Abstract

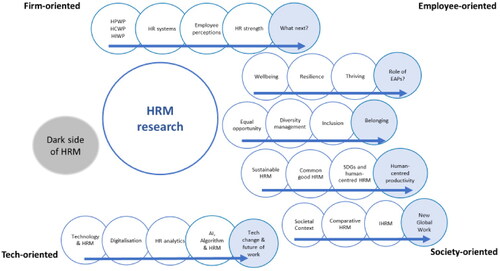

In this annual editorial for The International Journal of Human Resource Management, we project a vision of a sustainable ecosystem of human resource management (HRM) research by reflecting on key trends of HRM research and provide suggestions for future research efforts for the HRM research community. We outline the evolution and development of six areas of HRM research that are highly relevant to the policy and practice in the current global political-economic context. These research pursuits are shifting from firm-oriented and technology-oriented to becoming more employee-oriented and society-oriented. We extend these lines of enquiry with suggestions of what future research can examine to keep pace with practice and to offer policy and practical recommendations. We argue that different sub-fields of HRM research can complement, reinforce and interact with each other to enable us to build a robust and expanding research programme, intellectually and practically, to reflect the world of work and to demonstrate the relevance of our research to society with scientific rigour.

Introduction

This editorial extends our previous editorials in 2020 (Cooke et al., Citation2021) and 2021 (Cooke et al., Citation2022) by reflecting upon several key strands of research in the field of human resource management (HRM) in recent decades and highlighting several areas for future research attention. We note up front that these reflections of research achievements in the HRM field are indicative rather than exhaustive. Many important areas of achievements have been omitted in this editorial, partly because we want to highlight the areas in which we believe more research efforts are needed in response to current global realities of work, employment and people management. The world is witnessing some grand challenges and we need to conduct research from the perspectives of those who experience and make sense of them in order to understand and help provide HR support to overcome these challenges. In doing so, we reiterate a human-centred approach to HRM and continue to call for HRM research scholarship to be more practice-driven to enhance its relevance to business, community and society with policy and practical implications (Cooke et al., Citation2022).

We further call for the HRM research community to work together more closely to develop a sustainable ecosystem of HRM research. In the past 15 years or so, the term ecosystem has attracted growing attention from business and management researchers to refer to and examine different aspects of organisational life and, increasingly, their interactions (e.g. Granstrand & Holgersson, Citation2020; Mars et al., Citation2012; Mars & Bronstein, Citation2018; Roundy & Burke-Smalley, Citation2022). Organisational ecosystems are ‘emergent phenomena that result from a tenuous balance between actor agency and social structure, rather than from purposeful engineering’ (Mars et al., Citation2012, p. 274). For Mars et al. (Citation2012, p. 275). Organisational ecosystems ‘are nested structures’ that involve interactions amongst players, and the ‘degree of nestedness positively affects the resiliency of an organizational ecosystem’. Further, Granstrand and Holgersson (Citation2020, p. 1) define an innovation ecosystem as ‘the evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts, and the institutions and relations, including complementary and substitute relations, that are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors’.

We borrow these concepts and definitions to argue that HRM research is an (open) innovation system and its healthy ecology relies on the community’s voluntary but collective efforts in absorbing emerging phenomena and conducting research to make sense of them. By being more aware of the research ecosystem, the HRM research community can better develop complementary scholarly investigations from different disciplinary lenses, theoretical paradigms and methodological preferences and extend our knowledge in the HRM field. As we shall illustrate below, many sub-fields or strands, of HRM research can complement, reinforce and interact with each other to enable us to build a robust and expanding research programme, intellectually and practically, to reflect the world of work and to demonstrate the relevance of our research to society with scientific rigour.

What has been achieved and what more could be researched

Over the last three decades and particularly since the mid-2000s, the HRM research community has made significant achievements in advancing our understanding in relation to several lines of intellectual and empirical pursuits (see for example). Many of these have strong implications for employee wellbeing and productivity. They also illustrate the growing attention from HRM researchers to issues that have policy and societal impacts.

High-performance work practice, employee perception and HR system strength

As indicates that one of the chains of HRM research is in the area of high-performance work practices (HPWP), including high-commitment work practices (HCWP) and high-involvement work practices (HIWP) (e.g. Boxall & Macky, Citation2009; Chang et al., Citation2014; Esch et al., Citation2018; Fu et al., Citation2017), which has been extended to encompass HR systems (Nishii & Paluch, Citation2018), employee perceptions (Sanders et al., Citation2008) and HR system strength (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004, Chacko & Conway, Citation2019). This strand of research has developed significantly in its theoretical rigour and methodological nuances. Despite debates and criticisms (e.g. Kaufman, Citation2015; Troth & Guest, Citation2020), this body of scholarship provides a solid foundation for other stands of research to build on, not least because it has broadened its focus on firm performance towards employee perceptions, thus becoming more employee-oriented and context-sensitive. For example, drawing on social exchange theory and event system theory, Song et al. (Citation2022) develop a theoretical model to examine whether, how and when perceptions of HR system strength impact employee proactive behaviour during the Covid-19 pandemic crisis. The study found that HR system strength in times of crisis creates a strong situation by highlighting the HR’s function of caring and protecting employees’ well-being, which stimulates employees’ work engagement and subsequent proactive behaviours.

Employee wellbeing, resilience and thriving

A second important stream of research focuses on employees’ psychological wellbeing and its consequences, notably employee wellbeing (e.g. Guest, Citation2017), employee resilience (e.g. Cooke et al., Citation2019) and employee thriving at work (e.g. Spreitzer et al., Citation2012; Vu et al., Citation2022; Xu et al., Citation2019). This body of research examines the role of HRM practices and organisational support in promoting employees’ psychological wellbeing, accentuating the socially and workplace-embedded nature of such a psychological state. In the current climate of global crises in the form of a pandemic, financial challenges, military conflicts, technological rivalry, trade wars and international sanctions, organisations are operating with high levels of uncertainties and adversities. This makes it all the more critical for them to develop HRM interventions to support their employees to improve their wellbeing and resilience (Bondarouk et al., Citation2022) and to enable them to thrive at work. What organisational support do different groups of employees need? How can this be best provided? Under what conditions can employees thrive? There is much more we need to know: several special issues are on their way to advance our knowledge in this area (e.g. Bondarouk et al., Citation2022; Jiang et al., Citation2022). As Bondarouk et al. (Citation2022) pointed out, global crises challenge HRM researchers in relation to flexibility and resilience and accentuate the importance of our research (and the knowledge we create) on the wellbeing of the wider society in which we live and work.

A resilient and thriving workforce contributes to sustainable productivity. We particularly encourage HRM researchers to engage with research from an employee’s perspective to develop a more nuanced understanding of the nature of their work, their perception of HRM practices, expectations from their employers, career aspirations, emotional connections with peers, organisation and community and their suffering. Future research can also focus on specific groups of employees to generate more informed insights into their situations, expectations and needs. For instance, according to a study reported by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD, Citation2022), ‘men account for three-quarters of premature deaths from heart disease, are twice as likely to die from drug or alcohol abuse and three times more likely to die from suicide’ (CIPD, webpage information, no page number). Due to the cultural norm of masculinity and social expectations that men should be strong, men who face health problems are less likely than women to reach out for help. Given that a working-aged person spends a considerable number of hours at work, employing organisations have the opportunity to organise resources, including peer workers, to provide support to the employees who need assistance. How can organisations provide this support effectively? How can HRM researchers help to generate research knowledge to inform organisational practices? Here, HRM researchers can benefit from working with health researchers and those from other disciplines for more fruitful investigations.

The chain of research themes on employee wellbeing, resilience and thriving has a strong connection with the next one as individuals’ sense of wellbeing and ability to withstand challenges and to thrive are underpinned by their identity and sense of belonging, among other things.

Equality, diversity, inclusion, belonging and mindfulness

A third line of research enquiries is related to equality, diversity and inclusion (e.g. Donnelly, Citation2015; Ozturk & Tatli, Citation2016; Zanoni et al., Citation2010). Over the last three decades or so, this body of research has evolved from focusing on (in)equality and a rights-based argument (i.e. a social justice argument) to a more positive and inclusive approach to celebrating the diversity of the workforce and considering how to make effective use of the workforce diversity to maximise individuals’ talent and align it to achieve organisational goals (i.e. a business case argument). As a sub-strand of the literature, a growing number of positivist studies have been preoccupied with identifying the role of gender in leadership (e.g. female CEOs, the presence of females in the executive team) in organisational performance, including financial and social performance, R&D and corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Cooke, Citation2022).

An unintended consequence of this move towards a more ‘neutral/objective’ ground is that gender issues, and other diversity issues for that matter, are examined less and less often from a critical sociological and political economy perspective and more and more often from a strategic HRM angle aiming to convince organisational leaders why and how to mobilise female and other employees from underrepresented backgrounds for enhanced organisational performance (Kulik, Citation2022). This is not only misleading organisations that adopting diversity and inclusion policy and practice will pay off financially (which is possible but may not always be the case), but also overpromoting the business case at the expense of the social justice case as an employer obligation (Kulik, Citation2022).

Despite the availability of a substantial body of research on equality, diversity and inclusion, not all categories of minority employees (e.g. gender, age, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation and disability) have received equal research attention. What has been particularly under-researched in this cluster of research is workers with a disability, especially employees with neurodiversity, a condition which, it is estimated, some 15%–20% of the world population has (Doyle, Citation2020). Neurodiversity refers to a range of neuro-cognitive developmental conditions such as Autism-Spectrum Disorders, Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder, Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, Dyspraxia, Dyscalculia and Tourette Syndrome (Hennekam et al., Citation2022). It is argued that neurodiverse employees are not only a cohort of workers who need support but also a source of organisational competitive advantage (Hennekam et al., Citation2022). Therefore, more research efforts could be directed to advance our understanding of employees with disability and neurodiversity to create a more inclusive workplace and society.

In addition, belonging is another area that deserves further attention to keep pace with what is going on in the world situation and to extend this research chain. People’s cultural, ideological and political beliefs differ! International and national challenges such as strained public health funds, international sanctions and political conflicts bring to the fore and amplify differences in employees’ national, cultural and political identity which may be different from those that prevailed in the society and workplace. This is often not only a source of tension at home but also at workplaces. As shown in , the chain of equality, diversity and inclusion research is extending to belonging, a concept that remains difficult to define but is critical for improving individual employees’ sense of value and wellbeing at work (Randel et al., Citation2018). Within this, it would also be important to explore the intersectionality of belonging where individuals are part of diverse communities, such as when they are women and black or military veterans and neurodiverse. While the term belonging is relatively well-researched in other social science fields, it has attracted much less attention in the HRM field (e.g. McClure & Brown, Citation2008; Seriwatana & Charoensukmongkol, Citation2021). HRM research can extend efforts in these areas to elicit a deeper understanding of individual employees’ suffering and their emotional connections with peers, organisation and community, and what can be done to increase their sense of belonging, particularly minority employees and foster appropriate workplace behaviour.

Sustainable HRM, common-good HRM, SDGs and human-centred HRM and human-centred sustainable productivity

A fourth cluster of research interests is in the area of sustainable HRM (Kramar, Citation2014; Stahl et al., Citation2020) and more recently emerging research on common-good HRM (Matthews & Muller-Camen, Citation2020) and the role of human-centred HRM in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (see Cooke et al., Citation2022 for a summary). This strand of research, young and vibrant, has developed rapidly in a relatively short space of time and is gathering strong momentum as academic associations, universities and scholars are increasingly embracing the sustainability agenda and engaging in socially responsible research and education. However, this dynamic field of research is characterised by different conceptualisations of sustainable HRM and the way they are operationalised in empirical studies, with some focusing on green HRM and environmental outcomes (see Renee et al., Citation2021 for a review) whereas others are proposing a broader set of organisational practices and societal outcomes (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, Citation2020; Stahl et al., Citation2020).

We extend this line of enquiry by calling for more research attention on human-centred productivity. Labour productivity is critical to economic growth, especially in an uncertain and competitive environment (Bušelić & Pavlišić, Citation2016). Traditionally, HRM research has focused relatively narrowly on individual, team and organisational performance. By contrast, governments have been facing the challenge of developing effective policy interventions to improve labour productivity. In Australia, for example, increasing labour productivity through higher wages is part of the discussion in the post-COVID economic recovery (Workplace Express, Citation2022). In the UK, a study found that 29% of the UK workforce—which equates to an estimated 8.2 million people—felt that the cost of living-related financial worries had negatively impacted their productivity at work and they were not receiving sufficient support from their employer (Howlett, Citation2022).

Although labour productivity is notoriously difficult to measure, existing studies have found that certain types of HRM practices, such as human capital investment (e.g. skill training), improvement in labour standards and provisions of employee welfares, are beneficial to/associated with enhancing labour productivity especially in developing countries like China (e.g. Budd et al., Citation2014). There are ample opportunities for HRM researchers to broaden their research on firm performance and employee productivity by collaborating with researchers from other disciplines, for example labour economics, to tackle productivity issues from different disciplinary perspectives, industry lenses and firm ownership angles. Studies can also examine the societal effects and the two-way relationships between firm productivity and societal wellbeing, including living standards of those in lower skill jobs.

The pursuit of firm-level productivity enhancement should also take into account the notion of sustainable productivity at the societal level, as part of corporate social responsibility. For example, the disposal of waste materials in the construction industry can be time-consuming due to differentiated sorting and transporting. Construction workers may not have the incentive to spend time engaging with recycling activities. How can incentives be created for companies and workers, for instance in the construction industry, to take greater responsibility for environmental performance?

New patterns to organize, conduct, experience and (self-)determine global work

A fifth cluster investigates global work. Comparative HRM focuses on the exploration of diverse employment contexts in different countries and their effects. Work on national business systems (Whitley, Citation1992) and varieties of capitalism approaches (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001) has analysed a broad range of societal structures, interdependencies and outcomes. The arguments have been highly influential so that further conceptualization and research has refined our understanding, for instance by identifying further categories beyond Liberal Market Economies and Coordinated Market Economies such as Mediterranean Market Economies and Hierarchical Market Economies (Amable, Citation2003; Schneider & Soskice, Citation2009). How context shape HRM policies and practices in organizations are the focal point of the long-established ‘CRANET’ Network that has surveyed senior HR professionals around the world since 1989 (Brewster et al., Citation2011; Parry et al., Citation2011). We would like to encourage research efforts that expand our contextual understanding. One way forward would be work that concentrates on sub-areas of HRM. For instance, the 5 C Consortium explores comparative career patterns around the world (Mayrhofer et al., Citation2020) providing valuable insights into careerists’ journeys that are embedded in diverse national and occupational contexts. Research that informs and nuances our understanding of talent sourcing, talent management or performance management (see, for instance, Vaiman et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b) and their interactions with and relationships to organizational and societal approaches would be welcome, adding to the rich studies already existing in the international employment relations field.

International HRM often explores global HR strategies, structures, policies and practices of multinational enterprises (Dickmann & Müller-Camen, Citation2006; Farndale et al., Citation2010). Given multiple developments, such as in terms of industry patterns (Malik et al., Citation2021); social movements and competitive strategies (Pacheco and Dean Citation2015), collective representation and voice, worldwide market opportunities, corporate restructuring affecting intra-company power distributions (to name but a few), the field embodies many research opportunities that may explore the complex interdependencies within different national units, functions and stakeholders in internationally operating organizations.

The world is rapidly moving into a state in which countries, medical systems and people have learned how to live with Covid-19. Many articles have outlined how the pandemic has accelerated technical developments and has led to workers being more capable and comfortable using technology and engaging in virtual work albeit not without some struggle (Adamovic et al., Citation2022). Virtual global work—replacing personal physical international interactions—is growing rapidly and is associated with a host of advantages, even though there are some disadvantages and barriers (Selmer et al., Citation2022).

These trends have a range of implications for individuals, their competencies and global career patterns that would be worthy of exploration. It seems likely that individuals have gained more autonomy to shape their global work. For instance, international assignments that meant sending workers on a foreign sojourn into a host country might now be (largely) done remotely, with individuals deciding when and for how long to stay—or merely to travel on international business journeys—in the host country. In contrast, there are now various reports of ‘workations’ where persons (with or without their families) extend a holiday to work from abroad with their home country teams for employees to be more productive. This ‘on-demand’ foreign work—assuming that the employers are open to such flexibility and organizations/individuals can overcome potential legal and work permit issues—and the potential to hybridize global assignments means that a huge variety of underexplored patterns are emerging. Long-standing issues of academic interests harbour a range of research opportunities. For instance, how do the relatively new global work patterns influence individuals’ identities, their adjustment patterns or the competencies they acquire? What will this mean for their performance or careers? In turn, what consequences may this have for organizations in terms of their approaches to global talent management, job and organizational engagement or their international employee value proposition? Indeed, with the number of virtual meetings mushrooming, how can organizations help individuals to gain the necessary global competencies to run effective cross-cultural meetings? What impact may all of this have on the intra-organizational power distribution and overall culture of multinational enterprises? How will issues in relation to compliance with local laws, regulations and national business systems be handled? How will diversity, equality and inclusion or sustainable HRM be affected? These are only a few of the issues that merit renewed and closer inspection.

Technology, digitalisation, HR analytics, AI, algorithm and HRM

A sixth strand of research relates largely to the impact of technological advancement on work, the workforce and HRM. Research here has largely focused on the use of different technologies for managing people and has tracked the advancements in the technologies available, from human resource information systems (HRIS) (e.g. Ball, Citation2001; Dery et al., Citation2013; Tansley & Watson, Citation2000), to e-HRM (e.g. Strohmeier, Citation2009; Bondarouk et al., Citation2009; Bondarouk & Brewster, Citation2016) social media (e.g. Martin et al., Citation2015) and more recently, technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) (Pan et al., Citation2022; Vrontis et al., Citation2022) and the internet of things (Strohmeier, Citation2020). Surprisingly perhaps, only a relatively small number of these papers focuses on the impact of these technologies on employees, most commonly examining employee satisfaction with e-HRM systems (e.g. Bissola & Imperatori, Citation2013; Bondarouk et al., Citation2009). Instead, authors have chosen to focus on the implementation of HRM technology (e.g. Burbach & Royle, Citation2014) or how the use of HRM technology affects the HR function itself by making it more efficient, effective or allowing it to have a more strategic role (e.g. Bondarouk et al., Citation2017; Marler & Fisher, Citation2013; Marler & Parry, Citation2016; Parry & Tyson, Citation2011; Parry, Citation2011). While more effective use of HRM technology might have beneficial effects for employees, we argue here that a more human-centred approach to examining digital approaches to HRM could be taken, in order to fully understand how these might impact individuals’ job-related attitudes, wellbeing and productivity.

More recently, the literature has moved to focus on the use of data, as an output of HR technology, and specifically on HR and people analytics (e.g. Marler & Boudreau, Citation2017). While this literature is growing, it is still nascent and focused primarily on how and why people analytics can be used within organisations rather than on the impact or outcomes of these approaches. The use of AI and algorithms as extensions of people analytics, and implications of these for HRM, as well as the impact of digital-based technological changes on the workforce in traditional industries have not yet been adequately researched, with the exception of the growing literature on algorithmic management. In contrast to the substantial research interest in the 1980s–1990s on the impact of technological change on the skill and employment of manual workers, research on technology in recent years tends to focus on gig workers, service industries and the role of digital technology in HRM. At the same time, the development and deployment of digital technology and industry-based business responses in part to address environmental concerns and productivity issues are having considerable implications on the workforce and the future of work in terms of skills and employment outlooks. These implications are not only societal but also industry-specific and specific to occupations within industries.

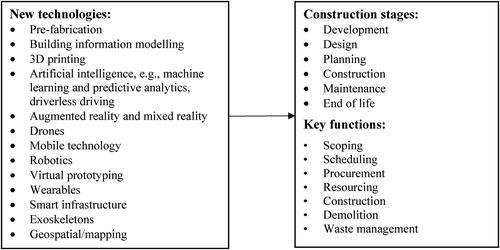

For example, the construction industry, again, which is one of the largest industrial sectors in most countries, is undergoing some major technological changes with implications for different occupational categories from architects and project managers to manual skilled workers (see for illustration). Some construction companies are taking a more radical step than others in embracing new technology in building design, utilisation, maintenance and decommissioning as a response to workforce ageing, skill shortages, labour relations problems, climate change, energy transition and responsible consumption of materials. Although many governments have provided post-COVID investment in infrastructure building to reboot the economy, radical technological change is necessary to improve the productivity of the construction industry but this remains a major challenge for many firms (Belman et al., Citation2021). How do technological changes impact different categories of the workforce in the construction industry and their future of work? How can HRM contribute to improving labour productivity and industrial relations of the industry?

The automotive industry is another example of an industry that is undergoing transformations in vehicle design such as the transition from fuel vehicles to electric vehicles. Companies in this industry are facing skill shortages in transitioning to the new product and production paradigm. Some are displacing workers on the one hand but are recruiting (digitally-enabled) workers on the other. Implications for HRM practice may include, for example, developing a skilled workforce that possesses skills for the digital future of work; developing HRM practices to enable the workforce to have sustainable employment and firms and nations to have sustainable productivity; developing innovative HRM strategy and practice to support the digital transition/transformation of work; and partnership with trade unions to improve employment/industrial relations.

We therefore call for more industry-based research that will help address industry-related problems and generate insights that may be relevant for other industries. Focusing on industries as the context for scholarly investigation also has the potential to provide tailored policy recommendations that may require coordinated actions from different stakeholders or institutional actors at various levels, thus creating research impacts. That said, many of the issues confronting traditional industries are shared across different parts of the world. As such, research insights and lessons learned from one country or region may provide useful reference points for others.

The dark side of HRM and ethics research in HRM

The dark side of HRM, often seen as the negative effect of HRM practices on the workforce, is another emerging area of research interest. For example, Jensen and Van De Voorde (Citation2016) examine the negative impact of high-performance work systems on employees’ health. Talukdar and Ganguly (Citation2022) study investigates the dark side of e-HRM and how this can be mitigated. Chatterjee et al. (Citation2022) examine the dark side of HR analytics, particularly the privacy of employees.

Much of the research on the dark side of HRM has been conducted from the lens of how organisational practices have had negative consequences, intended and unintended, on employees. Equally, extant research on ethics and HRM has mainly investigated the unethical practices of employers, and what HRM practices and leadership styles will elicit ethical behaviours from employees, such as organisational citizenship behaviours. By contrast, much less attention has been directed to employees’ unethical behaviours and the motives underpinning such behaviours. These include, for example, persistent incidences of police overreacting in the USAFootnote1, workplace bullying and abusive behaviours, theft (materials and time), taking shortcuts and providing shoddy work. Future research can shed light on these issues and other forms of unethical behaviours from employees to understand what drives these behaviours and what works to reduce these behaviours.

Conclusions

There is much to celebrate in the rich body of HRM research scholarship that has cumulated over the last three decades or so. Researchers have been entrepreneurial in extending the frontiers of research topics through new intellectual angles, improved methodological rigour and novel empirical insights in expanding contexts. This has laid a very solid foundation for us to organise our research efforts in a concerted way that would help us develop a sustainable ecosystem of HRM research, by developing a human-centred HRM research programme to understand and inform policy and practice in different political, economic, social and technological contexts. Such an ecosystem requires the HRM research community to identify key themes and issues that are confronting workers, businesses and policy makers and address grand challenges through actionable research and thought leadership. It also requires the HRM research community to be interested in phenomena not familiar to our own daily life and society—which may have broader research and practical implications; be willing to listen to narratives from other parts of the world, which may be very different from ours, yet to be told and to be shared; and be willing to learn and disseminate new ideas, insights and ways of thinking. In other words, we need to adopt a pluralistic and inclusive view. Each society has its own systems, traditions, cultural values, sentiments, narratives and stories. They have their own merits and legitimacies that make society function and malfunction. Any research aiming to help those societies and firms operating within them to improve their functioning needs to, first, understand these systems, traditions, values and narratives before advice is given. In sum, together, the HRM research community can strive towards a bigger vision and a broader playing field for HRM research, transforming itself from engaging in HRM research in the world to HRM research for a better world creatively, collaboratively and inclusively.

Monash Business School, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

[email protected] Michael Dickmann and Emma Parry

School of Management, Cranfield University, Bedfordshire, UK

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgment

Fang Lee Cooke would like to acknowledge that part of this article draws on her keynote speech for the 12th Biennial International Conference of the Dutch HRM Network ‘HRM for Resilient Societies: A Call for Actionable Knowledge’ that took place during 9-11 November 2022 at the University Twente, The Netherlands. The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged through the Digital Futures at Work Research Centre (grant no. ES/S012532/1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 This came from a comment by Professor Arch Woodside in the research symposium on ethics jointly organised by Symphonya: Emerging Issues in Management and Niccolò Cusano University in Rome on 27 October 2022.

References

- Adamovic, M., Gahan, P., Olsen, J., Gulyas, A., Shallcross, D., & Mendoza, A. (2022). Exploring the adoption of virtual work: The role of virtual work self-efficacy and virtual work climate. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(17), 3492–3525. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1913623

- Amable, B. (2003). The diversity of modern capitalism. Oxford University Press.

- Ball, K. S. (2001). The use of human resource information systems: A survey. Personnel Review, 30(6), 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005979

- Belman, D., Druker, J., & White, G. (2021). Work and Labor relations in the construction industry: An international perspective. Routledge.

- Bissola, R., & Imperatori, B. (2013). Facing e-HRM: The consequences on employee attitude towards the organisation and the HR department in Italian SMEs. European Journal of International Management, 7(4), 450–468.

- Bondarouk, T., & Brewster, C. (2016). Conceptualising the future of HRM and technology research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(21), 2652–2671. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1232296

- Bondarouk, T., Parry, E., & Furtmueller, E. (2017). Electronic HRM: Four decades of research on adoption and consequences. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 98–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1245672

- Bondarouk, T., Ruel, H., & Van der Heijden, B. (2009). e-HRM effectiveness in a public sector organization: A multi-stakeholder perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(3), 194–202.

- Bonadarouk, T., Renkema, M., Khapova, S., & van Dierendonck, D. (2022). Special Issue Call for Papers: HRM for resilient societies: A call for actionable knowledge. The International Journal of Human Resource Management.

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203–221.

- Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2009). Research and theory on high-performance work systems: Progressing the high-involvement stream. Human Resource Management Journal, 19(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2008.00082.x

- Brewster, C., Mayrhofer, W., & Reichel, A. (2011). Riding the tiger? Going along with Cranet for two decades—A relational perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 21(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.09.007

- Budd, J. W., Chi, W., Wang, Y., & Xie, Q. (2014). What do unions in China do? Provincial-level evidence on wages, employment, productivity, and economic output. Journal of Labor Research, 35(2), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9178-4

- Burbach, R., & Royle, T. (2014). Institutional determinants of e-HRM diffusion success. Employee Relations, 36(4), 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2013-0080

- Bušelić, M., & Pavlišić, P. (2016). Innovations as an important factor influencing labour productivity in the manufacturing industry. Ekonomski vjesnik: Review of Contemporary Entrepreneurship, Business, and Economic Issues, 29(2), 405–420.

- Chacko, S., & Conway, N. (2019). Employee experiences of HRM through daily affective events and their effects on perceived event-signalled HRM system strength, expectancy perceptions, and daily work engagement. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(3), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12236

- Chang, S., Jia, L., Takeuchi, R., & Cai, Y. (2014). Do high-commitment work systems affect creativity? A multilevel combinational approach to employee creativity. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035679

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., Vrontis, D., & Siachou, E. (2022). Examining the dark side of human resource analytics: an empirical investigation using the privacy calculus approach. International Journal of Manpower, 43(1), 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-02-2021-0087

- CIPD. (2022). CIPD Podcast 189—Men’s health at work: Are organisations doing enough? https://www.cipd.co.uk/podcasts?utm_source=mc&utm_medium=email&utm_content=cipdupdate_09112022.EdL1_Podcast+Men%26amp%3b%23x27%3bs+Health&utm_campaign=cipd_update&utm_term=1099866

- Cooke, F. L. (2022). Changing lens: Broadening the research agenda of women in management in China. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05105-1

- Cooke, F. L., Cooper, B., Bartram, T., Wang, J. and Mei, H. X. (2019). ‘Mapping the relationships between high-performance work systems, employee resilience and engagement: A study of the banking industry in China’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(1), 1239–1260.

- Cooke, F. L., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2021). IJHRM after 30 years: Taking stock in times of COVID-19 and looking towards the future of HR Research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1833070

- Cooke, F. L., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2022). Building sustainable societies through human-centred human resource management: Emerging issues and research opportunities. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.2021732

- Dery, K., Hall, R., Wailes, N., & Wiblen, S. (2013). Lost in translation? An actor-network approach to HRIS implementation. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 22(3), 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2013.03.002

- Dickmann, M., & Müller-Camen, M. (2006). A typology of international human resource management strategies and processes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(4), 580–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190600581337

- Donnelly, R. (2015). Tensions and challenges in the management of diversity and inclusion in IT services multinationals in India. Human Resource Management, 54(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21654

- Doyle, N. (2020). Neurodiversity at work: A biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. British Medical Bulletin, 135(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa021

- Esch, V. E., Wei, L. Q., & Chiang, F. F. T. (2018). High-performance human resource practices and firm performance: The mediating role of employees’ competencies and the moderating role of climate for creativity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(10), 1683–1708. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1206031

- Farndale, E., Paauwe, J., Morris, S. S., Stahl, G. K., Stiles, P., Trevor, J., & Wright, P. M. (2010). Context-bound configurations of corporate HR functions in multinational corporations. Human Resource Management, 49(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20333

- Fu, N., Flood, P. C., Bosak, J., Rousseau, D. M., Morris, T., & O'Regan, P. (2017). High-performance work systems in professional service firms: Examining the practices-resources-uses-performance linkage. Human Resource Management, 56(2), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21767

- Granstrand, O., & Holgersson, M. (2020). Innovation ecosystems: A conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation, 90–91, 102098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098

- Guest, D. E. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 22–38.

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). An introduction to varieties of capitalism. In P. A. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–68). Oxford University Press.

- Hennekam, S., Volpone, S., & Pullen, A. (2022). Neurodiversity at work: Challenges and opportunities for human resource management. Human Resource Management, Special Issue Call for Papers, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/pb-assets/assets/1099050X/HRM_CfP_Neurodiversity%20at%20Work-1665484904.pdf.

- Howlett, E. (2022). Eight million employees have low productivity as a result of the cost of living crisis, study finds. https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1805565/eight-million-employees-low-productivity-result-cost-living-crisis-study-finds?bulletin=pm-daily&utm_source=mc&utm_medium=email&utm_content=PM_Daily_17112022.https%3a%2f%2fwww.peoplemanagement.co.uk%2farticle%2f1805565%2feight-million-employees-low-productivity-result-cost-living-crisis-study-finds%3fbulletin%3dpm-daily&utm_campaign=7295441&utm_term=1099866.

- Jensen, J. M., & Van De Voorde, K. (2016). High performance at the expense of employee health? Reconciling the dark side of high performance work systems. In Understanding the high performance workplace (pp. 81–102). Routledge.

- Jiang, Z., Xu, A., Wu, C. H., & van de Voorde, K. (2022). Enabling a thriving workforce: Human resource management perspectives. Human Resource Management, Call for Papers, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/pb-assets/assets/1099050X/HRM_CfP_Enabling%20a%20Thriving%20Workforce-1658770051627.pdf.

- Kaufman, B. E. (2015). Evolution of strategic HRM as seen through two founding books: A 30th anniversary perspective on development of the field. Human Resource Management, 54(3), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21720

- Kramar, R. (2014). Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(8), 1069–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.816863

- Kulik, C. (2022). Gender (in)equality in Australia: Good intentions and unintended consequences. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 60(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12312

- Liu, X. Q., Zhang, K. P., & Ren, Y. Y. (2022). Does climate warming affect labour productivity in emerging economies?—Evidence from Chinese-listed firms. Applied Economics, 1–14.

- Lopez-Cabrales, A., & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2020). Sustainable HRM strategies and employment relationships as drivers of the triple bottom line. Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100689

- Malik, A., Pereira, V., & Budhwar, P. (2021). HRM in the global information technology (IT) industry: Towards multivergent configurations in strategic business partnerships. Human Resource Management Review, 31(3), 100743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100743

- Marler, J. H., & Boudreau, J. W. (2017). An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244699

- Marler, J. H., & Fisher, S. L. (2013). An evidence-based review of e-HRM and strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 23(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.06.002

- Marler, J. H., & Parry, E. (2016). Human resource management, strategic involvement and e-HRM technology. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(19), 2233–2253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1091980

- Mars, M. M., & Bronstein, J. L. (2018). The promise of the organizational ecosystem metaphor: An argument for biological rigor. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(4), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617706546

- Mars, M. M., Bronstein, J. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2012). The value of a metaphor: Organizations and ecosystems. Organizational Dynamics, 41(4), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.08.002

- Martin, G., Parry, E., & Flowers, P. (2015). Do social media enhance constructive employee voice all of the time or just some of the time? Human Resource Management Journal, 25(4), 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12081

- Matthews, B., & Muller-Camen, M. (2020). Common good HRM: A paradigm shift in Sustainable HRM? Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100705.

- Mayrhofer, W., Smale, A., Briscoe, J., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2020). Laying the foundations of international careers research. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12295

- McClure, J. P., & Brown, J. M. (2008). Belonging at work. Belonging at Work, Human Resource Development International, 11(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860701782261

- Nishii, L. H., & Paluch, R. M. (2018). Leaders as HR sensegivers: Four HR implementation behaviors that create strong HR systems. Human Resource Management Review, 28(3), 319–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.02.007

- Ozturk, M. B., & Tatli, A. (2016). Gender identity inclusion in the workplace: Broadening diversity management research and practice through the case of transgender employees in the UK. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(8), 781–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1042902

- Pacheco, D. F., & Dean, T. J. (2015). Firm responses to social movement pressures: A competitive dynamics perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 36(7), 1093–1104.

- Pan, Y., Froese, F., Liu, N., Hu, Y., & Ye, M. (2022). The adoption of artificial intelligence in employee recruitment: the influence of contextual factors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(6), 1125–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1879206

- Parry, E., & Tyson, S. (2011). Desired goals and actual outcomes of e-HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(3), 335–354.

- Parry, E. (2011). An examination of e-HRM as a means to increase the value of the HR function. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(5), 1146–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.556791

- Parry, E., Stavrou-Costea, E., & Morley, M. J. (2011). The Cranet international research network on human resource management in retrospect and prospect. Human Resource Management Review, 21(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.09.006

- Randel, A. E., Galvin, B. M., Shore, L. M., Ehrhart, K. H., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., & Kedharnath, U. (2018). Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.002

- Renee, P., Holland, P., & Morgan, D. (2021). A meta-review of 10 years of green human resource management: Is Green HRM headed towards a roadblock or a revitalisation?. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59(2), 159–183.

- Roundy, P. T., & Burke-Smalley, L. (2022). Leveraging entrepreneurial ecosystems as human resource systems: A theory of meta-organizational human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 32(4), 100863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2021.100863

- Sanders, K., Dorenbosch, L., & de Reuver, R. (2008). The impact of individual and shared employee perceptions of HRM on affective commitment: Considering climate strength. Personnel Review, 37(4), 412–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480810877589

- Schneider, B. R., & Soskice, D. (2009). Inequality in developed countries and Latin America: Coordinated, liberal and hierarchical systems. Economy and Society, 38(1), 17–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140802560496

- Selmer, J., Dickmann, M., Froese, F. J., Lauring, J., Reiche, B. S., & Shaffer, M. (2022). The potential of virtual global mobility: Implications for practice and future research. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-07-2021-0074

- Seriwatana, P., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2021). Cultural intelligence and relationship quality in the cabin crew team: The perception of members belonging to cultural minority groups. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 20(2), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2020.1821431

- Song, Q., Guo, P. Q., Fu, R., Cooke, F. L., & Chen, Y. (2022). Does human resource system strength help employees act proactively? The roles of crisis strength and work engagement. Human Resource Management, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hrm.22145. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22145

- Spreitzer, G., Porath, C. L., & Gibson, C. B. (2012). Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Organizational Dynamics, 41(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2012.01.009

- Stahl, G. K., Brewster, C. J., Collings, D. G., & Hajro, A. (2020). Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Human Resource Management Review, 30(3), 100708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100708

- Strohmeier, S. (2009). Concepts of e-HRM consequences: A categorisation, review and suggestion. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(3), 528–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802707292

- Strohmeier, S. (2020). Smart HRM: A Delphi study on the application and consequences of the internet of things in human resource management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(18), 2289–2318. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1443963

- Talukdar, A., & Ganguly, A. (2022). A dark side of e-HRM: Mediating role of HR service delivery and HR socialization on HR effectiveness. International Journal of Manpower, 43(1), 116–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2021-0038

- Tansley, C., & Watson, T. (2000). Strategic exchange in the development of Human Resource Information Systems (HRIS). New Technology, Work and Employment, 15(2), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00068

- Troth, A., & Guest, D. (2020). The case for psychology in HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12237

- Vaiman, V., Sparrow, P., Schuler, R., & Collings, D. G. (2019b). Macro talent management in emerging and emergent markets: A global perspective. Routledge.

- Vaiman, V., Sparrow, P., Schuler, R., & Collings, D. G. (2019a). Macro talent management: A global perspective on managing talent in developed markets. Routledge.

- Vrontis, D., Christofi, M., Pereira, V., Tarba, M. A., & Trichina, E. (2022). Artificial intelligence, robotics, advanced technologies and human resource management: A systematic review. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(6), 1247–1266.

- Vu, T.-V., Vo-Thanh, T., Chi, H., Nguyen, N. P., Nguyen, D. V., & Zaman, M. (2022). The role of perceived workplace safety practices and mindfulness in maintaining calm in employees during times of crisis. Human Resource Management, 61(3), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22101

- Whitley, R. (Ed.). (1992). European business systems: Firms and markets in their national contexts. Sage.

- Workplace Express. (2022). https://www.workplaceexpress.com.au/nl06_news_selected.php?act=2&nav=10&selkey=61364&utm_source=instant+email&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=subscriber+email&utm_content=read+more&utm_term=BCA%20chief%20champions%20%22high%20wage%2C%20high%20productivity%22%20economy.

- Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Chow, C. W. C. (2019). What threatens retail employees’ thriving at work under leader-member exchange? The role of store spatial crowding and team negative affective tone. Human Resource Management, 58(4), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21959

- Zanoni, P., Janssens, M., Benschop, Y., & Nkomo, S. (2010). Guest editorial: Unpacking diversity, grasping inequality: Rethinking difference through critical perspectives. Organization, 17(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508409350344