a progressive JMS that has been adopted globally and is part of other host countries’ modern HRM-ER systems.

The findings allow us to differentiate among MeLA roles and show that both Japanese and Indonesian MeLAs are instrumental in developing the basis of dominance effects in Japan and in shaping society effects, and how they are experienced, in Indonesia. We have thus extended empirical evidence and understanding of the processes through which both dominance and societal effects are constituted and influence the negotiated transfer of management practices (Pudelko & Tenzer, Citation2013; Sheehan & Sparrow, Citation2012). It stands repeating that the Japanese ODA is a major and global undertaking but has been under-researched. Japan has dispatched 197,000 experts to 183 counties since 1954 while developing 654,000 trainees from 187 countries. Ours is one of the first studies to examine in detail the processes and outcomes of these activities (see also Gajewska, Citation2013). A meso-level focus discloses the complexity of interactions between Japanese and Indonesian actors which constitute the societal effects – and their interplay with dominance effects – that are experienced by local actors in their adaptation of the dominant Japanese model. It is in this societal context that conventions and institutional arrangements constitute resources and constraints that influence the actions of corporate managers and employees.

Managerial/practical implications

Our capacious and multi-level study introduces a range of practical issues for a number of different actors. HR managers may wish to review and consider the ways in which the elements of imported management practices are brought together within specific firms and workplaces. Similar considerations will be relevant to organized labor and employee representatives at workplace and organizational levels. Our study shows that the effects of globalizing capitalist forces, national institutional norms, laws and notions of ‘global HRM-ER best practice’ are adapted within distinct local institutional contexts. A key insight from the study is the role played by actors beyond those directly related to the corporation. This raises a number of issues for HR managers, starting with their awareness of these actors and also embracing the potential that working with these may offer. A reciprocal set of issues may be identified for organized labor and third party actors given the significance of international labor organizations, advocacy groups and think tanks. Questions include both what model is diffused-adapted and how. Future research might explore the nature of systematic adaptation and the diffusion channels, e.g. how do HR managers identify practices that they wish to pursue, and what strategies are needed to navigate between the modified and local ones?

Managers may find value in further reflection on the specific nature of the influences at work in shaping their contexts. We have demonstrated that significant but complex nature of dominance and societal effects in the local organizational context. Unpacking these influences may help companies respond effectively to the changes/needs of a regional economic bloc and the global marketplace, their manifestations at national and subnational levels, and to understand the attendant implications for cross-border HRM-ER practices at the organizational level. Perhaps the most practical strategy would follow the configurational approach to HRM, which may be presented as a development from the ‘best practices’ or the best fit view of local HR management and union leaders (Boselie & Paauwe Citation2009; Fichter et al., Citation2011). In this approach, firms configure their management practices in ways shaped but not determined by their contexts. Thus, HR managers may have considerable latitude, though they are likely to need to engage with meso-level actors and understand the meso-institutional factors in navigating to a successful local outcome. It follows that HR managers may have a more active role – and one that extends beyond the four walls of the workplace – than is often assumed.

Conclusion

All in all, our evidence suggests that individual MeLAs influence diffusion-adaptation in different but related and often coordinated ways. The activities of Japanese collective corporate MeLAs have an impact in both Japan and Indonesia. By contrast, from our findings, it can be argued that Japanese non-corporate MeLAs’ are primarily involved in training schemes and socioeconomic cooperation development of Indonesian actors with impact on the host nation, although some of this activity takes place in Japan where trainees are exposed to the Japanese society-in-dominance effects that demonstrate the Japanese post-WWII industrial development miracle. These are both elements of a broad-based and concerted attempt to redefine the trainees’ mindset, social responsibility and contribution, and to influence the Indonesian context of operation of Japanese MNCs and their subsidiaries. Indeed, there is perhaps a neo-colonial undertone to some of how Japan’s MeLAs reported on their perceived roles in ‘standardizing’ Indonesia business systems and ‘modernizing’ Indonesian-style labor relations that are heavily regulated by the government toward foreign practices after 33 years of dictatorship (Burton et al., Citation2003) and the 1997 Asian and 2007 global financial crises (Ford, Citation2000).

Further research should examine how the roles of MeLAs differ from one national business system to another, in particular further considering how MeLAs operate in coordinated and liberal market economies. It could draw on multiple levels of analysis and deploy a multi-faceted SSDC framework to examine the complex inter-relationships of corporate, ODA and society actors and their implications for workplace organization. It would also be interesting to contrast the findings with those of other home and host countries, but this may be particularly important in emerging economies with different political economies, such as those in Eastern Europe and South America with which Japan sustains its strong business and socioeconomic and multilateral relations. The evidence certainly supports the value of locating studies of cross-border HRM-ER practices and their transfer in their wider sociopolitical and economic spectrum (Makhmadshoev & Laaser, Citation2021). In our view, the meso-level merits a prominent place in such multilevel analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants in this study did not agree that their data be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joey Soehardjojo

Joey Soehardjojo (PhD Warwick Business School) is a JSPS fellow at Hitotsubashi University, Faculty of Commerce Management, Japan and an ESRC research fellow at Cardiff Business School. His main research area of focus is the diffusion processes and implications of MNC cross-border management practices and policy development in the emerging market economies of Southeast Asia. The ESRC research project consolidates his doctoral and fieldwork JSPS studies (covering China, Japan, Indonesia, Myanmar and Thailand) while developing new insights into the impacts of tripartite arrangements among government agencies, collective corporate and intermediary ODA actors at the meso-institutional level. His work has been published at EID Journal and been recognized with best PhD dissertation awards from the Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA), the Academy of International Business (AIB) and the European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD).

Rick Delbridge

Rick is Professor of Organizational Analysis at Cardiff Business School and co-convenor of the Centre for Innovation Policy Research (CIPR). His research interests include the management and organization of innovation, employment relations and Japanese management practices. He is Editor-in-Chief of Research in the Sociology of Work and has research interests across employment relations, management and organization. His work has been recognized with best paper prizes from Academy of Management Review and Organization Studies.

References

- Almond, P. (2011). The sub-national embeddedness of international HRM. Human Relations, 64(4), 531–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710396243

- Aoki, K., Delbridge, R., & Endo, T. (2014). Japanese human resource management in post-bubble Japan. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(18), 2551–2572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.722118

- Bamber, G. J., Cooke, F. L., Doellgast, V., and Wright, C. F. (Eds.), (2021). International and comparative employment relations: Global crises & institutional responses (7th ed.). SAGE.

- Boselie, P. & Paauwe, J. (2009). Human resource management and the resource-based view. In The SAGE Handbook of Human Resource Management (pp. 421–437).

- Bennington, L., & Habir, A. D. (2003). Human resource management in Indonesia. Human Resource Management Review, 13(3), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00041-X

- Budhwar, P. S., Varma, A., & Patel, C. (2016). Convergence-divergence of HRM in the Asia-Pacific: Context-specific analysis and future research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 26(4), 311–326.

- Burton, J. P., Butler, J. E., & Mowday, R. T. (2003). Lions, tigers and alley cats: HRM’s role in Asian business development. Human Resource Management Review, 13(3), 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00047-0

- Caraway, T. L., & Ford, M. (2017). Institutions and collective action in divided labour movements: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Industrial Relations, 59(4), 444–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185617710046

- Caraway, T. L., Cook, M. L., & Crowley, S. (Eds.). (2015). Working through the past: Labor and authoritarian legacies in comparative perspective. Cornell University Press.

- Chiang, F. F., Lemański, M. K., & Birtch, T. A. (2017). The transfer and diffusion of HRM practices within MNCs: lessons learned and future research directions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1246461

- Creed, W. D., Hudson, B. A., Okhuysen, G. A., & Smith-Crowe, K. (2020). A place in the world: Vulnerability, wellbeing, and the ubiquitous evaluation that animates participation in institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 47(3), 358–381. 24p. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0367

- Delbridge, R., Hauptmeier, M., & Sengupta, S. (2011). Beyond the enterprise: Broadening the horizons of International HRM. Human Relations, 64(4), 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710396388

- Delbridge, R., & Edwards, T. (2013). Inhabiting institutions: Critical realist refinements to understanding institutional complexity and change. Organization Studies, 34(7), 927–947. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613483805

- Dieleman, M., & Sachs, W. M. (2008). Coevolution of institutions and corporations in emerging economies: How the Salim group morphed into an institution of Suharto’s crony regime. Journal of Management Studies, 45(7), 1274–1300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00793.x

- Do, H., Patel, C., Budhwar, P., Katou, A. A., Arora, B., & Dao, M. (2020). Institutionalism and its effect on HRM in the ASEAN context: Challenges and opportunities for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 30(4), 100729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100729

- Doner, R. F., Noble, G. W., & Ravenhill, J. (2021). The political economy of automotive industrialization in East Asia. Oxford University Press.

- Durand, R., & Thornton, P. (2018). Categorizing institutional logics, institutionalizing categories: A review of two literatures. Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 631–658. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0089

- Edwards, T., & Kuruvilla, S. (2005). International HRM: National business systems, organizational politics and the international division of labour in MNCs. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519042000295920

- Edwards, P. K., Sánchez-Mangas, R., Tregaskis, O., Lévesque, C., McDonnell, A., & Quintanilla, J. (2013). Human resource management practices in the multinational company: A test of system, societal, and dominance effects. ILR Review, 66(3), 588–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391306600302

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Elger, Tony, & Smith, Chris. (2005). Assembling Work: Remaking factory regimes in Japanese multinationals in Britain. UP Catalogue, Oxford University Press, number 9780199241514.

- Endo, T., Delbridge, R., & Morris, J. (2015). Does Japan still matter? Past tendencies and future opportunities in the study of Japanese firms. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12039

- Fichter, M., Helfen, M., & Sydow, J. (2011). Employment relations in global production networks: Initiating transfer of practices via union involvement. Human Relations, 64(4), 599–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710396245

- Ford, M. (2000). Research note: Indonesian trade Union Developments since the Fall of Suharto. Labour and Management in Development, 1(3), 1–10.

- Ford, M., & Pepinsky, T. B. (Eds.). (2014). Beyond oligarchy: Wealth, power, and contemporary Indonesian politics. Cornell University Press.

- Ford, M., & Sirait, G. M. (2016). The state, democratic transition and employment relations in Indonesia. Journal of Industrial Relations, 58(2), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185615617956

- Gajewska, K. (2013). Varieties of regional economic integration and labor internationalism: The case of Japanese trade unions in comparison. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 34(2), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X12442577

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. In Varieties of Capitalism. Oxford University Press.

- Iwashita, H. (2021). Multilingual mediators in the shadows: A case study of a Japanese multinational corporation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1965008

- Liker, J. K., Fruin, W. M., & Adler, P. S. (1999). Bringing Japanese management systems to the United States. Remade in America: Transplanting and transforming Japanese management systems. Chapter 3. Oxford University Press.

- Malik, A., Pereira, V., & Budhwar, P. (2021). HRM in the global information technology (IT) industry: Towards multivergent configurations in strategic business partnerships. Human Resource Management Review, 31(3), 100743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100743

- Mamman, A., & Somantri, Y. (2014). What role do HR practitioners play in developing countries: An exploratory study in an Indonesian organization undergoing major transformation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(11), 1567–1591. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.837089

- Makhmadshoev, D., & Laaser, K. (2021). Breaking away or holding on to the past? Exploring HRM systems of export-oriented SMEs in a highly uncertain context: Insights from a transition economy in the periphery. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(17), 3627–3658. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1841816

- Maurice, M., Sorge, A., & Warner, M. (1980). Societal differences in organizing manufacturing units: A comparison of France, West Germany, and Great Britain. Organization Studies, 1(1), 59–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084068000100105

- McSweeney, B., Smith, C., & Fitzgerald, R. (2008). Remaking management: Neither global nor national. In Chris Smith, Brendan McSweeney & Robert Fitzgerald (Eds.), Re-Making Management: Between Local and Global (pp. 1–16). Cambridge University Press, ISBN 113947197X, 9781139471978.

- Monaghan, S. M., Gunnigle, P., & Lavelle, J. (2020). Subnational location capital: The role of subnational institutional actors and socio‐spatial factors on firm location. British Journal of Management, 31(3), 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12341

- Morris, J., Delbridge, R., & Endo, T. (2018). The layering of meso‐level institutional effects on employment systems in Japan. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 56(3), 603–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12296

- Piekkari, R., Welch, C., & Westney, D. E. (2022). The challenge of the multinational corporation to organization theory: Contextualizing theory. Organization Theory, 3(2), 263178772210987. https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877221098766

- Pudelko, M., & Tenzer, H. (2013). Subsidiary control in Japanese, German and US multinational corporations: Direct control from headquarters versus indirect control through expatriation. Asian Business & Management, 12(4), 409–431. https://doi.org/10.1057/abm.2013.6

- Pudelko, M., & Harzing, A. W. (2007). Country-of-origin, localization, or dominance effect? An empirical investigation of HRM practices in foreign subsidiaries. Human Resource Management, 46(4), 535–559. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20181

- Reiche, B. S., Lee, Y. T., & Allen, D. G. (2019). Actors, structure, and processes: A review and conceptualization of global work integrating IB and HRM research. Journal of Management, 45(2), 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318808885

- Rowley, C., Bae, J., Horak, S., & Bacouel-Jentjens, S. (2017). Distinctiveness of human resource management in the Asia Pacific region: Typologies and levels. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(10), 1393–1408. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1189151

- Sasada, H. (2019). Resurgence of the “Japan Model”? Japan’s aid policy reform and infrastructure development assistance. Asian Survey, 59(6), 1044–1069. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2019.59.6.1044

- Sheehan, M., & Sparrow, P. (2012). Introduction: Global human resource management and economic change: A multiple level of analysis research agenda. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(12), 2393–2403. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.668382

- Smith, C., & Meiksins, P. (1995). System, society and dominance effects in cross-national organisational analysis. Work, Employment and Society, 9(2), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/095001709592002

- Smith, C., McSweeney, B., & Fitzgerald, R. (Eds.). (2008). Remaking Management: Between Global and Local. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511753800

- Soehardjojo, J., Delbridge, R., & Meardi, G. (2022). The hidden layers of resistance to dominant HRM transfer: Evidence from Japanese management practice adoption in Indonesia. Economic and Industrial Democracy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X221086019

- Tyskbo, D. (2021). Competing institutional logics in talent management: Talent identification at the HQ and a subsidiary. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(10), 2150–2184. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579248

- Vincent, S., Bamber, G. J., Delbridge, R., Doellgast, V., Grady, J., & Grugulis, I. (2020). Situating human resource management in the political economy: Multilevel theorising and opportunities for kaleidoscopic imagination. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(4), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12328

- Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 740–762. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.55

- Williamson, H. (1994). Coping with the miracle: Japan’s unions explore new international relations. Pluto Press.

- Witt, M. A., & Redding, G. (2013). Asian business systems: Institutional comparison, clusters and implications for Varieties of Capitalism and business systems theory. Socio-Economic Review, 11(2), 265–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwt002

- Weinstein, M., Kochan, T., Kochan, T., Locke, R., Thomas, A., & Piore, M. (1995). The limits of diffusion: Recent developments in industrial relations and human resource practices in the United States. In Employment relations in a changing world economy (pp. 1–31). MIT Press.