Abstract

This paper develops a conceptual framework of language strategies in the cross-border post-merger and acquisition (M&A) context as firms seek legitimacy for integration from their internal stakeholders. We contribute by developing a framework for advancing the debate that cross-border bidder firms employ rationalistic and nationalistic rationales to legitimise their M&A choices, including the role of language, which is an embodiment of culture to help create synergies in a post-merger integration (PMI) context. Based on our review of social identity, legitimacy, and strategic integration literature, our conceptual model outlines language strategies to achieve the twin goals of PMI and legitimising their choices. We offer a critical review of the approaches used in cross-border PMI and integrate the role of language in gaining legitimacy for the internal stakeholders, such as its impact on employees and managers. From an international human resource management perspective, we highlight the importance of language strategies for each of the four integration scenarios for the bidder and target firm employees and managers, primarily when neither the target nor the bidder firm uses English as their native language. Finally, we develop propositions to advance future research in this area. The role of international language training and other approaches is also highlighted.

Introduction

There has been an increasing interest in the role of language in international business and cross-border research (Presbitero, Citation2020; Tenzer et al., Citation2017), especially as language is perceived as power-laden and can result in adverse business and employee-level outcomes (Froese et al., Citation2016; Tenzer & Pudelko, Citation2017). In addition, there is an emergence of employee conflict and resistance (Bordia & Bordia, Citation2015) and other micro-level dynamics and interactions between employees at the bidder and target firms, which warrant attention to people management issues in an international context (Aichhorn & Puck, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Presbitero, Citation2020; Tenzer & Pudelko, Citation2017). Furthermore, other macro-level issues, such as cultural distance, socio-political and ideological stance that emerges from the multinational corporation’s (MNC) embeddedness in their external contexts has implications for international human resource management (IHRM) research (Harzing & Pudelko, Citation2014; Vaara & Peltokorpi, Citation2012). Often these power-laden and identity-based (national, organisational, or professional) language issues (Michalski & Śliwa, Citation2021) manifest as IHRM challenges in recruitment, appraisal, training, and career planning of employees, especially in cross-border M&As context, where neither the bidder nor the target firm employees speak the same native language or share a common national identity (Piekkari et al., Citation2005; Sarala et al., Citation2019). In a post-merger integration (PMI) context of MNCs bidder and target firms, the acquiring firm’s managers must address a range of operational and IHRM issues for successful integration. These include issues, such as exercising due diligence, product market choices, factor markets, and other strategic and operational integration issues. This paper argues for the exercise of strategic HR choices by IHRM managers in adopting specific language-focused strategies, such as using a common corporate language or using the English Language as the Lingua Franca in a PMI context. The paper argues that IHRM managers are best placed to exercise this HR choice as they are at the coal face of people management issues and thus, best placed for designing and implementing appropriate language strategies to support other IHRM practices in a post-integration setting. Their choice of language strategies, such as using English, can help in the effective design, implementation, and communication of IHRM practices, such as recruitment and selection of human resources, training and development, and managing their performance or implementing rewards and remuneration in a new PMI context. This is important as language-focused international business (IB)- and IHRM-research considers language proficiency, adjustment, and identity issues between host and home country nationals in MNCs as trust, knowledge sharing, and the unique role of multilingual employees can block or enable the transfer of home country practices (Bordia & Bordia, Citation2015; Harzing & Pudelko, Citation2014; Iwashita, Citation2021; Tenzer et al., Citation2021). Thus, employees must adjust to language differences and other-group orientations during recruitment in such organisations.

The impact of language proficiency in cross-border M&A and how it improves the acquiring firm’s competitiveness is not understood well (Cording et al., Citation2008). Language skills and supportive IHRM policies are vital in managing the legitimacy of the PMI activity, yet, this has not been the focus of most IHRM research. Managing MNC’s legitimacy requires ongoing efforts to manage language differences (Kedia & Reddy, Citation2016), especially in PMI) to create value from the acquisition (Haspeslagh & Jemison, Citation1991; Larsson & Finkelstein, Citation1999). A recursive link between action and discourse (Vaara & Monin, Citation2010) is embedded in the merging entities within the business environment.

Researchers have examined multi-language and communication processes at inter- and intra-organisational levels (Welch et al., Citation2005), including the role of translation services in cross-border PMI outcomes (Janssens et al., Citation2004). This stream of research views language and translation services as a power-laden strategy for achieving several favourable and adverse outcomes for different employee groups (Piekkari & Tietze, Citation2011). Further, linguistic, cultural, and workforce diversity can complicate communication as establishing shared assumptions and experiences becomes harder (Piekkari et al., Citation2005). Further, employee outcomes depend on the local context where the language strategies are implemented (Michalski & Śliwa, Citation2021). In other words, during PMI in cross-border M&A, language challenges are more pronounced due to the combined effect of employees adjusting to language diversity, language dominance, and high other-group orientation due to ownership changes. Therefore, the implications for IHRM in managing language skills training and power-laden interactions are critical.

Our critical review of cross-border PMI reveals that achieving integration is problematic for several reasons, such as due to differences in organisational and national cultures of the acquiring and acquired firms (Chatterjee et al., Citation1992; Lubatkin et al., Citation1998; Riad, Citation2005; Stahl & Voigt, Citation2008). Further, PMI efforts are directly or indirectly influenced by language differences between the bidder and target firm employees (Piekkari et al., Citation2005), often leading to differences between employees leading interactions with similar others (Makela et al., Citation2007). This creates socialisation boundaries and increases perceived power differences between the bidder and target firms (Van den Born & Peltokorpi, Citation2010). In addition, differences in linguistic cognition could lead to misunderstanding, conflict, and parallel information networks, potentially harming employees’ social interactions (Harzing & Pudelko, Citation2014). Hence, as an effective IHRM strategy, the use of a common language, such as English, as the lingua franca for conducting daily business routines can minimise adverse employee outcomes (Linn et al., Citation2018; Marschan-Piekkari et al., Citation1999a) and information processing costs (Jeanjean et al., Citation2015).

However, language standardisation efforts by the top management teams (Sanden, Citation2020; Vaara & Peltokorpi, Citation2012), can create disintegrating effects at lower (employee) levels, where these language strategies are implemented (Piekkari et al., Citation2005). Further, employees resist such strategies, if their career interests are adversely affected by their low proficiency levels in the other language (Bordia & Bordia, Citation2015; Michalski & Śliwa, Citation2021). As Welch and Welch further note, using a designated company language that is not the individual’s mother tongue creates ‘some disconnection with their national cultural base.’ Hence, while we concur that a common language is essential for effectively managing people in an IHRM context (Piekkari & Tietze, Citation2011), we also argue that an overreliance on just one language strategy requires exploration of other language strategies for greater employee integration between teams and reducing adverse employee outcomes, such as foreign language anxiety (Aichhorn & Puck, Citation2017b; Presbitero, Citation2020), thus, supporting the intended M&A performance outcomes.

Keeping in mind the focus of this paper, our discussion, and problematisation to gaining legitimacy and answering the following overarching research question from an IHRM perspective: What are key language strategies that cross-border firms should adopt for effective post-merger integration of employees and for legitimising their choices? To this end, we focus on the PMI stage of cross-border M&As where the bidder and target firm’s native languages are dissimilar. Further, these firms adopt a common language, such as English, as their Lingua Franca for conducting their daily business to achieve legitimacy. Finally, we confine the scope to only the firm’s internal stakeholders—the employees and their managers. We contribute by developing a conceptual framework that unpacks the legitimation process wherein organisational leaders use language strategically to preserve the alignment between past projections, ongoing activities (integration), legitimacy judgements, and the expectations of their internal stakeholders. Our framework offers practical and theoretically informed advice from an IHRM perspective, specifying the language strategies and developing propositions that may work in each of the four integration scenarios discussed in the M&A literature (Haspeslagh & Jemison, Citation1991).

We contribute to special issue’s calls at several levels through our conceptual framework. First, as the literature highlights that merging hitherto separate entities can create challenges (Hitt et al., Citation2001), our framework offers several language strategies for a cross-border M&A context, wherein an effective integration process is open to discursive challenges. These challenges arise as nationalistic discourse is known to delegitimise the rationalistic discourse (Maguire & Phillips, Citation2008; Vaara & Tienari, Citation2002, Citation2011; Zhu & McKenna, Citation2012) on language standardisation and the importance and benefits of proficiency in the local language (Peltokorpi & Pudelko, Citation2021). Thus, PMI implementation difficulties arise due to differences in the organisational and national cultures of the bidder and target firms (Chatterjee et al., Citation1992; Lubatkin et al., Citation1998; Riad, Citation2005; Stahl & Voigt, Citation2008) and language differences that create restricted interactions due to power differences (Makela et al., Citation2007; Van den Born & Peltokorpi, Citation2010). Our framework offers practical and theoretically informed advice from an IHRM perspective, specifying key language strategies for each of the four integration scenarios

Second, the institutional and national characteristics, such as government policies or strong unions, may have a bearing on the ability of acquirers to implement specific IHRM practices during a cross-border PMI (e.g. changes in salary and benefits, recruiting, turnover, and labor relations). Thus, imposing the acquiring firm’s language can minimise the legitimacy of the acquiring firm’s culture This is because language is inherent in the specific culture and embodies it. Thus, from an IHRM perspective, the inability to implement supportive IHRM practices and the spoken language may affect PMI success. We note the role of IHRM practices, such as language training and development and inter-linguistic socialisation in delivering appropriate language strategies that can minimise the adverse impacts on employees and deliver an effective PMI, using our conceptual framework.

Third, existing HRM practices may adversely impact the integration process, preventing potential synergies from sharing or transferring resources, knowledge, and skills (Peltokorpi & Vaara, Citation2014) or even reverse knowledge transfer (Peltokorpi, Citation2015; Peltokorpi & Yamao, Citation2017). Employees tend to resist knowledge transfer when they perceive fundamental differences in the knowledge base and the organisational image of the merging firm (Empson, Citation2001). In contrast, surface-level language diversity can create perceptions of deep-level diversity (Tenzer et al., Citation2014). In addition, language differences are associated with significantly lower oral (face-to-face and phone) communication (Harzing & Pudelko, Citation2014). Again, we posit that the adverse effects of cultural and language differences can be successfully managed through an appropriate mix of language strategies and supporting IHRM practices in a PMI context.

Based on the above, we extend Malik and Bebenroth’s (Citation2018) work on language strategies and employ Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (Citation1991) seminal work on PMI scenarios to develop strategies for cross-border bidder firms to improve and manage their legitimacy outcomes using supportive IHRM practices for managing their key internal stakeholders—employees and managers. Therefore, our distinctive contribution lies in (1) extending the expanded conceptual framework and identifying key language strategies for firms to gain legitimacy for managers and employees in a PMI context, (2) highlighting appropriate language strategy(ies) in cross-border PMI contexts, and (3) developing future research propositions.

We first briefly review different integration structures in an M&A context. Noting the linguistic and cultural challenges associated with this context, we first look at theoretical literature on legitimacy, legitimation, and judging and managing legitimacy that firms employ for managing in such cross-border M&A contexts. Second, we present a detailed review of the literature on cross-border M&A issues from an IHRM and PMI perspective, noting the role of language strategies and supportive IHRM. This review relies on three streams of literature: (1) legitimacy for cross-border M&A, (2) PMI and IHRM issues, and (3) presenting propositions to guide future empirical research. Third, we develop a conceptual model for presenting language’s role in achieving successful legitimacy outcomes through supportive IHRM practices. The following section presents the theoretical background based on which we build our conceptual framework and research propositions.

Theoretical background

In line with social identity theory’s logic that intergroup social behaviour of groups is affected by the differences due to a special status accorded to a group and its members’ identity. The role of language at work or in society has an important impact on social categorisation and leads to social identity issues (Tajfel, Citation1974, Citation1981). Language in such settings serves as a social marker as it employs a specific vocabulary or group talk that reflects the contextual norms, localised understanding, and the shared attitudes and values of members of that particular group. In a PMI context, linguistic and cultural differences between the target and bidder firm’s employees accentuate inter-group social identity issues. In a PMI context, bidder firms often seek legitimisation of their actions and, therefore, use language strategies and supportive IHRM practices for effective PMI.

Legitimacy in M&A integration choices

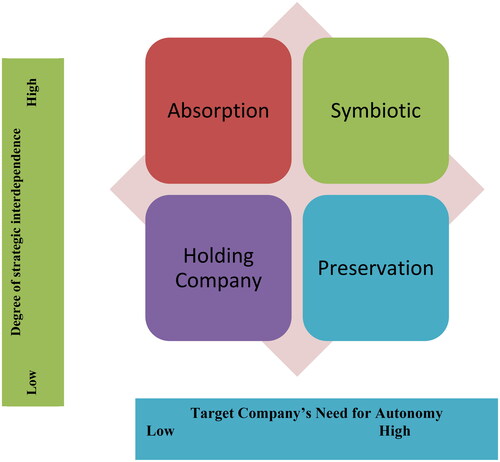

Haspeslagh and Jemison (Citation1991) seminal framework developed four commonly used structures following an M&A decision. Their work focuses on two dimensions: the extent to which firms seek strategic interdependence between the bidder and target firm and the extent to which they seek autonomy or control at the target firm. This two-by-two matrix yields four distinctive categories: absorption, preservation, symbiotic, or a holding company for the target firms. Where firms seek a high level of strategic interdependence and the need for autonomy is low for the target, such an M&A activity is described as an ‘absorptive acquisition’. However, where the extent to which strategic interdependence is low and the target firm requires high autonomy levels, such acquisition is called a ‘preservation acquisition’. In the third category of acquisitions, the need for strategic interdependence and autonomy is high, and such acquisitions can be categorised as ‘symbiotic acquisitions’. Finally, when both the extent of strategic interdependence and the need for autonomy are low, such acquisitions can be termed a ‘holding company’, noting little need for integration (see ).

However, despite the relevance of the management of M&A legitimacy during PMI, the theoretical aspects of M&A legitimacy—language strategies and IHRM practices—are not well developed. While we know how M&A strategy influences the legitimisation of the integration goals, we do not know enough about how organisational leaders engage in M&A legitimation; to preserve the alignment between the legitimacy of their integration activities, M&A structure and post-acquisition decision-making and the language strategies available to them to do so. As there is incomplete evidence of whether one action is better than the other, legitimacy as social judgement can provide an additional basis for organisational decision-making different from means-ends rationality (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002). Legitimisation includes discursive legitimisation, and organisation actions in the merging organisations are intimately linked to post-acquisition decision-making (Vaara & Monin, Citation2010). Therefore, legitimation will be simultaneously influenced by strategic goals and legitimacy judgements.

Following the rationalistic arguments for legitimacy, absorptive acquisitions merge into the acquiring firm’s structure as it affords opportunities for rationalisation and savings in the resources mix. Here the focus of IHRM practices would be more on standardisation of practices, including a common language strategy, with little need for exploring any divergence in IHRM practices or language strategies. In such cases, the bidder firms seek to gain further legitimacy by introducing their established organisational practices to the target firm.

Firms also seek legitimacy for their actions in an M&A by opting for a preservation acquisition, as several nationalistic or socio-political challenges may emerge for this category of M&A. However, the nature of strategic and operational challenges in this integration archetype is pretty low between the acquiring and target firm due to low levels of strategic interdependence and an expressed need for maintaining autonomy by the target. The IHRM practices may focus more on local responsiveness than global integration approaches evident in absorptive acquisitions.

The challenges in managing legitimacy are highest from a rationalistic legitimacy perspective in symbiotic integration. The extent to which firms co-depend on each other is most significant, and the need for autonomy is also the highest. A pragmatic approach to IHRM practices and language strategies emerges in this acquisition category. HR managers must invest in and contextualise their practices to support high levels of symbiotic relationships. Similarly, diverse language strategies may be adopted to make the integration work.

In the final category of integration, the holding company, firms seek legitimacy by presenting a rationalistic view of return on investment for its external stakeholders, and the nature of challenges typically involved in daily interactions are absent altogether. Using the compartmentalisation strategy (Kraatz & Block, Citation2008), legitimacy can be maintained by keeping the investment as a holding company. Again, the focus is not on adopting a global integration or local responsiveness in IHRM practices or language strategies. Here the entity is left to figure out the best approach as long as the returns for the shareholders are steady and maximised.

Although strategy scholars have noted that potential synergistic opportunities from the M&A are contingent on the strategic fit in the form of resource similarity or complementarity (Harrison et al., Citation1991; Ramaswamy, Citation1997), the legitimation efforts of top managers (Vaara & Monin, Citation2010) to legitimise the M&A decision depends on the projection of an ‘expected value’ (Schweizer, Citation2005). Further, the benefits obtained from an organisation’s activities can be diffused or concentrated, so the questions and challenges can be diverse or common across various stakeholders. Therefore a focus on the benefits of M&A may trigger evaluations of pragmatic legitimacy, such as to what extent the organisation’s activity (acquisition and integration) or existence (M&A investment) represents constituents’ self-interest (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990; Barron, Citation1998; Suchman, Citation1995) and less frequently the evaluations of an organisation’s moral legitimacy, wherein the focus is on whether they benefit the society as a whole. This is explored in greater detail in the following section.

M&A legitimacy and legitimation

The concept of organisational legitimacy remains one of the most frequently used platforms for theorisation in organisation studies. It is helpful to explain how cognitive and normative forces constrain, construct, and empower the acquiring firm’s actions related to the acquisition. Legitimacy is a generalised perception of a firm’s actions as ‘desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions’ (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). Other definitions depict legitimacy as a condition reflecting cultural alignment, normative support, or consonance with relevant rules or laws (Scott, Citation1995, p. 45). Thus, the acquiring firm’s legitimacy depends on the congruency between norms, values, beliefs, and expectations of society and its activities and outcomes (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990; Dowling & Pfeffer, Citation1975). These legitimacy evaluations shape how an organisation’s IHRM practices and language strategies are designed and implemented in a PMI context.

How an M&A entity established its right to exist can also be understood by analysing the legitimacy of its structural form, support, and actions at its establishment (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002). Nevertheless, understanding how it maintains this right requires how the organisation constructs a sense of legitimacy around its structure and actions over time, mainly when PMI is challenged and is being judged by employees. This attention beyond established legitimacy has resulted in the notion of legitimacy as a ‘discursive sensemaking process’, thus making language and discourse critical ingredients in the legitimation process (Vaara & Monin, Citation2010). Legitimation is the process whereby an organisation justifies to a peer or superordinate system its right to exist (Maurer, Citation1971, p. 361) has a crucial influence on ‘how the organisation is built, how it is run, and simultaneously, how it is understood and evaluated’ (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 576). Put differently, the stakeholders’ judgements directly shape the activities pursued by the organisation during the acquisition of new and leveraging of existing resources. When making their judgements, social actors evaluate based on the perceived features of the organisation through two different types of judgements, namely cognitive legitimacy and socio-political legitimacy (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994; Bitektine, Citation2011). During the analytical processing of cognitive legitimacy, the evaluations are limited to and directed at visible characteristics, such as structural properties of the organisation and other features, as the evaluators’ focus is to classify the organisation as a member of an organisational form (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977; Suchman, Citation1995).

Evaluations of cognitive legitimacy stem from generally accepted knowledge about the firm and its history (Bitektine, Citation2011) and have a quality of ‘taken-for-grantedness’ (Tost, Citation2011). In the case of M&A activity, they relate to the available knowledge about the two merging firms, i.e. their external legitimacy. Tost (Citation2011, p. 692) argues that cognitive legitimacy is a passive base for legitimacy, i.e. ‘the absence of questions about or challenges to an entity’. Thus, we understand that this type of judgement may be more applicable when the legitimacy of the M&A activity is being established. This evaluation focus contrasts with socio-political legitimacy (Bitektine, Citation2011), where the observed features of an M&A, its structural attributes, and outcomes of its ongoing integration activity—for example, the introduction of a common language policy and HRM policies are benchmarked against the projected benefits for the employees. Thus, the actor judges whether these characteristics are acceptable or unacceptable, and their reluctance can force the organisation to delay such policies (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994; Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977; Suchman, Citation1995). Furthermore, top managers are often disillusioned about English proficiency in lower echelons (Piekkari & Tietze, Citation2011), limiting such a language policy choice as a strategic tool.

Therefore, language and communication issues also affect judging and managing the legitimacy of a cross-border M&A in a PMI context. Several socio-political judgements make the management of M&A’s legitimacy, i.e. ‘it’s appropriateness’ (Suchman, Citation1995), challenging to manage. As Monin et al. (Citation2013) noted, the underlying tension between value creation and employees’ socio-political concerns is not managed effectively during the implementation process. When the judgements of illegitimacy are based on the non-fulfilment of short-term and the neglect of potential long-term gains (Schweizer, Citation2005), the organisation leaders must, along with the management of meaning (Graebner, Citation2004; Vaara & Monin, Citation2010), select and implement appropriate language strategies to legitimate integration and its intended outcomes (Vaara & Peltokorpi, Citation2012).

The key difference between cognitive and socio-political legitimacy judgments remains the nature of scrutiny. In the former, the merging organisations are assigned to a legitimate class based on known features; therefore, cognitive legitimacy helps the organisation avoid questioning its right to exist and therefore spares them from external scrutiny and distrust about their form (Bitektine, Citation2011; Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977; Suchman, Citation1995). The evaluation and scrutiny, however, continue when socio-political judgements of the M&A entity are being made when there are questions and challenges about its existence, and evaluators are interested in understanding if its activities are beneficial to them or their societies (Dowling & Pfeffer, Citation1975; Suchman, Citation1995).

Research has suggested that organisations use legitimation strategies to justify that M&A activity is purposive and deliberate (Zhu & McKenna, Citation2012). However, the discursive strategies must not seem like ‘protesting too much’ (Ashforth & Gibbs, Citation1990). Indeed they are more effective when they are subtle when used to construct a sense of legitimacy in the public domain (Vaara et al., Citation2006). The strategies used often include the use of impression management strategies in establishing legitimacy (Elsbach & Sutton, Citation1992); targeted and manipulative rhetoric to internal constituents (Brown, Citation1995; Brown & Jones, Citation2000), such as the use of legitimating narratives of epic change (Brown & Humphreys, Citation2003); adaption and tailoring of broader discourses to local needs (Creed et al., Citation2002). For example, in international M&A cases discussed by Vaara and Tienari (Citation2011), discursive strategies, such as the ‘inevitability of internationalisation’ or the ‘emphasis on synergies derived from internationalisation’ can be seen as manifestations of globalisation ante-narratives.

Nevertheless, research also shows it is not straightforward to establish the legitimacy of the M&A activity. For example, a moralisation strategy can often delegitimise a proposed acquisition action legitimised using a rationalistic strategy (Zhu & McKenna, Citation2012). Often nationalistic discourses become a solid alternative to the ‘rationalistic discourses’ in international cases of organisational change, whereas the relative strength of these discourses decreases only with the introduction of ‘global capitalism discourse’ (Vaara & Tienari, Citation2002). Therefore, legitimisation strategies are best understood using the concept of a social system that constitutes the environment in which the M&A operates and with which it needs to demonstrate consistency. For a firm operating in multiple environments, i.e. international or national, it is not feasible to be consistent with all environments. Therefore it must choose which one to be consistent with after deciding which ones are important for its survival (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002). Accordingly, English may be selected as a common language for instrumental purposes to respond to internationalisation pressures (Vulchanov, Citation2022), as is often seen in educational institutions facing international pressure (Alexiadou & Rönnberg, Citation2023; Kerklaan et al., Citation2008), and supportive IHRM practices are adopted.

Post-merger integration (PMI)—business performance and IHRM integration issues

Following the deal and depending on the desired integration structure, bidder firms need to exercise different strategic choices regarding the degree to which further strategic realignment of acquired capabilities and competencies is needed to realise value and benefits. Despite the overarching need to make an acquisition successful, the evidence in the extant literature on PMI points to bidder firms often not achieving the best outcomes from their acquisition (Tuch & O’Sullivan, Citation2007). Numerous studies point to M&A failures instead of having successful new business entities (Agrawal et al., Citation1992; Cartwright & Schoenberg, Citation2006; Datta et al., Citation1991; Jensen & Ruback, Citation1983). The literature on PMI identifies several reasons for failure: poor cultural alignment between the two firms, unreasonable targets set by the bidder of the target, and distrust and poor relationship quality between the two parties.

The literature on PMI failure groups these issues into social, cultural, and HRM integration issues and requires more significant and careful investments in soft and hard HRM practices or technical, strategic, and operational aspects during the PMI activity (see, e.g. Monin et al., Citation2013). Acknowledging these factors and focusing on a relatively less researched factor–the role of language–in gaining legitimacy in a PMI context, we investigate and review how language strategies may help an acquiring firm gain legitimacy for its internal stakeholders, employees, and managers. Further, as M&A’s success requires PMI to go smoothly (Haspeslagh & Jemison, Citation1991), we argue that appropriate language strategies may impact PMI’s success. PMI, as research suggests, should have a clear line of the path of the critical tollgates and strategies for ensuring a seamless integration process (Jemison & Sitkin, Citation1986). However, there are numerous issues that bidder firms have to deal with concerning legitimation at the PMI stage. IHRM practices have been noted as vital for effective PMI success (Aklamanu et al., Citation2016), including their impact on specific forms of PMI (Gomes et al., Citation2012).

Impact of language strategies and supportive IHRM practices on managers and employees during PMI

The extant research on the nature of language strategies in a cross-border PMI context where neither the bidder nor the target firm is a non-native English language speaker can be classified into the following groups: the use of English as a ‘Common Corporate Language (CCL)’, as the primary communication strategy between the non-English speaking bidder and acquired firms managers during negotiations; developing ‘English Language Competencies’, for improving CCL usage and finally, use of ‘Translation Services’, to overcome differences imposed by language barriers (Piekkari & Tietze, Citation2011). For effective PMI and legitimacy outcomes, the bidder firm must employ a deliberate communication strategy wherein the intensity of such communication between the target and the bidder firm must align with the integration objectives (Malik & Bebenroth, Citation2018). Furthermore, as firms are socio-technical systems, communication, and language strategies can effectively gain legitimacy for the internal stakeholders (Reiche et al., Citation2015). The following section reviews the primary language and communication strategies to help firms manage their legitimacy towards the internal stakeholders in a PMI context.

While cultural differences in cross-border M&A and cultural distance between a bidder and target have been well documented in the literature (Harzing, Citation2003; Hofstede, Citation1980/2001), the alternate role of linguistic distance is relatively understudied. Linguistic distance between employees of two merging cannot be subsumed under cultural distance (Harzing & Pudelko, Citation2014). Lack of shared language is associated with misunderstanding, conflict, and parallel information networks, which could harm social interactions, knowledge sharing, and trust formation between employees and managers (Bordia & Bordia, Citation2015; Harzing & Pudelko, Citation2014; Tenzer et al., Citation2021). Previous studies have also noted how workforce diversity in terms of linguistic and cultural differences is likely to complicate communication, as an everyday basis of shared assumptions and experiences becomes harder to establish (Piekkari et al., Citation2005). This directly impacts the IHRM practice of employees’ socialisation and establishing a psychological contract between the bidder and the target firm. In such cases, multilingual employees who can converse in both languages (of the bidder and target firm) play a critical role in embedding IHRM practices and facilitating communication between and across teams (Iwashita, Citation2021). In other words, during PMI in cross-border mergers, language challenges are more pronounced due to employees adjusting to language differences and high other-group orientation due to ownership changes.

Hence, often as an emergent strategy and as an outcome of internationalisation pressures, another common language, such as English, is selected as the Lingua Franca for conducting their daily business (Linn et al., Citation2018; Marschan-Piekkari et al., Citation1999b) and not just for external reporting to reduce information processing costs for investors (Jeanjean et al., Citation2015). IHRM policies that promulgate a common corporate language for communication in cross-border M&A contexts can help minimise adverse impacts on people management practices (Reiche et al., Citation2015). To this end, appropriate communication strategies are critical for not only effective PMI (Harzing et al., Citation2011; Janssens et al., Citation2004; Marschan-Piekkari et al., Citation1999a; Piekkari & Tietze, Citation2011) but they may help bidder firms gain legitimacy for their internal stakeholders, including employees and managers. However, employees can resist new language policies when the bidder firm introduces it to support its long-term strategic goal, as such a strategy may lack relevance to employees’ daily lives (Lønsmann, Citation2017). Another example of the impact of language standardisation efforts by the top management team on IHRM practices is that it creates a disintegrating effect at the lower levels (Piekkari et al., Citation2005). For example, this can be in the form of employee resistance, especially if they view their proficiency in the adopted language as low, such that it may adversely affect their career progression (Bordia & Bordia, Citation2015; Michalski & Śliwa, Citation2021). Further, in such cases, employees of the merging entities will most likely continue to use their mother tongue in informal communications, thus reducing knowledge sharing and trust formation (Tenzer et al., Citation2021). Finally, a lack of proficiency in the common language can affect employee interaction, social support, and network-related work and non-work adjustment (Zhang & Peltokorpi, Citation2016).

Kedia and Reddy (Citation2016) study found that PMI performance was better explained by the extent of the linguistic distance between the acquirer and the target firm, such that the greater the linguistic distance between the two firms, the less effective the PMI outcomes. Vidal-Suárez and López-Duarte (Citation2013) also examined the role language distance plays in exercising strategic choices of cross-border M&As. The researchers found that firms generally avoid M&A choices where the linguistic distance is high between the bidder and target firms due to increased transaction costs associated with such choices. The above review highlights the importance of language as a critical factor in M&A activity, especially in the PMI process. To this end, firms need to employ suitable language strategies for effective PMI and gaining legitimacy. The following section provides an overview of crucial language strategies that can be employed to suit different integration structures and consequently manage the legitimacy of their decisions.

Common language strategy studies

Marschan-Piekkari et al. (Citation1999b) argue about the role of language in improving internal communications between units (Ghoshal et al., Citation1994). Likewise, Welch et al. (Citation2005) also found how CCL can improve inter-unit coordination and group cohesiveness. Welch et al. further found that a lack of English language competency can create insecurity, exclusion, and social isolation for employees, making achieving legitimacy more difficult. The use of CCL can further reduce employees’ feeling left out or out-group, affecting their social identity and affiliation at the target firm (Kroon et al., Citation2015; Piekkari et al., Citation2005; Vaara, Citation2003). Harzing et al. (Citation2011), on the contrary, found that CCL can also serve as a potential barrier, whereas Feely and Harzing (Citation2003) highlight the value of informal tactics of repetitive communication and translation services and code-switching as alternate solutions to CCL. Cross-border M&As can also benefit from employing ‘bridge employees’ who can communicate and translate the key messages and strategic choices to the target firm from the bidder firm. Kroon et al. (Citation2015) analysed how English competency is the CCL and how it can lead to high anxiety levels for employees with low levels of English language proficiency. Tenzer and Pudelko (Citation2017) also found that differences in English language proficiency can create power dynamics among employees in multinational teams, opening another avenue for bidder firms to appropriately employ CCL and English language training for key people in developing their skills and communication strategies for gaining legitimacy for their M&A.

Translation as a communication strategy

Piekkari and Zander (Citation2005) also note the significance of language competencies and language training in conjunction with other communication strategies for managing legitimacy and change in cross-border M&A. A related strategy of using translation services is also noted in cross-border M&A contexts where the bidder and acquired firm are non-native English language speakers (Harzing et al., Citation2011). There are nevertheless several challenges in such a strategy, as translation services are not free from culturally loaded and politically charged agendas (Usunier, Citation2018), which often leads to deliberate or accidental distortions in the intended meanings of communicated messages. These exchanges may lead to poor relationship quality and breaches of trust and decision-making between the target and bidder firm. To attenuate, in some cultural and linguistic settings, words cannot always be exactly translated from a local language into English (Usunier, Citation2018).

Legitimation during the post-acquisition phase—integration process

In related acquisitions expected to provide synergistic benefits in operating efficiencies and economies, M&A gains will depend on the acquisition, resulting in closer linkages and interdependencies through post-acquisition integration processes. Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (Citation1991) four clear choices regarding PMI require a different focus from a legitimation perspective, as noted earlier. The symbiotic acquisition is one such option where owing to high interdependence and the need for organisational autonomy, the internal practices of the acquired firm are often viewed as legitimate (Clark & Geppert, Citation2011). However, research also suggests that no clear choice is possible in many situations, given that M &A is an inherently multilevel and multistage construct that any of these four approaches cannot capture given the complexity and dynamism (Javidan et al., Citation2004). Therefore, a hybrid approach is often recommended (Schweizer, Citation2005).

Nevertheless, this does not negate the fact that an unacceptable level of integration is detrimental to acquisition performance (Child et al., Citation2001) and, eventually, to the M&A’s legitimacy. However, the speed and extent of the integration process are also dependent on the acquiring firm’s employee commitment and organisational identification (Ashforth & Mael, Citation1989) and their acceptance of the proposed benefits of the acquisition (Dutton et al., Citation1994). Research suggests integration involves the management’s efforts to align the acquired firm’s identity with the acquirer’s (Clark & Geppert, Citation2011). As progressively high interdependence between the two firms is achieved and due to the planned process of identity change (Clark et al., Citation2010), employees and customers de-identify with the individual firms replacing it with re-identification for the merged or group entity (Fiol, Citation2002). During the intermittent period, the two entities may maintain a ‘transitional identity’ of the integrating operations (Clark et al., Citation2010).

Research suggests that illegitimacy of the integration process may build up during this organisational change process, an essential IHRM practice. Often this may accrue due to ineffective decisions during integration, such as the destruction of the acquired firm’s knowledge resources through employee turnover and disruption of routines (Puranam et al., Citation2002), the loss of the acquired firm’s top management, and therefore, the loss of deep understanding of the firm’s business and established relationships with employees (Cannella & Hambrick, Citation1993). Research shows that in acquisitions motivated by a desire to obtain and transfer tacit and socially complex, knowledge-based resources, retaining the acquired firm’s top managers and their cross-organisational responsibilities results in serendipitous value synergies (Graebner, Citation2004). Therefore the acquiring firm must know how to balance integration and autonomy. However, this is often difficult to implement because a higher level of integration between the firm is usually necessary for the acquiring firm to realise the expected value (Haspeslagh & Jemison, Citation1991).

During the post-acquisition integration implementation phase, the legitimacy judgements of multiple stakeholders about the legitimacy of the integration process tend to focus on the costs inherent in integration (disruption to resources and competencies, increased coordination cost, greater process complexity, and other hidden costs of implementation costs) (Zollo & Singh, Citation2004), including socio-political concerns, such as fairness or justice (Monin et al., Citation2013); or pragmatic concerns, such as the nonfulfillment of short-term benefits (Schweizer, Citation2005). Thus even though, in the long run, the benefits of cost efficiencies gained through a higher level of integration are known to be greater than the costs inherent in integration, there is ongoing resistance to any changes being introduced.

Any changes in the business environment, including external events, such as an organisation going through a crisis (Elsbach & Kramer, Citation1996), can destabilise the acquired firm’s legitimacy and can further influence the perceived appropriateness of the integration process. As a result, new interpretations of the legitimacy of the M&A may unfold (Vaara & Monin, Citation2010). Challenges to the acquired firm’s external legitimacy can reflect on the acquirer to the extent that the integrating operations are seen as the same (Kostova & Zaheer, Citation1999). For example, employees may seek to maintain their distinct identity through avoidance (Jensen, Citation2006). Therefore, these responses and concerns would disrupt the planned integration (Chreim, Citation2007). Furthermore, unfavourable judgements of the process are known to build up from the differences in organisation culture (Chatterjee et al., Citation1992; Riad, Citation2005) and in the case of cross–border mergers, national culture differences (Lubatkin et al., Citation1998) as well as resistance due to the constructions of us vs. them identities, resulting in the loss of trust (Maguire & Phillips, Citation2008). In these circumstances, the judgements of illegitimacy are usually based on the cost of integration and the neglect of potential long-term gains driving the M&A strategy (Schweizer, Citation2005).

Moreover, there is incomplete evidence of whether one judgement criterion is enough. Thus, the organisation is faced with an uncertain decision. In a less ambiguous circumstance, the organisation leaders can continue as planned with further integration activities (maintaining the legitimacy of the M&A strategy) or divest. However, a legitimation response that keeps both options open is more appropriate in an uncertain situation. For example, it is also necessary to maintain the legitimacy of the investment until the circumstances become more favourable for integration or divestment.

Legitimacy as social judgement can provide an additional basis for organisational decision-making different from means-ends rationality (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002) when decisions are taken from a purely strategic viewpoint. Furthermore, legitimisation that includes discursive legitimisation and organisation actions in the merging organisations is intimately linked to post-acquisition decision-making (Vaara & Monin, Citation2010). Therefore, legitimation in this context is simultaneously influenced by strategic intentions and legitimacy judgements.

Perceptions of socio-political illegitimacy, when added to a lack of pragmatic legitimacy about ongoing integration in the presence of strategic plans to pursue long-term benefits through the M&A activity (Schweizer, Citation2005), could disorient decision-making unless the contradictions are well managed. Research suggests decision-makers can use compartmentalisation or a strategy of loose coupling for managing contradictory demands by separating them (Orton & Weick, Citation1990; Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000), and when doing so, it would be in leaders’ interest (Westphal & Zajac, Citation2001) to utilise the strategic processes of ‘concealment’ (disguising nonconformity) and ‘buffering’ (reducing external evaluation) (Oliver, Citation1991). Any potential for fragmentation, conflict, goal ambiguity, and organisation instability (Stryker, Citation2000) can be managed using a compartmentalisation strategy: ‘because integration is avoided, disputes and conflicts are minimised, and an organisation can mobilise support from a broader range of external constituents’ (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977, p. 357). Integration can be avoided by compartmentalising the acquirer and acquired firm) via physical, spatial, or symbolic means. This approach whereby the management relates independently to different constituencies would be implementable with little resistance from stakeholders in the merging firms as due to the incomplete integration, there will remain low ‘compatibility, interdependence, and/or diffusion of the identities’ (Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000, p. 26). Compartmentalisation strategy can be discursive and or substantive. For example, an ‘organisation may do this [compartmentalisation] by sequentially attending to different institutional claims, by creating separate units and initiatives and/or [… through] merely symbolic, rather than substantive initiatives that demonstrate commitment to the values and beliefs of particular constituencies.’ (Kraatz & Block, Citation2008, p. 250). Research shows that compartmentalisation allows for inconsistency in communication (Beverland & Luxton, Citation2005), which is useful when strategy, expectations, and perceived appropriateness of the divestment or integration strategy evolve based on the unfolding situation.

The above discussion suggests that legitimation strategies influence the establishment of the M&A, its structural form (the level of integration), and actions taken by the organisation to manage its legitimacy. On the other hand, legitimacy judgements provide a reference for evaluating whether an M&A structure has access to resources and other support necessary for its survival and growth. Notably, the recursive link between legitimation and legitimacy judgements can also provide a framework for understanding the constraints and rationale for a leader’s strategic decision-making. This is particularly relevant when we recognise that apart from strategic fit and strategic intent, the legitimacy of any strategic M&A is shaped by the ongoing assessment of its outcomes by those who control the necessary resources. Eventually, we understand the organisational leader’s desire to maintain the legitimacy of their organisation and its form (M&A), influence their strategic investment decisions, and their projections of outcomes (i.e. expected value), which then shape stakeholders’ expectations and legitimacy judgements. From a managerial perspective, all the actions made by the acquiring firm should be coherent with the strategic investment (acquisition). They should be part of consistent and explicit efforts to communicate the M&A legitimacy and create favourable perceptions amongst internal and external constituents. However, such coherence need not/cannot be maintained.

While strategic investments reflect organisational leaders’ beliefs and aspirations and desire to implement an appropriate strategy, the projected value from the strategic investment is also affected directly and indirectly by the members’ activities and the competitive environment. Therefore, legitimation is influenced by any shortfall between the expected benefit from the acquisition and the organisational actions taken to realise it. While these include appropriate integration levels, adjustments (discursive and substantive) using compartmentalisation are made to the integration strategy based on legitimacy judgements in an evolving situation. Legitimation will, in this way, depict the oscillation in the legitimacy of the M & A.

Applying language strategies for enhancing legitimacy in a PMI context

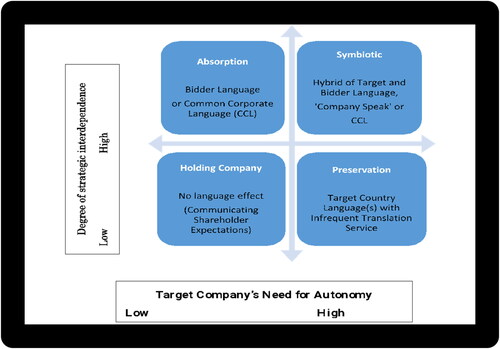

Building on Haspeslagh and Jemison’s (Citation1991) framework presented in , we now propose language strategies (see ) relevant to maintaining the legitimacy of bidder firms’ actions for each integration archetype.

Figure 2. A framework of language strategies for managing legitimacy in a PMI context adapted from in Malik and Bebenroth (Citation2018).

In the first category of absorptive integration, where the main challenge is consolidation and rationalisation, the bidder firm can gain greater legitimacy in its actions by using its language or English as the CCL. In this category, we argue that the integration would be better focused by implementing the bidder firm’s dominant or own language; however, given the potential for some language differences, the target firm may also benefit from a CCL for its daily business. Therefore, in dealing with the first PMI archetype of an absorptive integration, we believe that the bidder firm’s IHRM practices can embed the use of English language as the common corporate language, especially considering the linguistic differences between the bidder and target firms, leading to the following propositions.

Proposition 1a:

Managers of the bidder firm can enhance their legitimacy by asking the target firm’s managers to adjust to the bidder firm’s home language and/or determine English as the CCL.

Proposition 1b:

The greater the linguistic distance between the bidder and the target firm, the managers at the bidder firm can be better off adopting English as the CCL for managing their legitimacy.

For the preservation category, where the main challenge is to respect the boundaries of the bidder and target firm to make the most of each other’s capabilities and competencies, it is best to allow the target company to use their local language with some infrequent translation services. Doing so will further strengthen the legitimacy claims of the bidder firm towards the target and the bidder firm’s internal stakeholders. The mediators or translators can be internal or external to the target/bidder firms and competent in using both countries’ languages, i.e. the target and the bidder firm. In the case of a PMI archetype of preservation, letting the target firm retain autonomy makes more sense. The managers of the bidder firm can claim their regulative and cognitive legitimacy by developing a policy of inclusive integration and understanding the other party’s needs. An outward-looking HRM approach focusing on an external market orientation approach to support the needs of the target firm can go a long way in developing cordial relations, as allowing the target firm to retain its linguistic autonomy will go a long way in building inter-organisational and interpersonal trust between the employees and managers of the two entities. Therefore, this gives rise to the following research proposition.

Proposition 2:

Managers of the bidder firm are most likely to enhance their legitimacy by suggesting that managers at the target firm use their own country’s language with infrequent translation services.

In the third category—symbiotic integration—the challenge is more of reaching out than in, given the high degree of mutuality in strategic goals and integration. In such a case, adopting a hybrid approach would be an appropriate strategy, wherein both target and bidder firms’ language is allowed to be used with some translation services, in conjunction with CCL and/or the use of ‘company speak’. For example, a highly acronym-centric or codified language protocol can easily be interpreted and used by both parties. The third category of the PMI archetype, a symbiotic integration, by its very nature, requires high degrees of interaction and interdependence between the bidder and the target firms and, consequently, a relatively lower degree of autonomy for the target firm. In such instances, IHRM practices of extensive socialisation and developing a firm psychological contract between employees and managers of both entities supported by a targeted investment of having critical people as nodes and code-switchers will ensure a more productive and positive relational environment. Further, whether in-house or external, the training function can recruit and develop strong translation experts to deal with this integration category. To this end, for symbiotic integration scenarios, we propose the following:

Proposition 3:

Managers of the bidder firm would be better off by allowing target firm managers to use both the bidder and target firm’s language with some support from translation services and code-switchers.

Finally, in the case of an integration where the challenge is essentially delivering a return on investment to a group of external stakeholders, bidder firms can gain legitimacy by focusing on a communication strategy that uses the language of increasing revenues and profits and returns to the shareholders. While there will understandably be language differences, we argue for the use of simple translation services that will allow the target firm to comprehend the messaging along with some basic language skills training in financial metrics so the holding company’s expectations are communicated and well understood by the holding company’s internal stakeholders. Finally, there is minimal need for interaction and interdependence in a holding company integration structure and a slight desire to retain control of the acquired entity by the bidder firm. In such instances, the focus of the bidder firm is to ensure it secures an expected return on investment through robust fiscal governance mechanisms. Therefore, the role of employees and managerial staff is to coordinate a clear communication strategy, using either English as a CCL or through the HRM function recruiting host-country nationals, who perform the role of communicator nodes to communicate the expectations of the bidder firm. Therefore, this gives rise to our final future research proposition that needs to be tested. As such, we propose as follows:

Proposition 4:

Managers at the bidder firm are better off maintaining their legitimacy if they allow the target firm the flexibility to use their language.

Discussion, limitations, and conclusion

The above framework offers a valuable reference point for bidder firms to employ IHRM practices that help develop appropriate language strategies for managing the legitimacy of the acquiring firm and the expectations of internal and external stakeholders. For example, investment in language-specific training and socialisation practices between the bidder and target firm employees is critical to overcome some of the employee and managerial challenges associated with the dark side of language and help gain the legitimacy issues of firms. The use of the bidder firm’s language by the bidder firm’s employees who are proficient in it can be power-laden and can adversely affect social interactions with employees who are not very proficient with the common language of the bidder firm. Therefore, investment in people management practices, such as the use of teams and communication protocols for engaging two diverse workforces, requires the implementation of appropriate language and communication strategies.

Our conceptual model has proposed numerous language strategies that bidder firms may use at the target firm, especially when the internal stakeholders at neither the target nor the bidder firm are native English language speakers. Nevertheless, they employ English as their lingua franca for daily business transactions. This is particularly relevant in designing, implementing, and communicating IHRM recruitment and selection practices, training and development, socialisation, performance management, administering rewards and benefits policies, and enforcing a combination of language and communication strategies for effective people management in a PMI context. Doing so will improve PMI success and legitimise MNCs’ PMI. However, our research propositions must be tested for the four post-merger integration archetypes, especially when both the bidder and target firms are non-native English Language speakers, and how concomitant changes to strategic IHRM language policy choices may help (or not) deal with the same.

While the above set of future research propositions is vital in advancing scholarship on this topic and needs to be empirically tested, the challenge lies in recruiting bidder-target firm pairs for each of the four possible M&A scenarios. Here we offer some bidder-target country suggestions (see ), for example, Japan, Germany, Japan, France, or other European countries where English is not the native language and partake in cross-border M&A activity with other Asian countries, such as China or Japan. In addition, the field will also be enriched by an in-depth longitudinal qualitative case study design to better understand the dynamics of language strategies in these contexts.

Table 1. Non-English speaking country M&As: possible language strategies.

Once several longitudinal or comparative in-depth cross-case study designs are executed, further confirmatory ex-post-facto research designs can be implemented. The above research agenda will open up a much-needed discourse and relatively ignore the dark side influences of language on people and workplace relationships. We also believe that extant research needs to be improved in several domestic contexts, even where English is the business lingua franca. For example, interesting linguistic differences must be explored between North-South, East-West, and other regional axes in highly multilinguistic countries, such as India. There are also other complex differences in caste, religion, and local indigenous management practices, wherein dialect and vernacular differences exist. These can be examined in future research.

Given that our focus is on gaining and maintaining the legitimacy of the strategic choices for internal stakeholders, such as the employees and managers, the paper focuses on managing PMI issues. In doing so, we have argued that leveraging the bidder and targeting the firm’s human resource management infrastructure is crucial. For instance, HRM practices must invest in CCL training and development and linguistic socialisation as well as developing teams with language competencies to ensure effective PMI, M&A performance, and any adverse effects on managers and employees’ psychological well-being and effectively manage cross-cultural influences (Froese et al., Citation2016; Presbitero, Citation2020). This is critical as we review and present next to each of the significant approaches to cross-border PMI due to the role of language in gaining legitimacy through its dominant coalition of internal stakeholders, such as its employees and managers, and in making PMI effective, ensuring employee wellbeing outcomes. Finally, we argued that a bidder firm’s legitimacy objectives towards the target and the bidder firm’s internal stakeholders affect the integration goals. This will translate into using different language strategies to achieve the legitimacy and effectiveness of PMI.

Data availability statement

The data (journal articles and book extracts) that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Agrawal, A., Jaffe, J. F., & Mandelker, G. N. (1992). The post-merger performance of acquiring firms: A re-examination of an anomaly. The Journal of Finance, 47(4), 1605–1621. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04674.x

- Aichhorn, N., & Puck, J. (2017a). “I just don’t feel comfortable speaking English”: Foreign language anxiety as a catalyst for spoken-language barriers in MNCs. International Business Review, 26(4), 749–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.01.004

- Aichhorn, N., & Puck, J. (2017b). Bridging the language gap in multinational companies: Language strategies and the notion of company-speak. Journal of World Business, 52(3), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.01.002

- Aklamanu, A., Degbey, W. Y., & Tarba, S. Y. (2016). The role of HRM and social capital configuration for knowledge sharing in post-M&A integration: A framework for future empirical investigation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(22), 2790–2822. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1075575

- Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. The Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/258740

- Alexiadou, N., & Rönnberg, L. (2023). Reading the internationalisation imperative in higher education institutions: External contexts and internal positionings. Higher Education Policy, 36(2), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-021-00260-y

- Ashforth, B. E., & Gibbs, B. W. (1990). The double-edge of organisational legitimation. Organization Science, 1(2), 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.2.177

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social Identity theory and the organisation. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/258189

- Barron, D. N. (1998). Pathways to legitimacy among consumer loan providers in New York City, 1914–1934. Organization Studies, 19(2), 207–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069801900203

- Beeler, B., & Lecomte, P. (2017). Shedding light on the darker side of language: A dialogical approach to cross-cultural collaboration. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 17(1), 53–67. 1470595816686379.

- Beverland, M., & Luxton, S. (2005). Managing integrated marketing communication (IMC) through strategic decoupling: How luxury wine firms retain brand leadership while appearing to be wedded to the past. Journal of Advertising, 34(4), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639207

- Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgements of organisations: The case of legitimacy, reputation and Status. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0382

- Bordia, S., & Bordia, P. (2015). Employees’ willingness to adopt a foreign functional language in multilingual organisations: The role of linguistic identity. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.65

- Brown, A. (1995). Managing understanding: Politics, symbolism, niche marketing and the quest for legitimacy in IT implementation. Organization Studies, 16(6), 951–969. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069501600602

- Brown, A. D., & Humphreys, M. (2003). Epic and tragic tales: Making sense of change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(2), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303255557

- Brown, A. D., & Jones, M. (2000). Honourable members and dishonourable deeds: Sensemaking, impression management and legitimation in the Arms to Iraq Affair. Human Relations, 53(5), 655–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700535003

- Cannella, A. A., & Hambrick, D. C. (1993). Effects of executive departures on the performance of acquired firms. Strategic Management Journal, 14(S1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140911

- Cartwright, S., & Schoenberg, R. (2006). Thirty years of mergers and acquisitions research: Recent advances and future opportunities. British Journal of Management, 17(S1), S1–S5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00475.x

- Chatterjee, S., Lubatkin, M. H., Schweiger, D. M., & Weber, Y. (1992). Cultural differences and shareholder value in related mergers: Linking equity and human capital. Strategic Management Journal, 13(5), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130502

- Child, J., Faulkner, D., & Pitkethly, R. (2001). The management of international acquisitions. Oxford University Press.

- Chreim, S. (2007). Social and temporal influences on interpretations of organisational identity and acquisition integration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 43(4), 449–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886307307345

- Clark, E., & Geppert, M. (2011). Subsidiary integration as identity construction and institution building: A political sensemaking approach. Journal of Management Studies, 48(2), 395–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00963.x

- Clark, S. M., Gioia, D. A., Ketchen, D. J., & Thomas, J. B. (2010). Transitional identity as a facilitator of organisational identity change during a merger. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(3), 397–438. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.3.397

- Cording, M., Christmann, P., & King, D. R. (2008). Reducing causal ambiguity in acquisition integration: Intermediate goals as mediators of integration decisions and acquisition performance. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), 744–767. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2008.33665279

- Creed, W. D., Scully, M. A., & Austin, J. R. (2002). Clothes make the person? The tailoring of legitimating accounts and the social construction of identity. Organization Science, 13(5), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.5.475.7814

- Datta, D. K., Rajagopalan, N., & Rasheed, A. M. A. (1991). Diversification and performance: Critical review and future directions. Journal of Management Studies, 28(5), 529–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1991.tb00767.x

- Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organisational legitimacy: Social values and organisational behaviour. The Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388226

- Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393235

- Elsbach, K. D., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Members’ responses to organizational identity threats: Encountering and countering the Business Week rankings. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(3), 442–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393938

- Elsbach, K. D., & Sutton, R. (1992). Acquiring organisational legitimacy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories. Academy of Management Journal, 35(4), 699–738. https://doi.org/10.5465/256313

- Empson, L. (2001). Fear of exploitation and fear of contamination: Impediments to knowledge transfer in mergers between professional service firms. Human Relations, 54(7), 839–862. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701547003

- Fiol, C. M. (2002). Capitalising on paradox: The role of language in transforming organisational identities. Organization Science, 13(6), 653–666. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.6.653.502

- Froese, F. J., Kim, K., & Eng, A. (2016). Language, cultural intelligence, and inpatriate turnover intentions: Leveraging values in multinational corporations through inpatriates. Management International Review, 56(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0272-5

- Ghoshal, S., Korine, H., & Szulanski, G. (1994). Interunit communication in multinational corporations. Management Science, 40(1), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.40.1.96

- Gomes, E., Angwin, D., Peter, E., & Mellahi, K. (2012). HRM issues and outcomes in African mergers and acquisitions: A study of the Nigerian banking sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(14), 2874–2900. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.671509

- Graebner, M. E. (2004). Momentum and serendipity: How acquired leaders create value in the integration of technology firms. Strategic Management Journal, 25(89), 751–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.419

- Haleblian, J., & Finkelstein, S. (1999). The influence of organisational acquisition experience on acquisition performance: A behavioral learning perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667030

- Harrison, J. S., Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Ireland, R. D. (1991). Synergies and post-acquisition performance: Differences versus similarities in resource allocations. Journal of Management, 17(1), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700111

- Harzing, A. W. K. (2003). The role of culture in entry mode studies: From negligence to myopia? Advances in International Management, 15, 75–127.

- Harzing, A. W., & Pudelko, M. (2014). Hablas vielleicht un peu la mia language? A comprehensive overview of the role of language differences in headquarters–subsidiary communication. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(5), 696–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.809013

- Harzing, A. W., Köster, K., & Magner, U. (2011). Babel in business: The language barrier and its solutions in the HQ-subsidiary relationship. Journal of World Business, 46(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.07.005

- Haspeslagh, P. C., & Jemison, D. B. (1991). Managing acquisitions. Creating value through corporate renewal. Free Press.

- Hitt, M. A., Harrison, J. S., & Ireland, R. D. (2001). Mergers and acquisitions: Creating value for stakeholders. Oxford University Press.

- Hofstede, G. (1980/2001). Culture’s consequences, international differences in work-related values. Sage.

- Iwashita, N. (2021). Understanding the construct of speaking proficiency and its implications for classroom-based assessment. European Journal of Applied Linguistics & TEFL, 10(1).

- Janssens, M., Lambert, J., & Steyaert, C. (2004). Developing language strategies for international companies: The contribution of translation studies. Journal of World Business, 39(4), 414–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2004.08.006

- Javidan, M., Pablo, A., Singh, H., Hitt, M., & Jemison, D. (2004). Where we’ve been and where we’re going. In A. Pablo & M. Javidan (Eds.), Mergers and acquisitions: Creating integrative knowledge (pp. 245–261). Blackwell.

- Jeanjean, T., Stolowy, H., Erkens, M., & Yohn, T. L. (2015). International evidence on the impact of adopting English as an external reporting language. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(2), 180–205. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.33

- Jemison, D. B., & Sitkin, S. B. (1986). Corporate acquisitions: A process perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 11(1), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.2307/258337

- Jensen, D. H. (2006). Responsive labor: A theology of work. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.

- Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. S. (1983). The market for corporate control – The scientific evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 11(1–4), 5–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(83)90004-1

- Kedia, B. L., & Reddy, R. K. (2016). Language and cross-border acquisitions: An exploratory study. International Business Review, 25(6), 1321–1332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.04.004

- Kerklaan, V., Moreira, G., & Boersma, K. (2008). The role of language in the internationalisation of higher education: An example from Portugal. European Journal of Education, 43(2), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.00349.x

- Kostova, T., & Zaheer, A. (1999). Organisational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. The Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/259037

- Kraatz, M. S., & Block, E. S. (2008). Organisational implications of institutional pluralism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organisational institutionalism (pp. 243–275). Sage.

- Kroon, D. P., Cornelissen, J. P., & Vaara, E. (2015). Explaining employees’ reactions towards a cross-border merger: The role of English language fluency. Management International Review, 55(6), 775–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0259-2

- Larsson, R., & Finkelstein, S. (1999). Integrating strategic, organisational, and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions: A case survey of synergy realisation. Organization Science, 10(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.1.1

- Linn, A., Sanden, G. R., & Piekkari, R. (2018). Language standardisation in sociolinguistics and international business: Theory and practice across the table. In English in Business and Commerce. (pp. 19–45). de Gruyter Mouton.

- Lønsmann, D. (2017). Embrace it or resist it? Employees’ reception of corporate language policies. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 17(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817694658

- Lubatkin, M., Calori, R., Very, P., & Veiga, J. F. (1998). Managing mergers across borders: A two-nation exploration of a nationally bound administrative heritage. Organization Science, 9(6), 670–684. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.6.670

- Maguire, S., & Phillips, N. (2008). ‘Citibankers’ at Citigroup: A study of the loss of institutional trust after a merger. Journal of Management Studies, 45(2), 372–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00760.x

- Makela, K., Kalla, H. K., & Piekkari, R. (2007). Interpersonal similarity as a driver of knowledge sharing within multinational corporations. International Business Review, 16(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2006.11.002

- Malik, A., & Bebenroth, R. (2018). Mind your language!: Role of language in strategic partnerships and post-merger integration. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 11(2), 202–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGOSS-05-2017-0011

- Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, D., & Welch, L. (1999a). Adopting a common corporate language: IHRM implications. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 10(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851999340387

- Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, D., & Welch, L. (1999b). In the shadow: The impact of language on structure, power and communication in the multinational. International Business Review, 8(4), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-5931(99)00015-3

- Maurer, J. G. (1971). Readings in Organisation Theory: Open-System Approaches. In John G. Maurer (Ed.), Random House. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00760.x

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalised organisations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Michalski, M. P., & Śliwa, M. (2021). ‘If you use the right Arabic…’: Responses to special language standardization within the BBC Arabic Service’s linguascape. Journal of World Business, 56(5), 101198.

- Monin, P., Noorderhaven, N., Vaara, E., & Kroon, D. (2013). Giving sense to and making sense of justice in post-merger integration. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 256–284. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0727

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. The Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/258610

- Orton, J. D., & Weick, K. E. (1990). Loosely coupled systems: A reconceptualisation. Academy of Management Review, 15(2), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.2307/258154