Abstract

Constructive employee voice is important but challenging to promote in high power distance contexts. The unique and relative importance of HRM systems and leadership in promoting it is more generally little understood. This study investigates the unique and relative importance of a high-performance work system (HPWS) and transformational leadership (TL) for constructive employee voice behavior, as well as how individual-level power distance orientation (PDO) moderates those relationships. The analyses are based on a sample of 403 subordinates of middle managers in 232 domestic Russian organizations. The results show that both TL and HPWS relate positively to employee voice, but most importantly that HPWS is more strongly so related, that it significantly substitutes the relationship between TL and voice, and that the relationship between HPWS and voice is further strengthened by employee PDO. We also conducted post-hoc qualitative interviews with 25 employees in domestic Russian organizations to triangulate our quantitative results. The study contributes to research on employee voice, in particular to research on the relative importance of its antecedents, and to the emerging body of research that simultaneously considers HRM and leadership.

Introduction

Organizations today depend on employees’ ideas and opinions as contributions and inputs to accelerate both employee (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018) and organizational performance (Morrison, Citation2011, Citation2014). In this respect, the facilitation of employee constructive voice, defined as ‘the voluntary expression of ideas, information, or opinions focused on effecting organizationally functional change to the work context’ (Maynes & Podsakoff, Citation2014, p. 91), is a crucial organizational objective (Grant, Citation2013). Early research suggested that the two broad categories of (a) managerial practices and (b) organizational structures and policies are foundational antecedents to employee voice (Morrison & Milliken, Citation2000). The present study focuses on transformational leadership (TL) as a primary example of managerial practice and a high-performance work system (HPWS) as a primary example of organizational policies. Not only are TL and HPWS the most studied forms of leadership and HRM respectively (e.g. Boon et al., Citation2019; Ng, Citation2017) but the strong relationships of both TL and HPWS with employee voice behavior have also been confirmed by recent independent meta-analyses (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). However, despite this research and much understanding of the details of voice facilitation (Hu & Jiang, Citation2018; Morrison, Citation2011, Citation2014; Morrison & Milliken, Citation2003; Wang et al., Citation2019; Zhu & Akhtar, Citation2019), including the relative importance of many of its antecedents (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017), our current knowledge of the unique and relative importance of TL and HPWS for voice facilitation, and their respective roles in various cultural contexts and among individuals with different cultural orientations, is lacking. Based on this, the present study poses two research questions: 1) What is the unique and relative importance of TL and HPWS for employee constructive voice behavior in a high-power distance (PD) context. 2) How is this importance moderated by employee power distance orientation (PDO)?

These research questions have several important motivations. First, as for research question number one, all the research on TL and voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017) and HPWS and voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018) has been conducted within separate research streams. This reflects the general problematical situation with respect to research on leadership and HRM as emphasized by Leroy et al. (Citation2018), who also called for more simultaneous research on the joint effects of both. From a methodological standpoint previous research on their main effects on voice behavior involves a fundamental omitted variable bias (Hill et al., Citation2021). The consequence is that our understanding of their unique and relative importance for voice behavior is seriously limited, with a high likelihood that current evidence may be seriously biased. Further, while not paying attention to this particular unknown with respect to leadership and HRM, Chamberlin et al. (Citation2017) emphasized the need to better understand the relative strength and unique importance of various predictors, i.e. alternative explanations, of voice behavior. By focusing simultaneously on TL and HPWS as competing antecedents, we also extend the scarce research using ‘quantitative strategies to compare the relative merit of competing … theories’ (Leavitt et al., Citation2010, p. 645) which has great potential to support the ‘theory building process’ (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010, p. 621).

Second, regarding the context of the present study, collective beliefs play an important role in core theorizations of voice behavior (Morrison, Citation2011). In high-power distance (PD) contexts, where people tend to both believe and accept ‘that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally’ (Hofstede, Citation1980, p. 45), a tradition of speaking up is not only lacking but avoided, and its facilitation is thus associated with particular challenges (e.g. Huang et al., Citation2005). Yet, research on voice facilitation in such contexts has mainly been conducted in China (Aryee et al., Citation2017; Duan et al., Citation2017; Liang et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2019; Xiang et al., Citation2019; Zhu & Akhtar, Citation2019). Further, when examining the influence of leadership, such research has focused on the effects of non-participative styles of leadership (e.g. Chan, Citation2014; Lam & Xu, Citation2019; Li & Sun, Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2015). By focusing on TL in another high-PD context, that of Russia, the present study addresses the limited attention both to other non-Western cultural contexts and to Western leadership styles in research on voice behavior in non-Western, high-PD contexts. The hierarchical and authoritarian leader-centric culture in Russia (House et al., Citation2004, Citation2014) also provides a particularly interesting context for testing the relative importance of the two fundamental antecedents to voice behavior, leadership and organizational practices and policies (Morrison & Milliken, Citation2000).

Third, concerning research question number two, the influence of individual factors is incorporated in core theorizations of voice behavior (Morrison, Citation2011) and scholars have pointed to the importance of considering not only the broad cultural context, but the influence of individual-level cultural value orientations on organizational behavior (e.g. Gelfand et al., Citation2007). Power distance orientation (PDO), referring to the individual-level acceptance of unequal distribution of power, is important as it is deemed to centrally influence how employees react to leadership behaviors and organizational practices (Daniels & Greguras, Citation2014). Previous research on the moderating role of follower PDO on the effect of TL is inconclusive (Daniels & Greguras, Citation2014; Duan et al., Citation2017; Kirkman et al., Citation2009; Schaubroeck et al., Citation2007), as is related research on HPWS and cultural-level PD (Lin et al., Citation2020; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Wu & Chaturvedi, Citation2009). We have found no research on individual-level PDO and HPWS. In the present study, we extend the above research by examining the extent to which PDO moderates the relationships of TL and HPWS, respectively, with constructive voice behavior in a high-PD context. This also offers us one more opportunity to test the relative strength of the arguments for the main effects of TL and HPWS.

Based on a sample of 403 white-collar subordinates of middle managers in 232 Russian organizations, supplemented with 25 post-hoc semi-structured qualitative interviews, our study thus makes three main contributions. First, we contribute to research on TL and voice behavior generally (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017) and specifically in non-Western high-PD contexts (Duan et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2010). We also answer to calls for more research on HRM in high-PD contexts (Daniels & Greguras, Citation2014; Wu & Chaturvedi, Citation2009) and thereby contribute to research on HPWS and voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018). By extending research on all three elements - TL, HRM and voice behavior—to the under-researched context of Russia (Balabanova et al., Citation2022; Michailova et al., Citation2013), we answer calls for more country-specific research outside the USA, with due consideration of the local context while downplaying the prevalent ‘difference-oriented lens’ in cross-cultural research (Tsui et al., Citation2007, p. 467).

Second, and most importantly, we contribute to research on employee constructive voice behavior by answering calls to examine the unique and relative importance of various antecedents (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017) and by focusing on two fundamental ones, i.e. leadership and organizational practices (Morrison & Milliken, Citation2000) as well as their boundary conditions. In so doing we also contribute theoretically to the later interpretation of leadership substitutes theory (Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997) as well as methodologically to the literature on theory contesting (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010). Finally, this also extends the scarce but emerging simultaneous research on leadership and HRM (e.g. Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2021; Hauff et al., Citation2022; Jo et al., Citation2020; McClean & Collins, Citation2019), shedding more light on ‘how to effectively manage people in organizations’ (Leroy et al., Citation2018, p. 249).

From a practical standpoint our study begins to shed light on a highly relevant question: Should organizations in high-PD contexts invest primarily in HRM systems or rather focus on investments in developing the leadership style of their leaders to ensure the active involvement of employees in organizational matters?

Theoretical overview

An important distinction between TL and HPWS is that TL is constituted by a set of specific interpersonal leadership behaviours: articulating a vision, acting as a role model, developing team spirit, instilling high performance expectations, and providing individualized consideration and intellectual stimulation (Podsakoff et al., Citation1990, Citation1996). In contrast, a HPWS is constituted by a set of ‘interrelated’ and ‘mutually reinforcing organizational policies and practices …’ (Saridakis et al., Citation2017, p. 87) such as selection, job design, training, career opportunities, performance evaluation, and compensation (Boon et al., Citation2019).

Social exchange theory (SET) provides an overarching common theory that explains the influence of both TL and HPWS on voice behavior. SET postulates that employees are guided by the norm of reciprocity such that a favorable treatment received from the employer is reciprocated by behavior beneficial for the organization (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). Both TL and HPWS represent key means through which employees receive supportive and motivational treatment from their organizations (e.g. Kehoe & Wright, Citation2013; Tse et al., Citation2013) and constructive voice behavior is a key type of involvement in organizational matters through which employees can reciprocate their organizations for the received treatment (Zhu & Akhtar, Citation2019).

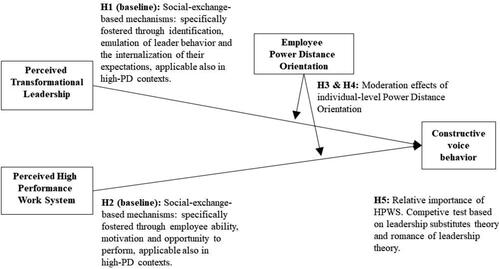

To further theorize the social exchange-based influence of HPWS and TL on constructive voice behavior, we draw on specific mechanisms which specify the nature of the social exchange involved. In the case of HPWS, we draw on the ability-motivation-opportunities (AMO) framework (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018), with a focus on ability and motivation enhancing effects (Mowbray et al., Citation2021). This suggests that the social exchange fostered by HPWS largely occurs through its effects on the resources specified in the AMO framework, essentially improving the likelihood that employees are both able and willing to engage in voice behavior. In the case of TL, we posit that the social exchange fostered by TL and the employee reciprocation that it triggers in the form of employee constructive voice largely occurs through follower’s identification with transformational leaders (Liu et al., Citation2010), the ensuing emulation of their behaviors (Yang et al., Citation2010), and the internalization of their voice expectations (Duan et al., Citation2017). We complement these with culture-specific arguments related to high-PD contexts to argue for our first hypotheses concerning the baseline relationships of TL and HPWS with constructive voice behavior (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Then, we argue that the effectiveness of this social exchange, i.e. the ways in which employees react to TL and HPWS, is likely to be contingent on individual cultural value orientations, specifically their PDO (Daniels & Greguras, Citation2014). This leads us to posit Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Finally, scholars have strongly argued for the importance of moving beyond confirmatory null-hypothesis testing (Leavitt et al., Citation2010) and toward conducting competitive tests (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010) in management studies to understand the relative importance of theories. Chamberlin et al. (Citation2017) specifically called for an increased understanding of the relative importance of predictors of voice behavior. To shed light on the relative importance of TL and HPWS as predictors of voice and to derive Hypothesis 5, we supplement key arguments about the above discussed social exchange-based mechanisms with supporting arguments based on leadership substitutes theory (Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997). Based on this, we suggest that HPWS is likely to not only offer a superior social exchange-based explanation of voice behavior, but also partially substitute the effects of TL.

Our conceptual model is illustrated in . Based on this overview, we turn to the development of the hypotheses.

Hypotheses development

The main effects of TL and HPWS

Transformational leadership and employee constructive voice

Extant research has identified TL as one of the most important leadership styles for facilitating voice, explaining significant variance in voice behavior as compared to other leadership styles and several other predictors (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017). Studies found TL to increase employee perceived psychological safety (Detert & Burris, Citation2007), autonomy, engagement, and self-efficacy (Hannah et al., Citation2016), all of which predict voice behaviors (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017, Citation2018), thereby offering potential explanations of the mechanisms of the influence of TL on voice. Theoretically, Duan et al. (Citation2017) specifically found TL related to employees’ motivations to speak up via the so-called Pygmalion process whereby employees internalize and identify with the transformational leader’s voice expectations. Constructive voice behavior is a mimicking/emulation of TL behavior in the sense of being intellectually stimulating, showing concern for the coworkers/unit and acting as a good role model to improve the performance of others or the work unit in line with the transformational purpose of TL. Second, the identification and internalization of TL behaviors are also likely to increase the feeling of safety, thus reducing employees’ fear of speaking up as well as reducing the perceived futility of doing so, all important antecedents for voice behavior (Morrison, Citation2011). Social exchange theory offers the general overarching argument for the effect of TL on constructive voice behavior. It suggests that by fostering desirable employee experiences and resources, such as autonomy, engagement, self-efficacy and identification with the leader, TL is likely to increase employees’ ability and motivation to reciprocate by contributing to the organization’s or work unit’s betterment also via constructive voice behavior. Thus, based on existing research, TL can be regarded a theoretically and empirically established important antecedent to constructive voice (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017).

TL has also been found related to employee voice in the high-PD culture of China (Duan et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2010). We expect it to affect employee constructive voice more generally in high-PD contexts, and not only based on the above mechanisms but also for two culture-related reasons associated with the strong role played by leaders and leader authority in such contexts, in particular in Russia (House et al., Citation2004). First, research suggests that in high-PD contexts employees are likely to need more external stimuli to change their reluctance to speak up (Huang et al., Citation2005; Liang et al., Citation2012). One reason for this is that constructive voice can lead to conflicts with the leader and be interpreted as a sign of disloyalty (Burris, Citation2012), which is likely to be particularly discouraging in high-PD contexts. However, this ceteris-paribus reason is likely to be overcome to the extent local leaders actually engage in TL behaviors because voice behavior is expected and encouraged by transformational leaders (Duan et al., Citation2017). Thus, we argue that transformational leaders are likely to foster non-typical voice behavior also in high-PD contexts where leadership authority is the rule and employees are particularly likely to abide by their expectations. In line with this, research suggests that TL induces more emulation of leader behaviors, not less, in high-PD contexts (Schaubroeck et al., Citation2007; Yang et al., Citation2010), and specifically fosters internalization of transformational leaders’ voice expectations in such contexts (Duan et al., Citation2017). Second, as in many high-PD contexts, a mix of transactional, authoritarian, and paternalistic leadership has historically been the norm in Russian organizations (McCarthy et al., Citation2010). Employees in such contexts may also perceive the voice-promoting transformational leadership behavior as a ‘positive deviance’ that can encourage them to engage in ‘non-typical’ voice behavior (cf. Crede et al., Citation2019). In support of this argument, Koveshnikov et al. (Citation2020) found TL in Russia positively associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem, and job control, i.e. important resources likely to increase constructive employee voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017, Citation2018).

Based on all of this, we expect transformational leaders to not only generally help followers to engage in constructive voice behavior but specifically to do so in high-PD contexts, including Russia, where the average cultural-level PD score has been found to be among the highest in the world (House et al., Citation2004). We thus put forth our first baseline hypothesis, which is generally in line with previous research and which we test in the specific context of Russia.

Hypothesis #1: TL is positively associated with constructive employee voice behavior in a high-PD context.

HPWS and employee constructive voice

A large body of research provides evidence for a positive relationship between HPWS and employee reciprocation via voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018; Mowbray et al., Citation2021). There are several arguments for this relationship. First, drawing on the opportunity bundle in the AMO framework (Harley, Citation2020; Mowbray et al., Citation2021), ‘voice’ is influenced by the extent to which HPWS is designed to enhance employee involvement and participation (Budd et al., Citation2010; Wood & de Menezes, Citation2011). However, also the other HPWS practices serve to empower employees (Ehrnrooth & Bjorkman, Citation2012; Liu et al., Citation2020) and are thus likely to influence voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018). In particular, and most relevant for the present study, the ability-enhancing mechanisms of HPWS can improve employees’ ability to speak up in several ways. Careful selection of employees is likely to increase their competence, and training and development can further improve employees’ work-related knowledge, thus enhancing their ability to give voice ( Mowbray et al., Citation2021; cf. Liu & Lin, Citation2021 ). Also, the motivation-enhancing practices in the form of competitive pay and the pay-for-performance element of HPWS are likely to both increase the competence of employees to give voice (sorting effect; Gerhart & Fang, Citation2015) and motivate them to do so (Mowbray et al., Citation2021).

Second, and very much related to the above, a well implemented HPWS is likely to ‘signal to employees that voice is valued within the organization’ (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018, p. 1299), which is of key importance for voice behavior (Morrison, Citation2011, Citation2014). The ability- and motivation enhancing effects of HPWS, and the related signaling of employees’ importance, are also likely to influence employee constructive voice behavior by reducing both the perceived internal fear and external futility of engaging in such behavior, another set of important antecedents of voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017; Morrison, Citation2011, Citation2014). Again, social exchange theory offers the general overarching argument for the effect of HPWS on constructive voice behavior, in this case with the social exchange centrally revolving around employees reciprocating the provision of AMO-related resources by engaging in prosocial and constructive voice behaviour (Kehoe & Wright, Citation2013; Mowbray et al., Citation2021). This is in line with the argument that the extent of the reciprocation crucially depends on psychological resources provided by HPWS (Miao et al., Citation2021, p. 445). Further support is provided by evidence that HPWS is positively related to several mechanisms that are likely to help explain the influence of HPWS on constructive voice behavior: engagement (Zhang et al., Citation2013), resilience and engagement (Cooke et al., Citation2019), job satisfaction and engagement (García-Chas et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Xian et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2018), positive mood, self-efficacy, job satisfaction and engagement (Huang et al., Citation2018; Ma et al., Citation2021). We note that engagement is one of the most important antecedents to voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017) and that it is crucially dependent on employee resources (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). Thus, based on existing research also HPWS, just as TL, can be regarded as a theoretically and empirically established important antecedent to constructive voice.

While we have found only one study on the impact of HPWS on employee constructive voice in high-PD contexts (Hu & Jiang, Citation2018), we suggest that its above argued effects will generalize to such contexts, including Russia. While scholars have for long argued that conformity with the national culture is important (e.g. Newman & Nollen, Citation1996), and more progressive HRM practices are not the norm in high-PD contexts, including Russia where HRM has mostly fulfilled a purely administrative function (Gurkov & Settles, Citation2013; Gurkov & Zelenova, Citation2011), Sturman et al. (Citation2012) suggest that they may be more effective exactly in such contexts. Also, Rabl et al. (Citation2014) argued that conformity to the national culture is not necessarily advantageous, and that the reverse may be true. Importantly, this argumentation is supported by recent evidence by Lin et al. (Citation2020) who found that the effects of HRM on innovation is stronger in high-PD contexts. In addition to the above arguments, we suggest that this may be due to the fact that in such contexts employees are more in need of the resources provided by HPWS, such as ability, appreciation, encouragement and confidence to step up, take initiatives and perform. In further support of this, there is evidence that HPWS practices have positive effects on distributive justice in South Korea (Chang & Hahn, Citation2006) and procedural justice and thereby also other employee attitudes in several high-PD contexts (Wu & Chaturvedi, Citation2009).

Finally, and specifically concerning Russia, while Russian employees are generally neither prepared nor accustomed to speaking up (McCarthy et al., Citation2010), they attribute a lot of importance to personal power and social status (Balabanova et al., Citation2016). The Russian context thus seems to offer a fertile ground for HPWS inducing employees’ status-related constructive voice behavior to demonstrate employee-specific knowledge and competencies for the purposes of their own ‘value enhancement’ (Wee et al., Citation2017, p. 2357), and with the aim of furthering their career advancement and the acquisition of more power.

In summary, as HPWS has the potential to both strongly enable and motivate employees to speak up (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018; Mowbray et al., Citation2021), we suggest it can help employees overcome the general resistance and unwillingness to do so in high-PD contexts (Huang et al., Citation2005; Liang et al., Citation2012), including Russia. Based on the above, we put forth our second baseline hypothesis.

Hypothesis #2: HPWS is positively associated with constructive employee voice behavior in a high-PD context.

The moderation effects of employee PDO

In addition to societal-level cultural values, employees possess individual-level cultural attributes (Gelfand et al., Citation2007). Moreover, research indicates that within-country (individual-level) variation in cultural values can be larger than country-level cultural differences (Au, Citation1999; Shenkar, Citation2001). One such cultural value is individual-level PDO which has been argued to have a more ‘theoretically direct relationship’ to employees’ reactions to leadership behaviors than other cultural values (Kirkman et al., Citation2009, pp. 745–746). By definition, high-PDO employees accept the imbalance of power between superiors and subordinates as legitimate (Lam & Xu, Citation2019) and are thus generally less likely to perceive voice behavior as socially accepted and desirable, and more likely to view it as riskier than their low-PDO counterparts. Such employees are thus more likely to simply follow authorities (Farh et al., Citation2007), which in most cases means that they withhold their personal opinions (Huang et al., Citation2005). However, extant research provides several arguments and evidence suggesting that subordinate emulation of leader attitudes, expectations and behaviors are accentuated among high-PDO employees in high-PD cultures such as Hong Kong (Schaubroeck et al., Citation2007) and China (Yang et al., Citation2010).

First, it is argued that higher-PDO employees are likely to internalize the expectations and attitudes of their leaders to a greater extent because these employees are more open and receptive to leaders’ influence. Importantly, Schaubroeck et al. (Citation2007) suggest that once high-PDO employees succumb to their leader’s influence they are likely to feel more confident in their ability to engage in behaviors promoted by the leader. In contrast, low-PDO employees will not be as receptive to leaders’ influence attempts as they are likely to perceive such attempts as less appropriate. Second, high-PDO employees are also likely to feel more obliged to reciprocate the treatment from their leaders through constructive voice (Zhu & Akhtar, Citation2019), particularly in the case of transformational leaders given the latter’s voice expectations (Duan et al., Citation2017). This suggests that the behavioral mimicry of TL behavior in the form of follower voice behavior may be enhanced among high-PDO individuals.

To test the strength of these arguments and to offer an additional test of the strength of the general arguments about high-PD contexts for Hypothesis 1 (if true, individual PDO should accentuate the effects), we put forth the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis #3: Employee PDO positively moderates the relationship between TL and employee constructive voice behavior such that the relationship is stronger when employee PDO is high.

In the case of HPWS we have not found research directly addressing the moderating effects of PDO on its influence, but one study examining a negative firm-level PD moderation finding no support (Wu & Chaturvedi, Citation2009), one conceptually proposing a negative cultural level moderation (Farndale & Sanders, Citation2017) and one finding support for the latter (Sanders et al., Citation2021). In contrast to this research, but in line with Lin et al. (Citation2020) who found evidence for a stronger effect of HRM in high-PD countries, we argue that employee reactions to HPWS are likely to depend on their individual-level PDO, and specifically so for their constructive voice behavior. The arguments to support this line of thinking are based on the idea that gains from practices that are likely to eliminate power inequalities may be higher in high-PD countries (Carl et al., Citation2004). As noted by Lin et al. (Citation2020, p. 2848), the strong negative relationship between ‘as is’ and ‘should be’ power distance measures in the GLOBE data suggests that ‘in societies where high power distance practices are prevalent, people prefer to experience an equitable distribution of power’.

Applying the AMO framework, the ability-enhancing (e.g. training) and motivation-enhancing (e.g. compensation) practices comprising HPWS attend to employee developmental and material needs, thus also likely to lower power inequalities and communication barriers between employees and managers. In high-PD countries, such practices are usually accessible only to a few people (Lin et al., Citation2020; Sturman et al., Citation2012). Given this, we can expect employees in high-PD countries to appreciate HPWS and that its social exchange-based resource (ability and motivation) and signaling effects on employees’ voice behavior (as outlined in connection to Hypothesis 2) are likely to not only be strong in high-PD contexts, but stronger compared to low-PD contexts.

By extension, the above cultural-level argumentation suggests an enhanced effect of HPWS among individuals with high PDO: To the extent those arguments are valid, high-PDO individuals will logically be more dependent on the developmental and motivational potential of HPWS, increasing the likelihood that HPWS provides external stimuli that help them overcome their general unwillingness to engage in constructive voice behaviour. The voice behavior of high-PDO individuals should thus be more strongly influenced by HPWS, as compared to low-PD individuals.

To test the strength of these arguments and to offer an additional test of the general arguments about HPWS in high-PD contexts for Hypothesis 2, we put forth the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis #4: Employee PDO positively moderates the relationship between HPWS and employee constructive voice behavior such that the relationship is stronger when employee PDO is high.

The relative importance of HPWS and TL

As argued above, both theory and evidence suggest that employee voice can be independently facilitated by both TL and HPWS, also in high-PD contexts. Yet, a theoretically and practically important but entirely unexamined question concerns the unique and relative importance of their main effects (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017, Citation2018) when considered simultaneously. Are employees more likely to be motivated and able to engage in constructive voice due to TL behaviors or due to HPWS? Social exchange theory postulates that the extent of employee reciprocation will depend on the perceived value and appreciation of the two focal types of organizational inducements, leadership and HPWS. The more important the inducement is from employees’ subjective point of view, the more effective that inducement should be in fostering reciprocating constructive voice behavior. The more specific theories of HPWS and TL, as discussed above, suggest distinct mechanisms of their influence, which are however partly overlapping in their effects on employees’ ability and motivation to speak up.

We know that in high-PD contexts such as Russia leaders tend to exert a significant culturally induced authority-based influence (McCarthy et al., Citation2010). As discussed above, the Pygmalion process suggests that employees in high-PD contexts tend to internalize and identify with the transformational leader’s voice expectations (Duan et al., Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2010), which is then primarily likely to increase their perceived safety and willingness to speak up (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017; Morrison, Citation2011). However, we have also argued that in high-PD contexts the ability-enhancing (e.g. training) and motivation-enhancing (e.g. compensation) practices comprising HPWS, including their signaling effects, represent an important form of social exchange that is likely to not only satisfy employee developmental and material needs, but also decrease power inequality and communication barriers, and thus increase voice behavior. While both HPWS and TL are thus likely to increase the perceived safety and motivation to speak up, in this sense their main effects may be partly complementary (and thus unique) and partly substitutive (cancelling each other out), HPWS seems to offer stronger inducements to do so. Some more support for the importance of the form of social exchange offered by HPWS can be found in evidence that in the high-PD context of Russia employees value financial and status-based inducements, including career opportunities, above other organizational inducements (Balabanova et al., Citation2016, Citation2022). This suggests that the broader and more substantive social exchange offered by HPWS may more strongly foster reciprocating constructive voice behaviors, as compared to that offered by TL.

Further support for this argument is offered by the later interpretation of leadership substitutes theory which posits that the main effects of organizational practices and processes, such as the ones comprising HPWS, may be more important than interpersonal leadership behaviors in influencing employee attitudes and behaviors (Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2021; Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997). The specific proposition is that organizational processes outside the reach of formal hierarchical leadership understood as pure ‘superior-subordinate interactions’ (TL being a good example) is not only likely to provide a more important and ‘sociologically inclined’ explanation of employee outcomes, but also likely to substitute some of the main effects attributed to leader-centric leadership behaviors in extant research (Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997, p. 98). This is a general theoretical proposition. We suggest that it is also likely to apply specifically to high PD contexts.

In summary, based on the above discussed partly distinct social exchange-based influence mechanisms of pure interpersonal TL behavior and HPWS, we expect both to exert some independent influence on employee voice behavior in high-PD contexts. However, we also expect that HPWS will not only foster stronger reciprocation and thus offer a superior explanation (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010; Leavitt et al., Citation2010) of voice behavior compared to TL, but that HPWS is also likely to substitute some of the main effects of TL on such behavior. To test this, we put forth our last hypothesis as follows.

Hypothesis #5: The main effect of HPWS will be relatively more important and partially substitute the relationship between TL and constructive employee voice behavior.

Methodology and research design

Our analysis uses two different datasets: a quantitative dataset collected through a survey of 403 white-collar employees working in domestic organizations in Russia and a qualitative dataset consisting of post-hoc semi-structured personal interviews with 25 employees working in domestic organizations in Russia. Below, we first report on the methodology and the results of our quantitative dataset and then turn to the qualitative one.

Study 1: a quantitative survey

Sample and data collection

We surveyed white-collar employees in 232 organizations located in Moscow and St Petersburg and operating in five industries (food processing, machine building, construction, metals, and finance). The targeted employees were subordinates of middle- or higher-level managers working in relatively large organizations (more than 500 employees). The data was collected using a telephone survey administered by a professional data collection agency in Russia. The original questionnaire was translated into Russian and then back-translated into English by two professional translators. The back-translated version was checked for any discrepancies by the authors. We pretested the Russian version of the instrument on five Russian native speakers living and working in Russia to ensure the understandability of the items.

965 employees were contacted, and we received responses from 403 of those (1.74 employees per organization) who agreed to participate in the survey for a small standard financial remuneration used by the agency. Thus, the obtained response rate was around 42%. The respondents were informed about the data collection’s purpose and their consent for participation was ensured. Their personal anonymity was guaranteed. The demographic characteristics of the respondents were as follows: The respondents’ average age was 36.3 (SD = 9.9), their average working hours per week was 41.3 (SD = 6.0), 35% of them were male and the respondents were equally divided between Moscow and St Petersburg (50% each).

Measures

All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (‘1’ - I do not agree at all and ‘5’—I fully agree) and are exhibited in Appendix A.

Independent variables

To measure HPWS, we adapted and abbreviated the instrument in Sun et al. (Citation2007) based on a combined consideration of the best loading items and the construct domain in previous research. We replaced Sun et al. (Citation2007) measures of performance appraisal with two items from Lepak and Snell (Citation2002) as performance evaluation in the present study was likely to depend on judgment rather than objective criteria. We also included a measure of the level of pay in line with extant research on HPWS (e.g. Lepak & Snell, Citation2002; Zhang et al., Citation2013). Finally, to avoid direct reference to leadership behaviors we removed the measures of ‘employee participation’ (Sun et al., Citation2007) from the present analyses. Our 17-item measure thus covered seven core high performance work practices: selection, training, pay, performance appraisal, job security, job opportunities and job description. Later, four items were removed due to their poor loadings (see Appendix B). This construct corresponds well to previous research (Cooke et al., Citation2019; García-Chas et al., Citation2014; Michaelis et al., Citation2015; Pak & Kim, Citation2018; Sanders et al., Citation2021).

TL was measured based on the instrument developed by Podsakoff et al. (Citation1990). We included nine items by considering the original construct domain and the validations in Podsakoff et al. (Citation1990, Citation1996), and MacKenzie et al. (Citation2001): three items for ‘core TL behaviors’ and two items each for ‘high performance expectations’, ‘individualized consideration’, and ‘intellectual stimulation’. One item was removed due to a poor loading (see Appendix A).

Individual power distance orientation was measured with three items based on Farh et al. (Citation2007) and Kirkman et al. (Citation2009).

Dependent variable

Constructive voice was measured with six items from Liang et al. (Citation2012), a construct validated in a high-PD context and comprising two dimensions, promotive and prohibitive voice respectively. We used the three best loading items for each dimension with good coverage of the construct domain.

Control variables

We controlled for employee gender (a dummy, 0 = male and 1 = female), age and tenure under the same supervisor (measured by interval scales), and employment opportunities (measured with four items taken from De Cuyper et al., [Citation2011]). Moreover, to provide more contextualization for our analysis, we also controlled for employee hierarchical position (a dummy, 0 = non-supervisory position and 1 = supervisory position), because employees who advance in their careers and themselves have subordinates are more likely to engage in voice behaviors (e.g. Wang et al., Citation2014); and organization’s historical roots (a dummy, 0 = established prior to 1991 and 1 = established after 1991), because Russia-specific research shows that the nature of employment relations in Russian organizations to some extent depends on what historical period they have been established (e.g. Balabanova et al., Citation2015).

Validation and analysis

The measurement model fitted our data well (Chi-square = 1271.472, df = 518, RMSEA = .060, NFI = .937). As shown in , the reliability and validity of the measures were confirmed. Each construct had Cronbach’s alpha and a composite reliability (CR) greater than .70. Also, the average variance extracted (AVE) was greater than or close to .50 and the squared correlations between the constructs were inferior to the associated AVE (e.g. Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Therefore, all the measures in our study were judged valid and reliable.

Table 1. Measurements’ validity.

Second, we tested for the presence of common method variance (CMV) using the unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) procedure (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003; Williams et al., Citation1989). In the ULMC procedure, a latent common factor, on which all indicators load, is specified. The model included all items of HPWS, TL, PDO, voice, and employment opportunities. The ULMC model yielded fit indices of somewhat inferior quality compared to the theoretical model (Chi-square = 1052.35, df = 479, RMSEA = .060, NFI = .871). In addition, the amount of variance attributed to the method construct was under the threshold of 25% (see Williams et al., Citation1989). This provides some evidence that CMV bias is not a major problem in our data but, as with all available post-hoc statistical remedies for detecting CMV, the ULMC technique has considerable weaknesses (Antonakis et al., Citation2010; Richardson et al., Citation2009). Importantly, however, recent evidence suggests that CMV is unlikely to be a serious threat for validity (Bozionelos & Simmering, Citation2022), and even less so in our study. We return to this issue in the limitations section.

Findings

Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations are shown in . HPWS and TL had a relatively high correlation (r = .59) but the examination of the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values revealed that this correlation did not cause multicollinearity between our variables (VIF < 2).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Models were estimated using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) regressions to take into account the nested structure of the data at the organizational level. The average number of observations from the same organization was 1.74. The intraclass correlation for employee constructive voice was .126, representing evidence of a ‘medium’ group-level effect (LeBreton & Senter, Citation2008, p. 839) whereby the assumption of independence for single-level regression analysis was violated. The dependent and independent variables were standardized, and all control variables were centered on the grand mean. The regression analyses proceeded in six steps (see below). The first model contained only the covariates age, gender, tenure, employment opportunity. In the two following models, TL and HPWS were entered separately into the models (Model 2-3). In the fourth step (Model 4), TL and HPWS were entered simultaneously. Then, the moderator PDO was added (Model 5). In the final model, the interaction terms TL x PDO and HPWS x PDO were entered (Model 6).

Table 3. Direct and moderated associations of HPWS and TL with voice – HLM estimates.

Table 3. Direct and moderated associations of HPWS and TL with voice – HLM estimates (continued).

Model 1 explained 20% of the variance in employee voice. Adding TL and HPWS further increased the explained variance (TL: 5%; HPWS: 9%). Both HPWS and TL had strong associations with employee voice (HPWS: β = .254, p < .001; TL: β = .186, p < .001) when considered independently. Thus, based on these analyses, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported as both the relationship between TL and voice and the one between HPWS and voice were significant, as we hypothesized. Model 4 where both TL and HPWS were entered simultaneously explained additional 9% of the variance in employee voice as compared to Model 1. Both TL and HPWS had significant relationships with employee voice however whereas the relationship between HPWS and voice remained strongly significant (HPWS: β = .215, p < .001), the one between TL and voice weakened (TL: β = .077, p < .05). Thus, we conclude that Hypothesis 5 was also supported as the relationship between TL and voice has weakened when TL and HPWS were entered simultaneously in Model 4. We also note that the additional explained variance by TL (Model 4) as compared to the model which only included the predictor HPWS (Model 3) was weak, i.e. 1%. In contrast, HPWS explained an additional 4% of the variance in constructive voice compared to the model where only the predictor TL was included (Models 2 and 4).

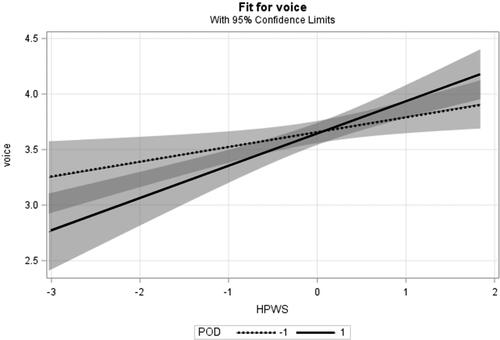

Employee PDO moderated only the association between HPWS and constructive employee voice (Model 6; the additional explained variance was 1.4% as compared to Model 5). In line with our expectation, the moderation was positive (β = .106, p < .001). An examination of the simple slopes obtained from Model 6 revealed that when PDO is high (i.e. +1 SD) there is a strong positive association γ = .299, p < .001), but when PDO is low (i.e. −1 SD) there is no association (γ = .119, p = .322) between HPWS and constructive voice (see ). Based on this, it could appear that HPWS does not have any effect on individuals with low PDO. However, this is because for low-PDO individuals the values of the interaction effect and the main effects are close to each other, producing the slope for low-PDO individuals that is near zero. The general effect is still there but enhanced for high-PDO individuals only. Thus, we found support for Hypothesis 4 in that PDO moderated the association between HPWS and constructive voice. Hypothesis 3 was not supported by our data.

Study 2: Post-hoc qualitative interviews

Sample and data collection

To better understand the reasons for the stronger relative importance of HPWS on employee constructive voice behaviour, we conducted an additional post hoc data collection in June-July 2022 with the help of research assistants who had experience in qualitative research. The interview guide was developed by the authors and the interviewers were briefed about the goals and objectives of the project. The interview guide was developed in English, translated into Russian and then back translated into English by two researchers who were native in Russian and professionally fluent in English. All discrepancies between the original and the back-translated English versions were jointly discussed and resolved. We used the Russian language version for the data collection.

We used a convenience sampling strategy to target full-time employees (employed for at least 6 months or more) in private sector Russian organizations with at least 100 employees. Both men and women of different ages were interviewed. The interviewees were recruited via the interviewers’ personal contacts and then using snowballing. Twenty-five semi-structured, in-person interviews lasting on average about 30 minutes were conducted in Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, and Perm. Appendix B provides detailed information about the interviews and the interviewees. In all interviews the interviewees were asked to think about whether they speak up and take initiatives at the workplace and if so then what drives them to do so. We also asked whether they see HRM practices existing at their workplace and TL behaviors of their proximal leader to influence such behaviors. Finally, in line with Dyer et al. (Citation2021), we presented the results of the quantitative analysis and asked the interviewees to suggest possible explanations for the results.

Qualitative results

Most interviewees reported that they engage in constructive voice behavior, at least episodically, mostly in relation to operational issues related to employees’ immediate duties: current tasks, the content, methods, and technologies of their work, or new projects. Besides ‘supportive’ suggestions and initiatives, employees also speak up to draw attention to problems, such as overwork or inefficiency of work processes.

Concerning TL and HRM as motivators or inhibitors of employee voice the interviewees acknowledged that both are important: Both company HRM and the behavior of managers are important for unlocking the potential of employees to be interested in the company success … and to put forward some ideas. And depriving them of any of these essential blocks … can reduce the quality of work, including their voice behavior (#6, male, 32, manufacturing). However, when asked about what motivates more strongly employee voice giving—TL or HRM—most interviewees responded that HRM comes first. When reflecting on our quantitative results, many interviewees noted that they recognize themselves in these results or have just thought exactly the same themselves and provided the following explanations.

According to our interviewees, people join organizations for meeting their material needs, and if they are satisfied with salary, working conditions and career perspectives, they stay in the organization and do their best at work, including engaging in constructive voice behaviors. below offers illustrative examples of such thinking among our interviewees.

Table 4. Comparison of the importance of HPWS and leadership for constructive voice.

The TL behavior of the immediate supervisor, although important, mainly provides socio-emotional rewards such as higher trust, respect, or team spirit, thus with a clear theory-based potential to influence voice behavior. However, in most organizations line managers are not responsible for employee financial rewards or working conditions such as career opportunities, which are defined at the company level, and which were deemed to be most important.

Reflecting on why individual PDO moderates the relationship between TL/HRM and employee voice, our interviewees suggested that employees with high PDO feel more dependent and vulnerable in organizations and thus experience more fear when expressing voice. They need more psychological safety and are more reactive and sensitive to signals of what is allowed in their organization. These silent workers are more dependent on [working] conditions [enabled through HRM], since they are unlikely to have much interaction with their boss and, accordingly, the main indicator of any praise for them will be improved working conditions [mainly referring to improved compensation, performance feedback and career opportunities] (#23, male, 24, education). Of course, for employees who unconditionally obey their supervisors, working conditions [as nurtured by HRM] are the key factor for voice, because otherwise they are not ready to negotiate with their superiors (#22, female, 32, education). Thus, our qualitative data also provides some direct support for our argumentation for the positive moderation effect of employee PDO on the relationship between HPWS and voice. It suggests that high-PDO employees are more dependent on effective HPWS, mainly providing motivational resources in the form of material benefits, career development and signaling their importance for the organization () as important external stimulus to motivate their constructive voice behaviors compared to their colleagues with lower PDO.

In summary, most of our interviewees offered support for our quantitative results by confirming the relatively more important role of HPWS as compared to TL for engaging in constructive voice behavior. The most common explanation of this effect fits into the ‘materialistic’ logic. This is also in line with previous research suggesting that financial and status-based aspects, including career opportunities, of work are considered the most important for Russian employees (Balabanova et al., Citation2016, Citation2022). While the specific aspects of HRM that are most important may vary across high-PD contexts, research suggests that the above applies more generally to employees in high-PD contexts (King & Bu, Citation2005; Tung & Baumann, Citation2009; Usugami & Park, Citation2006). HRM practices that provide motivational resources in the form of company-based ‘rules of the game’ and material rewards are perceived as more important for employee work-related behaviors in such contexts, including constructive voice behavior. Based on our interviews, also career opportunities contribute to this ().

Discussion

We set out to answer two specific research questions: 1) What is the unique and relative importance of TL and a HPWS for employee constructive voice behavior in a high-PD context. 2) How is this importance moderated by employee PDO? Below our answers to these questions and their implications.

Our study adds to the nascent research on employee voice facilitation in high-PD contexts (e.g. Duan et al., Citation2017; Hu & Jiang, Citation2018; Liang et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2015; Zhu & Akhtar, Citation2019) that has thus far focused predominantly on China, with a few notable exceptions (Duan et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2010), and on the role of more non-participative styles (e.g. Zhang et al., Citation2015). When considering TL and HPWS separately our findings in the still under-researched high-PD context of Russia are broadly in line with meta-analyses of previous independent research on the relationships between TL and constructive voice (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017). As long as we consider TL and HPWS separately, our study also confirms previous evidence of the emulation and mimicry of transformational leader behavior in high-PD contexts (Schaubroeck et al., Citation2007; Yang et al., Citation2010), and specifically evidence that such emulation is related to employee voice behavior (Duan et al., Citation2017). This highlights a contrast to authoritarian and paternalistic leadership styles which are not conducive to voice behavior, but which are prevalent in high-PD contexts (Chan, Citation2014; Li & Sun, Citation2015), including Russia (Kets de Vries, Citation2001; McCarthy et al., Citation2010). All these results also confirm earlier research suggesting not only positive associations between TL and employee attitudes in high-PD contexts, but more positive associations than in the case of authoritarian and paternalistic styles (Koveshnikov et al., Citation2020).

However, our competitive test (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010; Leavitt et al., Citation2010) of the relative importance of TL and HPWS puts all this research in some question, suggesting that the unique relationship between TL and voice behavior is relatively weak. It is noteworthy that including HPWS in the model reduces the relationship between TL and voice behavior by 62% while HPWS is reduced only by 15% when included in the same model with TL, and HPWS remains strongly significant. Our qualitative analysis also provides support for this by highlighting that material and status-related benefits in the form of career opportunities, salaries, bonuses, and other material rewards that are delivered through HRM are relatively more important for employees’ motivation to speak up at the workplace than their proximal leaders’ behaviors and actions. Based on the qualitative study, the relative importance of HRM is further enhanced by its role in determining the motivational ‘rules of the game’ which can guide employees. Overall, our results thus offer important evidence of the relative importance of two fundamental theorized antecedents to voice behavior, that is, leadership and organizational practices (Morrison & Milliken, Citation2000), and specifically help to increase our understanding of ‘important and unimportant antecedents’ to constructive voice behavior (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017, p. 34). Our quantitative analysis also offers methodological support for the importance of ‘direct empirical comparisons [that] can help establish which theory is superior in a given domain and force more precision in the theoretical arguments for the theory that fares less well’ (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010, p. 629).

Second, our results provide important tentative support for the later interpretation of leadership substitutes theory which posits that to a significant degree the influence of leaders occurs through ‘technological, structural, and other impersonal processes’ (Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997, p. 98) that are unrelated to the theorized influence of leadership which concerns the direct influence of pure interpersonal leadership behavior. This also provides some support for related arguments that there may be a potential ‘bias’ or ‘false assumption-making…regarding the relative importance of leadership factors [as we know them] to the functioning of groups and organizations’ (Meindl, Citation1995, p. 330). The fact that our study provides evidence for this in a hierarchical leader-centric high-PD context (Kets de Vries, Citation2001; McCarthy et al., Citation2010) is particularly interesting. It suggests an important general bias of omitted variables (Antonakis et al., Citation2010; Hill et al., Citation2021) in previous research focusing exclusively on leadership both generally (Banks et al., Citation2018) and across cultures (House et al., Citation2014). Our results specifically suggests that the ‘real significance’ of leaders may lie more in influencing the implementation (and perhaps co-creation) of the HRM system, which points to the importance of identifying new types of leader behaviors (Nishii & Paluch, Citation2018). With these results our study also extends previous research on the relative importance of leadership and HRM focusing on their respective independent main effects (Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2021) as a complement to the prevalent emphasis on their interaction effects (e.g. Hauff et al., Citation2022; Leroy et al., Citation2018; McClean & Collins, Citation2019).

Third, our study corroborates meta-analytic findings of the importance of HPWS for voice (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018) and related recent theorizations (Mowbray et al., Citation2021), while also extending them to a high-PD context. The theory of strong situations (Johns, Citation2006) suggests that the stronger the cultural context is, the more likely it is to impose strong behavioral norms that constrain or suppress the expression of individual differences and deviances from the larger situational norm (compare the role of cultural tightness in Farndale & Sanders, Citation2017). Support for this suppression effect of strong situations (Johns, Citation2006) can be found in the fact that PDO was not directly related to employee voice in our sample. The interaction effect between PDO and HPWS, complemented by our qualitative findings, suggests that the role of HPWS in fostering constructive voice behaviour becomes even more important when employees are most in need of support for their ability and motivation to speak up, as high-PDO employees in high-PD contexts arguably are (Hu & Jiang, Citation2018; Liang et al., Citation2012). This also offer further support for our argumentation that the main effect of HPWS is important in high-PD contexts. While this is in interesting contrast to previous arguments about the impact of PD (Farndale & Sanders, Citation2017; Sanders et al., Citation2021; Wu & Chaturvedi, Citation2009), it is in line with the argument and evidence that ‘gains from [HRM] practices that eliminate power inequality might be particularly high in high power distance cultures’ (Lin et al., Citation2020, p. 2848). In contrast, we did not find support for the hypothesized interaction between TL and PDO. One important explanation for this is offered by evidence suggesting that explicit leader voice expectations and transformational leadership in high power distance contexts is only correlated at .13 (Duan et al., Citation2017). Thus, even as TL can influence voice behavior in several ways, as we have argued, it appears that transformational leaders in high-PD contexts simply are not very strongly and explicitly signalling voice expectations, in particular not enough to specifically change the voice behaviors of high-PDO individuals. Another explanation is that TL is simply not as effective as HPWS in providing the resources that high-PDO individuals need to engage in voice behavior.

Finally, we note that in the present study we found no interactions effects of TL and HPWS, nor did we hypothesize that HPWS would mediate the relationship between TL and voice. This is because we were specifically interested in the main effects of HPWS and the interactional TL behaviors per se, as distinct from HPWS (Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997). If the effects of TL would indeed mainly, or even fully (Zhu et al., Citation2005), be mediated by HPWS, the conclusions would be that TL is important largely only to the extent it translates into HPWS. However, this is not what research on TL implies (Ng, Citation2017; Shamir et al., Citation1993). Also, research on HPWS does not imply that it is dependent on TL, or any other kind of extant leadership style (see Nishii & Paluch, Citation2018), but rather on the implementation of a set of practices themselves (Boon et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, one possible outcome of our study is that scholars do not accept the later interpretation of leadership substitute theory (Jermier & Kerr, Citation1997), combined with our arguments of the relative importance of the social exchange offered by TL and HPWS, as acceptable explanations of our results but are instead stimulated to engage in further theorizing their respective influence on organizational outcomes. This would also be in line with the argument that ‘conducting competitive tests’ between theories constitutes an important but neglected part of the ‘theory building process’ (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010, p. 620, 621).

Managerial implications

Our study has important and actionable managerial implications. It suggests that both HPWS and TL are powerful tools to improve the psychological workplace conditions of employees, and both are effective also in high-PD contexts. However, as in practice both HRM systems and leadership usually coexist in organizations, the key implication stemming from our study is that while TL can facilitate constructive voice behavior also in a high-PD context and specifically among Russian employees, progressive HPWS appears to be not only significantly more effective in doing this, but in particular so among those least prone to engage in voice behavior, i.e. employees with high PDO. This points to the strong transformative potential and importance of HPWS as a complement to leadership style, a transformative potential that organizations should be aware of and pay due attention to when they consider the investment of scarce resources in either leadership or HPWS development.

To this end, organizations interested in reaping the benefits of employees’ proactive behavior and initiative taking at the workplace are encouraged to prioritize the development of effective and trustful HRM systems to support and motivate employees to speak up and voice their ideas and concerns. Such systems are to be designed and developed keeping in mind the needs and expectations of employees in high-PD contexts. Hence, organizations would do well by emphasizing and focusing on material and status-related benefits that HRM systems can and should offer, such as career opportunities, salaries, bonuses, and possible other material rewards. Our study suggests that these are more important than the behaviors and actions of employees’ proximal leaders and thus need to be prioritized.

Relatedly, our results warn against generalizations concerning the cultural attributes of employees within the same cultural context, pointing instead to the need to pay due attention to within-culture variance. Organizations need to understand their employees’ expectations and beliefs. As our findings suggest, high-PDO employees require more support for their ability and motivation to speak up as compared to their low-PDO colleagues. Organizations are advised to collect data on employees’ cultural orientations such as, for instance, PDO to understand the extent to which effective HRM systems might be helpful in facilitating employee voice. Such data can be collected via short and focused pulse surveys or, if possible, included as part of regular wellbeing surveys.

Limitations and future research

Like any research, our study has important limitations. First, in our quantitative study, we used cross-sectional, single-source data. Readers therefore need to be cautious in making causal inferences based on our results. While cross-sectional data, just as lagged outcomes data and/or on multiple sources of data, all essentially allow only for correlational and non-directional conclusions, the most serious question concerns our single-source data and the CMV that it might give rise to, potentially leading to either upward or downward biases in the absolute correlations (Antonakis et al., Citation2010). However, although debated, recent evidence suggests that CMV is unlikely to be the commonly assumed threat to validity (Bozionelos & Simmering, Citation2022). Importantly, even if it is a threat, it is much less of a problem for our competitive hypothesis test concerning the relative importance of HPWS and TL as there is no reason to expect that CMV would apply differentially to the main effects of TL and HPWS (see e.g. Hill et al., Citation2021). Also, CMV cannot explain the significant interaction effect we identified (Siemsen et al., Citation2010). Thus, our core hypothesis tests should be relatively unbiased by CMV. We could have reduced potential biases in our data by asking supervisors to rate employee voice behavior (Liang et al., Citation2012). Supervisors do provide a different relevant perspective, and one less contaminated by, for example, potential social desirability bias included in employees’ own ratings of their voice behavior (see Steenkamp et al., Citation2010). Again, such bias should not differentially influence the relative importance of our independent variables. Further, supervisor ratings may also not be optimal as voice behavior to a significant degree can be directed towards peers, and the supervisor may thus not be the most knowledgeable informant of that behavior. Thus, while still pointing to caution in interpreting our results, we suggest that the self-rated constructive voice construct does have both strengths and weaknesses and, most importantly, as per the above that our data still allows us to meaningfully test our core hypotheses. In addition, while not removing doubts about single source bias, our post-hoc qualitative study helped us triangulate and support our quantitative analysis and thus further address doubts about their validity and credibility.

Further, while still acknowledging the remaining endogeneity-related weaknesses in our paper, including that of possible reverse causality (Wang et al., Citation2019) and potential measurement error (Hill et al., Citation2021), we address one important cause of endogeneity by simultaneously considering TL and HPWS, i.e. that of omitted variable bias (Antonakis et al., Citation2010; Hill et al., Citation2021). As noted by Antonakis, failure to control for ‘competing constructs will engender omitted variable bias and does not inform us of the incremental validity’ of a construct (2017, p. 14). We also note that Antonakis argues that ‘studies that report relations that are just “correlational”’ can still ‘have important implications for future research’ (Antonakis, Citation2017, p. 15). We argue that the present study is a case in point as it shows evidence for an important omitted variable bias in previous siloed research on TL, including an important substitution effect of HPWS and related theoretical and methodological contributions, as well as an interesting boundary condition for the increased importance of HPWS. All of these are important findings that should inform future research even as the absolute correlations may be biased due to our cross-sectional single source research design.

Second, our abbreviated measures may be a limitation. However, the correlations in our study fall within the confidence intervals in extant meta-analyses both with respect to TL and voice (Chamberlin et al., Citation2017) and HPWS and voice (Chamberlin et al., Citation2018), providing important evidence for the external validity of our measures (Stanton et al., Citation2002). Third, we used a construct of HPWS focused on ability- and motivation-enhancing practices (Mowbray et al., Citation2021), to the neglect of opportunity-enhancing practices (Harley, Citation2020). This may have led to underestimated associations between HPWS and voice behavior. Finally, our analysis is based on data from a single country, although exemplifying a theoretically interesting context that complements other one-country studies, not least those conducted in the context of China (e.g. Duan et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2010).

As for future research, the strongest and clearest implication of our study is the need for much more research simultaneously examining the effects of HRM systems and leadership (Leroy et al., Citation2018). Research extending and/or replicating this study of competing explanations of leadership and HRM, should consider tacit assumptions in terms of alternative ‘analytical procedures…, data-gathering approaches…, [and] operationalizations’ (Gray & Cooper, Citation2010, p. 626). However, we argue scholars should continue to collect data on both leadership and HRM from the same source to provide the most accurate comparisons of the two competing explanations, and not to confound the analyses by different perspectives on the two phenomena. Also, the role of PDO as a contextual moderator deserves more research given contrasting results in extant research (Daniels & Greguras, Citation2014; Duan et al., Citation2017; Lin et al., Citation2020; Wu & Chaturvedi, Citation2009). Finally, future research on these topics should increasingly strive to use more other analytical approaches and longitudinal and/or experimental research designs to begin to shed light on causal relationships (Antonakis et al., Citation2010; Hill et al., Citation2021).

Data availability statement

Data not available due to ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antonakis, J. (2017). On doing better science: From thrill of discovery to policy implications. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.01.006

- Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086–1120. [Database] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010

- Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Mondejar, R., & Chu, C. W. L. (2017). Core self-evaluations and employee voice behavior: Test of a dual-motivational pathway. Journal of Management, 43(3), 946–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314546192

- Au, K. Y. (1999). Intra-cultural variation: Evidence and implications for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(4), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490840

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Balabanova, E., Efendiev, A., Ehrnrooth, M., & Koveshnikov, A. (2015). Idiosyncrasy, heterogeneity and evolution of managerial styles in contemporary Russia. Baltic Journal of Management, 10(1), 2–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-03-2014-0039

- Balabanova, E., Efendiev, A., Ehrnrooth, M., & Koveshnikov, A. (2016). Job satisfaction, blat and intentions to leave among blue-collar employees in contemporary Russia. Baltic Journal of Management, 11(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-03-2015-0079

- Balabanova, E., Ehrnrooth, M., Koveshnikov, A., & Efendiev, A. (2022). Employee exit and constructive voice as behavioral responses to psychological contract breach in Finland and Russia: A within- and between-culture examination. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(2), 360–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1699144

- Banks, G. C., Gooty, J., Ross, R. L., Williams, C. E., & Harrington, N. T. (2018). Construct redundancy in leader behaviors: A review and agenda for the future. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.12.005

- Boon, C., Den Hartog, D. N., & Lepak, D. P. (2019). A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2498–2537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318818718

- Bozionelos, N., & Simmering, M. J. (2022). Methodological threat or myth? Evaluating the current state of evidence on common method variance in human resource management research. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(1), 194–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12398

- Budd, J. W., Gollan, P. J., & Wilkinson, A. (2010). New approaches to employee voice and participation in organizations. Human Relations, 63(3), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709348938

- Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 851–875. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0562

- Carl, D., Gupta, V., & Javidan, M. (2004). Power distance. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations (pp. 513–563). Sage.

- Chamberlin, M., Daniel, W., Newton, D. W., & LePine, J. A. (2017). A meta-analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: Identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 11–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12185

- Chamberlin, M., Newton, D. W., & LePine, J. A. (2018). A meta‐analysis of empowerment and voice as transmitters of high‐performance managerial practices to job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1296–1313. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2295

- Chan, S. C. (2014). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice: Does information sharing matter? Human Relations, 67(6), 667–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713503022

- Chang, E., & Hahn, J. (2006). Does pay‐for‐performance enhance perceived distributive justice for collectivistic employees? Personnel Review, 35(4), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610670571

- Cooke, F. L., Cooper, B., Bartram, T., Wang, J., & Mei, H. (2019). Mapping the relationships between high-performance work systems, employee resilience and engagement: A study of the banking industry in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), 1239–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1137618

- Crede, M., Jong, J., & Harms, P. (2019). The generalizability of transformational leadership across cultures: A meta-analysis. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(3), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2018-0506

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Daniels, M. A., & Greguras, G. J. (2014). Exploring the nature of power distance: Implications for micro- and macro-level theories, processes, and outcomes. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1202–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527131

- De Cuyper, N., Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Mäkikangas, A. (2011). The role of job resources in the relation between perceived employability and turnover intention: A prospective two-sample study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78(2), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.008

- Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183

- Duan, J., Li, C. W., Xu, Y., & Wu, C.-H. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: A Pygmalion mechanism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 650–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2157

- Dyer, J., Kryscynski, D., Law, C., & Morris, S. (2021). Who should become a business school associate dean? Individual performance and taking on firm-specific roles. Academy of Management Journal, 64(5), 1605–1624. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0555

- Ehrnrooth, M., & Bjorkman, I. (2012). An integrative HRM process theorization: Beyond signalling effects and mutual gains. Journal of Management Studies, 49(6), 1109–1135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01055.x

- Ehrnrooth, M., Barner‐Rasmussen, W., Koveshnikov, A., & Törnroos, M. (2021). A new look at the relationships between transformational leadership and employee attitudes—Does a high‐performance work system substitute and/or enhance these relationships? Human Resource Management, 60(3), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22024

- Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25530866

- Farndale, E., & Sanders, K. (2017). Conceptualizing HRM system strength through a cross-cultural lens. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1239124