Abstract

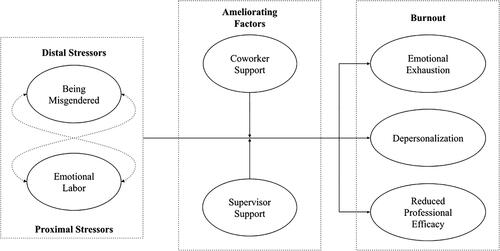

We examine nonbinary employees’ experiences with misgendering in work contexts and draw from minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003) to understand the consequences of misgendering. Our findings from 29 semi-structured interviews with nonbinary individuals revealed that although being misgendered is a common and highly stressful experience (distal stressor), the emotional labor associated with anticipating and reacting to misgendering acts as an additional and more proximal stressor. Together, these stressors jointly contribute to all three components of employee burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced professional efficacy). We also identified support from coworkers and supervisors (in preventing and addressing misgendering) as important ameliorating factors. As such, our findings provide support for the tenets of minority stress theory and extend this work by focusing specifically on nonbinary employees and on burnout, an important outcome for both employees and organizations. These findings provide a more complete understanding of the lived experiences of nonbinary employees and make unique contributions to the diversity/inclusion, gender studies, queer studies, work/life, and occupational health literatures.

Introduction

Gender is one of the most pervasive, enduring, and important social constructs that humans across the globe have ascribed to (Lorber & Farrell, Citation1991). Work, education, recreation, medical care, identity expression, and several other important social functions are bifurcated along gendered lines, some of which are extremely difficult to cross (Eagly & Wood, Citation2011). Those who do stretch or cross gendered lines often do so while maintaining the existence of these lines. For instance, many transgender individuals transgress traditional norms by altering the public expressions of their genders to be in alignment with a gender that was not assigned to them at birth in ways that still adhere to the norms associated with what is considered to be traditionally ‘for women’ and ‘for men’ (Hennekam & Ladge, Citation2022). However, some individuals eschew the notion of gender along a binary continuum altogether and are often met with severe sanctions for violating these ubiquitous norms. Many of these individuals identify as nonbinary, which is an umbrella term used to identify anyone who exists outside or beyond the gender binary and typically includes those who identify as nonbinary, gender non-conforming, agender, two-spirit, and other identities that exist outside or beyond the gender binary (Lykens et al., Citation2018; Nadal, Citation2023). These individuals commonly do not identify with society’s definitions of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine.’

Research focused on nonbinary individuals is relatively new, but burgeoning. Existing research has identified several important experiences related to being nonbinary, including prejudice and discrimination in education, healthcare, and clinical/counseling contexts (Monro, Citation2019); discrimination from coworkers and HR managers in workplace settings (Abe & Oldridge, Citation2019); differential health outcomes (Cicero et al., Citation2020); discriminatory hiring practices (Taylor & Fasoli, Citation2022); and coping and resilience factors (e.g., support from others with similar identities; Stone et al., Citation2020). The importance of this initial work notwithstanding, relatively little is known about how nonbinary employees experience work contexts, particularly with respect to how navigating a nonbinary identity at work can impact one’s work- and health-related outcomes. This is an important area of study given the prevalence of work in most adults’ lives, the functional necessity of work to maintain one’s quality of life, and the impact that workplace incivility can have on employees’ lives. Furthermore, a greater understanding of these experiences will help HR managers make more informed decisions for the benefit of both employees and the organizations in which they work.

Much of the research related to nonbinary employees reveals relatively high rates of incivility and discrimination in work contexts (Dray et al., Citation2020; Iskander, Citation2021) and there is also strong evidence demonstrating that nonbinary individuals experience negative health outcomes as a result of differential stress due to negative interpersonal interactions (Eliason et al., Citation2011). However, more clarity regarding how non-binary employees, themselves, experience and interpret workplace incivility and its link with stress-related and organizationally-relevant outcomes is needed. Such research shines light on workplace and well-being experiences among these employees and informs theoretical nuance along with practical best practices for HR managers to consider. In this study, we build on past research and leverage minority stress theory (and the more recent gender minority stress theory; Meyer, Citation2003; Testa et al., Citation2015) to make several contributions to the existing literature. First, we provide more understanding of the employee- and workplace-related implications of misgendering, a common but pernicious manifestation of incivility against nonbinary individuals that includes using pronouns or gendered language that does not align with one’s gender identity (Dolan et al., Citation2020; Nadal, Citation2023). In so doing, we provide a theory-driven examination of nonbinary employees’ experiences with misgendering in work contexts. Second, we also contribute to contemporary thought related to minority stress theory by contextualizing misgendering and its consequences within the distal/proximal stressor framework developed by Meyer (Citation2003). Importantly, we provide a novel contribution to the literature by linking minority stressors with an important employee and organizational outcome: burnout, which is a condition where a person’s engagement and enthusiasm for work slowly declines over time such that employees might feel apathetic and worn out (Edú-Valsania et al., Citation2022). As such, this study provides several contributions to the existing HRM, gender diversity, occupational health, and organizational sciences literatures. Third, we provide evidence for HR managers to be more aware of (a) nonbinary employees’ experiences, (b) how those experiences might be undermined by misgendering and burnout, and (c) how they can leverage their roles to protect nonbinary employees and reduce the incidence of burnout.

In the sections that follow, we review the current literature related to nonbinary employees’ work experiences; describe the tenets of minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003), gender minority stress theory (Testa et al., Citation2015), and burnout (Maslach et al., Citation2001; Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981); and contextualize the nonbinary experience within these frameworks. We then describe our methodology and present our findings. We conclude by discussing the theoretical and practical implications of our findings and suggest opportunities for future research.

Nonbinary employees’ workplace experiences

Although some studies focused on workplace contexts consider binary transgender and nonbinary experiences together (e.g., Fiani & Han, Citation2020; Fletcher & Marvell, Citation2023; Galupo et al., Citation2020; Huffman et al., Citation2021; Jones, Citation2020; Ullman, Citation2020), existing published research focused on nonbinary employees’ experiences highlight some of the work-related stressors that contribute to negative work and personal outcomes. For instance, Dray et al. (Citation2020) used hypothetical vignettes in which (presumably cisgender) participants provided ratings of various gender minority targets, finding that nonbinary targets who were assigned male at birth received the least positive ratings in likeability, which subsequently predicted lower perceived job performance. These differences were completely attributed to gender identity, as other characteristics of the hypothetical employee were held constant. Hennekam and Köllen (Citation2023) built on this experimental work by conducting 25 longitudinal interviews over a two year period with transgender and gender nonconforming employees, finding that their perceptions of HR managers’ reactions to and management of gender transitions reinforced gender binary norms in many ways, resulting in nonbinary individuals not feeling accepted and supported at work. Fletcher and Swierczynski (Citation2023) conducted a mixed-methods survey study of how nonbinary employees express themselves in the workplace, including suggestions for how organizations could best support nonbinary employees. One of the overarching recommendations was the importance of having coworkers as allies, stating that having coworkers has allies can decrease the amount of strain nonbinary employees experience at work (Fletcher & Swierczynski, Citation2023). Indeed, even well meaning people can perpetuate biases against nonbinary employees; Ozturk et al. (Citation2024) showed that even practitioners who specialize in diversity, equity, and inclusion could have cisgendered views that harm nonbinary employees.

In research that described the experiences of 506 transgender and nonbinary undergraduate and graduate students using quantitative and qualitative data, Goldberg, Kuvalanka, Budge, et al. (Citation2019) found that nonbinary students (75% of the sample) were more likely to experience misgendering than binary trans students and undergraduates were more likely to experience misgendering than graduate students. Further research from Goldberg, Kuvalanka, and Dickey (Citation2019) that focused on graduate students only found that most nonbinary students (70%) tailored their gender presentations to be more in line with traditional gender norms on campus to avoid mistreatment from others and that nonbinary students were more likely to be misgendered than binary trans students. Similarly, Felix et al. (Citation2023) conducted 28 semi-structured interviews with nonbinary employees and found that workplace gender identity threats (i.e., workplace cues that signal hostility to gender nonconformity) contribute to nonbinary employees altering their gender presentations at work, with resultant feelings of inauthenticity at work. These findings correspond with Hennekam and Ladge’s (Citation2022) conclusion that transgender and gender nonconforming employees may alter their gender presentations and standards for what is considered ‘acceptable’ levels of authenticity over time and in response to contextual feedback in work settings. Iskander (Citation2021) conducted six in-depth phenomenological interviews with nonbinary new teachers, who reported concern about their career prospects and that institutional gatekeepers (i.e., teacher educators) were more hostile than students or parents. Iskander (Citation2022) went on to describe the specific strategies that nonbinary teachers use to avoid hostility at work, including conducting thorough background research on potential opportunities, building supportive relationships with gatekeepers, and strategically altering their gender presentation during the hiring process. These findings corroborate those of McCarthy et al. (Citation2022), who found that nonbinary employees are likely to avoid unsafe spaces and alter their gender presentations to avoid hostility from others at work.

In short, the existing research focused on nonbinary employees highlights negative experiences in hiring contexts and with HR managers and how nonbinary employees may adjust their gender presentations in response to personal and contextual/organizational influences. We aim to contribute to this important work by centering the pervasive nature of misgendering as a particular stressor and linking misgendering with the three primary dimensions of burnout, which we turn to next.

Minority stress theory within a nonbinary population

Meyer (Citation2003) outlined how holding a sexual orientation minority identity can entail unique stressors due to prejudice, discrimination, and harassment resulting from stigmatization. These unique stressors are purported to explain differential health outcomes among sexual minority populations compared to their heterosexual counterparts. Meyer (Citation2003) described stressors as existing on a relative continuum from more distal to more proximal. Distal stressors include those completely external to the individual such as prejudice, discrimination, and incivility from others. Stressors that are more internal to the individual include concern and rumination about such negative events, self-stigmatization (internalized negative societal attitudes), and self-censoring (hiding one’s identity). With respect to nonbinary populations, research has identified discrimination and misgendering as distal stressors and internalized stigma and mental/emotional labor as proximal stressors (Matsuno et al., Citation2022; Testa et al., Citation2015). Emotional labor generally refers to the emotional work that is necessary to align one’s emotional displays with the organizational expectations for successfully fulfilling one’s job tasks (e.g., deploying a friendly and hospitable demeanor in customer service roles; Grandey, Citation2003; Grandey & Chi, Citation2016). More emotional labor is required when one’s internal and genuine emotions are misaligned with the expectations of one’s job. Emotional labor can entail managing how one expresses one’s own emotions as well as attempting to manage the emotions of others (Chawla et al., Citation2020). Thus, in the context of nonbinary employees’ experiences, emotional labor can be conceptualized as a proximal stressor to the extent that nonbinary employees must manage (a) rumination about the expectation of negativity from others, (b) suppressing negative emotions in the wake of experienced negativity, (c) and providing emotional support to others who seek to apologize for enacted negativity (Matsuno et al., Citation2022).

Meyer (Citation2003) also acknowledged the possibility of stress-ameliorating factors, namely individual-level factors such as resilience and identification with the group and group-level factors such as group solidarity and cohesiveness. Of particular importance, Meyer (Citation2003) highlighted how support from others who share a stigmatized identity can provide support for one another by creating environments that are free from stigmatization and providing interpersonal support when discrimination or harassment occurs. Indeed, Puckett et al. (Citation2015) found that sexual orientation minority participants who reported higher internalized heterosexism were less likely to participate in gay community events, which was positively related with psychological distress. In similar work, Salfas et al. (Citation2018) found that involvement with the gay community buffered the positive relationship between internalized heterosexism and negative mental health outcomes. Thus, past research supports the notion that community connectedness and support from others who share the same stigmatized identity can ameliorate the impact of stressors on health.

Minority stress theory has sometimes been applied to other marginalized groups (e.g., people of color; Lei et al., Citation2022), but most notably gender identity minorities. Indeed, Testa et al. (Citation2015) considered the unique distal and proximal stressors that transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people may experience to develop their gender minority stress theory. They also developed and validated a scale to measure the various dimensions of stressors and resilience factors for TGNC individuals. We build on this important work by focusing specifically on misgendering behaviors and on the experiences of nonbinary employees.

More recently, Matsuno et al. (Citation2022) examined nonbinary adults’ experiences within a minority stress framework. They used a deductive approach (based on the tenets of minority stress theory) to code focus groups and interview data from 29 nonbinary individuals. Their inquiry was driven by Testa and colleagues’ (2015) prior work and demonstrated support for their original conceptualization, along with new themes specific to nonbinary individuals. We expand on this important work by using an abductive approach – our inquiry began as an attempt to broadly understand the experiences of nonbinary individuals, using theory and past empirical findings to interpret these experiences, rather than beginning with theory and examining evidence in support of theory. In addition, we focus specifically on the working experiences of nonbinary employees and therefore identify work-related burnout as a stress-related outcome identified as being important among this population.

Employee burnout within a nonbinary population

Burnout has recently been described as an occupational phenomenon that occurs from enduring prolonged workplace stress that has not been successfully managed (World Health Organization, Citation2019; Maslach, Citation2003). Burnout consists of three components: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (cynicism), and reduced professional efficacy (Maslach, Citation2003, Maslach et al., Citation2001; Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). Emotional exhaustion refers to energy depletion or fatigue; depersonalization includes mental distancing, withdrawal, and/or cynicism from one’s job and/or coworkers; and reduced professional efficacy refers to feeling like one is no longer able to complete one’s job tasks effectively.

Burnout has been consistently linked with (a) organizational antecedents such as stress, poor working conditions, failed self-regulation, and emotional labor (Edú-Valsania et al., Citation2022; Bakker & de Vries, Citation2021); (b) employee consequences such as poor physical (cardiovascular issues, fatigue, diabetes, stroke) and poor mental health outcomes (anxiety, depression, illicit drug use, suicidal ideation); and (c) negative organizational consequences such as lower job satisfaction, commitment, and performance and higher turnover (Edú-Valsania et al., Citation2022; Lee & Ashforth, Citation1996). Prior research clearly indicates that stress is a precursor to burnout and that marginalized employee populations experience more stress than their majority group counterparts (Dalessandro & Lovell, Citation2023).

Velez et al. (Citation2013) reported linkages between distal and proximal stressors and general psychological distress and job satisfaction among (mostly cisgender) sexual minority employees. We extend Velez et al.s’ (2013) work by focusing on burnout among nonbinary employees. Specifically, we assert that the unique distal and proximal stressors that nonbinary employees experience at work will be linked with each of the three components of burnout. Resource-based theories maintain that burnout results from an excess of job demands (i.e., distal and proximal stressors) and a lack of organizational work resources (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017; Bakker & de Vries, Citation2021). Experiencing discrimination and engaging in emotional labor represent some influential demands that can deplete employee resources (Edú-Valsania et al., Citation2022; Rubino et al., Citation2009). Previous research has identified preventative and ameliorative strategies for managing burnout. For instance, Bakker and de Vries (Citation2021) suggest that top-down (e.g., leadership team or HR tracking employee stress levels, honing transformational leaders) and bottom-up (e.g., employee’s ability to emotionally regulate self, emotional intelligence) considerations can help prevent the incidence of and reduce the negative impact of burnout.

As such, minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003) aligns with resource-based theories (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017) to link misgendering with symptoms of burnout among nonbinary employees. Empirical evidence focused on burnout among marginalized employee groups supports this assertion. For instance, racial minority employees tend to experience higher rates of stress, emotional exhaustion, and turnover than their white counterparts (Barboza-Wilkes et al., Citation2023; Chambers-Holder, Citation2019; Shell et al., Citation2021). With respect to gender, women report more symptoms of burnout, higher levels of exhaustion and cognitive impairment, and more experiences of microaggressions compared to men (Artz et al., Citation2022; Fiorilli et al., Citation2022; Lyubarova et al., Citation2023; Norlund et al., Citation2010; Pedersen & Minnotte, Citation2017), particularly in male-dominated industries (Hall & Gettings, Citation2020). Similarly, sexual orientation and gender identity minority employees’ experiences with discrimination have been linked with burnout in work contexts (Chang et al., Citation2023; Thomas, Citation2021). Although limited research has examined burnout among TGNC populations, TGNC individuals tend to report higher rates of depression, disability, suicide attempts, and victimization compared to their cisgender counterparts (McLemore, Citation2018; Nowaskie et al., Citation2023). Lefevor et al. (Citation2019) suggested that genderqueer (people who did not identify as binary transgender or cisgender) individuals are subjected to traumatic events at an increased frequency compared to binary transgender individuals and cisgender individuals.

One stressor that is somewhat unique to nonbinary individuals is misgendering (Jacobsen et al., Citation2023; Matsuno et al., Citation2022), which includes using pronouns or gendered language that does not align with one’s gender identity (Nadal, Citation2023). Misgendering may be intentional or unintentional but it nevertheless enforces gender binary roles in a prescriptive manner (Freeman & Stewart, Citation2021; Nadal et al., Citation2016). Indeed, nonbinary individuals are more likely to be addressed using incorrect pronouns compared to their binary trans counterparts (Fogarty & Zheng, Citation2018; Goldberg, Kuvalanka, Budge, et al., Citation2019) and misgendering has been shown to be related to higher levels of dysphoria, anxiety, depression, negative affect, perceived stigmatization, psychological distress, and reduced authenticity (Galupo et al., Citation2020; Jacobsen et al., Citation2023; McLemore, Citation2015, Citation2018).

The current study: misgendering and burnout within a nonbinary population

We began our inquiry with a relatively broad goal to better understand workplace experiences among nonbinary individuals. As is common with inquiry of this type, through the process of iteratively collecting and analyzing data, we were able to refine our research focus (Charmaz, Citation2014). In particular, many participants spontaneously mentioned issues related to being misgendered and how that can contribute to burnout, which we recognized as important in our early coding. It became clear that drawing on minority stress theory as a sensitizing concept (Blumer, Citation1954; Charmaz, Citation2014) was a useful lens with which to better make sense of participants’ accounts. Participants would often implicate being misgendered as a major contributor to burnout, while also recognizing the important role that close others (coworkers, supervisors) played in their work experiences. We considered the stories that were shared with us in the context of existing theoretical orientations and empirical findings to examine the novel experiences of nonbinary employees in ways that extend current understanding of minority stress theory and burnout; and although several narratives emerged from the data, we focus our attention here on those aspects that make contributions to the existing literatures (in line with recommendations by Kreiner, Citation2016) related to nonbinary individuals’ experiences and minority stress and burnout theories.

Methods

Sample

We used a purposeful sampling strategy in which we sought to identify information-rich cases so that we could learn about the work experiences of nonbinary individuals in a theoretically deep manner (Patton, Citation2015). The final sample consisted of 29 participants. We made efforts to recruit participants with a broad range of backgrounds, so as to include participants with a diversity of ages, geographic locations within the United States, races/ethnicities, and work experiences. All participants were between 20 and 42 years old. Every participant self-identified with the term ‘nonbinary’ along with other gender identities including ‘transgender’, ‘two-spirit’, ‘genderqueer’, and ‘gender non-conforming’. The participants represented several industries, from finance to retail and food services to hospitality to healthcare (Tong et al., Citation2007). The participants also ranged in ethnicities. For full demographic details, see .

Table 1. Participant sociodemographics.

Data collection and data analysis

Participants were recruited with a mixture of strategies, including theoretical sampling, outreaching to the authors’ personal and professional networks, snowball sampling (asking interviewees to share the recruitment materials with others who would also have relevant experiences to share), and advertising on social media (Patton, Citation2015; Tong et al., Citation2007). Throughout our data collection and analysis, we sought to align with grounded theory principles (Charmaz, Citation2014; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008), which allowed for purposive sampling and inquiries that are responsive to the data being collected (see Rheinhardt et al., Citation2018). Further, we approached this work from a social constructivist perspective, drawing upon symbolic interactionism. In so doing, we were attuned to the ways in which our participants constructed social realities through interactions with others (see Charmaz, Citation2014; Mead, Citation1932).

We used semi-structured interviews (allowing for the interviewers and interviewees to further explore theoretically and practically rich ideas) in an iterative process, such that the interview protocol was modified to further explore emerging concepts and themes (Kreiner, Citation2016). In particular, the interviews initially focused on the broad work experiences of nonbinary individuals including how they navigate their gender identities at work and their interactions with coworkers and supervisors. Although not initially the focus of the interviews, participants strongly expressed how their experiences navigating their gender contributed to burnout at work. We therefore modified the protocol to also ask specifically about aspects of burnout. Interview questions are provided in the Appendix. We obtained approval from Portland State University’s IRB (protocol 184727). We conducted interviews until we deemed that we had reached saturation (Charmaz, Citation2014; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). All interviews were completed over phone or Zoom, were audio recorded with two devices, and ranged from 45 min to 2.5 h (Tong et al., Citation2007). The audio was transcribed by a research assistant with the assistance of a computerized transcription service and a member of the author team reviewed the transcriptions and reconciled any errors as needed to ensure quality and correctness. The data were uploaded and coded in Dedoose.

Our coding approach was influenced by rigorous techniques in the organizational sciences, such that we abductively considered both the emerging concepts from the data and the existing literature throughout our process (Kreiner, Citation2016). In particular, we developed thematic codes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) and drew on best practices in grounded theory (Charmaz, Citation2014). Throughout the coding process, we iteratively discussed the codes and emerging theoretical concepts while also considering how these concepts were situated within the broader literature. Codes were expanded, dropped, or subdivided to further examine broader theoretical concepts. Further, in line with Kreiner’s (Citation2016) tabula geminus approach, we identified both first-order codes (based on participant’s words) and second-order themes (abstracted theoretical themes) throughout the coding process. Specifically, theory was overtly considered alongside data from the beginning of the coding process (see Rheinhardt et al., Citation2018). In addition, we wrote theoretical memos to support our theorizing during this process (Charmaz, Citation2014). Importantly, in line with best practices for qualitative inquiry of this type, we avoid quantifying findings from our qualitative data (see Pratt, Citation2009).

Trustworthiness

We utilized Lincoln and Guba’s (Citation1985) techniques to enhance rigor and establish trustworthiness in our findings based on four main criteria: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility is a criterion with which qualitative researchers can demonstrate the ‘truth value’ of their findings by using techniques to increase the probability that their findings will be perceived as credible and demonstrating that the findings are perceived credibly by the constructors of the realities under inquiry. To enhance credibility, we practiced prolonged engagement, drawing upon our own lived experiences related to burnout and experiences and active involvement within the LGBTQIA + community. We also engaged in member-checking and iteratively questioned the data and themes we found. Transferability refers to the applicability of the findings and the extent to which findings can be applied or transferred to other contexts or subjects. Importantly, for inquiry of this type, the criterion of transferability is enhanced by providing enough contexts for potential appliers of the findings to make their own judgements about transferability. We do so through both our purposeful sampling techniques and by using thick descriptions in our findings to tell the participants’ stories, allowing us to better consider how our findings could potentially be applied beyond the studied context. Dependability refers to the extent to which the findings are stable over multiple data and vantage points, which we enhance by engaging in joint coding, co-creating the coding dictionary, and having discussions throughout the coding process. Finally, confirmability refers to the extent to which the findings are shaped by the research process and respondents. To enhance confirmability, one research team member kept an audit trail of our processes and adjustments to the analyses and methodologies; we then ensured team members were a part of debriefings through triangulation to avoid biases in the data. Further, we reflexively considered our lived experiences and positionality at every stage of the research process.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity involves ‘thinking about our experiences and questioning our ways of doing’ (Haynes, Citation2013, p. 73). All of the authors are members of the LGBTQ+/queer community. The first author is a post-baccalaureate researcher who identifies as nonbinary/transmasculine. The second author is a mid-career tenured professor who identifies as a gay cisgender man. The third author is a tenure-track (untenured) faculty member who identifies as a gay cisgender man. The fourth author is a PhD consultant who identifies as a transgender man. The fifth author is an undergraduate honors thesis student who identifies as transgender. Four of the authors are white and one is Latino. We believe that our embeddedness in the community and lived experiences give us an advantage in understanding these phenomena and connecting with our participants. Regarding our approach to this work, we also reflexively considered our motivations for engaging in the research, underlying assumptions we brought to the research, connections to the research, and followed best practices as recommended by Haynes (Citation2013). Specifically, those who conducted the interviews kept fieldnotes of their conversations with participants and their own emotional responses during the interviews. When reading through the transcripts to code the data, we noted how our interpretations of the data and personal biases could have affected the analysis process. Finally, throughout the entire process of this study, we met as a team to evaluate the participants’ answers and discussed our own interpretations.

Findings and analysis

We discuss our findings in line with the propositions in minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003), as they relate to both distal and proximal stressors. Although participants mentioned several different experiences that could be construed as stressors in passing, we focus on those most relevant to our focal inquiry related to misgendering and burnout as these emerged as being of central concern to participants. In addition, although the conceptualization of minority stress theory consists of two types of stressors (distal and proximal) and the conceptualization of burnout consists of three types of strains (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced professional efficacy), participants typically did not discuss these as separate constructs. Instead, participants often acknowledged how one or both types of stressors were related to one or more different components of burnout simultaneously. To present findings in a parsimonious fashion while also honoring the words of our participants, we retain these connections as the participants described them and highlight components of minority stress theory and burnout as appropriate throughout our presentation of the findings.

Distal and proximal stressors: misgendering, emotional labor, and burnout

Emotional exhaustion

The most robust finding that emerged in our data was how misgendering negatively impacted participants’ work lives. Several participants reported feeling generally exhausted at work (the first dimension of burnout) due to strained interactions with coworkers, supervisors, and customers that resulted from misgendering. For instance, one participant noted that ‘[being misgendered] feels like a scratch every time it happens…You’re just kind of exhausted’ (Participant 9). Another participant similarly stated, ‘it is exhausting; constantly defending your person’ (Participant 1). These sentiments highlight the chronic nature of misgendering in work contexts. In line with a core assumption of minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003), one participant described how although work can be exhausting for most people, ‘for most trans and nonbinary people, it’s especially exhausting’ (Participant 22). As in previous research (Matsuno et al., Citation2022; Testa et al., Citation2015), these quotes highlight how stigmatization resulting from norms and expectations related to a binary conceptualization of gender can contribute to unique stressors for gender minority group members.

Relatedly, the chance of being misgendered increases with the number of novel encounters employees experience. For instance, employees who work with a large number of customers in momentary interactions or employees who work in teams that experience high turnover are more likely to experience exhaustion caused by misgendering, as described by Participant 3: ‘Oh yeah, I mean my team turns over [a lot]…so I don’t bother to introduce myself to every single new batch of people that comes in because it’s exhausting…[to] correct people on pronouns.’ This quote also signals aspects of the second dimension of burnout, depersonalization, which includes negative attitudes toward coworkers, negative attributions for work-related events, and withdrawal from engaging with others at work (Maslach et al., Citation2001).

Depersonalization

One participant described how the emotionally draining nature of misgendering can itself contribute to depersonalization and withdrawal tendencies:

That’s a lot of work for you when you are possibly being misgendered by customers and…depending on…how you’re feeling, you might need to be able to take a break or step back, but that’s usually not an option…So mentally…I just felt overworked. I was like, ‘I can’t do this anymore. I’m so stressed. I never feel like I’m enough’ (Participant 24).

It’s like, usually if I’m having a [bad] day…and then someone comes in and they’re like, ‘hello, female.’ I’ll just go on autopilot…for like the rest of the week, I’ll just feel this horrible, detached feeling and emptiness. And it’s really hard…to express that to people because they’re like, ‘all [I] did was say a word’ (Participant 24).

I’m not sure if [the misgendering is] intentional or just ignorance…There’s still people who will just keep using she/her [pronouns]. There’s like one guy in another department who’s just like…I don’t know what his problem is, but he just really insists on [using] she/her [pronouns], and mostly I just try not to interact with him (Participant 10).

Another participant described how intentional misgendering contributed to detachment from their job:

My supervisor, any time we worked together, she would never get my pronouns right and she always had like another fucking basic question to ask me about my body or my sex life [and] it was just like, ugh, ‘you’re my supervisor, you should really know better.’ I usually just tried to not work when she was working (Participant 3).

Everybody that I interact[ed] with on a regular basis, [would ask]…questions and [make] comments…just everything become[s]…exhausting, [so] I’m like, ‘Okay, well I will definitely not be doing this again. Next time, like the next job, [I] will not be disclosing my identity (Participant 22).

This participant’s negative experiences with misgendering and the resultant emotional labor associated with managing others’ inquiries led this participant to conceal their identity. Importantly, the emotional labor that results from being misgendered and motivations to conceal one’s identity are both conceptualized as proximal stressors according to minority stress theory (Matsuno et al., Citation2022; Meyer, Citation2003: Testa et al., Citation2015). Thus, this quote highlights how distal stressors (e.g., being misgendered) can be intermingled with proximal stressors (e.g., emotional labor and concealment) in such a way as to jointly contribute to aspects of burnout (e.g., exhaustion and depersonalization).

In other cases, participants attributed emotional exhaustion and depersonalization to having to soothe the sensibilities of coworkers who had misgendered them. One participant explained,

My coworkers try their best to honor my pronouns. But whenever they get it wrong, there’s often a lot of profuse apologizing and I always, you know…you kind of have to be like, ‘no, don’t worry about it. It’s okay.’ And that just makes it difficult because I just wish people would [recognize that] it’s okay to make a mistake. Just don’t make me have to console you. That’s hard for me as well. Then that makes it feel like I can’t ask for my pronouns to be respected [be]cause it’s distressing to you (Participant 24).

An additional participant similarly noted, ‘y’know, [I] do my best to help educate without exhausting myself on emotional labor’ (Participant 9).

Another form of emotional labor involves suppressing emotions that are counterproductive or upsetting. For instance, one participant elucidated this concept by discussing how their role as a caregiver requires them to be strong for others, despite feeling in need of support themselves:

Taking care of somebody [for employment] is a lot of work in general and on top of that, having to take care of myself and my own mental health and also be[ing] misgendered all the time. It’s not always appealing to have to go [into work]…every week…[and] I can’t, like, have my own emotions while I’m at work, basically. So I have to put a lot of that aside a lot of the time and try to not get annoyed or feel any type of way about it. Cause I just, I’m supposed to be like a supportive, caring person (Participant 29).

Depersonalization can also include negative attitudes toward one’s job. One participant described how their experiences with being chronically misgendered elicited such negative attitudes, which also contributed to them engaging in several counterproductive work behaviors:

[Being misgendered] becomes exhausting to a point that I’m definitely not performing well at my job. I’m really doing the bare, absolute minimum to not get fired…sometimes I’m fucking things up on purpose. Like retail jobs, I’d be giving people shit for free, giving them discounts that maybe don’t even exist. I don’t fucking care. People are stealing…I’m like, ‘great. I’m not getting paid enough. I got called girly this morning, you can go ahead and steal’ (Participant 22).

Another participant described how even after advocating for coworkers to use their correct pronouns, these requests were still ignored:

It was just like, at that point I was just so tired. I didn’t want to bring up that situation. I was like, oh, this job…has an end date. So it was like, it’s whatever, I’m going to be out of this [work] atmosphere eventually (Participant 25).

It bothers me…when somebody else at the same meeting has just referred to me as [participants’ correct name] and used my correct pronouns. And then the next person will just ignore [my pronouns] completely. At that point, it feels less like an accident and more like ‘I just don’t care’ (Participant 1).

I was kind of constantly, almost begging for the respect that I felt like I deserved with my direct manager. And it definitely led to some…cynical feelings and contempt for my managerial staff there…I felt like I wasn’t getting any of the respect that I deserved…And it was very frustrating because my direct manager was an older cisgender white man, who, for some reason, uses they/them pronouns for almost everybody, including the cisgender people that we worked with and the binary trans people that we worked with, but could not use them for me (Participant 20).

Reduced professional efficacy

Further evidence of reduced professional efficacy was provided by another participant, who described ‘constantly having to…either correct my [coworkers’] pronoun usage or…come out…it’s draining, so it’s distracting and it makes it hard to focus, to collaborate’ (Participant 3). Again, misgendering is conceptualized as a stressor that drains cognitive and emotional resources, making completing job tasks more difficult as a result.

In addition to one’s core job responsibilities, many participants identified educating others and/or correcting others’ pronoun usage as an important task they felt compelled, but often unable, to perform while at work due to the stress associated with being misgendered:

I don’t want to be the one trans person that they’ve met. I don’t want to be the one nonbinary person that they feel like they can obligate to teach [them] something. I don’t want to educate everybody. That’s not my job. I’m not getting paid for that (Participant 22).

Pretty much every single shift I would have…to correct people…and it’s like, I’m already physically exhausted. So my capacity to emotionally educate people and not essentially have a meltdown when I’m also experiencing disrespect towards my gender and having to put out more energy to correct them…it just came to a breaking point where again I pretty much had a meltdown and like I could not handle being there…and it eventually led me to quit (Participant 23).

I worked at a front desk position, [where coworkers] would…misgender me, even giving directions to clients being like, ‘oh, you should go see [participant’s former name] at the front desk and X will help you.’ They would misgender me. So it’s just like, I want to be done. I was so burnt out that I was like, ‘I just want you out of here and [I want to] finish this task so I can work on the next task.’ And I don’t want to take the time and explain, ‘actually I’m not a binary woman’ (Participant 25).

Other participants described the dissonance between their experiences at work and outside of work.

It’s [misgendering] definitely taken a toll on my mental health. I noticed that when I’m not working, I feel really great about my gender…And then suddenly…I’m on the [work] schedule and I’m immediately, like, ‘I don’t want to go to work.’ I’m just not going to be able to be myself at work. I’m not gonna be able to advocate [for myself] (Participant 24).

Yeah and I think with work, that’s a thing you can’t really remove yourself from when you’re feeling upset [about being misgendered], but you’re on the clock. Like yeah, you could make it a half day [or] you could take a personal day, but that can only happen so many times. And when it happens every day, you can’t leave every day when you get upset. You just have to hide in your cubicle. Whereas, if I’m feeling, y’know, not affirmed elsewhere in society, I can just leave that space, but I can’t do that at work (Participant 9).

These quotes again highlight the importance of the emotional work that is related to being misgendered, and how this work undermines one’s desires and ability to complete one’s work and be authentic while doing so. This sentiment also highlights important consequences related to differential experiences at work and outside of work (Ragins, Citation2008).

Nevertheless, some participants felt that although they recognized the importance of correcting others when they are misgendered, they did not feel that their work environments were conducive to such behaviors:

It’s also scary because in a professional setting, you don’t want to have confrontation with the customer, with the client…[when they] are homophobic [or] don’t understand what being trans is or what the binary is. So it can be deemed unprofessional because you’re not doing your job. Instead you’re like standing up for being uncomfortable, but also that might ruffle feathers and…make the atmosphere maybe a little uncomfortable and that person might not want to return again (Participant 25).

It’s not the job itself, it’s the act of going to work and knowing I’m going to be perceived in a certain [gendered] way by whoever comes in the door; [it] kind of makes me definitely carry myself a different way and try to put my needs as a gender nonconforming person on the back burner, and like, ‘I’ve got to be a professional now.’ Like those two things kind of can’t exist at once (Participant 18).

I just didn’t really care to [work hard] because I was like, ‘why should I be giving this much effort into keeping this shit business going when they are literally only using me for labor and don’t actually care about me as a human? This place clearly doesn’t care about me, so why should I care about it?’ I have no regrets for doing a shitty job…I’m not getting paid enough to be doing all this emotional labor in addition to my actual labor. And like, this just isn’t worth it for me. Like, I’m here right now because I need money while I’m looking for other jobs. Like, this was maybe not the most professional thing to do, but again, I didn’t give a shit. I just applied to jobs while at work because I didn’t really have energy outside of work (Participant 21).

These experiences suggest that some participants interpreted being misgendered as signals that the organization does not care about them.

Taken together, our participants clearly described experiences that suggest that being misgendered at work can contribute to the three primary dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced professional efficacy. These patterns can be summarized succinctly by this participant’s experience:

At a few prior jobs, when I’ve gotten to that point of exhaustion, I’ve kind of…broken down the etiquette that’s expected between coworkers and supervisors…it leads to [me] getting fired or…leaving my last shift and never going back or leaving in the middle of a shift. Earlier on in my transition, [quitting] was really common. That was most of the way that I left jobs was that I would be misgendered aggressively on a daily basis. And God forbid, I disclosed that I don’t identify as a binary man. I just, I would just not go back. It would just get so shitty. (Participant 22)

Stress-ameliorating factors: supportive coworkers and supervisors as coping resources

Meyer’s (Citation2003) original conceptualization of minority stress theory acknowledged the possibility and importance of factors that can prevent or reduce the impact of stressors. These include both personal- (e.g., coping and resilience, the centrality of one’s minority identity) and group-level (e.g., community cohesiveness, support from other group members) coping mechanisms. Although these two sources of ameliorating factors are certainly critical (and some participants did discuss certain aspects of individual and group support that align with minority stress theory), our data revealed a third type of ameliorating factor that was not originally discussed by Meyer (Citation2003): supportive coworkers and supervisors who are not members of the same minority group. We focus on this new dimension of support to prioritize novel phenomena and to preserve space and coherence and note that these sources of support lessened the degree of risk the the stressors we identified were linked to experiences of burnout symptoms. Despite the fact that open nonbinary identities are becoming more commonplace, it is still unlikely that nonbinary employees will have several coworkers who are also nonbinary from whom to gain support. As such, coworkers and supervisors can directly alleviate some of the stress related to being misgendered by (a) using correct names and pronouns and (b) correcting others who engage in misgendering behaviors. For example, one participant described how their supervisor would provide them with support when they were experiencing burnout symptoms at work: ‘I do have one supervisor who…I’d say [is] pretty supportive in that way [and] I can take time off if I need it. And if I am burnt out, I can advocate about burnout…and things get done still’ (Participant 29).

However, most of the participants focused on how coworkers and supervisors supported them with respect to being misgendered. For instance, one participant discussed the benefits of coworkers who were open to learning about nonbinary experiences and correct gender usage in a general way: ‘Anytime I did bring stuff up to her [about misgendering], she would be incredibly receptive…and then she stepped away and actually looked it up later. So there are good experiences’ (Participant 21). Another participant experienced something similar:

the majority of the people I interact with have gotten on the bandwagon and are using the right pronouns for me and they are very respectful [and] that’s enough that I feel safe and comfortable at work and and I know that if there were ever like an instance of harassment or anything, that I would have people to go to and HR would be behind me and that kind of thing (Participant 11).

Many participants discussed the direct benefits of having coworkers and supervisors who helped manage misgendering by addressing the proximal stressors associated with the emotional labor related to correcting and educating others: ‘The [coworkers] who I talk to typically use the right pronouns or they correct themselves if they get it wrong. They correct other people as well, which is extremely dope and saves me a lot of emotional effort’ (Participant 3). Three other participants echoed this sentiment by directly acknowledging that others engaging in emotional labor on their behalf can help preserve their own levels of exhaustion:

I do definitely feel really tired. And one thing that was really helpful was I had a friend who…would always advocate for me because I am often, really like, ‘oh, I don’t know if I feel safe, like telling this person not to call me this.’ [And my friend] would always ask me, ‘next time, would you like me to say something?’ And I would always be like, ‘you know, that would be really cool.’ Like, I don’t want to put all the onus on you, but sometimes it just feels unsafe. And then next time they came in and she would say, ‘Hey, in the future, we appreciate gender neutral pronouns’ [and] she wouldn’t out me or anything. She would just say that. And it was like the best day. And I was like, man, if everyone could do this, that would be awesome (Participant 24).

There’s nothing that feels better I guess than having somebody sticking up for you and you’re not asking him to (Participant 1).

I have [coworkers] come up to me, and…they ask me, ‘oh what pronoun would you prefer to go by?’ Like, I’ve had three new coworkers ask me that question before I even had a chance to introduce myself (Participant 12).

For me it feels very affirming. If I’m having a conversation with three people and person A refers to me as she/her but then person B is like, ‘oh, you know [Participant 9] uses “they.”’ I feel like, ‘thank god I did not have to exert emotional energy to be seen right now’ (Participant 9).

My direct manager was actually really, really great about [my pronouns]. He was a little too good about it sometimes, like, correcting customers [when they misgendered me]. He was very receptive. He was really, really great [and] actually he was really sweet (Participant 21).

If people were able to go to their boss and be like this coworker, ‘this coworker fucking sucks. They’re mis-gendering me all the time.’ And their boss [to the coworker] was like, ‘Hey, don’t be a dick, correctly gender your coworker. It’s not that hard. Figure it out or you don’t have to work here.’ Like, that makes a world of difference. That could mean the difference between that [non-binary] person staying employed or being jobless because they quit (Participant 22).

My last boss, he really, really tried to understand and educate himself [on transgender/nonbinary issues] and if…someone around us would misgender me, [he’d] always correct them. And I think it’s really important to have people in the workplace that are like [that] and stand up for trans people (Participant 23).

Misgendering happens occasionally [but] not as much on my team anymore because my boss is very actively correct[ing] people (Participant 17).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated how gender nonbinary employees’ experiences with misgendering contribute to burnout in work contexts. Overall, our data suggested that misgendering was frequent and highly stressful. Specifically, and in line with minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003), misgendering (a distal stressor) interacted with emotional labor related to misgendering (a proximal stressor) to contribute jointly to the three components of burnout (Maslach et al., Citation2001). As also predicted by minority stress theory, we identified important ameliorating factors: support from coworkers and from supervisors. In sum, our findings can be summarized as follows: nonbinary employees experience stress related to being misgendered by others. Being misgendered can also elicit depleting cognitions and emotions related to fears about being misgendered, fears about having to decide to correct others, actually correcting others, fears about managing either positive or negative reactions from others, actually managing others’ reactions (including providing consolation to the transgressor), and ruminations following such interactions with others. Together, misgendering and the associated emotional labor contribute to nonbinary employees experiencing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced professional efficacy, the three dimensions of burnout. However, supportive coworkers and supervisors can help ameliorate the negative impact of misgendering. These sentiments are depicted in .

Contributions and implications

Our work makes several contributions to the existing literature. First, we contribute to the small but burgeoning literature focused explicitly on nonbinary individuals in general (Jacobsen et al., Citation2023; Matsuno et al., Citation2022; Ozturk et al., Citation2024; Testa et al., Citation2015) and on misgendering in work contexts in particular. Although some existing research focuses on best practices for HR professionals in managing gender diversity in work contexts (Hennekam & Köllen, Citation2023) and perceptions of nonbinary employees (Dray et al., Citation2020; Fletcher & Swierczynski, Citation2023), there is little research that centers the experiences of nonbinary employees themselves that does not combine nonbinary participants with binary transgender participants (c.f., Felix et al., Citation2023; Fiani & Han, Citation2020; Goldberg, Kuvalanda, Budge, et al., 2019; Goldberg, Kuvalanka, & Dickey, Citation2019; Iskander, Citation2021, Citation2022; Jones, Citation2020; McCarthy et al., Citation2022). We also examine relatively universal phenomena, as opposed to past studies that have focused on particular industries (e.g., teachers, escorts; Iskander, Citation2021, Citation2022; Jones, Citation2020). We contribute to previous work focused on misgendering (Galupo et al., Citation2020; Jacobsen et al., Citation2023) by examining misgendering specifically in workplace contexts. In so doing, we uniquely link misgendering (and the resultant emotional labor associated with misgendering) with burnout, an important employee and organizational outcome. We also examine the impact of coworker support for nonbinary employees. Our findings align with other work that demonstrates the benefits of allyship (Martinez, Hebl et al., Citation2017; Salter & Migliaccio, Citation2019; Smith & Martinez, Citation2019), but also suggest that allies for nonbinary employees may need special competencies associated with combating misgendering (Fletcher & Swierczynski, Citation2023).

Second, we contribute to minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003) and gender minority stress theory (Testa et al., Citation2015) by focusing specifically on the experiences of nonbinary individuals in work contexts. Although Matsuno et al. (Citation2022) recently contextualized misgendering in line with minority stress theory, their analysis was based on general experiences, not on workplace phenomena, necessarily. Similarly, Velez et al. (Citation2013) have considered minority stress theory in work contexts with respect to sexual orientation, but not gender identity. Thus, we contribute to this work by synthesizing these efforts and focusing on the experiences of nonbinary employees in the context of minority stress theory. Third and relatedly, our findings provide support for the basic tenets of minority stress theory. Within this framework, misgendering represents a distal stressor, emotional labor represents a more proximal stressor, and support from coworkers and supervisors represent ameliorating factors. We also extend minority stress theory by considering burnout as an important outcome for both employees and organizations.

Fourth, our findings suggest that distal stressors and proximal stressors may be inexorably linked. Indeed, Meyer’s (Citation2003) original conceptualization describes four processes of minority stress, which can be arranged from most distal to most proximal: (a) external, objective events, (b) expectations of negative events and vigilance, (c) self-stigmatization, and (d) concealment. Our findings suggest a strong interaction between misgendering (distal) and emotional labor (proximal), so much so as to affirm their interactional nature.

Our work also reveals important implications for employees, HR managers, and organizations. First, our main finding concerns the pernicious impact of misgendering and the resultant emotional labor associated with misgendering in work contexts. Participants clearly described these misgendering experiences as stressful and, at times, dehumanizing (Jacobsen et al., Citation2023). Psychological safety and the ability to be authentically oneself at work are related to more positive work attitudes and outcomes (Frazier et al., Citation2017; Martinez, Sawyer, et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, we assert that organizations that repel talented employees based on characteristics that are unrelated to job performance will be at a competitive disadvantage. Therefore, primary recommendations include organizations working to reduce the frequency of misgendering, providing resources for employees who experience misgendering, and establishing and upholding policies and practices for addressing misgendering when it occurs. For instance, all employees, but particularly those who are involved in recruiting and selecting employees, should be instructed not to make assumptions about gender identity (Taylor & Fasoli, Citation2022), which could aid in nonbinary people not being misgendered. Organizations can also encourage those who wish to to disclose pronouns so as to normalize not making assumptions about gender. Some research identified how HR managers should review organizational policies that could impact nonbinary employees, such as dress code or bathroom policies (Fletcher & Swierczynski, Citation2023). Our results suggest also developing and actively revising policies related to misgendering, including how to report misgendering safely, what consequences will be enacted to reduce further misgendering and/or remove chronically offending employees, and what resources can be provided to employees who experience misgendering. Although none of our participants mentioned receiving support from HR professionals or top organizational leadership, support at these levels would take the onus of responsibility off of nonbinary employees and allies, allowing them to focus on their primary work tasks (Hennekam & Köllen, Citation2023).

Second, our findings revealed that coworkers and supervisors can be very influential. Specifically, these allies modeled appropriate behaviors and helped establish norms by using correct pronouns and by correcting others who engaged in misgendering behaviors. As such, organizations can arrange to provide interventions to help employees develop competencies related to being allies for nonbinary employees (Fletcher & Swierczynski, Citation2023). Traditional diversity trainings, focused on implicit bias, may not be appropriate for addressing misgendering and the evidence for the effectiveness of these trainings is lackluster (Dover et al., Citation2020; Paluck, Citation2006). However, emerging research suggests that allyship-based diversity trainings may circumvent many of the issues related to diversity trainings (Martinez et al., Citation2022). In addition, coworkers and supervisors can also be provided support, given the emotional labor associated with correcting others and the negative impact of even vicarious incivility (Miner & Cortina, Citation2016; Miner-Rubino & Cortina, Citation2007). In the absence of organizational initiatives, supportive coworkers and supervisors can commit to learning how to be better allies for nonbinary employees on their own. We encourage supervisors to act as change agents in particular, given the relative formal and referent power these individuals typically possess in work contexts (see Lunenburg, Citation2012).

Third, our findings have implications for nonbinary employees themselves. The implications of burnout signal several other negative employee outcomes including lower job satisfaction, lower commitment, lower self-efficacy, higher withdrawal and turnover intentions, and more negative physical and mental health outcomes (Ahola & Hakanen, Citation2014; Alarcon, Citation2011; Shoji et al., Citation2016). Several of our participants described not wanting to correct others due to the emotional labor involved in doing so. This is similar to other recent work by Hennekam and Ladge (Citation2022), who found that transgender employees often renegotiate and adjust their gender presentations to achieve a balance between complete authenticity and ease of interactions with others (e.g., sometimes expressing themselves in ways that are ‘authentic enough’). Similarly, Felix et al. (Citation2023) recently demonstrated how nonbinary employees may restructure their identity expressions in response to hostile environments and/or negative feedback from others. As such, it may be advisable for nonbinary employees to weigh the costs and benefits of how they express themselves and correct others, especially in contexts that are not supportive of diverse gender expressions.

Limitations and future directions

We now consider the ways in which the findings and limitations of this study provide opportunities for future research. Although minority stress theory provides a good fit to the data that we collected, minority stress theory extends beyond the phenomena that emerged in our data. Specifically, minority stress theory considers self-stigmatization and concealment as additional proximal stressors. Our initial interest in the general work experiences of nonbinary employees leveraged an abductive approach and did not anticipate the importance of misgendering and burnout or the relevance of minority stress theory as an orienting framework. If we had begun more deductively, by beginning with minority stress theory as a guiding framework, our inquiry would have included the full range of stress processes and our data may provide even more support for the tenets of minority stress theory. However, we appreciate the strength of our approach, which allows phenomena that are most important to participants to emerge organically. Thus, our analysis is more reflective of our participants’ experiences and less a direct test of all the tenets of minority stress theory. However, Matsuno et al. (Citation2022) did take a deductive approach to contextualizing nonbinary adults’ experiences within the minority stress framework and found strong support for this framework in their sample, providing evidence of its appropriateness for nonbinary experiences.

Another limitation is that our data were collected cross-sectionally, as is often the case with qualitative research of this type. However, we rely on participants’ interpretations of the dynamic and interactive processes related to how misgendering, emotional labor, and burnout were related to one another. In addition, participants’ descriptions aligned with the predictions of minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003) and alternative interpretations are not intuitive (e.g., that nonbinary employees who are more burned out or engage in more emotional labor are more likely to be misgendered). Further, given the constructivist approach we took in this study, we recognize how participants’ views and meanings—along with our theoretical interpretations—are constructions of reality (Charmaz, Citation2014). Thus, our theorizing was grounded in our participants’ interpretations of their experiences, which could be further enhanced in future research by using a longitudinal approach and observing the ways in which these experiences and perspectives unfold.

Finally, all of our data were collected within a U.S. employment context. Although we assert that the experience of being misgendered may be relatively universal, there could be different interpretations about what qualifies as ‘burnout.’ Specifically, although burnout is not a diagnosable condition in the US (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022; see Nadon et al., Citation2022) and is generally conceptualized by I/O psychologists as a multidimensional construct most often measured in a working population, some countries include formal diagnoses and/or include clinical definitions of burnout (see van Dam, Citation2021). Thus, our inquiry may have been interpreted differently in different geographic locations due to alternative conceptualizations of how burnout is conceptualized along with differing medical classifications and legal and employment rights. However, we assert that our interpretation of the data is aligned with the intentions expressed by the participants.

Conclusion

Gender norms are perhaps the most ubiquitous and enduring social constructs humans have created and the importance of gender plays out in workplace contexts clearly. In our investigation of the experiences of individuals who identify outside of the strict gender binary, we found that misgendering is a common and pernicious experience that can contribute to work-related burnout. By positioning misgendering and burnout within minority stress theory, our hope is that our findings inspire future research related to how marginalized employees experience work and what resources can be leveraged to remediate the negative impact of stress. We also encourage more research related to gender diversity, particularly nonbinary employees’ experiences, as these experiences allow for a unique understanding of the pervasiveness of gendered expectations and experiences in work contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [redacted for naive review], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abe, C. J., & Oldridge, L. (2019). Non-binary gender identities in legislation, employment practices and HRM research. In S. Nachmias & V. Craven (Eds), Inequality and organizational practice. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11644-6-_5

- Ahola, K., & Hakanen, J. (2014). Burnout and health. In M. P. Leiter, A. B. Bakker, & C. Maslach (Eds.), Burnout at work: A psychological perspective (pp. 10–31). Psychology Press.

- Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). APA. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Artz, B., Kaya, I., & Kaya, O. (2022). Gender role perspectives and job burnout. Review of Economics of the Household, 20(2), 447–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09579-2

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

- Bandura, A. (1969). Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 213–262). Rand McNally & Company.

- Barboza-Wilkes, C. J., Le, T. V., & Resh, W. G. (2023). Deconstructing burnout at the intersections of race, gender, and generation in local government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 33(1), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muac018

- Blumer, H. (1954). What is wrong with social theory? American Sociological Review, 19(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2088165

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chambers-Holder, N. (2019). Minority stress, work-related stress, burnout, and mental health issues among minority millennial workers: An explorative qualitative case study [Thesis]. Northcentral University.

- Chang, T. C., A, R., Candelario, C., Berrocal, A. M., Briceño, C. A., Chen, J., Shoham-Hazon, N., Berco, E., Valle, D. S.-D., & Vanner, E. A. (2023). LGBTQ+ identity and ophthalmologist burnout. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 246, 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2022.10.002

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Chawla, N., Gabriel, A. S., Rosen, C. C., Evans, J. B., Koopman, J., Hochwarter, W. A., Palmer, J. C., & Jordan, S. L. (2020). A person-centered view of impression management, inauthenticity, and employee behavior. Personnel Psychology, 74(4), 657–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12437

- Cicero, E. C., Reisner, S. L., Merwin, E. I., Humphreys, J. C., Silva, S. G., & Garcia, J. (2020). The health status of transgender and gender nonbinary adults in the United States. PLoS One, 15(2), e0228765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228765

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.): Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Leskinen, E. A., Huerta, M., & Magley, V. J. (2013). Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1579–1605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311418835

- Dalessandro, C., & Lovell, A. (2023). Race, marginalization, and perceptions of stress among workers worldwide post-2020. Sociological Inquiry, 93(3), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12505

- Dolan, I. J., Strauss, P., Winter, S., & Lin, A. (2020). Misgendering and experiences of stigma in health care settings for transgender people. The Medical Journal of Australia, 212(4), 150–151.e1. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50497

- Dover, T. L., Kaiser, C. R., & Major, B. (2020). Mixed signals: The unintended effects of diversity initiatives. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 152–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12059

- Dray, K. K., Smith, V. R. E., Kostecki, T. P., Sabat, I. E., & Thomson, C. R. (2020). Moving beyond the gender binary: Examining workplace perceptions of nonbinary and transgender employees. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6), 1181–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12455

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2011). Social role theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, E. T. Higgins, & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 1–560). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/5017495

- Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031780

- Eliason, M. J., DeJoseph, J., Dibble, S., Deevey, S., & Chinn, P. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning nurses’ experiences in the workplace. Journal of Professional Nursing, 27(4), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.03.003

- Felix, B., Júlio, A. C., & Rigel, A. (2023). ‘Being accepted there makes me rely less on acceptance here’: Cross-context identity enactment and coping with gender identity threats at work for non-binary individuals. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(10), 1851–1882. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2254211

- Fiani, C. N., & Han, H. J. (2020). Navigating identity: Experiences of binary and non-binary transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) adults. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1426074

- Fiorilli, C., Barni, D., Russo, C., Marchetti, V., Angelini, G., & Romano, L. (2022). Students’ burnout at university: The role of gender and worker status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811341

- Fletcher, L., & Marvell, R. (2023). Transgender and non-binary inclusion at work [guidance for employers]: Guidance commissioned by the chartered institute of personnel and development (CIPD). Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/en/publications/transgender-and-non-binary-inclusion-at-work-guidance-for-employe.

- Fletcher, L., & Swierczynski, J. (2023). Non-binary gender identity expression in the workplace and the role of supportive HRM practices, co-worker allyship, and job autonomy. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2023, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2284191

- Fogarty, A. A., & Zheng, L. (2018). Gender ambifuity in the workplace: Transgender and gender-diverse discrimination. Praeger/ABC-CLIO.

- Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12183

- Freeman, L., & Stewart, H. (2021). Toward a harm-based account of microaggressions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(5), 1008–1023. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211017099

- Galupo, M. P., Pulice-Farrow, L., & Lindley, L. (2020). “Every time I get gendered male, I feel a pain in my chest”: Understanding the social context for gender dysphoria. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah00000189

- Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K. A., Budge, S. L., Benz, M. B., & Smith, J. Z. (2019). Health care experiences of transgender binary and nonbinary university students. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(1), 59–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019827568

- Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K. A., & Dickey, L (2019). Transgender graduate students’ experiences in higher education: A mixed-methods exploratory study. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000074

- Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.5465/30040678

- Grandey, A. A., & Chi, N.-W. (2016). Emotional labor predicts service performance depending on activation and inhibition regulatory fit. Journal of Management, 45(2), 673–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316672530

- Hall, E. D., & Gettings, P. E. (2020). “Who is this little girl they hired to work here?”: Women’s experiences of marginalizing communication in male-dominated workplaces. Communication Monographs, 87(4), 484–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2020.1758736

- Haynes, K. (2013). Reflexivity in qualitative research. In C. Cathy & S. Gillian (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges (pp. 72–89). Sage Publications. https://www.torrossa.com/gs/resourceProxy?an=4913040&publisher=FZ7200#page=91.

- Hennekam, S., & Köllen, T. (2023). Trapped in cisnormative and binarist gendered constraints at work? How HR managers react to and manage gender transitions over time. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–27. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2255824

- Hennekam, S., & Ladge, J. J. (2022). Free to be me? Evolving gender expression and the dynamic interplay between authenticity and the desire to be accepted at work. Academy of Management Journal, 66(5), 1529–1553. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2020.1308