?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study uses proactivity and play theories to investigate playful work design – the personal initiative to change the psychological experience of work by redesigning work activities to be more fun and/or more competitive. We postulate that playful work design is positively related to job performance through work engagement. In addition, we hypothesize that this indirect relationship is positively moderated by boredom and negatively moderated by conscientiousness. To test these hypotheses, we conducted a two-wave study among 370 Israeli employees (response = 84%), with one month in-between both measurement waves. Consistent with hypotheses, results of mediation analyses showed that playful work design in the form of designing competition (but not designing fun) was indirectly and positively related to both in-role and extra-role performance, through work engagement. As predicted, the indirect effects of designing fun (but not designing competition) on in-role and extra-role performance were strongest for individuals who reported high (vs. low) levels of boredom. In addition, the indirect relationships of designing competition (but not designing fun) with in-role and extra-role performance through work-engagement were stronger for individuals who reported lower (versus higher) levels of conscientiousness. We discuss how these findings contribute to the theory and practice of playful work design.

Self-initiated play is a hallmark of human behavior since the dawn of history. Autonomous play behaviors can be considered as developmental milestones children are expected to attain (Piaget, Citation1951), characterize adolescents’ interactions (Verheijen et al., Citation2020), and are even indicative of healthy adult adjustment (Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015). Indeed, play has been a topic of intensive inquiry in various disciplines, ranging from developmental and evolutionary psychology to anthropology, archeology, and animal behavior. The quest for self-initiated play in adult leisure time is abundant, as is evident by thriving gaming and sports industries. It is therefore surprising that the concept of self-initiated play has received little research attention in the vocational and organizational behavior/psychology literatures (for exceptions, see Abramis, Citation1990; Mainemelis & Ronson, Citation2006).

This state of affairs can be contrasted with the somewhat more often studied concept of other-initiated play at work (Celestine & Yeo, Citation2021), according to which play may be initiated by management, supervisors, or peers. Examples include encouraging employees to utilize toys (such as structured play sessions with LEGO bricks) in their work to inspire imagination and innovation (Roos et al., Citation2004), organizing playful outings for personnel (Tews et al., Citation2012), or gamifying work procedures by infusing employees with competition and rewards (e.g. Deterding et al., Citation2011).

Recently, Scharp et al. (Citation2019; Bakker et al., Citation2020) argued that the autonomous pursuit of self-initiated play may extend to the workplace. They coined the concept of playful work design (PWD)—individuals’ personal initiative to change the psychological experience of work by redesigning work activities to be more fun or more competitive. Think about a salesperson who jokes with a customer, or a bored security guard who makes up funny stories (for herself) about people entering the building. Through self-initiated play, individuals alter their experience of work to make it more enjoyable and/or more challenging.

In the current study, we build on proactivity theories (e.g. Bakker, Citation2017; Bakker & Van Woerkom, Citation2017; Parker et al., Citation2010) and play theories (e.g. Petelczyc et al., Citation2018; Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015) to examine why individuals may use PWD, for whom it may be useful, and when it may be most beneficial. We aim to make several contributions to the literature. First, this study contributes to the scarce literature on adult play—particularly to the literature on play within the work context (Celestine & Yeo, Citation2021). Although some recent studies found that PWD relates positively to work engagement (Scharp et al., Citation2019, Citation2021), it is still unclear whether PWD consequently relates to job performance over time. We provide an additional contribution by investigating the extent to which PWD relates to both in-role and extra-role performance through work engagement in a two-wave data collection study. By doing so, we also contribute to the broader literature on workplace proactivity (Parker & Bindl, Citation2017).

Second, we contribute to the literature by investigating when designing work to be more playful would be particularly useful. We do so by focusing on the moderating role of boredom. We chose to investigate workplace boredom because it is a stressful experience referring to under-stimulation (Sousa & Neves, Citation2021)—a condition in which PWD may be most relevant and effective. Theoretically, PWD is most useful when work is monotonous and provides limited stimuli (Scharp et al., Citation2021). By creating fun and competition, work becomes more interesting, meaningful, and challenging, which helps to stay focused and engaged. Insight into the boundary conditions of PWD will help organizations and consultants to design effective PWD training interventions for employees who feel under-stimulated.

Third, we contribute to the literature by examining who may benefit most by infusing work with play strategies. To this aim, we focus on the moderating role of trait conscientiousness. Costa et al. (Citation1991) have associated conscientiousness with self-discipline, achievement striving, dutifulness, and competence. Recent meta-analytic evidence (Zell & Lesick, Citation2022) as well as established data (e.g. Bakker et al., Citation2012) show that conscientiousness is important for job performance. We argue that PWD makes work tasks more intrinsically rewarding, because individuals make their own work more fun to do and more challenging. This is particularly helpful for individuals low on conscientiousness because these individuals lack the persistency and self-discipline needed to finish tasks and accomplish things at work. We argue that PWD will help this group to stay focused on work and perform well because PWD makes work tasks more intrinsically rewarding.

Theoretical background

Proactive workplace behavior

Proactive workplace behavior is an active way of behaving at work that entails initiative to change the situation or oneself (Bakker, Citation2017; Bindl & Parker, Citation2020; Parker et al., Citation2010). Three important features of proactive workplace behavior are that it is future-focused, change-focused (one acts to bring about change; for example, change in one’s work procedures), and self-starting (i.e. initiated by the self). The literature indicates that proactive workplace behaviors, such as self-initiative (Frese et al., Citation1997) and job crafting (Tims et al., Citation2012), are related to favorable individual and organizational outcomes, including improved job performance, reduced job stress, and enhanced well-being (e.g. Bakker, Citation2017; Parker et al., Citation2010). It is therefore not surprising that the literature on workplace proactivity is flourishing (Bindl & Parker, Citation2020).

Play theories

Child development and animal studies repeatedly highlight that play is important to well-being. Yet, in comparison, surprisingly little is known about adult play (Henricks, Citation2015). Van Vleet and Feeney (Citation2015) underscore three main features of adult play. First, the play activity is performed with the goal of self-amusement and entertainment. Second, it is carried out with an in-the-moment approach. Finally, it requires an intense interactive involvement, either with others, or with the activity being carried out.

Building on theoretical approaches to play (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018), we can identify several motivations for why adults may play at all, and why they choose to do so at work. Their common thread is that play is intrinsically rewarding and satisfying. First, according to humanistic and positive psychology perspectives, people play to increase the peak experience of flow. During intensive play, individuals abandon self-consciousness and feel authentic and in a state of ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975; Peters et al., Citation2014). This probably explains why the play experience is so enjoyable. Second, based on the cathartic perspective of play, individuals play to deal with stress and strain, as play may offer a cathartic relief from everyday stressors and burdens (DesCamp & Thomas, Citation1993). At work, play may provide an escape and respite from job demands (Bakker et al., Citation2020). Third, according to cognitive-behavioral approaches, play at work may be viewed as stimulus-seeking behavior, intended to increase stimulation and amusement (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018). Such behavior seems particularly important when employees find their work a boring experience. Finally, pursuant to the social-cognitive perspective (e.g. Webster & Martocchio, Citation1993), individuals reframe work as play so that it becomes a more enjoyable experience. Labeling work activities as play may enhance positive attitudes towards work and, accordingly, increase effort devoted to those activities.

The scarce literature on play at work reveals that it is associated with several benefits. Play may enhance job satisfaction and organizational involvement, and create a notion of mastery (Abramis, Citation1990). Play was also found to decrease job burnout and stress (e.g. DesCamp & Thomas, Citation1993). Glynn and Webster (Citation1992) examined trait playfulness as an individual characteristic, or a predisposition to engage in nonserious activities to increase enjoyment. They found that it was related to higher creativity, cognitive spontaneity, and laboratory task performance evaluations. Yet, until recently (Scharp et al., Citation2019), little was known about whether individuals may proactively use play at work to change their approach and thereby the experience of their work by making it more fun and challenging.

Playful work design

PWD (Bakker et al., Citation2020; Scharp et al., Citation2019) relates to how individuals proactively manage their external work environment and inner mental state by autonomously engaging in strategies during work that promote enjoyment and challenge. More specifically, PWD is a cognitive-behavioral orientation that is composed of two facets. Designing fun relates to making work more enjoyable, amusing, and interesting via the usage of humor and imagination (e.g. thinking of ways to turn work into a game). Designing competition refers to making work more challenging, competitive, and stimulating by using rules and goals (e.g. an English professor may make up a rule for herself that she will rhyme sentences in her comments for students). Note, that this competition often takes place within-persons, where one competes with oneself. By using PWD, individuals enrich their work experience by changing the execution of ongoing work activities, but without changing the essence of work itself. Thus, the subjective experience and execution of work changes but not the activities that need to be done (Bakker et al., Citation2020). PWD may be viewed as a form of proactive workplace behavior because it involves a self-initiated effort to change one’s experience of work to make it more interesting or enjoyable.

Playful work design, work engagement, and job performance

Work engagement (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006) refers to a rewarding self-fulfilling state of mind, involving heightened levels of activation and enjoyment. Specifically, work engagement is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption. Vigor relates to increased energy and persistence, even in the face of adversity. Dedication refers to a strong involvement in and enthusiasm for one’s work. Absorption refers to being fully entranced with one’s work—individuals who are engaged often forget about time and are completely immersed in their work activities (Bakker et al., Citation2011). Because work engagement enables employees to devote substantial energy into their work and stay highly focused, it was repeatedly found across diverse occupations and cultures to be a good predictor of in-role and extra-role performance (Bakker et al., Citation2012; Christian et al., Citation2011). Working in an environment where job resources are abundant, and there are fewer job demands, helps individuals stay engaged and enhance their performance. The engagement-performance link is also enhanced when individuals use proactive behaviors such as job crafting (Bakker, Citation2017).

Theories of play indicate that play is intrinsically rewarding because it is a volitional creative activity. When individuals play, they are completely absorbed by it, devoted to continuing playing, and may do so energetically (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018). Note that these attributes of play resonate with the three subcomponents of work engagement. Building on the workplace proactivity process model (Bindl & Parker, Citation2020; Parker et al., Citation2010), we argue that PWD is a form of proactive behavior, since it is a conscious proactive goal directed action with the aim of changing the experience of work. When individuals take initiative and design their work in a more playful manner, it may have stemmed from ‘can do’ motivation because individuals feel self-efficacious that they may control the situation to make work more amusing/challenging. Furthermore, ‘energized to’ motivation may have generated a positive mood which enabled individuals to be more proactive in the form of designing work to be a fun activity or a competition. Finally, ‘reason-to’ motivation generates self-initiated and change-oriented proactivity in the form of PWD to experience work as interesting and worthwhile. All three types of motivation distinguished by Parker et al. (Citation2010; see also, Bindl & Parker, Citation2020) may generate PWD which is expected to fuel continued engagement with work tasks, and, consequently, improved performance.

So far, however, only a handful of studies have examined how PWD relates to work engagement. In line with the above reasoning, in their daily diary study, Scharp et al. (Citation2019) found that on days employees used PWD more frequently, they were also more engaged with their work. In another diary study, Scharp et al. (Citation2021) investigated whether PWD can be used to deal with hindrance demands and sustain work engagement. They investigated the indirect effect of hindrance demands on work engagement, and the two dimensions of PWD were used as moderators. Scharp et al. (Citation2021) looked at daily fluctuations in PWD and showed that daily PWD strategies can reduce the extent to which daily hindrance job demands (such as conflict, emotional demands, and repetition) undermine employees’ daily engagement with work, because PWD makes work more interesting and fun, thereby creating energy and excitement, which propels work engagement. Nonetheless, the role PWD plays in enhancing performance over time through work engagement has not yet been investigated.

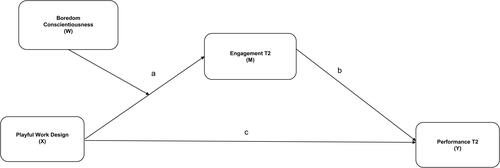

In conclusion, when employees have facilitated their own work engagement by using PWD, they can be expected to be full of vigor and enthusiasm, which enables them to help coworkers, take on additional duties, and put in extra effort (e.g. Christian et al., Citation2011). Hence, we predict that PWD will influence both in-role and extra-role performance, through work engagement (see ). Stated more formally:

Hypothesis 1: PWD will have an indirect effect on a) in-role performance and b) extra-role performance through work engagement.

The moderating role of boredom

Are there certain work circumstances in which PWD would be particularly useful? We propose that PWD is especially beneficial when employees experience workplace boredom. Workplace boredom is an understudied phenomenon that occurs when individuals experience their work as too easy, simple, and undemanding, or when there is just not enough of it (Cummings et al., Citation2016; Schaufeli & Salanova, Citation2014). Workplace boredom is a stressful (Sousa & Neves, Citation2021) experience of wishing to be engaged in captivating activities, but instead being trapped in a disengaging present (Eastwood et al., Citation2012). Proactivity theories (Bakker, Citation2017; Parker et al., Citation2010) suggest that individuals may take personal initiative to alter their work activities or work environment in order to stay engaged in their work and perform well.

Indeed, Scharp et al. (Citation2021) found that on days when individuals worked in isolation or had to deal with relatively simple or repetitive tasks, they could sustain their work engagement and performance by redesigning their work tasks to be more challenging and competitive. In another study Bakker et al. (Citation2020) found that on days that work pressure was low and that there was little work to do individuals use PWD to help them stay productive. In a similar vein, when employees design their work to be more fun, they may increase mental stimulation and focus (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018). Such a strategy would be particularly useful when employees feel under-stimulated and experience boredom. In contrast, when working in a rich environment with lots of social stimuli and high challenges, employees may experience a diminishing incremental value of playful work design for increasing work engagement and performance. Moreover, under such conditions playful work design could perhaps have unfavorable effects because the attention needed to deal with the challenges would be used for designing fun and competition. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: Boredom moderates the relationship between PWD (designing fun and designing competition) and work engagement, such that the positive relationship will be stronger for individuals experiencing more (vs. less) boredom.

Hypothesis 3: The indirect effects of PWD (designing fun and designing competition) on a) in-role performance and b) extra-role performance through work engagement will be stronger for individuals experiencing more (vs. less) boredom (moderated-mediation).

The moderating role of conscientiousness

Scharp et al. (Citation2019) found that individuals with fun-focused traits (e.g. humor, playfulness, and creative personality) tend to design their work activities to be more fun (rather than with more competition), whereas workers with competition-focused traits (e.g. achievement orientation) tend to infuse more competition in their work. Several other personality traits may play a role in the relationships between PWD, work engagement and performance. We argue that conscientiousness may be a chief candidate.

Conscientiousness is one of the five personality dimensions that comprise the Big Five model of personality (the other dimensions are extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness to experience; Costa et al., Citation1991). Conscientious individuals tend to be hardworking, reliable, self-controlled, orderly, and rule abiding (Costa et al., Citation1991; Wilmot & Ones, Citation2019). Indeed, these are the very qualities which have been found to transform work engagement into improved in-role and extra-role performance (Bakker et al., Citation2012). In fact, recent meta-analytic evidence (Zell & Lesick, Citation2022) has shown that conscientiousness is one of the most important predictors of job performance. Hence, we argue that individuals low on conscientiousness will particularly benefit from PWD by designing their work with play, because they lack the organization, efficiency, self-discipline, and persistency (Wilmot & Ones, Citation2019) that create ‘can do’, ‘reason to’ and ‘energized to’ motivations (Bindl & Parker, Citation2020), which are needed to stay engaged in order to complete work tasks and get things done. Conversely, we propose that individuals who are high on conscientiousness have sufficient motivation and energy and do not need to rely on or use PWD to increase their work engagement and subsequent work performance, because they do so anyway, by nature.

Hypothesis 4: Conscientiousness moderates the relationship between PWD and work engagement, such that the positive relationship is stronger for individuals with low (vs. high) levels of conscientiousness.

Hypothesis 5: The indirect effects of PWD on a) in-role performance and b) extra-role performance through work engagement is stronger for individuals with low (vs. high) levels of conscientiousness (moderated mediation).

Method

Participants and procedure

Our two-wave data collection involved two surveys, which were sent electronically to participants, with a month in between. Participants were employees who were also undergraduate students at the Faculty of Business Administration at a college in Israel. As part of their undergraduate studies, students had to complete a certain number of hours as research participants. Labor-market participation was a strict criterion for participation. Participants received research hours credit for participating in the study. No other compensation was offered.

Participants signed up to take part in the study electronically. An enlistment email was sent to students to explain the study’s aim and procedure, and eligibility criteria: working at least part time, in addition to being a student. Interested and eligible students were forwarded to a link with the study’s first survey. In total, 443 persons enrolled to participate in the study. Of those, 39 participants completed Time 1(T1) partially, and, therefore, they were not sent a subsequent questionnaire at Time 2 (T2). An additional 34 participants only completed the T1 survey. They did not respond to an invitation to participate at T2, nor to two subsequent reminders. Our final sample included 370 participants (response rate = 84%) who completed both the T1 and T2 questionnaires. The sample consisted of 230 women (62.8%) and 140 men (37.2%). The mean age of the participants was 26 years and four months, ranging from 18 to 58 years (SD = 6.5). All participants worked at least part time (50% or more), which is common for students. Of our participants, 38.9% worked in their current workplace less than a year; 27% between one to two years; 18.6% between 3-5 years; 11.1% between 6-12 years; and 4.4% over than12 years. Most participants (62.4%) worked in business and finance; 12.4% the government; 5.7% education; 3.8% culinary/restaurant; 1.9% science/high-tech; 1.6% entertainment/art/culture; 1.6% fashion; 1.1% health care; and 9.5% did not specify their occupational sector.

Measures

We measured playful work design, boredom, and conscientiousness at T1, and work engagement, in-role performance, and extra-role performance at T2. All scales were translated into Hebrew by three independent bilingual experts in the field. The Hebrew scales were then back-translated into English by three different independent bilingual experts. When necessary, translations were discussed and reconciled (for the conscientiousness scale we used an existing translation).

Playful work design

PWD was measured with 10 of the 12 items from the scale developed by Scharp et al. (Citation2019). The two missing items of the final scale were not yet created by the authors at the time we collected our data. The scale consists of two dimensions: Designing fun (example item: ‘I create a funny image or story in my mind when I’m faced with a stressful situation’) and designing competition (example item: ‘I set deadlines for myself, even if not required’’). The construct validity has been reported in a recent series of studies (Scharp et al., Citation2023). Participants could respond to the statements using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Cronbach’s alpha was α = .79 for the fun dimension, and α = .73 for the competition dimension.

Boredom at work was measured with the 8-item Dutch Boredom Scale (Reijseger et al., Citation2013). Here are two example items: ‘At work, time goes by very slowly’ and ‘It seems as if my working day never ends’. Participants could respond to the statements using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was α = .84.

Conscientiousness was measured with the 9-item scale from the ‘Big Five’ Inventory (John et al., Citation1991). We used the validated Hebrew translation of Etzion and Laski (Citation1998). Example items are: ‘Is a reliable worker’ and ‘Does things efficiently’. Participants indicated their agreement with statements about themselves on a scale which ranged from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Cronbach’s alpha was α = .78.

Work Engagement was assessed at T2, with the nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli et al., Citation2006). The instrument includes three subscales: Vigor (e.g. ‘At my work, I feel bursting with energy’), Dedication (e.g. ‘My job inspires me’), and Absorption (e.g. ‘I get carried away when I am working’). Items were scored on a scale ranging from (0) ‘never’ to (6) ‘always.’ Higher scores on all dimensions reflect more work engagement. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was α = .91.

In-role performance was measured at T2 with Williams and Anderson (Citation1991) scale. As recommended by Shoss et al. (Citation2013), we only used the four highest loading items. An example item is: ‘I fulfill responsibilities specified in my job description’ (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was α = .92.

Extra-role performance was measured at T2 with the Williams and Anderson (Citation1991) scale. We used only the five items from the original scale that loaded over .70. An example item is: ‘I take time to listen to co-workers’ problems and worries’ (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was α = .84.

Results

Descriptive statistics

displays the means, standard deviations, intercorrelations and reliabilities of all study variables. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the construct validity of our measurement model that included seven latent variables. Specifically, we tested a seven-factor model with the following factors: designing fun (five indicators), designing competition (five indicators), boredom (eight indicators), conscientiousness (nine indicators), work engagement (nine indicators), in-role performance (four indicators), and extra-role performance (five indicators). Individual items loaded on the corresponding constructs. The measurement model showed a reasonable fit of the 7-factor model to the data: χ2 = 1818 df = 912; χ2/df =1.99; RMSEA =.052; CFI=.89; PCLOSE=.18; TLI =.88. presents fit indices for alternative measurement models. The seven-factor model fits better to the data than an alternative nine-factor model in which work engagement was broken down to three subscales ( 46.22,

= 11, p <.001), an alternative six-factor model in which all PWD items were forced to load on one overall factor (

79.22,

= 1, p <.001), an alternative six-factor model in which all performance items were forced to load on one overall factor (

33.97,

= 3, p <.001), an alternative five-factor model in which all PWD and boredom items were forced to load on one overall factor (

211.58,

= 10, p <.001), an alternative five-factor model in which all PWD and conscientiousness items were forced to load on one overall factor (

131.75,

= 12, p <.001), and an alternative four-factor model in which all PWD, boredom and conscientiousness items were forced to load on one overall factor (

273.53,

= 15, p <.001).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations for study variables.

Table 2. Fit indices for alternative measurement models.

Convergent validity was assessed by the average variance extracted (AVE). An AVE above .5 is considered optimal, yet lower AVE may be considered when composite reliability (CR) scores are higher than 0.6 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). As can be seen from , our data meet these criteria. Discriminant validity is achieved when the square root of AVE is larger than all of the intercorrelations among the variables (Hair et al., Citation2010). As can be seen from , all variables meet these criteria.

Statistical analysis

To test our mediation hypotheses, we used the PROCESS macro model 4. In addition, to test our moderation and moderated-mediation hypotheses, we used the PROCESS macro 9, version 3.5 (Hayes, Citation2020), which estimated 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) for indirect effects based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples.

For testing all hypotheses, we conducted separate mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation analyses for designing fun and designing competition, and for in-role and extra-role performance outcomes at. Thus, in all of the analyses, the dependent variable (Y) was either in-role or extra-role performance; the independent variable (X) was either designing fun or designing competition, and the mediator (M) was work-engagement. In all analyses, when the independent variable (X) was designing fun, we controlled for designing competition, and when the independent variable (X) was designing competition, we controlled for designing fun. In all analyses we also controlled for gender and average number of working hours per day. In all mediation analyses we additionally controlled for the main effects of boredom and conscientiousness. In all moderation and moderated mediation analyses the moderators were boredom (W) and conscientiousness (Z).

Hypotheses testing

Mediation hypotheses

Hypothesis 1 stated that PWD would have an indirect relationship with in-role (Hypothesis 1a) and extra-role performance (Hypothesis 1b) through work engagement. As can be seen from , tests of indirect effects for designing fun missed the mark at 95% for in-role performance (indirect effect =.016; SE=.011; 95%CI [–0.003, .0410] and for extra-role performance (indirect effect =.024; SE =.017, 95%CI [–0.005, .062]). In contrast, also shows that designing competition showed the predicted indirect effect on in-role (indirect effect =.024; SE=.014; 95%CI [.002, .057]) and extra-role performance (indirect effect =.037; SE =.020, 95%CI [.0029, .080]) through work engagement. Employees who redesigned their work tasks to be more challenging experienced higher levels of work engagement one month later. Higher levels of work engagement, in turn, covaried with higher levels of both types of performance. Taken together, these findings support Hypotheses 1a and 1b for designing competition, but not for designing fun.

Table 3. Mediation and moderation.

Moderation hypotheses

Hypothesis 2 stated that boredom would moderate the relationship between PWD and work engagement, such that the positive relationship will be stronger for individuals experiencing more boredom. As is shown in the upper half of , the interaction effects indicate a significant interaction effect between designing fun and boredom on work engagement (ß = .116, SE = .058, p < .05, 95%CI [.010, .231]). However, as is shown in the lower half of , the interaction between designing competition and boredom on work engagement was not significant (ß = −0.015, SE = .058, NS, 95%CI [-0.129, .099]). Thus, boredom significantly moderated the link between designing fun and work engagement, but not between designing competition and work engagement. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 4 stated that conscientiousness will moderate the relationship between PWD and work engagement, such that the positive relationship will be stronger for individuals with lower levels of conscientiousness. As shown in the upper half of , the interaction between designing fun and conscientiousness on work engagement was not significant (ß = −0.121, SE = .110, NS, 95%CI [-0.337, .095]. However, as shown in the lower half of , the interaction effects indicate a significant interaction effect between designing competition and conscientiousness on work engagement (ß = −0.498, SE = .123, p <.001, 95%CI [−0.740, −0.257]). Thus, conscientiousness significantly moderated the link between designing competition (but not designing fun) and work-engagement. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

Moderated mediation hypotheses

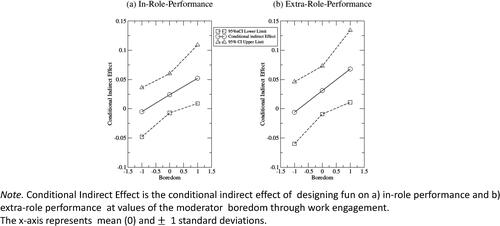

Hypothesis 3 stated that the indirect effects of PWD on in-role (Hypothesis 3a) and extra-role performance (Hypothesis 3b) through work engagement would be stronger for individuals experiencing more boredom. As shown in , the indirect relation of designing fun with in-role performance through work-engagement was stronger for individuals who experience higher (versus lower) levels of boredom with work (index of moderated mediation (IOM) = .027, SE = .016, 95%CI [.001, .062]). Specifically, the moderated mediation was significant at high levels of boredom, but not at moderate and low levels. The results of these moderated mediation analyses are depicted in panel a.

Figure 2. Indirect effects of designing fun on performance through work engagement moderated by boredom.

Table 4. Moderated mediation when both boredom and conscientiousness are included: conditional indirect effects for designing fun.

Additionally, as shown in , the indirect relation of designing fun with extra-role performance through work engagement was stronger for individuals who experience higher (versus lower) levels of boredom with work (IOM = .036, SE = .02, 95%CI [.001, .077]). Specifically, the moderated mediation was significant at high levels of boredom, but not at low and moderate levels. The results of these moderated mediation analyses are depicted in panel b. Thus, boredom moderated the link between designing fun and in-role and extra-role performance (respectively) through work engagement.

Regarding designing competition, as is indicated in , contrary to our expectations, we neither found a moderated mediation effect of boredom for the indirect relation of designing competition with in-role performance (IOM = −0.004, SE = .015, 95%CI [−0.034, .026]), nor with extra-role performance (IOM = .005, SE = .02, 95%CI [−0.047, .032]) through work engagement.

Table 5. Moderated mediation when both boredom and conscientiousness are included: conditional indirect effects for designing competition.

To sum up, boredom moderated the indirect relationship of designing fun with (a) in-role performance and (b) extra-role performance through work engagement. However, the association between designing competition and in- or extra-role performance through work engagement was not significantly moderated by boredom. Thus, Hypothesis 3a and 3b was partially supported.

Hypothesis 5 stated that the indirect effects of PWD on in-role (Hypothesis 5a) and extra-role performance (Hypothesis 5b) through work engagement would be stronger for individuals with lower (vs. higher) levels of conscientiousness. Divergent from our expectations, we did not find a moderated mediation effect of conscientiousness for the indirect relation of designing fun with in-role performance (IOM = −0.029, SE = .029, 95%CI [−0.087, .027]), nor with extra-role performance (IOM = −0.037, SE =.37, 95%CI [−0.108, .037]) through T2 work engagement. Thus, conscientiousness was not found to moderate the link between designing fun and in-role and extra-role performance (respectively) through work engagement.

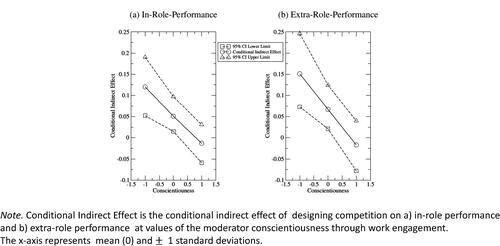

Regarding proactively designing competition, as is indicated in , we found that the indirect relation of designing competition with in-role performance through work-engagement is stronger for individuals who report lower (versus higher) levels of conscientiousness (IOM = −0.117, SE =.04, 95%CI [−0.201, −0.047]). Specifically, the moderated mediation was significant at low and at moderate levels of conscientiousness, but not at high levels. The results of these moderated mediation analyses are shown in panel a.

Figure 3. Indirect effects of designing competition on performance through work engagement moderated by conscientiousness.

As can additionally be seen from , findings revealed that the indirect relation of designing competition with extra-role performance through work engagement is stronger for individuals who report lower (versus higher) levels of conscientiousness (IOM = −0.152, SE = .05, 95%CI [-0.258, −0.066]). Specifically, the moderated mediation was significant at low and moderate levels of conscientiousness, but not at high levels. The results of these moderated mediation analyses are depicted in panel b.

In sum, conscientiousness moderated the link between designing competition (but not designing fun) and in-role and extra-role performance through work engagement. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was partly supported as well.

Discussion

The main purpose of our two-wave study was to answer three related questions: a) does PWD enhance work engagement over time, and thus augment in-role and extra-role performance? b) is PWD especially beneficial in boosting performance through enhanced work engagement when workers experience more boredom? and c) is PWD particularly helpful in augmenting in- and extra-role performance due to heightened engagement, for individuals who are lower in conscientiousness? Building on play (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018; Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015) and proactivity (Bakker & Van Woerkom, Citation2017; Bindl & Parker, Citation2020; Parker et al., Citation2010) theories, we found that the response to these questions is nuanced. Regarding our first question, we found that competition (but not fun) had a significant indirect effect on both in-role and extra-role performance through work-engagement. Regarding our second question, boredom moderated the relationship between fun (but not competition) and work engagement, and moderated the indirect effect of fun (but not competition) on both in-role and extra-role performance. With regards to our third question pertaining to conscientiousness, we found a mirror image of the results concerning boredom: conscientiousness moderated the relationship between competition (but not fun) and work engagement, and moderated the indirect effect of competition (but not fun) on both in-role and extra-role performance. We now turn to discuss theoretical and applied implications of these findings.

Theoretical contributions

Our first contribution to the literature is that we extend the nascent knowledge about PWD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate how PWD relates to performance via sustained vigor, dedication, and absorption. In line with our expectations, we found a positive mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between designing competition and in-role and extra-role performance. When designing competition, workers tend to carry over the features of play, such as heightened energy, intense involvement, and in the moment approach (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018) into their work tasks, and this helps them stay focused, dedicated, and involved with work activities, which ultimately translates into increased in- and extra-role performance. Regarding designing fun, our results just fell just shy of the 95% threshold for statistical significance. We attribute these results to insufficient statistical power, and we speculate that a larger sample size would have generated significant findings. Thus, our findings provide empirical support for the benefits of self-initiated PWD, and add to the limited knowledge about positive outcomes of play at work (Celestine & Yeo, Citation2021) and to the broader theory of play among adults, which is surprisingly scarce (Henricks, Citation2015).

Moreover, our findings also contribute to the broader proactivity literature (Bakker & Van Woerkom, Citation2017; Bindl & Parker, Citation2020). Viewing PWD through the lens of the workplace proactivity process model by Parker et al. (Citation2010; see also, Bindl & Parker, Citation2020), we argued that PWD may stem from the three types of motivation discussed there: a ‘can do’ motivation because individuals feel efficacious and in control of the situation they will generate proactive goals and utilize PWD; an ‘energized to’ motivation brings about a positive mood that will generate to proactivity of using challenge and fun in executing work tasks; and a ‘reason-to’ motivation will generate to proactivity in the form of utilizing PWD to make work seem more interesting. Thus, PWD is about individuals self-initiating proactive goal generation and striving to bring about a different future where work is experienced as more fun or challenging. Thus, our findings provide empirical support for the workplace proactivity process model.

A second contribution of our study is that our study partly answers the question of under which conditions PWD is most useful, namely to deal with boredom. We showed, that designing fun (but unexpectedly not designing competition) is particularly helpful for sustaining work engagement and enhancing performance when individuals experience high boredom with work. Indeed, our results are consistent with findings (Bakker et al., Citation2020) that showed that on days that work pressure is low and there is little work to do, individuals may use PWD to aid them in remaining productive. Our study further demonstrates that individuals who found their work interesting (low boredom) did not need to rely on PWD to help them stay focused and absorbed, as their work engagement derived from the features of work itself. However, when employees find their work tasks boring, they have a clear reason to take the initiative to make their work more fun which is particularly useful in helping them stay engaged and thus achieve higher performance.

Why is designing fun (but not designing competition) particularly important for alleviating boredom at work? We speculate that the answer to this derives from the different psychological functions of designing fun vs. designing competition. Research suggest that incorporating mental stimulation and engaging in creative imaginative thinking can be effective means of reducing boredom (Bench & Lench, Citation2019; Mann & Cadman, Citation2014). We contend that these elements are manifested in redesigning work by incorporating fun into it (but are not evident in the infusion of competition into work) and therefore in our results it was found that designing fun is particularly important in dealing with boredom to enhance engagement and performance.

A third contribution to the literature is that, we demonstrate that playfully designing competition (but unexpectedly not designing fun) is especially useful in sustaining work engagement and performance for individuals characterized by low to moderate levels of conscientiousness. Further analysis revealed that conscientiousness was the most important moderator of the link between playfully designing more competition (but not fun) and in-role or extra-role performance through work engagement. Individuals high on conscientiousness do not need to depend on PWD to increase their engagement and, ultimately, performance, because these people are more self-disciplined and hard-working by nature. Recent research reveals that conscientious individuals are more engaged in their work, even when it is less meaningful or exciting for them (e.g. Oprea et al., Citation2019). In contrast, individuals with lower levels of conscientiousness lack the restraint and perseverance to stay focused on their jobs. Why is designing competition–rather than designing fun–especially helpful for individuals low on conscientiousness in staying engaged with work and ultimately performing better? We postulate that the answer lies in the differing psychological purposes served by designing competition and designing fun. Recent studies reveal that low conscientiousness is related to excitement-seeking (Segarra et al., Citation2014) and procrastination. The latter may be explained by these individuals’ inability to ward off temptations to take part in alternative challenging activities (Dewitte & Schouwenburg, Citation2002). Thus, proactively redesigning work activities as playful competition particularly helps individuals lower on conscientiousness to find satisfaction to their excitement-seeking in work itself because work is then perceived as challenging. Designing work as fun may not elicit the same level of satisfaction for these individuals. However, designing competition helps ward off the temptations to participate in alternate enjoyable, yet distracting, activities and thereby achieve higher performance.

The most current meta-analysis on conscientiousness and performance (Wilmot & Ones, Citation2019) reveals that conscientiousness is related to goal-setting performance motivation and to goal-directed performance. Moreover, recent research indicates that conscientiousness is related to brain networks that enable prioritization of multiple goals (Rueter et al., Citation2018). Goal-setting and prioritizing are crucial for high quality performance, as has been indicated repeatedly in the goal-setting and attainment literature (e.g. Dishon-Berkovits, Citation2014; Latham & Locke, Citation2007). Accordingly, these findings may explain the link between high levels of conscientiousness and enhanced engagement and work performance. As the competition component of PWD (but not the fun component) involves self-setting of goals, something individuals low on conscientiousness appear to lack—yet is necessary for high quality performance—our findings indicate that individuals low on conscientiousness can benefit from playfully incorporating competition into their work activities.

By showing that designing competition is particularly helpful for individuals low in conscientiousness, we extend the literature on person-environment interaction, which explores how to attain a better fit between individuals’ personal characteristics and those of the work environment (Parker et al., Citation2010) and specifically the literature on the Big Five in the workplace (Young et al., Citation2018).

Practical human resource implications

Results of our study have important practical human resource (HR) applications. We recommend that organizations combine top-down and bottom-up approaches to job redesign, as this combination generates the most favorable outcomes for both organizations and employees (Bakker et al., Citation2023). From a top-down perspective, organizations may wish to create an organizational climate which fosters workplace proactivity at large and specifically facilitates PWD, and to communicate this regularly in their vision and daily practices. From a bottom-up perspective, it is recommended that HR would offer group interventions in which individuals are taught about PWD and then collaboratively share experiences and find solutions for effectively using PWD in their work (see also, Scharp et al., Citation2019). The critical incident technique (CIT; Flanagan, Citation1954) may be used to gather examples of instances when PWD was helpful. This knowledge could then be shared across HR platforms to help facilitate PWD solutions to work situations.

Yet, our findings suggest that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach might not be as optimal as tailoring interventions to specific groups. A unique group to consider are employees who experience high boredom. Indeed, there is a recent call in the literature (Oprea et al., Citation2019) to focus on ways organizations can help employees manage work-related boredom. Based on our findings, HR may offer these individuals interventions to coach them how to alter the way they experience their job to make it more fun. For example, former musicians (who can’t perform in front of audiences due to COVID-19 restrictions) who found jobs as delivery persons and experience boredom because they are underchallenged, might turn their delivery into a micro-performance to make it more enjoyable.

A recent meta-analysis (Young et al., Citation2018) indicated that several personality traits—including conscientiousness—account for almost 50% of the variance in work engagement. We believe PWD interventions to enhance work engagement are promising for individuals low on conscientiousness since our study showed conscientiousness to significantly moderate the relationship between designing competition, and performance via work engagement. As many organizations regularly use personality measures—including the Big Five—as part of their strategic HR approach for routine screening (Young et al., Citation2018), employees low on conscientiousness might be offered PWD training.

Finally, there are oftentimes occasions when, even in the most challenging and interesting jobs, individuals must perform tasks they find boring. Following our findings, it is suggested to coach all employees in designing fun, so they can use it when performing tedious or unchallenging tasks.

Potential limitations

Like all research, the current study is not free of limitations. First, we used self-report measures to capture all our concepts. Thus, like other self-report studies, concerns might arise regarding common method variance that may potentially inflate the observed associations. However, there are voices in the literature that maintain that common method variance concerns are overestimated (Crampton & Wagner, Citation1994; Spector, Citation2006), particularly when investigating private cognitions, such as PWD which would be difficult to observe by others (e.g. inventing funny stories for oneself), personality and private experiences (boredom and work engagement). Nonetheless, we recommend that future studies will use a multisource approach and try to measure records-based performance (e.g. sales records) or performance ratings of supervisors.

Second, although we used a two-waves of data collection design, using other methods such as quasi-experiments and diary studies providing longitudinal data, may provide stronger evidence for causality. For example, participants could be assigned to experimental groups that are instructed to use either daily PWD or other proactive strategies (such as self-initiative), and to a control group, and effects on engagement and performance could be measured.

Finally, our sample consisted of working students. It is conceivable that all individuals in the sample scored on the high end of conscientiousness scale, and might be more hardworking, reliable, and rule abiding in order to manage both work and academic duties. Yet, if this is indeed the case, then our use of conscientiousness as a moderator should be taken as a very conservative test because we do find the predicted relationships.

Directions for future research

Our findings suggest that PWD is an intricate construct and that under particular conditions (high boredom) or for certain individuals (low conscientiousness) different facets of PWD work best to enhance engagement and performance. Future studies might wish to explore further under which circumstances designing fun or competition would be most effective. For example, boredom has been linked to lower satisfaction and higher levels of stress and turnover intentions (Harju et al., Citation2016). Future studies may wish to examine whether in situations of high boredom designing fun (but not designing competition) might also have a positive effect on these outcomes. Another avenue is to explore the positive role of PWD for other personality traits not examined here. For example, as play provides a relief from daily stressors (DesCamp & Thomas, Citation1993), designing fun may be particularly beneficial for individuals with trait-stress (but not designing competition which may increase stress of achieving goals). Another interesting future research endeavor might examine the interaction between trait playfulness (Glynn & Webster, Citation1992) and PWD on various work dimensions (e.g. performance, creativity etc.). We encourage future research to build on our findings and explore in which occupations/sectors PWD might be most beneficial. Finally, several previous studies examined the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between job resources and proactive behavior at work (Maden, Citation2015; Maden-Eyiusta, Citation2016; Salanova & Schaufeli, Citation2008; Sonnentag, Citation2003). Other studies (Hakanen et al., Citation2018; Harju et al., Citation2016) have shown that work engagement is predictive of job crafting (proactive behavior) over time. Based on these findings, future studies might look at reciprocal effects and examine under which circumstances work engagement predicts designing fun or designing competition.

Conclusions

Organizations that wish to survive in ever-changing and competitive COVID and post-COVID business settings, need engaged employees full of vigor and dedication that attain high in-role and extra-role performance. Our study suggests that one way to achieve this is through encouraging employees to use the costless yet priceless proactive approach of designing fun and competition into their work. This is particularly helpful at times when employees experience boredom with work and for employees low on conscientiousness. Taken together, our findings provide further support to the importance of proactivity in today’s turbulent work climate.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- Abramis, D. J. (1990). Play in work: Childish hedonism or adult enthusiasm? American Behavioral Scientist, 33(3), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764290033003010

- Bakker, A. B. (2017). Strategic and proactive approaches to work engagement. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.002

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job Demands–Resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Ten Brummelhuis, L. L. (2012). Work engagement, performance, and active learning: The role of conscientiousness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.08.008

- Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., Kjellevold-Olsen, O., Espevik, R., & De Vries, J. D. (2020). Job crafting and playful work design: Links with performance on busy and quiet days. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 122, 103478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103478

- Bakker, A. B., Oerlemans, W., Demerouti, E., Slot, B. B., & Ali, D. K. (2011). Flow and performance: A study among talented Dutch soccer players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(4), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.02.003

- Bakker, A. B., Scharp, Y. S., Breevaart, K., & De Vries, J. D. (2020). Playful work design: Introduction of a new concept. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 23, e19 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.20

- Bakker, A. B., & Van Woerkom, M. (2017). Flow at work: A self-determination perspective. Occupational Health Science, 1(1-2), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-017-0003-3

- Bench, S. W., & Lench, H. C. (2019). Boredom as a seeking state: Boredom prompts the pursuit of novel (even negative) experiences. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 19(2), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000433

- Bindl, U. K., & Parker, S. K. (2020). Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change oriented action in organizations. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. American Psychological Association.

- Celestine, N. A., & Yeo, G. (2021). Having some fun with it: A theoretical review and typology of activity-based play-at-work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(2), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2444

- Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

- Costa, P. T., Jr, McCrae, R. R., & Dye, D. A. (1991). Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(9), 887–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(91)90177-D

- Crampton, S. M., & Wagner, J. A. (1994). Percept-percept inflation in microorganizational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.1.67

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play (2nd ed.). Jossey Bass.

- Cummings, M. L., Gao, F., & Thornburg, K. M. (2016). Boredom in the workplace: A new look at an old problem. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 58(2), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720815609503

- DesCamp, K. D., & Thomas, C. C. (1993). Buffering nursing stress through play at work. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 15(5), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394599301500508

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environment, 9–15. ACM.

- Dewitte, S., & Schouwenburg, H. C. (2002). Procrastination, temptations, and incentives: The struggle between the present and the future in procrastinators and the punctual. European Journal of Personality, 16(6), 469–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.461

- Dishon-Berkovits, M. (2014). A study of motivational influences on academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 17(2), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9257-7

- Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J., & Smilek, D. (2012). The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 7(5), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612456044

- Etzion, D., & Laski, S. (1998). Hebrew version by permission of the “Big Five” Inventory—Versions 5a and 54. Faculty of management, the Institute of Business.

- Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470

- Frese, M., Fay, D., Hilburger, T., Leng, K., & Tag, A. (1997). The concept of personal initiative: Operationalization, reliability and validity of two German samples. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00639.x

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Glynn, M. A., & Webster, J. (1992). The Adult Playfulness Scale: An initial assessment. Psychological Reports, 71(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.71.1.83

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Rabin, B. J., & Re, A. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Different types of employee wellbeing across time and their relationships with job crafting. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000081

- Harju, L. K., Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95-96, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.001

- Hayes, A. F. (2020). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Henricks, T. S. (2015). Play and the human condition. University of Illinois Press.

- John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. I. (1991). The “Big Five” Inventory—Versions 5a and 54. Technical report. University Institute of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2007). New developments in and directions for goalsetting research. European Psychologist, 12(4), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.4.290

- Maden, C. (2015). Linking high involvement human resource practices to employee proactivity: The role of work engagement and learning goal orientation. Personnel Review, 44(5), 720–738. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2014-0030

- Maden-Eyiusta, C. (2016). Job resources, engagement, and proactivity: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(8), 1234–1250. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-04-2015-0159

- Mainemelis, C., & Ronson, S. (2006). Ideas are born in fields of play: Towards a theory of play and creativity in organizational settings. Research in Organizational Behavior, 27, 81–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27003-5

- Mann, S., & Cadman, R. (2014). Does being bored make us more creative? Creativity Research Journal, 26(2), 165–173.https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2014.901073

- Oprea, B., Iliescu, D., Burtăverde, V., & Dumitrache, M. (2019). Personality and boredom at work: The mediating role of job crafting. Career Development International, 24(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-08-2018-0212

- Parker, S. K., & Bindl, U. K. (2017). Proactivity at work: A big picture perspective on a construct that matters. In S. K. Parker, & U. K. Bindl (Eds). Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organisations (pp. 19–38). Routledge.

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732

- Petelczyc, C. A., Capezio, A., Wang, L., Restubog, S. L. D., & Aquino, K. (2018). Play at work: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 44(1), 161–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317731519

- Peters, P., Poutsma, E., Van der Heijden, B. I., Bakker, A. B., & Bruijn, T. D. (2014). Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM-process approach to study flow. Human Resource Management, 53(2), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21588

- Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. Norton.

- Reijseger, G., Schaufeli, W. B., Peeters, M. C., Taris, T. W., Van Beek, I., & Ouweneel, E. (2013). Watching the paint dry at work: Psychometric examination of the Dutch Boredom Scale. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 26(5), 508–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2012.720676

- Roos, J., Victor, B., & Statler, M. (2004). Playing seriously with strategy. Long Range Planning, 37(6), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2004.09.005

- Rueter, A. R., Abram, S. V., MacDonald, A. W., 3rd, Rustichini, A., & DeYoung, C. G. (2018). The goal priority network as a neural substrate of Conscientiousness. Human Brain Mapping, 39(9), 3574–3585. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24195

- Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701763982

- Scharp, Y., Bakker, A., Breevaart, K., Kruup, K., & Uusberg, A. (2023). Playful work design: Conceptualization, measurement, and validity. Human Relations, 76(4), 509–550 (in press)

- Scharp, Y. S., Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., & Van der Linden, D. (2019). Daily playful work design: A trait activation perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, Article 103850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103850

- Scharp, Y. S., Breevaart, K., & Bakker, A. B. (2021). Using playful work design to deal with hindrance job demands: A quantitative diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(3), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000277

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a brief questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2014). Burnout, boredom and engagement in the workplace. In: M. C. W. Peeters, J. De Jonge, & T. W. Taris (Eds.), An introduction to contemporary work psychology (pp. 293–320). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Segarra, P., Poy, R., López, R., & Moltó, J. (2014). Characterizing Carver and White’s BIS/BAS subscales using the Five Factor Model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 61-62, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.027

- Shoss, M. K., Eisenberger, R., Restubog, S. L. D., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2013). Blaming the organization for abusive supervision: The roles of perceived organizational support and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030687

- Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518–528. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518

- Sousa, T., & Neves, P. (2021). Two tales of rumination and burnout: Examining the effects of boredom and overload. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1018–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12257

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend. ? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284955

- Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., & Bartlett, A. (2012). The fundamental role of workplace fun in applicant attraction. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 19(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051811431828

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). The development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Van Vleet, M., & Feeney, B. C. (2015). Young at heart: A perspective for advancing research on play in adulthood. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(5), 639–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615596789

- Verheijen, G. P., Burk, W. J., Stoltz, S. E. M. J., Van den Berg, Y. H. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2020). Associations between different aspects of video game play behavior and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Media Psychology, 32(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000253

- Webster, J., & Martocchio, J. J. (1993). Turning work into play: Implications for microcomputer software training. Journal of Management, 19(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639301900109

- Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700305

- Wilmot, M. P., & Ones, D. S. (2019). A century of research on conscientiousness at work. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(46), 23004–23010. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908430116

- Young, H. R., Glerum, D. R., Wang, W., & Joseph, D. L. (2018). Who are the most engaged at work? A meta-analysis of personality and employee engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1330–1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2303

- Zell, E., & Lesick, T. L. (2022). Big five personality traits and performance: A quantitative synthesis of 50+ meta-analyses. Journal of Personality, 90(4), 559–573. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12683