Abstract

This study investigates the critical role of employees in shaping frontline managers’ (FLMs) HR implementation. It goes beyond previous research, which recurrently attributes FLMs’ implementation behavior to the facilitating conditions and FLMs’ personal capabilities, overlooking or downplaying the potential impact of employees during the implementation process. In doing so, we characterize the construct of intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices as a key force influencing FLMs’ HR enactment. Hence, we hypothesize how intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices is linked to FLMs’ implementation behavior through FLMs’ performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence. In this narrative, we position team-level HPWS as a direct outcome of FLMs’ implementation behavior. Therefore, we establish that team-level HPWS mediates the relationship between FLMs’ implementation behavior and team performance, underscoring the importance of employees in the HRM variability debate. Conducting a time-lagged study and analyzing data collected from 23 South Korean firms, we found support for our theoretical claims. Our findings recognize employees as significant contributors to the implementation process and challenge the conventional wisdom in which employees are viewed as passive recipients of HR practices. We discuss theoretical and managerial implications and offer directions for future endeavors.

Introduction

Evidence is mounting that the effectiveness of HRM systems, in large part, is a function of the quality of FLMs’ HR implementation behavior (Gilbert et al., Citation2015; Op de Beeck et al., Citation2018; Pak & Kim, Citation2018). Accordingly, scholarly interests surged to entitle FLMs as HR agents (Purcell & Hutchinson, Citation2007), whose primary role consists in enacting adopted HR practices on par with the standards set forth by the HR department (Kehoe & Han, Citation2020). In this light, many efforts have been made to understand what FLMs require to operate as effective HR implementers or agents for the organization (e.g. Pak, Citation2022). The central theme in this line of inquiry is that scholars utilized ability, motivation, and opportunity-enhancing framework (AMO), delineating how HR departments should empower FLMs to fulfill their HR responsibilities (Guest & Bos-Nehles, Citation2013; Kurdi-Nakra et al., Citation2022; Trullen et al., Citation2016). In other words, FLMs’ HR implementation has often been analyzed through the lens of organization-level enablers (Bos-Nehles & Meijerink, Citation2018; Perry & Kulik, Citation2008; Ryu & Kim, Citation2013). At this juncture, we argue that explicating FLMs’ HR involvement as primarily firm-driven risks omitting other within-organizational dynamics that influence FLMs’ HR involvement.

In line with this concern, Renwick (Citation2003) highlighted that the co-consideration of the HR triad composed of HR departments, FLMs, and employees is crucial to the effectiveness of HRM. Later, several scholars also emphasized that having a well-designed HRM system is not sufficient per se and is susceptible to failure if employees’ collective acceptance of HR practices is not taken into account (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Den Hartog et al., Citation2013). This debate is paralleled by recent calls by Kehoe & Han (Citation2020) and Gjerde & Alvesson (Citation2020), suggesting that scholars should study the attitudes and behaviors of employees or subordinates if FLMs are anchors of inquiry when investigating the implementation process. However, our in-depth literature review indicates that, more often than not, scholars picked a narrow lens, portraying employees as passive recipients of HR practices. As a result, subordinates’ potential to influence FLMs’ involvement in HR duties has been overlooked or, at least, largely downplayed in the HR devolution literature (Kurdi-Nakra et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, past research offers mixed findings on the impact of devolving HR responsibilities to the line. For example, some scholars argue that delegating HR tasks to the FLMs comes with role overload and stress that might impair FLMs’ unit performance (e.g. Evans, Citation2017; Gilbert et al., Citation2011). Also, it is suggested that FLMs have often been recognized as technical managers, with unit performance as their foremost priority, and therefore, HR duties fall out of their attention (Brandl et al., Citation2009; Ryu & Kim, Citation2013). In their view, technical and HR responsibilities are two neatly separated responsibilities such that performing one might potentially cost the other. On the contrary, Vossaert et al. (Citation2022) and Gjerde & Alvesson (Citation2020) assert that FLMs’ operational and people management responsibilities are intertwined and thus call scholars to explore FLMs’ concurrent attitudes toward HR and operational responsibilities. However, empirical examinations, if any so far, rarely offer intricate narratives of how FLMs juxtapose HR and operational duties and conceive HR tasks in association with team objectives.

In addition, although there has been noticeable progress in the within-organizational variability in so-called high-performance work systems (HPWS) (c.f., Wright & Nishii, Citation2013), past research in this space has often used HPWS as an independent variable when examining the HRM-performance link. This implies that the fundamental question of why such variability between espoused and implemented HPWS exists is not often factored into the empirical models of studies (Han et al., Citation2018; Ma et al., Citation2021; Pak & Kim, Citation2018). Recent studies report that though HPWS is uniformly espoused in the organization, there is a gap between managerial and employees’ reports of HPWS (Vermeeren, Citation2014). We argue that firms depend heavily on teams and working units to implement intended HR practices, counting on team managers as the agents of the organization (Pak & Kim, Citation2018). Notwithstanding the central role of FLMs in HR enactment is firmly corroborated, rarely has it been the case that these two separate research streams, namely variability in HRM and FLMs’ implementation behavior, are integrated into empirical inquiry (c.f., Pak, Citation2022; Pak & Kim, Citation2018).

In response to those concerns, the current study characterizes intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices to examine how subordinates can affect FLMs’ implementation behavior. In doing so, we draw on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1985). We define intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices as the degree to which team members concur on how espoused HR practices are implemented in the workgroup. More precisely, it is a collective psychological agreement specifying what HR practices they value to be subject to and how those practices should be manifested in teams. From the lens of TPB, one’s behavior is rooted in cognitive evaluations (i.e. attitudes) and social norms (Ajzen, Citation1991). In this light, FLMs are positioned in an organizational hierarchy where, by virtue of their proximity, interactions with their team members under their supervision frequently occur (Gilbert et al., Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2020). To a certain extent, FLMs’ are often subject to group norms and subordinate demands, rendering FLMs to accommodate subordinates’ expectations (Ajzen, Citation1991; Kehoe & Han, Citation2020; Liao et al., Citation2016). If so, it is a reasonable conjecture that FLMs’ implementation behavior is likely to be influenced by team-members’ consensus over espoused HR practices that, in aggregate, manifest into realized HRM at the workgroup level (Fan et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2019; Pak & Kim, Citation2018).

To be more specific, we investigate how FLMs’ performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence mediate the link between intra-team acceptance of espoused HR and FLMs’ implementation behavior. Previous research widely echoed that FLMs are under pressure to boost team performance (Evans, Citation2017; Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Whittaker & Marchington, Citation2003). Therefore, performance expectancy serves as a yardstick for FLMs to gauge whether HR enactment positively impacts team performance. Hence, with a favorable attitude toward personnel responsibilities (c.f., motivational significance), FLMs are less likely to translate HR-related tasks into it-is-not-my-job (c.f., Hall & Torrington, Citation1998; Kurdi-Nakra et al., Citation2022) but willingly embrace them as core duties to ensure the maximum effectiveness of their team. Plus, TPB suggests that perceived ease and volition control over carrying out tasks help individuals develop more positive attitudes toward them (i.e. effort expectancy; Ajzen, Citation1991). In this respect, FLMs may become more willing to exert effort into HR responsibilities rather than shirk them if FLMs believe that their subordinates endorse certain HR-related tasks. As for social influence, TPB guides us that individuals act primarily based on the patterns of social interactions in which they are embedded (Ajzen, Citation1991; Perrigino et al., Citation2021). Since FLMs’ are the foremost resort for subordinates to communicate their desirable HRM, subordinates often create normative pressure on their FLMs until their expectations are met (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Fan et al., Citation2021; Kou et al., Citation2022). Hereupon, we predict that as the result of the social influence brought forth by their group members, FLMs are likely to enact espoused HR practices following what they deem socially desirable. Moreover, addressing scholars’ acknowledgement that variability often exists at the work-unit level (Pak, Citation2022; Vermeeren, Citation2014; Wright & Nishii, Citation2013), we relate FLMs’ implementation of espoused HR practices to team performance through team-level HPWS. Past research shows that FLMs have their own modus operandi and deliver HR practices differently, even when the same set of HR practices are in place within the organization (Pak & Kim, Citation2018). On this basis, we propose that team-level HPWS is the product of FLMs’ implementation behavior. Thus, delineating the mediating effect of team-level HPWS between FLMs’ implementation of espoused HR practices and team performance sharpens our understanding of how and why adopted HR practices often take different forms when they reach the shop floor of the organization.

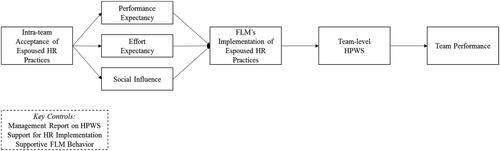

As such, the current study makes important contributions on several fronts. Our research answers the recent call for delving into subordinates’ pivotal role in shaping the effectiveness of HR implementation (Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Kehoe & Han, Citation2020). Herein, our development of intra-team acceptance of espoused HR highlights the role of subordinates as a powerful force that impacts FLMs’ involvement in their HR duties. Specifically, our study discloses that not only FLMs do not distinguish between their HR and operational objectives, but they also view HR responsibilities as a vehicle to improve team performance. Moreover, we share concerns over the dominant static approach that often assumes HR policies and practices are conveyed intact from the top of an organization down to the bottom. Our examination of the mediating effect of team-level HPWS between FLMs’ implementation of espoused HR and team performance partly unpacks the elusive black box. We illustrate that HPWS is the product of FLMs’ implementation behavior. This is significant because the agreement is rising among scholars that characterizing HPWS as a generic organization-level phenomenon oversimplifies the within-organizational dynamics involved in HR implementation processes that eventually maneuver the HRM-performance link (e.g. Fan et al., Citation2021; Han et al., Citation2018; Pak, Citation2022). illustrates our proposed research model.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Variability within organizations

A significant portion of the research on the HRM-performance link, has traditionally focused on somewhat two distal variables, intended HRM and organizational performance, both situated at the organizational level, assuming that HR practices are implemented across the organization in their intended way (Vermeeren, Citation2014). However, observations revealed that the gap between espoused and actual HR practices could impede the achievement of the organization’s objectives (Pak et al., Citation2016; Wright & Nishii, Citation2013). On this ground, HRM scholars have paid particular attention to understanding why the same set of HR practices leads to divergent outcomes depending on how such practices are framed and received by employees (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Chang & Pak, Citation2024; Wang et al., Citation2020). Recognition of such variability has led to a proposition that the positive effects of HRM do not necessarily result from having good HR practices in place per se but from the effective management of implementation processes (Bai et al., Citation2023; Chang et al., Citation2020; Pak, Citation2022; Vermeeren, Citation2014). To address concerns regarding variability in HRM, recent studies have attempted to measure actual or perceived HPWS and examine how they are associated with level-specific processes and outcomes (e.g. Lee et al., Citation2019). Although this line of research has deepened our knowledge by articulating more proximate interconnections between HPWS and performance, some criticism still resonates, keeping the discourse open for further scrutiny (Pak, Citation2022; Pak & Kim, Citation2018). Aiming at ensuring effective HR implementation, past research often focused on examining how utilization of HPWS (i.e. the AMO framework), as an independent variable, prepares FLMs and supports them for their HR role (e.g. Trullen et al., Citation2016). Existing research has limited itself by factoring in HPWS as independent variables. Additionally, some scholars shed light on employees’ perceptions and experiences of HR practices to capture the variability in HRM. This research stream unveils the discrepancy in HR implementation and employees’ varied attributions, represents employees as passive recipients of the HR system, and skips their critical role in influencing their immediate supervisors’ implementation behavior. In doing so, the question of why variance in realized or perceived HRM is observed within organizations remains unanswered. Studies on HRM strength (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004), employee attributions (Nishii et al., Citation2008), and the process model of SHRM (Guest & Bos-Nehles, Citation2013; Wright & Nishii, Citation2013) have provided clues as to why this variance could develop. However, little effort has been made to address this phenomenon within the purview of FLMs’ implementation behavior and HPWS research (c.f., Pak & Kim, Citation2018; Pak, Citation2022).

Intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices and FLMs’ implementation behavior

A high level of agreement in a team is indicative of a strong team climate (e.g. González-Romá & Hernández, Citation2014) in which team members, including their supervisors, shape their attitudes and behave accordingly (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Van Beurden et al., Citation2021). This degree of consensus that team members amass over time determines the actions that will lead to desired outcomes for team members (González-Romá et al., Citation2009). Recent research demonstrates that even when policies and practices are designed out of a team, at upper levels in the organization, teams often perform partly otherwise (Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Vossaert et al., Citation2022). At the heart of this process are FLMs, as the first point of contact for subordinates who are experiencing pressure to fulfill subordinates’ expectations that might differ from standard practices (Liao et al., Citation2016).

Drawing on this insight, the current study develops the construct of team members’ acceptance of espoused HR practices, aiming at demonstrating how subordinates release forces that predispose FLMs to enact HR in accordance with team expectations. To do so, we leverage insights from TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991) to explain how subordinates actively influence their immediate managers’ implementation of espoused HR practices. The central tenet of TPB posits that individuals’ behavior stems from the network they are embedded in, where individuals attempt to comply with important others (Ajzen, Citation2002). In this light, intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices, which concerns the degree to which team members concur on how espoused HR practices are implemented in the workgroup, is a collective and conductive behavior, compelling FLMs to serve their team members accordingly. Remarkably, intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices can be treated as a meaningful and stronger construct than individuals’ perceptions of HR practices because it emphasizes the shared purposes and the interconnections among all individual members, unleashing a more powerful influence on FLMs’ implementation behavior, which might not otherwise be realizable by individual observation alone. To articulate, individuals and en masse as a group, in close proximity, frequently interact to reach a common understanding and shape a shared perspective over the phenomena in their work environment. From this standpoint, in any social setting, employees’ evaluation of the degree of consensus in the team not only is conceivable but also emerges naturally as part of a continuous process through which they attempt to converge their views (Weick & Weick, Citation1995). Then, they resonate their agreement and expectations in work groups until they ensure their supervisors act based on their expectations and their espoused HR practices come to life (Fan et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2020).

FLMs’ performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence as mediators

In prior studies, FLMs were found to be reluctant, or at best hesitant, to engage in HRM, given an uncertain interlink between people management responsibilities and unit performance (Evans, Citation2017; Ryu & Kim, Citation2013). Relatedly, some studies suggested that FLMs believe undertaking HR duties may cause them to lose sight of their technical responsibilities and therefore, for FLMs, meeting operational targets might take priority over HR tasks (Bos-Nehles & Van Riemsdijk, Citation2014; Gilbert et al., Citation2011; Woodrow & Guest, Citation2014). Uneven answers to this dilemma left FLMs somewhat unwilling and undecided about how to shape their attitudes toward their HR responsibilities (Guest & King, Citation2004; Kurdi-Nakra et al., Citation2022). In this respect, more recently, Gjerde & Alvesson (Citation2020) and Vossaert et al. (Citation2022) argued that when HR practices are designed top-down, FLMs go through various discretionary adjustments upon their anticipation, delivering HR practices such that unit performance is improved accordingly. To extend this dialogue, we adopt the TPB perspective (Ajzen, Citation1991) to establish how FLMs’ attitudes and perceived association between their HR duties and team performance impact their subsequent implementation decision.

According to TPB, positive attitudes are the immediate precursor to a person’s decision to display a certain behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Given that FLMs have often been identified as operational managers and, hence, HR responsibilities convey significant meaning to them if they believe that HR involvement enhances team productivity and ensures team performance. Such a positive attitude is likely to orient them toward effective HR implementation (Evans, Citation2017; Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020). To put it differently, intra-team agreement over espoused HR practices is a supervisor-conductive situation through which team members signal that if FLMs deliver HR as collectively agreed, there would be more chance for the team to achieve its goals. Within Ajzen’s theory, positive expectations toward a behavior gauge a person’s evaluation of that behavior (c.f., Ajzen, Citation1991). In this vein, if FLMs believe that involvement in people management responsibilities could enhance team performance, FLMs are more likely to display favorable implementation behavior, presumably facilitating their team performance.

TPB also suggests that individuals assess their control and perceived ease of handling a task before regulating their efforts commensurately (Ajzen, Citation1991; Venkatesh et al., Citation2003). In other words, an individual’s estimation of volitional control and task difficulty predicts the amount of effort they will put forth (i.e. effort expectancy). The insight we draw from this is that when a within-team agreement is formed and communicated, FLMs are not only clear about their HR role, but they receive endorsement from subordinates, motivating them to devote more effort to HR implementation (Gist, Citation1987; Kou et al., Citation2022). This means that when subordinates communicate their agreed HR terms with their supervisors, they impart some sense of credit and power to their managers, which triggers FLMs’ self-efficacy in handling HR duties and results in more dedication to HR responsibilities.

Our study also proposes that FLMs tend to behave in ways that are consistent with what their subordinates deem appropriate and worthwhile. From the TPB lens, behavior results from social pressure, under which one strives to comply with the expectations of salient others (Ajzen, Citation1991; Citation2002). In this respect, we propose that when the within-team agreement is established, it will not remain dormant. However, team members communicate their desirable expectations to regulate their supervisor’s implementation behavior and normalize the locally agreed HR terms (i.e. social influence). Prior studies confirmed that employee perception of HR practices is decoupled from managerial reports of HR practices (Liao et al., Citation2009), and employees tend to interpret management’s intent behind organizational initiatives (Nishii et al., Citation2008). Therefore, developing consensus within teams on the ways of HR implementation may be critical in establishing a local normative climate. In teams wherein behavioral expectations are explicitly communicated, norms can arise formally, compelling FLMs to follow the subjective norms empowered by employees (Pak, Citation2022). In other words, significant others’ (i.e. subordinates’) unwavering emphasis on the implementation of espoused HR practices releases a powerful force, pressing FLMs to enact HR practices by team expectations and the local climate in the team (Kou et al., Citation2022). Taking the discussion so far into account, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Performance expectancy mediates the relationship between intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices and FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices.

Hypothesis 2: Effort expectancy mediates the relationship between intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices and FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices.

Hypothesis 3: Social influence mediates the relationship between intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices and FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices.

FLM’s implementation, team-level HPWS, and team performance

Although FLMs are often named HR agents for the organization, they have enough discretion on the degree to which the adopted HR practices are enacted in their work groups. At this juncture, the managerial challenge arises from variance in the quality of HR enactment resulting from each FLM’s different competence, skills and levels of motivation (Bos-Nehles & Meijerink, Citation2018; Pak & Chang, Citation2023). In this line of reasoning, it could also be viewed that FLM’s enactment behavior regarding adopted HR practices subsequently leads to the emergence of actual HR practices in that particular work group (Pak & Kim, Citation2018). It is because they attempt to adjust the contents and processes to suit team members’ local needs (Kehoe & Han, Citation2020; Kurdi-Nakra et al., Citation2022). On this matter, Lee et al. (Citation2019) recently demonstrated that within-organization variability in HRM can be meaningfully captured at the workgroup level. Thus, unlike the majority of past research which use HPWS as an organizational independent variable, this paper proposes team-level HPWS, which emerges in the context of the team as the result of FLMs’ implementation behavior. In other words, team-level HPWS can be introduced as the shared understanding of shared HR experiences among team members (Aryee et al., Citation2012; Ma et al., Citation2021).

Recent studies confirmed that performance-oriented HRM systems measured at the group level are indeed associated with level-specific processes, which in turn are conducive to commensurate outcomes (Lee et al., Citation2019). Past research has elucidated that utilization of AMO, meaning that enhancing role-relevant skills and competencies, motivation, and opportunities to contribute can enhance individual performance (Gardner et al., Citation2011; Guest & Bos-Nehles, Citation2013; Trullen et al., Citation2016). These improved AMO dimensions among individual employees could, in aggregate, contribute to achieving team outcomes (Pak, Citation2022). Taken together, we argue that realized HPWS can largely be explained by the level of team manager’s enactment over the implementation phase, and the higher utilization of HPWS at the team level result in improved team performance. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between FLM’s implementation behavior of espoused HR practices and team performance will be mediated by team-level HPWS.

Research methods

Sample and data

We tested our proposed relationships with data collected from 23 manufacturers of consumer and industrial goods operating in South Korea. Companies that participated in this study had a team-based structure, and team members, including FLMs, worked closely with each other. Direct supervisors were active participants in their respective teams and were expected to carry out various HR and technical responsibilities. Before data collection, the authors visited a chief human resource officer (CHRO) or a senior manager of each target organization to discuss the purpose of this study. During visits, we also conducted a series of interviews with HR professionals to ensure that the company’s HR practices were designed in accordance with the design principles of HPWS. We also reviewed internal archives describing HR policies and HR-related programs. To improve the rigorousness of the current study, the authors asked CHRO or a senior manager of each organization to complete a survey concerning espoused HR practices, which were controlled for when conducting main analyses.

To alleviate common method bias (CMB), we collected multi-source data in two waves with a six-week interval. A total of 729 questionnaires have been distributed to 128 teams. At time 1 (T1), intra-team acceptance, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and control variables were surveyed. In this phase, team members were invited to assess the intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices, and FLMs’ were asked to rate performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence. At time 2 (T2), team members rated FLMs’ implementation behavior and team-level HPWS, and FLMs reported on team performance. Overall, 652 surveys returned (i.e. 89.4% of initial response rate). After cleaning and matching data, the final sample of this research consisted of 603 individuals (i.e. 481 work group members and 122 FLMs), and the response rate was 82.7%.

As for the composition of teams, 67.1% were male, with an average age of 36.3. An average work experience was 9.1 years, and 75.2% of team members held either a 4-year college or a postgraduate degree. As for FLMs, 80.4% were male, with an average age of 44.7. An average work experience was 16.9 years. As for the job group composition of the final sample, management/administration was 35.3%, manufacturing 27.5%, sales and service 26.8%, research & development (R&D) 10.4%, and the average team size was 6.3.

Measures

Unless otherwise stated, responses were measured on a five-Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Wordings of the original items were adjusted to fit the research context.

Team-level HPWS

We initially drew on an HPWS construct suggested by Takeuchi et al. (Citation2007). To strengthen the opportunity-enhancing side of HPWS, we added two more items from Sun et al. (Citation2007) because the original measure has only one item for the dimension. To capture a team-level phenomenon more properly, we placed the following question up front, ‘Please compare your actual HR experiences within your team with intended, or at-the-policy-level, HR practices (e.g. training, performance appraisal, participatory programs); how strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements?’. With the 23-item measure, we conducted a principal axis factoring extraction, imposing a single-factor solution (Takeuchi et al., Citation2007). Factor loadings ranged from 0.65 to .84. The total eigenvalue was 13.1, and the cumulative explained variance was 60.1%. The results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed that χ2 = 446.1, degree of freedom (df) = 212.9, χ2/df = 2.09, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.94, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.93, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.91, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .07. Therefore, it was established that the measure showed acceptable model fit. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices

We used a five-item measure developed by Pak & Kim (Citation2018). Sample items included, ‘Many times I have witnessed that my team manager enacts HR practices, strictly following corporate HR processes’, and ‘Many times I have witnessed that my team manager acts as an enthusiastic advocate of the HR policies of our company’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices

The authors developed the construct predicated upon a two-item measure of consensus (Powell & Dent-Micallef, Citation1997). Besides, the authors added three more items drawn from a series of interviews with FLMs and individual employees. Sample items included, ‘There is consensus on the enactment of espoused HR practices in our team’, ‘In our team, strict enactment of espoused HR practices matters’, and ‘We have little conflict between a team manager and members of the team over the implementation of espoused HR practices’. We also conducted a principal component factor analysis using varimax rotation, and the items were loaded on a single factor. Factor loadings ranged from 0.74 to .88. The total eigenvalue was 4.1, and the cumulative explained variance was 71.5%. The results of CFA established a good model fit (χ2 = 12.5, df = 5.4, χ2/df = 2.31, IFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.99, and RMSEA = .07. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Performance expectancy

We used a four-item measure suggested by Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003). Sample items included, ‘I believe that implementing espoused HR practices enables our team to accomplish tasks more effectively’, and ‘I believe that implementing espoused HR practices increases our team’s productivity’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Effort expectancy

The authors used a four-item measure suggested by Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003). Sample items included, ‘I find espoused HR practices easy to implement in our team’, and ‘To me, the rules and procedures of enacting HR practices are clear and understandable’, and ‘operating the HRM system within our team is easy for me’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Social influence

We drew on a four-item measure developed by Venkatesh et al. (Citation2003). Sample items included, ‘People who are important to me think that I should implement espoused HR practices’, ‘I believe that enacting espoused HR practices in a strict manner is considered socially desirable’, and ‘People who influence my behavior think that I should implement espoused HR practices’. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

Team performance

We employed a four-item scale of Stewart & Barrick (Citation2000). Team performance was measured based on four categories (i.e. knowledge of tasks, quality of work, quantity of work, and overall performance) using a five-point behavior-anchored scale (ranging from 1 = somewhat below the requirements to 5 = consistently exceeds requirements). Cronbach’s alpha of this construct was 0.82.

Control variables

The current research took extra care in choosing control variables. Given much-hyped antecedents to FLMs’ involvement in HR are their perceptions of capacity and competency dimensions (e.g. Gilbert et al., Citation2015; Perry & Kulik, Citation2008), we controlled for support for HR implementation because extensive knowledge transfer and proper assistance provided over the implementation phase could improve not only behavioral control of FLMs but also, therefore, subsequent implementation efforts (Bos-Nehles & Meijerink, Citation2018; Ryu & Kim, Citation2013). The same logic applies to the distinction between support for HR implementation and FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices in predicting team performance via team-level HPWS. Sample items included, ‘The HR department has developed a well-coordinated set of policies, practices, and procedures (e.g. line manager training programs) to help ensure the effective implementation of HR practices in our team’, ‘The HR department provides with me useful and timely information regarding HR issues’, and ‘Guidance from the HR department is available over the implementation phase of espoused HR practices’. With the seven-item measure, a principal component factor analysis using varimax rotation was conducted, and the items were loaded on a single factor. Factor loadings ranged from 0.77 to .86. The total eigenvalue was 4.8, and the cumulative explained variance was 66.1%. And the results of CFA demonstrated an acceptable model fit (χ2 = 35.61, df = 13, χ2/df = 2.73, IFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.96, and RMSEA = 0.08) with Cronbach’s α of 0.92.

Also, the current study controlled for supportive FLM behavior, especially in an attempt to make the implementation-HPWS-performance link (i.e. Hypothesis 1) clear. It could be argued that individual employees working under a supportive manager may experience a more pleasant work environment and thus rate back highly of their FLM’s implementation effort and the local HPWS operation (Pak & Kim, Citation2018). By controlling for such behavior, we try to establish that 1) FLM’s HR implementation and supportiveness are indeed distinct behavioral constructs, and 2) specific implementation effort could explain greater variance in predicting team-level HPWS and subsequent team performance. Logical equivalence applies to the distinction between supportive behavior and intra-team acceptance (i.e. Hypotheses 1–3). To measure supportive FLM behavior, current research used Pak & Kim (Citation2018) five-item construct. Sample items included, ‘My team manager helps us make working on our tasks more pleasant’, and ‘My team manager helps us overcome problems,’ which stop us from carrying out our tasks. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

In addition, we controlled for management reports on HPWS to capture more meticulously the explanatory power of within-group dynamics (i.e. the hypothesized model). It could be suggested that team-level HPWS and subsequent team performance may simply be a product of the strength of intended HR practices at the firm level (c.f., Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004), not necessarily resulting from the degree of FLMs’ involvement in HR responsibilities. The same holds true for the relationship between intra-team acceptance and following FLMs’ implementation behavior. In such cases, the effect sizes of our proposed paths should be overridden or nullified by the organizational-level HRM system in the model, resulting in insignificant results. If otherwise, independent variables would still explain a significant variance in predicting the outcomes. Hence, when the authors initially visited target firms, a senior executive or HR manager was asked to rate the use of HPWS as part of the review process (i.e. to see if they have equivalent HRM systems in place before distributing surveys). According to Wright & Nishii (Citation2013), people occupying such positions may represent espoused HR practices (i.e. what is supposed to be) rather than actual HR practices (i.e. what is actually being done), which, then, further strengthens our core propositions when they receive empirical support. Espoused HR practices were measured with 27-item HPWS suggested by Patel et al. (Citation2013). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Besides, we controlled for such team-level variables as job group, team size, team meeting frequency, and task interdependence. It may be that differences among teams’ core functions within the organization could influence suggested relationships among study variables, and the size of the team is significantly associated with workgroup outcomes (Guzzo, Citation1988). Also, a team’s frequency of meetings and the level of task interdependence were found to influence the effectiveness of a team.

Data aggregation

Survey responses collected from individual employees were aggregated to the team-level. To investigate the appropriateness of aggregating employee responses, we calculated rwg values using a uniform distribution as the null distribution and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) (Bliese, Citation2000). The rwg value for intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices was 0.88, which is above the generally acceptable level of 0.70, and ICC(1), and ICC(2) for the construct were 0.33 and 0.72, respectively. The ICC(1) value exceeded the generally accepted cutoff level of 0.20 (Bliese, Citation2000). Plus, the ICC(2) was above the cutoff value of .60. Moreover, the result of the F-test for HWC was significant (F = 3.59, p < 0.001), indicating that data aggregation could be justified. In a similar vein, the values were calculated for FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices, and the results justified aggregation of responses (rwg = 0.90; ICC(1) = 0.27; ICC(2) = 0.65; F = 2.81, p < 0.001). The team-level aggregation for supportive FLM behavior was also justified with obtained values such as these (i.e. rwg = 0.73; ICC(1) = 0.22; ICC(2) = 0.61; F = 2.41, p < 0.001). Lastly, the ICC(1) value of 0.35 for team-level HPWS indicated that 35% of the variance in team-level HPWS among team members can be explained by their team membership (Bliese, Citation2000). ICC(2) for the construct was 0.73, and rwg 0.95 (F = 3.91, p < 0.001). Following this procedure, empirical support was found for the emergence of team-level HPWS within organizations.

Results

Correlations among study variables

presents correlations among study variables. Consistent with prediction, key constructs are significantly associated. Specifically, FLM’s implementation has significant associations with team-level HPWS (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) as well as team performance (r = 0.49, p < 0.01). It is noteworthy that FLM’s implementation is significantly relate to supportive FLM behavior (r = 0.46, p < 0.01) and support for HR implementation (r = 0.37, p < 0.01). In addition, the table shows that intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practice has significant correlations with FLMs’ all three cognitive evaluation dimensions (i.e. performance expectancy, r = 0.38, p < 0.01; effort expectancy, r = 0.42, p < 0.01; social influence, r = 0.48, p < 0.01), and with FLM’s subsequent implementation (r = 0.44, p < 0.01). Also, it should be noted that intra-team acceptance has significant associations with support for HR implementation (r = 0.33, p < 0.01) as well as supportive FLM behavior (r = 0.41, p < 0.01). Finally, it is shown that management report on HPWS is indeed significantly related to support for HR implementation (r = 0.19, p < 0.05) and FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices (r = 0.21, p < 0.05).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, correlations, and Cronbach’s alphas.

Validity of study variables

Prior to testing hypotheses, we conducted two sets of CFA model comparisons. One is intended for establishing discriminant validity among main variables pertinent to Hypothesis 1 (i.e. FLM’s implementation and team-level HPWS), including supportive FLM behavior and support for HR implementation (i.e. key controls). CFA generates several indices that enable comparing the model fit of the hypothesized factor structure with that of alternative ones (Hair et al., Citation2009). Excluding team performance, we ran four rounds of CFAs, and the results showed that the only four-factor model generated above-cutoff values. Specifically, it was found that χ2 = 90.51, df = 62, χ2/df = 1.46, IFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, and RMSEA = .07. According to prior research, values over 0.90 are acceptable for IFI, TLI, and CFI, and χ2/df should be below 3 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Also, RMSEA is established with less than .10. The results are particularly noteworthy in that FLMs’ behavioral fidelity during HR implementation and supportive FLM behavior are indeed two distinct concepts. Another set of CFA model comparisons involves main variables relating to Hypotheses 2–4. Similarly, we ran five rounds of CFAs and obtained values above cutoffs only in the five-factor model (χ2 = 112.93, df = 69, χ2/df = 1.64, IFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.92, and RMSEA = 0.08). Against guidelines, it was shown that only the hypothesized five-factor model justified further investigation.

In addition, the current research established convergent validity for hypothesized study variables. First, following that the factor loadings of each item should exceed the cutoff value of 0.50 (Hair et al., Citation2009), the authors looked through outputs and confirmed that factor loadings range from 0.53 to .91. Second, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE). The results indicated FLM’s implementation = 0.67, team-level HPWS = 0.53, team performance = 0.58, intra-team acceptance = 0.67, performance expectancy = 0.78, effort expectancy = 0.66, and social influence = 0.52, which are above cutoff values of .50. Third, calculated composite reliability (CR), obtained values are 0.90, 0.95, 0.81, 0.87, 0.89, 0.85, 0.86 in the same order as above, all of which exceed the recommended value of .70. The full list of survey items and factor loadings are provided in Appendix A.

Hypothesis tests

Hypotheses 1–3 state that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence mediate the relationship between Intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices and FLMs’ HR implementation behavior. presents the results of hierarchical regression analysis. Step 2 of model 2 shows that key controls have a significant impact on FLMs’ subsequent implementation (i.e. management report on HPWS, β = 0.13, p < 0.10; support for HR implementation, β = 0.23, p < 0.01; supportive FLM behavior, β = 0.15, p < 0.05). And, in step 3, it is confirmed that intra-team acceptance explains additional variance in predicting the outcome (β = 0.29, p < 0.01). In the final step, mediating variables inputted in the empirical model. Step 4 indicates that the effect size of intra-team acceptance reduced to a lesser significance level while all three mediators stand significantly positive, demonstrating partial mediation patterns (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986). The significance of mediating links was affirmed with Sobel (Citation1982)’s test (i.e. Hypothesis 2: Z = 2.98, p < 0.01; Hypothesis 3: Z = 3.47, p < 0.01; Hypothesis 4: Z = 3.12, p < 0.01), and, finally, re-affirmed with Hayes (Citation2017)’s PROCESS (i.e. Hypothesis 2: effect = 0.17, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.41]; Hypothesis 3: effect = 0.21, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.27]; Hypothesis 4: effect = 0.25, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.32]). The results indicate that there is support for all remaining hypotheses. Therefore, we concluded from the current dataset that intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices is significantly associated with all three cognitive dimensions of FLMs, which, in turn, are conducive to their subsequent implementation behavior.

Table 2. Results of hierarchical regression analysis.

Hypothesis 4 states that the positive relationship between FLM’s implementation of espoused HR practices and team performance is mediated by team-level HPWS. Comparably, Step 2 of model 1 indicates that key controls are significantly associated with team outcomes (i.e. management report on HPWS, β = 0.11, p < 0.10; support for HR implementation, β = 0.17, p < 0.05; supportive FLM behavior, β = 0.21, p < 0.05). After controlling for all the control variables, step 3 of model 1 demonstrates that FLM’s implementation still has a sizeable impact on team performance (β = 0.33, p < 0.01). In the following step, the effect size of FLM’s implementation noticeably diminishes (β = 0.24, p < 0.05) while the mediator, team-level HPWS, is significantly related to team performance (β = 0.41, p < 0.01). In Baron & Kenny (Citation1986)’s term, the relationship indicates partial mediation. The significance of the mediation effect was tested consistent with Sobel (Citation1982), demonstrating Z = 2.35 (p < 0.05). Additionally, we examined the indirect effect following PROCESS, as suggested by Hayes (Citation2017). The result presented that the estimate of FLMs’ implementation behavior on team performance via team-level HPWS is 0.25, not including zero (95% CI = [0.03, 0.31]; bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 10,000 bootstrap samples). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 has received support.

Discussion

Our study was motivated by observing that scholars often portray employees as the passive recipients of HR practices and underestimate their potential influence on FLMs’ enactment of HR policies and practices in their workgroups (c.f., Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Kou et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, scholars too often treat HPWS as an independent variable in their inquiries, which could make it quite difficult to directly capture the whys of variability within organizations (Pak & Kim, Citation2018; Wright & Nishii, Citation2013). Drawing on TPB (Ajzen, Citation1991) as the theoretical underpinning of our study, we proposed and tested a model to determine how intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices shapes FLMs’ attitudes (i.e. performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence), and their subsequent implementation behavior. The results further demonstrated that team-level HPWS mediates the relationship between FLMs’ implementation behavior and team performance.

Theoretical implications

With its unique findings, the present study extends the current discourse in several meaningful ways. Firstly, so far, support from the HR department has been viewed as the main resort for FLMs to be prepared for their HR duties (Bos-Nehles & Meijerink, Citation2018; Ryu & Kim, Citation2013), limiting our understanding of the motivational forces driving FLMs’ HR involvement. Yet, recent studies acknowledged that even a well-designed HRM system is vulnerable to failure if employees do not accept what is on the table, recommending scholars shed light on employees as important actors in the implementation process (Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Kehoe & Han, Citation2020). However, research continues to view employees placed at the receiving end (Kurdi-Nakra et al., Citation2022). In this light, our current research goes beyond this line of inquiry by unveiling subordinates’ potential force, which, in turn, leads FLMs to display favorable attitudes toward HR responsibilities.

Carefully following the footsteps of prior research, we reaffirmed that teams that develop their ability to function consensually have substantial power to change individuals’ attitudes and behavior, even including supervisors in charge (Ford & Seers, Citation2006). When team members interact, some form of shared understanding emerges among members, and managers become obliged to respond accordingly. This is in line with the logic of TPB, that is, attitudes and behaviors are determined by the networks in which individuals are embedded (Ajzen, Citation1991). Our findings present that the within-team consensus over espoused HR practices becomes a strong force that renders managers adjust to subordinates’ expectations. As such, our shift in attention and identifying subordinates’ agreement as a source for FLMs’ HR enactment behavior adds to the literature by placing employees back at the core of HR implementation processes.

More nuancedly, our findings revealed that FLMs’ performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence mediate the link between intra-team acceptance of HR practices and FLMs’ implementation behavior. Some scholars pointed out that meeting operational targets is the foremost priority of FLMs, and they may view HR duties as less critical (e.g. Brewster et al., Citation2015; Evans, Citation2017; Keegan et al., Citation2012). A closer look at this research stream portrays FLMs’ HR and operational tasks as two neatly separated or conflicting responsibilities (c.f., Evans, Citation2017; Gilbert et al., Citation2011). In this current study, contrary to this presumption, we demonstrated that if FLMs evaluate that involvement in HR duties is likely to boost workgroup outcomes (i.e. motivational significance), FLMs would exhibit greater willingness for HR involvement. According to TPB, exhibiting certain behavior arises from a person’s beliefs about the consequences of their performance (Ajzen, Citation1991). Given that enhancing team performance always comes at the top of the FLMs’ priorities, FLMs eagerly embrace HR duties when they are convinced that implementing HR practices enables unit goal achievement. Therefore, the results of our study imply that HR and technical responsibilities do not necessarily compete in the minds of FLMs.

As for effort expectancy, Ajzen (Citation1991) guides us that the amount of effort a person exerts to perform a behavior depends on their perceived mastery, control over the process, and the degree to which their effort will guarantee desirable outcomes. In this vein, intra-team acceptance of espoused HR practices not only assists FLMs in gaining clarity about their HR responsibilities but also subordinates endorse FLMs’ volition and power over HR enactment. Thus, FLMs feel higher behavioral control and self-efficacy over HR tasks, motivating them to put more effort into their implementation duties. This addresses Brewster et al. (Citation2015), Caldwell (Citation2003), and Evans’s (Citation2017) concerns, who claim FLMs’ ambiguity and lack of clarity over their HR duties is the fundamental impediment to their implementation.

Additionally, we found that team members actively communicate their expectations to their supervisors when within-team agreements over HRM have been established. Such social influence creates a strong normative pressure on FLMs to follow the team’s benefits and demands. FLMs would, therefore, display more effective implementation behavior in alignment with team agreements and perceived messages. This reaffirms Kehoe & Han (Citation2020) suggestion that after HR practices are designed at upper levels in the organization hierarchy, they would continuously and deliberately be reinterpreted or changed in the context of the team. This indeed adds new insight to the literature and a straightforward response to very recent scholars’ calls (e.g. Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Kou et al., Citation2022; Vossaert et al., Citation2022) for exploring potential forces that may impact FLMs’ attitudes and HR performance. Taken together, our study advances the literature on FLMs’ HR involvement and implementation behavior by revealing that FLMs’ implementation behavior is not solely driven by organizational enablers (i.e. support and facilitation from the HR department) yet partly emerges from the ongoing normative and psychological pressures within the team.

Meanwhile, scholars posited that if variability exists in the organization, exploring factors that precede HPWS merits more attention (Pak & Kim, Citation2018). In doing so, we established that implementing HPWS is mainly a team-level process (Guest & Bos-Nehles, Citation2013; Pak, Citation2022). In this light, we corroborated that team managers’ HR role as an agent for the organization may be a primary factor that forms team-level HPWS (Bowen & Ostroff, Citation2004; Purcell & Hutchinson, Citation2007). Our study contributes to this debate by illuminating that realized HPWS can largely be explained by the level of FLMs’ enactment behavior, and the higher utilization of HPWS at the team level results in improved outcomes. Therefore, this research integrated two seemingly distinct SHRM research streams (e.g. the HR devolution and HRM systems literature) into a single lucid framework by depicting that HPWS is the product of FLMs’ implementation behavior. This is not only generating new insight into understanding why variability occurs in HRM but also aiding in unwarping and navigating the black box between HRM and our desired outcomes.

Managerial implications

Our study offers recommendations for practitioners grappling with executing their HR tasks. It is quixotic to assume HR policies and practices can be transferred to FLMs for implementation purposes as intended in the HR department. Teams’ goal attainment is primarily a function of the quality of interaction among FLMs and their team members, and thereby, team members are significant others to FLMs. Hence, FLMs do not simply submit themselves to HR department prescriptions but strive to meet their team members’ demands. HR practitioners should welcome the belief that effective HR implementation results from triadic communications and agreement between HR, FLMs, and team members. Organizations should also seek to extend their view beyond common HR outcomes to include employees’ intersubjective perceptions and make efforts to explore and even shape employees’ collective beliefs. Indeed, the formulation of HR policy and practices should begin with a thorough analysis of the workgroup viewpoints and the prevalent local norms on the ground, which might govern the way tasks are carried out in the team. It can be achieved by engaging or consulting team managers in the design phase of espoused HPWS. If done so effectively, FLMs, as the implementers of espoused HR practices, could better contribute to effective HR implementation and team performance while not compromising what is delivered from top hierarchies to the line.

Further, FLMs’ HR involvement does not mean that FLMs give HR tasks higher value and priority than the operational agenda. Indeed, FLMs do not undertake HR duties unless they ensure that serving personnel assist them in their operational excellence and unit goal attainment. In this vein, the HR department should help FLMs comprehend why and how HR tasks enable them to achieve their goals. Accordingly, HR practitioners suggested that before loading FLMs with a long list of HR duties, first and foremost, harmonize HR tasks with FLMs’ operational tasks and raise FLMs’ awareness about the entanglement of their HR and operational duties. Additionally, given that FLMs have their own modus operandi in enacting HR practices along with signals and climates that team members create, it would be more fruitful to focus more on team-level HPWS, which eventually will manifest in the organization’s performance as a whole. In this respect, it is recommended to frequently monitor what HPWS means to team members and FLMS themselves rather than dictating designed organizational level-HPWS, resulting in high variation in organization.

Limitations and directions for future research

Our findings should be viewed with some caution, which offers meaningful avenues for future endeavours. To begin with, we collected data in Korea, which is characterized by a culture of high collectivism, implying that within-team agreements have a higher propensity to occur and solidify over time. In this sense, considering the generalizability of our findings, it should be interpreted cautiously for other contexts, and future research might replicate our proposed model in different cultural settings. In addition, this paper introduced intra-team agreement on the enactment of HPWS as a factor that makes team managers perceive normative pressure about rigorously enforcing intended HR practices, which predicts actual implementation behavior. Nonetheless, we encourage future research to provide a richer insight by exploring other potential forces that may influence FLMs’ enactment behavior. For instance, an FLM’s evaluation of other FLMs’ fidelity in HR implementation may also influence his/her decision to enact HR practices in an intended manner or commitment to HR roles in the workgroup. Plus, as part of our theoretical framework, we analyze FLMs’ implementation behaviors using within-team agreements; however, juxtaposing organization enablers with personal and within-team climate might offer a comprehensive and lucid framework for understanding FLMs’ implementation behaviors. For instance, it would be an insightful research avenue to test how FLMs react to conflicting signals from the HR department and their subordinates, specifically when FLMs’ personal values are discrepant and far apart from those of the HR department. The compelling evidence offered in this study thus opens up a new direction for understanding the multilateral pressures and underlying motivations that drive FLMs’ HR involvement and implementation behavior. Especially given that FLMs face paradoxical demands being brought forth by HR and top management teams on one side and employees under their supervision on the other, future research should merit more attention to examining how FLMs balance conflicting demands that can provide a valuable extension to the literature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs.

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Seidu, E. Y., & Otaye, L. E. (2012). Impact of high-performance work systems on individual-and branch-level performance: Test of a multilevel model of intermediate linkages. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025739

- Bai, P., Heidarian Ghaleh, H., Chang, H., Li, L., & Pak, J. (2023). The dark side of high-performance work systems and self-sacrificial leadership: An empirical examination. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 45(5), 1083–1097. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2022-0192

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis.

- Bos-Nehles, A. C., & Meijerink, J. G. (2018). HRM implementation by multiple HRM actors: A social exchange perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(22), 3068–3092. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1443958

- Bos-Nehles, A., & Van Riemsdijk, M. (2014). Innovating HRM implementation: The influence of organisational contingencies on the HRM role of line managers. In Human resource management, social innovation and technology (pp. 101–133). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. The Academy of Management Review, 29(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159029

- Brandl, J., Madsen, M. T., & Madsen, H. (2009). The perceived importance of HR duties to Danish line managers. Human Resource Management Journal, 19(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2009.00092.x

- Brewster, C., Brookes, M., & Gollan, P. J. (2015). The institutional antecedents of the assignment of HRM responsibilities to line managers. Human Resource Management, 54(4), 577–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21632

- Caldwell, R. (2003). The changing roles of personnel managers: Old ambiguities, new uncertainties. Journal of Management Studies, 40(4), 983–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00367

- Chang, H., & Pak, J. (2024). When HRM meets politics: Interactive effects of high-performance work systems, organizational politics, and political skill on job performance. Human Resource Management Journal,

- Chang, H., Son, S. Y., & Pak, J. (2020). How do leader–member interactions influence the HRM–performance relationship? A multiple exchange perspective. Human Performance, 33(4), 282–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2020.1746315

- Den Hartog, D. N., Boon, C., Verburg, R. M., & Croon, M. A. (2013). HRM, communication, satisfaction, and perceived performance: A cross-level test. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1637–1665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312440118

- Evans, S. (2017). HRM and front line managers: The influence of role stress. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(22), 3128–3148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1146786

- Fan, D., Huang, Y., & Timming, A. R. (2021). Team-level human resource attributions and performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(3), 753–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12330

- Ford, L. R., & Seers, A. (2006). Relational leadership and team climates: Pitting differentiation versus agreement. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(3), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.005

- Gardner, T. M., Wright, P. M., & Moynihan, L. M. (2011). The impact of motivation, empowerment, and skill-enhancing practices on aggregate voluntary turnover: The mediating effect of collective affective commitment. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 315–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01212.x

- Gilbert, C., De Winne, S., & Sels, L. (2011). The influence of line managers and HR department on employees’ affective commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(8), 1618–1637. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.565646

- Gilbert, C., De Winne, S., & Sels, L. (2015). Strong HRM processes and line managers’ effective HRM implementation: A balanced view. Human Resource Management Journal, 25(4), 600–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12088

- Gist, M. E. (1987). Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. The Academy of Management Review, 12(3), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.2307/258514

- Gjerde, S., & Alvesson, M. (2020). Sandwiched: Exploring role and identity of middle managers in the genuine middle. Human Relations, 73(1), 124–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718823243

- González-Romá, V., & Hernández, A. (2014). Climate uniformity: Its influence on team communication quality, task conflict, and team performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1042–1058. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037868

- González-Romá, V., Fortes-Ferreira, L., & Peiró, J. M. (2009). Team climate, climate strength and team performance. A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(3), 511–536. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X370025

- Guest, D., & Bos-Nehles, A. (2013). Human resource management and performance: The role of effective implementation. In Human resource Management and Performance (5th ed): Achievements and Challenges. (pp. 79–96). Wiley.

- Guest, D., & King, Z. (2004). Power, innovation and problem-solving: The personnel managers’ three steps to heaven? Journal of Management Studies, 41(3), 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00438.x

- Guzzo, R. A. (1988). Financial incentives and their varying effects on productivity. In Psychology and productivity (pp. 81–92). Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. Bergen County.

- Hall, L., & Torrington, D. (1998). Letting go or holding on–the devolution of operational personnel activities. Human Resource Management Journal, 8(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.1998.tb00158.x

- Han, J. H., Liao, H., Taylor, M. S., & Kim, S. (2018). Effects of high-performance work systems on transformational leadership and team performance: Investigating the moderating roles of organizational orientations. Human Resource Management, 57(5), 1065–1082. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21886

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Keegan, A., Huemann, M., & Turner, J. R. (2012). Beyond the line: Exploring the HRM responsibilities of line managers, project managers and the HRM department in four project-oriented companies in the Netherlands, Austria, the UK and the USA. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(15), 3085–3104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.610937

- Kehoe, R. R., & Han, J. H. (2020). An expanded conceptualization of line managers’ involvement in human resource management. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(2), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000426

- Kou, X., Kurdi-Nakra, H., & Pak, J. (2022). The framework of first-line manager’s HR role identity: A Multi-actor HR involvement perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 32(4), 100898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100898

- Kurdi-Nakra, H., Kou, X., & Pak, J. (2022). The road taken and the path forward for HR devolution research: An evolutionary review. Human Resource Management, 61(2), 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22091

- Lee, H. W., Pak, J., Kim, S., & Li, L. Z. (2019). Effects of human resource management systems on employee proactivity and group innovation. Journal of Management, 45(2), 819–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316680029

- Liao, C., Wayne, S. J., & Rousseau, D. M. (2016). Idiosyncratic deals in contemporary organizations: A qualitative and meta-analytical review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(S1), S9–S29. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1959

- Liao, H., Toya, K., Lepak, D. P., & Hong, Y. (2009). Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013504

- Ma, Z., Gong, Y., Long, L., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Team-level high-performance work systems, self-efficacy and creativity: Differential moderating roles of person–job fit and goal difficulty. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(2), 478–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1854816

- Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00121.x

- Op de Beeck, S., Wynen, J., & Hondeghem, A. (2018). Explaining effective HRM implementation: A middle versus first-line management perspective. Public Personnel Management, 47(2), 144–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026018760931

- Pak, J. (2022). Capturing variability of high-performance work systems within organizations: The role of team manager’s person-HRM fit and climate for HR implementation and subsequent implementation behavior. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(4), 759–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12467

- Pak, J., & Chang, H. (2023). Personal disposition as the source of variability in the hrm-performance relationship: The moderating effects of conscientiousness on the relationship between high-commitment work system and employee outcome. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(20), 3933–3962. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2163464

- Pak, J., & Kim, S. (2018). Team manager’s implementation, high performance work systems intensity, and performance: A multilevel investigation. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2690–2715. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316646829

- Pak, J., Chung, G. H., Kim, S., & Choi, J. N. (2016). Sources and consequences of HRM gap: The Korean experience. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Patel, P. C., Messersmith, J. G., & Lepak, D. P. (2013). Walking the tightrope: An assessment of the relationship between high-performance work systems and organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1420–1442. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0255

- Perrigino, M. B., Chen, H., Dunford, B. B., & Pratt, B. R. (2021). If we see, will we agree? Unpacking the complex relationship between stimuli and team climate strength. Academy of Management Annals, 15(1), 151–187. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2019.0067

- Perry, E. L., & Kulik, C. T. (2008). The devolution of HR to the line: Implications for perceptions of people management effectiveness. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(2), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701799838

- Powell, T. C., & Dent-Micallef, A. (1997). Information technology as competitive advantage: The role of human, business, and technology resources. Strategic Management Journal, 18(5), 375–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199705)18:5<375::AID-SMJ876>3.0.CO;2-7

- Purcell, J., & Hutchinson, S. (2007). Front-line managers as agents in the HRM-performance causal chain: Theory, analysis and evidence. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2007.00022.x

- Renwick, D. (2003). Line manager involvement in HRM: An inside view. Employee Relations, 25(3), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450310475856

- Ryu, S., & Kim, S. (2013). First-line managers’ HR involvement and HR effectiveness: The case of South Korea. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 947–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21576

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/270723

- Stewart, G. L., & Barrick, M. R. (2000). Team structure and performance: Assessing the mediating role of intrateam process and the moderating role of task type. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556372

- Sun, L. Y., Aryee, S., & Law, K. S. (2007). High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 558–577. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25525821

- Takeuchi, R., Lepak, D. P., Wang, H., & Takeuchi, K. (2007). An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1069–1083. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1069

- Trullen, J., Stirpe, L., Bonache, J., & Valverde, M. (2016). The HR department’s contribution to line managers’ effective implementation of HR practices. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(4), 449–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12116

- Van Beurden, J., Van De Voorde, K., & Van Veldhoven, M. (2021). The employee perspective on HR practices: A systematic literature review, integration and outlook. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(2), 359–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1759671

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 3, 27, 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Vermeeren, B. (2014). Variability in HRM implementation among line managers and its effect on performance: A 2-1-2 mediational multilevel approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(22), 3039–3059. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.934891

- Vossaert, L., Anseel, F., Collewaert, V., & Foss, N. J. (2022). ‘There’s many a slip “twixt the cup and the lip’: HR management practices and firm performance. Journal of Management Studies, 59(3), 660–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12781

- Wang, Y., Kim, S., Rafferty, A., & Sanders, K. (2020). Employee perceptions of HR practices: A critical review and future directions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(1), 128–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1674360

- Weick, K. E., & Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations (Vol. 3, pp. 1–231). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

- Whittaker, S., & Marchington, M. (2003). Devolving HR responsibility to the line: Threat, opportunity or partnership? Employee Relations, 25(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450310475847

- Woodrow, C., & Guest, D. E. (2014). When good HR gets bad results: Exploring the challenge of HR implementation in the case of workplace bullying. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12021

- Wright, P., & Nishii, L. (2013). Strategic HRM and organizational behaviour: Integrating multiple levels of Analysis. In Paauwe, J. G. and Wright, P. (Eds.), HRM and performance. Achievements and challenges (pp. 97–110). Wiley.