Abstract

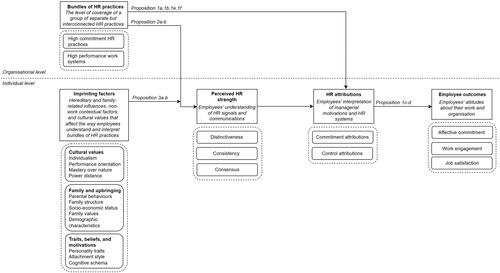

Human resource (HR) process research refers to the way HR practices are communicated in organisations, including the way these HR practices are understood (i.e. perceived HR strength) and attributed (i.e. HR attributions) by employees. Previous research has mainly focused on the outcomes of the HR process, while research that examines both antecedents and employee outcomes is relatively rare. This is especially the case for imprinting factors, defined as the hereditary and family-related influences, non-work contextual factors, and cultural values that may affect the way employees understand and attribute HR in their organisation. To further explore this relatively new area of research, this paper provides a systematic review of 19 empirical studies that investigate the role of imprinting factors in HR process research. Through the application of an imprinting framework with HR content and HR process theories, this review is orientated around the development of an integrative conceptual framework that elaborates on how, when, and to what degree imprinting factors influence the effect of bundles of HR practices on perceived HR strength and HR attributions and, as a consequence, employee outcomes. We conclude our review with several research directions that act as a platform for future scholarship.

Introduction

Strategic human resource management (HRM) research has traditionally adopted a firm-level, employer-focused approach to examine the relationship between (one or a set of) HR practices and employees and organisational outcomes (Wright & Ulrich, Citation2017). Despite the body of valuable knowledge gleaned from this body of work (known as HR content research; Sanders et al., Citation2014; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021), HR process scholars have contended that HR content research has oversimplified the HRM-performance relationship by assuming that one (or a set of) HR practice(s) influences all employees in the same way. By including contextual (e.g. different implementation by different line managers) and individual (e.g. work and non-work-related differences) factors, HR process researchers have attempted to explain why HR practices might lead to different employee outcomes (Kehoe & Wright, Citation2013; Nishii & Wright, Citation2008; Sanders et al., Citation2014). In doing so, HR process research has moved from ‘what’ is implemented to ‘how’ HR content is communicated and understood by employees, and ‘why’ the same HR practice(s) may work for one employee and not another (Boon et al., Citation2019; Hewett et al., Citation2019; Ostroff & Bowen, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020).

Building on attribution theories (e.g. Heider, Citation1958; Kelley, Citation1967, Citation1973; Weiner, Citation1985), two core streams of HR process research have emerged. In the first stream, Bowen and Ostroff (Citation2004) applied Kelley’s co-variation model of attributions (Kelley, Citation1967, Citation1973) to argue that the HRM-performance relationship is stronger when employees have a collective understanding of which behaviours are valued, expected, and rewarded by management, which helps to achieve the organisation’s strategic goals (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Ostroff & Bowen, Citation2016). This collective understanding is enhanced when the HR systems are characterised by distinctiveness (i.e. visibility, understandability, strategic relevance, and legitimacy of authority), consistency (i.e. instrumentality, the validity of HR practices, and consistency of messages), and consensus (i.e. fairness and agreement between messages senders). Although HR strength was originally intended as a unit-level construct, in this paper we follow previous researchers by focusing on perceived HR strength at the employee level (see Alfes et al., Citation2019; Bednall et al., Citation2022; Chacko & Conway, Citation2019; Delmotte et al., Citation2012).

In the second stream, Nishii et al. (Citation2008) applied Heider’s theory of causal attributions (1958) to the HRM field and introduced the term HR attributions. They argued that employees develop causal explanations (attributions) about why organisations implement specific HR practices within their organisation, which they categorised along several dimensions: internal vs. external (initiated by management or union and legal compliance), commitment vs. control (to promote well-being and service quality or to exploit and cut costs), and strategic vs. employee-focused (business or employee-focused philosophy). Their study showed that employees are more satisfied and show more organisational citizenship behaviours when they believe that HR practices are implemented due to benevolent, rather than exploitative motivations.

Until recently, HR process researchers have mostly focused on the effects of perceived HR strength and HR attributions (e.g. Chen & Wang, Citation2014; Hauff et al., Citation2017; Hewett et al., Citation2019; Shantz et al., Citation2016). As a result, we know less about the factors that lead to variations in perceived HR strength and HR attributions (Hewett et al., Citation2018; Sanders, Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2020). Scholars have attempted to remedy this gap by examining how internal organisational factors such as leadership (Weller et al., Citation2020) or high-performance work systems (Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015) act as prerequisites for perceived HR strength and HR attributions and, as a consequence, employee outcomes. However, researchers have noticed that even when accounting for these factors employees still strongly vary in their reactions to the same HR practices and systems.

HR process scholars have begun to speculate that these variations can be further explained by influences outside the control of the workplace (Hewett et al., Citation2018; Xiao & Cooke, Citation2020), including employee dispositions (e.g. personality), demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, education), cultural values (e.g. power distance), and family dynamics (e.g. parental support) (Aktas et al., Citation2014; Babar et al., Citation2020; Heavey, Citation2012; Kitt et al., Citation2020; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021). These studies emphasise that employees do not enter the workplace as a blank slate; they bring with them their past experiences, values, and beliefs that are formed as a result of how they have grown up and currently live and work (Lupu et al., Citation2018; Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013; Thornton et al., Citation2012). These scholars consider that non-work-related factors play an important role in explaining the relationship between bundles of HR practices (i.e. the content) and perceived HR strength and HR attributions (i.e. the process). Yet, despite the understanding that these factors are important for explaining why employees have different reactions to HR practices and systems, this body of work lacks a consistent and coherent theoretical and conceptual framework that explains the mechanisms through which these factors exert their effects. Moreover, there has been little progress toward the integration of HR content, perceived HR strength, HR attributions, and employee outcomes into one conceptual model which is sorely needed if researchers are to gain a full picture of the HRM-performance relationship (Guest et al., Citation2021; Ostroff & Bowen, Citation2016).

The purpose of this review is to advance scholarly understanding of the contextual boundary conditions within the HR content—HR process relationship by providing a review of the current work and developing an integrated conceptual model. More in detail, we seek to understand the degree to which employees’ upbringing, non-work contextual factors, and cultural values (i.e. ‘imprinting factors’) affect the way they understand and interpret bundles of HR practices which, in turn, influence perceived HR strength, HR attributions, and employee outcomes.

By addressing this question, this review contributes to previous research in the following ways. First, we provide a systematic review of 19 studies that examine the effects of imprinting factors on perceived HR strength and HR attributions. This review explores how imprinting factors (e.g. demographic characteristics, personality traits, beliefs, motivations, family relationships, cultural values, etc.) have evolved and diverged differently in the perceived HR strength and HR attribution streams. Furthermore, this review identifies, organises, and evaluates the empirical, theoretical, and methodological findings of these studies. The findings in this review offer researchers a better understanding of existing research and facilitate a more focused discussion of imprinting factors in current and future HR process research.

Second, by applying the insights of our review and an imprinting framework (Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013), we propose an integrative (both HR content and HR process) conceptual model. Drawing on social information processing theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978), we shed light on the underlying mechanisms (i.e. attention and interpretation) which explain how imprinting factors influence the relationship between HR content (i.e. bundles of HR practices) and perceived HR strength and HR attributions. Hence, our theorising extends prior theory beyond contextual work-related factors (e.g. line managers and coworkers) to explain how experiences before entering the workforce (e.g. educational and social processes) affect employees’ understanding and interpretation of HR practices (Cohen-Scali, Citation2003). Through the integration of both HR process and HR content into one model, we add further strategic value to HR practitioners by illuminating how HR systems can be designed for employees with different backgrounds and past experiences (e.g. unionised families, managerial vs. non-managerial parents, differing levels of parental support) to ensure they are being interpreted as intended for positive employee outcomes.

This paper is organised as follows. First, we describe the methods employed for the review and provide an overview of the results of the 19 studies. Second, drawing on these findings and the (HR) management and psychology literature, we propose a conceptual model and theoretically elaborate on how imprinting factors exert their influence on the relationship between bundles of HR practices and HR attributions (and employee outcomes) through perceived HR strength. Finally, we present a research agenda that outlines three directions for further study in this area and outline the practical implications of our review for HR practitioners and managers.

Method

Sample and search parameters

To be included in the initial search, studies were subject to several criteria. First, this review draws upon published and unpublished empirical quantitative (including experimental) studies in the field of HR process research. We did not include qualitative or theoretical papers so we could perform reliable statistical analysis between the studies. Otherwise, it would be difficult to compare qualitative or theoretical papers with quantitative studies in terms of theoretical frameworks, hypotheses, study characteristics (e.g. demographics, cultural context, etc.), and the validity of the studies. It can be noted that, during our search, we did not find any qualitative or conceptual papers that fell inside our parameters (i.e. the effect of imprinting factors on perceived HR strength or HR attributions). Hence, we conclude that this exclusion does not have a significant impact on our findings or conceptual model.

Second, to evaluate the impact of imprinting factors on perceived HR strength and HR attributions, we only included studies that directly statistically examine at least one imprinting factor (i.e. hereditary and family-related influences, non-work contextual factors, and cultural values) on either perceived HR strength or HR attributions (rated by an employee, line manager, or HR professional) at the individual level of analysis.

Third, following Hewett et al. (Citation2018), we included both attributions of intent (i.e. ‘HR attributions’) where the focal object of attribution is on HRM, management, or the organisation, and functional (HR) attributions where the focal object of attribution is an individual’s behaviour embedded within a HRM context (e.g. internal attributions of performance). While functional attribution research is not directly part of HR process research, HR and functional attribution research originates from similar attribution theories (Heider, Citation1958; Weiner, Citation1985) and offers meaningful insights into how imprinting factors influence the likelihood that employees will develop different types of (HR) attributions (e.g. internal vs. external attributions).

Finally, we included perceived HR strength papers that examined either individual or combined meta-features of perceived HR strength (i.e. distinctiveness, consistency, or consensus). Papers that examined one of the nine sub-features of perceived HR strength (i.e. visibility, understandability, legitimacy of authority, relevance, instrumentality, validity, consistency of HRM messages, agreement among principal HR decision-makers, and fairness; Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004) were not included as we decided this was not sufficient to be theoretically relevant to our review. For instance, we did not include papers that solely focused on employee perceptions of fairness or justice (a sub-feature of consensus) (e.g. Georgalis et al., Citation2015). In these papers, (perceived) HR strength theoretical perspectives were not used, so including these papers would not be theoretically relevant to our review that is focused on the HR process (perceived HR strength and HR attributions.

Imprinting factors: conceptualisation and definition

Within our search, we searched for a variety of imprinting factors including demographics (e.g. age, gender, education), intrapersonal characteristics (e.g. beliefs, values, and personality traits), family dynamics (e.g. parental relationships), and cultural values (e.g. country-level power distance). Hence, we include a broad range of imprinting factors in this review including the antecedents of imprinting experiences (e.g. gender, socio-economic background), the imprinting experiences themselves (e.g. parental relationships), and the effects of imprinting experiences (e.g. cultural beliefs). For instance, demographic characteristics such as one’s gender is acknowledged as an antecedent of imprinting experiences. Research has shown that gender (antecedent) influences the types of encounters (experiences) adolescents have with teachers, peers, and family units during their upbringing. Over time, these experiences influence the development of gender self-concepts, beliefs, and motives (effects) which then affect their workplace perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours in later life (Leaper & Friedman, Citation2007). Due to a lack of consistency in the current definitions of ‘imprinting factors’, we draw from prior research (Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013; Simsek et al., Citation2015; Stephens et al., Citation2014) and refer to imprinting factors as the hereditary and family-related influences, non-work contextual factors, and cultural values that may affect the way employees understand and attribute HRM in their organisation. This definition follows developmental psychology (Kandler & Zapko-Willmes, Citation2017) and anticipatory socialisation literature (Lupu et al., Citation2018) to argue that these characteristics are at least, in part, rooted in personal experience, culture, and nurture (e.g. childhood and upbringing) (Cohen-Scali, Citation2003; Thornton et al., Citation2012).

For our definition and conceptualisation of imprinting factors, we make a distinction between non-work factors and imprinting factors. We argue that non-work factors (e.g. marital status, number of children, work-related motivations, spousal support; see Geurts & Demerouti, Citation2004) should not be classified as imprinting factors because of the following three reasons (Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013). First, non-work factors do not necessarily emerge during sensitive periods of one’s development, i.e. they are not developed before individuals entered the labour market (Allik et al., Citation2004; Dekas & Baker, Citation2014; McCrae et al., Citation2002; Min et al., Citation2012). Second, non-work factors are not influenced or internalised by environmental contexts during early life or childhood (e.g. parents, teachers, role models, and cultural norms) (Allik et al., Citation2004; Cohen-Scali, Citation2003; Gibson et al., Citation2009; Ralston et al., Citation1997). Finally, in general, non-work factors do not remain stable over one’s lifetime (e.g. marital status vs. personality traits) (Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013; McAdams & Olson, Citation2010). To maintain theoretical consistency with these characteristics, factors that emerge once an individual enters the workforce (e.g. marital status) are outside the scope of this review.

Procedure

To acquire both unpublished and published studies, we applied a multi-method approach. First, five major online databases were searched: JSTOR, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, and Wiley Online using a Boolean search stringFootnote1. Because the term ‘imprinting factor’ is a relatively new concept in the HR (process) literature, we compiled a list of imprinting factor categories for our search terms to ensure that all relevant papers were identified. Second, a manual search was conducted in nine major peer-reviewed HRM and management journals: Human Resource Management, Personnel Psychology, Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Management, Academy of Management Journal, Human Resource Management Journal, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, The Journal of Organisational Behavior, and The Journal of Management Studies. Third, a cited reference search was conducted on the two seminal papers of Bowen and Ostroff (Citation2004) and Nishii et al. (Citation2008). Fourth, the papers referencing any of the previously published reviews in the area were examined including Ostroff and Bowen (Citation2016), Hewett et al. (Citation2018), and Wang et al. (Citation2020). We also included Farndale and Sanders (Citation2017) as their theoretical paper on the influence of national values on perceived HR strength is highly relevant to the current topic. Fifth, the matrices of HR process reviews (where available) were examined, including Bednall et al. (Citation2022), Hewett et al. (Citation2018), Hewett (Citation2021), and Wang et al. (Citation2020). Finally, to capture unpublished literature (including unpublished manuscripts and conference papers), authors of published papers in the research area were contacted directly. A call for papers was also disseminated via the AOM HR Division listserv and the HR process Google group. For relevant doctoral theses, a search via ProQuest Dissertations and Abstracts was conducted. The conference proceedings from the Academy of Management Annual Meetings in the most recent years were also searched.

Initial yield and sifting

The initial yield included 23 studies (21 papers) based on the abstracts of the studies. The papers were then read in full. During this process, each study was assessed for relevance by applying additional criteria. Two studies were removed whereby the imprinting factor (i.e. HR/managerial values and gender) was not associated with the individual providing the ratings of perceived HR strength or HR and functional attributions (García-Carbonell et al., Citation2018; Igbaria & Baroudi, Citation1995). A further two studies were removed as the imprinting factors (i.e. growth and esteem motivations, and locus of control) were aggregated or transformed into a work-related factor (i.e. work-motivations similarity and net resource index) when entered into the statistical analysis (Beijer et al., Citation2019; Mayo & Mallin, Citation2010). As a result, 19 studies (17 papers) remained including ten published papers (including two papers which included two studies each), two special issue papers, three conference papers and two doctoral studies. Discrepancies and decisions were discussed between the authors during this stage.

Data coding and analysis

Content analysis is regularly used to examine the content and methodological choices of studies (e.g. Hoobler & Johnson, Citation2004). For each of the 19 studies, we coded each study along 43 categories which are broadly categorised into three groups: 1) paper characteristics (e.g. type of study, year of publication, number of citations, country context), 2) research content (e.g. research aim, design, theoretical framework, contributions, limitations), and 3) empirical content (e.g. position of the variables, statistical analysis, main findings, level of analysis, source(s) of data, effect size). The examination of these categories for each stream facilitates the building of our conceptual model and the generation of suggestions for future research in the following sections. An abridged version of the studies in the sample is available in this paper ().

Table 1. Overview of the 19 studies included in the systematic review.

Reliability of the coding process

A coding taxonomy was designed to capture the aforementioned categories, each of which included a set of explanatory notes. Following the advice of Neuendorf (Citation2017), a structured process was followed. Initially, two scholars independently coded the same five studies that were picked via a random number generator from the 19 studies. The scholars discussed any discrepancies, alternate classification options, or when any doubt arose about the inclusion of any specific coding criteria or classification. The reliability was calculated. Cohen’s Kappa indicated a result of .84, indicating a high level of agreement. As a result, the first author of this review coded the remaining 14 studies.

Additional quality check

Five of the 19 studies in this review are not published in peer-reviewed journals (three conference papers and two theses) so we conducted an additional quality check. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) risk of bias assessment tool (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2018) for analytical cross-sectional studies was used to assess the five unpublished articles compared to the nine cross-sectional studies (excluding the experimental studies as these have another research design). The results showed that the five unpublished cross-sectional studies were rated on average 6.20 (SD = 1.48) out of eight (min = 4, max = 8) and the nine published cross-sectional studies scored on average 6.22 (SD = 1.39) out of eight (min = 4, max = 8). Given the very small difference between the two groups, we included the unpublished studies in our review.

Results

In the following section, the results from this review are described. First, an overview of the studies is presented. Then, the research content of the papers is explored, including the nature and relationship between the imprinting factor(s) and the HR process, whether the studies included HR content (e.g. individual or bundles of HR practices) in their conceptual models, theoretical frameworks, practical implications, and methodological limitations of the articles. Finally, we provide an overview of the major empirical findings. Throughout this section, distinctions are drawn between perceived HR strength and HR and functional attribution streams where present as the streams have evolved separately to date (see Hewett et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2020).

Characteristics of the studies

The majority of published papers were published in HRM and psychology-related journals including International Journal of Human Resource Management (3), Human Resource Management Journal (2), Journal of Organizational Behaviour (1), Basic and Applied Social Psychology (1), European Journal of Training and Development (1), Journal of Applied Psychology (1), Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (1), Management Revue (1), and Behavioural Research in Accounting (1).

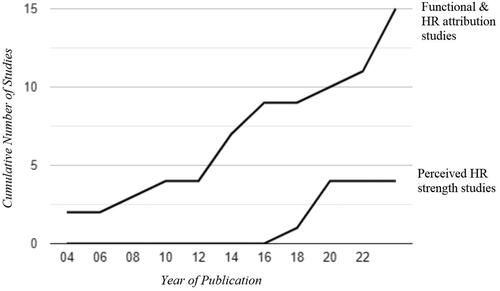

The majority (78.95%; 15 out of 19) of the studies consisted of HR and functional attribution studies, leaving the role of imprinting factors for perceived HR strength less explored. Almost half (9 out of 19; 47.37%) of the studies were published or presented in the past five years (2017-2022; mean age of the studies = 8.74 years old; SD = 9.71), indicating a recent bloom of interest in the field. All four of the perceived HR strength studies were published or presented since 2017 (mean age = 2.75 years old; SD = 1.50), and the HR and functional attribution stream was over seven years older on average (mean age = 10.33, SD = 10.38) (see ). This difference between the streams is likely because early attribution(al) theorists often emphasised the influence of individual characteristics (e.g. cognitive beliefs and biases) on attribution formation (Kelley & Michela, Citation1980) and functional attribution frameworks were developed far before the conceptualisation of HR strength in 2004. Indeed, a significant difference was found between the types of attributions (functional vs. HR) that are being examined over time (χ2(1) = 11.48; p <.01). This indicates a recent shift in scholarly attention towards HR attributions (e.g. Nishii & Wright, Citation2008; mean age = 4.38; SD = 3.02) compared to the older functional attributions sub-stream (mean age = 11.29; SD = 11.59), which are absent in the sample past 2013.

Figure 1. Number of studies examining imprinting factors for perceived HR strength and HR and functional attribution streams by year of publication.

The average number of citations according to Google Scholar (retrieved on 02/02/2022) for the studies (excluding conference papers and doctoral theses) was 52.77 (SD = 80.25). The highest cited study was by Van De Voorde and Beijer (Citation2015) with 279 citations on Google Scholar and 132 on Web of Science, averaging 39.86 Google Scholar citations a year. Van De Voorde and Beijer (Citation2015) investigated the influence of high performance work systems on employee outcomes mediated by HR attributions (including gender, age, and level of education as imprinting factors).

Research design and context

Design and methods

The majority of studies (ten out of 19; 52.63%) relied on survey methods to gather data from participants. Both streams relied on cross-sectional designs (14 of out 19 studies; 68.42%). This was the case for all four perceived HR strength studies, while the HR and functional attribution stream demonstrated a greater variety of research designs. Almost half (seven out of 15; 46.66%) of the HR and functional attribution studies applied experimental designs (i.e. using a vignette or scenario as an experimental stimulus), which included all functional attribution studies. Despite this, the difference in methodological design choices between the streams was only marginally significant (χ2(1) = 2.96, p <.10).

Both streams typically relied upon self-report, single-source data collection methods. Three HR attribution studies (Guest et al., Citation2021; Han, Citation2016; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015) and two perceived HR strength studies (Babar et al., Citation2020; Jorgensen & Van Rossenberg, Citation2019) gathered data from multiple actors (e.g. line managers and employees); the remaining 14 studies (78.94%) gathered data from one source. Five studies (26.31%) in the sample used a time-lagged design and only one study (5.26%) (Heavey, Citation2012) adopted a longitudinal approach. Heavey (Citation2012) examined the relationship between imprinting factors (e.g. proactive personality, conscientiousness, openness to experience, emotional stability, gender, major in school) and the HR attributions of organisational newcomers and how HR attributions change over time.

Sample and context

The mean number of participants for both streams was 448.26 (SD = 424.75). However, the perceived HR strength studies had a higher average number of participants (mean n = 744.50; SD = 687.75) compared to HR and functional attribution studies (mean n = 369.27; SD = 314.39), which was partially due to the differences in design choices. The greatest sample size was from Jorgensen and Van Rossenberg (Citation2019) who gathered data from 1589 employees and 186 managers in 29 organisations across ten countries (China, Denmark, Indonesia, Nigeria, Norway, Malaysia, Portugal, Oman, Tanzania, and the UK) to examine how national values of uncertainty avoidance influences employees’ levels of perceived HR strength.

Cross-cultural datasets were used in all four perceived HR strength studies, whilst only one of the 15 HR and functional attribution studies included more than one country in their sample which indicated a significant difference between the two streams (χ2(1) = 8.7, p < .01). While the perceived HR strength studies typically gathered data from several countries and covered a large range of industries in both Eastern and Western contexts, the HR and functional attribution stream often relied on data from individual companies and countries. The majority of HR and functional attribution studies (12 out of 15; 80%) were conducted solely in a Western context (i.e. Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, UK, and USA). Seven (out of 15; 46.66%) of these studies were conducted in the USA, and five of those studies relied solely on student samples within university settings. Finally, only one study (Jorgensen & Van Rossenberg, Citation2019) in our sample included a sample population from low-middle income countries (i.e. Indonesia, Kenya Lebanon, Malaysia, Nigeria, Oman, & Tanzania) (World Bank, Citation2021).

Research content

Imprinting factors

Twenty-one unique imprinting factors were captured by the studies within this review, with a total of 51 imprinting factors that were statistically examined across the 19 studies. Within the perceived HR strength stream, five different imprinting factors (a total of nine examined imprinting factors) were investigated: one national-level cultural value (i.e. uncertainty avoidance), one belief (i.e. faith in religion), one family relationship factor (i.e. parental support), and two demographic variables (i.e. gender and age). The position of the imprinting factors in the perceived HR strength studies varied. Of the nine examined imprinting factors, one (11.11%) was examined in a direct relationship (as an independent variable) with perceived HR strength, two (22.22%) were examined as moderators, and six (66.66%) were examined as controls.

In comparison, the HR and functional attribution stream contained 20 unique imprinting factors (a total of 42 examined imprinting factors), including five national-level cultural values (i.e. collectivism, individualism, mastery, power distance, and subjugation), 10 individual characteristics (i.e. agreeableness, belief in a just world, conscientiousness, emotional stability, implicit person theory, power distance orientation, proactive personality, openness to experience, social deference, and tolerance for ambiguity), and five individual-level demographic variables (i.e. gender, age, ethnicity, level of education, and major in school). Of these imprinting factors, 17 (40.48%) were examined in a direct relationship (as an independent variable) on HR and functional attributions, 4 (9.52%) were examined as moderators, and 21 (50%) were examined as control variables.

One perceived HR strength (Jorgensen & Van Rossenberg, Citation2019) and three HR attribution studies adopted multi-level perspectives and conceptual models (Guest et al., Citation2021; Han, Citation2016; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015). In addition, only one study within the sample incorporated both perceived HR strength and HR attributions into one conceptual and empirical model (Guest et al., Citation2021), indicating that little advancement has been made to address the calls for greater theoretical integration between the two streams of attribution theories. Furthermore, we found no studies that included imprinting factors as mediators when perceived HR strength, HR attributions, or functional attributions were the outcome variable. This is unsurprising as, in line with our conceptualisation, imprinting factors are expected to remain relatively stable, even in response to environmental stimuli (e.g. HR practices).

HR content

Ten (out of 19; 52.62%) studies directly included HR content in their conceptual models, including high commitment HR systems (Farndale et al., Citation2020; Guest et al., Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021Footnote2), productivity-oriented HR systems (Han, Citation2016), high performance HR systems (Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015), performance appraisal quality (Babar et al., Citation2020), pay secrecy policies (Montag-Smit & Smit, Citation2021), workload management practices (Hewett et al., Citation2019), and clear job descriptions (Kitt et al., Citation2020). The majority (seven out of 10; 70%) of those studies were in the HR and functional attributions stream. Furthermore, HR content was positioned as an independent variable in all studies within the sample, which highlights the predominant scholarly focus on work-related antecedents of the HR process. Finally, in six (out of 10; 60%) of these studies, the imprinting factor was positioned as a moderator between HR content and the HR process. The remaining four (40%) studies included imprinting factors as control variables.

Theoretical frameworks, practical implications, and future directions

The studies drew on a variety of social, communication, and attribution theories. Within the four perceived HR strength studies, the most common theoretical frameworks (in three studies; 75%) used was a (perceived) HR strength framework (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004). Kelley’s co-variation model (1967), uncertainty reduction theory (Berger & Calabrese, Citation1975), signalling theory (Connelly et al., Citation2011), and social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964) were referenced once equally between the four perceived HR strength studies.

In contrast, the HR attribution stream relied more on early attribution(al) theories (Heider, Citation1958; Kelley, Citation1967; Weiner, Citation1985) which were referenced within 11 of these 15 (73.33%) studies. More recent HR attribution studies more readily relied on HR attribution theory (Nishii & Wright, Citation2008), signalling theory (Connelly et al., Citation2011), social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964), and social information processing theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978). Signalling theory was one of the few theories that was applied to both streams and was used as a means of theoretical integration between perceived HR strength and HR attribution frameworks in one study (Guest et al., Citation2021). However, beyond this, researchers demonstrated a propensity to rely on older theoretical frameworks and little advancement has been made towards the development of new (or integrated) theory.

Regarding practical implications, all four perceived HR strength studies referenced the importance of clear and consistent communication through formal and established channels within organisations. This was also emphasised within the HR and functional attribution which included the extension that managers should also communicate the rationale behind the implementation of certain HR practices (6 out of 15 studies; 40%). It was also similarly recommended that managers should be conscious of the cultural, individual, or status-dependent differences (e.g. stakeholders, organisational newcomers) that affect employees’ reactions and interpretations of HRM within their organisations (40%).

Finally, of the 17 studies that identified future directions, about half of the studies (9e out of 17; 52.94%) encouraged a closer examination of cultural factors (e.g. femininity, uncertainty avoidance), contextual influences (e.g. internal or external factors), or individual differences (e.g. skill levels, motivation, and values) on the HR process. Researchers also highlighted that future research should confirm their results across different organisational, economic, and industrial settings (four studies; 23.52%), and more closely examine the role of line managers in influencing employees’ cognitions and their formation of attributions (three studies; 17.64%). Methodological improvements (e.g. longitudinal, multi-level, and multi-source designs) were also highlighted as an important avenue for future research (eight studies; 47.06%).

Major empirical findings

Perceived HR strength studies

The four studies in the perceived HR strength stream demonstrated the effect of imprinting factors at multiple levels, including national-level uncertainty avoidance and individual-level faith in religion, parental support, age, and gender (Babar et al., Citation2020; Farndale et al., Citation2020; Jorgensen & Van Rossenberg, Citation2019; Kitt et al., Citation2020). In two studies, imprinting factors have been examined as moderators in the relationship between HR practices and employee outcomes. Specifically, HR practices (i.e. clear job descriptions & performance appraisal) had a stronger effect on perceived HR strength when imprinting factors (i.e. parental support and faith in religion) were low, rather than high (Babar et al., Citation2020; Kitt et al., Citation2020). In terms of demographic characteristics (e.g. gender and age), research has shown mixed results. One study demonstrated that older and female employees reported lower levels of perceived HR strength (Jorgensen & Van Rossenberg, Citation2019), but two studies found the influence of age and gender was non-significant or had only a marginal influence (Babar et al., Citation2020; Farndale et al., Citation2020).

HR and functional attributions studies

The 15 HR and functional attribution studies have empirically examined a variety of imprinting factors on a variety of attributions, including individual beliefs, motivations, and values (Chen & Young, Citation2013; De Stobbeleir et al., Citation2010; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021), personality traits (Heavey, Citation2012; Kaplan & Reckers, Citation1993), cultural values (Chiang & Birtch, Citation2007), and demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, educational level, and ethnicity) (Arvey et al., Citation1984; Chiang & Birtch, Citation2007; De Stobbeleir et al., Citation2010; Guest et al., Citation2021; Han, Citation2016; Heavey, Citation2012; Hewett et al., Citation2019; Montag-Smit & Smit, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015).

At the national level, Chiang and Birtch (Citation2007) demonstrated that individuals who live in cultures with high individualism, high mastery over nature, and low power distance values are more likely to develop internal over external (causal) attributions. At the individual level, scholars have demonstrated employees with strong personal beliefs (e.g. belief in a just world, implicit person theory) differ in their likelihood to develop internal (dispositional) and external (environmental) attributions (Chen & Young, Citation2013; De Stobbeleir et al., Citation2010). In addition, Heavey (Citation2012) illustrated that employees with certain personality traits (e.g. proactive personality, openness to experience, emotional stability) were more likely to interpret managerial motivations in a positive light, possibly to differences in their information-seeking behaviours.

Similar to the perceived HR strength studies stream, demographic-related (control) associations with HR and functional attributions have shown mixed results. Five studies found that women were more likely to attribute HR practices more positively (Guest et al., Citation2021; Han, Citation2016; Montag-Smit & Smit, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015). In contrast, four other studies found no significance for the role of gender on HR and functional attributions (Arvey et al., Citation1984; Heavey, Citation2012; Hewett et al., Citation2019; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021). Similarly, mixed results are found for employees’ age on HR and functional attributions (Arvey et al., Citation1984; Han, Citation2016; Hewett et al., Citation2019; Montag-Smit & Smit, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Li, Citation2021; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015). However, scholars have indicated that employees with higher educational levels and employer-focused degrees (e.g. HR) are more likely to interpret managerial motivations to benevolent rather than exploitative reasons (De Stobbeleir et al., Citation2010; Heavey, Citation2012).

Imprinting in HR process research: towards an integrative conceptual model

In the following section, we develop a conceptual model that explains the effects of imprinting factors on the relationship between bundles of HR practices and employee outcomes via perceived HR strength and HR attributions. Drawing on the empirical findings of the 19 studies in this review and the wider (HR) management and psychology literature, we start by theorising the relationship between bundles of HR practices, HR attributions, and employee outcomes, followed by the elaboration of the mediating effect of perceived HR strength. Finally, we include the moderating effect of imprinting factors. A series of propositions are presented and the conceptual model is displayed in .

Bundles of HR practices and employee outcomes: the mediating role of HR attributions and perceived HR strength

HR process research has inspired a plethora of research that empirically investigates the effect of HR content (i.e. individual or bundles of HR practices) on perceived HR strength and HR attributions (and employee outcomes) (see for reviews Bednall et al., Citation2022; Hewett, Citation2021; Hewett et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2020; Xiao & Cooke, Citation2020). Instead of focusing on specific individual HR practices, in the strategic HR literature, HR practices have often been studied together as bundles of HR practices—a set of separate but interrelated and internally consistent HR practices—that are hypothesised to collectively enhance employee and organisational performance (Boon et al., Citation2019). These bundles have been variously referred to as high performance work systems (HPWS; Appelbaum et al., Citation2000), high commitment HR practices (Collins & Smith, Citation2006; Walton, Citation1985), high performance HR practices (Sun et al., Citation2007), and high performance work practices (Combs et al., Citation2006).

While all these bundles of HR practices typically comprise similar practices including employment security, selective recruiting, extensive training, and employee participation, they differ in their target. For instance, high commitment HR practices focus more on enhancing the commitment of employees, while bundles like high performance HR practices and HPWS focus more on enhancing the performance of employees and can be seen as more control-based (Boxall, Citation2012). For instance, Boxall (Citation2012) states that high commitment HR practices in comparison to HPWS ‘involves practices that aim to enhance employee-commitment to the organisation rather than practices that are narrowly focused on control or compliance’ (p. 173). Van De Voorde and Beijer (Citation2015) argue that HPWS may be viewed in a less positive light by employees as these bundles may signal that increased work effort is expected. In this paper, we therefore refer to bundles of commitment, such as high commitment HR practices, and more control-based HR practices, such as HPWS.

Bundles of HR practices provide (contextual) cues that shape employees’ perceptions and interpretations of these bundles of HR practices (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978); these interpretations are important to consider in the relationship between enacted bundles of HR practices and employees’ attitudinal and behavioural responses (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Nishii et al., Citation2008). According to Nishii et al. (Citation2008), employees develop judgments toward management in the form of HR attributions. Commitment HR attributions refer to a belief that HR practices are implemented to improve work quality and employee well-being. In contrast, control HR attributions refer to a belief that HR practices are intended to cut costs and increase control over employees (Nishii et al., Citation2008).

According to social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, Citation1960), employees develop more positive attitudes and behaviours if they feel favourable treatment by the organisation. High commitment HR practices signal the importance of commitment to employees (Walton, Citation1985). They are designed to enhance quality, employee well-being, and strengthen the attachment between employees and their organisation (Nishii et al., Citation2008). High commitment HR practices signal to employees that management genuinely cares about them and their wellbeing (Bal et al., Citation2013). In this case, employees experience greater levels of support and trust from management so they feel more satisfied in their role. They are more likely to form commitment attributions and feel a sense of reciprocation to their organisation, leading to higher levels of affective commitment (defined as ‘positive feelings of identification with, attachment to, and involvement in, the organization’; Meyer & Allen, Citation1984, p. 375), work engagement (defined as ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’; Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74) and job satisfaction (defined as ‘a state of mind determined by the extent to which the individual perceives her/his job-related needs to be met’; Evans, Citation1997, p. 328).

On the other hand, more control-based bundles of HR practices like HPWS will signal the importance of extracting value and high performance from employees. Employees in these conditions are more likely to experience intense work environments which leads to feelings of strain, frustration, and burnout (Shantz et al., Citation2016). We can expect that employees will view these practices as being motivated primarily by management’s desire to increase performance to improve the competitive position of the organisation, rather than by a concern for employee welfare (see Jensen et al., Citation2013; Kroon et al., Citation2009; Van De Voorde & Beijer, Citation2015). In turn, employees are more likely to form control attributions and feel less reciprocation to their organisation which leads to negative attitudes (e.g. less affective commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction).

Furthermore, we draw on HR attribution theory (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Kelley, Citation1967; Nishii et al., Citation2008) to argue that the relationship between bundles of HR practices and HR attributions is facilitated by the level of coverage of bundles of HR practices within an organisational unit through the mechanisms of distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus. Van De Voorde and Beijer (Citation2015) and Sanders, Yang, and Patel (Citation2021) propose that when management implements more bundles of HR practices they have ‘higher coverage’. In a high coverage situation (i.e. where more bundles of HR practices are enacted), HR practices stand out in the environment. They affect a wider range of employees and are more visible to organisational members. This increases distinctiveness which leads to more opportunities for HR sense-making and the development of HR attributions. Higher coverage also means that there is more internal consistency because bundles of HR practices are more consistently applied across organisational members. Compared to low coverage situations, high coverage situations have more reinforcing and complimentary practices which are more likely to send compatible signals, which leads employees to experience greater levels of consistency (see also Guest et al., Citation2021). Finally, in high coverage situations, employees are more likely to be exposed to the same HR practices and managed in the same way. Hence, employees are more likely to agree on how they are treated by management which results in similar HR attributions and consensus between organisational members.

To conclude, when more bundles of HR practices are enacted (both high commitment HR practices and HPWS) they have greater coverage. In turn, they signal distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus to employees through more visible, mutually reinforcing, and similar messages within organisational units. The greater the level of perceived HR strength, the more opportunities employees have to make sense of HRM which leads to higher levels of HR attributions (both commitment and control attributions). We present our first set of propositions below.

Proposition 1a: The level of coverage of high commitment HR practices will be positively associated with HR commitment attributions.

Proposition 1b: The level of coverage of HPWS will be positively associated with HR control attributions.

Proposition 1c: HR commitment attributions will be positively associated with employee outcomes (i.e. affective commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction).

Proposition 1d: HR control attributions will be negatively associated with employee outcomes (i.e. affective commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction).

Proposition 1e: HR commitment attributions will mediate the relationship between high commitment HR practices and employee outcomes (i.e. affective commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction).

Proposition 1f: HR control attributions will mediate the relationship between HPWS and employee outcomes (i.e. affective commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction).

Proposition 2a: Perceived HR strength (distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus) will mediate the relationship between high commitment HR practices and HR commitment attributions.

Proposition 2b: Perceived HR strength (distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus) will mediate the relationship between HPWS and HR control attributions.

The moderating role of imprinting factors

Imprinting and (HR) management research

Imprinting refers to a ‘process whereby, during a brief period of susceptibility, a focal entity develops characteristics that reflect prominent features of the environment, and these characteristics continue to persist despite significant environmental changes in subsequent periods’ (Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013, p. 199). Imprinting can be understood as a type of rapid ‘phase-sensitive learning’ that occurs at particular life stages. Through a period of socialisation, characteristics of environmental imprinters (e.g. culture, family members, role models) become embedded within individuals during sensitive periods of their lives that become resistant to change (Lupu et al., Citation2018; Thornton et al., Citation2012).

Imprinting frameworks have been applied at multiple levels in several research fields including organisational ecology, institutional theory, career research, management, and child psychology (for reviews see Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013; Simsek et al., Citation2015). At the macro-level, imprinting researchers have identified influential imprinters on organisational designs and structures, including HRM. At this level, researchers describe how external forces (e.g. technological, economic, and social) leave imprints on organisations that are maintained through educational institutions, national values, organisations, politics, traditions, and the media (Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000; Kim & Gao, Citation2013; Seidel, Citation2020; Shinkle & Kriauciunas, Citation2012; Stinchcombe, Citation1965). National institutions provide era-specific templates which guide organisational structures, designs, and systems, which persist even in the face of modernizing influences (Peng, Citation2004). For example, older organisations in China can still be identified by their deeply entrenched structures that were shaped by Communist bureaucracy at the time (Marquis & Qian, Citation2014).

At the individual and unit level, imprinting scholars have for a long time understood the powerful role of imprinting on individuals’ behaviours, attitudes, and interpretations of their environment (Lorenz, Citation1935; Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013). Imprinting research strongly suggests that, during sensitive developmental periods, children and adolescents ‘intentionally and unintentionally gather occupational information from the environment’ (Jablin, Citation2001, p. 734) by listening to and observing influential role models (e.g. teachers, mentors) and family members (e.g. parents) talk and behave within their jobs (Dekas & Baker, Citation2014; Lupu et al., Citation2018). They then internalise their values, beliefs, and behaviours as their own and then mirror these characteristics well into their careers (Dekas & Baker, Citation2014; Levine & Hoffner, Citation2006; Lupu et al., Citation2018; Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013; Mortimer & Finch, Citation1986). Early developmental (family, educational, and social) experiences play a role in a variety of occupation-related outcomes, including childrens’ and adolescents’ academic engagement, career aspirations, occupational choices, their importance of specific job rewards, occupational identities, and union attitudes (Barling, Citation1990; Darensbourg & Blake, Citation2014; Lupu et al., Citation2018; Mccall & Lawler, Citation1976; Sarma, Citation2014). While environmental imprinters can exist at different levels (e.g. individual, unit, and national), the effect of imprinting on individuals inherently occurs at the individual level, so we consider imprinting factors as an individual level construct.

Despite this promising body of work, the application of imprinting frameworks within HR process research is exceedingly rare (e.g. Leung et al., Citation2013). HRM researchers have begun to theorise that early infant-parent relationships of founding organisational members affect the design of initial HR structures and philosophies (command vs. control) which persevere across time and organisational restructuring (Hedberg & Luchak, Citation2018; Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000; Leung et al., Citation2013; Mcevily et al., Citation2012; Stinchcombe, Citation1965). Similarly, there is a body of empirical evidence that demonstrates early mentoring experiences and educational achievements provide behavioural and attitudinal templates for employees that last long into their careers (Andrew, 2013; Azoulay et al., Citation2017; DiMaggio, Citation1997; Mcevily et al., Citation2012).

We follow this body of work and argue that imprinting provides a useful framework to understand how and why employees vary in their interpretations of HRM in the same organisation. In the following section, we draw on a social information processing framework to elaborate on the moderating effect of imprinting factors on the relationship between bundles of HR practices and perceived HR strength. Although we acknowledge that the imprinting factors within this review consist of a variety of imprinting antecedents (e.g. gender), experiences (e.g. parental behaviours), and effects (e.g. uncertainty avoidance), we focus our elaboration on imprinting experiences which are most central to an imprinting framework.

Imprinting factors: a social information processing theory perspective

Social information processing (SIP) theory is a theoretical framework that explains the way people make sense of and act in organisations (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978). SIP theory acknowledges that people enter social situations with a set of predetermined influences which are both environmentally and biologically based (Crick & Dodge, Citation1994). When applied to HRM, SIP theory provides a framework which proposes that employees develop stable and unambiguous perceptions of HRM by drawing on their own internal thoughts, cues in the HRM environment, and what others say and think about HRM.

In previous HRM literature, SIP theory has been predominately applied to suggest that employees rely on their perceptions of HR practices and communications with line managers and co-workers when developing their interpretations of HRM and, as a consequence, their behaviours and attitudes (e.g. Bos-Nehles and Meijerink, Citation2018; Jiang et al., Citation2017; O’Reilly & Caldwell, Citation1985). SIP theory proposes that employees first subconsciously choose to attend to aspects of the HR environment and then cognitively interpret this information in the form of HR attributions (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978). In this sense, employees’ perceptions of HR practices and their interactions with co-workers and line managers guide their attention and interpretation of HR practices and systems, which ultimately influences the way they make sense of HRM (Jiang et al., Citation2017; Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978).

In line with SIP theory, employees’ attention and interpretation of HRM can also be influenced by personal attributes and internal databases of stored information (Nishii & Wright, Citation2008; Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978). In other words, employees’ perceptions and attributions of HRM are not only influenced by the immediate work environment, but also by social interactions which happen outside organisations, including those that occurred in the past. Imprinting theorists claim that past experiences provide stores of casual knowledge and cognitive schemas that can be drawn on to make (in)effective causal inferences about the role of HRM in organisations, especially when external information is limited (Kelley, Citation1973; Mitchell & Kalb, Citation1982; Whitehead, Citation2014). For instance, when adolescents are frequently exposed to work-related conversations with their parents during sensitive developmental periods, imprints can lead to the formation of particularly persistent cognitive schemas so they become automatic and can be activated without much effort or thought. These cognitive schemas then work to guide employees’ attention and interpretation of HRM in later life by directing, organising, and processing HR-specific information according to pre-established automatic schemas and beliefs (Cialdini & Goldstein, Citation2004; DiMaggio, Citation1997; Dokko et al., Citation2009; Hedberg & Luchak, Citation2018; Higgins, Citation2005; Kostova, Citation1999; Kostova et al., Citation2008) including how HR practices relate to managerial motivations and expected behavioural norms (Ali et al., Citation2021; Bos-Nehles & Meijerink, Citation2018; Jiang et al., Citation2017; Sanders, Yang, & Patel, Citation2021).

Following SIP theory and an imprinting framework, we propose that the relationship between bundles of HR practices and perceived HR strength is stronger when imprinting factors are high (more intense), rather than low (less intense). That is, the more intense the imprinting factor (i.e. the level and frequency of which an imprinting experience is encountered by an individual), the more developed the cognitive schema which leads to greater attention and interpretation of bundles of HR practices and resulting perceived HR strength. When imprinting factors are more intense, employees can easily attend, retrieve, and interpret HR practices by drawing upon automatic cognitive scripts they have developed in the past, even in ambiguous situations where there is less coverage of HRM (i.e. low bundles of HR practices) (Dalal et al., Citation2015; Fiske & Taylor, Citation1991; Kelley, Citation1973). Developed cognitive scripts make bundles of HR practices ‘stand out’ and become more salient to them which increases distinctiveness, especially when compared to employees who have not had this type of imprinting. For example, if parents with particularly strong union values repeatedly mention to their children that HR systems are simply there to exploit employees and cut costs, they will more readily pay attention to control-based signals and practices in their organisation and attach more weight to this information (De Winne et al., Citation2013; Guest & Rodrigues, Citation2020).

More intense imprinting factors also cause employees to more readily perceive consistency. This is because HR practices are more automatically interpreted, distorted, and assimilated according to one’s cognitive schema and associated suppositions, beliefs, and expectations (e.g. Chen & Young, Citation2013; Heavey, Citation2012; Jones et al., Citation1972; Kelley & Michela, Citation1980). Employees with more developed cognitive schemas more readily selectively seek specific HR practices and signals which confirm their pre-conceived notions of HRM, even if this means subconsciously overlooking inconsistent or incompatible HR practices (Heavey, Citation2012; Kelley & Michela, Citation1980). In other words, employees will only attend to HR practices and signals and develop HR attributions if they are (subconsciously) motivated to do so (Drover et al., Citation2018; Guest et al., Citation2021; Heavey, Citation2012; Hewett et al., Citation2019; Jorgensen & Van Rossenberg, Citation2019).

Finally, employees with more intense imprinting factors are more able to seek consensus with personal memories of past experiences (e.g. conversations with family members). Drawing on these imprinting experiences and associated schemas, employees are more likely to find agreement with their perceptions and interpretations of HRM. In contrast, employees who do not have implicit knowledge, experiences, and presuppositions of HRM are more dependent on aspects of the immediate work environment (e.g. clear and visible HR practices, internal consistency of HR practices, and conversations with co-workers and line managers) to perceive distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus. Therefore, bundles of HR practices have a weaker relationship with perceived HR strength when imprinting factors are less intense. Hence, we present our final set of propositions below.

Proposition 3a: Imprinting factors will moderate the relationship between high commitment HR practices and perceived HR strength (distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus) so that the relationship is stronger when imprinting factors are more intense, rather than less intense.

Proposition 3b: Imprinting factors will moderate the relationship between HPWS and perceived HR strength (distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus) so that the relationship is stronger when imprinting factors are more intense, rather than less intense.

General discussion

This review sought to understand how, when, and to what degree imprinting factors influence employees’ perceived HR strength and HR attributions. To address these questions, we conducted a systematic literature review to understand past and present research, and to uncover the empirical, methodological, and theoretical gaps in the field. Drawing upon an imprinting framework (Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013), HR strength theory (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004), HR attribution theory (Nishii et al., Citation2008) and SIP theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978), we propose an integrative conceptual model and theorise the effect of imprinting factors on the relationship between bundles of HR practices and perceived HR strength and, as a consequence, HR attributions and employee outcomes. We further theorise the mechanisms that underpin these relationships. In the section below, we make our final contribution by detailing the limitations in the current body of imprinting in HR process research and outline three avenues of future scholarship in the field. This paper is concluded with the practical implications of this paper for HR practitioners and professionals.

Future directions and limitations

Empirical testing of the model

First, our propositions require empirical testing. We acknowledge that prior research has been limited in scope regarding the examination of imprinting factors, which has often placed a greater focus on work-related antecedents (e.g. HR practices, leadership, co-workers). While significant advancements have been made that link imprinting with HR process and content research, few studies have examined imprinting factors beyond the individual level (Chiang & Birtch, Citation2007). Research on family units (e.g. number of siblings, socio-economic status, political affiliations) is especially lacking. Indeed, only one study in our review directly examined the moderating effect of family relationships (i.e. parental support) between clear job descriptions and perceived HR strength (Kitt et al., Citation2020).

Future research should place a greater emphasis on examining the characteristics of family dynamics which could influence the HR process. For instance, Hedberg and Luchak (Citation2018) theorised that infant-parent attachment styles (i.e. anxious, secure, and avoidant) could affect the level and quality of employees’ attachment to their organisation. Employees who experienced unmet security needs during childhood, such as in the case of those with an anxious attachment style, may be more sensitive to HR practices as they are driven to seek environmental cues that fulfil their need to be seen as adequate in the eyes of authority figures (e.g. managers) (Berglas, 2006). Beyond this, future research should could also examine characteristics of family structures (e.g. nuclear family vs. extended family structures) or family values (e.g. family political affiliations) that have been overlooked in previous literature to bring this work forward.

Moreover, we focus on imprinting experiences in our elaboration, but more research is needed to illuminate the role of imprinting antecedents (e.g. demographic characteristics) and imprinting effects (e.g. cultural values) that precede or follow imprinting experiences. This is especially the case for the experiences that are associated with demographic characteristics (antecedents) which were found to have mixed effects in our review. Indeed, imprinting antecedents are considered proxies of imprinting experiences. Social psychologists emphasise that imprinting antecedents like gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic status influence the types of communities adolescents grow up in. Subsequently, the types of social interactions and daily activities adolescents are exposed to within these communities impact the way they make meaning of social information and the types of information they notice in later life (Bussey & Bandura, Citation1999; Leaper & Friedman, Citation2007; Mollborn et al., Citation2012). Examining imprinting antecedents (e.g. gender) in HR process research—without considering the associated experiences that follow (or if they are experienced at all)—tells us little about the intensity of those experiences and the degree to which they can be expected to be associated with the HR process. Hence, it is not surprising that we found mixed results of demographic characteristics in our review.

To take this work forward, researchers could examine the types of experiences that girls and boys are subject to during childhood, including experiences within family units, the media, and schooling. One area of exploration could be the intensity of which adolescents are exposed to traditional gender ideologies, both culturally and within family units, which have been shown to affect gender beliefs and career aspirations (Rudman & Phelan, Citation2010). Similarly, social class has been identified as a relatively stable imprinting factor that influences how employees cognitively appraise themselves in organisations (Kish-Gephart & Campbell, Citation2015). Due to their limited access to social safety nets, children in lower-class families are taught by their parents to be aware of social and political threats that may risk their financial well-being (Kish-Gephart & Campbell, Citation2015; Stephens et al., Citation2014). Over time, these experiences may facilitate a cognitive schema that causes employees to become more attentive to HR systems to alleviate feelings of uncertainty and avoid behavioural mistakes that may lead to unemployment (Adler et al., Citation1994). Similarly, common cultural experiences that occur within generational cohorts (e.g. the Great Depression, World War II, and the Civil Rights movement) create similarities in how groups of people expect to be managed, which could uncover the aspects of HRM they attend and interpret as most important (Costanza et al., Citation2012; Marquis & Tilcsik, Citation2013). Future research is needed in this area to help academics and practitioners identify the most important experiences which may lead to asynchronous interpretations of HRM if left unmanaged.

Furthermore, we propose SIP theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Citation1978) as the core theoretical framework to understand the effect of imprinting factors on the HR content—HR process relationship. However, Guest et al. (Citation2021) have also proposed signalling theory (Connelly et al., Citation2011; Ehrnrooth & Björkman, Citation2012) as an avenue to theoretically integrate both HR content and HR process models. Yet, their study only examines one meta-feature of perceived HR strength (consistency). In addition, perceived HR strength was positioned as a moderator between bundles of HR practices and HR attributions, rather than a mediator as theorised in our model. Supporting our theorisations, a recent meta-analysis by Bednall et al. (Citation2022) has provided empirical support that perceived HR strength is better positioned as a mediator in the bundles of HR practices—employee outcome relationship. Our model provides an attempt for such integration, though we join HR process scholars by calling for better theoretical integration between HR process and HR content perspectives, and a greater investigation of the role of perceived HR strength as a mediator in the proposed relationships (Bednall et al., Citation2022; Guest et al., Citation2021; Hewett et al., Citation2018; Ostroff & Bowen, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020).

Addressing methodological limitations

Second, to answer the aforementioned propositions, a robust methodology is required within the HR process field. At present, research has been saturated with cross-sectional, single-source designs that are often restricted to one country context. Only a few studies in our review used time-lagged or longitudinal designs which raises concerns about causality between imprinting factors and perceived HR strength and HR attributions. Although it is impossible for HR content or HR process to directly influence an individual’s past imprinting experiences, an individual’s perceptions and attributions of HRM could influence their recollections of childhood and imprinting experiences. Research on adult recollections of childhood memories suggests that ‘childhood events are filtered through an adult autobiographical memory to produce narrative accounts of early experiences that only in a small part remembered’ (Wells et al., Citation2014, p. 19). Memories are non-consciously filled in, re-constructed over time, and altered in response to the present context. Research has shown that memory can be biased by current emotional states (e.g. depressive symptoms) which can alter the way people recall childhood events like maternal support and attachment information (Alexander et al., Citation2010; Dujardin et al., Citation2014). As a result, we can not reliably assume that adult recollections of childhood phenomena are accurately recalled so they are free from memory bias (Colman et al., Citation2016). Hence, longitudinal studies are needed to test the causal nature of these relationships and to reduce or eliminate memory bias. Along these lines, is worth connecting early childhood experiences with employees’ understanding and attribution of bundles of HR practices by tracing back respondents with early childhood studies.

Furthermore, despite the methodological rigour gained by the number of (functional and HR attribution) studies that have adopted experimental field designs, these studies further inflate the issues of external generalisability. This is compounded by the tendency of HR process researchers to use Western samples, often with student populations (Bednall et al., Citation2022). In addition, qualitative research including interviews and case studies should be taken into account to achieve more insight and understanding of the creation and effectiveness of different imprinting factors. Through the application of robust methodologies, such as (quasi) field experiments and longitudinal studies, as well as qualitative studies, it would be of interest to empirically examine Simsek and colleagues’ (2015) suggestion of a three-stage imprinting process: (1) the genesis of imprints (where individuals adopt characteristics of their environment during sensitive developmental periods), (2) the metamorphosis of imprints (where imprints change, evolve, and transform), and (3) the manifestations of imprints (where imprints influence behaviours, attitudes, and employee outcomes). Indeed, researchers have argued that cognitive schemas tend to be easier to change during childhood but can become increasingly rigid and difficult to modify as people grow older (Padesky, Citation1994). However, it has also been indicated that cognitive models are susceptible to ‘unfreezing’ when during periods of uncertainty, such as periods of role transitions (Ashforth & Saks, Citation1996) where they can be replaced by schemas that are more consistent with the work environment (Dokko et al., Citation2009).

This serves as an interesting avenue and new direction for the application of imprinting in the HR process field. Researchers could explore when are the most sensitive periods where individuals are most susceptible to imprints, the organisational conditions that encourage the reconfiguration of imprints, and the degree to which newly acquired (conflicting) information alters one’s cognitive schemas about HRM. If future researchers intend to address these questions, they should employ both qualitative and quantitative methods. For qualitative methods, it would be useful to explore the genesis, metamorphosis, and manifestations of imprinting factors over time. This way, researchers can begin to undercover the core imprinting experiences and factors that are important for perceived HR strength and HR attributions. In addition, it would also be useful to test our conceptual model using quantitative methods to address the methodological flaws in prior literature by paying particular attention to longitudinal, multi-actor designs across cultural contexts.

Operationalisation and categorisation of imprinting factors

Finally, it is acknowledged that the operationalisation and categorisation of imprinting factors require more attention. In our review, to not make our elaboration too complex, we focused on the intensity of imprinting factors (i.e. the level and frequency in which an imprinting experience is encountered by an individual). We proposed that the more intense an imprinting factor, the stronger the relationship between bundles of HR practices and perceived HR strength which subsequently leads to stronger HR attributions. Yet, we did not elaborate on the different types of HR attributions (i.e. commitment and control) employees develop as a result of imprinting factors, although it is assumed they differ depending on the type of HR practices an employee is paying attention to (i.e. HPWS or high commitment HR practices).

Indeed, several studies in our review demonstrate that employees develop different HR attributions according to different imprinting factors (e.g. Guest et al., Citation2021; Heavey, Citation2012; Montag-Smit & Smit, Citation2021). For instance, Montag-Smit and Smit (Citation2021) found that females were more likely to make benevolent HR attributions when compared to males, but younger employees were more likely to develop malevolent HR attributions when compared to older employees. Hence, it is clear examining that solely examining the intensity of imprinting factors only illuminates part of the picture. Future research could bring this work forward by expanding on both the nature and intensity of imprinting factors. For example, employees who grew up in strong union households are expected to attend to specific HR practices and draw different conclusions about management compared to employees who grew up in highly professional or managerial households (Guest & Rodrigues, Citation2020). By developing a typology of imprinting factors, researchers could make more accurate predictions about the types of HR attributions that develop as a result of imprinting factors.

It is also possible that imprinting factors may lead to differences in HR attributions depending on their type (e.g. beliefs or personality traits) and origin (e.g. cultural vs. individual). Along these lines, we categorise imprinting factors as an individual-level construct that captures a variety of interpersonal differences that contain a variety of experiences, beliefs, cultural values, motivations, and presuppositions. However, we do not yet know to what degree these differences are important for the HR process. Different types of imprints (e.g. beliefs vs. motivations) may precede or take precedence over one another in the causal attribution chain (Kelley & Michela, Citation1980). Certain imprinting dimensions may be insufficient to influence the HR process, or they may react with each other to produce amplifying, contradicting, or compensatory effects (Hewett et al., Citation2019; Kelley & Michela, Citation1980). It is also possible that different types of imprinting factors influence the meta-features of perceived HR strength (i.e. distinctiveness, consistency, or consensus) to different degrees. However, at present, the knowledge in this area is restricted.