Abstract

Felt accountability, the perceived expectation that one’s decisions and actions will be evaluated and rewarded or sanctioned, is a key driver of human behaviour and impacts work-related outcomes such as unethical behaviour and job satisfaction. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the importance of low-status expatriates (LSEs), a vulnerable and neglected group, which is often employed under challenging working conditions in low-status occupations. In this paper, we explore how LSEs experience and manage accountabilities in their often-precarious working lives. We draw on 36 qualitative interviews with LSEs employed in Germany. The data were analysed using a directed content analysis method. Our findings highlight that while LSEs feel less accountable towards stakeholders within their organisation, they experience accountabilities from multiple stakeholders outside their organisation. We demonstrate that while LSEs consider work-related accountabilities, their key accountabilities are rooted in individuals’ private lives and can lead to higher degrees of accountability intensity. This study provides unique insights into the importance of private life accountabilities and how these intersect with accountabilities at work. We offer a revised framework of accountability that includes private life as an important dimension to enhance its applicability to LSEs.

Introduction

Accountability is a crucial element of human resource management (HRM), which is typically responsible for the implementation of policies and practices that ensure individual accountability across the organisation. These regulations help minimise the risk of legal liability and behaviours that are detrimental to organisational goals and values (Frink et al., Citation2008). Accountability is important for societies and organisations, with authors highlighting that an absence of accountability can lead to organisational scandals, individual failures and unethical behaviours (Hall et al., Citation2007; Mitchell et al., Citation1998). At the individual level, accountability is defined as the “perceived expectation that one’s decisions or actions will be evaluated by a salient audience and that rewards or sanctions are believed to be contingent on this expected evaluation” (Hall & Ferris, Citation2011, p. 134). It is also referred to as felt accountability or simply accountability (Hall et al., Citation2017). Previous research has highlighted the positive and negative consequences of accountability for the individual and the employing organisation (Ferris et al., Citation1995; Frink & Klimoski, Citation1998; Hochwarter et al., Citation2007). However, the authors focused mainly on the experience of accountability in the context of middle-class white-collar workers, thereby neglecting the stressful and difficult employment and life circumstances faced by individuals of lower status, especially those who are internationally mobile (Haak-Saheem & Brewster, Citation2017).

The number of individuals who work outside their home country is constantly on the rise, and recent estimates suggest this figure to be 169 million people worldwide (ILO., Citation2021). Many of these workers are expatriates who remain in the host country only for the purpose of work for a specified period of time and do not intend to settle. There is a large body of literature on highly skilled expatriates who occupy managerial or leadership positions in multinational companies (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2019; McNulty & Brewster, Citation2017). However, another group of expatriates that often work in less prominent and low social status occupations has been largely overlooked; these are referred to as low-status expatriates (LSEs) (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2019). LSEs often hold essential or even life-sustaining positions in healthcare, elder care, agriculture, construction, hospitality and logistics industries (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2021). Although LSEs are instrumental in maintaining a functional host country society, their employment conditions are challenging and often precarious and they receive little appreciation for their work (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022; Holtbrügge, Citation2021; Özçelik et al., Citation2019). Despite the vital role of LSEs for many organisations and their host countries in general, little attention has been paid to the subjective factors that shape accountabilities which LSEs experience in their employment abroad. Instead, existing frameworks of accountability focus mainly on employees of higher socioeconomic status.

The combination of precarious employment conditions, physical detachment from family and friends and high levels of work-related stress might make it even more difficult for LSEs to balance multiple accountabilities between stakeholders than for more privileged individuals. As a result, it is unclear how LSEs experience accountabilities and the strategies they use to manage and prioritise accountabilities between multiple stakeholders. However, understanding how LSEs perceive and prioritise accountabilities is important for HR not only to ensure accountable behaviours across the workforce but also for employers to support their workers’ health and well-being. By understanding the perception of accountabilities of LSEs, HR can introduce and develop practices and accountability procedures that aim to increase commitment, reduce levels of distress and potentially improve performance and retention. Therefore, this paper aims to answer the following two research questions: (1) How do LSEs experience accountabilities in their daily lives? (2) How do LSEs manage and prioritise these accountabilities? Informed by the features of the accountability environment by Hall et al. (Citation2007) we draw on 36 in-depth qualitative interviews to explore how LSEs experience and manage accountabilities in the workplace.

Our study has important theoretical and practical implications. First, by focusing on the historically under-research group of LSEs, our paper highlights shortcomings in current theory and raises questions about whether existing accountability conceptualisations can be applied to LSEs without modification. We demonstrate that the perception of accountabilities by expatriates in low-status occupations may differ from those reported in previous research, highlighting a general lack of felt accountabilities of LSEs towards their work and their employer. Second, the findings highlight the need to integrate accountabilities outside the workplace into current discussions on accountability in order to consider the perceptions of the wider workforce. Third, this paper offers a revised and more integrated framework of the features of the accountability environment. This framework includes the consideration of accountabilities from private lives and self-accountabilities, making it more nuanced and applicable to a wider workforce. This framework can help organisations to review their HR policies to enable LSEs to balance work and private life accountabilities by implementing expatriate benefit policies and support systems to reduce distress for their international low-wage workers.

Literature review

Accountability

Traditional definitions of accountability have concentrated on organisationally imposed accountability systems for guiding and controlling the attitudes and behaviours of individuals within the organisation, such as those found in HRM systems (Hall et al., Citation2003). Specifically, organisations implement formal regulatory guidelines and processes (e.g. internal or external audits or performance appraisal systems) to operate efficiently in pursuit of company goals by using reward and punishment systems to impose accountabilities. In this context, accountability was conceptualised as an objective accountability (Ferris et al., Citation1995), in which employees feel accountable to salient stakeholders for their actions. However, the distinction between to whom and for what an employee feels accountable is the basis for continuing discussions. A different perspective on accountability relies on the phenomenological view of accountability (Tetlock, Citation1985, Citation1992). In contrast to the assumption that formal factors are felt by all employees in the same objective way, Frink and Klimoski (Citation1998) argue that the personal interpretation of these accountabilities is the underlying driver of individual decisions and behaviours. The authors referred to this as felt accountability or simply as accountability, which can be derived equally from formal and informal sources. Accountability is based on the actor and their individual perceptions and interpretations of accountabilities. As such, it can affect individual behaviours and outcomes, including motivation (Enzle & Anderson, Citation1993), engagement (Cullinane et al., Citation2014), job satisfaction (Lanivich et al., Citation2010; Wikhamn & Hall, Citation2014) and job performance (Hochwarter et al., Citation2007; Mero et al., Citation2014).

The perceptual conceptualisation of felt accountability identifies distinguishable dimensions, with a focus on answerability as the key dimension of accountability (Hall & Ferris, Citation2011). However, Han and Perry (Citation2020a, Citation2020b) argued that one dimension does not provide a holistic understanding of the micro-foundations of employee accountability. Therefore, Han and Perry (Citation2020a) conceptualised a multidimensional model of felt accountability that encompasses five dimensions: attributability, observability, evaluability, answerability and consequentiality. According to the authors, accountability is higher if individuals perceive that (1) their actions are attributable to them (attributability); (2) activities can be observed by others (observability); (3) actions are evaluated based on specific criteria (evaluability); (4) they are answerable for their actions (answerability); and (5) there are consequences (rewards or sanctions) for their activities (consequentiality).

This framework suggests that when employees anticipate and perceive the presence of these factors, they feel more accountable for their actions. These five dimensions are, therefore, internal representations (interpretations) of externally imposed accountability systems with the aim of directing (encourage/prevent) accountability-dependent behaviours (Ferris et al., Citation1995; Frink & Klimoski, Citation1998). These dimensions contribute to understanding an individual’s subjective experience of being accountable through the internalisation of existing accountability systems. To provide insights into the characteristics that influence the perception and interpretation of accountability, Hall et al. (Citation2007) summarised four features of the immediate accountability environment, namely: source, focus, salience and intensity.

First, source typically refers to stakeholders, by whom individuals are held accountable. Employees are accountable to multiple formal and informal sources in the context of the organisation that are either organisational (e.g. managers, co-workers) or work-related (e.g. clients, patients). Frink and Klimoski (Citation1998) described the complexity arising from these multiple sources of accountability as a web of accountabilities. The authors highlighted that individuals may feel more or less accountable depending on how they interpret the role of the source of accountability. Low and high levels of accountability can have positive effects and may lead to higher levels of extra-role behaviour (Hall & Ferris, Citation2011). Other studies have reported that if individuals perceive very high levels of accountability, it can result in distress, negatively impacting well-being and performance (Davis et al., Citation2007; Hall et al., Citation2017). Second, focus describes the extent to which an employee is held accountable for the quality of the outcome (quality or quantity) of their decisions and behaviours, or if they are held accountable for the process (adhering to standards and procedures) (Hall et al., Citation2007; Siegel-Jacobs & Yates, Citation1996). Previous research highlighted the potential negative effects of outcome accountabilities on the quality of decisions and increased levels of distress (Siegel-Jacobs & Yates, Citation1996). However, the strict distinction between process and outcome accountabilities has been questioned (Schulz-Hardt et al., Citation2021; Sharon et al., Citation2022) by Seidenfeld (Citation2001), arguing that in the field, it is often difficult to distinguish between pure process and outcome accountability. Third, accountability salience is linked to the extent to which individuals are accountable for significant outcomes or consequences (Hall et al., Citation2007). If employees believe that their behaviour and decisions have an important impact or can help to avoid harmful outcomes, they will engage in a higher level of cognitive effort (Hall et al., Citation2007). Intensity outlines the degree to which individuals are accountable to different stakeholders in their web of accountabilities (Frink & Klimoski, Citation1998). These accountabilities can be experienced at various intensities, depending on what the individual is held accountable for (multiple outcomes) and by whom (multiple actors) (Aleksovska et al., Citation2019). These conditions have been identified as potential stressors for individuals, as they require prioritisation and, thus, affect employees’ interpretation of various accountabilities (Hall et al., Citation2006; Lanivich et al., Citation2010). As part of this process, not only are accountabilities evaluated but also prioritised based on the perception of their significance to the individual and the impression they make on others (Hall et al., Citation2007).

Accountability has been argued to be of crucial importance for organisations to ensure compliance behaviours and prevent acts that are potentially detrimental to the individual and the organisation. Therefore, it is essential for organisations to understand how employees experience, and why they prioritise, accountabilities from different sources. Despite an increasing number of studies evaluating accountabilities in the organisational context, previous studies have focused almost entirely on white-collar workers typically working in high-status and high-pay occupations (Hall et al., Citation2017; Han & Perry, Citation2020a). The strong emphasis of previous research on individuals of higher socio-economic status neglects the situation of much of the international workforce.

Low-status expatriates

A large proportion of the international workforce in developed economies is employed in lower status occupations, such as cleaning, manufacturing and food production and processing (Haak-Saheem & Brewster, Citation2017; Sharon et al., Citation2022). Often, these individuals find employment abroad as expatriates in low-status occupations and are faced with a different and often more challenging work and life situation than employees of a higher socioeconomic status (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2019; Sunguh et al., Citation2019). Although LSEs constitute a substantial part of the workforce in their host countries, few studies have evaluated their lived experiences in the host country (Haak-Saheem & Brewster, Citation2017; Özçelik et al., Citation2019), with only a few studies exploring the work and life situation of LSEs in specific contexts such as the Middle East (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2021; Holtbrügge, Citation2021), Germany (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022) and China (Sunguh et al., Citation2019). In contrast to migrant workers, LSEs do not intend to settle in the host country but remain only for the purpose and duration of their employment (Holtbrügge, Citation2021).

In the past, research has focused on expatriates who are sent by an organisation as well as self-initiated expatriates of higher socioeconomic status (SIEs) (Doherty et al., Citation2011). SIEs typically pursue careers in foreign countries to gain international experience, follow cultural and personal interests and seize career development opportunities (Doherty et al., Citation2011; Shaffer et al., Citation2012). In contrast, LSEs are often driven by financial difficulties and a lack of employment opportunities in their home countries. Therefore, LSEs engage in a different form of international experiences, and the aims of their self-initiated expatriation differ from those experienced by SIEs (Holtbrügge, Citation2021). These contracts are often characterised by low pay, little job security and difficult working conditions (Holtbrügge, Citation2021; Özçelik et al., Citation2019). Haist and Kurth (Citation2022) highlighted the imbalance of high levels of distress and insufficient organisational support and support from outside the organisation available to LSEs. These factors, in combination with precarious employment conditions and physical distance from their home country society, friends and extended family (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022), affect the well-being, the psychological contract and work and life satisfaction of LSEs (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2021; Abbas et al., Citation2021). Considering the vital role of LSEs for life-sustaining industries and the need to retain these essential workers to maintain society’s functioning, there is a need to better understand how LSEs experience their work and how they experience, manage and respond to multi-faceted accountabilities. This is particularly important because lower levels of accountability have been shown to be related to emotional exhaustion, higher job tension and lower levels of commitment towards the organisation (Hall et al., Citation2006; Lanivich et al., Citation2010) which can potentially negatively affect the individual and the employing organisation.

LSEs and accountabilities

Previous models of accountability are used to provide theoretical explanations for individual accountability in organisations (Hall et al., Citation2007; Han & Perry, Citation2020b). These frameworks are based on individuals in the public sector and other privileged employees of higher socioeconomic status who experience different employment circumstances than individuals working in less prominent and secure positions such as LSEs. Therefore, the influencing factors and the experience of accountability might be different for LSEs, as they are not only subject to different working conditions that are characterised by exploitation, low job security and pay, but they also experience a strong intersection between work and private life (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). Considering the features of the accountability environment, LSEs are likely to differ from traditional accountability research samples in three ways. First, LSEs are employed in low-status occupations in a foreign country and often place a high importance on their private family lives. Due to their differing circumstances and their employment situation, LSEs might experience different accountability sources to those experienced by high-status employees. Second, due to the nature of their work, LSEs might perceive a higher accountability salience for the outcomes they are held accountable. Third, LSEs might experience a different level of accountability intensity due to the importance of their work for their host country stay and the nature of their jobs.

The strong focus on factors in the private lives of LSEs and especially the family has been shown to be a critical point for re-evaluating existing frameworks depicting stress and well-being of LSEs (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022; Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). Fedi et al. (Citation2016) reported that low-status workers experience more issues in relation to work due to organisational characteristics and conflicts in the work-family balance than their high-status counterparts. As a result of the different situation and external environment, LSEs might perceive and interpret accountabilities initiated by HR, the organisation and supervisors/management differently to traditionally researched white-collar workers. Family has been shown to be a deciding factor for successful expatriate assignments and the retention of SIEs due to family members adjusting (or not adjusting) to the new country (Shaffer et al., Citation2001). In contrast to SIEs, there are many LSEs who go abroad and live and work by themselves without their family accompanying them (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). For LSEs, previous studies have shown that family is an even more important factor, with Haak-Saheem et al. (Citation2022) pointing out that LSEs are less concerned about themselves but focus largely on the well-being of their families. This is often the main reason for their expatriation in the first place (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). As such, families might act as an additional source of stress and potential audience in the perception of accountabilities of LSEs. Therefore, there is a need to consider the importance of the family when evaluating the situation, experiences and perception of accountabilities of LSEs.

LSEs are often employed as key workers who are essential for the functioning of organisations and society and are important for outcomes that can often be considered significant (Haak-Saheem & Brewster, Citation2017; Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2019). Especially in the elder care and healthcare context, mistakes can have severe consequences and might therefore result in LSEs feeling more accountable. Also, LSEs typically come to the host country to enable them to financially support their families (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022; Haist & Kurth, Citation2022), meaning that they are dependent on income and, thus, the job. Therefore, LSEs might experience higher degrees of accountability salience across low-status occupations, because the overall aim is to achieve better living conditions for their families (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022). Haak-Saheem et al. (Citation2022) show that there are spill-over effects from LSEs’ private lives to the experience and evaluation of work. Meuris and Leana (Citation2018) highlighted that individuals who work under financial precarity experience higher levels of distress, are less focused on work and are therefore less likely to perform at the expected or desired level. These extensive webs of potentially competing accountabilities, both inside and outside of the organisation, might therefore be felt more acutely by LSEs than by the traditionally researched white-collar workers. Adding such additional private life accountabilities as an important factor in LSE’s work lives might also impact their experience of accountability intensity.

In light of the importance of the family in LSE’s daily lives, they might experience a higher level of accountability intensity as the number of accountability sources outside the organisation increases. At the same time, LSEs might not only be formally accountable towards different outcomes, such as cleaning to a certain quality (customer), cleaning a certain number of houses (organisation and supervisor) and adhering to safeguarding procedures (policies). LSEs are also informally accountable for their mental and physical well-being and their personal internally embraced beliefs and values, namely self-accountability. Self-accountability is defined as “the need to justify one’s actions and decisions to oneself to confirm or enhance a self-identity or image shaped by strongly held beliefs and values” (Dhiman et al., 2018). Self-accountability does not rely on evaluation from an external salient audience (Frink & Klimoski, Citation2004; Schlenker & Weigold, Citation1989).

Many of these factors were highlighted as being particularly important for individuals employed in low-status occupations over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022; Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). Considering the combination of a challenging work and life situation of LSEs, insufficient support from outside the organisation (i.e. policy actors such as the governments and NGOs), a lack of organisational support (e.g. supervisors, HR, or organisational policies) (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022) and a strong focus on the family, the present study attempts to explore how LSEs experience, manage and juggle potentially competing accountabilities in their daily lives. Therefore, this paper aims to answer the following two research questions: (1) How do LSEs experience accountabilities in their daily lives? (2) How do LSEs manage and prioritise these accountabilities?

Methodology and methods

This study used an interpretive research design (Walsham, Citation2006) to explore how the marginalised group of LSEs experience and balance accountabilities at work. The ultimate aim of this approach was to understand the lived experiences of accountabilities of LSEs and develop current theories based on these realities (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015). Qualitatively exploring the case of LSEs allows this study to capture the individual perspectives and experiences of accountabilities of those who work in the German low-income sector separated from their home-countries. In doing so, this study can elaborate on existing theories of accountability and explore its application in the context of marginalised workers at the bottom of the social and organisational hierarchy (Charmaz, Citation2008; Holtbrügge, Citation2021).

Research setting and sample

In Europe, where movement is relatively unrestricted between countries, LSEs from poorer European countries (i.e. counties with low GDP and low average wage) seek work opportunities in wealthier European countries (i.e. countries with high GDP and high average wage), especially in Germany and the Netherlands where jobs are more readily available (Appelbaum & Schmitt, Citation2009). In particular, the German labour market is an attractive destination for LSEs as there is a high demand for labour in the low-wage sector. As of 2017, the low-wage sector accounts for almost 25% of the German labour market, of which it is estimated that approximately 17% of the jobs are occupied by LSEs (Grabka & Schröder, Citation2019). These jobs are often characterised by unethical practices towards international workers (Haist & Novotný, Citation2023). These employees often earn below the national minimum wage threshold and work in precarious employment conditions away from their home country and experience constant pressure due to job insecurity (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2019; Holtbrügge, Citation2021). Therefore, Germany is an ideal context for this study to provide further insights into the lived experiences of the LSE workforce.

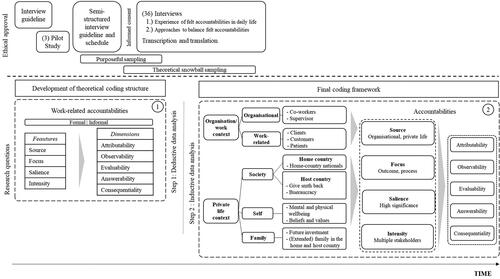

Gaining access to LSEs is challenging due to their precarious situation in the labour market, the fear of disclosing private information and the resulting potential repercussions from their employers (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). LSEs are a marginalised and hard to reach population due to their limited interaction and connection with other communities (both in the host and home countries). Therefore, a purposeful sampling method was used that initially relied on personal business acquaintance contacts and intermediaries and was followed by a snowball sampling technique to contact further LSEs working in Germany who fit the theoretical sampling frame of this study (Pratt, Citation2009). This approach is most effective to access hard-to-reach populations and is in line with previous qualitative research (Abdelhady & Al Ariss, Citation2023; Peltokorpi & Froese, Citation2009). To differentiate LSEs from other groups of expatriates, migrant workers and refugees, the following inclusion criteria were applied; LSEs need to (1) be from a European country, (2) have worked in Germany for at least six months and a maximum of 10 years, (3) do not intent to settle in the host country and (4) be employed in the low-wage sector or in low-status occupations (Haak-Saheem & Brewster, Citation2017; Holtbrügge, Citation2021; Sunguh et al., Citation2019). We restricted our sample to European participants to minimise the variation of the context and to reduce the potential for confusion between LSEs, migrant workers and refugees (Andresen et al., Citation2014). Following pilot interviews with three LSEs connected to one of the authors, the final sample for this study consisted of 36 LSEs from 12 countries (21–63 years of age) currently employed in Germany (). illustrates the data collection and analysis process of this research. Due to the explorative nature of this research, a sample size of 36 is considered adequate to answer the research questions (Marshall et al., Citation2015; Saunders & Townsend, Citation2016). Moreover, the final sample includes a diverse group of LSEs, who work in different industries across Germany that are known for their precarious employment conditions (e.g. elder care and healthcare, cleaning and construction).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were chosen as the preferred method for data collection in this study, as it aims to explore the individual experiences of accountabilities of LSEs that can be depicted in-depth in an interview setting (Alvesson & Deetz, Citation2000). Moreover, LSEs tend to avoid disclosing details of their personal and working lives as they fear repercussions from their employers for discussing their personal circumstances. (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). Therefore, conducting interviews was the only feasible way of collecting in-depth qualitative data. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in-person, via telephone and video calls lasting between 40 and 90 min. Although interviewing participants face-to-face is often seen as a superior method of collecting qualitative data due to the potential to elicit more detailed responses, telephone and video-supported techniques have been shown to be equally effective at eliciting rich data (Archibald et al., Citation2019). Additionally, these techniques offered participants the chance to answer questions in a private, confidential and COVID-19-safe environment. This was particularly important for some of our participants as they feared negative consequences from their employers when participating in this research. Interviews took place from February 2021 to May 2022. All participants primary language at work is German (17 are fluent in German), whereas outside of work most communicate almost exclusively in their native language. While most interviews were conducted in German, nine of the interviews were supported by a simultaneous translator and performed in the native language of the participants to ensure full understanding of the topics and questions and were then translated into English. To ensure equivalence, the audio-recorded data was back-translated by a second translator from English into the native language and checked for consistency (Cascio, Citation2012). All interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

The semi-structured interview schedule was developed following Kvale and Brinkmann (Citation2015) guidance. The main questions were developed initially to explore the individuals’ experiences of accountabilities that are answered by each interviewee, and which are followed by probes and prompts reacting and further generating insights as they emerge during conversations with participants (Pratt et al., Citation2019). Prior to data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the University’s Ethics committee. Before each interview, participants signed a consent form either electronically or physically. The informed consent outlined the objective of the research and the terms of participation, including the confidential and anonymous nature of this study. After obtaining informed consent and establishing the demographic characteristics of each participant, the interviews covered two key areas. First, interviews established the range of accountabilities that participants experienced and perceived in their daily lives. Second, we explored the approaches LSEs use to balance these felt accountabilities. This part of the interview was used to prompt participants to reflect on the challenges they experience in prioritising between their multiple accountabilities.

Data analysis

An initial coding framework was developed that was guided by the research questions and based on an extensive literature review on accountability (Miles et al., Citation2020; Tlaiss & Al Waqfi, Citation2022). The initial coding framework was based on the four features of the accountability environment—source, focus, salience and intensity—by Hall et al. (Citation2006) and the five dimensions of accountability (Han & Perry, Citation2020b), namely answerability, observability, attributability, evaluability and consequentiality (). Drawing on this coding framework, we analysed the data using a directed two-step content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). This analysis method initially used a deductive approach to code the data along the themes established in the coding framework and, thus, drawing on first order codes by applying existing theory on accountability to the context of LSEs. All data that could not be coded into these predefined first order codes were highlighted in the first step. In a second step, the uncoded content was analysed using an inductive approach, exploring the experience of accountabilities based on the lived experiences of LSEs. These newly established second order codes were thematically categorised and added to the coding framework (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). The data were coded by all authors independently and the final coding framework () was derived upon a thorough discussion and agreement between the five coders.

Findings

The findings of this research emerged from exploring the following research questions: (1) How do LSEs experience accountabilities in their daily lives? (2) How do LSEs manage and prioritise these accountabilities? The findings highlight that (a) there is less focus on accountabilities towards organisational stakeholders within the organisation than outlined in previous literature, (b) key accountabilities of LSEs are perceived towards their families and other stakeholders such as patients and customers, (c) accountabilities in the work context are strongly connected to accountabilities in LSEs’ private lives and (d) the intersection of private and work life makes it difficult for LSEs to balance between these two areas of accountabilities. Findings are structured along the four features of the accountability environment and the dimensions of accountability highlighted were applicable for providing a holistic overview of implications and perceptions of accountability.

Source

Most participants perceived accountability as a constant pressure to be able to justify their actions and decision at any point of time to different stakeholders and the fear of making a mistake and being accountable for it. Many LSEs reported that the feeling of being constantly observed, evaluated and answerable for their actions, resulted in the fear of potential negative consequences when not satisfying all perceived work-related accountabilities.

When asked about the sources that participants are being held accountable to, they talked mainly about how specific individuals were able to evaluate (evaluability) their work. These accountabilities are directly linked to persons employed by the organisation. In this context, participants discussed their supervisors, line managers and co-workers as key sources within their organisational environment. Moreover, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, organisations implemented additional formal safety and hygiene measures stipulated by the German government, which were mentioned by some participants. Nevertheless, accountabilities towards organisational procedures, policies and HR were not, or only briefly, reported by most participants, indicating that the employer is not considered a crucial accountability source in the perception of LSEs. In contrast, for participants working in the health and elder care professionals who do not have product-related outcomes, LSEs highlighted that they feel strongly accountable for the health and well-being of their patients rather than the employing organisation itself. This was especially apparent when the participants mentioned the situation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviewee 29 said:

I need to do the job well, even if there is the COVID-19 pandemic […] I am accountable for the well-being of these people, and I must do everything they need.

In addition to work-related accountabilities, interviewees consistently referred to felt accountabilities towards their family and friends in their home and host countries. The most important accountability reported by LSEs was the well-being of their families, especially their children. Interviewees emphasised that whilst working in Germany provides better work opportunities, they chose this step as they feel accountable for their family. Interviewee 19 said:

My children shall have a better life. They shall have a better job, and thus, I have to make sure that they have a better future.

My family is still in the home country. I had the chance to come to Germany and help my family financially. That is what I must do and that is why I try to work more than necessary.

I feel like I have to do the extra work for my clients, because I could not look at myself in the mirror if I would not spend that extra time giving them the support they need, even if I am not getting paid for it. I have to do it for myself as well.

Focus

When making decisions, participants were not always clear about whether their experiences were related to the process or the outcome. In some cases, especially for LSEs working in healthcare, participants considered their accountabilities to be process related. In these cases, interviewees referred to guidelines and procedures, as Interviewee 27 stated:

I am accountable for the health of every patient, and that every treatment is prepared correctly.

I love to do my job. I love to assemble the product. I love the result. My accountability lies in producing a proper product.

In many companies there is someone who works faster but with a worse quality. And he needs not four but only three hours for an object to clean. The supervisors look at it and tell me to reduce cleaning time, but they don’t ask at what quality the other person did the work.

Salience

Interviewees reported that they feel more accountable towards outcomes that they personally perceive as important or significant. Interestingly, all participants described outcomes only as salient or significant when they were related to accountabilities in their private life or in relation to patients, customers and products. Participants did not bring up the impact of their actions in direct connection to their accountabilities to the team or other organisational stakeholders. As such, participants reported high accountability salience in their private life context or in relation to accountabilities to customers and patients (work-related).

Some interviewees discussed the importance of doing their work to the highest possible standard, as the outcome would be attributable to them personally. These outcomes were not only perceived to be evaluated by supervisors, but also observed by customers and patients. And thus, providing excellent customer and patient care was an important aspect of their daily work. Interviewees also reflected on the importance of the outcome of their work, with Interviewee 32 describing how she feels accountable to design and produce a perfect product stating:

My accountability lies in a proper product. It must not have any flaws because it is expensive and has to be reproduced if something is deficient. Sometimes if there are complaints I am scared if it was me who made a mistake. That is why the product has to be flawless.

I must be very careful where I go because I am accountable for what I bring to these patients.

I think this job is very important, and I feel happy in this job. I feel that I can help people and patients. The doctor is not able to do something without me, because I have to prepare everything.

However, accountability salience was not only discussed in reference to the work-related environment including patients and customers. Participants highlighted that they felt accountable, knowing that their pursuit has a purpose that not only benefits individuals but also often referred to the positive consequences for society within the host country. In this context, participants also highlighted how these accountabilities towards patients, customers and society gave them meaning in their often-undervalued work. Interviewee 4 stated that:

I feel happy when I come and do my duties with my patients, and they are happy and satisfied. These are the positive moments in my life that show me what I am doing has a purpose.

When I come home I have almost no time, I am a single parent. I have to buy things, cook, have to get other things done. I can’t just do housework. My day is short, and I am tired when I come home from work. (Interviewee 19)

Intensity

The act of trying to balance accountabilities from different stakeholders between private and work-life was a constant theme in the interviews among all occupations. The variety of sources inside (e.g. supervisors, patients and regulations) and outside (e.g. family and society) the work context, the increased focus on the outcomes of their work and the high degree of accountability salience such as the impact of work on customers, patients and families, results in high levels of accountability intensity. In the realm of the work-environment, accountability intensity can affect the outcome as stated by Interviewee 33:

We had to do extra cleaning of the door handles and handrails during the pandemic. We said to our supervisor that we can do it, but it is an extra task that we can’t do in the same amount of time. Unfortunately, we did not get more time, so we decided not to clean handles and handrails.

Prioritising is very difficult, but I must balance everything. Of course, my children are my priority, but I have to do my job as well. You can’t raise children without having a job.

I always have my children in my mind […] Working is fine, and I am physically here but there are always my children in my mind.

I was working during the times of the pandemic […] my daughter was at the after-school-care centre, but they didn’t do the homework. When I came home, we sat on the computer, and we had to do the entire homework until late at night. Some things had to be sent to the teacher for grading. That was very difficult. But I had to do everything to support my daughter.

Sometimes it is not easy to bring private and work-related things into alignment. My mother and sister have to register to be entitled for governmental benefits. They have been at the social welfare office and the labour office. I have to join them for appointments to translate and I have to take a day off from work. This is also stressful. (Interviewee 27)

Discussion and conclusion

The present paper evaluates how individuals of low socioeconomic status, often employed under precarious circumstances, experience, manage and prioritise accountabilities. Drawing on a study of LSEs in Germany we show that the experience of accountability is not restricted to the work context, but that LSEs consider accountabilities in their private lives as most important. Previous accountability literature has focused mainly on individuals of higher socioeconomic status, with frameworks focusing almost entirely on accountabilities in relation to work (Frink & Klimoski, Citation1998; Hall et al., Citation2017; Han & Perry, Citation2020b). Our study illustrates that LSEs do not perceive these work-related accountabilities as crucial for their decisions and behaviour at work. Although Han and Perry (Citation2020a) argue that the five dimensions attributability, observability, evaluability, answerability and consequentiality provide theoretical explanations for employees’ accountability in organisations, the often challenging employment and life circumstances of LSEs, facing precarious employment conditions, stigmatisation in their host country society and isolation from their social home country networks (Abbas et al., 2021) and families (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022; Holtbrügge, Citation2021) add an additional layer of accountability factors that influence the perception and prioritisation of accountabilities.

These factors result in a strong intersection of private and work life that was largely ignored in previous accountability studies (Hall et al., Citation2017). This is particularly interesting as research on work-family conflict has shown a significant detrimental impact on various individual and organisational outcomes (French et al., Citation2018; Kelly et al., Citation2014; Michel et al., Citation2011), which might be further intensified by experiencing multiple accountabilities. The prior focus on local white-collar workers, which are less prone to undesirable working conditions and work-family conflict issues than low-status workers (Fedi et al., Citation2016) might have led to an insufficient consideration of personal life sources of accountabilities. Despite their dependency on the job, LSEs do not perceive the employing organisation itself as an important actor in their web of accountabilities (Frink & Klimoski, Citation1998). They perceive accountabilities directly from factors within the workplace (e.g. HR departments and line managers); however, only in the context of accountabilities towards their families or to outcomes that they consider as significant (towards others and their values and beliefs). This further links to high accountability salience (Hall et al., Citation2007). When LSEs believe that their decisions and actions have significance for their patients, customers, the product itself and, most importantly, their families, they feel more accountable. Therefore, they might interpret their accountabilities towards sources at work as a means to fulfil their accountabilities towards their families and oneself. Interestingly, our findings suggest that LSEs make use of these accountabilities towards their families to attribute meaning to their work. This indicates that there might be a potential impact of accountabilities on how individuals find meaning in their work that has not been considered in previous research and warrants further investigation.

Most interviewees are dependent on their income to remain in the host-country (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2021) and support their families (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022). Therefore, and due to the nature of the occupations they hold (Sharon et al., Citation2022), our sample of LSEs perceive most accountabilities as being outcome focused. In contrast to previous work (Frink et al., Citation2008; Hall et al., Citation2007), these are mostly evaluated positively as the positive outcome supports the accountability towards their family and for some also their personal values and beliefs. Participants highlighted that if they do their work well, they will likely be able to keep their job and do not expect rewards (e.g. promotions). In the context of providing good customer and patient service, they also describe their high degree of accountability towards the process as well (Hall et al., Citation2007). Several LSEs talked about their personal values and beliefs and how these result in feeling accountable for doing an excellent job without considering the additional pressure this might put on themselves. These internal accountabilities on top of the already existing web of accountabilities leaves little opportunity for LSEs to consider their own mental health and well-being (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022). At the same time this might be considered as leverage by organisations, providing them with the ability to exploit LSEs who are dependent on the job and focus on accountabilities towards the family. In contrast to white-collar workers (Hall et al., Citation2006; Lanivich et al., Citation2010), LSEs may experience even higher levels of accountability intensity due to the intersection of private and work-related accountabilities than employees of higher socioeconomic status. These are often competing and require prioritisation. Because family-related accountabilities are considered as most salient by LSEs, these are prioritised, which again can result in tensions and increased levels of distress.

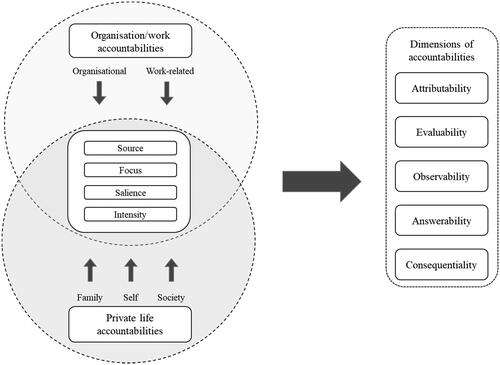

Drawing on the four features of the accountability environment (Hall et al., Citation2007), our exploratory study shows that while this framework is useful to capture features of the accountability environment of high-status workers, it is only partly applicable when exploring and understanding individuals at the bottom of the pyramid. When attempting to apply this framework to LSEs and other individuals working in low-status occupations, it needs to include the wider context of private lives to account for issues concerning social status (Haist & Novotný, Citation2023; Sunguh et al., Citation2019), work-family balance (Haak-Saheem et al., Citation2022; Shaffer et al., Citation2001) and sources of support (Haist & Kurth, Citation2022). Therefore, and to make existing accountability frameworks more applicable, we propose a revised theoretical framework as shown in .

The proposed accountability framework adds the contextual and private life accountabilities as an additional overarching dimension that affects the experience and perception of accountabilities. The framework highlights the impact of these contextual private life factors (family, self and society) on the features of the accountability environment (Hall et al., Citation2007) and eventually on the dimensions of accountability (Han & Perry, Citation2020b). This framework can help to evaluate felt accountabilities of the workforce to identify accountabilities from outside the organisational context and their potential interference with organisational and work-related accountabilities.

Theoretical contributions

The findings of this study contribute to current debates in the accountability and global mobility literature in three ways. First, by focusing on the historically disadvantaged and under-researched group of LSEs and analysing how they perceive, manage and balance accountabilities, this study illustrates how voicing their experiences can help highlight the shortcomings of current theory and empirical research. The findings raise the question of whether our understanding and operationalisation of accountability as it is currently used in the organisational literature can be applied without modification or adjustment to LSEs. Our findings suggest that the experience and perception of accountabilities for expatriates in low-status occupations may be different from those reported in previous research that mostly focussed on individuals of higher socioeconomic status. Understanding the perceptions of accountabilities of LSEs is important when considering the complex webs of accountabilities and exploring the factors underlying the decision making in their prioritisation of accountabilities. If individuals do not perceive formal accountability systems as important, these policies fail to guide and encourage accountable behaviours at work. Therefore, frameworks of accountabilities need to encompass all sources of accountabilities that might or might not affect individuals’ behaviours.

Second, the present study advances the field by illustrating that due to the narrow focus on individuals of higher socioeconomic status existing accountability frameworks do not sufficiently cover accountabilities that are not directly rooted in work. The study provides evidence that accountabilities can also stem from sources outside of the organisation. These private life sources of accountability can not only potentially interfere with accountabilities in the context of the organisation, but it might also be that employees prioritise these private life sources of accountability over those from work. Thus, current theory omits an important part of accountability that hinders a more holistic understanding of the concepts and its implications for accountability policies and procedures implemented by HR. As such, the present study highlights the need to review and extend the current framework by Hall et al. (Citation2007) and assumptions on the sources of accountability by extending its focus beyond the workplace. The findings demonstrate that accountability sources are not only work-related factors or individuals but can stem from the family, society and personal values and beliefs. This paper highlights that these can be more important for guiding individual behaviour than formal and informal sources of accountability in the workplace. While our study focuses on LSEs, the consideration of accountabilities outside the workplace might be relevant for all types of workers.

Third, this study contributes to the literature by further developing the framework of the features of accountability environment by Hall et al. (Citation2007). The revised framework () accounts for the importance of an individual’s private life and self-accountabilities, and thus adding other sources of accountabilities that have been largely neglected in previous research. This addition is important when the framework is used to evaluate the impact of formal and informal accountabilities on the entire workforce as private life accountabilities might interfere with those from work. They might not only affect the perception of accountability salience and focus but might also lead to higher levels of accountability intensity and thus, potentially increasing levels of distress. Additionally, the revised framework integrates the dimensions of accountability outlined by Han and Perry (Citation2020a) to illustrate that the evaluation of these is also contingent on the different sources of accountability inside and outside of the organisation.

Practical implications

The findings of this study provide novel and important insights for organisations and HR. In light of increased demand for workers to ensure sufficient and appropriate staffing in the low-wage sector (Molitor et al., Citation2018), organisations need to consider practices that enable LSEs to balance accountabilities between the workplace and their private lives. It might be beneficial for organisations to focus on the whole person approach that recognises that employees not only lead lives within the organisation, but that they whole lives with existing accountabilities outside of the workplace (Morrison, Citation2022). By considering these private life accountabilities and providing adequate personal and professional support might benefit LSEs and organisations alike. A lack of accountability to the employing organisation can be a concern for HR, as accountability is crucial to avoid undesirable and encouraging desirable workplace behaviours. Moreover, the lack of accountability to the organisation, line managers and coworkers might be detrimental to the employment relationship. HR could provide policies and procedures that ensure long-term relationships with LSEs by providing job security through offering permanent employment as opposed to the current extensive use of temporary employment and avoiding work intensification, which creates distress over and beyond accountability intensity. Moreover, HR can offer social resources such as organisational and social support (e.g. employing corporate social workers) that increase individual well-being of their low-status workforce. Additional benefit policies for LSEs such as training and development courses in language, culture, tax and finances would be valuable educational resources not only for employees but could also be made available to family members through online accessibility. These measures would help LSEs integrate into the organisation and the wider society. HR should review their accountability procedures and policies considering the role of private life and self-accountabilities of their workforce and reflecting on the importance of holding managers accountable to enable HR policies to their low-status workforce (Hewett et al., Citation2023). Focusing on HR practices that enable LSEs to balance work and private life accountabilities by using flexible work schedules or where applicable, grants and care services for family members, can help LSEs to reduce distress and potentially enable organisations to increase LSE retention, commitment and satisfaction.

Limitations and future research

The present study benefits from a rich interview-based dataset of a difficult-to-reach population, presenting evidence for the limited applicability of previous frameworks. This paper highlights the importance of accountabilities from individuals’ private lives providing a revised framework of accountability. However, the findings of this study need to be interpreted in the light of its limitations that should be addressed in future research. As with any in-depth qualitative research, the interpretation of our results is restricted to a sample that is confined to individuals in a unique position within the German labour market. Future research might attempt to extend our study. This can be done by drawing on local low-status workers who are not internationally mobile and often employed in more favourable conditions than their expatriate colleagues or extending the research to validate the findings in different contexts, cultures and countries. Comparative studies could be used to explore how the socioeconomic context and different resources outside of the organisation might impact the perceptions of accountabilities of white-collar workers and employees in lower status occupations. Future research would also benefit from examining whether LSEs prioritize non-work accountabilities more than other workers. It might also be interesting for future research to explore the interconnection between felt accountabilities and the experience of work family conflict as well as the role of family for other types of workers. There is a possibility that some findings might be driven by the organisational or national culture. Future research should therefore explore how organisational and national culture might affect the perceptions of accountabilities (Gelfand et al., Citation2004). Although we took great care to reach a diverse sample, the use of snowball sampling applied in this research might lead to an exclusion of diversity and extreme cases of deprived and neglected employees might not have been covered. Some participants had to withdraw from the study due to pressure from their employers. Thus, future research might target extreme cases by theoretical sampling to help further develop our understanding of the perception and lived experiences of extreme cases of marginalised workers. Lastly, due to the disclosure of the objectives of the research prior to the interviews, there is a potential of a priming effect of participants responses, which should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. These studies could implement a participatory (potentially action-based) research approach to facilitate access in collaboration with NGOs and unions. Future researchers might develop hypotheses based on our proposed framework of accountability and test these propositions using quantitative methods in a generalisable sample of LSEs or other groups of marginalised workers.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Angela Hall and the editorial team for careful and supportive editorial guidance and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and feedback. We would also like to thank Daniela Gavris for her active support and Emma Parry for her professional feedback and guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not made publicly available due to privacy restrictions (e.g. containing information that could compromise the privacy of participants).

References

- Abbas, A., Sunguh, K. K., Arrona-Palacios, A., & Hosseini, S. (2021). Can we have trust in host government? Self-esteem, work attitudes and prejudice of low-status expatriates living in China. Economics & Sociology, 14(3), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2021/14-3/1

- Abdelhady, D., & Al Ariss, A. (2023). How capital shapes refugees’ access to the labour market: The case of Syrians in Sweden. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(16), 3144–3168. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2110845

- Aleksovska, M., Schillemans, T., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2019). Lessons from five decades of experimental and behavioral research on accountability: A systematic literature review. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 2(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.22.66

- Alvesson, M., & Deetz, S. (2000). Doing critical management research. Sage.

- Andresen, M., Bergdolt, F., Margenfeld, J., & Dickmann, M. (2014). Addressing international mobility confusion – developing definitions and differentiations for self-initiated and assigned expatriates as well as migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(16), 2295–2318. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.877058

- Appelbaum, E., & Schmitt, J. (2009). Low-wage work in high-income countries: Labor-market institutions and business strategy in the US and Europe. Human Relations, 62(12), 1907–1934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349200

- Archibald, M., Ambagtsheer, R., Casey, M., & Lawless, M. (2019). Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691987459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919874596

- Cascio, W. F. (2012). Methodological issues in international HR management research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(12), 2532–2545. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561242

- Charmaz, K. (2008). Views from the margins: Voices, silences, and suffering. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 5(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880701863518

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage.

- Cullinane, S., Bosak, J., Flood, P., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job design under lean manufacturing and the quality of working life: A job demands and resources perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(21), 2996–3015. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.948899

- Davis, W. D., Mero, N., & Goodman, J. M. (2007). The interactive effects of goal orientation and accountability on task performance. Human Performance, 20(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959280709336926

- Doherty, N., Dickmann, M., & Mills, T. (2011). Exploring the motives of company-backed and self-initiated expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(3), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.543637

- Enzle, M., & Anderson, S. (1993). Surveillant intentions and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.257

- Fedi, A., Pucci, L., Tartaglia, S., & Rollero, C. (2016). Correlates of work-alienation and positive job attitudes in high- and low-status workers. Career Development International, 21(7), 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-03-2016-0027/FULL/PDF

- Ferris, G., Mitchell, T., Canavan, P., Frink, D., & Hopper, H. (1995). Accountability in human resource systems. In G. Ferris, S. Rosen, & D. Barnum (Eds.), Handbook of Human Resource Management (pp. 175–196). Blackwell Publishers.

- French, K. A., Dumani, S., Allen, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and social support. Psychological Bulletin, 144(3), 284–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/BUL0000120

- Frink, D., Hall, A., Perryman, A., Ranft, A., Hochwarter, W., Ferris, G., & Todd Royle, M. (2008). Meso-level theory of accountability in organizations. In J. J. Martocchio (Ed.), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management (Vol. 27, pp. 177–245). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(08)27005-2

- Frink, D., & Klimoski, R. (1998). Toward a theory of accountability in organizations and human resource management. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 16, pp. 1–51). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

- Frink, D. D., & Klimoski, R. J. (2004). Advancing accountability theory and practice: Introduction to the human resource management review special edition. Human Resource Management Review, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.02.001

- Gelfand, M. J., Lim, B. C., & Raver, J. L. (2004). Culture and accountability in organizations: Variations in forms of social control across cultures. Human Resource Management Review, 14(1), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.02.007

- Grabka, M., & Schröder, C. (2019). Der Niedriglohnsektor in Deutschland ist größer als bislang angenommen. [The low-wage sector in Germany is larger than previously assumed]. DIW Wochenbericht, 86(14), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.18723/DIW_WB:2019-14-3

- Haak-Saheem, W., & Brewster, C. (2017). Hidden’ expatriates: International mobility in the United Arab Emirates as a challenge to current understanding of expatriation. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(3), 423–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12147

- Haak-Saheem, W., Brewster, C., & Lauring, J. (2019). Low-status expatriates. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 7(4), 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-12-2019-074

- Haak-Saheem, W., Liang, X., Holland, P., & Brewster, C. (2022). A family-oriented view on well-being amongst low-status expatriates in an international workplace. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 44(5), 1064–1076. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2021-0256

- Haak-Saheem, W., Woodrow, C., & Brewster, C. (2021). Low-status expatriates in the United Arab Emirates: A psychological contract perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(6), 1157–1181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1983632

- Haist, J., & Kurth, P. (2022). How do low-status expatriates deal with crises? Stress, external support and personal coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 10(2), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-03-2021-0039

- Haist, J., & Novotný, L. (2023). Moving across Borders: The work life experiences of Czech cross-border workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(1), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCMS.13362

- Hall, A., Bowen, M., Ferris, G., Royle, M., & Fitzgibbons, D. (2007). The accountability lens: A new way to view management issues. Business Horizons, 50(5), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2007.04.005

- Hall, A., & Ferris, G. (2011). Accountability and extra-role behavior. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 23(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-010-9148-9

- Hall, A., Frink, D., & Buckley, M. (2017). An accountability account: A review and synthesis of the theoretical and empirical research on felt accountability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2052

- Hall, A., Frink, D., Ferris, G., Hochwarter, W., Kacmar, C., & Bowen, M. (2003). Accountability in human resources management. In C. A. Schriesheim & L. L. Neider (Eds.), New directions in human resource management (p. 2963). Information Age Publishing.

- Hall, A., Royle, M., Brymer, R., Perrewé, P., Ferris, G., & Hochwarter, W. (2006). Relationships between felt accountability as a stressor and strain reactions: The neutralizing role of autonomy across two studies. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.87

- Han, Y., & Perry, J. (2020a). Conceptual bases of employee accountability: A psychological approach. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 3(4), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvz030

- Han, Y., & Perry, J. (2020b). Employee accountability: Development of a multidimensional scale. International Public Management Journal, 23(2), 224–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2019.1690606

- Hewett, R., Sikora, D., Brees, J., & Moelijker, R. (2023). Answerable for what? The role of accountability focus in line manager HR implementation. Human Resource Management, 63(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22189

- Hochwarter, W., Ferris, G., Gavin, M., Perrewé, P., Hall, A., & Frink, D. (2007). Political skill as neutralizer of felt accountability—job tension effects on job performance ratings: A longitudinal investigation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(2), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.003

- Holtbrügge, D. (2021). Expatriates at the base-of-the-pyramid. Precarious employment or fortune in a foreign land? Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research, 9(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-08-2020-0055

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- ILO. (2021). ILO global estimates on international migrant workers 2021. International Labour Organization: Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_808935.pdf (Accessed 11/02/2022).

- Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., Oakes, J. M., Fan, W., Okechukwu, C., Davis, K. D., Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., King, R. B., Hanson, G. C., Mierzwa, F., & Casper, L. M. (2014). Changing work and work-family conflict: Evidence from the work, family, and health network. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 485–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414531435/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0003122414531435-FIG6.JPEG

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Lanivich, S., Brees, J., Hochwarter, W., & Ferris, G. (2010). P-E fit as moderator of the accountability – employee reactions relationships: Convergent results across two samples. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.05.004

- Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R. (2015). Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: A review of qualitative interviews in is research. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

- McNulty, Y., & Brewster, C. (2017). Theorizing the meaning(s) of ‘expatriate’: establishing boundary conditions for business expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1), 27–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1243567

- Mero, N., Guidice, R., & Werner, S. (2014). A field study of the antecedents and performance consequences of perceived accountability. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1627–1652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312441208/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0149206312441208-FIG1.JPEG

- Meuris, J., & Leana, C. (2018). The price of financial precarity: Organizational costs of employees’ financial concerns. Organization Science, 29(3), 398–417. https://doi.org/10.1287/ORSC.2017.1187/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/ORSC.2017.1187-F02.JPEG

- Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 689–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.695

- Miles, M., Huberman, A., & Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage.

- Mitchell, T., Hopper, H., Daniels, D., George, J., Gerald, F., & Ferris, R. (1998). Power, accountability, and inappropriate actions. Applied Psychology, 47(4), 497–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999498377719

- Molitor, K., Seils, E., Eisenkopf, A., Michelsen, C., & Brozus, L. (2018). Fachkräfteeinwanderung: Nachschub für Niedriglohnsektor? [Skilled labour immigration: Replenishment for the low-wage sector?]. Wirtschaftsdienst, 98(11), 760–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10273-018-2365-9

- Morrison, M. (2022). What employers can learn from the healthcare industry: A whole-person approach to caring for employees. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2022/07/11/what-employers-can-learn-from-the-healthcare-industry-a-whole-person-approach-to-caring-for-employees/

- Özçelik, G., Haak-Saheem, W., Brewster, C., & McNulty, Y. (2019). Hidden inequalities amongst the international workforce. In S. Nachmias & V. Caven (Eds.), Inequality and organizational practice: Volume II: Employment relations (pp. 221–251). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11647-7_10

- Peltokorpi, V., & Jintae Froese, F. (2009). Organizational expatriates and self-initiated expatriates: Who adjusts better to work and life in Japan? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(5), 1096–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190902850299

- Pratt, M. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856–862. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44632557

- Pratt, M., Kaplan, S., & Whittington, R. (2019). Editorial essay: The tumult over transparency: decoupling transparency from replication in establishing trustworthy qualitative research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219887663

- Saunders, M., & Townsend, K. (2016). Reporting and justifying the number of interview participants in organization and workplace research. British Journal of Management, 27(4), 836–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12182

- Schlenker, B. R., & Weigold, M. F. (1989). Process: Constructing desired identities. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Goal concepts in personality and social psychology (1st ed., pp. 243–290). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315717517

- Schulz-Hardt, S., Rollwage, J., Wanzel, S., Frisch, J., & Häusser, J. (2021). Effects of process and outcome accountability on escalating commitment: A two-study replication. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 27(1), 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/XAP0000321

- Seidenfeld, M. (2001). The psychology of accountability and political review of agency rules. Duke Law Journal, 51(3), 1059. https://doi.org/10.2307/1373184

- Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., Gilley, K. M., & Luk, D. M. (2001). Struggling for balance amid turbulence on international assignments: Work–family conflict, support and commitment. Journal of Management, 27(1), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00088-X

- Shaffer, M. A., Kraimer, M. L., Chen, Y. P., & Bolino, M. C. (2012). Choices, challenges, and career consequences of global work experiences: A review and future agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1282–1327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312441834/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0149206312441834-FIG2.JPEG

- Sharon, I., Drach-Zahavy, A., & Srulovici, E. (2022). The effect of outcome vs. process accountability-focus on performance: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 795117. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYG.2022.795117/BIBTEX

- Siegel-Jacobs, K., & Yates, J. (1996). Effects of procedural and outcome accountability on judgment quality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0001

- Sunguh, K., Abbas, A., Olabode, A., & Xuehe, Z. (2019). Do identity and status matter? A social identity theory perspective on the adaptability of low-status expatriates. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(4), e1938. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1938

- Tetlock, P. (1985). Accountability: A social check on the fundamental attribution error. Social Psychology Quarterly, 48(3), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033683

- Tetlock, P. (1992). The impact of accountability on judgment and choice: Toward a social contingency model. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 331–376). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60287-7

- Tlaiss, H., & Al Waqfi, M. (2022). Human resource managers advancing the careers of women in Saudi Arabia: Caught between a rock and a hard place. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(9), 1812–1847. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1783342

- Walsham, G. (2006). Doing interpretive research. European Journal of Information Systems, 15(3), 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000589

- Wikhamn, W., & Hall, A. (2014). Accountability and satisfaction: Organizational support as a moderator. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(5), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2011-0022